Tim Hodkinson's Blog, page 2

December 3, 2020

Chirstmas Blog Tour - Free Books!

The Historical Writers Forum is a facebook community made up of authours working in the Historical Fiction genre. This Christmas, like last year, some of its members are collaborating in a themed approach blog hop.

This year the theme of the blog hop is the Icelandic tradition of the Jólabókaflóðið. This began during World War II, when paper was one of the few commodities not rationed. Icelanders, being a nation of bookaholics, shared their love of books even more as other types of gifts were short supply, resulting in a flood of books at Yule, which is a rough translation of Jólabókaflóðið.

In line with this tradition, the Historical Writers will be giving away their books over the Christmas period, starting December 1. So I urge you to visit the blogs listed below on the appropriate day and see if you can win a few books.

As a writer of a series of viking novels, The Whale Road Chronicles, whose central character is an Icelander and whose action often returns to Iceland, I just had to take part. My day is the 18th, and on that day you will get the chance to win a paperback copy of the The Wolf Hunt, the latest novel in the series. It's literally hot off the presses (the release date is not until January).

Aries Fiction, the publisher of The Whale Road Chronicles, is also running a promotion on the first two books in the series, Odin's Game and The Raven Banner. From now until Christmas you can get the kindle versions for 99p.

Here are the Blog Hop Dates and links:

Dec 3rd Sharon Bennett Connolly

Dec 4th Alex Marchant

Dec 5th Cathie Dunn

Dec 6th Jennifer C Wilson

Dec 8th Danielle Apple

Dec 9th Angela Rigley

Angela Rigley – Welcome to The Writing Den

Dec 10th Christine Hancock

Byrhtnoth | A boy who became a man. The man who was Byrhtnoth.

Dec 12th Janet Wertman

Dec 13th Vanessa Couchman

Dec 14th Sue Barnard

Dec 15th Wendy J Dunn

Dec 16th Margaret Skea

Dec 17th Nancy Jardine

Dec 18th Tim Hodkinson

Dec 19th Salina Baker

Dec 20th Paula Lofting

1066: The Road to Hastings and Other Stories

Dec 21st Nicky Moxey

Dec 22nd Samantha Wilcoxson

Dec 23rd Jen Black

Dec 24th Lynn Bryant

February 9, 2020

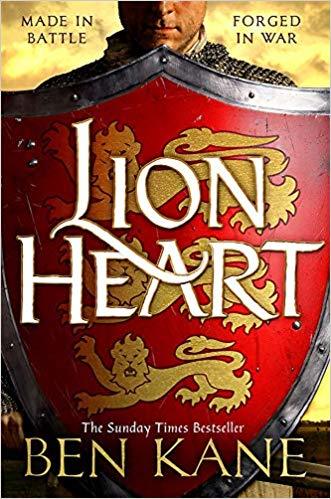

Interview with Ben Kane

For his latest novel, Lionheart, Sunday Times best selling author Ben Kane has swapped the classical antiquity of his previous novels for medieval Europe and the Middle East. Having studied Medieval English and Old Norse literature at University, it's an era that fascinates me and Ben was kind enough to answer some of my questions on his latest work.

Tim H: You’re probably best known for your Roman military novels. What brought about this departure in time and location?Ben: It’s a funny thing. I have always wanted and intended to write periods other than that of ancient Rome. Publishers, however, like something that does well, and so I had nothing but requests for more of the same for my first eleven novels. A plan to write a trilogy about the Hundred Years’ War was canned in favour of the Eagles of Rome series. Since 2017, however, I have had a new publisher, one who is keen for me to spread my wings, as it were (so I don’t get bored as much as anything else – apparently that is one of the reasons Bernard Cornwell moved away from Sharpe for a while).

Tim H: What particularly attracted you to a 12th Century European settingBen: Many periods of history have been covered over and again by novelists. Richard the Lionheart is a standout character about whom relatively few novels have been written in the last 25 years. I decided to set that right.

Tim H:: Richard the Lionheart’s life reads like a film script. Can we expect Errol Flynn style adventure or have you taken a different angle in your tale?Ben: Given the incredible richness of what he did, it would be foolish to stray too far from what he did. The story is recounted not by Richard, however, but by his loyal squire Ferdia – an Irishman (at last!). I can guarantee that my books will be historically accurate, unlike 99.99% of films!

Tim H:: Richard Cour de Lion is probably England’s most famous king. Even today you can still usually find a few fans at England’s Six Nations games dressed up as him. As an Irishman, had you any qualms with taking on this subject?Ben: I certainly did, which is why I took immense pleasure in making the main character Ferdia an Irishman. It’s like an in-joke!

Tim H: You are renowned for the lengths you go to in the name of research, once walking across Italy in full Roman army kit. Will this new venture see you riding to Jerusalem on a destrier or similar?Ben: I wish! That would be a trip and a half. I did travel to Israel at the beginning of 2020, however, to research the second book. An incredible trip, and an amazing country with the richest of histories.

Tim H: Creating an authentic sense of time and place can be hard enough for a writer without the extra hurdles of the language and culture that is so key to historical fiction. I recently wrote a blog for the History Quill (LINK) how something that brings this into sharp focus is swearing. What’s your thoughts on swearing and use of authentic language?Ben: I have to admit that my approach to it has changed a lot from my first novels, when I peppered every page, if not every paragraph, with obscenities. I did it then in an effort to make the books feel gritty, and more authentic. I was also less attentive to whether the curses fitted for the time. As time went on, and I did eccentric things like walking Hadrian's Wall in Roman armour, I found myself taking more and more pride in research and that 'sense of time and place' that is so vital to historical fiction. I changed the type of curses, reducing the use of 'fuck', which the Romans had in their lexicon, but which was more rarely used than 'cocksucker', or the hideous 'C' word. In earlier novels, I used to explain in the author's note that the 'C' word was more commonly used by the Romans than 'fuck', and I was sparing people's sensibilities by not using it. I can't remember exactly when - it might have been the Eagles of Rome trilogy - when I decided that being more authentic was better. Out went 'fuck' for the most part, and in came the 'C' word, and 'cocksucker'. And yet I found myself using curses less. Less is more, the saying goes, and I have come round to that point of view, so much so that during the writing of Lionheart, I avoided cursing if at all possible unless it was to use twelfth century oaths. They sound quaint, even funny, to the modern ear, but they are contemporary. Who knew that Richard the Lionheart's favourite curse was 'God's legs!'

Tim H:: Is Lionheart a standalone novel of will we see more of Ferdia and Richard in the future?Ben: It is the first of three novels (although I have the plot of a loosely-linked fourth that could be written in the future). The second, Lionheart: Crusade, will come out in May 2021, and the third (title as yet unknown) will release in 2022

Lionheart is released on May 14th. You can pre-order it at this link: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Lionheart-Ben-Kane/dp/140917347X

December 20, 2019

A viking christmas

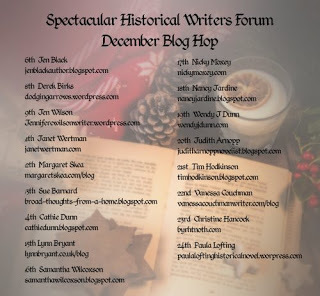

As my current series of historical novels, The Whale Road Chronicles, is set in the Viking Age, I thought that as my part in this year's Spectacular Historical Writers Forum December Blog Hop should look at what the norse got up to at this time of year.

The lights on one side of Belfast City Hall wish folks a “Blythe Yuletide”, using the alternative name for the Christmas season that can still be found used in various arts and parts.

The lights on one side of Belfast City Hall wish folks a “Blythe Yuletide”, using the alternative name for the Christmas season that can still be found used in various arts and parts.Yule, or Jól to give it the Scandinavian spelling, was a mid-winter festival celebrated across northern Europe. The fact that variations of a word for it exists in Old English (where it was known as ġéol), Old Norse, Icelandic, Faroese, Norwegian Danish, and Swedish shows how widespread it was. A variation of the word appears in the (now extinct) Gothic language in a 6th Century text, which shows how old it is.

Like a lot of heathen traditions, what was actually involved in Yule is largely lost to time but can we trace any of our modern traditions back to the vikings?

Yule is mentioned in many sagas but usually as a marker for the time of year, rather than telling us what went on. A lot of vikings and kings go on expeditions “after Yule”. What can be discerned from the medieval sagas is that Yule involved several consecutive days of feasting (perhaps 13 or more) and gifts were given out. Also spooky things seem to happen around that time.

Gift giving is well attested in the sagas, and also in Medieval English Literature, particularly in the poem known as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which was written in a part of England that was under heavy Norse influence. I’ve covered the potential identity of Sir Bertilak de Haut Desert in a previous post but I’ll touch on an older candidate for that role later here. The Saga of Olaf Haraldsson (in Heimskringla) has a whole section on "King Olaf's presents at Yule". The text mentions that at Yule in 1028, the King " had, according to his custom, collected there with great care the valuable presents he was to make" which included very valuable gold-mounted swords he would present to his most loyal retainers, as ring giver kings had done since time immemorial. Some rulers, however, may not have been so generous. Svein Knutsson, a Danish King, used the tradition to increase the oppression of his Norwegian subjects, demanding they pay him substantial Yule gifts every year:“At Yule each farmer was to give the king a measureof malt for each hearth, a ham from a three-year-old ox—this was called ‘a bit of the meadow’90—and a measure ofbutter; and each housewife should supply a ‘lady’s tow’91—that was as much clean flax as could be clasped betweenthumb and middle finger.”-from Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum

Gift giving is well attested in the sagas, and also in Medieval English Literature, particularly in the poem known as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which was written in a part of England that was under heavy Norse influence. I’ve covered the potential identity of Sir Bertilak de Haut Desert in a previous post but I’ll touch on an older candidate for that role later here. The Saga of Olaf Haraldsson (in Heimskringla) has a whole section on "King Olaf's presents at Yule". The text mentions that at Yule in 1028, the King " had, according to his custom, collected there with great care the valuable presents he was to make" which included very valuable gold-mounted swords he would present to his most loyal retainers, as ring giver kings had done since time immemorial. Some rulers, however, may not have been so generous. Svein Knutsson, a Danish King, used the tradition to increase the oppression of his Norwegian subjects, demanding they pay him substantial Yule gifts every year:“At Yule each farmer was to give the king a measureof malt for each hearth, a ham from a three-year-old ox—this was called ‘a bit of the meadow’90—and a measure ofbutter; and each housewife should supply a ‘lady’s tow’91—that was as much clean flax as could be clasped betweenthumb and middle finger.”-from Ágrip af NóregskonungasögumEventually, in 1090, King Magnus Barefoot "did away with Yule-gifts" and so won great popularity.

Heavy drinking and overeating appear to be an important part of the Yule feast, two activities still carried on at Christmas today. For example there is this description in Heimskringla:“There was a great Yule feast and ale-drinking, to which each brought his own liquor; for there were many peasants in the village, who all drank in company together at Yule. There was another village not far distant, where Thorar's brother-in-law dwelt, who was a rich and powerful man, and had a grown-up son. The brothers-in-law intended to pass the Yule in drinking feasts, half of it at the house of the one and half with the other; and the feast began at Thorar's house. The brothers-in-law drank together, and Thorod and the sons of the peasants by themselves; and it was a drinking match”

Another common event at Norse and Old English feasts was the swearing of oaths in front of the assembled feasters. These were promises, sometimes called boasts, of what individuals would achieve in the year ahead. Given their public nature, these were more than empty aspirations and failure to fulfil them would result in loss of honour. This is where our tradition of making New Year’s Resolutions came from. So this year when you fail to lose a few pounds in January think how more onerous that would have been for your Viking ancestors.

Yule was also a time when strange things happened. For example Heimskringla relates how King Halfdan the Black of Norway, while “at a Yule-feast in Hadeland”, “a wonderful thing happened”. When the guests assembled to sit down at the table, “all the meat and all the ale disappeared from the table” due to some weird magic worked by a Finnish man.

In Grettir’s Saga, the thrall Glamr famously is turned into an undead monster after eating meat on Yule eve. In Icelandic tales ghosts of the ancestors returned to their former homesteads to warm themselves at the hearth and it was common to leave baked loaves and a drink for them there, another tradition we still do today, though the cookies are now for a different visitor.

The Icelandic medieval manuscript known as Flateyjarbók mentions that a certain god was associated with Yule, Odin. “Here it is fitting to elucidate a problem posed by Christian men as to what heathen men knew about Yule, for our Yule has its origin in the birth of Our Lord. Heathen menhad a feast, held in honour of Ódinn, and Ódinn is called by many names: he is called Vidrir and he is called Hár and Firidi and Jólnir; and it is after Jólnir that Yule [Jól] is named.”

Odin was indeed known by many names, and another one was Jölföðr, which literally means “Yule Father”, or Father Yule. Just as Yule merged into Christmas, Father Yule came with it, giving us the origin of the most mercurial of figures, the Jolly Old Elf himself, Father Christmas.

For more spectacular christmas blogging, check out the next instalment on the hop from the brilliant Vanessa Couchman or check out some of the the others in the tour, outlined below.

September 21, 2019

The vikings on Lough Neagh

The largest freshwater lake in the British Isles (by area), sitting at the heart of Ulster and with ingress and egress to the sea via the Upper and Lower Bann and the Blackwater rivers, Lough Neagh was a perfect base for water-borne raiders like the Vikings.

Once in there they could strike in any direction and sail away again, their ships full of loot. The political situation of early medieval Ireland also helped them as the lake sat in the middle of different kingdoms and clan territories, as this map of early 8th Century Ireland shows:

With Norse coastal settlements already established in the likes of Dublin, Waterford, Cork, and Limerick, the Vikings -or “Ostmen” (men from the east) as they called themselves- began to push inland by sailing their shallow-keeled longships up the navigable rivers and into the inland lakes such as Lough Ree on the Shannon, Lough Erne and Lough Neagh. From these bases they could ravage the interior of the country.

The Annals of Ulster first mention Vikings on Lough Neagh in the year 839 A.D which records “A raiding party of the foreigners were on Loch nEchach [Lough Neagh], and from there they plundered the states and churches of the north of Ireland.” A year later the annals state “Lugbad [Louth Priory] was plundered by the heathens from Loch nEchach and they led away captive bishops and priests and scholars, and put others to death.”

There is also a reference in 840 to Armagh being burned, but it’s not clear by who. However, we might be able to guess. The annals reported that in 841 “The heathens were still on Loch nEchach.”

They appear to have left soon after, however, possibly related to a defeat inflicted on their (semi-legendary) leader named in the annals as “Tuirgéis” – probably Old Norse Thorgestr – in 845.

Eighty three years later, in 928, the annals record that the Vikings were back on Lough Neagh.“Ailche's son went on Loch nEchach with a fleet of the foreigners, and he ravaged the islands of the lake and the territories bordering it.”

This “Ailche’s son” is mentioned several times in the annals, having previously ravaged Clonmacnoise in 922. The interesting thing is his name, which suggests he was Irish, or more likely that the Norse were by now integrating and inter-marrying into Irish culture and adopting Irish names.

In 930 the annals report that “Foreigners on Loch nEchach, and their naval camp was at Rubha Menna.” The Life of Saint Columba mentions that this place is at Shane’s castle, where the River Maine flows into the Lough.

The tale appears to come to an end in 945, when “The foreigners of Loch nEchach were killed by Domnall son of Muirchertach and by his kinsman, i.e. Flaithbertach, and their fleet was destroyed.”

They left behind their own memorial though, in the name of Oxford Island outside Craigavon. “Oxford” comes from the Old Norse Ost Fjordr, perhaps “East Fjord” or maybe they were trying to lay claim to the whole lake, which they would have called a fjord, using their name for themselves, the Ostmen.

Several people have asked where the island in Ireland is which is attacked by the viking Wolf Warriors in Odin’s Game. To clear that up, it’s Coney Island on Lough Neagh.

September 15, 2019

September 8, 2019

Mail Trolls and Atgeirs ��� the mysterious world of Viking Pole Weapons

Mail Trolls and Atgeirs – the mysterious world of Viking Pole Weapons

June 25, 2017

Northburgh

This is Northburgh castle, aka Green Castle in the little town of Greencastle in County Donegal, scene of some medieval barbarity in 1333 that had far-reaching consequences.Northburgh was built in 1306 by Richard Og de Burgh, the famous “Red” Earl of Ulster who appears in Lions of the Grail. Standing guard at the mouth of Lough Foyle, it marked the western limit of de Burgh’s Earldom. It was in the territory of the Kingdom of Tyrconnell and was probably supposed to be a bridgehead from which he would march on to the the western Atlantic shore, however that was not to be. In 1315 Edward Bruce took it, but de Burgh won it back. In 1333 it was the scene of some infamous deeds that would lead to the end of the Earldom itself.For some reason, at that time the Anglo-Norman clan of de Burgh seem to have been differentiated by colours. Richard “Og”, Gaelic for “little Richard” (honestly), was known as the “Red” Earl. His cousin, William, was known by the nickname “laith”, which is Gaelic for grey. William Laith deBurgh of Connaught served under Piers Gaveston when he was Justiciar of Ireland and was a hero of the war of 1315-18 against the invading Scots under Edward Bruce. William married Finola Ni Briain and one of their many offspring was Walter de burgh, also known as the “laith”. William fought at the battle of Connor, where he was taken prisoner. It was to pay ransom for William that Earl Richard diverted the ships packed with supplies bound for the desperate besieged garrison of Carrickfergus castle to Scotland.This in turn led to the daring sea raid on Carrickfergus portrayed in the sequel of Lions of the Grail, “The Waste Land”.Richard de Burgh was Earl of Ulster and also Lord of Connacht. In practice, William laith had been Lord of Connacht in all but name, particularly after his victory at the head of a rather rag-tag coalition of Anglo Normans and Gaelic clans at the very bloody Second Battle of Athenry during the Bruce War. His son Walter took this one step further after the death of William and had himself named Lord of Connacht in 1330. This put him in direct conflict with his cousin, the Earl of Ulster who by then was Richard Og’s grandson, also called William. In true de Burgh tradition, this William was known as William “Donn” - the Gaelic word for “brown”.This meant war. William quickly captured Walter and imprisoned him in Northburgh. In an act of cruelty that would have serious repercussions, he had his cousin starved to death in the castle.It has been said that in medieval times, what now look like titanic struggles between nations, at the top-end of society were more like family feuds. Richard de Burgh, or example, was Robert Bruce’s father in law. Walter laith’s sister, Gylle de Burgh, was married to Sir Richard de Mandeville, one of the Earl of Ulster’s chief vassals. Gylle persuaded her husband to take revenge. They conspired with John de Logan, another of the Earl’s knights, and in June of 1333, at (what then was) a little village named “le Ford” by the Normans and “Béal Feirste” (Belfast) by the Irish, they assassinated William the Brown Earl of Ulster. This led to chaos and the de burghs descended into an internecine bloodbath now referred to as the “Burke Civil War”. It also spelt the end of the Anglo-Irish Earldom of Ulster that dissolved quickly afterwards as the Gaelic Kings took advantage of the disarray and re-asserted their power.

This is Northburgh castle, aka Green Castle in the little town of Greencastle in County Donegal, scene of some medieval barbarity in 1333 that had far-reaching consequences.Northburgh was built in 1306 by Richard Og de Burgh, the famous “Red” Earl of Ulster who appears in Lions of the Grail. Standing guard at the mouth of Lough Foyle, it marked the western limit of de Burgh’s Earldom. It was in the territory of the Kingdom of Tyrconnell and was probably supposed to be a bridgehead from which he would march on to the the western Atlantic shore, however that was not to be. In 1315 Edward Bruce took it, but de Burgh won it back. In 1333 it was the scene of some infamous deeds that would lead to the end of the Earldom itself.For some reason, at that time the Anglo-Norman clan of de Burgh seem to have been differentiated by colours. Richard “Og”, Gaelic for “little Richard” (honestly), was known as the “Red” Earl. His cousin, William, was known by the nickname “laith”, which is Gaelic for grey. William Laith deBurgh of Connaught served under Piers Gaveston when he was Justiciar of Ireland and was a hero of the war of 1315-18 against the invading Scots under Edward Bruce. William married Finola Ni Briain and one of their many offspring was Walter de burgh, also known as the “laith”. William fought at the battle of Connor, where he was taken prisoner. It was to pay ransom for William that Earl Richard diverted the ships packed with supplies bound for the desperate besieged garrison of Carrickfergus castle to Scotland.This in turn led to the daring sea raid on Carrickfergus portrayed in the sequel of Lions of the Grail, “The Waste Land”.Richard de Burgh was Earl of Ulster and also Lord of Connacht. In practice, William laith had been Lord of Connacht in all but name, particularly after his victory at the head of a rather rag-tag coalition of Anglo Normans and Gaelic clans at the very bloody Second Battle of Athenry during the Bruce War. His son Walter took this one step further after the death of William and had himself named Lord of Connacht in 1330. This put him in direct conflict with his cousin, the Earl of Ulster who by then was Richard Og’s grandson, also called William. In true de Burgh tradition, this William was known as William “Donn” - the Gaelic word for “brown”.This meant war. William quickly captured Walter and imprisoned him in Northburgh. In an act of cruelty that would have serious repercussions, he had his cousin starved to death in the castle.It has been said that in medieval times, what now look like titanic struggles between nations, at the top-end of society were more like family feuds. Richard de Burgh, or example, was Robert Bruce’s father in law. Walter laith’s sister, Gylle de Burgh, was married to Sir Richard de Mandeville, one of the Earl of Ulster’s chief vassals. Gylle persuaded her husband to take revenge. They conspired with John de Logan, another of the Earl’s knights, and in June of 1333, at (what then was) a little village named “le Ford” by the Normans and “Béal Feirste” (Belfast) by the Irish, they assassinated William the Brown Earl of Ulster. This led to chaos and the de burghs descended into an internecine bloodbath now referred to as the “Burke Civil War”. It also spelt the end of the Anglo-Irish Earldom of Ulster that dissolved quickly afterwards as the Gaelic Kings took advantage of the disarray and re-asserted their power. William’s only child was Elizabeth de Burgh. She fled Ulster with her mother and settling in London she married Lionel of Antwerp, the Duke of Clarence. It was as page to Elizabeth, Countess of Ulster, that a young man called Geoffrey Chaucer took up his first job. The rest, as they say, is history.

June 2, 2017

Mr Wednesday

If (like me) you are a fan of Neil Gaiman’s “American Gods” you’re probably enjoying the new TV series based on the novel. While it’s no secret that Ian McShane’s character is based on the old Norse god, Odin, some might be wondering why he’s called “Mr Wednesday”.The answer lies in the distant past, to the time before the country of England existed. In the Fifth Century AD, the Angles, Saxons and Jutes who crossed the seas to take land in a Britain that had been so recently deserted by Rome sprang from the same Germanic clans who also drifted north to Scandinavia and later gave rise to the vikings. They all spoke a similar language that came from the same root and they worshipped the same gods. Old English and Old Norse are sister languages, but though similar they already showed signs of diverging as the Roman Empire crumbled. For these reasons the names of the Gods varied in the different lands that these clans settled in.Famously, the Scandinavians worshipped a god called Odin. Ancient, mysterious, a one-eyed magic maker, this strange entity who went by over a hundred other names was at once the god of war and of poetry. His gift was the homicidal rage that drove berserker viking warriors into a killing frenzy and also the trance like state poets slipped into to compose verse. A walking contradiction, some might say, his persona of a wandering old, long bearded man in a grey cloak, a staff and wide brimmed hat has survived into our age as the model J R R Tolkien used for the wizard Gandalf.Another tribe, the Lombards, migrated from southern Scandinavia to eventually end up in Northern Italy. Due to a linguistic shift in consonant pronunciation, their legends speak of a similar deity called “Godan”. Fans of Wagner will know that the tribes who remained in Germany called him “Votan”. To the Anglo-Saxons who crossed to Britain, he was “Wodan”.The Anglo Saxons became Christian centuries before their Norse cousins and though they have left us a rich literature mentions of Woden are few and far between, for the obvious reason that most of it was written by Christian churchmen with no desire to preserve heathen lore. There is a disparaging reference for example about how Woden made idols but the Lord made the heavens and the earth. However, there are enough traces of him left to be able to tell that Woden was regarded as similar in many ways to Odin, but also different in others: Very much like Mr Wednesday in “American Gods”, who is what Odin became when transplanted to another land and mixed with other rival cultures and environments.While he left little in the written record, Woden left his mark on the landscape of England. The Norse revered Odin as wise, the seeker and hoarder of arcane knowledge and magic. The Anglo Saxons seemed to have translated that aspect into engineering ability. Finding earthworks and neolithic monuments beyond any building capability they possessed, their only response was that it must be the work of Woden and his “magic”. In the same way their medieval descendants ascribed the erection of Stonehenge and other seemingly impossible constructions to the wizard Merlin, the Anglo Saxons named the lengthy defensive dykes they came across in the South West of Britain as “Wansdyke” - Woden’s Dyke. There are multiple “Woden’s Burghs” - stone age barrows renamed as the “Burgh [fort/hill/defence] of Woden”: Wednesbury in the Black Country, Woodnesborough in Kent, a Wanborough in Surrey and another in Wiltshire, Wembury in Devon and a Woodborough also in Wiltshire. Those familiar with the raging Viking war god Odin may be surprised with another power the Anglo Saxons seem to have ascribed to his English cousin. Two of the few literary mentions of Woden’s name are associated with healing. The famous “Nine Herbs Charms” from the Lacnunga invokes Woden as one who drives out poisons and infections. Similarly another Old Saxon charm uses Woden’s name to heal sprains, binding “Bone to bone, blood to blood, joints to joints, so may they be mended”.

There is an oblique reference in an Old English text to Woden as the one who invented “letters” or rather runes. That is something that he shares with the Scandinavian version of himself. This reference to Woden is in the prose “Soloman and Saturnus” which actually names him as “Mercurius the Giant”. We know this is Woden because going back to Classical times Woden/Odin/Votan has been equated with the Roman God Mercury. Roman writers did not name the Gods of the Celtic and Germanic people they encountered by their native names. Instead, by a process known as “interpretatio Romana” they saw them as local manifestations of their own, Roman, Gods and so named them that way. The Roman historian Tacitus wrote that the Germanic tribes’ chief God (i.e. Odin/Woden) was Mercury. This is parallelled when it came to naming of the days of the week. In those parts of Europe heavily influenced by Rome and the Latin language, the name of the fourth day of the week is “Mercury’s Day”. The French, for example call it “Mercredi”. The Anglo Saxons called it “Wōdnesdæg” - Woden’s day, which over time became Wednesday, and this is where the name of Ian McShane’s character in American Gods came from.

May 18, 2017

The downfall of John de Courcy

There seems to be consensus that “Rath” is the castle de Courcy built at what is now Dundrum in County Down, though the Irish annals all say the fight took place outside Carrickfergus, making me now think it was actually at the place now called Rathcoole, which lies between Carrick and Belfast. Here is a picture of Dundrum castle anyway.https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/03/Dundrum_Castle_02.jpg

What the the eventual fate of de Courcy was, is obscure. Wikipedia says he “died in poverty near Craigavon but when I checked the book it references (The Churches and Abbeys of Ireland) there is no mention of this. There is also an entertaining story about de Courcy fighting a French champion related by Mark Twain in “The Prince and the Pauper” but that would extend this post even further.