Mary Cronk Farrell's Blog

February 28, 2025

Wash, Rinse, Re—Stop! Here's How You Bring the Status Quo to a Standstill

The washerwomen in Atlanta, Georgia, were so low on the ladder, they hung on the bottom rung by a clothespin. They knew they deserved to climb higher.

In the summer of 1881, a few of them threw out the wash-water, leveraged the little clout they had, and brought the powers-that-be in the City of Atlanta to their knees, or more accurately, their dirty drawers.

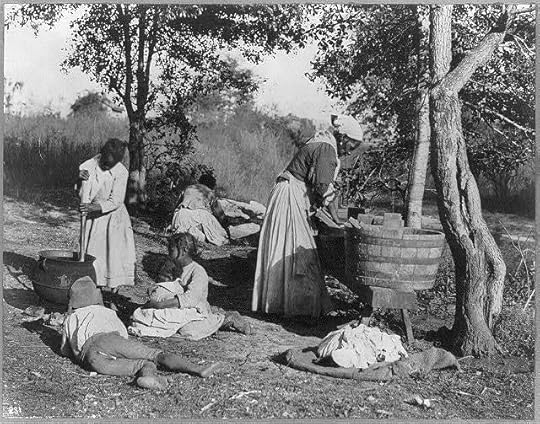

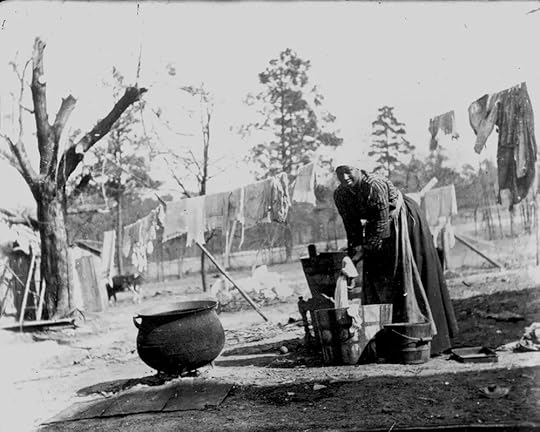

Woman African American woman washing laundry outdoors in a yard in or near Richmond County, Ga., in late 19th century. Only 15-20 years before, these Black women were enslaved by the very people who now employed them to do their wash. Though a constitutional amendment guaranteed their freedom, the white families in Atlanta still had the Black women trapped.

Woman African American woman washing laundry outdoors in a yard in or near Richmond County, Ga., in late 19th century. Only 15-20 years before, these Black women were enslaved by the very people who now employed them to do their wash. Though a constitutional amendment guaranteed their freedom, the white families in Atlanta still had the Black women trapped.

Until the washerwomen exercised their most powerful weapon: unity.

They wrote the mayor, "We mean business...or no washing."

Let me paint a picture of Atlanta in 1881. Destroyed by General Sherman at the end of the Civil War, the city was rising from the ashes. In fact they called it the Phoenix City of the South.

In truth is was struggling to rise above the sewage. The only water system served wealthy white neighborhoods in the Central District, where big houses sat back from the dirty streets.

City boosters advertised Atlanta's plentiful, subservient workforce in an effort to entice northern businesses. New industry arrived, including slaughter houses and stock pens of pigs.

But leaders failed to extend water and sewage lines for most residents. Atlanta’s poor and working class families lived in row houses, tenements, and shanties on the outskirt low lands. Everything ran down hill.

The neighborhoods suffered seasonal flooding and poor drainage. Outdoor privies contaminated wells and springs. Dead animals rotted in the street where they fell. And the better-off townsfolk dumped their household garbage in the poor neighborhoods.

In short, the whole city stank. Here's one of the better streets in the outskirts of town.

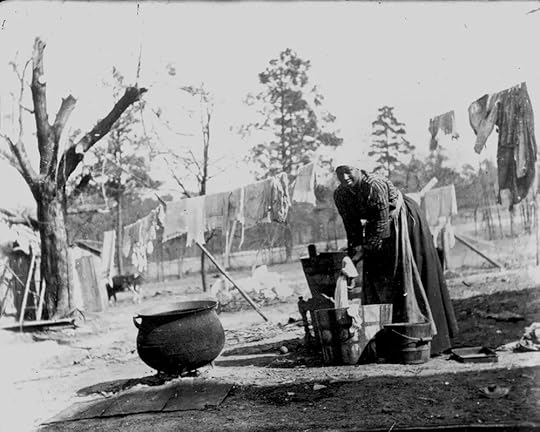

Black neighborhood in Atlanta, Georgia. Library of Congress photo. It was up to the washerwomen to keep at least the clothes clean. Ninety-eight percent of Atlanta’s Black women worked as domestics for former slave owners, the largest number washing laundry. They started work as young as ten, and could not count on retirement.

Black neighborhood in Atlanta, Georgia. Library of Congress photo. It was up to the washerwomen to keep at least the clothes clean. Ninety-eight percent of Atlanta’s Black women worked as domestics for former slave owners, the largest number washing laundry. They started work as young as ten, and could not count on retirement.

Black women earned low wages for long hours cooking, cleaning and caring for kids, all the time under the oppressive eye of their employers. Laundresses had a bit more freedom, working at their own homes or neighborhoods and on their own schedules, as much as one can schedule work that goes on all day every day.

A typical washerwoman started Monday, picking up dirty bundles from the homes of white families and cleaning them during the week to return before Sunday. Hiring a washerwoman was affordable even for working class whites.

It was hard labor, customers were demanding and if they shorted the pay, a woman had no recourse. Woman washing clothes with children’s help circa 1900. Library of Congress. Large cotton mills in the north made cloth readily available and much cheaper than ever. People had more clothes and changed them more often. Each family had mounds of laundry: dresses, shirts and pants, plus tablecloths, napkins, dirty sheets, underwear and diapers.

Woman washing clothes with children’s help circa 1900. Library of Congress. Large cotton mills in the north made cloth readily available and much cheaper than ever. People had more clothes and changed them more often. Each family had mounds of laundry: dresses, shirts and pants, plus tablecloths, napkins, dirty sheets, underwear and diapers.

First water had to be carried from the pump and heated in an iron pot over a fire.Then it was poured in a tub where the washerwoman rubbed the clothes on the washboard with soap, rinsed them and ran everything through a ringer the children cranked by hand. Next, all the laundry was hung on the line to dry.

Someone had to keep hauling water from the pump to keep the pot on the fire full and boiling. The women provided their own soap, making it at home from lye and starch from wheat bran. And when the clothes were dry, the woman heated irons in the coals and ironed them, taking care to press collars and pleats.

"I could clean my hearth good and nice and set my irons in front of the fire and iron all day [with]out stopping....I cooked and ironed at the same time," said laundress Sarah Hill.

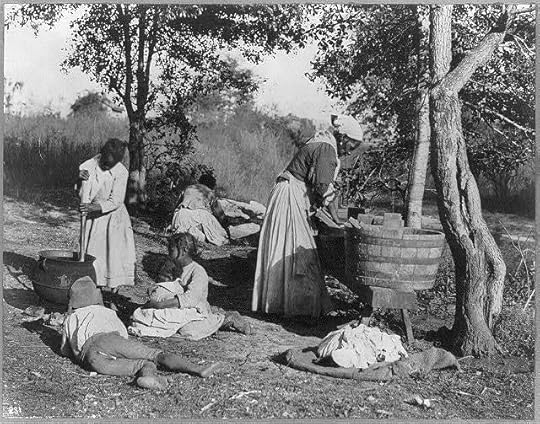

Woman African American woman washing laundry outdoors in a yard in or near Richmond County, Ga., in late 19th century, Robert E. Williams Photographic Collection, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries. handful of Atlanta washerwomen got together in July, 1881, and formed a trade union. They called themselves The Washing Society.

Woman African American woman washing laundry outdoors in a yard in or near Richmond County, Ga., in late 19th century, Robert E. Williams Photographic Collection, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries. handful of Atlanta washerwomen got together in July, 1881, and formed a trade union. They called themselves The Washing Society.

The women needed higher pay. Working their fingers raw and their backs bent, they could hardly feed their families. They also wanted more autonomy and respect.

The Washing Society decided to demand a uniform rate of one dollar for every dozen pounds of wash. They went door-to-door recruiting members on all sides of town. Black ministers helped spread the word and the trade union called a mass meeting to organize a strike.

A few white customers agreed to meet the society's demands. Others sent their laundry out of town.

The newspaper declare the laundresses were demanding “unreasonably high prices.” However, within three weeks, membership in the society grew from 20 to 3000, and dirty clothes piled up in homes throughout the city.

The women rallied nightly for speeches and prayer meetings, bolstering each other's persistence.

"[A] "thoroughly organized association...." the Atlanta Constitution wrote: “The Washerwomen's strike is assuming vast proportions and despite the apparent independence of the white people, is causing quite an inconvenience among our citizens.”

There remains almost no documentation of the strike beyond a few newspaper articles and we only know the names of a few strikers because they were arrested as the city applied pressure to end the strike.

Authorities charged Matilda Crawford, Sallie Bell, Carrie Jones, Dora Jones, Orphelia Turner and Sarah A. Collier with disorderly conduct and quarreling and assessed five dollar fine. Apparently, all but one paid and went free. "In the case of Sarah A. Collier," the newspaper reported, "twenty dollars was assessed, and the money not being paid, the defendant’s name was transcribed to the chain-gang book, where it will remain for forty days."

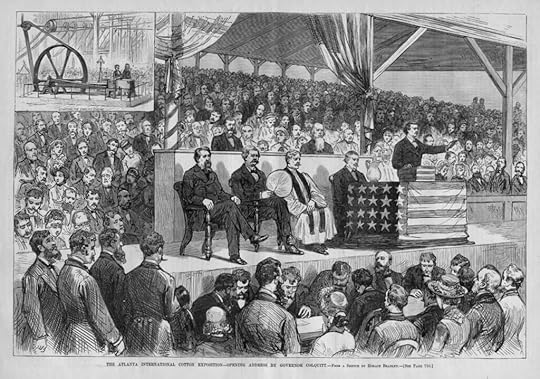

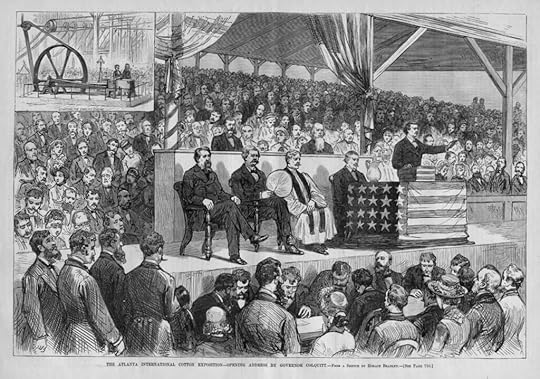

The Washing Society timed it strike in the months before Atlanta was due to host the International Cotton Exposition, an effort by the city to promote investment.

Illustration published in Harper’s Weekly, October 1881. With such a fancy affair on the horizon, city official couldn't have citizens walking around in dirty clothes. They threatened the strikers, floating the possibility of charging members of The Washing Society an annual license fee of $25. In addition, officials tried to eliminate their jobs entirely by offering tax incentives to businessmen to start up steam laundries.

Illustration published in Harper’s Weekly, October 1881. With such a fancy affair on the horizon, city official couldn't have citizens walking around in dirty clothes. They threatened the strikers, floating the possibility of charging members of The Washing Society an annual license fee of $25. In addition, officials tried to eliminate their jobs entirely by offering tax incentives to businessmen to start up steam laundries.

The license would be an enormous expense given the women were lucky to earn eight dollars a month, but they agreed it was worth it for a uniform rate of pay.

The women wrote the city mayor directly: "We the members of our society, are determined to stand to our pledge and make extra charges for washing...and are willing to pay $25 or $50 for licenses as a protection...and will do it before we will be defeated, and then we will have full control of the city’s washing at our own prices."

The letter ended with a promise. "We mean business this week or no washing."

Through united, grassroots organization, Atlanta washerwomen proved themselves a force to be reckoned with. They improved their situation and their income and the strike motivated other black domestic workers, cooks, house servants, nurses and hotel maids to likewise push for wage increases.

Do you want to topple the ladder? Unity and persistence may be the only weapon we have.

In the summer of 1881, a few of them threw out the wash-water, leveraged the little clout they had, and brought the powers-that-be in the City of Atlanta to their knees, or more accurately, their dirty drawers.

Woman African American woman washing laundry outdoors in a yard in or near Richmond County, Ga., in late 19th century. Only 15-20 years before, these Black women were enslaved by the very people who now employed them to do their wash. Though a constitutional amendment guaranteed their freedom, the white families in Atlanta still had the Black women trapped.

Woman African American woman washing laundry outdoors in a yard in or near Richmond County, Ga., in late 19th century. Only 15-20 years before, these Black women were enslaved by the very people who now employed them to do their wash. Though a constitutional amendment guaranteed their freedom, the white families in Atlanta still had the Black women trapped.Until the washerwomen exercised their most powerful weapon: unity.

They wrote the mayor, "We mean business...or no washing."

Let me paint a picture of Atlanta in 1881. Destroyed by General Sherman at the end of the Civil War, the city was rising from the ashes. In fact they called it the Phoenix City of the South.

In truth is was struggling to rise above the sewage. The only water system served wealthy white neighborhoods in the Central District, where big houses sat back from the dirty streets.

City boosters advertised Atlanta's plentiful, subservient workforce in an effort to entice northern businesses. New industry arrived, including slaughter houses and stock pens of pigs.

But leaders failed to extend water and sewage lines for most residents. Atlanta’s poor and working class families lived in row houses, tenements, and shanties on the outskirt low lands. Everything ran down hill.

The neighborhoods suffered seasonal flooding and poor drainage. Outdoor privies contaminated wells and springs. Dead animals rotted in the street where they fell. And the better-off townsfolk dumped their household garbage in the poor neighborhoods.

In short, the whole city stank. Here's one of the better streets in the outskirts of town.

Black neighborhood in Atlanta, Georgia. Library of Congress photo. It was up to the washerwomen to keep at least the clothes clean. Ninety-eight percent of Atlanta’s Black women worked as domestics for former slave owners, the largest number washing laundry. They started work as young as ten, and could not count on retirement.

Black neighborhood in Atlanta, Georgia. Library of Congress photo. It was up to the washerwomen to keep at least the clothes clean. Ninety-eight percent of Atlanta’s Black women worked as domestics for former slave owners, the largest number washing laundry. They started work as young as ten, and could not count on retirement.Black women earned low wages for long hours cooking, cleaning and caring for kids, all the time under the oppressive eye of their employers. Laundresses had a bit more freedom, working at their own homes or neighborhoods and on their own schedules, as much as one can schedule work that goes on all day every day.

A typical washerwoman started Monday, picking up dirty bundles from the homes of white families and cleaning them during the week to return before Sunday. Hiring a washerwoman was affordable even for working class whites.

It was hard labor, customers were demanding and if they shorted the pay, a woman had no recourse.

Woman washing clothes with children’s help circa 1900. Library of Congress. Large cotton mills in the north made cloth readily available and much cheaper than ever. People had more clothes and changed them more often. Each family had mounds of laundry: dresses, shirts and pants, plus tablecloths, napkins, dirty sheets, underwear and diapers.

Woman washing clothes with children’s help circa 1900. Library of Congress. Large cotton mills in the north made cloth readily available and much cheaper than ever. People had more clothes and changed them more often. Each family had mounds of laundry: dresses, shirts and pants, plus tablecloths, napkins, dirty sheets, underwear and diapers.First water had to be carried from the pump and heated in an iron pot over a fire.Then it was poured in a tub where the washerwoman rubbed the clothes on the washboard with soap, rinsed them and ran everything through a ringer the children cranked by hand. Next, all the laundry was hung on the line to dry.

Someone had to keep hauling water from the pump to keep the pot on the fire full and boiling. The women provided their own soap, making it at home from lye and starch from wheat bran. And when the clothes were dry, the woman heated irons in the coals and ironed them, taking care to press collars and pleats.

"I could clean my hearth good and nice and set my irons in front of the fire and iron all day [with]out stopping....I cooked and ironed at the same time," said laundress Sarah Hill.

Woman African American woman washing laundry outdoors in a yard in or near Richmond County, Ga., in late 19th century, Robert E. Williams Photographic Collection, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries. handful of Atlanta washerwomen got together in July, 1881, and formed a trade union. They called themselves The Washing Society.

Woman African American woman washing laundry outdoors in a yard in or near Richmond County, Ga., in late 19th century, Robert E. Williams Photographic Collection, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries. handful of Atlanta washerwomen got together in July, 1881, and formed a trade union. They called themselves The Washing Society.The women needed higher pay. Working their fingers raw and their backs bent, they could hardly feed their families. They also wanted more autonomy and respect.

The Washing Society decided to demand a uniform rate of one dollar for every dozen pounds of wash. They went door-to-door recruiting members on all sides of town. Black ministers helped spread the word and the trade union called a mass meeting to organize a strike.

A few white customers agreed to meet the society's demands. Others sent their laundry out of town.

The newspaper declare the laundresses were demanding “unreasonably high prices.” However, within three weeks, membership in the society grew from 20 to 3000, and dirty clothes piled up in homes throughout the city.

The women rallied nightly for speeches and prayer meetings, bolstering each other's persistence.

"[A] "thoroughly organized association...." the Atlanta Constitution wrote: “The Washerwomen's strike is assuming vast proportions and despite the apparent independence of the white people, is causing quite an inconvenience among our citizens.”

There remains almost no documentation of the strike beyond a few newspaper articles and we only know the names of a few strikers because they were arrested as the city applied pressure to end the strike.

Authorities charged Matilda Crawford, Sallie Bell, Carrie Jones, Dora Jones, Orphelia Turner and Sarah A. Collier with disorderly conduct and quarreling and assessed five dollar fine. Apparently, all but one paid and went free. "In the case of Sarah A. Collier," the newspaper reported, "twenty dollars was assessed, and the money not being paid, the defendant’s name was transcribed to the chain-gang book, where it will remain for forty days."

The Washing Society timed it strike in the months before Atlanta was due to host the International Cotton Exposition, an effort by the city to promote investment.

Illustration published in Harper’s Weekly, October 1881. With such a fancy affair on the horizon, city official couldn't have citizens walking around in dirty clothes. They threatened the strikers, floating the possibility of charging members of The Washing Society an annual license fee of $25. In addition, officials tried to eliminate their jobs entirely by offering tax incentives to businessmen to start up steam laundries.

Illustration published in Harper’s Weekly, October 1881. With such a fancy affair on the horizon, city official couldn't have citizens walking around in dirty clothes. They threatened the strikers, floating the possibility of charging members of The Washing Society an annual license fee of $25. In addition, officials tried to eliminate their jobs entirely by offering tax incentives to businessmen to start up steam laundries. The license would be an enormous expense given the women were lucky to earn eight dollars a month, but they agreed it was worth it for a uniform rate of pay.

The women wrote the city mayor directly: "We the members of our society, are determined to stand to our pledge and make extra charges for washing...and are willing to pay $25 or $50 for licenses as a protection...and will do it before we will be defeated, and then we will have full control of the city’s washing at our own prices."

The letter ended with a promise. "We mean business this week or no washing."

Through united, grassroots organization, Atlanta washerwomen proved themselves a force to be reckoned with. They improved their situation and their income and the strike motivated other black domestic workers, cooks, house servants, nurses and hotel maids to likewise push for wage increases.

Do you want to topple the ladder? Unity and persistence may be the only weapon we have.

Published on February 28, 2025 11:09

August 19, 2024

When a Female Spy Breaks the Glass Ceiling, Does Anyone Hear It Shatter?

Don't be surprised if you haven't heard of Elizabeth Sudmeier, a spy craft pioneer who crashed through the glass ceiling of the American Central Intelligence Agency.

Her CIA case files remained classified until just ten years ago, which means we also did not know about the odds she faced, the battles she fought and the determination it took for a woman to succeed in one of the manliest professions in the world.

Like many women in the 1940s and 50s, Elizabeth began her career as a typist, but she went on to become the first woman American CIA secret agent.

During the Cold War, on assignment in the Middle East, Elizabeth procured volumes of details about Soviet Military hardware that turned out to be invaluable to US defense.

Women CIA agents were offered little respect in the 1950s, as I told you in this story First Active Duty CIA Officer to Die was a Woman. And They Lied About It . Still, Elizabeth Sudmeier performed her assignments with dedication and excellence becoming the first CIA woman to recruit and handle foreign assets.

One side note, an unnamed woman of the Sioux Nation no doubt contributed to Elisabeth's success, as her nanny, she practically raised the girl throughout her early years. Elizabeth Sudmeier prior to her service in the CIA. Picture an American woman melting into the scene outside a cafe in Baghdad, waiting for a clandestine meeting. She's spent the last six months persuading a particular man to work with her. The stakes are high for America and for the both of them. If they're caught, they will likely pay with their lives.

Elizabeth Sudmeier prior to her service in the CIA. Picture an American woman melting into the scene outside a cafe in Baghdad, waiting for a clandestine meeting. She's spent the last six months persuading a particular man to work with her. The stakes are high for America and for the both of them. If they're caught, they will likely pay with their lives.

The year is 1954 and the US and USSR maintain a tense standoff with arsenals of nuclear and conventional weapons. When the man shows up, it's only for a moment, long enough to hand this female spy an envelope. She has just stolen Soviet secrets.

Elizabeth holds blueprints for the Soviet MiG-19 jet fighter.

Over time, through this source, Elizabeth also gained details of the MiG-21 fighter, the SA2 missile, and dozens of volumes of technical manuals relating to Soviet military systems and equipment. This type of information proved extremely valuable to the US in understanding the capabilities of Soviet weapons.

Elizabeth set up seemingly accidental encounters with her source at coffee houses, cafes or a movie theater. As they met briefly, he handed off materials that she carried to a secure location for copying. Then Elizabeth returned the documents to the informant later that night.

When Elizabeth went to work in the Middle East, CIA officials didn't plan on female agents courting relationships with foreign assets and managing them. Named a "Reports Officer," she was expected to stay in her lane and do tamer work.

According to one CIA review in 1960 “there is a general feeling that the preparation of reports is a tedious and incidental chore, to be avoided like the plague by any promising and ambitious young man who wants to get ahead in operations.”

But she proved herself, and thus other women, could successfully run operations under the intense pressure in the world of counterintelligence. She also did so under the aggressive scrutiny of her male bosses.

After her work in Baghdad securing important Soviet secrets, Elizabeth's station chief nominated her for the Intelligence Medal of Merit, which prompted controversy over whether a female who was not listed as an operations officer could win distinction for an operational act. Colleagues argued on her behalf and eventually in 1962, Elizabeth received the medal. Elizabeth Sudmeier receiving her second medal of honor from the CIA. A CIA officer who knew Elizabeth in the 1950s recalled how she paved the way for women in the CIA: “She was a real pistol…. The fact that she accomplished so much is incredible given the general antagonism of NE officers to women functioning as ops officers."

Elizabeth Sudmeier receiving her second medal of honor from the CIA. A CIA officer who knew Elizabeth in the 1950s recalled how she paved the way for women in the CIA: “She was a real pistol…. The fact that she accomplished so much is incredible given the general antagonism of NE officers to women functioning as ops officers."

Despite of her accomplishments, superiors in the CIA did not promote Elizabeth, passing over her for eight years. An officer who knew her said, "I can tell you outright that hers was a monumental struggle as NE Division was dead set against the idea and concept of a female ops officer.” This was after she had accomplished the job!

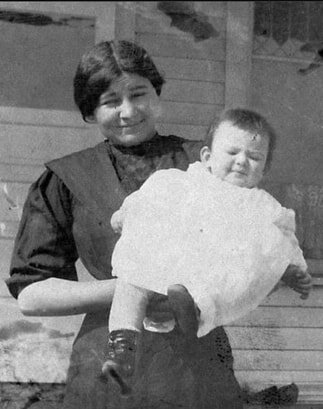

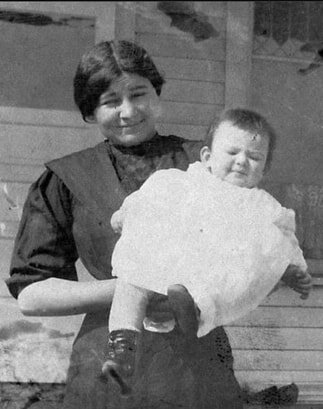

Elizabeth was born in 1912, in the small railroad town of Timber Lake, South Dakota, near the Sioux Nation. She was raised by a Sioux nanny for much of her childhood and became fluent in the Sioux language, which her father also spoke. Elizabeth in the arms of her Sioux nanny, 1912. After high school, Elizabeth studied English Literature at The College of St. Catherine in St. Paul, Minnesota, earning a B.A. in 1933.

Elizabeth in the arms of her Sioux nanny, 1912. After high school, Elizabeth studied English Literature at The College of St. Catherine in St. Paul, Minnesota, earning a B.A. in 1933.

She returned to South Dakota and taught high school English a few years, then got a secretarial job at St. Paul, MN bank. During World War II she joined the US Army Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, where she was assigned to recruiting. Elizabeth Sudmeier in a Women’s Army Corps recruiting advertisement, 1944. In March 1947, Elizabeth joined the CIA’s predecessor, the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), as a shorthand stenographer in the Office of Reports and Estimates. When the CIA replaced the CIG four months later, Elizabeth became one of the Agency’s charter members

Elizabeth Sudmeier in a Women’s Army Corps recruiting advertisement, 1944. In March 1947, Elizabeth joined the CIA’s predecessor, the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), as a shorthand stenographer in the Office of Reports and Estimates. When the CIA replaced the CIG four months later, Elizabeth became one of the Agency’s charter members

In October 1951 she transferred to the clandestine service, serving in the Middle East and South Asia for almost nine years. Elizabeth took mandatory retirement on May 12, 1972, at age sixty, dying 1989 at 76. Not even her family knew her covert duties and files relating to her work remained classified until February 2014.

However, in 2013, nearly 25 years after he death, Elizabeth received the CIA Trailblazer Award given to “CIA officers whose leadership, achievements, and dedication to mission had a significant impact on the agency’s history and legacy.”

Sources

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-women-who-helped-to-build-the-cia-11663992062

https://x.com/CIA/status/1113554329833758720

https://www.stkate.edu/newswire/news/elizabeth-sudmeier-cia-trailblazer

https://www.elespanol.com/social/20190408/verdadera-viuda-negra-cia-rescata-fundadora-olvidada/388711686_0.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20150905093741/https://www.cia.gov/news-information/featured-story-archive/2015-featured-story-archive/elizabeth-sudmeier-story.html

Her CIA case files remained classified until just ten years ago, which means we also did not know about the odds she faced, the battles she fought and the determination it took for a woman to succeed in one of the manliest professions in the world.

Like many women in the 1940s and 50s, Elizabeth began her career as a typist, but she went on to become the first woman American CIA secret agent.

During the Cold War, on assignment in the Middle East, Elizabeth procured volumes of details about Soviet Military hardware that turned out to be invaluable to US defense.

Women CIA agents were offered little respect in the 1950s, as I told you in this story First Active Duty CIA Officer to Die was a Woman. And They Lied About It . Still, Elizabeth Sudmeier performed her assignments with dedication and excellence becoming the first CIA woman to recruit and handle foreign assets.

One side note, an unnamed woman of the Sioux Nation no doubt contributed to Elisabeth's success, as her nanny, she practically raised the girl throughout her early years.

Elizabeth Sudmeier prior to her service in the CIA. Picture an American woman melting into the scene outside a cafe in Baghdad, waiting for a clandestine meeting. She's spent the last six months persuading a particular man to work with her. The stakes are high for America and for the both of them. If they're caught, they will likely pay with their lives.

Elizabeth Sudmeier prior to her service in the CIA. Picture an American woman melting into the scene outside a cafe in Baghdad, waiting for a clandestine meeting. She's spent the last six months persuading a particular man to work with her. The stakes are high for America and for the both of them. If they're caught, they will likely pay with their lives.The year is 1954 and the US and USSR maintain a tense standoff with arsenals of nuclear and conventional weapons. When the man shows up, it's only for a moment, long enough to hand this female spy an envelope. She has just stolen Soviet secrets.

Elizabeth holds blueprints for the Soviet MiG-19 jet fighter.

Over time, through this source, Elizabeth also gained details of the MiG-21 fighter, the SA2 missile, and dozens of volumes of technical manuals relating to Soviet military systems and equipment. This type of information proved extremely valuable to the US in understanding the capabilities of Soviet weapons.

Elizabeth set up seemingly accidental encounters with her source at coffee houses, cafes or a movie theater. As they met briefly, he handed off materials that she carried to a secure location for copying. Then Elizabeth returned the documents to the informant later that night.

When Elizabeth went to work in the Middle East, CIA officials didn't plan on female agents courting relationships with foreign assets and managing them. Named a "Reports Officer," she was expected to stay in her lane and do tamer work.

According to one CIA review in 1960 “there is a general feeling that the preparation of reports is a tedious and incidental chore, to be avoided like the plague by any promising and ambitious young man who wants to get ahead in operations.”

But she proved herself, and thus other women, could successfully run operations under the intense pressure in the world of counterintelligence. She also did so under the aggressive scrutiny of her male bosses.

After her work in Baghdad securing important Soviet secrets, Elizabeth's station chief nominated her for the Intelligence Medal of Merit, which prompted controversy over whether a female who was not listed as an operations officer could win distinction for an operational act. Colleagues argued on her behalf and eventually in 1962, Elizabeth received the medal.

Elizabeth Sudmeier receiving her second medal of honor from the CIA. A CIA officer who knew Elizabeth in the 1950s recalled how she paved the way for women in the CIA: “She was a real pistol…. The fact that she accomplished so much is incredible given the general antagonism of NE officers to women functioning as ops officers."

Elizabeth Sudmeier receiving her second medal of honor from the CIA. A CIA officer who knew Elizabeth in the 1950s recalled how she paved the way for women in the CIA: “She was a real pistol…. The fact that she accomplished so much is incredible given the general antagonism of NE officers to women functioning as ops officers."Despite of her accomplishments, superiors in the CIA did not promote Elizabeth, passing over her for eight years. An officer who knew her said, "I can tell you outright that hers was a monumental struggle as NE Division was dead set against the idea and concept of a female ops officer.” This was after she had accomplished the job!

Elizabeth was born in 1912, in the small railroad town of Timber Lake, South Dakota, near the Sioux Nation. She was raised by a Sioux nanny for much of her childhood and became fluent in the Sioux language, which her father also spoke.

Elizabeth in the arms of her Sioux nanny, 1912. After high school, Elizabeth studied English Literature at The College of St. Catherine in St. Paul, Minnesota, earning a B.A. in 1933.

Elizabeth in the arms of her Sioux nanny, 1912. After high school, Elizabeth studied English Literature at The College of St. Catherine in St. Paul, Minnesota, earning a B.A. in 1933.She returned to South Dakota and taught high school English a few years, then got a secretarial job at St. Paul, MN bank. During World War II she joined the US Army Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, where she was assigned to recruiting.

Elizabeth Sudmeier in a Women’s Army Corps recruiting advertisement, 1944. In March 1947, Elizabeth joined the CIA’s predecessor, the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), as a shorthand stenographer in the Office of Reports and Estimates. When the CIA replaced the CIG four months later, Elizabeth became one of the Agency’s charter members

Elizabeth Sudmeier in a Women’s Army Corps recruiting advertisement, 1944. In March 1947, Elizabeth joined the CIA’s predecessor, the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), as a shorthand stenographer in the Office of Reports and Estimates. When the CIA replaced the CIG four months later, Elizabeth became one of the Agency’s charter members In October 1951 she transferred to the clandestine service, serving in the Middle East and South Asia for almost nine years. Elizabeth took mandatory retirement on May 12, 1972, at age sixty, dying 1989 at 76. Not even her family knew her covert duties and files relating to her work remained classified until February 2014.

However, in 2013, nearly 25 years after he death, Elizabeth received the CIA Trailblazer Award given to “CIA officers whose leadership, achievements, and dedication to mission had a significant impact on the agency’s history and legacy.”

Sources

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-women-who-helped-to-build-the-cia-11663992062

https://x.com/CIA/status/1113554329833758720

https://www.stkate.edu/newswire/news/elizabeth-sudmeier-cia-trailblazer

https://www.elespanol.com/social/20190408/verdadera-viuda-negra-cia-rescata-fundadora-olvidada/388711686_0.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20150905093741/https://www.cia.gov/news-information/featured-story-archive/2015-featured-story-archive/elizabeth-sudmeier-story.html

Published on August 19, 2024 13:20

August 3, 2024

Women Who Boycotted Hitler’s Olympics & what we've inherited from 1936

I love the Olympic Games! This year I've only been able to watch a curated selection of events, and the stories of the athletes are amazing as always, their challenges, the competition, the excellence in sport and, of course, the medals. So much to inspire us!

This summer in Paris, as has been true in other host cities in the past, there's a dark side to the sparkling events.

French authorities cleared out homeless encampments for months prior to the opening ceremonies, busing "undesirable people" out of the city center to the fringes of Paris. Authorities have been sharply criticized as thousands of migrants, squatters, sex workers and families down on their luck have ended up with no shelter.

A spokesman for the regional government denied the accusations pre-games "social cleansing" and said the government has relocated migrants from the city for years.

“We are taking care of them. We don’t really understand the criticism because we are very much determined to offer places for these people."

Hear the stories and see photos from Associated Press here .

Or here from ABC News. (5-minute read)

Our modern games owe their grand themes, magnificent Olympic stadiums and even cost-overruns to the precedent set by Adolf Hitler's in 1936. The Berlin games were the first ever broadcast on television, and the first to feature the Olympic torch relay from Greece to the site of the games.

Nazis planned the torch-lighting and other pageantry in an all-out effort to host an Olympics that would out-shine all previous games. Hitler's grandiose plans for Germany world domination included taking over the Olympics forever.

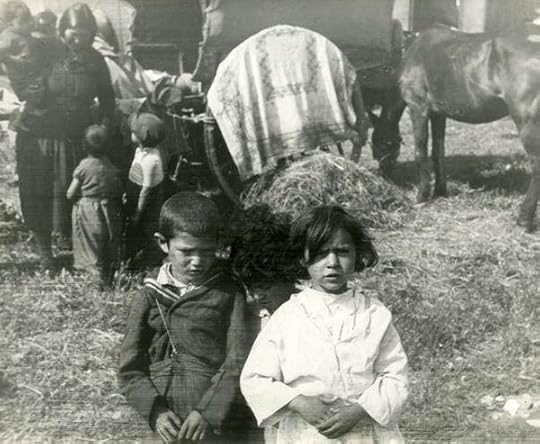

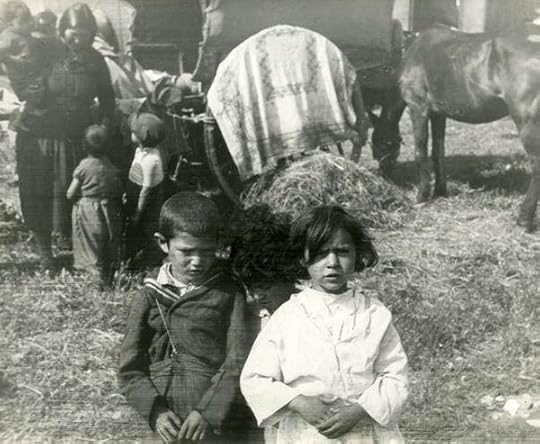

In his desire to show the world the superiority of the Aryan race, he "cleaned-up" Berlin. Police arrested nearly one-thousand Roma and Sinti people, interning them in a camp on the edge of the city near Berlin's sewage fields. The Gypsies were later deported to Auschwitz.

Police arrested nearly one-thousand Roma and Sinti people, interning them in a camp on the edge of the city near Berlin's sewage fields. The Gypsies were later deported to Auschwitz.

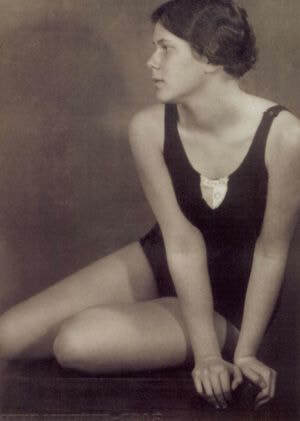

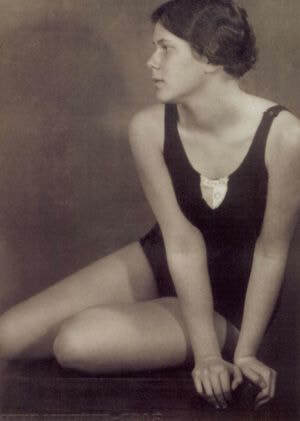

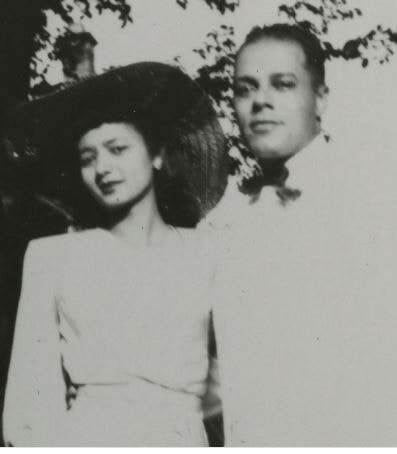

Few stood up to Nazi propaganda portraying Germany as a tolerant and hospitable nation. The only country to boycott the 1936 games was the Soviet Union. But three young Jewish girls gave up their dreams to follow their consciences. Austrian champion swimmers Judith Deutsch, Ruth Langer and Lucie Goldner, 1936. Judith Deutsch, (left in photo) Austria's top swimmer in the mid-1930s, knew of the persecution of Jews in Germany and she experienced antisemitism in her home country.

Austrian champion swimmers Judith Deutsch, Ruth Langer and Lucie Goldner, 1936. Judith Deutsch, (left in photo) Austria's top swimmer in the mid-1930s, knew of the persecution of Jews in Germany and she experienced antisemitism in her home country.

She and two other Austrian swimmers, Ruth Langer (middle in photo) and Lucie Goldner (right) trained at the Jewish swim club Hakoah in Vienna, Austria because they were barred from public pools, where signs read No entry for dogs and Jews.

Ruth Lager grew up in Vienna and took up swimming at age 11, hoping to excel at something her brother did not. At age 14, she broke the Austrian records for the 100-meter and 400-meter freestyles and won the Austrian championships at those distances.

Judith dominated Austrian swimming 1934-36. She was national champion in the 100-meter freestyle, 200-meter freestyle, and 400-meter freestyle, setting twelve national records in one year. In 1935, she won the country's highest athletic award Outstanding Austrian Athlete.

The three swimmers were selected for the Austrian Olympic Team, due to compete in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Nazi Germany. The games sparked international debate about whether attending the Olympics endorsed Germany's white nationalistic policies and militaristic ambitions.

As the Berlin Olympics approached in 1936, Americans, too, debated whether to attend. The US Olympic Committee President, Avery Bundage traveled to Germany to investigate claims of Nazi discrimination against Jews.

He reported such claims were exaggerated “and the unhindered continuance of the Olympic movement were more important than the German-Jewish situation.”

Lord Melchett of Britain, president of the World Federation of Jewish Sports Clubs recommended Jewish athletes not participate. Not an obvious choice at the time, only a few athletes, Jewish or not, joined the boycott.

Judith, Lucie and Ruth took a stand, saying, ''We do not boycott Olympia, but Berlin."

In an interview with Reuters, Ruth said, "It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. But being Jewish, it was unthinkable to compete in the Games in Nazi Germany, where my people were being persecuted.

Ruth Langer originally held eight Austrian national swimming records. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) Austrian authorities swiftly retaliated, banning the three swimmers from all national and international competition ''due to severe damage of Austrian sports'' and ''gross disrespect for the Olympic spirit.'' In addition, officials erased them from the Austrian record books.

Ruth Langer originally held eight Austrian national swimming records. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) Austrian authorities swiftly retaliated, banning the three swimmers from all national and international competition ''due to severe damage of Austrian sports'' and ''gross disrespect for the Olympic spirit.'' In addition, officials erased them from the Austrian record books.

Two years later, Germany annexed Austria and singled out Austrian Jews for even worse discrimination. Viennese athletes forced Ruth to clean the SS and SA barracks.

Still a teenager, Ruth decided to enter a swim meet in Italy. Dying her brown hair blonde, she carried a forged baptismal certificate as proof she was Roman Catholic.

The next year she escaped from Italy to England where, in 1939, she won the British long-distance swimming championship in the Thames.

The other two women also escaped the Holocaust. Lucie Goldner, the Austrian backstroke champion, used her swimming connections to flee to London. After WWII, she eventually moved to Australia, where she continued swimming for another Jewish swim club.

Judith emigrated to Palestine and became the Israeli national champion. She represented Hebrew University at the 1939 World University Games, winning a silver medal. Judith Deutsch Haspel, Israeli national champion swimmer. In 1995, when the Austrian government apologized and reinstated the champions’ records, all three women declined to travel to the ceremony.

Judith Deutsch Haspel, Israeli national champion swimmer. In 1995, when the Austrian government apologized and reinstated the champions’ records, all three women declined to travel to the ceremony.

Judith wrote: "I am happy to accept your apologies and the withdrawal of sanctions against me...And in no way do I regret having done what I did sixty years ago."

Decades later, before the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, Ruth told Reuters: ''Whenever the Games come up again, I get a heartache. It's something that stays with you for the rest of your life.'' Sources

https://www.ushmm.org/exhibition/olympics/?content=jewish_athletes_more

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1140536

https://apnews.com/article/olympics-2024-paris-migrant-camp-3ef2a08d8da1085148ed409dcb44d6f6

https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/wireStory/migrants-homeless-people-cleared-paris-olympics-112279127

https://www.nytimes.com/1999/06/06/sports/ruth-langer-lawrence-77-who-boycotted-36-olympics.html

https://lilith.org/articles/swimmers-against-the-tide/

https://www.ushmm.org/exhibition/olympics/?content=jewish_athletes_more

https://www.ushmm.org/exhibition/olympics/?content=aftermath&lang=en

This summer in Paris, as has been true in other host cities in the past, there's a dark side to the sparkling events.

French authorities cleared out homeless encampments for months prior to the opening ceremonies, busing "undesirable people" out of the city center to the fringes of Paris. Authorities have been sharply criticized as thousands of migrants, squatters, sex workers and families down on their luck have ended up with no shelter.

A spokesman for the regional government denied the accusations pre-games "social cleansing" and said the government has relocated migrants from the city for years.

“We are taking care of them. We don’t really understand the criticism because we are very much determined to offer places for these people."

Hear the stories and see photos from Associated Press here .

Or here from ABC News. (5-minute read)

Our modern games owe their grand themes, magnificent Olympic stadiums and even cost-overruns to the precedent set by Adolf Hitler's in 1936. The Berlin games were the first ever broadcast on television, and the first to feature the Olympic torch relay from Greece to the site of the games.

Nazis planned the torch-lighting and other pageantry in an all-out effort to host an Olympics that would out-shine all previous games. Hitler's grandiose plans for Germany world domination included taking over the Olympics forever.

In his desire to show the world the superiority of the Aryan race, he "cleaned-up" Berlin.

Police arrested nearly one-thousand Roma and Sinti people, interning them in a camp on the edge of the city near Berlin's sewage fields. The Gypsies were later deported to Auschwitz.

Police arrested nearly one-thousand Roma and Sinti people, interning them in a camp on the edge of the city near Berlin's sewage fields. The Gypsies were later deported to Auschwitz. Few stood up to Nazi propaganda portraying Germany as a tolerant and hospitable nation. The only country to boycott the 1936 games was the Soviet Union. But three young Jewish girls gave up their dreams to follow their consciences.

Austrian champion swimmers Judith Deutsch, Ruth Langer and Lucie Goldner, 1936. Judith Deutsch, (left in photo) Austria's top swimmer in the mid-1930s, knew of the persecution of Jews in Germany and she experienced antisemitism in her home country.

Austrian champion swimmers Judith Deutsch, Ruth Langer and Lucie Goldner, 1936. Judith Deutsch, (left in photo) Austria's top swimmer in the mid-1930s, knew of the persecution of Jews in Germany and she experienced antisemitism in her home country.She and two other Austrian swimmers, Ruth Langer (middle in photo) and Lucie Goldner (right) trained at the Jewish swim club Hakoah in Vienna, Austria because they were barred from public pools, where signs read No entry for dogs and Jews.

Ruth Lager grew up in Vienna and took up swimming at age 11, hoping to excel at something her brother did not. At age 14, she broke the Austrian records for the 100-meter and 400-meter freestyles and won the Austrian championships at those distances.

Judith dominated Austrian swimming 1934-36. She was national champion in the 100-meter freestyle, 200-meter freestyle, and 400-meter freestyle, setting twelve national records in one year. In 1935, she won the country's highest athletic award Outstanding Austrian Athlete.

The three swimmers were selected for the Austrian Olympic Team, due to compete in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Nazi Germany. The games sparked international debate about whether attending the Olympics endorsed Germany's white nationalistic policies and militaristic ambitions.

As the Berlin Olympics approached in 1936, Americans, too, debated whether to attend. The US Olympic Committee President, Avery Bundage traveled to Germany to investigate claims of Nazi discrimination against Jews.

He reported such claims were exaggerated “and the unhindered continuance of the Olympic movement were more important than the German-Jewish situation.”

Lord Melchett of Britain, president of the World Federation of Jewish Sports Clubs recommended Jewish athletes not participate. Not an obvious choice at the time, only a few athletes, Jewish or not, joined the boycott.

Judith, Lucie and Ruth took a stand, saying, ''We do not boycott Olympia, but Berlin."

In an interview with Reuters, Ruth said, "It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. But being Jewish, it was unthinkable to compete in the Games in Nazi Germany, where my people were being persecuted.

Ruth Langer originally held eight Austrian national swimming records. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) Austrian authorities swiftly retaliated, banning the three swimmers from all national and international competition ''due to severe damage of Austrian sports'' and ''gross disrespect for the Olympic spirit.'' In addition, officials erased them from the Austrian record books.

Ruth Langer originally held eight Austrian national swimming records. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) Austrian authorities swiftly retaliated, banning the three swimmers from all national and international competition ''due to severe damage of Austrian sports'' and ''gross disrespect for the Olympic spirit.'' In addition, officials erased them from the Austrian record books.Two years later, Germany annexed Austria and singled out Austrian Jews for even worse discrimination. Viennese athletes forced Ruth to clean the SS and SA barracks.

Still a teenager, Ruth decided to enter a swim meet in Italy. Dying her brown hair blonde, she carried a forged baptismal certificate as proof she was Roman Catholic.

The next year she escaped from Italy to England where, in 1939, she won the British long-distance swimming championship in the Thames.

The other two women also escaped the Holocaust. Lucie Goldner, the Austrian backstroke champion, used her swimming connections to flee to London. After WWII, she eventually moved to Australia, where she continued swimming for another Jewish swim club.

Judith emigrated to Palestine and became the Israeli national champion. She represented Hebrew University at the 1939 World University Games, winning a silver medal.

Judith Deutsch Haspel, Israeli national champion swimmer. In 1995, when the Austrian government apologized and reinstated the champions’ records, all three women declined to travel to the ceremony.

Judith Deutsch Haspel, Israeli national champion swimmer. In 1995, when the Austrian government apologized and reinstated the champions’ records, all three women declined to travel to the ceremony.Judith wrote: "I am happy to accept your apologies and the withdrawal of sanctions against me...And in no way do I regret having done what I did sixty years ago."

Decades later, before the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, Ruth told Reuters: ''Whenever the Games come up again, I get a heartache. It's something that stays with you for the rest of your life.'' Sources

https://www.ushmm.org/exhibition/olympics/?content=jewish_athletes_more

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1140536

https://apnews.com/article/olympics-2024-paris-migrant-camp-3ef2a08d8da1085148ed409dcb44d6f6

https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/wireStory/migrants-homeless-people-cleared-paris-olympics-112279127

https://www.nytimes.com/1999/06/06/sports/ruth-langer-lawrence-77-who-boycotted-36-olympics.html

https://lilith.org/articles/swimmers-against-the-tide/

https://www.ushmm.org/exhibition/olympics/?content=jewish_athletes_more

https://www.ushmm.org/exhibition/olympics/?content=aftermath&lang=en

Published on August 03, 2024 15:50

September 23, 2023

Bomb Attack on Woman Environmentalist remains Unsolved after 30 years

Judi Bari made national headlines 30 years ago with her passionate protests against the clearcutting of California's old growth redwoods.

She helped organize Redwood Summer, a three-month-long, non-violent protest against logging in Humboldt County. Then just weeks before the kick-off event, a homemade bomb exploded under the driver's seat of Judi's car. Judi Bari organized nonviolent protests against destructive corporate logging of the redwood forests. Photo courtesy of Greg King Local Oakland, CA, police officers tracked her to the hospital where they arrested the seriously injured woman, labeled her a terrorist and arrested her on arrested on suspicion of transporting illegal explosives. They accused Judi of planting the bomb that nearly killed her.

Judi Bari organized nonviolent protests against destructive corporate logging of the redwood forests. Photo courtesy of Greg King Local Oakland, CA, police officers tracked her to the hospital where they arrested the seriously injured woman, labeled her a terrorist and arrested her on arrested on suspicion of transporting illegal explosives. They accused Judi of planting the bomb that nearly killed her.

Two months later, they dropped the charges due to lack of evidence. But why has no one ever been charged in the crime? The Vietnam War launched Judi Bari's life's work as an activist but her job as a carpenter sparked her "environmental epiphany."

As a student at the University of Maryland, Judi joined protests against the Vietnam War. She moved on to work as a labor organizer in Washington, D.C, leading postal workers to victory in a wildcat strike against the U.S. Postal Service. After her efforts to unionize grocery clerks fizzled, Judi moved to Northern California and took a carpenter job.

While siding a house one day, she marveled at a board she handled. The long piece of wood didn't have a single knot and she wondered aloud if it was old-growth redwood. Her supervisor confirmed the piece of siding had been cut from a redwood 1,000 years old.

''A light bulb went on: We are cutting down old-growth forests to make yuppie houses,'' Judi later told an interviewer. ''I became obsessed with the forests.'' Judi Bari (right), environmentalist, feminist, labor organizer, and musician gearing up for Redwood Summer with colleague Darryl Cherney (center) Darlene (right), 1990. Photo courtesy Evan Johnson. Judi imagined Redwood Summer arousing the civil rights spirit that had characterized protests throughout the South in the summer of 1964 and encouraged student from all over the state to join the protests.

Judi Bari (right), environmentalist, feminist, labor organizer, and musician gearing up for Redwood Summer with colleague Darryl Cherney (center) Darlene (right), 1990. Photo courtesy Evan Johnson. Judi imagined Redwood Summer arousing the civil rights spirit that had characterized protests throughout the South in the summer of 1964 and encouraged student from all over the state to join the protests.

As summer approached, Judi had made little progress convincing lumber workers to help protect the forests and tensions in the community escalated. Judi and other organizers received death threats and a logging truck rammed her car.

On May 24, 1990, she and Darryl Cherney took a concert and speaking tour to recruit college students. They were driving through Oakland when a motion-triggered pipe bomb wrapped with nails exploded directly under Judi's driver's seat.

Judi would be maimed and permanently disabled by her injuries; Darryl suffered minor injuries. The two told paramedics and responding police officers they believed they had been targeted because of their activism against the timber industry. They had copies of the written death threats they're received with them in the car.

Judi Bari Web Photo Gallery. Judi's bombed car in Oakland Police Department storage, 1990. OPD photo Oakland police, OPD, tracked Judi and Darryl to the hospital, arresting them as primary suspects in the case. Working with the FBI, they pursued a case of terrorism, insisting they had evidence the two activists had been transporting the bomb with evil intent when it accidentally detonated. Originally, the announced to the press that the bomb was in the back seat of the car when it exploded.

Judi Bari Web Photo Gallery. Judi's bombed car in Oakland Police Department storage, 1990. OPD photo Oakland police, OPD, tracked Judi and Darryl to the hospital, arresting them as primary suspects in the case. Working with the FBI, they pursued a case of terrorism, insisting they had evidence the two activists had been transporting the bomb with evil intent when it accidentally detonated. Originally, the announced to the press that the bomb was in the back seat of the car when it exploded.

Arraignment in the case was delayed seven weeks until the District Attorney said he would not file charges due to lack of evidence. The Oakland Police closed the case, but the FBI continued investigating, telling the media Judi and Darryl were their only suspects.

When law enforcement reported no progress in the case a year after the car bombing, Judi and Darryl filed a federal civil rights suit against the FBI and OPD claiming law officers were trying to frame them as terrorists to discredit their political organizing to protect the redwood forests.

The case dragged on for years, but in 2002, a federal jury concluded the pair's civil rights had been violated by the FBI and Oakland Police Department. The two were awarded $4.4 million. Unfortunately, Bari had died of breast cancer in 1997. Her share went to her two teenage daughters.

The jury found that three FBI agents and Three OPD officers had violated the plaintiffs' First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, and for the defendants' various unlawful acts, including unlawful search and seizure in violation of the plaintiffs' Fourth Amendment rights.

After the trial's gag order was lifted, a juror told the media that she believed the law enforcement agents had lied.

"Investigators were lying so much it was insulting.... I'm surprised that they seriously expected anyone would believe them ... They were evasive. They were arrogant. They were defensive," said juror Mary Nunn.

As of 2015, North Coast Journal reported it appears no official effort has been made to determine who put that bomb in Bari’s car in 1990.

The timber wars of the 1990 scored some victories for the environment that could serve as models and inspiration for climate warriors today.

Anti-logging protesters hold up a sign as they stand on lumber inside the Pacific Lumber facility in Carlotta, Calif., Tuesday morning, Oct. 1, 1996 (AP/Paul Sakuma) Judi Bari's organized, mass protests served as one prong in a concerted effort to disrupt corporate greed and preserve and protect irreplaceable resources.

Anti-logging protesters hold up a sign as they stand on lumber inside the Pacific Lumber facility in Carlotta, Calif., Tuesday morning, Oct. 1, 1996 (AP/Paul Sakuma) Judi Bari's organized, mass protests served as one prong in a concerted effort to disrupt corporate greed and preserve and protect irreplaceable resources.

Environmental activists camped out in trees to prevent logging, sometimes for months or years. Other filed lawsuits challenging the government and timber companies’ supposed right to destroy old-growth forests. Others gathered the support and evidence of scientists, regulators and politicians to the cause. Rallies and protests drew media attention across the country increasing support for old-growth forests.

The final deal was not close to perfect," says Darren Speece, author of "Defending Giants: The Redwood Wars and the Transformation of American Environmental Politics." "It didn’t save enough of the giant redwoods, nor did it provide enough protection for the broader redwood forests but direct actions in the woods delayed specific logging threats in the most vulnerable places, where the trees are more than 1,000 years old and grow to upwards of 300 feet tall. During the delays, the courts officially halted logging in those endangered forests."

Speece says the bold and persistent, near-daily activism for more than 20 years demonstrated that small groups of people can alter the direction of a hostile system.

Judi Bari was recognized for her dedication to the protection and stewardship of California's ancient redwood forests by the City of Oakland in 2003 when the city council voted unanimously to establish May 24th as Judi Bari Day.

Sources

https://treesfoundation.org/2020/05/30-years-ago-in-may-the-bombing-of-earth-first-activists-judi-bari-and-darryl-cherney/

http://www.judibari.org/

https://www.salon.com/2017/02/11/a-field-guide-to-protesting-in-the-trump-era-lessons-from-the-redwoods-protectors/

https://www.northcoastjournal.com/NewsBlog/archives/2015/05/19/who-bombed-judi-bari-25-years-later-we-may-find-an-answer

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/cops-fbi-lied-about-probe-juror-says-woman-2801054.php

https://www.nytimes.com/1997/03/04/us/judi-bari-47-leader-of-earth-first-protest-on-redwoods-in-1990.html

She helped organize Redwood Summer, a three-month-long, non-violent protest against logging in Humboldt County. Then just weeks before the kick-off event, a homemade bomb exploded under the driver's seat of Judi's car.

Judi Bari organized nonviolent protests against destructive corporate logging of the redwood forests. Photo courtesy of Greg King Local Oakland, CA, police officers tracked her to the hospital where they arrested the seriously injured woman, labeled her a terrorist and arrested her on arrested on suspicion of transporting illegal explosives. They accused Judi of planting the bomb that nearly killed her.

Judi Bari organized nonviolent protests against destructive corporate logging of the redwood forests. Photo courtesy of Greg King Local Oakland, CA, police officers tracked her to the hospital where they arrested the seriously injured woman, labeled her a terrorist and arrested her on arrested on suspicion of transporting illegal explosives. They accused Judi of planting the bomb that nearly killed her.Two months later, they dropped the charges due to lack of evidence. But why has no one ever been charged in the crime? The Vietnam War launched Judi Bari's life's work as an activist but her job as a carpenter sparked her "environmental epiphany."

As a student at the University of Maryland, Judi joined protests against the Vietnam War. She moved on to work as a labor organizer in Washington, D.C, leading postal workers to victory in a wildcat strike against the U.S. Postal Service. After her efforts to unionize grocery clerks fizzled, Judi moved to Northern California and took a carpenter job.

While siding a house one day, she marveled at a board she handled. The long piece of wood didn't have a single knot and she wondered aloud if it was old-growth redwood. Her supervisor confirmed the piece of siding had been cut from a redwood 1,000 years old.

''A light bulb went on: We are cutting down old-growth forests to make yuppie houses,'' Judi later told an interviewer. ''I became obsessed with the forests.''

Judi Bari (right), environmentalist, feminist, labor organizer, and musician gearing up for Redwood Summer with colleague Darryl Cherney (center) Darlene (right), 1990. Photo courtesy Evan Johnson. Judi imagined Redwood Summer arousing the civil rights spirit that had characterized protests throughout the South in the summer of 1964 and encouraged student from all over the state to join the protests.

Judi Bari (right), environmentalist, feminist, labor organizer, and musician gearing up for Redwood Summer with colleague Darryl Cherney (center) Darlene (right), 1990. Photo courtesy Evan Johnson. Judi imagined Redwood Summer arousing the civil rights spirit that had characterized protests throughout the South in the summer of 1964 and encouraged student from all over the state to join the protests.As summer approached, Judi had made little progress convincing lumber workers to help protect the forests and tensions in the community escalated. Judi and other organizers received death threats and a logging truck rammed her car.

On May 24, 1990, she and Darryl Cherney took a concert and speaking tour to recruit college students. They were driving through Oakland when a motion-triggered pipe bomb wrapped with nails exploded directly under Judi's driver's seat.

Judi would be maimed and permanently disabled by her injuries; Darryl suffered minor injuries. The two told paramedics and responding police officers they believed they had been targeted because of their activism against the timber industry. They had copies of the written death threats they're received with them in the car.

Judi Bari Web Photo Gallery. Judi's bombed car in Oakland Police Department storage, 1990. OPD photo Oakland police, OPD, tracked Judi and Darryl to the hospital, arresting them as primary suspects in the case. Working with the FBI, they pursued a case of terrorism, insisting they had evidence the two activists had been transporting the bomb with evil intent when it accidentally detonated. Originally, the announced to the press that the bomb was in the back seat of the car when it exploded.

Judi Bari Web Photo Gallery. Judi's bombed car in Oakland Police Department storage, 1990. OPD photo Oakland police, OPD, tracked Judi and Darryl to the hospital, arresting them as primary suspects in the case. Working with the FBI, they pursued a case of terrorism, insisting they had evidence the two activists had been transporting the bomb with evil intent when it accidentally detonated. Originally, the announced to the press that the bomb was in the back seat of the car when it exploded.Arraignment in the case was delayed seven weeks until the District Attorney said he would not file charges due to lack of evidence. The Oakland Police closed the case, but the FBI continued investigating, telling the media Judi and Darryl were their only suspects.

When law enforcement reported no progress in the case a year after the car bombing, Judi and Darryl filed a federal civil rights suit against the FBI and OPD claiming law officers were trying to frame them as terrorists to discredit their political organizing to protect the redwood forests.

The case dragged on for years, but in 2002, a federal jury concluded the pair's civil rights had been violated by the FBI and Oakland Police Department. The two were awarded $4.4 million. Unfortunately, Bari had died of breast cancer in 1997. Her share went to her two teenage daughters.

The jury found that three FBI agents and Three OPD officers had violated the plaintiffs' First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, and for the defendants' various unlawful acts, including unlawful search and seizure in violation of the plaintiffs' Fourth Amendment rights.

After the trial's gag order was lifted, a juror told the media that she believed the law enforcement agents had lied.

"Investigators were lying so much it was insulting.... I'm surprised that they seriously expected anyone would believe them ... They were evasive. They were arrogant. They were defensive," said juror Mary Nunn.

As of 2015, North Coast Journal reported it appears no official effort has been made to determine who put that bomb in Bari’s car in 1990.

The timber wars of the 1990 scored some victories for the environment that could serve as models and inspiration for climate warriors today.

Anti-logging protesters hold up a sign as they stand on lumber inside the Pacific Lumber facility in Carlotta, Calif., Tuesday morning, Oct. 1, 1996 (AP/Paul Sakuma) Judi Bari's organized, mass protests served as one prong in a concerted effort to disrupt corporate greed and preserve and protect irreplaceable resources.

Anti-logging protesters hold up a sign as they stand on lumber inside the Pacific Lumber facility in Carlotta, Calif., Tuesday morning, Oct. 1, 1996 (AP/Paul Sakuma) Judi Bari's organized, mass protests served as one prong in a concerted effort to disrupt corporate greed and preserve and protect irreplaceable resources.Environmental activists camped out in trees to prevent logging, sometimes for months or years. Other filed lawsuits challenging the government and timber companies’ supposed right to destroy old-growth forests. Others gathered the support and evidence of scientists, regulators and politicians to the cause. Rallies and protests drew media attention across the country increasing support for old-growth forests.

The final deal was not close to perfect," says Darren Speece, author of "Defending Giants: The Redwood Wars and the Transformation of American Environmental Politics." "It didn’t save enough of the giant redwoods, nor did it provide enough protection for the broader redwood forests but direct actions in the woods delayed specific logging threats in the most vulnerable places, where the trees are more than 1,000 years old and grow to upwards of 300 feet tall. During the delays, the courts officially halted logging in those endangered forests."

Speece says the bold and persistent, near-daily activism for more than 20 years demonstrated that small groups of people can alter the direction of a hostile system.

Judi Bari was recognized for her dedication to the protection and stewardship of California's ancient redwood forests by the City of Oakland in 2003 when the city council voted unanimously to establish May 24th as Judi Bari Day.

Sources

https://treesfoundation.org/2020/05/30-years-ago-in-may-the-bombing-of-earth-first-activists-judi-bari-and-darryl-cherney/

http://www.judibari.org/

https://www.salon.com/2017/02/11/a-field-guide-to-protesting-in-the-trump-era-lessons-from-the-redwoods-protectors/

https://www.northcoastjournal.com/NewsBlog/archives/2015/05/19/who-bombed-judi-bari-25-years-later-we-may-find-an-answer

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/cops-fbi-lied-about-probe-juror-says-woman-2801054.php

https://www.nytimes.com/1997/03/04/us/judi-bari-47-leader-of-earth-first-protest-on-redwoods-in-1990.html

Published on September 23, 2023 11:37

August 1, 2023

Don't Call Us Donut Dollies!

I was thrilled to take part in a wonderful event!

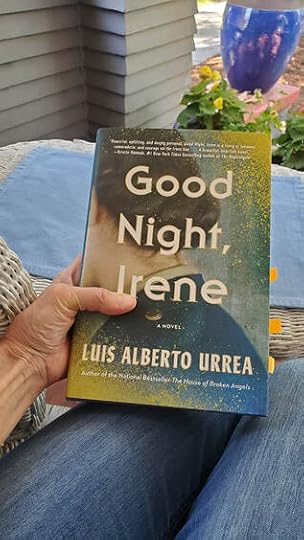

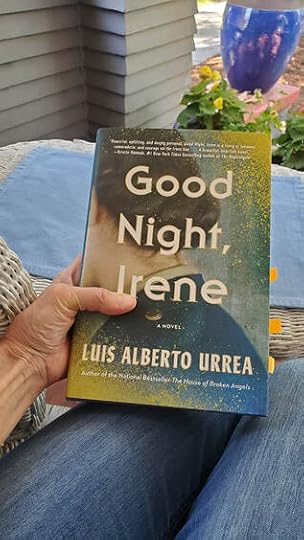

Pulitzer Prize finalist Luis Alberto Uurea came through Spokane, WA, on tour publicizing his newest book Good Night, Irene.

Very soon after starting to read this novel, I wished that I had written it, or rather, written a nonfiction book about the Donut Dollies of World War II. These women served coffee, donuts and a slice of home to soldiers on the front lines of battle. I could not have written this book because Luis Alberto Uurea based it on the true-life experiences of his mother, Phyllis Irene McLaughlin, who traveled across Europe with Patton's army. It's a great adventure story of women's strength, friendship and sacrifice.

I could not have written this book because Luis Alberto Uurea based it on the true-life experiences of his mother, Phyllis Irene McLaughlin, who traveled across Europe with Patton's army. It's a great adventure story of women's strength, friendship and sacrifice.

The fictional account follows closely the actual service route traveled by Phyllis and her partners Jill Pitts and Helen Anderson in the clubmobile Cheyanne. They saw Utah Beach, shortly after D-Day, skirmishes across France, where right in the middle of the Battle of Bastogne and the horrors of the Buchenwald death camp.

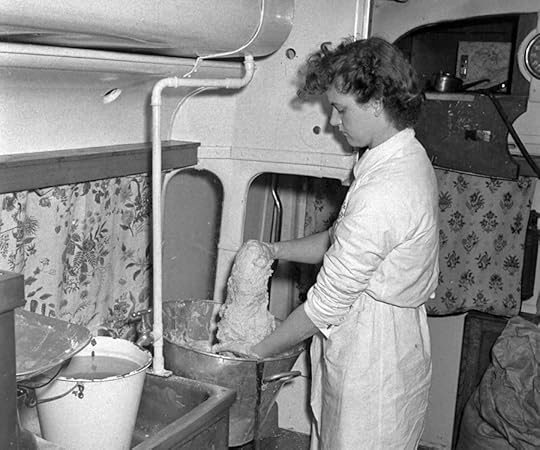

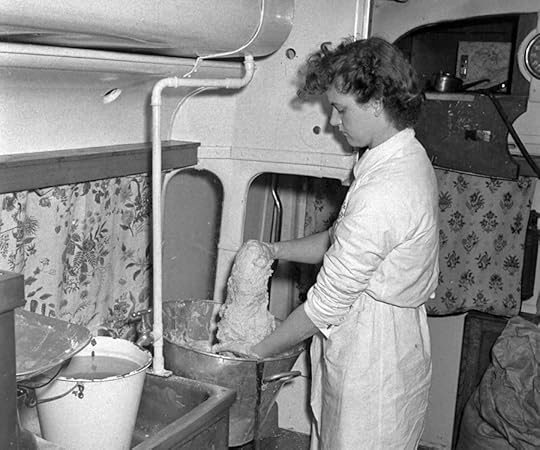

After reading the book, I had the honor of interviewing the author on stage for The Spokesman-Review’s Northwest Passages book club last week at the Bing Crosby Theater in downtown Spokane. Read more about that night here...  Luis Alberto Urrea answers a question from me at The Spokesman-Review’s Northwest Passages book club event July 6, 2023 at the Bing Crosby Theater in downtown Spokane, WA. The first Red Cross Clubmobile arrived in France just days after the D-Day invasion, and that summer, 80 of the modified two-and-a-half-ton GMC trucks trundled across the countryside serving the troops, not just refreshments, but music, laughter and dancing.

Luis Alberto Urrea answers a question from me at The Spokesman-Review’s Northwest Passages book club event July 6, 2023 at the Bing Crosby Theater in downtown Spokane, WA. The first Red Cross Clubmobile arrived in France just days after the D-Day invasion, and that summer, 80 of the modified two-and-a-half-ton GMC trucks trundled across the countryside serving the troops, not just refreshments, but music, laughter and dancing.

In their training before leaving the US, the women were taught how to let the soldiers win at board games, talk about baseball and provoke a smile. Over months at war, they became trustworthy listeners, as soldiers took them aside to confess broken hearts, or fear, or shame or guilt...whatever they had to get off their chest and had no one else they could talk to in the middle of a war.

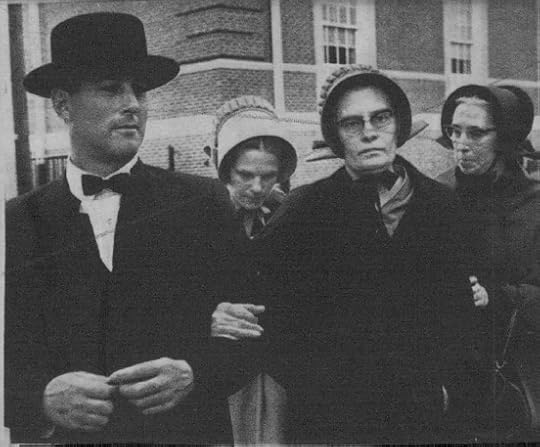

During WWII, the women hated being called Donut Dollies, but since then, as their contributions to the war effort become more well-known and honored, the name had gained a deeper meaning. And clubmobilers, their official name, is so awkward. Photos on the fly leaves of the book show Phyllis Irene McLaughlin in her Red Cross uniform (top right) and Phyllis, Jill Pitts Knappenberger and Helen Anderson respectively (left to right) in front of the Cheyenne. (top left). Not unusual for the Red Cross women to find themselves behind enemy lines, as did Luis's mother, who hid in a barn covered with hay, while first German and then Russian soldiers attacked local women. She listened all night to their screams, so terrified, she prayed the soldiers would stay busy and not find her.

Photos on the fly leaves of the book show Phyllis Irene McLaughlin in her Red Cross uniform (top right) and Phyllis, Jill Pitts Knappenberger and Helen Anderson respectively (left to right) in front of the Cheyenne. (top left). Not unusual for the Red Cross women to find themselves behind enemy lines, as did Luis's mother, who hid in a barn covered with hay, while first German and then Russian soldiers attacked local women. She listened all night to their screams, so terrified, she prayed the soldiers would stay busy and not find her.

Luis said she could not forgive herself for that, and it became the root of nightmares later in life. Many nights as a teen, he was unable to sleep, hearing his mother's nightmares, her crying and yelling through the night.

"And it was not often what she’d seen but what she had heard. And I think that’s what damned her. I think that’s what she heard at night when she tried to sleep,” Luis told me.

Phyllis was serious injured at the end of the war, and suffered from physical pain along with what we now understand is Post Traumatic Stress.

Luis Alberto Uurea, is the author of more than twenty books including fiction, nonfiction and poetry, planned to write a nonfiction book on his mom's wartime experience until he found that fire had destroyed the WWII records. The project languished until he discovered (Jill Pitts) Knappenberger lived not a two-hour drive away. On a visit he discovered the 95-year-old had a great memory and a trove of letters, diaries and photos to supplement those of his mother.

"That's when the novel was born," he said.

In the novel, the character Irene is modeled on Phyllis and the character Dorothy stands in for Jill. But have hearing the author talk about the two women, it's difficult for me to separate the women from the characters in the story. Phyllis at right and Jill, second from right, pose with the others in their crew and two soldiers. Friendship is at the crux of the novel. Two women from very different backgrounds, one from New York City, the other an Indiana farm woman, rub elbows in a tiny kitchen on wheels for days on end. At night they often sleep side by side under the truck because they are safer there if a bomb hits the truck.

Phyllis at right and Jill, second from right, pose with the others in their crew and two soldiers. Friendship is at the crux of the novel. Two women from very different backgrounds, one from New York City, the other an Indiana farm woman, rub elbows in a tiny kitchen on wheels for days on end. At night they often sleep side by side under the truck because they are safer there if a bomb hits the truck.

The women enjoyed their freedom far from home, had hilarious fun and faced the dangers of battle unarmed. Their friendship is forged in steel the day the Dorothy says to Irene:

"I think about my duty...and I think about you. We are all we have right now. You and me. I think about us getting through this...I will walk through fire for you. I need to know you will do the same for me...this is our story."

Irene embraced her friend. The two held each other, and though Irene wanted to speak, she could not. She trusted no words. But she trusted Dorothy to know what was true." pp. 149-150.

Below, to give you a picture, is the crew and driver of the Magnolia clubmobile "somewhere in Europe." They hauled their own water and gas tanks, regularly refilled by Army suppliers. Thanks to Wendy over at the

The Butterfly Balcony

,

I have a few more photos showing the women in action.

Thanks to Wendy over at the

The Butterfly Balcony

,

I have a few more photos showing the women in action.  Above, the boys line up for service at the North Dakota.

Above, the boys line up for service at the North Dakota.  Virginia 'Ginny' Sherwood, Captain of the North Dakota crew Age 24, from Portland Oregon mixes the dough for donuts.

Virginia 'Ginny' Sherwood, Captain of the North Dakota crew Age 24, from Portland Oregon mixes the dough for donuts.  Dorothy 'Mike' Myrick, Age 24, Whiting, Indiana, and Katherine 'Tatty' Spaatz age 22 (no home state) select records to play on the Victrola and broadcast over the loudspeaker mounted on the outside of each truck. Note the rack of donuts ready to go at the left of the photo. More than 7,000 young women volunteered for service with the Red Cross during World War II. One enticement for some was that, unlike the Woman's Army and Navy corps, they were guaranteed service overseas.

Dorothy 'Mike' Myrick, Age 24, Whiting, Indiana, and Katherine 'Tatty' Spaatz age 22 (no home state) select records to play on the Victrola and broadcast over the loudspeaker mounted on the outside of each truck. Note the rack of donuts ready to go at the left of the photo. More than 7,000 young women volunteered for service with the Red Cross during World War II. One enticement for some was that, unlike the Woman's Army and Navy corps, they were guaranteed service overseas.

At the recent event in Spokane Luis Alberto Urrea said Good Night, Irene, "means “everything to me. I’ve put everything I know as a writer into it, and I’m comfortable knowing that I can’t reach this height again.”

Pulitzer Prize finalist Luis Alberto Uurea came through Spokane, WA, on tour publicizing his newest book Good Night, Irene.

Very soon after starting to read this novel, I wished that I had written it, or rather, written a nonfiction book about the Donut Dollies of World War II. These women served coffee, donuts and a slice of home to soldiers on the front lines of battle.

I could not have written this book because Luis Alberto Uurea based it on the true-life experiences of his mother, Phyllis Irene McLaughlin, who traveled across Europe with Patton's army. It's a great adventure story of women's strength, friendship and sacrifice.

I could not have written this book because Luis Alberto Uurea based it on the true-life experiences of his mother, Phyllis Irene McLaughlin, who traveled across Europe with Patton's army. It's a great adventure story of women's strength, friendship and sacrifice.

The fictional account follows closely the actual service route traveled by Phyllis and her partners Jill Pitts and Helen Anderson in the clubmobile Cheyanne. They saw Utah Beach, shortly after D-Day, skirmishes across France, where right in the middle of the Battle of Bastogne and the horrors of the Buchenwald death camp.

After reading the book, I had the honor of interviewing the author on stage for The Spokesman-Review’s Northwest Passages book club last week at the Bing Crosby Theater in downtown Spokane. Read more about that night here...

Luis Alberto Urrea answers a question from me at The Spokesman-Review’s Northwest Passages book club event July 6, 2023 at the Bing Crosby Theater in downtown Spokane, WA. The first Red Cross Clubmobile arrived in France just days after the D-Day invasion, and that summer, 80 of the modified two-and-a-half-ton GMC trucks trundled across the countryside serving the troops, not just refreshments, but music, laughter and dancing.