V.R. Christensen's Blog, page 11

November 22, 2011

In the Shadow of Gaslight

I watched it last night. I'd seen it before, many years ago, and I remember it being eerily fascinating. I did not remember how uncomfortable it made me. Perhaps it did not then. Perhaps, so many years later, I have more reason to be made uncomfortable by the subject matter than I did when I was a teenager.

I watched it last night. I'd seen it before, many years ago, and I remember it being eerily fascinating. I did not remember how uncomfortable it made me. Perhaps it did not then. Perhaps, so many years later, I have more reason to be made uncomfortable by the subject matter than I did when I was a teenager.

My desire to see it again was sparked by an article sent to me by a friend. Since then, it's been passed around quite a bit, and I do believe it's something everyone should read. In fact, it makes me wonder if, in writing this, I'm really not writing a continuation (sort of) of my post last week. "Why it Matters." You see, I believe History, and Historical Fiction especially, to be relevant. There's a reason it's on the rise. People are missing something. And, at the same time, I think we subconsciously know that the injustices we fought so hard against, challenged policy makers and world leaders, campaigned and protested and even fought wars for, are really just as rampant now. Only they have taken on new disguises. "Gaslight" unravels a bit of that and provides a very interesting example.

The article in question came from the Huffington Post, and is entitled, "A Message to Women From a Man: You Are Not Crazy" by Yashar Ali. THe article casts some light on a psychological phenomenon called 'Gaslighting' by telling us a bit about the movie that inspired the term. Gaslight (it can be watched via Amazon's Instant Video program) is Historical Fiction in itself. Filmed in 1944, the events take place (I'm guessing by the costume) in the 1890′s. Ingrid Bergman's character, Paula, witnesses, as a young girl, the murder of the aunt who raised her. She is thereafter sent to take music lessons from the man who taught her aunt, a famous singer. While under his tutelage, she is courted by the accompanist and though she is uncertain of him, she does agree to marry him. He hardly gives her a chance to say otherwise. By a trick of clever manipulation, he convinces her she wants to give him the home she inherited in London, a house she has never returned to since the death of her beloved aunt.

Upon arriving there, her husband insists they receive no visitors and keep to themselves. His excuse, at first, is that they are still honeymooning. But then, later on, he begins to plant the idea in her mind that she is not quite well, not emotionally, certainly not mentally. She is forgetting things, losing things, taking things without remembering. In order to calm her fears of the house, he has all of her aunt's things removed to the attic and the attic boarded up.

Mr. Anton is a musician and an aspiring composer, but cannot work at home. At night he goes out to a room he has rented. But it's when he's  gone that the house truly haunts her. Alone in her room she notices the gaslights dim, as though someone were in the house. But no one is, the servants assure her. She hears footsteps above in the attic, but the housekeeper, who is deaf, cannot hear them, and her husband, when she tells him of the strange occurrences, insists she is imagining things. By small means he tightens the screw until she believes herself loosing her grip on reality. Her husband threatens to have her committed. By having her put away, he can search the attic quite openly, rather than under cover of darkness, for the jewels he knows are in the house. It was why, after all, he murdered Paula's aunt. It is why, after all, he convinced Paula to marry him and to bring him back to this house, so that he could continue the search she interrupted so many years ago.

gone that the house truly haunts her. Alone in her room she notices the gaslights dim, as though someone were in the house. But no one is, the servants assure her. She hears footsteps above in the attic, but the housekeeper, who is deaf, cannot hear them, and her husband, when she tells him of the strange occurrences, insists she is imagining things. By small means he tightens the screw until she believes herself loosing her grip on reality. Her husband threatens to have her committed. By having her put away, he can search the attic quite openly, rather than under cover of darkness, for the jewels he knows are in the house. It was why, after all, he murdered Paula's aunt. It is why, after all, he convinced Paula to marry him and to bring him back to this house, so that he could continue the search she interrupted so many years ago.

Paula is not crazy. Mr. Anton is a genuine manipulator.

And here is where Mr. Ali draws his comparison, by showing how often such tactics are still used today. How many of us grow up believing we are hysterical and crazy? How many times do we, in our communications with our bosses and our more dominant counterparts (I will not insist that only men do this) do we find ourselves being accused of being crazy or irrational simply because we dare to react to the way people are treating us? Or, on Facebook, or Twitter, or anywhere else where opinions are shared freely, do we not find ourselves accused of being uneducated, or small minded, or just insane, because we do not see life the same way as another? I have a very dear friend who on occasion likes to suggest I'm irrational simply because his over-rational mind leads him to conclusions my more intuitive one does not. (For fairness sake, I do not believe he does it on purpose to make me feel bad. I think he truly believes me irrational.) I'm not any less sane or even right than he is. I just see things differently.

Yet women certainly are targeted as weaker, emotionally and psychologically, just as often as they were, and perhaps in far more insidious ways, than they were a hundred or so years ago. Women used to have a right to expect to be treated with a certain amount of respect. A gentleman who had nefarious motives had to be quite suave to get his way. Now women are as knowledgeable about the world as men, and yet, somehow, they've convinced us that to keep their attention, we must be open to doing and being just exactly what they want. Toys. Men don't have to hide their motives. Men want easy conquests, and we give them that. What does this do for us? It enslaves us once again, but more securely, for now there is no law to fight, no unjust institution keeping us bound as property. We have made it of ourselves. It makes me want to scream and throw things.

And it makes me want to cheer when a woman can find a way to rationally make her point. When she has the courage to stand up and fight for what is rightly hers. Most especially when it is that most precious of all things: SELF.

Women today, young women in particular, are growing up in an environment inherently threatening to them. They didn't create it. It was given to them by we who made it possible. What woman is safe today? The statistics say that one in three women reports being the victim of sexual abuse at some point in their lives. That's REPORTS! My feeling is that there are far more. I never reported my abuser. Did you?

Young women growing up in this environment read what they know, what resonates with them. They read (and watch) of Vampires and Werewolves and damsels in distress. Women who need, and desperately, protection. And we wonder why entertainment has become so dark. It's no wonder. Not really. It's because they feel like they have to wage an all out war to preserve themselves.

Just ask them if they don't.

There is another movie that comes to mind. It's a modern film, quite modern, in fact. It got horrible reviews, but I'm of the opinion that people really didn't get it. And those who did were offended because it was a message leveled right at their midsections, and they were not expecting it. The movie? It's aptly enough titled.

I'll write more on that in the near future. In the mean time. See it. Watch it. Think about it. It's saying something really uncomfortable about our day and age. It's asking some very hard questions and pointing some very sharp accusatory fingers. It is, to my mind, the most moralistic, socially provoking movie of this century so far. It blew me away. (For a clue as to why, read this.)

Watch it. Think about it. Now.

And let's discuss.

November 14, 2011

Why it matters

The Charge of the Light Brigade

We've all heard the axiom that those who fail to learn from history are destined to repeat it. And so we study our history lessons and believe our teachers and know with everything that is in us that we would never allow another dictator to take control of us, to kill millions, to tell us what to think and believe and love and hate. We know the dates. We know the names and places. We have seen, in black and white, the atrocities. And yet, for those of us who did not live during WWII, it's a very difficult thing to understand how humanity can ever have come to that. We cannot look within a man's mind and know with any certainty what it was he was truly thinking when he devised his plan–if it came all at once or by degrees. It is impossible to know exactly what it was that made him feel so strongly and how he was able to influence so many to agree with his philosophies. Just what was it that got us there in the first place?

Was it possible that WWII all started because of an innocent case of English xenophobia? Was it simply because the common Englishman could not abide the thought of a German king? It's sort of a reversal of thought, isn't it? An irony. And yet it's just possible.

Victoria, herself, was of German stock. It was only because her mother had the foresight to keep her in England, near her more powerful English relations (though they had turned their back on her) that Victoria was considered truly English. Albert was Victoria's first cousin, a Prince of Belgium, and the nephew of the man who had once expected to sit on the English throne himself. Leopold trained Albert to be the perfect King. And he endeavoured to be. In fact he worked himself quite literally to death designing exhibitions and art museums, promoting technology and invention, trying to figure out the best mode of avoiding war with this nation or that, enlightening the people and educating the common man. By bringing prosperity, security and power to a nation made greater by his influence. And still his subjects despised him. They would give him no glory, no honour. They did not trust him. They could not. He was a foreigner.

Victoria, herself, was of German stock. It was only because her mother had the foresight to keep her in England, near her more powerful English relations (though they had turned their back on her) that Victoria was considered truly English. Albert was Victoria's first cousin, a Prince of Belgium, and the nephew of the man who had once expected to sit on the English throne himself. Leopold trained Albert to be the perfect King. And he endeavoured to be. In fact he worked himself quite literally to death designing exhibitions and art museums, promoting technology and invention, trying to figure out the best mode of avoiding war with this nation or that, enlightening the people and educating the common man. By bringing prosperity, security and power to a nation made greater by his influence. And still his subjects despised him. They would give him no glory, no honour. They did not trust him. They could not. He was a foreigner.

Victoria and Albert's eldest daughter had married Prince Frederick of Prussia. It was a political alliance, though amicable. Their union was meant to unite the ever changing (and consequently unstable) German state. The only problem was that Vickie was as despised in Prussia as her father had been in England, yet young Vickie and her husband had both been trained in international politics and diplomacy. Had they the power to influence political opinion, they might have shaped a peaceful future for all Western nations for generation to come.

They had that opportunity, too. In 1862, the Prussian legislature opposed William I's plans for his army. In response, the Prussian King wrote a statement of abdication. Frederick need only have signed the document to become king. But he didn't. William ruled for a further 17 years, and in that time instilled in his grandchildren a violent hatred of all things English. Young Wilhelm was taught to despise his English grandmother, and in fact to blame her for much of the evil of the day.

Had Albert had the strength to bear through one more year, he would certainly have advised Frederick to accept the throne and, by a sort of partnership, or mentorship, perhaps, the Prussian political landscape would have been steered along paths of peace and mutual prosperity. And, perhaps more importantly, the infant Kaiser would have been reared in love and with an understanding of the good and peaceful intentions of his English relations. Instead he became a warmonger, determined to own all of Europe and to control it for himself. WWI ensued, and the War to End All Wars ended not in victory and defeat, but in an armistice and sanctions so strict and oppressive they created an atmosphere ripe for the rise of yet another tyrannical leader, more powerful and far madder than the last.

Had Albert had the strength to bear through one more year, he would certainly have advised Frederick to accept the throne and, by a sort of partnership, or mentorship, perhaps, the Prussian political landscape would have been steered along paths of peace and mutual prosperity. And, perhaps more importantly, the infant Kaiser would have been reared in love and with an understanding of the good and peaceful intentions of his English relations. Instead he became a warmonger, determined to own all of Europe and to control it for himself. WWI ensued, and the War to End All Wars ended not in victory and defeat, but in an armistice and sanctions so strict and oppressive they created an atmosphere ripe for the rise of yet another tyrannical leader, more powerful and far madder than the last.

It is speculation, of course, that Albert's prolonged life would have absolutely prevented WWI and the suffering and violence and unconscionable waste that followed. And yet the story (presented brilliantly by Gillian Gill in her book We Two) does serve as a lesson to me in my private dealings with my fellow men.

Is not Society, after all, nothing more than the sum total of individual choices?

As I said, it is impossible to know what truly went through the minds of these people. That is where the narrative biographer, or, just perhaps, the historical fiction author takes over.

First Afghan War 1842

Although none of my books deal with actual historical figures, they are no less true. I write of what I know, of conflict of unhappiness and struggle. Of joys and victories. Of obstacles. Circumstantially, we live in a world entirely different from those who lived a hundred years before. We have wireless devices and unrestrictive clothing, laws that deem us (mostly) equal. And yet the same emotional struggles define our lives. We are no freer of responsibility than our predecessors, even if we choose to ignore the consequences. Laws and society do not limit us in the same way they once did, and yet we are a society of addicts and debtors and dependents. We say we are more compassionate, and yet we still have our prejudices, our hatreds and intolerances, just the same as those before us. We still have poverty, we still have desease. We are so smart…and yet remain so unwise.

I'm not very good at memorising dates and events. When I do my research it all goes into binders and files and blog posts and I have to turn to it again and again. And yet when I pick up a book with a good narrative, whether it be Non fiction or fiction, and the author allows me to truly engage with those events, even if they are merely events of attitude and societal cannon, I become engaged, I remember. The wisdom of those who came before me is retained. And I learn. I feel. I cease to judge.

To gain wisdom from another person's knowledge is a blessing. Much better than learning by personal experience. And whether I am reading it or writing it, I've learned to consider Historical Fiction one of the greatest of gifts. It is a powerful tool for learning of past events and social climates, of attitudes and philosophies in a way I can truly relate to and engage in. It allows me to compare past circumstances to my own. To compare, even, past lives to my own.

History is the story of us. It has relevance and importance. It has meaning. And it matters.

November 7, 2011

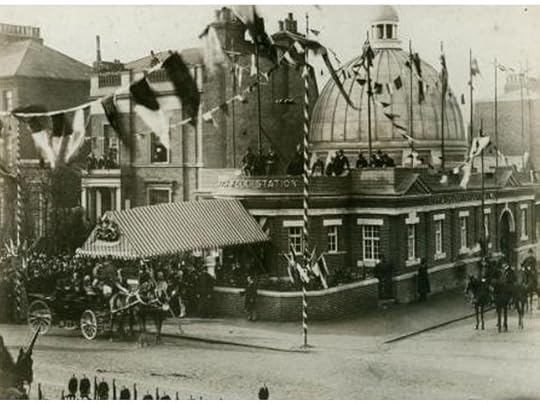

The London Tube turns 121!

As I've recently begun to examine my first book, Cry of the Peacock (formerly Kentridge Hall) anew, I realised that I very nearly missed the anniversary of one of the Victorian Era's greatest achievements. In celebration of the 'Tube' as it is now affectionately called, I thought I might post my research on the 'City and South London Railway', the opening celebration of which, is featured in the book. Read the excerpt here.

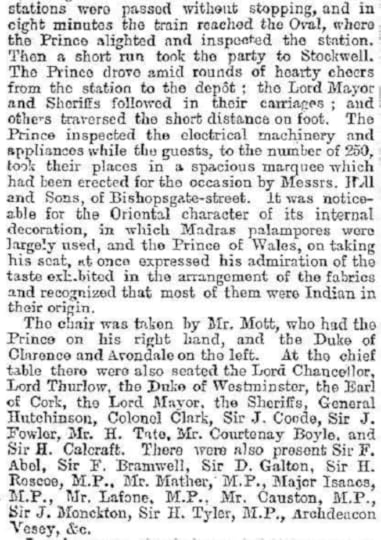

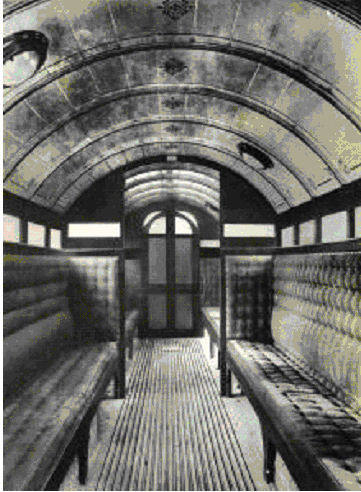

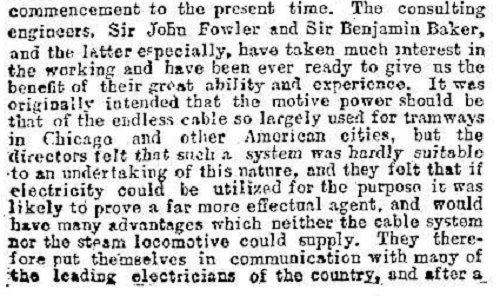

From the London Times, 5 November 1890

See the article for 4 November 1890 here. This article describes the train and how it was constructed, etc.

See the article for 4 November 1890 here. This article describes the train and how it was constructed, etc.

November 3, 2011

An Interview with V.R. Christensen

The lovely Hannah Warren was good enough to interview me. Read it here!

October 31, 2011

Hallam's Wood

He had drunk too much. He knew it. And he suspected his horse knew it, too, for the animal listed heavily to the edge of the lane, brushing him up hard against the hedgerows and the overhanging limbs of the trees. As if the beast meant to be rid of its burden. He had newly entered Hallam's Wood, and crossing it at this time of night was a thoroughly unpleasant business. If he could only find that boy. He was to be on a train this night and out of his hair for good. To be made a fine man of, or so his 'uncle' had promised. But first he must be found.

He had drunk too much. He knew it. And he suspected his horse knew it, too, for the animal listed heavily to the edge of the lane, brushing him up hard against the hedgerows and the overhanging limbs of the trees. As if the beast meant to be rid of its burden. He had newly entered Hallam's Wood, and crossing it at this time of night was a thoroughly unpleasant business. If he could only find that boy. He was to be on a train this night and out of his hair for good. To be made a fine man of, or so his 'uncle' had promised. But first he must be found.

In a nearby thicket he heard the rustling of movement. Perhaps the boy was here, watching him, hiding and laughing at him in his ineptitude. He'd teach the brat a lesson.

"Charlie!" he yelled out. But the sound was muffled by the wind that rose up and shook the branches of the leafless trees as the horse beneath him shivered and sidestepped nervously along the path.

"Get on with you, you brute!" he said and gave the animal a sharp smack with the whip.

The horse continued to tense and flinch, but moved on. And then he stopped altogether. There, up ahead on the path, was a figure heavily shrowded. With great effort, he at last encouraged the animal forward. It snorted, but with further application of the whip and a couple of sharp kicks, the horse was at last persuaded to move onward. They came upon the figure at length—a woman. She was not on the path, not walking, but standing several feet off, so that she was entirely cloaked from the moonlight by the trees. Still, he could see the paleness of her face, the flashing glint of her eyes as she watched him pass by. His blood ran a little chill at the sight of her staring at him so, as if he had caused her some great offense.

Turning back to the road, he pulled his coat collar close around his neck and lowered the brim of his hat to shield him from the wind. His horse, who had, moments ago, required the utmost in encouragment to walk on, could hardly now be kept at a walking pace. Very well, a brisk trot would do them both good.

They had gone in this way for several minutes before the horse stopped short again, planting its hooves soundly in the dirt and nearly flinging its rider from the saddle.

"Blasted animal!" The bloody thing needed a sound thrashing. The horse turned, and stamped, and turned about some more, and would not stand still whatever pains were taken to hold him. He turned the horse sharply about that they might continue onward, but he too was suddenly stopped, frozen to the spot. Just ahead, as if they'd ridden in some perverse circle (he knew they had not) was the woman, standing before him once more and just off the path. And just as before, she watched him with so cold and fixed a gaze that he felt instinctively that he'd done her some great wrong, though he did not know her from Eve. And yet there was something, nevertheless, vaguely familiar about her. Whoever she was, whatever she wanted, he was not going to stay and find out. He kicked the horse onward, and struck him hard with the whip, but the animal would not move. Not for anything. He dismounted, and, taking the reins in hand, endeavoured to move him onward. With much threatening and execrating, the beast at last moved forward, nervously, reluctantly. While the woman watched.

Standing in the moonlight now, he could see that she was fair. Exceedingly fair. Unnaturally fair. Her hair was long and she wore it loose, great tresses of it pouring out from the hood of her cloak. He could make out the vague outline of her features, but the details of her countenance were still hidden from him. And yet that feeling persisted to gnaw at him.

"I know you, do I not?" he asked of her, desperate to have the question answered once and for all.

One corner of her mouth twitched into a smile that was almost a snear. "Yes," she said. And her voice was that of an angel's though her tone was condemning as hell itself. "And I know you, Miles Wyndham."

One corner of her mouth twitched into a smile that was almost a snear. "Yes," she said. And her voice was that of an angel's though her tone was condemning as hell itself. "And I know you, Miles Wyndham."

He took an instinctive step away from her and tripping over a root, found himself flat upon the ground. She continued to approach him, taking not the slightest notice of the horse, which had reared up and was now pawing pawing the air just above his head. It pierced the air with a bloodcurdling sound, as if screaming in fright. The beast landed once more upon the ground and toe off into the night, its reins flapping wildy behind like streamers.

And now he was alone. Though not quite alone, for the woman was standing over him now. Staring, never blinking, and watching him hungrily. One thin, pale hand stretched out toward him. He scrambled to gain his footing, but failing, fell hard once more on his back.

"What do you want of me?" he managed. She did not answer him. "What do you want, I say!"

"I don't want anything from you, Miles Wyndham," she answered him. "Perhaps I did once. I have learned better."

"Tell me who you are. I beg."

She continued to stare at him, turning his blood to ice with her gaze. "You don't remember?" she said at long last as her mouth turned up once more into a sort of half-hearted and melancholy. "Me, who you once professed to love so well?"

Dammit! Who was she? He thought back through his many conquests. Was she some farmer's daughter? A village girl once enjoyed and instantly forgotten? This woman looked familiar, yes, but he could not place her. And great heaven above, she was beautiful! Maddeningly beautiful, if she did not have such a murderous fire in her eyes.

"I… I don't remember. Forgive me. I can't recall." And yet he knew he should. Had he held her in his arms once, seduced her? Ruined her? Or did he simply desire to have her now, prone and subdued? No. No, that was not it, for he feared this woman. Wanted her, desired her, yes, but feared her like death itself.

"Stand up," she said to him now. "Stand up and look at me."

He raised himself, with some trouble, to his feet. Slowly she lifted her long white fingers to draw off her hood, revealing her face to him.

The wind was knocked out of him, but only for a moment. "Bess!" he said. "Bess, is that you?" And yet it couldn't be. He had left her an hour ago, ill, coughing, fevered and spent. Lying on the floor where he had left her. He had been wrong to hit her. She only wished to protect her child, but he had struck her down. Was that why she was so angry now? Or was it…? But no. No, it wasn't possible. It could not be her. This woman was so young. A mere girl. Perhaps he was drunker than he'd thought.

"Where is my boy, Miles? Where is Charlie?"

"Is it you, Bess? Truly?"

"Where is my boy?" she asked again. "Our boy."

"I'm going to find him. I'll bring him home."

"You lie."

"I promise, Bess. You have my word. Now go home."

She hesitated for a moment. Her smile reappeared, and seemed, for the moment, almost sincere. But the sadness in her eyes remained. "I am home."

"What? You speak nonsense."

"No! You speak nonsense. Nonsense and lies are all you know. Don't touch me!"

This last she exclaimed, nearly screamed, as he approached her. She did not seem quite real to him. And yet, as he had been drawn to her once long ago, he was drawn to her now. He wanted to have her, as she had been, as he first remembered her. He wanted to have her and make her a part of him. It could not be so wrong now, not after all they'd been through together. But she would not have him near her.

"Tell me what to do, Bess."

"Leave the boy alone. Leave him and return to the cottage."

"I'll go if you let me take you." And he held out his arm to her. He waited for her answer, but she only shook her head.

"Don't be foolish. Come." Still she would not consent. Did she distrust him so much? Perhaps she had a right, after all. But he would convince her as he had convinced her so many times before. He took another step toward her that he might lay his hand upon her elbow. But she let out such a blood curdling scream that he stopped and took a step or two away from her. "Good God, what is wrong with you?"

She stood there shaking. He had thought she was breathing hard, but she did not appear to be taking any breath at all. He rubbed his face, his eyes, his head. If he hadn't had so much to drink he might be able to think straight, but he was growing increasingly panicked as the moments passed. At last, as if she'd been holding out all this time, she drew in a long ragged breath. He expected her to cough at any moment, but she did not, just drew it in and in and seemed never to stop. And then she did, to let it out again with a hiss that was almost piercing, like a high pressured release of steam, sharp and deafening. Only he could hear her words. And as they poured out of her, he seemed to drain his blood.

"You have killed me. Don't you see it? You took everything from me? My heart, my hopes, my youth. My life. And now you want to take my child!"

"Bess, I've told you. This isn't my—"

"Stop!" she screamed again, drawing the word out until it seemed she had no more breath.

And he did stop. In fact he could scarcely move. His throat was dry. He could not speak, could not swallow. He hardly dared to draw breath.

Yet she was silent now. And her silence frightened him very nearly as much as had her words.

"Bess," he tried again. "Will you go home?"

"You go," she said. "You will see me there."

"Bess?"

"Goooooo!" she cried out in another desperate shriek.

And he did. In fact he almost ran as the echo reverberated through the night air, wrapping around him, piercing his ears, and his heart. Filling his head with all manner of dark ideas and darker fears. He would go. He would go to the house. Perhaps the boy was there now and he could quit this game.

Good heaven! No, great hell! What if she had gone mad? What if poverty and disappointment and illness—and opium—had driven her to madness? What then? She would be disposed of, sent away. Dealt with! And what would he do without her? And suddenly he regretted it all. He had driven her to it. This was all his doing. He was careless, reckless, selfish and irresponsible, and she had suffered because of him.

Bess's words rang through his head like some demented church bell, "You have killed me. You have killed me!" He was running now. Running fast, though he could barely see in the darkness. And he was still dizzy from the drink, his vision blurred. What if he had imagined it all? What if it was just a hallucination? Perhpas, by mistake, he had taken in some of the opium he had found in Bess's cottage. He'd dicovered them, the bottles, collected them. Dozens of them. He had smelled the contents, had read the labels. Had dipped his finger to be sure. Yes. Laudanum. But surely he could not have consumed enough to bring him to this?

At last the cottage was in view. The light was on. Charlie must be there. And he was relieved. He might hug the boy he was so relieved. His son! And he nearly wept. Perhaps it was ten years too late. Better late than never, as they say.

At last the cottage was in view. The light was on. Charlie must be there. And he was relieved. He might hug the boy he was so relieved. His son! And he nearly wept. Perhaps it was ten years too late. Better late than never, as they say.

He had nearly reached the cottage. Lights shown from within. Surely Charlie was there. But he stopped again upon seeing the figure of a woman cross the window. How was it possible Bess could have returned so soon? He walked, as quickly as he could (he could run no more) the remaining distance and threw the door open wide. He was not prepared for what he saw within. Sitting in Bess's favourite chair, was not Bess, no, but his cousin's wife. The scene grew more puzzling every moment.

"What brings you here, Mrs. Hamilton?"

She did not answer him, but held all the tighter to the burden before her, as if she meant to protect it, to shield it, perhaps, from him. He took a step within and examined her more closely. And then he recognised the quivering mass before her.

"There you are, Charlie! I've been looking for you." And he found, afterall, that he was quite angry, despite the relief he imagined he had felt but a few minutes before.

Yet the boy didn't answer, but clung to the woman in whose arms he was hiding. The sight of so much weakness disgusted him.

"I'm talking to you, boy!"

"Leave him be, Mr. Wyndham."

Interfering baggage! He might have struck her too. But he was arrested from the very thought by the sight of a gentleman stepping out of the bedroom.

"What is this!" Wyndham demanded. Who presumed to enter where they had no right? Yet no one offered any explanation. None at all.

Hamilton himself appeared now. Perhaps his suspicions were true. Perhaps Charlie was not his, after all, despite her protestations.

"What is this, I say!" he demanded. Yet no answer was offered, even still.

Well, he would not wait in vain. He crossed to the bedroom door. He would have an answer of her if he had to beat it out of her. "Bess!" The word was only half past his lips when he choked on it. "Bess?" It was barely more than a whisper now. "Bess?" he called more loudly. More confidently. But the confidence faded. He fell to his knees before the bed. For there she lay. His darling Bess. She was prone before him, spectre-like as the moonlight shone through the window and rested on her face, gaunt with age and ill use, with waste and disease and disappointment. Her skin was so pale, save for the bruise at her temple, and the spot of darkest red where the blood had dried. She lay, very still. Resting she was not. Not sleeping, no. Bess was dead, and had been these many hours.

October 24, 2011

The Hampstead Murders – Part eight (the last)

THE EXECUTION OF MRS. PEARSEY

THE EXECUTION OF MRS. PEARSEYA STRANGE REQUEST

Shortly after 10 on Monday morning Mr. Freke Palmer had a parting interview with the prisoner. Her first desire was to ask Mr. Palmer to distribute certain of her articles and trinkets, all of very small value, among her relatives and friends.

Mrs. Persey next requested that Mr. Palmer should cause an advertisement to be inserted in the Madrid papers addressed to certain initials, with these words, "Have not betrayed." Surprised at this commission, Mr. Palmer asked whether it had to do with the case. "Never mind," said she. He then asked, "Do you admit the justice of the sentence?" "No," was the reply; "I do not. I know nothing about the crime." "But," it was argued, "even if you did it in a trance, you must have some idea or shadowy recollection of the matter?" "I know nothing about it," she reposted. "If you have any facts to reveal, and will let me know them, even at this late hour, I will lay them before the Home secretary in the hope of obtaining mercy." "I have nothing more to say; don't forget about those things. Good-bye." And she went again across the yard to her cell."

THE WISH TO SEE FRANK HOGG

At the convict's particular and reiterated request permission was given to the man Frank Hogg to visit her between two and four on Monday afternoon, and it was quite evident that she had built upon seeing him once more. As the time passed on and he did not come she grew somewhat nervous and impatient, and when it was evident that she would be doomed to disappointment a terrible fit of dejection seized her. She lay on her bed with her hands over her face for some time sobbing, but not speaking. When this was over, and she rose again, her face was calm, her voice had recovered its quiet low tone of speaking, and she resumed her reading at the table, without giving any sign of the storm of emotion she had just passed through. The wretched woman seemed to have hardened her heart, and determined to maintain the strictest silence.

THE EXECUTION

The execution took place at eight o'clock. The condemned woman was removed from the cell in which she had been imprisoned into the condemned cell in the male wing, which is in close proximity to the execution shed. Mrs. Pearsey was attended by three women warders, and on the way was in tolerably good spirits, but complaining of the dense fog. Soon after 10 o'clock the Rev. Mr. Duffield, the chaplain, returned to the prison, and proceeded immediately to her cell. He had an earnest conversation with her for more than half an hour, and urged her, "Do not be launched into eternity with anything on your mind which you can now explain." She replied calmly, but faintly, "I have nothing to explain. I am not guilty."

It was about six o'clock when the chaplain next visited her, and she received him in a languid manner always evading conversation on the subject of the murder. the chaplain had hoped to have received from her at that trying moment some confession in regard to the part she bore, and in solemn words pointed out her position once more. He urged her to make some reparation to her fellow creatures by letting them know the truth, but all he could get form her was that it was absurd to suppose that Hogg was connected with it. For more than an hour this painful interview was maintained, but no change was made in her obdurate contention that she was not guilty.

At length, just as the clock pointed to five minutes before the hour he said, "The foot of the executioner is almost at your door. Now I ask you, for the last time, is there anything you have to say to me?" "No." "Do you admit the justice of your sentence?" "Yes; but the greater part of the evidence was false." "Then you mean to say by that that you are guilty?" asked Mr. Duffield, in anxious expectation of a reply. But no reply came; she shook her head and sat down upon a form.

The prisoner was pinioned, the white cap drawn over her eyes, so that she saw not the instrument of death. Guided by Mr. Berry, the executioner, the warders led her directly under the rope. The shed was lighted by gas, and the front, which on occasions of execution is generally raised, remained closed. The chaplain meanwhile had placed himself just in front of the wretched woman, reciting passages from the burial service.

Arrived upon the drop, the female warders left her and two make warders took their place while Berry fixed the rope. Not a word was spoken after leaving the cell by the prisoner or anyone else, save the solemn phrases of the liturgy. So even as the strap was affixed round her dress just below the knees. Berry touched the warders, who stepped back, then laying his and on the lever he pressed it down, the floor opened, and Mary Eleanor Pearsey passed way almost instantaneously from sight. Death must have been imediate, there was only but the smallest vibration of the rope–which gave a drop of 6ft.

HAVE NOT BETRAYED

Mr. Freke Palmer was interviewed with reference to the request made by Mrs. Pearsey to insert in the Madrid papers a certain advertisement containing the words "Have not betrayed." As will be seen by the appended conversation Mr. Palmers's replies open up quite a romantic story.

"What did Mrs. Pearsey really say, Mr. Palmer?"

"She asked me to have inserted in the London papers, and in any other paper that would be read in Madrid, the following message: 'M.E.C.P.–Last wish of M.E.W.; Have not betrayed."

"Did that refer to the crime?"

"Not at all. I asked her that, and she said, 'No.' "

"Did you ask her what it referred to?"

"Yes; I said to her, 'Does it refer to the marriage you have told me took place between you and a certain gentleman?' She replied, 'Yes.' "

"What are the facts?"

She had told me she was a married woman, but would not divulge the particulars."

"How much do you know about it?"

"Only this. She told me she was married in some chambers at Piccadilly to a gentleman in the presence of his valet, by a clergyman in robes."

"Did she give you the name of her husband?"

"No; she said she could not, as she had taken an oath never to divulge it."

"How long did she live with him?"

"Not long. He left her shorty after the marriage, but contributed to her support for a few months. Since then she has not heard of him."

"I suppose you have often pressed her for further particulars?"

"Yes, but she would never give them. She would only repeat, 'I have taken an oath never to divulge.' I have tried to trace the marriage, as it might have been very important in reducing the supposed motive for the crime."

"Did you say anything to her about the marriage?"

"I expressed to her my doubt as to the legality of the marriage, and suggested that it might have been only a form gone through for the purpose."

"What did she reply to that?"

"She said she believed the marriage was perfectly legal, and appeared to be depressed by the idea that it could not be legal, and that she might have been deceived by the man she supposed to be her husband."

"Had she any idea where her husband was?"

"She believed him to be in Madrid."

"Do you know when the marriage took place?"

"It was some years ago."

"Before she saw Pearsey, I suppose?"

"Yes, when she was 16, from what I could gather. She was 24 when she was tried. That is all I can tell you bout the marriage."

"What is your personal opinion about 'Mrs. Pearsey,' to use the name by which she was commonly known?"

"It always seemed to me that her lot had been a very hard one, that she had been badly treated by many people. In fact, the whole world appeared to be against her and no one for her. She was a woman of some character and of great intelligence. She was not a common low character, as people make out, although her character will not bear investigation."

"Did she express to you a wish to see Hogg?"

"She did, and I strongly persuaded her not to do so. But she seemed very anxious to see him and to give him some message–I don't know what it was."

Mr Freke Palmer concluded by saying: "I felt very much disappointed with the Home secretary's decision because of the extraordinary mass of reliable evidence which I collected to show that the prisoner must be insane. I was also disappointed by his decision to allow three experts to see her on one side and no one at the same time from our point of view."

Mrs. Wheeler (Mrs. Pearsey's mother) was asked if she knew anything of her daughter's strange request to her solicitor to insert an advertisement in Madrid papers–"M.E.C.P.– Last wish of M.E.W. Have not betrayed." the mother said, "It was quite a mystery to her, and she could not understand it." She recollected that when Nelly (as her mother called her) was about 16 years of age she was a good deal among the Jewesses and she obtained a place to clean and mind chambers somewhere by Lewman-street for a rich old gentleman. When she heard that there was no one there but this old gentleman she took her away. He then came, and sadly wanted to persuade her to let her go back; but she told him that she should positively refuse to let her go any more. Her daughter always told her most positively that she was really married, and to a gentleman. She always in speaking of him called him Charles. Her daughter at one time had splendid clothes, and she frequently spoke of the tours she had been with her husband, especially of her enjoyment when travelling up the Pyrenees. Her daughter used to say she had one child born while she was abroad, but it died.

October 23, 2011

Hampstead murders – Part seven

from the Illustrated Police News, 29 November 1890

At the Old Baily yesterday morning the trial of Mary Eleanor Pearcey for the murder of Mrs. Hogg and her baby was commenced before Mr. Justice Denman. Mr. Forrest Fulton and Mr. Gill prosecuted; Mr. Hutton defended. Mr. Grain watched the case on behalf of the husband.

The prisoner in a clear voice, replied to the charge, "Not guilty, sir."

The prisoner was accommodated with a seat in the dock.

Mr. Fulton, in opening the case, said the murder, took place on the evening of 24th of October, at 2 Priory-street, Kentish-town. The deceased woman was thirty-one years of age and her baby eighteen months. She lived with her husband at the Prince of Wales-road, Kentish-town, the husband being employed by his brother in the furniture-removing business. The husband became acquainted with the prisoner about five years ago, and there was no doubt that the prisoner was most passionately attached to him. He was in the habit of visiting her two or three times a week, and had a latch-key by which he could admit himself to the house. He had denied that there was any improper intimacy between them until after his marriage with the deceased; but looking at the letters which have been found in the possession of the prisoner that was a most improbable statement. Some of those letters, which were copies of letters sent by the prisoner to the husband, were read, and they were couched in the most affectionate terms.

REMARKABLE LETTERS

The first letter was as follows:–

2nd October 1888

My dear F.,– Do not think of going away, for my heart will break if you do; don't go , dear. I won't talk too much, only to see you for five minutes when you can get away; but if you go quite away, how do you think I can live? I would see you married fifty times over, yes. I could bear that far better than parting with you for ever, and that is what it would be if you went out of England. My dear loving F., you was so down-hearted to-day that your words give me much pain for I have only one true friend I can trust to, and that is yourself. Don't take that from me. What good would your friendship be then with you so far away? No, no, you must not go away. My heart throbs with pain only thinking about it. What would it be if you went? I should die. And if you love me as you say you do, you will stay. Write or come soon, dear. Have I asked too much? — From your loving, M. E.

P.S.–I hope you got home safe, and things are all right, and you are well.– M.E.

The next letter was in the following terms:–

18th November 1888

Dearest Frank,– I cannot sleep, so am going to write you a long letter. When you read this I hope your head will be much better, dear. I can't bear to see you like you were this evening. Try not to give way. Try to be brave, dear, for things will come right in the end. I know things look dark now, but it is always the darkest hour before the dawn. You said this evening, "I don't know what I ask." But I do know. Why should you want to take your life because you want to have everything your own way? So you think you will take that which no man has a right? Never take that which you cannot give–you will not if you love me as you say you do. Oh, Frank, I should not like to think I was the cause of all your troubles, and yet you make me think so. What can I do? I love you with all my heart, and I will love her because she will belong to you. Yes, I will come and see you both if you wish it. So, dear, try and be strong, as strong as me, for a man should be stronger than a woman. Shall I see you on Wednesday about two o'clock? Try and get away, too, on Friday, as I want to know if you are off on Sunday till seven o'clock. Write me a little note in answer to this. I shall be down on Monday or Tuesday in the morning, about 5 a.m.–So believe me your most loving, M.E.

That obviously referred (counsel said) to the fact that Mr. Hogg was contemplating suicide, and also meditating marriage with Phoebe Hogg. There were other letters found, which were undated, which went to show that affection existed between Mr. Hogg and the prisoner. The following was found in an evelope:–

Dear Frank,– You ask me if I was cross with you for only coming for such a short while. If you know how lonely I am you would not ask. I would be more than happy if I could see you for the same time every day, dear. You know I have a lot of time to spare, and I cannot help thinking. I think and think, till I get so dreary that I don't know what to do with myself. If it was not for your love, dear, I do not know what I should really do, and I am always afraid you will take that away, then I should quite give up in despair, for that is the only thing I care for on earth. I cannot live without it now. I have no right to it; but you gave it to me, and I can't give it up. Dear Frank, don't think bad of me for writing this. I hop your cold will soon go away. Hoping to see you to-morrow, with love from your loving and affectionate M.E.

P.S.–Don't think any one would know the handwriting.

October 22, 2011

The Hampstead Murders – Part six

THE SISTER'S EVIDENCE

Martha Styles, who said she lived at Egbam and was a dressmaker, knew Mrs. Pearsey, but never visited her. She saw her in February last. The deceased was sister to witness. She last saw deceased on Thursday, at ten minutes past six in the evening, at the North London Finchely-road station. Witness was going home. She went with her sister to Albion-road where her niece lived, and going there the deceased produced a letter, and said, "I have received a note from Mrs. Pearsey," and she seemed very much surprised, because she had had nothing to do with Mrs. Pearsey since the previous February. The note was upon a piece of white paper and there was writing on it in pencil.

Martha Styles, who said she lived at Egbam and was a dressmaker, knew Mrs. Pearsey, but never visited her. She saw her in February last. The deceased was sister to witness. She last saw deceased on Thursday, at ten minutes past six in the evening, at the North London Finchely-road station. Witness was going home. She went with her sister to Albion-road where her niece lived, and going there the deceased produced a letter, and said, "I have received a note from Mrs. Pearsey," and she seemed very much surprised, because she had had nothing to do with Mrs. Pearsey since the previous February. The note was upon a piece of white paper and there was writing on it in pencil.

Did you copy the letter? — No, sir.

Tell us all about it. — There was no date and no address but "Mrs. F. Hogg." Then there was a word underneath, but I do not remember what it was. Inside, on the piece of paper — the letter did not come by post — my sister said a boy gave it to her — the words were; "Dearest,– Come round this afternoon and bring—-" I do not remember whether the word was "your" or "our little darling. Do not fail."

Was there any signature? — None.

How do you know it was from Mrs. Pearsey? — I have seen Mrs. Pearsey write. She wrote me down her address. This was in February.

Why did you conclude the letter was from Mrs. Pearsey? — Because about three weeks ago a boy brought my sister a note in the same manner. The boy gave her the note at the door. There was no signature to that note, but in it my sister was asked to go out and see someone who wrote it at a given place — a public-house, I think. When my sister got there Mrs. Pearsey crossed the road and spoke to her and asked her to go on an excursion with her to some seaside place. My sister told me this her own self.

The Coroner: When did she tell you this? — Witness: This was about a fortnight ago.

Do you know where the public-house was? — No; I have forgotten the name.

Anything more? — My sister was to go round and tell Mrs. Pearsey, as she did not decide then whether she would go or not.

Anything else? — My sister went and told her she would not go.

Anything more? – Yes; my sister said, strangely, with regard to her conversation with Mrs. Pearsey, "It was an empty house she was to go and look over with Mrs. Pearsey."

Where? — At the seaside.

How long was the visit to last? — It was only to be a day's excursion.

Did she say where to? — I think it was Southend, and she was to leave the baby in London with Mrs. Pearsey's nurse.

Who is Mrs. Pearsey's nurse? — I don't know.

Did your sister tell you she had consulted her husband as to the first letter?

No; he was not at home at the time.

Did she say she had any conversation with him as to the proposed trip to the seaside? — No.

What was done with the second letter? — I put it in the fire.

Why? — My sister told me to do so. She said, "I have only kept it for you to read, and now that you have read it I don't want it. Put it in the fire."

Did she say whether she was going round or not? — Oh, she said she certainly would not go.

What was it she said? — She said, "If she waits for me to go down she will wait a very long time."

Did your sister make any further observation to you with regard to the proposed visit to Southend? — Yes.

Have you told this to anyone before your sister's death? — Yes, my brother.

When? — Last Tuesday.

Now tell me what it was she said, using as nearly as you can her own words? — She said, "If I had gone to Southend no one would have thought of looking for me down there in an empty house."

She said that about a fortnight ago? — Yes.

Did she offer any further explanation of that expression? — No.

What did your sister understand? — She had suspicions of Mrs. Pearsey.

But why? Do you know anything more about their relations? We have hear something about some letters which Mrs. Hogg received about eight months ago. Was Mrs. Pearsey the medium for letters received at her house? — I don't think so.

Do you know why she should entertain suspicion? Had there been any unpleasantness? — Yes, when she left last February.

Now, tell us what occurred last February. Was she taken ill? — Yes.

Who was nursing her then? — Mrs. Pearsey.

Did you visit her? — I went up to see her one Sunday. From a letter which I received from another sister telling me of my sister's (Mrs. Hogg's) illness, I went down to see her. I found her very ill indeed. She appeared to be in very great pain, more so after taking her medicine. Her husband gave her the medicine.

She was attended by a medical man, was she not? They told me they had one in, but I never saw him. I afterwards went with her to my elder sister's.

Was there any unfriendly feeling between her relations and her husband? — Scarcely unpleasant feeling.

Perhaps the idea of her going away was that she would be better looked after among her relatives? We thought she would get more nourishment.

You had no suspicion of foul play? — Not then. It occurred to me after.

There was no suspicion at the time? — No.

Of course, her husband was away all day at business, and the only person left was Mrs. Pearsey? — No, he was not at work all the time. He was lounging about home part of the time.

Perhaps there were some considerations why she should leave the house? — Simply she did not have enough. She said she did not.

Did she quite recover? — She has never been so well since her illness last February.

When did you last see your sister? — Last Thursday.

Why did you go to Finchley-road station? What was the object of it? — I was going down to Richmond; my sister saw me off. My sister never complained of bad treatment — not exactly — but she was not happy. She told Clara Hogg that her life had been a perfect misery to her since Mrs. Pearsey entered the house. My sister told me she saw Mrs. Pearsey once when she called at her house to see someone, but they scarcely spoke. My sister had no feeling of jealously whatever with regard to Mrs. Pearsey. I scarcely believe that my sister received letter which she kept back from her husband. She only had letters from members of her own family.

THE NIECE'S STORY

Elizabeth Styles was the next witness. She said: –I am a nursemaid living at Albion-road, London, but my home is at Folkestone. The deceased, Mrs. Hogg, was my aunt, and I was very intimate with her. I have received no letters from her. I used to write her until her husband forbade me the house. I had no quarrel with Mr. Hogg until February. I went to see how she was getting on, and found her sweeping the floor when I thought her quite unfit to do so. I took the broom from her and told her to sit down. I also told Mr. Hogg that I thought he was not treating my aunt properly.

Elizabeth Styles was the next witness. She said: –I am a nursemaid living at Albion-road, London, but my home is at Folkestone. The deceased, Mrs. Hogg, was my aunt, and I was very intimate with her. I have received no letters from her. I used to write her until her husband forbade me the house. I had no quarrel with Mr. Hogg until February. I went to see how she was getting on, and found her sweeping the floor when I thought her quite unfit to do so. I took the broom from her and told her to sit down. I also told Mr. Hogg that I thought he was not treating my aunt properly.

Had she complained to you of his treatment? — Yes.

Had anything occurred to make things unpleasant? — Yes; things were very unpleasant. When I saw she was so ill I communicated with the last witness. During the time she was in her own home in February Mrs. Pearsey attended her.

Did you make any remark? — Yes; I thought she was not being properly attended.

Was Mrs. Pearsey a paid attendant? — I do not know. I remember writing a letter to the last witness stating that I thought my aunt was not being treated properly.

Why was that? — She had told me her husband was not treating her properly.

Had she any suspicion about Mrs. Pearsey? — Yes; she had her suspicions that her husband visited Mrs. Pearsey.

Did she tell you that? — Yes, sir.

THE CARDIGAN JACKET OWNED.

John Charles Pearsey, carpenter and joiner, living in High-street, Camden-town, deposed: I am a single man. I have known the person called Mrs. Pearsey since 1885. Her real name is Miss Eleanor Wheeler.

What is her age?– I should say that she was 18 or 19 when I first knew her. I know none of her friends and relatives.

Is it correct that you lived with her?– Yes.

Since when have you discontinued your visits?– Just over two years.

Have not you seen her during that time?– Yes; but I have not lived with her.

The witness was here shown the cardigan jacket which had covered the deceased woman's head and he said, "That belonged to me. I identify it by the pockets. For lighting stoves, I carry a box of matches, and this jacket was burnt by me."

Did you leave that in the possession of Mrs. Pearsey?– Yes, four years ago. Mrs. Pearsey had no means of her own; she told me that a gentleman was providing for her.

Did she ever speak about Mrs. Hogg?– Yes, she told me, some time ago, that Mrs. Hogg was a kind friend, and that they had been friends for a long time.

When did you see Mrs. Pearsey last?– I saw her last on Thursday morning. I had aoccasion to pass through the street and she (Mrs. Pearsey) was at the gate. I asked her why the blinds were drawn and she said she had a brother dead, 14 years of age, and that she was very much upset and worried, and did not know what she should do with herself; and she was making up mourning to go to the funeral on on Tuesday next. I have not found out whether her statement was correct.

Whe was it Mrs. Pearsey said Mrs. Hogg was a kind friend?– About three years ago. I have seen Mrs. Hogg once. I know her by the photograph I have seen of her. She was then introduced to me as a young friend. During the time I was living with Miss Wheeler she used to visit at Hogg's shop. Hogg was a small provisions dealer.

Then you knew she visited there?– Yes, and I also had my suspcions. When I first saw Mrs. Hogg, Miss Wheller said, "That is the lady who is going to marry Mr. Hogg." I recognise the thick gold ring produced as the one miss Wheeler wore on her finger. The other ring, the common one, is one which she used to wear. I purchased neither of them. She told me that a gentleman friend who used to visit her gave her one of the rings. A geltman used to visit her on Fridays.

The coroner said there had been a suspicion that some mysterious individual had been connected with the matter. If that person would like to come forward he would be very happy to hear him. It might be to his advantage and clear up any doubt.

THE INDEPENDENT GENTLEMAN

Charles Crichton, called by the police, said he was of independent means, and resided at Northfleet, Kent. He had known Mrs. Pearsey about three years. The last time he saw her was on Monday the 20th Oct, at her own house.

Detective-inspector Miller here handed in a letter.

Mr. Crichton said he received that letter from Mrs. Pearsey on Friday morning (the day of the murder).

The coroner perused the letter privately, and then remarked to the witness, "This is simply a letter personal to yourself. There is nothing in it."

The Witness: "It is simply one of many such."

The coroner remarked that the letter appeared to have been written on the 23rd Oct., and referred to the witness's help. It also stated that she was "going up to Prince of Wales-road" after finishing the letter.

Mr. Crichton continuing, said that he knew her as Mrs. Pearsey, and she represented herself to him as married. He had seen a photograph of Mr. Hogg and his wife in a book she had. The were represented to him as friends of hers. He knew nothing at all about the matter. He could account for his movements every day from Monday, the 20th October, till the present time, and his brother was present to corroborate him.

Detective-inspector Banister said there had never been any reason to suspect Mr. Cricthon.

MRS. PEARSEY'S ACCOUNT

"I have not told a lie. Mrs. Hogg did come here at six o'clock, and asked me to lend her two shillings and to mind the child. I told her I could not lend her the money as I had none, and I could not mind the child as I was going out. I told Clara Hogg about it, and she advised me to say nothing about it, as it would be such a disgrace if people though her husband kept her short of money." Afterwards the prisoner said," I do not enjoy very good health. On Thursday night when I came home my nose bled violently."

FELLOW LODGERS AT PRIORY-STREET

Sarah Butler, wife of a labourer occupying the second floor of 2, Priory-street, gave evidence, as also did her husband, of the presence of a bassinette perambulator in the passage of that house last Friday evening, when Mrs. Pearsey cautioned them not to knock against it in the dark. Mrs. Butler said she had seen the perambulator there twice before when Mrs. Hogg had called. Mrs. Pearsey had always told her that Mrs. Hogg was her sister-in-law and that Mr. Hogg was Mr. Pearsey.

OTHER WITNESSES

Mrs. Edwin Hogg (sister-in-law of the deceased) recollects that Mrs. Styles had complained at the time (of Mrs. Hogg's illness) of the way in which her sister had been cared for. The deceased was so suspicious that on one occasion she refused to touch a custard which she had taken her, fearing that someone had tampered with it. On the other hand, she had a dread of doctors, and on the Sunday before she left for Mill-hill positively declined to see a medical man.

THE CORONER SUMS UP

The coroner stated that the evidence in the case was circumstantial, and it was for the jury to say whether there was any reasonable doubt in their minds that the woman Pearsey did not kill Mrs. Hogg. Had a prima-facie case been made out against her which would justify her being sent for trial?

It was clear beyond doubt that Pearsey had a strong attachment for the deceased's husband, and it might be that she wished to get the wife out of the way so that Hogg and she might enjoy more unrestrained intercourse, or perhaps she entertained the hope of becoming the second Mrs. Hogg. In the case of the child, the evidence was not so strong as in that of the mother but it seemed plain that it was with the mother at Pearsey's rooms on Friday evening.

The jury, after a very few moments' deliberation returned a verdict of "Wilful murder against Mary Eleanor Wheeler, otherwise Mrs. Pearsey," both in the case of the deceased woman and her child.

October 21, 2011

The Hampstead Murders – Part five

HOW MR. HOGG MET MRS. PEARSEY

HOW MR. HOGG MET MRS. PEARSEYIn an endeavour to clear up the mystery of Mr. Frank Hogg's card-case, which was found in a bonnet-box at Mrs. Pearsey's house, and to obtain the truth as to the ring which was found on her finger, a reporter saw Mr. Hogg before the inquest. With regard to the card-case, Mr. Hogg said that it was an old one which he had used 10 years ago when he used to go to the Polytechnic. He had not used it or the cards since. He had no idea whatever how it had come into Mrs. Pearsey's possession. He could not say whether he had given it to her or not. Questioned as to the ring, Mr. Hogg said the one found on Mrs. Pearsey's finger was not his wife's. His wife's was a much heavier and more massive ring. Mr Hogg readily volunteered to account for his time on the evening of the murder. At times, however, he was much affected. He said, "God knows I never thought of anything like this. What astonishes me is that my wife was there at all. She never mentioned Mrs. Pearsey's name to me since Christmas. They used to be on visiting terms, and fairly intimate up till last Christmas. Then we had some family differences. I was not aware that my wife had spoken to this woman since then.

"You were telling us about how you first met her. How many ears ago was that?"

"Somewhere about five years back. She was then certainly supposed to be a married woman. We knew her first merely as a customer at what was then my father's shop, in King-street, Camden-town. She was then known to us as Mrs. Pearsey. We were only the merest acquaintances. She never entered our King-street house, only coming to the shop as a customer. We have been living here since last March, 12 months, and after we had been here some six weeks, she called on us, as a great many of our old customers had done. We did not know her husband, and in fact, knew very little about her at all. The deceased probably had not been at her house more than four of five times, and then it was merely a call. I never heard my wife and her use a cross word to each other. It was last February that Phoebe was ill, and then Mrs. Pearsey came here and nursed her for a few days. My wife was very reticent about things. For instance, if she had been out for a walk during the day she might not mention it at all, and if so would hardly ever say where she had been. She frequently left little notes such as the one she left on Friday when she was going out."

"Somewhere about five years back. She was then certainly supposed to be a married woman. We knew her first merely as a customer at what was then my father's shop, in King-street, Camden-town. She was then known to us as Mrs. Pearsey. We were only the merest acquaintances. She never entered our King-street house, only coming to the shop as a customer. We have been living here since last March, 12 months, and after we had been here some six weeks, she called on us, as a great many of our old customers had done. We did not know her husband, and in fact, knew very little about her at all. The deceased probably had not been at her house more than four of five times, and then it was merely a call. I never heard my wife and her use a cross word to each other. It was last February that Phoebe was ill, and then Mrs. Pearsey came here and nursed her for a few days. My wife was very reticent about things. For instance, if she had been out for a walk during the day she might not mention it at all, and if so would hardly ever say where she had been. She frequently left little notes such as the one she left on Friday when she was going out."

AT THE INQUEST

Frank Samuel Hogg, the husband, was the first witness called. He was much affected during the preliminary questions but soon mastered himself, and replied in an audible voice to the interrogations of the coroner. He said: "I saw both my wife and daughter alive and well on Friday morning. They were both seen by me at nine o'clock on the morning when I was going out to work.

What time did you return? — At 10 o'clock at night.

Did you inquire from the people in the house when you came home about your wife? — No. I made no inquiry because I thought it was all right.

Was there any agreement between you as to her going away? Yes; if she got a letter saying her father was worse she was to go at once to Chorley Wood.

Did she leave you any message? — Yes; she left a note saying, "Look in the pot. I shall not be long. 3.10″

What did you next do? I did nothing, because I thought perhaps my wife had met her sister Emma at the Kentish-town railway-station.

Did you go to sleep that night? — I lay down in my clothes on the bed; but I did not sleep much, and got up about six o'clock on Saturday morning. I went down to my brother's to work about 20 minutes past six. I worked on in the stables, helping to get the horses out, and then I went over to my brother's house. I said to him, "I have lost the missus and little one." He said, "What, gone away?" and I said, "Yes." He said., "Don't you know where she has gone to?" I said, "I expect to Chorley Wood because her father is so ill." I said I expected to find a letter waiting for me at home. I went home about eight o'clock. I asked my mother if she had a letter and she said, "No. Can you understand it?" I said, "Well, the telegraph office don't open till eight o'clock." I waited very impatiently, and about half-past eight, I really began to get concerned, and thought something had happened. I asked my sister to run down to Mrs. Pearsey's.

Who is Mrs. Pearsey? Is she a friend of yours? A neighbour?" — She was a friend.

Did you know Mr. Pearsey? — No. I have seen a person called Mr. Pearsey, whom I believe to be her husband.

Well, what did you do? — I asked my sister to run down to a neighbour's with whom I was well acquainted to see if my wife was there, though I did not think she was there. When my sister came back I met her in the street and she said to me, "Is she home?" I said "No. I am going down to Fred's" I went there and returned to my home, when I said to my mother, "I am going to Chorley Wood." I went there.

Did you get any news of your wife? — No; I went back home, and was surprised to find neither my wife nor Mrs. Pearsey at home.

Did you expect to see Mrs. Pearsey? — Yes. Because I had asked her to go and see if the perambulator had been sent to the railway station.

You had a perambulator? — Yes; and my wife went out, taking the child in it. I left home about 20 minutes past 12 on Saturday and when I returned my mother was seriously upset. She said to me, "Don't upset yourself, but look at that paper," handing me the newspaper.

And you saw in it an account of the death? — Yes.

Did you think it was your wife? — I felt sure of it.

What did you do then? — I came to the mortuary between two and three o'clock, and saw that the body there was that of my wife.

Did you see Mrs. Pearsey? — As I left home on Saturday morning I saw her and said, "Has that perambulator been booked?" and she said, "No, it has not." I have known Mrs. Pearsey for about four years. We were on friendly terms. At Christmas time my wife and I stayed at Mrs. Pearsey's house for two days.

Did you see Mr. Pearsey then? — No.

Did you have any dispute with Mrs. Pearsey? — (Under a mistake the witness proceeded to describe a dispute with his wife.) About eight months ago I had a dispute with my wife. She was always writing letters when I came home, and would not let me see them, and insisted that I ought to see them. Then one day she was reading a letter when I came home and would not let me see it, and I said I ought to see it. That led to our separation for one night.

May I take it that since then you and your wife have lived happily and comfortably together? — Perfectly.

THE INTIMACY WITH MRS. PEARSEY

Have you visited Mrs. Pearsey since? — Yes

Very frequently? — Perhaps two or three times a week.

Was the object of your visit anything special? — Nothing special — (hesitating) — I must admit that I was intimate with her. I will admit it.

It is best to tell the truth. Had your wife any suspicion of this? — I believe not, sir. May I just state how it was that Mrs. Pearsey and my wife did not visit? At the time we had the dispute about my wife's private letters my wife said, "I will have them. I will have them sent to Lizzie." Lizzie Styles is my niece. I said, "Then Lizzie shall not come here, nor shall you go and see her." When our disagreement was made up she said, "If none of my friends come, none of yours will." I said, "No; only when they are invited." We agreed that there should be only mutual invitations. My wife never went to Mrs. Pearsey's after that.

Did a quarrel exist between Mrs. Pearsey and your wife? — They had not a cross word that I know of.

You say this was eight months ago. If it is true what we hear that it is probable your wife visited Mrs. Pearsey… — I can't understand it.

Do you know that she had been in the habit of visiting her during the last eight months? Has she, to your knowledge, been visiting Mrs. Pearsey? — No; never to my knowledge, and never since the time of the dispute between me and my wife.

Is there anything else that you would wish to tell us about this matter? Was she fond of her child — Oh, yes (sobbing).

In your relations with Mrs. Pearsey, has your wife been the subject of conversation with Mrs. Pearsey? — She has a very often asked after her.

Did Mrs. Pearsey manifest any enmity toward your wife? — She always spoke kindly about her.

How long have you been married? — Two years.

You were known to Mrs. Peasey probably before you were married? — I have had known her five years.

Did you think your wife discovered that you were intimate with Mrs. Pearsey? — I do not think she did.

What object could your wife have in going to see Mrs. Pearsey? — I haven't the least idea (crying bitterly).

LOOKING FOR HIS WIFE

Did you go to look for your wife at Mrs. Pearsey's? — Yes, on Friday night about 10 o'clock. My wife never had a cross word about Mrs. Pearsey, and in my wonder and excitement I went there.

Did you see her? — No; she was out.

Did you hear that Mrs. Pearsey had written asking your wife to go round and take the child? I have heard it from a gentleman in court but I did not know it myself before. I never had a quarrel with my wife about Mrs. Pearsey. If she ever called at my house it was without my knowledge. My wife never showed any suspicion that she knew I visited Mrs. Pearsey. I was never separated from my wife, but she stayed at her brother's a few days because she was ill at the time. We were on perfectly friendly terms then. That was in February.

Who nursed your wife in her illness? — Mrs. Pearsey.

Why did she go away? — Because I insisted upon seeing the letter which she had had. Her friends wished her to go to her brother's and she went. She got quite well the time Mrs. Pearsey nursed her. There was nothing at all in the nature of a disagreement between my wife and Mrs. Pearsey. They appeared to agree together very well.

You had no thought that your wife suspected your visits to Mrs. Pearsey? — No, I had not. She went to my brother's last February or March at the wish of her friends.

Do you know why they wished her to go away? — No.

Was it because they objected to Mrs. Pearsey being her nurse? — No, certainly not. After my wife went away she was soon well again.

Did your wife send for Mrs. Pearsey? — No, she came quite unexpectedly.