Penny Colman's Blog, page 4

November 26, 2019

Epigraphs: Chpt 4, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight

This statement by Charlotte Perkins Gilman is the epigraph for Part II Chapter 4 Persevere: 1900-1906: Work, each of you, with all your heart.

Some years ago, I included Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s well-known short story The Yellow Wallpaper and her classic nonfiction book Women and Economics in a course, Feminist Perspectives in Literature, that I taught at Teachers College, Columbia University. Gilman, a feminist, sociologist, lecturer, author, and prominent suffragist also wrote trenchant, witty suffrage poems. In The  Vote, I tell the story of Susan B. Anthony’s meeting with Eugene V. Debs, the renowned labor leader and socialist, and Gilman’s poem “The Socialist and the Suffragists.” In another of her poems, “The Anti-Suffragists,” Charlotte Perkins Gilman described six types of anti-suffrage women in “The Anti-Suffragists.” Here is the excerpt from my book: Fashionable women in luxurious homes . . . . Successful women who have won their way . . . . Religious women of the feebler sort . . . . Ignorant women—college bred sometimes . . . And selfish women—pigs in petticoats . . . . And, more’s the pity, some good women too . . . .These tell us they have all the rights they want.

Vote, I tell the story of Susan B. Anthony’s meeting with Eugene V. Debs, the renowned labor leader and socialist, and Gilman’s poem “The Socialist and the Suffragists.” In another of her poems, “The Anti-Suffragists,” Charlotte Perkins Gilman described six types of anti-suffrage women in “The Anti-Suffragists.” Here is the excerpt from my book: Fashionable women in luxurious homes . . . . Successful women who have won their way . . . . Religious women of the feebler sort . . . . Ignorant women—college bred sometimes . . . And selfish women—pigs in petticoats . . . . And, more’s the pity, some good women too . . . .These tell us they have all the rights they want.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman is just one of the many fascinating known and little known women I write about in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight. The top image is the cover of Suffrage Songs and Verses by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. The bottom image is Gilman standing on the back seat of an automobile, giving a suffrage speech. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

November 24, 2019

Epigraphs: Chpt 3, The Vote Women’s Fierce Fight

This statement by Anna Julia Cooper is the epigraph for Chapter 3 Gain Momentum: 1878-1900: “We take our stand on the solidarity of humanity.”

Anna Julia Cooper, who earned a Ph.D. from the Sorbonne, was a member of the first Black sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, established by college women at Howard University, Washington, D.C., in 1908. Throughout her long life—she lived to be 105—Anna Julia Cooper made many contributions as a teacher, sociologist, speaker, an d author. Her first book A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South published in 1892 is considered one of the first expressions of black feminism. I wrote about Anna Julia Cooper in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight and the activism of black women who “steadfastly fought for the right to vote. Black women from Rhode Island to Louisiana to North Dakota organized local suffrage clubs across the country . . . .Other black women organized and spoke out on the national level . . . The preeminent educator, writer, and orator Anna Julia Cooper, who had been born the daughter of a slave and her white master, declared at the World’s Congress of Representative Women in 1893: ‘We take our stand on the solidarity of humanity.’”

d author. Her first book A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South published in 1892 is considered one of the first expressions of black feminism. I wrote about Anna Julia Cooper in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight and the activism of black women who “steadfastly fought for the right to vote. Black women from Rhode Island to Louisiana to North Dakota organized local suffrage clubs across the country . . . .Other black women organized and spoke out on the national level . . . The preeminent educator, writer, and orator Anna Julia Cooper, who had been born the daughter of a slave and her white master, declared at the World’s Congress of Representative Women in 1893: ‘We take our stand on the solidarity of humanity.’”

I was delighted when I discovered a quote by Cooper printed in my American passport (the only woman quoted along with seven men and several documents): “The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a part or a class—it the cause of humankind, the very birthright of humanity.”

The top image is the 44 cent United States Black Heritage postage stamp honoring Anna Julia Cooper that was issued in 2009.The bottom image is a historic marker located in LeDroit Park, Washington, D.C.: the Anna Julia Hayward Cooper Residence Marker, with a picture of her on her porch. (photo by Devry Jones).

The top image is the 44 cent United States Black Heritage postage stamp honoring Anna Julia Cooper that was issued in 2009.The bottom image is a historic marker located in LeDroit Park, Washington, D.C.: the Anna Julia Hayward Cooper Residence Marker, with a picture of her on her porch. (photo by Devry Jones).

Epigraphs: The Vote Chapter 3

This statement by Anna Julia Cooper is the epigraph for Chapter 3 Gain Momentum: 1878-1900: “We take our stand on the solidarity of humanity.”

Anna Julia Cooper, who earned a Ph.D. from the Sorbonne, was a member of the first Black sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, established by college women at Howard University, Washington, D.C., in 1908. Throughout her long life—she lived to be 105—Anna Julia Cooper made many contributions as a teacher, sociologist, speaker, an d author. Her first book A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South published in 1892 is considered one of the first expressions of black feminism. I wrote about Anna Julia Cooper in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight and the activism of black women who “steadfastly fought for the right to vote. Black women from Rhode Island to Louisiana to North Dakota organized local suffrage clubs across the country . . . .Other black women organized and spoke out on the national level . . . The preeminent educator, writer, and orator Anna Julia Cooper, who had been born the daughter of a slave and her white master, declared at the World’s Congress of Representative Women in 1893: ‘We take our stand on the solidarity of humanity.’”

d author. Her first book A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South published in 1892 is considered one of the first expressions of black feminism. I wrote about Anna Julia Cooper in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight and the activism of black women who “steadfastly fought for the right to vote. Black women from Rhode Island to Louisiana to North Dakota organized local suffrage clubs across the country . . . .Other black women organized and spoke out on the national level . . . The preeminent educator, writer, and orator Anna Julia Cooper, who had been born the daughter of a slave and her white master, declared at the World’s Congress of Representative Women in 1893: ‘We take our stand on the solidarity of humanity.’”

I was delighted when I discovered a quote by Cooper printed in my American passport (the only woman quoted along with seven men and several documents): “The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a part or a class—it the cause of humankind, the very birthright of humanity.”

The top image is the 44 cent United States Black Heritage postage stamp honoring Anna Julia Cooper that was issued in 2009.The bottom image is a historic marker located in LeDroit Park, Washington, D.C.: the Anna Julia Hayward Cooper Residence Marker, with a picture of her on her porch. (photo by Devry Jones).

The top image is the 44 cent United States Black Heritage postage stamp honoring Anna Julia Cooper that was issued in 2009.The bottom image is a historic marker located in LeDroit Park, Washington, D.C.: the Anna Julia Hayward Cooper Residence Marker, with a picture of her on her porch. (photo by Devry Jones).

November 23, 2019

Epigraphs—Chpt 2, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight

This statement by Portia Gage is the epigraph for Chapter 2 Confront Great Odds: 1866-1877: First, because I felt it was a duty, and second out of curiosity.

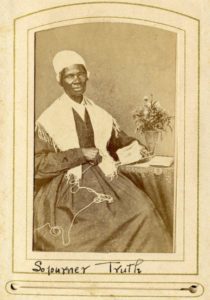

Portia and John Gage, in 1864, had moved from Illinois to Vineland, New Jersey. In 1861, Vineland was founded as a utopian temperance, (i.e., alcohol-free), and progressive community. Located in the southern part of the state, it was a trek for many of the kindred reformers. Yet they came to speak and be hosted by Portia and John Gage—Frederick Douglass, Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Victoria Woodhull, and Frances Dana Barker Gage, Portia’s sister-in-law—all of whom I wrote about in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight.  This image of Sojourner Truth was found in the Gage Family photo album.

This image of Sojourner Truth was found in the Gage Family photo album.

On March 10, Portia Gage accompanied John when he went to vote in a municipal election. “First, because I felt it was a duty, and second out of curiosity,” she explained in a letter. Like most women, she had been told that polling places were “dangerous . . . where it would not be safe for a woman.” Instead, she discovered that she felt “stronger, wiser and better for having come in contact with the political influence.” Her attempt to vote was blocked because she was not registered.

Eight months later, on November 3, for the 1868 federal election, I wrote in The Vote, “Portia and John took their places on the platform where the election officials sat . . . Next to them was a 12-by-6-inch box used for picking grapes where, by the end of the day, 172 black and white women had cast their ballots. Susan B. Anthony, who had lectured in Vineland in September, wrote to C. B. Campbell, a Vineland Quaker: “Vineland women did splendidly on election day.” (Click on images to enlarge them.)

November 21, 2019

Epigraphs—”The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight,” Part I, Chapter 1

This statement by Mistress Margaret Brent is the epigraphs for “The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight,” Part I, Chapter 1, Unsettle the Statue Quo: 1648-1865 Vote . . . and Voyce.

The chapter begins with this: “Women’s fight for the vote in America is typically said to have lasted seventy-two years, a figure that is arrived at by subtracting two dates —1848 from 1920. The first date, 1848, is when the first women’s rights convention met in Seneca Falls, New York, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the sharp-minded, upbeat, thirty-two-year-old mother who had spearheaded the convention, moved this resolution: “That it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.”1 The latter date is when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified and added to the United States Constitution: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” That seventy-two year period, however, is just a slice of the story.The whole story begins two hundred years earlier on a bluff overlooking the St. Mary’s River.”

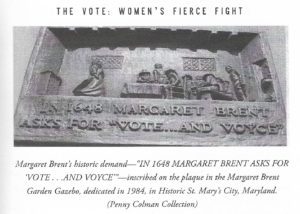

There is  a suffrage landmark honoring that earlier beginning on the bluff in Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland—Margaret Brent Garden Gazebo. A bronze bas-relief plaque sits on top of the pedestal inside the gazebo. It tells the story of Mistress Margaret Brent’s appearance in 1648 before the colonial assembly, demanding not just one, but two votes. I have visited this landmark twice. The image on the left was taken during my first visit on March 20, 2005, a windy day, judging from my hair! The image on the right is of the plaque that sits on top of the pedestal. It appears in my adult nonfiction book, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, now widely available in trade paperback and eBook.

a suffrage landmark honoring that earlier beginning on the bluff in Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland—Margaret Brent Garden Gazebo. A bronze bas-relief plaque sits on top of the pedestal inside the gazebo. It tells the story of Mistress Margaret Brent’s appearance in 1648 before the colonial assembly, demanding not just one, but two votes. I have visited this landmark twice. The image on the left was taken during my first visit on March 20, 2005, a windy day, judging from my hair! The image on the right is of the plaque that sits on top of the pedestal. It appears in my adult nonfiction book, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, now widely available in trade paperback and eBook.

Epigraphs—Chpt 1, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight

Vote . . . and Voyce. — Mistress Margaret Brent is the epigraph for Chapter 1 Unsettle the Statue Quo: 1648-1865 of The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight. The chapter begins with this: “Women’s fight for the vote in America is typically said to have lasted seventy-two years, a figure that is arrived at by subtracting two dates —1848 from 1920. The first date, 1848, is when the first women’s rights convention met in Seneca Falls, New York, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the sharp-minded, upbeat, thirty-two-year-old mother who had spearheaded the convention, moved this resolution: “That it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.”1 The latter date is when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified and added to the United States Constitution: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”2 That seventy-two year period, however, is just a slice of the story.

The whole story begins two hundred years earlier on a bluff overlooking the St. Mary’s River.”

There is a suffrage landmark honoring that earlier beginning on the bluff in Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland—Margaret Brent Garden Gazebo. A bronze bas-relief plaque sits on top of the pedestal inside the gazebo. It tells the story of Mistress Margaret Brent’s appearance in 1648 before the colonial assembly, demanding not just one, but two votes. (I tell the story and include the image of the plaqu e in my book.) I have visited this landmark twice. Linda took the picture of me and the gazebo during the first visit on March 20, 2005, a windy day, judging from my hair!

e in my book.) I have visited this landmark twice. Linda took the picture of me and the gazebo during the first visit on March 20, 2005, a windy day, judging from my hair!

November 19, 2019

Epigraphs and “The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight”

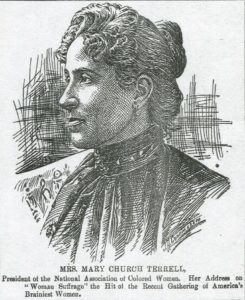

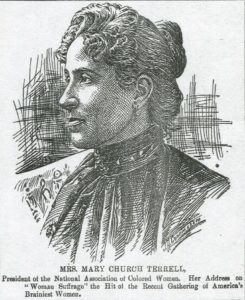

Most of my books have epigraphs, a short quotation or phrase that foreshadows a theme or an incident. You will find epigraphs in some of my tables of contents, in chapters, and as paragraph breaks in the text. In The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, my new adult nonfiction book, there are three epigraphs at the beginning of the book and an epigraph for each of the twenty-three chapters. In light of the 2020 presidential election, here is an epigraph from the beginning of The Vote: “If we do not use the franchise we shall give our enemies a stick with which to break our heads, and we shall not be able to live down the reproach of our indifference for one hundred years,” —Mary Church Terrell, First President of the National Association of Colored Women. This image is in my book. The caption reads: The Colored American National Negro Newspaper, Feb ruary 17, 1900, published this sketch of Mary Church Terrell after her second address to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The caption noted “Her address on ‘Woman Suffrage’ the Hit of the Recent Gathering of America’s Brainiest Women.” (Library of Congress) The image on the left

ruary 17, 1900, published this sketch of Mary Church Terrell after her second address to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The caption noted “Her address on ‘Woman Suffrage’ the Hit of the Recent Gathering of America’s Brainiest Women.” (Library of Congress) The image on the left  is of a landmark to Mary Church Terrell in Washington, D.C., honoring a demonstration she led in 1952 at the age of 88 to end segregation at the lunch counter of Hecht’s Department Store, formerly at this site. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

is of a landmark to Mary Church Terrell in Washington, D.C., honoring a demonstration she led in 1952 at the age of 88 to end segregation at the lunch counter of Hecht’s Department Store, formerly at this site. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

Epigraphs and The Vote

Most of my books have epigraphs, a short quotation or phrase that foreshadows a theme or an incident. You will find epigraphs in some of my tables of contents, in chapters, and as paragraph breaks in the text. In The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, my new adult nonfiction book, there are three epigraphs at the beginning of the book and an epigraph for each of the twenty-three chapters. In light of the 2020 presidential election, here is an epigraph from the beginning of The Vote: “If we do not use the franchise we shall give our enemies a stick with which to break our heads, and we shall not be able to live down the reproach of our indifference for one hundred years,” —Mary Church Terrell, First President of the National Association of Colored Women. This image is in my book. The caption reads: The Colored American National Negro Newspaper, Feb ruary 17, 1900, published this sketch of Mary Church Terrell after her second address to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The caption noted “Her address on ‘Woman Suffrage’ the Hit of the Recent Gathering of America’s Brainiest Women.” (Library of Congress)

ruary 17, 1900, published this sketch of Mary Church Terrell after her second address to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The caption noted “Her address on ‘Woman Suffrage’ the Hit of the Recent Gathering of America’s Brainiest Women.” (Library of Congress)

November 14, 2019

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and “Our Girls”

The Declaration of Sentiments, an iconic document, ended with a warning and pledge still relevant for fighters for equality and justice: “In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. . .”

Over the years I have visited many landmarks to Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The image is of a landmark I have yet to visit in Oxford, Ohio. Dedicated in 2012 by the League of Women Voters in Oxford, the sign commemorates ECS’s lecture on November 9, 1870. She stayed with her brother-in-law, Robert L. Stanton, the then president of Miami University. Her lecture, “Our Girls,” included this declaration: “Every girl should have something in and of herself, have an indi

vidual aim and purpose in life.” ECS was described as having a “melodious voice.”

vidual aim and purpose in life.” ECS was described as having a “melodious voice.”Interestingly, in the early 1960s I attended my fir

st two years of college at Western College for Women in Oxford, not having any idea that Elizabeth Cady Stanton had once lectured across the street at Miami University! “Our Girls” was one of her favorite lectures. As you can see from the poster, she presented it in Massillon, Ohio, in 1875. I included this poster in my book Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: A Friendship That Changed the World.

st two years of college at Western College for Women in Oxford, not having any idea that Elizabeth Cady Stanton had once lectured across the street at Miami University! “Our Girls” was one of her favorite lectures. As you can see from the poster, she presented it in Massillon, Ohio, in 1875. I included this poster in my book Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: A Friendship That Changed the World.(Click on image to enlarge it.)

November 11, 2019

Suffrage and World War I

I have written three books about women and war: “Spies: Women in the Civil War; “Rosie the RIveter: Women Working on the Home Front in World War II”; and “Where the Action Was: Women War Correspondents in World War II.”

In “The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight,” World War I impacts the suffrage movements abroad and in America. Regarding the British movement, I wrote: “The British fight for the vote was upended on August 4, 1914, when Great Britain entered World War I. This war, as had the Civil War in the 1860s in America, posed stark choices: war work, suffrage work, peace work, or a combination. Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst quickly made their choice . . .”

Three years later in 1917, American suffragists dealt with the same choices. I wrote about a meeting of the leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association that was “a volatile mix of militarists and pacifists.” It was a “difficult meeting” according to Mary Gray Peck . . . “the national officers and state presidents were women of strong personality and decided views.”

One of the threads i

n my book is newspaper coverage, and it wasn’t uncommon for suffrage and war news to share front page coverage.

n my book is newspaper coverage, and it wasn’t uncommon for suffrage and war news to share front page coverage. On June 27, 1917, the front page headline in the “Carson City Daily Appeal,” Carson City, Nevada, read AMERICAN TROOPS ARRIVE ON FRENCH SOIL. Just below it was an article with the headline: “Poor Mabel! How Could They Do It.” Mabel was Mabel Vernon of Nevada, one of six women picketing the White House who were convicted “of obstructing traffic” and fined $25 or three days in the District of Columbia jail. Vernon along with Katharine Morey, Lavinia Dock, Virginia Arnold, Maud Jamison, and Annie Arneil were the first of hundreds of suffragists who went to jail for the cause.

Penny Colman's Blog

- Penny Colman's profile

- 10 followers