Judith Works's Blog, page 9

December 6, 2013

CHRISTMAS IN ROME

The Christmas season in Rome begins on December 1. We had the pleasure of participating in the start of the festivities in Piazza Navona and the neighborhoods. The first event on our list was the annual United National Women's Guild bazaar with shopping opportunities from the world over to fund projects in developing countries.

We paused at this shop on the way to Piazza Navona to inspect their treats:

Next stop was wonderful Piazza Navona where the traditional Christmas market was being set up.

One of the most important traditions is that of a Nativity Scene, first popularized by St. Francis in the 1200s. Many stands feature enormous selections of figures to make your own: the Holy Family, peasants and now some Nelson Mandelas, food, animals and cork-bark shelters for angels to hover over.

One of the most important traditions is that of a Nativity Scene, first popularized by St. Francis in the 1200s. Many stands feature enormous selections of figures to make your own: the Holy Family, peasants and now some Nelson Mandelas, food, animals and cork-bark shelters for angels to hover over.

And of course there are loads of stalls filled with toys.

And a carrousel:

And, the most important, the wizened old grannies called befane who fly through the air astride

broomsticks. La Befana is the witch who brings Christmas treats to children if they are good and coal if they have been bad. She arrives on the night of January 5th to ensure gifts are ready on Epiphany morning in remembrance of the Gifts of the Magi. But no real worries - the "coal" is really black candy, so bambini are never very worried.

In case you want to know more here's a delightful clip:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=meR3gMhtfPE

When it was time for a snack we stopped by the chestnut vendor:

Finally, ready for a return to our hotel we paused at the Pasticceria Barberini on the Via Marmorata for a coffee and a look in their window:

A perfect start to the season which we would soon be celebrating in our home in the Pacific Northwest.

We paused at this shop on the way to Piazza Navona to inspect their treats:

Next stop was wonderful Piazza Navona where the traditional Christmas market was being set up.

One of the most important traditions is that of a Nativity Scene, first popularized by St. Francis in the 1200s. Many stands feature enormous selections of figures to make your own: the Holy Family, peasants and now some Nelson Mandelas, food, animals and cork-bark shelters for angels to hover over.

One of the most important traditions is that of a Nativity Scene, first popularized by St. Francis in the 1200s. Many stands feature enormous selections of figures to make your own: the Holy Family, peasants and now some Nelson Mandelas, food, animals and cork-bark shelters for angels to hover over.

And of course there are loads of stalls filled with toys.

And a carrousel:

And, the most important, the wizened old grannies called befane who fly through the air astride

broomsticks. La Befana is the witch who brings Christmas treats to children if they are good and coal if they have been bad. She arrives on the night of January 5th to ensure gifts are ready on Epiphany morning in remembrance of the Gifts of the Magi. But no real worries - the "coal" is really black candy, so bambini are never very worried.

In case you want to know more here's a delightful clip:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=meR3gMhtfPE

When it was time for a snack we stopped by the chestnut vendor:

Finally, ready for a return to our hotel we paused at the Pasticceria Barberini on the Via Marmorata for a coffee and a look in their window:

A perfect start to the season which we would soon be celebrating in our home in the Pacific Northwest.

Published on December 06, 2013 14:55

November 4, 2013

COUNTRY PLEASURES

What better than a few days in the Italian countryside? Especially if they involve a castle, a swimming pool and time to visit small hill towns nearby in the warm sunshine.

A writer friend in Italy recommended the Castello di Santa Maria, located near the tiny village of San Michele in Teverina, at the north end of Lazio, the region surrounding Rome. The castle is part of the Charme & Relax network of (mostly) country homes and castles.

We drove north from Rome, through Viterbo and on to a rural secondary road towards Orvieto, turning off at the sign to the village and our destination. Then up a cypress-lined drive to reach the castle – an 15th Century monastery founded by the Camaldolesi monks, and enlarged by the friars Servants of Mary in the 17thCentury. Now restored and converted to a hotel with several rooms in the main building, and cottages set in an olive grove or near the swimming pool. A slice of heaven, Italian style.

Our cottage had two bedrooms and baths separated by a living room, perfect for two couples, giving us both privacy and community. We overlooked the pool, olive trees and in the distance the isolated hill town of Cività di Bagnoregio perched on a outcrop in the middle of barren land.

We used our hotel as a springboard to visit surrounding towns. The first goal was to drive to Bagnoregio where the steps and bridge to the town begin. Cività is a medieval town precariously clinging to eroding rock, population 12 plus cats in winter but more in summer when tourists make the trek up and down steps and over a bridge to look around. The town was founded by the Etruscans like everyplace else in the area. Its claim to fame beside the spectacular location is that it was the boyhood home to Saint Bonaventure. Unfortunately, his home has long since fallen off the cliff into the abyss. One wonders when the rest will follow.

Civitella d’Agliano, where there is little to see, spills down a hill with narrow twisting streets and ancient dwellings. The street is so narrow it took fifteen minutes of to-and-fro to get out of a dead end. When the car was finally positioned to leave the town we were pointed steeply downhill on a road taking us to a fallow field with no way to make a turn back up to the main road. Down we went hoping for some way to return. At the bottom there was a treat: a medieval washhouse, the clear waters pouring out of a spout to bathe the ferns. No washer-women in sight – they were all standing on their tiny balconies or front steps above us watching with amusement as we tried to maneuver.

Orvieto, an actual city with medieval towers, is set high on a rock outcropping. The black and white striped Duomo with its marvelous mosaic and carved marble facade is the main attraction.

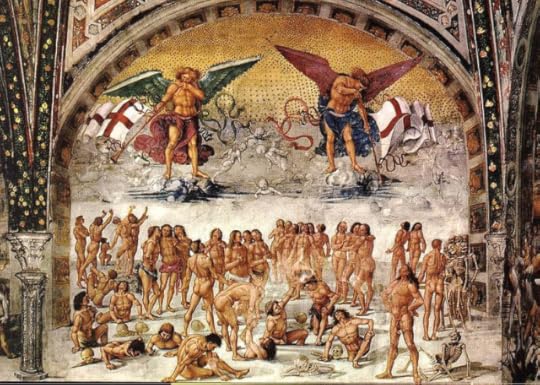

The treasure filled interior hosts the Chapel of San Brizio decorated by Renaissance masters. The frescoes by Luca Signorelli depicting the Preaching of the Antichrist, End of the World, Resurrection of the Flesh, and the Damned Taken to Hell are enough to scare viewers out of their wits (and to stop sinning). Most alarming was the Devil shooting death rays on an ill-fated town. The rays looked too much like missiles so common in our own age. The Resurrection scene is almost three dimensional with bodies crawling out of holes. Signorelli seemed to have especially enjoyed painting the nicely-rounded posteriors of naked men in this remarkable scene where everyone, but a few skeletons, flaunts a perfectly toned body as if their time in Purgatory was merely a spa cure.

The treasure filled interior hosts the Chapel of San Brizio decorated by Renaissance masters. The frescoes by Luca Signorelli depicting the Preaching of the Antichrist, End of the World, Resurrection of the Flesh, and the Damned Taken to Hell are enough to scare viewers out of their wits (and to stop sinning). Most alarming was the Devil shooting death rays on an ill-fated town. The rays looked too much like missiles so common in our own age. The Resurrection scene is almost three dimensional with bodies crawling out of holes. Signorelli seemed to have especially enjoyed painting the nicely-rounded posteriors of naked men in this remarkable scene where everyone, but a few skeletons, flaunts a perfectly toned body as if their time in Purgatory was merely a spa cure.

The Damned Taken to Hell has the famous winged devil carrying a naked woman to her fate. All that death and misery was soon too much to contemplate on a lovely day – it was lunch time. Sitting with other diners on a restaurant terrace we soon forgot about Signorelli’s world and our own in favor of concentrating on the local Orvieto white wine and pasta at Vinosus Wine Bar near the Duomo.

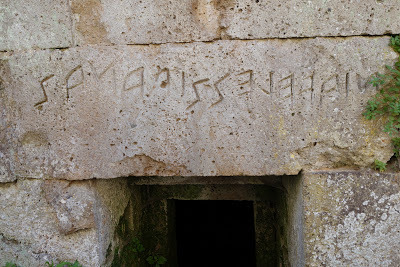

But we had one more sight involving death to see before we left - the small Etruscan cemetery, located beneath the towering hill. Granted, there are many other Etruscan necropoli, but this is the only one I know of where the families of the deceased have their names chiseled into the stone. Could they ever have imagined tourists would be tramping around trying to decipher names and looking into the dank and empty mausoleums long emptied of their contents by looters or archeologists?

But we had one more sight involving death to see before we left - the small Etruscan cemetery, located beneath the towering hill. Granted, there are many other Etruscan necropoli, but this is the only one I know of where the families of the deceased have their names chiseled into the stone. Could they ever have imagined tourists would be tramping around trying to decipher names and looking into the dank and empty mausoleums long emptied of their contents by looters or archeologists?When it was time for us to end the day’s exploration we returned the “long” way on quiet winding roads snaking through the countryside where vineyards soaked up the lowering sun. Below the hills, the valley of the Tiber with train tracks and the autostrada reminded us of the busy life of modern day Italy awaiting us when we returned to Rome.

When I arose at dawn the following morning a full moon was setting over the olive groves. Ah – Italy!

Published on November 04, 2013 15:03

October 3, 2013

LAGO DI ORTA & OTHERWORLDLY HANDS

Mellow sunshine made the trees dressed in fall finery glow in the warmth of the day. We were off on a day trip from Milan through rolling forested hills to Orta San Giulio. The small town rests on the shore of Lago di Orta, one of the smallest of the lakes that decorate the northern part of Italy between the plain of the Po River and the Alps. This area has long been our romantic destination, both in actuality and in my mind.

Well, there is truth to the old saying that you can’t go home again. Instead of a few holiday makers strolling through galleries and boutiques there were busloads of people jamming the central plaza for a quick pasta and beer before climbing aboard for the next stop on their itinerary. The galleries and boutiques were shuttered, victims of the poor economy in Italy. Even more depressing, our long-time favorite hotel which dominated one side of the plaza, was a ruined hulk brooding over the lakeside and the determined visitors.

Fortunately, not all was lost. The church bells from the Benedictine nunnery on the small island not far off shore from the town still reverberated over the quiet water as always and a well-dressed crowd of locals was congratulating a pair of newlyweds in the municipal gardens.

Fortunately, not all was lost. The church bells from the Benedictine nunnery on the small island not far off shore from the town still reverberated over the quiet water as always and a well-dressed crowd of locals was congratulating a pair of newlyweds in the municipal gardens. The lacy wrought iron gates to villas were as beautiful as ever as were the villas themselves.

But as much as I love the little town with its Baroque church and cobbled streets, the most enchanting locale is the Sacred Mountain, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Set on a hill overlooking the town, twenty small chapels, some dating from 1590, are set in quiet woods.

Each is filled with life-sized but dusty terracotta figures depicting scenes from the life of Saint Francis.

Demonstrating the continuity of the endeavor, the earliest chapels are in Renaissance style. As time passed, the succeeding building style changed to the theatrical Baroque, then Rocco, and finally Neo-classical in the last quarter of the 18th Century. Taken together they present a harmonious arrangement with the greensward, trees and vistas of the lake with its little island combining to encourage contemplation whether you are religious or not.

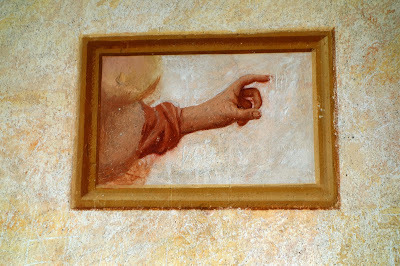

But it is the fresco on the exterior of every chapel that always attracts me: who can resist a a faded disembodied hand emerging from a cloud? Are they the hand of God admonishing the worshipper?

The hands seem to point tentatively, although with gentle grace. I like to picture local citizens lining up to have their hands assessed for sufficient character to serve as models. But who painted them, and when?

I know the hands are intended to lead the visitor to the next chapel, but the otherworldly nature of the frescoes also point the way to more of Italy with all its mysteries and curiosities that can never be fully comprehended.

Published on October 03, 2013 12:49

September 4, 2013

SHANGHAIED?

“Hello! Where are you from?

Ah, have you seen Sleepless in Seattle?

Please come with us for the folk dancing. It’s just a little way from here. You’ll really enjoy it when we explain everything.”

We were getting annoyed by the young couple who were clinging to us like overcooked noodles. But they kept on with the questions and the importuning: “Please follow us.”

We were getting annoyed by the young couple who were clinging to us like overcooked noodles. But they kept on with the questions and the importuning: “Please follow us.” Finally we walked away. I could see them begin talking to another obviously American couple. Were they trying out a scam or were they just two kids who wanted to earn a little money showing us the sights? Had we been about to be Shanghaied or not? Who knows, but after bushing off the fake designer handbag and DuPont pen for $2.00 crowd we wanted to relax and enjoy more pleasant Shanghai surprises like kites flying in the spring breeze.

We had started our walking tour on the River Promenade across the street from the magnificently-restored buildings of the Bund and across the river from the spectacle of Pudong. Millions of pansies were growing both vertically and horizontally on the river wall and adjoining flower beds. Pink camellias were in bloom. The sun was shining, the temperature pleasant and the smog quotient was low. Among the monumental buildings erected by colonialists who thought their businesses would endure forever was the famous Peace Hotel, our goal for an evening on the town.

The flashy and sureal neon-lit Tourist Tunnel under the Huangpu River to Pudong zipped us off to a world of new architecture, Ferraris, and French and Italian designer shops.

The flashy and sureal neon-lit Tourist Tunnel under the Huangpu River to Pudong zipped us off to a world of new architecture, Ferraris, and French and Italian designer shops.

The ear-popping elevator ride to the 88th floor of the Jin Mao Tower, already dwarfed by taller skyscrapers, allowed for a vertigo view of the city of more than thirteen million and a voyeuristic peek through the well in the center of the observation deck into the atrium of the Grand Hyatt Hotel, on floor 53 far. below. Awe-inspiring but charmless.

So much more pleasant to spend an afternoon strolling in the Yu Yuan Gardens. On a previous visit the crowds were so thick we couldn’t see anything but this time, early spring when the weeping willows trailing their branches into the water were coming into leaf, we had the gardens nearly to ourselves. The tea house and other buildings with upturned roofs looking like smiles, the dragon wall, rockeries and the koi ponds gave us a taste of the Chinese contemplative life, originally available to the one percent but now waiting for us. How different from the very rich in Pudong.

So much more pleasant to spend an afternoon strolling in the Yu Yuan Gardens. On a previous visit the crowds were so thick we couldn’t see anything but this time, early spring when the weeping willows trailing their branches into the water were coming into leaf, we had the gardens nearly to ourselves. The tea house and other buildings with upturned roofs looking like smiles, the dragon wall, rockeries and the koi ponds gave us a taste of the Chinese contemplative life, originally available to the one percent but now waiting for us. How different from the very rich in Pudong.

Shanghai’s expatriate population before World War II has been the stuff of countless novels. We were determined to get a tiny taste by enjoying an evening at the Jazz Bar in the Peace Hotel, built in 1930, now owned by the Fairmont. The splendid lobby with stained glass dome was decorated with silver panels showing old Shanghai. Art-Deco sculptures decorated tables.

Members of the famous jazz band looked as though they had been around since the 1930s (although their average age is "only" 77) and the music wasn’t the best, but oh how easy it was to imagine half-listening to Cole Porter songs while leaning against the bar. I would be wearing a backless and slinky satin evening gown, sipping a martini and eavesdropping on sinister characters plotting heists, insurrections, opium sales, gun running, and perhaps how to Shanghai a competitor.

Published on September 04, 2013 13:25

August 15, 2013

JORDAN

“Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar” rang out over the city, echoed by calls from other mosques. The sound, the essence of the Middle East, was our wakeup call in golden-hued Amman, and it accompanied us on our week-long tour of Jordan

“Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar” rang out over the city, echoed by calls from other mosques. The sound, the essence of the Middle East, was our wakeup call in golden-hued Amman, and it accompanied us on our week-long tour of JordanWe stood at the entrance to our hotel waiting for Ahmed, our man for a week. Suddenly, a Mercedes pulled up and men in black jumped out brandishing their AK-47s. The next Mercedes arrived, squealing tires as it came to a stop. A young woman in tight jeans bounded out of the driver’s side. She was a Jordanian princess, a representative of modern Jordan who looked nothing like the drab and dumpy women dressed in headscarves and long coats or gowns we were soon to see outside the city.

Ahmed arrived in a more subdued fashion. We loaded up and climbed in, driving north to Jerash. As we drove, he valiantly tried to teach us some Arabic, mostly on the order of hello and goodbye. (We had already mastered “thank you,” shokran.) Watching the dry scenery pass, we repeated assalaamu alaykoom, wa alaykoom asalaam and ma assalaamehover and over to each other until we began to sound like wind-up toys. Meanwhile, Ahmed talked to his friends on his cell phone with one hand on the steering wheel. Every one of these frequent conversations started with “ciao,” and finished with “ok, bye-bye.” After telling us about his stay in Rome, we switched to a mixture of Italian and English always punctuated with our by now fluent hello and goodbye in Arabic.

On our way to Jerash we passed one of the enormous refugee camps housing generations of Palestinians who fled or were displaced from Israel. The inhabitants are not likely to go anyplace, being a convenient excuse for the endless political maneuvering in that part of the world. Meanwhile, they lived marginal lives, depending on handouts and other aid to counteract the massive unemployment and the burgeoning population.

Our first stop was the deserted Ottoman village of Umm Qais where we stood on a terrace gazing at the Golan Heights, the Sea of Galilee and the city of Tiberias in Israel, all off-limits to Palestinian exiles. On our trip to Israel we had ascended halfway up these Heights where we stopped at a viewpoint with the small country spread out before us. Now, in Jordan we were looking at the other side of the coin, standing where homesick Palestinians came to look at their former homeland.

Jerash is a better preserved Roman city than many in Italy. We meandered in the hot sun gazing at the ruins of temples, theatres, and Hadrian’s Arch along with Byzantine churches with their intricate mosaic floors still showing through the dust. We rested in the shade of the columns in the Oval Plaza. A breeze made the columns sing as they moved ever so slightly to ease the pressure of wind or earthquake, exactly as the Roman builders intended. The gaps were large enough between some of the sections of column we could have inserted a piece of paper in between. They reminded me of the spaces between the stones at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem filled with paper inscribed with prayers. After we left, I wished I had slipped a note into one of the gaps asking (unrealistically) for peace.

Jerash is a better preserved Roman city than many in Italy. We meandered in the hot sun gazing at the ruins of temples, theatres, and Hadrian’s Arch along with Byzantine churches with their intricate mosaic floors still showing through the dust. We rested in the shade of the columns in the Oval Plaza. A breeze made the columns sing as they moved ever so slightly to ease the pressure of wind or earthquake, exactly as the Roman builders intended. The gaps were large enough between some of the sections of column we could have inserted a piece of paper in between. They reminded me of the spaces between the stones at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem filled with paper inscribed with prayers. After we left, I wished I had slipped a note into one of the gaps asking (unrealistically) for peace.As we drove along a winding road on the way to the Dead Sea, men riding small donkeys and others leading camels accompanied us. The road descended, down and down to the lowest point on earth. Instead of crabbed veterans bobbing in the mineral-thickened water trying to ease their wounds on the Israeli side, women covered in black with only their kohl-ringed eyes on view sat in the shade of the hotel terrace. Gloves covered what little could have showed below the jet-beaded sleeves of their elegant gowns of finely woven wool. While they chatted, their husbands and children relaxed nearby, enjoying their freedom to splash and float. As night fell gardeners watered the lush gardens flourishing in an unforgiving environment.

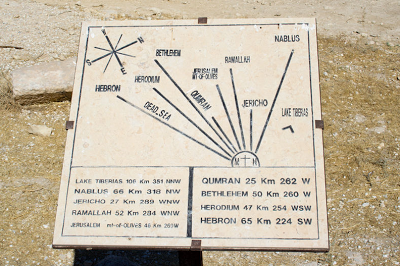

Jordan was like Israel in its archeological sites, marvelous Roman ruins, early Christian churches, Crusader castles and those built by Salah ad-Din. But it also had Ottoman villages, some falling into ruins like one overlooking the Sea of Galilee and others, like Taybet Zamen, where we stayed in Petra, restored. We passed the site of Herod the Great’s fortress, where Salome danced and demanded the head of John the Baptist. Dried grasses surrounding the few stones blew in the wind and kestrels wheeled overhead in the updrafts from the Dead Sea. We stood on Mount Nebo, where Moses viewed the Promised Land, dying before he could cross the Jordan. Near the Byzantine churches with ornate mosaic floors overlooking the barren landscape, a small stand had fossil seashells for sale. Souvenirs of a site even older than Moses, they continue to remind me of this ancient place.

Jordan was like Israel in its archeological sites, marvelous Roman ruins, early Christian churches, Crusader castles and those built by Salah ad-Din. But it also had Ottoman villages, some falling into ruins like one overlooking the Sea of Galilee and others, like Taybet Zamen, where we stayed in Petra, restored. We passed the site of Herod the Great’s fortress, where Salome danced and demanded the head of John the Baptist. Dried grasses surrounding the few stones blew in the wind and kestrels wheeled overhead in the updrafts from the Dead Sea. We stood on Mount Nebo, where Moses viewed the Promised Land, dying before he could cross the Jordan. Near the Byzantine churches with ornate mosaic floors overlooking the barren landscape, a small stand had fossil seashells for sale. Souvenirs of a site even older than Moses, they continue to remind me of this ancient place. Not far from Petra we came upon a man wearing the red-checked keffiyeh sitting astride his horse high on a hill watching us. Maybe he was the reincarnation of Lawrence of Arabia or a member of the Desert Legion. Whoever he was, like the muezzin’s call, the sight was an indelible part of my vision of the Middle East. Near the tourist complex of Petra black goat hair Bedouin tents stretched out in canyons. The Bedouin's flocks of goats and sheep grazed in the sparse vegetation nearby as the light faded. We arrived after sunset, grateful to relax in our old Ottoman home, complete with a sybaritic bath. The other occupants of the hotel complex seemed to be a group of Israelis who kept close together in the restaurant. They looked uncomfortable, out of their element.

The following morning I opened the door of our room. Before me was an endless sea of rocks fading slowly into the haze of an impenetrable desert. How caravans found their way to the fabled “rose-red city half as old as time” was beyond my comprehension. Three days of walking and climbing didn’t begin to complete our explorations. The sandstone used for the buildings and rock carved tombs are shot with ribbons of rose, blue, green, red, and yellow. The architecture is a felicitous combination of Roman and Assyrian elements: columns, architraves and ziggurats. Who designed them, who carved them, who lived in them and who was buried there? I wanted more time to sit on one of the cliffs and dream of this ancient civilization and of the caravans that had passed by, the camels laden with silks and spices slowly walking along on their endless journeys.

The following morning I opened the door of our room. Before me was an endless sea of rocks fading slowly into the haze of an impenetrable desert. How caravans found their way to the fabled “rose-red city half as old as time” was beyond my comprehension. Three days of walking and climbing didn’t begin to complete our explorations. The sandstone used for the buildings and rock carved tombs are shot with ribbons of rose, blue, green, red, and yellow. The architecture is a felicitous combination of Roman and Assyrian elements: columns, architraves and ziggurats. Who designed them, who carved them, who lived in them and who was buried there? I wanted more time to sit on one of the cliffs and dream of this ancient civilization and of the caravans that had passed by, the camels laden with silks and spices slowly walking along on their endless journeys.  But our time was done. We took the die-straight Desert Highway though the empty landscape back to Amman, another of my travels finished too soon.

But our time was done. We took the die-straight Desert Highway though the empty landscape back to Amman, another of my travels finished too soon.photos courtesy of Wikipedia

Published on August 15, 2013 09:02

July 2, 2013

FOOTSTEPS ON THE GREAT WALL

Instead of the sound of millions of tourist feet pounding the section of the Great Wall closest to Beijing, there were only 160 – that is, those belonging to 79 people and me to the section known as Hangyaguan, two and a half hours from the port of Tianjin.

We stopped for an early lunch in Jixian, a scruffy city and a marked contrast to glitzy Shanghai. Piles of rubble were everywhere, as if the city had been bombed. In reality, it was the mark of land cleared by the Chinese government for high-rise apartments as it prepares to relocate 250 million rural peasants to urban environments (and very uncertain futures). Many citizens rode bicycles but some used odd pedicabs.

We stopped for an early lunch in Jixian, a scruffy city and a marked contrast to glitzy Shanghai. Piles of rubble were everywhere, as if the city had been bombed. In reality, it was the mark of land cleared by the Chinese government for high-rise apartments as it prepares to relocate 250 million rural peasants to urban environments (and very uncertain futures). Many citizens rode bicycles but some used odd pedicabs.The hotel, our lunch venue, may have been grand at one time with elegant chandeliers hanging in the stairways. My view, as I trudged up the stairs to the ballroom/restaurant, was of fixtures so coated with black grease only a dim light passed through the prisms. The table was laid with the typical lazy Susan in the middle. Platter after platter arrived at the tables, with rice, the least expensive food, served last to signify that there were enough vegetables, chicken and pork to satisfy everyone beforehand. And, despite the dreary surroundings, the food was excellent.

Meal finished, it was time to leave the flat plain and enter the hills to the 26 miles remaining of the Hangyaguan, Yellow Cliff Pass section, of the Great Wall. On the way, the bus wound through marble and granite hills set with cypress, juniper and pines looking exactly like a scroll painting on silk. We passed several not-at-all picturesque impoverished hamlets where a few shops sold chunks of contorted rocks, so beloved by the Chinese for their gardens. A few people were cooking with charcoal in their walled courtyards, otherwise the settlements seemed nearly deserted. Perhaps the other inhabitants had already been relocated.

Finally, the Great Wall was before us. And great it is – stretching into the distance in either direction from the entrance. Workers were chipping away at worn timbers and crumbling stone on several of the watch towers in an effort to keep a structure, begun in AD 550 and reinforced at various times between 1368 and 1644, from collapsing. Our energies were concentrated on actually climbing the steep stone steps and paths, incredibly now the site of an annual marathon that attracted some 2000 runners last year. It’s hard to imagine a place where millions died building and rebuilding a structure now being used for tourism and sport.

As I walked on the crenelated ramparts and climbed to the towers I tried to imagine the lives of the soldiers and watchmen and the desperate peasants who died in uncounted numbers building and maintaining the wall. How many in this section alone, and how many on the entire length of the wall, over 4000 miles stretching from the sea to Tibet. In the end the wall was ineffective, breached by the Mongols in the 13thcentury and the Manchu in the 17th. Only a few sections have been fully restored, the remainder left for time to take its course.

Not being a marathoner, I climbed until I was huffing and puffing before stopping to watch the workers replacing timbers and stones on the towers.

As the late afternoon chill set in it was time to turn back to see the Hundred Generals Stele Forest and Longevity Garden, empty except for a lone Chinese man, and then to eye the selection of trinkets and food set out by locals who numbered about as many as our group.

As the late afternoon chill set in it was time to turn back to see the Hundred Generals Stele Forest and Longevity Garden, empty except for a lone Chinese man, and then to eye the selection of trinkets and food set out by locals who numbered about as many as our group.  Besides the usual junk, there were copies of Mao’s Little Red Book and a few posters, local “wine” and dried fruits, especially what looked like sliced crabapples but was probably jujube. The vendors and their chubby-cheeked children were all smiles as the members of our group bought over-priced souvenirs.

Besides the usual junk, there were copies of Mao’s Little Red Book and a few posters, local “wine” and dried fruits, especially what looked like sliced crabapples but was probably jujube. The vendors and their chubby-cheeked children were all smiles as the members of our group bought over-priced souvenirs. Everyone happy, cold and tired, it was time to head out. As we left, I took a last look across the Juhe River to see the other section of the wall rising nearly vertically up the distant hills and into the spring evening mist.

Everyone happy, cold and tired, it was time to head out. As we left, I took a last look across the Juhe River to see the other section of the wall rising nearly vertically up the distant hills and into the spring evening mist.

Published on July 02, 2013 11:44

June 3, 2013

SUNDAY AFTERNOON IN NAHA

The kid was twanging what looked like a three-stringed banjo covered with snake skin. Behind him the windows of the music store were filled with taiko drums of various sizes. Definitely not Bluegrass Country or Bourbon Street even though the music had some similar sounds. Instead, it was Kokusai-dori on a Sunday afternoon in Naha, Okinawa, capital of the southernmost of Japan’s prefectures, the Ryukyu archipelago. The “banjo” is actually a sanshin and the music is called shima uta, an Okinawan roots-style now popular throughout Asia and on Youtube. Restaurants and bars advertised live music – tempting but first I wanted to look at Okinawan crafts and foods.

The kid was twanging what looked like a three-stringed banjo covered with snake skin. Behind him the windows of the music store were filled with taiko drums of various sizes. Definitely not Bluegrass Country or Bourbon Street even though the music had some similar sounds. Instead, it was Kokusai-dori on a Sunday afternoon in Naha, Okinawa, capital of the southernmost of Japan’s prefectures, the Ryukyu archipelago. The “banjo” is actually a sanshin and the music is called shima uta, an Okinawan roots-style now popular throughout Asia and on Youtube. Restaurants and bars advertised live music – tempting but first I wanted to look at Okinawan crafts and foods. Sunday is definitely not a day of rest in Naha. The main shopping street in the city center, turned into a mile-long pedestrian zone for the day, was hopping with shoppers from Taiwan, China, or from more northerly parts of Japan seeking a sub-tropical holiday.

The street was lined with fast food restaurants, liquor stores, ATMs, cheap jewelry and clothing; the usual commercial items found in other Japanese cities, although with a more warm-weather aspect in light of the climate that is more like Hawaii or Southern California.

The street was lined with fast food restaurants, liquor stores, ATMs, cheap jewelry and clothing; the usual commercial items found in other Japanese cities, although with a more warm-weather aspect in light of the climate that is more like Hawaii or Southern California. My goal was off the main street: the Heiwa-dori Shopping Arcade and Makishi Public Market founded by war widows after the hideous Battle of Okinawa where after 82 days 13,000 American soldiers and 250,000 Japanese soldiers and civilians lost their lives in the carnage.

My goal was off the main street: the Heiwa-dori Shopping Arcade and Makishi Public Market founded by war widows after the hideous Battle of Okinawa where after 82 days 13,000 American soldiers and 250,000 Japanese soldiers and civilians lost their lives in the carnage.The arcade was filled with shops, each one worthy of a long look: beautifully packaged tropical fruit, designer home styles, and clothing made from the wonderful textile designs unique to the island – rather like Hawaiian but with smaller repetitive patterns.

Should I buy some of the strong Awamori liquor made with long-grain rice and a black mold? Or have my palm read – it was cheap, only 300 yen? But I was too doubtful about the drink and can’t understand Japanese so I passed into the food market, a cornucopia of unfamiliar seafood and produce (except for the stacks of SPAM labeled in Japanese).

The fish displays looked like rainbows as they rested on ice near prawns ready for Sunday dinner. Different than the steel-gray fish from my familiar cold North Pacific waters, they were so beautiful they belonged in an aquarium rather than a pot on the stove or on a grill. Large tanks held bright-red lobster and crab; prawns rested on ice near the fish; containers of small dried fish along with other pickled and dried unknown items filled several stalls. The meat counters were showing various cuts of pork, the most common meat eaten on the island. One whole shop was devoted to what looked like hard brown bananas. When I asked what they were the vendor held one up and grated flakes into a bowl. She said they were flakes of bonito tuna compressed into a size and shape easy to hold when preparing them as seasoning for a bowl of noodles and broth.

The fish displays looked like rainbows as they rested on ice near prawns ready for Sunday dinner. Different than the steel-gray fish from my familiar cold North Pacific waters, they were so beautiful they belonged in an aquarium rather than a pot on the stove or on a grill. Large tanks held bright-red lobster and crab; prawns rested on ice near the fish; containers of small dried fish along with other pickled and dried unknown items filled several stalls. The meat counters were showing various cuts of pork, the most common meat eaten on the island. One whole shop was devoted to what looked like hard brown bananas. When I asked what they were the vendor held one up and grated flakes into a bowl. She said they were flakes of bonito tuna compressed into a size and shape easy to hold when preparing them as seasoning for a bowl of noodles and broth.The produce section was full of bitter melon, cabbage, taro, onions, sweet potatoes, tofu, noodles, and dried seaweed along with pineapple, papayas, mangoes, passion fruit, guavas and citrus all waiting to become the local cuisine – a mix of Chinese, Japanese and Southeast Asian in keeping with Okinawa’s history of a cultural crossroads.

By this time it was clear that all this food made me hungry. It was time for a Sunday feast. Now where was that restaurant with the music? The one with Orion beer, bowls of soba noodles and champuru – bitter gourd stir-fried with pork and egg. Yes!

By this time it was clear that all this food made me hungry. It was time for a Sunday feast. Now where was that restaurant with the music? The one with Orion beer, bowls of soba noodles and champuru – bitter gourd stir-fried with pork and egg. Yes!

Published on June 03, 2013 07:19

May 4, 2013

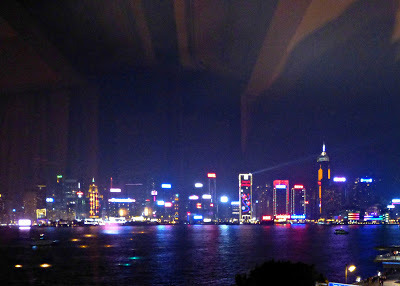

TEMPLE STREET NIGHT MARKET

One evening in Hong Kong we found our way to the night market stretching many blocks from Jordan Road to Kansu Street in a crowded area of Kowloon near the main arterial, Nathan Road. The transition from the glittering waterfront bejeweled with lights and high-end hotels and shops to what seemed a darker and more real corner of the city was startling. Instead of Gucci, Prada wares and the Peninsula Hotel, we entered the world of Wing Hing Hostel and the Dragoon Francais Tailor Co.

We had strolled through the laid-back (dare I even say genteel) market at Stanley with high-style clothing and even art, a seeming outpost of Colonial times, but now, the moment we entered the archway on Temple Street we were in real China.

The street was lined with stalls and their shouting proprietors desperate to sell their wares, all of which were repeated from one stand to another – CDs of Chinese opera or pirated pop from around the world, souvenir trinkets, sunglasses, smartphone cases and cheap tee-shirts decorated with Mao’s plump face or the “I Love Hong Kong” logo. Not must-have items for either of us but fun to look at the endless products of Chinese efforts to make a living.

Far more interesting was the dark sidewalk on the far side of the market and the bustling side streets crammed with outdoor restaurants. When we walked along the back side of the market, a more realistic picture of life for the poorer inhabitants emerged. The street is lined with old two- and three-story tenement buildings, all in various states of disrepair. Dingy stairwells lit by a single low-watt bulb cast shadows making me think of plots for a novel (A World of Suzie Wong knockoff?)Scantily-dressed young women stood nearby waiting for customers.

In between the forbidding stair entrances we looked through the dusty windows of tiny shops on the ground level: small altars and statues of Buddha, Chinese medicinal herbs, a barber shop, odds and ends of electrical supplies and ever more CDs. Closer to the main market stalls, vendors and their families sat around electric pots bubbling with meat and vegetable mixtures eating and listening to radios.

The streets leading toward Nathan Road in the other direction were alive with people, tourists and locals, all outside in the warm night for dinners or snacks. Busy outdoor restaurants offered ducks, chickens or other indeterminate flesh.

Other venues specialized in fresh seafood and wiggling fish kept alive by pumping water into plastic tubs. Customers sat at tables with bowls held to mouths, chop-sticks in motion.

Other venues specialized in fresh seafood and wiggling fish kept alive by pumping water into plastic tubs. Customers sat at tables with bowls held to mouths, chop-sticks in motion.  Not a destination I would recommend for bargains but definitely a location to see what Hong Kong has to offer in the way of a very small look at China.

Not a destination I would recommend for bargains but definitely a location to see what Hong Kong has to offer in the way of a very small look at China.

Published on May 04, 2013 16:22

March 31, 2013

AN AUSPICIOUS DAY: A Shinto Wedding in Osaka

When I heard that it was an auspicious day for baptisms and weddings it seemed a good time to head for Osaka’s Sumiyoshi Taisha Shinto shrine despite the grey clouds and spring showers. The shrine, which contains a temple designated as one of Japan’s national treasures, is dedicated to various interesting and helpful deities, called kami, who ensure safe travel, good fortune in marriage, safe childbirth, business prosperity, family welfare, military valor and beauty. Because of its association with marriage and family it is an especially favored spot for traditional weddings.

To enter the complex the visitor or worshipper passes by stone lanterns, through a tori gate marking the boundary between the everyday world and the infinite, and crosses the steep vermilion-painted Taiko-bashi bridge arching over a pond. The first stop is at the temizuya to wash hands and face for purification using a bamboo dipper for water collected in a basin supplied by a stone rabbit. Just outside the second tori gate ancient cypress trees are hung with shimenwa,ropes made of rice straw decorated with white paper streamers marking sacred areas.

To enter the complex the visitor or worshipper passes by stone lanterns, through a tori gate marking the boundary between the everyday world and the infinite, and crosses the steep vermilion-painted Taiko-bashi bridge arching over a pond. The first stop is at the temizuya to wash hands and face for purification using a bamboo dipper for water collected in a basin supplied by a stone rabbit. Just outside the second tori gate ancient cypress trees are hung with shimenwa,ropes made of rice straw decorated with white paper streamers marking sacred areas.

I strolled the gravel-paved grounds peering into various shrines; inspected the colorful sake barrels donated to the temple for ceremonial use; watched youngsters practicing drumming for an upcoming festival; looked for pebbles within a fenced area to see if I could found one marked with “five,” “big,” or “power” for personal charms (I didn’t); and made a quick prayer to the symbols of business fortune – a row of cats.

The ancient couple guarding them pantomimed the correct prayer posture: Proceed to the altar, stand straight; bow deeply twice; put palms together; clap hands twice; pray for my wish to come true; lower hands and bow once more. (No results yet I'm sorry to say).

Finished praying and making my donation I continued to walk among the small orange and vermilion shrines until I came to a temple where a group of women were standing in front of the open entrance watching a wedding. Many of the onlookers wore kimonos and held traditional umbrellas to ward off the intermittent showers. I joined the group.

I could hear the sound of a drum and flutes playing what sounded to me mournful and tuneless music while two priestesses with headresses of pine and what looked like cranes moved in a slow ritual dance accompanied by musicians in green robes. The white-robed, black-hatted priest intoned words of a marriage rite. The bride and groom had their backs to us of course but through an open side door I could see a few family members sitting on the benches on each side watching the formalities.

I could hear the sound of a drum and flutes playing what sounded to me mournful and tuneless music while two priestesses with headresses of pine and what looked like cranes moved in a slow ritual dance accompanied by musicians in green robes. The white-robed, black-hatted priest intoned words of a marriage rite. The bride and groom had their backs to us of course but through an open side door I could see a few family members sitting on the benches on each side watching the formalities.

After the union was solemnized in what seemed to be a stately and timeless ceremony the couple and their family moved to the courtyard for photos and congratulations. The beautiful bride was swathed in a white satin kimono with a hood while the groom wore a tuxedo. Two of the other men were elegant in formal samurai dress complete with fans. It was a picturesque combination of ancient and modern.

After the union was solemnized in what seemed to be a stately and timeless ceremony the couple and their family moved to the courtyard for photos and congratulations. The beautiful bride was swathed in a white satin kimono with a hood while the groom wore a tuxedo. Two of the other men were elegant in formal samurai dress complete with fans. It was a picturesque combination of ancient and modern.

I joined with the well-wishers to hope that it was indeed an auspicious day for the couple as it had been when I, too, was married at a spring ceremony in another time and place.

Photos by author with the exception of the tori gate which is from Wikipedia Commons

Published on March 31, 2013 10:19

February 15, 2013

YOU NEVER KNOW WHAT WILL HAPPEN

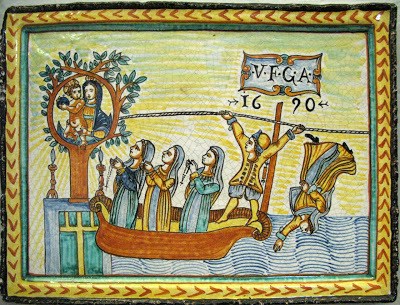

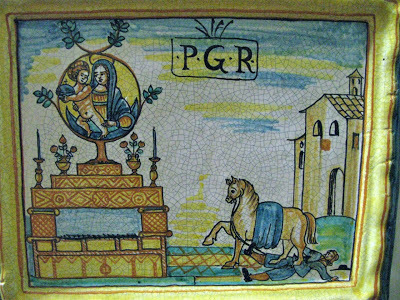

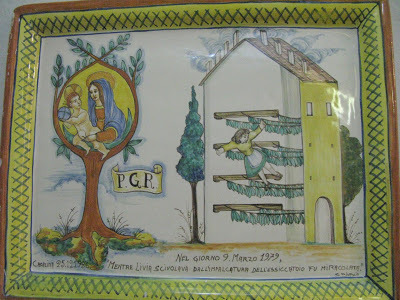

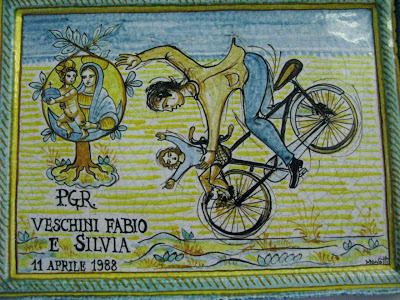

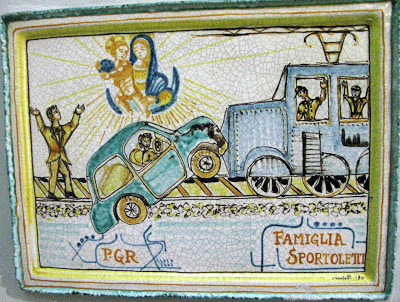

The Madonna delBagno is a small church nestled inconspicuously near the main road to Deruta. It is famous for painted ceramic tiles affixed to the walls by worshippers in thanks to the Virgin for rescue from near death.

The Madonna delBagno is a small church nestled inconspicuously near the main road to Deruta. It is famous for painted ceramic tiles affixed to the walls by worshippers in thanks to the Virgin for rescue from near death.  In the 17thcentury, an itinerant merchant, one Cristoforo Merciaro, or Christopher the Peddler, found a ceramic fragment on the ground. Fourteen years earlier, a Franciscan monk had placed the little piece, painted with a primitive image of the Madonna and Child, in an oak tree for safekeeping.

In the 17thcentury, an itinerant merchant, one Cristoforo Merciaro, or Christopher the Peddler, found a ceramic fragment on the ground. Fourteen years earlier, a Franciscan monk had placed the little piece, painted with a primitive image of the Madonna and Child, in an oak tree for safekeeping. The story continues: The merchant returned the fragment to its place and prayed to the image to save his dying wife, whom he did not expect to see alive again. When he returned home from his travels he found her not just alive but “out of bed in perfect health, sweeping the floors.” This housekeeping miracle gave rise to the fragment’s veneration.

The church, built to commemorate the event, became a magnet for ceramic artisans from nearby Deruta, a center for majolica-decorated terracotta tableware and decorative items made there since the Middle Ages.

The church, built to commemorate the event, became a magnet for ceramic artisans from nearby Deruta, a center for majolica-decorated terracotta tableware and decorative items made there since the Middle Ages.  The local inhabitants expressed gratitude for their own personal miracles by making ceramic ex-votos thanking the Madonna for her aid in times of danger. The original image of Madonna and Child, painted on a broken cup, still survives as shown above. Its depiction of a small Madonna holding a large fat Child who in turn holds a globe is a delight to all mothers. The colors are simple blue and yellow on a white background, the predominant colors on traditional Deruta ceramics.

The local inhabitants expressed gratitude for their own personal miracles by making ceramic ex-votos thanking the Madonna for her aid in times of danger. The original image of Madonna and Child, painted on a broken cup, still survives as shown above. Its depiction of a small Madonna holding a large fat Child who in turn holds a globe is a delight to all mothers. The colors are simple blue and yellow on a white background, the predominant colors on traditional Deruta ceramics.

Glazed terra cotta plaques made by the local artisans eventually covered the small church’s walls. These tiles had a partial miracle of their own: about 200 were stolen in 1980, but about half were recovered to grace the walls again. There are now about 600 plaques covering every aspect of human misery averted by the Madonna’s grace. Although varying in shape they all have a disaster scene, the Madonna and Child, usually in a tree, and the initials P.G.R. sometimes written out as Per Grazia Ricevuta, for grace received.

Glazed terra cotta plaques made by the local artisans eventually covered the small church’s walls. These tiles had a partial miracle of their own: about 200 were stolen in 1980, but about half were recovered to grace the walls again. There are now about 600 plaques covering every aspect of human misery averted by the Madonna’s grace. Although varying in shape they all have a disaster scene, the Madonna and Child, usually in a tree, and the initials P.G.R. sometimes written out as Per Grazia Ricevuta, for grace received.Folk art in style, they depict scenes of people being miraculously saved from falls off roofs, tobacco drying sheds or out of trees, attack by animals or bandits, floods, fire, lightning, earthquakes, plague, or the dangers of childbirth.

While most plaques are from the 17th and 18thcentury, reflecting the rigors of life in those times, survival from more contemporaneous disasters are also memorialized, especially auto accidents. Grateful familis have even commissioned tiles with scenes from World War II as well as the miseries of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

While most plaques are from the 17th and 18thcentury, reflecting the rigors of life in those times, survival from more contemporaneous disasters are also memorialized, especially auto accidents. Grateful familis have even commissioned tiles with scenes from World War II as well as the miseries of Bosnia-Herzegovina.All the tiles are colorful and hopeful, but also a reminder that whatever can go wrong will go wrong. I thought about ordering up one to celebrate my escape from death when I fell in the Rome subway or our avoidance of jail after the crash with the Carabinieri.

Photo Credits: top photos of church from Creative Commons; photo of Madonna & Child by Judith Works; photos of tiles courtesy of Lars Bjorkman

Photo Credits: top photos of church from Creative Commons; photo of Madonna & Child by Judith Works; photos of tiles courtesy of Lars BjorkmanThis story originally appeared in Coins in the Fountain, a memoir of living in Italy

Published on February 15, 2013 08:38