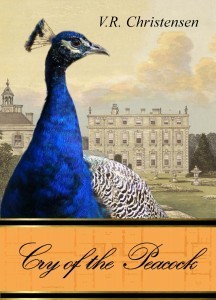

V.R. Christensen's Blog, page 7

August 15, 2012

Book review: Merits and Mercenaries

A Classic Companion by A Lady

Katherine grew naturally into a handsome, intelligent and truly generous young woman, drawing from her aunt’s strength of character—and her late uncle’s sorry lack of it.

And so begins Lady A~’s exquisitely written Austen-esque masterpiece, Merits and Mercenaries. It isn’t very often I’m completely absorbed in a book. So absorbed that I go to bed thinking about the story’s many layered conflict, and dreaming about the characters, planning and plotting in their behalf, trying to sort out in my head just where the story might go, and all the seemingly impossible obstacles that must be overcome to get it there. It was just that way for me as I read this wonderful book.

This was just a superbly written, cleverly concocted, shining example of what Historical Fiction ought be but rarely is. Here were no attempts to modernise the heroine, or even the conflicts of the story. So much of what motivated and concerned humanity two hundred years ago, motivates and concerns us today. On the other hand, here was no overwrought attempt to recreate Austen-esque literature. It was certainly recreated, but the product could hardly be called overwrought. The narrative was natural and flowing and the dialogue absolutely sparkling with wit and charm. The author never once talks over our heads, and when she fears a question may arise, she cleverly refers us to annotations kindly included in the back of the text. This is a welcome embrace to fellow fans of Jane Austen, and, too, of Literary Historical Fiction, as well.

I like complex plots; I yearn for them. I like big, thick books with rich characters that are engaging and compulsively followable. This book gave me both, but in a way I found cleverly deceptive. The conflict was simple. A young woman, Katherine, is taken to the country by her guardian aunt, in the hopes of presenting her with some new prospects for marriage. Of course Katherine is naive to her motivations and goes about her life, adjusting, albeit reluctantly, to the countryside. In Hampshire we are introduced to country society, among them potential friends, some worthy, others not so much. Here among them as well are one or two—or perhaps four—potential suitors. It isn’t a grand mystery for whom Katherine is intended, but the hero is engaged to another. And it’s an unbreakable commitment, assigned to him upon his father’s deathbed. What are two people in love to do? Save, of course, to resign themselves to their unhappy fates. But it isn’t the hero’s prior commitments alone that stand in the way of our dear Katherine’s happiness, for an intricate web of deceit and interference is slowly woven to ensure that Katherine does not prove an irresistible temptation to our would-be hero. For he simply must marry as he has been charged to do. Mustn’t he?

And so we are guided, led, drawn, through each and every page, as if the author were leading us on a long walk, on a warm spring day, on our very first journey through Holland Park, where some new bit of scenery, an unexpected but always pleasant surprise, awaits us at every turn. I look forward with great pleasure—with anticipation—for Lady A~’s next work.

To find out more about the author, please do visit her at:

And please, do get a copy of your own. You won’t regret it!

Merits and Mercenaries is available at these online retailers:

July 15, 2012

On Empathy and Research

I’m not a research historian. I’m sorry if I’ve disappointed you, or if that somehow belittles what I do. But I don’t believe in pretending to be what I’m not. What I am is honest. What I am is empathetic. Now and then, however, I get a little tired of being bombarded by bombastic pedants, who would belittle the work I do (or that my friends do) in order to make themselves look like experts. It happens more than I’d like. And frankly, I’m tired of it.

I’m not a research historian. I’m sorry if I’ve disappointed you, or if that somehow belittles what I do. But I don’t believe in pretending to be what I’m not. What I am is honest. What I am is empathetic. Now and then, however, I get a little tired of being bombarded by bombastic pedants, who would belittle the work I do (or that my friends do) in order to make themselves look like experts. It happens more than I’d like. And frankly, I’m tired of it.

I’ve been posting a lot of research pieces lately, not only on my blog, but in other places. I find such pieces very difficult to write. History is so complex and many layered, and fitting all the necessary details into a 1,000 word post, is often nigh to impossible. Drawing conclusions about those details, making judgments or ‘aspersions’ is…well, it’s dangerous. But it’s also, in my opinion, necessary. How does one learn anything useful or improving without making a judgment, of one kind or another, about it? You don’t. You can’t. For a research historian, perhaps this is right and proper. For a novelist, it’s wrong. And I’ll tell you why.

The fact of the matter is, there are different types of research, necessary for different purposes, and conducted by people who simply function differently and under different motivations. There’s nothing wrong with that. There’s never one way to do anything. What it comes down to is how we think, how our brains function, how we see the world, and what we wish to gain from studying the history of it. Another thing I think it comes down to, is an ability or inability to empathise with historical facts and figures. Because unlike Math or the Sciences, History’s facts and figures are, or rather were, people.

I’m also a sort of a hobbyist psychologist. That is, I study personalities. I find it useful in my writing, but more than that, it’s useful in my daily life. There are basically two cognitive functions, those being sensing and intuition. Those who rely on the sensing cognitive function are great at collecting data, remembering dates, names and places. Such data is easily gathered and stored in the memory of the sensing individual. What can be seen, touched, held, remembered, these matter most.

I’m not a sensing individual. I’m the other kind. The weird one few understand. I can gather data as well as anyone else. What I can’t do is remember it. My brain, as much as I’d like it to, just doesn’t work that way. What I can do, however, and I do it quite well, is it forms impressions of things, I see broad patterns and trends, I can understand, and reproduce, how it may have felt, to live in a certain period of history. I may not be 100% right. It may just be my interpretation. But my guess is as good as anyone’s. I’ve not met anyone yet who possessed a time machine.

What lately helped me to see that this difference in method comes down to individual ability and motivation was an article sent to me by another writer friend. The article is on how most criticism is based on a lack of ability to empathise. Seemingly it has little to do with research. To me it has a great deal to do with it. Do you welcome discussion about your topic of choice? Or do you feel challenged by anyone with a differing opinion? If you cannot see the other person’s point of view, does that not reflect an inability to empathise?

But what about casting judgment? Does my lamenting the wrong done to the Jew in Hitler’s Germany (and elsewhere) mean I have an inability to empathise? Or do I, in feeling sorrow for their plight, in feeling the weight of that tragedy, judge Hitler and his minions? I do both, of course. Hitler was an evil man. I have judged him. Now, to do justice to history, I must try to understand him, to try, if I can, to learn what made him into the monster he became.

I do understand the caution against making simple judgments about historical figures and events. There is nothing at all simple about history, because there is never anything simple about people. For me, it isn’t enough to simply learn about history. I want to learn from it. I want to delve deeper, to explore the hows and whys of it all. Dates and facts and names will get me so far. I want to go farther. Eventually I am going to make a judgment. I am going to ask myself if I would have behaved similarly in their shoes, and why or why not. I’m going to ask myself what prices we are still paying for the decisions made by the men and woman who came before me. How is life better? How is life worse?

We cast judgments. It’s what we do. The irony is that those judgments, historically speaking, are rarely about individuals. They are about the pitfalls of vice, or the rising and falling of civilisation. I wouldn’t dare cast a judgment on a husbandless mother in Victorian England, but I can look back on it and make judgments about the conditions that placed women in such desperate situations, or that would starve children and drive them to work, scampering up chimneys and working on the streets to bring home (if they had a home) enough to eat. Did they understand it then the way we understand it now? Possibly not. And so my job, then, is to try to stand in their shoes. To try, if I can, to look at it from every angle, from the gentleman’s wife who doesn’t want the dirty little beggar in her house, to the gentleman’s children who wonder what it’s like inside a chimney, or if the little fellow doesn’t want a bit of tea. Life was different then. It wasn’t so different as to remove human feeling.

But I’m not a historian. What I am is a novelist whose primary aim is to teach, and to do it in a setting that is as accurate as humanly possible. The problem is, history is, well, history. None of us has ever spent any actual time in the Regency or Georgian or Victorian eras. None of us really knows what it was like. What we can do is read as much as we can, try to immerse ourselves in the atmosphere of it, read biographies, and histories, and studies. Better than that, read letters and journals and other contemporary publications. And then put ourselves in the shoes of those who walked there. This requires passing judgement, presuming, if you will, upon history. But as a novelist, it’s the very best thing I can do for my books, and for my readers.

But I’m not a historian. What I am is a novelist whose primary aim is to teach, and to do it in a setting that is as accurate as humanly possible. The problem is, history is, well, history. None of us has ever spent any actual time in the Regency or Georgian or Victorian eras. None of us really knows what it was like. What we can do is read as much as we can, try to immerse ourselves in the atmosphere of it, read biographies, and histories, and studies. Better than that, read letters and journals and other contemporary publications. And then put ourselves in the shoes of those who walked there. This requires passing judgement, presuming, if you will, upon history. But as a novelist, it’s the very best thing I can do for my books, and for my readers.

Rightly or wrongly, it all comes down to empathy. Agreeing or disagreeing with another person’s research, unless the bare facts are just wrong, comes down to empathy, too. Can you see how they came to their conclusion? If you disagree, then why? Is it because you know more, and you are the expert and how dare anyone challenge you? Is it an inability to see where they came from? And do you care?

Personally, I find the world more interesting with different points of view. No one owns a monopoly on history. I know I don’t. And people aren’t afraid to remind me of the fact. I’m happy to discuss it, so long as you can do it in a friendly and respectful manner. If not. Move along. I’ve got some research to do.

July 9, 2012

The Mystery of Mary Rogers

Mary Rogers and her mother, Phoebe, arrived in New York in 1837. For the first few months of their residence, they lived with a gentleman named John Anderson, who owned a tobacconist shop. Anderson employed Mary and there she earned a sort of celebrity. She was universally considered a striking beauty and had many admirers, all of which, of course, were pleased to buy tobacco from Mr. Anderson. The hiring of attractive shopgirls was a common practice in Europe. It was still considered rather indecent in the US. Still, Mary needed the work, and Anderson paid her well to maintain her post safely behind the shop’s counter.

Mary Rogers and her mother, Phoebe, arrived in New York in 1837. For the first few months of their residence, they lived with a gentleman named John Anderson, who owned a tobacconist shop. Anderson employed Mary and there she earned a sort of celebrity. She was universally considered a striking beauty and had many admirers, all of which, of course, were pleased to buy tobacco from Mr. Anderson. The hiring of attractive shopgirls was a common practice in Europe. It was still considered rather indecent in the US. Still, Mary needed the work, and Anderson paid her well to maintain her post safely behind the shop’s counter.

In October of 1838, Mary disappeared. Her mother found a note on her dressing table which bid her “an affectionate and final farewell.” It was speculated that she had been disappointed in love. She had recently had a suitor, it was said, who had deserted her, and some believed she had gone with the intention of taking her own life. Others speculated she had eloped. A search party was organised, but Mary returned on her own, some say a few hours later, others claim it was a matter of weeks. The following day, the motivation of suicide was reported to have been a hoax, and that the letter had either never existed, or had been written by someone with an eye toward mischief. When exactly Mary returned, it is unknown, but it is known that it was a matter of a few weeks before she returned to work. Anderson, naturally, was quite worried for her. Some say he made a public plea for her to come home. His interest in the family, and the true nature of his relationship with them, is a point of interest to those who study the mystery today.

In time, talk of Mary’s disappearance and subsequent return quieted, and she continued her work at Anderson’s Tobacco Emporium. In 1839, having come into a little money, she and her mother purchased a boarding house and she left Anderson’s shop. Here Mary was once more beset with suitors, two of which being Alfred Crommelin, a polite gentleman with good manners and elegant bearing, and Daniel Payne, a cork cutter, who was known to be hot tempered and inclined to drink very heavily, even by the standards of the day. Both gentlemen were lodgers in the boarding house.

By June of 1841 Payne was recognised as Mary’s preferred suitor. Crommelin returned to the boarding house one evening to find Payne and Mary engaged in “unseemly intimacies”. He rebuked Payne for his ungentlemanly behavior and quit the house for good. Before going, he apologised to Mary for the step he was taking and begged her to remember him if she should everfind herself in trouble. And then he was gone.

In July Mary disappeared a second time.

According to reports, Mary arose before dawn on 25 July 1841, helped to prepare breakfast for her mother’s lodgers and attended her various morning chores. Shortly before ten o’clock she knocked at Payne’s room and she informed him, through the half open door, that she was going to visit her aunt, Mrs. Downing, who lived fifteen minutes away by omnibus. It was her plan to return in the early evening, and she wished for Payne to meet her so that he might escort her safely home.

A few days earlier, according to some reports, Mary had been persuaded by her mother to break off her engagement to Payne. That same day, Crommelin received a note asking him to call at the boarding house. When he arrived at his office, he found a second note, written on a chalk slate. Despite her summons, and the romantic intentions implied by the red rose she left in his keyhole, Crommelin did not go to the boarding house again.

Payne, on the day of Mary’s visit to her aunt, kept himself busy by visiting his brother, a market, a tavern then an eating house before going home to take a long nap. He arose in the evening and went to meet Mary, and only then realised the omnibus did not run on Sunday. An approaching storm soon drove him back home, where he decided Mary must spend the night at her aunt’s.

The following morning, Mrs. Rogers was in great anxiety, for Mary had not returned home. Payne was not yet worried, and so went to work, but when he returned at lunchtime, and finding Phoebe in an even more anxious state and Mary still not at home, he went then to the aunt’s house to discover that Mary had never arrived there. Nor had the aunt ever expected her. He posted an ad in the paper giving Mary’s full description, and then returned to the boarding house, where Mary’s mother was now in a state of lethargy.

On Tuesday, Payne went to a tavern on Duane Street, where Mary was said to have passed several hours, but upon arriving there he found the description did not match Mary’s at all. From there he went to the ferry launch at Barclay street which crossed the Hudson to Hoboken, where he asked several strangers, and stopped at a few homes along the way to find out if Mary had been seen there. He then wandered on toward Elysia Fields, where he continued to make inquiries

Crommelin was now aware of Mary’s disappearance, but took no action until Wednesday when he was shown the missing person’s report that Payne had put in the paper. He hurried to the boarding house, where he found Phoebe, glassy eyed and in a state of mourning, and Payne standing at her side. Crommelin, then began a search of his own, retracing the steps Payne had taken the day before, going to Hoboken, and then to Elysian Fields.

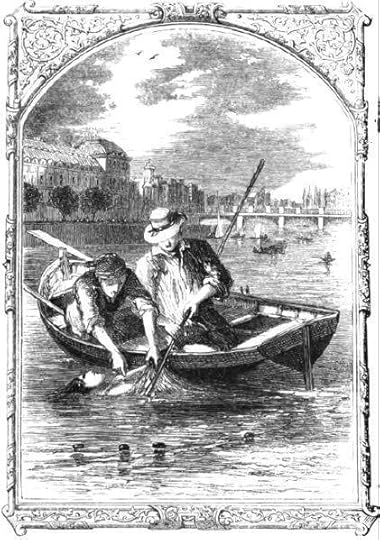

While he was searching Hoboken, a body was found floating in the river. Two men in a rowboat towed it to land and the body was pulled ashore.  Crommelin pushed his way through the crowd to see it. What he saw must have shocked him a great deal. He certainly could not have recognised her by her face. To identify her, he ripped open a portion of her sleeve and examined the hair on her arm. This, evidently providing ample proof, he declared it to be Mary Rogers, then crouched protectively over the body until the crowd dispersed and an official was called to the scene.

Crommelin pushed his way through the crowd to see it. What he saw must have shocked him a great deal. He certainly could not have recognised her by her face. To identify her, he ripped open a portion of her sleeve and examined the hair on her arm. This, evidently providing ample proof, he declared it to be Mary Rogers, then crouched protectively over the body until the crowd dispersed and an official was called to the scene.

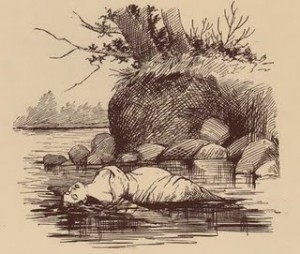

Dr. Richard H. Cook, the New Jersey coroner, was the first to arrive. It was a hot July day, and the condition of the remains threatened to deteriorate further as her body veritably consumed itself in the heat. When at last the justice of the peace appeared on the scene, the body was removed to a nearby building and the autopsy was performed. The face he examined was suffused with bruised blood. She had clearly been beaten, and there was no foam in her mouth or lungs. This was no drowning victim. On her neck, he observed deep bruising in the shape and approximate size of a man’s hand. As he examined the marks more closely, he found that a piece of lace was tied so tightly around her throat that it had embedded itself into her skin. He had not so much as seen it, but felt the knot which was situated just behind her ear. The undergarments of her clothes were found in disarray, and, upon closer examination, he found evidence of bruising and abrasions in the “feminine region”. He concluded she had been raped by no fewer than three assailants. Her arms had been positioned as if her wrists had been tied together, and the abrasions caused by the tethers seemed to indicate she had tried to raise her hands to her mouth. A loop of linen was found tied loosely about her neck, as if it had been used as a sort of gag. These strips had been torn from her own clothes, which matched precisely the description of those last seen upon Mary Rogers. What’s more, a foot wide strip of fabric had been torn from her petticoat and wrapped around the body to form a sort of hitch to aid in the carrying of the corpse. Her hat had been tied on her head with a sailor’s not, rather than the typical knot tied by a lady, suggesting it had been replaced by her assailant or someone connected with the crime, before her body was thrown in the river.

About the time the autopsy began, one of the men, H.G. Luther, who had pulled the body from the water, arrived at Mrs. Roger’s home to deliver the news. Payne was there, standing protectively by her side. They received the news with apparent indifference. Perhaps it was resignation. But the lack of emotion was curious to Luther. Even more curious, Payne took no action that night. It was still early. He might easily have gone to Hoboken. He might have hoped to add a second witness to the identification of the body. He might have gone with a hope of finding that Crommelin had been mistaken. He stayed at home with Mrs. Rogers.

In the time it took for the officials of New Jersey and New York to decide who would take responsibility for investigating the death of Mary Rogers, rumors and speculations began to fly from every direction. For a time it was believed Mary had fallen into the hands of one of the many and notorious gangs that frequented the Hoboken area. Others were certain it was one of her jilted lovers. Some felt it wasn’t Mary at all, supported by the belief that a body that was in the water for no more than three days could not have decomposed to such an extent, or even, for that matter, risen to the surface.

Of course Payne and Crommelin were suspects. Payne’s alibi, at least for the first few days of Mary’s disappearance, were solid. He had been with his brother, had frequented taverns and eating places, and witnesses could attest to his being there. Crommelin, too, was a suspect, but as he had been so outspoken and proactive in finding her, and then in discovering the killer, it seemed impossible it could be him.

And then, on the 25th of August, as two boys were hunting for sassafras bark in a thicket in the woods near Weehawken, some articles of clothing were found. Among them was a petticoat, an umbrella, a silk scarf and a handkerchief with M.R. embroidered upon it. The boys took the articles to their mother, the owner of a nearby tavern, who put them away, and then, a day later, took them to the police. Frederica Loss’s tavern was very near, and often frequented by those who visited, Elysian fields. Mrs. Loss, upon being questioned, remembered, if rather belatedly, that a young woman of Mary’s description had been seen at her establishment. She had been accompanied by a young man of ‘swarthy complexion’, and went on to describe Mary’s attire and appearance exactly. Mrs. Loss told police that a short time after the couple left, she heard screams issuing from the area of the thicket. She thought it was her son, whom she had sent out again, but he returned a short time later unharmed.

And then, on the 25th of August, as two boys were hunting for sassafras bark in a thicket in the woods near Weehawken, some articles of clothing were found. Among them was a petticoat, an umbrella, a silk scarf and a handkerchief with M.R. embroidered upon it. The boys took the articles to their mother, the owner of a nearby tavern, who put them away, and then, a day later, took them to the police. Frederica Loss’s tavern was very near, and often frequented by those who visited, Elysian fields. Mrs. Loss, upon being questioned, remembered, if rather belatedly, that a young woman of Mary’s description had been seen at her establishment. She had been accompanied by a young man of ‘swarthy complexion’, and went on to describe Mary’s attire and appearance exactly. Mrs. Loss told police that a short time after the couple left, she heard screams issuing from the area of the thicket. She thought it was her son, whom she had sent out again, but he returned a short time later unharmed.

The discovery of the ‘murder thicket’ raised as many questions as it answered, however. It was so close, and so overgrown, that a person could only enter it on hands and knees. There were many footprints about, the clothing found had been caught on brambles, had mildewed and been overgrown with grass. If the path to the tavern was so well travelled as to give Mrs. Loss a steady flow of customers from Elysian Fields, how was it possible the articles were never seen before? How was it possible, through the July and August rains, that the footprints still remained? Was it likely a man would attempt a murder so nearby the tavern, a mere 400 yards away?

It was suggested by some that Mrs. Loss had planted the articles there herself. The truth of this is impossible to know, but she certainly enjoyed a brisk business after the discovery, for there were many who came to get a glimpse of the place for themselves.

Payne was one of them, but he got no pleasure from viewing the scene. At ten o’clock on October 7, he arrived at a nearby tavern, where he ordered a drink and announced, “I’m the man that was promised to Mary Rogers. I’m a man in a great deal of trouble.” It seems he left the tavern and arrived at the thicket with a bottle of laudanum in hand. Upon entering the thicket, he drank it down and crushed the bottle against a rock. Two hours later he was found dead with a note in his pocket. “To the World—Here I am on the spot; God forgive me for my misfortune in my misspent time.” There was also a bundle of papers in his pocket. What they contained was never revealed. It is assumed by most, that they contained nothing of import. At the time, the silence of the investigators on the subject aroused a great deal of speculation.

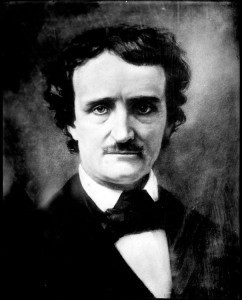

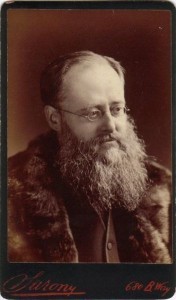

Poe, eager for the same success he had experienced with The Murders in the Rue Morgue, found an opportunity to employ his deductive reasoning skills, or, as he preferred to call it, ratiocination. C. Auguste Dupin was called into action again, and this time, he bragged, would perform the feat of solving the mystery from his armchair and by using only the newspapers for his source. How accurately anyone can determine a true cause of a crime from newspapers is beyond me. Sensational journalism is not factual reporting by a long shot, as I mean to prove in an upcoming post. (Link to come.)

What Poe did manage to convince his readers of, was that the murderer had acted alone. Why else would he need the aid of the ‘hitch’ found tied around Marie’s waist. He also connected Mary’s first disappearance with her first, suggesting that the sailor with which she had meant to elope the first time, had returned from sea. He also went on to suggest that perhaps a falling out had occurred, and the romance ended, instead, in tragedy.

But that wasn’t the conclusion his readers received.

Poe’s manuscript was some 20,000 words in length, and so it was published in three parts. At this point two of the three had been published. The third promised to “indicate the assassin.” But it had not yet hit the presses when the New York Tribune published headlines that read “THE MARY ROGERS MYSTERY EXPLAINED.”

Indeed, new evidence had arisen that blew all of Poe’s theories out of the water. He revised the third part to sort of indicate he knew the solution all along. All it succeeded in doing was muddying the waters of his ‘ratiocinating’. He ends by telling his reader that Dupin has solved the mystery, that all will soon know it, but for the sake of justice and respect for the police, he will leave them to tell the tale. Years later he would take another stab at realligning his solution with that which was soon to be the commonly accepted one. He added passages and footnotes that, for the first time, showed a direct relation to Mary Rogers. He also added a caveat, that he might have been better prepared to solve the mystery had he been in New York, and not had to rely on the papers, a complete reversal of his earlier boastings of the skill of a detective who could solve a mystery from his armchair.

So what was the evidence that reduced Poe’s Marie Roget into inconclusive and muddled literary nonsense?

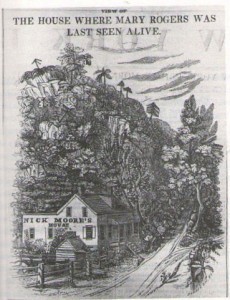

On November 1, 1842, Police arrived at Nick Moore’s Tavern in Weehawken to discover that Mrs. Loss had been accidentally shot by one of her sons, who was later heard to remark, “The great secret will come out.” What was that secret? For some time, it seemed, Mrs. Loss had been under the attention of the investigative police in connection with a famous abortionist named Madame Restell, whose services were advertised in huge, prepaid advertisements published on the back of every paper in town. Her money was not spent at the papers’ alone, but to the police as well, who arrested her on several occasions, but always released her again. Perhaps her habit of paying her $10,000 bail money in cash (and with an extra $1,000 as a tip) helped her some.

Though Madame Restell was somewhat protected by the police, she was considered an enemy to the people, and to society at large . Giving birth alone came with incredible risks. Add to that poisons, unctions of curious make, unsanitised instruments, the mortality rate was astounding. Mary’s body was not the first to be pulled from the Hudson river, merely the most famous. She had so far been lauded as a chaste, respectable maiden. What was she now? That Madame Restell was a millionaire with a brownstone mansion only attested to how sought after were her skills. Sad to think what combination of circumstances would have driven these women to seek her services.

But Madam Restell was rather expensive. Who did you go to if you could not afford her? Why she would refer you to some of the other foetocidal houses in the city, those who charged less and were less proficient in their trades.

The conclusion of Mary’s mystery was accepted by most. It provides a not quite tidy solution. Mary’s mother seemed to have known that when Mary left she was going to her death. It would explain her stoicism upon the news that Mary’s body had been found. She had gone to have an abortion. Had it been a success, she would have returned already. It explains why Mary went to Crommelin to begin with. It was said she went to him to exchange a boarder’s IOU for money. A sum of some fifty dollars. If Payne were the father, it might explain his apparent guilt at her death. It might explain why Crommelin was hesitant to help her. Perhaps she meant, by leaving the rose in the keyhole, that she mi ght marry him instead, were he to help her. Perhaps his not giving her the money was the reason she went to Mrs. Loss rather than Madame Restell.

ght marry him instead, were he to help her. Perhaps his not giving her the money was the reason she went to Mrs. Loss rather than Madame Restell.

But if this soon to be accepted solution provided answers to these questions, it left many more unanswered. If she had died at the hands of an abortionist, what need had they for a garote to strangle her? Why was she so violenty beaten and strangled? Was it to disguise what had really happened? Or was it a combination of the two? Had she gone to have the abortion? Had it been a success? Had she met Payne and refused to marry him. Had he killed her? Or had she died under Mrs. Loss’s roof after all? No one, it seems, will ever really know. They Mystery of Mary Rogers, remains, and will likely always remain, a mystery.

July 4, 2012

Edgar Allan Poe and the beginning of Crime Reporting (Stateside)

Over on Goodreads we’re having a discussion about Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin Mysteries. Some really interesting discussion has been going on there, and the question of the history of Crime reporting and detective novels came up. Last October, during my Poe-athon, I bought, but did not read, “The Beautiful Cigar Girl” by Daniel Stashower. As I’ve already read the Dupin Mysteries, I decided it was time to read “The Beautiful Cigar Girl”. This is one riveting book, and I highly recommend it if you are a fan of Poe or even of murder mystery and reporting.

Over on Goodreads we’re having a discussion about Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin Mysteries. Some really interesting discussion has been going on there, and the question of the history of Crime reporting and detective novels came up. Last October, during my Poe-athon, I bought, but did not read, “The Beautiful Cigar Girl” by Daniel Stashower. As I’ve already read the Dupin Mysteries, I decided it was time to read “The Beautiful Cigar Girl”. This is one riveting book, and I highly recommend it if you are a fan of Poe or even of murder mystery and reporting.

I find it interesting that the subtitle of the book is “Mary Rogers, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Invention of Murder.” Also on my soon to be read list is Judith Flanders’ most recent book, “The Invention of Murder.” It’s an intriguing premise if you think about it. Murder was not invented in the Victorian era, but, rather, the reporting and sensationalising of it was. What does this have to do with Poe’s Dupin Mysteries? And how do they influence the detective novels that followed, such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes? The answers are in Stashower’s book, and for the sake of the current discussion going on at Goodreads, I’m making an attempt to roughly delineate them here.

In 1825 “The Kentucky Tragedy” went to trial. Known as the Beauchamp-Sharp murder case, it involved a young woman, Ann Cooke, who was seduced and cast aside by Colonel Solomon P. Sharp, solicitor general of Kentucky. She had his child and then turned to another suitor, Jeroboam O. Beauchamp, whom she agreed to marry if he would avenge her honor. Sharp would not agree to a duel and so Beauchamp, donning a disguise, stabbed him to death. Beuchamp received a death sentence and on the eve of his execution, Ann joined him in his cell where they both attempted suicide by poison and self inflicted stabbing. She died that night. He lived long enough to be hanged.

The story inspired many people to write about it, including Poe, who, finding it the stuff of Shakespearian drama, placed it in an Italian setting and began to serialise it. It was not received well, and when a close friend advised him he would do better staging his stories in France, Poe abandoned the story.

At the time, Poe was editing and writing for The Messenger. His best pieces were generally considered to be literary criticism. One of these he criticised, and quite soundly was a book called Norman Leslie by Theodore Faye. Faye had taken his story from sensationalised and highly pulicised Manhattan Well Murder in 1800, which was said to have been the first recorded murder trial in US history.

The Manhattan Well Murder involved the murder of a young woman named Gulielma Sands, who disappeared on the evening of 22 December 1799 after telling her cousin that she and her fiance, Levi Weeks, were to be secretly married. Two days later, some of her belongings were found near Manhattan Well in Lispernard Meadows, known as SoHo today. On 2 January, her body was recovered from the well. Weeks, who had been seen with Gulielma the night of her murder, and who, on the Sunday previous, had been seen taking measurements of the well, was the chief suspect. The trial was held on 31 March and 1 April, 1800, and after five minutes of deliberation, Weeks was acquitted.

Poe called Fay’s work “the most inestimable piece of balderdash with which the common sense of the good people of America was ever so openly or villainously insulted.”

The book, as was the trial so many years before, had proved quite popular with readers, and Poe’s criticism, which was usually respected, was met on this occasion with vehement disapproval on this occasion.

Though the Manhattan Well Murder was the first to be reported, the first efforts in crime and investigated reporting are generally attributed to James Gordon Bennett. Working as a reporter for the Enquirer, Bennet covered a sensational murder trial in Salem, Mass, of a retired sea captain, Joseph White, who had been murdered in his bed. (Incidentally, some say this story inspired Poe’s the Telltale Heart.) The state attorney general, however, issued a set of restrictions forbidding any further investigative reporting on the case. Of course Bennett, who felt (or at least declared) that he was performing a public service, was outraged.

Six years later, in 1836, when another sensational murder was in the public’s attention, Bennett, now the owner of his own very successful newspaper, seized upon the opportunity to advance the cause of journalism by “discovering and encouraging the popular taste for vicarious vice and crime.” Helen Jewett was a prostitute savagely murdered with an axe and then set fire to. Polite society was shocked by the very detailed reports which appeared in Bennett’s paper. No other paper felt the subject fit for print. Bennett felt otherwise. As he proclaimed when he was refused his right to report upon the murder in Salem, “It is an old, worm-eaten Gothic dogma of Courts to consider the publicity given to every event by the Press as destructive to the interest of law and justice. . . . The press is the living Jury of the nation.”

Six years later, in 1836, when another sensational murder was in the public’s attention, Bennett, now the owner of his own very successful newspaper, seized upon the opportunity to advance the cause of journalism by “discovering and encouraging the popular taste for vicarious vice and crime.” Helen Jewett was a prostitute savagely murdered with an axe and then set fire to. Polite society was shocked by the very detailed reports which appeared in Bennett’s paper. No other paper felt the subject fit for print. Bennett felt otherwise. As he proclaimed when he was refused his right to report upon the murder in Salem, “It is an old, worm-eaten Gothic dogma of Courts to consider the publicity given to every event by the Press as destructive to the interest of law and justice. . . . The press is the living Jury of the nation.”

The man wanted to sell papers, in my opinion, and that was all. Neither did he limit his reporting to fact. Though he did visit the murder scenes, though he did dig into the histories of the victims and suspects, he often took an opposing course to those who, realising the profits the Herald was making, followed in his footsteps and covered the trial as well. When the murderer was discovered, and his conviction sure, Bennett took the opposing view (no doubt with a mind to sell a few more papers) and declared the suspect innocent. Enough of his readership sympathised with Bennett’s version of the murder’s story, that he walked free, though Bennett himself later admitted to believing in the man’s guilt.

In 1840 Poe was working for Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine, for which he wrote and published “The Man of the Crowd”, which took up, as “Politan” had, the workings of the criminal mind, and in which, using the art of deduction, the narrator reads the histories of passers by from observing the minutest details in their appearances.

In 1841, Poe exercised his literary exercises in deductive reasoning once again in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”, and drew (for perhaps the first time) a great deal of positive notice. However, a handful of reviewers pointed out “there could be no great skill in presenting a solution to a mystery of the author’s own devising.” Poe understood that the effect of the story was accomplished by his having written it backwards. The idea of unraveling a web which he himself had woven troubled even him. He wanted to be the detective himself, and to apply these powers of deductive reasoning on a real case. The story by which he would find such an outlet was unraveling as he pondered upon this problem, and the fact that it was already the most sensational murder in U.S. history provided him with an already certain audience.

In 1841, Poe exercised his literary exercises in deductive reasoning once again in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”, and drew (for perhaps the first time) a great deal of positive notice. However, a handful of reviewers pointed out “there could be no great skill in presenting a solution to a mystery of the author’s own devising.” Poe understood that the effect of the story was accomplished by his having written it backwards. The idea of unraveling a web which he himself had woven troubled even him. He wanted to be the detective himself, and to apply these powers of deductive reasoning on a real case. The story by which he would find such an outlet was unraveling as he pondered upon this problem, and the fact that it was already the most sensational murder in U.S. history provided him with an already certain audience.

Mary Rogers was already a celebrity when her body was pulled from the Hudson River on 28 July 1841. Having worked for some time behind the counter at Anderson’s Tobacco Emporium, she was well known to much of the city as the beautiful cigar girl. Posters were made of her and she was very much admired.

If the case of Mary Rogers was fodder for Poe, it was also fodder for Bennett, who took up the case as his symbol for moral reform. But as he’d already set the pattern for investigative and sensational crime reporting, so did others, and the murder of Mary Rogers became an instant sensation.

As the murdered woman was from New York, and the body found in New Jersey, weeks went by before any real investigations occurred. In the mean time, theories were bandied about between the papers. Bennett began reporting about the incompetency of the men of law in both New York and New Jersey, and it was largely owing to him that the necessary money was raised to pay the investigators and to offer a reward for finding the murderer. Still the case stagnated, and when, a year later, the unsolved case seemed to have been very nearly forgotten, Poe put pen to paper, once more revived C. August Dupin, and attempted to solve the crime for himself, using his own genius and powers of deductive reasoning and relocating the story into that French setting he was so expert creating.

What was Poe’s conclusion? The present version of “The Mystery of Marie Roget” does not give it. Poe seems to have ramped himself up to some grand revelation and then omitted it. In truth, Poe’s conclusion was wrong. What is the true story of Mary Roger’s death? Well, I’m only half way through the “Beautiful Cigar Girl”, and the discussion of the story on Goodreads has not yet begun, and so, perhaps, I’ll save the details of her murder for next week.

June 11, 2012

And they lived happily ever after . . .

…or not.

While I read a lot of non-fiction books about the Victorian era, I spend as much time, if not more, in fiction contemporary to the era, Dickens, Meredith, Hardy, Eliot (etc., etc., etc.) Here I get a real feel for what it was like to live then. I get the atmosphere and the nuances of language and setting that it’s hard to get in non-fiction (with perhaps the notable exception of Judith Flanders and Gillian Gill, who seem to write their non fiction works as engagingly as the best authors write their prose.)

While I read a lot of non-fiction books about the Victorian era, I spend as much time, if not more, in fiction contemporary to the era, Dickens, Meredith, Hardy, Eliot (etc., etc., etc.) Here I get a real feel for what it was like to live then. I get the atmosphere and the nuances of language and setting that it’s hard to get in non-fiction (with perhaps the notable exception of Judith Flanders and Gillian Gill, who seem to write their non fiction works as engagingly as the best authors write their prose.)

The sad fact is, however, that when it comes to writing weddings, fiction is an infertile crop. There’s nothing there. Weddings are mentioned briefly, or described as something that took place. We hear of the befores and afters, and then there is a blank … wherein we are meant, I suppose, to assume that the honeymoon took place and the maiden emerges a bride like a butterfly from it’s cocoon. But I wonder how often that was truly the case, particularly when women, by and large, were ignorant of the facts of life, while men were oft times all too familiar. Of course it is the common argument that a woman having grown up on a farm understood the laws of reproductive science. This may or may not be true. It was certainly not the case for Hardy’s Tess, and I have to wonder if the average Victorian maiden would even have supposed that the way of animals was the way of humans when the lights were out and clothes were off. Or, in Tess’s case … well, you get my point.

A young woman, dreaming of married life, preparing herself for it, turned to the many etiquette guides available and read advice columns on how to keep a house and how to be a good wife in all matters publicly observable. But on the actual ceremonies (formal and informal) of being married, here again we find a lack of useful information. And, more often than not, these etiquette guides provide a great deal of room for argument. They are not, after all, records of what people did, but a guideline of what the ideal situation should call for.

A young woman, dreaming of married life, preparing herself for it, turned to the many etiquette guides available and read advice columns on how to keep a house and how to be a good wife in all matters publicly observable. But on the actual ceremonies (formal and informal) of being married, here again we find a lack of useful information. And, more often than not, these etiquette guides provide a great deal of room for argument. They are not, after all, records of what people did, but a guideline of what the ideal situation should call for.

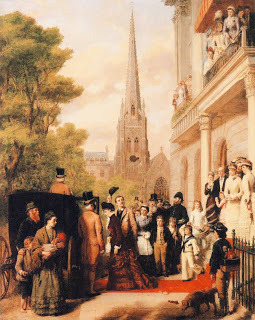

So then, what exactly was involved in the average Victorian wedding? If, indeed, there ever existed such a thing.

From the point of proposal, the parents granting consent, a date being set, legal and financial matters having been decided, the first thing to be done was to announce the intentions of the couple to the local clergyman. According to The Marriage Act of 1753, the couple must have the announcement published (by banns) for three consecutive weeks. If the couple lived in different parishes, the banns must be read in both parishes. The marriage must be performed by an Anglican clergyman and both parties, unless given consent by a parent or guardian, must be 21. (Of course the laws changed throughout Victoria’s reign, and by mid-century there were allowances for other faiths, as well as for secular marriages. I should consequently note that this is not a concise guide, simply an idea of what it might have been like for the ‘average’ couple. If, once again, there was such a thing.)

In Regency literature we often hear of ‘special licenses’ which were rather expensive and implied a certain amount of haste to the union. They were also so prohibitively expensive that they were reserved for those of high rank and connection. A respectable Victorian, however, had a third option. An ordinary license, at a cost of £2 2s 6d. What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew, (which is an entertaining read, if not actually very scholarly, as it lumps the Victorian and the Regency eras together) quotes a mid-century etiquette manual as saying: ‘Marriage by banns is confined to the poorest classes, and a license is generally obtained by those who aspire to the “habits of good society.’

There is much more to all this than I have time for here, but for a more detailed outline of the laws governing marriage look here and here. And also at Jennifer Phegley’s thoroughly concise book Courtship and Marriage in Victorian England. (I’ve also relied heavily on Mary Lyndon Shanley’s Feminism, Marriage and the Law in Victorian England, and on the a reprinted book The Married Women’s Property Act, 1882)

In an age where waste was thing to be avoided at all costs, the bride’s dress was either chosen from the very best of that which she already owned, or it was bought special with the idea of being worn again. Victoria herself set the trend for wearing white at her own wedding in 1840, but it was hardly a universal custom even fifty years later.

The service, assuming it was an Anglican service, was read from the Book of Common Prayer. (For an example of how just such a wedding might play out, see here. WARNING, SHAMELESS PLUG.)

And at last we come to that crucial element: the kissing of the bride! Did it, or did it not take place within a Victorian wedding ceremony? Well, the jury is out, and believe me, I’ve done my research. The following is from the 1873 publication, The Bazaar Book of Decorum. The Care of the Person, Manners, Etiquette, and Ceremonials.

When the ceremony is over, the question sometimes arises whether the bride is to be kissed by the bridegroom. We should leave its decision to the instinct of affection were we not solemnly warned by a portentous authority on deportment that “the practice is decidedly to be avoided; it is never followed by people in the best society. A bridegroom with any tact will take care that this is known to his wife, since any disappointment of expectations would be a breach of good breeding.” The bride is congratulated by all her friends in the church, and elderly relatives will kiss her in congratulations: This is, of course, now settled beyond all peradventure of doubt by the fact that, according to the same authority, “The queen was kissed by the Duke of Sussex, but not by Prince Albert.”

This is one of those cases where I find the etiquette guide rife with opportunity for argument. For example, as it states, in 1873, “the question sometimes arises.” So evidently there was room for this question to be asked. Is it done, or isn’t it? Which implies some see it done, or hear of it’s being done, (wish for it to be done?) have wondered if it should be done, and from other sources have heard that it is a practice to be avoided. To me this only proves that it is hardly an established rule. And the idea that the matter should be discussed beforehand leaves me simply reeling with ideas for plots. Can you imagine it? Cecil asks of Lucy, “My dear, do you think I might be allowed a kiss at the end of the ceremony?” “Why Cecil, upon the completion of the ceremony I am yours to do with what you will.” Ok, yes, that’s just my mind running rampant on the subject, (and perhaps A Room With a View does not provide the best characters from which to draw. The story, I’m sure, would be quite different were it George rather than Cecil, who’d no doubt take advantage of an impulsive moment, whether Lucy, or the crowd, objected or not. [And yes, I am aware Forrester is Edwardian and not Victorian.]) At any rate, the mere suggestion that there should be a discussion beforehand, and that the bride might be disappointed, only leads me to suspect there were as many ceremonial kisses as there were not.

This is one of those cases where I find the etiquette guide rife with opportunity for argument. For example, as it states, in 1873, “the question sometimes arises.” So evidently there was room for this question to be asked. Is it done, or isn’t it? Which implies some see it done, or hear of it’s being done, (wish for it to be done?) have wondered if it should be done, and from other sources have heard that it is a practice to be avoided. To me this only proves that it is hardly an established rule. And the idea that the matter should be discussed beforehand leaves me simply reeling with ideas for plots. Can you imagine it? Cecil asks of Lucy, “My dear, do you think I might be allowed a kiss at the end of the ceremony?” “Why Cecil, upon the completion of the ceremony I am yours to do with what you will.” Ok, yes, that’s just my mind running rampant on the subject, (and perhaps A Room With a View does not provide the best characters from which to draw. The story, I’m sure, would be quite different were it George rather than Cecil, who’d no doubt take advantage of an impulsive moment, whether Lucy, or the crowd, objected or not. [And yes, I am aware Forrester is Edwardian and not Victorian.]) At any rate, the mere suggestion that there should be a discussion beforehand, and that the bride might be disappointed, only leads me to suspect there were as many ceremonial kisses as there were not.

I also find it interesting that the example of the Queen was used. (Note that the author did not cite said ‘portentous authority’.) The Queen was married some thirty years previous. Did that mean, then, that Victoria’s example was only just catching on if the question was still being raised in 1873? Neither was Victoria the prude we like to think her. Her marriage was as much a marriage of state as it was romance. Also they were neither of them showy people when it came to their own sentiments. It’s also noted that her uncle (Augustus, Duke of Sussex) kissed her. Not entirely sure he’s a reliable foundation upon which to set a pattern of appropriate social behavior, but… ok.

And what of the honeymoon? Well, literature is simply bursting with examples of these post-wedding conjugal trips, are they not? Er…maybe not. Once again, turning to Jennifer Phegley, she cites a rather cynical work entitled, How to Be Happy Though Married.

You take … a man and a woman, who in nine cases out of ten know very little about each other (though they generally fancy they do), you cut off the woman from all her female friends, you deprive the man of his ordinary business and ordinary pleasures, and you condemn this unhappy pair to spend a month of enforced seclusion in each other’s society. If they marry in the summer and start on tour the man is oppressed with the plethora of sight-seeing while the lady, as often as not, becomes seriously ill from fatigue and excitement.

Not a very pretty picture, is it? And it is not so difficult for me to imagine what it was like for a very innocent wife to be suddenly educated in the ways of married life. For the innocent, I imagine it was rather a shock. For the not so innocent, it might actually be traumatic, particularly if the man is inexperienced with inexperienced women, or inexperienced himself, or not quite certain how to merge his carnal impulses, heretofore deemed evil, with those of wholesome family life.

Yes, the Victorians were complicated. Roll your eyes if you will, but I relate to them, and I admire them in my way.

But here, perhaps, is where it might be best to take the Queen’s example, after all. She may not have taken much of a wedding holiday, but she made the most of her time. From what we understand of her now, related in Gillian Gill’s gripping We Two, she was no shrinking violet when it came to matters of conjugal romance. In fact she might very well have taken the lead. At least we understand, from trustworthy accounts, and by the number of children they had (which she would rather not have had) they had a very healthy love life.

But here, perhaps, is where it might be best to take the Queen’s example, after all. She may not have taken much of a wedding holiday, but she made the most of her time. From what we understand of her now, related in Gillian Gill’s gripping We Two, she was no shrinking violet when it came to matters of conjugal romance. In fact she might very well have taken the lead. At least we understand, from trustworthy accounts, and by the number of children they had (which she would rather not have had) they had a very healthy love life.

Personally speaking, I like to think that the general silence on the subject was out of respect of the union and not because they were all fumbling around in their bed clothes.

But then I’m an idealist.

So, what do I do when there is such a lack of reliable information to draw from? How do I write these weddings and newlywed scenes? All I can do is try to strike a balance between what I deem would be appropriate to the situation and what my modern day readers would want. And really . . . a wedding without a kiss? Are you kidding me?

June 5, 2012

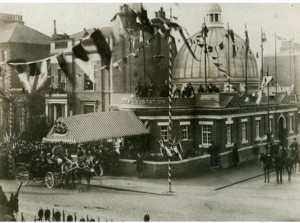

The Opening of the Central and South London Railroad (The Tube) – an excerpt

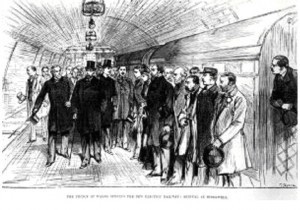

4 November 1890

In Lambeth the crowds were positively thronging. Was it the railway that drew so many out? Or was it the chance of seeing—and perhaps being seen by—the Prince of Wales? Abbie wondered, but did not much care. She didn’t like crowds, and she was nervous. But, with the crush of people from all walks of society—Dukes and Lords in high hats and long coats, their ladies in fur and silk, mingling alongside the city’s poor and dirty and hungry—she supposed she need not worry too much about her appearance. Lady Crawford had not yet noticed her altered attire. (Her heavy wool coat concealed her quite entirely, after all.) And, at the moment, she was wholly pre-occupied in the imminent arrival of Prince Edward.

In Lambeth the crowds were positively thronging. Was it the railway that drew so many out? Or was it the chance of seeing—and perhaps being seen by—the Prince of Wales? Abbie wondered, but did not much care. She didn’t like crowds, and she was nervous. But, with the crush of people from all walks of society—Dukes and Lords in high hats and long coats, their ladies in fur and silk, mingling alongside the city’s poor and dirty and hungry—she supposed she need not worry too much about her appearance. Lady Crawford had not yet noticed her altered attire. (Her heavy wool coat concealed her quite entirely, after all.) And, at the moment, she was wholly pre-occupied in the imminent arrival of Prince Edward.

“There he is now,” Abbie heard Lady Barnwell say to Lady Crawford. She looked in the direction where others, too, had begun to point and look. The crowd bellowed deafening cheers. And then she saw it. The Prince’s procession. She watched as it made its way from the station, from which the Prince had arrived on the train’s maiden journey, toward the depot.

The crowd filled in the path parted by the carriages and many followed the procession down Clapham Road. But it was here, at the station crossroads, where exhibits and festivities had been set up, that Abbie wished to remain. She wanted to see the train, to go into the tunnel and see for herself how it was meant to operate. Why so much to-doing if they were never going to see it?

“Are you coming?” Katherine said to her.

They were the first words she had spoken to her all day.

Mariana, who had been standing quietly beside her, preoccupied with the crowd and the excitement, took hold of her arm and followed, as David and Katherine led them onward.

“We will be too late to get a seat, if you we do not hurry,” Katherine added over her shoulder.

David said nothing. He did not even acknowledge Abbie as he fell in line with his family. Had Katherine told him, then? It would not take much, she ventured, to turn him against her once and for all. If only she had a chance to find out. But that chance was not now, as they followed in the wake of the Prince’s carriage.

In the little park of land before the City and South London depot, a great marquee had been set up, beautifully decorated in blues and ochres—and gold. And with intricately woven palampores to line the walls and to serve as doorways and curtains. It seemed to Abbie’s inexperienced eyes very like a maharaja’s pavilion, fit for a prince—which was its purpose, after all.

Abbie’s party, the Crawfords and Barnwells, were the last to be admitted, and their table was situated very near the back, the farthest from the Prince’s view. Or would be, when he arrived.

Prince’s view. Or would be, when he arrived.

Sir Nicholas and Lord Barnwell excused themselves to speak with some acquaintances, while the rest of their party took their seats and waited for the Prince to arrive and for the meal to begin. Though Abbie was hungry, she was more conscious of the opportunity being missed. Would they not see the train, nor the station, at all? And as Lady Barnwell and Lady Crawford examined the room—the other guests, what they wore, who they were with—Abbie dared to ask the question.

It went unheard as the elder ladies chattered and gossiped, and as Katherine sat silent and cross. David, too, was too preoccupied to hear her, and James’ attention was wholly absorbed with Mariana.

“He has come,” Lady Crawford whispered to them all.

The crowd suddenly grew louder, then quieted again. The Prince entered and took his seat, looking around admiringly at the oriental décor, and remarking upon it.

At last the meal began.

Lady Crawford alternately prodded at her aspic and then at Abbie, urging her to sit straighter, to take smaller bites . . . not to eat that. No, not that. Perhaps a little . . . no. Until Abbie gave up the endeavour entirely.

Which inspired Lady Crawford to inquire: “Why do you not eat?”

“Perhaps she is nervous,” Lady Barnwell answered. “She has never been in the presence of royalty. She is not so used to it as we are.”

“As if we dine with the Queen once a fortnight.”

“Sarcasm does not become you, Katherine.” Lady Barnwell looked from her daughter to Abbie with a disapproving look.

Yes, Abbie was to blame for Katherine’s foul mood, and she was conscious of it. If she could fix the problem she would, but she knew no way, at present, of doing it.

“I wish I could say I thought your ward ready for this,” Lady Barnwell said now. “I regret to say I do not.”

Lady Crawford, too, examined Abbie. She had no doubts. Or did she? Her eyes narrowed as she looked her up and down.

“Unbutton your cloak, Arabella. I want to see your dress.”

“It is a little cold in here. I would really rather—”

“Unbutton it, I say,” Lady Crawford demanded as Lady Barnwell tsked and frowned.

Reluctantly, Abbie obeyed.

“That is not the dress I bought you, and it is certainly not the one you were meant to pick up from the dressmaker.”

“No, ma’am,” Abbie answered. “I’m afraid it’s not.”

“May I ask why not?”

“The truth is, ma’am, I did not feel it quite right to adopt a manner of dress so very different from what my sister would wear on this or any occasion. She remains in mourning. So must I show the proper respect for the father I dearly miss.”

“Well,” Lady Barnwell said and sat straighter in her chair. “I do not envy you the work you have undertaken, Margaret.”

“Do you know, Arabella,” Lady Crawford said at last and laid her wadded napkin upon the table, “sometimes I wonder if you are not a little ungrateful.”

“I am sorry, ma’am.”

“Perhaps if you insist on presuming to decide what is best for you on such occasions, the bill might come out of your allowance. Do you have any idea what I paid to have that dress ready on time?”

“Forgive me, ma’am, but I’d hardly dare presume to any figures. And I’d certainly never consider doing it at the table.” It was daring, but it was out before she’d given the words the thought they deserved.

“Oh, dear!” Lady Barnwell said and fanned herself as her friend turned a violent shade of red.

From the corner of her eye, she saw Katherine hide a smile in her napkin and look away.

“You are right. That is a conversation for another time. But I will take this opportunity to express my displeasure at finding Sarah has gone, as well. Is this, too, your doing?”

“No. It’s mine,” James answered for her.

“Yours?” Ruskin demanded.

“It turns out the position was quite beyond her. I felt it necessary to let her go.”

“It turns out the position was quite beyond her. I felt it necessary to let her go.”

“Let her go? You go hiring and firing at your own pleasure, James, without a thought that it isn’t your place. How dare you do it without consulting me!”

“I’ve not done any hiring. Who said I’d hired anyone?”

“You know very well what you’ve done. What I’d like to know is why you thought it your place to do it.”

“Is that an answer you’d like to have now, dear brother? Because, to be quite honest, you figured into the decision. Shall I explain how?”

Ruskin turned a little pale, but said nothing. Nor was he given much opportunity to do it.

“This is not the place for this,” Lady Crawford very nearly hissed. “Needless to say we are all very disappointed in you, Arabella. Very disappointed, indeed.”

“Well I’m not disappointed,” James said to Mariana. “Are you, Miss Gray? Or is that Holyoak. I’m simply rotten with names.”

“James, please,” Mariana said and stabbed broodingly at her aspic.

Lady Barnwell tsked again in Abbie’s direction. Lady Crawford lifted her chin and looked away from the table, assessing, or so Abbie supposed, the likelihood that their little scene had been witnessed by any of their neighbours, or, God forbid, the Prince himself. No one, it seemed, from the moment they had entered until now, had taken any notice of them at all.

Abbie’s gaze shifted from Lady Crawford to pass over those who sat about the table. David had not eaten, but was sipping idly at his glass. James was pouring himself a second and offering to Mariana who refused. And Ruskin had forgotten his meal entirely and was simply staring at Abbie with what appeared to be a strange combination of anxious frustration. She turned from him. Her dress was a trifling matter, and she had no doubt he thought so, too. His displeasure was simply for her going against his mother’s wishes. Or was it more than that, after all? He seemed, at the moment, a little afraid of her.

Sir Nicholas and Lord Barnwell returned, still speaking among themselves, and it was not until they were seated that they realized that something at the table was amiss.

“What is this?” Sir Nicholas asked, looking from one dour face to another.

“After all the trouble we’ve gone to,” Lady Crawford said and waved a hand in Abbie’s direction. “Just look at her! After all the care we’ve taken to see she is at her best, and to come all this way to see . . .”

“To see a train,” Abbie reminded them, and tried to sound respectful.

“Which is precisely why the Prince of Wales is here,” Sir Nicholas added. “You did not think he came especially to see us, my dear?”

“No, of course not. But it was an opportunity for Arabella to be seen by him, and if he should pay her any especial attention, well her success would be guaranteed.”

“If you counted on so much, my dear lady, then it’s no wonder you are disappointed. I’m not sure it’s fair to lay the blame of the Prince’s preoccupation at Arrabella’s door. And as for the train,” he said addressing Abbie now, “there’ll be time to see it afterward.”

“But the crowds,” Lady Crawford said in objection.

“You do know it’s open to all,” added Lady Barnwell. “And underground, too. Must we, really?”

“For heaven’s sake,” David said and arose.

“Where are you going?” his mother asked of him.

“It’s close in here. I want some air.”

“You will miss the speeches.”

“I really do not care. Excuse me.”

Sir Nicholas cleared his throat and gave Ruskin an awkward glance. Abbie expected him to be angry with his son’s unwillingness to comply. Wasn’t he here to mix and mingle as well? Sir Nicholas, however, did not seem to mind at all that David would much rather not remain.

“Perhaps if you were to take Arabella with you,” he said to his son. “You might go now, before the crowds converge once more . . . ?”

David stopped, looked to Abbie, and then to Katherine. Then to his father, as if he were uncertain this was a burden he was prepared to bear.

“But, Nicholas,” Lady Crawford said, clearly disappointed by this change of plans. “Think of the opportunities he will miss, that they must all miss, if they quit the luncheon now.”

“It isn’t certain they’ll miss anything at all, my dear lady,” he said to his wife. “And if Miss Gray wishes to acquaint herself with this rail project,” he added with a pointed look in David’s direction, “then perhaps there is no better time to do it, when the crowds are occupied here and we are busy with our meal.”

“Oh . . . . very well,” Lady Crawford said at last, and in a pitch that was almost a whine.

Ruskin stood. “I suppose I might as well go with them.”

“I want you here, Ruskin,” his father said.

Ruskin sat again, picked his napkin up, and shook it out as if it had caused him some offence.

“Miss Gray,” David said, addressing her very respectfully. He turned then to her sister, “Miss Mariana. If you would care to accompany me, it would be my pleasure . . .”

Abbie arose, and Mariana as well. And so, necessarily, did all the gentlemen.

“You too, James?” Lady Crawford asked of her youngest son as he moved to follow them.

Abbie did not stop to wait for the answer, and neither was it given by James, but by his father.

“Let him go.”

Once more outside, Abbie took a steadying breath and let it out slowly. She took her sister’s arm and waited for David to lead the way, but he was  looking over her shoulder in the direction of the tent door. She turned to see the curtain part again.

looking over her shoulder in the direction of the tent door. She turned to see the curtain part again.

“Wait. I’m coming,” Katherine said as she joined them.

David took her hand and kissed her on the temple. Surely it meant a great deal to him to be able to share this with her.

“Shall we, then?” he said, and at last led the way.

Abbie and Mariana followed, but James was not to be left behind.

“You don’t really mean to make me walk by myself, do you?”

“Of course not,” Abbie said and made room for him between them.

“Are you really such a child, Mr. Crawford?” Mariana asked him.

“Who’s to say I may not have the opportunity to play the gallant hero today?”

“Who indeed?” Mariana said, and though she tried to stifle the smile that followed this, she was unsuccessful. “It’s something we would all like to see, I’m sure.”

“None more so than myself,” his brother said and walked on.

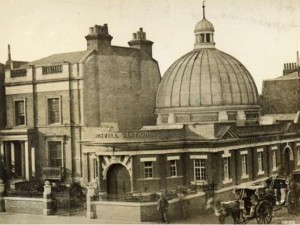

Abbie followed behind David and Katherine, who did not talk, and beside James and Mariana who did. After the din and commotion of the luncheon, she was almost grateful for a moment of peace. It did not last long. Soon enough they were back amidst the throng of the festivities, and in a moment or two more, they were entering the domed station.

The tunnel, once they arrived there via a hydraulic lift, was not quite the dark and foreboding place Abbie had expected. It was brightly lit by both gas and electricity, and the walls, the vaulted ceiling, too, were tiled in white, which shone and reflected and made the tunnel seem almost comfortable.

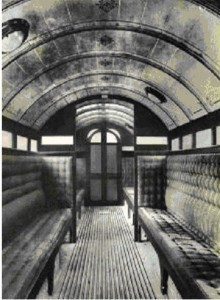

The train sat on one side of the platform, and an attendant, by way of opening the gate, encouraged them to board. David handed Katherine up, then turned to offer the same assistance to Abbie, who hesitated a moment before giving David her hand. His attentiveness seemed to her a trifle forced. He did not smile, would hardly meet her gaze. But he was being polite. Perhaps that was the best she could hope for under the circumstances. She only wished she knew just what those circumstances were. Was there a way to find out?

Once inside, they examined the car—a single compartment—in close detail. The walls and doors of gleaming wood, the vaulted, whitewashed ceiling. The high backed and comfortable benches, one on each side of the long car, and the narrow row of windows just above the seats’ backs. Through these there wasn’t much to see. The train sat stationary today, allowing for a view of the platform without. Travelling through the tunnels, however, would be quite dark. Still, they offered a sort of optimism that Abbie found comforting. In the reflection she caught David’s gaze, which altered its direction the moment her eyes met his.

David looked to Katherine, who was apparently not so pleased by the spectacle as was he.

“I can’t imagine who would want to ride on such a narrow, cramped thing,” she said. “Scores of people all in one car, trapped together underground, and with no way of knowing just who you might be sitting next to. It could be a lunatic or a murderer for all you know.” And she rubbed her fingers together as if she’d already acquired so much unwanted human filth. She turned and exited the car.

“I too find it rather cramped and close,” Mariana said, breaking the awkward silence. “Do you mind, Abbie, if I wait for you on the platform?”

“Not at all,” she said and watched as James accompanied her sister and Katherine off the train.

Perhaps Abbie ought to follow, but she did wish for a moment more. To see the train, yes. But to speak with David if she could manage it.

“It is not steam, I think,” she said, and was truly curious to know. “Not down so far beneath the surface.”

“No,” he answered. “It was meant to be run by cable, but they at last decided on electricity. It’s the first major railway to use it.”

“I venture it won’t be the last.”

“No,” he said and smiled, apparently encouraged. “There are others being built as we speak. In America, and on the Continent.”

“It’s a shame we can’t actually travel in them today. Do they not begin running right away?”

“It won’t open to the public for another six weeks.”

“Six weeks? Won’t we have returned to Holdaway by then?”

“I believe so.”

“How very disappointing.”

There was silence, and then it was broken as they both spoke at once.

“Look, I’m sorry about—” David began, but stopped upon realising Abbie had spoken as well.

“I apologise for the—”

They were both silent again. It was David who spoke first. “My mother likes to make a great matter out of small things. I hope you will not let her upset you.”

“It is difficult to avoid, it seems. But you did advise me against doing that which I did not wish to do.”

“I did. And I meant it. We’re all a little highly strung just now. It isn’t your fault.”

“Are you certain of that?”

He looked at her a moment, and looked away, examining the carriage once more. But the car was not large, and all there was to see had been seen already.

“Katherine is unhappy. That at least is my fault.”

“Perhaps,” he answered.

“Has she told you what it is over, our . . . disagreement?”

“No,” David answered with a fleeting smile and an even more fleeting glance in her direction.

“She will, of course. She must.”

“I’ve forbidden her from speaking of it—to me, or to anyone.”

“Have you?” Abbie asked him and hesitated to take hope. “But why?”

Neither did he answer this.

“If I should cause embarrassment or dishonour . . .”

“The dishonour’s been done already.”

“Because I’m here?”

“Stop that, will you? There is no shame in our having adopted you as our special cause. If that is what we choose to do, whose business is it but our own? But if you truly believe you are not fit to be among us, you will, whether you intend to do it or not, convince others to believe it, too. I do not know what this great controversy is between you and Katherine. If you wish to tell me I’ll be happy to hear it. If not then I’ll respect your wish for privacy. But if you fear dishonour, truly, I have to tell you, I think it’s just as likely to come as a consequence of encouraging you to feel obligated to us for that which you had no choice but to accept.”

“But I thought I was an avaricious grasper. Were those not your words?”

David removed his hat and rubbed at his forehead.

“Forgive me if I find you puzzling and unpredictable. You are certainly inconsistent.”

He nodded his acknowledgement of this. She took the opportunity of the silence to contemplate all he had said.

“Is there a price?” she asked him at last. “Is that what you are trying to tell me?”

“Is there some horrid secret that will put all my family’s plans for you at risk? Is that what you are trying to tell me?”

Neither question could or would be answered, and so silence ensued once more.

“Look,” David said, coming to stand very near her, “I cannot say I do not care what comes of all of this. I simply care for different reasons. Make your choice. Decide what you would do. Take no one’s happiness into account but your own.”

“You would encourage me to be selfish?”

“I have a feeling it’s not something you are used to doing. Of the average person I would hesitate to suggest any such thing. Of you, I think it’s precisely what you need most to consider.”

“And if it all blows up in your faces?”

“Then it is the risk we took in having you.”

“It is hardly a risk you chose to take.”

“I am choosing it now.”

She looked at him, uncertain what to say, or even to believe. He appeared perfectly and soberly sincere.

“We should go,” he said.

She stopped him with a hand on his arm. “Thank you.”

He only shook his head in answer.

“This train,” she said, stopping him again, “it means a great deal to you, doesn’t it?”

He smiled briefly, even sadly. “If I am to fulfil my obligation, I am to encourage you to do the same.”

“I do already, but why should it matter if I—”

She was interrupted by the opening of the door. James stepped inside. “We have company,” he said, looking only, and very intently, at David.

David looked at his brother for a moment, apparently puzzled.

“It seems there are some people we just keep bumping into,” James said as if it should offer some clarification.

Clearly it did, for David immediately followed after James, leading Abbie by the elbow and then handing her down to the platform once more.

“Shall we go, then?” James asked as they joined the others, and in a manner entirely different from the concerned one Abbie had just witnessed. He was perfectly jolly now.

In the lift, David stood very near his brother. “What is he doing here?”

“I’m not quite certain,” James answered. “Not yet, at any rate.

“Who?” Mariana asked. “Tell me who it is?”

“James Benderby. I’ve seen him hanging about your neighbourhood. Is there any way he can have known we’d be here today?”

“Oh no,” was all Abbie could think to say, and felt her sister take a tight hold of her arm.

“Of course, it’s possible,” was Mariana’s answer.

“Who is this man?” Katherine asked.

“He was one of our labourers.”

“Was? But no more?”

“Precisely.”

“And you do not know what he wants?”

“Well,” James said, but haltingly. “I suppose there is one simple answer.”

“Which is?”

They had reached the surface now, and the opening of the door released James from any obligation to answer. Likely he would not have done it anyway.