Ariel S. Winter's Blog, page 5

March 5, 2012

INTERVIEW: ETIENNE DELESSERT

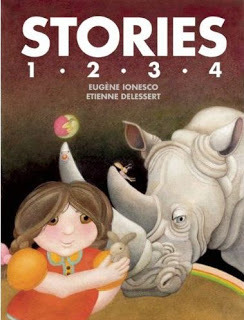

THIS IS THE MOST EXCITING THING that has grown out of We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie. In September of 2011, I received a one-line email from Etienne Delessert, the illustrator of Eugène Ionesco's children's books, among many other things. He was unhappy with the way I had handled Ionesco's books in my original posts, in particular with the inclusion of later illustrators' works alongside his own. As detailed as I try to be in my research, I knew almost nothing about the books' original publisher Harlin Quist, or that Ionesco and Mr. Delessert had a falling out with him so severe that they abandoned plans to complete the last two of the four books that had originally been contracted. I invited Mr. Delessert to clear up any inaccuracies in my posts, and agreed to move the bulk of the other illustrators' works to my Flickr account. Now, Mr. Delessert has been kind enough to answer some of my questions about the Ionesco books, which will be re-published in his approved form this May by McSweeney's McMullens. All of Mr. Delessert's responses are presented here exactly as he emailed them to me, and should not be considered reflective of my opinion or the official position of We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie.

THIS IS THE MOST EXCITING THING that has grown out of We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie. In September of 2011, I received a one-line email from Etienne Delessert, the illustrator of Eugène Ionesco's children's books, among many other things. He was unhappy with the way I had handled Ionesco's books in my original posts, in particular with the inclusion of later illustrators' works alongside his own. As detailed as I try to be in my research, I knew almost nothing about the books' original publisher Harlin Quist, or that Ionesco and Mr. Delessert had a falling out with him so severe that they abandoned plans to complete the last two of the four books that had originally been contracted. I invited Mr. Delessert to clear up any inaccuracies in my posts, and agreed to move the bulk of the other illustrators' works to my Flickr account. Now, Mr. Delessert has been kind enough to answer some of my questions about the Ionesco books, which will be re-published in his approved form this May by McSweeney's McMullens. All of Mr. Delessert's responses are presented here exactly as he emailed them to me, and should not be considered reflective of my opinion or the official position of We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie.WTWC: Why didn't you illustrate the final two Ionesco books for Quist?

DELESSERT: Quist was a talented editor and a terrible publisher. He was proud of being some kind of Don Quixote, battling the Big Houses...with a small team of an art director and an assistant. Later he expanded to France and had there a partner named François Ruy-Vidal. Both were real, vicious crooks.

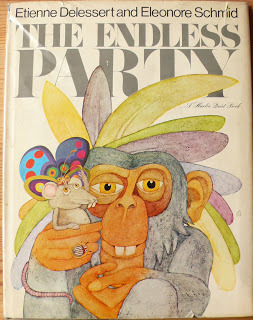

I did four books with him: The Tree, that I wrote and was illustrated by Eleonore Schmid, The Endless Party, a very laic Noah's story, and the two first stories by Eugene Ionesco. Then we realized we would never be paid for all the reprints, and worldwide co-editions. Printers and photoengravers were not paid either. We were used as decoys to convince other artists and writers to work with Quist. So Ionesco and I decided not to continue anymore, even if we had a contract for the full four stories.

The Ionesco collaboration started one day at 5 PM on an overcrowded 42nd Street in New York, near Grand Central: Quist asked me what I wanted to do after The Endless Party, suggesting I could perhaps also illustrate someone else's text.

--Bring me a manuscript of Beckett or Ionesco, I told him. He was quite startled, I remember, but two weeks later he presented my work to Ionesco in Paris. That did it. Ionesco never had written stories for children...

In fact I had thought that Eugène was going to write a long story, perhaps a modern equivalent of Alice in Wonderland, and was surprised, almost disappointed when we got the four very short texts.

I had at first no idea on how to illustrate them. I picked one of them as the first one, just because I felt there was more potential for a visual interpretation... Story Number1 became the first book of the series almost by chance.

It's only when I saw the possibility that the Jacqueline characters could not only have the same name (a world of Jacqueline...) but could also look the same that I understood how to stage the book.

I gave to the book a very cinematic rhythm. Sometimes you need images and dialogue, sometimes the story is carried only by the pictures: it was quite revolutionary at the time. Sendak or Ungerer can write wild stories, but they follow the text quite closely with their pictures (except for the rumpus of the Monsters in the Wild Things book).

The Endless Party, with all the animals and their eyes looking at you, and Story Number 1 went around the world, and had a real impact. They are considered in Europe especially, as the roots, with Where the Wild Things Are and The Three Robbers by Tomi Ungerer, of the revolution in the picture book field that began in the 1970s.

It took me forty years to finish the work, and four years ago, it was quite a challenge to go back to the same characters, the same situations of a father (Ionesco himself) telling zany stories to his little daughter, with the idea of publishing the four stories in one book with Gallimard, in France. I am happy that McSweeneys picked the book up, and will issue it this Spring, at last, in the States. I was finally going back to a fresh interpretation of the stories.

I believe that any "pirate" edition that was published, way back, by the same Quist denatured totally the spirit of Ionesco's texts.

WTWC: Why was Quist allowed to go on and use other illustrators, and to even reissue the first two books with new illustrations?

DELESSERT: After Story Number 2 was published, Quist broke the contract, without asking Ionesco or me, and instead of cleaning up his act, decided to give the illustrations to new artists, who made people believe that they did not know the ugliness of the scheme! Quist books had such a good reputation with critics and the public at the time, that artists were begging to be part of the group, even when they were warned about the perils of the venture. For me they were "collaborators" in the worst sense of the Second World War. Nobody was paid either...

WTWC: What were your feelings about your experience with Quist? What were Ionesco's?

DELESSERT: Great at the beginning. Quist was a charmer. For the first two or three years: the small group of artists was quite close. For instance, Eleonore Schmid, Rick Schreiter and I were meeting each week to exchange our experiences and dream about conquering the children's book field.

Eleonore and I were also working for magazines and some advertising, so we were able to keep going without the income of successful books, but Rick, already quite unstable, was completely broken by the Quist gang. He was one of the really great new original talents, but soon disappeared to become a homeless. Thanks Harlin and Ruy Vidal. Neither Ionesco or myself ever forgave them.

Like Boris Vian wrote:"J'irai cracher sur vos tombes!"

WTWC: What were your feelings about the reviews?

DELESSERT: Reviews were mixed: Sendak wrote that Stories 1 and 2 were some of the most original books of the decade. Some reviewers did not get it at all, just like now: intelligent criticism does not shine in the States...Some critics felt that the fact that a great playwright would write for children meant that the books were not for children! Reviews were better abroad.

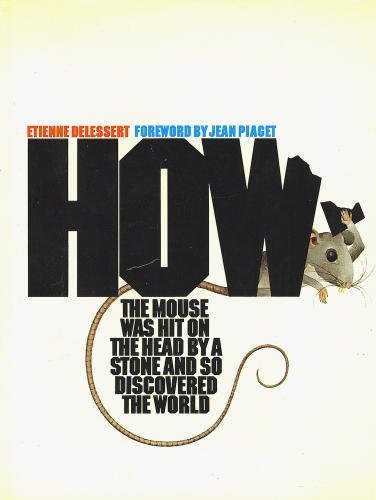

That encouraged me to visit Jean Piaget to ask for his opinion. Not only did he reassure me, but he realized that over the years he had analyzed thousands of drawings by children, but never asked how children read and understand an image made by an adult. So we worked together for eight months (in Switzerland, with a team headed by Odile Mosimann, visiting and interviewing classes) and came up with the picture book called How the Mouse Was Hit On the Head By a Stone and So Discovered the World. Piaget wrote the foreword. Published by Good Book (my imprint) and Doubleday, the book had also many co-editions. At that point, the venture even made French artists and writers tremble: would the publishers test their work before publishing it? Funny...

That encouraged me to visit Jean Piaget to ask for his opinion. Not only did he reassure me, but he realized that over the years he had analyzed thousands of drawings by children, but never asked how children read and understand an image made by an adult. So we worked together for eight months (in Switzerland, with a team headed by Odile Mosimann, visiting and interviewing classes) and came up with the picture book called How the Mouse Was Hit On the Head By a Stone and So Discovered the World. Piaget wrote the foreword. Published by Good Book (my imprint) and Doubleday, the book had also many co-editions. At that point, the venture even made French artists and writers tremble: would the publishers test their work before publishing it? Funny...WTWC: If the stories were written for Marie-France, what made Ionesco choose to publish them after she was an adult? Was it because of grandchildren?

DELESSERT: No grandchildren! Just, before I suggested it, he never thought about publishing these stories that he had kept in a notebook: it was his home theater, and Marie-France

had some great lines...

WTWC: I'm also a little confused about the order in which things were published in the U.S. versus France. In France, as near as I can tell from Amazon.fr, Story Number 3 and Story Number 4 were both illustrated by Philippe Corentin and Nicole Claveloux, but in the U.S. Corentin's illustrations were only used for Story Number 3. Why? And why weren't you able to illustrate the final two books in France? Were Quist and the French publishers bound together contractually?

DELESSERT: Cannot answer, it was a mess, and I tried not to see the books! Quist and his partner Ruy Vidal had world rights. Some of the paperbacks by Naprstek, an unknown

artist, are really despicable. I discovered them only recently. They came and went fast, a long time ago.

Quist went back to the theater production he had come from (and where the money was invested and lost?) and died. Ruy Vidal went on to other empty publishing ventures, and now is retired, and spends his time in writing very, very long defamatory letters, quite well written.

A few years ago, I went to see a Sendak show at the Morgan Pierpont Library in New York. There were only two visitors in the room: Quist and I. We did not speak.

Ionesco and I tried to sue the thieves, but Quist was very clever at having shell companies, and we gave up.

For sure Stories 1, 2, 3, 4 by Eugene Ionesco and Etienne Delessert had a very, very strange life!

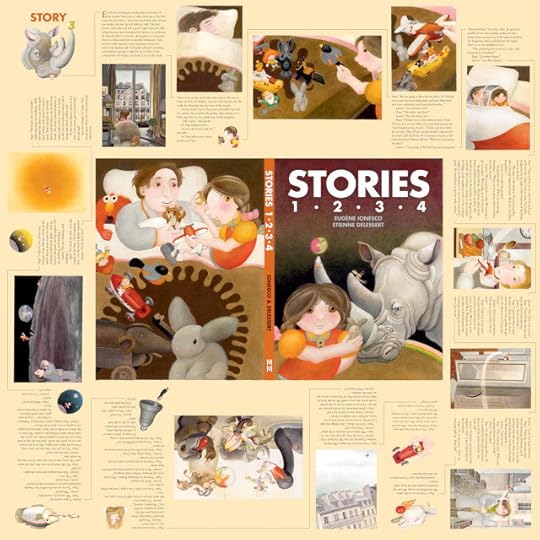

ABOVE IS A SNEAK PEEK AT THE DUST JACKET for the McSweeney's McMullens edition of Stories 1, 2, 3, 4 (courtesy of the publisher). The jacket will appear standard on the front, back, and spine (as at the top of the post), but will fold out to poster size to reveal the entire text of Story Number 3 and its illustrations (as seen here). Thank you to Brian McMullen (publisher and the brain behind the jacket design) for the image.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on March 05, 2012 17:31

February 29, 2012

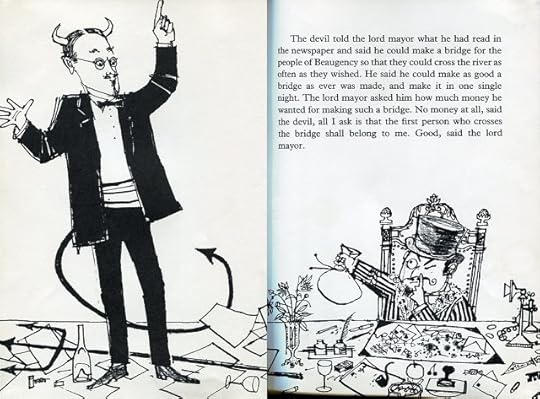

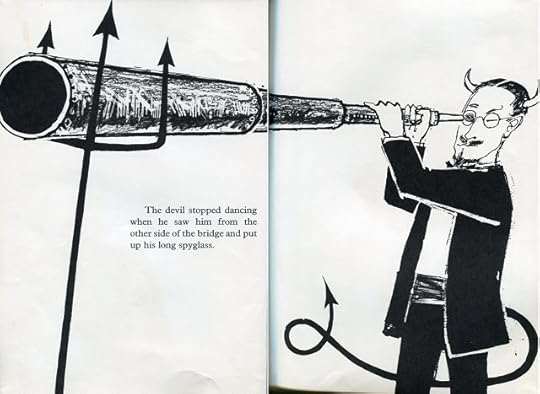

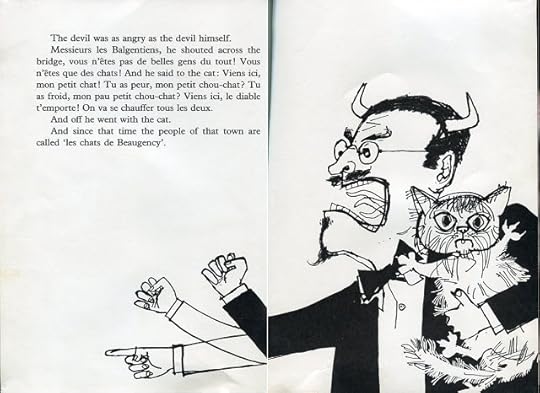

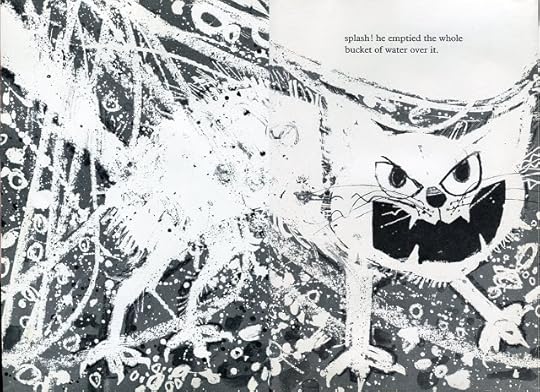

JAMES JOYCE: THE CAT AND THE DEVIL UK EDITION

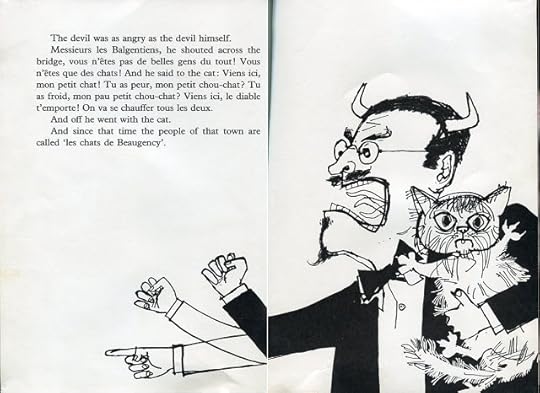

ABOUT A WEEK BEFORE news broke that a new James Joyce picture book was to be published, I discovered (through this site) that my usually exhaustive research had somehow missed an English-language edition of James Joyce's only other picture book, The Cat and the Devil: the first UK edition, published by Faber and Faber in 1965, and illustrated by Gerald Rose.

Gerald Rose shot through the ranks of British children's illustrators when he won the prestigious Kate Greenaway Medal with his third picture book, Old Winkle and the Seagulls (1960), so it is no surprise that he was handed the honor of illustrating Joyce's book five years later.

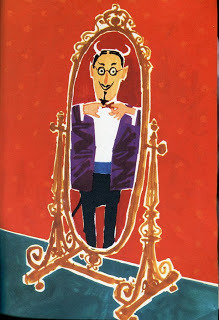

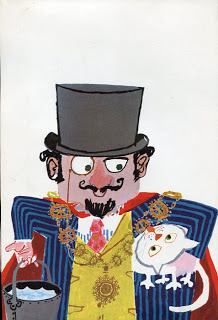

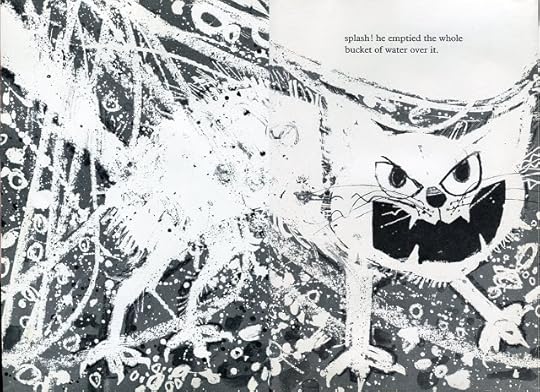

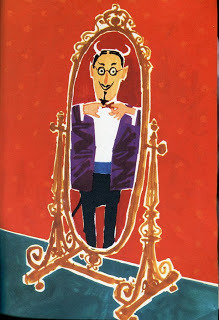

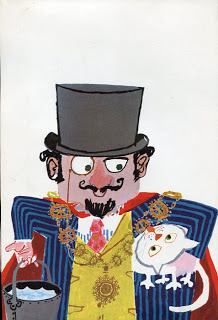

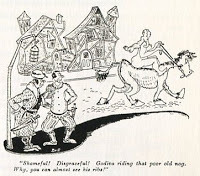

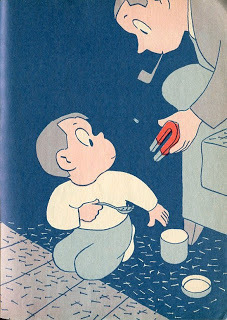

The book alternates between lush four-color paintings (which bring Maira Kalman's work to mind), and kinetic black and white line drawings.

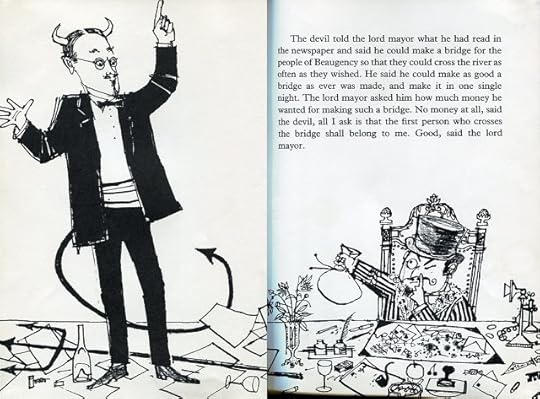

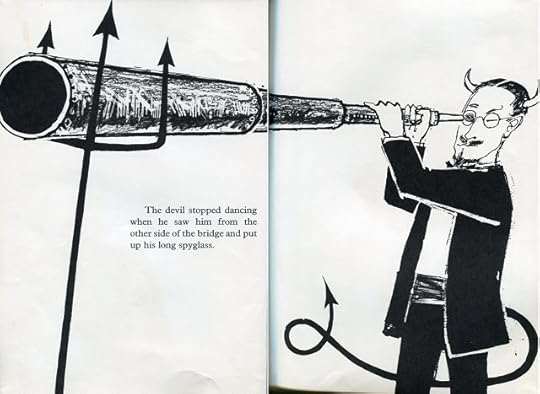

Despite the appeal of Rose's bold colors, it is in his black and white illustrations that the book really feels in sync with Joyce's text. The visual jokes and the almost sketchy line work match Joyce's storytelling and the spirit in which the story was originally written.

I will always prefer the Richard Erdoes edition, which is more consistent in its composition, but it is hard to resist Rose's portrayal of Joyce as the devil (an idea suggested by Joyce himself in his postscript).

And this cat. Of all the editions, this is the best cat.

For more of the actual story The Cat and the Devil, refer back to my very first blog post, linked up above and again right here.

(In the interim between my finding out about this edition and getting my hands on it, one of my readers, Simon Sterg over at Yahoo! 360 , also alerted me of my oversight.)

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Gerald Rose shot through the ranks of British children's illustrators when he won the prestigious Kate Greenaway Medal with his third picture book, Old Winkle and the Seagulls (1960), so it is no surprise that he was handed the honor of illustrating Joyce's book five years later.

The book alternates between lush four-color paintings (which bring Maira Kalman's work to mind), and kinetic black and white line drawings.

Despite the appeal of Rose's bold colors, it is in his black and white illustrations that the book really feels in sync with Joyce's text. The visual jokes and the almost sketchy line work match Joyce's storytelling and the spirit in which the story was originally written.

I will always prefer the Richard Erdoes edition, which is more consistent in its composition, but it is hard to resist Rose's portrayal of Joyce as the devil (an idea suggested by Joyce himself in his postscript).

And this cat. Of all the editions, this is the best cat.

For more of the actual story The Cat and the Devil, refer back to my very first blog post, linked up above and again right here.

(In the interim between my finding out about this edition and getting my hands on it, one of my readers, Simon Sterg over at Yahoo! 360 , also alerted me of my oversight.)

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on February 29, 2012 18:51

February 15, 2012

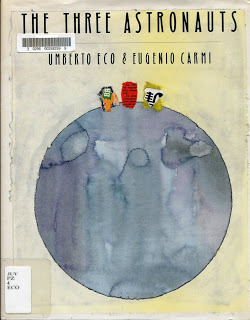

UMBERTO ECO: THE THREE ASTRONAUTS

FOR UMBERTO ECO AND EUGENIO CARMI'S FIRST PICTURE BOOK, The Bomb and the General, they tackled the Cold War arms race. For their second, The Three Astronauts, also released in 1966, they turned to the Space Race. It had been only five years since Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space in April of 1961, and the Cold War battle between the USA and the USSR to be the first nation to conquer space was still very present, with both nations setting sights for the moon. Like Eco and Carmi's first book, The Three Astronauts preaches pacifism, but with more of a focus on multiculturalism. It takes the same storybook tone as The Bomb and the General, trying to cast the Space Race in the language of fable.

FOR UMBERTO ECO AND EUGENIO CARMI'S FIRST PICTURE BOOK, The Bomb and the General, they tackled the Cold War arms race. For their second, The Three Astronauts, also released in 1966, they turned to the Space Race. It had been only five years since Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space in April of 1961, and the Cold War battle between the USA and the USSR to be the first nation to conquer space was still very present, with both nations setting sights for the moon. Like Eco and Carmi's first book, The Three Astronauts preaches pacifism, but with more of a focus on multiculturalism. It takes the same storybook tone as The Bomb and the General, trying to cast the Space Race in the language of fable. "ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS EARTH.

"ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS EARTH."And once upon a time there was Mars."

The people of Earth want to explore Mars. They send up rockets that fall back to the ground. Then they send up rockets that go out into space. Then they send up a dog in a rocket, "but the dogs couldn't talk, and the only message they sent was 'bow wow.'" So they finally send up a man.

"One fine morning three rockets took off from three different places on Earth," an American, a Russian, and a Chinese. They all want to be the first person to set foot on Mars, and none of them liked one another.

"One fine morning three rockets took off from three different places on Earth," an American, a Russian, and a Chinese. They all want to be the first person to set foot on Mars, and none of them liked one another."Since all three of them were very smart, they landed on Mars at almost the same time." They get out to explore the alien landscape, but "They looked at each other distrustfully. And each kept his distance."

Then in the dead of night, afraid and alone, they each utter their word for "Mommy," which sounds almost the same in each of their languages. So they realize they're all feeling the same thing, and choose to camp together, singing songs and learning about one another.

First thing in the morning, a Martian shows up, and he's so scary looking that all three humans band together, and point their "atomic disintegrators" at him, ready to kill him. He, for his part, finds the humans to be "horrible creatures."

Then a baby bird falls from its nest, and the astronauts and the Martian all pause, and shed a tear for such a heartbreaking sight. The Martian picks up the bird and tries to shelter it, and the humans realize he's feeling the same thing they are, and they go over and shake his hands and all of them decide to return to Earth together.

"And so the visitors realized that on Earth, and on other planets, too, each one has his ways, and it's simply a matter of reaching an understanding."

WHILE THE SUBJECT IN THE THREE ASTRONAUTS feels somewhat dated, its message is not, which is why the Family Opera Initiative is currently developing an opera based on the book. A composer from each of the three countries--America, Russia, and China--is composing music, with words by American poet Nikki Giovanni. (They're looking for donations, so do click through.)

In my post on The Bomb and the General, I went into some depth raising the question, what does Eco's text say about Eco's concept of children's literature, without offering any kind of answer. It's not often that you get an answer from the artist himself, but Eugenio Carmi sat for an interview in conjunction with the opera, which provides insight into the way in which the book was created, and how he and Eco thought about children's literature.

Coming soon: Umberto Eco and Eugenio Carmi's The Gnomes of Gnu.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on February 15, 2012 19:03

February 10, 2012

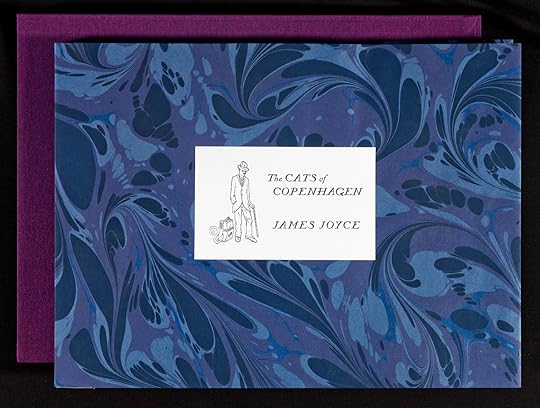

JAMES JOYCE: THE CATS OF COPENHAGEN

SEVENTY-SIX YEARS AFTER IT WAS WRITTEN, and forty-eight years after the publication in picture book form of his first children's book (We Too Were Children's first blog post ever), James Joyce has another children's book out:

The Cats of Copenhagen

.

SEVENTY-SIX YEARS AFTER IT WAS WRITTEN, and forty-eight years after the publication in picture book form of his first children's book (We Too Were Children's first blog post ever), James Joyce has another children's book out:

The Cats of Copenhagen

.If you have €300-€1200 that is.

Like his first children's book, The Cat and the Devil, The Cats of Copenhagen was written in a letter to James Joyce's grandson Stephen while Joyce was living in Denmark and his grandson in Paris. Unlike The Cat and the Devil, which originally appeared in Joyce's collected letters, The Cats of Copenhagen has not been previously published in any form. This new edition was made possible, according to the publisher Ithys Press, when James Joyce's works entered the public domain in Europe on January 1, 2012. That position has sparked some controversy, however, as the owner of the letter, the Zurich James Joyce Foundation, claims that it has yet to be determined if unpublished works are also in the public domain.

The Ithys Press edition is to be published in limited edition of 200 copies: 26 lettered, 170 numbered, and 4 Hors Commerce.

Here's hoping a popular edition will be published soon.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on February 10, 2012 08:33

February 8, 2012

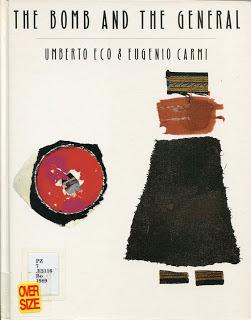

UMBERTO ECO: THE BOMB AND THE GENERAL

WHEN I FIRST STARTED WE TOO WERE CHILDREN, MR. BARRIE, one of the things I hoped to examine was the way in which an author accustomed to writing for adults conceived of writing for children. Why? Because, as many authors included on the blog have noted, childhood reading is often the reading that is most influential on a writer (or on any individual). Consequently, if a writer who is aware of the importance of childhood reading writes what he hopes will be an influential text for the next generation, how does what he includes in that text reveal what he thinks is most important to literature?

WHEN I FIRST STARTED WE TOO WERE CHILDREN, MR. BARRIE, one of the things I hoped to examine was the way in which an author accustomed to writing for adults conceived of writing for children. Why? Because, as many authors included on the blog have noted, childhood reading is often the reading that is most influential on a writer (or on any individual). Consequently, if a writer who is aware of the importance of childhood reading writes what he hopes will be an influential text for the next generation, how does what he includes in that text reveal what he thinks is most important to literature?This question takes on new meaning when it comes to the works of Umberto Eco, an author who so understands the influence of childhood reading that he wrote an entire novel, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (2005), in which the main character seeks to define his very identity from the books and comic books of his youth. Eco, most famous for his novel In the Name of the Rose (1980), first rose to prominence in academic circles as a Medievalist, philosopher, and semiotician.

Semiotics is the study of signs and their meanings. This includes the way in which words signify actual objects. For example, we call an apple by the word "apple," but a physical apple does not actually contain the word "apple." How then, does the word "apple" relate to the physical object? In what way does the word "apple" cause people to relate to the object? And how does the word "apple" function in a variety of contexts? These questions are of special importance when dealing with children, because children are only just learning about the world, and a lot of that learning is done through language acquisition. So, to a baby, the object apple is simply an observable object. But through language acquisition, it acquires the sign "apple." And as the child ages, the sign "apple" also comes to encompass secondary contextual meanings, say New York City's nickname "The Big Apple," or the symbolic meaning of an apple in the Adam and Eve story. Since so much of this learning comes from books (think of all of the "My first word..." books, which are simply photographs of objects paired with the relevant word), a semiotician writing a children's book, would not only bring concerns of its literary impact, but also of its linguistic, semiotic impact as well.

Semiotics is the study of signs and their meanings. This includes the way in which words signify actual objects. For example, we call an apple by the word "apple," but a physical apple does not actually contain the word "apple." How then, does the word "apple" relate to the physical object? In what way does the word "apple" cause people to relate to the object? And how does the word "apple" function in a variety of contexts? These questions are of special importance when dealing with children, because children are only just learning about the world, and a lot of that learning is done through language acquisition. So, to a baby, the object apple is simply an observable object. But through language acquisition, it acquires the sign "apple." And as the child ages, the sign "apple" also comes to encompass secondary contextual meanings, say New York City's nickname "The Big Apple," or the symbolic meaning of an apple in the Adam and Eve story. Since so much of this learning comes from books (think of all of the "My first word..." books, which are simply photographs of objects paired with the relevant word), a semiotician writing a children's book, would not only bring concerns of its literary impact, but also of its linguistic, semiotic impact as well.Which brings us to Umberto Eco. Almost. Eco's major contribution to semiotics is in the application of semiotics to literature. Eco expostulated the theory of "open texts" and "closed texts." An "open text" is one that allows multiple interpretations. A "closed text" dictates one interpretation. It is a question of whether a whole sequence of signs, the words and sentences that make up a story, can have different meanings than the signs usually have. Children's books, picture books in particular, are usually "closed texts." They have a specific message that is dictated to the child, a moral or lesson a child is supposed to take away from the story. Despite the myriad of interpretations his adult novels invite, Eco's picture books are no exception. They preach peace, understanding, and environmentalism.

Are you still with me? It's almost story time. I promise. Let's just go back a paragraph for a moment.

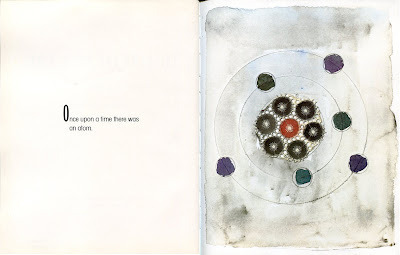

Remember the "My first word..." books? Picture = word, right? Eco's books seem at first to almost take that approach. All the books are done in two page spreads. The page on the left contains nothing but text. The page on the right contains nothing but a picture. But the picture is often abstract (see the "atom" in the spread on the left). These books don't teach words. They are highly representational. But the books' messages are closed, dictated, and even the abstract images contribute to that effect.

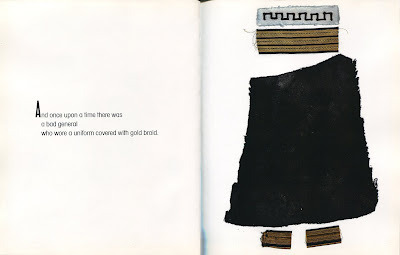

How? For that I must direct you to the article by Maria Truglio, Wise Gnomes, Nervous Astronauts, and a Very Bad General: The Children's Books of Umberto Eco and Eugenio Carmi, in Children's Literature, Volume 36, 2008, which is where I got pretty much all of my much watered-down version. Basically, while the illustrations Carmi uses are abstract, they contain their own recurring symbols--follow those little atom circles up above and the general to the right as we go forward. Those symbols then reiterate the story, reinforcing its message.

How? For that I must direct you to the article by Maria Truglio, Wise Gnomes, Nervous Astronauts, and a Very Bad General: The Children's Books of Umberto Eco and Eugenio Carmi, in Children's Literature, Volume 36, 2008, which is where I got pretty much all of my much watered-down version. Basically, while the illustrations Carmi uses are abstract, they contain their own recurring symbols--follow those little atom circles up above and the general to the right as we go forward. Those symbols then reiterate the story, reinforcing its message.And of my original question, what do all of these concerns reveal about Eco's idea of literature? I'll let you decide.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN ITALIAN IN 1966, The Bomb and the General is the first of Eco and Carmi's three picture books. Revised and reissued in 1988, the books received English translations (by William Weaver, the translator of most of Eco's novels), which Truglio notes in her essay, are sometimes interpretations of the original text in a way.

"Once upon a time there was an atom."

"Once upon a time there was an atom.""And once upon a time there was a bad general who wore a uniform covered with gold braid."

Atoms are the building blocks of the world. "Mom is made of atoms. Milk is made of atoms." And when all of the atoms are in harmony, then life is good.

But when atoms are broken, "A terrifying explosion takes place! This is atomic death."

But when atoms are broken, "A terrifying explosion takes place! This is atomic death."Well, the atom had been put in a bomb, and the general had a lot of bombs. "'When I have lots and lots,' he said, 'I'll start a beautiful war!'"

"How can you help but become bad when you have all of those bombs within reach?"

"How can you help but become bad when you have all of those bombs within reach?"The atom, along with his fellow atoms, don't want to blow up the world and cause death and destruction. So they sneak out of the bombs, which are in the attic, and hang out in the cellar.

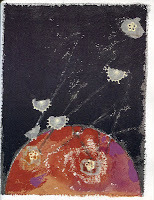

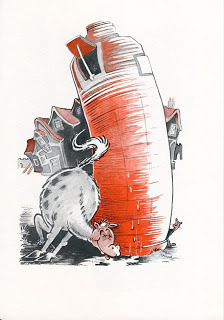

Finally, goaded by his financial backers, the general does declare war. He loads the bombs onto airplanes and starts dropping them.

The people begin to run around in a panic. "But where could they find refuge?"

But the bombs sans atoms, don't explode, and everyone is happy, and they realize life is better without war. They decide to never make war again.

"And what about the general?" He becomes a doorman at a hotel "to make use of his uniform with all the braid." Everyone treats him as a lowly menial, even people who once had to obey him, and the general is embarrassed. "Because now he was of no importance at all."

TO SEE MORE OF THE BOMB AND THE GENERAL, check out my Flickr set here. And anyone who wants to correct my discussion on semiotics or to extend it, please do. I am by no means an expert.

Coming soon: Umberto Eco and Eugenio Carmi's Three Astronauts.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on February 08, 2012 08:48

December 30, 2011

ELEANOR ROOSEVELT: CHRISTMAS

THE FIRST WORDS that come to mind when you hear the name Eleanor Roosevelt are First Lady. After that perhaps you think, founding member of the United Nations and architect of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. If you lived through her public life, you then might think: writer. After all, she wrote a daily newspaper column for twenty-six years, a monthly magazine column for Woman's Home Companion, autobiographies, and many other articles and books, making writing one of her primary professions. But children's writer?

THE FIRST WORDS that come to mind when you hear the name Eleanor Roosevelt are First Lady. After that perhaps you think, founding member of the United Nations and architect of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. If you lived through her public life, you then might think: writer. After all, she wrote a daily newspaper column for twenty-six years, a monthly magazine column for Woman's Home Companion, autobiographies, and many other articles and books, making writing one of her primary professions. But children's writer?Starting in 1932, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote or co-wrote many books for children, most of which were civic-minded nonfiction like When You Grow Up to Vote (1932), This Is America (1942), Partners: The United Nations and Youth (1950), United Nations: What You Should Know About It (1955), and Your Teens and Mine (1961). She also served on the editorial board of the Junior Literature Guild's book club, selecting monthly titles and reviewing manuscripts. And in two instances, she wrote chidren's fiction, albeit didactic fiction: A Trip to Washington With Bobby and Betty (1935) and Christmas (1940).

The former is exactly what it sounds like including a lunch with the President. The latter is an earnest and heartfelt story that first appeared in the December 28, 1940 issue of Liberty magazine. (Liberty was a weekly general interest magazine to which almost anyone of any significance contributed at one time or another. Think Albert Einstein, Joe Dimaggio, Mahatma Gandhi, etc.) Christmas 1940, to put it mildly, was not a happy time. Nazi Germany had either conquered or was about to conquer most of Europe. Japan had done the same in eastern Asia. Roosevelt, as First Lady and a humanitarian, was painfully aware of these events, and felt it was important for all Americans to be informed as well. As she put it in the 1940 Knopf first edition of Christmas:

The former is exactly what it sounds like including a lunch with the President. The latter is an earnest and heartfelt story that first appeared in the December 28, 1940 issue of Liberty magazine. (Liberty was a weekly general interest magazine to which almost anyone of any significance contributed at one time or another. Think Albert Einstein, Joe Dimaggio, Mahatma Gandhi, etc.) Christmas 1940, to put it mildly, was not a happy time. Nazi Germany had either conquered or was about to conquer most of Europe. Japan had done the same in eastern Asia. Roosevelt, as First Lady and a humanitarian, was painfully aware of these events, and felt it was important for all Americans to be informed as well. As she put it in the 1940 Knopf first edition of Christmas:"The times are so serious that even children should be made to understand that there are vital differences in people's beliefs which lead to differences in behavior.

This little story, I hope, will appeal enough to children so they will read it and as they grow older, they may understand that the love, and peace and gentleness typified by the Christ Child, leads us to a way of life for which we must all strive."

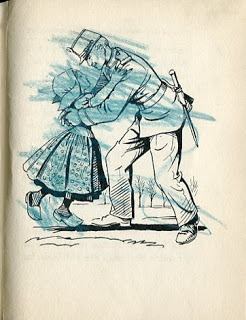

IN THE OCCUPIED NETHERLANDS seven-year-old Marta and her mother are preparing for a lonesome Christmas. Marta has her mother recount the previous year's Christmas, when her father came home from his post at the border to celebrate with them. Even then, in 1939, Marta's grandparents could not join them as money needed to be conserved for the expected lean year ahead. But her father came on Christmas Eve, St. Nicholas left her "sweets, a doll, and bright red mittens just like the stockings mother made," the whole family went ice skating, and they had a Christmas feast. Marta innocently tells of how, when she and her mother are together:

IN THE OCCUPIED NETHERLANDS seven-year-old Marta and her mother are preparing for a lonesome Christmas. Marta has her mother recount the previous year's Christmas, when her father came home from his post at the border to celebrate with them. Even then, in 1939, Marta's grandparents could not join them as money needed to be conserved for the expected lean year ahead. But her father came on Christmas Eve, St. Nicholas left her "sweets, a doll, and bright red mittens just like the stockings mother made," the whole family went ice skating, and they had a Christmas feast. Marta innocently tells of how, when she and her mother are together:At the end of the bittersweet visit, Marta's father puts on his uniform, tells Marta "'Take good care of Moeder until I come back," and leaves, never to return."'we always say: "I wonder if Father remembers what we are doing now," and we try to do just the things we do when you are home so you can really know just where we are and can almost see us all the time.'"

In the interim, along with her father's death comes the occupation of her country. "There was no school any more...and on the road she met children who talked a strange language and they made fun of her and said now this country was theirs."

In the interim, along with her father's death comes the occupation of her country. "There was no school any more...and on the road she met children who talked a strange language and they made fun of her and said now this country was theirs."In order to persevere, Marta often speaks to the Christ Child. For "God...was far away in His heaven...[but] Marta could believe...that the Christ Child...was a real child." So on St. Nicholas's Eve, 1940, knowing that "St. Nicholas will not come tonight," Marta says to her mother:

"'There is one candle in the cupboard left from last year's feast. May I light it in the house so the light will shine out for the Christ Child to see His way? Perhaps He will come to us since St. Nicholas forgot us.'"

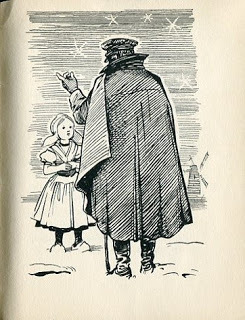

Her mother consents, Marta sets the candle in the window, and then goes outside to see just how far away the candle can be seen. Outside, she meets a man.

Her mother consents, Marta sets the candle in the window, and then goes outside to see just how far away the candle can be seen. Outside, she meets a man."She was not exactly afraid of this stranger, for she was a brave little girl, but she felt a sense of chill creeping through her, for there was something awe-inspiring and rather repellent about this personage who simply stood in the gloom watching her."When she tells him why she has come out, he remonstrates, "You must not believe in any such legend...There is no Christ Child."

Marta listens patiently to his diatribe even though "down inside her something was hurt...[The man] was taking away a hope, a hope that someone could do more than even her mother."

When she at last asks permission to return home, the man comes with her, entering the house without knocking. Marta sees at once that her mother is holding the glowing Christ Child in her arms. The man, just sees an ordinary baby. He chastises the mother for teaching her daughter "a foolish legend."

When she at last asks permission to return home, the man comes with her, entering the house without knocking. Marta sees at once that her mother is holding the glowing Christ Child in her arms. The man, just sees an ordinary baby. He chastises the mother for teaching her daughter "a foolish legend.""The woman answered in a very low voice: 'To those of us who suffer, that is a hope we may cherish. Under your power, there is fear, and you have created a strength before which people tremble. But on Christmas Eve strange things happen and new powers are sometimes born.'"She goes on in this vein and at last the man turns and leaves. But:

"The light in the window must be the dream which holds us all until we ultimately win back to the things for which [her father] Jon died and for which Marta and her mother were living."

IN THE 1986 EDITION, CHRISTMAS, 1940, Roosevelt's son Elliott Roosevelt writes in the introduction, "'Christmas, 1940' is the kind of story that is rarely written today. I suppose our tastes have changed, as has our style." Despite his hope that the message is still valid, he is right that our tastes have changed, and Christmas now reads as heavy handed and didactic. And while that usually does not bother a young child, the subject matter is now too distant to make this a Christmas tradition.

IN THE 1986 EDITION, CHRISTMAS, 1940, Roosevelt's son Elliott Roosevelt writes in the introduction, "'Christmas, 1940' is the kind of story that is rarely written today. I suppose our tastes have changed, as has our style." Despite his hope that the message is still valid, he is right that our tastes have changed, and Christmas now reads as heavy handed and didactic. And while that usually does not bother a young child, the subject matter is now too distant to make this a Christmas tradition.THE ILLUSTRATIONS used throughout this post come from the first edition and are by the graphic designer and illustrator Fritz Kredel. In addition to the 1986 edition, there was a 1963 edition entitled Eleanor Roosevelt's Christmas Book that also included Roosevelt's reminiscences of Christmas at Hyde Park and the White House. For background information, I consulted the Eleanor Roosevelt Encyclopedia. The photo of the book jacket comes from the Bauman Rare Books website.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on December 30, 2011 13:50

December 27, 2011

HAPPY HANUKKAH: GUEST POST ON VINTAGE KIDS' BOOKS MY KID LOVES

JUST IN TIME for the final candle, I have a guest post over at the magnificent

Vintage Kids' Books My Kid Loves

: The Adventures of K'Ton Ton by Sadie Rose Weilerstein. Look out for a new We Too Were Children post before the end of 2011. Until then, hop on over to Vintage Kids' Books to finish up your Hanukkah celebration.

JUST IN TIME for the final candle, I have a guest post over at the magnificent

Vintage Kids' Books My Kid Loves

: The Adventures of K'Ton Ton by Sadie Rose Weilerstein. Look out for a new We Too Were Children post before the end of 2011. Until then, hop on over to Vintage Kids' Books to finish up your Hanukkah celebration. All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on December 27, 2011 14:09

November 21, 2011

GUEST POST TODAY AND TOMORROW ON VINTAGE KIDS' BOOKS MY KID LOVES

IN CASE YOU HAVEN'T GOTTEN enough Muppets the last few weeks, I'm bringing a daily dose today and tomorrow over at

Vintage Kids' Books My Kid Loves

. Today, my childhood copy of the photo-adaptation of the original The Muppet Movie (1979). Tomorrow, the first issue of The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984) comic book mini-series. And if you've never been there, you get the added bonus of seeing Burgin Streetman's excellent blog. Subscribe.

IN CASE YOU HAVEN'T GOTTEN enough Muppets the last few weeks, I'm bringing a daily dose today and tomorrow over at

Vintage Kids' Books My Kid Loves

. Today, my childhood copy of the photo-adaptation of the original The Muppet Movie (1979). Tomorrow, the first issue of The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984) comic book mini-series. And if you've never been there, you get the added bonus of seeing Burgin Streetman's excellent blog. Subscribe.All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on November 21, 2011 13:45

November 17, 2011

GOOD NIGHT, WENDY: DR. SEUSS

THEODOR SEUSS GEISEL, better known as Dr. Seuss, worked in every possible field that requires writing and drawing. There were the children books, of course, but he also did cartoons and parodies for humor magazines, advertising (most famously for Flit insecticide), book illustration, a syndicated newspaper comic, pamphlets (for propaganda and for causes), political cartoons for PM, the Private SNAFU propaganda cartoons (conceived by Frank Capra, many directed by Chuck Jones and Fritz Frelang, and co-written by P. D. Eastman and Munro Leaf), an Academy Award-winning documentary, Academy Award-winning cartoons, a live-action feature-length musical, magazine stories, animated television specials, and fine art. But throughout his varied career, Geisel reserved his Dr. Seuss persona for his children's work exclusively. Except once (okay, twice, but we'll get to that). The third book by Dr. Seuss was about naked women.

[image error]

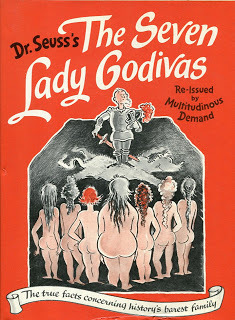

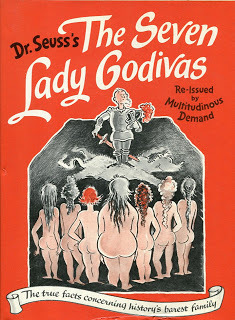

ONE REASON DR. SEUSS worked in so many fields was that he never felt that any of them were respectable enough. This went for children's books too. In the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine review of The King's Stilts, he told his college friend Alexander Laing that it was his "annual brat-book." With two such "brat-books" under his belt, Geisel wanted to expand his purview. So when Random House co-founder Bennett Cerf lured him away from Vanguard in 1939, it was under the condition that Geisel be allowed to do an "adult" book first. That book was The Seven Lady Godivas.

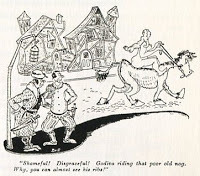

The Lady Godiva legend, of dubious origin, states that in 1037, the Earl of Coventry's wife rode naked on horseback through the streets of Coventry in protest against her husband's unfair taxes. In a later sanitized version of the story, the citizens of Coventry were ordered to remain in their shuttered houses during the ride, but one man looked out, Peeping Tom. He was then struck blind.

The Lady Godiva legend, of dubious origin, states that in 1037, the Earl of Coventry's wife rode naked on horseback through the streets of Coventry in protest against her husband's unfair taxes. In a later sanitized version of the story, the citizens of Coventry were ordered to remain in their shuttered houses during the ride, but one man looked out, Peeping Tom. He was then struck blind.

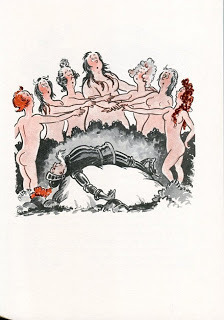

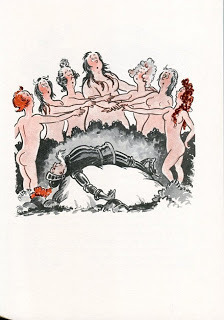

Geisel had turned to Godiva as subject twice before in cartoons in the late 1920s (see left). And there had been other instances of nudity in his art, such as his take on the rape of the Sabine women, which hung in the Dartmouth Club for many years. That legend also had bearing on The Seven Lady Godivas as a parody by Stephen Vincent Benét entitled The Sobbin Women appeared in Argosy in 1938 with many of the same story elements that Geisel would use in his own book, namely seven women barricaded in a building refusing to marry their seven suitors. The similarity between the two stories along with the use of a sexually charged legend certainly suggests that Geisel was aware of the story of the previous year. (The Benét later served as the inspiration for the 1954 musical film Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. In another link between the stories, Geisel flew to New York in 1954 to discuss a musical based on The Seven Lady Godivas, which never came to fruition.) So how did one Lady Godiva become seven?

These Lady Godivas are naturists who didn't waste time on "frivol and froth." On May 15, 1066 their father set out for the Battle of Hastings on horseback. ("True, Lord Godiva had been experimenting with these animals for years. But the horse remained a mystery...") Before he is out of the castle gate, Lord Godiva's horse throws him, and "the old warrior was dead" on impact. His seven daughters take a pledge that day:

These Lady Godivas are naturists who didn't waste time on "frivol and froth." On May 15, 1066 their father set out for the Battle of Hastings on horseback. ("True, Lord Godiva had been experimenting with these animals for years. But the horse remained a mystery...") Before he is out of the castle gate, Lord Godiva's horse throws him, and "the old warrior was dead" on impact. His seven daughters take a pledge that day:

"'I swear,' swore each, ' that I shall not wed until I have brought to the light of the world some new and worthy Horse Truth, of benefit to man.'"

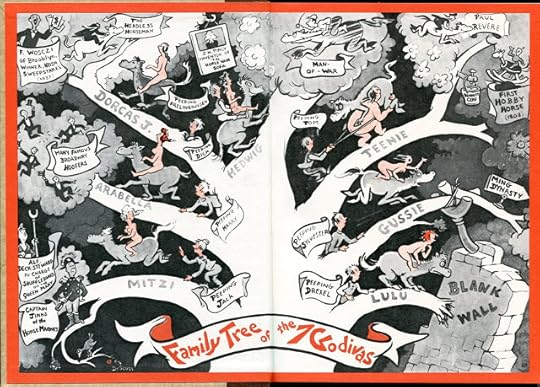

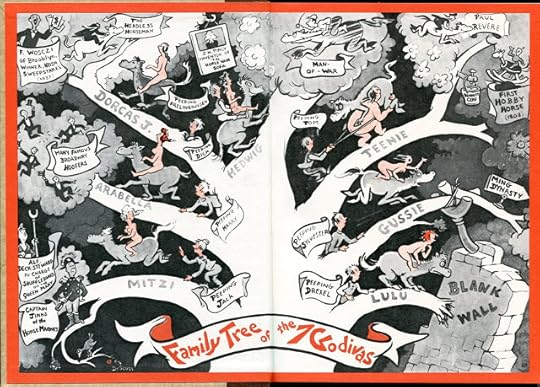

All seven sisters (Clemintina, Dorcas J., Arabella, Mitzi, Lulu, Gussie, and Hedwig) were engaged to the seven Peeping brothers (Tom, Dick, Harry, Jack, Drexel, Sylvester, and Frelinghuysen), so this was no idle oath. The sisters lock themselves in the castle, Hedwig, the eldest, makes a book with seven pages in which each sister is to inscribe her Horse Truth, and the scientific study begins.

The first Horse Truth ("Don't ever look a gift horse in the mouth!" Discovered after Teenie Godiva gets her nose bit off by the "mare Uncle Ethelbert gave us last Christmas.) is found that very first day. The final Horse Truth ("Don't lock the barn door after the horse has been stolen." Discovered after just that has happened.) isn't found until forty years later, New Year's Day 1106. In between, the girls work through their stable, subjecting horses to carriages above, below, before, and aft ("Don't put the cart before the horse."), driving them to drink ("fermented mash") through nervous exhaustion (the cure for which would be water, but "You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him drink."), powering treadmill equipped boats (sea horses, of course, although "Never change horses in the middle of the stream."), kicking (that leads to the discovery of a lost diamond stickpin; "Horseshoes are lucky."), and getting painted ("That is a horse of another color!").

The first Horse Truth ("Don't ever look a gift horse in the mouth!" Discovered after Teenie Godiva gets her nose bit off by the "mare Uncle Ethelbert gave us last Christmas.) is found that very first day. The final Horse Truth ("Don't lock the barn door after the horse has been stolen." Discovered after just that has happened.) isn't found until forty years later, New Year's Day 1106. In between, the girls work through their stable, subjecting horses to carriages above, below, before, and aft ("Don't put the cart before the horse."), driving them to drink ("fermented mash") through nervous exhaustion (the cure for which would be water, but "You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him drink."), powering treadmill equipped boats (sea horses, of course, although "Never change horses in the middle of the stream."), kicking (that leads to the discovery of a lost diamond stickpin; "Horseshoes are lucky."), and getting painted ("That is a horse of another color!").

As each Horse Truth is discovered, the contributor leaves the castle to wed her Peeping, all of whom also stayed true during all of those years.

OF THE FIRST PRINTING'S TEN THOUSAND COPIES, only about twenty-five hundred were sold. The Seven Lady Godivas became the first (and there was only one other) of Dr. Seuss's books to go out of print. Geisel later said, "I attempted to draw the sexiest babes I could, but they came out looking absurd." The lack of eroticism does not account for the books failure, however. The truth is that it's just not very good, a collection of bad puns that goes on too long. Geisel convinced Random House to reissue the book in 1987 "by multitudinous demand," which was "an outright lie, which I wrote myself," but the book was once again remaindered and fell back out of print.

OF THE FIRST PRINTING'S TEN THOUSAND COPIES, only about twenty-five hundred were sold. The Seven Lady Godivas became the first (and there was only one other) of Dr. Seuss's books to go out of print. Geisel later said, "I attempted to draw the sexiest babes I could, but they came out looking absurd." The lack of eroticism does not account for the books failure, however. The truth is that it's just not very good, a collection of bad puns that goes on too long. Geisel convinced Random House to reissue the book in 1987 "by multitudinous demand," which was "an outright lie, which I wrote myself," but the book was once again remaindered and fell back out of print.

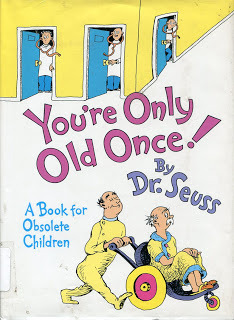

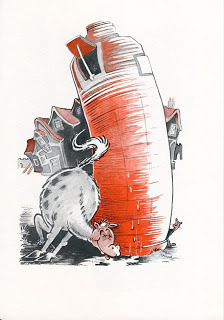

GEISEL DID EMPLOY the Dr. Seuss name on one last book for adults (or "obsolete children" as the cover says). You're Only Old Once! is a book that grew out of Geisel's declining health and many doctor visits towards the end of his life. Waiting in waiting rooms, Geisel began to sketch "what I thought was going to happen to me for the next hour and a half." The resultant book is a light verse take on the frustration with the modern medical system. It was released on Geisel's 82nd birthday, the last book written and drawn entirely by Dr. Seuss. It is still in print. CORRECTION 11/19/2011: Oh, the Place You Go! (1990) is the final book written and drawn by Dr. Seuss. You're Only Old Once! is the penultimate book. Thanks to Philip Nel for the correction.

ALL OF THE QUOTES and information in this post came from The Seuss, The Whole Seuss, and Nothing But the Seuss by Charles D. Cohen, Dr Seuss: American Icon by Philip Nel, and Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography by Judith and Neil Morgan.

[image error]

ONE REASON DR. SEUSS worked in so many fields was that he never felt that any of them were respectable enough. This went for children's books too. In the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine review of The King's Stilts, he told his college friend Alexander Laing that it was his "annual brat-book." With two such "brat-books" under his belt, Geisel wanted to expand his purview. So when Random House co-founder Bennett Cerf lured him away from Vanguard in 1939, it was under the condition that Geisel be allowed to do an "adult" book first. That book was The Seven Lady Godivas.

The Lady Godiva legend, of dubious origin, states that in 1037, the Earl of Coventry's wife rode naked on horseback through the streets of Coventry in protest against her husband's unfair taxes. In a later sanitized version of the story, the citizens of Coventry were ordered to remain in their shuttered houses during the ride, but one man looked out, Peeping Tom. He was then struck blind.

The Lady Godiva legend, of dubious origin, states that in 1037, the Earl of Coventry's wife rode naked on horseback through the streets of Coventry in protest against her husband's unfair taxes. In a later sanitized version of the story, the citizens of Coventry were ordered to remain in their shuttered houses during the ride, but one man looked out, Peeping Tom. He was then struck blind.Geisel had turned to Godiva as subject twice before in cartoons in the late 1920s (see left). And there had been other instances of nudity in his art, such as his take on the rape of the Sabine women, which hung in the Dartmouth Club for many years. That legend also had bearing on The Seven Lady Godivas as a parody by Stephen Vincent Benét entitled The Sobbin Women appeared in Argosy in 1938 with many of the same story elements that Geisel would use in his own book, namely seven women barricaded in a building refusing to marry their seven suitors. The similarity between the two stories along with the use of a sexually charged legend certainly suggests that Geisel was aware of the story of the previous year. (The Benét later served as the inspiration for the 1954 musical film Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. In another link between the stories, Geisel flew to New York in 1954 to discuss a musical based on The Seven Lady Godivas, which never came to fruition.) So how did one Lady Godiva become seven?

"HISTORY HAS TREATED NO NAME so shabbily as it has the name Godiva...There was not one; there were Seven Lady Godivas, and their nakedness actually was not a thing of shame. So far as Peeping Tom is concerned, he never really peeped. 'Peeping' was merely the old family name, and Tom and his six brothers bore it with pride."

These Lady Godivas are naturists who didn't waste time on "frivol and froth." On May 15, 1066 their father set out for the Battle of Hastings on horseback. ("True, Lord Godiva had been experimenting with these animals for years. But the horse remained a mystery...") Before he is out of the castle gate, Lord Godiva's horse throws him, and "the old warrior was dead" on impact. His seven daughters take a pledge that day:

These Lady Godivas are naturists who didn't waste time on "frivol and froth." On May 15, 1066 their father set out for the Battle of Hastings on horseback. ("True, Lord Godiva had been experimenting with these animals for years. But the horse remained a mystery...") Before he is out of the castle gate, Lord Godiva's horse throws him, and "the old warrior was dead" on impact. His seven daughters take a pledge that day:"'I swear,' swore each, ' that I shall not wed until I have brought to the light of the world some new and worthy Horse Truth, of benefit to man.'"

All seven sisters (Clemintina, Dorcas J., Arabella, Mitzi, Lulu, Gussie, and Hedwig) were engaged to the seven Peeping brothers (Tom, Dick, Harry, Jack, Drexel, Sylvester, and Frelinghuysen), so this was no idle oath. The sisters lock themselves in the castle, Hedwig, the eldest, makes a book with seven pages in which each sister is to inscribe her Horse Truth, and the scientific study begins.

The first Horse Truth ("Don't ever look a gift horse in the mouth!" Discovered after Teenie Godiva gets her nose bit off by the "mare Uncle Ethelbert gave us last Christmas.) is found that very first day. The final Horse Truth ("Don't lock the barn door after the horse has been stolen." Discovered after just that has happened.) isn't found until forty years later, New Year's Day 1106. In between, the girls work through their stable, subjecting horses to carriages above, below, before, and aft ("Don't put the cart before the horse."), driving them to drink ("fermented mash") through nervous exhaustion (the cure for which would be water, but "You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him drink."), powering treadmill equipped boats (sea horses, of course, although "Never change horses in the middle of the stream."), kicking (that leads to the discovery of a lost diamond stickpin; "Horseshoes are lucky."), and getting painted ("That is a horse of another color!").

The first Horse Truth ("Don't ever look a gift horse in the mouth!" Discovered after Teenie Godiva gets her nose bit off by the "mare Uncle Ethelbert gave us last Christmas.) is found that very first day. The final Horse Truth ("Don't lock the barn door after the horse has been stolen." Discovered after just that has happened.) isn't found until forty years later, New Year's Day 1106. In between, the girls work through their stable, subjecting horses to carriages above, below, before, and aft ("Don't put the cart before the horse."), driving them to drink ("fermented mash") through nervous exhaustion (the cure for which would be water, but "You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him drink."), powering treadmill equipped boats (sea horses, of course, although "Never change horses in the middle of the stream."), kicking (that leads to the discovery of a lost diamond stickpin; "Horseshoes are lucky."), and getting painted ("That is a horse of another color!").As each Horse Truth is discovered, the contributor leaves the castle to wed her Peeping, all of whom also stayed true during all of those years.

OF THE FIRST PRINTING'S TEN THOUSAND COPIES, only about twenty-five hundred were sold. The Seven Lady Godivas became the first (and there was only one other) of Dr. Seuss's books to go out of print. Geisel later said, "I attempted to draw the sexiest babes I could, but they came out looking absurd." The lack of eroticism does not account for the books failure, however. The truth is that it's just not very good, a collection of bad puns that goes on too long. Geisel convinced Random House to reissue the book in 1987 "by multitudinous demand," which was "an outright lie, which I wrote myself," but the book was once again remaindered and fell back out of print.

OF THE FIRST PRINTING'S TEN THOUSAND COPIES, only about twenty-five hundred were sold. The Seven Lady Godivas became the first (and there was only one other) of Dr. Seuss's books to go out of print. Geisel later said, "I attempted to draw the sexiest babes I could, but they came out looking absurd." The lack of eroticism does not account for the books failure, however. The truth is that it's just not very good, a collection of bad puns that goes on too long. Geisel convinced Random House to reissue the book in 1987 "by multitudinous demand," which was "an outright lie, which I wrote myself," but the book was once again remaindered and fell back out of print.GEISEL DID EMPLOY the Dr. Seuss name on one last book for adults (or "obsolete children" as the cover says). You're Only Old Once! is a book that grew out of Geisel's declining health and many doctor visits towards the end of his life. Waiting in waiting rooms, Geisel began to sketch "what I thought was going to happen to me for the next hour and a half." The resultant book is a light verse take on the frustration with the modern medical system. It was released on Geisel's 82nd birthday, the last book written and drawn entirely by Dr. Seuss. It is still in print. CORRECTION 11/19/2011: Oh, the Place You Go! (1990) is the final book written and drawn by Dr. Seuss. You're Only Old Once! is the penultimate book. Thanks to Philip Nel for the correction.

ALL OF THE QUOTES and information in this post came from The Seuss, The Whole Seuss, and Nothing But the Seuss by Charles D. Cohen, Dr Seuss: American Icon by Philip Nel, and Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography by Judith and Neil Morgan.

Good Night, Wendy is an occasional series on adult works by children author's. For previous entries, see here.All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on November 17, 2011 08:33

October 31, 2011

PICTURES ADDED TO "DAD'S THE ONE WITH THE PIPE"

I KNOW the lag time between my posts grows ever longer. (The Cummings did take me two weeks to research and write, so it's not just my laziness.) In the meantime, let me direct your attention to a few new images added to my even less frequently updated Flickr set

Dad's The One With The Pipe

. For those of you who have never visited, the set's description:

I KNOW the lag time between my posts grows ever longer. (The Cummings did take me two weeks to research and write, so it's not just my laziness.) In the meantime, let me direct your attention to a few new images added to my even less frequently updated Flickr set

Dad's The One With The Pipe

. For those of you who have never visited, the set's description:"In the halcyon days of mid-20th century children's books, there were visual clues in the pictures to guide the nascent reader. If ever it was in doubt, a little boy or girl could look and know DAD'S THE ONE WITH THE PIPE."

This time around there are five almost identical images by Crockett Johnson of Harold and the Purple Crayon fame (see left) and one from the Little Golden Books master Tibor Gergely.

An interesting commentary on one of my favorite pipe-toting dad books, the Little Golden Book We Help Daddy, is the publisher's own censoring over the years. In the first edition, released in 1962, Dad brazenly smokes a pipe on the cover (and every other time we see him). In 1979 (the edition I have and scanned), Golden removed the pipe from the cover, but left it inside. In 1989, the pipe was gone completely. I'm uncomfortable with these kind of silent changes, but it does say a lot about our attitudes towards smoking. (I, for the record, am of course against smoking near children, or anywhere else for that matter.)

Dad's The One With The Pipe is a Flickr group, so I encourage everyone to join and to add images. I know there are lots more pops with pipes, and I count on you all to share them. I will try to get a real We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie post up sometime in November. Thanks to everyone for sticking with me.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on October 31, 2011 18:15

Ariel S. Winter's Blog

- Ariel S. Winter's profile

- 67 followers

Ariel S. Winter isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.