V.R. Christensen's Blog, page 6

March 4, 2013

An Announcement…

…or two.

Announcement the first!

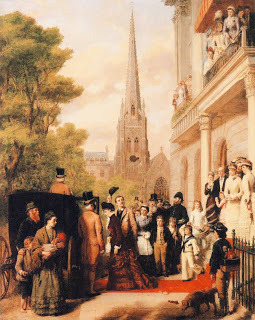

The first of my big, BIG, BIG announcements, is that I am, AT LAST, buying a house! It’s a lovely Queen Anne Victorian, in the historic district where I live, and I’ll be blogging about it! So if you are an enthusiast of old houses, or of Victorian history, make sure you subscribe, because this is going to be FUN! (Our last house was a 1918 Colonial Revival. If you’d like to see pictures of that project, please click here.)

And of course I cannot forget…

Cry of the Peacock comes out in one month!

Are you excited? I’m excited! I’ve worked for a really long time on this book (like nine years!) and there’s never been a better time to release it, what with the hoopla over Downton Abbey and all. It’s set in 1890, around the time of the opening of the London Tube, and it’s a great love story, fashioned, in a sense, after Pride and Prejudice and Middlemarch. What has Peacock in common with Downton Abbey? Well, it’s set on a vast English estate, which is being, and has been, mismanaged. It’s about the rise of a reluctant hero (or in this case heroin) who is being groomed to inherit, though she’s not sure she wants to. Neither does she wish to be set up with the snobbish, aristocratic heir. But has she a choice?

Well…maybe.

Cry of the Peacock will be available in Kindle and paperback April 4, 2013.

(And in hardcover as well shortly following.)

October 30, 2012

Adelaide’s Tale

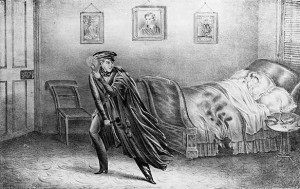

Some called them nightmares. Adelaide called them visions, scenes from past episodes in the lives of those whom she met in her work. It was not Arthur Tremonton who had scared her off, but the house and the memories it held.

Some called them nightmares. Adelaide called them visions, scenes from past episodes in the lives of those whom she met in her work. It was not Arthur Tremonton who had scared her off, but the house and the memories it held.

She had come to call upon Mr. Tremonton, she and Rebecca. They had come as emissaries of the Sister’s Benevolent Society for the Relief and Succour of the Blind and Otherwise afflicted. Mr. Tremonton was blind. Adelaide Hilton was otherwise afflicted.

They called her mute, but that was not her malady, truly. She could speak. She simply chose not to. There was too much to take in on any given day to have the presence of mind to attend to conversation besides. Every house had its story, every poor soul their miseries. It was to these Adelaide focussed her attention, the memories swirling about those who had fostered them like ephemeral ghosts, rendering the present a mere blur in contrast. Such was certainly the case at Tremonton Manor. Her relief, therefore, upon being dismissed from Mr. Tremonton’s presence, was understandably great.

Standing, alone, in the corridor outside the upstairs receiving room, Adelaide took a moment to calm her nerves. It was a curious house, with its receiving and living rooms all contained on the second floor, and cordoned off in one remote wing. These were Mr. Tremonton’s apartments, and he never ventured from them, for he had been assigned these quarters from childhood. Away from danger. Away from those who might see him and wonder at him. Away from his father who had been ashamed of him.

The house outside of Mr. Tremonton’s rooms was impressively quiet. The servants moved about in stockinged feet, to spare their master the noise. It was all the more curious to Adelaide, then, that he should welcome the ticking of so many clocks. Why was it that the sound of marking time only added to the silence, rather than relieving it? Did it make one aware that time was passing by, without it’s ever having been taken advantage of? The off rhythm of it, like a metronome gone mad, seemed to imply a sort of madness about the house, a busy-ness that was not seen but could perhaps be sensed. At least she could sense it.

Another noise drew her attention now, toward the far end of the corridor. It was a ticking—or a tapping—rhythmic in its way, but like no clock. It started loudly and grew softer. It started slowly and grew faster. Like a hammer on a spring. Tap . . . . . tap . . . . tap . . . tap. Tap, tap, tap, tap.

The corridor was very long, and very dark, papered in aging greens and browns. There was little light, for Mr. Tremonton had no need of it. The servants, of course, did, and so were allowed their minimum. But only that and no more.

That tapping had stopped now. A different sound had replaced it. The squeak of a door. The soft padding of footsteps that grew louder. An outline began to form in the darkness. A silhouette of a small boy. He did not look at her, but through her, beyond her. He was aware of her. Of that she had no doubt. But he could not see her. Those eyes, so pale, saw nothing. He turned from her and walked back the way he had come, but before entering once more that cloaking darkness, he turned back, and with a wave of his hand, he beckoned her to follow him.

The corridor led more deeply into the house than the candlelight provided for. Adelaide could make little out besides the occasional glint of a gilt frame on the wall, the image within rendered indiscernible—save one, that of St. Michael—by the near darkness. She stood before it a moment, conscious of the retreating figure and her call to follow him. She fingered the necklace about her neck, for it bore the same image, and, besides, a promise to protect her, to grant her courage. Apart from these shadowed canvases, the corridor was interrupted by the occasional doorway, little more than a hole in the wall. Little less, too, for most of the doors stood open, revealing nothing within. Only gaping emptiness.

At last they reached the end of the corridor. The boy’s footsteps were suddenly silenced, or muffled perhaps. He was ahead of her still, but on the other side of the door. This one was closed. She tried the knob and the door opened silently on its hinges. Adelaide blinked in the sudden flood of light as it poured in through the uncovered windows. They were not open, and yet there was a breeze, strong enough to sweep through the room, slamming the door shut behind her. She jumped, but all was once more still.

She turned to examine the room and observed that a fire burned in the hearth, and before it, sitting on the floor, was a woman, into whose arms the boy ran.

“Shall we play a game?” she said, to which he nodded in answer. She handed him a ball. He held it in his hands, felt the smoothness of it, then, with an impish smile, he threw it onto the floor.

Tap . . . . . tap . . . . tap . . . tap. Tap, tap, tap, tap.

Again and again they played this game, the boy laughing rapturously, the woman taking great joy in her son’s glee.

Like a thunder clap the door shut again. When had it opened? A man stood before it. He looked not unlike Mr. Tremonton, but those were no blind eyes that looked upon the pair.

“What in the name of all that is holy is this infernal racket about? Can a man have no peace in his own house? Cannot you keep him quiet?”

“I’m sorry. Don’t be angry. I will do better. No! Don’t take him!”

Without a word he snatched the boy up with one hand and turned to quit the room again.

“No!” she said, scrambling to her feet. “Don’t take him! Be kind to your child, Robert. Be kind to your poor, blind, child!”

He stopped and turned back, fury apparent in his look and in his tone. “No child of mine would have been born blind. This is your doing! This is your punishment for deceiving me.”

“Deceiving you? How can you say such a thing? Of course he is yours. You were proud of him once.”

“I know better now. And I know you better, too!” And he carried the boy from the room and from his mother, locking the door behind him.

Adelaide ran to it and tried the knob, though she knew already that the effort would prove vain. The knob, however, turned. The door opened, and she entered, once more, the unlit corridor. There she stood, trying to listen beyond the wailing and pleading of the woman on the other side of the door. Trying to focus, if she could, on the sounds ahead of her. And yet his pounding footsteps, the boys’ wails, and the man’s warnings to be quiet, echoed and reverberated throughout the house, seeming to come from everywhere at once.

In and out of unfamiliar rooms she darted. She was lost now. The corridor had turned and she had somehow ended up in one of the bedrooms. Out of this again she walked, nearly ran, but only left that one to enter another. They were empty, dirty, dark cobwebs hung from the ceilings and from the bed curtains. She stopped to catch her breath, and to rub the effigy of St. Michael between her fingers. For protection. For guidance. Show me what I have come to learn, she said in silent prayer.

Feeling a little more courage, she tried the next door, and stopped to find that she had entered the room of a woman very newly delivered of a child, the same woman Adelaide had a moment ago left. The boy was with her. She was speaking to him, telling him of his newly born brother. He knelt beside the child, listening to the cooing and gurgling of the babe, a proud look upon his face. The woman saw her and smiled, and then turned her face away, her eyes closed and resting.

Adelaide approached him, and kneeling down beside him, might have asked him if he was well? If he had escaped his father unharmed? But she didn’t. The words, as usual, would not come. It did not seem the right time. As if months had passed since the episode so recently witnessed. The mother’s gaze fell once more upon her boys, tears streaming down her face. Apparently of joy. Apparently of something else as well.

That something else hardened into fear and anxiety as a man entered the room. It was the same as before. The child’s father. Adelaide drew the boy behind her and did her best to shield the child in the basket as well. The man approached but seemed to take no notice of Adelaide. He could not see her, it seemed, as the mother could. He saw the children, however. He gave the baby a cursory glance and then turned his attention upon his wife.

“The doctor says this one, too, is blind. Do you think I am such a fool that I do not know what is going on? I have seen you, you know! I have seen you with Humphrey. I’ve seen you walking together. And what else?”

“I have walked with him, yes. He has been a true friend me. And to Arthur as well.”

“And nothing more? You won’t admit it, I know. But at least do me the honour of not attempting to deny it.”

“I have learned already that there is little point trying to dissuade you from believing what you wish to believe.”

“You believe I want a harlot for a wife?”

“I believe you’d rather believe me untrue to you than that you might be capable of having a child that is not as perfect as you deem yourself to be.”

He advanced upon her and was only prevented from striking her by the interference of the doctor, who dragged him outside the room and attempted to reason with him. His words could not be heard. Mr. Tremonton’s however, could.

“I will not have it, man! I will not have that trolloping woman in my house, nor her bastard of a child!”

Murmuring, mumbling, low voices indiscernible.

“A lunatic’s asylum, yes. . . . I will pay you any amount. Just see that it’s done. And as soon as it can be managed. A quiet place beyond the public eye, you understand. . . . Not in London, no. . . . . Yes, that will do. . . . How will I explain their absence? Well, if the mother was known to have died in childbirth . . . . No, that doesn’t explain away Arthur, does it?. . . . Yes, fine, he’ll remain, though I’m loath to keep him. He can remain in the rooms he inhabited with his mother. A nurse, yes, whatever is required, only he must stay out of my way. And he must be kept quiet. . . . You’ll see to it? I’ll prepare her. It won’t take much to convince them. She’s half mad as it is, upon my honour.”

Adelaide had heard quite enough. If it took every last bit of strength and will, she would tell this man just what she thought of him. She opened the door to find all was darkness and still. There was no one. Nothing. She turned back to the room to find it another entirely. There was a man, this time, lying in the bed. He sat up and looked at her.

“Evelyn? Is that you?”

Adelaide stood stock still.

“Evelyn, my dear? Forgive me, won’t you? I have not been the husband to you I should have been. I have not been the father . . . I will do better. Come to me?”

Of course she did not answer this, but slowly backed out of the room, shutting the door behind her. The door, however, was suddenly snatched from her hand and flew open. Robert Tremonton stood her in his bedclothes.

“Evelyn?” he said. He took a step toward her and she moved out of his way. He did not follow her however, nor did he seem any longer to see her. Slowly, as if still in slumber, he directed his course toward the room at the end of the corridor. The one she had first been led to by the boy. He unlocked the door and entered.

“Robert?” his wife said with a voice heavy with sleep. “What are you doing? Are you sleepwalking again? Robert wake up!”

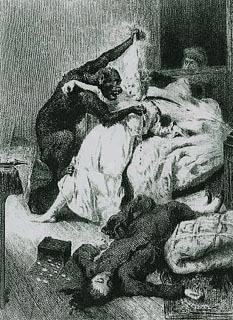

Adelaide ran to the door and peered inside. There was muffled screaming, thrashing about on the bed. Robert had his wife pinned beneath him, making the most of her in her vulnerability. The boy cowered, his hands clapped over his ears, hiding beneath the settee that sat at the end of the bed.

The scene was so horrible. A man was never truly known who was not known by his dreams. As a somnambulist he lived them, and wreaked the atrocities only imaginable by his withered soul upon those with whom he shared his house. Adelaide could take no more. She found a crystal vase on the mantelpiece, filled with wilted aster. And the last remnants of the stale and putrid water in which they had once been placed. With a great heave she threw the vase, smashing it against Robert Tremonton’s head. The vase flew from her hands, it passed through Tremonton’s head, through his wife’s, through the bed and the floor beneath. It sent the whole scene reeling like an oar through water, like a carriage through fog, breaking up all that was solid and sending it swirling about her. Glass shattered in all directions. Was it the vase? A mirror? Many mirrors? Or was it the whole world collapsing down in glittering shards. Adelaide ducked, covering her head and fell to the ground, dizzy, reeling, and feeling the million pricks of splintering glass as it flew through the air to pierce her.

And then all was still.

She opened her eyes. It was very dark. Not like night. Duller. Vaguer. In one direction, it grew darker still. In another, there was a faint light. She arose and followed in the direction of that light. The walls came into focus, narrow, closer than before. And papered in aging greens and browns. She was in the corridor again. This time she did not linger. She ran down it, down the stairs and into the entrance hall. There was no one to open the door for her, and so she tried it for herself. It would not budge. No effort could persuade it to give way. She stopped to catch her breath. Perhaps there was another way out. When her breathing had slowed, and her heart had calmed just a little, she turned and rested her back against the door.

In time she grew conscious of a squeaking noise. A steady squeaking as predictable as a metronome. It was not footsteps this time. It grew no louder or quieter with the advancing or retreating of its author. She crossed the hall to peer into the room opposite. A fire burned inside, and she was suddenly aware of just how cold she was. This is where she would wait for Rebecca. She must be done soon. From here she would be able to watch her descend the stairs. It was a convenient place. A warm place. And safe, she ventured. Thank St. Michael for that!

The squeaking began again.

Adelaide turned her attention from the fire’s flames to the room itself. She could make little out, however, for her eyes had adjusted to the firelight. She looked for a candle, and finding one, lit it in the fire before at last determined to search out the source of the sound. Was near, as if it were in this very room. Just before her . . . or . . . above her? She looked up and dropped her candle. The flame lit the carpet before her, licked at her shoes and her skirts, surrounding her. But she did not see it, did not, feel it. And, for the moment, she did not care.

Still the sound persisted. That faithful squeak, squeak, squeak. Faithful as a metronome. Certain as a pendulum on a clock.

From the dining room gasolier, a rope about her neck, swung Evelyn Tremonton.

Adelaide could not scream, could not call out. Not because she didn’t wish to, not because she didn’t need to, but because the power was not in her.

“There you are!” Rebecca stood in the doorway.

Adelaide ran to her, threw herself into her welcoming arms and waited.

“What is it?” Rebecca asked her.

What need was there to ask? Did not she see? And suddenly the question took on new meaning, a more important meaning. Adelaide looked up to see Rebecca’s face. There was no look of concern or alarm there. No fear. She turned back to the room. It was empty now, and lit by the thinly curtained window. There was no fire. There was no dangling woman. There was not even a gasolier. A hole, only, remained to mark that it had ever been there.

Would anything mark that Arthur Tremonton had ever been here? Or was he, too, a vision? No, he was real. That she knew. And whether or not he would leave any mark ever or at all would have to be answered by Rebecca and her efforts in his behalf. Adelaide would not be returning. Nothing would ever persuade her. She removed her necklace with its effigy of St. Michael and placed it in Rebecca’s hand.

Rebecca accepted it reluctantly. Perhaps she did not understand what need she had for protection. Perhaps she did not like to think that Rebecca should go without it. But it was a sacrifice she was willing to make if it meant never returning here. And by a combination of choice and circumstance, she never did.

[Adelaide's Tale is an alternative perspective written to complement the novella Blind.]

September 14, 2012

The Haunted House tour begins soon…

September 12, 2012

Haunted House Virtual Tour

Blind and Ungentle Sleep are going to be doing some travelling with some of their friends!

Come join us!

Haunted House Tour Running from mid-September to mid-October

Promoting ghost novellas Blind by V.R.Christensen and Ungentle Sleep by B.lloyd

Part One

15th September :

A quick visit to Hillburn House (Ungentle Sleep) with links to both Ungentle Sleep and Blind at : http://ljclayton.wordpress.com

17th September :

A mystery visit to a gothic residence with links to both novellas at :

http://someonewotwrites.blogspot.co.uk

20th September :

A quick and unsettling tour of Tremonton Manor, where the novella Blind is set, plus links, at http://ruth-barrett-spiritedwords.blogspot.com/

21st September:

Diary of a Ghost-Hunter, from 1785, in another mystery residence from gothic literature … with links to both novellas, at http://fromthebootheelcottonpatch.blogspot.com

22nd September:

Why was the Duke Saltimbocca enraged at dinner? Find out at our next trot around one of the better known locations from the past, as always with links to the two novellas, at : http://gwenperkins.wordpress.com

From the 23rd to 29th September, Ungentle Sleep will be hosted via Tourz de Codex on the following dates :

23rd September:

http://littlelibrarymuse.blogspot.com - Review, Guest Post

24th September:

http://jowu-timeispoisoned.blogspot.com – Character Interview

25th September:

http://janieraeldridge.blogspot.com - Author Interview

26th September:

http://drennanspitzer.com/ - Review, Guest Post (The Skene Manor in Whitehall, NY, allegedly the inspiration for Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House.)

27th September:

http://1morepageplease.wordpress.com - Review & Author Interview

28th September:

http://drpepperdiva.wordpress.com - Guest Post

29th September:

http://le-grande-codex.blogspot.com - Guest Post & Giveaway

Part Two of the Haunted House Tour will be from early to mid-October, and will include visits to Dark Media City plus Giveaways, a Spotlight on 4th October at http://passionforpages.blogspot.com and www.bewitchingbooktours.blogspot.com

Detailed schedule to be updated soon

August 24, 2012

Some good news and some bad

(Click on the image for US link. For UK link, click here.)

(Click on the image for US link. For UK link, click here.)

***Thanks to Free Kindle Books and Tips for helping me to spread the word about this weekend’s promotion!***

Now for the bad news.

Publication of Cry of the Peacock will be delayed. I know. I’m sad, too. But recent feedback from the editors has indicated it needs a little more work than I had realised. I’m also trying to prepare for another move, and so, in order to give the book the attention it needs, and which it deserves, Captive Press has agreed to defer publication until spring of 2013. I’ll keep you posted when I have a more specific date. Until then, take a peek at the newest excerpt, and watch the trailer once more.

August 15, 2012

Book review: Merits and Mercenaries

A Classic Companion by A Lady

Katherine grew naturally into a handsome, intelligent and truly generous young woman, drawing from her aunt’s strength of character—and her late uncle’s sorry lack of it.

And so begins Lady A~’s exquisitely written Austen-esque masterpiece, Merits and Mercenaries. It isn’t very often I’m completely absorbed in a book. So absorbed that I go to bed thinking about the story’s many layered conflict, and dreaming about the characters, planning and plotting in their behalf, trying to sort out in my head just where the story might go, and all the seemingly impossible obstacles that must be overcome to get it there. It was just that way for me as I read this wonderful book.

This was just a superbly written, cleverly concocted, shining example of what Historical Fiction ought be but rarely is. Here were no attempts to modernise the heroine, or even the conflicts of the story. So much of what motivated and concerned humanity two hundred years ago, motivates and concerns us today. On the other hand, here was no overwrought attempt to recreate Austen-esque literature. It was certainly recreated, but the product could hardly be called overwrought. The narrative was natural and flowing and the dialogue absolutely sparkling with wit and charm. The author never once talks over our heads, and when she fears a question may arise, she cleverly refers us to annotations kindly included in the back of the text. This is a welcome embrace to fellow fans of Jane Austen, and, too, of Literary Historical Fiction, as well.

I like complex plots; I yearn for them. I like big, thick books with rich characters that are engaging and compulsively followable. This book gave me both, but in a way I found cleverly deceptive. The conflict was simple. A young woman, Katherine, is taken to the country by her guardian aunt, in the hopes of presenting her with some new prospects for marriage. Of course Katherine is naive to her motivations and goes about her life, adjusting, albeit reluctantly, to the countryside. In Hampshire we are introduced to country society, among them potential friends, some worthy, others not so much. Here among them as well are one or two—or perhaps four—potential suitors. It isn’t a grand mystery for whom Katherine is intended, but the hero is engaged to another. And it’s an unbreakable commitment, assigned to him upon his father’s deathbed. What are two people in love to do? Save, of course, to resign themselves to their unhappy fates. But it isn’t the hero’s prior commitments alone that stand in the way of our dear Katherine’s happiness, for an intricate web of deceit and interference is slowly woven to ensure that Katherine does not prove an irresistible temptation to our would-be hero. For he simply must marry as he has been charged to do. Mustn’t he?

And so we are guided, led, drawn, through each and every page, as if the author were leading us on a long walk, on a warm spring day, on our very first journey through Holland Park, where some new bit of scenery, an unexpected but always pleasant surprise, awaits us at every turn. I look forward with great pleasure—with anticipation—for Lady A~’s next work.

To find out more about the author, please do visit her at:

And please, do get a copy of your own. You won’t regret it!

Merits and Mercenaries is available at these online retailers:

July 15, 2012

On Empathy and Research

I’m not a research historian. I’m sorry if I’ve disappointed you, or if that somehow belittles what I do. But I don’t believe in pretending to be what I’m not. What I am is honest. What I am is empathetic. Now and then, however, I get a little tired of being bombarded by bombastic pedants, who would belittle the work I do (or that my friends do) in order to make themselves look like experts. It happens more than I’d like. And frankly, I’m tired of it.

I’m not a research historian. I’m sorry if I’ve disappointed you, or if that somehow belittles what I do. But I don’t believe in pretending to be what I’m not. What I am is honest. What I am is empathetic. Now and then, however, I get a little tired of being bombarded by bombastic pedants, who would belittle the work I do (or that my friends do) in order to make themselves look like experts. It happens more than I’d like. And frankly, I’m tired of it.

I’ve been posting a lot of research pieces lately, not only on my blog, but in other places. I find such pieces very difficult to write. History is so complex and many layered, and fitting all the necessary details into a 1,000 word post, is often nigh to impossible. Drawing conclusions about those details, making judgments or ‘aspersions’ is…well, it’s dangerous. But it’s also, in my opinion, necessary. How does one learn anything useful or improving without making a judgment, of one kind or another, about it? You don’t. You can’t. For a research historian, perhaps this is right and proper. For a novelist, it’s wrong. And I’ll tell you why.

The fact of the matter is, there are different types of research, necessary for different purposes, and conducted by people who simply function differently and under different motivations. There’s nothing wrong with that. There’s never one way to do anything. What it comes down to is how we think, how our brains function, how we see the world, and what we wish to gain from studying the history of it. Another thing I think it comes down to, is an ability or inability to empathise with historical facts and figures. Because unlike Math or the Sciences, History’s facts and figures are, or rather were, people.

I’m also a sort of a hobbyist psychologist. That is, I study personalities. I find it useful in my writing, but more than that, it’s useful in my daily life. There are basically two cognitive functions, those being sensing and intuition. Those who rely on the sensing cognitive function are great at collecting data, remembering dates, names and places. Such data is easily gathered and stored in the memory of the sensing individual. What can be seen, touched, held, remembered, these matter most.

I’m not a sensing individual. I’m the other kind. The weird one few understand. I can gather data as well as anyone else. What I can’t do is remember it. My brain, as much as I’d like it to, just doesn’t work that way. What I can do, however, and I do it quite well, is it forms impressions of things, I see broad patterns and trends, I can understand, and reproduce, how it may have felt, to live in a certain period of history. I may not be 100% right. It may just be my interpretation. But my guess is as good as anyone’s. I’ve not met anyone yet who possessed a time machine.

What lately helped me to see that this difference in method comes down to individual ability and motivation was an article sent to me by another writer friend. The article is on how most criticism is based on a lack of ability to empathise. Seemingly it has little to do with research. To me it has a great deal to do with it. Do you welcome discussion about your topic of choice? Or do you feel challenged by anyone with a differing opinion? If you cannot see the other person’s point of view, does that not reflect an inability to empathise?

But what about casting judgment? Does my lamenting the wrong done to the Jew in Hitler’s Germany (and elsewhere) mean I have an inability to empathise? Or do I, in feeling sorrow for their plight, in feeling the weight of that tragedy, judge Hitler and his minions? I do both, of course. Hitler was an evil man. I have judged him. Now, to do justice to history, I must try to understand him, to try, if I can, to learn what made him into the monster he became.

I do understand the caution against making simple judgments about historical figures and events. There is nothing at all simple about history, because there is never anything simple about people. For me, it isn’t enough to simply learn about history. I want to learn from it. I want to delve deeper, to explore the hows and whys of it all. Dates and facts and names will get me so far. I want to go farther. Eventually I am going to make a judgment. I am going to ask myself if I would have behaved similarly in their shoes, and why or why not. I’m going to ask myself what prices we are still paying for the decisions made by the men and woman who came before me. How is life better? How is life worse?

We cast judgments. It’s what we do. The irony is that those judgments, historically speaking, are rarely about individuals. They are about the pitfalls of vice, or the rising and falling of civilisation. I wouldn’t dare cast a judgment on a husbandless mother in Victorian England, but I can look back on it and make judgments about the conditions that placed women in such desperate situations, or that would starve children and drive them to work, scampering up chimneys and working on the streets to bring home (if they had a home) enough to eat. Did they understand it then the way we understand it now? Possibly not. And so my job, then, is to try to stand in their shoes. To try, if I can, to look at it from every angle, from the gentleman’s wife who doesn’t want the dirty little beggar in her house, to the gentleman’s children who wonder what it’s like inside a chimney, or if the little fellow doesn’t want a bit of tea. Life was different then. It wasn’t so different as to remove human feeling.

But I’m not a historian. What I am is a novelist whose primary aim is to teach, and to do it in a setting that is as accurate as humanly possible. The problem is, history is, well, history. None of us has ever spent any actual time in the Regency or Georgian or Victorian eras. None of us really knows what it was like. What we can do is read as much as we can, try to immerse ourselves in the atmosphere of it, read biographies, and histories, and studies. Better than that, read letters and journals and other contemporary publications. And then put ourselves in the shoes of those who walked there. This requires passing judgement, presuming, if you will, upon history. But as a novelist, it’s the very best thing I can do for my books, and for my readers.

But I’m not a historian. What I am is a novelist whose primary aim is to teach, and to do it in a setting that is as accurate as humanly possible. The problem is, history is, well, history. None of us has ever spent any actual time in the Regency or Georgian or Victorian eras. None of us really knows what it was like. What we can do is read as much as we can, try to immerse ourselves in the atmosphere of it, read biographies, and histories, and studies. Better than that, read letters and journals and other contemporary publications. And then put ourselves in the shoes of those who walked there. This requires passing judgement, presuming, if you will, upon history. But as a novelist, it’s the very best thing I can do for my books, and for my readers.

Rightly or wrongly, it all comes down to empathy. Agreeing or disagreeing with another person’s research, unless the bare facts are just wrong, comes down to empathy, too. Can you see how they came to their conclusion? If you disagree, then why? Is it because you know more, and you are the expert and how dare anyone challenge you? Is it an inability to see where they came from? And do you care?

Personally, I find the world more interesting with different points of view. No one owns a monopoly on history. I know I don’t. And people aren’t afraid to remind me of the fact. I’m happy to discuss it, so long as you can do it in a friendly and respectful manner. If not. Move along. I’ve got some research to do.

July 9, 2012

The Mystery of Mary Rogers

Mary Rogers and her mother, Phoebe, arrived in New York in 1837. For the first few months of their residence, they lived with a gentleman named John Anderson, who owned a tobacconist shop. Anderson employed Mary and there she earned a sort of celebrity. She was universally considered a striking beauty and had many admirers, all of which, of course, were pleased to buy tobacco from Mr. Anderson. The hiring of attractive shopgirls was a common practice in Europe. It was still considered rather indecent in the US. Still, Mary needed the work, and Anderson paid her well to maintain her post safely behind the shop’s counter.

Mary Rogers and her mother, Phoebe, arrived in New York in 1837. For the first few months of their residence, they lived with a gentleman named John Anderson, who owned a tobacconist shop. Anderson employed Mary and there she earned a sort of celebrity. She was universally considered a striking beauty and had many admirers, all of which, of course, were pleased to buy tobacco from Mr. Anderson. The hiring of attractive shopgirls was a common practice in Europe. It was still considered rather indecent in the US. Still, Mary needed the work, and Anderson paid her well to maintain her post safely behind the shop’s counter.

In October of 1838, Mary disappeared. Her mother found a note on her dressing table which bid her “an affectionate and final farewell.” It was speculated that she had been disappointed in love. She had recently had a suitor, it was said, who had deserted her, and some believed she had gone with the intention of taking her own life. Others speculated she had eloped. A search party was organised, but Mary returned on her own, some say a few hours later, others claim it was a matter of weeks. The following day, the motivation of suicide was reported to have been a hoax, and that the letter had either never existed, or had been written by someone with an eye toward mischief. When exactly Mary returned, it is unknown, but it is known that it was a matter of a few weeks before she returned to work. Anderson, naturally, was quite worried for her. Some say he made a public plea for her to come home. His interest in the family, and the true nature of his relationship with them, is a point of interest to those who study the mystery today.

In time, talk of Mary’s disappearance and subsequent return quieted, and she continued her work at Anderson’s Tobacco Emporium. In 1839, having come into a little money, she and her mother purchased a boarding house and she left Anderson’s shop. Here Mary was once more beset with suitors, two of which being Alfred Crommelin, a polite gentleman with good manners and elegant bearing, and Daniel Payne, a cork cutter, who was known to be hot tempered and inclined to drink very heavily, even by the standards of the day. Both gentlemen were lodgers in the boarding house.

By June of 1841 Payne was recognised as Mary’s preferred suitor. Crommelin returned to the boarding house one evening to find Payne and Mary engaged in “unseemly intimacies”. He rebuked Payne for his ungentlemanly behavior and quit the house for good. Before going, he apologised to Mary for the step he was taking and begged her to remember him if she should everfind herself in trouble. And then he was gone.

In July Mary disappeared a second time.

According to reports, Mary arose before dawn on 25 July 1841, helped to prepare breakfast for her mother’s lodgers and attended her various morning chores. Shortly before ten o’clock she knocked at Payne’s room and she informed him, through the half open door, that she was going to visit her aunt, Mrs. Downing, who lived fifteen minutes away by omnibus. It was her plan to return in the early evening, and she wished for Payne to meet her so that he might escort her safely home.

A few days earlier, according to some reports, Mary had been persuaded by her mother to break off her engagement to Payne. That same day, Crommelin received a note asking him to call at the boarding house. When he arrived at his office, he found a second note, written on a chalk slate. Despite her summons, and the romantic intentions implied by the red rose she left in his keyhole, Crommelin did not go to the boarding house again.

Payne, on the day of Mary’s visit to her aunt, kept himself busy by visiting his brother, a market, a tavern then an eating house before going home to take a long nap. He arose in the evening and went to meet Mary, and only then realised the omnibus did not run on Sunday. An approaching storm soon drove him back home, where he decided Mary must spend the night at her aunt’s.

The following morning, Mrs. Rogers was in great anxiety, for Mary had not returned home. Payne was not yet worried, and so went to work, but when he returned at lunchtime, and finding Phoebe in an even more anxious state and Mary still not at home, he went then to the aunt’s house to discover that Mary had never arrived there. Nor had the aunt ever expected her. He posted an ad in the paper giving Mary’s full description, and then returned to the boarding house, where Mary’s mother was now in a state of lethargy.

On Tuesday, Payne went to a tavern on Duane Street, where Mary was said to have passed several hours, but upon arriving there he found the description did not match Mary’s at all. From there he went to the ferry launch at Barclay street which crossed the Hudson to Hoboken, where he asked several strangers, and stopped at a few homes along the way to find out if Mary had been seen there. He then wandered on toward Elysia Fields, where he continued to make inquiries

Crommelin was now aware of Mary’s disappearance, but took no action until Wednesday when he was shown the missing person’s report that Payne had put in the paper. He hurried to the boarding house, where he found Phoebe, glassy eyed and in a state of mourning, and Payne standing at her side. Crommelin, then began a search of his own, retracing the steps Payne had taken the day before, going to Hoboken, and then to Elysian Fields.

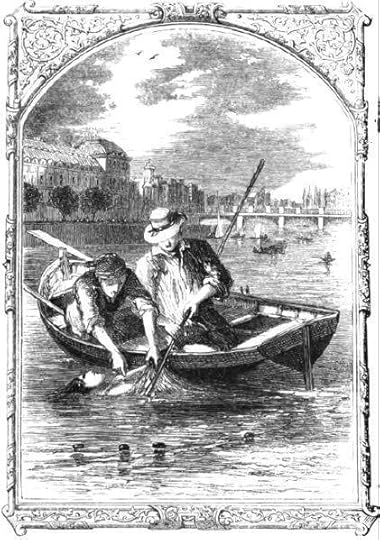

While he was searching Hoboken, a body was found floating in the river. Two men in a rowboat towed it to land and the body was pulled ashore.  Crommelin pushed his way through the crowd to see it. What he saw must have shocked him a great deal. He certainly could not have recognised her by her face. To identify her, he ripped open a portion of her sleeve and examined the hair on her arm. This, evidently providing ample proof, he declared it to be Mary Rogers, then crouched protectively over the body until the crowd dispersed and an official was called to the scene.

Crommelin pushed his way through the crowd to see it. What he saw must have shocked him a great deal. He certainly could not have recognised her by her face. To identify her, he ripped open a portion of her sleeve and examined the hair on her arm. This, evidently providing ample proof, he declared it to be Mary Rogers, then crouched protectively over the body until the crowd dispersed and an official was called to the scene.

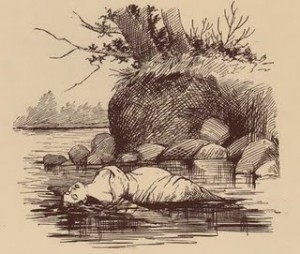

Dr. Richard H. Cook, the New Jersey coroner, was the first to arrive. It was a hot July day, and the condition of the remains threatened to deteriorate further as her body veritably consumed itself in the heat. When at last the justice of the peace appeared on the scene, the body was removed to a nearby building and the autopsy was performed. The face he examined was suffused with bruised blood. She had clearly been beaten, and there was no foam in her mouth or lungs. This was no drowning victim. On her neck, he observed deep bruising in the shape and approximate size of a man’s hand. As he examined the marks more closely, he found that a piece of lace was tied so tightly around her throat that it had embedded itself into her skin. He had not so much as seen it, but felt the knot which was situated just behind her ear. The undergarments of her clothes were found in disarray, and, upon closer examination, he found evidence of bruising and abrasions in the “feminine region”. He concluded she had been raped by no fewer than three assailants. Her arms had been positioned as if her wrists had been tied together, and the abrasions caused by the tethers seemed to indicate she had tried to raise her hands to her mouth. A loop of linen was found tied loosely about her neck, as if it had been used as a sort of gag. These strips had been torn from her own clothes, which matched precisely the description of those last seen upon Mary Rogers. What’s more, a foot wide strip of fabric had been torn from her petticoat and wrapped around the body to form a sort of hitch to aid in the carrying of the corpse. Her hat had been tied on her head with a sailor’s not, rather than the typical knot tied by a lady, suggesting it had been replaced by her assailant or someone connected with the crime, before her body was thrown in the river.

About the time the autopsy began, one of the men, H.G. Luther, who had pulled the body from the water, arrived at Mrs. Roger’s home to deliver the news. Payne was there, standing protectively by her side. They received the news with apparent indifference. Perhaps it was resignation. But the lack of emotion was curious to Luther. Even more curious, Payne took no action that night. It was still early. He might easily have gone to Hoboken. He might have hoped to add a second witness to the identification of the body. He might have gone with a hope of finding that Crommelin had been mistaken. He stayed at home with Mrs. Rogers.

In the time it took for the officials of New Jersey and New York to decide who would take responsibility for investigating the death of Mary Rogers, rumors and speculations began to fly from every direction. For a time it was believed Mary had fallen into the hands of one of the many and notorious gangs that frequented the Hoboken area. Others were certain it was one of her jilted lovers. Some felt it wasn’t Mary at all, supported by the belief that a body that was in the water for no more than three days could not have decomposed to such an extent, or even, for that matter, risen to the surface.

Of course Payne and Crommelin were suspects. Payne’s alibi, at least for the first few days of Mary’s disappearance, were solid. He had been with his brother, had frequented taverns and eating places, and witnesses could attest to his being there. Crommelin, too, was a suspect, but as he had been so outspoken and proactive in finding her, and then in discovering the killer, it seemed impossible it could be him.

And then, on the 25th of August, as two boys were hunting for sassafras bark in a thicket in the woods near Weehawken, some articles of clothing were found. Among them was a petticoat, an umbrella, a silk scarf and a handkerchief with M.R. embroidered upon it. The boys took the articles to their mother, the owner of a nearby tavern, who put them away, and then, a day later, took them to the police. Frederica Loss’s tavern was very near, and often frequented by those who visited, Elysian fields. Mrs. Loss, upon being questioned, remembered, if rather belatedly, that a young woman of Mary’s description had been seen at her establishment. She had been accompanied by a young man of ‘swarthy complexion’, and went on to describe Mary’s attire and appearance exactly. Mrs. Loss told police that a short time after the couple left, she heard screams issuing from the area of the thicket. She thought it was her son, whom she had sent out again, but he returned a short time later unharmed.

And then, on the 25th of August, as two boys were hunting for sassafras bark in a thicket in the woods near Weehawken, some articles of clothing were found. Among them was a petticoat, an umbrella, a silk scarf and a handkerchief with M.R. embroidered upon it. The boys took the articles to their mother, the owner of a nearby tavern, who put them away, and then, a day later, took them to the police. Frederica Loss’s tavern was very near, and often frequented by those who visited, Elysian fields. Mrs. Loss, upon being questioned, remembered, if rather belatedly, that a young woman of Mary’s description had been seen at her establishment. She had been accompanied by a young man of ‘swarthy complexion’, and went on to describe Mary’s attire and appearance exactly. Mrs. Loss told police that a short time after the couple left, she heard screams issuing from the area of the thicket. She thought it was her son, whom she had sent out again, but he returned a short time later unharmed.

The discovery of the ‘murder thicket’ raised as many questions as it answered, however. It was so close, and so overgrown, that a person could only enter it on hands and knees. There were many footprints about, the clothing found had been caught on brambles, had mildewed and been overgrown with grass. If the path to the tavern was so well travelled as to give Mrs. Loss a steady flow of customers from Elysian Fields, how was it possible the articles were never seen before? How was it possible, through the July and August rains, that the footprints still remained? Was it likely a man would attempt a murder so nearby the tavern, a mere 400 yards away?

It was suggested by some that Mrs. Loss had planted the articles there herself. The truth of this is impossible to know, but she certainly enjoyed a brisk business after the discovery, for there were many who came to get a glimpse of the place for themselves.

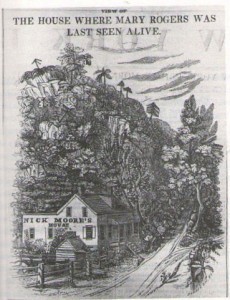

Payne was one of them, but he got no pleasure from viewing the scene. At ten o’clock on October 7, he arrived at a nearby tavern, where he ordered a drink and announced, “I’m the man that was promised to Mary Rogers. I’m a man in a great deal of trouble.” It seems he left the tavern and arrived at the thicket with a bottle of laudanum in hand. Upon entering the thicket, he drank it down and crushed the bottle against a rock. Two hours later he was found dead with a note in his pocket. “To the World—Here I am on the spot; God forgive me for my misfortune in my misspent time.” There was also a bundle of papers in his pocket. What they contained was never revealed. It is assumed by most, that they contained nothing of import. At the time, the silence of the investigators on the subject aroused a great deal of speculation.

Poe, eager for the same success he had experienced with The Murders in the Rue Morgue, found an opportunity to employ his deductive reasoning skills, or, as he preferred to call it, ratiocination. C. Auguste Dupin was called into action again, and this time, he bragged, would perform the feat of solving the mystery from his armchair and by using only the newspapers for his source. How accurately anyone can determine a true cause of a crime from newspapers is beyond me. Sensational journalism is not factual reporting by a long shot, as I mean to prove in an upcoming post. (Link to come.)

What Poe did manage to convince his readers of, was that the murderer had acted alone. Why else would he need the aid of the ‘hitch’ found tied around Marie’s waist. He also connected Mary’s first disappearance with her first, suggesting that the sailor with which she had meant to elope the first time, had returned from sea. He also went on to suggest that perhaps a falling out had occurred, and the romance ended, instead, in tragedy.

But that wasn’t the conclusion his readers received.

Poe’s manuscript was some 20,000 words in length, and so it was published in three parts. At this point two of the three had been published. The third promised to “indicate the assassin.” But it had not yet hit the presses when the New York Tribune published headlines that read “THE MARY ROGERS MYSTERY EXPLAINED.”

Indeed, new evidence had arisen that blew all of Poe’s theories out of the water. He revised the third part to sort of indicate he knew the solution all along. All it succeeded in doing was muddying the waters of his ‘ratiocinating’. He ends by telling his reader that Dupin has solved the mystery, that all will soon know it, but for the sake of justice and respect for the police, he will leave them to tell the tale. Years later he would take another stab at realligning his solution with that which was soon to be the commonly accepted one. He added passages and footnotes that, for the first time, showed a direct relation to Mary Rogers. He also added a caveat, that he might have been better prepared to solve the mystery had he been in New York, and not had to rely on the papers, a complete reversal of his earlier boastings of the skill of a detective who could solve a mystery from his armchair.

So what was the evidence that reduced Poe’s Marie Roget into inconclusive and muddled literary nonsense?

On November 1, 1842, Police arrived at Nick Moore’s Tavern in Weehawken to discover that Mrs. Loss had been accidentally shot by one of her sons, who was later heard to remark, “The great secret will come out.” What was that secret? For some time, it seemed, Mrs. Loss had been under the attention of the investigative police in connection with a famous abortionist named Madame Restell, whose services were advertised in huge, prepaid advertisements published on the back of every paper in town. Her money was not spent at the papers’ alone, but to the police as well, who arrested her on several occasions, but always released her again. Perhaps her habit of paying her $10,000 bail money in cash (and with an extra $1,000 as a tip) helped her some.

Though Madame Restell was somewhat protected by the police, she was considered an enemy to the people, and to society at large . Giving birth alone came with incredible risks. Add to that poisons, unctions of curious make, unsanitised instruments, the mortality rate was astounding. Mary’s body was not the first to be pulled from the Hudson river, merely the most famous. She had so far been lauded as a chaste, respectable maiden. What was she now? That Madame Restell was a millionaire with a brownstone mansion only attested to how sought after were her skills. Sad to think what combination of circumstances would have driven these women to seek her services.

But Madam Restell was rather expensive. Who did you go to if you could not afford her? Why she would refer you to some of the other foetocidal houses in the city, those who charged less and were less proficient in their trades.

The conclusion of Mary’s mystery was accepted by most. It provides a not quite tidy solution. Mary’s mother seemed to have known that when Mary left she was going to her death. It would explain her stoicism upon the news that Mary’s body had been found. She had gone to have an abortion. Had it been a success, she would have returned already. It explains why Mary went to Crommelin to begin with. It was said she went to him to exchange a boarder’s IOU for money. A sum of some fifty dollars. If Payne were the father, it might explain his apparent guilt at her death. It might explain why Crommelin was hesitant to help her. Perhaps she meant, by leaving the rose in the keyhole, that she mi ght marry him instead, were he to help her. Perhaps his not giving her the money was the reason she went to Mrs. Loss rather than Madame Restell.

ght marry him instead, were he to help her. Perhaps his not giving her the money was the reason she went to Mrs. Loss rather than Madame Restell.

But if this soon to be accepted solution provided answers to these questions, it left many more unanswered. If she had died at the hands of an abortionist, what need had they for a garote to strangle her? Why was she so violenty beaten and strangled? Was it to disguise what had really happened? Or was it a combination of the two? Had she gone to have the abortion? Had it been a success? Had she met Payne and refused to marry him. Had he killed her? Or had she died under Mrs. Loss’s roof after all? No one, it seems, will ever really know. They Mystery of Mary Rogers, remains, and will likely always remain, a mystery.

July 4, 2012

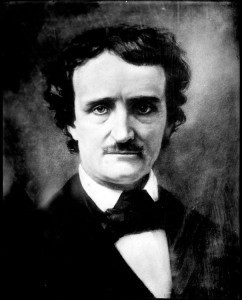

Edgar Allan Poe and the beginning of Crime Reporting (Stateside)

Over on Goodreads we’re having a discussion about Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin Mysteries. Some really interesting discussion has been going on there, and the question of the history of Crime reporting and detective novels came up. Last October, during my Poe-athon, I bought, but did not read, “The Beautiful Cigar Girl” by Daniel Stashower. As I’ve already read the Dupin Mysteries, I decided it was time to read “The Beautiful Cigar Girl”. This is one riveting book, and I highly recommend it if you are a fan of Poe or even of murder mystery and reporting.

Over on Goodreads we’re having a discussion about Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin Mysteries. Some really interesting discussion has been going on there, and the question of the history of Crime reporting and detective novels came up. Last October, during my Poe-athon, I bought, but did not read, “The Beautiful Cigar Girl” by Daniel Stashower. As I’ve already read the Dupin Mysteries, I decided it was time to read “The Beautiful Cigar Girl”. This is one riveting book, and I highly recommend it if you are a fan of Poe or even of murder mystery and reporting.

I find it interesting that the subtitle of the book is “Mary Rogers, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Invention of Murder.” Also on my soon to be read list is Judith Flanders’ most recent book, “The Invention of Murder.” It’s an intriguing premise if you think about it. Murder was not invented in the Victorian era, but, rather, the reporting and sensationalising of it was. What does this have to do with Poe’s Dupin Mysteries? And how do they influence the detective novels that followed, such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes? The answers are in Stashower’s book, and for the sake of the current discussion going on at Goodreads, I’m making an attempt to roughly delineate them here.

In 1825 “The Kentucky Tragedy” went to trial. Known as the Beauchamp-Sharp murder case, it involved a young woman, Ann Cooke, who was seduced and cast aside by Colonel Solomon P. Sharp, solicitor general of Kentucky. She had his child and then turned to another suitor, Jeroboam O. Beauchamp, whom she agreed to marry if he would avenge her honor. Sharp would not agree to a duel and so Beauchamp, donning a disguise, stabbed him to death. Beuchamp received a death sentence and on the eve of his execution, Ann joined him in his cell where they both attempted suicide by poison and self inflicted stabbing. She died that night. He lived long enough to be hanged.

The story inspired many people to write about it, including Poe, who, finding it the stuff of Shakespearian drama, placed it in an Italian setting and began to serialise it. It was not received well, and when a close friend advised him he would do better staging his stories in France, Poe abandoned the story.

At the time, Poe was editing and writing for The Messenger. His best pieces were generally considered to be literary criticism. One of these he criticised, and quite soundly was a book called Norman Leslie by Theodore Faye. Faye had taken his story from sensationalised and highly pulicised Manhattan Well Murder in 1800, which was said to have been the first recorded murder trial in US history.

The Manhattan Well Murder involved the murder of a young woman named Gulielma Sands, who disappeared on the evening of 22 December 1799 after telling her cousin that she and her fiance, Levi Weeks, were to be secretly married. Two days later, some of her belongings were found near Manhattan Well in Lispernard Meadows, known as SoHo today. On 2 January, her body was recovered from the well. Weeks, who had been seen with Gulielma the night of her murder, and who, on the Sunday previous, had been seen taking measurements of the well, was the chief suspect. The trial was held on 31 March and 1 April, 1800, and after five minutes of deliberation, Weeks was acquitted.

Poe called Fay’s work “the most inestimable piece of balderdash with which the common sense of the good people of America was ever so openly or villainously insulted.”

The book, as was the trial so many years before, had proved quite popular with readers, and Poe’s criticism, which was usually respected, was met on this occasion with vehement disapproval on this occasion.

Though the Manhattan Well Murder was the first to be reported, the first efforts in crime and investigated reporting are generally attributed to James Gordon Bennett. Working as a reporter for the Enquirer, Bennet covered a sensational murder trial in Salem, Mass, of a retired sea captain, Joseph White, who had been murdered in his bed. (Incidentally, some say this story inspired Poe’s the Telltale Heart.) The state attorney general, however, issued a set of restrictions forbidding any further investigative reporting on the case. Of course Bennett, who felt (or at least declared) that he was performing a public service, was outraged.

Six years later, in 1836, when another sensational murder was in the public’s attention, Bennett, now the owner of his own very successful newspaper, seized upon the opportunity to advance the cause of journalism by “discovering and encouraging the popular taste for vicarious vice and crime.” Helen Jewett was a prostitute savagely murdered with an axe and then set fire to. Polite society was shocked by the very detailed reports which appeared in Bennett’s paper. No other paper felt the subject fit for print. Bennett felt otherwise. As he proclaimed when he was refused his right to report upon the murder in Salem, “It is an old, worm-eaten Gothic dogma of Courts to consider the publicity given to every event by the Press as destructive to the interest of law and justice. . . . The press is the living Jury of the nation.”

Six years later, in 1836, when another sensational murder was in the public’s attention, Bennett, now the owner of his own very successful newspaper, seized upon the opportunity to advance the cause of journalism by “discovering and encouraging the popular taste for vicarious vice and crime.” Helen Jewett was a prostitute savagely murdered with an axe and then set fire to. Polite society was shocked by the very detailed reports which appeared in Bennett’s paper. No other paper felt the subject fit for print. Bennett felt otherwise. As he proclaimed when he was refused his right to report upon the murder in Salem, “It is an old, worm-eaten Gothic dogma of Courts to consider the publicity given to every event by the Press as destructive to the interest of law and justice. . . . The press is the living Jury of the nation.”

The man wanted to sell papers, in my opinion, and that was all. Neither did he limit his reporting to fact. Though he did visit the murder scenes, though he did dig into the histories of the victims and suspects, he often took an opposing course to those who, realising the profits the Herald was making, followed in his footsteps and covered the trial as well. When the murderer was discovered, and his conviction sure, Bennett took the opposing view (no doubt with a mind to sell a few more papers) and declared the suspect innocent. Enough of his readership sympathised with Bennett’s version of the murder’s story, that he walked free, though Bennett himself later admitted to believing in the man’s guilt.

In 1840 Poe was working for Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine, for which he wrote and published “The Man of the Crowd”, which took up, as “Politan” had, the workings of the criminal mind, and in which, using the art of deduction, the narrator reads the histories of passers by from observing the minutest details in their appearances.

In 1841, Poe exercised his literary exercises in deductive reasoning once again in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”, and drew (for perhaps the first time) a great deal of positive notice. However, a handful of reviewers pointed out “there could be no great skill in presenting a solution to a mystery of the author’s own devising.” Poe understood that the effect of the story was accomplished by his having written it backwards. The idea of unraveling a web which he himself had woven troubled even him. He wanted to be the detective himself, and to apply these powers of deductive reasoning on a real case. The story by which he would find such an outlet was unraveling as he pondered upon this problem, and the fact that it was already the most sensational murder in U.S. history provided him with an already certain audience.

In 1841, Poe exercised his literary exercises in deductive reasoning once again in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”, and drew (for perhaps the first time) a great deal of positive notice. However, a handful of reviewers pointed out “there could be no great skill in presenting a solution to a mystery of the author’s own devising.” Poe understood that the effect of the story was accomplished by his having written it backwards. The idea of unraveling a web which he himself had woven troubled even him. He wanted to be the detective himself, and to apply these powers of deductive reasoning on a real case. The story by which he would find such an outlet was unraveling as he pondered upon this problem, and the fact that it was already the most sensational murder in U.S. history provided him with an already certain audience.

Mary Rogers was already a celebrity when her body was pulled from the Hudson River on 28 July 1841. Having worked for some time behind the counter at Anderson’s Tobacco Emporium, she was well known to much of the city as the beautiful cigar girl. Posters were made of her and she was very much admired.

If the case of Mary Rogers was fodder for Poe, it was also fodder for Bennett, who took up the case as his symbol for moral reform. But as he’d already set the pattern for investigative and sensational crime reporting, so did others, and the murder of Mary Rogers became an instant sensation.

As the murdered woman was from New York, and the body found in New Jersey, weeks went by before any real investigations occurred. In the mean time, theories were bandied about between the papers. Bennett began reporting about the incompetency of the men of law in both New York and New Jersey, and it was largely owing to him that the necessary money was raised to pay the investigators and to offer a reward for finding the murderer. Still the case stagnated, and when, a year later, the unsolved case seemed to have been very nearly forgotten, Poe put pen to paper, once more revived C. August Dupin, and attempted to solve the crime for himself, using his own genius and powers of deductive reasoning and relocating the story into that French setting he was so expert creating.

What was Poe’s conclusion? The present version of “The Mystery of Marie Roget” does not give it. Poe seems to have ramped himself up to some grand revelation and then omitted it. In truth, Poe’s conclusion was wrong. What is the true story of Mary Roger’s death? Well, I’m only half way through the “Beautiful Cigar Girl”, and the discussion of the story on Goodreads has not yet begun, and so, perhaps, I’ll save the details of her murder for next week.

June 11, 2012

And they lived happily ever after . . .

…or not.

While I read a lot of non-fiction books about the Victorian era, I spend as much time, if not more, in fiction contemporary to the era, Dickens, Meredith, Hardy, Eliot (etc., etc., etc.) Here I get a real feel for what it was like to live then. I get the atmosphere and the nuances of language and setting that it’s hard to get in non-fiction (with perhaps the notable exception of Judith Flanders and Gillian Gill, who seem to write their non fiction works as engagingly as the best authors write their prose.)

While I read a lot of non-fiction books about the Victorian era, I spend as much time, if not more, in fiction contemporary to the era, Dickens, Meredith, Hardy, Eliot (etc., etc., etc.) Here I get a real feel for what it was like to live then. I get the atmosphere and the nuances of language and setting that it’s hard to get in non-fiction (with perhaps the notable exception of Judith Flanders and Gillian Gill, who seem to write their non fiction works as engagingly as the best authors write their prose.)

The sad fact is, however, that when it comes to writing weddings, fiction is an infertile crop. There’s nothing there. Weddings are mentioned briefly, or described as something that took place. We hear of the befores and afters, and then there is a blank … wherein we are meant, I suppose, to assume that the honeymoon took place and the maiden emerges a bride like a butterfly from it’s cocoon. But I wonder how often that was truly the case, particularly when women, by and large, were ignorant of the facts of life, while men were oft times all too familiar. Of course it is the common argument that a woman having grown up on a farm understood the laws of reproductive science. This may or may not be true. It was certainly not the case for Hardy’s Tess, and I have to wonder if the average Victorian maiden would even have supposed that the way of animals was the way of humans when the lights were out and clothes were off. Or, in Tess’s case … well, you get my point.

A young woman, dreaming of married life, preparing herself for it, turned to the many etiquette guides available and read advice columns on how to keep a house and how to be a good wife in all matters publicly observable. But on the actual ceremonies (formal and informal) of being married, here again we find a lack of useful information. And, more often than not, these etiquette guides provide a great deal of room for argument. They are not, after all, records of what people did, but a guideline of what the ideal situation should call for.

A young woman, dreaming of married life, preparing herself for it, turned to the many etiquette guides available and read advice columns on how to keep a house and how to be a good wife in all matters publicly observable. But on the actual ceremonies (formal and informal) of being married, here again we find a lack of useful information. And, more often than not, these etiquette guides provide a great deal of room for argument. They are not, after all, records of what people did, but a guideline of what the ideal situation should call for.

So then, what exactly was involved in the average Victorian wedding? If, indeed, there ever existed such a thing.

From the point of proposal, the parents granting consent, a date being set, legal and financial matters having been decided, the first thing to be done was to announce the intentions of the couple to the local clergyman. According to The Marriage Act of 1753, the couple must have the announcement published (by banns) for three consecutive weeks. If the couple lived in different parishes, the banns must be read in both parishes. The marriage must be performed by an Anglican clergyman and both parties, unless given consent by a parent or guardian, must be 21. (Of course the laws changed throughout Victoria’s reign, and by mid-century there were allowances for other faiths, as well as for secular marriages. I should consequently note that this is not a concise guide, simply an idea of what it might have been like for the ‘average’ couple. If, once again, there was such a thing.)

In Regency literature we often hear of ‘special licenses’ which were rather expensive and implied a certain amount of haste to the union. They were also so prohibitively expensive that they were reserved for those of high rank and connection. A respectable Victorian, however, had a third option. An ordinary license, at a cost of £2 2s 6d. What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew, (which is an entertaining read, if not actually very scholarly, as it lumps the Victorian and the Regency eras together) quotes a mid-century etiquette manual as saying: ‘Marriage by banns is confined to the poorest classes, and a license is generally obtained by those who aspire to the “habits of good society.’

There is much more to all this than I have time for here, but for a more detailed outline of the laws governing marriage look here and here. And also at Jennifer Phegley’s thoroughly concise book Courtship and Marriage in Victorian England. (I’ve also relied heavily on Mary Lyndon Shanley’s Feminism, Marriage and the Law in Victorian England, and on the a reprinted book The Married Women’s Property Act, 1882)

In an age where waste was thing to be avoided at all costs, the bride’s dress was either chosen from the very best of that which she already owned, or it was bought special with the idea of being worn again. Victoria herself set the trend for wearing white at her own wedding in 1840, but it was hardly a universal custom even fifty years later.

The service, assuming it was an Anglican service, was read from the Book of Common Prayer. (For an example of how just such a wedding might play out, see here. WARNING, SHAMELESS PLUG.)

And at last we come to that crucial element: the kissing of the bride! Did it, or did it not take place within a Victorian wedding ceremony? Well, the jury is out, and believe me, I’ve done my research. The following is from the 1873 publication, The Bazaar Book of Decorum. The Care of the Person, Manners, Etiquette, and Ceremonials.

When the ceremony is over, the question sometimes arises whether the bride is to be kissed by the bridegroom. We should leave its decision to the instinct of affection were we not solemnly warned by a portentous authority on deportment that “the practice is decidedly to be avoided; it is never followed by people in the best society. A bridegroom with any tact will take care that this is known to his wife, since any disappointment of expectations would be a breach of good breeding.” The bride is congratulated by all her friends in the church, and elderly relatives will kiss her in congratulations: This is, of course, now settled beyond all peradventure of doubt by the fact that, according to the same authority, “The queen was kissed by the Duke of Sussex, but not by Prince Albert.”

This is one of those cases where I find the etiquette guide rife with opportunity for argument. For example, as it states, in 1873, “the question sometimes arises.” So evidently there was room for this question to be asked. Is it done, or isn’t it? Which implies some see it done, or hear of it’s being done, (wish for it to be done?) have wondered if it should be done, and from other sources have heard that it is a practice to be avoided. To me this only proves that it is hardly an established rule. And the idea that the matter should be discussed beforehand leaves me simply reeling with ideas for plots. Can you imagine it? Cecil asks of Lucy, “My dear, do you think I might be allowed a kiss at the end of the ceremony?” “Why Cecil, upon the completion of the ceremony I am yours to do with what you will.” Ok, yes, that’s just my mind running rampant on the subject, (and perhaps A Room With a View does not provide the best characters from which to draw. The story, I’m sure, would be quite different were it George rather than Cecil, who’d no doubt take advantage of an impulsive moment, whether Lucy, or the crowd, objected or not. [And yes, I am aware Forrester is Edwardian and not Victorian.]) At any rate, the mere suggestion that there should be a discussion beforehand, and that the bride might be disappointed, only leads me to suspect there were as many ceremonial kisses as there were not.

This is one of those cases where I find the etiquette guide rife with opportunity for argument. For example, as it states, in 1873, “the question sometimes arises.” So evidently there was room for this question to be asked. Is it done, or isn’t it? Which implies some see it done, or hear of it’s being done, (wish for it to be done?) have wondered if it should be done, and from other sources have heard that it is a practice to be avoided. To me this only proves that it is hardly an established rule. And the idea that the matter should be discussed beforehand leaves me simply reeling with ideas for plots. Can you imagine it? Cecil asks of Lucy, “My dear, do you think I might be allowed a kiss at the end of the ceremony?” “Why Cecil, upon the completion of the ceremony I am yours to do with what you will.” Ok, yes, that’s just my mind running rampant on the subject, (and perhaps A Room With a View does not provide the best characters from which to draw. The story, I’m sure, would be quite different were it George rather than Cecil, who’d no doubt take advantage of an impulsive moment, whether Lucy, or the crowd, objected or not. [And yes, I am aware Forrester is Edwardian and not Victorian.]) At any rate, the mere suggestion that there should be a discussion beforehand, and that the bride might be disappointed, only leads me to suspect there were as many ceremonial kisses as there were not.

I also find it interesting that the example of the Queen was used. (Note that the author did not cite said ‘portentous authority’.) The Queen was married some thirty years previous. Did that mean, then, that Victoria’s example was only just catching on if the question was still being raised in 1873? Neither was Victoria the prude we like to think her. Her marriage was as much a marriage of state as it was romance. Also they were neither of them showy people when it came to their own sentiments. It’s also noted that her uncle (Augustus, Duke of Sussex) kissed her. Not entirely sure he’s a reliable foundation upon which to set a pattern of appropriate social behavior, but… ok.

And what of the honeymoon? Well, literature is simply bursting with examples of these post-wedding conjugal trips, are they not? Er…maybe not. Once again, turning to Jennifer Phegley, she cites a rather cynical work entitled, How to Be Happy Though Married.

You take … a man and a woman, who in nine cases out of ten know very little about each other (though they generally fancy they do), you cut off the woman from all her female friends, you deprive the man of his ordinary business and ordinary pleasures, and you condemn this unhappy pair to spend a month of enforced seclusion in each other’s society. If they marry in the summer and start on tour the man is oppressed with the plethora of sight-seeing while the lady, as often as not, becomes seriously ill from fatigue and excitement.

Not a very pretty picture, is it? And it is not so difficult for me to imagine what it was like for a very innocent wife to be suddenly educated in the ways of married life. For the innocent, I imagine it was rather a shock. For the not so innocent, it might actually be traumatic, particularly if the man is inexperienced with inexperienced women, or inexperienced himself, or not quite certain how to merge his carnal impulses, heretofore deemed evil, with those of wholesome family life.

Yes, the Victorians were complicated. Roll your eyes if you will, but I relate to them, and I admire them in my way.

But here, perhaps, is where it might be best to take the Queen’s example, after all. She may not have taken much of a wedding holiday, but she made the most of her time. From what we understand of her now, related in Gillian Gill’s gripping We Two, she was no shrinking violet when it came to matters of conjugal romance. In fact she might very well have taken the lead. At least we understand, from trustworthy accounts, and by the number of children they had (which she would rather not have had) they had a very healthy love life.

But here, perhaps, is where it might be best to take the Queen’s example, after all. She may not have taken much of a wedding holiday, but she made the most of her time. From what we understand of her now, related in Gillian Gill’s gripping We Two, she was no shrinking violet when it came to matters of conjugal romance. In fact she might very well have taken the lead. At least we understand, from trustworthy accounts, and by the number of children they had (which she would rather not have had) they had a very healthy love life.

Personally speaking, I like to think that the general silence on the subject was out of respect of the union and not because they were all fumbling around in their bed clothes.

But then I’m an idealist.

So, what do I do when there is such a lack of reliable information to draw from? How do I write these weddings and newlywed scenes? All I can do is try to strike a balance between what I deem would be appropriate to the situation and what my modern day readers would want. And really . . . a wedding without a kiss? Are you kidding me?