Mary Cronk Farrell's Blog, page 8

December 5, 2017

Delicious December Salad: Golden Beets, Pomegranate Seeds & Arugula

Here's my new seasonal salad. Honestly, I love it so much I've been eating it every day.

Here's my new seasonal salad. Honestly, I love it so much I've been eating it every day.Salad

8-10 oz of baby field greens, half arugula

1 medium roasted golden beet, cut into chunks (Here's how I roast beets.)

2 tangerines, peeled and separated

1/2 cup pomegranate seeds

Use your favorite citrus vinaigrette dressing, or the simple one I whipped up. It makes enough dressing for at least two salads.

Dressing

4 oz Trader Joe's Orange Muscat Champagne Vinegar

4 oz Extra Virgin Olive Oil

garlic, salt and pepper to taste.

Published on December 05, 2017 14:57

Rocking the Second Half of Life

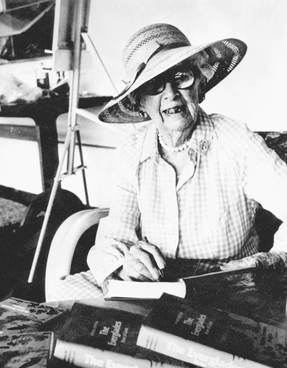

Marjory Stoneman Douglas earned her place in history for helping preserve the Florida Everglades.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas earned her place in history for helping preserve the Florida Everglades.

She did it all in the second half of life.

At first glance Marjory appears an unlikely heroine. She began her journalism career as the society reporter for the Miami Herald and later published short stories and novels.

She rarely went out for a picnic, let alone visited the crocodile invested Everglades, saying it was "too buggy, too wet, and too generally inhospitable.... I know it’s out there, and I know it’s important....

There are no other Everglades in the world."

South Florida land developers considered the Everglades a useless swamp just waiting for them to turn it into shopping malls and subdivision.

Marjory wrote stories set in South Florida and vividly described the natural world. She was writing a novel 1941 when an editor asked her to write a non-fiction book addressing threats to the Everglades and she agreed.

Marjory wrote stories set in South Florida and vividly described the natural world. She was writing a novel 1941 when an editor asked her to write a non-fiction book addressing threats to the Everglades and she agreed.Scientists warned if the area wasn't protected, soon all wildlife there would be extinct.

They are unique...in the simplicity, the diversity, the related harmony of the forms of life they enclose," wrote Marjory.

They are unique...in the simplicity, the diversity, the related harmony of the forms of life they enclose," wrote Marjory.

"The miracle of the light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass and of water, shining and slow-moving below, the grass and water that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades of Florida."

At age 57, Marjory published The Everglades: River of Grass. It hit the shelves in November 1947 and sold out before Christmas. The impact of the book is sometimes compared to Rachel Carson's Silent Spring.

And it launched Marjory into her role as an environmental activist, which took up the next 51-years of her life.

She founded Friends of the Everglades, wrote more books on the subject and fought developers, the Army Corp of Engineers, and anyone else who threatened the unique species and habitat of South Florida.

"[She's a] tiny, slim, perfectly dressed, utterly ferocious grande dame who can make a redneck shake in his boots," said Assistant Secretary of the Interior Nathaniel Reed. "When Marjory bites you, you bleed."

Marjory's wisdom is crucial today as we face climate change. She said. "I would be very sad if I had not fought. I'd have a guilty conscience if I had been here and watched all this happen to the environment and not been on the right side."

Marjory's wisdom is crucial today as we face climate change. She said. "I would be very sad if I had not fought. I'd have a guilty conscience if I had been here and watched all this happen to the environment and not been on the right side."In 1990, Marjory published her autobiography, Voice of the River beginning with the admission "the hardest thing is to tell the truth about oneself."

And ending with the advice, "life should be lived so vividly and so intensely that thoughts of another life, or a longer life, are not necessary."

Marjory lived “my own life in my own way,” for 108 years. Her spirit gives me hope and challenges me live vividly and intensely.

Published on December 05, 2017 14:27

November 6, 2017

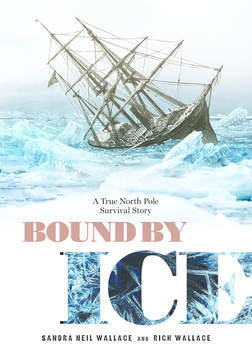

Bound By Ice: Book Giveaway!

Welcome Author Sandra Neil Wallace, here to talk about her new book, a story of discovery and courage. To enter for a free copy of Bound By Ice: A True North Pole Survival Story, see details below.

Some people are willing to die for what they believe in, including advancing humanity through discovery and science.

Some people are willing to die for what they believe in, including advancing humanity through discovery and science.

Ever since George W. De Long navigated through meandering fjords amid iceberg-filled waters off the coast of Greenland to rescue a failed trek to the Arctic, he knew he’d be back.

In 1873, no explorer had managed to reach the North Pole, but De Long learned valuable lessons from that rescue voyage.

1400 pounds of pemmican. CHECK

20 tons of coal. CHECK

40 pounds of lemon and orange peels to prevent scurvy. CHECK

36 sealskin caps. CHECK Six years later and now a Commander, George W. De Long was prepared. As thousands of spectators followed each stroke, he paddled toward the schooner that would take him farther into the Arctic than any explorer had gone before.

He bid his beloved wife Emma a tearful farewell, knowing that he might never see her again. He’d stocked and remodeled the ship he was about to board with the latest maps, engineering tools, and provisions. He’d hired an all-star crew.

The USS Jeannette was the best equipped schooner ever to search for the North Pole.

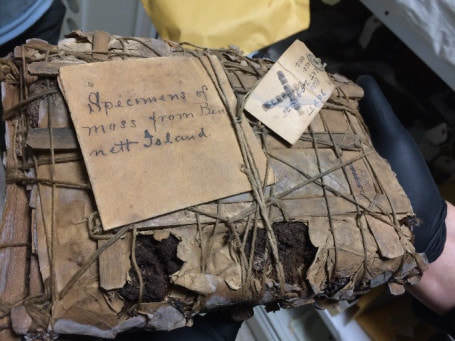

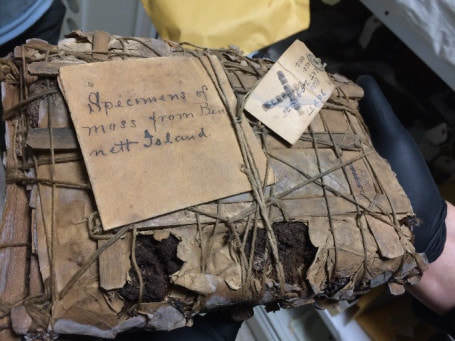

When we first started researching the Jeannette’s voyage to reach the pole I’d seen a gigantic hunk of moss gathered by the crew from an island they’d discovered, and now kept at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

When we first started researching the Jeannette’s voyage to reach the pole I’d seen a gigantic hunk of moss gathered by the crew from an island they’d discovered, and now kept at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

At Dartmouth College, Rich located an SOS note that De Long had tucked into a crevice in Siberia’s Lena Delta.

And then there was the abandoned pair of sealskin pantaloons belonging to a crew member named Louis P. Noros. Found on a drifting ice floe three years after the Jeannette sank, it inspired a famous Norwegian explorer named Fridtjof Nansen to build a ship that would nearly make it to the pole.

And we were determined to discover what the courage of these American, European, Asian, and Yup’ik explorers looked like. We found it in their journals, diaries, and testimonies. Co-Author Rich Wallace with log book from the USS Jeannette Despite having enough fuel, food, warm clothes, and hunting equipment, nothing could compensate for the sketchy science, faulty maps, and deadly wrong beliefs that De Long and his crew of 33 relied on for their 1879 voyage to the North Pole.

Co-Author Rich Wallace with log book from the USS Jeannette Despite having enough fuel, food, warm clothes, and hunting equipment, nothing could compensate for the sketchy science, faulty maps, and deadly wrong beliefs that De Long and his crew of 33 relied on for their 1879 voyage to the North Pole.

Arctic ice was not salt free, as they’d been led to believe, so drinking water became an immediate concern.

And there was no tropical sea once they reached the Arctic Ocean, as experts thought.

In fact, within two months of starting the voyage, they were bound by ice--trapped in the vice grip of an ice floe with nothing to do but drift, patching punctures made by the crashing ice and constantly pumping out water, hoping their ship wouldn’t split into smithereens. But it did! By then, they’d discovered new islands, flora and fauna, and taken hundreds of ice measurements.

Rushing to save their logbooks, research materials, and provisions from plunging to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, the crew managed to escape safely before the Jeannette went under.

Rushing to save their logbooks, research materials, and provisions from plunging to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, the crew managed to escape safely before the Jeannette went under.

As crew members trudged through 500 harrowing miles of snow and slush toward Siberia in hopes of being rescued, they never lost their humanity.

They showed kindness toward one another in the most extreme circumstances. Their focus became keeping each other alive.

They shared rations, carried their sick friends, and recorded the events of each day in journals, no matter how weak and starved they were. They wrote SOS notes and lugged the ship’s 45-pound logbooks to higher ground so future explorers could learn from their discoveries. And that’s exactly what happened.

They wrote SOS notes and lugged the ship’s 45-pound logbooks to higher ground so future explorers could learn from their discoveries. And that’s exactly what happened.

The ice measurements taken by De Long and his crew were transcribed by NOAA and are being used by scientists today to track climate change in the Arctic. And future explorers did reach the North Pole, of course, thanks to De Long and the Jeannette crew.

Through their notes and survivor stories, they also showed that saving lives is even more important than discovery.

Thank you, Sandra, for telling us about your new book. Click to learn more about

Sandra Neil Wallace and Rich Wallace.

To enter your name in the drawing for a copy of Bound By Ice you must be a resident of the United States and leave a comment below. The winner will be announced here November 15, 2018.

“We have a good crew, good food, and a good ship,

and I think we have the right kind of stuff to dare

all that man can do.”

--Commander George W. De Long

Some people are willing to die for what they believe in, including advancing humanity through discovery and science.

Some people are willing to die for what they believe in, including advancing humanity through discovery and science.Ever since George W. De Long navigated through meandering fjords amid iceberg-filled waters off the coast of Greenland to rescue a failed trek to the Arctic, he knew he’d be back.

In 1873, no explorer had managed to reach the North Pole, but De Long learned valuable lessons from that rescue voyage.

1400 pounds of pemmican. CHECK

20 tons of coal. CHECK

40 pounds of lemon and orange peels to prevent scurvy. CHECK

36 sealskin caps. CHECK Six years later and now a Commander, George W. De Long was prepared. As thousands of spectators followed each stroke, he paddled toward the schooner that would take him farther into the Arctic than any explorer had gone before.

He bid his beloved wife Emma a tearful farewell, knowing that he might never see her again. He’d stocked and remodeled the ship he was about to board with the latest maps, engineering tools, and provisions. He’d hired an all-star crew.

The USS Jeannette was the best equipped schooner ever to search for the North Pole.

When we first started researching the Jeannette’s voyage to reach the pole I’d seen a gigantic hunk of moss gathered by the crew from an island they’d discovered, and now kept at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

When we first started researching the Jeannette’s voyage to reach the pole I’d seen a gigantic hunk of moss gathered by the crew from an island they’d discovered, and now kept at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

At Dartmouth College, Rich located an SOS note that De Long had tucked into a crevice in Siberia’s Lena Delta.

And then there was the abandoned pair of sealskin pantaloons belonging to a crew member named Louis P. Noros. Found on a drifting ice floe three years after the Jeannette sank, it inspired a famous Norwegian explorer named Fridtjof Nansen to build a ship that would nearly make it to the pole.

We couldn’t believe that a headline-making voyage with such deep impacts on the future of the Arctic had been virtually forgotten.

We found it

in their journals, diaries,

and testimonies.

--Author Sandra Neil Wallace

And we were determined to discover what the courage of these American, European, Asian, and Yup’ik explorers looked like. We found it in their journals, diaries, and testimonies.

Co-Author Rich Wallace with log book from the USS Jeannette Despite having enough fuel, food, warm clothes, and hunting equipment, nothing could compensate for the sketchy science, faulty maps, and deadly wrong beliefs that De Long and his crew of 33 relied on for their 1879 voyage to the North Pole.

Co-Author Rich Wallace with log book from the USS Jeannette Despite having enough fuel, food, warm clothes, and hunting equipment, nothing could compensate for the sketchy science, faulty maps, and deadly wrong beliefs that De Long and his crew of 33 relied on for their 1879 voyage to the North Pole.Arctic ice was not salt free, as they’d been led to believe, so drinking water became an immediate concern.

And there was no tropical sea once they reached the Arctic Ocean, as experts thought.

In fact, within two months of starting the voyage, they were bound by ice--trapped in the vice grip of an ice floe with nothing to do but drift, patching punctures made by the crashing ice and constantly pumping out water, hoping their ship wouldn’t split into smithereens. But it did! By then, they’d discovered new islands, flora and fauna, and taken hundreds of ice measurements.

Rushing to save their logbooks, research materials, and provisions from plunging to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, the crew managed to escape safely before the Jeannette went under.

Rushing to save their logbooks, research materials, and provisions from plunging to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, the crew managed to escape safely before the Jeannette went under. “Thankful were we to make our beds on snow instead of beneath the sea.” –Jeannette Engineer George MelvilleSuddenly the voyage turned from a quest for the North Pole to a race for survival.

As crew members trudged through 500 harrowing miles of snow and slush toward Siberia in hopes of being rescued, they never lost their humanity.

They showed kindness toward one another in the most extreme circumstances. Their focus became keeping each other alive.

They shared rations, carried their sick friends, and recorded the events of each day in journals, no matter how weak and starved they were.

They wrote SOS notes and lugged the ship’s 45-pound logbooks to higher ground so future explorers could learn from their discoveries. And that’s exactly what happened.

They wrote SOS notes and lugged the ship’s 45-pound logbooks to higher ground so future explorers could learn from their discoveries. And that’s exactly what happened.The ice measurements taken by De Long and his crew were transcribed by NOAA and are being used by scientists today to track climate change in the Arctic. And future explorers did reach the North Pole, of course, thanks to De Long and the Jeannette crew.

Through their notes and survivor stories, they also showed that saving lives is even more important than discovery.

Thank you, Sandra, for telling us about your new book. Click to learn more about

Sandra Neil Wallace and Rich Wallace.

To enter your name in the drawing for a copy of Bound By Ice you must be a resident of the United States and leave a comment below. The winner will be announced here November 15, 2018.

Published on November 06, 2017 13:40

October 17, 2017

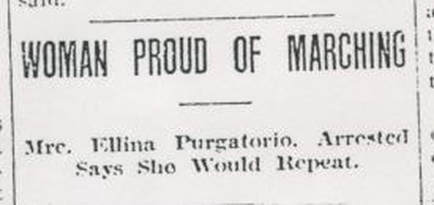

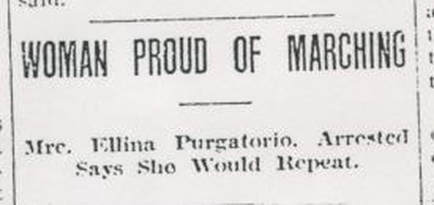

Kansas Women Turned March into Political Clout

Second grader LaVaun Smith heard a great uproar outside her school in southeast Kansas. She and the other students rushed to the door of their country school house to see the commotion.

They threw open the door that cold December day in 1921, and a rowdy parade of women filled the road beating on dish pans, wash pans and metal buckets with sticks and kitchen utensils. A number of the students spotted their mothers as the women converged on the mine across the road to confront strike-breakers, who had taken their husbands' coal mining jobs. The school kids' dads had struck the mines in Crawford and Cherokee County three months prior, but companies kept operations running with non-union workers, and the sheriff arrested labor leaders for violating a statewide strike injunction.

The school kids' dads had struck the mines in Crawford and Cherokee County three months prior, but companies kept operations running with non-union workers, and the sheriff arrested labor leaders for violating a statewide strike injunction.

With a harsh winter on the horizen coming, wives, mothers, and sisters of the mine workers decided to take things into their own hands. Gathering before dawn, December 12, they marched through the region, routing "scabs" at 63 different mines.

The throng of marching women, some pregnant and others carrying small children, grew from two-thousand to possibly six-thousand. For three days they completely shut down coal production in the region. One of the leaders, Mary Skubitz, had

One of the leaders, Mary Skubitz, had

immigrated from Slovenia as a child.

According to her son Joe, "Hunger drove most of those women. They just wanted something to eat and a house."

Mary spoke German, Italian, and Slovene, which allowed her to rally a broad spectrum of women in the mining camps. Fluent in English as well, she was persuasive with the mine bosses and strikebreakers.

Kansas Governor Henry Allen dispatched four companies of the Kansas National Guard, including a machine gun division to get the women back to their kitchens. The women, armed only with their pots, pans and red pepper spray, marched from mine to mine singing hymns and waving American flags. The first day there was little violence, but the following two days when large numbers of men joined the protest, strikebreakers were beaten and property vandalized, inflaming headlines across the nation.

The first day there was little violence, but the following two days when large numbers of men joined the protest, strikebreakers were beaten and property vandalized, inflaming headlines across the nation.

The New York Times declared them an Amazon Army...on the warpath... invading mines and scattering workers with pepper spray.

December 16, Sheriff Milt Gould arrested Mary and three other women, who spent one night in jail due a $750 bail.

Over the following month, the sheriff and his deputies hoped to make massive arrests, bystanders would not cooperate in naming names, and women protesters told deputies they could not recall who had marched beside them.

Deputies jailed 50-some men and women who participated in the action. And Crawford County District Judge Andrew Curran handed down fines to forty-nine protesters for disturbing the peace, unlawful assembly, and assault.

The marching women were characterized by the newspapers in one of two ways. Benjamin W. Goossen write in Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains (Autumn 2011), " either it was a laughable “Petticoat March ” of witless and misguided domestics, or the attack of a ferocious 'Amazon Army' that threatened to destroy traditional notions of women ’s role in society."  The Wichita Beacon described them as “a few women, peeking from behind windows, sometimes waving handkerchiefs and sometimes ‘making eyes’ at the soldiers."

The Wichita Beacon described them as “a few women, peeking from behind windows, sometimes waving handkerchiefs and sometimes ‘making eyes’ at the soldiers."

The Kansas City Kansan labed them “women terrorists,” who “clawed and used teeth” like “tigresses.”

Some of the women defended themselves in letters to the editors, and small groups of women continued to accost strikebreakers even after the strike was called off.

The following election season, (this was just two years after American women got the vote) the women who had tested their strength marching turned their energy to campaigning against the men who'd opposed them. Both Sheriff Gould, who had arrested dozens of marchers and Judge Curran, who had sentenced them were ousted from office.

They threw open the door that cold December day in 1921, and a rowdy parade of women filled the road beating on dish pans, wash pans and metal buckets with sticks and kitchen utensils. A number of the students spotted their mothers as the women converged on the mine across the road to confront strike-breakers, who had taken their husbands' coal mining jobs.

The school kids' dads had struck the mines in Crawford and Cherokee County three months prior, but companies kept operations running with non-union workers, and the sheriff arrested labor leaders for violating a statewide strike injunction.

The school kids' dads had struck the mines in Crawford and Cherokee County three months prior, but companies kept operations running with non-union workers, and the sheriff arrested labor leaders for violating a statewide strike injunction.With a harsh winter on the horizen coming, wives, mothers, and sisters of the mine workers decided to take things into their own hands. Gathering before dawn, December 12, they marched through the region, routing "scabs" at 63 different mines.

No fearOne marcher recorded in her diary, the women “rolled down to the [mine] pits like balls and the men ran like deers....There was absolutely no fear in these women’s hearts.”

in these

women’s hearts

The throng of marching women, some pregnant and others carrying small children, grew from two-thousand to possibly six-thousand. For three days they completely shut down coal production in the region.

One of the leaders, Mary Skubitz, had

One of the leaders, Mary Skubitz, had immigrated from Slovenia as a child.

According to her son Joe, "Hunger drove most of those women. They just wanted something to eat and a house."

Mary spoke German, Italian, and Slovene, which allowed her to rally a broad spectrum of women in the mining camps. Fluent in English as well, she was persuasive with the mine bosses and strikebreakers.

Kansas Governor Henry Allen dispatched four companies of the Kansas National Guard, including a machine gun division to get the women back to their kitchens. The women, armed only with their pots, pans and red pepper spray, marched from mine to mine singing hymns and waving American flags.

The first day there was little violence, but the following two days when large numbers of men joined the protest, strikebreakers were beaten and property vandalized, inflaming headlines across the nation.

The first day there was little violence, but the following two days when large numbers of men joined the protest, strikebreakers were beaten and property vandalized, inflaming headlines across the nation.The New York Times declared them an Amazon Army...on the warpath... invading mines and scattering workers with pepper spray.

December 16, Sheriff Milt Gould arrested Mary and three other women, who spent one night in jail due a $750 bail.

Over the following month, the sheriff and his deputies hoped to make massive arrests, bystanders would not cooperate in naming names, and women protesters told deputies they could not recall who had marched beside them.

Deputies jailed 50-some men and women who participated in the action. And Crawford County District Judge Andrew Curran handed down fines to forty-nine protesters for disturbing the peace, unlawful assembly, and assault.

The marching women were characterized by the newspapers in one of two ways. Benjamin W. Goossen write in Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains (Autumn 2011), " either it was a laughable “Petticoat March ” of witless and misguided domestics, or the attack of a ferocious 'Amazon Army' that threatened to destroy traditional notions of women ’s role in society."

The Wichita Beacon described them as “a few women, peeking from behind windows, sometimes waving handkerchiefs and sometimes ‘making eyes’ at the soldiers."

The Wichita Beacon described them as “a few women, peeking from behind windows, sometimes waving handkerchiefs and sometimes ‘making eyes’ at the soldiers." The Kansas City Kansan labed them “women terrorists,” who “clawed and used teeth” like “tigresses.”

Some of the women defended themselves in letters to the editors, and small groups of women continued to accost strikebreakers even after the strike was called off.

The following election season, (this was just two years after American women got the vote) the women who had tested their strength marching turned their energy to campaigning against the men who'd opposed them. Both Sheriff Gould, who had arrested dozens of marchers and Judge Curran, who had sentenced them were ousted from office.

Published on October 17, 2017 01:00

October 3, 2017

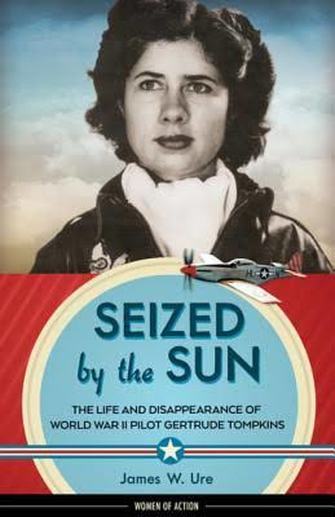

The Disappearance of Gertrude Tompkins

Courtesy WASP Archives, Texas Women's University Library. Author Jim Ure was writing a novel when a true story side-tracked him, the story of a woman's disappearance that has remained unsolved for more than seventy years.

Courtesy WASP Archives, Texas Women's University Library. Author Jim Ure was writing a novel when a true story side-tracked him, the story of a woman's disappearance that has remained unsolved for more than seventy years.His new book, Seized by the Sun tells how Gertrude Tompkins (left), a shy, awkward girl who stuttered, growing up to be one of only a handful of U.S. women test pilots during WWII.

Her job was to take new or repaired planes to the sky and put them through tight turns, stalls, dives and spins making sure they were safe.

Below: P-51 Mustang fighters. Gertrude was one of only 126 WASP pilots good enough to fly these fighter planes. Her first flight in a powerful P-51 cured the debilitating stutter that had plagued her since childhood.

It was later in the war, on a routine flight, that Gertrude disappeared while ferrying a factory-new plane a short distance between two airfields in California

It was later in the war, on a routine flight, that Gertrude disappeared while ferrying a factory-new plane a short distance between two airfields in California Author James Ure is on the blog today, telling us how he got hooked on the story.

Author Jim Ure In the summer of the 2000 I was doing some research for an idea I had about a novel. My writing success had come in non-fiction, but the illusive novel still beckoned.

Author Jim Ure In the summer of the 2000 I was doing some research for an idea I had about a novel. My writing success had come in non-fiction, but the illusive novel still beckoned. In this fictional piece I imagined a character who learned his mother had been a woman pilot in World War II and her crashed plane and her remains had just been discovered in a melting glacier in Montana.

I put a note on what I was doing on a Women’s Air Force Pilot user group on Yahoo. The result was unexpected.

I was contacted by the grand niece of Gertrude “Tommy” Tompkins. Laura Whittall-Scherfee, who lives near Sacramento, told me that of the 38 women killed in the WASP during World War II, her grand aunt was the only one still missing.

She was called, “The Other Amelia,” and a sort of cult had grown among the searchers who continue to look for her to this day. Laura and her husband Ken offered me access to the family records. Would I be interested?

Would I ever!

I’d always had a fascination for World War II aviation, and this was an enticement I couldn’t refuse.

I’d always had a fascination for World War II aviation, and this was an enticement I couldn’t refuse.

It took seventeen years of interviews, combing military files and reading private correspondence to finally give Tommy the fully-dimensional place in aviation history she deserved.

I was lucky to have conversations with a number of WASPs early in my research. Today only about 85 WASPs of the 1,175 who were in service during the war are still alive.

Tommy took off from Mines Air Field (now LAX) on October 26, 1944, and was expected to stay at the Army Air Force Base in Palm Springs that evening.

She was never seen again. Aircraft historian Pat Macha has conducted numerous searches over the years and no trace has ever turned up.

Below: A group of WASPs pray for luck before climbing into a BT-13 unpredictable and sometimes dangerous training plane. Avenger Field, Sweetwater, Texas, circa 1943.

Courtesy WASP Archives, Texas Women's University Library. The conclusion I have come to after all this time is that she probably crashed into Santa Monica Bay immediately after take-off.

Courtesy WASP Archives, Texas Women's University Library. The conclusion I have come to after all this time is that she probably crashed into Santa Monica Bay immediately after take-off. The results of searches of the bay and of the mountains and deserts on her presumed flight path are documented in Seized by the Sun. It’s a mystery yet to be solved, and there are men and women still searching for Tommy.

Thank you, Jim!

Learn more about Jim and his books at www.jimurebooks.com.

Above, WASPs with PT-19, the first plane usually flown in primary training. Women on far left in dark glasses is Gertrude “Tommy” Tompkins, according to Texas Women’s University Libraries WASP Archives.

Above, WASPs with PT-19, the first plane usually flown in primary training. Women on far left in dark glasses is Gertrude “Tommy” Tompkins, according to Texas Women’s University Libraries WASP Archives.

Published on October 03, 2017 00:00

September 11, 2017

One Tough Nurse From the Outback

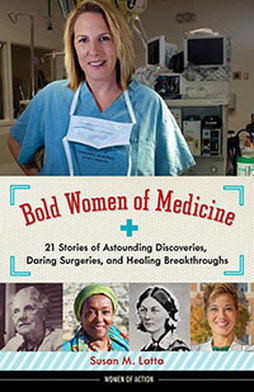

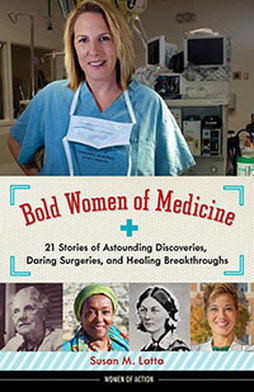

This week, welcome Author Susan Latta with the story of one trailblazing nurse featured in her new book

Bold Women of Medicine: 21 Stories of Astounding Discoveries, Daring Surgeries, and Healing Breakthroughs

.

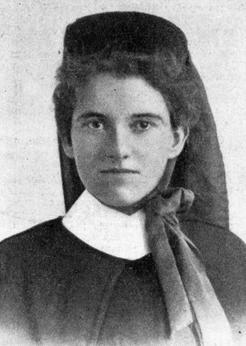

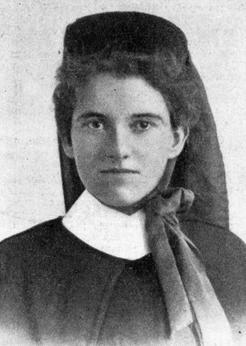

Nurse Elizabeth Kenny, circa 1915, courtesy Wikipedia commons Thank you, Susan!

Nurse Elizabeth Kenny, circa 1915, courtesy Wikipedia commons Thank you, Susan!

No one knows whether Elizabeth Kenny had any formal medical training or learned on-the-job, but that didn’t stop her.

She had a red cape and nurse’s jumper made and traveled through Australia’s wild bush land to serve anyone who needed help.

Born in Australia in 1880, at a time when girls were not to be brassy, stubborn, or opinionated. Elizabeth had no intention of following those rules.

I first heard about Elizabeth Kenny when my father had a stroke and was transferred to the Elizabeth Kenny Institute in Minneapolis for recovery. Prior to that, I knew of her in name only. Author Susan Latta I remember standing in a long line in the school gym waiting to receive my vaccination in the early 1960s, and had no idea how many people suffered after being stricken by polio.

Author Susan Latta I remember standing in a long line in the school gym waiting to receive my vaccination in the early 1960s, and had no idea how many people suffered after being stricken by polio.

Decades earlier Elizabeth Kenny had become famous for her treatment for polio, a dreadful virus that caused paralysis and death.

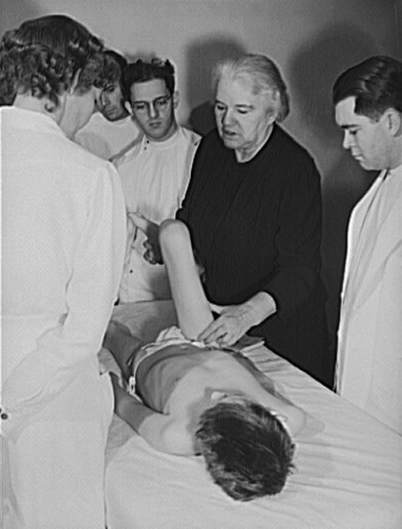

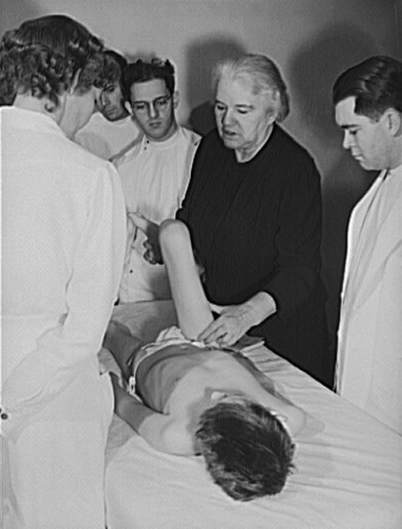

Below: Elisabeth Kenny demonstrating polio treatment to doctors and nurses at the Elizabeth Kenny Institute in Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1943. Library of Congress photo Elizabeth didn’t know it at the time but discovered her polio treatment one day in 1911.

Elizabeth didn’t know it at the time but discovered her polio treatment one day in 1911.

A frantic farmer called for help for his two-year-old daughter. Amy's arms and

legs were twisted tight with unbearable pain.

Elizabeth Kenny galloped away to send a telegram to her trusted doctor, Aeneas McDonnell. When he replied that it was polio, he said there was nothing to be done, and to do “the best with symptoms presenting themselves.”

"I knew the relaxing power of heat," Elizabeth said. "I filled a frying pan with salt, placed it over the fire, then poured it into a bag and applied it to the leg that was giving the most pain. After an anxious wait, I saw no relief followed the application. I then prepared a linseed meal poultice, but the weight of this seemed only to increase the pain.

"At last I tore a blanket made from soft Australian wool into suitable strips and wrung them out in boiling water. These I wrapped gently about the poor tortured muscles. The whimpering of the child ceased almost immediately, and after a few more applications her eyes closed slowly and she fell asleep.”

Amy recovered. But men in the medical field refused to accept Elizabeth's methods. In 1914, Elizabeth Kenny traveled to England to serve in WWI. The Australian Army Nursing Service gave her the title of “sister,” which had nothing to do with religion, instead meaning “senior nurse.” She became known as Sister Kenny.

In 1914, Elizabeth Kenny traveled to England to serve in WWI. The Australian Army Nursing Service gave her the title of “sister,” which had nothing to do with religion, instead meaning “senior nurse.” She became known as Sister Kenny.

After the war, she presented her methods to control the muscle spasms and re-educate the paralyzed limbs to packed rooms of medical men in Australia. Over and over they called her a quack nurse from the bush, and finally she had had enough. She sailed to America to prove her treatment.

After being turned away by doctors in New York and Chicago, she landed in Minnesota where a few doctors said her treatment did work. As word spread she gained nationwide support, even landing on a list of most admired women in America nine years running. The Elizabeth Kenny Institute opened in 1942, and still exists today as Courage Kenny, a facility for stroke and accident victims.

As word spread she gained nationwide support, even landing on a list of most admired women in America nine years running. The Elizabeth Kenny Institute opened in 1942, and still exists today as Courage Kenny, a facility for stroke and accident victims.

At right: A patient is treated in an Iron Lung circa 1960s. Photo courtesy U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Polio was eradicated in America when Albert Sabin’s live polio virus vaccine guaranteed immunity, just a few short years after Sister Kenny died in 1952.

Thank you, Susan! I'm excited to learn about the other ground-breaking medical women featured in your book, Bold Women of Medicine: 21 Stories of Astounding Discoveries, Daring Surgeries, and Healing Breakthroughs.

See more about the book and Author Susan Latta here...

Nurse Elizabeth Kenny, circa 1915, courtesy Wikipedia commons Thank you, Susan!

Nurse Elizabeth Kenny, circa 1915, courtesy Wikipedia commons Thank you, Susan!No one knows whether Elizabeth Kenny had any formal medical training or learned on-the-job, but that didn’t stop her.

She had a red cape and nurse’s jumper made and traveled through Australia’s wild bush land to serve anyone who needed help.

Born in Australia in 1880, at a time when girls were not to be brassy, stubborn, or opinionated. Elizabeth had no intention of following those rules.

I first heard about Elizabeth Kenny when my father had a stroke and was transferred to the Elizabeth Kenny Institute in Minneapolis for recovery. Prior to that, I knew of her in name only.

Author Susan Latta I remember standing in a long line in the school gym waiting to receive my vaccination in the early 1960s, and had no idea how many people suffered after being stricken by polio.

Author Susan Latta I remember standing in a long line in the school gym waiting to receive my vaccination in the early 1960s, and had no idea how many people suffered after being stricken by polio.Decades earlier Elizabeth Kenny had become famous for her treatment for polio, a dreadful virus that caused paralysis and death.

Below: Elisabeth Kenny demonstrating polio treatment to doctors and nurses at the Elizabeth Kenny Institute in Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1943. Library of Congress photo

Elizabeth didn’t know it at the time but discovered her polio treatment one day in 1911.

Elizabeth didn’t know it at the time but discovered her polio treatment one day in 1911. A frantic farmer called for help for his two-year-old daughter. Amy's arms and

legs were twisted tight with unbearable pain.

Elizabeth Kenny galloped away to send a telegram to her trusted doctor, Aeneas McDonnell. When he replied that it was polio, he said there was nothing to be done, and to do “the best with symptoms presenting themselves.”

"I knew the relaxing power of heat," Elizabeth said. "I filled a frying pan with salt, placed it over the fire, then poured it into a bag and applied it to the leg that was giving the most pain. After an anxious wait, I saw no relief followed the application. I then prepared a linseed meal poultice, but the weight of this seemed only to increase the pain.

"At last I tore a blanket made from soft Australian wool into suitable strips and wrung them out in boiling water. These I wrapped gently about the poor tortured muscles. The whimpering of the child ceased almost immediately, and after a few more applications her eyes closed slowly and she fell asleep.”

Amy recovered. But men in the medical field refused to accept Elizabeth's methods.

In 1914, Elizabeth Kenny traveled to England to serve in WWI. The Australian Army Nursing Service gave her the title of “sister,” which had nothing to do with religion, instead meaning “senior nurse.” She became known as Sister Kenny.

In 1914, Elizabeth Kenny traveled to England to serve in WWI. The Australian Army Nursing Service gave her the title of “sister,” which had nothing to do with religion, instead meaning “senior nurse.” She became known as Sister Kenny.After the war, she presented her methods to control the muscle spasms and re-educate the paralyzed limbs to packed rooms of medical men in Australia. Over and over they called her a quack nurse from the bush, and finally she had had enough. She sailed to America to prove her treatment.

After being turned away by doctors in New York and Chicago, she landed in Minnesota where a few doctors said her treatment did work.

As word spread she gained nationwide support, even landing on a list of most admired women in America nine years running. The Elizabeth Kenny Institute opened in 1942, and still exists today as Courage Kenny, a facility for stroke and accident victims.

As word spread she gained nationwide support, even landing on a list of most admired women in America nine years running. The Elizabeth Kenny Institute opened in 1942, and still exists today as Courage Kenny, a facility for stroke and accident victims.

At right: A patient is treated in an Iron Lung circa 1960s. Photo courtesy U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Polio was eradicated in America when Albert Sabin’s live polio virus vaccine guaranteed immunity, just a few short years after Sister Kenny died in 1952.

Thank you, Susan! I'm excited to learn about the other ground-breaking medical women featured in your book, Bold Women of Medicine: 21 Stories of Astounding Discoveries, Daring Surgeries, and Healing Breakthroughs.

See more about the book and Author Susan Latta here...

Published on September 11, 2017 19:17

September 1, 2017

Labor Day More Important Now Than Ever!

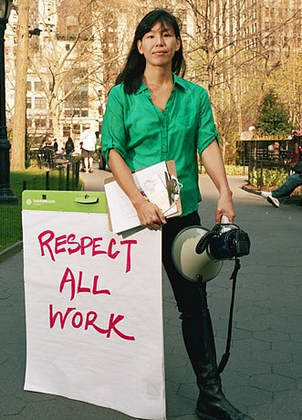

You will hear arguments that labor unions are obsolete. Twenty-eight states have passed anti-union legislation.But we have as many American workers in poverty as ever before.And we have a new generation of labor activists fighting for workers' rights. This Labor Day, let's celebrate those dedicated workers doing important , yet nearly invisible labor, on wages they can barely live on.

Take one minute and watch the video below. Let Nancy inspire you! Photo courtesy of Caring Across Generations More than sixty-five million people in America work day in and day out as family caregivers, nannies, housekeepers and home healthcare workers—that's more than the populations of California and Texas combined.

Photo courtesy of Caring Across Generations More than sixty-five million people in America work day in and day out as family caregivers, nannies, housekeepers and home healthcare workers—that's more than the populations of California and Texas combined.

Yet, they are mostly invisible except to the families they serve. They work with many of our most vulnerable people, the elderly, the disabled, the very young.

No surprise, our economy does not value this and they have few legal protections. Many tolerate low, or no pay and abusive

employers.

D’Rosa Davis is a member of the Atlanta Chapter of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which lobbies for workers rights and fair compensation. She told Caring Acros Generations,

“I earn $9 an hour....I work 70 hours one week, and then around 45 the next week...Like any mom I wish I didn’t haven’t to work so much — but when at $9 an hour what choice do I have? Earning so little means I can’t do much with my kids — and that breaks my heart."

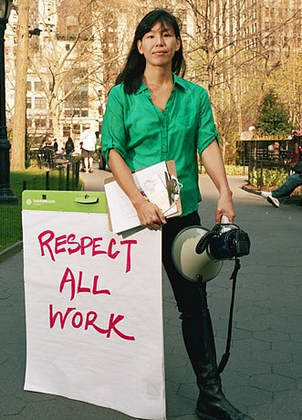

Traditional labor union bargaining over wages and hours doesn't work between families and caregivers, inspiring young activists like An-jen Poo to be creative. (I told you about her here....) Photo Courtesy Time Magazine An-Jen Poo (left) works to bring together a broad spectrum of stakeholders in the community to work together to improve the lives of workers and change the way we as a culture perceive labor.

Photo Courtesy Time Magazine An-Jen Poo (left) works to bring together a broad spectrum of stakeholders in the community to work together to improve the lives of workers and change the way we as a culture perceive labor.

She told me, " As inequality continues to rise & technology transforms jobs, we must reaffirm the value & centrality of work, and build a movement that allows workers to be a part of shaping the future of work."

Again, not surprising, it's mostly women's work she's talking about.

Ninety percent of home health aides and 95% of domestic workers are women.

Women are 47% of our country's

workforce, and nearly half of them contribute an equal share to the family budget or are the primary breadwinners in the family. Ninety percent of working women do not belong to unions. Another group of hard working, women who often live in poverty are restaurant servers.

Another group of hard working, women who often live in poverty are restaurant servers.

According to Restaurant Opportunities Center United (ROC) 70% of the people waiting tables are women, and they suffer “the worst sexual harassment of any industry in the United States.”

Aisha Thurman, told ROC, male customers “think, you know, my body is for them to enjoy, to look at, touch, say what they want.

They think if they throw me a couple dollars in the form of a tip, it’s OK.” Immigrants who fear deportation if they complain of abuse and women of color have it the worst. A recent report by the Institute of Policy Research, found that while black women vote at high rates, are increasingly earning college degrees and succeeding in owning their own businesses, they still earn less than white men and women.

Immigrants who fear deportation if they complain of abuse and women of color have it the worst. A recent report by the Institute of Policy Research, found that while black women vote at high rates, are increasingly earning college degrees and succeeding in owning their own businesses, they still earn less than white men and women.

• Black women who worked full-time and year-round had median annual earnings that were 65% percent what white men earn.

• Nearly a quarter of the nation’s black women,live in poverty, more than twice the percentage of white women. Photo courtesy Seattle Times Then there's the hotel/motel industry...

Photo courtesy Seattle Times Then there's the hotel/motel industry...

A study of phone calls to the National Human Trafficking Hotline showed 124 reports came in concerning "slave" workers in the hospitality industry in the last nine years. (Non-sex related)

Another 510 calls reported workplace abuse and labor violations. Calls to a hotline most likely represent the tip of an iceberg.

At left, Sonia Guevara, employed at a downtown Seattle hotel, voiced support for Initiative 124 which assured hotel workers new rights related to assault and sexual harassment, injuries, workloads, medical care and changes in hotel ownership.

Though some labor activist methods may be new, one part that doesn't changes is the importance of inspiring workers to believe they deserve better and to have the courage to take risks to better their situation.

Some other women in the new labor movement you might like to check out are Saru Jayaraman who founded ROC to aid restaurant workers, Nadia Marin Molina who has a labor rights resume a page long, and Sarita Gupta at Jobs With Justice.

These women are not afraid to take on company bosses. They are also working creatively to build broad support across communities for workers rights and greater justice in the lives of poor women and children.

Plenty to think about and celebrate as we enjoy the last long weekend of summer.

Take one minute and watch the video below. Let Nancy inspire you!

Photo courtesy of Caring Across Generations More than sixty-five million people in America work day in and day out as family caregivers, nannies, housekeepers and home healthcare workers—that's more than the populations of California and Texas combined.

Photo courtesy of Caring Across Generations More than sixty-five million people in America work day in and day out as family caregivers, nannies, housekeepers and home healthcare workers—that's more than the populations of California and Texas combined.

Yet, they are mostly invisible except to the families they serve. They work with many of our most vulnerable people, the elderly, the disabled, the very young.

No surprise, our economy does not value this and they have few legal protections. Many tolerate low, or no pay and abusive

employers.

D’Rosa Davis is a member of the Atlanta Chapter of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which lobbies for workers rights and fair compensation. She told Caring Acros Generations,

“I earn $9 an hour....I work 70 hours one week, and then around 45 the next week...Like any mom I wish I didn’t haven’t to work so much — but when at $9 an hour what choice do I have? Earning so little means I can’t do much with my kids — and that breaks my heart."

Traditional labor union bargaining over wages and hours doesn't work between families and caregivers, inspiring young activists like An-jen Poo to be creative. (I told you about her here....)

Photo Courtesy Time Magazine An-Jen Poo (left) works to bring together a broad spectrum of stakeholders in the community to work together to improve the lives of workers and change the way we as a culture perceive labor.

Photo Courtesy Time Magazine An-Jen Poo (left) works to bring together a broad spectrum of stakeholders in the community to work together to improve the lives of workers and change the way we as a culture perceive labor. She told me, " As inequality continues to rise & technology transforms jobs, we must reaffirm the value & centrality of work, and build a movement that allows workers to be a part of shaping the future of work."

Again, not surprising, it's mostly women's work she's talking about.

Ninety percent of home health aides and 95% of domestic workers are women.

Women are 47% of our country's

workforce, and nearly half of them contribute an equal share to the family budget or are the primary breadwinners in the family. Ninety percent of working women do not belong to unions.

Another group of hard working, women who often live in poverty are restaurant servers.

Another group of hard working, women who often live in poverty are restaurant servers.According to Restaurant Opportunities Center United (ROC) 70% of the people waiting tables are women, and they suffer “the worst sexual harassment of any industry in the United States.”

Aisha Thurman, told ROC, male customers “think, you know, my body is for them to enjoy, to look at, touch, say what they want.

They think if they throw me a couple dollars in the form of a tip, it’s OK.”

Immigrants who fear deportation if they complain of abuse and women of color have it the worst. A recent report by the Institute of Policy Research, found that while black women vote at high rates, are increasingly earning college degrees and succeeding in owning their own businesses, they still earn less than white men and women.

Immigrants who fear deportation if they complain of abuse and women of color have it the worst. A recent report by the Institute of Policy Research, found that while black women vote at high rates, are increasingly earning college degrees and succeeding in owning their own businesses, they still earn less than white men and women.• Black women who worked full-time and year-round had median annual earnings that were 65% percent what white men earn.

• Nearly a quarter of the nation’s black women,live in poverty, more than twice the percentage of white women.

Photo courtesy Seattle Times Then there's the hotel/motel industry...

Photo courtesy Seattle Times Then there's the hotel/motel industry...A study of phone calls to the National Human Trafficking Hotline showed 124 reports came in concerning "slave" workers in the hospitality industry in the last nine years. (Non-sex related)

Another 510 calls reported workplace abuse and labor violations. Calls to a hotline most likely represent the tip of an iceberg.

At left, Sonia Guevara, employed at a downtown Seattle hotel, voiced support for Initiative 124 which assured hotel workers new rights related to assault and sexual harassment, injuries, workloads, medical care and changes in hotel ownership.

Though some labor activist methods may be new, one part that doesn't changes is the importance of inspiring workers to believe they deserve better and to have the courage to take risks to better their situation.

Some other women in the new labor movement you might like to check out are Saru Jayaraman who founded ROC to aid restaurant workers, Nadia Marin Molina who has a labor rights resume a page long, and Sarita Gupta at Jobs With Justice.

These women are not afraid to take on company bosses. They are also working creatively to build broad support across communities for workers rights and greater justice in the lives of poor women and children.

Plenty to think about and celebrate as we enjoy the last long weekend of summer.

Published on September 01, 2017 20:58

July 11, 2017

America's Brave "Hello Girls"

During my research into the American WWII Nurses captured POW by the Japanese, I learned they were the "first large group" of American women sent into combat.

When I wrote PURE GRIT I didn't know about the Hello Girls, a group of American women, telephone operators, who volunteered for the U.S. Army Signal Corps in World War I. The terms "large group" and "combat" can be debated, but what's clear is that

here is another group of brave women that have only recently begun to take their rightful place in history.

The terms "large group" and "combat" can be debated, but what's clear is that

here is another group of brave women that have only recently begun to take their rightful place in history.

Grace Banker (right) was one of 223 women telephone operators who shipped out to England and France with American troops to aid communication

Grace Banker (right) was one of 223 women telephone operators who shipped out to England and France with American troops to aid communication

between commanders and soldiers on the battlefield.

Grace was the chief operator of a small group sent to the front during the Muese-Argonne Offensive, the deadliest campaign in U.S. military history, killing 26,000 Americans in the final terrible onslaught that ended the war.

The seven women operators worked near Verdun, France, connecting calls while German planes flew overhead and shrapnel landed close by. On October 30, 1919, two weeks before the war ended, a number of buildings housing American headquarters went up in flames. The women were ordered to leave the switchboard, but they refused, continuing to connect calls as the fire raged nearer and nearer.

They refused to leave their posts until threatened with disciplinary action by their superior officer. When the fire was doused an hour later, the women returned to the switchboard, found some of the lines still working and picked up where they had left off. The seven women later received Distinguished Service Medals for their courage and dedication to duty. Unidentified "Hello Girls" somewhere in France, U.S. Army Signal Corps photo. When U.S. troops arrived to join the war in Europe, they found the telephone service in France badly damaged by years of combat. Signal Corps crews quickly stretched a far-flung web of lines across Allied territory to hook up communication between units in battle, supply depots and military headquarters.

Unidentified "Hello Girls" somewhere in France, U.S. Army Signal Corps photo. When U.S. troops arrived to join the war in Europe, they found the telephone service in France badly damaged by years of combat. Signal Corps crews quickly stretched a far-flung web of lines across Allied territory to hook up communication between units in battle, supply depots and military headquarters.

General John J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces was frustrated with French telephone operators who didn't speak English and tended to spend time on social niceties before connecting calls.

He sent an urgent appeal to American newspapers for women who could speak French, operate the complicated switchboards, and free up men for combat. Seven-thousand women applied.

Only 450-were chosen for military training, and half of those deployed to Europe. Most were already trained operators employed by U.S. telephone companies, and dexterous enough to connect five calls in the time a man did one.

During the Muese-Argonne Offensive, they connected over 150,000 calls a day. Identity papers for Blanche B. Grande-Maitre (above) show her to be five-foot-two and 110 pounds. The contracts the Hello Girls signed differed little from army enlistment papers, and they "signed up for the duration."

Identity papers for Blanche B. Grande-Maitre (above) show her to be five-foot-two and 110 pounds. The contracts the Hello Girls signed differed little from army enlistment papers, and they "signed up for the duration."

At the switchboard in Tours, France hey were treated just like soldiers and subject to the same “discomforts and dangers” including

At the switchboard in Tours, France hey were treated just like soldiers and subject to the same “discomforts and dangers” including

unheated barracks, bombings and mortar fire, according to the Oct. 4, 1918 edition of the army newspaper Stars and Stripes.

“According to their superior officers, both in the Signal Corps and on the General Staff, they have shown remarkable spirit and utter absence of nerves.”

General Pershing praised the women's work, saying they had more patience and perseverance for the job than men, and other officers believed they played a crucial role in helping win the war.

But like the nurses in Pure Grit , when the hostilities ceased and they returned home, because they were women, they were not given their due. The Hello Girls did not qualify as veterans, receiving no benefits, and only a handful were recognized with medals.

It took an act of congress, and sixty years before the Hello Girls received their Honorable army discharges, veteran status and victory medals. Fifty of the women remained alive to enjoy the moment.

When I wrote PURE GRIT I didn't know about the Hello Girls, a group of American women, telephone operators, who volunteered for the U.S. Army Signal Corps in World War I.

The terms "large group" and "combat" can be debated, but what's clear is that

here is another group of brave women that have only recently begun to take their rightful place in history.

The terms "large group" and "combat" can be debated, but what's clear is that

here is another group of brave women that have only recently begun to take their rightful place in history.

Grace Banker (right) was one of 223 women telephone operators who shipped out to England and France with American troops to aid communication

Grace Banker (right) was one of 223 women telephone operators who shipped out to England and France with American troops to aid communicationbetween commanders and soldiers on the battlefield.

Grace was the chief operator of a small group sent to the front during the Muese-Argonne Offensive, the deadliest campaign in U.S. military history, killing 26,000 Americans in the final terrible onslaught that ended the war.

The seven women operators worked near Verdun, France, connecting calls while German planes flew overhead and shrapnel landed close by. On October 30, 1919, two weeks before the war ended, a number of buildings housing American headquarters went up in flames. The women were ordered to leave the switchboard, but they refused, continuing to connect calls as the fire raged nearer and nearer.

They refused to leave their posts until threatened with disciplinary action by their superior officer. When the fire was doused an hour later, the women returned to the switchboard, found some of the lines still working and picked up where they had left off. The seven women later received Distinguished Service Medals for their courage and dedication to duty.

Unidentified "Hello Girls" somewhere in France, U.S. Army Signal Corps photo. When U.S. troops arrived to join the war in Europe, they found the telephone service in France badly damaged by years of combat. Signal Corps crews quickly stretched a far-flung web of lines across Allied territory to hook up communication between units in battle, supply depots and military headquarters.

Unidentified "Hello Girls" somewhere in France, U.S. Army Signal Corps photo. When U.S. troops arrived to join the war in Europe, they found the telephone service in France badly damaged by years of combat. Signal Corps crews quickly stretched a far-flung web of lines across Allied territory to hook up communication between units in battle, supply depots and military headquarters.General John J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces was frustrated with French telephone operators who didn't speak English and tended to spend time on social niceties before connecting calls.

He sent an urgent appeal to American newspapers for women who could speak French, operate the complicated switchboards, and free up men for combat. Seven-thousand women applied.

Only 450-were chosen for military training, and half of those deployed to Europe. Most were already trained operators employed by U.S. telephone companies, and dexterous enough to connect five calls in the time a man did one.

During the Muese-Argonne Offensive, they connected over 150,000 calls a day.

Identity papers for Blanche B. Grande-Maitre (above) show her to be five-foot-two and 110 pounds. The contracts the Hello Girls signed differed little from army enlistment papers, and they "signed up for the duration."

Identity papers for Blanche B. Grande-Maitre (above) show her to be five-foot-two and 110 pounds. The contracts the Hello Girls signed differed little from army enlistment papers, and they "signed up for the duration."

At the switchboard in Tours, France hey were treated just like soldiers and subject to the same “discomforts and dangers” including

At the switchboard in Tours, France hey were treated just like soldiers and subject to the same “discomforts and dangers” including unheated barracks, bombings and mortar fire, according to the Oct. 4, 1918 edition of the army newspaper Stars and Stripes.

“According to their superior officers, both in the Signal Corps and on the General Staff, they have shown remarkable spirit and utter absence of nerves.”

General Pershing praised the women's work, saying they had more patience and perseverance for the job than men, and other officers believed they played a crucial role in helping win the war.

But like the nurses in Pure Grit , when the hostilities ceased and they returned home, because they were women, they were not given their due. The Hello Girls did not qualify as veterans, receiving no benefits, and only a handful were recognized with medals.

It took an act of congress, and sixty years before the Hello Girls received their Honorable army discharges, veteran status and victory medals. Fifty of the women remained alive to enjoy the moment.

Published on July 11, 2017 01:00

July 11th, 2017

During my research into the American WWII Nurses captured POW by the Japanese, I learned they were the "first large group" of American women sent into combat.

When I wrote PURE GRIT I didn't know about the Hello Girls, a group of American women, telephone operators, who volunteered for the U.S. Army Signal Corps in World War I. The terms "large group" and "combat" can be debated, but what's clear is that

here is another group of brave women that have only recently begun to take their rightful place in history.

The terms "large group" and "combat" can be debated, but what's clear is that

here is another group of brave women that have only recently begun to take their rightful place in history.

Grace Banker (right) was one of 223 women telephone operators who shipped out to England and France with American troops to aid communication

Grace Banker (right) was one of 223 women telephone operators who shipped out to England and France with American troops to aid communication

between commanders and soldiers on the battlefield.

Grace was the chief operator of a small group sent to the front during the Muese-Argonne Offensive, the deadliest campaign in U.S. military history, killing 26,000 Americans in the final terrible onslaught that ended the war.

The seven women operators worked near Verdun, France, connecting calls while German planes flew overhead and shrapnel landed close by. On October 30, 1919, two weeks before the war ended, a number of buildings housing American headquarters went up in flames. The women were ordered to leave the switchboard, but they refused, continuing to connect calls as the fire raged nearer and nearer.

They refused to leave their posts until threatened with disciplinary action by their superior officer. When the fire was doused an hour later, the women returned to the switchboard, found some of the lines still working and picked up where they had left off. The seven women later received Distinguished Service Medals for their courage and dedication to duty. Unidentified "Hello Girls" somewhere in France, U.S. Army Signal Corps photo. When U.S. troops arrived to join the war in Europe, they found the telephone service in France badly damaged by years of combat. Signal Corps crews quickly stretched a far-flung web of lines across Allied territory to hook up communication between units in battle, supply depots and military headquarters.

Unidentified "Hello Girls" somewhere in France, U.S. Army Signal Corps photo. When U.S. troops arrived to join the war in Europe, they found the telephone service in France badly damaged by years of combat. Signal Corps crews quickly stretched a far-flung web of lines across Allied territory to hook up communication between units in battle, supply depots and military headquarters.

General John J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces was frustrated with French telephone operators who didn't speak English and tended to spend time on social niceties before connecting calls.

He sent an urgent appeal to American newspapers for women who could speak French, operate the complicated switchboards, and free up men for combat. Seven-thousand women applied.

Only 450-were chosen for military training, and half of those deployed to Europe. Most were already trained operators employed by U.S. telephone companies, and dexterous enough to connect five calls in the time a man did one.

During the Muese-Argonne Offensive, they connected over 150,000 calls a day. Identity papers for Blanche B. Grande-Maitre (above) show her to be five-foot-two and 110 pounds. The contracts the Hello Girls signed differed little from army enlistment papers, and they "signed up for the duration."

Identity papers for Blanche B. Grande-Maitre (above) show her to be five-foot-two and 110 pounds. The contracts the Hello Girls signed differed little from army enlistment papers, and they "signed up for the duration."

At the switchboard in Tours, France hey were treated just like soldiers and subject to the same “discomforts and dangers” including

At the switchboard in Tours, France hey were treated just like soldiers and subject to the same “discomforts and dangers” including

unheated barracks, bombings and mortar fire, according to the Oct. 4, 1918 edition of the army newspaper Stars and Stripes.

“According to their superior officers, both in the Signal Corps and on the General Staff, they have shown remarkable spirit and utter absence of nerves.”

General Pershing praised the women's work, saying they had more patience and perseverance for the job than men, and other officers believed they played a crucial role in helping win the war.

But like the nurses in Pure Grit , when the hostilities ceased and they returned home, because they were women, they were not given their due. The Hello Girls did not qualify as veterans, receiving no benefits, and only a handful were recognized with medals.

It took an act of congress, and sixty years before the Hello Girls received their Honorable army discharges, veteran status and victory medals. Fifty of the women remained alive to enjoy the moment.

When I wrote PURE GRIT I didn't know about the Hello Girls, a group of American women, telephone operators, who volunteered for the U.S. Army Signal Corps in World War I.

The terms "large group" and "combat" can be debated, but what's clear is that

here is another group of brave women that have only recently begun to take their rightful place in history.

The terms "large group" and "combat" can be debated, but what's clear is that

here is another group of brave women that have only recently begun to take their rightful place in history.

Grace Banker (right) was one of 223 women telephone operators who shipped out to England and France with American troops to aid communication

Grace Banker (right) was one of 223 women telephone operators who shipped out to England and France with American troops to aid communicationbetween commanders and soldiers on the battlefield.

Grace was the chief operator of a small group sent to the front during the Muese-Argonne Offensive, the deadliest campaign in U.S. military history, killing 26,000 Americans in the final terrible onslaught that ended the war.

The seven women operators worked near Verdun, France, connecting calls while German planes flew overhead and shrapnel landed close by. On October 30, 1919, two weeks before the war ended, a number of buildings housing American headquarters went up in flames. The women were ordered to leave the switchboard, but they refused, continuing to connect calls as the fire raged nearer and nearer.

They refused to leave their posts until threatened with disciplinary action by their superior officer. When the fire was doused an hour later, the women returned to the switchboard, found some of the lines still working and picked up where they had left off. The seven women later received Distinguished Service Medals for their courage and dedication to duty.

Unidentified "Hello Girls" somewhere in France, U.S. Army Signal Corps photo. When U.S. troops arrived to join the war in Europe, they found the telephone service in France badly damaged by years of combat. Signal Corps crews quickly stretched a far-flung web of lines across Allied territory to hook up communication between units in battle, supply depots and military headquarters.

Unidentified "Hello Girls" somewhere in France, U.S. Army Signal Corps photo. When U.S. troops arrived to join the war in Europe, they found the telephone service in France badly damaged by years of combat. Signal Corps crews quickly stretched a far-flung web of lines across Allied territory to hook up communication between units in battle, supply depots and military headquarters.General John J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces was frustrated with French telephone operators who didn't speak English and tended to spend time on social niceties before connecting calls.

He sent an urgent appeal to American newspapers for women who could speak French, operate the complicated switchboards, and free up men for combat. Seven-thousand women applied.

Only 450-were chosen for military training, and half of those deployed to Europe. Most were already trained operators employed by U.S. telephone companies, and dexterous enough to connect five calls in the time a man did one.

During the Muese-Argonne Offensive, they connected over 150,000 calls a day.

Identity papers for Blanche B. Grande-Maitre (above) show her to be five-foot-two and 110 pounds. The contracts the Hello Girls signed differed little from army enlistment papers, and they "signed up for the duration."

Identity papers for Blanche B. Grande-Maitre (above) show her to be five-foot-two and 110 pounds. The contracts the Hello Girls signed differed little from army enlistment papers, and they "signed up for the duration."

At the switchboard in Tours, France hey were treated just like soldiers and subject to the same “discomforts and dangers” including

At the switchboard in Tours, France hey were treated just like soldiers and subject to the same “discomforts and dangers” including unheated barracks, bombings and mortar fire, according to the Oct. 4, 1918 edition of the army newspaper Stars and Stripes.

“According to their superior officers, both in the Signal Corps and on the General Staff, they have shown remarkable spirit and utter absence of nerves.”

General Pershing praised the women's work, saying they had more patience and perseverance for the job than men, and other officers believed they played a crucial role in helping win the war.

But like the nurses in Pure Grit , when the hostilities ceased and they returned home, because they were women, they were not given their due. The Hello Girls did not qualify as veterans, receiving no benefits, and only a handful were recognized with medals.

It took an act of congress, and sixty years before the Hello Girls received their Honorable army discharges, veteran status and victory medals. Fifty of the women remained alive to enjoy the moment.

Published on July 11, 2017 01:00

June 26, 2017

Speed, Endurance & the Courage to defy Mussolini

First day of summer, I dragged out my bicycle, my wonderful husband pumped up the flat tires, and I vowed to start riding it more and driving the car less.

To inspire myself, I'm writing the story of Gino Bartali, one of the greatest cyclists of all time and a genuine hero. “Good is something you do, not something you talk about. Some medals are pinned to your soul, not to your jacket

.

”

So said this two-time winner of the Tour de France. Above, Gino Bartali in 1936.

“Good is something you do, not something you talk about. Some medals are pinned to your soul, not to your jacket

.

”

So said this two-time winner of the Tour de France. Above, Gino Bartali in 1936.

In between his cycling victories, Bartali helped save some 800 Jews from the Nazis. Gino Bartali grew from humble beginnings in rural Tuscany, his father a day laborer, his mother a lace maker.

Gino Bartali grew from humble beginnings in rural Tuscany, his father a day laborer, his mother a lace maker.

At age 11 he rode a bicycle to school in Florence from his village Ponte a Ema.

Wheeling through the Tuscany hills, Gino developed a love for cycling, and a heart for tackling mountains.

He won his first race at the age of 17, and at 24, rode to victory in the 1938 Tour de France, gaining international acclaim.

Back in Italy, Benito Mussolini wanted to claim Bartali's victory as proof Italians were part of the master race, but in a risky move, Gino refused to go along with the fascist dictator. In the 1938 Tour de France, Gino Bartali was first over the Col de Vars in the 14th stage. When World War II sidetracked Gino's cycling career, he found an even more valuable way to use his bike. In 1943, Germany occupied Italy and the Nazis started shipping Italian Jews to concentration camps. Bartali agreed to aid the Italian Resistance as a courier.

In the 1938 Tour de France, Gino Bartali was first over the Col de Vars in the 14th stage. When World War II sidetracked Gino's cycling career, he found an even more valuable way to use his bike. In 1943, Germany occupied Italy and the Nazis started shipping Italian Jews to concentration camps. Bartali agreed to aid the Italian Resistance as a courier.

Under the guise of long training rides and wearing an Italian racing jersey, Bartali risked his life transporting photographs and counterfeit documents in the hollow frame and handlebars of his bicycle.

The photos and documents provided Italian Jews with false identity cards to protect them from the Nazis. People caught helping Jews evade capture were often executed immediately. Bartali saved a friend Giacomo Goldenberg and his family by providing food and hiding them in an apartment he owned in Florence.

Bartali saved a friend Giacomo Goldenberg and his family by providing food and hiding them in an apartment he owned in Florence.

Without his help, the family would most probably have died in the Holocaust. At left, the Goldenberg family--Elvira and Giacomo with their son Giorgio and their daughter Tea.

In July 1944, Bartali was arrested and interrogated at Villa Triste in Florence, where local Fascist officials questioned and tortured prisoners. Fortunately, one of the interrogators had known Bartali before the war and convinced the others he should be let go. When the war was over, Gino went back to racing, racking up a third career victory in the Giro d'Italia in 1946, shown above. Then he shocked the cycling world by returning to win the Tour de France again, ten years after his first victory. No other cyclist has achieved that feat.

When the war was over, Gino went back to racing, racking up a third career victory in the Giro d'Italia in 1946, shown above. Then he shocked the cycling world by returning to win the Tour de France again, ten years after his first victory. No other cyclist has achieved that feat.

Bartali was known as a fierce competitor up until he retired at age 40, after being injured in a road accident. He was somewhat of a loudmouth on the cycling circuit, but modest about the fact he's credited with helping save the lives of hundreds of people. The story did not come out before he passed away in 2000.

Biographer, Ali McConnon told CNN, "He was very modest about it. He held a profound sense that so many had suffered in a much greater capacity than he had. He didn't want to be in the spotlight or diminish the contributions of others."

Bartali rarely spoke of his actions in the war. When asked by another reporter to recount his greatest victory, Gino said, “I won the challenge of life, winning the love of the people.”

Now, there's a man who's inspiring in a good number of ways!

To inspire myself, I'm writing the story of Gino Bartali, one of the greatest cyclists of all time and a genuine hero.

“Good is something you do, not something you talk about. Some medals are pinned to your soul, not to your jacket

.

”

So said this two-time winner of the Tour de France. Above, Gino Bartali in 1936.

“Good is something you do, not something you talk about. Some medals are pinned to your soul, not to your jacket

.

”

So said this two-time winner of the Tour de France. Above, Gino Bartali in 1936.In between his cycling victories, Bartali helped save some 800 Jews from the Nazis.

Gino Bartali grew from humble beginnings in rural Tuscany, his father a day laborer, his mother a lace maker.

Gino Bartali grew from humble beginnings in rural Tuscany, his father a day laborer, his mother a lace maker.At age 11 he rode a bicycle to school in Florence from his village Ponte a Ema.

Wheeling through the Tuscany hills, Gino developed a love for cycling, and a heart for tackling mountains.

He won his first race at the age of 17, and at 24, rode to victory in the 1938 Tour de France, gaining international acclaim.

Back in Italy, Benito Mussolini wanted to claim Bartali's victory as proof Italians were part of the master race, but in a risky move, Gino refused to go along with the fascist dictator.

In the 1938 Tour de France, Gino Bartali was first over the Col de Vars in the 14th stage. When World War II sidetracked Gino's cycling career, he found an even more valuable way to use his bike. In 1943, Germany occupied Italy and the Nazis started shipping Italian Jews to concentration camps. Bartali agreed to aid the Italian Resistance as a courier.