Marc Leepson's Blog

September 18, 2025

September 2025

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XXII, Number 9 September 2025

EXCELLENT MANAGEMENT: Pop quiz: Can you name the non-enslaved person who lived at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello for the longest period of time in the house’s long history? If you said Thomas Lionel Rhodes, you are correct.

Jefferson Monroe Levy hired Tom Rhodes as his on-site superintendent at Monticello in October 1887 and he wound up living and working on the mountaintop for the next 57 years until he retired in 1944. He died in 1953 in his 90th year.Tom Rhodes (below, in a 1930s newpaper photo) was the seventh superintendent Jefferson Levy hired after he bought out his uncle Uriah Levy’s other heirs and purchased Monticello in 1879 when the property was in terrible condition after 17 years of neglect UPL’s heirs wrangled over the fate of the property.

Choosing Rhodes turned out to be a very fortuitous event in Monticello’s history.By all accounts, the 26-year-old Albemarle County (Va.) native was a tireless worker and a passionate advocate for the preservation and protection of Jefferson’s architectural masterpiece and its grounds. With Jefferson Levy paying the bills, Tom Rhodes spent more than 35 years overseeing the work on the ground repairing, restoring, and preserving Thomas Jefferson’s “Essay in Architecture.” He continued that work after Levy sold Monticello to the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation in 1923.

“Monticello profited for over half a century from the inspired, devoted, indefatigable labor and financial sacrifice of Tom Rhodes,” Theodore Fred Kuper, a founder and former national director of the Foundation, said in 1955.“Every bit of work on the buildings, in the rooms or on the grounds was done under [his] personal direction.”

In the years after 1923 “when the Jefferson Foundation found it difficult to raise the needed funds, Tom Rhodes understood and voluntarily postponed the time for the modest payments due him for his work.”

Thomas Rhodes was born June 11, 1863, at Rhodes Mill, in Ivy, Virginia, six miles outside of Charlottesville, the son of Madison and Harriet Marr Rhodes. Madison Rhodes was a barrel manufacturer who served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War.

His son had a rudimentary education and began working full time at the age of twelve. He specialized in farm management and had run Morsebrook Farm in Albermarle County for 14 years before going to work at Monticello. Levy hired him in 1887 to oversee the house, grounds, and farming operations at Monticello, where Tom Rhodes found his life’s work. That also included maintaining a large vegetable garden, berry patches, and grapevines.

As I noted in Saving Monticello, soon after he came to live and work at Monticello, Tom Rhodes married Junietta Cressey. They had a son, Frederick Hall Rhodes, who was born July 19, 1891, and brought up at Monticello. In April 1898, the Charlottesville Daily Progress reported favorably on the work Tom Rhodes had done on the grounds.

“The banks on either side of the drive from the porter’s lodge to the mansion have been sewn with grass seed, and at intervals rare and beautiful flowers have been planted, which are now blooming,” the article said. “The lawns are in perfect sod and on them are late acquisitions of flowering shrubs.”

The newspaper reported that Rhodes had planted large crops of wheat, oats, and corn on the mountaintop, and that he was overseeing construction of a driveway on Monticello’s [Rivanna] river side. “There are to be many more costly improvements which will further beautify this magnificent estate,” the paper said. “Everything about the place gives evidence of excellent management.”

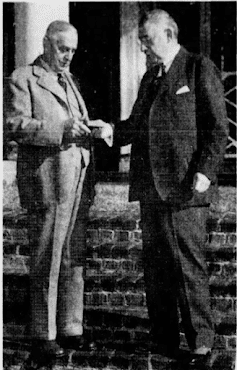

Thomas Rhodes, left, in a newspaper photo receiving a goldwatch from Stuart Gibboney, the president of the Thomas Jefferson MemorialAssociation, on January 1, 1938, marking his 50th year (in 1937) asMonticello's superintendent

One stain on Rhodes’ management of Monticello was his steadfast allegiance to the tenets of the Confederate cause, which lasted into the 1920s. The son of a man who fought for the South during the Civil War, Tom Rhodes flew a Confederate flag in front of the house and had separate restrooms on the mountaintop for Blacks and whites.

Fred Kuper put a stop the display of the Confederate Battle Flag as well as Rhodes’ discriminatory policies, soon after the Foundation bought the property from Jefferson Levy in late 1923. “I am very proud to add that, on my instructions to Rhodes,” Kuper later said, “all visitors to Monticello were to be received and treated regardless of color, nationality, religion, etc., and that there was to be no segregation even in toilet facilities, which were to be solely for ‘gentlemen’ and ‘ladies.’”

Thomas Rhodes died at 89 on January 27, 1953, at a nursing home in Charlottesville where he had been living since his retirement nine years earlier. He is buried in Riverview Cemetery in Charlottesville alongside his wife Junietta.

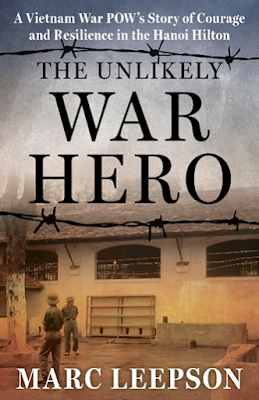

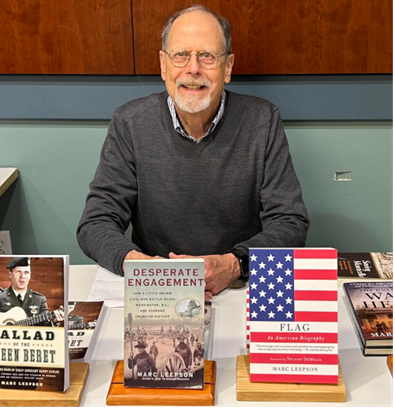

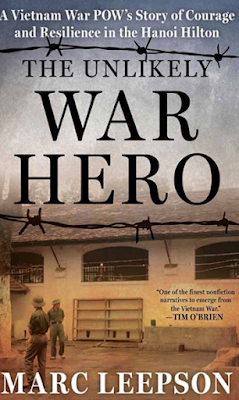

EVENTS & COMMERCE: I have a good number of events scheduled this fall, most of them on Lafayette: Idealist General, my newly re-released concise biography of the famed Marquis, and my latest book, The Unlikely War Hero, a slice-of-life biography of the extraordinary Vietnam War story of Doug Hegdahl, the youngest and lowest ranking American prisoner held in Hanoi during the war. I’m also doing talks, podcasts, and other events for the paperback edition of Lafayette: Idealist General and, of course, Saving Monticello. Many are speaking engagements for historic preservation and other groups. Most are open to the public.

EVENTS & COMMERCE: I have a good number of events scheduled this fall, most of them on Lafayette: Idealist General, my newly re-released concise biography of the famed Marquis, and my latest book, The Unlikely War Hero, a slice-of-life biography of the extraordinary Vietnam War story of Doug Hegdahl, the youngest and lowest ranking American prisoner held in Hanoi during the war. I’m also doing talks, podcasts, and other events for the paperback edition of Lafayette: Idealist General and, of course, Saving Monticello. Many are speaking engagements for historic preservation and other groups. Most are open to the public. For details, go to: marcleepson.com/events If you’d like to arrange a talk on The Unlikely War Hero, Saving Monticello, Lafayette, or any of my other books, please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com To order signed copies from my website, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrdering

August 22, 2025

August 2025

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest aboutthe book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor- Marc Leepson

VolumeXXII, Number 8 August2025

PRIDE IN OWNERSHIP: On May 9, 1923, as Jefferson Levy wasnegotiating the sale of Monticello to the fledgling Thomas JeffersonFoundation, he granted a rare newspaper interview in his West 37thStreet New York City brownstone to Raymond G. Carroll of the Philadelphia Public Ledger.

It marked one of the very few times inhis life that the then 71-year-old Levy had opened up about his personal life toa journalist. The article, which appeared two days later and was subsequentlycarried in other newspapers across the country, provides a rare glimpse intoJefferson Levy’s lavish New York City lifestyle, along with his thoughts abouthis family, his religion, and his reasons for selling Monticello.

Carroll’s observations are revealing. Levy’s account of his family history anddetails of his ownership of Monticello also are revealing, even as they also area mixture of fact and fantasy.

Carroll found Levy, whom he described as being six feet talland weighing 180 pounds, living with his younger brother, 67-year-old MitchellLevy, also a life-long bachelor. When Carroll arrived, he wrote, JeffersonLevy, was pacing “up and down in the drawing rooms” of his lavishtownhouse.

The place was packed with works of art, Carroll wrote,including “priceless vases from Sevres, crystal candelabra mounted upon costlybronze bases from Venice, a green malachite table worth $10,000 owned by a Czarof Russia, a bronze head done by the immortal David [d’Angers], a silvercarving from the hands of the famous Benvenuto Cellini and other wonderfultreasures and paintings.”

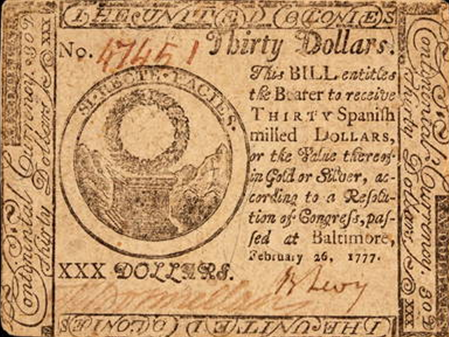

When Jefferson Levy began by talking about his family, hemistakenly claimed, as he had in other interviews, that he and his brother werethe last Levy descendants of Asa Levy, a Dutch Jew who had settled in New YorkCity (then New Amsterdam) in 1654; that the Philadelphia Revolutionary WarJewish patriot Benjamin Levy—one of the signers of Continental currency—was hisgreat-grandfather; and that his grandfather Michael Levy served in theContinental Army.

Continental Currency note signed by Benjamin Levy (‘B. Levy’),February 1777

Yes, we are the last of our line, my brother and I,”Jefferson Levy said, ignoring the fact that his sister Amelia was alive, aswere his late brother Louis’s four children and Amelia’s son Monroe.Plus, there is no evidence that Asa Levy (sometimes referredto as Asser Levy and Asser Levy van Swellem), had any children. Andgenealogical sources agree that Benjamin Levy’s children did not includeMichael Levy, LML’s grandfather—who did not serve in the Continental Army.

When Caroll asked about Monticello, Jefferson Levy claimedthat he and “members” of his family had invested a whopping $2.4 million in theproperty. “This huge expenditure," Levy said, “includes the original costof Monticello, the expenses of keeping it up, its restoration after the CivilWar and the interest on the money sunk in the property.”

Could that be true? The facts are that JeffersonLevy’s “original cost” for Monticello was just over $10,000 when he acquiredthe property in 1879. Uriah Levy had paid less than $3,000 when be bought it in1834. It is true that both Levys spent significant funds to repair, restore,preserve, and furnish the house and grounds (and add acreage) to the propertyover the following 80-plus years. But my guess is that all of thoseexpenditures didn’t add up to a figure close to $2.4 million—which would beworth more than $45 million in 2025.

Levy then told Carroll, disingenuously, that he had “alwayssaid [he] would sell Monticello to the Commonwealth of Virginia or to theUnited States or to an organization similar to that in control of Mount Vernon,George Washington’s home.” But, Levy said, “I was not going to be driven to dowhat I wanted to do all the time and had purposed doing from the veryfirst.”

It’s true that Jefferson Levy definitely did not like to be“driven” by others to do anything. Still, he had steadfastly and adamantlyrefused to listen to any suggestion that he sell Monticello to the federalgovernment or any other entity from the time he gained control of it in 1879until the fall of 1914. That’s when, most likely because of large stock marketand real estate losses, he abruptly reversed course, and announced that hewould sell the property, including the house’s furnishings, to the federalgovernment for $500,000.

Levy told Carroll that Cornelius Vanderbilt II onceapproached him with an offer on Monticello’s front lawn, saying: “Cannot Itempt you to sell [Monticello] with a million dollars? If not enough, name yourprice.” He said he turned down that offer and “scores” of others, including onefrom Andrew Carnegie. The Gilden Age industrialist approached Jefferson Levy inWashington, Levy said, and told him: “Any time you want to sell Monticello I’llbuy it and present it to the country.”

Although Vanderbilt and Carnegie conceivably could have madethose high-dollar offers to Levy for Monticello, it’s extremely doubtful that“scores” of Gilded Age millionaires were after him to sell.

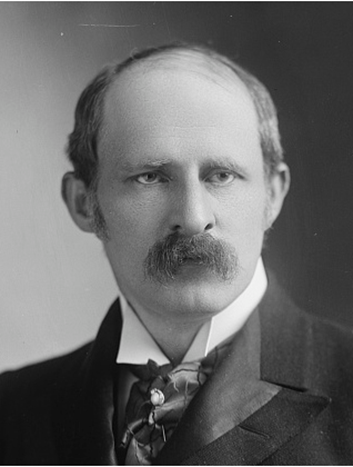

In the interview, Levy (above) offered thestartling and hitherto publicly unmentioned news that at the 1912 DemocraticNational Convention in Baltimore, he was offered the vice-presidentialnomination. The offer, he said, came with one caveat—that if he accepted andbecame VP, he’d donate Monticello to the government after the election.

Levy turned that offer down, he said, as well as a similarprevious one made by William Jennings Bryan.

“What they failed to recognize—all of them—was the fact thatperhaps there might be a pride in my own family connected with the ownership,”Levy said. “Once there was a time when I was wealthy enough to havestood the strain of an absolute gift of Monticello to the country. Then theyfought me. Now, when I am approached in a different spirit under conditionswhich I laid down from the start, it is financially necessary for me to allowothers to share in the great gift of the historic landmark to the nation.”

Jefferson Levy then showed Carroll his right hand, “uponwhich was a pigeon-blood ruby ring of antique pattern,” the reporter wrote.Levy said the ring had belonged to his uncle, Uriah Levy, and then launchedinto an exegesis on the Commodore’s naval career and his purchase ofMonticello, an account that rang completely true.

“Monticello was never looked upon by my uncle as aninvestment,” Jefferson Levy said. “He bought it out of deep admiration for thegreat Democrat.”

As he reflected on the pending sale and his family’s longhistory in America, Levy told Carroll: “The whole trouble started when theytried to force me to sell Monticello, and I fought them and beat them. I amproud of my country, my family and my race. We Levys were the first Jews toland in the New World [actually, other Levys were] and as the republic wasfounded and expanded, we did our share of the fighting.”

“That,” Levy said, “should entitle our family at least tosome consideration.”

EVENTS &COMMERCE: I have a growing number of events scheduled later year, most of them on Lafayette:Idealist General, my newly re-released concise biography of the famedMarquis, and my latest book, The Unlikely War Hero, a slice-of-lifebiography of the extraordinary Vietnam War story of Doug Hegdahl, the youngestand lowest ranking American prisoner held in Hanoi during the war.

I’m also doing talks, podcasts, and other events forthe paperback edition of Lafayette: Idealist General and, ofcourse, Saving Monticello. Many are speaking engagements forhistoric preservation and other groups. Most are open to the public. Fordetails, go to: marcleepson.com/events

If you’d like to arrange a talk on The Unlikely WarHero, Saving Monticello, Lafayette, or any of my other books,please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com Toorder signed copies from my website, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrdering

If you’d like to arrange a talk on The Unlikely WarHero, Saving Monticello, Lafayette, or any of my other books,please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com Toorder signed copies from my website, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrdering

July 22, 2025

July 2025

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest aboutthe book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor- Marc Leepson

VolumeXXII, Number 7 July2025

AI HISTORY: A few weeks ago, when I first beganseeing AI prompts on my Facebook pages offering more information on some aspectof what I was posting about, I found them annoying and ignored them. But theother day, after I’d posted about Saving Monticello and the documentary,“The Levys of Monticello,” Meta’s AI offered a link with the teasing question, “Howdid the Levy family restore Monticello?” and I couldn’t resist clicking.

How could I not? I’m always looking for new (to me) informationon the Levys and Monticello, most often material such as old newspaper articlesthat have been digitized and made accessible online since I did the researchfor the book in 1999-2001.

I have used Chat GBT occasionally over the years, mainly asa curiosity to see how accurate answers would be on subjects I knew a fairamount about. Most contained errors and not much more info than I could haveeasily found through a Google or other online search.

But I had read that AI had recently made great strides withaccuracy, so I clicked. Not this time, though.

I actually laughed out loud at that howler of a first sentenceand the ridiculous name, “Barclay Hazard Levy.” And the nonexistent “Barclayson” named, of all things, “James A. Levy.” And that the Levy Family “purchasedMonticello in 1923,” which was only off by 89 years.

To set the record straight, there was nosuch human being as “Barclay Hazard Levy,” much less him being a great grandnephewof Thomas Jefferson. Plus, the Levy Family didn’t buy Monticello from Uriah Levyin 1923. That would have been miraclulous as Levy had died in 1862.

As for what did happen in 1923, Uriah Levy’s nephew,Jefferson Monroe Levy, who had acquired the property by buying out his uncle’sother heirs in 1879, sold it that year—not to his long-dead uncle, but to the ThomasJefferson Memorial Foundation.

The only Barclay in the equation is James Turner Barclay (below),who bought Monticello from Jefferson’s heirs in 1831 and sold it to UriahPhillips Levy in 1834.

My advice: Don’t go to AI in search of the history of theLevy Family’s remarkable stewardship of Monticello. You can find the real names,dates, and lots more in Saving Monticello.

DR.SARNA: Soon after he received an honorary degree and gave the Keynotespeech at Brandies University’s undergraduate commencement on May 18, Dr.Jonathan Sarna, the eminent American Jewish History professor and prolificauthor, retired as a University Professor and the Joseph H. and Belle R. BraunProfessor of American Jewish History, Emeritus, at Brandeis, his alma mater.

If fact, the Keynote speech came on the fiftieth anniversaryof Dr. Sarna’s graduation from Brandeis in 1975 with a bachelor’s and a master’sdegree in Judaic Studies. The following year, he received an MA in history fromYale University; and went on to earn a history Ph.D. from Yale in 1979.

Dr. Sarna—a long-time subscriber to this newsletter—didpost-doctoral work for eleven years at the American Jewish Archives at HebrewUnion College in Cincinnati, then returned to his alma mater, where he spentthe next 35 years teaching Jewish American history at Brandeis.

A former president of the Association for Jewish Studies andthe Chief Historian at the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History inPhiladelphia, Dr. Sarna (above) has written or edited more than two dozen books on AmericanJewish History. That includes his encyclopedic American Judaism: A History,and Jacksonian Jew: The Two Worlds of Mordecai Noah, a 1981 biography ofthe famed nineteenth century journalist and diplomat Mordecai Manuel Noah (1785-1851), a second cousin of Uriah Levy, whom mentionin Saving Monticello.

Just like any other writer who deals with American JewishHistory, I have sought Dr. Sarna’s advice more than once. He always hasresponded graciously and has helped me immensely.

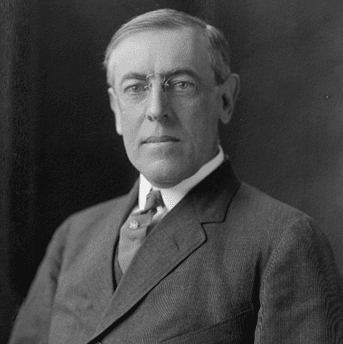

W. WILSON: As I wrote in Saving Monticello,before, during, and after his two-term presidency (1913-21), Woodrow Wilson wasa strong supporter of Maude Littleton’s campaign to have the U.S. government condemnMonticello, take it from Jefferson Levy, and turn it into a government-runhouse museum.

During the hotly debated attempt in Congress in 1912 overlegislation that would have put Littleton’s campaign in motion, the thenDemocratic Governor of New Jersey wrote to her, saying he supported her mission“with all of my heart.”

As the campaign continued in 1914, Maude Littleton (inthe dark dress in the photo) let it be known, including during testimony beforea Senate committee that year, that she that spoken to Wilson “many times on this question,” and reported thatthe President was strongly in favor of government ownership, “even throughcondemnation.”

The next year Wilson actively lobbied Senate and House leaders forpassage of a resolution that would have condemned Monticello and turned it overto the government. It didn’t pass.

In the summer of 1916, a largedelegation of DAR members, headed by the organization's president general, DaisyAllen Story, met with Wilson at the White House to lobby him to help to continueto use his influence to encourage Congress to approved a piece of legislation thatwould authorized the government to purchase Monticello.

“The President told the delegation he was in favor of the $500,000 calledfor in the bill to purchase the property,” the Charlottesville Daily Progress reported, “and would givehis influence and aid having the bill passed.” It didn’t.

In 1917, Congress lost interest in thematter after the U.S. entered World War I. After the war ended in 1918, Levy putMonticello on the market and a real estate broker began marketing the propertyin the spring of 1919. As readers of Saving Monticello well know, Monticellodid not sell until 1923.

I sketched Wilson’s involvement in MaudeLittleton’s campaign to wrest Monticello from Jefferson Levy in the book. Onesmall but intriguing piece of that story that I only discovered recently isthat Levy took it upon himself to go to the White House on October 2, 1919, toinvite the president to come to Monticello, as a newspaper article put it, to “regainhis health.” Levy, the article went on to say, “was not permitted” to seeWilson.

Three days later, Woodrow Wilson (above) had amassive stroke, and was incapacitated for the rest of his term in office. He diedon February 3, 1924, at 67. Jefferson Monroe Levy died a month and three dayslater, on March 6, 1924, five weeks short of his 72nd birthday—and a littleover two months after he had sold Monticello to the Thomas Jefferson MemorialFoundation.

EVENTS & COMMERCE: I have a growing number of events scheduled laterthis summer and into the fall, most Lafayette: Idealist General, my newlyre-released concise biography of the famed Marquis, and my latest book, TheUnlikely War Hero, a slice-of-life biography of the extraordinary VietnamWar story of Doug Hegdahl, the youngest and lowest ranking American prisonerheld in Hanoi during the war.

I’m also doing talks, podcasts and other eventsfor the paperback edition of Lafayette: Idealist General and, of course,Saving Monticello.

Many are speaking engagements for historicpreservation and other groups. Most are open to the public. For details, go to: marcleepson.com/events

If you’d like to arrange a talk on The UnlikelyWar Hero, Saving Monticello, Lafayette, or any of my otherbooks, please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

To order signed copies from my website, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrdering

June 27, 2025

June 2025

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest aboutthe book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor- Marc Leepson

VolumeXXII, Number 6 June2025

RELIGIOSITY: SavingMonticello, is, at its heart, as the title indicates, a story of historicpreservation. But it also deals with Thomas Jefferson and his architectural prowess.And it includes a compelling story of not-widely-known Jewish-American history.

Said history begins with a group of Portuguese Sephardic Jewswho fled their homeland during the Inquisition in the early eighteenth century. They made their way to England, and in the spring of 1733 crossed theAtlantic (along with some Ashkenazi Jews from Germany), landing in Savannah,Georgia, on July 11, not long after the colony of Georgia had been founded.

That group included a prominent physician Dr. Samuel Nunez,Uriah Levy’s great-great grandfather, along with his wife Gracia (who changedher name to Rebecca in England) and their six children. One of the first thingsthe group of Sephardic Jews—who were forbidden under the punishment of death topractice their religion in Portugal—did after arriving in Savannah was establisha synagogue they called Kahal Kadosh Mickva Israel (Holy Congregation,the Hope of Israel). Known since 1790 as Congregation Mickve Israel, it is thethird-oldest Jewish Congregation in the nation.

Without doubt, the Nunez family members were devout Jews. As for theirdescendants—including Uriah Levy and his nephew Jefferson M. Levy—weknow through their words and deeds they were proud Jews. However, the historicalevidence strongly suggests that Uriah and Jefferson Levy and other Nunez descendantswere not particularly “religious,” as it’s clear that they did not regularlyattend synagogue services nor took part in other aspects of Judaism such asholding Passover seders and celebrating bar and bat mitzvahs.

What follows is a concise rundown on some of thatdistinguished and accomplished family members’ religiosity.

As I wrote in Saving Monticello, Dr. Nunez (known inPortugal as Samuel Nunes Ribiero) became a close friend of John Wesley, the founder ofthe Methodist Church, when the English cleric lived in Savannah in the mid-1730s.And as we have seen, Dr. Nunez was one of the founders of Mickve Israel, whichto this day uses the Torah that the Jewish settlers brought with them on theirvoyage to Georgia in 1733.

Soon after the Nunez family arrived inSavannah, 19-year-old Maria Caetana Nunez (known as Zipporah), Samuel andRebecca’s oldest daughter, married David Mendes Machado, 38, anotherSephardic Jew who had sailed from London, although he may have arrived severalyears before the Nunez Family and the other 1733 settlers did.

David Machado was a member of another well-to-do Portuguese crypto-Jewishfamily. He was a theologian and a scholar who was an expert in Hebrew andJewish traditions, even though he had been forced to live as a Catholic in Portugal.

Less than a year after the wedding, David and Zipporah Machado moved toNew York City. They came north after he was appointed hazzan at CongregationShearith Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, the first Jewishcongregation established in North America. Shearith Israel was founded in 1654.

Jonas Phillips (below), Uriah Levy’s German-bornAshkenazi Jewish maternal grandfather, born Jonah Phaibush, arrived in Charleston. South Carolina, in 1756 toseek his fortune at age 21. A few years later, Jonas Phillips moved to Albany,New York, where he became a Freemason and opened a store in which he sold foodand spirits.

After leaving Albany, he married Rebecca Machado (a daughter of David andZipporah) in 1761, and settled in New York City where he operated a retailstore. He also served the Jewish community as a shohet (ritualslaughterer) and bodek (meat examiner). Jonas became a naturalizedcitizen in April 1771. A few years later he moved his family to Philadelphiawhere he opened another retail store.

His most famous public religious act was the September 7, 1787, letter Jonas Phillips wroteto the Constitutional Convention, which was debating what would become the U.S.Constitution. Identifying himself as “one of the people called Jews of the Cityof Philadelphia,” he called on the body to provide “all men” in theConstitution the “natural and unalienable Right to worship almighty Godaccording to their own Conscience and understanding.”

Jonas Phillips was instrumental inraising funds to purchase a new building for Mikveh Israel Synagogue inPhiladelphia in 1782, and was elected the president of that Spanish andPortuguese Congregation, which had been established in 1740. As the head of thecongregation, he invited George Washington to attend the dedication ceremoniesof its new building.

Uriah Levy’s second cousin, MordecaiManuel Noah (1785-1851), a well-known American diplomat and journalist, wasthe recipient of a famous letter from Thomas Jefferson in which the Sage ofMonticello expressed his views on freedom of religion and Judaism.

In 1818, Mordecai Noah (below)—one of thebest-known American Jews in the Early Republic—had given a speech at ShearithIsrael in New York, a copy of which made its way to Monticello. Jefferson wroteto Noah on May 28, saying he had read the speech “with pleasure andinstruction, having learnt from it some valuable facts about Jewish historywhich I did not know before.”

Jefferson went on to denounce“religious intolerance,” which he called “a vice.” He concludedthat the only “antidote” to religious intolerance would be federal laws thatprotected “our religious as they do our civil rights by putting all on an equalfooting.”

As for Uriah Levy, a late 20th century magazine articleabout him bore the headline, “When Monticello had a Mezuzah.” Even though the wordswere not meant to be taken literally, a careful search in recent years forsigns that one or more mezuzahs adorned door frames at Monticello during the long(1834-1923) Levy Family ownership came up empty.

That absence is another reason that historians believe that—thoughUriah Levy was an outspoken and proud Jew; was the victim of viciousanti-Semitism during his 50-year Navy career; and an ardent admirer of ThomasJefferson because of his dedication to religious freedom—there is little evidence that he formallypracticed the religion of his ancestors.

Levy likely limited his Judaic practice to being a member of ShearithIsrael in New York where his great grandfather David Machado had served ashazzan a century before. And by becoming the first president of WashingtonHebrew Congregation, which formed in 1852.

Oneother thing: As I noted in Saving Monticello, in 1855, Uriah Levy, alongwith many other naval officers, had been dropped from the Navy's active-dutylists. He fought his removal and based his defense on anti-Semitism. During alengthy trial, Levy made a long passionate speech in which he trumpeted hisJudaism.

“My case,” he said, “is the case of every Israelite inthe Union.” He then asked rhetorically: “Are the thousands of [Jewish people],in their dispersion throughout the earth, who look to America as a land brightwith promise, are they now to learn, to their sorrow and dismay, that we toohave sunk into the mire of religious intolerance and bigotry?”

Electedto the Jewish American Hall of Fame in 1988, UPL was honored by the U.S. Navywith the naming of a World War II destroyer escort the U.S.S. Levy. And the first permanent Jewish Chapel built by American armedforces, the Commodore Levy Chapel at the Naval Station in Norfolk, Virginia, wasdedicated in his name in 1959.

Notto mention the U.S. Naval Academy’s imposing Commodore Uriah P. Levy JewishCenter and Chapel (in photo, above), which opened its doors in 2005.

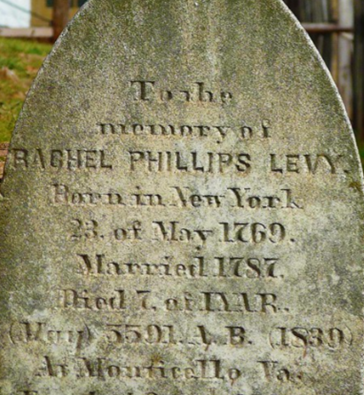

Andthere’s this: The tombstone Uriah Levy later erected on his mother’s grave atMonticello (below) includes the Hebrew month and year of her death. It is inscribed: “Tothe memory of Rachel Phillips Levy, Born in New York, 23 of May 1769,Married 1787. Died 7, of IYAR, (May) 5591, A.B. (1839) at Monticello, Va.”

One of Uriah Levy’s brothers, the peripatetic sea captainJonas Phillips Levy, like his brother Uriah, took part in religious affairs in themid-nineteenth century, and seems to have taken a bigger role in practicinghis religion. At least he did when he and his family were living in theNation’s Capital in 1862 and he became an active member of Washington HebrewCongregation and is credited with making the first monetary contribution to thatsynagogue after its founding that year.

As for Jonas’ son, Jefferson Levy, theglobe-trotting Gilded Age millionaire real estate and stock speculator andthree-term member of Congress from New York City, seems not to have beenparticularly religious.

He likely was a member of Shearith Israel, since he isburied in Beth Olam Cemetery in Queens, near his Uncle Uirah, in asection associated with Shearith Israel. His gravestone contains no Hebrewwords, though. JML’s brother and business partner, L.Napoleon Levy (1854-1921), on the other hand, was a mover and shaker at ShearithIsrael.

As I noted in thisnewsletter two years ago, L.N. Levy served as the congregation’s president formuch of the time between 1895 and 1921, the year of his death 1921.

EVENTS AND COMMERCE: I have a growing number of events scheduled laterthis summer and into the fall, most of them for my new book, The UnlikelyWar Hero, a slice-of-life biography of the extraordinary Vietnam War storyof Doug Hegdahl, the youngest and lowest ranking American prisoner held inHanoi during the war.

I’m also lining up talks, podcasts and other events for thenew paperback version of Lafayette: Idealist General.

Many of my upcoming events are speaking engagementsfor historic preservation and other groups. Some are open to the public. For details, go to this page on my website: marcleepson.com/events

If you’d like to arrange a talk on The Unlikely War Hero, SavingMonticello, Lafayette, or any of my other books, please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

To order signedcopies of my books, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrdering

This issue is dedicated in loving memory to my brother, Evan Leepson(July 18, 1947 – June 12, 2025), a man of deep religious faith.

May 16, 2025

May 2025

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest aboutthe book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor- Marc Leepson

VolumeXXII, Number 5 May2025

Both spoke French; they found that they shared an affinityfor the tenets of the Enlightenment; and they became life-long friends.

The men cemented that friendship in 1785 when the ContinentalCongress sent Jefferson to Paris to succeed Benjamin Franklin as the U.S. Minister(Ambassador) to France. Jefferson and Lafayette became confidants as Lafayettetook an increasingly active part in French nationalaffairs.

Lafayette, circa 1825

Lafayette, circa 1825

As a member of the Assembly ofNotables, Lafayette was an outspoken proponent of establishing a constitutionalmonarchy with guarantees of individual freedom and a republican—versus anunfettered monarchical—government. In other words, what he fought for duringthe American Revolution against the British..

Lafayette wrote the Declaration of theRights of Man and the Citizen in 1789, a seminal document that had manysimilarities to James Madison’s Bill of Rights and to the Declaration ofIndependence, which Thomas Jefferson was instrumental in writing.

Lafayette’s’ Declaration,which became the preamble to the French Constitution, in fact, included nearlythe same “all men are created equal” language as Jefferson’s Declaration did.

Fast forward to Lafayette’s famed thirdand final tour of the United States. The one in which the American publictreated the man known as “our Marquis” like a 21st century rock star.Everywhere he went—and he went just about everywhere, visiting all 24 statesfrom July 1824 to September 1825—crowds gathered by the thousands to honorthe Frenchman who served with distinction during the Revolutionary War, at countlessdinners, galas, parades, ceremonies and other events.

One memorable event took place inNovember 1824 when Lafayette and his small entourage paid a visit to an ailingThomas Jefferson at Monticello, I described that emotional occasion describedbriefly in Saving Monticello and in this newsletter, and elaboratedon in the Lafayette book.

The Marquis and his party spent ten days enjoyingJefferson's hospitality and being feted at the University of Virginia. This wasthe visit after which Jefferson wrote to a friend that he had to replenish hisstock of red wine after the Frenchman left.

Lafayette stopped by again just before he left for home. In August 1825, butstayed only a short time as Jefferson was ill. He died less than a year lateron July 4, 1826.

Bill Barker & Charles Wissinger

Bill Barker & Charles Wissinger as Jefferson and Lafayette

at Monticello in November 2024

UPL & THE MARQUIS: Back in 2011 during the Q&A after my talk, an audience member askedme if Uriah Levy and Lafayette had ever crossed paths. The answer was yes. And theirmeeting, in 1833 in Paris, had important ramifications for the future ofMonticello

Uriah Levy, in the French capital between Navy postings, sought out the famedsculptor David d’Angers and commissioned a full-length marble sculpture ofThomas Jefferson. Then Levy called on the aging Marquis, telling himabout his plans for the statute and asking to borrow a portrait of Jefferson byThomas Sully that Lafayette had for the sculptor to use for the image ofJefferson’s face.

During that meeting, it’s likely that Lafyette, whocorresponded with Martha Jefferson Randolph in Virginia, asked Levy to returnthe favor by checking check on her, the family, and Monticello. Levy agreed.

That is one feasible reason why Levy booked passage on acoach from Philadelphia to Charlottesville in the spring of 1834. When he arrived in Charlottesville, Levy found that Martha Randolphand the family were well, but that James Turner Barclay—who purchased Monticellofrom the Randolph’s in 1831—was anxious to sell the property. Soon thereafter, inApril 1834, Levy signed a contract with Barclay to purchase Monticello and its219 acres. The rest is history—the history that I tell in Saving Monticello.

Not to bury the lead, but this tale of Lafayette, Jefferson,and Levy came to mind because the University of Virginia Press has justpublished a second edition of my Lafayette: Idealist General inpaperback in conjunction with the two hundredth anniversary of the Marquis’famed farewell tour

It’s available on the online booksellers and at your localbookstore. For a personally autographed copy, please go to this page on my website, https://bit.ly/BookOrdering. I’llfulfill your order as soon as I receive it.

EVENTS AND COMMERCE: I have a growing number of events scheduled thisspring and summer, most of them for my new book, The Unlikely War Hero, aslice-of-life biography of the extraordinary Vietnam War story of Doug Hegdahl,the youngest and lowest ranking American prisoner held in Hanoi during the war.

I’m also lining up talks, podcasts and other events for thenew paperback version of Lafayette: Idealist General.

Many are speaking engagements for historicpreservation and other groups. Some are open to the public. For details, go to this page on my website: marcleepson.com/events

If you’d like to arrange a talk on The UnlikelyWar Hero, Saving Monticello, Lafayette, or any of my otherbooks, please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

To order asigned copied, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrderingI also have new paperback copies of Flag: An American Biography; DesperateEngagement; and The Ballad of the Green Beret.

April 28, 2025

April 2025

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest aboutthe book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor- Marc Leepson

VolumeXXII, Number 4 April2025

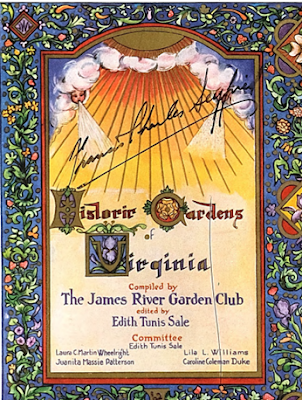

THE GARDENS: Apropos of Historic Garden Weekin Virginia from April 26-May 3 this year—and the fact that the annualstatewide event began in 1927 when the Garden Club of Virginia held a flower showto raise funds to preserve trees on Monticello’s lawn planted by ThomasJefferson—I thought about what I wrote about the mountaintop’s extensive flowergardens in Saving Monticello.

Mea culpa: I didnot go into depth on the subject in the book. However, I did note that JamesTurner Barclay, who purchased the property in 1831 from the Randolph familyfive years after Jefferson’s death, at the very least did not properly care forthe Sage of Monticello’s Jefferson’s carefully planned and cultivated flowergardens—primarily the twenty oval-shaped beds planted with different flowers aroundthe house and encircling the West Lawn.

I extensively covered Jefferson Levy’s work repairing andrestoring Monticello itself after taking ownership in 1879 at a time when thehouse was in terrible condition after nearly twenty years of neglect. And Iwrote that he, didn’t get around to working on refurbishing the gardens untilnear the turn of the 20th century.

Jefferson’s “orchards and terraced gardens, the serpentineflower-borders on the western lawn, and the beautiful ‘walkabout’ walks anddrives have all disappeared,” a visitor to Monticello wrote in 1887. Not longafter that, Levy vowed to restore Monticello’s grounds “as nearly as possibleto its condition in Jefferson's time.”

Less than ten years later, in April1898, the Charlottesville Daily Progressreported favorably on recent work Levy had done on the grounds. “The banks oneither side of the drive from the porter’s lodge to the mansion have been sewnwith grass seed, and at intervals rare and beautiful flowers have been planted,which are now blooming,” an April 28 article said. “The lawns are in perfectsod and on them are late acquisitions of flowering shrubs.”

****************

I recently discovereda few more details about how Jefferson Levy continued lavishing attention onthe grounds until he sold the property in 1923 to the Thomas Jefferson MemorialFoundation. The info came from a short chapter in Historic Gardens ofVirginia, a book published in 1921 by the James River Garden Club, which hadbeen founded in 1915 in Richmond.

The book’s three-page report on Monticello, written by theclub’s founder, Juanita Massie Patterson, offers a look at the gardens andgrounds at the time, and credits Jefferson Levy for not making any changes to“the house and gardens,” and for “restoring Monticello to its original beauty.”

Patterson startswith describing what she saw as she entered the property through a gate at the“outer entrance” at the gatekeeper’s lodge that Levy had recently built.

“The drive to the house” from there to the house, she wrote,goes through “the woods…, enchanting in early spring. [T]he luxuriant growth ofScotch broom, with its pendant yellow blossoms, carpets the ground beneath,forming a veritable cloth of gold.”

The drive took her past the Jefferson family graveyard, thenthrough a gate that opened onto the West Front’s lawn. The garden there, shewrote, “is arranged in a chain of rectangular plots, with grass walks between.”

Just before getting to the house, she wrote, “may still beseen the old-time shrubs on either side of the path leading to the house. Alarge club of lilacs and syringa with modern privet hides the exit of theunderground passage to the house.”

By the way, in homage to Thomas Jefferson’s “revolutionary”gardening, the Shops at Monticello offers a large selection of heirloom seedsand plants for sale at the mountaintop’s Center. Many also can be ordered online throughout the years at https://bit.ly/MontGardensTo scroll through Monticello’s All Plants Archive, go to https://bit.ly/PlantArchive

EVENTS AND COMMERCE: I have a growingnumber of events scheduled this spring and summer, most of them for my newbook, The Unlikely War Hero, a slice-of-life biography of theextraordinary Vietnam War story of Doug Hegdahl, the youngest and lowestranking American prisoner held in Hanoi during the war.

Many are speaking engagements for historicpreservation and other groups. Some are open to the public. For details, go to this page on my website: marcleepson.com/events

If you’d like to arrange a talk on The UnlikelyWar Hero, Saving Monticello, or any of my other books, please emailme at marcleepson@gmail.com The book is now in its fourth printing, witha fifth on the way.

To order asigned copy, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrderingI also have new paperback copies of Saving Monticello, as well as copies of Flag: An American Biography; DesperateEngagement; and Ballad of the Green Beret.

March 19, 2025

March 2025

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest aboutthe book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor- Marc Leepson

VolumeXXII, Number 3 March2025

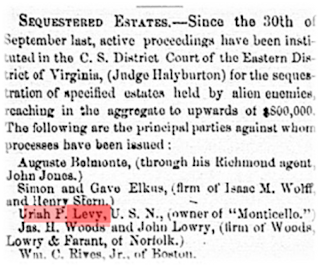

ALIEN ENEMIES: The bizarre, out-of-the-blue invokingof 1798 Alien Enemies Act during peacetime by the current U.S. president todeport undesirable Venezuelan “aliens” brought to mind something I discoveredwhile doing the research for Saving Monticello twenty-five years ago:another North American Alien Enemies Act, this one a Civil War law enacted inthe Confederate States of America’s Congress in August 1861, less than fivemonths after the conflict began.

The “alien enemies” in question inthis case were citizens of non-rebelling states who owned property in the elevenConfederate states. The law mandated the removal of said residents from thosesouthern states. It also authorized the seizing of property in the South ownedby the ousted non-southerners.

That included Monticello since theproperty’s then-owner, U.S. Navy Captain Uriah P. Levy, lived most of the yearin New York City when the War of 1812 veteran wasn’t sailing the seven seas.

Proceedings began on October 10, 1861, to “sequestrate‘Monticello’ as the property of an alien enemy,” the Richmond Examiner reported,since “the present owner, Levy, [was] abroad… in charge of a United States shipof war.” Actually, Levy was in Washington, D.C., at that time, preparing to take over the Navy’sCourt-Martial Board.

The Examiner felt the need toout point out that the “people of Charlottesville” called “the late owner ofMonticello ‘Commodore Levee.’ He is a first Captain in the United States Navy,and of Jewish parentage.”*

Monticello “has been confiscated,” Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper reportedfour months later, “with all its lands, negroes, cattle, farming utensils,furniture, paintings, wines, etc., together with two other farms belonging tothe same owner, and valued at from $70,000 to $80,000.” That New York newspaperwent on to expound on Uriah Levy’s patriotism and military service, andconcluded: “Certainly no officer in the army or navy has been so victimized bythe rebels.”

Uriah Levy fought the confiscation in the Confederate courts.After he died on March 22, 1862, his estate’s lawyer, George Carr, continuedpressing the case. The CSA finally prevailed legally on September 27, 1864, ata time when the South’s treasury was in dire need of cash.

On November 17, an auction took place on the mountaintop. Monticello, itsgrounds and its contents, and hundreds of acres of land Levy had purchased aroundCharlottesville were put on the block. So were Levy’s enslaved people.

What a New York Timescorrespondent on the scene termed “a large number of people” showed up for thesale. That included Uriah Levy’s brother Jonas, then living in Wilmington,North Carolina, who had his eye on buying the house.

The crowd also included Lieutenant Col. Benjamin FranklinFicklin, Jr., of the 50th Virginia Regiment, who outbid Levy andeveryone else and plunked down $80,500 in Confederate money for Monticello andits adjoining acreage. Levy’s estate, under terms of the act, was not compensated.

As I wrote in the book, Ficklin (below) also bought a bust of Jefferson for $50. OtherLevy items sold that day included a pianoforte, a marble-topped sideboard, awashstand, cattle, oxen, a threshing machine, and 19 enslaved people. JonasLevy paid $5,400 for an enslaved man named John, and took home a model of oneof his brother’s ship’s, the Vandalia, for $100. The CSA’s total takewas $350,000.'

Ficklin—a colorful and adventurous character, had been wounded in theMexican War and later went on to be one of the founders of the legendary PonyExpress. He returned to his regiment after the auction, and most likely neverspent a night in the house that Jefferson built,

Although the sale took place in November 1864, Ficklin did not receivetitle from the District Court until March 17, 1865, three weeks before Leesurrendered to Grant at Appomattox ending the war. According to Ficklin familylore, Benjamin Ficklin, a bachelor, brought his aging father, Rev. Ficklin, tolive at Monticello,where he died.

Other reports indicate that severalother members of the family moved into Monticello, including Capt. Ficklin'syoungest sister Susan and her husband Joseph Hardesty, and a brother known as “DissoluteWillie.” A family story has it that Willie sold some of the Jefferson furnitureleft in the house to pay gambling debts, and that their father died inJefferson’s bed.

For his part, B.F. Ficklin, Jr., whois buried in Maplewood Cemetery in Charlottesville, died at age 44 while dining at the Willard Hotel inWashington when a fishbone lodged in his throat and the doctor who tried toremove it severed an artery.

* Uriah Levy was given the command of the U.S. Navy’sentire American Mediterranean Squadron on January 7, 1860, a position thatentitled him to the honorary rank of Commodore. Although he never wascommissioned a commodore, the Navy officially recognized him as one and referredto him as a Commodore in all official communications.

THE AI STATUE: In the Januaryissue I mentioned that I’d recently learned that in 1881, two years after he acquiredMonticello from his uncle’s estate, Jefferson Monroe Levy (a son of Jonas Levy)had written an article in which he said he would donate $500 toward “theerection of a statue of Jefferson in Central park [sic]” in New York City.

I confirmed that no suchstatue ever was erected, but that new information got me thinking about what an1880s statue in Central Park would look like. I decided, for the first time, toask an AI website to create an image. I was singularly unsuccessful.

When I mentioned that to Hunt Lyman, an old friend who hasstudied and written about AI for several years, he said he’d take a look. Inless than a New York minute—or so it seemed—Hunt came up with the image below.

I think it looks convincing, though I’m not sure why thestatue would be in the middle of a walkway. Plus, I had to laugh at the“Central Park” sign on the lamppost.

EVENTS AND COMMERCE: I have a growingnumber of events scheduled starting this spring and summer, most of them for mynew book, The Unlikely War Hero, a slice-of-life biography of theextraordinary Vietnam War story of Doug Hegdahl, the youngest and lowestranking American prisoner held in Hanoi during the war. Many are speaking engagementsfor historic preservation and other groups. Some are open to the public. Fordetails, go to this page on my website: marcleepson.com/events

If you’d like to arrange a talk on The UnlikelyWar Hero, Saving Monticello, or any of my other books, please emailme at marcleepson@gmail.com The book is now in its fourth printing, witha fifth on the way.

To order asigned copy, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrderingI also have new paperback copies of Saving Monticello, as well as paperbackcopies of Flag: An American Biography;Desperate Engagement; and Ballad of the Green Beret

February 18, 2025

February 2025

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest aboutthe book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor- Marc Leepson

VolumeXXII, Number 2 February2025

THEBACHELORS:Coincidence or not, both Uriah Levy and his nephew Jefferson Monroe Levy werelong-time bachelors. Uriah married late in life (more on that below), and,like his life-long, never-married nephew, he did not have any children.

Valentine’s Day month 2025 seems like an appropriatetime to look at the love lives of the two men who owned (and repaired,preserved, and restored) Monticello from 1836 when Uriah Levy took ownership ofthe estate, to 1923 when Jefferson Levy sold it to the just-formed Thomas JeffersonMemorial Foundation.

Uriah Levy led a bachelor’s lifeuntil his 61st year in 1853 when he courted and married Virginia Lopez, who wasborn on September 25, 1835, less than a year before Uriah Levy took possessionof Monticello. She was 18 years old.

That may seem atad scandalous, but consider, too, that Virginia Lopez was Uriah Levy’s niece, theyoungest of the three children of Uriah’s sister Frances (known as Fanny) andAbraham Lopez, who lived in Kingston, Jamaica.

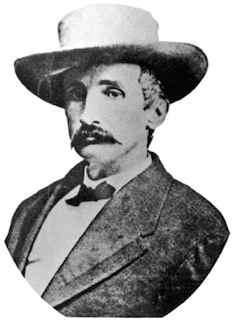

The only known photograph of Uriah Levy, takenjust prior to his death in 1862

In taking Virginia’s hand in marriage, as I noted in SavingMonticello, Uriah was following an ancient, if obscure, Jewish traditionthat obligated the closest unmarried male relative of a recently orphaned orwidowed woman in financial difficulties to marry her. Said financial troublesall but certainly stemmed from the fact that Abraham Lopez—sometimes referredto as Judge Lopez—had fallen on hard financial times by the time he died in 1849when Virgina was 14 years old. Before that, however, he had prospered andprovided well for his family. The well-off Lopezes had the wherewithal, for onething, to send Virginia to boarding school in England.

In the absence of thediscovery of a marriage license or any other primary sources to prove it, itappears that the May-December couple wed in the fall of 1853. And that the nuptialstook place in New York City where Uriah lived and where Virginia and her motherFanny moved from Jamaica sometime after Judge Lopez’s death four years earlier.We also know that sometime after the wedding, Uriahmoved Virginia and Fanny into his large townhouse at 107 St. Mark's Place inthe East Village in Manhattan.

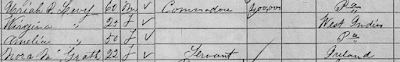

Fanny Levy died in 1857 and sometime after that Uriah’s unmarried sister,Amelia, moved into the house on St. Mark’s with her brother and youngsister-in-law, Virginia. We know that because in 1860 the U.S. Census (above)listed Commodore and Virginia Levy, age 60 and 25, living in Manhattan, alongwith Amelia Levy, 50, and an Irish servant named Nora McGrath, 22. Uriah andAmelia’s places of birth were listed as Philadelphia and Virginia’s as “WestIndies.”

Uriah Levy died at age 70 in thathouse on March 22, 1862. Virginia Lopez Levy later remarried and died on May 5,1925 in New York at age 90—63 years after Uriah Levy’s death.

****************

As for the lifelong bachelor Jefferson Levy, whowas born in New York in 1852—the year before UPL and Virginia Lopez married—hisname regularly popped up in the society pages of the (many) New York Citynewspapers and those in Washington, D.C., and Virginia, as he led anextravagant Gilded Age lifestyle after making a fortune in real estate andstock speculation in the 1870s and ‘80s.

Jefferson Levy traveled widely andoften, typically in the company of other upper-crust late nineteenth and early twentiethcentury globetrotters.

Jefferson M. Levy

Jefferson M. LevyOn one of his many social sojourns, JeffersonLevy crossed the Atlantic to spend some leisure time in England in the summerof 1902. The man the Washington Postdescribed as “one of the most conspicuous bachelor hosts of the London season,”among other things, gave a dinner at a fancy London hotel in August in theearly days of the reign of King Edward VII and its Edwardian Era upper class excesses.

Jefferson Levy, who, like his uncle, livedin New York City, repaired to Monticello early in September that year, where hethrew a big party for the artist George Burroughs Torrey (1863-1942), who hadpainted a portrait of Levy that he had placed in Monticello.

The conspicuous bachelor sometimes was linked to eligible woman of hissocial strata, but no evidence has surfaced that he came close to marrying. Levy,it appears, was very comfortable in his bachelorhood. For example, in thesummer of 1912, when rumors circulated in Washington that he was engaged to bemarried to Flora Wilson, the socially prominent daughter of Secretary ofAgriculture James Wilson*, Levy—a Democratic congressman from New Yorkat the time—picked up his phone and called The New York Times to set therecord straight.

In a short article in the September 3, 1912 Times,oddly headlined “L.M. Levy Is Not to Wed,” the paper noted that Levy called theTimes’ Washington office from Monticello to let the paper know there wasno truth to the rumor.

That was the summer in which Levy faced anationwide effort by Maude Littleton to induce Congress to take Monticello fromhim and turn it into a government-run presidential house museum—an effort hevigorously opposed in congressional hearings and in the court of publicopinion.

The rumors that he was engaged to Flora Lewis—a suffragist andtrained coloratura operatic soprano—had “no other basis than the possibledesire of somebody to make capital out of the fact that Miss Wilson recentlycame to his rescue by publicly declaring against the federal acquisition ofMonticello over his protest,” The Times reported.

“Mr. Levy said heregretted the report of an engagement and there was no foundation for it.”

Flora Wilson, 1912

Flora Wilson, 1912

*A former Congressman from Iowa, James Wilson hadserved as the Secretary of Agriculture since 1897. He stepped down early in1913, and has the distinction of being the longest-serving Cabinet secretary inU.S. history.

EVENTS AND COMMERCE: I have a growing number of events scheduledstarting in March, most of them for my new book, The Unlikely War Hero, aslice-of-life biography of the extraordinary Vietnam War story of Doug Hegdahl,the youngest and lowest ranking American prisoner held in Hanoi during the war.For details on upcoming events, check the Events page on my website: marcleepson.com/events

If you’d like to arrange a talk on The UnlikelyWar Hero, Saving Monticello, or any of my other books, please emailme at marcleepson@gmail.com

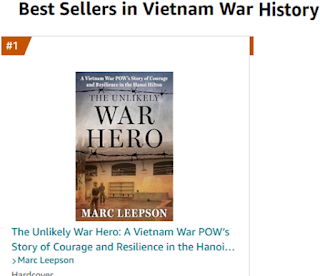

The UnlikelyWar Hero’s first printing sold out before the official December 17publication date and it became the Number 1 bestselling Vietnam War Historybook on Amazon. The second printing sold out not long after it came out inmid-January, and the book is now in its third printing.

I have a fewcopies of the first printing. To order one, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrdering I also havebrand-new paperback copies of SavingMonticello and a few as-new hardcovers, as well as paperback copies of Flag: An American Biography; DesperateEngagement; and Ballad of the Green Beret.

To order personalized, autographed book, go to bit.ly/BookOrdering or email me directly at marcleepson@gmail.com

January 20, 2025

January 2025

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest aboutthe book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor- Marc Leepson

VolumeXXII, Number 1 January2025

MEMORIALS& MONUMENTS: Thefounders of the foundation that formed to buy Monticello in 1923 from JeffersonLevy incorporated under the name, The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation.That’s presumably because the foundation’s goal, in the parlance of the times,was to own and operate Monticello as a “memorial” to Thomas Jefferson. The organizationdropped “Memorial” from its name in 2000.

This mini rumination on the word“memorial” was spurred by my continuing search for information about the Levy Familyand Monticello. That quest recently led me to an 1881 newspaper article I hadn’tseen (Thank you, Library of Congress’ Chronicling America historical newspaperdatabase) with an intriguing tidbit about Jefferson Levy that I hadn’t come across.

Said article was penned by Lyon Gardiner Tyler(1853-1935), a son of President John Tyler, and published in The MemphisDaily Appeal on January 2, 1881. J.G. Tyler, an 1875 graduate of theUniversity of Virginia, was the principal of a private school in Memphis at thetime. He went on to serve as President of the College of William andMary—Thomas Jefferson’s alma mater—from 1888-1919.

While expounding on the greatness of the Sage ofMonticello, J.G. Tyler mentioned that he had learned that Jefferson Levy—whohad owned Monticello for less than two years at that point—had written anarticle in which he said he would donate $500 toward “the erection of a statueof Jefferson in Central park [sic]” in New York City. As that was news to me, Itried to confirm it, or at least find more information about the proposed statue.Searching through the best primary sources, though, I couldn’t find anythingmore on it.

I therefore can only speculate that Jefferson Levy’sreverence for Thomas Jefferson and his desire to help build a monumental statuewas influenced by his uncle Uriah Levy’s decision to buy Monticello in 1834 outof admiration for Jefferson, especially his strong support for freedom ofreligion.

A year earlier, when then U.S. Navy Lt. Uriah Levy was in France, heexpressed that reverence by commissioning a full-length statue of Thomas Jeffersonby the top sculptor of the day, David d’Angers, which today is prominentlydisplayed in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. I wrote about UPL and the statue in SavingMonticello and in several issues of this newsletter.

There are a slew of statues in Central Park—from HansChristiaan Anderson to Daniel Webster—but, alas, none of Thomas Jefferson. Thereare plenty of Jefferson statues throughout the nation, however. Most of themwere commissioned starting early in the twentieth century.

The Memorial

The most monumental Jefferson statue is Rudulf Evans’ towering,19-foot-tall sculpture that is the centerpiece of the Jefferson Memorial inWashington, D.C. Not surprisingly, Jefferson Monroe Levy was an early proponentof a memorial to Jefferson in the nation’s capital.

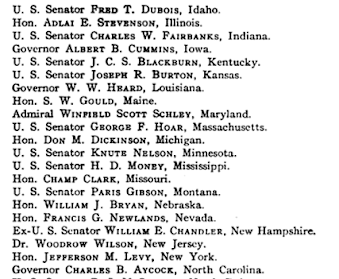

InFebruary 1903—a year after it was decided that the Tidal Basin would be thesite of a future unspecified memorial and two years after Jefferson Levy hadcompleted his first term in the House of Representatives—he was appointed as oneof several dozen vice presidents (see the shortened list above) of the recentlyformed Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States.

That Washington, D.C. group soon began to raise funds and lobbyfor a memorial to the “author of the Declaration of Independence,” as the abovemembership card puts it, to be located in the Nation’s Capital.

Itappears that the TJMAUS ceased functioning in 1907 without making anytraction in its mission. But in 1926, two years after Jefferson Monroe Levy’sdeath, Congress took up the cause and considered a resolution to authorize theerection of a memorial to Thomas Jefferson for the first time.

It took eight years for the idea to gain traction on theHill, but on June 26, 1934, the Senate and House approved a JointResolution establishing the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Commission (TJMC)with a mandate to build a memorial to its namesake at the intersection ofConstitution and Pennsylvania Avenues in downtown D.C. Congress appropriated $3million for construction. The following year, the commission commissioned thearchitect John Russell Pope, who designed the National Archives building fouryears earlier, to draw up the plans for the Jefferson Memorial.

In 1936, President Franklin Roosevelt asked the commission tochose a larger site for the memorial. They decided on the south bank of theTidal Basin and construction began in late 1937

FDR laid the cornerstone twoyears later. Evans received the commission to sculpt the statue in 1941 and thememorial was dedicated before 5,000 spectators—including three dozen Jeffersondescendants—on Thomas Jefferson’s birthday, April 13, during the World War IIyear of 1943.

AsI wrote in Saving Monticello, the Thomas Jefferson MemorialFoundation took a leading role in the movement to build the nationalmemorial to Thomas Jefferson beginning in 1926, when Congress first proposedit. That included Stuart Gibboney, the first head of the Foundation, beingnamed chair of the Memorial Commission in 1938.

Gibboney (1876-1944), a Virginia-born New York City lawyer who specialized inbanking litigation and was a mover and shaker in the national Democratic Party,opened the dedication ceremonies in 1943. Following the invocation by the presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church in America,came the singing of the National Anthem during which the giant statue, whichhad been covered with American flags, was unveiled.

President Roosevelt spoke next in an address that wasbroadcast live on national radio. He called the memorial a “shrine to freedom,”and went on to talk about Jefferson’s challenges and those facing the nationduring the dark days of World War II.

Jefferson, FDR said, “faced the fact that men who willnot fight for liberty can lose it. We, too, have faced that fact. He lived in aworld in which freedom of conscience and freedom of mind were battles still tobe fought through—not principles already accepted of all men. We, too, have livedin such a world. Hebelieved, as we believe, that men are capable of their own government, and thatno king, no tyrant, no dictator can govern for them as well as they can governfor themselves….

“The words which we have chosen for this Memorial speakJefferson’s noblest and most urgent meaning; and we are proud indeed tounderstand it and share it: ‘I have sworn upon the altar of God, eternalhostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.’”

EVENTS: I will be doing more events in 2025, including talks on SavingMonticello, as well as for my new book, The Unlikely War Hero. It’s aslice-of-life biography of the extraordinary Vietnam War story of Doug Hegdahl,the youngest and lowest ranking American prisoner held in Hanoi during the war.More info at https://bit.ly/Hegdahl

The book had a strong start. Not long after The Unlikely War Heroarrived in bookstores and at online booksellers in early December, it becamethe bestselling Vietnam War History book on Amazon

The first printing then sold out within a week. Thesecond printing, on January 17, sold out immediately due to the huge number ofbackorders after the first printing was gone. The third printing is scheduledfor the first week of February. I havesome copies of the first printing. To order a signed copy, go to my website, https://www.marcleepson.com/

If you’d like to arrange a talk on The UnlikelyWar Hero, Saving Monticello, or any of my other books, please emailme at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on upcoming events, check the Eventspage on my website: marcleepson.com/events

COMMERCE: I have brand-new paperback copies of Saving Monticello and a few as-newhardcovers. To order personalized, autographed copies, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrderingor email me directly at marcleepson@gmail.com

I also have copies of Flag: AnAmerican Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Ballad of the Green Beret; and Huntland.

You can read back issues of this newsletter at http://bit.ly/SMOnline

December 19, 2024

December 2024

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest aboutthe book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor- Marc Leepson

VolumeXXI, Number 12 December2024

JANE KAMENSKY: THE INTERVIEW: InOctober last year, nearly 100 years after its founding, the Thomas JeffersonFoundation announced the appointment of Dr. Jane Komensky, as its new president and CEO.

Dr. Kamensky, who officially took over onJanuary 15 this year, is just the second historian to head the Foundation. Thelate Dr. Daniel P. Jordan, Ph.D., who served as the Foundation’s director from1985 until his retirement in 2008 was the first. Dan Jordan came to theMountaintop from Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond where he chairedthe History Department.

Dr. Kamensky took the job at Monticello after a thirty-yearacademic career, most recently at Harvard University where she was a Professorof American History and the Foundation Director of the Arthur and ElizabethSchlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Harvard RadcliffeInstitute.

She has written or co-written seven books of Americanhistory, including A Revolution in Color, the award-winning biography ofthe colonial artist John Singleton Copley, and co-edited The Oxford Handbookof the American Revolution.

I recently spoke to Dr. Kamensky about her first year ashead of the Foundation and her perspective on the Levy Family’s role in savingMonticello. What follows is our conversation, edited for length.

What did you know about the post Jefferson history ofMonticello before you took the job?

I can admit to considerable ignorance about thepost-Jefferson, pre-Foundation history of Monticello before we came here. Afterthe recruitment started, I was informed about the documentary [“The Levys ofMonticello”], which was the way I first learned about the remarkable history ofthe Levy Family preserving this treasure for the nation.

Can you explain how the post-Jefferson history of Monticello—specificallythe Levy Family’s ownership—informs your work as the head of the Foundation?

We always need to be telling the story of what theinvestment is across generations that allows a fragile thing to continue toexist.

I have a friend in the museum world who says the first thingwe should be prompting anybody to ask when they’re looking at a historic objectin a museum or visiting an historic site is: “How is it that this is stillhere?”

That’s because, ultimately, thatis the question that activates the visitor or the viewer. To ask that questionis to enter that work of preservation and transmission—to enter the work ofmaking a building and a landscape like Monticello a kind of living text.

A place that does that really successfully in itsinterpretation is the Museum of the American Revolution [in Philadelphia], whose“wow” object is Washington’s war headquarters, which is a tent. They do awonderful orientation program with his field Oval Office—this fragile canvastent. The sort of meta story—the story that really hits the viewer in the gut—isthat the work of preserving the tent is like the work of preserving andrenewing democracy.

And there’s a parallel with the Levys?

The Levys have done a more herculean thing by preserving animmense, fragile, and demanding site by not tearing it down and re-making it intheir own image, by making a building live values that were vitally importantto Commodore Levy’s ascent through prejudice in the United States.

So, by telling that story, we are inviting our guests—as youhave invited readers of the book and the documentarians have invited viewers ofthe movie—into the work of preserving this fragile fabric of self-government.

How would you characterize what Uriah and Jefferson Levydid at Monticello during the 89 years they owned it?

We have to remember that the common condition for all humanhistory—and it’s written in artifactual records—is loss and destruction. Thedefault is not preservation; the default is loss. Entropy alone—forget aboutJefferson’s debt and the inability of his heirs to reasonably sustain theplantation and house—entropy alone would have destroyed the thing long since.

And it’s remarkable [thatthe Levys stepped] into that role as preservationists and not wildly re-madethe place in their own image. I think that in the preservation community it’s arelatively modern sensibility that says we should start by doing no harm. And Ithink the Levys brought that approach to Monticello.

I’m thinking of a counter example: the former townhouse, now the Old StateHouse in Boston [above], which was nearly destroyed fifty times over. Oneof the first big gestures those who saved it accomplished was to tear out itsguts and put in a grand Victorian staircase. You can certainly imagine aVictorian sensibility, wanting to do that at Monticello in an extremelyinconvenient house in a whole set of ways.

But [the Levys' allegiance to Jeffersonian ideals was such that they lived as lightly in the thing as they could. It's truly remarkable.

So, it’s not only the stepping in to save it, but then theliving with, and in, it in a way that didn’t radically remake it in their own image.

I wrote in Saving Monticello that you can make acase that Uriah Levy was the first American house preservationist. Do you thinkthat’s true?

I think he was early by a generation. [It wasn’t until] aroundthe time of the U.S. Centennial in 1876 when the first major American museums werefounded with period rooms as centerpieces when a kind of preservationist ethicaround the colonial period—even though it was often wrong; they often putthings together that wouldn’t have gone together—begins to have some publictraction.

So, Uriah Levy is early by a long generation from that at atime when the spirit was toward the new. I’m not enough of an architecturalhistorian to say, yes, you’re right, theirs is the first such example, but he’scertainly swimming against the tide in the second and third quarter of the nineteenthcentury.

Anything else about that Levys and Monticello that you’dlike to add?

I’m eager to embrace the spirit of pluralism that broughtthe Levys to save Monticello. I think we need it badly in America in 2024. Ithink Jefferson knew how valuable it was during his lifetime.

And the last thing I’ll offer, sort of invoking your booktitle, is we all need to do the equivalent of saving Monticello every day. [I’m]thinking about ourselves as preservationists, not only of houses andlandscapes, but also of our form of self-government, that allowed Uriah Levyand his descendants to have the trajectory that they did.

THEHARLEY LEWIS PAPERS: Richard Lewis, a great grandnephew of JeffersonLevy, recently emailed to say that the family has donated the papers that hismother, Harley Lewis, had gathered over many years dealing with her great uncleJefferson Levy and other family Monticello matters to the American JewishHistorical Society in New York City.

His mother, Richard Lewis told me, “was the keeper of familypapers handed down to her from her mother, Frances Wolff Levy. When Harleydied in 2020 at the age of 94, we decided to donate all of the papers to the AmericanJewish Historical Society in 2024 where they have now been archived and addedto their collections to preserve them for future generations.”

As the JHS description of the material notes: Harley Lewis (above)—who graciously shared the material with me when I was doing the research for Saving Monticello 25 years ago—“served as the family’s historian and primary connection to Monticello in the mid- to late-20th century, the home of … Thomas Jefferson, and the legacy of Commodore Levy, the first Jewish person to rise to the top of the U.S. Navy and owner of Jefferson’s Monticello purchased in 1834, and held by the family until it was sold to the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation in 1923 by Uriah’s nephew, Congressman Jefferson Monroe Levy (1852-1924).

“The collection contains correspondence, articles, and newsclippings relating to Commodore Levy, and family correspondence, genealogy,photographs, articles, memorabilia, indentures, wills and last testaments, andsome ephemera regarding families related to Uriah Levy in Virginia and New YorkCity.” The book had a strong start. Not long after The Unlikely WarHero arrived in bookstores and at online booksellers early this month, itbecame the bestselling Vietnam War History book on Amazon.com And the firstprinting sold out within a week.

EVENTS: I will be doing more events in 2025,including talks on Saving Monticello, as well as for my new book, TheUnlikely War Hero. It’s a slice-of-life biography of the extraordinaryVietnam War story of Doug Hegdahl, the youngest and lowest ranking Americanprisoner held in Hanoi during the war. More info at https://bit.ly/Hegdahl

If you’d like to arrange a talk on that book, or onSaving Monticello or any of my other books, please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on upcoming events, check the Eventspage on my website: marcleepson.com/events

COMMERCE: I have brand-new paperback copies of Saving Monticello and a few as-newhardcovers. To order personalized, autographed copies, go to https://bit.ly/BookOrderingor email me directly at marcleepson@gmail.com

I also have copies of five of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly WeHailed; Ballad of the Green Beret, and Huntland.

Due to high demand, I’m temporarily out ofcopies of The Unlikely War Hero but will be restocking very soon.