Ariel S. Winter's Blog, page 2

June 2, 2014

RANDALL JARRELL: THE GOLDEN BIRD AND OTHER TALES OF THE BROTHERS GRIMM

IN THE WINTER OF 1962, Randall Jarrell, the former United States Poet Laureate and recipient of the 1961 National Book Award for Poetry, was bedridden with hepatitis. Too tired to read his own mail, his wife Mary sat by his bedside opening and reading aloud the get-well cards and other correspondences that arrived each day. One of those letters was a note on Macmillan letterhead from a young children's book editor the Jarrells had never heard of named Michael di Capua. di Capua was planning a series of over-sized picture book collections of fairy tales with new introductions by literary stars such as John Updike, Isak Dinesen, and Elizabeth Bowen. Having noted Jarrell's repeated references to the Brothers Grimm in his poetry, di Capua wanted Jarrell to contribute a selection of tales from the Brothers' folktales. Energized by the prospect in a way he hadn't been for weeks, Jarrell sat up and asked Mary to bring him a copy of the complete tales in German. He chose five stories--Snow-White and the Seven Dwarfs, Hansel and Gretel, The Golden Bird, Snow-White and Rose-Red, and The Fisherman and His Wife--and began translating while still in bed.

IN THE WINTER OF 1962, Randall Jarrell, the former United States Poet Laureate and recipient of the 1961 National Book Award for Poetry, was bedridden with hepatitis. Too tired to read his own mail, his wife Mary sat by his bedside opening and reading aloud the get-well cards and other correspondences that arrived each day. One of those letters was a note on Macmillan letterhead from a young children's book editor the Jarrells had never heard of named Michael di Capua. di Capua was planning a series of over-sized picture book collections of fairy tales with new introductions by literary stars such as John Updike, Isak Dinesen, and Elizabeth Bowen. Having noted Jarrell's repeated references to the Brothers Grimm in his poetry, di Capua wanted Jarrell to contribute a selection of tales from the Brothers' folktales. Energized by the prospect in a way he hadn't been for weeks, Jarrell sat up and asked Mary to bring him a copy of the complete tales in German. He chose five stories--Snow-White and the Seven Dwarfs, Hansel and Gretel, The Golden Bird, Snow-White and Rose-Red, and The Fisherman and His Wife--and began translating while still in bed.It is no surprise that di Capua thought of Jarrell for the Grimm entry to his series. Jarrell's poems include "The Märchen," the German word for folktales, which is subtitled "(Grimm's Tales)," "Cinderella," "The Sleeping Beauty: Variation of the Prince," and dozens of others that refer to the folk stories. Jarrell uses the tales to explore the ways in which childhood forges identity, but even more so, to understand how a person can live in the modern world of machines and atomic weapons, and still find a home and family. As he says in his introduction to the The Golden Bird and Other Tales:

The rest of Jarrell's introduction is devoted to a poem by the German poet Eduard Mörike, in which Mörike reads Snow-White and the Seven Dwarfs to a child, and comes to the realization that he has a fairytale wish: to have his own wife and children. Jarrell never had children of his own, but helped raise Mary's two daughters from a previous marriage, so it is easy to imagine how Mörike's wish resonated with Jarrell."As you read the stories they remind you of what the world used to be like before people had machines and advertisements and wonder drugs and Social Security. But they remind you, too, that in some ways the world hasn't changed; that our wishes and dreams are the same as ever. Reading Grimm's Tales tells someone what we're like, inside, just as reading Freud tells him. The Fisherman and His Wife--which is one of the best stories anyone ever told, it seems to me--is as truthful and troubling as any newspaper headlines about the new larger-sized H-bomb and the new anti-missile missile: a country is never satisfied either, but wants to be like the good Lord."

IT WASN'T JUST THE SUBJECT MATTER, however, that attracted Jarrell to the Grimm project. He was also a greater lover of the German language. His wife Mary once said, "I came into Randall's life after Salzburg and Rilke, about the middle of Mahler; and I got to stay through Goethe and up to Wagner." Mary clearly felt that Jarrell's life could be defined by his German influences. As Jarrell himself wrote, "Till the day I die I'll be in love with German." But some of that passion relied on the mysteries of the language for him. He never spoke German, and understood it only well enough to labor through his translations with the assistance of a German/English dictionary. "My translations of the stories," he wrote in his introduction, "are as much like the real German stories as I could make them." Comparing them side-by-side with other translations of the tales, it seems that Jarrell was very faithful.

IT WASN'T JUST THE SUBJECT MATTER, however, that attracted Jarrell to the Grimm project. He was also a greater lover of the German language. His wife Mary once said, "I came into Randall's life after Salzburg and Rilke, about the middle of Mahler; and I got to stay through Goethe and up to Wagner." Mary clearly felt that Jarrell's life could be defined by his German influences. As Jarrell himself wrote, "Till the day I die I'll be in love with German." But some of that passion relied on the mysteries of the language for him. He never spoke German, and understood it only well enough to labor through his translations with the assistance of a German/English dictionary. "My translations of the stories," he wrote in his introduction, "are as much like the real German stories as I could make them." Comparing them side-by-side with other translations of the tales, it seems that Jarrell was very faithful. But when a reader chooses a version of the fairy tales to read, the illustrations are sometimes more important than the translations, and Jarrell was fortunate to have such an incredible illustrator in Sandro Nardini. While his paintings might be overly idyllic at times, the lush colors, and evocative Medieval setting of the stories make Jarrell's book beautiful to look at as well as to read. To see more of the illustrations from the book, head over to my Flickr account. And look for samples of other illustrators who have chosen Jarrell's text for their own versions of the fairy tales in an upcoming post.

FOR THIS POST, I consulted The Children's Books of Randall Jarrell by Jerome Griswold with an introduction by Mary Jarrell, Randall Jarrell's Letters editd by Mary Jarrell, Randall Jarrell: A Literary Life by William H. Pritchard, and "Jarrell and the Germans" by Richard K. Cross.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on June 02, 2014 18:19

January 8, 2014

PEARL S. BUCK: THE CHRISTMAS MOUSE

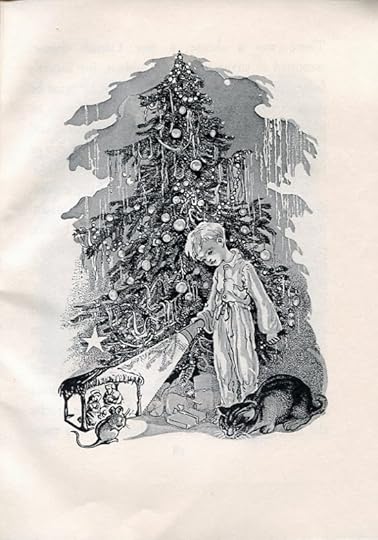

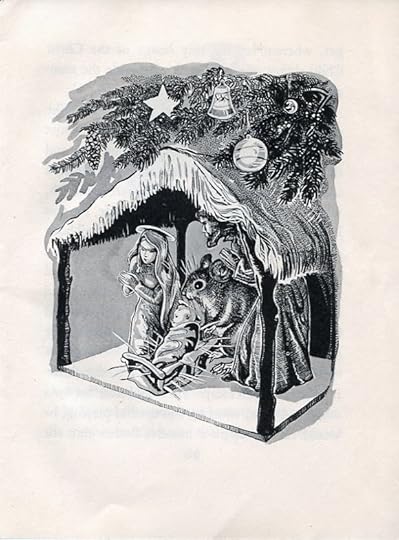

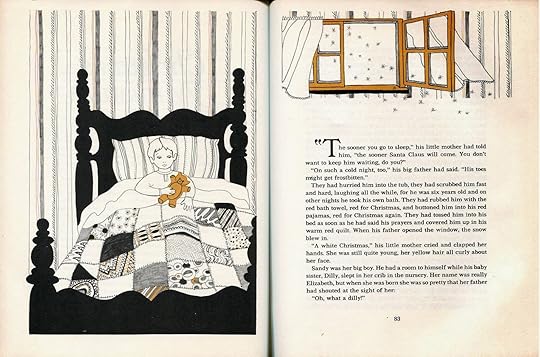

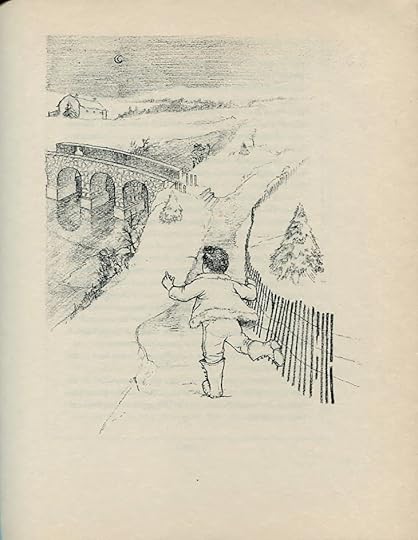

TALK ABOUT GETTING a lot of mileage out of one story. We have already looked at Christmas Miniature by Pearl S. Buck as it appeared in Family Circle Magazine and Once Upon a Christmas, and then as it appeared as a stand-alone book and in A Gift for Children. Well in Great Britain in 1958, Christmas Miniature was published again under the title The Christmas Mouse with new illustrations by Astrid Walford. From the back of the book: "The delicate and perceptive line and wash drawings by Astrid Walford are among the loveliest work she has ever done."

TALK ABOUT GETTING a lot of mileage out of one story. We have already looked at Christmas Miniature by Pearl S. Buck as it appeared in Family Circle Magazine and Once Upon a Christmas, and then as it appeared as a stand-alone book and in A Gift for Children. Well in Great Britain in 1958, Christmas Miniature was published again under the title The Christmas Mouse with new illustrations by Astrid Walford. From the back of the book: "The delicate and perceptive line and wash drawings by Astrid Walford are among the loveliest work she has ever done."There are a few minor differences between the U.S. and U.K. editions. For some reason the bicycle becomes a tricycle. The flashlight on the back of the book is translated as a torch, but within the book remains a flashlight. And the British spellings of words like pajamas have been predictably adopted.

Below are a sample of Walford's illustrations. To see them all visit my Flickr set.

COMING SOON: More Pearl S. Buck

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on January 08, 2014 17:02

January 7, 2014

PEARL S. BUCK: CHRISTMAS FOLLOW-UP

SHORTLY BEFORE CHRISTMAS, I wrote about several of Pearl S. Buck's Christmas stories for children. At the time, I was still waiting to get my hands on some other editions of the stories, and promised I would post scans as soon as I did. Well the books came in...

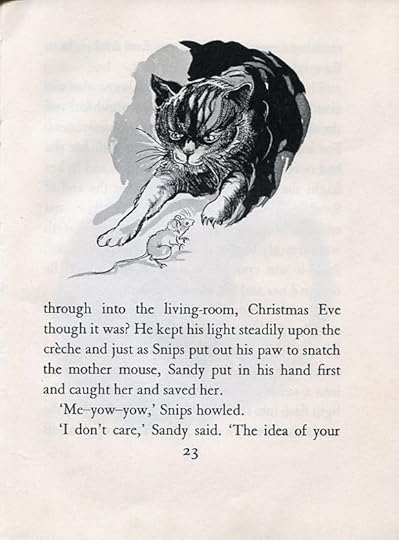

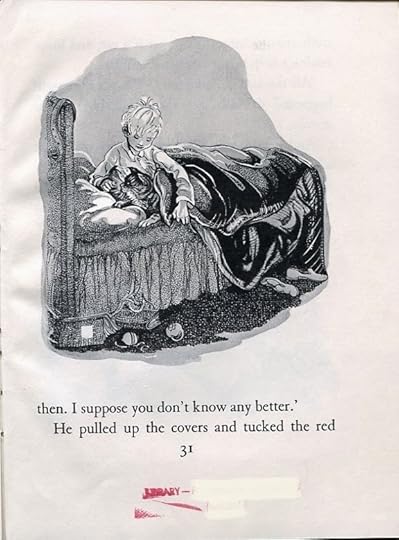

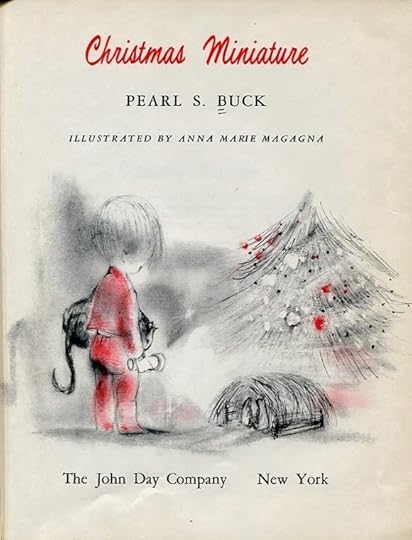

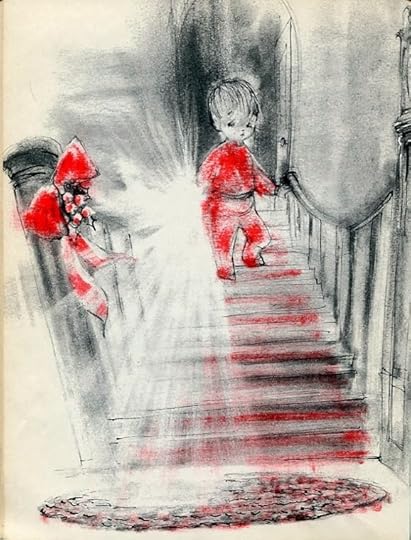

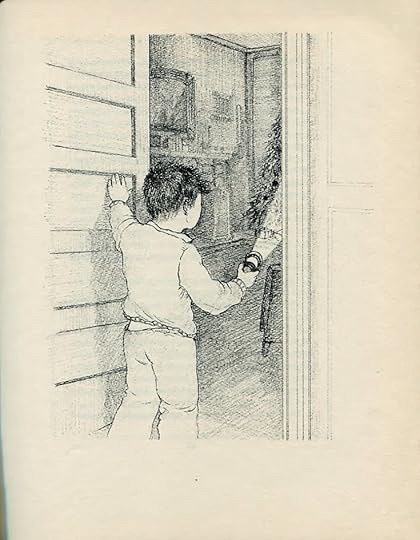

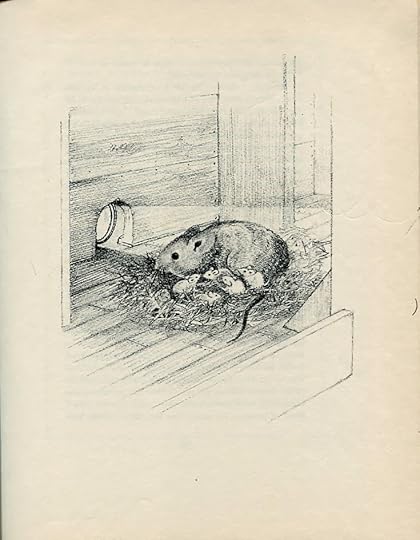

SHORTLY BEFORE CHRISTMAS, I wrote about several of Pearl S. Buck's Christmas stories for children. At the time, I was still waiting to get my hands on some other editions of the stories, and promised I would post scans as soon as I did. Well the books came in...Christmas Miniature and The Christmas Ghost were both published as books by The John Day Company with illustrations by Anna Marie Magagna almost immediately after the stories appeared in Family Circle Magazine. Magagna was at the start of an illustration career that would go on to include editions of The Wizard of Oz, Little Men and Little Women, Five Little Peppers and many others. Her drawings for Christmas Miniature were shown at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. in 1958.

In addition to her accomplishments in the world of publishing, Magagna is possibly best known as the exclusive fashion illustrator for the high-end women's store Henri Bendel starting in 1969 throughout the early 1970s. A selection of her fashion drawings was exhibited in a one woman show last year.

From Christmas Miniature:

From The Christmas Ghost:

Just after her death in 1973, The John Day Company put out a collection of Pearl S. Buck's children's stories called A Gift for the Children. Despite Once Upon a Christmas having appeared only the year before (see my previous post for scans from that book), both Christmas Miniature and The Christmas Ghost were included each with yet another set of illustrations, this time by Elaine Scull.

Christmas Miniature:

The Christmas Ghost:

Not all of Buck's Christmas stories were illustrated so many times, but all of them had multiple lives. I now have several other Christmas books in hand as well as these, so even though Christmas is behind us, bear with me as I stretch the holiday into January in my upcoming posts. To see even more of Anna Marie Magagna's illustrations for these books, view my Flickr sets for Christmas Miniature and The Christmas Ghost .

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on January 07, 2014 18:41

December 23, 2013

PEARL S. BUCK: CHRISTMAS

PEARL S. BUCK WON THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE in 1938 "for her rich and truly epic descriptions of peasant life in China and for her biographical masterpieces." Her bestselling, Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Good Earth, detailing peasant life in China, remains a perennial classic. Born to American Southern Presbyterian missionaries, Buck moved to China at the age of three months and lived there until she returned to the United States for college. Despite growing up in a country that did not celebrate Christmas, Buck's family and the families of other American missionaries, along with the English who lived in the British Concession, made Christmas with all the joyous trimmings of home: trees and holly, stockings and presents, parties and feasts. "From such memories of my Chinese childhood," Buck wrote, "it is no wonder that when I had an American home of my own, complete with husband and children, every Christmas was as joyous as we could make it."

For Buck, a large part of that celebration was telling stories, many of which she recorded and published in magazines and as books. "I told my children many stories when they were small enough for bedtime stories, and each year they chose one to make into a book. The Christmas stories, of course, were always special." They included stories such as "A Certain Star," "The Christmas Ghost," "The Christmas Mouse," "Christmas Day in the Morning," and many others, which appeared in special Christmas issues of magazines like Good Housekeeping, Family Circle, Ladies' Home Journal, and Collier's before being reissued as books.

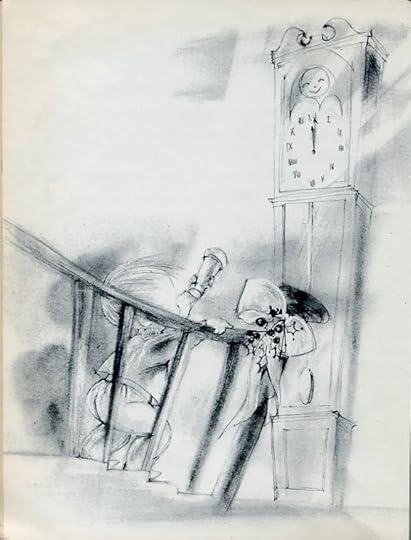

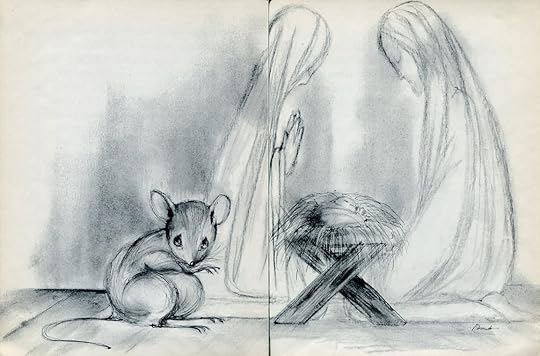

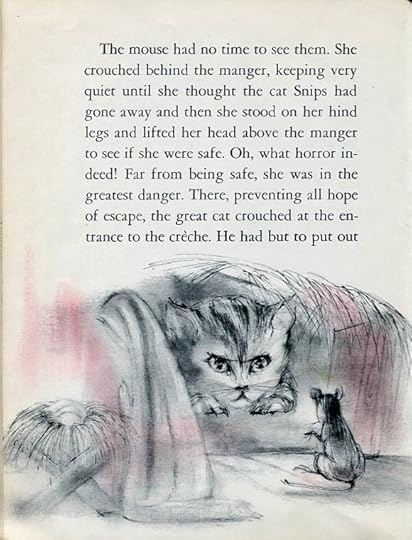

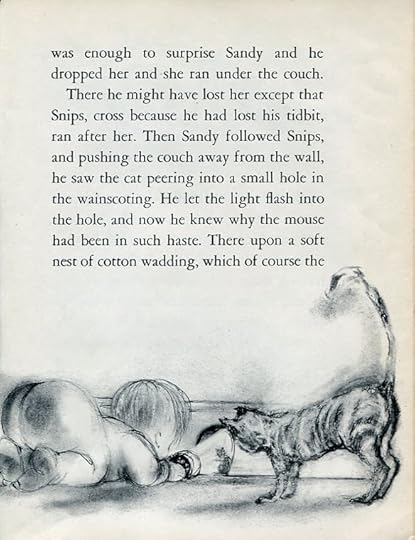

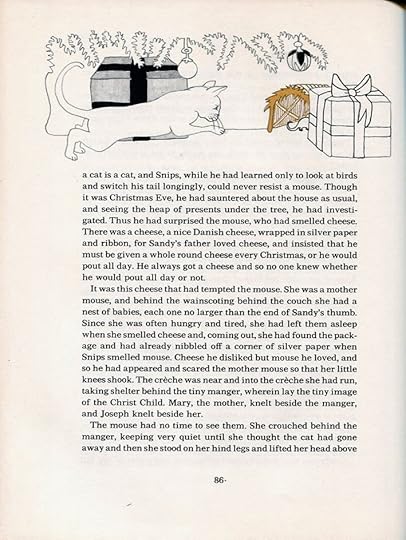

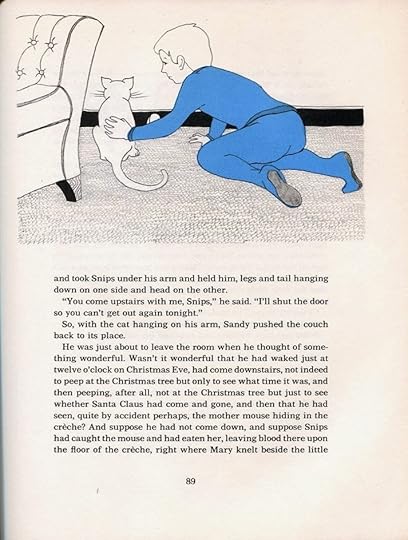

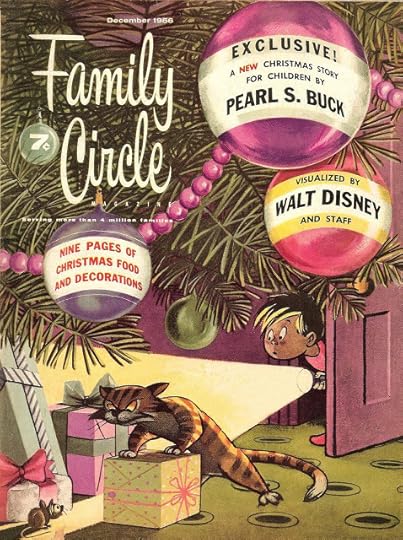

For Buck, a large part of that celebration was telling stories, many of which she recorded and published in magazines and as books. "I told my children many stories when they were small enough for bedtime stories, and each year they chose one to make into a book. The Christmas stories, of course, were always special." They included stories such as "A Certain Star," "The Christmas Ghost," "The Christmas Mouse," "Christmas Day in the Morning," and many others, which appeared in special Christmas issues of magazines like Good Housekeeping, Family Circle, Ladies' Home Journal, and Collier's before being reissued as books.In "Christmas Miniature," a 1956 special insert in Family Circle with art by the Walt Disney Studio, six-year-old Sandy makes the midnight trip downstairs "not indeed to peep at the Christmas tree but only to see what time it was." In so doing, he finds his cat Snips about to eat a mother mouse hiding behind the miniature manger under the tree. He grabs the mouse first, who bites him to escape his grasp, and dashes under the couch to return to her babies. The story was published as a book the next year with illustrations by Anna Marie Magagna, and included in Buck's Once Upon a Christmas with illustrations by Donald Lizzul (seen below).

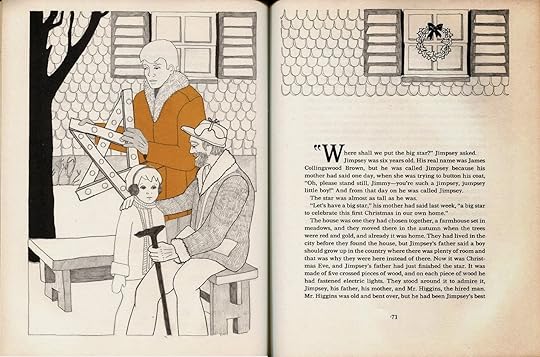

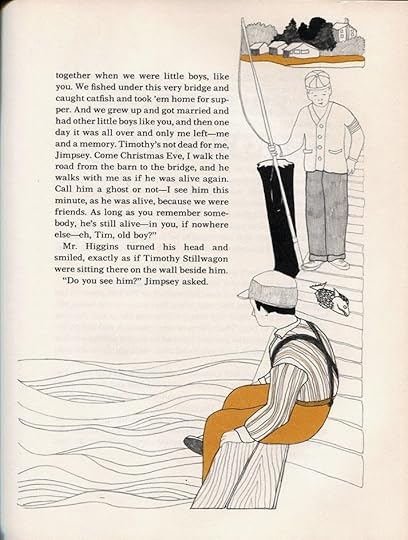

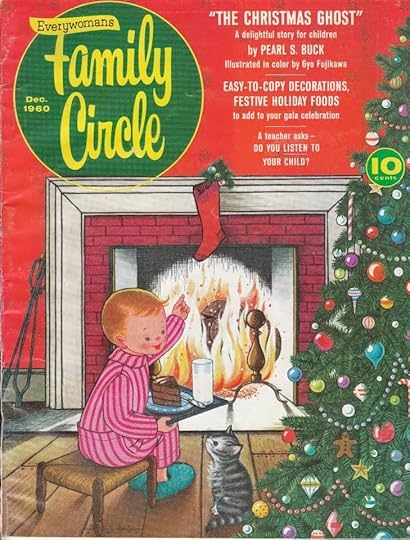

"The Christmas Ghost," which first appeared in a 1960 issue of Family Circle with illustrations by Gyo Fujikawa, tells the story of Jimpsey, a young boy whose family is celebrating their first Christmas in their new farm house after leaving the city. Mr. Higgins, the hired hand, tells Jimpsey that the ghost of the former owner Timothy Stillwagon walks from the barn to the bridge over the brook every Christmas Eve. When Jimpsey goes out in the middle of the night to see, he only finds Mr. Higgins there, who explains that it is the memory of Timothy Stillwagon that walks with him those nights, and that is what he meant by ghost.

Buck's own gardener "always insisted that the ghost of Old Devil Harry did walk every Christmas Eve at midnight from the big red barn to the bridge, to meet the ghost of a former crony with whom he used to get drunk each Christmas Even." In the story, Mr. Higgins and Timothy Stillwagon meet to admire each other's Christmas trees. Like "Christmas Miniature," "The Christmas Ghost" appeared as a book almost immediately with illustrations by Anna Marie Magagna. The story was included in Once Upon a Christmas as well.

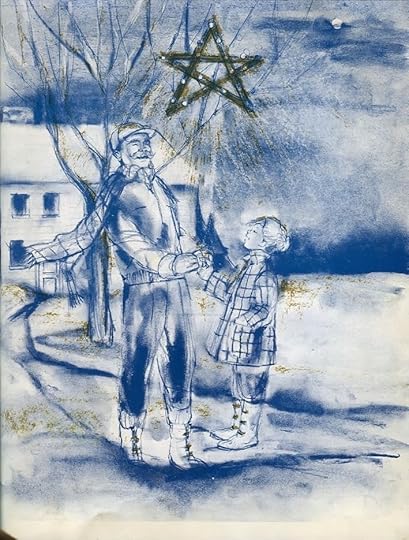

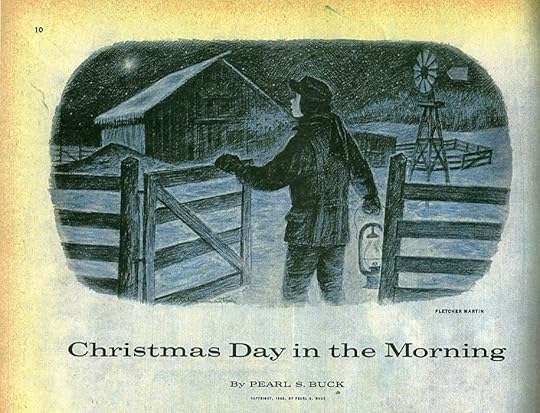

A story that Buck for some reason did not include in Once Upon a Christmas is "Christmas Day in the Morning," a story that first appeared in Collier's in 1955 (see art at top). "Christmas Day in the Morning" tells of how Rob, the eldest son of a farmer, realizes that the best gift he can give his father for Christmas is to wake up extra early and do the milking before his father has even gotten out of bed. This act grew out of the realization that his father truly loved him when he overheard his father saying to his mother how much he hates to wake Rob in the mornings. When his father finds the milking done, they hug in the darkness, unable to see each other's faces, but communicating their mutual love better than they have ever done before.

A story that Buck for some reason did not include in Once Upon a Christmas is "Christmas Day in the Morning," a story that first appeared in Collier's in 1955 (see art at top). "Christmas Day in the Morning" tells of how Rob, the eldest son of a farmer, realizes that the best gift he can give his father for Christmas is to wake up extra early and do the milking before his father has even gotten out of bed. This act grew out of the realization that his father truly loved him when he overheard his father saying to his mother how much he hates to wake Rob in the mornings. When his father finds the milking done, they hug in the darkness, unable to see each other's faces, but communicating their mutual love better than they have ever done before."Christmas Day in the Morning" was not strictly a children's story when it was published in Collier's, but it was made into a picture book posthumously in 2002 with some light editing, which removed the adult Rob's memories of his dead wife as well as his dead father. Illustrator Mark Buehner was inspired to illustrate the story after his own children woke up in the middle of the night one Christmas Eve to clean the entire downstairs floor of his house after hearing Buck's story at church, a testament to how touching Buck's work remains decades after her death.

THESE THREE STORIES are really just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Pearl S. Buck's Christmas stories for children. That's an understatement when it comes to Pearl S. Buck's children's books on whole, one reason that I have waited so long to tackle her on the blog. I had hoped to have more editions of these stories and some others before Christmas this year, but I waited a bit too long to secure them in time, so there will be some follow up posts possibly into the new year. As a result, I made a very rare exception to one of my rules, which is to have borrowed some scans, from I'm Learning to Share! for the "Christmas Miniature" Family Circle cover, and from The Estate Sale Chronicles for the "Christmas Ghost" cover. In both cases, the original blogs have the entire stories scanned and available to read, so please do click through. The rest of the scans are my own.

If you are looking for more Christmas fun, check out previous year's posts:

J.R.R. Tolkien's "Father Christmas Letters"

Eleanor Roosevelt's Christmas

Warren Chappell's The Nutcracker

Ilonka Karasz's The Twelve Days of Christmas

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on December 23, 2013 18:15

October 21, 2013

WENDY WASSERSTEIN IN THANKS & GIVING

PAMELA'S FIRST MUSICAL

was Wendy Wasserstein's only children's book, but it wasn't the only thing she published with children as the intended audience. She contributed to Marlo Thomas's 2004 book Thanks & Giving All Year Long.

PAMELA'S FIRST MUSICAL

was Wendy Wasserstein's only children's book, but it wasn't the only thing she published with children as the intended audience. She contributed to Marlo Thomas's 2004 book Thanks & Giving All Year Long.Thomas is most famous as the creator of the 1972 classic book and album Free to Be...You and Me, an anthology of songs and stories by celebrities meant to teach that it is okay to break normal gender stereotypes. Thomas has since used the format in several other books, the most recent of which is Thanks & Giving. The title really says it all with regards to this book's message, although some of the entries seem a stretch. (Matt Groening's Life in Hell bunny finds a dollar on the sidewalk and buys a banana split?)

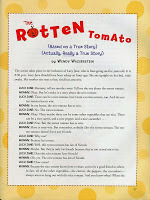

Wasserstein shares a bedtime conversation she had with her daughter Lucy Jane, who was four at the time. In "The Rotten Tomato," Lucy Jane asks for a bedtime story about a rotten tomato. Wasserstein wants to tell a story about a good tomato. Lucy Jane is willing to allow a good tomato to be in the story, but the rotten tomato has to win. They go back and forth with Wasserstein spelling out why being a "good" tomato is better than being a "rotten" one. As you would expect from Wasserstein, the scene is quite funny. (Click on the scans below to read.) Lucy Jane illustrated the story.

Wasserstein did have work included in one other anthology intended for young people, 33 Things Every Girl Should Know, but the essay comes from one of her collection Bachelor Girls, and was not conceived of as a children's story.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on October 21, 2013 09:18

October 17, 2013

WENDY WASSERSTEIN: PAMELA'S FIRST MUSICAL

WENDY WASSERSTEIN IS BEST KNOWN as a playwright. Her 1988 play The Heidi Chronicles won the Pulitzer Prize, the Tony Award, the Drama Desk Award, and the New York Drama Critics Circle. The Tony was the first ever awarded to a female playwright. Her subsequent play The Sisters Rosensweig was then nominated or won almost all of the same prizes. Over her career, she had at least ten plays appear on and off Broadway.

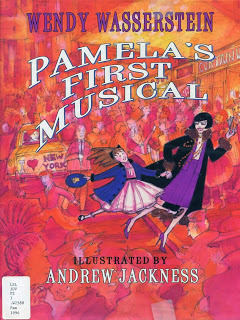

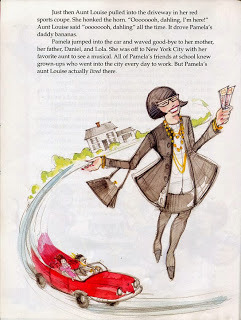

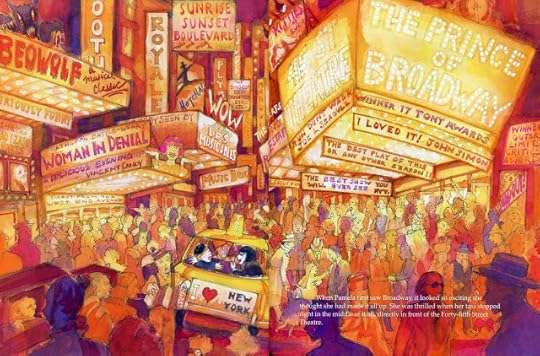

WENDY WASSERSTEIN IS BEST KNOWN as a playwright. Her 1988 play The Heidi Chronicles won the Pulitzer Prize, the Tony Award, the Drama Desk Award, and the New York Drama Critics Circle. The Tony was the first ever awarded to a female playwright. Her subsequent play The Sisters Rosensweig was then nominated or won almost all of the same prizes. Over her career, she had at least ten plays appear on and off Broadway.But despite theater being her home, Wasserstein also wrote in almost every other form available. She wrote a movie, a novel, essays, memoirs, books of non-fiction, teleplays, and, of course, a children's book. Pamela's First Musical is, no surprise, about theater. Illustrated by Andrew Jackness, the set designer for Wasserstein's play Isn't It Romantic?, Wasserstein wrote Pamela in the hope that "[my] book would inspire children to fall in love with musicals in the same way [I] had." Dedicated to her niece Pamela (who was in high school at the time the book was published), it tells the story of Pamela's whirlwind ninth birthday, when her Aunt Louise takes her into New York to see her first musical.

AUNT LOUISE MIGHT just as well be called Auntie Mame. She is a clothing designer who goes around saying "Ooooooo, dahling." "(You can tell whether Aunt Louise designed your blue jeans because they are all signed Oooooooh, Dahling on the back pocket.)" While "all of Pamela's friends at school knew grown-ups who went into the city every day to work...Pamela's aunt Louise actually lived there." She also seems to know everybody who is anybody.

AUNT LOUISE MIGHT just as well be called Auntie Mame. She is a clothing designer who goes around saying "Ooooooo, dahling." "(You can tell whether Aunt Louise designed your blue jeans because they are all signed Oooooooh, Dahling on the back pocket.)" While "all of Pamela's friends at school knew grown-ups who went into the city every day to work...Pamela's aunt Louise actually lived there." She also seems to know everybody who is anybody.After a stop back at her apartment to change "out of her driving clothes into her theater clothes," Aunt Louise drags Pamela to the Russian Tea Room. "'The Tea Room is simply the place to have lunch before your first musical.'"

There they run into the world-famous dancer Bearish Nureyjinsky, who is the first in a list of theatrical celebrities with oddly familiar names that Pamela meets. At the theater, there are the stars Nathan Hines Klines and Mary Ethel Bernadette, the producer Mr. Bernie S. Gerry, choreographer Miss La Tuna, composer Mr. Finnsical, book writers Betty and Cy Songheim (with dogs Roger and Heart), set designer Candita Ivey Zippers, and Jules Gels, the light designer. (Pamela also gets the usher Gladys's autograph on her Playbill.)

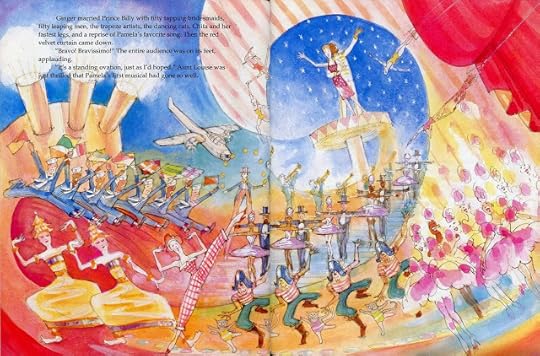

Of course, Pamela is entranced with the play. It tells the generic love story, of Billy and Ginger falling in love just before World War II, divided by the war, but reuniting in the South Pacific where Ginger's friend rescues Billy from pirates. Okay, so maybe that last part isn't so generic. The whole thing ends with "a reprise of Pamela's favorite song," and a standing ovation.

After meeting the stars, "the old stage door man waved to Pamela to come stand onstage in the empty house. 'This is the ghost light,' he explained. 'This means the theater always stays lit for all the people who ever performed here. It also means you can come back anytime.'"

That night Pamela recreates the play at home with her dolls before falling asleep and dreaming of "producing, writing, choreographing, designing, and directing hundreds of dancing girls, parades of tapping men...and a cast of thousands, maybe millions."

LIKE AUNT LOUISE, Wendy Wasserstein knew everybody. The back cover of Pamela's First Musical is blurbed by Meryl Streep, Angela Lansbury, Kevin Kline, Glen Close, Cy Coleman, Chita Rivera, Carol Channing, Sarah Jessica Parker, Matthew Broderick, Gregory Hines, Bernadette Peters and others. But despite knowing theater, and knowing everybody, Wasserstein found she didn't know children's books. In an essay for The New York Times about the book tour for Pamela's First Musical, she wrote, "When I look back on my first foray into children's literature, it seems an act of complete naivete and hubris at once." First, she is surprised how similar the children's book business is to theater "in all its ambition, difficulty and quirkiness":

LIKE AUNT LOUISE, Wendy Wasserstein knew everybody. The back cover of Pamela's First Musical is blurbed by Meryl Streep, Angela Lansbury, Kevin Kline, Glen Close, Cy Coleman, Chita Rivera, Carol Channing, Sarah Jessica Parker, Matthew Broderick, Gregory Hines, Bernadette Peters and others. But despite knowing theater, and knowing everybody, Wasserstein found she didn't know children's books. In an essay for The New York Times about the book tour for Pamela's First Musical, she wrote, "When I look back on my first foray into children's literature, it seems an act of complete naivete and hubris at once." First, she is surprised how similar the children's book business is to theater "in all its ambition, difficulty and quirkiness":"The boffo book chains of the Barnes & Noble and Borders variety appear to be the Broadway of children's books departments, complete with sets, lights and sizable audiences. There are even over-the-title stars like "Eloise," "Madeline," "Clifford"; and of course the proven box-office talents of Maurice Sendak, Faith Ringgold and Lane Smith."As she continues to tour she learns that "touring with a children's book required acting, teaching and stand-up skills beyond my playwright's training." It didn't help that, out of town, when she asked audiences of children if they had seen any musicals, only about a quarter of them had if she was lucky. It wasn't until she was back in New York, where "even the boys like musicals [and] the stars of "Pamela's First Musical," Nathan Hines Klines and Mary Ethel Bernadette, are immediately recognizable," that she felt comfortable with the crowd.

WITH MODERN PICTURE BOOKS like Pinkalicious and Fancy Nancy getting adapted into musicals, it is only natural that a picture book about musicals got the musical treatment. Sometime around the book's 1996 release, lyricist David Zippel (who wrote the lyrics for Disney's Hercules and Mulan) “called [Wasserstein] up and said, ‘let’s do a television movie of it.'" Wasserstein liked the idea, and they enlisted Cy Coleman, the three-time Tony winning composer of Sweet Charity, City of Angels and The Will Rogers Follies, who had blurbed the picture book. In 1998, Playbill announced that the piece would be an ABC Sunday night movie.

WITH MODERN PICTURE BOOKS like Pinkalicious and Fancy Nancy getting adapted into musicals, it is only natural that a picture book about musicals got the musical treatment. Sometime around the book's 1996 release, lyricist David Zippel (who wrote the lyrics for Disney's Hercules and Mulan) “called [Wasserstein] up and said, ‘let’s do a television movie of it.'" Wasserstein liked the idea, and they enlisted Cy Coleman, the three-time Tony winning composer of Sweet Charity, City of Angels and The Will Rogers Follies, who had blurbed the picture book. In 1998, Playbill announced that the piece would be an ABC Sunday night movie.In 2002, the first public offering of material related to the work was released when Cy Coleman included the main theme from Pamela's First Musical "It Started With a Dream" on his album of the same name. By that time, the musical had transformed into a stage show, a work-in-progress version of which was shown to industry people through Lincoln Center Theater in 2003. Pamela's age was changed, new subplots about prospective stepmothers and stepsisters were added, but at base it was still about going to see a musical with Aunt Louise. In October 2004 it was announced that Goodspeed Musicals would stage a version in 2005, but Cy Coleman died in November 2004, and the Goodspeed performance was cancelled. The team picked themselves up, and prepared for another performance at California Theaterworks in 2005, but Wasserstein's battle with lymphoma forced that production to be cancelled as well. Wasserstein died in early 2006 at the age of fifty-five.

David Zippel was not going to let that be the end of Wasserstein's last play. Pamela's First Musical was virtually complete when Coleman died. All it needed was a venue. At last, on May 18, 2008, Broadway Cares staged a concert of Pamela's First Musical at Town Hall. Kathy Lee Gifford, Joel Grey, Tommy Tune and many others made cameos. Proceeds benefited Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS and Wendy Wasserstein's own charity, Theater Development Fund's Open Doors Program. You can see a performance from that afternoon here.

David Zippel was not going to let that be the end of Wasserstein's last play. Pamela's First Musical was virtually complete when Coleman died. All it needed was a venue. At last, on May 18, 2008, Broadway Cares staged a concert of Pamela's First Musical at Town Hall. Kathy Lee Gifford, Joel Grey, Tommy Tune and many others made cameos. Proceeds benefited Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS and Wendy Wasserstein's own charity, Theater Development Fund's Open Doors Program. You can see a performance from that afternoon here.The real Pamela Wasserstein was in attendance. She told Broadway Cares, “Really it’s Wendy, Cy and David’s tribute to Broadway...I know Wendy and Cy would be so happy. In fact, I just know they’re here!”

I CONSULTED Julie Salamon's biography Wendy and the Lost Boys: The Uncommon Life of Wendy Wasserstein, Wasserstein's essay "Way Off Broadway With Pamela" from the June 30, 1996 edition of The New York Times, and Playbill's website. Much of the information regarding the musical Pamela's First Musical, as well as the photos from the Town Hall performance come from Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS own website. The photo of Wendy Wasserstein is from Wikipedia.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on October 17, 2013 18:01

October 8, 2013

THE WORLD IS ROUND BACK IN PRINT

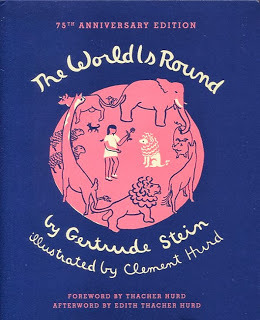

LONG TIME READERS might remember a series I did almost two and a half years ago on Gertrude Stein's children's book The World Is Round. There have been many editions over the years, in many different formats, with different illustrations, all of which I examined then, all of which were out of print. But now thanks to Harper Design, The World is Round is back in print in a 75th Anniversary Edition that features the original illustrations, complete with pink paper and blue text, on nice, heavy paper stock. Illustrator Clement Hurd's son Thatcher Hurd, who is also a children's book writer and illustrator, provides a new foreword detailing the publication history of the book along with reminiscences of his father at work. But more importantly, Edith Thatcher Hurd's afterword, which originally appeared in a limited collector's edition in 1986 is included, containing correspondence between Hurd and Stein during the creation of the book. The only thing I would have liked to see in addition are samples of Hurd's redrawn illustrations for the 1966 edition, but that criticism is extremely nitpicky. In DVD terms, this is really the Special Edition with Bonus Features, and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in Stein's children's book.

LONG TIME READERS might remember a series I did almost two and a half years ago on Gertrude Stein's children's book The World Is Round. There have been many editions over the years, in many different formats, with different illustrations, all of which I examined then, all of which were out of print. But now thanks to Harper Design, The World is Round is back in print in a 75th Anniversary Edition that features the original illustrations, complete with pink paper and blue text, on nice, heavy paper stock. Illustrator Clement Hurd's son Thatcher Hurd, who is also a children's book writer and illustrator, provides a new foreword detailing the publication history of the book along with reminiscences of his father at work. But more importantly, Edith Thatcher Hurd's afterword, which originally appeared in a limited collector's edition in 1986 is included, containing correspondence between Hurd and Stein during the creation of the book. The only thing I would have liked to see in addition are samples of Hurd's redrawn illustrations for the 1966 edition, but that criticism is extremely nitpicky. In DVD terms, this is really the Special Edition with Bonus Features, and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in Stein's children's book.All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on October 08, 2013 17:08

August 16, 2013

PATRICK EATS HIS PEAS BY GEOFFREY HAYES

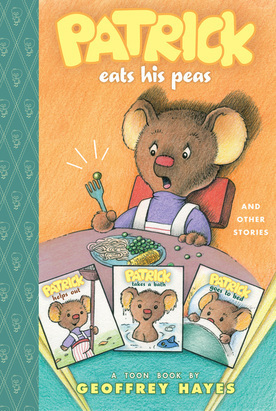

REVIEWING NEW BOOKS is a little off topic for We Too Were Children, but I've been so negligent in my blogging that when my friends over at TOON Books asked if I would review one of their newest releases, I said yes. Better something on the blog than nothing, I figured. And it didn't hurt that it was the new Geoffrey Hayes book, because I love Geoffrey Hayes. So I hope you don't mind taking a look with me at his latest, Patrick Eats His Peas and Other Stories.

REVIEWING NEW BOOKS is a little off topic for We Too Were Children, but I've been so negligent in my blogging that when my friends over at TOON Books asked if I would review one of their newest releases, I said yes. Better something on the blog than nothing, I figured. And it didn't hurt that it was the new Geoffrey Hayes book, because I love Geoffrey Hayes. So I hope you don't mind taking a look with me at his latest, Patrick Eats His Peas and Other Stories.Geoffrey Hayes has been making children's books since 1976, and has over forty titles to his credit. His first book, a picture book entitled Bear By Himself, introduced the appropriately-named character Bear, as he enjoyed a quiet day alone. When Bear appeared again two years later, it was in a book that was over one hundred pages and contained five stories, only now Bear had a name: Patrick. This sudden shift in format was one Patrick would undergo several times as Hayes moved the character from publisher to publisher over the years. Patrick sometimes appeared in a picture book, sometimes in a 8x8 book formatted for a spinner rack, other times as a board book, and most recently in comics. Through each of these incarnations, Hayes often reused stories that had appeared in earlier incarnations, sometimes redrawing the stories from scratch. (See the 1976 and the 1998 editions of Bear By Himself, and the 1989 book Patrick Eats His Dinner below.) With the success of his Benny and Penny comics for TOON Books, it was no surprise that Patrick again followed Hayes to a new publisher and a new format, in a mix of redrawn stories and new ones.

But before Patrick ventured into comics, Hayes garnered critical acclaim (including a Theodor Seuss Geisel Award) for his first foray into the form, his series for young readers Benny and Penny. The Benny and Penny books are masterpieces. Hayes's ability to capture the anxieties, the travails of socialization, and the tribulations of very young children is mind-blowing. Benny and Penny are brother and sister, and their stories take place for the most part in their backyard. They must negotiate playing with each other, meeting new neighbors, playing with friends they don't really like, and braving the dark, all of which they do without adult supervision. Mom is always nearby, and sometimes calls to them from off panel, but really Benny and Penny need to figure things out for themselves. By creating an adult-free world, Hayes allows for his characters and his readers to engage with these social anxieties at an emotional level, the way a child would, and so Benny and Penny and the reader must work through the problem, and find a moral solution. There's none of the heavy-handed guiding message that underpins so many children's picture books. Instead, we get children and situations that ring so true that both children and adults can identify with Benny and Penny, find comfort in recognizing their own insecurities, and learn the lesson by experience rather than by being taught.

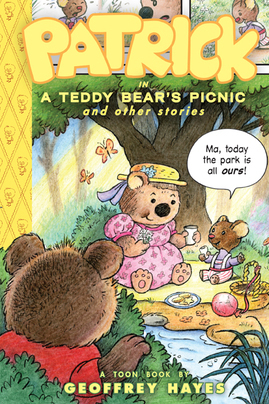

The Patrick TOON books have the same verisimilitude as the Benny and Penny books, but for Patrick, his parents are an ever-present source of security. As a result, Patrick reads as a younger character (even though he gets sent to the store by himself in one of the stories), and his relationship with his parents--his mother in particular--is in some ways the main topic of the books. Yes, Patrick must contend with the childhood annoyances of taking a nap, taking a bath, eating his peas, and many other typical, "Aw, ma, do I have to..." scenarios, but with the exception of a bullying story in Patrick in A Teddy Bear's Picnic, the books are about the interactions between parent and child. The trick then becomes the balance between Patrick's perspective and his parents' perspective.

In Patrick in the Teddy Bear's Picnic, Hayes manages to tip the balance in Patrick's favor. Mom is there, and a parent reader can recognize her amusement and annoyance at some of Patrick's foibles, but Patrick's experience is the one that both the adult and child reader identifies with. This is in part because Patrick is alone in more of the book than he is in Patrick Eats His Peas. He retrieves a balloon at the park, endures nap time, and takes the aforementioned trip to the store. But it is mainly because Mom's actions are the way in which a child would experience them. She is on the sidelines, almost always placid, happy, and comforting, except for rare, and brief, bursts of annoyance. The focus is on what Patrick is feeling, and Mom, as far as he sees it, is just there as a source of support.

In Patrick in the Teddy Bear's Picnic, Hayes manages to tip the balance in Patrick's favor. Mom is there, and a parent reader can recognize her amusement and annoyance at some of Patrick's foibles, but Patrick's experience is the one that both the adult and child reader identifies with. This is in part because Patrick is alone in more of the book than he is in Patrick Eats His Peas. He retrieves a balloon at the park, endures nap time, and takes the aforementioned trip to the store. But it is mainly because Mom's actions are the way in which a child would experience them. She is on the sidelines, almost always placid, happy, and comforting, except for rare, and brief, bursts of annoyance. The focus is on what Patrick is feeling, and Mom, as far as he sees it, is just there as a source of support. In Patrick Eats His Peas, however, the balance tips in the parents' favor, and the book is less satisfying. Here Patrick makes a mess of the leaves his father has just raked, offers similar "help" to his mother in the kitchen, trashes the bathroom during his bath, and insists on making fudge at bedtime. At each of these points, Mom and Dad's expression is highlighted, usually given a full panel to the parent alone, and often in classic cartoon style, with shock lines radiating from her head. This makes the moments feel more like parental observations, than children's conflict. The point seems to be, "Isn't it frustrating (or amusing) when your kid does this?" instead of tackling what Patrick is feeling. In the case of Patrick offering help in the yard and in the kitchen, for example, we don't get the loneliness and boredom of an only child whose parents are both busy. We get the parents' frustration at having their tasks hampered by Patrick's "help." In the end, it makes Patrick Eats His Peas a disappointment. Instead of the insightful parsing of the conflicts of childhood that Hayes is so good at, we get something closer to anecdotes. Is it a bad book? No. It's still Hayes, and therefore better than most children's books. It's just not in the same league as his other TOON books.

In Patrick Eats His Peas, however, the balance tips in the parents' favor, and the book is less satisfying. Here Patrick makes a mess of the leaves his father has just raked, offers similar "help" to his mother in the kitchen, trashes the bathroom during his bath, and insists on making fudge at bedtime. At each of these points, Mom and Dad's expression is highlighted, usually given a full panel to the parent alone, and often in classic cartoon style, with shock lines radiating from her head. This makes the moments feel more like parental observations, than children's conflict. The point seems to be, "Isn't it frustrating (or amusing) when your kid does this?" instead of tackling what Patrick is feeling. In the case of Patrick offering help in the yard and in the kitchen, for example, we don't get the loneliness and boredom of an only child whose parents are both busy. We get the parents' frustration at having their tasks hampered by Patrick's "help." In the end, it makes Patrick Eats His Peas a disappointment. Instead of the insightful parsing of the conflicts of childhood that Hayes is so good at, we get something closer to anecdotes. Is it a bad book? No. It's still Hayes, and therefore better than most children's books. It's just not in the same league as his other TOON books.All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders

Published on August 16, 2013 13:10

July 30, 2013

THE LITTLE WOMAN WANTED NOISE BACK IN PRINT

ALMOST EXACTLY ONE YEAR AGO, I contributed a guest post to Vintage Kids' Books My Kid Loves on the book The Little Woman Wanted Noise by Val Teal with pictures by Robert Lawson. The people over at New York Review Books, who bring wonderful out-of-print books back into print, saw the post and loved what they saw, so they tracked down a copy for themselves. Then they got in touch with me and asked if I had any way of getting in touch with Val Teal's family. At the time, I didn't, but thanks to some internet sleuthing, I managed to actually get in touch with Val Teal's daughter, and to put her in touch with NYRB, and so now, today, a brand new, back-in-print copy of The Little Woman Wanted Noise arrived in the mail. Which means that all of you readers who have spent the last year pining after the book in my post (and those of you who haven't) can buy a new copy now! Well, in a few weeks, when the book is officially released on September 24, 2013. So pre-order! And enjoy.

ALMOST EXACTLY ONE YEAR AGO, I contributed a guest post to Vintage Kids' Books My Kid Loves on the book The Little Woman Wanted Noise by Val Teal with pictures by Robert Lawson. The people over at New York Review Books, who bring wonderful out-of-print books back into print, saw the post and loved what they saw, so they tracked down a copy for themselves. Then they got in touch with me and asked if I had any way of getting in touch with Val Teal's family. At the time, I didn't, but thanks to some internet sleuthing, I managed to actually get in touch with Val Teal's daughter, and to put her in touch with NYRB, and so now, today, a brand new, back-in-print copy of The Little Woman Wanted Noise arrived in the mail. Which means that all of you readers who have spent the last year pining after the book in my post (and those of you who haven't) can buy a new copy now! Well, in a few weeks, when the book is officially released on September 24, 2013. So pre-order! And enjoy.All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on July 30, 2013 17:15

May 7, 2013

SYLVIA PLATH: "THE BULL OF BENDYLAW"

NONE OF SYLVIA PLATH'S children's books were published in her lifetime, but she did see one children's poem in print: "The Bull of Bendylaw," which appeared in the April 1959 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

NONE OF SYLVIA PLATH'S children's books were published in her lifetime, but she did see one children's poem in print: "The Bull of Bendylaw," which appeared in the April 1959 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.The Horn Book is a bimonthly magazine devoted to the discussion of children's literature, along with reviews of children's books, acceptance speeches for major literary awards for children's writers and artists, and occasional poems and stories. The readership includes children's librarians, teachers, children's booksellers, and parents, all of whom use it as a guide for what to read and recommend to children. What that means is, any poem or story published in The Horn Book is likely to reach children through one of these authorities.

As I've discussed in my previous entries on Sylvia Plath, both Plath and her husband Ted Hughes were actively writing for children in the late 1950s. One of their interests was in folktales and ballads, and they each wrote poems drawn from those influences. When Horn Book editor Ruth Hill Viguers approached the couple, asking each to submit poems for consideration, they were able to send several animal poems, which drew on those traditional sources.

Viguers had heard of Plath through a neighbor, but it was when her own children came home from school to say that their English teacher, Mr. Crockett (who had also been Plath's high school teacher) had read Plath's work in class that she chose to reach out to the poet. Not long after meeting with Viguers, Plath sent her husband and her own submissions: "Both of us enjoy writing poems about birds, beasts, and fish, so we are enclosing one from each of us, about an otter and a goatsucker..." In a postscript, she adds "We're adding to the zoo a bull and a field of horses." Only the bull was accepted.

"The Bull of Bendylaw" draws on one of F. J. Child's ballads, and opens with the epigraph:

"The great bull of BendylawPlath, however, associates the bull with the sea, and in her poem "The black bull bellowed before the sea," and the sea breaks forth and floods the kingdom. Not only can the king's men not turn the bull or sea back, but in the end

Has broken his band and run awa,

And the king and a' his court

Canna turn that bull about."

"O the king's tidy acre is under the sea,The poem was later included in Plath's Collected Poems as the first poem in the 1959 section, where the epigraph is relegated to the notes at the back of the book, and so in the long run, the readership for the poem ended up being adults, but Plath and editor Viguers obviously saw the poem as one that could be shared with children, making it a footnote to any discussion of Plath's writing for children.

And the royal rose in the bull's belly,

And the bull on the king's highway."

I owe this entire post to the article in the Horn Book from 2005 by Lissa Paul, "Writing Poetry for Children is a Curious Occupation": Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, which I have cited for all of my Plath entries. And while I did go and see the Horn Book in the library, I was not allowed to take it out, and so the image of the cover comes from the excellent Sylvia Plath website http://www.sylviaplath.info/.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Published on May 07, 2013 08:52

Ariel S. Winter's Blog

- Ariel S. Winter's profile

- 67 followers

Ariel S. Winter isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.