Tim Hodkinson's Blog, page 5

May 29, 2015

Edward Bruce Festival

Tomorrow is the Edward Bruce festival at Carrickfergus, marking 700 years since Bruce's invasion of Ireland. I'll be in the Castle selling print copies of "Lions of the Grail" and "The Waste Land" so if you are there come along and say hello.

Published on May 29, 2015 03:18

May 15, 2015

On the 700th anniversary of the Scottish Invasion of Ireland

It’s become a trope that Ireland is currently into a “decade of anniversaries”. From Clontarf to the Somme to the Easter Rising, there will be many events to stir up old hatreds, giving us more excuses to pick at old scabs and point accusing fingers at each other. One anniversary that seems to be slipping by relatively unmarked is Edward Bruce’s ill-fated invasion of Ireland, which this May sees the 700th anniversary of.

Perhaps it’s because the whole episode is so messy that we don’t seem to want to remember it. It’s not as black and white as we like things to be. People we would expect to fight for one side appear to have fought for the other. “The English” seems to have typically Irish names. The Scots should have been liberators but seemed to act more like conquerors. The Irish seem to be fighting on both sides. Its all so inconvenient from our modern points of view. There’s nothing in the story we could use to batter the other side with and when we try to shoe-horn it into modern perspectives the realities keep popping out like bunions to disturb our certainties about the past.

On the other hand, it’s a fantastic tale, full of daring exploits, heroism and brutality, chivalry and it even involves a pirate. It was these elements that drew me to the conflict and why I wanted to set my medieval series of novels (Lions of the Grail and the Waste Land) during it. The Waste Land

The Waste Land

As we all know from the movie Braveheart, in 1314 Mel Gibson kicked the English out of Scotland and invented freedom. Sorry I’m getting flippant. In June of 1314, after years of bitter guerrilla war, Robert Bruce won a decisive victory against the English army under Edward II at Bannockburn. What Mel forgot to tell us was the first thing the Scots did on freeing themselves was to invade Ireland. In May of 1315 they landed at Larne in County Antrim, which in those days was called “Wulfrich’s Ford” - an echo of the viking heritage of the place. As an invasion point it makes sense. The sea crossing is so narrow the other island is clearly visible to the naked eye from either shore. Larne forms a natural harbour that until recently was the main port that the ferry to and from Scotland sailed from. The army was probably carried across the sea in birlinns, a form of highland galley not unlike a viking longship. The invasion force was supposedly six thousand strong, organised into two “battles” (a medieval military formation) and consisted of hardy spearmen, veterans of Bannonckburn. It was led by Robert Bruce’s brother Edward, the Earl of Carrick.

Their landing unleashed three years of conflict and devastation across Ireland that left it in ruins for generations. One Gaelic chronicle recounts:

“For in this Bruce's time, for three years and a half, falsehood and famine and homicide filled the country, and undoubtedly men ate each other in Ireland”

Their first target was Carrickfergus, a key strategic castle for the Norman Earldom of Ulster. Awkwardly, the owner of the castle, Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, was Robert Bruce’s father in law. I think facts like this highlight the nature of warfare in medieval times. What we see as titanic struggles between nations at the top level of society was really more akin to deadly family feuds. Much of the nobility of England, Scotland and Ireland were direct descendants of the knights who accompanied William the Conqueror across the English Channel in 1066. Nearly all of them spoke Norman French as their first language. The western edges of the British Isles aside, they were also starting to merge with the remaining Gaelic and Welsh aristocracy and the process by which fils Geralds would become FitzGeralds, De Burghs become Burkes, Le Powers become Powers and de Brus become Bruce was already underway. A 14th Century (possibly Gallowglass) helmet, Ulster Museum

A 14th Century (possibly Gallowglass) helmet, Ulster Museum

It started out well for Edward Bruce. He annihilated the army of Ulster at the battle of Connor (now Kells in Antrim). John Barbour, the biographer of Robert Bruce, recorded the event within living memory of it happening. He paints a vivid and gruesome picture of the battle with the clash of arms, the shouts of men and the screaming of stabbed horses:

“The lords of that country [Ulster], Mandeville, Bysset, and Logan, assembled their men. De Savage also was there. Their whole gathering was well nigh twenty thousand men..Their enemies drew near to battle, and they met them without flinching. Then was to be seen a great melee. Earl Thomas and his host drove so doughtily at their foes, that in a short time a hundred were to be seen lying all bloody. The Irish horses, when they were stabbed, reared and flung, and made great room, and threw their riders. Sir Edward's company then stoutly joined the battle, and all their enemies were driven back. If a man happened to fall in that fight, it was a perilous chance if he rose again. The Scots bore themselves so boldly and well in the encounter that their foes were overwhelmed, and altogether took flight. In that battle were taken or slain the whole flower of Ulster.”

(modern English translation)

The Scots then besieged Carrickfergus castle. However, in a seemginly unbelievable lack of strategic planning, Edward Bruce had not brought any siege engines with him so all he could do was blockade the fortress and wait for starvation to force the garrison into surrender.

Somewhat prematurely, Edward now had himself declared King of Ireland. Domnal Ui Neill (O’Neill), King of Tyrone, Bruce’s main ally throughout the invasion submitted to Edward as King along with twelve other northern Gaelic Kings. A Gaelic chronicle relates how Bruce "took the hostages and lordship of the whole province of Ulster without opposition and they consented to him being proclaimed King of Ireland and all the Gaels of Ireland.” The fact that they had to submit “hostages” is interesting and perhaps a hint at what was to come.

Bruce’s army then pushed south, only to be ambushed outside Newry by the forces of two of those Gaelic kings who had supposedly sworn fealty to him. He defeated them, burned the de Verdun’s fortress at Castle Roche then fell upon the town of Dundalk. When they took the town, they also took several merchant ships which had arrived with a consignment of wine. Soldiers and alcohol is usually an inflammable mix and an orgy of destruction followed. They burned the town to the ground and slaughtered all the inhabitants, both Anglo-Irish and Gaelic alike. Barbour recounts how the streets were slick with the blood of the slain. This indiscriminate drunken massacre set the tone for the rest of the war and perhaps explains the reluctance of the Irish from then on to fully commit to supporting the Scottish army.

War raged up and down the island for the next three years. Even by medieval standards, the Scots behaved appallingly. They burned towns, friaries and farms, pursuing what seems to have been a scorched earth policy. The bitterness left by the indiscriminate nature of their aggression is clear in both Anglo Norman and Gaelic chronicles. Their reasoning for this strategy seems unfathomable, as it seems obvious that there should have been a lot of people in Ireland who should have welcomed them as liberators from the yoke of the English Crown, certainly enough to make victory certain. Yet the actions of the Scottish army clearly alienated them from that source of support. The Kingdon of Tyr Chonnail (modern Donegal) remained steadfastly aloof, refusing to take either side. Other Irish kings actively fought against the Scots.

Equally unclear are the motives for the invasion in the first place. On the face of it, there was much talk of a pan-Gaelic alliance and hands across the Irish sea to free cousins from oppression. “Greater and Lesser Scotia”(Scotland and Ireland) would be united under one king (Edward Bruce) and then join forces with the Welsh against the common English enemy.

On the other hand, Robert Bruce was probably also quietly happy to have his ambitious brother out of the way and fully occupied in Ireland rather than a potential rival in his own newly won Kingdom. Edward Bruce’s own ambitions seem clear: almost as soon as he arrived in Ireland he had himself declared King. A year later he asked the Welsh Kings if they wanted him to become Prince of Wales as well (they turned him down). Ireland had also been providing a supply of grain and warriors to the English Crown in its wars in Scotland. Despite what Mel Gibson wants us to think, while the MacCarthy’s sent a contingent of troops to fought for Bruce at Bannockburn, the majority of the Irish who took part in the Scottish Wars of Independence fought with distinction for the other side, something Bruce probably wanted to put a stop to.

Like all wars, this long forgotten one had many acts of bravery and desperation. For most of the three years of war Edward’s army seemed unbeatable in open battle though he never seemed to be able to win complete victory. Sir Thomas de Mandeville launched a desperate seaboarne assault to try to break the siege of Carrickfergus castle. On the Scottish side Sir Neil Flemming, his small force completely outnumbered stayed in the town to fight the raiders until the rest of the Scottish army was mustered.Both men lost their lives in the street fighting. The O’Dempsey clan, supposed allies, lead Bruce’s army southward into a carefully laid ambush. They diverted a river into the Scottish camp and attacked them, drowning or killing two hundred men. The clans of the Glens of Antrim killed four hundred of the Scottish army in hit and run attacks. When faced with the approach of the Scottish army, the citizens of Dublin destroyed half their own city, tearing down all the buildings north of the river to leave no cover for the advancing enemy and using the recovered stones to shore up the city walls. The savagery of the conflict is perhaps best personified by an incident that happened in Carrickfergus in June of 1316. A year after the war began, the castle was still under siege. The starving garrison said they wanted to surrender and a Scottish delegation went to the castle gate to receive their capitulation. Instead of surrendering, the garrison rushed out, seized nine of the Scots and pulled them inside the castle. They later ate them.

Incredibly, all this happened during the one of the worst famine in European history. Sudden climate change in 1315 caused widespread crop failures across the continent and continual rain caused stored fodder to rot. The price of grain rose rapidly and people began to die in great numbers. Weakened by hunger, disease took a further toll on the population and combined with the ongoing war it must have seemed like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse had come. An English poem from 1321, “on the Evil Times of Edward II”, said: “Whii werre and wrake in londe and manslauht is i-come,Whii hunger and derthe on eorthe the pore hath undernome,Whii bestes ben thus storve, whii corn hath ben so dere,

“Why war, destruction and murder has come to the land,Why hunger and famine have seized the poor,Why animals starve, why corn is so dear,

Danse Macabre

Danse Macabre

Forced to live off the land and feed his army by taking what little food there was from the indigenous population, this must have deepened the unpopularity of Edward Bruce’s army and led even more to the perception of them as an occupying force that one of liberation.

A BBC article on the war recently described Bruce’s Irish adventure as “Medieval Scotland’s Vietnam” and the analogy is probably a good one. Personally I believe a lot of blame lies on the shoulders of Edward Bruce himself. Although one chronicler described him as “brave as a leopard” (ironically the same animal that in his day was used as the nickname for another Edward, Edward I of England, the infamous “Longshanks”, Hammer of the Scots) from what can be discerned from the chronicles, Edward seems to have lacked all the qualities that made his brother Robert great. Vengeful, seemingly pitiless, impetuous and headstrong, these traits seems to have governed Edward’s personality. Although a successful commander of one of the battalions at Bannockburn, as a general he was was failure. Robert had to cross the Irish Sea not once but twice to bail him out of trouble. In the end, in 1317, when the famine eased he pushed for Dublin again. His brother was due to arrive again with much need re-enforcements but the Annals of Clonmacnoise record that Edward was “anxious to obtain the victory for himself”. The army of the Lordship of Ireland were waiting for him at Faughart in Louth, not far from Dundalk, the scene of his earlier crimes. Edward and the Scots charged headlong at the enemy. Tellingly, his Irish allies decided not to join him and instead stood back to watch what happened. The Scottish army was destroyed, several Scottish clan chiefs died and Edward Bruce himself was killed and dismembered, his body parts being sent to the four corners of the island for display. His former Irish allies quietly left.

The final word should probably go to the Gaelic chronicler who recorded the battle of Faughart.“Edward de Brus, the destroyer of Ireland in general, both Galls and Gaels, was killed .... And there was not done from the beginning of the world a deed that was better for the Men of Ireland than that deed”

In a way, if the intent was to oust the English from Ireland, Bruce’s invasion partly succeeded. Within a generation the Norman Earldom of Ulster, weakened by war, famine then the Black Death, dissolved into terminal internecine struggle and collapse.

I began this by saying that this anniversary is hardly being marked. There will be one place however where it will. At the end of this month (30th and 31st may), there will be an Edward Bruce Festival in Carickfergus. The festival will take place at Carrickfergus Castle, Main Street and Marine Gardens. There will be a range of medieval events and entertainment including jousting, dramatic re-enactments, street theatre, falconry, traditional storytelling, blacksmith demonstrations, archery, medieval battle workshops and family entertainment. The Knights of Royal England (the premiere jousting company in Europe) will be conducting a jousting tournament on Saturday 30th May at Marine Gardens. The organisers also have kindly let me take part and I’ll be in castle keep, on Saturday 30th. Please feel free to stop by and say hello.

Perhaps it’s because the whole episode is so messy that we don’t seem to want to remember it. It’s not as black and white as we like things to be. People we would expect to fight for one side appear to have fought for the other. “The English” seems to have typically Irish names. The Scots should have been liberators but seemed to act more like conquerors. The Irish seem to be fighting on both sides. Its all so inconvenient from our modern points of view. There’s nothing in the story we could use to batter the other side with and when we try to shoe-horn it into modern perspectives the realities keep popping out like bunions to disturb our certainties about the past.

On the other hand, it’s a fantastic tale, full of daring exploits, heroism and brutality, chivalry and it even involves a pirate. It was these elements that drew me to the conflict and why I wanted to set my medieval series of novels (Lions of the Grail and the Waste Land) during it.

The Waste Land

The Waste LandAs we all know from the movie Braveheart, in 1314 Mel Gibson kicked the English out of Scotland and invented freedom. Sorry I’m getting flippant. In June of 1314, after years of bitter guerrilla war, Robert Bruce won a decisive victory against the English army under Edward II at Bannockburn. What Mel forgot to tell us was the first thing the Scots did on freeing themselves was to invade Ireland. In May of 1315 they landed at Larne in County Antrim, which in those days was called “Wulfrich’s Ford” - an echo of the viking heritage of the place. As an invasion point it makes sense. The sea crossing is so narrow the other island is clearly visible to the naked eye from either shore. Larne forms a natural harbour that until recently was the main port that the ferry to and from Scotland sailed from. The army was probably carried across the sea in birlinns, a form of highland galley not unlike a viking longship. The invasion force was supposedly six thousand strong, organised into two “battles” (a medieval military formation) and consisted of hardy spearmen, veterans of Bannonckburn. It was led by Robert Bruce’s brother Edward, the Earl of Carrick.

Their landing unleashed three years of conflict and devastation across Ireland that left it in ruins for generations. One Gaelic chronicle recounts:

“For in this Bruce's time, for three years and a half, falsehood and famine and homicide filled the country, and undoubtedly men ate each other in Ireland”

Their first target was Carrickfergus, a key strategic castle for the Norman Earldom of Ulster. Awkwardly, the owner of the castle, Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, was Robert Bruce’s father in law. I think facts like this highlight the nature of warfare in medieval times. What we see as titanic struggles between nations at the top level of society was really more akin to deadly family feuds. Much of the nobility of England, Scotland and Ireland were direct descendants of the knights who accompanied William the Conqueror across the English Channel in 1066. Nearly all of them spoke Norman French as their first language. The western edges of the British Isles aside, they were also starting to merge with the remaining Gaelic and Welsh aristocracy and the process by which fils Geralds would become FitzGeralds, De Burghs become Burkes, Le Powers become Powers and de Brus become Bruce was already underway.

A 14th Century (possibly Gallowglass) helmet, Ulster Museum

A 14th Century (possibly Gallowglass) helmet, Ulster MuseumIt started out well for Edward Bruce. He annihilated the army of Ulster at the battle of Connor (now Kells in Antrim). John Barbour, the biographer of Robert Bruce, recorded the event within living memory of it happening. He paints a vivid and gruesome picture of the battle with the clash of arms, the shouts of men and the screaming of stabbed horses:

“The lords of that country [Ulster], Mandeville, Bysset, and Logan, assembled their men. De Savage also was there. Their whole gathering was well nigh twenty thousand men..Their enemies drew near to battle, and they met them without flinching. Then was to be seen a great melee. Earl Thomas and his host drove so doughtily at their foes, that in a short time a hundred were to be seen lying all bloody. The Irish horses, when they were stabbed, reared and flung, and made great room, and threw their riders. Sir Edward's company then stoutly joined the battle, and all their enemies were driven back. If a man happened to fall in that fight, it was a perilous chance if he rose again. The Scots bore themselves so boldly and well in the encounter that their foes were overwhelmed, and altogether took flight. In that battle were taken or slain the whole flower of Ulster.”

(modern English translation)

The Scots then besieged Carrickfergus castle. However, in a seemginly unbelievable lack of strategic planning, Edward Bruce had not brought any siege engines with him so all he could do was blockade the fortress and wait for starvation to force the garrison into surrender.

Somewhat prematurely, Edward now had himself declared King of Ireland. Domnal Ui Neill (O’Neill), King of Tyrone, Bruce’s main ally throughout the invasion submitted to Edward as King along with twelve other northern Gaelic Kings. A Gaelic chronicle relates how Bruce "took the hostages and lordship of the whole province of Ulster without opposition and they consented to him being proclaimed King of Ireland and all the Gaels of Ireland.” The fact that they had to submit “hostages” is interesting and perhaps a hint at what was to come.

Bruce’s army then pushed south, only to be ambushed outside Newry by the forces of two of those Gaelic kings who had supposedly sworn fealty to him. He defeated them, burned the de Verdun’s fortress at Castle Roche then fell upon the town of Dundalk. When they took the town, they also took several merchant ships which had arrived with a consignment of wine. Soldiers and alcohol is usually an inflammable mix and an orgy of destruction followed. They burned the town to the ground and slaughtered all the inhabitants, both Anglo-Irish and Gaelic alike. Barbour recounts how the streets were slick with the blood of the slain. This indiscriminate drunken massacre set the tone for the rest of the war and perhaps explains the reluctance of the Irish from then on to fully commit to supporting the Scottish army.

War raged up and down the island for the next three years. Even by medieval standards, the Scots behaved appallingly. They burned towns, friaries and farms, pursuing what seems to have been a scorched earth policy. The bitterness left by the indiscriminate nature of their aggression is clear in both Anglo Norman and Gaelic chronicles. Their reasoning for this strategy seems unfathomable, as it seems obvious that there should have been a lot of people in Ireland who should have welcomed them as liberators from the yoke of the English Crown, certainly enough to make victory certain. Yet the actions of the Scottish army clearly alienated them from that source of support. The Kingdon of Tyr Chonnail (modern Donegal) remained steadfastly aloof, refusing to take either side. Other Irish kings actively fought against the Scots.

Equally unclear are the motives for the invasion in the first place. On the face of it, there was much talk of a pan-Gaelic alliance and hands across the Irish sea to free cousins from oppression. “Greater and Lesser Scotia”(Scotland and Ireland) would be united under one king (Edward Bruce) and then join forces with the Welsh against the common English enemy.

On the other hand, Robert Bruce was probably also quietly happy to have his ambitious brother out of the way and fully occupied in Ireland rather than a potential rival in his own newly won Kingdom. Edward Bruce’s own ambitions seem clear: almost as soon as he arrived in Ireland he had himself declared King. A year later he asked the Welsh Kings if they wanted him to become Prince of Wales as well (they turned him down). Ireland had also been providing a supply of grain and warriors to the English Crown in its wars in Scotland. Despite what Mel Gibson wants us to think, while the MacCarthy’s sent a contingent of troops to fought for Bruce at Bannockburn, the majority of the Irish who took part in the Scottish Wars of Independence fought with distinction for the other side, something Bruce probably wanted to put a stop to.

Like all wars, this long forgotten one had many acts of bravery and desperation. For most of the three years of war Edward’s army seemed unbeatable in open battle though he never seemed to be able to win complete victory. Sir Thomas de Mandeville launched a desperate seaboarne assault to try to break the siege of Carrickfergus castle. On the Scottish side Sir Neil Flemming, his small force completely outnumbered stayed in the town to fight the raiders until the rest of the Scottish army was mustered.Both men lost their lives in the street fighting. The O’Dempsey clan, supposed allies, lead Bruce’s army southward into a carefully laid ambush. They diverted a river into the Scottish camp and attacked them, drowning or killing two hundred men. The clans of the Glens of Antrim killed four hundred of the Scottish army in hit and run attacks. When faced with the approach of the Scottish army, the citizens of Dublin destroyed half their own city, tearing down all the buildings north of the river to leave no cover for the advancing enemy and using the recovered stones to shore up the city walls. The savagery of the conflict is perhaps best personified by an incident that happened in Carrickfergus in June of 1316. A year after the war began, the castle was still under siege. The starving garrison said they wanted to surrender and a Scottish delegation went to the castle gate to receive their capitulation. Instead of surrendering, the garrison rushed out, seized nine of the Scots and pulled them inside the castle. They later ate them.

Incredibly, all this happened during the one of the worst famine in European history. Sudden climate change in 1315 caused widespread crop failures across the continent and continual rain caused stored fodder to rot. The price of grain rose rapidly and people began to die in great numbers. Weakened by hunger, disease took a further toll on the population and combined with the ongoing war it must have seemed like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse had come. An English poem from 1321, “on the Evil Times of Edward II”, said: “Whii werre and wrake in londe and manslauht is i-come,Whii hunger and derthe on eorthe the pore hath undernome,Whii bestes ben thus storve, whii corn hath ben so dere,

“Why war, destruction and murder has come to the land,Why hunger and famine have seized the poor,Why animals starve, why corn is so dear,

Danse Macabre

Danse MacabreForced to live off the land and feed his army by taking what little food there was from the indigenous population, this must have deepened the unpopularity of Edward Bruce’s army and led even more to the perception of them as an occupying force that one of liberation.

A BBC article on the war recently described Bruce’s Irish adventure as “Medieval Scotland’s Vietnam” and the analogy is probably a good one. Personally I believe a lot of blame lies on the shoulders of Edward Bruce himself. Although one chronicler described him as “brave as a leopard” (ironically the same animal that in his day was used as the nickname for another Edward, Edward I of England, the infamous “Longshanks”, Hammer of the Scots) from what can be discerned from the chronicles, Edward seems to have lacked all the qualities that made his brother Robert great. Vengeful, seemingly pitiless, impetuous and headstrong, these traits seems to have governed Edward’s personality. Although a successful commander of one of the battalions at Bannockburn, as a general he was was failure. Robert had to cross the Irish Sea not once but twice to bail him out of trouble. In the end, in 1317, when the famine eased he pushed for Dublin again. His brother was due to arrive again with much need re-enforcements but the Annals of Clonmacnoise record that Edward was “anxious to obtain the victory for himself”. The army of the Lordship of Ireland were waiting for him at Faughart in Louth, not far from Dundalk, the scene of his earlier crimes. Edward and the Scots charged headlong at the enemy. Tellingly, his Irish allies decided not to join him and instead stood back to watch what happened. The Scottish army was destroyed, several Scottish clan chiefs died and Edward Bruce himself was killed and dismembered, his body parts being sent to the four corners of the island for display. His former Irish allies quietly left.

The final word should probably go to the Gaelic chronicler who recorded the battle of Faughart.“Edward de Brus, the destroyer of Ireland in general, both Galls and Gaels, was killed .... And there was not done from the beginning of the world a deed that was better for the Men of Ireland than that deed”

In a way, if the intent was to oust the English from Ireland, Bruce’s invasion partly succeeded. Within a generation the Norman Earldom of Ulster, weakened by war, famine then the Black Death, dissolved into terminal internecine struggle and collapse.

I began this by saying that this anniversary is hardly being marked. There will be one place however where it will. At the end of this month (30th and 31st may), there will be an Edward Bruce Festival in Carickfergus. The festival will take place at Carrickfergus Castle, Main Street and Marine Gardens. There will be a range of medieval events and entertainment including jousting, dramatic re-enactments, street theatre, falconry, traditional storytelling, blacksmith demonstrations, archery, medieval battle workshops and family entertainment. The Knights of Royal England (the premiere jousting company in Europe) will be conducting a jousting tournament on Saturday 30th May at Marine Gardens. The organisers also have kindly let me take part and I’ll be in castle keep, on Saturday 30th. Please feel free to stop by and say hello.

Published on May 15, 2015 04:08

May 14, 2015

Portrush Heritage Society talk

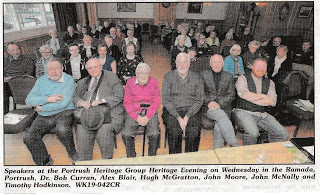

The good folks at Portrush Heritage Society invited me to speak at their last meeting. It was a tremendous evening which I thoroughly enjoyed. It was great to meet a bunch of people who are so passionate about preserving the fragile archaeological, historical and cultural heritage of the north coast and who stand by their convictions, sometimes in the face of short term commercial interests.

As well as me, Alex Blair delivered an fascinating talk on local dialect and the influences of Gaelic, Scots and Elizabethan English on the words, idioms, pronunciation and cadences of the version of English that Ulster people speak today. Also there was the new Mayor, who turned out to be both a "Knight" and a "McQuillan" so she could not have been a more appropriate guest in light of the characters of my book Lions of the Grail.

Here are some pictures of the evening and the write up from the Coleraine Chronicle. That's me on the right of the front row

As well as me, Alex Blair delivered an fascinating talk on local dialect and the influences of Gaelic, Scots and Elizabethan English on the words, idioms, pronunciation and cadences of the version of English that Ulster people speak today. Also there was the new Mayor, who turned out to be both a "Knight" and a "McQuillan" so she could not have been a more appropriate guest in light of the characters of my book Lions of the Grail.

Here are some pictures of the evening and the write up from the Coleraine Chronicle. That's me on the right of the front row

Published on May 14, 2015 02:33

April 14, 2015

book review - "Holy Spy" by Rory Clements

Holy Spy by Rory Clements

Holy Spy by Rory ClementsMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

This is an intriguing tale based around two plots - one by English Catholics to kill Queen Elizabeth and put her cousin Mary on the throne and the counter plot by the early English intelligence agencies to stop (or is provoke?) it. Woven into it all are historical personages, Elizabethan gangsters and a murder mystery where the main suspect is a former love of the hero. There is much to enjoy - Fans of spy novels will enjoy the complexity of the plots/counter plots and double dealing. There is corruption in high places, murder, torture and the fast paced action takes place against the backdrop of late 16th Century London in all its filth and glory.

This is the first John Shakespeare book I've read and I'm delighted to find that its part of a series so I'll look for more.

View all my reviews

Published on April 14, 2015 01:48

December 7, 2014

Duneight Motte and Bailey

Believe it or not, this is a castle. Well, a proto-castle. When the Normans conquered England in 1066, they threw up earth and wood forts that could be used to garrison soldiers or a place of refuge if things went wrong. They were largely the same design: a high mound -a motte-with a circular palisade on top. There was also a connected, rectangular area - the bailey- near the foot of the mound, also palisaded but for everyday living. Its reckoned that fifty men could put up a motte in a month and The bayeux tapestry shows that the Normans brought pre-fabricated components for these forts on the ships that crossed the English channel to invade in 1066. As time went by the wooden defences were replaced by stone, and the motte and bailey forts evolved into the medieval castle.

One hundred years after 1066, when they invaded Ireland, the now Anglo-Normans took the same warfare architecture with them. These pictures are of Duneight Motte and Bailey, near Lisburn in Co. Down. The mound is still steep (I slipped and fell on my mouth and nose going up it yesterday, much to the delight of my kids) and the fall on the river side is precipitous and would have presented a formidable obstacle to any attacker. The entranceway seems to be through a curving ditch that would have been guarded on both sides by wooden battlements above, channeling any potential aggressor approaching the gate into a narrow killing channel. Its pretty much exactly like the entrance to Krak des Chavaliers, except made of mud and wood, and on considerably smaller scale :-).

Now this is a castle

Now this is a castle

Built on the site of a former fort of the Ulaidh (the tribe who gave Ulster its name), the fort guarded what was then the main road to Dublin, but is now just a sleepy little bend in a river in the countryside. Unusually for an Irish motte, Duneight has a bailey, which you can see in the pictures as the lower, long flat mound. For some reason, most Irish mottes do not have baileys so Duneight is unusual. The reason for this in unknown. In England by the late 12th century, motte and baileys had become increasingly rare, but some of the Irish mottes were still in use into the early 14th century. They never transformed into stone castles, possibly because the English Earldom of Ulster was extinguished around then.

So this was once the home of a baron of Ulster. You have to wonder what his cousins and peers in England with their baronial halls and stone castles would have made of his rather more humble dwelling.

Artist's impression of the original castle

Artist's impression of the original castle

Published on December 07, 2014 02:51

October 12, 2014

"True Grit" the novel, a review

True Grit by Charles Portis

True Grit by Charles PortisMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

I gave this book 5 stars because I simply haven’t enjoyed reading a novel as much as this one in a long time. Most people will be familiar with the story from the epic John Wayne movie and those with a childhood in the 1970s probably remember it being on TV pretty much every Christmas. However, while the film tells the same story what is missing, what can only be got from reading the book (and what is probably the unique value of this tale) is how it is told.

The plot is a quest for revenge. A “miserable scoundrel” shoots an upstanding member of the frontier Arkansas community and in a world of crooked lawyers and uncaring judges, his fourteen year old daughter takes it on herself to see that justice is done. It is she who narrates the tale and we see everything through her eyes. Headstrong, independent and single minded, Mattie Ross represents a certain character of frontier woman, the sort for whom the world is black and white and the moral ambiguities that plague many don’t get in her way. At one point late in the narrative, looking back as an old woman, she comments that many folk say her only loves are “her bank account and the Presbyterian Church” and that is about the depths of her introspection which perhaps gives a good idea of her character. Anyone coming from a Scots-Irish background will probably recognise her character straight away.

It is her single-minded, unquestioning pursuit of justice that drives the plot and leads her to team up with a Texas ranger called LeBeof and the inimitable Rooster Cogburn, a US Marshal every bit as much of a rogue as the outlaws they chase. It is natural justice, regardless of what the law thinks, that Mattie seeks and what Cogburn recognizes and responds to. An immature, at times unsympathetic character - she shoots a man in the head at one point and the reader is left with little doubt that the deed ever troubled her sleep - having the story told through her eyes reminded me of another classic of naive narration, Good Behaviour by Molly Keane.

All in all, the book is an excellent portrayal of the hard life on the frontier of the United States in the last century and the sort of personalities it took to forge that nation. Not always heroic, noble or pushed by high minded ideals, it was the Mattie Rosses and the Rooster Cogburns who probably did as much to build the West as the Lincolns.

View all my reviews

Published on October 12, 2014 08:10

September 18, 2014

The battle of Moira and the origins of Scotland

As Scotland ponders its future with or without the rest of the UK, I was taking a walk around the village I live in and it occurred to me that this was the very spot where (arguably) we all first came together in the proto-guises of our current national identities. Naturally it was for a fight.

Today Moira is the sleepy Northern Irish village I live in, right on the edge of Counties Armagh and Down. It was once blown to bits by the IRA but apart from that nothing much has happened here recently. However, Moira was once the scene of considerable slaughter. The battle of Moira occurred in 637 AD. It was a bloody affair and notable enough that it was reported not just in the Irish annals but also in the Anglo-Saxon chronicle and also in a particularly fine painting by the artist Jim Fitzpatrick:

The reason for its widespread fame was not just the level of carnage but the participants. On one side there was an army from the South, led by an O’Neil who was High King of Ireland. Against them stood a coalition of forces led by a King of Ulster but comprising warriors and princes from the north of Ireland and what is now Scotland, as well as a contingent of Anglo-Saxons and even a few Welshmen (well, Britons).

This possibly comes as a surprise to some. Surely our incessant wars began 800 years ago with the arrival of the English (or rather the Normans), not 1377 years ago when we all lived in a misty poetic utopia? With that in mind we should take a further look at the combatants.

Congal had been High King of Ireland, but an accident involving a bee sting resulted in him being blinded in one eye. No longer physically perfect, this meant he could no longer hold the High-Kingship which even in the Christian-era had sacred connotations. Like a lot of modern Ulstermen would have done, he sued the owners of the bees for compensation (the ancient law tract still survives). However he was to say the least “put out” by the affair. Before long he was at war with his successor (and foster father), Domnall mac Áedo of the Clan Connell who took his place as High King. They met in battle in 629 at the Battle of Dún Ceithirn and Congal lost. Having nowhere left to go in Ireland he fled across the sea to his cousins in Scotland.

Roman writers and Geographers placed the tribe called the Scots as living in Ireland. Similarly, Saint Patrick’s writings in the 5th and 6th centuries place the Scots in the north of Ireland. By the 7th century, however, the northern Irish kingdom of Dalriada had spread itself from its original powerbase in North Antrim across the sea to the islands and shores of western Scotland, taking their language and culture along with them. It was among these folks that Congal, still King of Ulster, took refuge and brooded on his revenge.

Eventually he came back and claimed his throne again. War inevitably followed and conflict raged across Ireland for several until Domnall once more marched north, determined to rid himself of his disgruntled rival once as for all. Hopelessly outnumbered but the advancing army form the south, Congal called on his friends and relatives overseas and an army came to his side. The politics of North Britain were such at the time that the Dal Riadan prince (also called Domnall) could call on allies from neighbouring kingdoms too so along came some British princes from the Brythonic tribes of the Old North (in Welsh, Hen Ogledd), possibly the Gododinn or Ystrad Clud ). Theses were the rump of ancient British kingdoms who had not yet succumbed to the Anglo-Saxons invading from the south. These men spoke an ancient version of the Welsh language. Amazingly, given that all these folks were fighting for the same pieces of land in what is now Scotland, a contingent of Anglo-Saxons came along too. One of this crowd brought along a cavalry cohort, which raises intriguing possible connections to a son or grandson of one of the historical figures (Artuir mac Aedan) identified as a candidate for the inspiration of the legend of King Arthur, recently outlined by David Pillings here: http://pillingswritingcorner.blogspot.co.uk/2014/09/real-arthurs.html . As we will see, this is not the only Arthurian connection to the battle.

As always in Ireland, there seems to have been a religious element to the whole affair. Domnall's army included a Christian Saint in its ranks, Ronan Finn. Ancient accounts of the battle of Moira mention kings among the Ulster army who are pagans. The ancient poems about the battle abound with pagan celtic spirits and omens. Old Gods like Mannan MacLir and the Morrígan, the celtic battle goddess, make appearances. This is an interesting point. The battle was taking place 200 years after Saint Patrick had supposedly made Ireland Christian and 74 years after Saint Columba had founded Iona, yet supposedly parts of the north still followed the old ways.

Readers of Irish legend, Seamus Heaney, Flann O’Brien, Joseph Heller and Neil Giaman’s “American Gods” will be familiar with the character of “Mad Sweeney” , a pagan Dalriadan King who is driven insane in the heart of battle and goes and spends the rest of his days living in the woods thinking he is a bird until he eventually suffers a threefold death. Arthurian and Welsh scholars will see direct parallels with the story of Merlin and the Battle of Arfderydd . I will no doubt return to this subject in a future post. Suffice to say, the battle where Sweeney went mad was Moira. By co-incidence there are still a few with the Sweeney surname in and around Moira and Lisburn. Whether they are related or not I can’t say.

After several days of heavy fighting Congal was killed and his army was defeated. The result was that Domnall and the O’Neils extended their influence over the north, which they ruled for the next 1000 years until the Flight of the Earls in 1607. The Dal Riadans lost their remaining Irish lands and from then on their energies were focused in north Britain in the foundation of the fledgling Kingdom that eventually became Scotland.

Moira still bears some echoes of the battle. In the 1830s a newspaper report mentioned the finding of large numbers of human and horse bones during the construction of the railway line near Killultagh. A similar account mentions another vast quantity of human bones being found near the Lime Kilns on Claire Hill. There are old townland names within the village that point to further clues: Carnalbanagh translates as “Grave (Cairn) of the Scots” - or rather “Of those from Alba”, the old name for Britain. Beside it is Aughnafosker, usually translated as “field of slaughter”. Moira itself means “Plain of the raths (ancient ringforts)” and at one time there were many of those in the area. Unfortunately most of them have been destroyed by over-zealous farmers and property developers.A few survive, like the one in the middle of the roundabout:

Or the huge Pretty Mary's Fort, the ramparts of which are still impressive:

Aughnafosker is mostly covered by the housing development in which I live and last week work began on covering the final green field part of it beneath 70 new houses.

Can anyone lend me a metal detector?

Today Moira is the sleepy Northern Irish village I live in, right on the edge of Counties Armagh and Down. It was once blown to bits by the IRA but apart from that nothing much has happened here recently. However, Moira was once the scene of considerable slaughter. The battle of Moira occurred in 637 AD. It was a bloody affair and notable enough that it was reported not just in the Irish annals but also in the Anglo-Saxon chronicle and also in a particularly fine painting by the artist Jim Fitzpatrick:

The reason for its widespread fame was not just the level of carnage but the participants. On one side there was an army from the South, led by an O’Neil who was High King of Ireland. Against them stood a coalition of forces led by a King of Ulster but comprising warriors and princes from the north of Ireland and what is now Scotland, as well as a contingent of Anglo-Saxons and even a few Welshmen (well, Britons).

This possibly comes as a surprise to some. Surely our incessant wars began 800 years ago with the arrival of the English (or rather the Normans), not 1377 years ago when we all lived in a misty poetic utopia? With that in mind we should take a further look at the combatants.

Congal had been High King of Ireland, but an accident involving a bee sting resulted in him being blinded in one eye. No longer physically perfect, this meant he could no longer hold the High-Kingship which even in the Christian-era had sacred connotations. Like a lot of modern Ulstermen would have done, he sued the owners of the bees for compensation (the ancient law tract still survives). However he was to say the least “put out” by the affair. Before long he was at war with his successor (and foster father), Domnall mac Áedo of the Clan Connell who took his place as High King. They met in battle in 629 at the Battle of Dún Ceithirn and Congal lost. Having nowhere left to go in Ireland he fled across the sea to his cousins in Scotland.

Roman writers and Geographers placed the tribe called the Scots as living in Ireland. Similarly, Saint Patrick’s writings in the 5th and 6th centuries place the Scots in the north of Ireland. By the 7th century, however, the northern Irish kingdom of Dalriada had spread itself from its original powerbase in North Antrim across the sea to the islands and shores of western Scotland, taking their language and culture along with them. It was among these folks that Congal, still King of Ulster, took refuge and brooded on his revenge.

Eventually he came back and claimed his throne again. War inevitably followed and conflict raged across Ireland for several until Domnall once more marched north, determined to rid himself of his disgruntled rival once as for all. Hopelessly outnumbered but the advancing army form the south, Congal called on his friends and relatives overseas and an army came to his side. The politics of North Britain were such at the time that the Dal Riadan prince (also called Domnall) could call on allies from neighbouring kingdoms too so along came some British princes from the Brythonic tribes of the Old North (in Welsh, Hen Ogledd), possibly the Gododinn or Ystrad Clud ). Theses were the rump of ancient British kingdoms who had not yet succumbed to the Anglo-Saxons invading from the south. These men spoke an ancient version of the Welsh language. Amazingly, given that all these folks were fighting for the same pieces of land in what is now Scotland, a contingent of Anglo-Saxons came along too. One of this crowd brought along a cavalry cohort, which raises intriguing possible connections to a son or grandson of one of the historical figures (Artuir mac Aedan) identified as a candidate for the inspiration of the legend of King Arthur, recently outlined by David Pillings here: http://pillingswritingcorner.blogspot.co.uk/2014/09/real-arthurs.html . As we will see, this is not the only Arthurian connection to the battle.

As always in Ireland, there seems to have been a religious element to the whole affair. Domnall's army included a Christian Saint in its ranks, Ronan Finn. Ancient accounts of the battle of Moira mention kings among the Ulster army who are pagans. The ancient poems about the battle abound with pagan celtic spirits and omens. Old Gods like Mannan MacLir and the Morrígan, the celtic battle goddess, make appearances. This is an interesting point. The battle was taking place 200 years after Saint Patrick had supposedly made Ireland Christian and 74 years after Saint Columba had founded Iona, yet supposedly parts of the north still followed the old ways.

Readers of Irish legend, Seamus Heaney, Flann O’Brien, Joseph Heller and Neil Giaman’s “American Gods” will be familiar with the character of “Mad Sweeney” , a pagan Dalriadan King who is driven insane in the heart of battle and goes and spends the rest of his days living in the woods thinking he is a bird until he eventually suffers a threefold death. Arthurian and Welsh scholars will see direct parallels with the story of Merlin and the Battle of Arfderydd . I will no doubt return to this subject in a future post. Suffice to say, the battle where Sweeney went mad was Moira. By co-incidence there are still a few with the Sweeney surname in and around Moira and Lisburn. Whether they are related or not I can’t say.

After several days of heavy fighting Congal was killed and his army was defeated. The result was that Domnall and the O’Neils extended their influence over the north, which they ruled for the next 1000 years until the Flight of the Earls in 1607. The Dal Riadans lost their remaining Irish lands and from then on their energies were focused in north Britain in the foundation of the fledgling Kingdom that eventually became Scotland.

Moira still bears some echoes of the battle. In the 1830s a newspaper report mentioned the finding of large numbers of human and horse bones during the construction of the railway line near Killultagh. A similar account mentions another vast quantity of human bones being found near the Lime Kilns on Claire Hill. There are old townland names within the village that point to further clues: Carnalbanagh translates as “Grave (Cairn) of the Scots” - or rather “Of those from Alba”, the old name for Britain. Beside it is Aughnafosker, usually translated as “field of slaughter”. Moira itself means “Plain of the raths (ancient ringforts)” and at one time there were many of those in the area. Unfortunately most of them have been destroyed by over-zealous farmers and property developers.A few survive, like the one in the middle of the roundabout:

Or the huge Pretty Mary's Fort, the ramparts of which are still impressive:

Aughnafosker is mostly covered by the housing development in which I live and last week work began on covering the final green field part of it beneath 70 new houses.

Can anyone lend me a metal detector?

Published on September 18, 2014 08:03

August 19, 2014

The Holy Gail and a dark age armageddon

It's taken some time but I've finally got round to writing about the Grail.

Recently, an article appeared in the press about how British Police raided a pub in search of the Holy Grail: While the article is slightly weird, it proves the on-going fascination with the topic of the Grail. Obviously I share this fascination as the Quest for the Grail was the engine that drove my first novel, Lions of the Grail and, as the titles suggest, it was a theme that continued through the recently released sequel, The Waste Land and will persist through the third book in the series, tentatively titled “The Fisher King”.

The mystery of what the nature of the Grail actually is, issomething that fuels people’s fascination. It is generally described as a cup - the cup that was used at the Last Supper and also sometimes the cup used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch the blood of Christ as it flowed down from the cross. However over the centuries it has also been described as a cauldron, a plate with a severed head on it and, perhaps most odd, a stone that fell from the sky. Its the gloriously vague nature of the tales of the Grail combined with their multiple authours and the several strands of tradition -both Christian and Pagan- that have been entwined in their creation that have allowed all these interpretations to not just be created, but actually be plausible. I returned to this topic recently while I was re-reading Parzifal, the medieval German romance written by Wolfram von Eschenbach in the 13th century. While going through it I began to think that there may be more to the “Stone from the sky” interpretation than meets the eye, and in fact it may even be an echo of an actual, catastrophic event that happened in the 5th Century.

We are familiar, if a little uncomfortable, with the concept that every so often something hurtles out of deep space and smashes into the earth, wiping out large quantities of life causing massive devastation. It is the current popular theory, for example, of what killed off the dinosaurs.A few years ago Professor Mike Baillie of Queens University of Belfast appeared on a Channel 4 TV series which detailed the effects of a cosmic impact in the mid 6th century AD. The basic theory was that a large object, probably a comet or a asteroid had struck the earth in the Northern hemisphere sometime around 536 AD, throwing so much dust and debris into the air that it caused what we would refer to as a "nuclear winter".His theory is outlined in this article

Through tree ring dating and historical references he showed how over a period of several years vegetation had grown at a stunted rate leading to famine and disease throughout Northern Europe.This reminded me of the tales of King Arthur, particularly those surrounding the Quest for the Holy Grail. As most of those familiar with the tale will know, one of the roots of the Quest is the striking (unwittingly by Sir Balin) of the "Dolorous Blow", a fateful stroke that maims the Fisher King through the thighs, making him infertile and therefore destroying the fertility of the land, thus turning the kingdom into the "Waste Land". As Thomas Malory put it in his Le Morte d'Arthur: "and through that stroke three kingdoms shall be in great poverty, misery and wretchedness twelve years". Medieval peasants struggling in mud

Medieval peasants struggling in mud

It is only the finding of the Grail that can heal the Waste Land. What if the folk memory of the cosmic impact had become mythologised into the legend of the Waste Land and the Grail?

I've always been curious about the fact that while most of the stories of King Arthur take place in a vague far away and long ago" realm, the story of the Grail is specifically dated. Almost all versions of the tale concur that it began when Galahad arrived at King Arthur's court at Pentecost, 454 years after the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Given conventional wisdom, that would mean that the quest for the Holy Grail began in 487 AD (Jesus being 33 years old when he was crucified). Given that Galahad was 18 years old on when he arrived at court and that he was conceived at the same time Balin struck the dolorous strike that would date the origin of the Waste Land to 469 AD.

So could the Waste Land have been an actual event, a decimation of Northern Europe due to climate change invoked by an impact from an asteroid or meteorite throwing massive amounts of dust and smoke into the atmosphere? Prof. Baillie's cosmic impact theory, backed by dendrochronology , places the event around 536 AD, which is 67 years after 469 AD, however given the vagaries of medieval time measuring, calendar changes and the fact that authours like Mallory were writing nearly as far distant from the 6th century as we are from them, its close enough to give pause for thought.

Another curious link between the story of the Holy Grail and the idea of an object from space hitting the earth exist, mainly in the version of the legend mentioned above, Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzifal. The work is one of the earliest to deal with the Holy Grail (written circa 1220 AD) and unlike in other versions of the tale, Wolfram's grail is a stone, not a cup. Specifically, it is called the `Lapsit exillis'. This name is a piece of pseudo-latin that does not satisfactorily translate to any meaningful phrase, but two suggestions are "stone from exile" or "Stone from Heaven/the sky".

Wolfram specifically says the stone/Grail is kept by the Knights Templar, and that he learnt about the tale from a man called "Kyot", who in turn got it from a Jewish source in Moorish Spain. The Templar and Moorish link points to the The Fifth Pillar of Islam, the Hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca. One of the main rituals of the Hajj include walking seven times around the Kaaba and touching a Black Stone, an ancient cornerstone of the central structure within the Grand Mosque in Mecca. The most prevalent theory of the nature of The Black Stone is that it is a meteorite.

So all sorts of intriguing possibilities exist.

I've written before about how Norse mythology may contain a folk memory of a similar event. Perhaps someday I'll perhaps to pull the two together. It might make a good book.

Recently, an article appeared in the press about how British Police raided a pub in search of the Holy Grail: While the article is slightly weird, it proves the on-going fascination with the topic of the Grail. Obviously I share this fascination as the Quest for the Grail was the engine that drove my first novel, Lions of the Grail and, as the titles suggest, it was a theme that continued through the recently released sequel, The Waste Land and will persist through the third book in the series, tentatively titled “The Fisher King”.

The mystery of what the nature of the Grail actually is, issomething that fuels people’s fascination. It is generally described as a cup - the cup that was used at the Last Supper and also sometimes the cup used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch the blood of Christ as it flowed down from the cross. However over the centuries it has also been described as a cauldron, a plate with a severed head on it and, perhaps most odd, a stone that fell from the sky. Its the gloriously vague nature of the tales of the Grail combined with their multiple authours and the several strands of tradition -both Christian and Pagan- that have been entwined in their creation that have allowed all these interpretations to not just be created, but actually be plausible. I returned to this topic recently while I was re-reading Parzifal, the medieval German romance written by Wolfram von Eschenbach in the 13th century. While going through it I began to think that there may be more to the “Stone from the sky” interpretation than meets the eye, and in fact it may even be an echo of an actual, catastrophic event that happened in the 5th Century.

We are familiar, if a little uncomfortable, with the concept that every so often something hurtles out of deep space and smashes into the earth, wiping out large quantities of life causing massive devastation. It is the current popular theory, for example, of what killed off the dinosaurs.A few years ago Professor Mike Baillie of Queens University of Belfast appeared on a Channel 4 TV series which detailed the effects of a cosmic impact in the mid 6th century AD. The basic theory was that a large object, probably a comet or a asteroid had struck the earth in the Northern hemisphere sometime around 536 AD, throwing so much dust and debris into the air that it caused what we would refer to as a "nuclear winter".His theory is outlined in this article

Through tree ring dating and historical references he showed how over a period of several years vegetation had grown at a stunted rate leading to famine and disease throughout Northern Europe.This reminded me of the tales of King Arthur, particularly those surrounding the Quest for the Holy Grail. As most of those familiar with the tale will know, one of the roots of the Quest is the striking (unwittingly by Sir Balin) of the "Dolorous Blow", a fateful stroke that maims the Fisher King through the thighs, making him infertile and therefore destroying the fertility of the land, thus turning the kingdom into the "Waste Land". As Thomas Malory put it in his Le Morte d'Arthur: "and through that stroke three kingdoms shall be in great poverty, misery and wretchedness twelve years".

Medieval peasants struggling in mud

Medieval peasants struggling in mudIt is only the finding of the Grail that can heal the Waste Land. What if the folk memory of the cosmic impact had become mythologised into the legend of the Waste Land and the Grail?

I've always been curious about the fact that while most of the stories of King Arthur take place in a vague far away and long ago" realm, the story of the Grail is specifically dated. Almost all versions of the tale concur that it began when Galahad arrived at King Arthur's court at Pentecost, 454 years after the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Given conventional wisdom, that would mean that the quest for the Holy Grail began in 487 AD (Jesus being 33 years old when he was crucified). Given that Galahad was 18 years old on when he arrived at court and that he was conceived at the same time Balin struck the dolorous strike that would date the origin of the Waste Land to 469 AD.

So could the Waste Land have been an actual event, a decimation of Northern Europe due to climate change invoked by an impact from an asteroid or meteorite throwing massive amounts of dust and smoke into the atmosphere? Prof. Baillie's cosmic impact theory, backed by dendrochronology , places the event around 536 AD, which is 67 years after 469 AD, however given the vagaries of medieval time measuring, calendar changes and the fact that authours like Mallory were writing nearly as far distant from the 6th century as we are from them, its close enough to give pause for thought.

Another curious link between the story of the Holy Grail and the idea of an object from space hitting the earth exist, mainly in the version of the legend mentioned above, Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzifal. The work is one of the earliest to deal with the Holy Grail (written circa 1220 AD) and unlike in other versions of the tale, Wolfram's grail is a stone, not a cup. Specifically, it is called the `Lapsit exillis'. This name is a piece of pseudo-latin that does not satisfactorily translate to any meaningful phrase, but two suggestions are "stone from exile" or "Stone from Heaven/the sky".

Wolfram specifically says the stone/Grail is kept by the Knights Templar, and that he learnt about the tale from a man called "Kyot", who in turn got it from a Jewish source in Moorish Spain. The Templar and Moorish link points to the The Fifth Pillar of Islam, the Hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca. One of the main rituals of the Hajj include walking seven times around the Kaaba and touching a Black Stone, an ancient cornerstone of the central structure within the Grand Mosque in Mecca. The most prevalent theory of the nature of The Black Stone is that it is a meteorite.

So all sorts of intriguing possibilities exist.

I've written before about how Norse mythology may contain a folk memory of a similar event. Perhaps someday I'll perhaps to pull the two together. It might make a good book.

Published on August 19, 2014 05:55

June 9, 2014

Meet my main character: Fergus MacAmergin

This post is part of a blog hop called “Meet my Main Character”. I’ve been tagged in this by the estimable Simon (S.J.A.) Turney. If anyone is not familiar with Mr Turney’s work then shame on you, :-) . He is a Historical Novelist whose enormously successful Roman Army series, Marius’Mules has made him the poster child of independent writers. Simon now also writes a series set in Ottoman Istanbul. You can read his blog here: http://sjat.wordpress.com/

Today, I have decided to write about Fergus, the hero of my own attempt at Roman Army militaria, “The Spear of Crom”.

1) What is the name of your character? Is he/she fictional or a historical figure/person?The name of the character is Fergus MacAmergin. His original conception was in the ancient Irish hero Conal Cernach. Conal’s father was a poet/warrior/lesser God called Amergin, hence “Mac Amergin”. Fergus was originally to be called Conal, however a frequent comment I get asked when folk read the title of the book is “Isn’t Crom the God of Conan the Barbarian?” (he is, but Robert E Howard the writer who in the 1930s created Conan, borrowed the name of Crom from an ancient Irish pagan God) and Conal would have been too close to “Conan”.Fergus is a Hibernian Celt who finds himself in the Roman Army, part of an auxiliary cavalry regiment recruited from other Celts known as the “August Wing of Gauls”, the Ala Augusta Gallorum. He comes from a slightly obscure tribe called the Cruithne, who may or may not have been the same as the people we now call the Picts. It was this connection that prompted me to portray him as tattooed, the inspiration for the designs coming from a couple of symbols that frequently appear on Standing Stones from Pictish areas like these:

While Fergus is a fictional character, he did spring from a few fragments of historical fact. Gnaeus Julius Agricola is another major character in the book, and he was a real historical figure. Agricola was a Roman military tribune in Britain who later on became Governor. Not many people are luck enough to have a historian for a son-in-law, but Agricola was one of those folk and thanks to Tacitus, his daughter’s husband, we have a record of Agricola’s life and career. Tacitus mentions that Agricola kept an exiled Irish king as a companion, and "pretended to be his friend" with the view to using restoring him to his throne in Ireland as an excuse for a future invasion of the island by Rome. That invasion, of course never happened.

2.When and where is the story set?The story is set in the year 59 AD. Twenty years after the initial conquest, the Roman Army is still bogged down fighting insurgents in the Province of Britannia (Britain). The XIV Legion, led by General Gaius Suetonius Paulinus the brutal new Roman Governor, heads West to crush the Ordivices, a rebel tribe led by druid priests based on the Holy Island of Ynys Mon (Anglesey).

3) What should we know about him/her?He is a Celt, but he’s in the Roman Army. What’s that about? The Imperial Roman Army was not just made up of citizens in the Legions. They added to their ranks by recruiting troops from conquered nations. The Celts being superb horsemen, it was only natural that they formed a large part of the Roman Cavalry. The Latin word for cavalry was Ala -wing- and its from the plural form Alae that we get the modern English term “Allies”, which largely preserves the original meaning. While it may have been unusual for a Celt from Hibernia (Ireland) to be in the Roman cavalry, military records show that British tribesmen in Roman uniform took part in battles against other British tribes at the time.

4) What is the main conflict? What messes up his/her life?Fergus’ life is certainly messed up. He loses his wife and new born child, sacrificed to the God Crom by the Druids. He joins the Roman army but as a non-Gaul in a Gaulish regiment remains an outsider. He falls foul of his Commanding Officer, gets wrongly blamed for a superior’s stupid decision and ends up sent on a suicide mission.

5) What is the personal goal of the character?Fergus genuinely wants to be a Roman citizen. In his own words: “There is more luxury and comfort in a Roman army barracks than the hovels my people call palaces. The baths, the games, the gymnasia, the theatre, roads. libraries, books, underfloor heating: We have none of that, and that’s what I want.”Within the plot of the book though, he is motivated by revenge. On one level Fergus is driven by hatred of his God for what Crom has done to him. He sees himself as personally at war with the strange diety and his followers, the druids. One particular druid, Anfad, was partly responsible for the deaths of Fergus’ wife and child and now Fergus finds himself confronted by the same man in a different battlefield.

6) Is there a working title for this novel, and can we read more about it?The book is called “The Spear of Crom”7) When can we expect the book to be published?The book is already available from all good kindle retailers and online bookstores.

Today, I have decided to write about Fergus, the hero of my own attempt at Roman Army militaria, “The Spear of Crom”.

1) What is the name of your character? Is he/she fictional or a historical figure/person?The name of the character is Fergus MacAmergin. His original conception was in the ancient Irish hero Conal Cernach. Conal’s father was a poet/warrior/lesser God called Amergin, hence “Mac Amergin”. Fergus was originally to be called Conal, however a frequent comment I get asked when folk read the title of the book is “Isn’t Crom the God of Conan the Barbarian?” (he is, but Robert E Howard the writer who in the 1930s created Conan, borrowed the name of Crom from an ancient Irish pagan God) and Conal would have been too close to “Conan”.Fergus is a Hibernian Celt who finds himself in the Roman Army, part of an auxiliary cavalry regiment recruited from other Celts known as the “August Wing of Gauls”, the Ala Augusta Gallorum. He comes from a slightly obscure tribe called the Cruithne, who may or may not have been the same as the people we now call the Picts. It was this connection that prompted me to portray him as tattooed, the inspiration for the designs coming from a couple of symbols that frequently appear on Standing Stones from Pictish areas like these:

While Fergus is a fictional character, he did spring from a few fragments of historical fact. Gnaeus Julius Agricola is another major character in the book, and he was a real historical figure. Agricola was a Roman military tribune in Britain who later on became Governor. Not many people are luck enough to have a historian for a son-in-law, but Agricola was one of those folk and thanks to Tacitus, his daughter’s husband, we have a record of Agricola’s life and career. Tacitus mentions that Agricola kept an exiled Irish king as a companion, and "pretended to be his friend" with the view to using restoring him to his throne in Ireland as an excuse for a future invasion of the island by Rome. That invasion, of course never happened.

2.When and where is the story set?The story is set in the year 59 AD. Twenty years after the initial conquest, the Roman Army is still bogged down fighting insurgents in the Province of Britannia (Britain). The XIV Legion, led by General Gaius Suetonius Paulinus the brutal new Roman Governor, heads West to crush the Ordivices, a rebel tribe led by druid priests based on the Holy Island of Ynys Mon (Anglesey).

3) What should we know about him/her?He is a Celt, but he’s in the Roman Army. What’s that about? The Imperial Roman Army was not just made up of citizens in the Legions. They added to their ranks by recruiting troops from conquered nations. The Celts being superb horsemen, it was only natural that they formed a large part of the Roman Cavalry. The Latin word for cavalry was Ala -wing- and its from the plural form Alae that we get the modern English term “Allies”, which largely preserves the original meaning. While it may have been unusual for a Celt from Hibernia (Ireland) to be in the Roman cavalry, military records show that British tribesmen in Roman uniform took part in battles against other British tribes at the time.

4) What is the main conflict? What messes up his/her life?Fergus’ life is certainly messed up. He loses his wife and new born child, sacrificed to the God Crom by the Druids. He joins the Roman army but as a non-Gaul in a Gaulish regiment remains an outsider. He falls foul of his Commanding Officer, gets wrongly blamed for a superior’s stupid decision and ends up sent on a suicide mission.

5) What is the personal goal of the character?Fergus genuinely wants to be a Roman citizen. In his own words: “There is more luxury and comfort in a Roman army barracks than the hovels my people call palaces. The baths, the games, the gymnasia, the theatre, roads. libraries, books, underfloor heating: We have none of that, and that’s what I want.”Within the plot of the book though, he is motivated by revenge. On one level Fergus is driven by hatred of his God for what Crom has done to him. He sees himself as personally at war with the strange diety and his followers, the druids. One particular druid, Anfad, was partly responsible for the deaths of Fergus’ wife and child and now Fergus finds himself confronted by the same man in a different battlefield.

6) Is there a working title for this novel, and can we read more about it?The book is called “The Spear of Crom”7) When can we expect the book to be published?The book is already available from all good kindle retailers and online bookstores.

Published on June 09, 2014 12:47

April 11, 2014

The battle of Carrickfergus

As some of you may have read on Facebook, I experienced an odd co-incidence over the last couple of days. I'm currently writing the climax of a novel that will be the sequel to Lions of the Grail (tentatively titled "The Wasted Land") and found myself writing about a largely forgotten battle that took place in medieval Carrickfergus .

I've wanted to write about it for years because it sounds so brilliant- There was an amphibious assault, desperate fighting in the streets and a besieged castle where the defenders had turned to cannibalism. It all happened on Good Friday and Easter Saturday in 1316.

When I checked the date of Easter in 1316 I found it was on April 11, and I was writing a fictional account of events that had happened 698 years ago to the day.

Perhaps those old ghosts were calling to me over the centuries?

Anyway, for those who haven't heard about it, this is what happened.

In 1315, a year after defeating the English at Bannockburn, Edward Bruce (brother of Robert) invaded Ireland, starting a now largely forgotten side war to the Scottish Wars of Independence.

A year later, in 1316, his war had ground to a stalemate, exacerbated by the onset of the terrible European famine that would kill millions over the coming years. Carrickfergus Castle in Ulster still refused to surrender, something which must have particularly annoyed Edward Bruce who was now using Carrickfergus town as his new capitol (he had had himself crowned “King of Ireland” by this time).

This is a Carrickfergus castle on a more peaceful morning:

The besieged garrison in the castle were becoming desperate. Rather than see it fall, Sir Thomas de Mandeville-the exiled Seneshal of Ulster- launched a daring attempt to break the siege by sea, taking five ships packed with soldiers and supplies north from Dundalk. The Scottish poet and biographer of Robert Bruce, John Barbour, lists some of the chiefs of the Irish army:

"Brynrane, Wedounne, Fitzwarryne,And Schyr Paschall of Florentine,That was a knycht of Lumbardy,And was full of chewalry.The Mawndweillis war thar alsua,Besatis, Loganys, and other ma;Savages als, and yeit was ane

Hat Schyr Nycholl of Kylkenane."

If you've read Lions of the Grail you'll recognize the name Savage in there. :-)

The besieging Scots were taken by surprize. One chronicler says De Mandeville took treacherous advantage of a truce supposed to be in place for Easter week (Easter Sunday was April 11 in 1316). Only a small force of Scots, under command of Sir Neil Fleming, were watching the castle. The relief force landed in the harbour beside the castle and on April 10 De Mandeville launched his attack. Hopelessly outnumbered, Fleming choose bravely to fight them in order to buy time for the rest of the Scottish army to arm and arrive from their encampment outside the town.

Desperate street fighting ensued. Fleming was killed but succeeded in stalling the attackers. Edward Bruce and the rest of the Scottish army arrived and it was the turn of the Irish to be outnumbered. The battle spread throughout the town. De Mandeville, conspicuous among the Irish in his expensive plate armour, was singled out. Gib Harper, Bruce's arming man, felled De Mandeville with his axe. Edward Bruce finished the old knight off with his knife. With that the relief attack failed. Carrickfergus castle had to once more close its gates to avoid letting the Scots in.

Amazingly, the defenders managed to hold out for another five months, though this was achieved by eating some of the Scottish prisoners they had taken.

Amazingly, the defenders managed to hold out for another five months, though this was achieved by eating some of the Scottish prisoners they had taken.

So does Richard Savage survive? You'll have to read the new book to find out.

Ironically, as I write this, I find that it seems that some of the current occupants of the town decided to recreate some of these events....

http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/new...

I've wanted to write about it for years because it sounds so brilliant- There was an amphibious assault, desperate fighting in the streets and a besieged castle where the defenders had turned to cannibalism. It all happened on Good Friday and Easter Saturday in 1316.

When I checked the date of Easter in 1316 I found it was on April 11, and I was writing a fictional account of events that had happened 698 years ago to the day.

Perhaps those old ghosts were calling to me over the centuries?

Anyway, for those who haven't heard about it, this is what happened.

In 1315, a year after defeating the English at Bannockburn, Edward Bruce (brother of Robert) invaded Ireland, starting a now largely forgotten side war to the Scottish Wars of Independence.

A year later, in 1316, his war had ground to a stalemate, exacerbated by the onset of the terrible European famine that would kill millions over the coming years. Carrickfergus Castle in Ulster still refused to surrender, something which must have particularly annoyed Edward Bruce who was now using Carrickfergus town as his new capitol (he had had himself crowned “King of Ireland” by this time).

This is a Carrickfergus castle on a more peaceful morning:

The besieged garrison in the castle were becoming desperate. Rather than see it fall, Sir Thomas de Mandeville-the exiled Seneshal of Ulster- launched a daring attempt to break the siege by sea, taking five ships packed with soldiers and supplies north from Dundalk. The Scottish poet and biographer of Robert Bruce, John Barbour, lists some of the chiefs of the Irish army: