Penny Colman's Blog, page 5

November 10, 2019

Pre-2020

Sophie, our oldest grandchild, is on her first college tour at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.  Her dad, Jon, just texted this photo of Sophie and her mother Katrin in front of a women’s suffrage display in the State Capitol. I love learning about pre-centennial celebrations of the 19th Amendment in 2020—from this display to youngsters planting daffodils in Portland to the new suffrage statue in Little Rock, featuring ECS with her daughter Harriot, SBA, Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, & Alice Paul. I wrote about Wisconsin suffragists in my new book “The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight,” including Olympia Brown, a pioneer suffragist who finally voted in 1920 at the age of 91. Brown, the first woman to be ordained by a

Her dad, Jon, just texted this photo of Sophie and her mother Katrin in front of a women’s suffrage display in the State Capitol. I love learning about pre-centennial celebrations of the 19th Amendment in 2020—from this display to youngsters planting daffodils in Portland to the new suffrage statue in Little Rock, featuring ECS with her daughter Harriot, SBA, Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, & Alice Paul. I wrote about Wisconsin suffragists in my new book “The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight,” including Olympia Brown, a pioneer suffragist who finally voted in 1920 at the age of 91. Brown, the first woman to be ordained by a  regularly established denomination, spent 10 years as the pastor of a Unitarian Universalist Church in Racine before resigning in 1887 to fully fight for the vote. Today the church is named for her. (Click of image to enlarge it.)

regularly established denomination, spent 10 years as the pastor of a Unitarian Universalist Church in Racine before resigning in 1887 to fully fight for the vote. Today the church is named for her. (Click of image to enlarge it.)

October 24, 2019

Who Is That On the Cover of My Book?

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight? From the moment I saw the photo of the Rose Bower wearing a Votes for

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight? From the moment I saw the photo of the Rose Bower wearing a Votes for

Women sash and playing her cornet, I decided that she was going to be featured on the cover of my book.

Women sash and playing her cornet, I decided that she was going to be featured on the cover of my book. Born in Vermillion, South Dakota in 1873, Rose moved with her family to the Black Hills when she was twelve. Learning music from her Aunt Lida, she played in the Bower Family Band. She attended several music schools, including the New England Conservatory of Music. After short stints as a teacher and librarian, Rose Bower turned her attention and musical skills—singing, playing the piano, cornet, trumpet, and expert whistling— to suffrage work in 1907.

It took seven referenda (six for equal suffrage and one for school) in South Dakota before male voters approved an amendment to the state constitution to enfranchise women in 1918. Rose Bower was an avid campaigner—writing letters to newspapers, fundraising, lobbying, playing the cornet and whistling to draw crowds, and making suffrage speeches. On the Fourth of July in 1914, Rose, wearing a sun bonnet, spoke “on the top of Lodge Pole Butte at a picnic many miles from a shade tree . . . with a flock of two thousand sheep grazing around.” An eloquent speaker as well as a commanding musician, her reputation spread and she was enlisted to campaigns in other states, including Illinois, New Jersey, and New York.

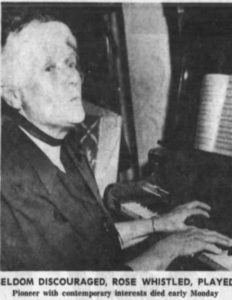

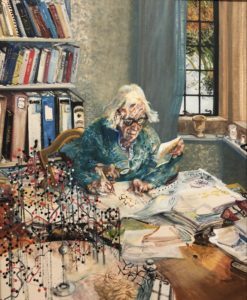

Rose Bower died at the age of 92. In the picture below you can clearly see an elderly Rose Bower playing the piano and whistling. The image illustrated her obituary in the Rapid City Journal, July 26, 1965. The caption read: “SELDOM DISCOURAGED, ROSE WHISTLED, PLAYED/Pioneer with contemporary interests died early Monday.”

October 9, 2019

Suffragists Road Trip: Natick & Framingham, MA, New Haven, CT

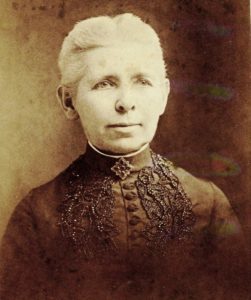

We recently drove to Natick, Massachusetts for an overnight stay. With women’s fierce fight for the vote always on my mind, I did a Google search for suffragists in Natick. Olive Augusta Alger Cheney, who lived in Natick for 56 years, was a wonderful discovery. Augusta Cheney, the name she preferred, led an activist life as temperance advocate, suffrage leader, ardent feminist, editor, and author. In 1877, she founded the Women’s Suffrage Club of Natick, serving as president until 1891. In 1881, the Suffrage Club got a measure on the agenda of the town meeting that the “Town” ask the state legislature to “extend to women who are citizens, the right to hold Town offices, and to vote in Town affairs, on the same terms as male citizens.” Only men could vote at town meetings and they voted “no.” And “no” again in 1882, and in 1883. Augusta Cheney kept up the fight at the local and state levels. On March 6, 1891, she wrote in her regular column in a Natick newspaper: “Home is not the place for every woman. If a woman can do more for her fellows by a public life (and many can), then it is her duty to live her life for the public: If she can do more at home, then her duty is there, and the same will apply to men. There are many men today who would do the country immeasurable good if they would sink into oblivion.” In 1916, four years before the battle was won, Augusta Cheney died at the age of 83. She is buried in Glenwood Cemetery, South Natick. Having included many local and state suffragists in my book The Vote: Women’s First Fight, I was happy to learn about another one—Augusta Cheney. (Click on an image to enlarge it.)

“no.” And “no” again in 1882, and in 1883. Augusta Cheney kept up the fight at the local and state levels. On March 6, 1891, she wrote in her regular column in a Natick newspaper: “Home is not the place for every woman. If a woman can do more for her fellows by a public life (and many can), then it is her duty to live her life for the public: If she can do more at home, then her duty is there, and the same will apply to men. There are many men today who would do the country immeasurable good if they would sink into oblivion.” In 1916, four years before the battle was won, Augusta Cheney died at the age of 83. She is buried in Glenwood Cemetery, South Natick. Having included many local and state suffragists in my book The Vote: Women’s First Fight, I was happy to learn about another one—Augusta Cheney. (Click on an image to enlarge it.)

We then stopped in neighboring Framingham, home of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller who lived on Warren Street. A prominent African American artist, Fuller, a  member of the Framingham Equal Suffrage League, was well known for her sculptures. In 1915, she created the Equal Suffrage Medallion that was

member of the Framingham Equal Suffrage League, was well known for her sculptures. In 1915, she created the Equal Suffrage Medallion that was  sold at fundraising fairs for the Framingham Equal Suffrage League. The coin-size medallion had a bas-relief profile portrait of a man, a woman, and a child, with the inscription: “Each unto each the rounded complement.” Fuller is pictured on the left and the medallion on the right.

sold at fundraising fairs for the Framingham Equal Suffrage League. The coin-size medallion had a bas-relief profile portrait of a man, a woman, and a child, with the inscription: “Each unto each the rounded complement.” Fuller is pictured on the left and the medallion on the right.

Mary Ware Dennett lived on Gates Street. A divorced suffragist with two young sons, Dennett supported herself working as the highly effective corresponding secretary of the National Woman Suffrage Association. Her sons handed out fliers, sold tickets to suffrage events, held placards, and endured abuse from name-calling to  spitting. Image on left is Devon Dennett, c. 1909, holding an “I WISH MOTHER COULD VOTE” sign. I quote Mary Ware Dennett

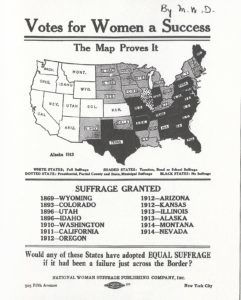

spitting. Image on left is Devon Dennett, c. 1909, holding an “I WISH MOTHER COULD VOTE” sign. I quote Mary Ware Dennett in The Vote: “We claim in no uncertain voice that the time has come when women should have the one efficient tool with which to make for themselves decent and safe working conditions—the ballot.” Image on right is a widely distributed suffrage map that Dennett created and credited herself with her initials “By M.W. D.” Suffrage maps were produced throughout the fierce fight for the vote.

in The Vote: “We claim in no uncertain voice that the time has come when women should have the one efficient tool with which to make for themselves decent and safe working conditions—the ballot.” Image on right is a widely distributed suffrage map that Dennett created and credited herself with her initials “By M.W. D.” Suffrage maps were produced throughout the fierce fight for the vote.

In front of the Edgell Memorial Library, I photographed the sign for “Mayo-Collins Square,” honoring  Louise Parker Mayo and Josephine Collins, two women who participated in suffrage demonstrations that I wrote about in my book The Vote. Mayo, one of the silent sentinels who picketed the White House, was arrested along with 15 other women on July 14, 1917. After refusing to pay the $25 fine, Mayo, the mother of seven and a former schoolteacher, and the other women were sentenced to 60 days in the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia. Succumbing to public pressure, President Woodrow Wilson pardoned the women after three days, an act he would never again repeat for imprisoned suffragists. One of Mayo’s daughter said, “Of course we feel terribly to have mother arrested. It seems like a disgrace, doesn’t it. But we don’t mind for it’s in a good cause.” In February 1919, Josephine Collins, the owner of several shops in Framingham, attended a demonstration in Boston, carrying a sign inscribed, Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty? Collins and other women were arrested, refused to pay the fine and were sentenced to eight days in the Charles Street Jail. After a few days, an unknown benefactor paid their fines. Determined to served their whole sentence, the women refused to leave. A headline in a newspaper in Phoenix, Arizona reported the outcome: FINES PAID THEY REFUSE TO QUIT JAIL—EJECTED.

Louise Parker Mayo and Josephine Collins, two women who participated in suffrage demonstrations that I wrote about in my book The Vote. Mayo, one of the silent sentinels who picketed the White House, was arrested along with 15 other women on July 14, 1917. After refusing to pay the $25 fine, Mayo, the mother of seven and a former schoolteacher, and the other women were sentenced to 60 days in the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia. Succumbing to public pressure, President Woodrow Wilson pardoned the women after three days, an act he would never again repeat for imprisoned suffragists. One of Mayo’s daughter said, “Of course we feel terribly to have mother arrested. It seems like a disgrace, doesn’t it. But we don’t mind for it’s in a good cause.” In February 1919, Josephine Collins, the owner of several shops in Framingham, attended a demonstration in Boston, carrying a sign inscribed, Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty? Collins and other women were arrested, refused to pay the fine and were sentenced to eight days in the Charles Street Jail. After a few days, an unknown benefactor paid their fines. Determined to served their whole sentence, the women refused to leave. A headline in a newspaper in Phoenix, Arizona reported the outcome: FINES PAID THEY REFUSE TO QUIT JAIL—EJECTED.

An hour and a half from home, we spontaneously decided to visit the Yale Art Museum in New Haven, Connecticut. Much to my amazement, I serendipitously saw Hiram Powers’ statue The Greek Slave that he made in 1850, after his original statue of 1844. It is the  version Lucy Stone saw in May 1851 at an exhibition in Boston. I wrote about her encounter with the statue in my book, The Vote, (p. 13):”‘Hot tears came to my eyes at the thought of millions of women who must be freed.’ That night she infused women’s rights in her anti-slavery lecture. An official of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society chastised her, saying, “people came to hear anti-slaver, and not woman’s rights.”

version Lucy Stone saw in May 1851 at an exhibition in Boston. I wrote about her encounter with the statue in my book, The Vote, (p. 13):”‘Hot tears came to my eyes at the thought of millions of women who must be freed.’ That night she infused women’s rights in her anti-slavery lecture. An official of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society chastised her, saying, “people came to hear anti-slaver, and not woman’s rights.”

“I was a woman before I was an abolitionist, I must speak for women,” she replied.

October 4, 2019

BookWomen and My Next Book

The Oct.-Nov. issue of my favorite book magazine—”BookWomen”— just arrived with an article by Mollie Hoben about my forthcoming Book: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight.

The Oct.-Nov. issue of my favorite book magazine—”BookWomen”— just arrived with an article by Mollie Hoben about my forthcoming Book: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight.

(Click on an image to enlarge it.)

September 15, 2019

The Vote Road Trip: Days 21, 22, 23 London

8/16 Our hotel room has a bay window with a brocade cushion. I am sitting there looking out through tree leaves onto a street just 100 yards from Trafalgar Square with a large fountain and a towering column with Lord Nelson standing  atop. Double decker buses, cars, pedestrians swirl around the Square. The National Gallery spans one side; a Waterstone bookstore is at our corner, where people pitch tents for their night lodging (3 tents this morning). It is a bee hive of buskers (street performers), protest activity, e.g., the Homeless Poet who chalks elegant script anti-money and pro-love messages on the stone plaza. Two huge groups gathered in the Square to march down Whitehall Street, the half mile to Parliament Square—“Fight for Freedom Stand with Hong Kong” and Vegans/Animal Rights. During our walk down Whitehall, I spotted a hulking Memorial to the Women of World War II in the middle of the wide street. Sculpted by

atop. Double decker buses, cars, pedestrians swirl around the Square. The National Gallery spans one side; a Waterstone bookstore is at our corner, where people pitch tents for their night lodging (3 tents this morning). It is a bee hive of buskers (street performers), protest activity, e.g., the Homeless Poet who chalks elegant script anti-money and pro-love messages on the stone plaza. Two huge groups gathered in the Square to march down Whitehall Street, the half mile to Parliament Square—“Fight for Freedom Stand with Hong Kong” and Vegans/Animal Rights. During our walk down Whitehall, I spotted a hulking Memorial to the Women of World War II in the middle of the wide street. Sculpted by  John W. Mills and unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II in 2005, I would rate it as the most

John W. Mills and unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II in 2005, I would rate it as the most  peculiar memorial to women I have ever seen. Attached mid-way up a block of black granite—22 feet high, 16 feet long and 6 feet wide—are 17 individual sets of clothing and uniforms representing all the ways women served during World War II. I found the empty garments disturbing, actually creepy. It is in stark contrast to the statues across the street of high-ranking military men in uniforms bedecked with medals. (Click on a picture to enlarge)

peculiar memorial to women I have ever seen. Attached mid-way up a block of black granite—22 feet high, 16 feet long and 6 feet wide—are 17 individual sets of clothing and uniforms representing all the ways women served during World War II. I found the empty garments disturbing, actually creepy. It is in stark contrast to the statues across the street of high-ranking military men in uniforms bedecked with medals. (Click on a picture to enlarge)

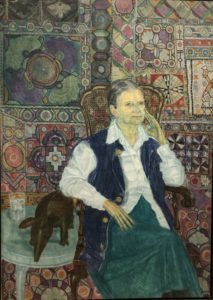

8/17 We revisited the National Portrait Gallery and discovered wonderful portraits: Doris Lessing, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature by Leonard William McCo mb; Dorothy Hodgkin, winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry,

mb; Dorothy Hodgkin, winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry,  portrayed by artist Maggie Hambling with the structural model of the four molecules of insulin that she had defined and with four hands to “indicate energy and activity;” a featureless Virginia Woolf by her sister Vanes

portrayed by artist Maggie Hambling with the structural model of the four molecules of insulin that she had defined and with four hands to “indicate energy and activity;” a featureless Virginia Woolf by her sister Vanes sa Bell;

sa Bell;

Christabel Pankhurst by Ethel Wright; and  Emmeline Pankhurst painted by Georgina Agnes Brackenbury in 1927, the year before Emmeline died, just months before the Act that finally enfranchised all women over the age of 21.

Emmeline Pankhurst painted by Georgina Agnes Brackenbury in 1927, the year before Emmeline died, just months before the Act that finally enfranchised all women over the age of 21.

8/18 We took the underground to Hyde Park where on a Sunday, 111 years ago (June 21, 1908), 30,000 women carrying 700 banners marched in seven processions along different routes for a demonstration and rally. Organized by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, treasurer of the WSPU and co-editor with her husband Frederick of “Votes for Women,” it was said to be the largest demonstration held up to that time in Great Britain. She asked women to wear white and selected purple, white, and green as the official colors. Purple for “dignity,” she said, white for “purity,” and  green for “hope.” Stores advertised white dresses and tricolor scarves. Half a million people lined the routes and gathered in the park to listen to suffrage speakers. Alice Paul, who was studying in London and would become a key leader in the American fight, was inspired by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence’s speech to join the WSPU. Men participated, including George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Thomas Hardy.

green for “hope.” Stores advertised white dresses and tricolor scarves. Half a million people lined the routes and gathered in the park to listen to suffrage speakers. Alice Paul, who was studying in London and would become a key leader in the American fight, was inspired by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence’s speech to join the WSPU. Men participated, including George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Thomas Hardy.

From the entrance to Hyde Park, we walked a half mile to the Royal Albert Hall, the site of memorable speeches and events held by suffragettes, suffragists, and anti-suffragist. Suffragettes called it their “Temple of Liberty.” Seeing the distinctive dome with the great mosaic frieze come into view, I thought of Helen Ogston, dubbed “The Lady with the Whip,” who interrupted a Liberal Party meeting and used her dog whip to fight off guards  who tried to remove her. Of great importance to the American fight was when Alva Belmont heard Emmeline Pankhurst speak in Royal Albert Hall and was fired up to switch her considerable financial resources and prodigious energy from the staid National American Woman Suffrage Association to the upstart National Woman’s Party, founded by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns.

who tried to remove her. Of great importance to the American fight was when Alva Belmont heard Emmeline Pankhurst speak in Royal Albert Hall and was fired up to switch her considerable financial resources and prodigious energy from the staid National American Woman Suffrage Association to the upstart National Woman’s Party, founded by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns.

We took the double-decker bus back to Trafalgar Square, where we revisited a statue we had serendipitously discovered located across from the entrance to the National Portrait Gallery: the Edith Cavell Memorial by George Frampton dedicated in 1920. Edith Cavell was a British nurse who tended to soldiers regardless of which side they fought on during World War I. Accused of treason for helping 200 soldiers escape from German-occupied Belgium, she was tried, convicted, and executed by a German firing squad on October 12,  1915. The figure of Cavell dressed in her nurse’s uniform is ten feet high. The pylon is forty feet high. The inscription on the front reads: “Edith Cavell/Brussels/Dawn/October 12th, 1915/Patriotism is not enough/I must have no hatred/bitterness for anyone.” The words are what she said to a chaplain the night before her execution. They were added in 1924 at the request of the National Council of Women.

1915. The figure of Cavell dressed in her nurse’s uniform is ten feet high. The pylon is forty feet high. The inscription on the front reads: “Edith Cavell/Brussels/Dawn/October 12th, 1915/Patriotism is not enough/I must have no hatred/bitterness for anyone.” The words are what she said to a chaplain the night before her execution. They were added in 1924 at the request of the National Council of Women.

Tomorrow, 8/19, we have a very early wake-up call for a taxi to the airport. When I get the inevitable question: What did you like best about your trip? Without hesitation I will answer EVERYTHING!

The Vote Road Trip: Day 20 Leicester, Knebworth

Leicester Seamstress

Alice Hawkins

8/15 There were two statues to visit in the city center of Leicester, one of the oldest cities in England. The Leicester Seamtress by James Butler dedicated in 1990 in honor of hosiery makers, an important  industry in Leicester, and A Sister in Freedom, Alice Hawkins by Sean Hedges-Quinn dedicated in 2018. We found both statues near each other, but drove around and around searching for nearby parking. We finally parked in a hopefully legal spot. Linda stayed with the car and I raced off, again in the rain, forgetting to scan the environment in order to remember my way back. At Hawkins’ statue, a hot dog vendor and I got into a tug of war over his yellow sign beside the statue. I would move it. By the time I got in place to take a picture, he had replaced it. (Click on a picture to enlarge it.)

industry in Leicester, and A Sister in Freedom, Alice Hawkins by Sean Hedges-Quinn dedicated in 2018. We found both statues near each other, but drove around and around searching for nearby parking. We finally parked in a hopefully legal spot. Linda stayed with the car and I raced off, again in the rain, forgetting to scan the environment in order to remember my way back. At Hawkins’ statue, a hot dog vendor and I got into a tug of war over his yellow sign beside the statue. I would move it. By the time I got in place to take a picture, he had replaced it. (Click on a picture to enlarge it.)

Add on purple shoelaces

back view

Depicted forthrightly speaking, Hawkins is gesturing with one hand and holding a scroll in the other. A “Votes for Women” sash is across her long dress, and a fashionable hat on her head. Striving to project respectability suffragettes typically wore hats, as did British and American suffragists. I am planning to do a photo essay on the hats worn by women fighting for the vote!

Constance Lytton

Happily I found my way back to Linda. Then we were on to a stop I had been anticipating—the Lytton Mausoleum In Knebworth, the burial place of Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton, known as Constance Lytton. Involved in prison reform, she became interested in the WSPU, although she didn’t approve of the militant tactics. But the government’s harsh opposition and police brutality changed her mind: In 1908 she wrote to her aunt—“I go deeper and deeper in my enthusiasm . . .as I understand more and more—not only what they do, but what has been done to them to drive them to their tactics.”

Lytton as Jane Warton

Arrested in 1909 and given a 30 day sentence, she was released after fourteen days. Convinced that she received special treatment because of her family (her brother was a member of Parliament), Constance Lytton disguised herself as Jane Wharton, a London seamstress. She threw a stone to get arrested and imprisoned as Jane Wharton. In the Walton Gaol in Liverpool, she was brutally force fed eight times and smacked in the face by a doctor. Her sister finally tracked her down and she was immediately released. (The incident was covered in American newspapers and I included it in my book The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight.)

Constance Lytton spoke and wrote a book Prisons and Prisoners about her experience and helped bring about prison reforms. In 1920, she sent a telegram to the National Woman’s Party celebrating the victory of the American fight for the vote. Never a physically healthy  person she had been greatly weakened by her treatment in prison. In 1923, she died at the age of 54. Lady Constance Lytton was buried in the Lytton Mausoleum near the medieval St. Mary’s Church, on the grounds of the Knebworth House, home of the Lytton family since 1490. Part of her epitaph inscribed on a sidewall of the mausoleum notes that she “. . . sacrificed her health and talents in helping to bring victory to the cause.”

person she had been greatly weakened by her treatment in prison. In 1923, she died at the age of 54. Lady Constance Lytton was buried in the Lytton Mausoleum near the medieval St. Mary’s Church, on the grounds of the Knebworth House, home of the Lytton family since 1490. Part of her epitaph inscribed on a sidewall of the mausoleum notes that she “. . . sacrificed her health and talents in helping to bring victory to the cause.”

Open to the public Knebworth House, an elegant English country house, is the site of various events. Its grounds feature gardens, an adventure playground, and a dinosaur park. We arrived late in the afternoon on a cold, rainy day. I explained our purpose and the attendant at the toll booth allowed us to enter without paying.

September 14, 2019

The Vote Road Trip: Days 18 and 19 Leeds, Oldham and Manchester

Leonora Cohen

8/13 We did not always find what we were looking for. In Leeds, we were thwarted in our search for the blue plaque to Leonora Cohen by parking that required coins not a credit card, along with overwhelming swarms of tourists, and knowing we had another stop to fit in before Manchester. Lenora Cohen was dubbed the “Tower Suffragette” after she used an iron bar she had hidden under her coat to smashed a glass case in Jewel House in the Tower of London. Her note attached to the bar read on one side: “Jewel House, Tower of London. My Protest to the Government for its refusal to Enfranchise Women but continues to torture women prisoners—Deed Not Words.” The other side read: “Votes for Women. 100 years of Constitutional Petition, Resolutions, Meetings & Processions have Failed.” Arrested and imprisoned, she undertook a hunger strike and was force-fed. After the vote was won, Leonora Cohen became one of the first female magistrates in England. She lived to be 105. Her blue plaque text: “Leading suffragette famous for smashing/ a showcase in the Jewel House at the/ Tower of London and for her hunger/ strike at Armley Gaol in 1913/ Lived here 1923-1936/1873-1978.”

Annie Kenney

In Oldham we found a marvelous statue to Annie Kenney. Sculptor Denise Dutton depicted a hatless, stalwart appearing Kenney ringing a bell with one hand to summon people to hear her suffrage message and holding a broadside in the other. Dedicated on Dec 14, 2018, Annie Kenney’s statue is centrally located in a busy plaza next to the Oldham Town Hall. There are benches along one side of the wide base. It is a lovely open space for a striking statue. Yellow and purple flowers were in blossom beside the statue. A bouquet of flowers was carefully placed in front of it.

Next we went in search of the plaque for Annie on the wall of Leesbrook Mill near Oldham where she went to  work in 1893 at the age of ten and lost a finger to a spinning bobbin. The traffic was fearsome and fast and finding a place to park was tricky but we did it! The plaque read: “The workplace of/ ANNIE KENNEY/ of Springfield/1879-1953/Leading suffragette first to be/ imprisoned for direct action, with Christabel/ Pankhurst, 1905/Women gained the full vote/ in 1928.” Annie Kenney was arrested 13 times and suffered multiple force feedings.

work in 1893 at the age of ten and lost a finger to a spinning bobbin. The traffic was fearsome and fast and finding a place to park was tricky but we did it! The plaque read: “The workplace of/ ANNIE KENNEY/ of Springfield/1879-1953/Leading suffragette first to be/ imprisoned for direct action, with Christabel/ Pankhurst, 1905/Women gained the full vote/ in 1928.” Annie Kenney was arrested 13 times and suffered multiple force feedings.

Emmeline Pankhurst

8/14 Manchester, England: Cold and raining when we visited the statue of Emmeline Pankhurst by sculptor Hazel Reeves located in St. Peter’s Square. Officially called “Rise Up Women,” the statue was dedicated on Dec. 14, 2018, the centenary of the first time property owning women over 30 could vote. Reeves depicted Pankhurst in a speaking mode, standing on a rickety-looking chair (not something I imagined Pankhurst would have stood on), with one arm outstretched, palm side up. Her other arm is by her side, palm side up. She is dressed in a coat over a dress. A prisoner badge is pinned to a lace collar. Her large hat, with the brim partly turned up, is decorated with one large flower. I did not feel a particular connection with this statue, although I applaud the fact that there is a statue of a woman in a prominent location.

Erinma Bell

We walked across St. Peter’s Square, to visit the newly renovated Manchester Central Library. I was headed for the information desk but quickly changed course when I spied a bust of Erinma Bell, a peace and anti-gun activist in Manchester. The sculptor, Karen Lyons from Manchester, made Bell’s bust from 50 handguns seized by police or turned in during a gun amnesty (a Guns to Goods Project). A very special piece of art that I am so grateful to now have in my memory.

Astarte by Rossetti

8/15 Curious about whether the Manchester Art Gallery had information about suffragettes’ attack on numerous paintings on April 3, 1913, I asked the young man at the information desk about the incident. He rummaged in a drawer and handed me a 4-page double-side illustrated handout titled “Manchester’s Radical History/Manchester Art Gallery Outrage/The Suffragette Attack on Manchester Art Gallery.” Reluctantly he gave it to me, undoubtedly realizing that I was not going to walk away without it. It was interesting to see the paintings that were attacked, including Astarte Syriaca by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

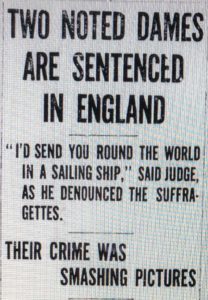

Three women, Annie Briggs, Evelyn Manesta and Lillian Forrester,” staged their attack just before closing, cracking the glass protecting the

From left: Manesta, Forrester, Briggs

biggest and most valuable paintings. Guards soon caught them. Charged under the Malicious Damage Act, 1861, they were tried on April 22. Briggs, who gave support but did not participate in the damage, was acquitted. Manesta was sentenced to one month: “l am a political offender,” she said. Forrester received three months of imprisonment: “I do not stand here as a malicious person,” she told the court, “but as a patriot . . . I have a degree in history and my knowledge of history has spurred me to this fight for women’s freedom.”

The day before their attack Emmeline Pankhurst had been sentenced to three years penal servitude for “inciting persons unknown.” The Manchester Art Gallery incident, plus an attack in which suffragettes poured ink into 11 post boxes damaging 250 letters were in protest of the harsh sentence given to their leader Emmeline Pankhurst.

The British fight for the vote was widely reported in American newspaper. The Manchester  attack made the front page of the Santa Fe New Mexican, Sante Fe, New Mexico, April 23, 1913. “I would send you round the world in a sailing ship if the law permitted it,” Justice Sir John Eldon Bankes told Lillian Forrester and Evelyn Manesta, both “NOTED DAMES.” The American fight was also extensively covered in newspapers. I included numerous newspaper headlines in my book The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight.

attack made the front page of the Santa Fe New Mexican, Sante Fe, New Mexico, April 23, 1913. “I would send you round the world in a sailing ship if the law permitted it,” Justice Sir John Eldon Bankes told Lillian Forrester and Evelyn Manesta, both “NOTED DAMES.” The American fight was also extensively covered in newspapers. I included numerous newspaper headlines in my book The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight.

8/15 I took a deep breath when I saw the large sign—“Visit the Birthplace of the Suffragette Movement.” Within minutes, I was standing on the sidewalk leading to the  front door of Emmeline Pankhurst’s house in Manchester. A blue plaque was high up on the left of the door. A family was exiting after visiting. Our timing was fortuitous because the Pankhurst Centre is only open on Thursday

front door of Emmeline Pankhurst’s house in Manchester. A blue plaque was high up on the left of the door. A family was exiting after visiting. Our timing was fortuitous because the Pankhurst Centre is only open on Thursday  and the 2nd and 4th Sunday, a fact I missed when I planned our route. It was a coincidence that we were in Manchester on a Thursday: Our visit was meant to be!

and the 2nd and 4th Sunday, a fact I missed when I planned our route. It was a coincidence that we were in Manchester on a Thursday: Our visit was meant to be!

Susan Hollick, a thoroughly engaging and informative volunteer, greeted us, holding two gorgeous gladioli that  had fallen over in the garden. She interrupted her search for a vase to talk with us and show us the parlor where Emmeline Pankhurst had founded the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1903 whose members were known as suffragettes, a name coined by a newspaper in an attempt to trivialize the women who boldly appropriated it. As I quietly stood in the parlor, Susan pointed to a hat rack covered with suffragette hats and sashes and said: “Want to dress up?” Linda quickly got out her cell phone to capture the fun.

had fallen over in the garden. She interrupted her search for a vase to talk with us and show us the parlor where Emmeline Pankhurst had founded the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1903 whose members were known as suffragettes, a name coined by a newspaper in an attempt to trivialize the women who boldly appropriated it. As I quietly stood in the parlor, Susan pointed to a hat rack covered with suffragette hats and sashes and said: “Want to dress up?” Linda quickly got out her cell phone to capture the fun.

The Pankhurst women were deeply connected with the American fight for the vote. I wrote about their many influences in my book The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight. Having been immersed in writing about those connections made my visit to the Pankhurst Centre in Manchester particularly special. American women joined the WSPU, participated in events, donated money, and studied their methods, including Alice Paul and Lucy Burns who returned to America to found the National Woman’s Party. Emmeline undertook several extensive speaking tours in America. Her famous “Freedom or Death” speech in Hartford, Connecticut, inspired Katherine Houghton Hepburn to revive the moribund state suffrage movement. Sylvia Pankhurst made two speaking tours that included a stop in North Dakota where her speech inspired women to get organized.

The Vote Road Trip: Day 17 Whitby

Whitby Harbor, River Esk to the North Sea

Whitby Harbor

Whitby Abbey

8/12 Our English friend Leza, who now lives in Brooklyn, urged us to visit to Whitby, a fascinating, beautiful, photogenic town and harbor. We were delighted to discover the stark, imposing remains of Whitby Abbey, standing high on a cliff above the town, that was founded in 647 by a woman— Saint Hilda! Looking west, we can see the North Sea. (Click on a picture to enlarge it.)

There is an in-the-footsteps connection in Whitby, only this time it is non-militant suffragists. In August 1908, after giving a speech at Whitby Harbor, several suffragists set off in a horse-drawn caravan (a rectangular box-shaped vehicle for camping). Their mission was three-fold: display a non-militant image of women seeking the vote, spread the vote for women message to the rural areas, and recruit members. Caravaning was a popular form of recreation at that time and the fact that suffragists joined in was typical of their creativity in seeking enfranchisement, a skill that was also employed in the American fight for the vote.

The sublime view from the window where we had breakfast— the bright green fields are everywhere. It is 54 degrees and no sign of rain. We are now about to drive across the North Yorkshire Moor to Manchester.

The Vote Road Trip Day 15 and 16 Morpeth and Newcastle-Upon-Tyne

Emily Wilding Davison

8/11 The statue of Emily Wilding Davison in Morpeth, a lovely village near the northeast coast of England, is located in a gorgeous park. We visited on a cold rainy day on our way to our next overnight in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, where we are now. It is still raining and in the 60s. (Click on a picture to enlarge it.)

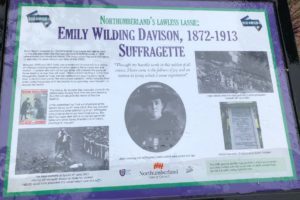

“Northumberland’s Lawless Lassie/Emily Wilding Davison 1872-1913/Suffragette” read the headline on an informative illustrated sign. Davison joined WSPU in 1906 and “fought tirelessly for women’s rights in particular the right to vote.” Arrest ed many times for a variety of offenses—breaking windows, setting fire to a post box, and assault, she was imprisoned and force fed no fewer than 49 times: “The torture was barbaric,” she reported. On June 4, 1913, she ran on to Epsom Race Course and attempted to attach suffrage colors to the bridle on the King’s

ed many times for a variety of offenses—breaking windows, setting fire to a post box, and assault, she was imprisoned and force fed no fewer than 49 times: “The torture was barbaric,” she reported. On June 4, 1913, she ran on to Epsom Race Course and attempted to attach suffrage colors to the bridle on the King’s  horse. Knocked unconscious, she died four days later. Large crowds lined the streets in London and Morpeth to see the carriage carrying her coffin. She once wrote:”Through my humble works in this noblest of all causes, I have come to the fullness of joy and an interest in living which I never experienced.” The statue by Ray Lonsdale, dedicated in 2018, is flanked by a profusion of white and a few dark purple butterfly bushes and purple flowers with the green foliage, the WSPU’s colors. She is shown deliberately dumping her food, knowing that would result in being forcibly fed.

horse. Knocked unconscious, she died four days later. Large crowds lined the streets in London and Morpeth to see the carriage carrying her coffin. She once wrote:”Through my humble works in this noblest of all causes, I have come to the fullness of joy and an interest in living which I never experienced.” The statue by Ray Lonsdale, dedicated in 2018, is flanked by a profusion of white and a few dark purple butterfly bushes and purple flowers with the green foliage, the WSPU’s colors. She is shown deliberately dumping her food, knowing that would result in being forcibly fed.

“Deeds not Words,” WSPU’s motto, is inscribed under Emily Wilding Davison’s name on her family’s obelisk in St. Mary of the Virgin Churchyard, Morpeth. Soon after her death her grave became a pilgrimage site, and continues to be so today.

8/12 Saturday & Sunday in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, in the northeast of England on the north bank of the River Tyne, another hotbed of suffragettes such as Kathleen Brown, whose mother and sister were involved in the great cause. In July 1909, Brown was arrested for throwing stones in London and sentenced to seven days in solitary confinement in Holloway Prison where she undertook a hunger strike and was one of the first women to be force fed. The imprisonment, hunger strikes, and force feeding of American suffragists began in 1917. It was so painful to write about that in my book, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight.

Kathleen Brown was released on July 19 and returned by train to Newcastle where she was greeted by suffragettes and a band. A procession of carriages filled with suffragettes and decorated in purple, white, and green went to the Turk’s Head Hotel for a celebratory tea.

On March 8, 2017, a blue plaque was placed at the former site of Turk’s Head. Although it was raining and cold and we both have colds, Linda and I set off to find it, and, as you see, we did. It read: “Former Turk’s Head  Hotel/Suffragette Movement/Meeting place where suffragettes celebrated the release of Kathleen Brown from Holloway Prison July 19th 1909 and stopped for refreshments on the March from Edinburgh to London, October 21st

Hotel/Suffragette Movement/Meeting place where suffragettes celebrated the release of Kathleen Brown from Holloway Prison July 19th 1909 and stopped for refreshments on the March from Edinburgh to London, October 21st  1912.” In October 1909, at what is known as the Battle of Newcastle, eleven women were arrested, including Brown and Lady Constance Lytton. Lady Lytton was released because she was deemed “unfit” to withstand forced feeding. Although she did have a “weak” heart, her release prompted her to reflect that her upper class status was a more significant factor than her heart, an insight that had lifelong consequences for her that I wrote about in my book The Vote. I am eager to visit a landmark to Lady Lytton on our last stop before returning to London.

1912.” In October 1909, at what is known as the Battle of Newcastle, eleven women were arrested, including Brown and Lady Constance Lytton. Lady Lytton was released because she was deemed “unfit” to withstand forced feeding. Although she did have a “weak” heart, her release prompted her to reflect that her upper class status was a more significant factor than her heart, an insight that had lifelong consequences for her that I wrote about in my book The Vote. I am eager to visit a landmark to Lady Lytton on our last stop before returning to London.

September 13, 2019

The Vote Road Trip Day 14 Edinburgh

Bessie Watson

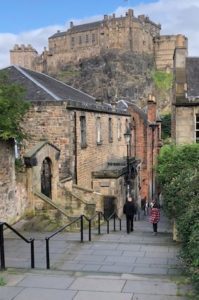

8/9 In Edinburgh,  I had to crane my neck to see the plaque to Elizabeth “Bessie” Watson, a 9-year-old suffragette bagpiper that Linda had finally spotted after we had walked up seemingly endless steps on both sides of the road opposite Edinburgh Castle.

I had to crane my neck to see the plaque to Elizabeth “Bessie” Watson, a 9-year-old suffragette bagpiper that Linda had finally spotted after we had walked up seemingly endless steps on both sides of the road opposite Edinburgh Castle.

In 1909, Bessie and her mother saw an ad for a Great Procession and Women’s Demonstration on October 9th, organized by suffragettes to celebrate “What women have done and can and will do.” Bessie rode on a float and played her pipes. In 1911 she led a contingent of “lady pipers” in the Great Procession in London. When suffragettes were arrested and put on a train to Holloway Prison in London, Bessie stood on the platform and piped. She went to Calton Prison in Edinburgh and piped outside the prison in support of imprisoned suffragettes. The big bows above the plaque are WSPU’s colors: purple, white, and green. Bessie is said to have tied her pigtails with purple, white, and green ribbons.

Dedicated on August 1, 2019 Bessie Watson’s plaque is at the top of the wall near where her childhood house once stood, high above the heads of pedestrians, unless they are looking for it and are as sharp-eyed as Linda! (Click on a picture to enlarge it.)

August 15, 1964–55 years ago—was my first and only visit to Edinburgh. After two years of college, I got a six-week job as an assembly line worker in a frozen food factory in Helsingborg, Sweden, bought a one-way ticket on a student ship going to Southampton, England, packed a blue & white seersucker dress, underwear, and socks in a small backpack, got my passport and international youth hostel card, and took a small amount of money. Wearing a denim skirt, white blouse, and hiking boots, I boarded the M/S Aurelia in July 24th. (My mother was apoplectic & furious I wasn’t college bound. My father was thrilled that I was living out one of his fantasies.) From Southampton, I went to London, then took a train to Holyhead and a boat to Dublin, Ireland. I hitchhiked to Belfast and took the boat to Glasgow where at the youth hostel I met Loreen and Jean from New Zealand. Together we hitchhiked the long way to Edinburgh, getting rides in—a lorry carrying Ballantine whiskey to Dumbarton; a Ferrocrete lorry to Fort Williams (We talked through the night with the driver, although his Glaswegian accent was hard to decipher.); a lorry to Loch Ness; a newspaper truck to Inverness; a lorry loaded with 15-tons of granite to Kintore, a hay truck into Aberdeen, a car to Dundee, and a series of short rides in cars to Edinburgh. Amazingly the Women’s Youth Hostel I stayed in was beside The Vennel, the steps, that Linda and I walked up to find Bessie Watson’s plaque! Across the square were  the steps I took, all those many years ago, to get to the castle esplanade to watch The Royal Military Tattoo. (The first steps Linda and I had tried.)

the steps I took, all those many years ago, to get to the castle esplanade to watch The Royal Military Tattoo. (The first steps Linda and I had tried.)

We got last-minute tickets to the Tattoo, a much greater event than  what I saw in 1964. We saw military bands, singers, and dancers from Nigeria, China, Germany, France, Australia, New Zealand, and a steel drum military band from Trinidad and Tobago; Welsh fiddlers and Scottish dancers; and marching bagpipers galore! Each was introduced by a narrator who provided a wonderful sense of diversity and non-militarism. It was a dignified spectacle, topped off with fireworks shot off from the Edinburgh Castle. We didn’t even mind the rain storm that now seems a daily occurrence in Scotland. The Tattoo proudly endures every weather condition.

what I saw in 1964. We saw military bands, singers, and dancers from Nigeria, China, Germany, France, Australia, New Zealand, and a steel drum military band from Trinidad and Tobago; Welsh fiddlers and Scottish dancers; and marching bagpipers galore! Each was introduced by a narrator who provided a wonderful sense of diversity and non-militarism. It was a dignified spectacle, topped off with fireworks shot off from the Edinburgh Castle. We didn’t even mind the rain storm that now seems a daily occurrence in Scotland. The Tattoo proudly endures every weather condition.

Penny Colman's Blog

- Penny Colman's profile

- 10 followers