Penny Colman's Blog, page 2

January 4, 2020

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VI, Chapter 17

I think there’s a possibility. This statement by Maud Wood Park is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VI, Chapter 17, Fiery Tactic: January-October 1918.

In the epigraph, Maud Wood Park, chief lobbyist for the National American Woman Suffrage Association, was referring to the “possibility” that the U. S. House of Representatives might finally pass a federal woman suffrage amendment. The vote was scheduled for January 10, 1918. “We scarcely ate and were too tired to sleep because of the innumerable last things to be attended to,” she reported. Park was apprehensive; so many things could go wrong. And they did—four “yes” votes met with calamities. One representative was delayed by a train wreck. Another suddenly had been taken to the hospital. Another remained hospitalized. One’s wife had died during the night. But, in the end, they all managed to arrive, most dramatically Henry Barnhart who was brought in on a stretcher.

There was a long day of speeches. Jeannette Rankin from Montana, the first woman  elected to Congress, made an eloquent appeal for passage. Anti-suffrage representatives spewed misogyny and racism. The amendment would enfranchise “colored women” and undercut “Southern States . . . struggling to maintain law and order and white supremacy,” warned John A. Moon from Tennessee. It took three roll calls before the clerk announced the vote as 274 yeas and 136 nays, the necessary two thirds, with just one vote to spare! Pandemonium erupted—women and men shouting, cheering, shaking hands, hugging, crying for joy. Outside the gallery door, a woman started singing the hymn “Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow” and a multitude of voices joined her.”

elected to Congress, made an eloquent appeal for passage. Anti-suffrage representatives spewed misogyny and racism. The amendment would enfranchise “colored women” and undercut “Southern States . . . struggling to maintain law and order and white supremacy,” warned John A. Moon from Tennessee. It took three roll calls before the clerk announced the vote as 274 yeas and 136 nays, the necessary two thirds, with just one vote to spare! Pandemonium erupted—women and men shouting, cheering, shaking hands, hugging, crying for joy. Outside the gallery door, a woman started singing the hymn “Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow” and a multitude of voices joined her.”

The Senate vote was the next battle: It was scheduled for May 10. Maud Wood Park was optimistic—”Victory seems in our hands . . .The galleries were filled. The senators came in all dressed up for the occasion—here a gay waistcoat or a bright tie, a flower in a button-hole, yonder an elegant frock coat over gray trousers.” But it was not to be. The opposition took over the proceedings. Sensing defeat, Senator Jones withdrew the motion to vote on the woman suffrage amendment.

Three months later, on August 6, the day the suffrage martyr Inez Milholland would have turned thirty-two, a line of almost one hundred women wearing white gowns and bearing purple, white, and gold banners and flags marched to the statue of Lafayette, across from the White House. Police broke up their demonstration, arresting forty-eight women. Twenty-four were sent to an old jail, a rat-and-vermin infested hellhole that had been declared unfit for human habitation in 1909. Released after five days, the suffragists were “trembling with weakness, chills, and fever, scarcely able even to walk to the ambulance or motor car.” In September, the NWP staged another demonstration at Lafayette’s statue.  This time, symbolizing “the burning indignation of women,” they introduced a new—a fiery tactic—and burned a piece of paper inscribed with some of President Wilson’s “empty words” about his support for woman suffrage.

This time, symbolizing “the burning indignation of women,” they introduced a new—a fiery tactic—and burned a piece of paper inscribed with some of President Wilson’s “empty words” about his support for woman suffrage.

On Sept. 26, the U. S. Senate again considered the woman suffrage amendment. The debate went on for five days. On Sept. 30, President Wilson made an unprecedented personal appeal to the Senate to approve the amendment. The next day, Oct 1., the woman  suffrage amendment was defeated, two votes short of the required three fourths. “Stunned, as though unable to grasp it, hundreds of women sat there,” wrote Maud Younger, chief lobbyist for the NWP. “Then slowly the defeat reached their consciousness, and they began slowly to put on their hats, to gather up their wraps, and to file out of the galleries, some with a dull sense of injustice, some with burning resentment.” President Wilson had “done something . . . but there was a great deal more that he could have done,” concluded Maud Younger.

suffrage amendment was defeated, two votes short of the required three fourths. “Stunned, as though unable to grasp it, hundreds of women sat there,” wrote Maud Younger, chief lobbyist for the NWP. “Then slowly the defeat reached their consciousness, and they began slowly to put on their hats, to gather up their wraps, and to file out of the galleries, some with a dull sense of injustice, some with burning resentment.” President Wilson had “done something . . . but there was a great deal more that he could have done,” concluded Maud Younger.

In Chapter 17 in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, I describe the dramatic  votes, demonstrations, arrests, and incarcerations. The images from top to bottom: Maud Park Wood, Jeannette Rankin, demonstration at Lafayette’s statue, and a photo of Maud Younger from a newspaper in Wabeno, Wisconsin (8/18/1916, p. 2). The caption points out that Younger teaches suffragists how to lobby. The Congressional Union was the predecessor to the NWP. (Click on images to enlarge.)

votes, demonstrations, arrests, and incarcerations. The images from top to bottom: Maud Park Wood, Jeannette Rankin, demonstration at Lafayette’s statue, and a photo of Maud Younger from a newspaper in Wabeno, Wisconsin (8/18/1916, p. 2). The caption points out that Younger teaches suffragists how to lobby. The Congressional Union was the predecessor to the NWP. (Click on images to enlarge.)

Epigraph: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part V, Chapter 16

They tried to terrorize and suppress us. They could not. This statement by Alice Paul is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 16, Night of Terror: September-December 1917.

Forty-one women from across America had answered Alice Paul’s summon to picket the White House. Front-page headlines on November 11, 1917 announced their arrest. They were tried and sentenced to terms ranging from six days for seventy-three-year-old Mary Nolan, a longtime suffragist from Florida, to seven months for Lucy Burns, a member of the NWP’s executive committee who had already served two jail sentences. They arrived at Occoquan  Workhouse in the early evening of November 14. The superintendent, Raymond Whittaker was not there. Intending to state their demand to be treated as political prisoners, Dora Lewis, the “velvet-voiced and immovable” acting chair of the NWP, refused to give their names to the matron. They would wait for Whittaker who was at a meeting at the White House.

Workhouse in the early evening of November 14. The superintendent, Raymond Whittaker was not there. Intending to state their demand to be treated as political prisoners, Dora Lewis, the “velvet-voiced and immovable” acting chair of the NWP, refused to give their names to the matron. They would wait for Whittaker who was at a meeting at the White House.

The exhausted women waited, some sitting and others lying on the floor. Mary Nolan described Whittaker’s arrival and subsequent events in what became known as “The Night of Terror”: “We could see a crowd of them on the porch. They were not in uniform. Mrs. Lewis stood up. . .She had hardly begun to speak, saying we demanded to be treated as political prisoners, when Whittaker said, ‘You shut up. I have men here to handle you.’ Then he shouted ‘Seize her!'”

Thus began a night-long vicious attack on the women. Dora Lewis was thrown in a cell, striking her head on the iron bed. Dorothy Day was lifted up and banged down on the arm of an iron bench. Emily DuBois Butterworth was taken to the male section of the jail and told that “they could do what they pleased with her.” Lucy Burns was handcuffed to the cell door with her arms stretched above her head.

On Nov. 27 and 28, Judge Mullowney ordered the release of the women remaining in jail, including Alice Paul who had been jailed in October, where she and Rose Winslow went on a hunger strike and were force fed. Upon her release, a “very pale and thin” Alice Paul said: “We are put out of jail as we were put into jail, at the whim of the government. They tried to terrorize and suppress us. They could not, and so freed us.”

I detail the attack, hunger strikes, forced feeding, and the efforts to free the women in Chapter 16 in my book, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight. The images from top to bottom: Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, Dora Lewis upon her release from jail, having undergone a five-day hunger strike and been force fed. (Click on image to enlarge.)

I detail the attack, hunger strikes, forced feeding, and the efforts to free the women in Chapter 16 in my book, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight. The images from top to bottom: Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, Dora Lewis upon her release from jail, having undergone a five-day hunger strike and been force fed. (Click on image to enlarge.)

January 1, 2020

General Jones and the Suffrage Army Arrive

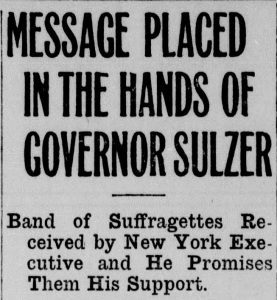

And, so, on Dec. 31, 1912, in Albany, General Rosalie Jones handed Governor-elect William Sulzer the “secret message,” a document signed by state suffrage leaders, asking his support for the cause. With her were seven “pilgrims,” carrying their knapsacks and staffs, who had

hiked for twelve days from New York City to Albany through rain storms, blizzards, mud and snow and chilling winds. Sulzer praised their efforts, shook their hands, and promised to support the cause. Bishop William Doane of the Episcopal Diocese of Albany, however, denounced the hikers as “a band of silly, excited and exaggerated women.”

hiked for twelve days from New York City to Albany through rain storms, blizzards, mud and snow and chilling winds. Sulzer praised their efforts, shook their hands, and promised to support the cause. Bishop William Doane of the Episcopal Diocese of Albany, however, denounced the hikers as “a band of silly, excited and exaggerated women.”

The novelty and hardship of Jones’ suffrage march attracted reporters from across America; as many as eleven male and female reporters followed the “pilgrims” in automobiles. The image on the top left appeared in a Boise, Idaho newspaper. The image on the right was in a Tacoma, Washington newspaper. (Note the disrespectful cartoon caricature.) The third image is from a newspaper in Wausau, Wisconsin. (Click on images to enlarge.) The march of General Jones and the Suffrage Army was “a picturesque thing to do, and splendid to stir up sentiment,” said suffragist Nora Blatch De Forest, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s granddaughter. As is common in social movements, not all workers for the cause agreed: Mary Garrett Hay, a leading New York suffragist, huffed, “You’ll never find Mary Hay in anything sensational. I’m too busy doing real work.” As, for General Rosalie Gardiner Jones, she said: “Hundreds of people have heard the votes for women gospel whom we never could have reached through ordinary meetings . . . . Awake sisters, and help us. It won’t do to sit back and say, ‘Yes, I think women ought to vote.’ We must pack up our knapsacks and say, ‘We’ve got to get it.'” A fierce fight, indeed!

is from a newspaper in Wausau, Wisconsin. (Click on images to enlarge.) The march of General Jones and the Suffrage Army was “a picturesque thing to do, and splendid to stir up sentiment,” said suffragist Nora Blatch De Forest, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s granddaughter. As is common in social movements, not all workers for the cause agreed: Mary Garrett Hay, a leading New York suffragist, huffed, “You’ll never find Mary Hay in anything sensational. I’m too busy doing real work.” As, for General Rosalie Gardiner Jones, she said: “Hundreds of people have heard the votes for women gospel whom we never could have reached through ordinary meetings . . . . Awake sisters, and help us. It won’t do to sit back and say, ‘Yes, I think women ought to vote.’ We must pack up our knapsacks and say, ‘We’ve got to get it.'” A fierce fight, indeed!

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and ebook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and ebook.

December 30, 2019

Epigraph: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part V, Chapter 15

Arrests! There is no law against what we are doing, remember that. This statement by Dora Lewis is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 15, Arrests!:  Spring-September 1917

Spring-September 1917

On July 4, 1917, Independence Day, fifty-four-year-old Dora Lewis, a member of the NWP Executive Committee, mailed a postcard to her eighty-one-year-old mother, who had sent Dora a jar of jelly. Dearest Mother . . . . We are going out presently carrying our banner—Policemen and policewomen & plain clothes men on the sidewalks thick as blackberries. There is no law against what we are doing, remember that. Love to Father . . . .I’m expecting to enjoy that jelly in jail. Your loving D.

The police had started arresting picketing suffragists on June 22, 1917, after two days of mobs assaulting suffragists and destroying their banners. A Philadelphia newspaper covered the melee with a front-page article headlined: CAPITAL POLICE STOP PICKETING. The continuation of the article on page three was illustrated by three photographs grouped together with the headline MOB ATTACKS SUFFRAGISTS IN STREETS OF WASHINGTON. (Click to enlarge images.)

The mob’s attack was precipitated by the banner, known as the Russian banner. It was in response to news that President Wilson’s envoy to Russia, Elihu Root, had claimed that there was universal suffrage in America. The banner charged Wilson and Root with “deceiving Russia,” an ally during World War I, pointing out that “twenty million American women are denied the right to vote” and pleading—“Help us make this nation really free.”

After consulting with administration officials, the chief of police called Alice Paul. Stop sending the pickets, he told her, or they will be arrested. Picketing was legal, according to their lawyers, Paul replied: “Certainly it is as legal in June as it was in January. The picketing will go on as usual.” Pickets were arrested and released until June 26 when six pickets were found guilty of obstructing traffic,” and given a fine of $25 or three days in the District of Columbia Jail. The women chose to go to jail. The mob attacks, arrests, and jailing of pickets continued.

December 29, 2019

Suffrage Army

On the last day of their 12-day, 174-mile suffrage hike, General Jones and her suffrage soldiers, walked 18 miles on roads six inches deep with soft, wet snow over mud. A contingent of local suffragists met them in East Greenbush, 3 1/2 miles from Albany. “General, the State capitol is in sight!” one of them told her. “Don’t let it get away till we can get there,” she replied with a sigh. They reached the capitol at 4:30 p.m.

GENERAL JONES AND ARMY REACH CAPITAL announced a newspaper in Boise, Idaho. Governor-elect William Sulzer was due to arrive in Albany on December 31. Would he meet with Jones and receive the “secret message” she had carried from New York City?  The image is from a New York City newspaper. Jones is pictured standing on a stump, giving a suffrage speech. The caption read: “General Rosalie Jones, who triumphantly led her army of suffragists into Albany yesterday, but who fell from a stump when she made a speech.”

The image is from a New York City newspaper. Jones is pictured standing on a stump, giving a suffrage speech. The caption read: “General Rosalie Jones, who triumphantly led her army of suffragists into Albany yesterday, but who fell from a stump when she made a speech.”

In an interview, Rosalie Gardiner Jones, the 29-year-old free-spirit from a conservative, wealthy, socially prominent Long Island, New York family, said that news of the 1911 victorious women’s suffrage amendment referendum campaign in California had galvanized her suffrage activism to get the word “male” removed from voter qualifications in New York’s constitution. First, she had targeted towns around her family’s home in Cold Spring Harbor, determined to arouse public support by giving suffrage speeches, calling meetings, and distributing literature and “Votes for Women” flags. In June, she had teamed up with thirty-six-year-old Elisabeth Freeman, who dressed like a gypsy. Together they traveled across Long Island in a little yellow wagon pulled by a horse named Suffragette, spreading the suffrage message. In July they took their wagon and horse to Ohio to campaign for passage of the Ohio Women’s Suffrage Amendment. (It was soundly defeated by male voters.)

As for undertaking the suffrage hike, Rosalie Jones said that news of a suffrage hike from Edinburgh, Scotland, to London, England, had inspired her. Known as “The Brown Women,” because of their brown clothing, Florence Gertrude de Fonblanque and her companions hiked from October 12-November 16. (de Fonblanque had “Orginator and leader of the women’s suffrage march from Edinburgh to London, 1912” inscribed on her gravestone.)

Suffragists had spent years fighting for passage of a woman suffrage amendment to the New York state constitution. A referendum on a woman suffrage amendment could be approved for a referendum by either a constitutional convention or by legislative action. Suffragists had tried the constitutional convention route in 1867 and 1894, vigorously testifying, lobbying, submitting letters, testimonies, and petitions (0ne petition had 600,000 signatures). All in vain. By 1912, however, their unceasing efforts with legislators appeared to be finally paying off. The new legislature that would convene in January 1913 was poised to approve a woman suffrage amendment that would then have to be passed by a successive legislature. Once that happened, a referendum on a woman suffrage amendment would be on the ballot in 1915. Awakening the public, pressuring politicians and the newly-elected governor, was General Rosalie Jones’s mission. “We have left a trail of thought and suggestions behind us . . .” she said. ‘The process of awakening the public mind to the need of votes for women is very slow, but we feel that this pilgrimage has brought the matter before the public in a manner that would have been possible no other way.” In 2020, the centennial of the 19th Amendment, a statue of Rosalie Gardiner Jones will be dedicated in Cold Spring Harbor Park on Long Island.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

December 27, 2019

Suffrage Love Story

Suffrage Love Story: CUPID REINFORCES THE SUFFRAGE ARMY read the headline in a New York City newspaper the day after Christmas. The buzz started Christmas morning that Griffith Bonner had proposed to suffrage hiker Gladys Coursen, although both denied it.

Griffith had been courting Gladys for several years. When she became a suffragist he organized a Men’s League. When she joined the hikers in Poughkeepsie, he joined too, as did another suitor Pelton Cannon. Pelton mistakenly tried to persuade Gladys to drop out: Griffith hiked on. The fact that Gladys and Griffith had gotten engaged Christmas morning in Hudson, NY, was confirmed when Gladys appeared with a huge bunch of violets that Griffith had had shipped from New York City and his college pin was spotted in between the ruffles of her dress.

Today, 12/27 in 1912, General Jones and the Suffrage Army plodded 14 miles through “Slush and Mud in a Heavy Storm” and spent the night in Niverville, NY. HEAVY SNOW FAILS TO DAUNT WOMEN ON ALBANY MARCH read the front-page headline in a Bisbee, Arizona, newspaper. Their destination tomorrow is—Albany!

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook

Suffrage Christmas

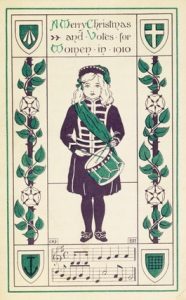

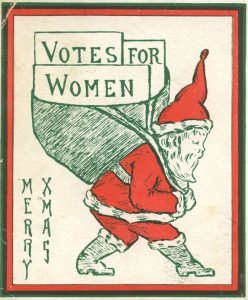

Christmas postcards with suffragists’ “Votes for Women” message—”Little Drummer Girl” (1910), Santa Clause (1911.)

Christmas Eve Day, 12/24/1912—No room in the inn for the “ARMY OF SUFFRAGE”

Eight days into their march from New York City to Albany to deliver a suffrage message to the newly elected governor of New York, “General” Rosalie Jones and her suffrage army reached their destination, Livingston, NY, only to discover that the inn was full.

According to a reporter, dubbed a “war correspondent” riding in a car, the “brave women soldiers” set off for Hudson, 8 miles away, with “heads bent to a cold, biting wind and a stinging snow . . . Courageously they plowed through snow drifts, slipping, sliding and sometimes falling, but always up and off again.” They reached Hudson after nightfull.

I’ll post tomorrow about how General Rosalie Jones and her suffrage army celebrated Christmas.

Christmas Day, 1912: General Rosalie Jones and her “Suffrage Army”—Colonel Ida Craft, Surgeon Lavinia Dock, Major Katherine T. Stiles, Lieutenant-Colonel & war correspondent Jessie Hardy Stubbs, and Privates Alice Clark and Gladys Coursen had hiked on the day before Christmas through a blizzard. At nightfall, they had arrived at the Worth Hotel, Hudson, NY, with ice in their hair and wet up to their knees.

Settling into rooms at the Worth Hotel, they undressed and were wrapped in hot blankets. General Jones, sitting with her feet in hot water and cold cream covering her face, issued her last order of the day on which they had hiked a total of 22 miles: “Those who wish may go to supper, but I am going straight to bed.”

On Christmas Day, General Jones told reporters: “We wish the gladdest of the season’s greetings to all suffragists all over the country.”

They spent Christmas morning at a roller skating rink. Despite her blisters, Rosalie Jones skated around several times. When the owner stopped the music, she gave a suffrage speech. After lunch at the hotel, they exchanged gifts—cold cream, foot soap, and foot warmers—around a Christmas tree in the lobby. A copy of “Pilgrim’s Progress,” signed with a sentiment from each “soldier,” was presented to Gen. Jones.

In the evening, they attended an annual Charity Ball, dressed as “Spirits” in costumes carried on their supply wagon.

I particularly love this part of their day because although my school education was devoid of historic women, generations of suffragists knew about and honored their foremothers: Gen. Jones dressed as Abigail Adams, wearing a pink and blue costume, a blue stain petticoat under a polonaise and looped panniers of flowered pink silk, and black velvet shoes with buckles. Major Stiles dressed as Mercy Otis Warren, garbed in a black velvet and lace gown, with high-heeled shoes of black velvet, and widely draped panniers. War Correspondent Jessie Hardy Stubbs represented Mistress Margaret Brent, who leads off my book “The Vote.” Colonel Ida Craft wore a garnet gown, kerchief, and Quaker cap, representing Lucretia Mott at the Charity Ball. Gladys Coursen dressed as herself, representing the “Spirit of 1912.” She carried a placard with the names of the equal suffrage states.

They mingled as “Spirits” in silence for an hour. Then they left, changed, returned, and danced!

Image L-R: Jessie Hardy Stubbs, Ida Craft, Rosalie Jones. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

Image L-R: Jessie Hardy Stubbs, Ida Craft, Rosalie Jones. (Click on images to enlarge them.) My new book—The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight— is available in paperback and eBook

My new book—The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight— is available in paperback and eBook

December 13, 2019

Epigraphs: “The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part V, Chapter 14

This statement by William “Bill” Martz is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 14, Tireless Struggles: January-April 1917—I vote ‘Aye’, and I can’t explain my vote.

Suffragists were doggedly determined to win the right to vote, even if it meant just partial suffrage such as the right to vote on school matters, tax and bond issues, or in municipal and presidential elections. (Kentucky became the first state to granted partial suffrage to women, albeit for a very select group of women and a tidbit of suffrage: On February 6, 1838, the General Assembly granted school suffrage to property-owning widows and unmarried women, over the age of twenty one, who lived in a school district.) By 1916, persistent, politically savvy suffragists had persuaded legislatures in twenty-seven states, out of forty-eight, to grant women some form of partial suffrage.

Between January and April 1917, suffragists conducted a record number of eleven partial suffrage campaigns. Ten campaigns sought presidential and municipal suffrage. In Arkansas, suffragists and the newly elected pro-suffrage governor, Charles Hillman Brough, urged legislators to grant women primary suffrage. (A one-party state, whoever won a primary in Arkansas was sure  to win the election.) The first image in a victory celebration on the steps of the Capitol in Little Rock. Brough, wearing a white shirt, suit and shoes, and a black bow tie, is standing on the third step, slightly right of center.

to win the election.) The first image in a victory celebration on the steps of the Capitol in Little Rock. Brough, wearing a white shirt, suit and shoes, and a black bow tie, is standing on the third step, slightly right of center.

In Michigan, on April 18, 1917, William “Bill” Martz of Detroit, known for the “tremendous power of his booming voice, roared, “I vote ‘Aye’ and I can’t explain my vote.” Martz was voting on a presidential suffrage bill. Stunned silence greeted his announcement, then applause, for Martz was an avowed foe of woman suffrage—unless, it turned out, his wife was sitting about three feet away from him and “happily smiling.” The bill that had already been passed in the Senate passed by a majority 84 votes: 135 yeas, 51 nays. Margaret Whittemore, a NWP organizer whose Quaker grandmother was a pioneering suffragist in Michigan, was elated by the news. “It is with a new sense of political power that I continue my work in organizing women for national suffrage.”

Anna Dallas Dudley, considered a “legendary beauty,” led a spirited campaign in Tennessee. President of the Tennessee state suffrage association, Dudley pitched her appeals to men in the South, where the notion of chivalry still held sway: “I don’t want to  usurp your place in government, but it is time I had my own,” she sweetly assured them. When the legislature defeated the presidential and municipal suffrage bill, Dudley said—”We are not crybabies . . . .We will simply work harder for suffrage in Tennessee.” The second image is Anna Dallas Dudley with her children who led parades with her.

usurp your place in government, but it is time I had my own,” she sweetly assured them. When the legislature defeated the presidential and municipal suffrage bill, Dudley said—”We are not crybabies . . . .We will simply work harder for suffrage in Tennessee.” The second image is Anna Dallas Dudley with her children who led parades with her.

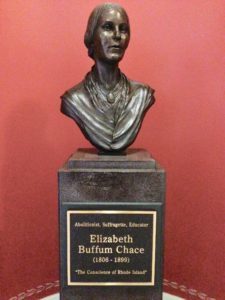

Of the eleven vigorous, all-consuming partial-suffrage campaigns, there were eight victories: North  Dakota, Ohio, Indiana, Arkansas, Rhode Island, Vermont, Nebraska, and Michigan. The third image is a bust of Elizabeth Buffum Chace, a co-founder and president of the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association. On one of my many women history road trips, I stopped at the Rhode Island State House in Providence to visit and photograph the bust of Chace, known as “the Conscience of Rhode Island.” (Click on images to enlarge them.)

Dakota, Ohio, Indiana, Arkansas, Rhode Island, Vermont, Nebraska, and Michigan. The third image is a bust of Elizabeth Buffum Chace, a co-founder and president of the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association. On one of my many women history road trips, I stopped at the Rhode Island State House in Providence to visit and photograph the bust of Chace, known as “the Conscience of Rhode Island.” (Click on images to enlarge them.)

As they always did, opponents contested every victory. Two were overturned: in Ohio by another referendum and in Indiana by a court ruling. In Nebraska, the victory was suspended due to litigation. Subtracting Ohio, Indiana, and Nebraska from the eight victories and adding them to the three losses (Tennessee, New Hampshire, Maryland) adds up to more defeats (six) than victories (five)—a fierce fight, indeed!

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, adult nonfiction, 444 pages, 35 images, Author’s Note, epilogue, bibliography, notes, index, is widely available in trade paperback and eBook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, adult nonfiction, 444 pages, 35 images, Author’s Note, epilogue, bibliography, notes, index, is widely available in trade paperback and eBook.

December 11, 2019

Epigraphs: “The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight,” Part V, Chapter 13

This statement by Olympia Brown is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 13, Silent Sentinels: January-April 1917—Patience ceases to be a virtue.

Olympia Brown, the first woman to graduate from an established theological school, had been fighting for the vote since 1867 when she gave 300 speeches in four months in the first state to hold a woman suffrage amendment referendum campaign—Kansas. The first image is an article, “Rev. [image error]Olympia Brown/The Life and Work of a Famous Woman Preacher,” that appeared in a Wichita, Kansas, newspaper, The Wichita Daily Eagle, June 3, 1890.

A former vice president of the National America Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), Olympia Brown joined the Congressional Union (CU), impressed by Alice Paul’s vigorous tactics, including pioneering the tactic of picketing the White House. “Patience ceases to be a virtue,” Olympia Brown declared. “We cannot allow our cause to rest, or to be overlooked or over-shadowed. (In March the two organizations founded by Paul, the CU and the Woman’s Party, merged under the name the National Woman’s Party (NWP).)

In 1917, eighty-two-year old Olympia Brown came from Wisconsin to join the picket line of suffragist-banner-bearers silently standing in front the White House. On January 10, Paul had led the first team of pickets, twelve women, each wearing a purple, white, and gold “Votes for Women” sash across her coat and [image error]carrying a large banner inscribed with a slogan such as Inez Milholland’s last words: MR. PRESIDENT/HOW LONG/MUST/WOMEN WAIT/FOR LIBERTY? Valiantly, the stalwart women had marched the short distance from their headquarters on Lafayette Park to the White House, where they stood in silence. WOMEN BEGIN SILENT PICKET read the front-page headline in an Ogden, Utah, newspaper. (Second image is Olympia Brown) Day after day, regardless of the weather, side by side, a kaleidoscope of pickets from across America (more than 2,000 women over two and a half years) took  their place. The third image is a line of Silent Sentinels picketing the White House. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

their place. The third image is a line of Silent Sentinels picketing the White House. (Click on images to enlarge them.)

Chapter 13 includes many other events, including a dramatic demonstration on a day of “high wind and stinging, icy rain,” and the election of the first women to the U.S. Congress. The next three chapters—14, 15, 16—cover events in 1917, including “Arrests!” and “Night of Terror.  The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, adult nonfiction, 444 pages, 35 images, epilogue, bibliography, notes, index, is widely available in trade paperback and eBook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, adult nonfiction, 444 pages, 35 images, epilogue, bibliography, notes, index, is widely available in trade paperback and eBook.

Epigraphs: “The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight,” Part V, Chapter 13,

This statement by Olympia Brown is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 13, Silent Sentinels: January-April 1917—Patience ceases to be a virtue.

In writing these posts, I am focusing on events that relate to the epigraph, although there is so much more in each chapter. Olympia Brown, the first woman to graduate from an established theological school, had been fighting for the vote since 1867 when she gave 300 speeches in four months in Kansas, the first state to hold a woman suffrage amendment referendum campaign. Kansas was frontier country, where food was scarce, roads were mere tracks across prairies, and chinch bugs were everywhere. Although not so well known today, Brown was a prominent in her day. The first image is an article, “Rev. Olympia Brown/The Life and Work of a Famous Woman Preacher,” that appeared in a Wichita, Kansas newspaper, The Wichita Daily Eagle, June 3, 1890.

A former vice president of the National America Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), Olympia Brown joined the Congressional Union (CU), impressed by Alice Paul’s vigorous tactics. “Patience ceases to be a virtue,” Brown declared. “We cannot allow our cause to rest, or to be overlooked or over-shadowed. (In March the two organizations founded by Paul, the CU and the Woman’s Party, merged under the name the National Woman’s Party (NWP).)

In 1917, eighty-two-year old Brown, came from Wisconsin, to picket the White House. On January 10, Paul had led the first team of pickets, twelve women, each wearing a purple, white, and gold “Votes for Women” sash across her coat and  carrying a large banner inscribed with slogan, including Inez Milholland’s last words: MR. PRESIDENT/HOW LONG/MUST/WOMEN WAIT/FOR LIBERTY? Valiantly, the women, the first people to picket the White House, had marched the short distance from their headquarters on Lafayette Park to the White House, where they stood in silence. WOMEN BEGIN SILENT PICKET read the front-page headline in an Ogden, Utah, newspaper. (Second image taken in front of CU’s headquarters) Day after day, side by side, a kaleidoscope of pickets from across America (more than 2,000 women over two and a half years) took

carrying a large banner inscribed with slogan, including Inez Milholland’s last words: MR. PRESIDENT/HOW LONG/MUST/WOMEN WAIT/FOR LIBERTY? Valiantly, the women, the first people to picket the White House, had marched the short distance from their headquarters on Lafayette Park to the White House, where they stood in silence. WOMEN BEGIN SILENT PICKET read the front-page headline in an Ogden, Utah, newspaper. (Second image taken in front of CU’s headquarters) Day after day, side by side, a kaleidoscope of pickets from across America (more than 2,000 women over two and a half years) took  their place. (The next three chapters—14, 15, 16—cover events in 1917, including “Arrests!” and “Night of Terror.” (Click on images to enlarge them.)

their place. (The next three chapters—14, 15, 16—cover events in 1917, including “Arrests!” and “Night of Terror.” (Click on images to enlarge them.)

Chapter 13 includes many other events, including a dramatic demonstration on a day of “high wind and stinging, icy rain.” The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is widely available in trade paperback and eBook.

Penny Colman's Blog

- Penny Colman's profile

- 10 followers