V.R. Christensen's Blog, page 2

October 1, 2021

A Ghost Story for the Ages

The summer of 1816 was a gloomy one. The devastating eruption of Mt. Tambora the year before had sent thirty-five cubic miles of debris into the air, which, by the following year, had made its way around the globe, casting a pall of darkness over the rest of the world. On the continent of Europe, storms were plentiful, skies were dark, and the rain fell for days on end.

Toward lake Geneva a group of poets and writers and fan-girls travelled, all for different purposes, but eventually converging at a villa rented by Lord Byron on Lake Geneva. Byron, travelling in an enormous Napoleanic carriage pulled by six horses made his way at a snail’s pace, was last to arrive, though he had been the first to leave. Traveling in the carriage with him was his personal physician John Polidori.

It was Claire Clairmont who led her party toward the spot where Byron might be found. Claire and Byron had been lovers for a period of some two months before Byron, bored of her as he inevitably grew of every amorous pursuit, had quit her with the same relish he had quit England and its crowd of debt collectors who had, the moment Byron departed, stripped his apartment bare of anything worth selling. Claire, it may be supposed, felt Byron owed her as he owed his debtors. She was pregnant, after all, and though she knew he would not receive her in Geneva, she knew he would not refuse an introduction to the celebrated poet with whom her Mary Godwin had recently eloped. Percy Bysshe Shelley was a rising star in the literary world, having achieved international acclaim for his poem Queen Mab. Claire managed to corner Byron as he was returning from a boating trip with Polidori and forced the introduction of the two poets. Byron happily received the introduction to Shelley alone and then and there invited him to dine that night, excluding Mary and Claire entirely. A jealous Polidori joined the men, though apparently reluctantly and was left to record the event, describing Shelley as bashful, shy, and consumptive, none of which was actually true, though Shelley was certainly intimidated by Byron’s talent and productivity.

Byron and Shelley immediately became close friends. Visits were paid between them while Percy and Mary stayed at a hotel on the other side of the lake from Byron’s villa. Byron rowed to visit them nearly every evening, despite howling winds and driving storms. After the weather threatened to sink his boat, he decided to take a villa closer–with in a ten minutes’ walk–from Percy and Marry.

As the poor weather persisted, their evenings were spent together reading, until, on one occasion, Byron turned the subject to ghost stories, acting them out as he read them and inflecting them with all the emotion and power inherent in his commanding presence and theatrical delivery, all the while his audience; Percy, Mary, Claire, and Polidori, did their duty by feigning fear and excitement (though one account describes Shelley in a fit after imagining himself to have seen two ghostly breasts appear from the darkness to stare at him condemningly). Byron, so pleased by the response to his reading, set his guests to a challenge: they would each write a ghost story for the delight and fright of each other. It was a sort of contest, to which each of the participants agreed enthusiastically and each immediately set upon the task of thinking up a story.

Byron had no trouble finding a place to start and wrote a full eight pages before growing bored and giving it up. Shelley, too, made an early start and began writing about his early life, but he, too, gave up the effort not long after he had begun it. Polidori, too, had an idea, one that Mary did not think much of, about a skull-headed woman who was cursed for having seen something she oughtn’t have. Finding such little encouragement from his companions, all of whom (save for Claire, of course) had some significant literary background, even if Mary’s own was that of her famous parents and not–not as yet–as a result of her own fame.

Mary, for herself, struggled to come up with an idea. Among the topics discussed between the party on those gloomy summer evenings were vampires, grave-robbing, and reanimation by means of electricity, including the scientific work of Luigi Galvani who had conducted some research on animal corpses in which he had demonstrated how, by applying electricity (via electrical storms), one could produce muscular contractions. The first spark of an idea came to Mary in consequence of a conversation between Shelley and Byron in which they were discussing “the nature and principle of life”, which recalled her once more to those ideas of Galvanism. She next began to wonder if a whole corpse might be re-animated and if, following that, a “a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.” She carried the idea to bed with her and there laid awake, allowing her ideas to form and develop until, at last, they conspired to produce a vision so vivid it was like a waking nightmare that she could not shut out. She saw the figure of a man “kneeling beside the thing he had put together … the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.” The creator of this monster, terrified by what he has done, then flees, hoping that the spark of life will extinguish itself. But doesn’t.

The idea so terrified Mary that she tried to escape it, forcing herself to think of other, more pleasant things. There was no sleeping now, late as it was, and though she was frightened still by the ghastly ideas she herself had invented, she had a sudden realization. She had thought of her idea for the ghost story Byron had challenged her to write.

Perhaps it was to her good fortune that Shelley and Byron went on a boating expedition for the next several days, leaving Mary, then only 18, to write alone and undisturbed, and so it was that she had made a good start before Shelley returned, at which time he read what she had written so far and gave it a favorable review, encouraging her to continue her work on it.

In December of 1817, the book was ready for publication. Its reception was mixed, but when Sir Walter Scott gave it a favorable review, the world began to sit up and take notice. Byron, of whom it has been said thought little of all women and if he loved any at all it was only his sister, Agnes, grew to admire Mary very much, and, long after Shelley died, she and Byron continued to have a friendship of mutual respect.

Polidori, eventually used and abandoned by Byron, would go on to write the Vampyre, one of the very first and seminal fictional accounts of such monsters, inspired by Byron himself.

It’s hard to believe that, after a fraught elopement (Percy was still married when he took Mary away), the death of his wife, their marriage, her husband’s fame, her literary accomplishment, the birth of four children and death of three of them, that the couple were only together a total of eight years (almost exactly) before Percy drowned in a boating accident in 1822.

Percy’s body was burnt on the beach of the Ligurian Sea where his body washed up 10 days after his drowning. It is said his heart did not burn and was carried back to Mary, who kept it in her desk until her death 30 years later.

Percy’s body was burnt on the beach of the Ligurian Sea where his body washed up 10 days after his drowning. It is said his heart did not burn and was carried back to Mary, who kept it in her desk until her death 30 years later.In May of 1824, Mary began a new novel entitled The Last Man. The following day, she learned of the death of Lord Byron. She was alone, save for her only surviving child, and she felt it.

The years that followed ushered in a societal and moral revolution. The death of King George IV and the succession of William IV marked a moment in time where people, feeling themselves exhausted by the debauchery of the long and bloody Regency Era, and in preparation for Victoria’s tight-laced reign (she was only eleven at the time, but those responsible for her training knew precisely what to prepare her to represent), made a conscious decision to turn common mores in the direction of moral retrenchment. Mary, wishing to give her son the security and respectability denied both her and Percy, set out to rewrite Percy’s story. Brought up by sexual revolutionaries and feminists herself, she had, and quite ironically, found herself tossed about on the whims of the stronger personalities around her. Now it was her turn to set the tone, and she could only do that by rewriting the narrative of the past. She did the same for Byron, editing his letters and journals and excising the bits that would not stand up to modern scrutiny. Of course we know today what Byron and Shelley were about. Even in their day they took things to extremes. It’s nevertheless interesting to consider the lessons that might be gleaned from these lives that burned far, far too brightly, and at the expense of the lesser lights–if one could consider Mary as such. The men around her certainly did. At 18, her creation of Frankenstein’s monster ought to have set her up as a genius of her day. But her book was, in many ways, a lamentation, a cry out to the world that the battle her parents had fought for the freedom they supposed was preserved to them only by shunning tradition and societal norms had been fought at the expense of the children they bore together. Mary was not only a casualty of her time, but of the people, men and women alike, who rowed the oars in the boat she had been set in, ultimately to sail in alone.

I’m not sure if her story, after all, is not more haunting than the tales she wrote.

***For further reading on this subject, I highly recommend the book The Monsters: Mary Shelley & the Curse of Frankensten by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler

August 21, 2021

On Manifestation part 1

Last month I talked about how I often take the issues that are troubling me and work them out in a fictional medium, but the reverse is also true. Sometimes I write things, and then those things seem to manifest in the real world. At the time that I began writing Absinthe Moon, there were the hintings and murmurings (at least amongst the Conservative crowd that then surrounded me) of political controversies and conspiracies. When have there not been, right? But I feel like much of what was proposed as possible during the Obama administration actually displayed itself as a real possibility during the administration that followed. Add to that a pandemic and climate change, and the world feels very much like a dystopian end-times novel about now. Except maybe more boring.

Foremost to my mind, and frankly the one that gives me the most internal disquiet, is the theme of vaccinations. Of course the controversies surrounding the issue are not new, but never has it been so forefront in world events. First let me say that I am not a anti-vaxxer. I firmly believe in the benefits of preventing avoidable death and illness from common diseases. What concerns me is the for-profit nature of the medical healthcare industry. But even that is not why I wrote vaccinations into the story. Really it was just a convenient way of saying that this culture of New Londinium and the patriarchal and elitist/ablest way in which it is run and maintained, is impregnated into the psyches of everyone who lives there. Even for those in the know, even for the most self-aware, prejudism, ableism, misogyny, racism are truly engrained into our paradigms. We can we are not any of those things, but until we have stood in the shoes of someone who has been injured by these things, we really can’t understand in what ways our mindsets are unnecessarily or unequally biased towards our own best interests. Simply saying you don’t agree with these things isn’t quite enough. It’s necessary to really examine them and consider in what ways we can do better.

But really the theme of vaccinations is multi-layered. There is also the idea of being forced to inject or ingest or metabolize something we didn’t intend to and would not have chosen to do on our own. I think of the “mickeys” slipped to unsuspecting women in bars, or the “one last drink” method of liberating a woman’s mind, quite against her better judgment and interest, even if it isn’t absolutely against her will, with any mentally lubricating substance so that, if she isn’t more likely to say “yes” at the end of the night, she is at least less likely to say “no”. Only what happens if this is not just the norm within a dating scenario, but the government and society as a whole is implementing such a device on the unsuspecting? I mean, if a power has the opportunity to control everything that is put into you for the sake of their own profit, then why wouldn’t they? Right? And it’s not that I totally believe this is happening, I just think it could. And what if?

Are these inoculations, in the way that they are set up in Absinthe Moon, a metaphor for rape? Possibly. Are they a metaphor for power and domination and control? Definitely.

On a different topic, I had to laugh when I wrote about the Warehouse Conservatory as a means of ensuring that the Resistance has uncontaminated food, and then just weeks later, the city where I live announced the construction of a state-of-the art indoor farming facility. That, to my mind, is really cool. Now when will be see the waste-to fuel plants implemented? Of all the things I invented in this book, the Great Forge and its technology was not one of them.

The discoloration worn by the citizens of New Londinium was intended to be a metaphor, of course, for the issues of prejudice surrounding race, which topic has certainly been thrust into the spotlight in the last year or so. It’s also a statement about cultural attitudes toward beauty and the intersectionality between ableism and elitism. It’s also, in a way, a revisitation of themes Oscar Wilde addressed in the Picture of Dorian Grey (which book I love, by the way.)

There are many other themes that either seem to have risen to the forefront of the cultural stage since I wrote this book, or which, perhaps, I have only become more aware of, and I’ll add to the list as I think of further examples.

In my most recent read-through, during the final proofing process of the paperback for Odessa Moon, it struck me as significant that the topic of “male likeability” is as prominent in the book as it is, when the topic seems recently to have been introduced, at least on social media, into the dialogue of those presently reassessing our cultural paradigms (a really valuable thing, I think). And I’d just like to add here that if you are one who doesn’t like the tone of these self-reflective cultural reassessment that is going on, (though if you do feel that way, I doubt very much you’ve read this far) then let me just say that the reason I think the conversation is important is, in part because it teaches us in real time how to adjust the way we think about our culture and our times and how we communicate about them. Nothing has been decided except to say that we know we can do better. What that better will look like is, as yet, undecided. Hence the need for conversation.

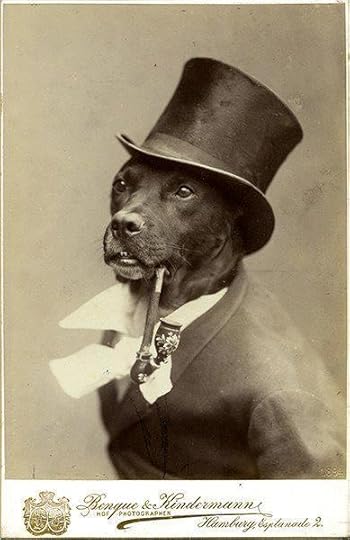

This is a demon.

This is a demon.I had never actually given it a lot of thought before, how history and the advancement of women’s rights has changed the dynamic between men and women so that we no longer marry because we “need” men in the traditional sense. When I was born, women had to have a husband’s permission to own a credit card, to make medical decisions about herself, to engage in a legal transaction, to have enough money to live. So many women married simply to survive and to have their material needs provided for. Now we don’t even need men to legitimize sex and childbirth. That need negated a lot of the character traits that women now required to be tempted into a commitment. If I have to marry to survive, probably I’m dreaming of true love, but, failing that, I’ll accept someone I don’t hate. It also means that the possibility of being alone for the rest of my life is very real because I’m quite happy doing for myself. What I need in a partner is kindness and affection and forthrightness and a good sense of ethics and fairness. Men now have to work to be likeable. And truly, I don’t mean to say that men generally are not, but there is a lot of that mentality out there still that men can do as they like, they can be shitty and and unkind and throw their privilege around, and women just have to take it. I know, I’ve been in the dating world these last six years and I’ve seen what’s out there. There’s a lot not to like. But I’ve also met some really wonderful men who are taking these dialogues seriously, who are examining themselves and their place in the world and adjusting accordingly. And of course there are, and have always been men, who have championed more equity in our societal constructs, in our systems, and even in relationships. Those are the men I write about, after all.

Can I manifest one of those, please?

August 5, 2021

On the Domestication of Humans

As a Sagittarius rising and a Myers-Briggs INFJ, I’m fascinated by the idea of discovering my true self, the person I was before the world changed me. In yoga we talk about this a lot. In fact that’s one of the many functions of yoga, to reunite you with your innermost self, your truest self (that is, in fact, what the word “yoga” means). In consequence, I’ve been giving a lot of thought to what it means when people respond to the parts of you they don’t like. That is, after all, why we fail to be our true selves, because we are ever and always trying to present to the world the parts of us—and only the parts of us—that are most palatable. We shove everything else aside and hide it in locked rooms inside our own psyches. Such is the source, at least according to some psychologists, of neuroses (see Marie-Louise von Franz’s The Problem of the Puer Aeternus).

It is often the case that I take the issues that conflict me the most and pour them into my novels. Doing so offers me the opportunity of placing the issue outside of my own mind where I can look at it and examine it in a little more detail—or at least from another perspective. I seem to be doing that now as I work tandemly on Guileless and Fearless. The first is about a young woman who is intent on challenging the limits of her own understanding. Growing up with four brothers, she is constantly aware of what it is she is missing out on in the way of education. At the same time that her father manages those limits, he also berates her for what she lacks. Her brothers think of her as silly and trivial and without a mind of her own. She has lots of opinions, that’s not the problem. Or maybe it is exactly the problem, for it’s the opinions they object to. Opinions without the facts to back them up, as we know, make up a great deal of the fodder of debates these days. But also, sometimes, it’s not what we do or don’t know that’s objectionable, but simply that we have opinions that challenge others. That there ought to be more than one voice in a marriage, more than one voice in a family or an institution, whether its religious or civic or commercial is something most of us would not debate. And yet … there are lots of people for whom the threat of losing the power of consensus feels extremely threatening.

In Fearless the heroin is not “accomplished” enough to please those who have stewardship over her future (or soon will have, at any rate), and yet she does have talents, we all do, but they are those that aren’t easily shown off in a ballroom or at a dinner party. She can play a little, sing a little, paint a little, sew a little, but she is a remarkable storyteller. Anciently, and even in today’s world, that’s a laudable skill, but at that time, it had no real use. It did not prepare her for marriage, did not prepare her to entertain, and offered nothing to the improvement of her domestic life. If she were a man, it might be a marketable skill, but a marketable quality in a woman was something to despise in the Victorian Era.

And what about now? There’s this huge, erupting conversation about what is acceptable for some people to do and not others. The hypocrisies, for instance, in what men can get away with (“he didn’t know what he was doing; he was drunk”, “boys will be boys”) versus what is acceptable in female behavior (“she had it coming”, “what did she think was going to happen if when she drinks/dresses like that?”) run rampant in our subconscious paradigms. While I find the disparity heartbreaking, I find the conversation (that we are having it) fascinating.

During my yoga teacher training, one of the books that was required reading was Don Miguel Ruiz’s The Four Agreements. Ruiz talks about domestication as the training we receive as children regarding how we are expected to interact with the world. We say “yes, please” and “no, thank you,” we sneeze into our elbows and cover our mouths when we yawn. We drive on the right side of the road, and we don’t take things that don’t belong to us. We use utensils when we eat (mostly) and refrain from kicking and hitting. And while all that is useful and even necessary, there are other things that are not

I’ve spent many years being indoctrinated with the idea that the reward for good behavior is the approval of others. Having been raised by an alcoholic father, I fall very firmly into the co-dependent category of human behavior and existence. I know how to be subtle. I know how to play small (despite the fact that I’m nearly 6′ tall). Religion was my friend because, as someone who is overly concerned with being a good person, I had this convenient checklist, and if I did all the things, that meant I was a-ok.

The problem comes when you finally take the mantel of responsibility upon yourself for trying to sort out who you are. Those who held the ropes and the rule books up to that point will have something to say when you threaten to step out of line. Those shame words and their accompanying narratives are used to put us back in place. Things like, “if you’re angry you’re not happy”, or “you’re being judgmental”, or “she’s gone off the deep end”. Think about it: Why do we have lawns? Why are houses only painted in solid colors and not in stripes or plaid? Why are some colors suitable for automobiles and not others. Why is it not o.k. to sing in public? Or to dance? Why are men supposed to have short hair and women never supposed to have tattoos?

Life is bizarre, and, truly, so many of the rules do not even make sense. But rules keep ups predictable, as do boxes and categories and judgments. We are all living in a state of fear, pretending we have it figured out when we don’t.

None of us has it figured out.

I was also taught that happiness looks a certain way, and if we are not happy, it’s a judgment upon our righteousness, on our worthiness, on the value of our existence. What’s interesting is that I’ve learned of the value of emotions and not just the “nice” ones. The value of anger, for instance, to inform you when a boundary has been crossed; the value of grief to help you get in touch with the well of emotion all around you (and the support and connection that brings); the value of fear to show us how to survive and to teach us how to value what is most precious. All of these emotions can be misused; of course they can, but the healthy expression of them is not something we should shame. But we do. Toxic positivity is real … and it’s unhealthy. Not only is it disrespectful of people who are struggling with depression, or loss, or any of a million other obstacle that may very well be no fault of their own, it invalidates the complexity of the human experience.

THERE ARE NO BAD EMOTIONS. Though there are certainly improper ways to act out on those emotions. Emotional intelligence is to everyone’s benefit. I think what the last few years has taught us is that too may people (particularly in the U.S. where the rate of trauma is so high) lack empathy. Sorrow, grief, and anger, are inconvenient emotions. It’s much easier to shame someone into the appearance of complaisance than to actually sit with them and help them sort out what it is they are feeling. Heck, we can scarcely sit sill with our own emotions! There are real problems in the world that are not going to get better by watching the news. That doesn’t mean we need to be upset by them, but we need to be willing to search inside for or own unique gifts and find the ways in which we can contribute. Neither is it realistic to expect that we are doing anything other than betraying ourselves when we sit by and smile and nod along when someone does something harmful or when our boundaries are betrayed. Such is the exact opposite of self-love.

I’m a passionate person, and while that’s not everyone’s cup of tea, I actually really like that about myself. It gives me the energy and motivation I need to write, to work for a purpose, to try to make the world a better place. It gives me the hope and courage to love, even after I have been disappointed and hurt. It is the joy in my existence, the energy that keeps me moving forward. It’s why, despite the difficulties and hardships of the last year, I have so much to live for and so much work to produce. And I have been.

I’m at a point in my life where I believe that the purpose of life is to heal from our traumas and find our true selves so that we can rise above hardship and offer our unique talents to make the world a better place. The more I’m allowed to express myself, the more I’m able to respect my own boundaries and maintain them, the more I am able to share who I am and who I am becoming with the world, the happier I am. But that journey does and should look different to everyone.

Blessings, and I’ll be back at the end of the month with some more fascinating research.

June 28, 2021

A Suitable Education for Girls

In an age when a woman’s greatest responsibility was to marry and bear children, education largely centered around the preparation for those roles. Working class women learned from their mothers or from other working class women how to ply their trades, with maybe some reading, writing, and maths thrown in, with focus on those skills that would allow them to supply for the necessities of the home.

For women of more means, the daughters of gentlemen, a governess was often brought in to offer a rudimentary education in Latin, Greek, etiquette and social graces, but the focus was on “accomplishments”, those subtle skills and charms meant to entice a man to consider what she, as a potential wife, would add to his home in the way of charming and entertaining their social peers. Music, drawing, painting, flower arranging, singing and dancing, were the aspiring qualities to be obtained by the “angel of the home”. And some accomplishments were given higher rank than others.

The subject of education has been a subtle focus of my own thoughts as I have been working on the Less is More Series (but also, in a smaller way, on Absinthe Absolute and the role of women at the Absinthe Moon, including the necessity of providing husbands to the city’s Chosen sphere). In Fearless, our heroine is considered to be a woman who has neglected to become truly accomplished. She is reluctant of society and rather than peacocking her talents for other approval (and judgment) of her peers, she would rather focus her attentions on more fulfilling pursuits, like that of being a suitable companion to her aging father, and of her true passion, storytelling. In Guileless, the focus of Antonia’s plight is on education, and how she longs to study those things her father, a former educator of young men, supplies to her brothers. She’s considered silly and unintelligent. The desire of the men in her family is that she be agreeable and free of the burden of opinions, which will only serve to vex her future husband and risk the stability of her own mind and sensibilities. Such were the arguments of the men around her, and, at least in many quarters, the men of that day.

By 1840, arguments began to arise in certain circles in favor of educating women. They, after all, were to be the inevitable and primary educators of their own children, and how much more of an advantage would those children have if their mothers were possessed of solid educations themselves. Twenty years later, the fact remained that only 12 public secondary schools were in existence in the whole of England and Wales, despite teh fact that the Taunton Commission found that women had an equal capacity for learning as did men.

One particularly enterprising woman named Anne Jemima Clough began to take matters into her own hands when she switched the focus in her own school from that of domestic skills toward those of academic achievement. Miss Clough would go on to become the first principal of Cambridge’s Newnham College, Cambridge’s second school of higher learning dedicated to female education, the first being Girton, located 2.5 miles away.

Girton College was established in 1869 and opened its doors with just five students. The accomplishment of the industry, hard work, and fundraising of Emily Davies, the intent was to provide women with an education on the same level as Cambridge men, despite the fact that most women who wished for such an education had not been prepared for it in preparatory or secondary schools. In 1871, Henry Sidgewick, a fellow of Trinity, rented a house in which he offered a series of lectures to those who held an interest in hearing them. Many of these women did not live in Cambridge, however, and had to commute, and so facilities were acquired to house them. The school thus came into formal existence in 1881, but its methods were different than Girton, for it understood the necessity of providing a more flexible curriculum based on the need of many women to be brought up to the same level as the men who were entering Cambridge just out of secondary school. Eventually, however, it was those women of Cambridge who returned home to become educators in secondary schools and who had the training to likewise prepare young women to enter the female colleges if they so chose. By 1890, women at Cambridge were outranking their male counterparts and entering the skilled labor force. Even still, there were no degrees to be offered to reward these women for their accomplishments.

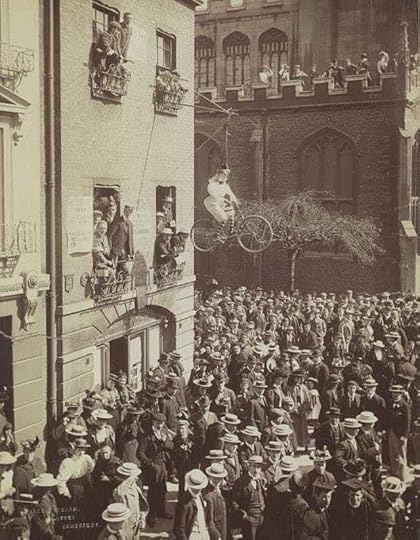

It was little wonder, then, that the women’s suffrage movement found a place in Cambridge. In 1897, a group of “Feminine Fanatics” forced a vote to change the policy regarding degrees for women at Cambridge. The resolution was soundly defeated with a vote of 1,707 against and only 661 in favor. While awaiting the vote, a mob gathered outside. Some threw eggs or confetti, while others threw garbage and epithets. “No Gowns for the Girtonites,” some posters shouted. Another read, “Frustrate the Female Fanatics.” An effigy of a woman on a bicycle was hung outside the first floor windows of the building in which the vote was taking place (now the University Press book shop).

In 1921, a full 24 years later, a second vote was held on the issue of degrees for women and it, like the last, ended in a mob turnout, and, unlike the 1897, in vandalism. It wasn’t until 1948 that women were at last awarded degrees at Cambridge, though to cushion the blow their threatened male counterparts, the number of women allowed to graduate was capped at 20%, a limitation that endured until 1987.

It should be noted that the Cambridge resistance to female education was not universal. The London School of Medicine for Women opened in 1871, and the London University (University College) began awarding degrees to women in 1882.

From the 1860’s into the turn-of-the-century, arguments for and against the higher education of women took up space in the magazines and newspapers of the day. For your pleasure and enlightenment, we offer the following examples:

“It is well known that a woman’s physique is not equal to a man’s, and that the brain power depends very much on the physique which nourishes the brain—ergo, the average woman will never equal the average man on his own ground. We do not deny that a clever woman can equal or surpass an average man; nor that the present system of education is infinitely superior to the old dreary round of lessons. But even to that there are two sides. While girls are learning Greek and mathematics, they have little time for needlework, which used to be a part of every girl’s education, and which they will want to understand at some period of their lives. It is the fashion now rather to sneer at darning, mending, and other trifling household duties; but if a woman is to be a wife and other, she will need a good deal of such knowledge. It is a great thing to know the relation of one angle to another; but it is not every mathematician who brings her knowledge to a particular issue with regard to tables and chairs, or can tell whether a room has been properly dusted or not.”

From “M.P.S.” as found in Girl’s Own Paper, 1882 and available in its entirety here (including a clever rebuttal from a 14 year-old reader.)

Also from the Girl’s Own Paper of 1889 and attributed to “Beatus”

“Women vie with men in the higher branches of the exact sciences, and, as a matter of course, the victory is not always with the strong. But it is more than probable that these individual cases of success are achieved at a terribly disproportionate expense to the ex as a whole. A woman may indeed attain a high place in the mathematical tripos, but in the course of her three years of close and unremitting study, how many sweet visions of life’s springtime have been lost; in the pursuit of those mental gymnastics so appropriate to the male intellect, how many natural feminine faculties have been thwarted and crushed!”

Beatus (we can only assume he is a man) is referencing Philippa Fawcett, the daughter of Suffragist Millicent Fawcett, who, in 1890, became the first woman to obtain the top score in the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos exams, receiving a score 13% higher than the next highest, which, had she been a man, would have awarded her the title of Senior Wrangler. Clearly the author felt that Ms. Fawcett had given up a great deal in the way of marriageable qualities with her achievement. Perhaps she did, for she never married, but she improved the lives of countless individuals in her professional and humanitarian work. Read her biography here.

Beatus goes on to say: “It is difficult to exaggerate the harm which has already resulted from the so-called higher education of women. The earnest sincerity which formerly characterized all good women is gradually being replaced by a light, easy infidelity of high and noble things. The drawing-room conversation of women who have suffered most from this educational scourge, is seldom more than a series of cynical criticism and grotesque perversions, which may sometimes be witty, but are always more or less antagonistic to the cause of truth.”

And, finally, this argument for, which we feel summarizes the root of all inequality, lack of access and then gaslighting of the disenfranchised (ableism).

“There is a vast deal which women have taught men, and men have then taught the world, and which the men alone have had the credit for, because the woman’s share is untraceable. But, cry some of our modern ladies, this is exactly what we wish to avoid; we can teach the world directly, and we insist on being allowed to do so. If our sphere has been hitherto more personal, it is because you have forced seclusion and restriction upon us. Educate us like yourselves, and we shall be competent to fill the same places as you do, and discharge the same duties.”

From Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1863. Read it here.

Many thanks to VictorianVoices.net for their collection of original sources.

May 27, 2021

The Allure of Exclusivity

I put people in boxes. I’m one of those. I like personality typing (Myers-Briggs and Enneagram), astrology, sociology and psychology. I want to understand why people think the way they do, behave the way they do. I don’t use these boxes to define people as much as to understand them. They don’t provide definitions, for no one can be defined by any one measurement, but they do offer clues as to how an individual’s reality is formed, either passively or actively and where their core values are centered (externally or internally).

If you know me at all, if you’ve been following me for any time, you’ll know that I study trauma, I teach it in my yoga classes, and I’m actively looking at and pursuing ways to heal it, in myself and in others. Unresolved trauma is a public health emergency in the United States and has been linked to every social ill from crime to addiction, from violence to obesity, to emotional and psychological woes, even to physical ailments such as asthma, diabetes, auto-immune disorders, and cancer.

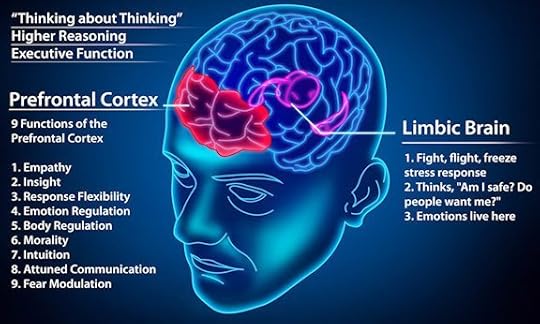

You see, trauma isn’t something you just get over. It changes you. And I don’t mean to say it changes your moods or the way you look at the world. It literally, physiologically, and biologically changes your brain. Among other things, it inhibits proper development of the pre-frontal cortex and can even cause a disconnection between that part of the brain and the limbic system, or that which controls our survival responses. These changes, in turn, causes other changes in our behaviors (how we eat, how we breathe) and even physically, allowing disease (read dis-ease) to take root, because, believe it or not, there is no one part of us that acts or responds on its own. Everything his connected. Every action, every reaction, is born in the brain, whether it’s the decision to run a mile or jump a hurdle or to eat too much or to drink to much or to inject that drug … even though we know it may kill us. Our bodies work as a single unit, not as a series of isolated parts, that’s why a back ache turns into neck pain that turns into a headache, or why poor foot support can lead to knee and hip and back issues.

Our brains are powerful. We know our thoughts can have a direct effect on our function and even on our health. Several prominent researchers on the issue, including Bessel van der Kalk and David Hawkins, have even suggested that the way we speak to ourselves or think about ourselves may influence the ills we contend with. If we despise ourselves, we may find we struggle with auto-immune diseases. People with back and neck problems often thing of themselves as carrying an unfair load, or they feel that others are “a pain in the neck.” People who struggle with asthma often feel overwhelmed by their life circumstances, like they are “drowning”.

I mention this simply as a forward to say … have we all not just survived a collective trauma with this pandemic? Perhaps “survived” is not the right word. We are not quite through it, after all. But for all we have suffered together (which is not just a world health crisis, but a financial one and a political one and a racial one, all at once) why are we still so slow to recognize the experiential pain in others?

I don’t know about you, but my first and tentative steps back into society after this last year has been … disappointing, to say the least. The world has changed, certainly (though not enough, by far) and likely will continue to change for some time. I have definitely changed. I have found that I am less tolerant of lying, of bullying, of exclusion, of intolerance, of closed-mindedness, of smallness, of meanness, of cruelty … and the list goes on, I’m afraid. And it seems that, at the end of the day, the pandemic and all its tangential and consequential fallout, has revealed that there are two types of people. Ok. There are more than that, yes, but let’s imagine for a minute, that there are dichotomies. And these dichotomies have been revealed, at least to me, to include:

Those who include v. those who exclude.Those who are open to the truth, even when they challenge collective belief systems, even when it’s inconvenient, even if it reveals faults in ourselves v. those who defend and even identify with false narratives.Those who understand that a society’s success in the developed world is determined by the poorest of its inhabitants v. those who fear that creating an equitable society means they will lose something, whether its money or privileged station.

The have/have-not mentality is antithetical to the principle of abundance. Where you create exclusion, you are actually creating limitation and smallness. What we wish for others is directly related to what we actually believe is due for ourselves. It’s projection. One cannot wish ill on others and welcome goodness for ourselves, not in the long run, at least. The law of karma is real (though it has nothing to do with universal revenge, as some seem to think).

The idea that if someone has something “they haven’t earned” then somehow I will have less, does not hold truth—not even in terms of taxation. It seems logical, but prosperity is not a pie. Abundance simply doesn’t work that way. Success is a shared experience, after all. When people are educated, for instance, society prospers. When people are healthy, everyone benefits. When people are financially stable, everyone reaps the reward. Everyone. Poverty, financial insecurity, food scarcity, housing insecurity, health issues and the inability to seek and get help, are all traumas in their own right, often caused by trauma which then is perpetuated as further trauma on the next generation and on the individual themselves, resulting in complex trauma. Do you see how deprivation grows exponentially? Abundance and prosperity work similarly but in the other direction.

Likewise, and perhaps more importantly, when we refuse to acknowledge the pain that people are suffering and have suffered, we may be protecting ourselves, but we are doing no one a service. Nothing gets better. Nothing changes. But when we listen, really listen, and accept that what people feel is real, what they suffer is real an not deserved … we heal. If someone tells you they are hurting, is your response to demand they go and complain quietly (as in the case of the recent racial protests) or “just get over it” (as in the case of American racism and the aftermath of the Civil War and white supremacist legislation that followed.) There is no “getting over it” when some people are free and others are not. No one is asking anyone to turn over their life savings to the injured. It costs us nothing to listen to what we might do better in the future. So why are we still fighting this issue? (And this is just an extreme example of what I see as a social pandemic of ignorance and willful blindness). I think far too many of us are unwilling to admit we are in the wrong or that somehow, in our ignorance, that we can do more than we have done to reduce harm. I think too many of us are afraid of what we might lose if the world were truly equal. You are not more important for having someone beneath you. You are not wealthier if there are others who remained impoverished. Not individually, and not as a society. It just doesn’t work that way.

Going back to trauma, because, at the heart of it, I think that’s what we are dealing with, there is something called epigenetics. Remember when I said that trauma changes the body and the brain physiologically? Well, those changes happen at the genetic level, as well, in our DNA, which means that trauma gets passed down from generation to generation. Unresolved trauma becomes complex and compound. You can see how trauma behaviors are passed down in the way people parent and what they teach their children about the world. That is merely social, however. Real, embodied, genetic changes that affect (or limit) the way we process danger, the way we process connection and disconnection (read addiction), and the way we process the stressors around us, how we respond to the world and those in it, those are behaviors that are not only teachable, but genetically inheritable, as are the predilection for addiction, ADD, and even autism.

As a yoga instructor with training in teaching the traumatized, I’ve also trained a bit to teach the autistic. The methods and principles we teach by, the adaptations we make in a class for someone who has survived a traumatic event are precisely the same for someone who lives with autism. Sensory sensitivity, potential triggers for light and sound, difficulty being grounded and embodied (feeling what the body feels), are all the same. We adapt our music, the lighting, the clothes we wear, the tools we use, and even where we teach (always on the mat) and how we approach our students in a physical sense (never touching them without their permission). What if autism is merely the manifestation of inherited trauma? It is certainly a trauma of some kind. But is it an injury, or is it an epigenetic inheritance? I don’t know, but it’s an interesting question.

Looking at the issue from a wider lens, what if those who are struggling with the pain of a past filled with oppression are not just mentally and emotionally holding onto those injustices, but are experiencing them in a bodily way? They cannot just get over it because it is still a part of their reality, socially, culturally, psychologically, and physiologically. There is no just getting over it until the injustices are addressed and the responses examined repatterned. And this isn’t an expensive fix, either. Programs are already in place to deal with these issues for veterans. It is just as easily applied to the public at large, and in very simple and grass-roots ways.

We’ve talked about the trauma that victims and former victims and the descendants of victims are still struggling with. What about the oppressors themselves, whether acting in full knowledge or quite ignorantly? Stay with me a minute.

Last summer when I was conducting some interviews with those actively continuing the battle for equal rights, one gentleman brought up the idea that it is not just former slaves and their descendants who are traumatized, but the slavers and their antecedents as well. Think about it. What does cruelty do to a person? And we can have the argument about whether or not slave owners were cruel to their slaves—but let’s not. If you had any part in keeping a human being from freedom, no matter the reason, if you can see another human being as property, that is a cruelty that no other kindness can make up for. And let’s be clear here, the Civil War was about slavery. It just was. This lie that it was not is just that—a lie. If it were not the case then the issue of slavery and the South’s right to maintain “that peculiar right” would not have shown up 80 times in the various papers of secession. The proof is in the words of the secessionists themselves. And so, if that is your background, if those were your people, perhaps something has trickled down in you, as well, that, for whatever reason, makes you feel invested in preserving that narrative. I do believe the white south suffered horrific trauma as well. Loss of fortune and home and the lives of loved ones is no small thing, but, the loss was not equal to that which they caused, so, in the end, what is left is this collective guilt and a resentment for the karma whose circle has not yet been closed.

It’s trying to close, though. What we have right now is a collective societal reckoning. Perhaps the history of the American South doesn’t figure into your own history. Again, I use this as merely an example. If you truly feel that by someone else having something you don’t think they have earned (and you really cannot know that, not really) then what is it you are struggling to protect? What is it you fear losing? Money? Power? Or are you simply afraid of being wrong? But if you couuld learn something, if you could grow and become better … isn’t that a good thing? As a Saggitarius rising, that is the thing I strive for, growth and change and betterment. I hope I’m not alone.

So what is it I want? What is the point of this post? I’m begging for some introspection here. There are lies, “scripts” we all believe in, whether it’s a political narrative or a religious one or some bit of history we are invested in defending, despite the proof to the contrary. The answers are always within. Always. What will it cost you to move in the world from a place of more kindness, more unity, more Christianity, more actual and authentic goodness? How do we let love and unity be our guide? What does it really cost us to admit that there are places in our lives where we can do better, where we can be heroes and advocates, where we can walk softly and do no harm. At least let us all make an effort to do less harm. I beg.

April 29, 2021

Dystopianism, Steampunkery, and the Influence of the Kaiser Wilhelm

What was I thinking?

What, after all, is a successful historical fiction author doing dipping into the realms of science fiction?

Well, the thing is, when you have an idea, sometimes you just have to develop it.

At the time I started this series, I had conservative leanings. I was intrigued, at the time, by the world of conspiracy theories. It was the Obama era, and my conservative friends were afraid and trying to persuade me to be, as well. I wasn’t really certain either way, but I was willing to give ear to all these things I “ought to know about”. So I listened as people prattled on about a government militarized police force, to vaccinations that were meant to manipulate the population, to secret agendas in which only the political elite would survive and thrive and own everything and we would all become their slaves.

At first the book was intended to be ultra modern, with tanks and survival gear, and all that. But that was never truly me, and when I began developing the story from a rough outline into something with living, breathing characters who spoke and thought and schemed for their own survival, I realized there was only one way I could pull it off, and that was to pull from my roots of historical writing.

I know. It doesn’t make any sense.

I’ve always been fascinated with steampunk. Particularly the rather nuanced idea of it that precludes the avoidance of the First World War, which, as proposed by Gillian Gill in Queen Victoria’s biography We Too, was perhaps just possible, had Prince Albert lived longer.

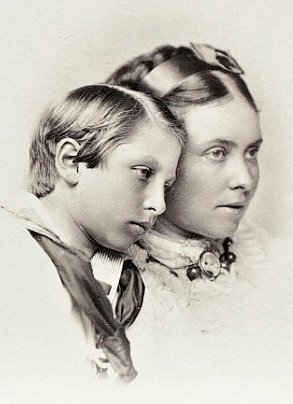

Friederich (Fritz) and Victoria (Vicky)

Friederich (Fritz) and Victoria (Vicky)“In 1862, when the [Prussian] legislature dared to oppose his plans for the army, the king of Prussia furiously prepared a statement of abdication that his son [husband of princess Vicky, eldest child of Queen Victoria and Albert] had only to sign to become king. Despite his wife’s frantic entreaties, Fritz persuaded his elderly father to keep his crown since the coronation oath committed a king to rule until his death. As a result, King William I of Prussia not only lived to be crowned Emperor William I of Germany at Versaille in 1871, but ruled for seventeen more years. Fritz finally acceded to the throne as Emperor Frederick I in 1888 and died of throat cancer three months later. Had the prince consort [Albert] been alive in 1862, he might have been able to persuade Fritz that his higher duty was to the nation, not his father, and that he must seize the reins of power.

Vicky and Wilhelm

Vicky and Wilhelm“No one ever doubted that if Crown Prince Frederick came to the throne of Prussia, Bismark and the far-right party would be dismissed, and his wife, Victoria, would be the power behind the throne. As king and queen of Prussia in 1862, Fritz and Vicky would probably have had decades to try to realize her father’s political vision. The forces of liberal democracy would have had a better chance of prevailing over militarism and absolutism. It is not absurd to argue that, had the prince consort lived even one more year, had his daughter Vicky had a chance to dictate Crown policy and shape society in Prussia, there would not have been a First World War.”

This is in part because, as Gill notes, “King William and Bismark passed their hatred and distrust (of Albert, Queen Victoria and the British) on to Prince William (Wilhelm), Vicky and Fritz’s eldest son, the future kaiser of World War I. Under their tutelage, this damaged boy became a deranged man all too willing to blame his English mother for all his problems, personal and political.”

So that’s interesting. What would England look like now had World War One never happened? Had their been no World War One, after all, the conditions that brought about World War Two would not have existed. Wars change fashion, they change our perspectives of life and its meaning and what we must and can do to survive and, further more, to live life to the fullest. Science and technology take enormous leaps forward in times of conflict. Such fraught and desperate times have lead man to some of his greatest achievements. Prosthetics, plastic surgery, aeronautics, and computer and communication technologies all benefited from the demands war placed on these disciplines.

And so Absinthe Moon and its sister volumes, have become a neo-Victorian nod to dystopian steampunkery. Only it was never my intention for it to be truly dystopian. I’m so frustrated by books that don’t end well, though certainly they have their place. I did see some need to offer the world a warning about where we were headed, and though the dangers I see now are somewhat different than those I first imagined, it is ultimately intended to be a book about hope and awakening.

There is something in the collective consciousness that brings just the right thing about when it is needed. This need for a warning, but also for reason to hope has been something slowly pervading our culture for many years now. So much so that a new genre has evolved. Solarpunk.

According to Wikipedia, “Solarpunk is an art movement that envisions how the future might look if humanity succeeded in solving major contemporary challenges with an emphasis on sustainability problems such as climate change and pollution.”

I do worry a bit about how some of these themes will be received. Race, caste, pollution, and the ethics of medicine (including vaccines) are all visited, but I don’t really have a message except to say that we can do better than this oligarchical caste system we have that is bent on exploiting natural and human resources for the benefit of a buck.

It also maybe has something to say about what exists beyond the limits of our physical senses. But I’ll let you decide.

A Dystopian, During a Pandemic? Really?

What was I thinking?

What, after all, is a successful historical fiction author doing dipping into the realms of science fiction?

Well, the thing is, when you have an idea, sometimes you just have to develop it.

At the time I started this series, I had conservative leanings. I was intrigued, at the time, by the world of conspiracy theories. It was the Obama era, and my conservative friends were afraid and trying to persuade me to be, as well. I wasn’t really certain either way, but I was willing to give ear to all these things I “ought to know about”. So I listened as people prattled on about a government militarized police force, to vaccinations that were meant to manipulate the population, to secret agendas in which only the political elite would survive and thrive and own everything and we would all become their slaves.

At first the book was intended to be ultra modern, with tanks and survival gear, and all that. But that was never truly me, and when I began developing the story from a rough outline into something with living, breathing characters who spoke and thought and schemed for their own survival, I realized there was only one way I could pull it off, and that was to pull from my roots of historical writing.

I know. It doesn’t make any sense.

I’ve always been fascinated with steampunk. Particularly the rather nuanced idea of it that precludes the avoidance of the First World War, which, as proposed by Gillian Gill in Queen Victoria’s biography We Too, was perhaps just possible, had Prince Albert lived longer.

Friederich (Fritz) and Victoria (Vicky)

Friederich (Fritz) and Victoria (Vicky)“In 1862, when the [Prussian] legislature dared to oppose his plans for the army, the king of Prussia furiously prepared a statement of abdication that his son [husband of princess Vicky, eldest child of Queen Victoria and Albert] had only to sign to become king. Despite his wife’s frantic entreaties, Fritz persuaded his elderly father to keep his crown since the coronation oath committed a king to rule until his death. As a result, King William I of Prussia not only lived to be crowned Emperor William I of Germany at Versaille in 1871, but ruled for seventeen more years. Fritz finally acceded to the throne as Emperor Frederick I in 1888 and died of throat cancer three months later. Had the prince consort [Albert] been alive in 1862, he might have been able to persuade Fritz that his higher duty was to the nation, not his father, and that he must seize the reins of power.

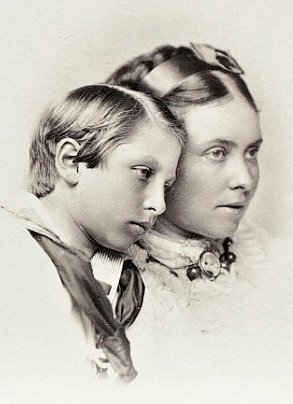

Vicky and Wilhelm

Vicky and Wilhelm“No one ever doubted that if Crown Prince Frederick came to the throne of Prussia, Bismark and the far-right party would be dismissed, and his wife, Victoria, would be the power behind the throne. As king and queen of Prussia in 1862, Fritz and Vicky would probably have had decades to try to realize her father’s political vision. The forces of liberal democracy would have had a better chance of prevailing over militarism and absolutism. It is not absurd to argue that, had the prince consort lived even one more year, had his daughter Vicky had a chance to dictate Crown policy and shape society in Prussia, there would not have been a First World War.”

This is in part because, as Gill notes, “King William and Bismark passed their hatred and distrust (of Albert, Queen Victoria and the British) on to Prince William (Wilhelm), Vicky and Fritz’s eldest son, the future kaiser of World War I. Under their tutelage, this damaged boy became a deranged man all too willing to blame his English mother for all his problems, personal and political.”

So that’s interesting. What would England look like now had World War One never happened? Had their been no World War One, after all, the conditions that brought about World War Two would not have existed. Wars change fashion, they change our perspectives of life and its meaning and what we must and can do to survive and, further more, to live life to the fullest. Science and technology take enormous leaps forward in times of conflict. Such fraught and desperate times have lead man to some of his greatest achievements. Prosthetics, plastic surgery, aeronautics, and computer and communication technologies all benefited from the demands war placed on these disciplines.

And so Absinthe Moon and its sister volumes, have become a neo-Victorian nod to dystopian steampunkery. Only it was never my intention for it to be truly dystopian. I’m so frustrated by books that don’t end well, though certainly they have their place. I did see some need to offer the world a warning about where we were headed, and though the dangers I see now are somewhat different than those I first imagined, it is ultimately intended to be a book about hope and awakening.

There is something in the collective consciousness that brings just the right thing about when it is needed. This need for a warning, but also for reason to hope has been something slowly pervading our culture for many years now. So much so that a new genre has evolved. Solarpunk.

According to Wikipedia, “Solarpunk is an art movement that envisions how the future might look if humanity succeeded in solving major contemporary challenges with an emphasis on sustainability problems such as climate change and pollution.”

I do worry a bit about how some of these themes will be received. Race, caste, pollution, and the ethics of medicine (including vaccines) are all visited, but I don’t really have a message except to say that we can do better than this oligarchical caste system we have that is bent on exploiting natural and human resources for the benefit of a buck.

It also maybe has something to say about what exists beyond the limits of our physical senses. But I’ll let you decide.

March 29, 2021

Pride and Humility: A Historical Fiction Author’s Views on the Merits of Fictional License in Historical Romance

Do all authors start out as ego-centric snobs? I did. After reading every piece of Regency/Victorian/Edwardian literature I could find, from Dickens and Eliot to the lesser-knowns like George Meredith and Silas Hocking, I got to a point where I felt my favorite tropes had been exhausted. So I started a book that I hoped would include them all: love-hate relationships, misunderstandings, arranged marriage, inheritance, women’s equality, platonic-love-turned-romantic, rags to riches . . . . But they weren’t going to be Historical Romances. Oh, no! I was literary. I was well-read and well-educated. The books I wrote would be historical masterpieces, thoroughly researched to within an inch of their little lives. Oh, and they weren’t little, either. Great big 500 page tome’s, they were. And they were, or so I hoped, Literary Fiction. At least they were Historical Fiction. Weren’t they? I made sure I was writing about things that actually happened, even if the characters were invented (the Married Women’s Property Act of 1888 and all the greed-driven finagling that went on between guardians and their naive wards, the opening of the Tube, the development of the automobile).

I used my books not just to convey historical events, but also to paint an accurate picture (accurate, at least to my mind) of the manners and mannerisms, the etiquette and cultural norms of the age, the philosophies and belief systems, the rules written and unwritten, the and, even, the tolerated if unusual. It was this last that got me into trouble. In some fields, or so I’ve learned is the case in nearly every sphere I have worked in (from the literary to the too-oft politically charged world of historical preservation) everyone is an expert, and everyone else is not. To all of this I added my own experiences (for some conflicts are timeless) and veiled them behind the garb of bustles and corsets and the backdrop of ballrooms and dining rooms and unwed and newlywed bedrooms.

And, of course, and despite my painstaking study, my immersive self-education . . . it proved not to be enough.

Here is the lesson: history is an illusion. If you don’t believe this, try having a civil discussion on the Civil War, it’s origins and repercussions. Is there a right view at this point? Or is it all, a hundred and forty years later, merely an invention of modern understanding? Yes, the truth is there somewhere, but I defy you to present one person who has it all exactly accurate in their heads, from who dealt the first blow to who bears the blame of it now. The point being, not that there is not truth out there, but that no two people are likely to grasp it similarly.

O.K. That’s an extreme example, but it’s true that the past is something of an illusion. We barely can grasp our presence with the accuracy it requires.

So, after writing the three books, which I had originally planned to be five, I gave up on my attempts at Historical Fiction. Not because they weren’t good. And certainly not because people wouldn’t read them. Those books made me a lot of money, after all. But more because it just felt like too much work to craft a book the way I thought I was crafting it, only to find out that it was something else entirely. And I see now that I could have told the stories more concisely, but . . . they are what I wanted them to be at the time. I did the best I could. But plotting such large books is a real challenge.

And then, for some reason I can’t really explain, I got it into my head to write a political conspiracy. It started out as a modern piece. It was full of conspiracy theories and dark warnings about where we were headed politically, both in our country and across the civilized world.

But then my viewpoint and perspective changed. I was writing a dystopian saga. It felt smarter than me, challenging in a way that was less exhilarating than it was terrifying.

And then came COVID and the “pop-up apocalypse” as my eldest child so aptly (and accidentally) dubbed it. 2020 was hard for most of us. It was certainly so for me. I kept having this nagging feeling that I needed to sit down and write. I made myself busy decoupaging walls, painting furniture, writing letters, reupholstering furniture . . . . And then the universe said “SIT DOWN AND WRITE, DAMN IT!” I didn’t listen until finally I fell down the back steps and broke my foot and was relegated to the sofa for the next ten weeks. Finally I started writing.

And then I suffered a devastating loss.

And then I started bing-watching James Acaster. (I will always be grateful to you, James, for being a true companion during that really difficult time.) I followed that up with true crime documentaries. Because it was ugly and horrid, but within a few short hours, the mystery would be solved and justice fulfilled.

And then Emma was released.

I watched it once, and then again. At first I was like . . . who is this scruffy Mr. Knightly? And now, five times through it, I’ve watched everything Johnny Flynn is in. But this is about Historical Romance and not my celebrity crushes.

While Emma is certainly literature, it is so much more than that. It is PRETTY! It is light-hearted! It is funny and charming and whimsical . . . it is a romantic confectionery such as I had forgot existed (and yes, I’ve seen EVERY Emma ever made)!

I should also mention here . . . BRIDGERTON!

Before I saw it, I literally said to a friend, “This represents everything I’ve ever and always hated about Historical Romance! It is NOT historically accurate, not in its casting, not in its characterizations, not in the language or the mores or the etiquette or subject matter.

And then I watched it.

And here’s the thing I have come to. Firstly, we NEED more beauty and love and hope (and yes, sex) in our lives! We need this return to art for art’s sake and beautiful language and yummy costumes (even if we don’t wear them ourselves–but oh. . .can I, please?) We need tidy plots with happy endings and the suggestion (if not the promise, impossible to make) of future happiness and stories that continue in bliss and companionable contentment off-stage. But do you know what we need more than that? We need to stop idealizing what was wrong with the past and nobleize and normalize what should be the ideal in our own society: diversity, equality, justice, love on equitable terms, fairness for all, righteous anger (don’t we all feel something of that right now?), and encouragement that the fight is worth it! These are things that truly accurate Historical Fiction cannot deliver. At least it is rarely accomplished if all the prejudices and inequalities are to be treated with the accuracy that we understand to be the norm. But that’s just it. If my books and others like them go off the tracks a little bit to make a necessary point to the modern-day reader, isn’t that all the better? Some themes, as I said earlier, some conflicts are true no matter what the year and the era.

So I will be less judgmental in the future and less rigid when it comes to my own expectations. I’ve recently started a new series that I think will be as fun to read as it is proving to be to write. I haven’t tossed all the rules out the window, but I’m definitely handling them in a more tongue-in-cheek fashion.

I think we are all over this “pop-up apocalypse”. Thank heaven Absinthe Moon and its sister volumes are not truly dystopian but end on a note of enlightenment and hope and empowerment (I just read that this is actually part of a new genre called SolarPunk). At least they will when I’ve finished them . . . and that is closer than you might think.

So yes, read and watch those cheesy HistRoms! Do it to enjoy a more genteel time and place, but do it, too, with the hope that what is good and noble in those can be ours again in this life, as well.

Or just because it’s fun. That’s enough of a reason, isn’t it?

February 22, 2021

High Society: Marijuana Use among the Victorians

While waiting for edits to come back for Odessa Moon, I was feeling inspired, and so I decided to dip my pen back into the inkwell of historical fiction/romance. Fearless centers around a young woman, Charlotte Darling, whose father is dying of cancer. The estate that has been her home all her life is to be inherited by a cousin-by-marriage, and she’s feeling all the fear and sorrow and uncertainty of her situation. Enter the cousins (though they are not that in actuality). The gentlemen are half-brothers. Mr. Blakeny is to inherit Mr. Darling’s estate of Blithewell, while Mr. Landry has inherited his father’s home already. Mr. Blakeny is rather an egotistical bore, while Landry is, well, … not, though he does have something of a reputation for “restlessness”. What that means takes some time to figure out, but when Mr. Darling’s suffering becomes too pronounced to bear and still attend to all the tasks necessary of making his final arrangements and preparing to turn over management of his estate to his successor, Mr. Landry tasks himself with the errand of finding some medicinal respite for Mr. Darling.

I love the historical research aspect of writing historical fiction. For Of Moths and Butterflies, I’d researched the various opiates used during the Victorian era and their availability, examining everything from the dark, seedy, smoke-filled atmosphere of London’s controversial opium dens to the fast-handed and relaxed manner in which laudanum was dispensed for even the slightest complaint and ailment. In fact, I’d used the “innocent” remedy of laudanum in the self-destruction of Bess Mason (you can read an alternate version of her death in the short story Hallam’s Wood, available in the short story collection, Parade, (still .99 at Amazon). In dealing with Mr. Darling’s instance, however, I wanted something that was a little harder to get hold of, an errand that would take him very suddenly to London, providing evidence of his “restless” nature. At the same time, I didn’t want it to be something quite so menacing and debilitating (or paint Mr. Landry in so paltry a light) as straight up opium would do. So I began to dig a little deeper. And this is what I learned:

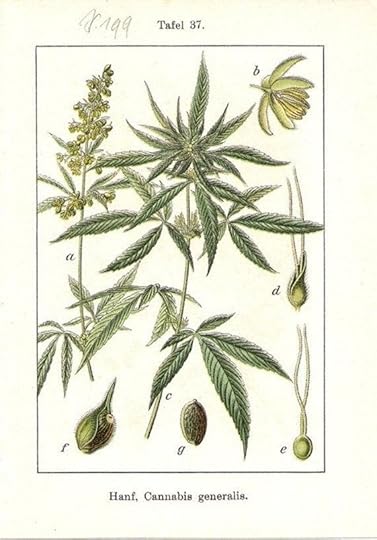

Cannabis is actually native to Europe and England, and was used heavily for its fiber content in the making of rope and sacking. The climate, however, did not allow for the development of any psychoactive substances, and so it wasn’t until the English occupation of India that any real attention was given to the medicinal or recreational uses of the plant.

It was Sir Whitelaw Ainslee who, while serving as an attending surgeon in Madras in the early 1800’s, began to chronicle the many and various ways the plant was used in India. Ainslee was a devout Christian and believed firmly in the virtues of temperance. While he found that cannabis was used extensively for medicinal purposes, he was more concerned with its use as a recreational intoxicant and spent more time chronicling these in his publications than on any of its more practical and actually useful properties.

In contrast, Ainslee’s successor, Sir William Brooke O’Shaughnessy, appears to have been more enthusiastic in his approach. Rather than keeping a wide-birth of the plant, observing it from afar as if it were the seed of Lucifer itself, O’Shaughnessy gathered local knowledge from local experts and then proceeded to conduct a vast array of experiments, even using himself as a subject to learn first-hand the effects of the plant in its various derivatives and uses.

In 1842, O’Shaughnessy published the Bengal Dispensatory and Companion to the Pharmacopoeia in which he detailed the many and varied properties of cannabis, beginning with its “narcotic effects” but making a strong case for its medicinal benefits, as well. It seems he understood at the outset the objections many in the west would have to the drug, whose recreational use had already been described and condemned, and in defending it made his own authoritative declaration that the plant was not used nearly so widely, nor were its effects as harmful as those of opium, alcohol, or even tobacco.

One of his more interesting discoveries, after experimenting upon every manner of animal, from fish to cattle and feline to human, was that carnivorous animals were much more strongly effected by the inebriating qualities of the drug than were granivorous animals, no matter how large the dose.

Of his human subjects, O’Shaughnessy’s first subjects were rheumatic patients, all of whom attested to being relieved of pain following administration of cannabis. They also reported experiencing improved mood and appetite, as well as restored vitality, all without side-effects of headache or sickness (or nightmares), which were so often the results of opium use. In other patients, cannabis appeared to minimize the symptoms of cholera, controlling diarrhea and vomiting and allowing the patient to rest more comfortably. Other ailments upon which cannabis provided positive results included tetanus, the symptoms (though not the disease itself) of rabies, ‘infantile convulsions’, even asthma, hypertension, anxiety, and various digestive issues. For the relief of pain, the drug was almost miraculous.

O’Shaunessy wrote of his findings, and these were published in medical journals of the time. His work was widely read and even respected by the medical community in India and at home in England. O’shaunessy’s work led to the popularizing of the use of cannabis, and it began to be produced in every imaginable form from tinctures to pills, and, of course, the traditional forms for smoking.

In the mid-1800’s there existed sort of a mania for women’s health, born out of the mystery of women’s suffering and of reproductive issues (which included hysteria and mental and emotional issues that were attributed generally to the female reproductive organs). Up until this time, opiates had largely been used to treat such issues, particularly those of menstrual pain, but opiates produced some horrible side effects, including headaches, nightmares, and vomiting. Tinctures of cannabis began to be used widely for menstrual pain and to prevent premature labor. It was also used widely for treating insanity.

From the 1840’s through the 1870’s the use of cannabis exploded, and the plant grew to be hailed as a wonder drug. But the success of the drug (and the relief it provided to those who used it medicinally) was not to last. The 1880’s introduced a backlash. Unlike cocaine and opium, the active ingredients could not be isolated in cannabis (indeed, THC was not isolated until 1964) and so it was impossible to predict the effects of a treatment since the dosages could not be regulated. It’s clear from some of the reports of experiments and treatments that levels were used that introduced a catatonic state, while others merely left the subject with a sense of relaxation and mild giddiness.

During a session of Parliament in 1891, Mark Stewart MP stood and drew the House of Commons’ attention to a statement made in the Allahabad Pioneer earlier that year regarding the dangers of cannabis or “ganja” use. The article claimed that cannabis was far more dangerous than opium and for that reason had been made illegal in Lower Burma. The article further observed that “the lunatic asylums of India are filled with ganja smokers.” (Indeed they were filled with substance users of all sorts, but cannabis users were only a small percent of such.) Stewart, an accomplished temperance campaigner, had no qualms lumping together all the many forms of cannabis into one, some of which did, indeed, produce some strong intoxicating effects. But Stewart was not alone in his efforts to villainize hemp and its derivatives.

William Sproston Caine, a fellow member of parliament, dedicated much of his life to the temperance movement, presiding over such institutions as the Baptist Total Abstinence Society and the National Temperance Federation. Caine traveled to India with the intent on familiarizing himself with the darkest sides of the industry, concluding, predictably, that cannabis was “the most horrible intoxicant the world has yet produced.” After delivering his findings, he asked Parliament to form a commission of experts to investigate the use and effects of cannabis in Bengal, including the effects such substances ultimately had on the moral and social condition of the people who used it. Caine’s request was seconded by George Russell, the secretary of state and Parliamentary secretary for India. The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission was formed, but the British government, having a large stake in the opium trade, was happy to encourage the temperance adherents toward fighting against the ills of cannabis if it kept their attention off of far more economically impactful legislations against alcohol or opium.

After 266 days of travel across India, conducting experiments and interviewing those who grew the plant and harvested it for medicinal and recreational use, as well as speaking with those who used it, the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission concluded that less than one percent of the population consumed cannabis preparations and that, of these users, only about five percent might be considered excessive users. Moderate use was not believed to cause harm and the commission declared that “the habit of using hemp drugs was easier to break off than was a dependency on alcohol or opium. The commission also suggested that the predisposition to consume such intoxicants was a sign of mental weakness in and of itself, as opposed to such weaknesses being caused by the use of cannabis drugs, whether in excess or otherwise.