Penny Colman's Blog, page 3

December 10, 2019

Epigraphs: “The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight,” Part IV, Chapter 12

This statement by Anna Howard Shaw is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 12, Battle Cry: 1916—We have waited long enough.

In writing these posts, I am focusing on events that relate to the epigraph, although there is so much more in each chapter. Anna Howard Shaw directed her words—We have waited  long enough—to an intransigent President Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat who refused to mobilize members of his party, which was in control of Congress, to pass a women’s suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. (The first federal woman suffrage amendment resolution was introduced in Congress in 1868, and the second one in 1878, with wording that would remain unchanged until it was finally adopted in 1920!)

long enough—to an intransigent President Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat who refused to mobilize members of his party, which was in control of Congress, to pass a women’s suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. (The first federal woman suffrage amendment resolution was introduced in Congress in 1868, and the second one in 1878, with wording that would remain unchanged until it was finally adopted in 1920!)

The occasion of Shaw’s salvo was the 1916 Emergency Convention of the National  American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), presided over by Carrie Chapman Catt. (Shaw retired in 1915, as honorary president.) In her presidential address Catt issued a clarion call—DEMAND THE VOTE! WOMEN ARISE! She presented her strategy for victory dubbed “The Winning Plan” in a secret meeting with national officers and state

American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), presided over by Carrie Chapman Catt. (Shaw retired in 1915, as honorary president.) In her presidential address Catt issued a clarion call—DEMAND THE VOTE! WOMEN ARISE! She presented her strategy for victory dubbed “The Winning Plan” in a secret meeting with national officers and state  presidents who vowed to conduct a “red-hot, never-ceasing campaign.” Catt had invited President Wilson, who was running for reelection, to address the delegates on the fifth day of the convention. He arrived, looking dapper in white shoes, pants, shirt, and tie, topped by a dark blazer. His entourage included his wife, whose secretary had called Catt, inquiring as to the proper attire. Catt assured her that there was no set standard. Edith Wilson arrived wearing a white dress, a hat with a single feather plume, and a luxurious white fox stole, complete with the fox’s head and tail, over her coat.

presidents who vowed to conduct a “red-hot, never-ceasing campaign.” Catt had invited President Wilson, who was running for reelection, to address the delegates on the fifth day of the convention. He arrived, looking dapper in white shoes, pants, shirt, and tie, topped by a dark blazer. His entourage included his wife, whose secretary had called Catt, inquiring as to the proper attire. Catt assured her that there was no set standard. Edith Wilson arrived wearing a white dress, a hat with a single feather plume, and a luxurious white fox stole, complete with the fox’s head and tail, over her coat.

The audience greeted him with applause and cheers. Making no promises, Wilson cautioned patience, saying—”you can afford a little while to wait.” He finished and sat down. Rising to her feet, Anna  Howard Shaw, a legendary orator, pointedly replied: “We have waited long enough for the vote, we want it now and we want it to come in your administration!”

Howard Shaw, a legendary orator, pointedly replied: “We have waited long enough for the vote, we want it now and we want it to come in your administration!”

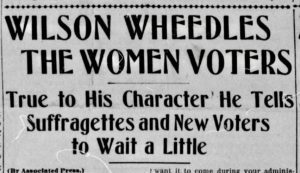

The top image is a statue of Anna Howard Shaw, located in Anna Howard Shaw Memorial Park, Big Rapids, Michigan. It is inscribed with her words: Nothing bigger can come to a human being than to love a great cause more than life itself. The middle, left image is Carrie Chapman Catt. The middle right image is Shaw, who was an ordained minister and medical doctor before becoming a full-time suffragist, and Catt, dressed to march in a suffrage parade. The bottom image is the headline for an article about Wilson’s appearance that appeared in a Tonopah, Nevada newspaper, the Tonopah Daily Bonaza, September 9, 1916. (Newspaper varied in the terms used for suffragists, including “Suffs” and “suffragettes,” the British term for militant fighters for the vote.)

Male voters defeated three woman suffrage amendment referenda in 1916: Iowa and West Virginia for the first time, and South Dakota for the sixth time! In Montana Jeannette Rankin won the election for a seat in the House of Representative, becoming the first woman to serve in U. S. Congress. Wilson was reelected as president of the U.S.

Chapter 12 includes many other events, including the death of and dramatic memorial service for Inez Milholland. The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is widely available in trade paperback and eBook. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

December 9, 2019

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight Part IV, Chapter 11

This statement by Gertrude Watkins is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part IV, Chapter 11, Undauntable Suffragists: 1915—Getting about a million ideas.

This statement by Gertrude Watkins is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part IV, Chapter 11, Undauntable Suffragists: 1915—Getting about a million ideas.

I started writing The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight during the 2016 presidential campaign. Immersed in the relentless, implacable, treacherous opposition to women’s participation in the goverance of the country, I became increasingly doubtful that a woman would/could be elected president of the United States. Writing about women’s fierce fight for the vote in 1915 quadrupled my doubtfulness. Four colossal campaigns for woman suffrage referenda were underway in large eastern states—New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New York. The stakes were high; suffragists believed that a victory in a large Eastern state would cause a cascade of victories elsewhere, even in resistant Southern states.

Suffragists across America joined the campaigns. The “Arkansas Flying Squadron,” three women from Little Rock, went to New York City to help and to get “suffragistically educated.” Gertrude Watkins (top image) was excited about “getting about a million ideas to take back” to Arkansas. Katherine Wentworth Ruschenberger, of Pennsylvania, financed the making of the Women’s Liberty  Bell, also call the Justice Bell, (second image) a one-ton copy of the iconic Liberty Bell without the crack and with the words “establish justice” added to the inscription. Tugboats with suffragists from New York and New Jersey met in the middle of the Hudson River to exchange

Bell, also call the Justice Bell, (second image) a one-ton copy of the iconic Liberty Bell without the crack and with the words “establish justice” added to the inscription. Tugboats with suffragists from New York and New Jersey met in the middle of the Hudson River to exchange  the Liberty Torch (third image.) On July 15, “Suffrage Blue Bird Day,” suffragists in Massachusetts tacked up 100,000 twelve-by-four inch brightly painted tin blue birds on telephone poles and

the Liberty Torch (third image.) On July 15, “Suffrage Blue Bird Day,” suffragists in Massachusetts tacked up 100,000 twelve-by-four inch brightly painted tin blue birds on telephone poles and  fences (fourth image.)

fences (fourth image.)

What were the results of the financially, emotionally, and physically costly campaigns? Male voters in all four states overwhelmingly refused to enfranchise women. Suffragists, undauntable suffragists, kept on keeping on, as, I realized, must I. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight now available in trade paperback and eBook.

December 8, 2019

Sophie Grammy Update

For those of you who followed my Sophie/Grammy Day posts, Sophie turned 16 today!! L-R bottom: David, Balan, Nickie, Archer, Sophie, Quinn, Raven; L-R top: Penny, Granger, Ursula, Linda, Jon, Stephen, Katrin (Click on image to enlarge it.)

December 7, 2019

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part IV, Chapter 10

This statement by Jessie Hardy Stubbs is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part IV, Chapter 10, Hard-Fought Campaigns: 1914—Here we are—all bound for the field of battle.

This statement by Jessie Hardy Stubbs is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part IV, Chapter 10, Hard-Fought Campaigns: 1914—Here we are—all bound for the field of battle.

Top image is Jessie Hardy Stubbs, a prominent suffragist and peace advocate, wearing “short-brimmed hat, gloves, plaid suit with sailor-style blouse and necktie, carrying briefcase under left arm.” In August 1914 at a meeting of the Congressional Union’s Advisory Committee in Newport at Alva Belmont’s mansion, over which flew the purple, white and gold banners, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns proposed a pioneering and controversial tactic. Since, the United States Congress and the presidency were under Democratic control, reasoned Alice Paul, the Democratic Party was “responsible for the non-passage” of a federal woman suffrage amendment. The question, she said, was “how shall the enemy be attacked?” The answer was to send fifteen organizers to the “field of battle”—the nine equal suffrage states with four million women voters (Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Washington, California, Arizona, Kansas, Oregon) where they would campaign against every Democratic candidate, even pro-suffrage ones on the ballot in the November election. WAR ON CONGRESSMEN, trumpeted a headline in a Washington, D.C. newspaper. Jessie Hardy Stubbs and Virginia Arnold were assigned to Oregon: Here we are—all bound for the field of battle, Stubbs reported from on board the North Coast Limited. We have put up signs in each car that there will be a meeting tonight in the observation car. Media-savvy Alice Paul provided press releases and photographs such as the middle image that appeared in various newspapers, including The Rock Island  Argus, Rock Island, Illinois, Sept. 18, 1915. (L to R: six of the fifteen organizers—Rose Winslow, Lucy Burns, Doris Stevens, Ruth Ann Noyes, Anna McCue, Jane Pincus, Jessie Hardy Stubbs.)

Argus, Rock Island, Illinois, Sept. 18, 1915. (L to R: six of the fifteen organizers—Rose Winslow, Lucy Burns, Doris Stevens, Ruth Ann Noyes, Anna McCue, Jane Pincus, Jessie Hardy Stubbs.)

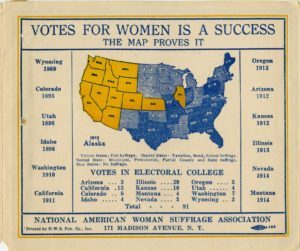

In 1914, suffragists launched all-out campaigns in a record number of seven states with a wo man suffrage amendment referendum on the ballot. In the November election, male voters racked up five defeats and two victories (Women’s Fierce Fight, indeed!) Suffrage maps were produced and distributed to educate and persuade people. The one shown on the left is from 1914. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

man suffrage amendment referendum on the ballot. In the November election, male voters racked up five defeats and two victories (Women’s Fierce Fight, indeed!) Suffrage maps were produced and distributed to educate and persuade people. The one shown on the left is from 1914. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in trade paperback and eBook.

December 5, 2019

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part III, Chapter 9

This statement by a suffrage marcher is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 9, Breakthrough: 1913 Girls, get out your hatpins, they are going to rush us.

There are two breakthroughs in Chapter 9. The cliff-hanging passage of the Presidential and Municipal Suffrage Act in Illinois was an outstanding victory: A non-western state east of the Mississippi River had granted more than a sliver of voting rights to women. The right of vote for presidential electors gave Illinois women voting power on a national level.  Suffragists across the country added what became known as “The Illinois Bill” to their arsenal of tactics in the fight for the vote. The Illinois campaign fierce fight was led by Grace Wilbur Trout, president of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association, whose recently deceased son had exhorted her when her energy had flagged— “you can do a work that no one else can do.”

Suffragists across the country added what became known as “The Illinois Bill” to their arsenal of tactics in the fight for the vote. The Illinois campaign fierce fight was led by Grace Wilbur Trout, president of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association, whose recently deceased son had exhorted her when her energy had flagged— “you can do a work that no one else can do.”

The second breakthrough was a spectacular parade and pageant in Washington, D.C. on March 3, 1913. An estimated 5,000 to 8,000 women from every state and many countries marched. Across America, newspapers covered the dramatic event. WOMEN IN MAMMOUTH SHOW declared the front-page headline in an Hawaiian newspaper, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 3, 1913.  A line of Boy Scouts and some male college students along the march did their best to restrain men determined to disrupt the parade. But, they were overwhelmed while many police officers stood idly by. Rampaging men blocked the parade, forcing marchers to fight their way through. A girl on a float was grabbed and kicked in the face. Women were spat on and manhandled. Men shouted ribald jeers and vile insults. Suffragists on horseback, including Inez Milholland, bravely rode into the mob, pushing it back to the

A line of Boy Scouts and some male college students along the march did their best to restrain men determined to disrupt the parade. But, they were overwhelmed while many police officers stood idly by. Rampaging men blocked the parade, forcing marchers to fight their way through. A girl on a float was grabbed and kicked in the face. Women were spat on and manhandled. Men shouted ribald jeers and vile insults. Suffragists on horseback, including Inez Milholland, bravely rode into the mob, pushing it back to the  sidewalk. Confronted by a menacing line of twenty men with their arms locked, a young woman, who “was really terrified,” braced herself and shouted: “Girls, get out your hatpins, they are going to rush us.” The men backed off.

sidewalk. Confronted by a menacing line of twenty men with their arms locked, a young woman, who “was really terrified,” braced herself and shouted: “Girls, get out your hatpins, they are going to rush us.” The men backed off.

The top image is a picture that appeared in newspapers across America—the signing ceremony by Governor Edward Dunne of Illinois of the Presidential and Municipal Suffrage Act. The caption begins: “This picture is a part of the suffragist history of America.” (The image appeared in The Bridgeport Evening Farmer, Bridgeport, Connecticut, July 2, 1913, 11.) Grace Wilbur Trout is standing above the seated woman. She is flanked by co-leaders in the campaign Antoinette Funk (on her right) and Elizabeth Booth. (The number above each person matches the numbered name in the caption.) The middle image is a float in the Washington, D.C. parade carrying a sign printed with “The Great Demand,” an iconic suffrage statement—WE DEMAND AN/AMENDMENT TO THE/CONSTITUTION OF THE/UNITED STATES/ENFRANCHISING THE/WOMEN OF THIS COUNTRY. The bottom image is a front-page article from The Washington Herald, Washington, D.C., March 3, 1913. The violent treatment of the women, according to Grace Trout, “aroused the indignation of the whole nation and converted many men to the suffrage cause.” (Click on each image to enlarge it.)

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is widely available in trade paperback and eBook.

December 4, 2019

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part III, Chapter 8

This statement by Inez Milholland is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight,  Chapter 8: Right is Might: 1912 I will never get cold in a cause like this.

Chapter 8: Right is Might: 1912 I will never get cold in a cause like this.

In 1912, suffragists scored record-setting victories in woman suffrage amendment referenda—four new equal suffrage states: Arizona, Kansas (two previous defeats), Oregon (five previous defeats), and Michigan (one previous defeat), although the Michigan’s results were not yet final. (Referenda in Ohio and Wisconsin had been defeated; as would be Michigan’s by 762 votes amidst charges of fraud and trickery.)

Across America suffragists celebrated. In New York City, on November 9, a chilly, Saturday night, 20,000 women and girls and several thousand men and boys marched up Fifth Avenue, dazzling the 400,000 spectators with a “river of fire.” The “river of fire” was created by a novelty imported from Paris, France, that hung from a pole—an orange pumpkin-shaped lantern with a single light bulb inside that was attached to a battery that a marcher carried in a pocket. Ten charioteers, including Inez Milholland, drove snow-white horses that pulled a chariot, one for each of the ten equal-suffrage states. When a reporter asked Milholland, an eloquent and tireless suffragist, whether her flimsy charioteer costume kept her warm enough, she replied, “I will never get cold in a cause such as this.”

Inez Milholland was a lawyer who fought for working women’s rights, and a charismatic suffrage speaker, who newspapers covered with headlines such as MANY TURN OUT TO  HEAR THE BEAUTY. A skilled equestrian, she participated in many suffrage parades. She appears several more time in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight until her death at the age of thirty while on an intense speaking tour in 1916.

HEAR THE BEAUTY. A skilled equestrian, she participated in many suffrage parades. She appears several more time in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight until her death at the age of thirty while on an intense speaking tour in 1916.

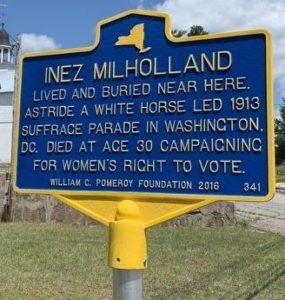

The first image is Inez Milholland, a student at Vassar College. Next is an image of her mounted on Gray Dawn, a white charger, prepared to lead the 1913 grand “Woman Suffrage Procession” in Washington, D.C. on March 3, 1913. The bottom image is a historic marker dedicated in  2016 in Lewis, New York, near where Inez Milholland lived and is buried. Carl Sandburg’s poem, “Repetitions” honors Inez Milholland: “They are crying salt tears/Over the beautiful beloved body/Of Inez Milholland/Because they are glad she lived,/Because she loved open-armed,/Throwing love for a cheap thing/Belonging to everybody—/Cheap as sunlight,/And morning air.” (Click on images to enlarge them.)

2016 in Lewis, New York, near where Inez Milholland lived and is buried. Carl Sandburg’s poem, “Repetitions” honors Inez Milholland: “They are crying salt tears/Over the beautiful beloved body/Of Inez Milholland/Because they are glad she lived,/Because she loved open-armed,/Throwing love for a cheap thing/Belonging to everybody—/Cheap as sunlight,/And morning air.” (Click on images to enlarge them.)

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is widely available in trade paperback and eBook. There are links on my website http://www.pennycolman.com

December 3, 2019

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part III, Chapter 7

This statement by Madame Lillian Nordica is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 7: A Whirlwind From shore to shore let rights be flashed

My parents passed their love for opera on to me so I was delighted to discover Madame Lillian Nordica’s role in the 1911 woman suffrage referendum in California. Male voters had soundly defeated the California Women’s Suffrage Amendment in an 1896 referendum. In 1911, suffragists launched a “whirlwind campaign.” Veterans of the losing 1896 campaign and new recruits, and suffragists from across America seized their task with “unbounded enthusiasm.” As, did the opposition.

A special election was scheduled for October 10. At noon, on October 9, suffragists were  galvanized by the news that the world-renowned opera singer Madame Lillian Nordica, who was in San Francisco to sing at the groundbreaking for the Panama Celebration, would appear in support of woman suffrage that night in Union Square. By seven o’clock, thousands of people filled the square and jammed the streets. A band played. Suffragists gave speeches standing in automobiles stationed around the square. Madame Nordica arrived at nine o’clock riding in an automobile decorated with garlands of oak leaves, giant yellow chrysanthemums, “Votes for Women” pennants, and a white blanket embroidered in yellow draped over the front. An elegant, gracious woman, Madame Nordica gave a short speech, and sang “America the Beautiful,” changing a phrase to “From shore to shore let rights be flashed.” Then, she sang “The Star-Spangled Banner,” asking the crowd to sing with her.

galvanized by the news that the world-renowned opera singer Madame Lillian Nordica, who was in San Francisco to sing at the groundbreaking for the Panama Celebration, would appear in support of woman suffrage that night in Union Square. By seven o’clock, thousands of people filled the square and jammed the streets. A band played. Suffragists gave speeches standing in automobiles stationed around the square. Madame Nordica arrived at nine o’clock riding in an automobile decorated with garlands of oak leaves, giant yellow chrysanthemums, “Votes for Women” pennants, and a white blanket embroidered in yellow draped over the front. An elegant, gracious woman, Madame Nordica gave a short speech, and sang “America the Beautiful,” changing a phrase to “From shore to shore let rights be flashed.” Then, she sang “The Star-Spangled Banner,” asking the crowd to sing with her.

The next day, Election Day, a large photograph and an article headlined: DIVA SINGS  FOR SUFFRAGE, appeared on the front page of The San Francisco Call. The vote was so close that newspapers across the country reported that the amendment had been defeated. Only The San Francisco Call held out hope, predicting that the amendment would pass by 4,000 votes. Male voters approved the California Women’s Suffrage Proposition by a majority of 3,587 votes, making California equal-suffrage state number six!

FOR SUFFRAGE, appeared on the front page of The San Francisco Call. The vote was so close that newspapers across the country reported that the amendment had been defeated. Only The San Francisco Call held out hope, predicting that the amendment would pass by 4,000 votes. Male voters approved the California Women’s Suffrage Proposition by a majority of 3,587 votes, making California equal-suffrage state number six!

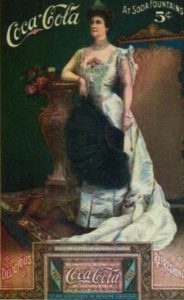

The top image is an advertisement for Coca Cola featuring Madame Nordica. The middle image is the front page article in The San Francisco Call, October 10, 1911. The bottom image is the Nordica Homestead Museum in Farmington, Maine. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

The top image is an advertisement for Coca Cola featuring Madame Nordica. The middle image is the front page article in The San Francisco Call, October 10, 1911. The bottom image is the Nordica Homestead Museum in Farmington, Maine. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

December 2, 2019

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part II, Chapter 6

This statement by Alva Belmont is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part II, Chapter 6, Radical Change: 1909-1910: I was exalted.

This statement by Alva Belmont is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part II, Chapter 6, Radical Change: 1909-1910: I was exalted.

Alva Erskine Smith Vanderbilt Belmont had acquired great wealth by defying social norms and divorcing her philandering first husband William Vanderbilt. In the spring of 1909, she was in London as the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s delegate to the International Woman Suffrage Association convention. While there, she attended an event where Emmeline Pankhurst and six other suffragettes who had just been released from prison were awarded the Holloway Prison Medal. “Such electric fervor I had never see nor felt in all my experience,” Belmont later wrote, “I was exalted.”

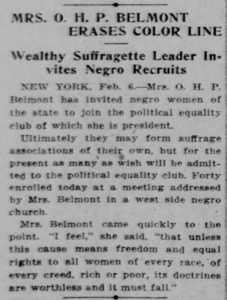

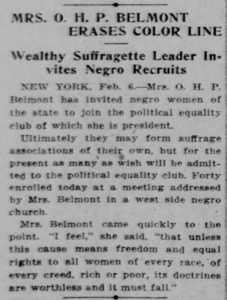

She returned home “invigorated and determined to enliven the fight for the vote.” In the fall of 1909, she founded the Political Equality Association (PEA) in New York City with branch offices in various locations where working women could attend suffrage lectures. Wanting to include black women in PEA, Alva Belmont met with several prominent black women and arranged a meeting at a black church. She told the gathering—”I feel that unless this cause means freedom and equal rights to all women, of every race, of every creed, rich or poor, its doctrines are worthless and it must fail.” Newspapers around the country noted the event. INVITES NEGROES TO JOIN read the headline in a Topeka, Kansas, newspaper, The Topeka Daily State Journal, February 7, 1910.

The top image labeled “Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont” illustrated an article about Belmont founding PEA in a Grand Fork, North Dakota, newspaper, The Evening Times, November 3, 1909. (The O. H. P. are the initials of her deceased, wealthy second husband’s name, Oliver Hazard Perry.) The middle image is a newspaper article headlined MRS. O. H. P. BELMONT ERASES COLOR LINE that appeared on the front page of The San Francisco Call, February 6, 1910. The bottom image of a film crew in a mausoleum dates back to 1995 and a television special, “Honoring American Heroines,” about my photography of women’s graves. (A three  minute video of “Honoring American Heroines” is on my website under Podcasts & Videos.)

minute video of “Honoring American Heroines” is on my website under Podcasts & Videos.)

I had read that Alva Belmont had been buried in the magnificent Belmont mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York City with a purple, white, and gold banner of the National Woman’s Party. To satisfy my intense curiosity, the producer convinced the director of Woodlawn to open the mausoleum for the first time since Alva Belmont’s burial in 1933. It was a sacred experience to walk into the beautiful interior and see, abeit, faded and frayed, the banner of women’s fierce fight at the head of Alva Belmont’s marble catafalque. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

Epigraphs: The Vote, Chapter 6

This statement by Alva Belmont is the epigraph for Chapter 6 Radical Change: 1909-1910: I was exalted.

This statement by Alva Belmont is the epigraph for Chapter 6 Radical Change: 1909-1910: I was exalted.

Alva Erskine Smith Vanderbilt Belmont had acquired great wealth by defying social norms and divorcing her philandering first husband William Vanderbilt. In the spring of 1909, she was in London as the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s delegate to the International Woman Suffrage Association convention. While there, she attended an event where Emmeline Pankhurst and six other suffragettes who had just been released from prison were awarded the Holloway Prison Medal. “Such electric fervor I had never see nor felt in all my experience,” Belmont later wrote, “I was exalted.”

She returned home “invigorated and determined to enliven the fight for the vote.” In the fall of 1909, she founded the Political Equality Association (PEA) in New York City with branch offices in various locations where working women could attend suffrage lectures. Wanting to include black women in PEA, Alva Belmont met with several prominent black women and arranged a meeting at a black church. She told the gathering—”I feel that unless this cause means freedom and equal rights to all women, of every race, of every creed, rich or poor, its doctrines are worthless and it must fail.” Newspapers around the country noted the event. INVITES NEGROES TO JOIN read the headline in a Topeka, Kansas, newspaper, The Topeka Daily State Journal, February 7, 1910.

The top image labeled “Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont” illustrated an article about Belmont founding PEA in a Grand Fork, North Dakota, newspaper, The Evening Times, November 3, 1909. (The O. H. P. are the initials of her deceased, wealthy second husband’s name, Oliver Hazard Perry.) The middle image is a newspaper article headlined MRS. O. H. P. BELMONT ERASES COLOR LINE that appeared on the front page of The San Francisco Call, February 6, 1910. The bottom image of a film crew in a mausoleum dates back to 1995 and a television special, “Honoring American Heroines,” about my photography of women’s graves. (A three  minute video of “Honoring American Heroines” is on my website under Podcasts & Videos.)

minute video of “Honoring American Heroines” is on my website under Podcasts & Videos.)

I had read that Alva Belmont had been buried in the magnificent Belmont mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York City with a purple, white, and gold banner of the National Woman’s Party. To satisfy my intense curiosity, the producer convinced the director of Woodlawn to open the mausoleum for the first time since Alva Belmont’s burial in 1933. It was a sacred experience to walk into the beautiful interior and see, abeit, faded and frayed, the banner of women’s fierce fight at the head of Alva Belmont’s marble catafalque. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

December 1, 2019

Epigraphs: The Vote Chapter 5

This statement by Rose Schneiderman is the epigraph for Chapter 5 Stir Things Up: 1907-1909: The time has come.

Twenty-six-year-old Rose Schneiderman enters The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight in 1908—”That spring, Maud Malone teamed up with Harriot Stanton Blatch to conduct a tour of open-air meetings in upstate New York. Traveling by trolley, they started the tour in Seneca Falls, Blatch’s hometown and the site of the women’s rights convention organized by her mother in 1848. Vassar College, Blatch’s alma mater, in Poughkeepsie, New York, was their last stop. Vassar’s anti-suffrage president banned suffrage events. Not to be deterred, Inez Milholland, an activist student, proposed meeting in the Roman Catholic cemetery that bordered the north side of the campus. A tall, spirited, smart, and athletic woman, Inez Milholland grew up in a socially engaged, wealthy family. She had spent the previous summer participating with suffragettes in London. A good-sized group of students, alumnae, and local suffragists showed up at the cemetery, some climbing over the fence, others using a gate. It was a pleasant day in early June, so they sat in a circle on the grass. Instead of a yellow ‘Votes for Women’ banner, Blatch displayed one inscribed: ‘Come, let us reason together’ (perhaps in case the president showed up.)

Rose Schneiderman, a prominent member of Blatch’s Equality League, came from New York City to speak, arriving late, having missed the ‘fast mail train.’ She discussed trade unionism and ‘got fully twice as much applause as any of the rest. A Jewish Polish immigrant, Rose Schneiderman was less than five feet tall with wavy red hair. She started working at the age of thirteen to support her widowed mother and siblings. In time, she became a skilled caps and hats lining-maker . . . . An electrifying orator, she fiercely advocated trade unionism, vividly evoked working

Rose Schneiderman, a prominent member of Blatch’s Equality League, came from New York City to speak, arriving late, having missed the ‘fast mail train.’ She discussed trade unionism and ‘got fully twice as much applause as any of the rest. A Jewish Polish immigrant, Rose Schneiderman was less than five feet tall with wavy red hair. She started working at the age of thirteen to support her widowed mother and siblings. In time, she became a skilled caps and hats lining-maker . . . . An electrifying orator, she fiercely advocated trade unionism, vividly evoked working  women’s lives of hardship and exploitation, and persuasively connected the vote with the power to improve working conditions. At a convention of women trade unionists, Schneiderman declared: ‘The time has come when working women of the State of New York must be enfranchised and so secure political power to shape their own labor conditions.” The top image is Rose Schneiderman. The bottom image is the top half of the article that appeared in a New York City newspaper, The Sun, June 9, 1908, p. 3. The headline read: VASSAR MEETS IN GRAVEYARD/COLLEGE GIRLS HOLD SUFFRAGE POWWOW IN A CEMETERY. (Click on images to enlarge.)

women’s lives of hardship and exploitation, and persuasively connected the vote with the power to improve working conditions. At a convention of women trade unionists, Schneiderman declared: ‘The time has come when working women of the State of New York must be enfranchised and so secure political power to shape their own labor conditions.” The top image is Rose Schneiderman. The bottom image is the top half of the article that appeared in a New York City newspaper, The Sun, June 9, 1908, p. 3. The headline read: VASSAR MEETS IN GRAVEYARD/COLLEGE GIRLS HOLD SUFFRAGE POWWOW IN A CEMETERY. (Click on images to enlarge.)

Penny Colman's Blog

- Penny Colman's profile

- 10 followers