Bryan Pearson's Blog, page 10

February 9, 2018

German Lessons: What Walmart Could Have Learned From Lidl, And Vice Versa

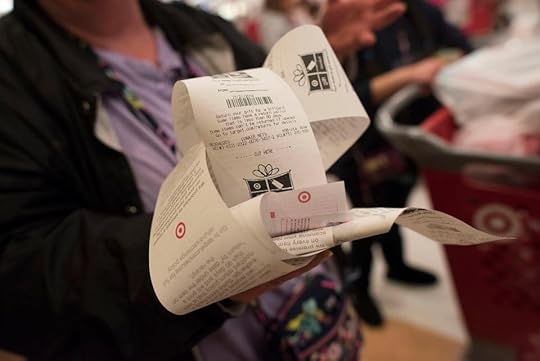

In mid-January, less than a week after Walmart abruptly closed scores of Sam’s Club stores, the CEO of low-cost grocery chain Lidl told a German magazine that his company, too, would pull back its planned store count in the United States. But he also admitted to a big mistake.

(Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

“Several things have gone wrong,” Klaus Gehrig told Manager Magazin about Lidl’s aggressive, 48-store expansion into the states, which kicked off in June 2017. He described the German retailer’s U.S. entry as a “catastrophe.” Among the miscalculations that led to weak sales, he said Lidl failed to address American shopping preferences.

Walmart, which abandoned the German market in 2006 after nine troublesome years, also would appear to benefit from a better understanding of the American consumer, based on how it handled the Sam’s Club closings.

Several news reports relayed stories of confused shoppers arriving at dark stores with locked doors, greeted by crying employees who were not alerted to the closures. If that sight wasn’t enough to turn shoppers off, there’s the issue of the prescriptions many had come to fill, not to mention the items waiting to be checked off their grocery lists.

The key difference between these two retail giants’ missteps is Walmart has 55 years of U.S. operating experience. Still, each chain could learn a few things from the other.

3 Cultural Lessons

Most intriguing about the Lidl-Walmart cutback overlap is Walmart’s struggle with similar oversights when it attempted a German expansion more than a dozen years ago. It pulled out of the nation after getting its prices, products and employee culture wrong.

Fast-forward to 2018, and Lidl’s CEO conceded his own company’s mistakes. Lidl had planned to open as many as 100 locations by this summer, but now projects just 20 in all of 2018, and they’ll reportedly be smaller formats. Like Walmart in both Germany and the U.S. with the recent Sam’s Club closures, it misjudged shoppers’ expectations of the chain.

While Lidl faces issues in retail today involving technology and data that Walmart did not years ago, the events do point out how repetitive the mistakes in the industry are. Here’s where both merchants went wrong, and where they can learn from each other.

Lesson 1: They didn’t put on shopper shoes (or schuhes).

Among Lidl’s recognized miscalculations, Gehrig said the chain failed to address American shopping preferences, such as for prepared foods. He also attributed the chain’s problems to poor locations and stores that are too big and expensive. It intends to roll back on experiments and store upgrades and limit its product range — it sells a lot of apparel and other nonfood items — to make the shopping trip simpler.

Walmart, in Germany, implemented a high-service/low-price business model in a market that did not appreciate the combination. Employees enthusiastically greeted shoppers at the door and offered help every 10 feet, which the unaccustomed Germans found annoying. Further, language barriers cost it key business connections. Years later, here in the U.S., communications continue to be an issue, as Walmart appears to have closed the Sam’s Club stores without alerting them first, thereby not recognizing their needs.

Lesson 2: They should have made shoppers their lead motivation.

One possible reason for Lidl’s slip-up in the U.S. is it might have focused too much on what its top rival, Aldi, was up to instead of what its new shoppers expected. It ventured into the opposite direction of low-fringe Aldi, with large, higher-end stores that many U.S. shoppers found too complex for quick trips. Lidl also might not have paid close enough attention to what its future U.S. competitors were up to — many were lowering prices ahead of its entry.

Walmart similarly might have been concentrating too singularly on the wrong motivation when choosing to shutter 63 Sam’s Club locations, affecting 9,400 workers. Rather than considering the longer-term effects, the immediate closings would have on its customers — all of whom paid for Sam’s Club memberships (they will be refunded) — it appeared to have been concentrating on the bottom line. That it announced employee pay raises, to $11 an hour, earlier on the same day made it appear Walmart was trying to mask an unpopular act with a popular one.

Lesson 3: Employee matters matter.

Lidl appears to understand what U.S. workers value, at least in terms of compensation. Store associates here earn a minimum of $12 an hour. Benefits, as detailed on its website, include medical, dental and vision insurance, a 401(k), life and disability insurance, an employee assistance program and time off for volunteering. However, the chain did replace its German head of U.S. operations in September after just three months, hinting at a “paramilitary” style of management that “wants to force success,” as described in Supermarket News. This could turn off potential talent.

While Walmart’s U.S. pay raises were applauded, they are now tethered to the bad mojo of the abrupt Sam’s Club closings. Walmart would have benefited from an advance warning, as Lidl provided with its reduced expansion plans. As for its employment experience in Germany, Walmart struggled to develop a good relationship with labor unions. For example, the retailer’s ethics code prohibited inter-office romances and encouraged workers to report inappropriate behavior, which concerned the union. Further, it operated the division from its headquarters in the United Kingdom, where English was the official corporate language. This resulted in communication breakdowns among German managers who did not speak English. Many left.

What both chains have in their favor is the experience and size to weather small missteps, but neither should take these benefits for granted. With an increasing number of shoppers buying their groceries online and more nonsupermarkets entering the food category, the line that divides success from failure is becoming thinner than any cultural border.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

January 25, 2018

6 Reasons An Amazon-Target Merger Could Be Bad For Shoppers

Photographer: Mark Kauzlarich/Bloomberg

Retail analysts may think it’s Prime time for a takeover, but are Target shoppers prepared for the changes Amazon would impose on their beloved Tar-zhay?

A potential name change alone (Ama-zhay?) is just the beginning of how an Amazon acquisition could change what millions of shoppers expect in their ritual Target shopping experiences. Could the combined company maintain the Tar-Zhay pizzazz?

Loyal Target shoppers need not worry, for now. A recent headline-grabbing report predicting Amazon would take over Target has been dismissed by many. Still, it has forced us to wonder: What would a combined Amazon-Target brand look like?

For shoppers, it may not result in a better experience, particularly in store. Here are six questions shoppers should ask.

1. Could prices change?

Very likely, and not always for the better. Price comparisons of select Target products against those at Amazon-owned Whole Foods Market show Target charges less in certain categories. When it comes to Target’s fashion, beauty and housewares, many of which involve private labels, it’s just not clear how Amazon would handle price until it had a chance to examine vendor and manufacturing contracts and cost structures. If the cost of carrying these items eats more into the margin than Amazon is willing to withstand, it could raise prices, reduce promotions or simply limit terms of distribution. The future of Target’s free Cartwheel app, which offers discounts in the aisle, would also likely come into play.

2. What would happen to Target’s brand selection, including private label?

Both Target and Amazon are building their private-label portfolios, and some of the brands would likely not survive a merger. Target plans to launch 12 brands over the next year or so. Amazon owns more than 30 private labels, including all of Whole Foods’ 365 Everyday Value line. If any Target brand fails to meet Amazon’s standards for performance, even if it appeals to a loyal niche market, it could be shelved. This extends beyond private labels. Whole Foods is asking suppliers, including local small-business owners, to work with its own retail strategy firm (and help pay for it) to save costs and centralize operations as Amazon strives to reduce prices. As a result, some smaller suppliers said they’ve seen their shelf space shrink in favor of national brands.

3. I get my prescription filled at CVS/Target. Would that be affected?

CVS Health Inc., which operates pharmacies in roughly 1,600 Target stores, may not prescribe to an Amazon partnership. Amazon has been looking into the pharmacy business for some time and has received approvals for wholesale pharmacy licenses in at least 12 states as of October. Some believe these efforts pressured CVS to acquire Aetna Insurance — to stave off Amazon’s entry into pharmaceuticals, according to The Wall Street Journal. With so much on the line, financially and operationally, CVS could balk at selling through Amazon, or regulators may not allow it in states where Amazon does not have a license.

4. If Amazon owns Whole Foods, would it want to sell food at Target?

Target has been struggling to strengthen its grocery legs for a couple of years (it recently agreed to purchase grocery-delivery startup Shipt Inc.). Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods raises the bar, making Target grocery vulnerable. If Amazon were to acquire Target, it might choose to dismantle its grocery strategy altogether in favor of focusing on Whole Foods. In doing so, it would eliminate an important source of convenience for shoppers, even those who piggyback limited grocery purchases on their trips for apparel and household goods. That being said, there could be a chance Amazon would add Whole Foods products to Target stores (perhaps even under special Whole Foods signage), but that could result in lost Whole Foods sales or cannibalism. And it could eliminate some of the brands and/or products some shoppers favor.

5. How important would I be to Amazon as a Target shopper?

When fewer entities own more of the brands we interact with on a regular basis, it means more homogeneity. There could appear to be a greater number of choices in both what to buy and how to buy it, but the control of those choices rests with fewer companies. This means an individual shopper’s voice may count for less because there are more shoppers influencing a single corporation’s decisions. The shoppers with the most sway may prefer different channels, spend more money per trip or simply wear larger sizes. In short, they could be vastly different from the minority.

6. Would any Target stores close?

Amazon has eschewed a massive brick-and-mortar retail presence for a reason — to avoid bankrolling expensive stores. Investors like this about Amazon. If it were to acquire the roughly 1,800 Target stores, not to mention its 320,000 workers, Amazon’s model would shift to a more cost-intensive traditional retailer. And that would affect the stock price. Even if it didn’t, an Amazon-Target combo would likely undergo government regulatory scrutiny due to concerns regarding market dominance.

Lastly, what of the Target élan? Target shoppers are loyal because they have grown close to its brands, store layouts, vibe and in-store experience. Why invest substantially in so many locations when many of the brands and products Target sells are already available on Amazon via a completely different experience? You could almost hear Target shoppers shouting, “Tou-zhay!”

If customer satisfaction and new revenue streams are its goals, Amazon might be better off targeting a bank.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

January 22, 2018

Retailers Want Your Business: 5 Great Opportunities For Shoppers In 2018

The shopper came to the store to pick up an awaiting jacket. She left having been offered free tailoring and a glass of wine, with a sense of being swept off her feet — all within steps of the shop door.

Pixabay

This will be the retail experience of 2018. Pressured by data-enhanced online competition, nimble startups and super-powered shoppers, retailers are testing their creative abilities to recapture the shopper’s imagination. And this will manifest in many great opportunities for shoppers in the coming months.

In short, it will be a buyer’s market for shoppers. As many as 12,000 stores are predicted to shutter in 2018, according to estimates by commercial real estate firm Cushman & Wakefield. That follows roughly 9,000 store closings in 2017, when more than 50 retail chains filed for bankruptcy protection, reports Business Insider.

Retailers are responding by inventing new ways to romance shoppers, and that means identifying what they want most. All of which leads to big opportunities for consumers. Here are five that shoppers can expect in 2018.

1: More free services. Free samples are rarely rejected, but now they are sooo 2015. Today’s shopper can expect free cosmetic treatments, in-home tech consultations and classes. And they can even anticipate these perks without buying something. The Apple Town Square store in Las Vegas (and other locations) offers free classes in music, photography and technology basics (all using Apple devices). Sephora offers free mini makeovers; Best Buy sends in-home advisors to help customers with smart homes, appliances and more; and Walmart plans to expand free curbside pickup to 1,000 locations in 2018, for a total of 2,100 stores.

2: More relevant offers and suggestions. Retail’s broad adoption of artificial intelligence and machine learning is enabling brands to access massive amounts of data to more accurately assess shopper preferences and make on-the-money suggestions. For shoppers, this means successful (and shorter) shopping trips. Alibaba uses deep learning to enable what it calls FashionAI: In-store interactive screens that make clothing and accessory suggestions to shoppers based on what they are trying on. Shoppers can then make their choices on screen. The screen does not use a camera; it reads information on product tags and relies on a memory of millions of clothing items, by store.

3: More for less (time). Forget bitcoin; retailers realize that time is among the most valuable of currencies shoppers trade in today. Freestanding kiosks that offer endless aisles of products, new store layouts to accommodate quick trips, and grab-and-go meals at the door will be commonplace as retailers retrofit their formats. Target’s next-generation store in Richmond, Texas, includes two entrances, one expressly for online pickups or grab-and-go food items. In Spain, the fast-fashion chain Zara is following Walmart’s lead and testing self-service kiosks where shoppers can retrieve orders they placed online.

4: More bargaining. Many shoppers expect to dicker over the price of a mattress or car, but they can apply those same skills, with success, at specialty and department stores. Many electronics chains, for example, are willing to haggle on price, according to Consumer Reports. Beyond the price tag, shoppers of Jet.com can get lower prices on items if they order more than one of each. Or shoppers can squeeze out as much product as they can for one price. MoviePass and Smashburger are among brands offering unlimited or nearly unlimited products and services for a flat fee. In many cases the shopper only needs to use the pass a few times a week to break ahead.

5: Less aggravation. Retailers are acknowledging shopper pain points for what they are: Barriers to purchase, not necessary evils. Casper Mattress answers the generations-long plea to just get the mattress into the bedroom without a rope, car roof and sore back. Returns are another major area where shoppers can expect relief. With Walmart’s return app, Mobile Express Returns, shoppers simply enter the merchandise info and then make a brisk return through a dedicated express lane. For those unhappy with online purchases, the retail service Happy Returns operates a network of return bars that accept items purchased from a variety of participating brands. The service, in nearly 15 metro areas, is free and does not require receipts.

Retailers may have lots of price power, brand contracts and shopper data, but they recognized a long time ago the shopper has control, and is gaining more. Technology liberates shoppers to purchase their shoes, meals and makeup based on what is at their fingertips at the precise moment they need these things, so why settle for less? Retailers know the only way to stand out is to be amazing.

Happy 2018. Prepare to be amazed.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

January 16, 2018

Is It Time To Hit The Restart Button On Omnichannel? Take Our Quiz

Pop quiz: If 74% of shoppers prefer to receive promotions by direct mail, but 69% prefer email and 62% want offers via a website, then is the future of omnichannel a gold mine or a pipe dream?

Pixabay

The answer has nothing to do with numbers; it hinges on sentiment. Several years after the term “omnichannel” hit the retail circuit, its pursuit has really only served to make brands more tentacular, not more meaningful or even desirable.

Back in 2014, when MIT reported $12 billion in sales were made through smartphones, and the web influenced $1.1 trillion in in-store sales, lots of retailers considered omnichannel marketing necessary for maintaining shoppers. The problem is too many used it like a tool for maximizing logistics and communications, not as a strategy for propelling the brand experience to meet channel-specific preferences.

This does not bode well for retailers trying to achieve omni marketing strategies in 2018. For all the channel cohesion omnichannel requires, there is little cohesion in what the strategy has become. Moving forward, will retailers deliver the same offers across channels, or move toward channel-specific offers and experiences that are unique and take advantage of a channel’s capabilities?

Or is the best future a mix of both?

Seeking Omni Harmony

In truth, the answer rests in the shopper’s reaction to the specific channel encounter at the precise moment she makes it. No amount of seamless integration will matter if the experience isn’t at first intriguing.

Yet brands still struggle to connect their back-end and front-end, customer-facing systems, said Ulf Tillander, global industry director of retail and wholesale at IFS, a software firm.

“The challenge … will be in harmonizing the digital and physical sides of their businesses to create unique customer experiences in-store,” he wrote in an email.

But what’s the correct experience, when should it be deployed and where? As Katie Smith, retail analysis and insights director at the retail analytics firm Edited, put it: “There now needs to be a meticulous and unique approach for offline versus online, both at the point of purchase and at the point of collection.”

Six Questions

Let’s put that to the test. This quiz can help gauge a brand’s omnichannel preparedness in 2018.

Q: What is your investment in digital compared with your investment in physical stores?

Unless a retailer plans to close all or the lion’s share of its stores, it should be investing in both its physical and digital channels and experiences. Most shoppers under the age of 45 (60%) first look online and then buy products in-store, according to a 2017 report by Alliance Data. In this capacity, digital channels should be used like front lawns in home tours – as curb appeal. The store should top off that experience.

Q: What does your long-term omnichannel strategy look like?

A multiyear program should be informed by a mix of data that reveals how shoppers interact with the brand’s many touch points so it can guide appropriate investments into preferred channels. This entails looking deeper than even core shopper segments. While useful for setting broad strategies, machine learning and artificial intelligence are enabling the retail universe to finally get to the individual level. Brands should keep this in their sights from a strategy/execution perspective in the coming years.

Q: Follow-up question: To what degree do you invest in shopper data across all channels?

Multichannel shoppers tend to spend more per transaction, but that does not mean the retailer will understand their motivations unless it has reliable data. The magic capable through artificial intelligence will be best delivered if the brand can create even more expansive views of customers and their underlying motivations. Additional customer data, from psychographic and demographic attributes to membership and loyalty programs, will help hone a retailer’s ability to identify and understand the potential motivations of its customers — and think bigger.

Q: What percentage of your budget is invested in experiences, versus product?

Omnichannel strategies could help change the expectations or roles played by different channels in the customer experience. Take a page from Nordstrom. Its inventory-free concept store, Nordstrom Local, invites shoppers to socialize with a glass of wine, indulge in a manicure, get free personal styling tips and order items to be delivered. By learning more about how customers interact with it by channel, a retailer can refine and test how to modify those experiences, while still ensuring the experience includes a way to close the deal.

Q: Do your various digital channels offer the same promotions and experiences, and how do they sync up with the in-store promotions?

There is nothing wrong with all promotions being the same, but a brand should know why the shopper chooses a specific channel and apply that understanding to promotional considerations. Shoppers at self-checkout, for example, may not be interested in receiving coupons at 6 p.m. on Tuesday when they are rushing home to get dinner on the table. A coupon at 3 p.m. on Saturday, however, may be welcome.

Q: What problems do you want to solve for the customer?

This answer comes down to examining the architecture of the brand experience by channel to ensure it is fully servicing customer expectations. Omnichannel should enable seamless customer experiences across multiple channels that may serve very different purposes in the customer’s path to purchase. However, individual customers may have different expectations of what each channel will do for them, leaving the merchant with a significant puzzle to solve.

The solution? Design an experience for the customers. Ensure the purpose of each channel in achieving that experience is clear and that digital interactions and in-store support provide the right level of data, communication and consistency so customers do not feeling like they are engaging with different brands simply because they moved across different channels.

And Your Score Is …

The answer to the quiz is basically all of the above. Omnichannel isn’t a trend; it’s a term applied to an evolution. It’s fluid.

Channels don’t matter to shoppers, unless they delight them. To this end, the most important question a retailer could ask itself is not simply where to cross the shopper’s path, but what it is doing to make her take a second look.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

January 9, 2018

18 Retail Facts Involving The Number 18, For 2018

All in all, 2017 didn’t end too poorly for retail. Sure, roughly 20 major chains filed for bankruptcy and closed thousands of stores, but online retail purchases rose 18% over last year’s Thanksgiving Day and Black Friday, and that generated $8 billion in sales.

Pixabay Images

That’s just one way the number 18 describes the frenzied and resilient world of retail. Following are 17 more facts that will shape the retail world in 2018 and beyond.

180,000: The average square footage of a Walmart Supercenter, rounded up, according to Walmart’s most recent quarterly square footage report.

18 million: The number of people in 2018 who will use voice payments through devices such as Amazon Alexa, voice-initiated person-to-person payments and voice-controlled bill payments, according to BI Intelligence.

$18 billion: The amount that mobile video ad spending is expected to reach in 2018, representing a 49% increase, according to Recode. No doubt a good percentage will be by retailers.

18th: Where Nike ranked in Interbrand’s Best Global Brands 2017 ranking. That represents a brand value increase of 8% from 2016.

Dec. 18: The day that Overstock.com, one of the first retailers to accept bitcoin, launched a $250 million Initial Coin Offering to raise funds. It made the coin offering through its exchange, tZero, according to CNN Money.

18 states: That’s how many are increasing the minimum wage in January 2018. Nationwide demonstrations by fast-food employees are reported to have contributed to the hikes, according to USA Today, but retailers also see the increase as a chance to retain talent.

Every 18 seconds: The frequency at which one package of The Body Shop’s classic Vitamin E Moisture Cream was selling worldwide just before Christmas 2017, according to the Australian website Byrdie.

18 feet: The length of the average parking spot, including those in shopping malls, according to some municipal codes. The width is a minimum of 9 feet.

18.6%: The percentage of retail and apparel companies Moody’s rates, representing 26 U.S. companies, that have a credit rating of Caa or lower, according to USA Today.

1.8.18: The date through which consumers can return Apple products purchased and received between Nov. 15, 2017, and Dec. 25, 2017, according to Apple’s extended holiday return policy. Products usually get a two-week return window.

18th place: Where TJX Cos., operator of T.J.Maxx and Marshalls, ranked on the Stores annual Top 100 Retailers list. The chain generated $33.3 billion in global annual sales, a 4% year-over-year increase, placing it behind Macy’s at No. 17.

$180,000: The price tag for a high-end version of Tesla’s new all-electric tractor trailer, which has garnered orders from Walmart, PepsiCo and Anheuser-Busch, to name a few, according to Investor’s Business Daily.

$18 million: The combined amount Walmart invested in advertising in 2017 to promote its efforts to buy American products and to train its workforce at its Walmart Academy, according to The New York Times.

$18 billion: The projected spending by U.S. consumers on Valentine’s Day gifts, goods and services in 2017, by the National Retail Federation. No word yet on 2018.

18%: The percentage of people who rank the availability of product information as important for online shopping, according to a survey by CNBC.

18 hellos: The number of low-priced Nordstrom Rack stores opened by upscale merchant Nordstrom in 2017, according to California ApparelNews.

18 goodbyes: The number of locations Ann Taylor closed in fiscal 2017, as sales at stores open at least a year fell 7%, according to securities filings by its parent company, Ascena Retail Group.

18 hours: The amount of time it took to find 18 retail-specific facts using the number 18. Can’t wait until 2019!

Happy New Year, all, and happy shopping.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

January 4, 2018

Walmart Is Investing In Shopper Data: How That Will Change The Grocery Aisle

It might not be able to put a price on trust, but Walmart is preparing to pay the fare for getting personal, and it could cost the entire food industry billions in shifting sales.

Walmart

The world’s largest brick-and-mortar merchant has acknowledged it is lagging in the quest to personalize through the use of shopper data. Now, perhaps because of Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods, which could yield unprecedented in-store and online data models, Walmart is embarking on a “multiyear journey” to get its data in good enough shape to produce relevant personalized experiences.

“From 1 to 10 in our use of data, I would say we’re probably about a 2,” Doug McMillon, president and CEO of Walmart, recently told attendees at its annual investor conference. “We use data to improve in-stock and replenish. We don’t use data to personalize.”

Walmart’s declaration isn’t kicking off the race toward data-enabled personalization, but it ensures it is not a race for amateurs. In addition to Amazon’s ambitious leap into expanded grocery analytics through Whole Foods, Kroger is using its data to reset and refine assortments, store by store, in an initiative called Restock Kroger. Albertsons, meantime, has expanded its work with analytics firm IRI to combine its in-store data with supply-chain data, enabling it to collaborate with vendors in real time.

Such efforts may be overdue. Grocers and food retailers have lost 29% of their market since 1992, according to a November report by market research firm International Data Corp. (IDC) and retail analytics firm Precima. That translates to $310 billion in lost annual revenue.

Shifting Dollars Mean Big Change

Where is the money going? To recreational venues, the workplace, universities and fast-casual restaurants, which are marketing catering services to families, according to the report. Among the findings:

A quarter of shoppers (growing to 32% within two years) satisfy their grocery needs by shopping at multiple stores.

More than 40% of families shop groceries online at least once a month.

Perhaps as a result, 79% of supermarket chains said they are changing their assortments and space strategies in the centers of their stores.

Across age groups, shoppers expressed an interest in personalized prices, promotions and in-store experiences.

Yet most retailers that use advanced data insights — 55% — said they are not where they need to be with their analytical tools.

Walmart Weighs In Change

All of which means supermarket retail is about to get real on data-enabled personalization, and this could sharply change the shopper experience.

Walmart, for example, is actively seeking to build trust and loyalty through its data refinement. “You can imagine use cases that will save customers time and have them actually understand that we do understand them to an extent,” McMillon said, “all those things done in a way that builds trust with them, which is our ultimate asset.”

To this end, Walmart has partnered with the data firm Nielsen to smooth out the way its data is used among manufacturers, vendors and business partners. A goal of the program, called Walmart One Version of Truth, is to provide supply chain partners a consistent view of the market so they can leap on opportunities that cut costs and also improve the shopper experience.

It won’t happen quickly — McMillon acknowledged it could take years to organize Walmart’s data so it can be effectively used for personalization. In the interim, other large merchants, as well as regional chains, are boning up on their analytics practices and putting the findings into play.

3 Changes to Expect

The outcome of these analyses will entail changes that shoppers should easily recognize. Among what they can expect:

Fresh change: Increased online grocery shopping means certain categories, specifically shelf-stable condiments and household goods, will be purchased less in the store. As a result, grocers are almost uniformly reconsidering how they allocate space, and many are expanding their fresh food offerings. More than seven in 10 supermarket retailers (72%) are changing assortment and space in the produce sections, according to the IDC/Precima research. This is despite that just 51% see the category as important. Note: While the middle of the store is being reconfigured, regionally produced items will likely take the place of staple products.

Online in store: But there’s no reason for those staple sales to go to a competitor. In-store touch screens can offer endless aisles of shelf-stable foods (like flour, salad dressings and candy). Shoppers can place orders while at the store, and the products can be delivered as soon as the next day. In some cases, store space could be reconfigured to allow for more warehousing, which is less expensive to maintain, and products stored in the back could be brought to the front in time for checkout. Shoppers are ready: 47% of U.S. consumers said they would use auto-replenishment for household items such as soap, according to research by Accenture Strategy.

Hyper-personalized promotions: As more supermarkets partner with data firms to combine supply-chain and in-store data, their understanding of what sells, why and under what conditions will improve, and will be reflected in more relevant communications. Kroger’s loyalty program and purchase data, for example, help its suppliers deliver targeted ads in Kroger stores and online. Kroger’s agreement to introduce a mobile wallet in 2018 through JPMorgan Chase could enrich its insights into shopper behavior outside the store. These finer analytics could enable merchants to identify promotional opportunities before the shopper visits the store or website.

These efforts could bring straying shoppers back into the supermarket, but merchants must move fast or pay the price of lost opportunity. With so many food dollars spent outside the grocery store, the industry is already in catch-up mode.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

December 21, 2017

The Benefit Of Unlimited Offers: Dollars Or Data?

You’ve just paid $100 for a bottomless bowl of pasta. When it comes to measuring the return on that investment, however, the formula is more likely to involve an accumulation of bytes than bites.

Photographer: Daniel Acker/Bloomberg

This is what some merchants may be betting on as they turn to unlimited offers to increase their market share. So far, shoppers are biting:

Olive Garden in September reissued its $100 Pasta Pass, which allows holders access to unlimited bowls of pasta for eight weeks. It sold out of 22,000 passes in less than one second.

Smashburger’s 45-day Smash Pass is a ticket to $1 entrées once a day every day from Jan. 1 to Feb. 14. It follows the 54-day Smash Pass, introduced in October, which offered the same from 15 through Jan. 9 (except Christmas and Thanksgiving). Shoppers have to pay in advance, so the total cost could be $90 or $108.

Starbucks has since 2011 offered an annual Coffee Refill Tumbler at varying prices. In late 2016 it introduced the $40 refill tumbler, which buyers could fill up daily with coffee and tea during January at no additional charge. The tumbler returned in 2018 in select stores but may have sold out — some are available at third-party outlets such as Amazon and eBay, but for higher prices.

GameStop in October announced a $60 PowerPass, which would let customers rent an unlimited number of used games for six months. It suspended the program during a soft launch in mid-November, however, due to “program limitations” that may involve its computer systems.

And the company MoviePass, which is built on a model of selling $9.95-a-month passes for unlimited pictures, in mid-November offered a limited-time, one-year plan for $6.95 a month. The cinema chain Cinemark responded with an $8.99 monthly pass called Movie Club that’s good for one movie per month plus a 20% discount on concessions, as well as other benefits (unused tickets roll over and never expire).

These brands join a number of others, from car washes to theme parks, that are banking on unlimited offers to improve perceived value and encourage more frequent visits. And with each offer, the size of the bargain escalates to double-take proportions.

How can brands make money by giving so much away? It’s likely they have a clear view, supplied by their shopper data, that while, sure, a few customers will be money-losers, there will be an overall gain in net sales, profits and customer activity. Let’s explore how.

Scratching the Surface of Bottomless Deals

Unlimited offers attract customers through value deals that seem crazy — on the surface. Smashburger, for example, estimates that just 10 burgers would cover the cost of one full Smash Pass (at an average burger price of $6.70). The Starbucks Refill Tumbler, at $40, would more than pay for itself with 20 drinks.

And the limited-time MoviePass, at $6.95, is less than the cost of one admission at many theaters.

But below the surface is a second revenue stream upon which these brands are counting — the related purchases that would otherwise not be made, such as for concessions at the theater, dessert at a restaurant and added meals or tickets for friends and family. Each organization’s data could indicate how likely their customers are to buy adjacent categories or bring companions into the stores or restaurants. It’s like a BOGO, but the plus-one adds profitability.

As the brands parlay these insights into more targeted promotions and communications, a virtual cycle of understanding will ensue. It all starts with consulting their data to assess the full value of such seemingly crazy offers.

Unlimited Data Returns, in 3 Steps

Which brings us to the essential point: If brands follow the basic rules about working with data, they will gain a sharper awareness of how such bountiful offers will play out among their customer base. Even test runs should be harmless if the data is used as a guide. Here’s how:

Collect only the data needed. Big data does not mean more data; it means using the right data. The brand should determine exactly what it wants the data to accomplish. Is it to grow the customer base, test a new service or improve overall marketing investments? Once the purpose of data collection is determined, the organization’s analytics team can localize the specific information required to realize that goal.

Be transparent. From the start, the organization should share with its offer members the data it collects, how it uses the information and why. The “why” should include how the customer will benefit. If it is that their choices will help the brand make future menu decisions, they’ll likely want to know that. If the benefit is they’ll receive fewer unwanted email ads, just say so. Shoppers value honesty.

Respect the data. Brands should use the data they collect only as described, and hold on to it only as long as needed. In the interim they could share it across the organization so each department can find ways to maximize the ROI for the customer, because they know their data is an investment in a brand. Shopper data can help an organization more accurately determine better price points, identify pain points and refine its services.

It all comes down to aligning the brand’s priorities with those of its best customers. People like a good deal, but they do not come with unlimited quantities of trust or patience. Brands that offer bottomless offers will succeed when they believe the price of that deal is long-term loyalty, not limited-time transactions.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

December 19, 2017

10 Retail Predictions For 2018 That Should Be On Your Radar

Imagine the 21st century is a consumer. She’s approaching her 18th year, she’s got the world at her fingertips and she wants it all to fall into her hands. This includes purchasing. Yet she couldn’t tell you where or how she will shop tomorrow, or even in the next hour.

Pixabay

And that will largely shape the world of retail in 2018. Like a person who suddenly reaches adulthood, retail’s basics are the same, but its responsibilities are rapidly transforming. In particular, since shoppers are demanding difference — in terms of product, experience and location — this will trigger surprising shifts, and risks, in 2018.

They shouldn’t be that unexpected, though, considering what we can see from shopper data and behavior of the past few years. Still, shoppers might be surprised by the revisions they have put into motion.

I asked some industry experts what they see coming, and added a few of my own ideas. Following are 10 predictions for 2018.

Pop-in-path retail: Rather than wait for shoppers to find time to visit their stores, more merchants will step into the shopper’s path to purchase, said Wendy Liebmann, CEO of WSL Strategic Retail, a global retail consultancy. “It’s evidenced at the McDonald’s McCafé in Manhattan, where visitors can place and pay for orders by touchscreen, and Walmart’s endless aisle of toys, accessible through a kiosk in its Orlando, Florida, store.” Other retailers are reformatting stores with quick-hit items right inside the door. Target’s next-generation store in Richmond, Texas, includes two entrances, one expressly for online pickups or grab-and-go food items.

Mail will scale: The delivery industry will become increasingly competitive within retail, predicts Stefan Weitz, executive vice president of technology services at Radial, an ecommerce fulfillment company. “In order to keep up with the growing expectations set by Amazon, some retailers (will begin) to contract out their own fulfillment networks, meaning they’ll choose a partner company to maximize delivery speeds and save costs on distributing orders,” he said. “Overall, the broader industry will be required to digitize and take on another level of sophistication to achieve the agility required to remain a competitive partner of retailers.”

Price will gain weight: Brands will explore new ways to use price, outside of discounting, to attract customers, predicts Katie Smith, retail analysis and insights director at Edited, an international retail analytics company. “While some discounting is healthy and necessary, retailers have found that a long-term dependence on markdowns dilutes a brand’s value and erodes confidence,” Smith said. Strategies would include giving online discounts when customers remove the “free returns” option or when shoppers buy multiple items (like with Jet.com). Some brands will align with consumer value for transparency in supply chain costs, as does Everlane.

Bricks-and-data: Retailers will invest more in capturing localized data. Target plans to complete building 32 locations before the end of 2017, many of which will be small formats that could collect hyper-local data to be used for better-tailored assortments. Similarly, Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods provides insight into how customers shop in store, complementing its leadership understanding of online behavior, said Brian Ross, president of retail analytics firm Precima. “As a passionately customer-centric retailer, Amazon understands that customers shop differently online than they do in store, and that retailers of tomorrow will define omnichannel as providing the most relevant, convenient and value-based offering in all channels.”

Shop, dine, live: More consumers will literally live “above the shop” as malls add housing in a bid to maintain relevance, said Pam Danziger, researcher at Unity Marketing and author of the book “Shops That Pop!” “There are two huge demographic groups — baby boomers on one side and millennials on the other — with equally strong demand for affordable, accessible housing. This is where struggling mall properties can find a new lease on life,” she said. Effectively, it creates a vertical neighborhood or (in my words) “communicity” that serves the retail community. Danziger sees this strategy suitable for vibrant malls as well.

Department, deconstructed: As department stores struggle to retain (or regain) relevancy, they will take surprising risks. Saks Fifth Avenue’s noteworthy approach is to pull several key merchandise segments — shoes, jewelry and contemporary fashion — into separate specialty stores. The three shops, in Greenwich, Connecticut, follow Saks’ redesign of its flagship store in Manhattan, to include an entire floor dedicated to wellness. Dubbed Saks Wellery, it includes a salt therapy room, salons, stretch classes and body sculpting, as well as apparel.

Living labs: Retailers will make greater investments in designated innovation labs to evaluate the latest in artificial intelligence, augmented reality, blockchain and other technologies, said Toby Olshanetsky, cofounder and CEO of prooV, a firm that helps companies test new technologies before implementation. Walmart, for example, launched an innovation hub in Silicon Valley, a startup incubator called Store No. 8 in Los Angeles and two next-gen test stores to evaluate new technologies. Smaller retailers, meanwhile, will collaborate with tech startups to gain a competitive edge.

Limited limitless offers: Several brands, including Smashburger, Olive Garden and MoviePass, closed 2017 with limited-time offerings of limitless purchases, selling hundreds of burgers, pasta bowls and screenings for a flat price. In exchange for super-low prices, they get repeat customers and all the insights from those shoppers’ membership data. Other brands, large and small, are likely paying close attention, and what may have been viewed as crazy giveaways could become the norm.

Pain-point resolutions: From razors to sofas, more products are being designed and merchandised to resolve overlooked pain points rather than presumed shopper needs. Casper notably achieved this with pop-up mattresses that arrived in easy-to-transport boxes. Sofa manufacturer Burrow fairly duplicated the model with its ready-to-assemble couches (no tools needed) that arrive in easy-to-transport boxes. Spotting a resolution to the thorny issue of assembly, Ikea acquired TaskRabbit.

Accountable labels: Based on Whole Foods grocery predictions, food suppliers and manufacturers will offer greater transparency regarding their ingredients, with labels claiming to be GMO-free, responsibly grown and Fair Trade, to name a few. Making these claims requires the brands to live up to them, meaning more food suppliers will change their ingredients to meet consumer demands. Upcoming required changes to food labels, to include listing the amounts of added sugars in nutritional facts by mid-2018, is also pressuring big brands to adjust their ingredients and seek healthier alternatives.

What do you think? Send your predictions for 2018 and we’ll save them for a future post.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

December 15, 2017

The $756B Wake-Up Call: It’s Time To Give Shoppers Control Of Their Data

For a lot of shoppers, sharing data is like writing a Christmas list that’s poorly understood. You provide details of what you want most (virtual reality headset!), drop a few added hints (I love VR!) and then wait with excitement for the gift to arrive — only to unwrap a DVR.

Photographer: Shiho Fukada/Bloomberg

This disappointment cost companies $756 billion in 2016, as 41% of consumers switched brands due to poor personalization efforts and lack of trust, according to recent research by Accenture Strategy. Nearly half the respondents of the survey, which explored sentiment about technology-driven experiences, are bothered about data privacy when using intelligent services such as digital assistants. Two-thirds wish companies were more transparent about how their information is used.

Accenture advises that to regain trust, companies could give their customers complete control of their data. This is not a new concept, and it hasn’t gone completely unanswered. For a number of years, startups have emerged, to varying degrees of success, with the goal of giving consumers greater control of their information, even monetizing it.

However, control alone won’t necessarily put right the lack of understanding that results in poor personalization efforts. Rather, it takes a dialogue.

3 Firms That Empower(ed) People

That being said, offering control is a start, and it’s a gift consumers would likely reciprocate. A 2013 survey by LoyaltyOne revealed 72% of consumers would willingly provide more information if they had control over it.

The challenge is providing shoppers the tools necessary to make the most of that data. This extends beyond managing it — shoppers should also be encouraged to lay out their expectations and gain feedback so all parties are wise to what the shared information could accomplish.

This is evidenced in the firms created to give consumers more control:

Enliken: Founded in 2013, this visionary startup launched a transparency platform for data collectors that gave consumers power over how their personal data was used. In return for sharing they gained points that could be exchanged for digital content. Enliken folded in 2014, possibly because consumers were still uncomfortable with the prospect of online surveillance.

Digi.me: This UK-based personal data collection company, founded in 2009, empowers consumers to choose with whom to share their data and how. Users download Digi.me to their devices, choose a personal cloud to store their information and the service instantly organizes the data stream. The user can then decide whether to share her data with different apps.

Telefónica: The German telecommunications firm in the spring entered a partnership with U.K.’s People.io to launch an app, called 02 Get, which lets users manage and benefit from some of their data. This is a big deal because mobile service providers collect massive, nearly constant, amounts of data. 02 Get stores profile information based on users’ answers to survey questions and other interactions. For this and other activities the users are paid in credits that can be exchanged for gift cards. Users may, for example, choose to allow location data tracking, to interact with ads or to sync their email accounts with the app.

Time to Share: 2 Necessities for Shared Personalization

A few years ago such companies may have been ahead of their time, but as artificial intelligence and machine learning assume a greater role in the shopper experience, that time is soon coming to pass.

According to the Accenture research, 43% of consumers worry that intelligent services, such as reordering technology like Alexa, will get to know them too well. This is despite the fact that 36% use such digital assistants.

“Customer concerns will inevitably rise, so it’s critical that companies have strong data security and privacy measures in place, they give customers full control over their data, and are transparent with how they use it,” Kevin Quiring, Accenture Strategy managing director and lead of advanced customer strategy, North America, said in a statement.

Giving consumers full control of their data is just a starting point. The follow-through is of more crucial importance if a brand’s aim is to deliver effective personalized experiences and gain trust. Accomplishing this requires two key elements:

Conversation: There is a role for consumers in the data-transparency process, and that is to provide their consistent, open feedback. Retailers can spark up the conversation by asking shoppers, “Hey, did we get it right?” In short, transparency works best when all parties participate, and it only serves the customer well if the customer has an active and understood role.

Flexibility: Retailers should consider in advance, based on past shopping behaviors or by surveys, what kinds of information their target customers will share, how they would want it handled and what benefits they expect in exchange for it. With this expectation, retailers could answer the question: Can we comply? If not, they should look at what they can offer.

Consumers have pretty much gained control of the purchase experience; it’s reasonable they will want control of the data-sharing relationship as well. Retailers that anticipate their customers’ expectations, and what they want in exchange for their data, will be in a better position to gain their trust. That in itself is a gift whose value all parties could appreciate.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

December 12, 2017

Sales, Shmales; Return Policies Could Define This Holiday Season

A distinct message is arising from the purr of retail traffic this holiday, and for merchants paying close enough attention it is this: Delivery is a two-way street.

Photographer: Daniel Acker/Bloomberg

Retailers expect shoppers to return 13% of purchases during this holiday season, according to the National Retail Federation (NRF); that’s up from 8% in 2015. However, even more shoppers — particularly online shoppers — are choosing where to buy based on how easy it is to return an item, or deliver it back.

Two-thirds of shoppers review an online merchant’s return policy before making a purchase, according to research by UPS, and 15% abandon their carts when the policy is unclear.

These deserted carts represent more than unrealized sales; they also stand for the next big make-or-break feature for retailers: the return experience. From Wal-Mart to a startup by former Nordstrom executives, more merchants are finding opportunities to stand apart in the return process, by elevating it from a necessary evil to a recognized asset of the purchase experience.

Bellying Up to the Return Bar

Perhaps the most innovative concept in transforming the return experience springs from a standard-bearer in customer service: Nordstrom.

Happy Returns, co-founded by former Nordstrom executives David Sobie and Mark Geller, operates a network of “return bars” where online shoppers can bring items purchased from a variety of participating brands, including Everlane, Paul Evans, City Chic and Mizzen and Main. The service, available in partner malls and stores in 14 metro areas, is free and does not require receipts.

Sobie, Happy Returns’ CEO, said a September survey of 1,800 shoppers shows the return process is a barrier to sales, especially online. “Twenty-eight percent of shoppers say that they shop online less than they would otherwise because they don’t want to deal with the hassle of returns,” he wrote in an email.

Of the same shoppers, 73% said the return experience is their least favorite part of online shopping.

What do shoppers want in a return experience? For online purchases, they want free returns, immediate refunds and no required printing, he said.

Or they prefer to make their returns in the store. Case in point: Six months after Nordstrom launched a program that allowed shoppers of its brand HauteLook to make returns at Nordstrom Rack stores, 75% of HauteLook returns took place there, Sobie said.

Wal-Mart, Apple Also Improving Return Options

Most brands that operate physical and digital showrooms, such as DSW, Best Buy and Macy’s, allow shoppers to buy online and return in store. However, operating an online-only entity whose purchases can be returned at a brick-and-mortar sister brand is different: It opens opportunities for added sales by encouraging the return traffic. Retailers can learn from this.

Here’s what a few other merchants are offering to make givebacks less daunting.

Return to technology: Several apps, including Slice and ReturnGuru, make the return process easier by managing receipts and sending expiration warnings. Wal-Mart, however, decided to make its own app. Its Mobile Express Returns, launched in October, enables shoppers to enter the information required for a return. They then can make a breezy transaction in designated express lanes at the store.

Extensions: Major brands including Amazon and Apple have lengthened their return deadlines for the holidays. Amazon’s normal 30-day return period is extended to Jan. 31, 2018, for purchases made from Nov. 1 to Dec. 31. Apple extended its return policy on most products bought from Nov. 15 to Dec. 25 to Jan. 8, 2018. Typically, its items have a 14-day return window.

Prevention: Getting the gift right means never having to say, “I don’t have a receipt.” CheckedTwice.com, an online gift registry for families, offers a holiday registry that should cut down on returns before a purchase is even considered. Using Pinterest-like displays, the registries group together the wish lists and gift suggestions of all family and friends. Members must opt in or join to participate, and the service is free.

Return to Vendor, Approach Unknown?

Whether extensions and preventions soothe the pain points of returns remains to be seen. What is essential is that the policy enables the shopper to comfortably shoehorn a return into the course of a regular day. This is becoming a crucial factor for landing sales, particularly those of large-ticket items.

And if nothing else, this little fact should resonate with retailers: Shoppers who plan to make a return may also expect to do a little extra shopping. According to research by UPS, 70% of online shoppers made an additional purchase when returning an item to a store; 45% bought something extra when making a return on the retailer’s website.

Retailers are overdue in re-engineering the return policy into an integral part of a good retail experience, and those who ignore this will lose sales. A gift return could represent a shopper’s last encounter with a brand, or it could be the first. Good merchants will let a good return experience generate returning shoppers.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter for more on retail, loyalty and the customer experience.

Bryan Pearson's Blog

- Bryan Pearson's profile

- 4 followers