Mary Cronk Farrell's Blog, page 6

April 8, 2019

Black Woman Spy Broke Barriers

But first...

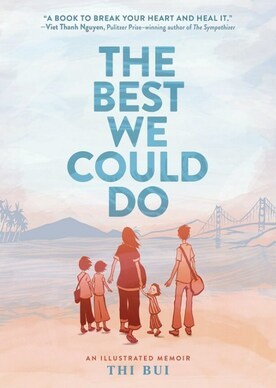

I discovered a wonderful author whom I should have known about before at the recent Association of Writing Programs conference. I presented on a panel about writing nonfiction for kids in the age of fake news. Luckily, a panel I picked to attend featured Thi Bui and a reader's theater performance of a section of her book The Best We Could Do . Thi Bui is an author/cartoonist and the book is a graphic novel memoir. It tells the story her family’s immigration to the United States during the Vietnam War when Thi was three, combining the personal and political as it follows the family's life as refugees in America.

Thi Bui is an author/cartoonist and the book is a graphic novel memoir. It tells the story her family’s immigration to the United States during the Vietnam War when Thi was three, combining the personal and political as it follows the family's life as refugees in America.

What's Thi working on now? Here's what she said in an interview with Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

I spent a long time thinking about Vietnam’s past, and now I’d like to spend some time thinking about its present and future. I’ve been following news stories about droughts, floods, and the saltwater intrusion that’s been wreaking havoc on the rice farmers of the Mekong Delta.

Climate change is a reality there, and much closer than in the U.S. because the Mekong region is only six feet above sea level and grows half the country’s rice. About a million people will be displaced by the sea rising, possibly in my lifetime. [In light of] the climate change denial that’s happening here, this is maddening. I have to explore this.

Read the full interview here.

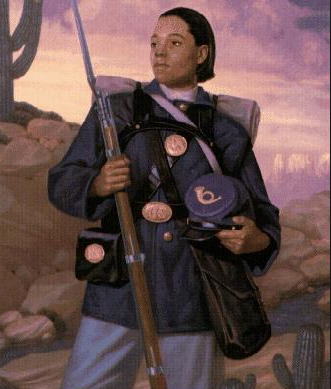

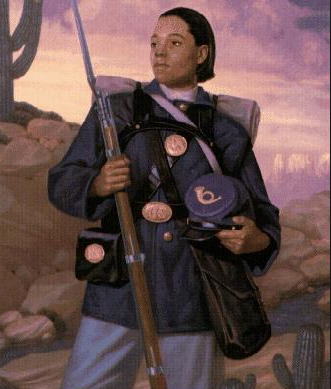

And now for this week's feature story. Her dad told her to stop whining and complaining. Here's what she did. A Black Woman Spy Breaking Barriers Captain Gail Harris confronted racism and sexism to become the U.S. Navy’s first black and female intelligence officer, and the highest-ranking black woman in the navy when she retired in 2001.

As a five-year-old watching the movie Wing and a Prayer , Gail saw actor Don Ameche’s character gave an intelligence briefing to Navy pilots after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Then and there, she decided she wanted that job.

“My father was in the army in the after-math of WWII when it was still segregated, so he could have bust my bubble right there and told me that it was rare that the navy only had a handful of African-American male captains, let alone female," Gail says. "But he didn’t. He turned to me and said, 'This is American, you can be whatever you want to be.'”

If Gail had known then that women were not allowed combat roles in the U.S. military, she may have given up the idea. Or maybe she would have wanted it all the more. Gail believes that her sense of humor, as well as her intellect helped her break an important barrier in 1973, when she became the first female assigned to an operational combat job as an intelligence officer.

Gail believes that her sense of humor, as well as her intellect helped her break an important barrier in 1973, when she became the first female assigned to an operational combat job as an intelligence officer.

Her first years as the only woman in a squad of 360 men demanded every bit of her confidence and nerve.

"People would look at me and refuse to salute me and I would smile and salute them first and say “Good Morning! Isn’t this a great day? That usually embarrassed them," Gail remembers.

"Those first few years were pretty brutal. But my father told me to stop whining and complaining....He told me that if I couldn’t stand the heat, get out of the Navy and get a job as a janitor. Most importantly, he told me that if someone had a problem because I was a woman or Black, it was their problem, don’t make it mine." In her 28-year naval career, Gail served a crucial role in naval intelligence during every major conflict from the Cold War and El Salvador to Desert Storm and Kosovo.

In her 28-year naval career, Gail served a crucial role in naval intelligence during every major conflict from the Cold War and El Salvador to Desert Storm and Kosovo.

She carved out a string of firsts for African American woman, including working as an instructor at the Armed Forces Air Intelligence Training Center where she built the navy's first course on Ocean Surveillance Information Systems.

When Gail retired, she thought her work for civil rights was done. Until Donald Trump became president. For the first time in her life, Gail joined a political march. Gail Harris at the Women's March in Washington D.C., January 2017.

"I was of the mindset I could change things by excelling in my work, by proving doubters and haters wrong," Gail says.

Gail Harris at the Women's March in Washington D.C., January 2017.

"I was of the mindset I could change things by excelling in my work, by proving doubters and haters wrong," Gail says.

But she had begun to feel an unease, that was confirmed for her on a visit to her mother in Arkansas, when she and a white friend encountered looks of hate and disgust from white shoppers at the grocery store.

"I realized at that moment, in all of the times I’d traveled to the new south, I had never seen a black person and a white person sitting together at the same table in restaurants or hanging out. We had broken an unwritten social code. It was obvious to any observer we were old friends who treated each other as social equals.

"Those attitudes are so backward to most Americans, many may prefer to believe I misread that situation. But I know “hate” when I see it."

Gail showed up for the women's march for the sake of the next generation of

women and minorities, saying, "I don’t want the clock pushed back on my watch."

In her retirement, Gail also keeps a close watch on what's happening in the field of cyber security. In the Navy, Gail final assignment was developing an intelligence architecture for cyber warfare. She's worried now, that it may take a catastrophe on the level of 9/11 to get all the different federal, civilian and international agencies to cooperate in fighting cyber warfare and crime.

In the Navy, Gail final assignment was developing an intelligence architecture for cyber warfare. She's worried now, that it may take a catastrophe on the level of 9/11 to get all the different federal, civilian and international agencies to cooperate in fighting cyber warfare and crime.

The bad guys and girls are just scratching the service of the havoc they can bring about. Technology is changing at the speed of thought and the rules and regulations dealing with it are moving at the speed of a glacier.

[We] must work with our allies to develop a common cyber lexicon and agree on what constitutes a cyber attack, a cyber act of war, etc. Does this include malign influence operations via social media, for example."

To protect American interests, government and industry will have to work together more closely and share information as private industry owns 90% of the critical cyber infrastructure.

Are you wondering if this woman ever relaxes? Why, yes, she does. While playing air guitar during her stint as a disc jockey for an R& B radio show on KDUR, a public radio station in Durango, Colorado. Gail Harris, Courtesy KDUP, Durango, CO.

"Music for me, even without being a disc jockey, it saved my soul. My job [in navy intelligence] was so intense that when I left my job frequently I couldn’t go to sleep."

Gail Harris, Courtesy KDUP, Durango, CO.

"Music for me, even without being a disc jockey, it saved my soul. My job [in navy intelligence] was so intense that when I left my job frequently I couldn’t go to sleep."

Retired Navy Captain Gail Harris Role sleeps well now, and believes the outlook for women in general and the military in particular is positive. Gender equality in on the agenda, on the radar scope as we say in the military and it’s not going to get kicked off.”

Gail predicts within less than ten years, Americans will see a female Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and/or a female Secretary of Defense.

Sources:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5NSoDkOpOtI (The BBC)

https://limacharlienews.com/veterans/captain-gail-harris/

https://limacharlienews.com/cyber/gailforce-blinking-red-cyber-war-and-malign-influence-operations-today/

https://limacharlienews.com/op-ed/gailforce-reflections-from-the-womens-march/

I discovered a wonderful author whom I should have known about before at the recent Association of Writing Programs conference. I presented on a panel about writing nonfiction for kids in the age of fake news. Luckily, a panel I picked to attend featured Thi Bui and a reader's theater performance of a section of her book The Best We Could Do .

Thi Bui is an author/cartoonist and the book is a graphic novel memoir. It tells the story her family’s immigration to the United States during the Vietnam War when Thi was three, combining the personal and political as it follows the family's life as refugees in America.

Thi Bui is an author/cartoonist and the book is a graphic novel memoir. It tells the story her family’s immigration to the United States during the Vietnam War when Thi was three, combining the personal and political as it follows the family's life as refugees in America.What's Thi working on now? Here's what she said in an interview with Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

I spent a long time thinking about Vietnam’s past, and now I’d like to spend some time thinking about its present and future. I’ve been following news stories about droughts, floods, and the saltwater intrusion that’s been wreaking havoc on the rice farmers of the Mekong Delta.

Climate change is a reality there, and much closer than in the U.S. because the Mekong region is only six feet above sea level and grows half the country’s rice. About a million people will be displaced by the sea rising, possibly in my lifetime. [In light of] the climate change denial that’s happening here, this is maddening. I have to explore this.

Read the full interview here.

And now for this week's feature story. Her dad told her to stop whining and complaining. Here's what she did. A Black Woman Spy Breaking Barriers Captain Gail Harris confronted racism and sexism to become the U.S. Navy’s first black and female intelligence officer, and the highest-ranking black woman in the navy when she retired in 2001.

As a five-year-old watching the movie Wing and a Prayer , Gail saw actor Don Ameche’s character gave an intelligence briefing to Navy pilots after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Then and there, she decided she wanted that job.

“My father was in the army in the after-math of WWII when it was still segregated, so he could have bust my bubble right there and told me that it was rare that the navy only had a handful of African-American male captains, let alone female," Gail says. "But he didn’t. He turned to me and said, 'This is American, you can be whatever you want to be.'”

If Gail had known then that women were not allowed combat roles in the U.S. military, she may have given up the idea. Or maybe she would have wanted it all the more.

Gail believes that her sense of humor, as well as her intellect helped her break an important barrier in 1973, when she became the first female assigned to an operational combat job as an intelligence officer.

Gail believes that her sense of humor, as well as her intellect helped her break an important barrier in 1973, when she became the first female assigned to an operational combat job as an intelligence officer.Her first years as the only woman in a squad of 360 men demanded every bit of her confidence and nerve.

"People would look at me and refuse to salute me and I would smile and salute them first and say “Good Morning! Isn’t this a great day? That usually embarrassed them," Gail remembers.

"Those first few years were pretty brutal. But my father told me to stop whining and complaining....He told me that if I couldn’t stand the heat, get out of the Navy and get a job as a janitor. Most importantly, he told me that if someone had a problem because I was a woman or Black, it was their problem, don’t make it mine."

In her 28-year naval career, Gail served a crucial role in naval intelligence during every major conflict from the Cold War and El Salvador to Desert Storm and Kosovo.

In her 28-year naval career, Gail served a crucial role in naval intelligence during every major conflict from the Cold War and El Salvador to Desert Storm and Kosovo.She carved out a string of firsts for African American woman, including working as an instructor at the Armed Forces Air Intelligence Training Center where she built the navy's first course on Ocean Surveillance Information Systems.

When Gail retired, she thought her work for civil rights was done. Until Donald Trump became president. For the first time in her life, Gail joined a political march.

Gail Harris at the Women's March in Washington D.C., January 2017.

"I was of the mindset I could change things by excelling in my work, by proving doubters and haters wrong," Gail says.

Gail Harris at the Women's March in Washington D.C., January 2017.

"I was of the mindset I could change things by excelling in my work, by proving doubters and haters wrong," Gail says.

But she had begun to feel an unease, that was confirmed for her on a visit to her mother in Arkansas, when she and a white friend encountered looks of hate and disgust from white shoppers at the grocery store.

"I realized at that moment, in all of the times I’d traveled to the new south, I had never seen a black person and a white person sitting together at the same table in restaurants or hanging out. We had broken an unwritten social code. It was obvious to any observer we were old friends who treated each other as social equals.

"Those attitudes are so backward to most Americans, many may prefer to believe I misread that situation. But I know “hate” when I see it."

Gail showed up for the women's march for the sake of the next generation of

women and minorities, saying, "I don’t want the clock pushed back on my watch."

In her retirement, Gail also keeps a close watch on what's happening in the field of cyber security.

In the Navy, Gail final assignment was developing an intelligence architecture for cyber warfare. She's worried now, that it may take a catastrophe on the level of 9/11 to get all the different federal, civilian and international agencies to cooperate in fighting cyber warfare and crime.

In the Navy, Gail final assignment was developing an intelligence architecture for cyber warfare. She's worried now, that it may take a catastrophe on the level of 9/11 to get all the different federal, civilian and international agencies to cooperate in fighting cyber warfare and crime.The bad guys and girls are just scratching the service of the havoc they can bring about. Technology is changing at the speed of thought and the rules and regulations dealing with it are moving at the speed of a glacier.

[We] must work with our allies to develop a common cyber lexicon and agree on what constitutes a cyber attack, a cyber act of war, etc. Does this include malign influence operations via social media, for example."

To protect American interests, government and industry will have to work together more closely and share information as private industry owns 90% of the critical cyber infrastructure.

Are you wondering if this woman ever relaxes? Why, yes, she does. While playing air guitar during her stint as a disc jockey for an R& B radio show on KDUR, a public radio station in Durango, Colorado.

Gail Harris, Courtesy KDUP, Durango, CO.

"Music for me, even without being a disc jockey, it saved my soul. My job [in navy intelligence] was so intense that when I left my job frequently I couldn’t go to sleep."

Gail Harris, Courtesy KDUP, Durango, CO.

"Music for me, even without being a disc jockey, it saved my soul. My job [in navy intelligence] was so intense that when I left my job frequently I couldn’t go to sleep."

Retired Navy Captain Gail Harris Role sleeps well now, and believes the outlook for women in general and the military in particular is positive. Gender equality in on the agenda, on the radar scope as we say in the military and it’s not going to get kicked off.”

Gail predicts within less than ten years, Americans will see a female Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and/or a female Secretary of Defense.

Sources:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5NSoDkOpOtI (The BBC)

https://limacharlienews.com/veterans/captain-gail-harris/

https://limacharlienews.com/cyber/gailforce-blinking-red-cyber-war-and-malign-influence-operations-today/

https://limacharlienews.com/op-ed/gailforce-reflections-from-the-womens-march/

Published on April 08, 2019 15:11

March 25, 2019

One Woman Army Stands up to Al Qaeda

Did you know the Trump Administration is escalating our war in Somalia?

I must admit, I didn't know we had a war in Somalia.

It's part of the War on Terrorism, and it shakes out to at least 500 troops on the ground in Somalia, and increasing numbers of air strikes over the the last two months.

The attacks killed 225 people in January and February, according to the New York Times, compared to 326 in all of 2018. 20th Special Forces Group participating in Flintlock 18, exercise in Niger, Africa on April 16, 2018. (US Military Photo) Of course, these air strikes are targeting bad guys, al Qaeda Shabaab insurgents, and supporting good guys, the U.N.-backed Somalian government troops.

20th Special Forces Group participating in Flintlock 18, exercise in Niger, Africa on April 16, 2018. (US Military Photo) Of course, these air strikes are targeting bad guys, al Qaeda Shabaab insurgents, and supporting good guys, the U.N.-backed Somalian government troops.

Shortly after President Trump took office, he declared Somalia an “area of active hostilities” subject to war-zone rules. This designation allows the U.S. military to readily attack Shabab militants, including foot soldiers with no special skills or role, and it permits the killing of civilian bystanders.

Al-Shabaab fighters conduct military exercises in northern Mogadishu, Somalia, 2010. (Photo Mohamed Sheikh Nor/AP) Four people died in a U.S. assault March 10th, 2019, according to a relative of one of the victims. The relative told Reuters one of those killed was an employee of the firm Hormuud Telecom.

Al-Shabaab fighters conduct military exercises in northern Mogadishu, Somalia, 2010. (Photo Mohamed Sheikh Nor/AP) Four people died in a U.S. assault March 10th, 2019, according to a relative of one of the victims. The relative told Reuters one of those killed was an employee of the firm Hormuud Telecom.

The U.S. Africa Command acknowledged it carried out the air strike on Sunday, saying that three militants had died in the attack, as well as three separate attacks in a five-day stretch of February killing 35, 20 and 26 people. More on the war in Somalia here.

The Shabab have proved resilient against the American airstrikes, and continue to carry out regular bombings in East Africa, and the stepped-up attacks are exacerbating the humanitarian crisis in Somalia.

In the midst of decades of violence, drought and famine in Somalia, there's one woman who's been making enemies peaceful, feeding the hungry and standing up to al Qaeda like a one woman army.

Her name is Dr. Hawa Abdi, the saint Rambo comparison came from Glamour Magazine , when it named Dr. Abdi Woman of the Year in 2010, along with her two daughters, also doctors in Somalia. From left: Dr. Amina Mohamed, Dr. Hawa Abdi and Dr. Deqo Mohamed, photographed during a business trip to Geneva, Switzerland, on September 18, 2010. (Photo courtesy Glamour)

From left: Dr. Amina Mohamed, Dr. Hawa Abdi and Dr. Deqo Mohamed, photographed during a business trip to Geneva, Switzerland, on September 18, 2010. (Photo courtesy Glamour)

In the refugee camp where Dr. Abdi convinced enemies to lay down their grudges, she called simply "Mama Hawa".

In the refugee camp where Dr. Abdi convinced enemies to lay down their grudges, she called simply "Mama Hawa".

"They are very angry and mentally not [there] when they are coming to you," Abdi she told NPR. "Their parents or their brothers, their wives, their fathers were killed in front of them. They're coming to me. There is no government. The whole society became violent."

Dr. Abdi became one of Somalia's first female gynecologists in 1971, after medical school in the Soviet Ukraine.

She worked in Mogadishu’s largest

hospital until 1983, when she left, deciding she wanted to provide free medical care to dirt-poor women who would never be able to afford having a baby in a hospital.

"I decided to open my own clinic next to our family’s home in a rural area, 15 miles from the capital. Within a few months, I was seeing 100 patients a day."

When the country exploded in civil war in 1991 and the Somalian government collapsed, Dr. Abdi's clinic and her home turned into a triage center. Hundreds, than thousands of people, mostly women and children, settled in temporary shelter in the doctor's family's ancestral lands surrounding the clinic.

Dr. Abdi sold her family’s gold to buy food to keep the children alive and give adults the strength to dig graves. We clung to one another and we survived, but the fighting continued," said Dr. Abdi. For the following two decades, destruction, violence, drought and famine ravaged her homeland and Dr. Abdi raised her own children while providing a safe haven for refugees. Her one-room clinic became a 400 bed hospital, and her thousand-acre farm

For the following two decades, destruction, violence, drought and famine ravaged her homeland and Dr. Abdi raised her own children while providing a safe haven for refugees. Her one-room clinic became a 400 bed hospital, and her thousand-acre farm

a displaced person camp.

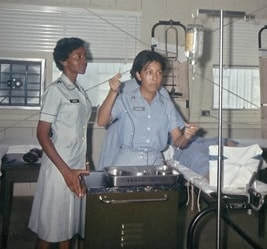

She worked 12-hour days, 7 days a week, delivering babies, treating gunshot wounds, and providing IV lines of nourishment to starving children.

By 2010, With help from the U.N. "Hawa's Camp" was providing food, clean water, and shelter to 90,000 refugees. Dr. Abdi had two strict rules to preserve the peace. First, no one is allowed to talk about clan or family, the most divisive issue in Somalia. Second, men are not allowed to beat their wives. Dr. Hawa in the camp (2007). Photo: (Kuni Takahashi/Getty Images) Though conditions have improved in the camp, Somalia remains wracked by war and over the years local warlords tried to shut her operation down at gunpoint They've blocked aid, raided her camp with machine guns, and threatened her life several times.

Dr. Hawa in the camp (2007). Photo: (Kuni Takahashi/Getty Images) Though conditions have improved in the camp, Somalia remains wracked by war and over the years local warlords tried to shut her operation down at gunpoint They've blocked aid, raided her camp with machine guns, and threatened her life several times.

In May 2010 Islamist militants arrived at the gate, demanding Dr. Abdi turn over management of the hospital and camp to them, as women are not allowed to hold positions of power under their brand of Islam. She invited them to sit down to dinner.

After eating, "Six Hizbul Islam soldiers, jittery, aggressive young men with -henna-dyed beards, wearing red-and-white checkered scarves, their index fingers forever on the triggers of their guns," ordered her to leave.

Elders in the camp warned her she'd be shot, but Dr. Abdi stood up to the militants.

"At least I will die with dignity," she said. "They did not shoot me; they pushed back their chairs and left." Hope Village, near Mogadishu, Somalia. (Photo DHA Foundation) A week later they were back, 750-strong. This time they fired on the hospital and camp.

Hope Village, near Mogadishu, Somalia. (Photo DHA Foundation) A week later they were back, 750-strong. This time they fired on the hospital and camp.

"A BBC producer called me during some of the heaviest shelling," said Dr. Abdi. "I told him that the militiamen’s targets were the maternity and surgical wards, and the pediatric malnutrition section. One woman recovering from a C-section I’d performed earlier that day had stood up to run.

"Terrified mothers detached feeding tubes and IV lines from their dehydrated children’s noses and arms to flee into the woods, away from the indiscriminate shooting. A group of militiamen stormed into my room. 'You’ve spoken to the radio, haven’t you?' shouted one."

The armed men demanded her cellphone and and hauled Dr. Abdi and six nurses away, holding them hostage for ten hours. Then the gunmen returned her phone, saying. “You have many supporters,” and ordering her to call people to say she was alive and unharmed.

The following day armed men appear to tell her not to re-open the hospital. She said she would not reopen without a written apology.

“Dr. Hawa, you are stubborn,” one told her.

“I do something for my people and my country,” she said. “What have you done for your people and your country?”

A week later their second-in-command returned with a written apology.

In 2012, Dr. Abdi was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. School at Hope Village, Somalia. (Photo DHA Foundation)

School at Hope Village, Somalia. (Photo DHA Foundation)

Today 850 young people attend school in the camp, and Mama Hawa insists that equal numbers of boys and girls go to school.

Dr. Adbi now, in her early 70s, runs a foundation to raise money for operations, while the camp and hospital are run by her daughter, Deqo Mohamed, who also became a doctor. It's mission is to secure basic human rights in Somalia through building sustainable institutions in healthcare, education, agriculture, and social entrepreneurship.

Sources:

https://www.dhaf.org/our-story

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/10/us...

http://www.asafeworldforwomen.org/wom...

I must admit, I didn't know we had a war in Somalia.

It's part of the War on Terrorism, and it shakes out to at least 500 troops on the ground in Somalia, and increasing numbers of air strikes over the the last two months.

The attacks killed 225 people in January and February, according to the New York Times, compared to 326 in all of 2018.

20th Special Forces Group participating in Flintlock 18, exercise in Niger, Africa on April 16, 2018. (US Military Photo) Of course, these air strikes are targeting bad guys, al Qaeda Shabaab insurgents, and supporting good guys, the U.N.-backed Somalian government troops.

20th Special Forces Group participating in Flintlock 18, exercise in Niger, Africa on April 16, 2018. (US Military Photo) Of course, these air strikes are targeting bad guys, al Qaeda Shabaab insurgents, and supporting good guys, the U.N.-backed Somalian government troops. Shortly after President Trump took office, he declared Somalia an “area of active hostilities” subject to war-zone rules. This designation allows the U.S. military to readily attack Shabab militants, including foot soldiers with no special skills or role, and it permits the killing of civilian bystanders.

Al-Shabaab fighters conduct military exercises in northern Mogadishu, Somalia, 2010. (Photo Mohamed Sheikh Nor/AP) Four people died in a U.S. assault March 10th, 2019, according to a relative of one of the victims. The relative told Reuters one of those killed was an employee of the firm Hormuud Telecom.

Al-Shabaab fighters conduct military exercises in northern Mogadishu, Somalia, 2010. (Photo Mohamed Sheikh Nor/AP) Four people died in a U.S. assault March 10th, 2019, according to a relative of one of the victims. The relative told Reuters one of those killed was an employee of the firm Hormuud Telecom.The U.S. Africa Command acknowledged it carried out the air strike on Sunday, saying that three militants had died in the attack, as well as three separate attacks in a five-day stretch of February killing 35, 20 and 26 people. More on the war in Somalia here.

The Shabab have proved resilient against the American airstrikes, and continue to carry out regular bombings in East Africa, and the stepped-up attacks are exacerbating the humanitarian crisis in Somalia.

Why all the bad news?Why all this bad news? Just setting the stage for this feature story.

Just setting the stage for this feature story....

In the midst of decades of violence, drought and famine in Somalia, there's one woman who's been making enemies peaceful, feeding the hungry and standing up to al Qaeda like a one woman army.

Her name is Dr. Hawa Abdi, the saint Rambo comparison came from Glamour Magazine , when it named Dr. Abdi Woman of the Year in 2010, along with her two daughters, also doctors in Somalia.

From left: Dr. Amina Mohamed, Dr. Hawa Abdi and Dr. Deqo Mohamed, photographed during a business trip to Geneva, Switzerland, on September 18, 2010. (Photo courtesy Glamour)

From left: Dr. Amina Mohamed, Dr. Hawa Abdi and Dr. Deqo Mohamed, photographed during a business trip to Geneva, Switzerland, on September 18, 2010. (Photo courtesy Glamour)

In the refugee camp where Dr. Abdi convinced enemies to lay down their grudges, she called simply "Mama Hawa".

In the refugee camp where Dr. Abdi convinced enemies to lay down their grudges, she called simply "Mama Hawa"."They are very angry and mentally not [there] when they are coming to you," Abdi she told NPR. "Their parents or their brothers, their wives, their fathers were killed in front of them. They're coming to me. There is no government. The whole society became violent."

Dr. Abdi became one of Somalia's first female gynecologists in 1971, after medical school in the Soviet Ukraine.

She worked in Mogadishu’s largest

hospital until 1983, when she left, deciding she wanted to provide free medical care to dirt-poor women who would never be able to afford having a baby in a hospital.

"I decided to open my own clinic next to our family’s home in a rural area, 15 miles from the capital. Within a few months, I was seeing 100 patients a day."

When the country exploded in civil war in 1991 and the Somalian government collapsed, Dr. Abdi's clinic and her home turned into a triage center. Hundreds, than thousands of people, mostly women and children, settled in temporary shelter in the doctor's family's ancestral lands surrounding the clinic.

Dr. Abdi sold her family’s gold to buy food to keep the children alive and give adults the strength to dig graves. We clung to one another and we survived, but the fighting continued," said Dr. Abdi.

For the following two decades, destruction, violence, drought and famine ravaged her homeland and Dr. Abdi raised her own children while providing a safe haven for refugees. Her one-room clinic became a 400 bed hospital, and her thousand-acre farm

For the following two decades, destruction, violence, drought and famine ravaged her homeland and Dr. Abdi raised her own children while providing a safe haven for refugees. Her one-room clinic became a 400 bed hospital, and her thousand-acre farma displaced person camp.

She worked 12-hour days, 7 days a week, delivering babies, treating gunshot wounds, and providing IV lines of nourishment to starving children.

By 2010, With help from the U.N. "Hawa's Camp" was providing food, clean water, and shelter to 90,000 refugees. Dr. Abdi had two strict rules to preserve the peace. First, no one is allowed to talk about clan or family, the most divisive issue in Somalia. Second, men are not allowed to beat their wives.

Dr. Hawa in the camp (2007). Photo: (Kuni Takahashi/Getty Images) Though conditions have improved in the camp, Somalia remains wracked by war and over the years local warlords tried to shut her operation down at gunpoint They've blocked aid, raided her camp with machine guns, and threatened her life several times.

Dr. Hawa in the camp (2007). Photo: (Kuni Takahashi/Getty Images) Though conditions have improved in the camp, Somalia remains wracked by war and over the years local warlords tried to shut her operation down at gunpoint They've blocked aid, raided her camp with machine guns, and threatened her life several times.In May 2010 Islamist militants arrived at the gate, demanding Dr. Abdi turn over management of the hospital and camp to them, as women are not allowed to hold positions of power under their brand of Islam. She invited them to sit down to dinner.

After eating, "Six Hizbul Islam soldiers, jittery, aggressive young men with -henna-dyed beards, wearing red-and-white checkered scarves, their index fingers forever on the triggers of their guns," ordered her to leave.

Elders in the camp warned her she'd be shot, but Dr. Abdi stood up to the militants.

"At least I will die with dignity," she said. "They did not shoot me; they pushed back their chairs and left."

Hope Village, near Mogadishu, Somalia. (Photo DHA Foundation) A week later they were back, 750-strong. This time they fired on the hospital and camp.

Hope Village, near Mogadishu, Somalia. (Photo DHA Foundation) A week later they were back, 750-strong. This time they fired on the hospital and camp."A BBC producer called me during some of the heaviest shelling," said Dr. Abdi. "I told him that the militiamen’s targets were the maternity and surgical wards, and the pediatric malnutrition section. One woman recovering from a C-section I’d performed earlier that day had stood up to run.

"Terrified mothers detached feeding tubes and IV lines from their dehydrated children’s noses and arms to flee into the woods, away from the indiscriminate shooting. A group of militiamen stormed into my room. 'You’ve spoken to the radio, haven’t you?' shouted one."

The armed men demanded her cellphone and and hauled Dr. Abdi and six nurses away, holding them hostage for ten hours. Then the gunmen returned her phone, saying. “You have many supporters,” and ordering her to call people to say she was alive and unharmed.

The following day armed men appear to tell her not to re-open the hospital. She said she would not reopen without a written apology.

“Dr. Hawa, you are stubborn,” one told her.

“I do something for my people and my country,” she said. “What have you done for your people and your country?”

A week later their second-in-command returned with a written apology.

In 2012, Dr. Abdi was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

School at Hope Village, Somalia. (Photo DHA Foundation)

School at Hope Village, Somalia. (Photo DHA Foundation) Today 850 young people attend school in the camp, and Mama Hawa insists that equal numbers of boys and girls go to school.

Dr. Adbi now, in her early 70s, runs a foundation to raise money for operations, while the camp and hospital are run by her daughter, Deqo Mohamed, who also became a doctor. It's mission is to secure basic human rights in Somalia through building sustainable institutions in healthcare, education, agriculture, and social entrepreneurship.

Sources:

https://www.dhaf.org/our-story

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/10/us...

http://www.asafeworldforwomen.org/wom...

Published on March 25, 2019 09:57

February 22, 2019

Racist Memorabilia or Educational Artifact?

You just never know where your research will take you.

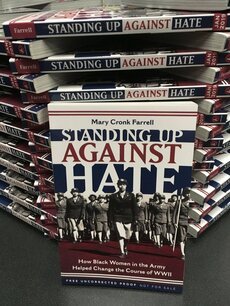

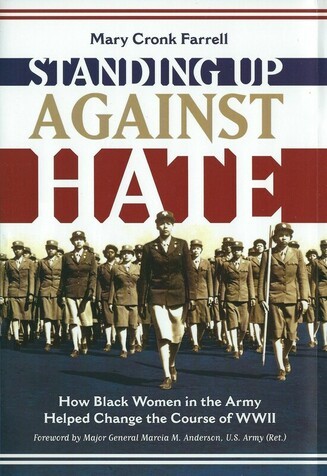

You just never know where your research will take you. Searching for information on a surviving member of the the all-black 6888th Battalion spotlighted in Standing Up Against Hate: How Black Women in the Army Helped Change the Course of WWII , I discovered the debate surrounding a growing market for black memorabilia.

I've never actually seen one of the hitching post figures of a cartoonish young black boy with exaggerated features, which I thought was now universally considered racist. But I've learned a lot about racism in America in the last couple years and maybe shouldn't have been surprised by the Little Black Sambo cookie jars and Mamie salt and pepper shakers being sold on E-bay.

I also didn't expect to find them while researching Fran McClendon, a 101-year-old African American Veteran of WWII.

In late summer of 1943, the Allies won important victories in Italy and New Guinea, and the Nazis and Japanese were retreating.

In late summer of 1943, the Allies won important victories in Italy and New Guinea, and the Nazis and Japanese were retreating.But the war was far from over and the U.S. Army needed more manpower. Congress voted to raise the status of women in the army from supplemental support to official members of the military.

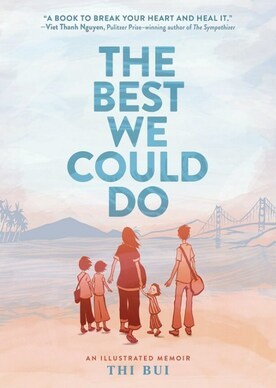

All over the country, the Women's Army Corps recruited volunteers, telling women they could "free a man to fight" and help win the war.

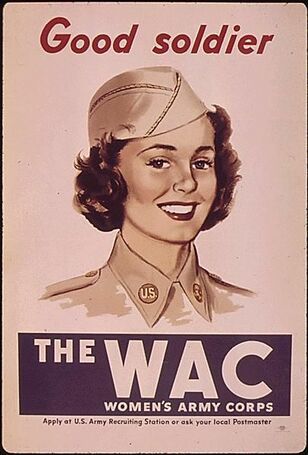

Fran McClendon went with a group of girl friends to talk with a recruiter and they all decided to enlist. A year later, Fran was assigned to the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. It would be the only unit of black women deployed overseas during the war.

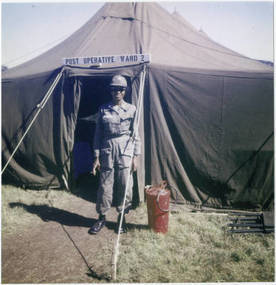

Fran would end up serving 26 years in the military, first the army, then the air force, posted Korea and Vietnam, and retiring at the rank Major.

Fran would end up serving 26 years in the military, first the army, then the air force, posted Korea and Vietnam, and retiring at the rank Major.But it was her WWII assignment in Birmingham, England, where she developed an appreciation for fine crystal and china. The Black WACs' job in England was to sort a huge backlog of mail and re-direct it to soldiers in the field. They worked in shifts around the clock because the packages and letters were crucial to troop morale.

But Fran and the others did have days off to explore the town. Birmingham citizens welcomed the WACs and invited them to tea in their homes and out to restaurants. Crystal and china were everywhere. Fran saw it in shop windows at the weekend markets and soon gained a love of fine craftsmanship.

Many years later, after her military career, Fran went into the antique business. “I love the study of the glass industry and china industry,” she told a reporter recently. Yes, recently. To this day, she runs an antique shop, the Glass Urn in Mesa, AZ, where she deals mostly in American crystal, but has some glassware from Ireland, Sweden and Germany.

Over the years, the Glass Urn has carried a large variety of antiques, occasionally items made in the image of a black person.

Over the years, the Glass Urn has carried a large variety of antiques, occasionally items made in the image of a black person.These types of collectibles, almost always demeaning, have been manufactured in America since the beginning of the slave trade and remained common and popular up through the 1950s.

At times, Fran McClendon has questioned whether to sell certain items of black memorabilia, but she considers them art. “My husband and I loved art and in art you find all kinds of things."

Where Fran sees art, some see historical artifacts that can be educational, and other find these black collectibles racist and offensive.

Where Fran sees art, some see historical artifacts that can be educational, and other find these black collectibles racist and offensive. As an African-American history professor, Donald Guillory, has mixed feelings about black memorabilia. The items can spark conversation about the negative portrayal of blacks, which might be a teachable moment.

“If it’s anything other than learning the context or teaching about it, why would you want something that offensive, or that overtly offensive, in your home?” He concludes.

What I found startling when I happened upon this topic, is the burgeoning popularity of black memorabilia, so much so, that replicas are now being manufactured in China. A documentary on the topic debuted earlier this month on PBS. Read about it here... Or watch the one-hour documentary Black Memorabilia here...

As for Fran McClendon, after forty-years of selling antiques, she's preparing to retire.

“I’m downsizing,” she said. “I want to do things and I know I can’t hold on to everything.”

I hope she holds on to at least one set of glassware that reminds her of Birmingham, England, and her time in the Women's Army Corps.

For further interest, there's a book that goes into some depth about how these racist depictions of blacks continued to be reinvented over the decades of American history. Mamie and Uncle Mose: Black Collectibles and American Sterotyping.

Sources:

http://www.eastvalleytribune.com/local/mesa/mesa-antiques-store-owner-liquidating-life-s-work/article_8d388c76-3163-11e2-b6e4-0019bb2963f4.html

https://www.pinalcentral.com/arizona_news/antique-dealers-see-controversial-african-american-memorabilia-as-part-of/article_eed8b251-42b2-5978-8fc8-682fa9eefb32.html

Published on February 22, 2019 11:16

February 11, 2019

Iconic American Legend on a White Horse Based on a Black Man?

White guys like John Wayne personify our image of the American West, so it might surprise you to know that roughly one in four cowboys riding the range was black.

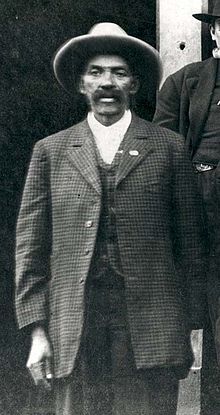

On Saturday night when they went to town, these men couldn't stay in hotels or eat in restaurants. I'm not sure if they could drink and play cards in the saloons, but during the workweek, their skill with a horse, a rope and a gun, could gain them a level of respect. Black cowboys at the "Negro State Fair" in Bonham, Texas, in 1913, photo courtesy Texas State Historical Association. During the most lawless decades of the wild west, at least 25 (probably more) African American men served as deputy U.S. Marshals. There's some evidence to suggest that one of those rough-riding, straight-shooting black lawmen formed the basis for the iconic Lone Ranger.

Black cowboys at the "Negro State Fair" in Bonham, Texas, in 1913, photo courtesy Texas State Historical Association. During the most lawless decades of the wild west, at least 25 (probably more) African American men served as deputy U.S. Marshals. There's some evidence to suggest that one of those rough-riding, straight-shooting black lawmen formed the basis for the iconic Lone Ranger.

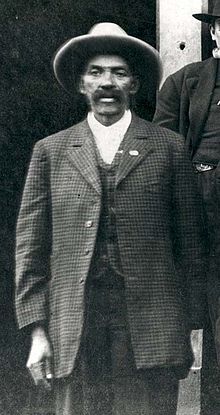

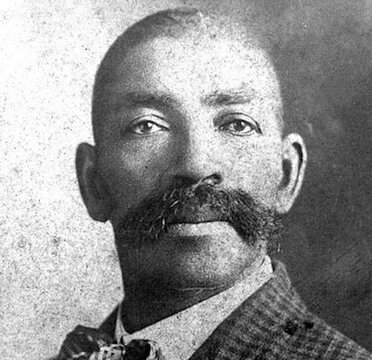

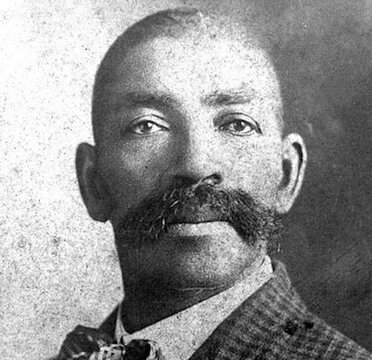

Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves grew famous during his 30-years pursuing and arresting bandits and murders throughout Indian Territory in the late 19th Century. And the former slave has some distinct resemblances to Lone Ranger of radio, comic book, TV and movies.

Bass was born a slave in Arkansas in 1883, and was taken to Texas his owner William Reeves as an 8-year-old boy. When the Civil War broke out, Reeves' son joined the Confederate Army and took Bass with him to the front lines as a servant. U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves Before the war's end, Bass escaped, heading west to what was then called Indian Territory and now the State of Oklahoma. Historians say there he learned horsemanship and tracking skills from Native Americans and also became handy with Colt 45 and a rifle. After emancipation, Bass was just one of many black men looking for work.

U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves Before the war's end, Bass escaped, heading west to what was then called Indian Territory and now the State of Oklahoma. Historians say there he learned horsemanship and tracking skills from Native Americans and also became handy with Colt 45 and a rifle. After emancipation, Bass was just one of many black men looking for work.

“Right after the Civil War, being a cowboy was one of the few jobs open to men of color who wanted to not serve as elevator operators or delivery boys or other similar occupations,” says William Loren Katz, a scholar of African-American history.

The Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Chickasaw tribes had been forcibly moved from their homelands to "Indian Territory" where they governed themselves, but the federal government was responsible for rounding up the lawless element hiding out there, thousands of thieves, murderers and fugitives.

The call went out to hire 200 deputies for the job, and Bass Reeves fit the profile. Strong, steady, 6-foot-2, with a deep voice and commanding presence, he was appointed the first African-American lawman west of the Mississippi. U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves By all accounts, he was one of the best, serving for more than 30-years in relentless pursuit of lawbreakers. The Oklahoma City Weekly Times-Journal reported,

“Reeves was never known to show the slightest excitement, under any circumstance. He does not know what fear is.”

U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves By all accounts, he was one of the best, serving for more than 30-years in relentless pursuit of lawbreakers. The Oklahoma City Weekly Times-Journal reported,

“Reeves was never known to show the slightest excitement, under any circumstance. He does not know what fear is.”

True to the mythical code of the West, Bass Reeves never drew his gun first. Though many outlaws aimed to shoot him, their bullets always missed. He was never even grazed by a bullet. Reeves admitted he shot and killed 14 men, but all in self-defense.

He's credited with bringing in 3,000 outlaws alive. More than once, showing up at the District Courthouse in Fort Smith with ten or more prisoners in tow.

From the “Court Notes” of the July 31, 1885, Fort Smith Weekly Elevator: “Deputy Bass Reeves came in same evening with eleven prisoners, as follows: Thomas Post, one Walaska, and Wm. Gibson, assault with intent to kill; Arthur Copiah, Abe Lincoln, Miss Adeline Grayson and Sally Copiah, alias Long Sally, introducing whiskey in Indian country; J.F. Adams, Jake Island, Andy Alton and one Smith, larceny.”

Though he couldn't read or write, Bass Reeves always knew which arrest warrant matched his man, and he used his brains, as well as his brawn and firepower to enforce the law. He often wore disguises to catch criminals unaware, and that may be the first clue that connected Bass with the famous "masked man."

He rode a large light gray horse and gave out silver dollars as a calling card, similar to the Lone Ranger's trademark silver bullets.

At least one biographer says the deputy marshal at times worked with a Native American partner tracking criminals. And like the Lone Ranger, he demonstrated an unshakable moral compass, even arresting his own son on a murder charge, after which the son was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. So far, historians have not proven the Lone Ranger was based on the exploits of Bass Reeves, but the most convincing piece of evidence seems to be that many of the prisoners he captured and turned into authorities at Fort Smith, went to serve their jail sentences in Detroit, the city where George Trendle and Fran Striker created the character of the Lone Ranger.

So far, historians have not proven the Lone Ranger was based on the exploits of Bass Reeves, but the most convincing piece of evidence seems to be that many of the prisoners he captured and turned into authorities at Fort Smith, went to serve their jail sentences in Detroit, the city where George Trendle and Fran Striker created the character of the Lone Ranger.

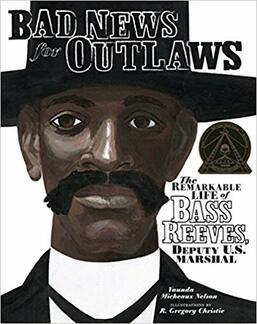

A children's biography Bad News for Outlaws: The Remarkable Life of Bass Reeves, Deputy U.S. Marshal , won the 2010 Coretta Scott King Award. It was written by Vaunda Micheaux Nelson and illustrated by R. Gregory Christie .

One reviewer on Goodreads says, " This is a children's book, but still very informative." Because, of course, most children's books are not informative. (heavy sigh)

For more reading on the topic, check out Gary Paulson's historical novel for teens called

the Legend of Bass Reeves: Being the True and Fictional Account of the Most Valiant Marshal in the West

. Publishers Weekly called it a "

compelling fictionalized biography...Effectively conveying Reeve's thoughts and emotions, the author shapes an articulate, well-deserved tribute to this unsung hero.

For more reading on the topic, check out Gary Paulson's historical novel for teens called

the Legend of Bass Reeves: Being the True and Fictional Account of the Most Valiant Marshal in the West

. Publishers Weekly called it a "

compelling fictionalized biography...Effectively conveying Reeve's thoughts and emotions, the author shapes an articulate, well-deserved tribute to this unsung hero.

Sources:

https://blackdoctor.org/482030/this-week-in-black-history-the-real-lone-ranger-was-a-black/

https://www.history.com/news/bass-reeves-real-lone-ranger-a-black-man

On Saturday night when they went to town, these men couldn't stay in hotels or eat in restaurants. I'm not sure if they could drink and play cards in the saloons, but during the workweek, their skill with a horse, a rope and a gun, could gain them a level of respect.

Black cowboys at the "Negro State Fair" in Bonham, Texas, in 1913, photo courtesy Texas State Historical Association. During the most lawless decades of the wild west, at least 25 (probably more) African American men served as deputy U.S. Marshals. There's some evidence to suggest that one of those rough-riding, straight-shooting black lawmen formed the basis for the iconic Lone Ranger.

Black cowboys at the "Negro State Fair" in Bonham, Texas, in 1913, photo courtesy Texas State Historical Association. During the most lawless decades of the wild west, at least 25 (probably more) African American men served as deputy U.S. Marshals. There's some evidence to suggest that one of those rough-riding, straight-shooting black lawmen formed the basis for the iconic Lone Ranger. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves grew famous during his 30-years pursuing and arresting bandits and murders throughout Indian Territory in the late 19th Century. And the former slave has some distinct resemblances to Lone Ranger of radio, comic book, TV and movies.

Bass was born a slave in Arkansas in 1883, and was taken to Texas his owner William Reeves as an 8-year-old boy. When the Civil War broke out, Reeves' son joined the Confederate Army and took Bass with him to the front lines as a servant.

U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves Before the war's end, Bass escaped, heading west to what was then called Indian Territory and now the State of Oklahoma. Historians say there he learned horsemanship and tracking skills from Native Americans and also became handy with Colt 45 and a rifle. After emancipation, Bass was just one of many black men looking for work.

U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves Before the war's end, Bass escaped, heading west to what was then called Indian Territory and now the State of Oklahoma. Historians say there he learned horsemanship and tracking skills from Native Americans and also became handy with Colt 45 and a rifle. After emancipation, Bass was just one of many black men looking for work.“Right after the Civil War, being a cowboy was one of the few jobs open to men of color who wanted to not serve as elevator operators or delivery boys or other similar occupations,” says William Loren Katz, a scholar of African-American history.

The Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Chickasaw tribes had been forcibly moved from their homelands to "Indian Territory" where they governed themselves, but the federal government was responsible for rounding up the lawless element hiding out there, thousands of thieves, murderers and fugitives.

The call went out to hire 200 deputies for the job, and Bass Reeves fit the profile. Strong, steady, 6-foot-2, with a deep voice and commanding presence, he was appointed the first African-American lawman west of the Mississippi.

U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves By all accounts, he was one of the best, serving for more than 30-years in relentless pursuit of lawbreakers. The Oklahoma City Weekly Times-Journal reported,

“Reeves was never known to show the slightest excitement, under any circumstance. He does not know what fear is.”

U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves By all accounts, he was one of the best, serving for more than 30-years in relentless pursuit of lawbreakers. The Oklahoma City Weekly Times-Journal reported,

“Reeves was never known to show the slightest excitement, under any circumstance. He does not know what fear is.”

True to the mythical code of the West, Bass Reeves never drew his gun first. Though many outlaws aimed to shoot him, their bullets always missed. He was never even grazed by a bullet. Reeves admitted he shot and killed 14 men, but all in self-defense.

He's credited with bringing in 3,000 outlaws alive. More than once, showing up at the District Courthouse in Fort Smith with ten or more prisoners in tow.

From the “Court Notes” of the July 31, 1885, Fort Smith Weekly Elevator: “Deputy Bass Reeves came in same evening with eleven prisoners, as follows: Thomas Post, one Walaska, and Wm. Gibson, assault with intent to kill; Arthur Copiah, Abe Lincoln, Miss Adeline Grayson and Sally Copiah, alias Long Sally, introducing whiskey in Indian country; J.F. Adams, Jake Island, Andy Alton and one Smith, larceny.”

Though he couldn't read or write, Bass Reeves always knew which arrest warrant matched his man, and he used his brains, as well as his brawn and firepower to enforce the law. He often wore disguises to catch criminals unaware, and that may be the first clue that connected Bass with the famous "masked man."

He rode a large light gray horse and gave out silver dollars as a calling card, similar to the Lone Ranger's trademark silver bullets.

At least one biographer says the deputy marshal at times worked with a Native American partner tracking criminals. And like the Lone Ranger, he demonstrated an unshakable moral compass, even arresting his own son on a murder charge, after which the son was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

So far, historians have not proven the Lone Ranger was based on the exploits of Bass Reeves, but the most convincing piece of evidence seems to be that many of the prisoners he captured and turned into authorities at Fort Smith, went to serve their jail sentences in Detroit, the city where George Trendle and Fran Striker created the character of the Lone Ranger.

So far, historians have not proven the Lone Ranger was based on the exploits of Bass Reeves, but the most convincing piece of evidence seems to be that many of the prisoners he captured and turned into authorities at Fort Smith, went to serve their jail sentences in Detroit, the city where George Trendle and Fran Striker created the character of the Lone Ranger.

A children's biography Bad News for Outlaws: The Remarkable Life of Bass Reeves, Deputy U.S. Marshal , won the 2010 Coretta Scott King Award. It was written by Vaunda Micheaux Nelson and illustrated by R. Gregory Christie .

One reviewer on Goodreads says, " This is a children's book, but still very informative." Because, of course, most children's books are not informative. (heavy sigh)

For more reading on the topic, check out Gary Paulson's historical novel for teens called

the Legend of Bass Reeves: Being the True and Fictional Account of the Most Valiant Marshal in the West

. Publishers Weekly called it a "

compelling fictionalized biography...Effectively conveying Reeve's thoughts and emotions, the author shapes an articulate, well-deserved tribute to this unsung hero.

For more reading on the topic, check out Gary Paulson's historical novel for teens called

the Legend of Bass Reeves: Being the True and Fictional Account of the Most Valiant Marshal in the West

. Publishers Weekly called it a "

compelling fictionalized biography...Effectively conveying Reeve's thoughts and emotions, the author shapes an articulate, well-deserved tribute to this unsung hero.

Sources:

https://blackdoctor.org/482030/this-week-in-black-history-the-real-lone-ranger-was-a-black/

https://www.history.com/news/bass-reeves-real-lone-ranger-a-black-man

Published on February 11, 2019 13:45

January 28, 2019

Human Dynamo Mae Jemison

The first African-American woman in space set her eyes on the stars as a child growing up on the south side of Chicago. She has not changed her view since.

The first African-American woman in space set her eyes on the stars as a child growing up on the south side of Chicago. She has not changed her view since.Her story may set your eyes on the stars as well.

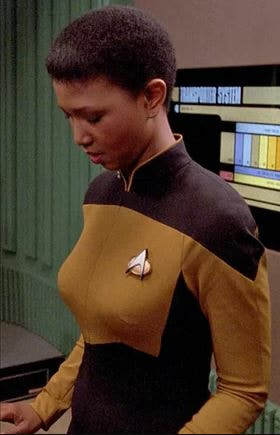

Mae Jemison went from being a fan of the original Star Trek, to appearing in the movie Star Trek: The Next Generation.

From earning a chemical engineering degree at Stanford to getting her medical degree at Cornell.

From practicing medicine in a Cambodian refugee camp, to orbiting the earth in a space shuttle.

Mae Jemison went from being the first African-American Woman in space to an entrepreneur set on developing the capability to send people like you and me to another star.

Oh, and resolve climate change while she's at it.

“Capabilities—notice that I didn’t say a launch date?” Dr. Jamison told qz.com. “Why is that important? Because all the capabilities that are required to go beyond our solar system are the very same things that we need to survive as a species on this starship [earth]. What’s the main capability we need? Sustainability.”

It seems rather than dreaming of possibilities, Mae Jemison has always believed in done deals. As a young girl during the heyday of the American space program, she closely followed details of the Gemini, Mercury and Apollo programs.

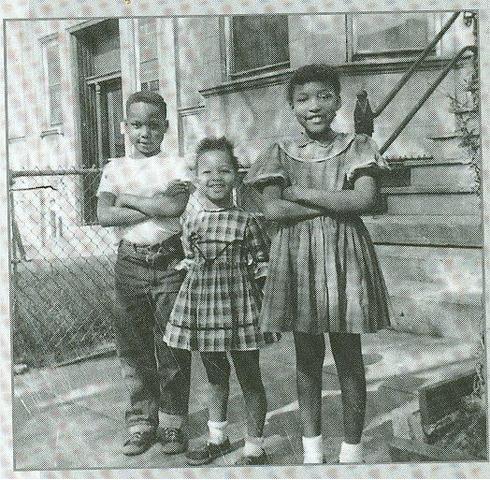

"I always assumed I would go into space," Mae says. "Not necessarily as an astronaut; I thought because we were on the moon when I was 11 or 12 years old, that we would be going to Mars—I'd be going to work on Mars as a scientist." (Below, Mae at center, her brother Ricky and sister Ada Sue)

Mae's kindergarten teacher suggested she consider being a nurse. Mae put her hands on her hips and insisted, no, she'd be a scientist.

Mae's kindergarten teacher suggested she consider being a nurse. Mae put her hands on her hips and insisted, no, she'd be a scientist."And that's despite the fact that there were no women, and it was all white males—and in fact, I used to always worry, believe it or not as a little girl, I was like: What would aliens think of humans? You know, these are the only humans?"

Many years later, after earning her M.D., working in the Peace Corps and taking up a general medical practice in Los Angles, Mae remembered her childhood plans.

“I still wanted to go into space. So I applied. Picked up the phone. I called down to Johnson space center I said I would like an application to be an astronaut. They didn’t laugh. I turned in the application."

“I still wanted to go into space. So I applied. Picked up the phone. I called down to Johnson space center I said I would like an application to be an astronaut. They didn’t laugh. I turned in the application."

She was accepted, one of fifteen astronaut candidates in 1987, and completed training the next year.

"I didn’t even think about the fact of whether I would be the first African-American woman in space or anything like that…it didn’t even cross my mind. I wanted to go into space. I couldn’t care if there had been a thousand people in space before me or whether there had been none. I wanted to go.”

September 12, 1992, the space shuttle Endeavour launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida and Mae Jemison was strapped into a seat on board.

September 12, 1992, the space shuttle Endeavour launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida and Mae Jemison was strapped into a seat on board.She served as the science mission specialist on the cooperative venture with Japan, doing experiments in life and material sciences, including bone cell research.

"I felt like I belonged right there in space," Mae says. "I realized I would feel comfortable anywhere in the universe — because I belonged to and was a part of it, as much as any star, planet, asteroid, comet, or nebula."

These days Mae Jemison works to ramp up enthusiasm for travel beyond our solar system and wants the general public to be more involved than they were in the days of the Apollo program's race to the moon.

These days Mae Jemison works to ramp up enthusiasm for travel beyond our solar system and wants the general public to be more involved than they were in the days of the Apollo program's race to the moon.To that end, she's founded The Earth We Share , an international science camp to increase middle school and secondary school student’s science literacy and problem solving skills. "Science literacy is not about people becoming professional scientists, but rather being able to read an article in the newspaper about the health, the environment and figure out how to vote responsibly on it."

In addition, with seed money from the federal government, Dr. Jemison started

The 100-Year Starship to encourage the basic research necessary for sending humans to another star. Jemison and other scientists working to come up with perpetual, clean energy for interstellar travel believe their work could provide breakthroughs to deal with climate change here on earth.

Sources:

https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physic...

https://www.pbs.org/video/secret-life...

https://qz.com/1159940/mae-jemisons-1...

http://teacher.scholastic.com/space/m...

Published on January 28, 2019 09:43

January 9, 2019

Here's How Resilience Rises from Heartbreak and Shapes the Supreme Court

My newest book launched yesterday, giving me a little flutter of excitement as I scrambled my egg for breakfast, pretended to work, but mainly checked twitter and Facebook. Even at the grocery, I levitated a bit pushing my cart through the produce section.

My newest book launched yesterday, giving me a little flutter of excitement as I scrambled my egg for breakfast, pretended to work, but mainly checked twitter and Facebook. Even at the grocery, I levitated a bit pushing my cart through the produce section.But at the end of the day, the thrill of pub date always falls short of the high I get when I discover a great story, dig for the details and choose the right structure and words to tell it. That's what I love.

Of course, I'm incredibly grateful and proud of the book on the shelf. And it's outright awesome to hear from readers. But a book launch doesn't happen every day. Me, sitting here writing, that's what happens everyday. And when I write a story like the following, my brain sparks, my blood rushes and I might as well be flying. It feels that thrilling.

So please, read on.

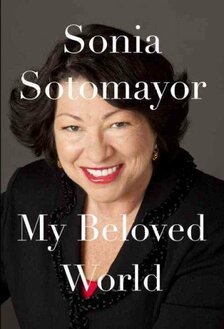

One little fact I discovered by accident started this story. I happened to read that

the mother of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor served in the Women's Army Corps (WAC) during World War II.

Celina Sotomayor with her daughter, Judge Sonia Sotomayor. White House photo. Of course, that caught my interest, due to my latest book about the origins of the WAC in the 1940s.

Celina Sotomayor with her daughter, Judge Sonia Sotomayor. White House photo. Of course, that caught my interest, due to my latest book about the origins of the WAC in the 1940s.My search for more information on Celina Sotomayor's military service turned up other information that completely took over my focus. For I'd found the extraordinary story of heartbreak and resilience that helped shape the first Latinx on our country's highest court.

But let's begin with Celina Baez's enlistment in the WAC. in fled extreme poverty in Puerto Rico to join the WAC in 1944. Like many soldiers during WWII, she lied about her age to enlist at 17. She spoke little English and didn't know a soul in Georgia where she reported for basic training.

Celia brought with her a fervor for the value of education as a stepping-stone to improving one's circumstances. Possibly stemming from the way her parents protected the one pencil the family possessed, divvying its use between their five children.

Celina didn't let a lack of school supplies impede her academics. She studied by playing teacher to a number of trees behind her home, pointing at each with a stick and calling them by name to recite her lessons. This, in a country were the literacy rate stood at 39-percent and families earned an average of $200 per year, adjusted for inflation that's about $3590.

But Celina didn't earn her high school diploma after her mother died and her father abandoned the family. She was raised by an older sister until joining the WAC at a time when few women of color felt welcome in the U.S. Army. There she trained to become a telephone operator.

When the Senate confirmed Celina's daughter as a Supreme Court Justice in 2009, it surely proved the American dream had come true for Celina.

But every story has its conflicts and challenges, its dark night of the soul, and so does Celina's.

After the war, Celina fell in love with a young Puerto Rican immigrant employed as a welder, Juan Luis Sotomayor.

After the war, Celina fell in love with a young Puerto Rican immigrant employed as a welder, Juan Luis Sotomayor.Juan came from a warm extended family that gathered for feasting, dominoes, singing and dancing. He wrote poetry, cooked fabulous food and knew how to make the ordinary fun.

The extended Sotomayor family, photo courtesy NPR. After Celina and Juan married, she continued her education, earning a high school equivalency certificate. In 1954, she and Juan welcomed little Sonia and three years later a son, Juan, Jr.

The extended Sotomayor family, photo courtesy NPR. After Celina and Juan married, she continued her education, earning a high school equivalency certificate. In 1954, she and Juan welcomed little Sonia and three years later a son, Juan, Jr.  In her early marriage, Celina worked at Prospect Hospital in the South Bronx as a telephone operator, then turned her studies to the medical field becoming a Licensed Practical Nurse.

In her early marriage, Celina worked at Prospect Hospital in the South Bronx as a telephone operator, then turned her studies to the medical field becoming a Licensed Practical Nurse.The Sotomayor's happy life started to crumble when her husband began to drink heavily, and her young family fell victim to the disease of alcoholism. Celina and Juan started to fight, loudly and often. Tension filled their home. Work became a refuge for Celina as she signed up for night and weekend shifts at the hospital.

Young Sonia didn't understand how addiction was tearing apart her family, nor why her mother seemed cool and distant, while her father was fun to be around. She blamed her mother for her father's alcoholism.

Celina, daughter Sonia and husband Juan. Undated photo provided by the White House. When Sonia was 9 and Juan, Jr. 6, their father died of a heart attack, leaving Celina with no savings. She went to work six days a week, arriving home to make her children dinner, then retreating behind the closed doors of her bedroom to cry out her grief.

Celina, daughter Sonia and husband Juan. Undated photo provided by the White House. When Sonia was 9 and Juan, Jr. 6, their father died of a heart attack, leaving Celina with no savings. She went to work six days a week, arriving home to make her children dinner, then retreating behind the closed doors of her bedroom to cry out her grief.She mourned the death of her husband, her marriage and loss of financial stability.

And she was grief-stricken over all that she'd lost to alcoholism years before, the wonderful man she'd fallen in love with and the life they'd dreamed of together.

Celina fell into depression and months passed before she gathered herself together and rose from her grief to nurture her children and supervise their education, which now seemed more important than ever.

She sacrificed and saved to keep her children in private school and purchased the only set of Encyclopedia Britannica in their Bronx housing project. Her son Juan remembers studying for hours at the kitchen table. "We studied when we came home, it was natural and we enjoyed it. There was never any negative energy about it because Mom used to say, 'Just do the best you can'."

Celina went back to school herself, when Sonia was in high school. She studied with her teens at the kitchen table, pursuing a dream. At 46 she got her degree and became a registered nurse.

Celina went back to school herself, when Sonia was in high school. She studied with her teens at the kitchen table, pursuing a dream. At 46 she got her degree and became a registered nurse.During all these years, her daughter Sonia had not come to terms with her feelings about her mother and the troubles the family went through in her early years. In the autobiography she published after joining the Supreme Court, Sonia wrote, "though my mother and I shared the same bed ... she might as well have been a log, lying there with her back to me."

"It wasn't until I began to write this book, nearly fifty years after the events of that sad year, that I came to a truer understanding of my mother's grief," she wrote.

"It was only when I had the strength and purpose to talk about the cold expanse between us that she confessed her emotional limitations in a way that called me to forgiveness."

Showing affection didn't come naturally to Celina who'd been an orphan from age 9 and lived through a contentious marriage. She told her daughter, "'How should I know these things, Sonia? Whoever showed me how to be warm when I was young?'"

Sonia had paid tribute to Celina the day President Barack Obama had chosen her as a nominee for the Supreme Court. “I have often said that I am all I am because of her, and I am only half the woman she is.” Sonia said before the president and a national television audience. “I thank you for all that you have given me and continue to give me.”

Understandably proud of both her children, Celina says she expected them to do well, "but I never envisioned them becoming what they are."

Her son earned his medical degree from New York University and owns a private practice specializing in allergy and asthma diagnostics.

Celina retired in the early 1990s, though she continued for many years using her nursing skills to aide neighbors in her apartment complex, on call for whoever was sick and rang the doorbell. One neighbor says Celina even “removed my cat’s stitches.”

Celina is now retired in South Florida with her second husband Omar Lopez.

I hope you enjoyed this story as much as I did. Let me know what you think in the comment section below. I've checked out the audio version of "My Beloved World," and from my local library and hope I can get to it before it's due.

Sources: https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/28/us/politics/28mother.html

https://www.npr.org/2013/01/12/167042458/sotomayor-opens-up-about-childhood-marriage-in-beloved-world

Published on January 09, 2019 16:20

January 8, 2019

How Black Women in the U.S. Army Helped Change the Course of WWII

Standing Up Against Hate

debuts today! It's the story of how black women in the U.S. Army changed the course of WWII. It's an honor and a privilege to tell the stories of these courageous women. Here's a sample of feedback I've gotten on the book.

Standing Up Against Hate

debuts today! It's the story of how black women in the U.S. Army changed the course of WWII. It's an honor and a privilege to tell the stories of these courageous women. Here's a sample of feedback I've gotten on the book.★ Starred Review, School Library Connection:

"A nonfiction writer for youth audiences, Farrell settles in to explain with depth and precision the fight black women faced both in and out of the military as World War II surged. Focused specifically on black women in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), the book profiles several key figures, including Major Charity Adams who commanded the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion.

"In addition to the deft writing, images are presented every few pages that reveal a score of brave women who persevered despite suffering discrimination. The women had to proclaim their equality in the face of segregation in the mess hall and in dispatching the unit overseas.

"The text also details how some servicewomen were jailed for disobeying orders or even beaten by civilians while wearing their uniforms. Organized chronologically, the text is accessible for middle school and high school historians who are intrigued by institutional racism or women in the military for research. It profiles milestones in the 6888th’s preparation and deployment, providing a well-researched understanding of the time period for black women in the military.

"The book is a gem that profiles an underrepresented narrative in American history."

Available at the links below or your favorite bookstore.

Barnes & Noble Amazon

Barnes & Noble Amazon

Published on January 08, 2019 00:00

January 4, 2019

Some Context for the New Faces in Congress

1st Lieutenant Dovey Johnson Watching record numbers of women sworn into the U.S. Congress, I couldn't help but think of the bitter congressional debate during World War II about establishing the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps. The controversy was really about where women did or didn't belong.

1st Lieutenant Dovey Johnson Watching record numbers of women sworn into the U.S. Congress, I couldn't help but think of the bitter congressional debate during World War II about establishing the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps. The controversy was really about where women did or didn't belong."This war is not teas, dances, card parties and amusements," Congressman Clare Eugene Hoffman of Michigan said. "You take a poll of the honest-to-goodness women at home, the women who have families, the women who sew on the buttons, do the cooking, mend the clothing, do the washing, and you will find there is where they want to stay—in the homes.”

Apparently, 150,000 women did not want to stay at home, which is how many volunteered for army service during WWII. One of those was Dovey Johnson of Charlotte, North Carolina, one of the first African American woman commissioned as a WAAC officer. Read more about Dovey in Standing Up Against Hate. (Pre-order here.) The book comes out January 8th. Dovey worked as an assistant to Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, who was the only African American in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's cabinet. When Congress approved the WAAC, Dr. Bethune demanded that black women, not only be allowed to enlist, but to be trained as officers right along beside white women.

At first, Dr. Bethune's logic fell on deaf ears, but she convinced Eleanor Roosevelt that black women deserved equal opportunity, and the First Lady convinced her husband.

Dr. Bethune had long been a family friend, but when Dovey went to work for her, she had no idea the plan was for her to join the army!

Here's an excerpt of an interview with Dovey Johnson Roundtree seven decades later. She talks about rumors the women of the WAAC were meant to be "companions" for the soldiers. This interview was conducted by the National Visionary Leader Project in 2009. You can see the full interview here.

Teachers: Check out this lesson plan you can use with students to look at gender roles in America in the 1940s and how the idea of women serving in the military threatened prevailing attitudes about the duties of women.

Published on January 04, 2019 00:00

December 18, 2018

What Propelled a Sharecropper Girl to the Top Ranks of the Army?

If only we could bottle it.

If only we could bottle it.She grew up working in the tobacco fields of Wake County, North Carolina. Her parents had a large family, ten children, because sharecropping required many hands and all-consuming labor.

How did Clara Leach make the leap from the Jim Crow south to Brigadier General in the U.S. Army?

She wrote the story of her life after retirement to set the record straight. "I was increasingly encountering people who assumed that I was successful because I was born with a “silver spoon” in my mouth or I just “got lucky.”

At age five Clara cooked and tended younger siblings in a house with no electricity or running water, while her parents and older siblings grew and harvested tobacco for a white landowner.

Soon Clara graduated to field work. That included planting, hoeing, pulling weeds, walking the rows "topping" off the buds to stimulate growth, and picking worms off the leaves and squishing them.

"Growing tobacco...is a very difficult crop...labor intensive," Clara says. "So my father and mother had ten children, and we were all employed full time on that farm in tobacco."

Photo: The daughter of an African American sharecropper at work in a tobacco field in Wake County, North Carolina. Credit: Dorothea Lange, July 1939.

First ingredientClara's parents believed in education as well as hard work. And though she missed a lot of school due to farm work, Clara skipped two grades and graduated at sixteen, salutatorian of her class.

in the elixir for success:

Learn to work hard.

The painful experience of prejudice at her segregated school in Wake County launched the attitude that would carry Clara from the soil of North Carolina to the halls of the Pentagon.

Segregated School, Illinois, 1937.

"Many members of the African-American community considered dark skin ugly. Unattractive. Undesirable. That message came across loud and clear in terms of which students were favored by teachers, and by other students," Clara says. "When I raised my hand, the teacher would never call on me."

Segregated School, Illinois, 1937.

"Many members of the African-American community considered dark skin ugly. Unattractive. Undesirable. That message came across loud and clear in terms of which students were favored by teachers, and by other students," Clara says. "When I raised my hand, the teacher would never call on me.""Instead, a kid with straight hair and fair skin always got picked. Some of them were really smart, but so was I. It was all part of a warped value system that some black people still embrace today-the closer you are to being white, the better off and more beautiful you are."