Marc Leepson's Blog, page 5

September 6, 2022

September 2022

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 9 September 2022

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

THE REAL SAMUEL NUNES STORY: In Saving Monticello I told the fascinating story of one of Uriah Levy’s great-great-grandfathers, Samuel Nunes Ribiero, whom I described as “a prominent, well-to-do Portuguese physician,” and went on to say that he and his family were crypto-Jews, sometimes called conversos or marranos (which can be translated as “swine” or “pig”) and by one account made a thriller-worthy escape from the Spanish Inquisition.

Said escape involved a miraculous reprieve from the Grand Inquisitor; a stealth Passover Seder; and a British sea captain masterminding a daring plan for him, his mother, his wife, and their two sons and a daughter under the noses of their Inquisitorial overseers to London in 1726.

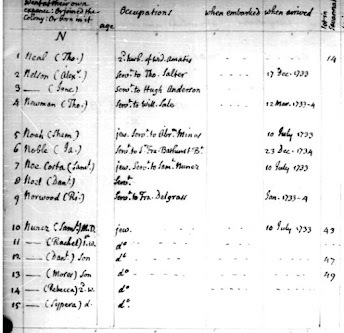

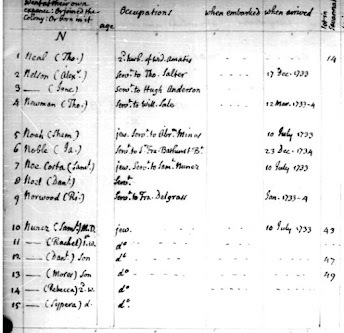

The Nunes family openly practiced Judaism in England. In 1733 they were among 40 Jews who immigrated to the colony of Georgia, where they changed the family name to Nunez, as indicated in the document, Early Settlers of Georgia (1783) below.

“The true story,” Alex Bueno-Edwards—who translated the page into English—wrote, “is less dramatic than the fantastically embellished version found all over the Internet, but much more compelling.”

What follows are facts that I found particularly compelling about the Samuel Nunes family and the Inquisition from Correia’s research—facts that I didn’t know when I was doing the research for Saving Monticello. That includes information about Dr. Nunes and his wife Gracia’s—and Uriah and Jefferson Levy’s—Portuguese ancestors.

First, a bit of genealogy:

· Samuel Nunes’ father, Manuel Henriques de Lucena, was born about 1641 in São Vicente da Beira, about a 150 miles northeast of Lisbon. A customs officer, he moved to Lisbon in 1703.

· Sometime around 1668 Manuel had married Samuel Nunes’ mother, Maria Nunes Ribeiro, who was born circa 1653, most likely in Idanha-a-Nova not far from São Vicente da Beira, close to the border with Spain.

· Samuel Nunes’ paternal grandparents were Diogo Gomes Henriquesand Isabel Henriques.

· His maternal grandparents were Luis Lopes and Maria Riberio.

· Samuel Nunes married Gracia Caetana da Veiga, born in 1676 in Lisbon.

· Gracia (later known as Rebecca) was the daughter of André de Sequeira, who was born about 1646 in Lisbon, a merchant and businessman.

· Gracia’s mother was Maria Isabel da Veiga, born in Lisbon sometime before 1676.

The Inquisition records show that Dr. Samuel Nunes was Jewish, but was baptized a Roman Catholic to hide that fact. He had established himself in Lisbon by the turn of the 18th century, a particularly violent time of the Inquisition. After being denounced by about a dozen people, Dr. Nunes and his wife Gracia were arrested on August 23, 1703, along with his father Manuel. They were locked up in the prison at the Estaus Palace, the Portuguese Inquisition headquarters.

As for the testimony of their accusers, Arlindo Correia wrote: “As usual, the content of the complaints is repeated, with… variations and additions, following the established formulas: between [Catholic] practices, they declared themselves to be [observers] of the law of Moses for the salvation of their souls.”

Dr. Nunes testified that his wife was “a New Christian,” and that he was baptized, confirmed, learned catechism, and attended “the sacraments and Sunday Mass.” An Inquisitor challenged him, urging him to confess his guilt. He replied that he always “acted like a good Catholic,” and that he “never had any practice of Judaism or Jewish ceremony.”

The trial dragged on into the next year. On July 24, 1704, Dr. Nunes decided to “confess” in order to avoid being executed. In a long statement, he denounced “his father, his friends and acquaintances, coinciding greatly with the names of those who had denounced him.”

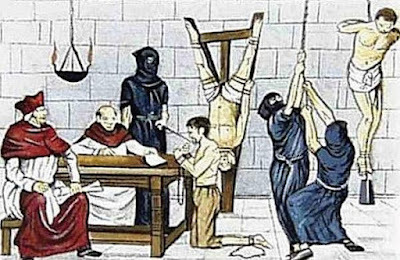

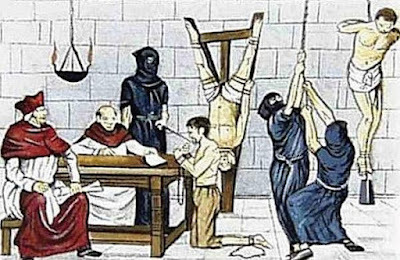

The Inquisitors accepted his confession on August 18, but because he didn’t denounce his wife—and perhaps because some of them were his patients—they spared his life. However, Dr. Nunes was tortured, according to the Inquisition records, for the crime of “not having mentioned his participation in any Jewish ceremony.” He underwent what Correia called “a Hurried treatment.” which “was longer and therefore more painful than the expert treatment.”

No need to go into the gruesome types of torture the Inquisitors subjected Jews and Muslims to. However, the records show that “strings”—most likely ropes—were involved and that the torture was so painful that Dr. Nunes made more confessions, even though he was unable to sign them.

When the torture ended, he was tossed back into the Inquisition prison. Meanwhile, “all of his goods” were confiscated.

Samuel Nunes was not released until May 14, 1706, although his wife Rebecca remained in prison because she refused to confess or give testimony against other family members. She was then tortured more severely than her husband was and eventually denounced several of her relatives. She was released on September 12, 1706. Twenty years later Dr. and Mrs. Nunes and their six children followed the path of other crypto-Jews in Portugal and escaped Lisbon and headed to London.

Next month we’ll pick up the story of what happened to the family in England, leading to their second adventure, the trip across the Atlantic Ocean to Georgia in 1733.

ELI EVANS, 1936-2022: Eli Evans, best known for his pioneering, best-selling book, The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South, died July 26 in New York City of complications from COVID-19. He was 85. Published in 1971, The Provincials is widely regarded as the seminal history of Jews in the American South.

The book “explores the nuances of Southern Jewish identity,” New York Jewish Week said, “and belongs on bookshelves next to Irving Howe’s classic World of Our Fathers,” the famed 1976 history of Eastern European Jews who emigrated to the United States in the late 1890s and early 1900.

Eli Evans was born and grew up in North Carolina where his paternal grandfather had settled after fleeing Lithuania in the late 1800s. His father, Emmanuel “Mutt” Evans, was born in Fayetteville, owned a chain of general stores, and was the first Jewish mayor of Durham. His grandmother, Jennie Nachamson, founded the first Hadassah chapter in the South.

Eli Evans graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1958, where he became the first Jewish student body president and spent a summer on a Kibbutz in Israel. He then served for two years in the U.S. Navy, after which he went to Yale Law School, getting his law degree in 1963.

Eli Evans graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1958, where he became the first Jewish student body president and spent a summer on a Kibbutz in Israel. He then served for two years in the U.S. Navy, after which he went to Yale Law School, getting his law degree in 1963.He moved to Washington, and worked as a speechwriter for President Lyndon Johnson, then for North Carolina Gov. Terry Sanford before relocating to New York City. He was working for the Carnegie Corporation when he wrote The Provincials. Evans went on to become the president of the Charles H. Revson Foundation, and later a founder of the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies at the University of North Carolina.

“I am one of those people who, when they read The Provincials, they felt for the first time a recognition,” Marcie Cohen Ferris, a UNC professor of American Studies who grew up in Arkansas, told The New York Times. “They had never seen their experience of Jewish life reflected this way.”

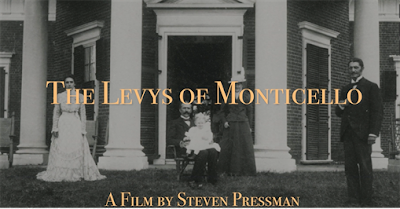

THE DOC: Steven Pressman’s great doc, The Levys of Monticello, is being screened at a bunch of film festivals this fall. It’ll be shown in September in five cities, either virtually or in-person: Cleveland, Chattanooga, Milwaukee, Dallas, and Charleston, S.C.

On October 10, it’ll be at the Jacob Burns Film Center as part of the Westchester Jewish Film Festival. There’s an in-person screen on Sunday, November 6, at the Virginia Film Festival in Charlottesville, after which I’ll be taking part in a Q&A with Steve and others in the film. The next screening is set for November 13 at the Philadelphia Jewish Film Festival in partnership with Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History.

For more info, go to https://bit.ly/LevyDoc

EVENTS:I’ll be taking part in a Book Fair on Saturday, September 17, at Lansdowne Woods in Leesburg, Virginia. Along with a group of other local authors, I’ll be signing copies of my books, including Saving Monticello, beginning at 10:00 a.m. in the spacious Lansdowne Clubhouse Auditorium. Then I’ll be part of a two-person panel, “How to Get Your Book Published,” at 3:00. The event is free and open to the public. The address is 19375 Magnolia Grove Square, Leesburg, VA 20176.

On Tuesday, September 27, I’ll be doing talk on Saving Monticello and a book signing at the monthly meeting of the George Mason DAR Chapter in Springfield, Virginia.

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello or for any of my other books, email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello or for any of my other books, email me at marcleepson@gmail.com For details on other upcoming events, check the Events page on my website https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: For a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello, please e-mail marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

September 2002

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 9 September 2022

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

THE REAL SAMUEL NUNES STORY: In Saving Monticello I told the fascinating story of one of Uriah Levy’s great-great-grandfathers, Samuel Nunes Ribiero, whom I described as “a prominent, well-to-do Portuguese physician,” and went on to say that he and his family were crypto-Jews, sometimes called conversos or marranos (which can be translated as “swine” or “pig”) and by one account made a thriller-worthy escape from the Spanish Inquisition.

Said escape involved a miraculous reprieve from the Grand Inquisitor; a stealth Passover Seder; and a British sea captain masterminding a daring plan for him, his mother, his wife, and their two sons and a daughter under the noses of their Inquisitorial overseers to London in 1726.

The Nunes family openly practiced Judaism in England. In 1733 they were among 40 Jews who immigrated to the colony of Georgia, where they changed the family name to Nunez, as indicated in the document, Early Settlers of Georgia (1783) below.

“The true story,” Alex Bueno-Edwards—who translated the page into English—wrote, “is less dramatic than the fantastically embellished version found all over the Internet, but much more compelling.”

What follows are facts that I found particularly compelling about the Samuel Nunes family and the Inquisition from Correia’s research—facts that I didn’t know when I was doing the research for Saving Monticello. That includes information about Dr. Nunes and his wife Gracia’s—and Uriah and Jefferson Levy’s—Portuguese ancestors.

First, a bit of genealogy:

· Samuel Nunes’ father, Manuel Henriques de Lucena, was born about 1641 in São Vicente da Beira, about a 150 miles northeast of Lisbon. A customs officer, he moved to Lisbon in 1703.

· Sometime around 1668 Manuel had married Samuel Nunes’ mother, Maria Nunes Ribeiro, who was born circa 1653, most likely in Idanha-a-Nova not far from São Vicente da Beira, close to the border with Spain.

· Samuel Nunes’ paternal grandparents were Diogo Gomes Henriquesand Isabel Henriques.

· His maternal grandparents were Luis Lopes and Maria Riberio.

· Samuel Nunes married Gracia Caetana da Veiga, born in 1676 in Lisbon.

· Gracia (later known as Rebecca) was the daughter of André de Sequeira, who was born about 1646 in Lisbon, a merchant and businessman.

· Gracia’s mother was Maria Isabel da Veiga, born in Lisbon sometime before 1676.

The Inquisition records show that Dr. Samuel Nunes was Jewish, but was baptized a Roman Catholic to hide that fact. He had established himself in Lisbon by the turn of the 18th century, a particularly violent time of the Inquisition. After being denounced by about a dozen people, Dr. Nunes and his wife Gracia were arrested on August 23, 1703, along with his father Manuel. They were locked up in the prison at the Estaus Palace, the Portuguese Inquisition headquarters.

As for the testimony of their accusers, Arlindo Correia wrote: “As usual, the content of the complaints is repeated, with… variations and additions, following the established formulas: between [Catholic] practices, they declared themselves to be [observers] of the law of Moses for the salvation of their souls.”

Dr. Nunes testified that his wife was “a New Christian,” and that he was baptized, confirmed, learned catechism, and attended “the sacraments and Sunday Mass.” An Inquisitor challenged him, urging him to confess his guilt. He replied that he always “acted like a good Catholic,” and that he “never had any practice of Judaism or Jewish ceremony.”

The trial dragged on into the next year. On July 24, 1704, Dr. Nunes decided to “confess” in order to avoid being executed. In a long statement, he denounced “his father, his friends and acquaintances, coinciding greatly with the names of those who had denounced him.”

The Inquisitors accepted his confession on August 18, but because he didn’t denounce his wife—and perhaps because some of them were his patients—they spared his life. However, Dr. Nunes was tortured, according to the Inquisition records, for the crime of “not having mentioned his participation in any Jewish ceremony.” He underwent what Correia called “a Hurried treatment.” which “was longer and therefore more painful than the expert treatment.”

No need to go into the gruesome types of torture the Inquisitors subjected Jews and Muslims to. However, the records show that “strings”—most likely ropes—were involved and that the torture was so painful that Dr. Nunes made more confessions, even though he was unable to sign them.

When the torture ended, he was tossed back into the Inquisition prison. Meanwhile, “all of his goods” were confiscated.

Samuel Nunes was not released until May 14, 1706, although his wife Rebecca remained in prison because she refused to confess or give testimony against other family members. She was then tortured more severely than her husband was and eventually denounced several of her relatives. She was released on September 12, 1706. Twenty years later Dr. and Mrs. Nunes and their six children followed the path of other crypto-Jews in Portugal and escaped Lisbon and headed to London.

Next month we’ll pick up the story of what happened to the family in England, leading to their second adventure, the trip across the Atlantic Ocean to Georgia in 1733.

ELI EVANS, 1936-2022: Eli Evans, best known for his pioneering, best-selling book, The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South, died July 26 in New York City of complications from COVID-19. He was 85. Published in 1971, The Provincials is widely regarded as the seminal history of Jews in the American South.

The book “explores the nuances of Southern Jewish identity,” New York Jewish Week said, “and belongs on bookshelves next to Irving Howe’s classic World of Our Fathers,” the famed 1976 history of Eastern European Jews who emigrated to the United States in the late 1890s and early 1900.

Eli Evans was born and grew up in North Carolina where his paternal grandfather had settled after fleeing Lithuania in the late 1800s. His father, Emmanuel “Mutt” Evans, was born in Fayetteville, owned a chain of general stores, and was the first Jewish mayor of Durham. His grandmother, Jennie Nachamson, founded the first Hadassah chapter in the South.

Eli Evans graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1958, where he became the first Jewish student body president and spent a summer on a Kibbutz in Israel. He then served for two years in the U.S. Navy, after which he went to Yale Law School, getting his law degree in 1963.

Eli Evans graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1958, where he became the first Jewish student body president and spent a summer on a Kibbutz in Israel. He then served for two years in the U.S. Navy, after which he went to Yale Law School, getting his law degree in 1963.He moved to Washington, and worked as a speechwriter for President Lyndon Johnson, then for North Carolina Gov. Terry Sanford before relocating to New York City. He was working for the Carnegie Corporation when he wrote The Provincials. Evans went on to become the president of the Charles H. Revson Foundation, and later a founder of the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies at the University of North Carolina.

“I am one of those people who, when they read The Provincials, they felt for the first time a recognition,” Marcie Cohen Ferris, a UNC professor of American Studies who grew up in Arkansas, told The New York Times. “They had never seen their experience of Jewish life reflected this way.”

THE DOC: Steven Pressman’s great doc, The Levys of Monticello, is being screened at a bunch of film festivals this fall. It’ll be shown in September in five cities, either virtually or in-person: Cleveland, Chattanooga, Milwaukee, Dallas, and Charleston, S.C.

On October 10, it’ll be at the Jacob Burns Film Center as part of the Westchester Jewish Film Festival. There’s an in-person screen on Sunday, November 6, at the Virginia Film Festival in Charlottesville, after which I’ll be taking part in a Q&A with Steve and others in the film. The next screening is set for November 13 at the Philadelphia Jewish Film Festival in partnership with Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History.

For more info, go to https://bit.ly/LevyDoc

EVENTS:I’ll be taking part in a Book Fair on Saturday, September 17, at Lansdowne Woods in Leesburg, Virginia. Along with a group of other local authors, I’ll be signing copies of my books, including Saving Monticello, beginning at 10:00 a.m. in the spacious Lansdowne Clubhouse Auditorium. Then I’ll be part of a two-person panel, “How to Get Your Book Published,” at 3:00. The event is free and open to the public. The address is 19375 Magnolia Grove Square, Leesburg, VA 20176.

On Tuesday, September 27, I’ll be doing talk on Saving Monticello and a book signing at the monthly meeting of the George Mason DAR Chapter in Springfield, Virginia.

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello or for any of my other books, email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello or for any of my other books, email me at marcleepson@gmail.com For details on other upcoming events, check the Events page on my website https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: For a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello, please e-mail marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

August 4, 2022

August 2022

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 8 August 2022

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

THE RACHEL PHILLIPS WEDDING: When Uriah Levy bought Monticello from James Turner Barclay in 1836, he never planned to live there permanently. An active duty U.S. Navy Lieutenant, Levy lived in a well-appointed townhouse in New York City when he wasn’t sailing the seas. One member of the Levy family, his mother Rachel, did to take up residence in Monticello the year after Uriah Levy’s purchase.

Rachel Machado Phillips Levy (below) was born in New York City in 1769, the daughter of Jonas Phillips (1736-1803) and Rebecca Machado Philips (1746-1831). Jonas and Rebecca Phillips, astoundingly, had 21 children. Several died as infants, including Rachel’s twin sister, Sarah.

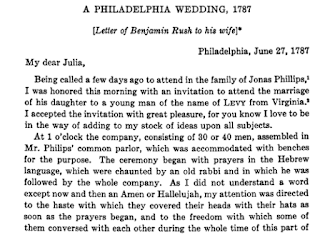

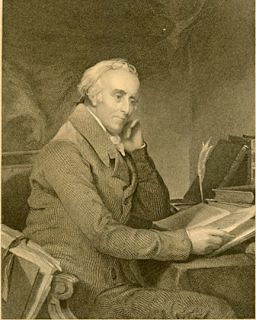

Rachel married a young immigrant from Germany, Michael Levy, in Philadelphia in 1787 when she was 18 years old. A description of their wedding—believed to be the first recorded of a Jewish wedding ceremony in the New World—is contained in a letter written on the day of the wedding, June 27, by the famed Revolutionary War patriot and physician Dr. Benjamin Rush (1745-1813) to his wife Julia.

In it, Dr. Rush—a signer of the Declaration of Independence—provided plenty of details about the wedding that ring true, although he mistakenly wrote that Michael Levy was from Virginia. After that faux pas, Rush went on to describe the ceremony. He told his wife that it began with about twenty minutes of prayer in “the Hebrew language,” after which Michael Levy signed the Ketubah, a Jewish marriage contract.

Rush described it as “a small piece of parchment… written in Hebrew, which contained a deed of settlement and which the groom [signed] in the presence of four witnesses. In this deed he conveyed a part of his fortune to his bride, by which she was provided for after his death in case she survived him.”

Next, the Chuppah—the structure under which a Jewish bride and groom take their vows—was put in place. Rush described it as “a beautiful canopy composed of white and red silk in the middle of the floor. It was supported by four young men (by means of four poles), who put on white gloves for the purpose.”

After the Chuppah was ready, the bride, accompanied by “her mother, sister, and a long train of female relations, came downstairs.” Rachel Phillips’ face, Rush wrote, “was covered with a veil which reached halfways down her body.”

Describing the bride as “lovely and affecting,” Rush said he “gazed with delight upon her. Innocence, modesty, fear, respect, and devotion appeared all at once in her countenance.”

The rabbi (Rush called him “the priest”) then led the assembled in prayer in Hebrew, after which the bride and groom sipped from “a glass full” of wine. After that, the rabbi “took a ring and directed the groom to place it upon the finger of his bride in the same manner as is [practiced} in the marriage service of the Church of England.”

The rabbi (Rush called him “the priest”) then led the assembled in prayer in Hebrew, after which the bride and groom sipped from “a glass full” of wine. After that, the rabbi “took a ring and directed the groom to place it upon the finger of his bride in the same manner as is [practiced} in the marriage service of the Church of England.” Then came more ceremonial wine sipping by the father of the bride, Jonas Phillips, and the bride and groom. After Michael Levy drank his wine, he “took the glass in his hand and threw it upon a large pewter dish which was suddenly placed at his feet. Upon its breaking into a number of small pieces, there was a general shout of joy and a declaration that the ceremony was over. The groom now saluted his bride, and kisses and congratulations became general through the room.”

Rush (below) stuck around after the ceremony to have a slice of wedding cake and a glass of wine. Then he paid his respects to Rebecca Philips, who had fainted “under the pressure of the heat.”

He was about to take his leave when Rebecca Phillips put “a large piece of cake” into his pocket to give to his wife.

Michael Levy and Rachel Phillips Levy had four children in the next five years. (They eventually had fourteen, three girls and eleven boys.). The fourth child, Uriah Phillips Levy, was born in Philadelphia on April 22, 1792.

Flash forward 45 years to 1837, when the then U.S. Navy Lt. Uriah Levy brought his 68-year-old mother with him to Monticello, where she took up residence in the house. Rachel Phillips Levy lived in Thomas Jefferson’s “Essay in Architecture” for two years until she died on May 1, 1839. Her son was at sea at the time, commanding the U.S.S. Vandalia, a 783-ton sloop of war. He apparently did not learn that his mother had died until six months later when he arrived at Monticello after the Vandalia's cruise ended and the ship put in at Norfolk.

Back on the mountaintop in early May the manager of Monticello, Joel Wheeler, had contacted Uriah’s siblings, Jonas and Amelia, and they arranged to have their mother buried near the house. The tombstone (below) Levy later erected included the Hebrew month and year of his mother’s death. It was inscribed:

“To the memory of Rachel Phillips Levy, Born in New York, 23 of May 1769, Married 1787. Died 7, of IYAR, (May) 5591, AB (1839) at Monticello, Va.”

She is the only Levy family member buried at Monticello.

THE DOC: By mid-summer, Steven Pressman reports, his terrific documentary The Levys of Monticello had been shown “at nearly 20 festivals around the country and in Canada, with more than a dozen others on the schedule for later this summer and fall—and many more to come beyond that.”

In answer to an oft-asked question about when the film will be available online, he said: “That will happen at some point in the future, but for now the film will continue to be shown on the festival circuit throughout the rest of the year and into 2023. So for those who haven’t yet had a chance to see the film, hopefully it’ll be coming your way soon.” You can find more info about this award-winning documentary, including the trailer, at https://bit.ly/LevyDoc

EVENTS:I’ll be doing two Zoom talks for Context Conversations this month. The first, on Saving Monticello, complete with scores of historical images, takes place on Monday, August 15, beginning at 5:00 p.m. Eastern time.

The second is on the July 9, 1864, Civil War Battle of Monocacy and Confederate Gen. Jubal Early’s subsequent attack on Washington, D.C., based on my book Desperate Engagement. It’s on Monday, August 22, also at 5:00 p.m. Eastern. For info and tickets, go to https://bit.ly/MonticelloContextor https://bit.ly/ContextDesperate

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello or for any of my other books, email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on other upcoming events, check the Events page on my website: https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: For a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello, please e-mail marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

The SM Newsletter on Line: You can read back issues of this newsletter at http://bit.ly/SMOnline

July 6, 2022

July 2022

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 7 July 2022

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

JEFFERSON LEVY’S 4th: Jefferson Levy, who lived in New York City during the years he owned Monticello (1879-1923), visited the house irregularly during the year. He made it a point, though, to spend Fourth of July at Thomas Jefferson’s house. And when he did, the always-social New Yorker hosted Independence Day ceremonies on the mountaintop.

Levy invited his staff at Monticello and guests from Charlottesville to take part in the festivities. After 1889, Levy’s on-site Monticello superintendent Frederick Rhodes built catapults and scaffolds for displays of fireworks. Often, a band came from Charlottesvilleto play patriotic tunes.

Jefferson Levy would end the evening by reading the Declaration of Independence from Thomas Jefferson’s music stand in front of the guests assembled on Monticello’s West Lawn.

The Independence Day tradition continues to this day at Monticello. It’s perhaps most famous for the swearing-in ceremony for new U.S. citizens that was added to the event in 1963. That’s President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the photo speaking at Monticello on July 4, 1936.

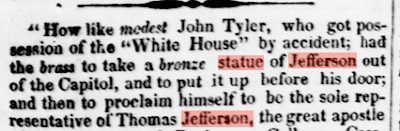

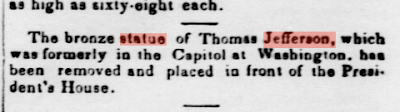

STATUE CORRECTION: A few weeks ago I came across new information about the larger-than-life, full-length statute of Thomas Jefferson that Uriah Levy commissioned in Paris from the noted French sculptor David d’Angers in 1833, and donated to the people of the United States—the one that’s displayed today in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda in the nation’s capital.

In sketching the history of the statue’s journey from France to Washington, D.C., in Saving Monticello, I wrote that following Uriah Levy’s donation, U.S. House and Senate resolutions called for the statue to be displayed outside the Capitol’s East front (facing the Mall), but for “reasons that are unclear,” it was placed inside the Capitol, in the Rotunda.

On February 16, 1835, a resolution was introduced in the House to remove the statue from the Rotunda “to some suitable place for its preservation, until the final disposition of it be determined by Congress.” After some debate, during which one member said that Congress should accept statuary only from “distinguished” sources, debate was cut off and no action was taken.

“Sometime during the James K. Polk administration (1845-49),” I wrote, noting also that “the exact date is not certain,” the statue left the Rotunda, and was shipped up Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House. There, with the permission of President Polk, David’s bronze Jefferson was placed on the grounds on the north side facing Lafayette Park.” That’s the statue in a photo above taken in the 1860s.

I wrote, “not certain” because the only source I found that provided a date was a statement from Uriah Levy’s brother Jonas (Jefferson M. Levy’s father), in 1874 when he led an effort to get the rusting statue off the White House lawn and back to the Capitol.

Turns out that Rosie Cain, a graduate fellow at the White House Historical Association, was digging through digitized old newspapers and came across a handful of articles and editorials that prove that the statue was moved to the White House North Lawn in April 1843. Which means that it the statue moved during the John Tyler Administration—not two years later under Tyler’s successor, James Polk, as I reported in the book.

I did a quick search on the Library of Congress’ invaluable Chronicling America page—which contains hundreds of thousands of searchable newspaper articles from 1777 to 1963—and found a half dozen articles and editorials documenting that the statue did, indeed, move in the spring of 1843.

Here are two examples: an editorial from May 24, 1843, Alexandria (Va.) Gazette, and a May 6, 1843, blurb from the Richmond, Indiana, Palladium that also appeared in a few other newspapers around the country.

EVENTS: Just one appearance on tap for this month: On Sunday, July 16, I will be taking part in Fort Stevens, the annual Fort Stevens Commemoration event Washington, D.C., which goes from 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m.

I’ll be doing a book signing and a brief talk at 11:30 on my book, Desperate Engagement, the story of the July 1864 Civil War Battle of Monocacy and Confederate Gen. Jubal Early’s subsequent attack on Washington, D.C., which centered on two days of fighting at Fort Stevens.

The event is free and open to the public at 6001 13th St. NW. It’s is sponsored by the Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington.

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello or for any of my other books, email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on other upcoming events, check the Events page on my website: https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

June 8, 2022

June 2022

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 6 June 2022

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

THE LIBRARY: Thursday, May 26, 2022, was a memorable day in my professional life: the day that I turned over my Saving Monticello research materials to the Jefferson Library at Monticello. I had been thinking about the best place to archive those thousands of pages of transcribed interviews, photocopied newspaper and magazine articles, letters, documents, books, and many other primary and secondary sources that I had accumulated since 1997 when I first began researching the story of the Levy family and Monticello.

The longer I thought about it, the more I realized that the Jefferson Library would be the perfect place for future scholars and anyone else interested in the post-Jefferson history of Monticello.

With Endrina Tay, the Fiske and Marie Kimball Librarian,

at Monticello's Jefferson Library. Photo by Ian Atkins,

Courtesy of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello

Once this small mountain (pun intended) of material is catalogued and archived, anyone with an Internet connection will have access to a large amount of the collection that deals with the Levy family and with virtually every other aspect of what happened on the mountaintop after July 4, 1826.

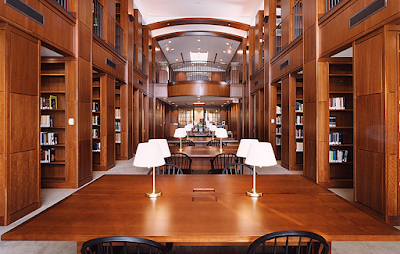

The 15,500-foot, state-of-the-art Jefferson Library at Monticello was dedicated on April 13, 2002, Thomas Jefferson’s birthday—just six months after the publication of Saving Monticello. The beautiful building is adjacent to Monticello on the former Kenwood plantation, which was once owned by Thomas Jefferson.

Before the library opened as part of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies (ICJS), the Thomas Jefferson Foundation had housed its research materials in several small library collections at Monticello and in other office space nearby.

In the early 1990s then-Foundation President Daniel P. Jordan led the effort to build a central research library on the mountaintop. The Foundation, working with the University of Virginia, leased the 78-acre Kenwood property, plans were drawn up, and construction began on September 15, 2000. Since opening two years later the Library and the ICJS have hosted hundreds of scholars, teachers, and students. The building houses books, journal and newspaper articles, ephemera, unpublished research, websites, microforms, audio-visuals, photographs, and digital full-text files.

The material, naturally, focuses on Thomas Jefferson and Monticello, but the library also contains materials on the colonial, Revolutionary War, and Early Republic periods, as well as religion and philosophy and European arts and culture. ICJS, of which the library is an integral part, holds international scholarly conferences, panel discussions, teacher workshops, lectures, and curriculum-based tours.

“Opening this magnificent new library in Jefferson’s name, we again unfurl the glorious banners of liberal education, the open mind, the pursuit of truth, freedom of religion, the free and open exchange of ideas, the love of learning,” the eminent historian David McCullough said in his remarks at the library’s dedication.

The Library's Robert H. and Clarice Smith Reading Room

Hartman-Cox Architects photo

The Jefferson Library, under the leadership Endrina Tay, who succeeded Jack Robertson as the Fiske and Marie Kimball Librarian in October 2021, is open to public researchers by appointment only. To make the arrangements, go to https://bit.ly/LibAppointment

In this, the Jefferson Library’s twentieth year, the library features a commemorative exhibit, “The Jefferson Library: Two Decades of Scholarship and Community,” in the lobby. The exhibit is open to the public, as is its online component at https://bit.ly/AnnivExhibit You can learn more about the library at https://bit.ly/JLibraryand search through the collections at https://bit.ly/JLibrarySearch

In the very near future those collections will contain all of the research materials (much of it digitized) that I have gathered in the 25 years since I began researching at the old Monticello Research Department.

I’m extremely grateful to everyone at Monticello—especially Endrina Tay and Susan Stein, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation’s Richard Gilder Senior Curator, Special Projects—for allowing me the privilege of donating my work to the Library’s collections.

DAVID AND JEFFERSON: In 1833, as I wrote in Saving Monticello (and several times in this newsletter), Uriah Levy commissioned the renowned French sculptor Pierre-Jean David d’Anger to create a full-length statue of Thomas Jefferson, which now sits in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. David also created a bronze medallion of Uriah Levy at the same time, a piece of art that now housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

In 1840, David created another, very different kind of work that included a sculpted image of Thomas Jefferson. Here’s a first-hand report about it from my friend and colleague, Steven Pressman, (the director of “The Levys of Monticello” documentary) who came across it during a recent trip to France:

What do Uriah Phillips Levy, Johannes Gutenberg, Thomas Jefferson and the city of Strasbourg, all have in common?

It turns out that the same French sculptor, David d’Angers, who was commissioned by Levy in the early 1830s to create a bronze sculpture of Jefferson, also included Jefferson as part of a dramatic monument that he made in honor of Gutenberg, the German inventor of the printing press.

The Gutenberg monument, created by d'Angers in 1840, is located in Strasbourg, where Gutenberg lived for several years and where he worked on his new printing invention in the 1440s. Jefferson appears in one of the four bronze relief panels at the base of the Gutenberg statue, each of which commemorates historic uses of a printing press.

The panel that depicts Jefferson celebrates the printing of the Declaration of Independence and includes several other signers of the document, along with other figures such as George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette and Simon Bolivar, who helped several countries in South America gain their independence from Spain.

‘THE LEVYS OF’ DOC: Speaking of “The Levys of Monticello,” Pressman’s terrific documentary that tells the post-Jefferson history of Monticello, it continues to make the film festival rounds and garner accolades. The doc’s most-recent honor came last month when it received the Audience Award for Best Documentary at the Washington, D.C. Jewish Community Center’s JxJ 2002 film festival. Because of that the festival announced that they will have a third in-person screening of the film on July 21. Ticket info at https://bit.ly/July21Screening

The next screenings will be online as part of this year’s 2022 Ann Arbor Jewish Film Festival, starting on July 3. As per the usual film festival rules, you can register for the festival’s online screenings only if you are a Michigan resident. More info at https://bit.ly/AnnArborFilmFest

EVENTS: Two talks on my book, Flag: An American Biography coming up this month; the first on Saturday, June 11, will be a Zoom talk for the California Association of the Society of the Cincinnati; the second, on Flag Day, Tuesday, June 14, will be at the Glebe retirement community in Daleville, Virginia.

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello or for any of my other books, email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on other upcoming events, check the Events page on my website: https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

May 4, 2022

May 2022

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 5 May 2022

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

A LARGER HOUSE: As I noted in Saving Monticello, and in just about every talk I have done in the last two decades about the book, historic preservationists have long praised Uriah and Jefferson Levy for only making minimal changes to the house and grounds during their 89-year ownership. That fact—and that the Levys themselves repaired and preserved the house—made it infinitely easier for the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation to restore the house and grounds when they purchased it from Jefferson Levy in 1923.

Most importantly for preservationists, unlike the subsequent owners of Montpelier, James Madison’s plantation not far from Monticello, the Levys never added onto the house. Nor did they knock down any walls. Jefferson Levy replaced Thomas Jefferson’s roof, modernized the plumbing, and added electricity and dormer windows during his 1879-1923 ownership. But that was extent of the physical changes when the Levys owned the house.

The one fly in the preservation ointment came in 1895 after Jefferson Levy had owned Monticello for 16 years and had poured tens of thousands of dollars into repairing, restoring, and furnishing the house. It came about after the October 27, 1895, fire at the University of Virginia that destroyed the Thomas Jefferson-designed Rotunda (below) overlooking the University’s Lawn.

U-Va. hired McKim, Mead and White, one of the nation’s top architectural firms, to rebuild the Rotunda. Stanford White (1853-1906) himself—the famed designer of the old Madison Square Garden who was considered the premier American architect of his day—took charge of the project.

The process took more than three years. While White was in Charlottesville working on the Rotunda restoration, “he was approached by Mr. [Jefferson] Levy,” according to William M. Thornton, then the dean of the U-Va. Engineering Department. “Mr. Levy told him that he wanted, very often, to entertain a number of guests at Monticello. It has thirty-odd rooms, but, still he needed more rooms. Now, he said, ‘I want you gentlemen to take up the question of adding to Monticello.’”

White responded by sending one of his firm’s New York architects to the mountaintop to have a “careful survey made” of Monticello. After going over the results of the study, White declined to do the enlargement.

This is what Stanford White wrote to Jefferson Levy about his decision:

“We have looked into your proposal to add to Monticello and we beg to report to you that we must decline the engagement. We think that no architect could add to Monticello without spoiling it. If you want a larger house, we would be very glad to build you a larger house, but we must decline to add to Monticello.”

It appears that Jefferson Levy learned a lesson. There is no evidence that during the remaining 26 years of his ownership of Monticello that he entertained any ideas of expanding or otherwise altering Thomas Jefferson’s “Essay in Architecture.” More importantly, the highly successful lawyer and stock speculator continued to spend large sums of money, repairing, maintaining and preserving Monticello.

THE LEVYS DOC: “The Levys of Monticello,” my friend and colleague Steven Pressman’s terrific documentary that tells the post-Jefferson history of Monticello, continues to make the film festival rounds. There will be two in-person screenings at the Washington Jewish Film Festival, including post-screening discussions and Q&As on Sunday, May 15, in Bethesda, Md., and on Tuesday, May 17, in D.C. Details and tickets at https://bit.ly/DCFilmFesti

The doc was screened at the Aaron Family JCC in Dallas’ Zale Auditorium as part of that city’s Jewish Film festival on May 2; and two screenings were held in late April at the River Run International Film Festival in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Steve, by the way, just launched a new website with info on all of his films. Take a look at https://bit.ly/SteveWebSite

EVENTS: I’ll be doing a talk on the Civil War Battle of Monocacy and the subsequent Confederate attack on Washington, D.C.—the subject of my book, Desperate Engagement—on Thursday, May 19, for the The Association of the Oldest Inhabitants of the District of Columbia in Washington, D.C.

On Tuesday, May 24, I’ll be in Locust Grove, Virginia, to do a talk on Saving Monticello for the Wilderness ‘Tiques Questers group. On Thursday, May 26, I’ll be speaking about the book to the Farmington Historical Society in Charlottesville.

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello or for any of my other books, email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on other upcoming events, check the Events page on my website: https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

April 5, 2022

April 2022

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 4 April 1, 2022

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

MARTHA WOODWARD: One day last month as I was scrolling through Instagram, I saw before-and-after images of a drawing of the East Front of Monticello dating from the mid-1830s that the terrific Curatorial, Collections, and Restoration team at the Thomas Jefferson Foundation had recently restored.

The drawing, the post noted, “was in ROUGH shape when we first acquired it” in 2016. “The varnish had discolored, it was extremely brittle, and there were numerous tears,” some of which “were repaired with tape, which had yellowed and deteriorated over time.” The Foundation brought in an expert art conservator who spent “many hours cleaning, mending, and flattening,” the drawing, and as you can see from the before-and-after photos below, it “was brought back to life—all thanks to the amazing work of our conservators."

Aside from the great restoration and conservation work, several other things drew me to this story: The fact that I’d never seen this photo before, as images of Monticello in the 1830s are extremely rare; that’d I’d not heard of the artist, Martha Woodward; and—most significantly—that it likely was drawn in 1834.

What’s significant about 1834? Only the fact that that was the year that Uriah Levy purchased Monticello from James T. Barclay, and solid historical evidence has convinced me and every other historian who’s studied the history of Monticello that the house was in terrible condition in 1834. As I noted in Saving Monticello, a visitor at the time wrote that “all was in dilapidation and ruin.” The Woodward drawing painted a very different picture and I wanted to see if the date was correct and, if so, if it could be determined that she was romanticizing what she saw to present a pristine image of the house and grounds.

After doing an online search, I came up blank, so I emailed Emilie Johnson, Monticello’s Associate Curator, who has a wide knowledge of the provenance and other historical matters relating to the artwork at Monticello. Emilie, like everyone else at the Foundation, has been extremely supportive of my work and I was pleased that she filled me in on Martha Woodward and the drawing.

She told me that not much is known about Martha Woodward, other than the fact that she, indeed, was an artist, and that she and her sister Maria were close friends of Thomas Jefferson’s granddaughters, particularly Ellen Randolph Coolidge. Martha and Maria Woodward, Emilie said, “were part of an extended Randolph cousin circle that the Randolph granddaughters (in particular) socialized with in the 1810s and 1820s.”

Emilie also told me that an 1825 letter digitized on the Foundation’s “Jefferson Quotes and Family Letters” page describes Martha Woodward making another drawing that year of Monticello’s West Front “from nature” and from “a position at the edge of the Grove.”

The Foundation, Emilie said, has a set of two other Woodward drawings in their collection. One includes an 1827 date and both are associated with Septimia Meikleham (1814-87), Ellen Randolph Coolidge’s youngest sister.

As far as the date of the Woodward drawing, its paper, Emilie said, has an 1834 watermark, which strongly indicates it was made that year. She also said that the 1825 and 1834 drawings present “quite similar” views of the house, except the trees in the later drawing “are larger and fuller than the other. The hand is quite different—details of the house, like the bricks, are more finely rendered in the later picture.”

So it appears that Martha Woodward “got much better as an artist in the 5-10 years between these works.” On the other hand, “the Woodward sisters were involved with female education, so maybe the 1834 drawing is by a teaching artist and [the 1825 one] is a student’s work.”

As for my $64,000 question—If the painting is from 1834, did Woodward romanticize it to show Monticello in pristine condition when we are all but certain it was in sad shape?—Emilie said that “it seems like this work connects to Woodward’s visits here in the mid-1820s (perhaps through sketches or memory), rather than Woodward coming back to the property after Uriah Levy bought it.”

So it’s possible that the 1834 painting is “based off her sketches and memories, and maybe extrapolated tree growth” or perhaps “an art teacher who was associated with the Woodward family’s educational interests” painted it.

Unless and until more information comes to light about the 1834 drawing—if the second drawing is Woodward’s work—Emilie said, she agrees with my thought that “Woodward probably was romanticizing her view, as well as perhaps reveling in her improved artistic facility.” Meanwhile, it’s indisputable that “they are a remarkable pair of drawings, as much for their view of the more often overlooked East Front as for the concept of change over time they represent.”

Stay tuned for updates as Emilie and her colleagues continue to look into Martha Woodward and the two paintings.

p.s. If you’re a historic house preservation nerd as I am, I highly recommend the Monticello Curatorial, Collections, and Restoration team on Instagram at “preservingmonticello”

‘THE LEVYS OF MONTICELLO’ DOC: I asked my friend and colleague Steven Pressman to fill SM Newsletter readers in on his visit to Savannah last month for the first in-person showing of his great new documentary, “The Levys of Monticello.” It took place at historic Mickve Israel, the nation’s third-oldest Jewish congregation, which was established in 1733 by 40 Jews who had journeyed from Portugal, via London, escaping the Inquisition.

Here’s Steve’s report:

I had the great honor of showing ‘The Levys of Monticello’ at Congregation Mickve Israel as part of the Savannah Jewish Cultural Arts Festival. Not only was this my first trip to Savannah, but it was also a special thrill for the film to be shown at a synagogue that played such a pivotal role in the Levy family story.

As readers of Marc’s book know, Uriah Levy’s great-great grandfather, Dr. Samuel Nunez, was among a small group of Jews who sailed from London to Savannah in 1733 and went on to form the Mickve Israel Congregation.

The film screening was also memorable for me because—thanks to the pandemic—it happened to be the first time in two years that I was able to show one of my films to a live, in-person audience. There was even popcorn for sale before the movie started.

EVENTS: Just one event his month: A talk on the history of the American flag, based on my book, Flag: An American Biography, on Tuesday, April 19, at the monthly meeting of the George Mason DAR Chapter in Springfield, Virginia.

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello—or for any of my other books, please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on other upcoming events, check the Events page on my website: https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me at marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

March 3, 2022

March 2022

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson Volume XIX, Number 3

March 1, 2022 “The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

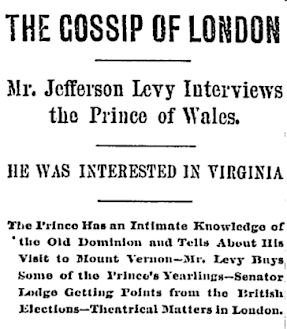

OUR MAN IN LONDON: I’ve often described Jefferson Monroe Levy as a late-19th and early 20th-century jetsetter. That’s because after he made a fortune in real estate and stock speculating Levy was forever—not jetting off—but sailing off to London, Paris, Biarritz, Rome, and the Riviera and training off to Palm Beach on the posh Florida East Coast Railway.

During those jaunts Jefferson Levy mixed and mingled with other upper-crust folks, saying in posh hotels, dining in five-star restaurants, and partaking in many a high society social event.

Case in point: Levy spent most of the summer of 1895 in England and on the Continent, a sojourn I mention briefly in Saving Monticello. That trip included a memorable few days in July in England where Levy hobnobbed with the rich and famous.

The highlight of the trip came on July 11, when Jefferson Levy was among the guests at Sandringham House, the opulent, 8,000-acre royal residence near the Norfolk Coast owned by the Prince of Wales, the oldest son of Queen Victoria and Price Albert—the man who would give his name to an era when he ascended to the throne as King Edward VII six years later.

The occasion: the sale of a portion of the collection of the Prince’s hackney horses. The Washington Post reported that William Waldorf “Willie,” Astor, the English-American son of the fabulously wealthy industrialist John Jacob Astor III, paid the princely sum of $5,000 for “a pair of [the Prince’s] harness horses.” For his part, Jefferson Levy bought a yearling, which he promptly gave to John Thomas North, a close friend of the Prince of Wales known as the “Nitrite King” of England, who, the article said, “did most of the buying.”

The Prince of Wales (in photo below), the Nitrite King (so named because he owned all the nitrite mines in Chile), and the 33-year-old owner of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello joined a who’s who of royals for lunch following the sale. The guest list included the Duke of York (the Prince’s son, who would become King George V in 1910) and the Duchess (Mary of Teck); Charles Richard John Spencer-Churchill, the 9th Duke of Marlborough; the Crown Prince of Denmark; the Duke of Sparta; and a gaggle of lesser British and lords and ladies.

After lunch, Jefferson Levy had “a long talk with the Prince,” Levy told The Washington Post, “and he gave me a special invitation to come and see him again.

“He asked a number of questions about America, but he seemed especially interested in Virginia. I was surprised at his intimate knowledge of the Old Dominion. He told me all about his visit to Mount Vernon, when he was in America, and said he would like to go there again, but had not the time.”

Levy went on to say he was less impressed by the Prince’s son. “I sat by the side of the Duke of York at lunch,” he said. “He is a fine fellow but he has not the charming manner which his father possesses.”

‘THE LEVYS OF MONTICELLO’ DOC: I’m happy to report that “The Levys of Monticello,” Steven Pressman’s terrific new documentary that tells the story of the post-Jefferson history of Monticello, was the subject of an excellent review and article in The Times of Israel newspaper last month. In it, reporter Renee Ghert-Zhand noted that the film used “a limited number of available archival images, on-screen interviews with experts [including yours truly], and dramatic readings of historical letters and statements” to come up with a “compelling narrative.” You can read the entire review at: https://bit.ly/TimesofIsraelReview

A week later the doc won the Building Bridges Award at the Atlanta Jewish Film Festival. The award, presented in conjunction with the American Jewish Committee, goes to the film that best exemplifies the festival’s main mission of fostering understanding among diverse religious and cultural communities. “This well-researched documentary poignantly reveals the parallel but very different stories, of the Black and Jewish connections to Monticello.” said Rabbi Noam Marans of the American Jewish Committee, who was on the Building Bridges jury. You can see the virtual award presentation at https://bit.ly/FilmFestPrize

Next up: a live (and virtual) screening on Sunday, March 6, at Congregation Mickve Israel in Savannah as part of the Savannah Jewish Cultural Arts Festival. More info at https://bit.ly/SavannahDoc

Stay tuned here for news of more film festival screenings in the coming months.

EVENTS: Just one event his month: A talk on the life of Francis Scott Key, based on my book, What So Proudly We Hailed: Francis Scott Key, a Life, for the monthly meeting of the Eliza Monroe Chapter of the National Society Daughters of 1912, on Thursday, March 10, in Alexandria, Virginia.

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com For details on other upcoming events, check out the Events page on my website: https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me at marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

February 4, 2022

February 2022

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 2 February 1, 2022

“ The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

THE COOLIDGES OF BOSTON: About a year before Thomas Jefferson died, on May 27, 1825, the nation’s third president and his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph hosted the wedding of his favorite granddaughter in the parlor of Monticello. On that day the reserved but adventurous Eleonora Wayles Randolph—known as Ellen—married Joseph Coolidge, Jr., the son of a Boston Brahmin merchant. She was 28 years old.

The couple had met when Joseph Coolidge, who graduated from Harvard in 1817, paid a two-week visit to Monticello in 1824 following his grand tour of Europe.

After a six-week traveling honeymoon, the couple moved to Boston. That state of affairs would become a blessing for Jefferson family and Monticello historians as Ellen (above) and her sisters and mother wrote a steady stream of letters back and forth between Boston and Charlottesville for decades.

Many of those letters are archived at the Alderman Library at the University of Virginia, and they proved to be valuable primary source material that I relied on heavily for putting together the first part of Saving Monticello. In that part of the book I cover Jefferson’s last years, the conditions that left him $107,000 in debt when he died, and the family’s reluctant decision to sell Monticello in 1827.

Ellen and Joseph Coolidge maintained a strong interest in Monticello following her grandfather’s death on July 4, 1826, and the sale of the property by her mother and her brother Thomas Jefferson Randolph to James Turner Barclay in 1831. The Coolidge descendants continued to be associated with Monticello during the years (1834-1921) Uriah Levy and Jefferson Monroe Levey owned the property.

Ellen and Joseph Coolidge maintained a strong interest in Monticello following her grandfather’s death on July 4, 1826, and the sale of the property by her mother and her brother Thomas Jefferson Randolph to James Turner Barclay in 1831. The Coolidge descendants continued to be associated with Monticello during the years (1834-1921) Uriah Levy and Jefferson Monroe Levey owned the property. As I wrote in the book, Ellen and Joseph’s son, Thomas Jefferson Coolidge (1831-1920), tried to buy Monticello from Uriah Levy’s estate in the late 1860s. T. J. Coolidge (right), who would later become president of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad and serve briefly as U.S. ambassador to France (as his great-grandfather had) gave up on acquiring Monticello after trying to deal with the two Levy family partition lawsuits that were slowly wending their way through the courts as the family fought over Uriah Levy’s will.

Archibald Cary Coolidge (1866-1928), a grandson of Ellen and Joseph Coolidge, also took a strong interest in Monticello. A Harvard history professor and the first director of the Harvard University Library, Archibald Coolidge was a founding executive officer of the Council on Foreign Relations in 1921.

He spent two years of elementary school, 1875-77, studying at Shadwell just outside Charlottesville, a private school run by his Aunt Charlotte Randolph, where he took first learned about his illustrious his great-great grandfather, Thomas Jefferson.

As I noted in Saving Monticello, in 1889, two years after graduating from Harvard, Archibald Cary Coolidge put up $5,000 of his own money and attempted to borrow $30,000 from his father and other family members to induce Jefferson Levy to sell Monticello. That effort failed, as did another one two years later.

Archibald Cary Coolidge (left) went on to become an active member of the Monticello Association, the Jefferson family organization that formed in 1913 to administer the family graveyard, which did not convey with the sale of the house in 1831, and remained in possession of the Jefferson-Randolph Family. Archibald was the group’s president, from 1919-1925.

Archibald Cary Coolidge (left) went on to become an active member of the Monticello Association, the Jefferson family organization that formed in 1913 to administer the family graveyard, which did not convey with the sale of the house in 1831, and remained in possession of the Jefferson-Randolph Family. Archibald was the group’s president, from 1919-1925. That’s his father, Joseph Randolph Coolidge and an unidentified family member photo below, which I only recently discovered, at the graveyard on the mountaintop in the late 1880s, about the time Archibald Coolidge was trying to buy Monticello.

After the Coolidge Family purchased Tuckahoe, the old Randolph family estate on the James River in 1898, Archibald Coolidge was a frequent visitor to Virginia, and became active in the Virginia Historical Society. He is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass.—not at Monticello—the same place where his mother Ellen, who died in April 1876, six months short of her hundredth birthday, is interred.

OH, ATLANTA:

“The Levys of Monticello,” Steven Pressman’s new documentary based on Saving Monticello, will be premiering this month at the Atlanta Jewish Film Festival, the first of what will be a series of screenings at film festivals around the country. Because of the pandemic, the Atlanta Film Festival is not doing in-theater screenings. Instead, all of the screenings will be held virtually.

That means that “The Levys of Monticello” will be available to viewers during the entire festival, from February 16-27. However, festival’s online films can only be seen by people in Georgia, as well as by members of the AJFF, and festival sponsors. All the details are on the festival’s website, www.ajff.org

The good news is that, as of right now, an in-person screening well be held on Sunday, March 6, at the historic Congregation Mickve Israel, in Savannah during the Savannah Jewish Cultural Arts Festival, formerly the Savannah Jewish Film Festival. Steven Pressman will be on hand for a Q&A after the screening. More info on that, and a link to the trailer, go to https://bit.ly/SavannahDoc

EVENTS: Just two in February. On Thursday, February, 3, I will do a talk on Saving Monticellovia Zoom for the Clifton (Va.) Community Woman’s Club.

And on Thursday, February 17, at 4:30 p.m. Eastern, I will be part of a discussion entitled, “The American Flag as a Cultural Symbol.” I will be on a panel moderated by Kevin Lindsey, the CEO of the Minnesota Humanities Center. I’ll be sitting in virtually to give my perspective based on my book, Flag: An American Biography. The other panelists will be live at the University of Minnesota’s Northrop’s Best Buy Theater.

The event is free and open to the public. For more info and to register, go to https://bit.ly/UMinnPanel

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello—or for any of my other books, please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on other upcoming events, check out the Events page on my website: https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me at marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

The SM Newsletter on Line: You can read back issues of this newsletter at http://bit.ly/SMOnline

January 6, 2022

January 2022

Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 1 January 1, 2022

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

‘MOST CAREFULLY PRESERVED’: In 1897, Jefferson M. Levy, who had owned Monticello for nearly twenty years, received a letter from one of the most famous men in America—the once and future Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan.

The populist politician and famed orator, an unabashed admirer of Thomas Jefferson, wrote to Levy seemingly out of the blue in April suggesting that he sell Monticello to the federal government, which would turn it into a national shrine to Thomas Jefferson. This was just six months after Bryan—at 36, the youngest man ever to run for the presidency—had narrowly lost the 1896 election to Republican William McKinley.

As I wrote in Saving Monticello, the story broke in the April 9, 1897, New York Herald in an article reporting that Bryant asked Levy to name a selling price for Monticello and also outlined his idea for turning the house into a national Jefferson memorial. Jefferson Levy’s reply, according to the newspaper, was that “not all the money in the United States Treasury would induce him to part with it.”

In a subsequent editorial, the Herald advised Bryan to give up his plan, and strongly endorsed Jefferson Levy’s stewardship of Monticello, providing a snapshot of Monticello’s condition under his than 18-year ownership of Jefferson’s “Essay in Architecture.” To wit: “It must be admitted, and happily so, Mr. Levy is keeping up the estate better perhaps than the government would do. Mr. Levy does not live there. He rarely, indeed, visits the historic spot, but he spends annually a good deal more than a senator’s salary in keeping the house and grounds intact. His chief pride is maintaining [Monticello] exactly as it was in Jefferson’s day. The mansion itself is most carefully preserved.”

With Levy closing the door, Bryan turned his attention elsewhere, and Jefferson Levy went about his business—which was booming. He was raking in money with his real estate holdings and stock trading, traveling to Europe regularly, and generally enjoying the good life.

He also made his first foray into politics, winning a New York City seat in the House of Representatives as a Democrat in the 1898 elections. Soon after taking office in 1899, Jefferson Levy became a well-known figure in Washington. In the next few years his social life, his many six-figure real estate deals, his high-stakes stock speculating, and his political views were regularly and prominently reported in newspapers in New York, Washington, Charlottesville, and throughout the country.

************************

I reported on more than a few of those newspaper articles in the book, and I recently found details about a light-hearted story involving Levy, Bryan, and what Thomas Jefferson like to serve for dinner at Monticello.

In the first months of 1899, Bryan was the leading contender for the 1900 Democratic presidential nomination—which he would secure (and lose again to McKinley). The Democrats were still divided over fiscal policy, with Bryan leading the free silver forces, as he did in 1896 when he gave him famous “Cross of Gold” speech at the Democratic National Convention.

The rivalry with the gold standard faction led to a small contretemps over Bryan’s refusal to attend a $10-a-plate April 13 Jeffersonian dinner put on by the gold crowd. Instead, Bryan decided to host a $1-a-plate affair, more in line with his free silver platform and his populist principles in general.

As the war of dinner words heated up on social media—newspapers throughout the country, that is—an enterprising reporter in Charlottesville sought out Jefferson Levy on the topic of Thomas Jefferson’s dining preferences.

Here’s what a hungry public learned from Levy on that meaty subject. Although Thomas Jefferson, Levy said in a widely reprinted newspaper article, “was exceedingly simple in his manners, he liked a good dinner, and kept a table that was noted for its excellent viands.” According to Levy, Jeffersonian Monticello dinners were “not served on common tableware, but on silver. Almost every day he had distinguished guests at his table, and he did not give them hog and hominy and coffee with long sweetening.”

Instead, Jefferson served “the very best of his plantation and the markets offered. In fact, he was noted for his fine dinners. He had lived in the best society of Europe, and he knew what a good dinner was.”

Then Jefferson Levy weighed in on the Jefferson dinner mini controversy, saying that if he were alive, the Sage of Monticello definitely would go for the $10 dinner.

EVENTS: I have two this Zoom talks for Context Conversations in January. The first, on, Monday, January 17, at 5:00 p.m. Eastern, is on Saving Monticello. More info at: https://bit.ly/ContextTalkSavingM

The second, on Monday, January 24, also at 5:00, is on Desperate Engagement, my history of the Civil War Battle of Monocacy and the subsequent attack on Washington, D.C. More info and to register: https://bit.ly/ContextDesperateEngagement

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello—or for any of my other books, please email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on other upcoming events, check out the Events page on my website: https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me at marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag: An American Biography; and Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.