Marc Leepson's Blog, page 8

June 3, 2020

June 2020

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVII, Number 6 June 1, 2020

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

UNCLE JEFF: Jefferson Levy’s mother Fanny served as his unofficial hostess at Monticello soon after the life-long bachelor bought out his uncle’s heirs and gained control of the property in 1872. Following Fanny Levy’s death in 1893, Jefferson Levy’s sister, Amelia Mayhoff, took over that job.

As I noted in Saving Monticello, Amelia Levy had married Carl Mayhoff, a New York City cotton broker, in 1890. They lived most of the year in New York City on East 34th Street, the same block where Jefferson Levy lived. The Mayhoff’s son, Monroe, was born in 1897.

Sisters Agnes and Frances Levy with their cousin, Monroe Levy, on the lawn circa 1902

Sisters Agnes and Frances Levy with their cousin, Monroe Levy, on the lawn circa 1902During the seasons when she was in charge at Monticello, Amelia Mayhoff arranged innumerable social events, with and without her brother present. She and her husband occupied a suite of rooms on the first floor.

The other family members who spent the most time at Monticello were Jefferson Levy and Amelia Mayhoff’s brother L. Napoleon, his wife Lilian Hendricks Wolff, and their four daughters—Frances, Agnes, Florence, and Alma. The account I gave of their days at Monticello in the book was primarily based on a mid-1970s interview with Florence Levy Forsch—along with copies of hand-written letters her older sister, Frances Wolff Levy Lewis, wrote from Monticello in 1902 when she was nine years old.

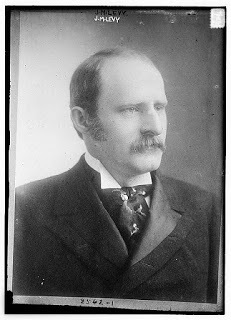

Uncle Jeff

Uncle JeffJust last week, Frances Lewis’ grandson Richard Lewis kindly sent me two pages from a short, unpublished memoir she wrote in the early 1960s, in which she remembers Jefferson Levy and visits to Monticello. Most of what she writes jibes with her sister Florence’s remembrances, as well as with all with the other primary-source materials about Jefferson Levy and Monticello during his ownership that I’ve uncovered. But the memoir also contains some observations that I’d not come across before.

Frances Lewis described her uncle as a “very tall and big man,” and said that her family visited “Uncle Jeff” regularly at his lavish New York City townhouse on 34th Street. She said that her Aunt Amelia “kept house for her family,” as well as for her two bachelor brothers, Jefferson M. and Mitchell Abraham Cass Levy.

She went on to give a revealing glimpse into Jefferson Levy’s early twentieth century lifestyle.

“On Sunday mornings,” she wrote, “we would be sent in to see Uncle Jeff, who would be lying on a big four poster bed, surrounded by the Sunday papers and there would be two big greyhounds stretched on the bed beside him.

The memoir confirms, as Fran Lewis put it, that during their childhood she and her sister Agnes “often were brought down to stay a few weeks in Monticello in the summer.” She said that her Aunt Amelia—who liked her nieces to call her “auntie”—presided over a household with a good number of African American “maids who lived in the old slave quarters, which were underground outside the main house.”

Today, those quarters, known as the South Wing, house several exhibits that document the lives of enslaved African Americans at Monticello. The lineup includes the spectacular digital exhibit on the life of Sally Hemings and the Getting Word project, which tells the history of Monticello’s enslaved people primarily through the oral histories of their descendants. There’s also the restored post-1809 Kitchen and Cook’s Room.

Fran Lewis describes her aunt Amelia as “a smart woman and a gracious hostess to many important people who came to visit Uncle Jeff and [who] gave many parties in the beautiful parlor where there was a large malachite table and many fine oil paintings.

“The floor was highly polished and we children were never allowed to enter that room except on one occasion when President Theodore Roosevelt came to visit [on June 17, 1903] and Agnes and I and Monroe were sent in to shake hands with him.”

Jefferson Levy, she said, “slept in Thomas Jefferson’s room,” known today as the Bed Chamber, which famously features Jefferson’s alcove bed. It’s conceivable that Jefferson M. Levy slept in the alcove bed.

On the other hand, a visitor to Monticello in 1900 wrote that Jefferson Levy installed “a gold Louis XV bed” on a “dais” in the Bed Chamber, upholstered in “damask, while voluminous blue damask curtains draped to each side fell from a gold coronet that hung from the ceiling.”

Fran Lewis said that her uncle had “many” greyhounds, including his favorite, Duke, who “always slept in Uncle Jeff’s room.”

Fran (who was known as Fanny as a child) described some of the farming operations at Monticello, including a “field with about 50 Shetland ponies and one Palomino, which belonged to Monroe, who would ride him around the back lawn.”

Frances Lewis at Monticello, 1959

Frances Lewis at Monticello, 1959Thomas Rhodes, Jefferson Levy’s overseer at Monticello, also ran a diary operation on the mountain. “There were cows,” Fran Lewis said, “and in the evenings we would go down the hill to watch them be milked, and even tried to do it ourselves.”

The children also occasionally played in the Jefferson family cemetery. “We would go down the hill and squeeze between the bars,” Fran Lewis wrote, “and play inside. Back at the house, the children “would chalk out a hop scotch” on the roof of the former slave quarters. When it rained, they scampered up one of the narrow staircases in the house to the top floor, and explored the Dome Room “where all sorts of things were stored, including a two wheeled gig that Thomas Jefferson rode in when he went to sign the Declaration of Independence.”

L. Napoleon Levy (wearing the dark hat) and his daughters Agnes, Alma (on the pony), Fanny, and Florence, with their cousin Monroe Mayhoff (holding the pony). The man on the right, identified as Willis, likely is Stanley Ferguson, a Monticello gatekeeper. Willis Shelton, a long-time gatekeeper, died in 1902. Photo courtesy of the Lewis family.

Jefferson, indeed, did drive that one-horse gig, which was built by enslaved people at Monticello, on two six-day journeys from the mountain to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1775 and 1776. As I noted in Saving Monticello, the gig remained unused and unchanged after it was stowed away upstairs at Monticello following Jefferson’s death, although its wheels and shaft had disappeared by the time Jefferson Levy had taken over.

The house and grounds “were truly beautiful,” Fran Lewis wrote, “as Jefferson Levy spent large sums of money restoring the house and buying furnishings.”

That sentence is 100 percent accurate, and jibes with every other first-person account of Monticello during Jefferson Levy’s ownership.

EVENTS:My scheduled live events for the spring and summer have been canceled or postponed due to the pandemic. To check out my scheduled late 2020 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, feel free to send me email at marcleepson@gmail.com For info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me. I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Published on June 03, 2020 12:35

May 4, 2020

May 2020

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVII, Number 5 May 2020

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

LEVY LAUNCHING: The United States Navy considers Uriah Levy a genuine hero. And rightfully so. Uriah Phillips Levy joined the Navy in 1812 at age twenty. He served with distinction during the War of 1812 as assistant sailing master of the USS Argus, which wreaked havoc with British shipping in the English Channel, capturing and burning more than two dozen ships.

He went on to have a fifty-year career in the Navy, the first Jewish American to do so. He rose through the ranks to become a Commodore, the Navy’s then-highest rank, becoming the first Jewish American Navy Commodore.

Uriah Levy also was primarily responsible for abolishing flogging in the U.S. Navy. He began a campaign to do so in the 1840s, which led to congressional action abolishing that antiquated, brutal punishment.

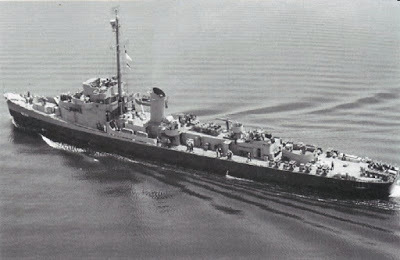

The Navy first formally recognized Uriah Levy—who owned Monticello from 1834 until his death in 1862—during World War II by naming a newly commissioned Cannon-class destroyer escort the USS Levy in 1943.

The USS Levy at sea in the Pacific during World War IIThe Levy, dubbed a “sub-killer,” was launched at 1:45 in the afternoon of March 28, 1943, at the Port Newark Yards in New Jersey. “The swift and deadly ‘sub-killers’ are nearly as large as destroyers,” the New York Herald Tribune reported, “but of simpler construction and less heavily armed. They [weigh] 1,300 tons each and cost about $3.5 million each.” Their “armament includes guns heavy enough for surface engagements with submarines, anti-aircraft batteries, depth charges and torpedo tubes.”

The USS Levy at sea in the Pacific during World War IIThe Levy, dubbed a “sub-killer,” was launched at 1:45 in the afternoon of March 28, 1943, at the Port Newark Yards in New Jersey. “The swift and deadly ‘sub-killers’ are nearly as large as destroyers,” the New York Herald Tribune reported, “but of simpler construction and less heavily armed. They [weigh] 1,300 tons each and cost about $3.5 million each.” Their “armament includes guns heavy enough for surface engagements with submarines, anti-aircraft batteries, depth charges and torpedo tubes.”Twenty years ago, while researching Saving Monticello, I discovered that Jefferson Levy’s sister Amelia Mayhoff, (and Uriah’s niece), hosted (“sponsored” in Navy parlance) the ceremonial launching. But I just learned some other facts about the ship and the Levy family from an article that Levy descendant Tom Lewis recently ran across and kindly sent to me.

The article, in the Long Branch, N.J., Record, reports that the idea to name a ship in honor of Uriah Levy came from a veterans service organization, the Jewish War Veterans of the United States, which lobbied the War Department to do so. It also notes that Tom Lewis’ grandmother Frances Lewis (referred to as “Mrs. Harold L. Lewis”) represented the family at the ceremonies. The Levy went on to perform well during World War II. The ship served in the southern and central Pacific from August 1943 through the end of the fighting. Among its accomplishment of note, the Levy supported the invasion of the Marianas in the summer of 1944, and its officers hosted the surrender ceremonies of the Japanese Navy in the southeastern Marshall Islands at Mili Atoll. BABBLING BROOKE: Sometimes during my talks on Saving MonticelloI take a brief detour when I get to Maude Littleton—who led the 1911-18 campaign to take Monticello from Jefferson Levy—to talk about her husband, Martin Wiley Littleton.

A prominent lawyer and one-term Democratic Congressman from Long Island, New York, Martin Littleton (1872-1934) was a noted figure in his own right. His notoriety derived primarily from his skillful defense ofthe playboy millionaire Harry K. Thaw in the 1908 second round of the first media-celebrated American “trial of the century.”

Shaw had shot and killed the renowned architect Stanford White on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden. That sensationally sordid affair—the subject of E.L. Doctorow’s novel (and the film and Broadway show) Ragtime—centered on White’s affair with Mrs. Shaw, the famed model and actress Evelyn Nesbit known as “The Bird in the Gilded Cage” because her husband kept her away from society.

Knowing most post-Baby Boomers likely don’t know the name Evelyn Nesbit, I used to explain that she was the “Madonna of her time.” That’s given way to the Kim Kardasian or the Lada Gaga of her time.

Evelyn Nesbit, "The Bird in the Gilded Cage"

Evelyn Nesbit, "The Bird in the Gilded Cage"I flashed back to Evelyn Nesbite when I recently learned of a connection between Jefferson M. Levy and Frances Evelyn “Daisy” Maynard (1861-1938),another beautiful, flamboyant early 20th century woman. Born into British high society, she later became Lady Brooke and then the Countess of Warwick after her husband, Francis Grevile, Lord Brooke, became the 5thEarl of Warwick. Rumor had it that Lady Brooke inspired the popular song “Daisy Bell (Bicycle Bult for Two),” which burst on the scene in 1892 when she was 31 and one of London’s most famous and active socialites. Her media nicknames included “The It Girl,” “My Darling Daisy,” and “Babbling Brooke.”

Lady Brooke’s flamboyant lifestyle included open love affairs with several rich and famous Englishmen, including Lord Charles Bereford, a renowned British Navy admiral and member of Parliament. She had a ten-year affair with Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, who later acceded to the British throne as King Edward VII in 1901, ushering in the Edwardian Era.

Lady Brooke

Lady BrookeWhat’s Lady Brooke’s tie to Monticello? Well, in 1907, at the height of her celebrity, she journeyed to the United States for a whirlwind of high-society activity. Lady Brooke spent most of that time in New York City, where she stayed with none other than Jefferson M. Levy, the big real estate and stock speculator—and very eligible bachelor—whom the Charlottesville Daily Progress described as her “legal adviser.”

In October, the Countess decided to make a trip to Monticello, her legal adviser’s country home in Virginia. Later that month Levy—a pre-jet jetsetter who hobnobbed with royals and other upper-crusters on two continents—hosted a dinner for the Bishop of London at Monticello. Among his guests was his house guest, the Countess of Warwick.

That’s the extent of our knowledge about the relationship between one of Europe’s most flamboyant socialites and one of America’s richest men. I will continue to search for more.

EVENTS: Just one event in May. On Sunday afternoon, May, 3, I did a Zoom talk as a fund-raising benefit for the nonprofit Mosby Heritage Area Association, a historic preservation group that focuses on “preservation through education” in the Northern Virginia Piedmont where I live. My scheduled live events for the spring and summer have been canceled or postponed due to the pandemic. To check out my scheduled late 2020 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

Doing the Zoom talk in the shadow of the Bull Run Mountains

Doing the Zoom talk in the shadow of the Bull Run MountainsIf you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, feel free to send me email at marcleepson@gmail.com For info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me. I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Published on May 04, 2020 13:10

April 4, 2020

April 2020

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVII, Number 4 April 1, 2020

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

IN MEMORIAM: I am deeply saddened to report that Harley Lewis, a great-grandniece of Uriah Levy and a grandniece of Jefferson M. Levy—and one of the last members of her generation of Levy descendants—died at her home in White Plains, New York, on March 24 at 94. My deepest condolences to Harley’s sons Richard, Jim, and Tom, and her brother Phillip, and to their families.

Harley was born on November 13, 1925, the daughter of Harold L. Lewis and Frances Levy Lewis, who was known as Fanny. Harley’s maternal grandfather was L. Napoleon Levy, Jefferson M. Levy’s brother. Her great-great grandmother—Uriah Levy’s mother, Rachel—is buried along Mulberry Row at Monticello after having died there in 1839, five years after Uriah purchased Monticello from James Turner Barclay.

Harley Lewis, circa 2011. Photo courtesy of Richard Lewis

Harley Lewis, circa 2011. Photo courtesy of Richard LewisAccording to her New York Times obituary, Harley graduated from Syracuse University in 1957, married Richard C. Lewis, and worked as a librarian in the Edgemont Public School system in Scarsdale, New York, and at Congregation Kol Ami in White Plains. Harley and Dick Lewis were very active in that congregation for many years. She served on its board, and was a founding member of the Westchester Coalition of Food Pantries & Soup Kitchens.

Harley was the keeper of much of her family’s Monticello history. When I started researching Saving Monticello in 1999, Dan Jordan, then the president of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation (which owns and operates Monticello), and Susan Stein, Monticello’s curator, spoke admiringly of Harley and strongly suggested that I contact her.

I visited Harley and Dick at their home in Westchester County and they couldn’t have been more kind, gracious, and welcoming. After feeding me lunch, Harley and I went through her extensive collection of family materials and she shared every one with me. Among many other things, she kindly gave me a copy of the unpublished memoir of her great grandfather, Jonas Levy, one of Uriah’s brothers. And she gave us permission to use two family photos in the book.

Here’s one of them: a picture of Harley’s mother Frances sitting in the buggy with her sister Agnes, with their cousin Monroe Levy on the lawn at Monticello sometime in the 1890s.

Harley told me about her mother and father’s recollections of visiting Monticello in the 1930s—and the less-than-welcome reception they (and other family members) felt there. On at least one occasion, they were refused permission to visit Rachel Levy’s grave, which was hidden from public view behind a locked gate.

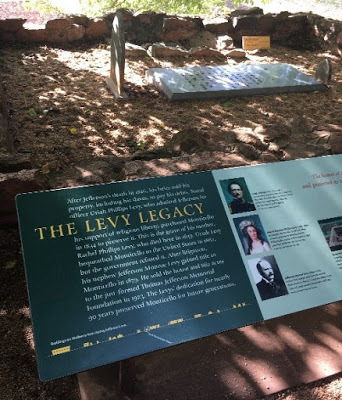

That situation didn’t substantially change until 1984 when Dan Jordan took over at the Foundation and began an effort to have the Levys’ role officially recognized at Monticello. The first step was refurbishing the Rachel Levy grave site and placing a plaque there honoring the family. On June 7, 1985, Harley and Dick Lewis and other family members and guests took part in a commemorative ceremony there. Dan Jordan welcomed everyone, saying the occasion marked the beginning of the Foundation’s recognition of the Levys’ “good stewardship” of Monticello.

The highlight came when Harley Lewis unveiled a new plaque at her great-great grandmother’s newly refurbished grave site that concluded with the words: “At two crucial periods in the history of Monticello, the preservation efforts and stewardship of Uriah P. and Jefferson M. Levy successfully maintained the property for future generations.”

Harley faithfully read every issue of this newsletter and regularly emailed me with kind words after each one came out. Her last email arrived on March 3. In it, she wrote, “You always come up with fascinating bits of family history. It makes my day to receive this news. Don’t stop sleuthing.” I won’t, Harley.

BETH ELOHIM: On a mid-March visit to Charleston, South Carolina, we had the chance to visit the historic Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim Synagogue two weeks before the nation went into widespread quarantining. The majestic building in downtown Charleston, which dates from 1840, is the country’s second oldest synagogue and the oldest one in continuous use. The congregation, which started in 1749, is the fifth oldest in the U.S. behind:

Shearith Israel, which began in 1654 in New York City

Congregation Jeshuat Israel, founded in 1658 in Rhode Island; its Touro Synagogue, dedicated in 1763, is the nation’s oldest synagogue building

Mickve Israel in Savannah, founded in 1733

Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia in 1740

The Nunez, Machado, and Levy families—including Uriah P. Levy and Jefferson M. Levy—worshiped at Shearith Israel and Mickve and Mikveh Israel. Work on the latest restoration of the sanctuary at Beth Elohim had ended just days before we toured the place. Took these pics:

EVENTS:I had several events scheduled for April. They’ve been cancelled or postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Hope to have speaking events set up this fall. To check out my scheduled late 2020 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, feel free to send me email at marcleepson@gmail.com For info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me. I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Published on April 04, 2020 10:59

March 3, 2020

March 2020

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVII, Number 3

March 1, 2020

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

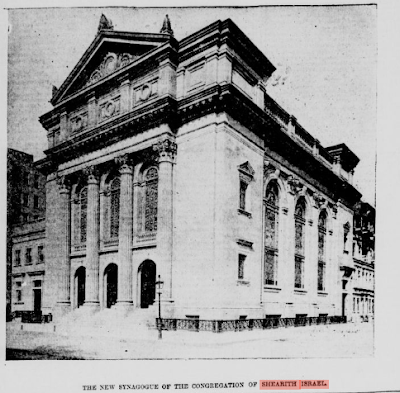

NEW EDIFICE: Members of the Levy/Phillips/Nunez family have been associated with New York City’s Shearith Israel, the nation’s oldest Jewish congregation, since 1734. That’s the year that David Machado, who married Uriah Levy’s great grandmother, Zipporah Nunez, moved to New York from Savannah to become the temple’s Hazzan (Prayer Reader).

As I noted in Saving Monticello, as Hazzan, The Reverend Machado, as he was known, had many duties, including granting licenses to inspect and kill cattle under Jewish dietary laws. He also conducted religious services and was responsible for reciting certain prayers.

Uriah Levy, who—when he wasn’t at sea or spending time at Monticello—lived in New York City from the 1820s until his death in 1862, was a member of the congregation. And his nephew, L. Napoleon Levy (Jefferson Levy’s brother), served as president of the Shearith Israel Congregation in the 1890s and early 1900s.

L.N. Levy, like his older brother Jefferson, was a New York City lawyer. In fact, the brothers became law and business partners. The younger Levy, who died at age 66 in 1921, headed the Congregation when the decision was made to build its fifth and current building on West 70thStreet and Central Park West on an uptown plot of land that been a duck farm.

The noted New York City architect and city planner Arnold Brunner (1857-1925) designed the imposing neo-classical building. Louis Comfort Tiffany did the interior design work, including—naturally—the stained glass windows.

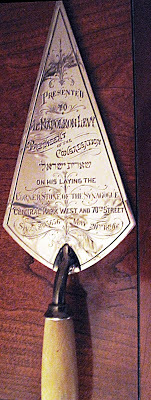

When it came time to lay the cornerstone for the new building, on May 20, 1896 (8 Sivan, 5656 on the Hebrew calendar), L. Napoleon Levy was given the honor. To mark the occasion, the Congregation presented him with an engraved trowel. A big thank you to Steve Lewis, a great-great grandnephew of Jefferson Levy, for sending me the terrific image of the trowel below.

The “fine new structure,” as the New York Journal and Advertiser put it, was dedicated, a year later, on May 19, 1897. Today, an engraved plaque on the ground floor recognizes L. Napoleon Levy’s leadership of Shearith Israel, and an auditorium in the synagogue is named in his honor.

A DANGEROUS SITUATION: Came across an anecdote about Jefferson M. Levy in a recently digitized article from the Philadelphia Post from November of 1903. In it, the paper snarkily relates a story involving Levy and the infamous Richard “Boss” Croker, the Irish-born (1843-1922) New York City Democratic political strongman who dominated the city’s politics from the early 1880s until he returned to Ireland in 1905.

It seems that in 1898 when Jefferson Levy first ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives from New York (and won) he had forgotten that, as the paper put it, “shortly after he began to live at Monticello” [in 1879], he had gone “to London and had cards printed bearing this legend…”

JeffersonMonticelloLevyVirginia

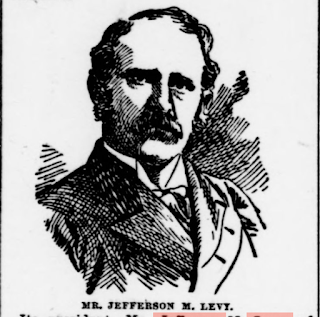

When the wily Crocker got wind of the business cards, he summoned Levy (below, in an 1890s newspaper sketch), and the conversation went something like this:

Crocker: “Mr. Levy, I understand one of the daily newspapers has one of those cards you were using in London and intends to print a picture of it.”

Levy: “Well?”

Crocker: “Well? Don’t you see the connection? If they print that card, like as not you will be barred from Congress. You say you are from Virginia, and you are elected to Congress from New York. You must get that card at all hazards. You must be cautious about it, too.

“If the newspaper people hear you want the card, they will doubtless print it. I like you and want to help you, but I warn you that this is a dangerous situation.”

At which point, the article noted, Levy “rushed away, very much frightened.”

During the “rest of the campaign, he had daily consultations with Mr. Croker as to ways and means for getting the card from the newspapers, and each morning he picked up that journal in fear and trembling and looked for the reproductions.”

The article reported that Croker enlisted some members of the NYC Democratic Club to help retrieve the potentially damning card. “There were hours of consultations over dinner tables,” the article pointed out, “Levy always picking up the checks.”Then one day Croker and company presented Levy with the card—and “demanded” that Levy “provide a banquet for those who had saved his seat in Congress.” Levy “responded liberally, and to this day he thinks he was kept in Congress by the efforts of Croker and his friends.”

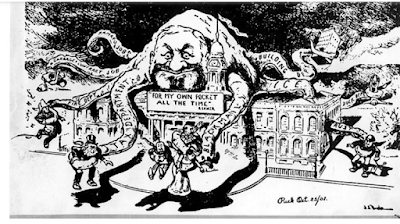

Thomas Nast cartoon showing Boss Croker's tentacles ensnaring N.Y. City HallThat article was the first I’d heard of the business card blackmail scheme—which doesn’t mean it’s not true. On the other hand, Jefferson Levy was no fool, and it stretches credulity to think that he’d fall for a blatant blackmail attempt that involved paying for lots of food and drink for his political bosses. On the other hand, crossing Boss Crocker would have cost Levy his critical support, and it’s entirely possible that’s why Levy kept paying for all those meals.

If so, that patronage paid off. Jefferson Levy ran for Congress three times, and won each race: in 1898, 1910, and 1912.

MARCH EVENTS:

· On Saturday, March 21, I’ll be receiving a National Daughters of the American Revolution History Award at the monthly meeting of the Falls Church DAR chapter in Falls Church, Virginia.

· On Thursday, March 26, I’m giving a talk on my one and only Civil War book, Desperate Engagement: How a Little-Know Civil War Battle Saved Washington, D.C., and Changed American History, as part of the Civil War Lecture Series at the GAR Hall in Peninsula, Ohio. More info at peninsulahistory.org/cwls

There’s always a chance I may add a last-minute talk or signing. For the latest on that, or to check out my other scheduled 2020 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, please send an email to marcleepson@gmail.comFor info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me. I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Published on March 03, 2020 12:27

February 3, 2020

February 2020

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVII, No. 2

February 1, 2020

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

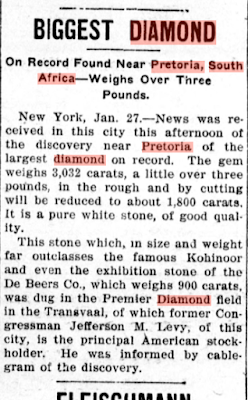

THREE-POUND DIAMOND: “The Second-Biggest Diamond in History Has a New Owner.” That headline in The New York Times on January 15 caught my attention because—well, who isn’t interested in the second-biggest diamond in recorded history?

The headline also called to mind something I’d discovered about Jefferson M. Levy twenty years ago while researching Saving Monticello. Going through stacks of newspaper clippings in the archives of the American Jewish Historical Society in New York City back then, I found two 1905 articles about Levy and the “largest diamond on record.”

Turns out that Jefferson Levy, the big New York City real estate and stock speculator who owned Monticello from 1879-1923, was the largest American stockholder in a syndicate called Premier Diamond that had just extracted a half-pound, 3,032-carat diamond out of a mine near Pretoria, South Africa.

Here’s the gist of what I wrote about that state of events in Saving Monticello: Levy, a “rich speculator,” I noted, “got immensely richer in January of 1905” when the South Africa miners discovered that giant stone

That state of events prompted the New York American on January 30 to ask: ‘Will Jefferson M. Levy, former [and future, as it would turn out] Congressman, capitalist and owner of Monticello, be the diamond king of America? Will his ownership of a large share of the great Premier diamond mine of the Transvaal from which a 3,032-carat stone was taken a few days ago, make the New Yorker a rival of the late Cecil Rhodes?’ ”

Levy, the paper went on to say, “will not say, but he does admit that luck has showered wealth upon him from an unexpected source which may exceed the wildest dreams of his fancy.”

“I really got into this thing quite by accident,’ Levy told the paper, “Constantly I am making investments, and when the diamond shares were offered me at what I considered a very low price, I took them. But even with my real estate and other large holdings, I almost forgot the Premier stock.”

The January 15, 2020, NYT article reported that the baseball-sized second-biggest diamond (below) that was discovered last year was the “the largest rough diamond discovered since 1905.” That 1905 stone, which would become known as Cullinan Diamond, likely was the one that Levy’s Premier Mine unearthed. Levy’s syndicate sold it to the government of South Africa (then known as The Transvaal), for around $750,000.

The government subsequently had it cut it up into two giant stones, and in 1907, in a goodwill gesture to help heal the wounds of the long (1899-1902) Boer War, gave the two stones to King Edward VII of England. Today they are incorporated into the English monarchy’s Crown Jewels. You can read the entire New York Times article at http://bit.ly/JMLdiamond

EVENTS:I have one event this month. On Wednesday, February 5, I’ll be doing a talk on Saving Monticello and a book signing at The Village at Orchard Ridge retirement community in Winchester, Virginia.

There’s always the chance that I may add a last-minute talk or signing. For the latest on that, or to check out my other scheduled 2020 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, feel free to send me email at marcleepson@gmail.com For info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me. I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Published on February 03, 2020 15:48

January 7, 2020

January 2020

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVII, Number 1 January 1, 2020

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

HAPPY 2020: And happy 17th anniversary to the Saving Monticello newsletter. This publication began in 2003 after I had attended a book-marketing panel at the Virginia Book Festival in Charlottesville and one expert advised starting a newsletter. I went with the newsletter form because in those days weblogs had just become known as “blogs” and weren’t on my radar.

I don’t know if I thought back then how long I’d keep doing the newsletter, but it’s pleasantly surprising that I have produced one every month since. It’s also been an unexpected pleasure to regularly find material I hadn’t come across while doing the research for the book twenty years ago. Thanks very much to all the SM Newsletter subscribers—especially those who have told me about newspaper and magazine articles and other primary-source materials that were new to me. I continue to search digital archives (thank you, Google University) for potential newsletter items, often while doing research for my other books. It’s always a shot in the arm when I come upon newly digitized material that augments what I have written in the book about the history of Monticello.

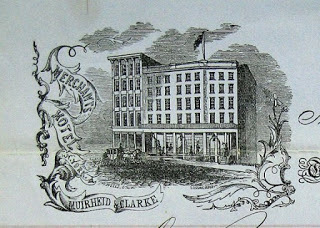

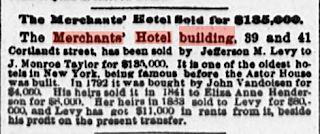

For example: I just found a one-paragraph article from The Sun, the old New York City newspaper, dated October 9, 1887, that provides details of Jefferson Monroe Levy’s ownership of the Merchants’ Hotel in New York City. That article buttresses what I wrote in Saving Monticello about how Levy became a millionaire around that time primarily through buying, selling, and managing real estate in his hometown—and in Charlottesville. (He also had great success as a stock market speculator.)I described some of Jefferson Levy’s more notable real estate dealings in the book. But I hadn’t known that he owned the Merchants’ Hotel for four years.

The Merchants' HotelOne of New York City’s oldest hotels, dating from the late 18th century, the Merchants’ also was one of the city’s most exclusive. It was “famous before the Astor House [the city’s first luxury hotel] was built in 1836,” according to the article. Jefferson Levy purchased the place in 1883 (four years after he’d bought Monticello) for $80,000, and sold it in 1887 for $185,000, more than doubling his investment.

The Merchants' HotelOne of New York City’s oldest hotels, dating from the late 18th century, the Merchants’ also was one of the city’s most exclusive. It was “famous before the Astor House [the city’s first luxury hotel] was built in 1836,” according to the article. Jefferson Levy purchased the place in 1883 (four years after he’d bought Monticello) for $80,000, and sold it in 1887 for $185,000, more than doubling his investment.Levy did well in that business venture. As the article noted, he also had received “$11,000 in rents from it, beside his profit on the present transfer.”

In the early and mid 19th century the Merchants’ Hotel on Cortlandt Street in Lower Manhattan—as its name implies—was a home away from home for out-of-town merchants. They came in New York mostly from the West and South, usually on semi-annual trips to “purchase goods [from][ the great wholesale houses,” as an October 10, 1887, New York Evening World article put it in announcing the sale—but not naming its new owner. The hotel “in those days was a much larger and more pretentious hostelry than it is now,” the paper said, “and covered two lots adjoining” Broadway. “It was a favorite resort for the merchants… who flocked here in thousands.”

The article went on to note that those merchants, with their “persuasive eloquence,” were known to “break the hearts of the chambermaids and dining-room girls right and left.”

Dining-room girls?

James Monroe (Thomas Jefferson’s Albemarle County neighbor) stayed at the Merchants’ Hotel in June 1817 when he became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the Big Apple, according to the 1915 book, Old Taverns of New York by William Harrison Boyles.

After a visit to City Hall to meet with the city’s mayor, Jacob Radcliff, and New York’s Gov. DeWitt Clinton, Boyles wrote, the President “was escorted by a squadron of cavalry to the quarters provided for him at Gibson’s elegant establishment, the Merchants’ Hotel in Wall Street.”

Following another round of official duties, President Monroe “returned to the hotel at five o’clock and sat down to a sumptuous dinner prepared for the occasion.” Among the guests were the former New York Gov. Daniel Tompkins, who then was Monroe’s Vice President, and sitting N.Y. Gov. Clinton.

The Merchants’, Boyles noted, was “selected as a proper place to lodge and entertain the President of the United States” because “there is hardly a doubt that it was considered second to none in the city.” The Merchants’ Hotel is long gone. Today, the 54-story skyscraper called One Liberty Plaza takes up the entire block of Cortlandt Street where the hotel stood, between Church Street and Lower Broadway, two blocks east of the 9/11 Memorial.

EVENTS:I have one event in January. On Sunday, January 12, I’ll be doing a talk on Saving Monticello for Sephardi Federation of Palm Beach County, Florida, at Temple Shaarei Shalom in Boynton Beach. I’ve done more than 225 talks on the book since it came out in 2001, but this will be a first. I’ll be doing it live—but electronically via Zoom.

There’s always the chance that I may have a last-minute talk or signing. For the latest on that, or to check out my scheduled 2020 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, feel free to email me. For info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me at marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Published on January 07, 2020 12:51

December 2, 2019

December 2019

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVI, Number 12 December 1, 2019

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

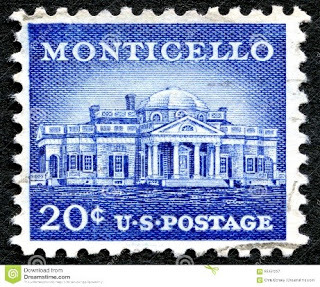

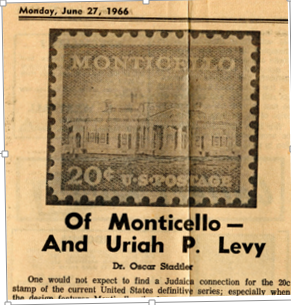

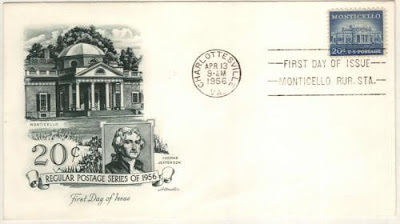

A RATHER FAMOUS PERSONALITY: On April 13, 1956, Thomas Jefferson’s 212th birthday, the U.S. Postal Service issued a new twenty-cent stamp at a ceremony at Monticello. The blue-and-white stamp shows the west front of Thomas Jefferson’s “Essay in Architecture,” the so-called “nickel view.” William K. Shrage who worked at the federal Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, designed the stamp.

Postmaster General Arthur E. Summerfeld spoke at the unveiling ceremonies that day at Monticello. In his remarks, Summerfield lauded Thomas Jefferson—and Monticello. The house, he said, reflects the “living evidence of the inner life of Jefferson.” Noting its “strength and dignity,” the Postmaster General said Monticello also “possesses deep artistic and cultural values,” has “noble simplicity,” is “highly practical and warmly livable,” and has “long been a symbol of our leadership for freedom.”

The new stamp, he said, “will herald to all the world our continued dedication to human freedom.”

Eleven years later, in June 1966, Linn’s Weekly Stamp News published an article by Dr. Oscar Stadtler—a Cleveland dentist with a strong interest in Jewish history and philately—titled “Of Monticello—And Uriah P. Levy.” In it, Dr. Stadtler wrote about Monticello’s unexpected “Judaica connection;” that is, the Levy family’s stewardship—the subject of Saving Monticello.

In the article, Dr. Statdler admiringly quoted from a Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation brochure, which reported that the Foundation bought Monticello from the Levy family, “which had owned it for over 75 years.”

Steve Lewis, a Levy descendant (a great grandnephew of Jefferson Levy and a great-great-great grandson of Uriah Levy’s mother, Rachel), kindly sent me a copy of this fascinating stamp magazine article, which I hadn’t seen.

I was pleased to see that most of the facts in Dr. Stadtler’s article about Uriah and Jefferson Levy and their ownership of Monticello were correct.

On the other hand, Dr. Stadtler had several facts wrong—most likely because he used the unreliable 1963 Uriah Levy biography, Navy Maverick, as his main source.

Most of the misstatements are trivial, including Jefferson Levy’s age when he died (he was 71, not 70). But Dr. Stadtler quoted from a letter that’s cited in Navy Maverick that is all but certainly made up. In it, Uriah Levy supposedly is writing to a business acquaintance in 1832, extolling Jefferson as the “greatest men in history—author of the Declaration of Independence and an absolute democrat.” He goes on to laud Jefferson for doing “much to mold our Republic in a form in which a man’s religion does not make him ineligible for political or government life. As a small payment for his determined stand on the side of religious liberty I am preparing to personally commission a statue of Jefferson.”

I quoted that letter in Saving Monticello, but pointed out in an endnote that the authors provided no information about the letter’s whereabouts, nor did they give its exact date. What’s more, I have repeatedly tried (as have other historians) to find the letter, and have come up empty.

Despite its dubious nature, that quote is often repeated as a convenient explanation for Uriah Levy’s 1832 decision to commission a seven-and-a-half-foot-tall statue of Thomas Jefferson in Paris. Among many other places, you can find the quote on the Uriah Levy page on Monticello’s website, which was written by Professor Mel Urofsky in 2001 and includes Navy Maverick as a source. It’s also on the UPL Wikipedia page.

Another error in Dr. Stadtler’s article: He says Uriah Levy decided to live at Monticello after he bought it in 1836 (the papers were signed in 1834, but closing was held up for two years), which is untrue. Then U.S. Navy Lt. Levy spent comparatively little time at Monticello, although he moved his elderly mother, Rachel Phillips Levy, into the house in 1837. She died two years later at Monticello, where she is buried along Mulberry Row.

Uriah’s permanent address when he wasn’t on a cruise was in New York City. He certainly visited Monticello, sometimes for weeks at a time, but not very often. On the other hand, I cannot argue with Dr. Stadtler’s characterization of Uriah Levy as “a rather fabulous personality.” If you read Saving Monticello, you will see just how fabulous he was.

THE MEDALLION:Uriah Levy, as I noted in Saving Monticello, spent a good deal of time in Paris during his Navy days. He even lived there for a year beginning in August 1828. The next time he returned to the City of Light, in 1832, Levy arrived with a mission: to commission a larger-than-life sculpture of Thomas Jefferson from one of the best-known sculptors of the day, Pierre Jean David d’Angers (1788-1856).

I covered that experience in depth in the book, including mentioning the oft-quoted suspect letter explaining why Lt. Levy took that extraordinary step.I didn’t realize until recently that David—the leading monument maker in Paris whose many commissions for statues, portraits, busts and medallions came from patrons throughout the world—also created a bronze portrait medallion of Uriah Levy at about the same time, most likely at Uriah’s request.

Susan Stein, Monticello’s long-time curator, emailed me last month to say that she had unexpectedly come across a copy of the medallion at the David d’Angers Gallery, which is located in the restored 13thcentury Toussaint Abbey (above), in David’s home town, the city of Angers in the Loire Valley.

I did a bit of searching and found that another copy is in the National Gallery of Art’s West Building in Washington, D.C., along with a sixteen-inch high bronze maquette of the Jefferson statue by David d’Angers that now stands in Statuary Hall in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol a few blocks away. As Susan told me, it’s great to see a “new” life portrait of Uriah Phillips Levy. That’s the medallion below, showing the forty-year-old, hirsute Navy lieutenant.

EVENTS:I have one event in December. On Thursday, December 12, I will be doing a talk on Saving Monticello and a book signing at the Washington, D.C. SAR Chapter’s annual Holiday Dinner in Washington, D.C.

There’s always the chance that I may have a last-minute talk or signing, especially around Christmas. For the latest on that, or to check out my scheduled 2020 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, feel free to email me. For info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me at marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Published on December 02, 2019 17:01

November 5, 2019

November 2019

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVI, Number 11 November 1, 2019

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

SEQUESTRATION: As I wrote in Saving Monticello, the Confederate States of America seized all of Uriah Levy’s Virginia land (including Monticello) under the sequestration terms of the CSA’s Alien Enemies Act—the law that the Confederate Congress had passed and Jefferson Davis had signed on August 8, 1861.

The Act called for the removal of all residents of northern states from the Confederacy. It also authorized the CSA to take possession of property in the South owned by ousted northerners. The clip below from the October 11, 1861, Richmond Enquirer, contains a list of the largest northern landowners in Virginia and their estates. The properties—which the article calls “estates held by alien enemies” would be confiscated—AKA “sequestered.”

According to an another article in the Richmond Examiner, which I quoted from in the book, the proceedings to sequestrate Monticello began on October 10, 1861, while “the present owner, Levy, [was] abroad being in charge of a United States ship of war.” The article went on to point out that the “people of Charlottesville called the late owner of Monticello ‘Commodore Levee.’ He is a first Captain in the United States Navy, and of Jewish parentage.”

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper of New York City reported the sequestration four months later, saying that Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello had been confiscated, along with “all its lands, negroes, cattle, farming utensils, furniture, paintings, wines, etc., together with two other farms belonging to the same owner, and valued at from $70,000 to $80,000.” The Union-friendly newspaper went on to expound on Uriah Levy’s patriotism and military service, and concluded: “Certainly no officer in the army or navy has been so victimized by the rebels.”

Coda: Uriah Levy fought the order in the Confederate courts; and the suit continued, as I note in the book, after he died in 1862. Finally, in November of 1864, the CSA prevailed and Monticello was sold to Benjamin Franklin Ficklin, a Confederate Army officer, who was forced to relinquish the property to Levy’s heirs after the Civil War ended in March 1865. Ficklin had paid the CSA $80,000 (in Confederate money) for the property.

NAVAL ACADEMY: It’s not every day that you get escorted through the security gate into the U.S. Naval Academy—much less give a talk following Friday night services at the amazing Miller Chapel, the certerpiece of the Academy’s Commodore Uriah P. Levy Center.

But that’s what happened on October 11, when Benno Gerson of the Friends of the Jewish Chapel and Rabbi Steve Ballaban, the Naval Academy’s Jewish Chaplain, graciously welcomed me to the gleaming chapel.

Rabbi Ballaban told me he’d keep the service short—and he was true to his word.

He then gave me a terrific introduction and I proudly stood in front of a group of midshipmen and members of the Annapolis Jewish community to fill them in on the life of Uriah P. Levy and his family, his distinguished naval career, as well as his—and his nephew Jefferson M. Levy’s—stewardship of Monticello, the heart of Saving Monticello.

It was a memorable evening, made even more special when I signed books for the Midshipmen and FOJC members at the Oneg following the service. My thanks to everyone who made the evening possible, especially Mr. Gerson, Rabbi Ballaban, and David Hoffberger, the facilities manager for all of the Naval Academy’s chapels.

SOUTHERN JEWISH: I had another memorable Saving Monticello experience on Friday, October 25, when I did the Keynote Speech at the 44th annual Southern Jewish Historical Society Conference in Charlottesville. The Conference organizer, Phyllis Leffler, an emeritus professor of U.S. History at the University of Virginia, invited me to do the talk, as well as to accompany two busloads of conference goes on an 8:30 a.m. special tour of Monticello that morning.

We broke into four groups and had a great tour that ended at the grave of Rachel Levy, Uriah Levy’s mother, who died at Monticello in 1839, and is buried on Mulberry Row (photo below). After the tour, we drove back to Charlottesville for lunch (featuring the famed local Bodo’s bagels) at the Brody Jewish Center, the home of U-Va.’s Hillel, a block from the University of Virginia’s grounds. I did the talk as the last bagels were being consumed.

I am extremely grateful to Phyllis Leffler, the current SJHS President and the Conference Program Committee Chair and Georgia State University History Professor Marni Davis, as well Hillel Rabbi Jake Rubin and Danielle Buynack, the Hillel Development Director, for putting on a special event. CORRECTION: Last month I mentioned that the Saturday morning Lift program at Congregation Kol Ami in White Plains, New York, was started by Harley Lewis—the Levy descendant who has helped me immeasurably with my research of her family and Monticello—and her late husband Dick. Harley emailed me, though, to say that they did not start Lift. “It was the genius of [Kol Ami] Rabbi Shira [Milgrom],” she wrote. “But we were at the first one… along with a few other congreganants and became devoted fans” of the program. I stand corrected—and honored that I was asked to be speak about Saving Monticello and the Nunez/Phillips/Levy family at the September 21, 2019, Lift.

EVENTS:I have two events in November. On Wednesday, November 6, I will be doing a talk on Saving Monticello and a book signing at the monthly luncheon meeting in Potomac, Maryland, of a retiree group of a large corporation.

The following evening, Thursday, November 7, at 7:00, I will be part of the screening of an excellent documentary called “Just Like Me: Vietnam War Stories from All Sides” by the filmmaker Ron Osgood at the McGowan Theater at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The event is free and open to the public. I will join Ron on stage after the screening to discuss it and take audience questions. For more info, go to http://bit.ly/ArchivesScreening

There’s always the chance that I may have a last-minute talk or signing. For the latest on that, or to check out my scheduled 2019 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, feel free to email me. For info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me at marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Published on November 05, 2019 12:13

October 5, 2019

October 2019

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVI, Number 10 October 1, 2019

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

SUCCESSIVE PARTIES OF VISITORS: Jefferson Levy, who owned Monticello from 1879 until he sold it to the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation in 1923, lived in New York City and was active in the state Democratic Party. He would go on to serve three terms as a U.S. Congressman from lower Manhattan from 1899-1910 and 1911-1915.

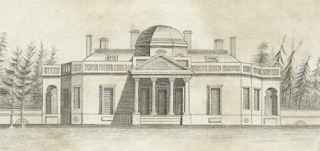

When Levy gained control of Monticello, the house and grounds were in terrible condition—as evidenced by the Saving Monticello cover image, the oldest-known photo of the Jefferson’s house, from around 1870. In 1879, Levy hired an on-site superintendant, a man named Thomas Rhodes, and began extensive restorations. By the summer of 1880, they had made enough progress repairing and restoring the place that Jefferson Levy felt comfortable inviting friends and relatives to visit Jefferson’s mansion.

As I noted in Saving Monticello, a Washington Postcolumnist in June 1880 wrote that Levy was “restoring the interior of the irregular old Monticello mansion and will make it both in finish and furniture as nearly what it was in Mr. Jefferson’s time as possible.” Levy “will begin this week a series of entertainments to his friends, as he intends having successive parties of visitors throughout the summer.”

Those entertainments continued for the next forty-three years. In the book I chronicle some of the many visits of dignitaries, politicians and others to Monticello during that time. I just learned—while delving into the New York Public Library’s digital archives—that in 1882, Levy invited the former Democratic governor of New York Samuel J. Tilden, to be his guest at Thomas Jefferson’s “Essay in Architecture.”

Six years earlier Tilden had been on the losing end of the bitterly contested and hotly controversial presidential election of 1876. He won the popular vote, but came up one electoral vote short of winning the race because of disputed votes in four states. A special, fifteen-member congressional commission of eight Republicans and seven Democrats was set up to decide the issue. The commission voted along party lines, with Tilden thereby losing the election to Rutherford B. Hayes as a result of an eight-to-seven vote.

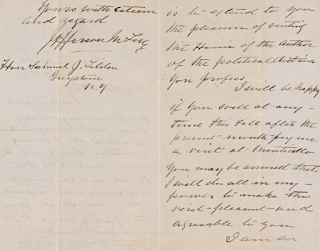

In a letter Levy wrote to Tilden on July 12, 1982 (below), he invited his fellow Democrat, in the name of party unity (and the spirt of Thomas Jefferson), to come South for some R&R.

In the letter, Jefferson Levy alludes to the disputed election, telling Tilden that he was “the choice in 1876 of the people and Democracy….” Then Levy puts in a plug for Jeffersonian Democracy, telling Tilden that his “whole desire is to extend to you the pleasure of visiting the Home of the Author of the political doctrines you profess.” He proposed a visit “any time in the fall.”

Tilden (below) politely declined on December 19. In much clearer handwriting, by the way, he wrote: “It would afford me great delight to see the home of Jefferson, but I have not been able to find an opportunity, and have, reluctantly, given over the hope of doing so during the present season.”

THE CHAPEL IN THE WOODS: I have done more than two hundred talks on Saving Monticellosince it came out early in November of 2001. The one I did on Saturday, September 21, at Kol Ami Congregation in White Plains, New York, turned out to be one of the most memorable.

I was very grateful to Rabbi Shira Milgrom for inviting me to come up to do the talk for that day’s Shabbat Morning Lift, an informal gathering that starts with coffee and bagels and often includes a guest speaker. After the talk the Rabbi leads an “informal and participatory” Shabbat service.

What made this even more special was that Harley Lewis and her late husband Dick thought up the Second Lift concept years ago. As most SM newsletter readers know, Harley Lewis, a great grandniece of Jefferson Levy, kindly provided me with a ton of primary-source material and invaluable advice when I was doing the research for the book in 1999 and 2000. And she has been an enthusiastic supporter of the book and my work ever since.

My wife Janna and I had dinner Friday evening as the guests of one of Harley’s sons, Tom Lewis, and his wife Debbie (in the photo above with Harley and me). They couldn’t have been more welcoming and hospitable. I spoke to Harley on the phone that evening and we made plans to meet after the talk on Saturday.

I was bowled over when Harley arrived during the coffee hour and stayed to take in the talk. I hadn’t seen her since the dedication of the Uriah Levy statue at Congregation Mikve Israel in Philadelphia in 2011, when we both took part in the festivities.

Another special thing about the talk was the venue, the serene and beautiful Chapel in the Woods on the Kol Ami campus. And what made the weekend even more special was that we learned on Saturday that one of Harley’s grandchildren and his wife had her first great-grandchild the day before. The child, descended directly from Uriah Levy’s great grandfather Dr. Samuel Nunez, is a tenth-generation American.

EVENTS: I have four in October, three of them on Saving Monticello:

F Friday, October 4. I will kick off the 22nd Annual Conference on the Art and Command of the Civil War sponsored by the Mosby Heritage Area Association, a local historic preservation group in Middleburg, Virginia, where I live. My talk will be on my only Civl War book, Desperate Engagement, which is about the July 1864 Battle of Monocacy and Confederate Gen. Jubal Early’s subsequent attack on Washington, D.C., the subject of the three-day conference. Some tickets remain. For all the details, go to http://bit.ly/MHAATalk

Friday, October 11. A talk on Saving Monticello at the U.S. Naval Academy’s Commodore Levy Chapel following the 7:00 p.m. Oneg services. The event is free and open to the public, but because of security at the Academy, visitors must register in advance. For info on that, contact the Friends of the Jewish Chapel at the USNA in Annapolis at 410-268-0169, email info@fojcusna.org

Saturday, October 12. A talk on Saving Monticello and book signing at the monthly luncheon meeting of the SAR George Washington Chapter in Alexandria, Virginia.

· Friday, October 25. My third talk of the month on Saving Monticello, as the Keynote Speaker at the annual Southern Jewish Historical Society conference in Charlottesville, Virginia. For info conference, including how to register, go to http://bit.ly/SJHSConf

There’s always the chance that I may have a last-minute talk or signing. For the latest on that, or to check out my scheduled 2019 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, feel free to email me. For info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me at marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Photo credit: Monticello image: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Residence of Thomas Jefferson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1820. http://bit.ly/Montpic

Published on October 05, 2019 10:56

September 4, 2019

September 2019

Saving Monticello: The NewsletterThe latest about the book, author events, and moreNewsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XVI, Number 9 September 1, 2019

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving, never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

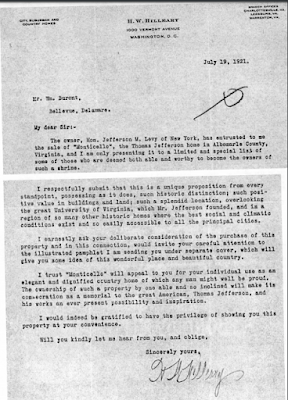

ELEGANT & DIGNIFIED COUNTRY HOME: A couple of weeks ago, as I was working on my next book—a house history of Huntland, a historic country estate in Middleburg, Virginia—I came across the fact that when the place sold in 1927, a Realtor name H.W. Hilleary helped arrange the settlement. That name might ring a bell if you’ve read Saving Monticello. That’s because in 1919, Jefferson Levy chose Hilleary as his real estate broker when he decided to sell Monticello.

Hilleary started marketing Monticello in April 1919 (asking price: $500,000) with newspaper and magazine advertisements and with an elaborate sales brochure. One of the many joys of doing the research for the book came when I sat down at the Monticello research department about twenty years ago with a copy of that brochure.

It’s an old-fashioned, elaborate piece that includes the text of Thomas Jefferson’s first Inaugural Address and an essay on his monumental political career. On the last page Hilleary makes a discreet sales pitch, quoting an “eminent Frenchman”—undoubtedly the Marquis de Lafayette, who paid a visit to Monticello during his 1824-25 Farewell tour.

Monticello, Lafayette said, “is infinitely superior to any of the houses in America from point of taste and convenience and deserves to be ranked with the most pleasant memories of France and England.”In 1919 Hilleary also sent a prospecting letter to upper-crust individuals around the country. It read, in part: “You are familiar, I am sure, with ‘Monticello,’ in the beautiful County of Albemarle, near the University of Virginia…. This historic home, this architectural gem, this most picturesque estate, I have the privilege of offering.

“The present owner, for sentimental and other reasons, has never consented to part with it. I am allowed now to bring it to the attention of those who can appreciate and are able to own a property of such distinction and merit. If interested, I shall be glad to give you detailed information and to quote the authorized price.”

Hilleary sent one of the letters to William Summer Appleton, the founder of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities in Boston, and one to Sidney Fiske Kimball at the Archaeological Institute of America. Kimball, who had taught architecture at the University of Virginia, was nationally recognized as the foremost expert on Thomas Jefferson’s architecture. Kimball and Appleton declined Hilleary’s offer.

Two years later, Hilleary came up with a second, longer marketing letter, which he mailed along with the brochure to potential buyers. He wrote, in part: “I am only presenting [Monticello] to a limited and special list of some of those who are deemed both able and worthy to become the owners of such a shrine.

I respectfully submit that this is a unique proposition from every standpoint, possessing as it does, such historic distinction; such positive value in buildings and land; such a splendid location, overlooking the great University of Virginia, which Mr. Jefferson founded, and in a region of so many other historic homes where the best social and climatic conditions exist and so easily accessible to all the principal cities.

I trust ‘Monticello’ will appeal to you for your individual use as an elegant and dignified country home of which any man might well be proud. The ownership of such a property by one able and so inclined will make its consecration as a memorial to the great American, Thomas Jefferson, and his works an ever present possibility and inspiration. I would indeed be gratified to have the privilege of showing you this property at your convenience.”

In my Huntland research I found a copy of that letter that Hilleary sent on July 21, 1921, to William du Pont, Sr. (1855-1928), a grandson of E.I. du Pont de Nemours, the founder of the world’s largest chemical company. No doubt du Pont was on Hilleary’s list because in 1900 he had purchased Montpelier, the Central Virginia home of another Founding Father, James Madison. William du Pont also owned large estates in Wilmington, Delaware, and near Brunswick, Georgia. A few years ago, I learned that a copy of that letter also went to Thomas S. Walker, a big Minnesota timber baron and one of the wealthiest men in the country.

Here’s a screenshot of a digital copy of the letter that I found in the William de Pont papers, which are housed in the Manuscripts and Archives Department of the Hagley Museum and Library. The Hagley is located in Wilmington, Delaware, along the Brandywine River on a 235-acre site where E.I. du Pont built a gunpowder factory in 1802.

Oddly, the letter is addressed to “Mr. Wm. Buront.” There is no record that Mr. Buront—or Mr. du Pont—replied. Two-and-a-half years later, Hilleary sold Monticello to the newly formed Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, which continues to own and operate Monticello today.

NUMBER 9, NUMBER 9: As I posted on my Facebook page last week, I was very happy (and a bit humbled) to learn that Saving Monticello has just gone into its 9th printing in paperback at the University of Virginia Press. The hardcover (from Free Press at Simon & Schuster) came out in 2001, but went out of print after three printings a few years later. U-Va. Press came out with the paperback in 2003. My thanks to everyone who has supported the book over the years.

EVENTS: I’m still in all-but full-time writing mode for the Huntland book, and have just one event in September.

On Saturday, September 21, I will be doing a “Shabbat Lift” talk on Saving Monticello at follow morning services at Congregation Kol Ami in White Plains, New York. The event is free and open to the public.

I’m particularly excited about this talk because Harley Lewis—Jefferson Levy’s great grandniece who helped me more than anyone as I researched and wrote the book—will be in the audience in this, her synagogue.

For more info, go to http://bit.ly/KolAmiMonticelloor email alisonadler@nykolami.org

There’s always the chance that I may have a last-minute talk or signing. For the latest on that, or to check out my scheduled 2019 events, go to the Events page on my website at http://bit.ly/Eventsandtalks

If you’d like to arrange an event for Saving Monticello, or for any of my other books, feel free to email me. For info on my latest book, Ballad of the Green Beret, go to http://bit.ly/GreenBeretBook

GIFT IDEAS: Want a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello? Please e-mail me at marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover copies, along with a good selection of brand-new copies of my other books.

Published on September 04, 2019 13:00