Tim Hodkinson's Blog, page 4

October 28, 2015

Halloween, part one: Pagan origins

“Hallowe’en is coming and the goose is getting fat…”So goes the song that we used to sing as children when we went “round the doors” on Halloween night. It’s safe to say the old festival has had a bit of a resurrection in recent years. The traditions of trick or treat and carving pumpkins would give you the idea that Halloween is a North American custom, however if anything its origins and survival lie in Ireland and Scotland, and it was the Scots Irish who took it to America a few hundred years ago. After a childhood of blistered hands from trying to scoop out raw turnips, I have to say that those ancestors must have been delighted to come across the more easily carved pumpkin in the New World from which they could make their surrogate severed heads (more on that later) to replace the more resistant turnip.

A turnip lantern

A turnip lantern

Perhaps mysterious is why were the Scots and Scots-Irish -almost all staunch Presbyterians- so keen on celebrating this old Celtic festival? Paganism in general and all things Gaelic in particular usually have the same effect on the Scots-Irish that garlic has to vampires. The answer is probably a mixture of a couple of things. The first reason is that they simply always celebrated it, and tradition is a very hard thing to kill.It could be argued that Samhain had particularly significance in the North of Ireland from time immemorial. Samhain, the pre-christian name for the festival was one of the old quarter-days of the year celebrated by the ancient people of Ireland. A word very close to Samhain appears on the 2nd Century AD Coligny Calendar, suggesting that Celtic cousins in Europe celebrated the festival too. There are lots of references in Early Irish Literature to great clan gatherings and festivals being held at this time of year, and the adventures of heroes and kings that take place at them seem to revolve around a lot of drinking and either the dead or evil fairies coming back from the otherworld to wreck some form of havoc. There are various hints that could well suggest human sacrifice as well, but its hard to say for certain. Irish pagan Gods (Lugh on the left?) from the Ulster Museum

Irish pagan Gods (Lugh on the left?) from the Ulster Museum

The tales were written down by medieval Christian monks and could be biased against Paganism. The idea that our ancestors practised human sacrifice is also a slightly controversial idea to some. There are modern neo-pagans who will state that there is no evidence that ancient pagans sacrificed humans. I would argue that there is actually lots. Bog bodies for example exhibit such a degree of overkill that it points to some form of ritual, the only alternative being that for centuries psychopathic killers across northern Europe dispatched their victims using remarkably similar methods. Classical writers like Julius Caesar (again admittedly biased against the non-Roman Celts) all attest that the Druids sacrificed people to their Gods. However its not just neo-pagans who object to this idea. There are plenty of others who seem to find the idea that Irish people would kill other Irish people for religious reasons completely beyond the pale. Personally, while its not definitive, I think the evidence points to the fact that it happened, and that this time of year was particularly associated with it.

One place where Samhain and human sacrifice are explicitly linked is in the worship of the God Crom Cruach. If anyone has heard of Crom these days, the chances are it is as the God worshiped by Conan the Barbarian, either in Robert E Howard’s sword and sandal epics, or in the 1980s movie starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Who could forget such classic cinematic moments this?

But he was in fact a deity worshipped in ancient Ireland. He is, however, a bit of a puzzle. He doesn’t appear in the cannon of Early Irish Literature but in the tales of Saint Patrick, it’s Crom and his ministers who seem to be the main Pagan opposition to the Saint’s mission. The Dindsenchas that tell the lore of the land and the Annals of the Four Masters both talk of a festival at that this time of year which honoured Crom at a gathering in Magh Slécht, which is in modern county Cavan. Worship of Crom in ancient Ireland appears to be associated with a sacred bull, standing stones - an ancient name for a ring of standing stones was a “cromlech”- and, as readers of my novel “The Spear of Crom” will know, human sacrifice. The sources say that at Samhain, first born children were sacrificed to Crom. If true, the terror and horror instilled by what went on that night still echo in the modern Halloween. I think it’s interesting that the Annals of the Four Masters chose to include Crom when other annals don’t. They were compiled in a Friary on the edge of Donegal. Magh Slecht, the centre of Crom worship, and where his standing stone may still lie, is in County Cavan, suggesting that Samhain and Crom were of significance to the ancient people of Ulster. I’ve already written about how a portion of those people later on ended up founding a kingdom across the Irish sea so it should be no surprise that the other place where you find references to Crom is in the Highlands of Scotland. There is a Scottish Gaelic saying recorded in Lochaber that mentions “Domhnaich Crom Dubh” -Black Crom Sunday.So my thesis is that the festival of Samhain, held at this time of the year, was special for the people of Ireland and Ulster in particular. A portion of those folk migrated to what is now Scotland at the beginning of what some call “the Dark Ages” and they took with them the festival and all its associated trappings of death and fear. Time past and Samhain became Halloween, but the festival’s popularity in Scotland carried on. Some of those Scottish folk then migrated (or rather were “planted”) back in Ulster in the 1600s and they brought the tradition back with them, probably finding that the Irish were still celebrating in a similar fashion. A few years later some of those folk -now referred to as “Scots-Irish” - migrated to America and took the festival with them there, where it’s safe to say it was a huge success. I said I believed there were two reasons for the popularity of Halloween with the Scots Irish. The second reason is to do with witches, however that (and the explanation about the severed heads) will have to wait for another post which I’ll put up over the next day or so. In the meantime, if you want a chilling read for Halloween, my new novel set in Victorian Belfast, “The Undead” is available now on Kindle.

Or you can read about Fergus MacAmergin’s battles with the Druids of Crom in my novel “The Spear of Crom”, available on Kindle and in paperback

A turnip lantern

A turnip lanternPerhaps mysterious is why were the Scots and Scots-Irish -almost all staunch Presbyterians- so keen on celebrating this old Celtic festival? Paganism in general and all things Gaelic in particular usually have the same effect on the Scots-Irish that garlic has to vampires. The answer is probably a mixture of a couple of things. The first reason is that they simply always celebrated it, and tradition is a very hard thing to kill.It could be argued that Samhain had particularly significance in the North of Ireland from time immemorial. Samhain, the pre-christian name for the festival was one of the old quarter-days of the year celebrated by the ancient people of Ireland. A word very close to Samhain appears on the 2nd Century AD Coligny Calendar, suggesting that Celtic cousins in Europe celebrated the festival too. There are lots of references in Early Irish Literature to great clan gatherings and festivals being held at this time of year, and the adventures of heroes and kings that take place at them seem to revolve around a lot of drinking and either the dead or evil fairies coming back from the otherworld to wreck some form of havoc. There are various hints that could well suggest human sacrifice as well, but its hard to say for certain.

Irish pagan Gods (Lugh on the left?) from the Ulster Museum

Irish pagan Gods (Lugh on the left?) from the Ulster MuseumThe tales were written down by medieval Christian monks and could be biased against Paganism. The idea that our ancestors practised human sacrifice is also a slightly controversial idea to some. There are modern neo-pagans who will state that there is no evidence that ancient pagans sacrificed humans. I would argue that there is actually lots. Bog bodies for example exhibit such a degree of overkill that it points to some form of ritual, the only alternative being that for centuries psychopathic killers across northern Europe dispatched their victims using remarkably similar methods. Classical writers like Julius Caesar (again admittedly biased against the non-Roman Celts) all attest that the Druids sacrificed people to their Gods. However its not just neo-pagans who object to this idea. There are plenty of others who seem to find the idea that Irish people would kill other Irish people for religious reasons completely beyond the pale. Personally, while its not definitive, I think the evidence points to the fact that it happened, and that this time of year was particularly associated with it.

One place where Samhain and human sacrifice are explicitly linked is in the worship of the God Crom Cruach. If anyone has heard of Crom these days, the chances are it is as the God worshiped by Conan the Barbarian, either in Robert E Howard’s sword and sandal epics, or in the 1980s movie starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Who could forget such classic cinematic moments this?

But he was in fact a deity worshipped in ancient Ireland. He is, however, a bit of a puzzle. He doesn’t appear in the cannon of Early Irish Literature but in the tales of Saint Patrick, it’s Crom and his ministers who seem to be the main Pagan opposition to the Saint’s mission. The Dindsenchas that tell the lore of the land and the Annals of the Four Masters both talk of a festival at that this time of year which honoured Crom at a gathering in Magh Slécht, which is in modern county Cavan. Worship of Crom in ancient Ireland appears to be associated with a sacred bull, standing stones - an ancient name for a ring of standing stones was a “cromlech”- and, as readers of my novel “The Spear of Crom” will know, human sacrifice. The sources say that at Samhain, first born children were sacrificed to Crom. If true, the terror and horror instilled by what went on that night still echo in the modern Halloween. I think it’s interesting that the Annals of the Four Masters chose to include Crom when other annals don’t. They were compiled in a Friary on the edge of Donegal. Magh Slecht, the centre of Crom worship, and where his standing stone may still lie, is in County Cavan, suggesting that Samhain and Crom were of significance to the ancient people of Ulster. I’ve already written about how a portion of those people later on ended up founding a kingdom across the Irish sea so it should be no surprise that the other place where you find references to Crom is in the Highlands of Scotland. There is a Scottish Gaelic saying recorded in Lochaber that mentions “Domhnaich Crom Dubh” -Black Crom Sunday.So my thesis is that the festival of Samhain, held at this time of the year, was special for the people of Ireland and Ulster in particular. A portion of those folk migrated to what is now Scotland at the beginning of what some call “the Dark Ages” and they took with them the festival and all its associated trappings of death and fear. Time past and Samhain became Halloween, but the festival’s popularity in Scotland carried on. Some of those Scottish folk then migrated (or rather were “planted”) back in Ulster in the 1600s and they brought the tradition back with them, probably finding that the Irish were still celebrating in a similar fashion. A few years later some of those folk -now referred to as “Scots-Irish” - migrated to America and took the festival with them there, where it’s safe to say it was a huge success. I said I believed there were two reasons for the popularity of Halloween with the Scots Irish. The second reason is to do with witches, however that (and the explanation about the severed heads) will have to wait for another post which I’ll put up over the next day or so. In the meantime, if you want a chilling read for Halloween, my new novel set in Victorian Belfast, “The Undead” is available now on Kindle.

Or you can read about Fergus MacAmergin’s battles with the Druids of Crom in my novel “The Spear of Crom”, available on Kindle and in paperback

Published on October 28, 2015 02:32

Halloween, part one

“Hallowe’en is coming and the goose is getting fat…”So goes the song that we used to sing as children when we went “round the doors” on Halloween night. It’s safe to say the old festival has had a bit of a resurrection in recent years. The traditions of trick or treat and carving pumpkins would give you the idea that Halloween is a North American custom, however if anything its origins and survival lie in Ireland and Scotland, and it was the Scots Irish who took it to America a few hundred years ago. After a childhood of blistered hands from trying to scoop out raw turnips, I have to say that those ancestors must have been delighted to come across the more easily carved pumpkin in the New World from which they could make their surrogate severed heads (more on that later) to replace the more resistant turnip.

A turnip lantern

A turnip lantern

Perhaps mysterious is why were the Scots and Scots-Irish -almost all staunch Presbyterians- so keen on celebrating this old Celtic festival? Paganism in general and all things Gaelic in particular usually have the same effect on the Scots-Irish that garlic has to vampires. The answer is probably a mixture of a couple of things. The first reason is that they simply always celebrated it, and tradition is a very hard thing to kill.It could be argued that Samhain had particularly significance in the North of Ireland from time immemorial. Samhain, the pre-christian name for the festival was one of the old quarter-days of the year celebrated by the ancient people of Ireland. A word very close to Samhain appears on the 2nd Century AD Coligny Calendar, suggesting that Celtic cousins in Europe celebrated the festival too. There are lots of references in Early Irish Literature to great clan gatherings and festivals being held at this time of year, and the adventures of heroes and kings that take place at them seem to revolve around a lot of drinking and either the dead or evil fairies coming back from the otherworld to wreck some form of havoc. There are various hints that could well suggest human sacrifice as well, but its hard to say for certain. Irish pagan Gods (Lugh on the left?) from the Ulster Museum

Irish pagan Gods (Lugh on the left?) from the Ulster Museum

The tales were written down by medieval Christian monks and could be biased against Paganism. The idea that our ancestors practised human sacrifice is also a slightly controversial idea to some. There are modern neo-pagans who will state that there is no evidence that ancient pagans sacrificed humans. I would argue that there is actually lots. Bog bodies for example exhibit such a degree of overkill that it points to some form of ritual, the only alternative being that for centuries psychopathic killers across northern Europe dispatched their victims using remarkably similar methods. Classical writers like Julius Caesar (again admittedly biased against the non-Roman Celts) all attest that the Druids sacrificed people to their Gods. However its not just neo-pagans who object to this idea. There are plenty of others who seem to find the idea that Irish people would kill other Irish people for religious reasons completely beyond the pale. Personally, while its not definitive, I think the evidence points to the fact that it happened, and that this time of year was particularly associated with it.

One place where Samhain and human sacrifice are explicitly linked is in the worship of the God Crom Cruach. If anyone has heard of Crom these days, the chances are it is as the God worshiped by Conan the Barbarian, either in Robert E Howard’s sword and sandal epics, or in the 1980s movie starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Who could forget such classic cinematic moments this?

But he was in fact a deity worshipped in ancient Ireland. He is, however, a bit of a puzzle. He doesn’t appear in the cannon of Early Irish Literature but in the tales of Saint Patrick, it’s Crom and his ministers who seem to be the main Pagan opposition to the Saint’s mission. The Dindsenchas that tell the lore of the land and the Annals of the Four Masters both talk of a festival at that this time of year which honoured Crom at a gathering in Magh Slécht, which is in modern county Cavan. Worship of Crom in ancient Ireland appears to be associated with a sacred bull, standing stones - an ancient name for a ring of standing stones was a “cromlech”- and, as readers of my novel “The Spear of Crom” will know, human sacrifice. The sources say that at Samhain, first born children were sacrificed to Crom. If true, the terror and horror instilled by what went on that night still echo in the modern Halloween. I think it’s interesting that the Annals of the Four Masters chose to include Crom when other annals don’t. They were compiled in a Friary on the edge of Donegal. Magh Slecht, the centre of Crom worship, and where his standing stone may still lie, is in County Cavan, suggesting that Samhain and Crom were of significance to the ancient people of Ulster. I’ve already written about how a portion of those people later on ended up founding a kingdom across the Irish sea so it should be no surprise that the other place where you find references to Crom is in the Highlands of Scotland. There is a Scottish Gaelic saying recorded in Lochaber that mentions “Domhnaich Crom Dubh” -Black Crom Sunday.So my thesis is that the festival of Samhain, held at this time of the year, was special for the people of Ireland and Ulster in particular. A portion of those folk migrated to what is now Scotland at the beginning of what some call “the Dark Ages” and they took with them the festival and all its associated trappings of death and fear. Time past and Samhain became Halloween, but the festival’s popularity in Scotland carried on. Some of those Scottish folk then migrated (or rather were “planted”) back in Ulster in the 1600s and they brought the tradition back with them, probably finding that the Irish were still celebrating in a similar fashion. A few years later some of those folk -now referred to as “Scots-Irish” - migrated to America and took the festival with them there, where it’s safe to say it was a huge success. I said I believed there were two reasons for the popularity of Halloween with the Scots Irish. The second reason is to do with witches, however that (and the explanation about the severed heads) will have to wait for another post which I’ll put up over the next day or so. In the meantime, if you want a chilling read for Halloween, my new novel set in Victorian Belfast, “The Undead” is available now on Kindle.

Or you can read about Fergus MacAmergin’s battles with the Druids of Crom in my novel “The Spear of Crom”, available on Kindle and in paperback

A turnip lantern

A turnip lanternPerhaps mysterious is why were the Scots and Scots-Irish -almost all staunch Presbyterians- so keen on celebrating this old Celtic festival? Paganism in general and all things Gaelic in particular usually have the same effect on the Scots-Irish that garlic has to vampires. The answer is probably a mixture of a couple of things. The first reason is that they simply always celebrated it, and tradition is a very hard thing to kill.It could be argued that Samhain had particularly significance in the North of Ireland from time immemorial. Samhain, the pre-christian name for the festival was one of the old quarter-days of the year celebrated by the ancient people of Ireland. A word very close to Samhain appears on the 2nd Century AD Coligny Calendar, suggesting that Celtic cousins in Europe celebrated the festival too. There are lots of references in Early Irish Literature to great clan gatherings and festivals being held at this time of year, and the adventures of heroes and kings that take place at them seem to revolve around a lot of drinking and either the dead or evil fairies coming back from the otherworld to wreck some form of havoc. There are various hints that could well suggest human sacrifice as well, but its hard to say for certain.

Irish pagan Gods (Lugh on the left?) from the Ulster Museum

Irish pagan Gods (Lugh on the left?) from the Ulster MuseumThe tales were written down by medieval Christian monks and could be biased against Paganism. The idea that our ancestors practised human sacrifice is also a slightly controversial idea to some. There are modern neo-pagans who will state that there is no evidence that ancient pagans sacrificed humans. I would argue that there is actually lots. Bog bodies for example exhibit such a degree of overkill that it points to some form of ritual, the only alternative being that for centuries psychopathic killers across northern Europe dispatched their victims using remarkably similar methods. Classical writers like Julius Caesar (again admittedly biased against the non-Roman Celts) all attest that the Druids sacrificed people to their Gods. However its not just neo-pagans who object to this idea. There are plenty of others who seem to find the idea that Irish people would kill other Irish people for religious reasons completely beyond the pale. Personally, while its not definitive, I think the evidence points to the fact that it happened, and that this time of year was particularly associated with it.

One place where Samhain and human sacrifice are explicitly linked is in the worship of the God Crom Cruach. If anyone has heard of Crom these days, the chances are it is as the God worshiped by Conan the Barbarian, either in Robert E Howard’s sword and sandal epics, or in the 1980s movie starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Who could forget such classic cinematic moments this?

But he was in fact a deity worshipped in ancient Ireland. He is, however, a bit of a puzzle. He doesn’t appear in the cannon of Early Irish Literature but in the tales of Saint Patrick, it’s Crom and his ministers who seem to be the main Pagan opposition to the Saint’s mission. The Dindsenchas that tell the lore of the land and the Annals of the Four Masters both talk of a festival at that this time of year which honoured Crom at a gathering in Magh Slécht, which is in modern county Cavan. Worship of Crom in ancient Ireland appears to be associated with a sacred bull, standing stones - an ancient name for a ring of standing stones was a “cromlech”- and, as readers of my novel “The Spear of Crom” will know, human sacrifice. The sources say that at Samhain, first born children were sacrificed to Crom. If true, the terror and horror instilled by what went on that night still echo in the modern Halloween. I think it’s interesting that the Annals of the Four Masters chose to include Crom when other annals don’t. They were compiled in a Friary on the edge of Donegal. Magh Slecht, the centre of Crom worship, and where his standing stone may still lie, is in County Cavan, suggesting that Samhain and Crom were of significance to the ancient people of Ulster. I’ve already written about how a portion of those people later on ended up founding a kingdom across the Irish sea so it should be no surprise that the other place where you find references to Crom is in the Highlands of Scotland. There is a Scottish Gaelic saying recorded in Lochaber that mentions “Domhnaich Crom Dubh” -Black Crom Sunday.So my thesis is that the festival of Samhain, held at this time of the year, was special for the people of Ireland and Ulster in particular. A portion of those folk migrated to what is now Scotland at the beginning of what some call “the Dark Ages” and they took with them the festival and all its associated trappings of death and fear. Time past and Samhain became Halloween, but the festival’s popularity in Scotland carried on. Some of those Scottish folk then migrated (or rather were “planted”) back in Ulster in the 1600s and they brought the tradition back with them, probably finding that the Irish were still celebrating in a similar fashion. A few years later some of those folk -now referred to as “Scots-Irish” - migrated to America and took the festival with them there, where it’s safe to say it was a huge success. I said I believed there were two reasons for the popularity of Halloween with the Scots Irish. The second reason is to do with witches, however that (and the explanation about the severed heads) will have to wait for another post which I’ll put up over the next day or so. In the meantime, if you want a chilling read for Halloween, my new novel set in Victorian Belfast, “The Undead” is available now on Kindle.

Or you can read about Fergus MacAmergin’s battles with the Druids of Crom in my novel “The Spear of Crom”, available on Kindle and in paperback

Published on October 28, 2015 02:32

October 18, 2015

The Undead

After much deliberation, I've decided to re-name the book I've been calling "The Frankenstein Testament" to "The Undead". I was never that happy with the other one and I felt it might have put a lot of people off. The Undead is closer to what the book is about. "The Undead" was the original title of Dracula by Bram Stoker (who also toyed with "The Great Undead") and I wanted to evoke that (without for a moment comparing myself to him. With the addition of the title I now pay homage to the three great influences who have given me great pleasure and been an inspiration for this book. The title now nods to Stoker, The key plot driven springs from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and the detective character who investigates the mystery is named Joseph Sheridan, in honour of Joseph Sheridan leFanu, whose supernatural works influenced so many writers, among them Bram Stoker and Stephen King.So hopefully it will be out for Halloween. Watch this space for a suitably chilling read.

Published on October 18, 2015 04:04

September 27, 2015

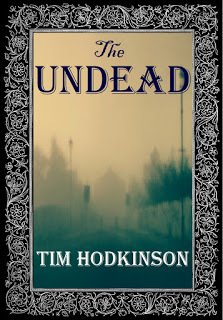

The Castle of Alys de Logan

Some readers of my medieval Irish novels Lions of the Grail and The Waste Land have asked me where is Corainne castle, the home of Alys de Logan? The other castles and forts mentioned in the books are obvious and can still be visited today but Corainne is a bit more obscure. Given that the other locations in the books are real places and the events of the war are historically accurate, is it a real place too?

Firstly, it's probably important to point out that while Savage and Logan are authentic Hiberno-Norman names that belonged to medieval barons of Ulster, Richard and Alys themselves are fictional characters. The site of Alys’s castle can be revealed though. In Lions of the Grail, the Hospitaller tells Edward Bruce that “Vikingsford lough is De Logan land, watched over by the castle at Corainne point.”“Vikingsford”, also known in some Medieval sources as “Wulfrich’s Ford”, is now Larne lough, just North of Carrickfergus in County Antrim and still the port where the ferry from Scotland arrives in Ireland, pretty much following the sea road that Edward Bruce and his army took in 1315. Corainne is an older form of the modern Curran Point, where the ruins of a castle now named “Olderfleet” still stand.

Olderfleet castle ruins

Olderfleet castle ruinsIt’s important to note that, as pointed out in an earlier post about motte and bailey castles in Ulster, that when we say “castle”, in terms of medieval Ireland, most of these buildings were not the moated, curtain-walled, multi-turreted fortress with portcullis and drawbridge that springs to mind when we think of the word castle. The castle of the de Logan’s at Corainne was an early form of the Irish tower house. This was a much more modest affair, suited to the more low level defensive needs of the time.Illustrator JG O'Donoghue recently posted an excellent painting and description of a medieval Irish tower house which you can read it here -https://www.facebook.com/jg.odonoghueillustrator/posts/870153903104669:0

The tower house in the painting is probably slightly bigger than what Alys's would have been like, and she had a wooden palisade rather than a stone wall, but it really gives a great impression of the castle would have looked like when Alys and Galiene were living there, dependent on the loyalty of the few remaining family servants, trying to make ends meet and scratching a living form the potions they made from herbs grown in the garden. The other question I get asked is where was Richard Savage's castle. That will be for another post.

Published on September 27, 2015 04:31

August 5, 2015

Richard Savage rides again

A new adventure of Sir Richard Savage is available, called “The Savage Forest”. The story takes place ten years before the events of “Lions of the Grail”.England, 1305 AD. The Holy Land is lost and the Knights Templar need to find a new purpose. Sir Richard Savage, a young knight of the Order freshly repatriated from the East, is tasked with guarding a convoy of holy treasure through Sherwood Forest, the haunt of the most notorious outlaw in England. As an ambush unfolds, Savage learns that the treasure is more than he bargained for and he is forced to make a choice in a fight that challenges his core beliefs.The tale is a novella (about 23000 words or 73 pages) so makes a short but exciting read.

“The Savage Forest” is now available on Kindle: http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B013GX0C64

“The Savage Forest” is now available on Kindle: http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B013GX0C64

Published on August 05, 2015 13:31

July 24, 2015

New novel - The Frankenstein Testament

I'm very pleased to say that my latest novel, "The Frankenstein Testament" is now available on Kindle and paperback. This one has been ten years in the making this one and it's a bit of a departure from my usual milieu of medieval and ancient historical fiction. While being set in a real historical setting (Victorian Ireland), this one strays into the territory of my other favourite genre - the Gothic novel.The Frankenstein Testament was born from my love of the works of those greats of speculative fiction, Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley and in particular J S LeFanu and I hope it fits somewhere into that tradition. So if you fancy a trip into the fantastic and the horrible, give The Frankenstein Testament a go. As Iron Maiden once sang, "Let me tell you a story to chill the bones..."

Here is the "blurb":

Ireland, 1839. Belfast is a city that is blossoming but already beginning to rot. Amid its crowded streets, linen mills and factories the body snatchers are on the loose and a homicidal maniac is on a killing spree. Witnesses claim that the murderer is an executed criminal who should be dead and buried. Captain Joseph Sheridan, a consulting detective from Dublin who specialises in investigating the supernatural, travels north to probe the mystery. Joining forces with Abraham Harpur, a Belfast policeman and Emily Brunty, a school mistress who wants to be a journalist, they find themselves on the trail of a grief-deranged doctor obsessed with resurrecting the dead.

Kindle edition: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Frankenstein-Testament-Tim-Hodkinson-ebook/dp/B012AYT82Y/

Paperback: http://www.lulu.com/shop/tim-hodkinson/the-frankenstein-testament/paperback/product-22284214.html

Published on July 24, 2015 04:33

July 22, 2015

Now available in paperback - The Waste Land

I'm very pleased to say that my novel "The Waste Land", the sequel to Lions of the Grail, is now available in paperback format. Right now you can get a copy here:http://www.lulu.com/shop/tim-hodkinson/the-waste-land/paperback/product-22283855.html and it will soon be available on Amazon, Barne & Noble etc.

The Waste Land is the second book chronicling the adventures of the knight, Richard Savage and his struggles during the Scottish invasion of Ireland in 1315-18.

1316 AD. Richard Savage thought he had left the war in Ireland behind but Edward Bruce will not let him just walk away. He wants the Grail Savage stole from him back. To force Savage to return it he takes what is dear to him - his daughter Galiene. Savage must return to Ireland, but the seas are ruled by a ruthless pirate. Ireland is now a land devastated by war and decimated by famine. Carrickfergus castle stands besieged by the Scottish army, the garrison on its knees, and Scottish invaders ravage the countryside. Savage and Alys re-unite with old comrades on a desperate raid to save their daughter and turn the tide of war

The Waste Land is the second book chronicling the adventures of the knight, Richard Savage and his struggles during the Scottish invasion of Ireland in 1315-18.

1316 AD. Richard Savage thought he had left the war in Ireland behind but Edward Bruce will not let him just walk away. He wants the Grail Savage stole from him back. To force Savage to return it he takes what is dear to him - his daughter Galiene. Savage must return to Ireland, but the seas are ruled by a ruthless pirate. Ireland is now a land devastated by war and decimated by famine. Carrickfergus castle stands besieged by the Scottish army, the garrison on its knees, and Scottish invaders ravage the countryside. Savage and Alys re-unite with old comrades on a desperate raid to save their daughter and turn the tide of war

Published on July 22, 2015 09:21

July 7, 2015

Medieval Pirates - the tale of Tavish Dhu

Last Saturday, Portrush in Northern Ireland held a highly enjoyable pirate festival in honour of Tavish Dhu, a Scottish pirate who once haunted the coast. The theme of this year’s festival was “700 years dead” as 2015 marks the seventh century since the outbreak of the war that resulted in Tavish coming to a sticky end. Those who have read my book “The Waste Land” will recognise Tavish as the Pirate who captures Alys and who MacHuylin just manages to escape from.

my children and the modern "Tavish Dhu"

my children and the modern "Tavish Dhu"

The festival was a great day out for the whole family, with a parade, ghosts a battle and twin pirate ships that sailed around the town. Understandably, the sabres, flintlocks, tri-cornered hats and frock coats on display along with bottles of rum and much “Yo Ho Ho”-ing owed more to the 17th Century golden age of piracy than Tavish’s medieval timeframe - and the amount of eyeliner being used owed a lot to Johnny Depp’s Captain Jack Sparrow- but its safe to say that is what people like and that's what they think of when they hear the word ‘pirate’ rather than what an American literary agent once described to me as “an obscure Irish war 700 years ago that involved no one that anyone has heard of.”Pirates have been around since the dawn of shipping. Piracy is probably the second oldest profession in the world. Julius Caesar was held hostage by pirates in 75 BC (he later had them all crucified). There’s some academic opinion that one of the words the Romans used for the Irish -Scotti - actually means pirate, because they mainly knew them through their raiding activities on the British coast. Before they started settling down in the 5th Century AD and making their residence more permanent, the Anglo-Saxons were regarded as pirates by the Britons. The word “viking” can been seen as synonymous with pirate in many ways. With the middle ages, we start to see some of the first truly memorable pirates, and Tavish Dhu takes a modest place among them. Probably the most famous was Eustace the Monk. This colourful character deserves a whole post all to himself. At one time a Benedictine monk, reputedly a black magician, Eustace terrorised the English channel between 1202 and 1217 AD. Eustace also embodied another tradition among pirates that is seldom discussed. One of the appeals of pirates that makes us see them as romantic heroes rather than the brutal thieves they really were, is the perception of them being individuals who stand outside of society, a thorn in the side of oppressive governments in less free times. In reality, many famous pirates were in the employ of governments and given the task of harassing enemy shipping in a deniable way employing tactics that might bring shame or legal repercussions. One man’s naval hero is another man’s pirate: Ask the Spanish what they think of Sir Francis Drake if you want a good example. The role of the privateer -a ship captain who takes a commission from the crown or a government to attack enemy ships (and split the resulting loot with said powers that be) in a private capacity- is one that was played by many famous names in pirate history: Captain Kid, Captain Henry Morgan, Francis Drake, John Hawkins, (Sir) Walter Raleigh all took “letters of marque” as privateers. Eustace was employed by the English crown to attack French ships in the English channel, which he did with great success from his base in Castle Cornet in Guernsey for many years. In 1212, as England descended into the chaos of civil war, he decided to switch sides and took commission from the French, at one point ferrying the French Prince and his men across the channel for a briefly successful invasion of Southern England. The English responded and clashed with Eustace’s fleet at the battle of Dover in August 1217. The English, led by Hubert de Burgh (another scion of the de Burgh family who Tavish would clash with a century later). Eustace and the French had the upper hand and looked like they were about to win when the English chose the nuclear (or rather the chemical) option and released lime powder into the wind, blinding the downwind French sailors. Eustace was captured and this man who had once negotiated with Kings offered huge rewards in ransom for his life. Unfortunately for him his past deeds caught up with him and the English sailors hated him so much all they offered him was the choice of his execution site. Eustace comes to a sticky end

Eustace comes to a sticky end

Another pirate from this time worthy of special mention is Jean de Clisson, also known as the Lioness of Brittany. In the 1340s, following the execution of her husband, Jean took it on herself to wage a personal war of revenge against the French crown. Following several massacres and a bloody onslaught on land, the fighting finally went against her and she fled to England. With the help of Edward III of England, Jean equipped three warships and set off the continue her personal vendetta, this time at sea. Displaying a chilling dramatic flair also shown by later pirates like William Teach or the man who thought it would be a good idea to put an air raid siren in the nose of a Stuka dive bomber, Jean had her ships painted black and the sails dyed red. The “Black Fleet” as it became known, then patrolled the English Channel hunting down French ships. Their tactic was to kill the entire crew except for one or two witnesses who were ordered to take the news to the French King.Unlike most other pirates, after 13 years of piracy, Jean eventually retired, settled down and died in bed.Which bring us to Tavish. Tavish appears in several guises in the chronicles about the war of Edward Bruce in Ireland (1315 -1318 AD). If you want to know more about this particularly brutal war see my previous post here:http://timhodkinson.blogspot.co.uk/2015/05/on-700th-anniversary-of-scottish.html In 1314, Robert Bruce famously defeated proud Edward’s army at the battle of Bannockburn, sending the English out of Scotland and creating the fledgling state that would become modern Scotland. He had an immediate problem however, in that the English had a fleet of ships, and so could continue to harass him by sea, if not by land. Scotland did not have a readily available navy. Worse than that, the Kings of the Western Isles and their cousins in Ireland who did command fleets of galleys were actively opposed to him. King Robert turned to the tactic of employing a privateer, and Tavish took the commission. How he got his ships is now unknown, but he soon put them in the employ of the Scots. Similarly his origins are obscure. One annal calls him “Thomas of Down (an Dunn)” and a history book from the last century thought this meant he was from Downpatrick. Another chronicle calls him Thomas Dunn, though these are undoubtedly mistranslations by English speaking writers of the Gaelic word “Dubh” - Black. The etymology and connection becomes clearer with his first name, Tavish being the Scottish version of the name “Thomas”. Tavish Dubh -”Black Tom”- is an excellent nom de guerre for a pirate, every bit as chilling as Blackbeard. His main activity was piracy in the Irish sea, directed at English ships. His fleet also acted as a a de-facto navy for the Scots, ferrying Edward Bruce’s invasion force from Ayr to Larne in Ireland in May of 1315. He enters the Irish annals when he is mentioned as taking four ships of the Earl of Ulster just off Portrush in County. The ships were were laden with supplies to help the English war effort including food which was a precious commodity in what was a time of not just war but also famine. Portrush now claims Tavish as their own, running their pirate festival in his honour. There are several local legends around him. Dhuvarren, the site of the railway station and a caravan park, are supposedly named after him. A book from the 19th Century, entitled “Sketches of County Antrim” relates this about the Skerries, the set of islands just off the East Strand in Portrush:“The islet furthest east is called Island Dubh. It is probable that it is named after Tavish Dubh, a pirate, who once frequented the Skerries.”-(thanks to my good friend Jean Clayton for bringing this to my attention) Skerries off PortrushThat he knew the area is undoubted. John Barbour wrote an account of Edward Bruce’s Irish invasion within living memory of it happening. Edward’s army got into difficulty at Coleraine and Tavish sailed up the mouth of the Bann river to rescue him, ferrying Edward’s soldiers across the river and out of the clutches of the army of the Earl of Ulster.English chroniclers describe Tavish as "a perpetrator of depredations on the sea" and "a cruel pirate", which is understandable as they were on the wrong end of his activities, however he must not have been a very nice person as John Barbour, writing from the Scottish point of view also calls Tavish a “Scumer of the Se” - scum of the sea. Tavish then extended his activities. He raided Holyhead in Anglesey with four galleys and captured a laden cargo ship, the "James" of Caernarvon, it is said after receiving intelligence from a local "rhingyl" (official) who may have sent out a boat to advise him of the opportunity. The Welsh then rose in revolt and Edward II was forced to return to Wales the troops he had recruited to send against Scotland. Now taking the threat of Tavish and the Scots in Ireland seriously, Edward recalled the Cinque Ports fleet as well. When the King of France protested this withdrawal of support against the Flemings, Edward II claimed all his ships were needed for the defence of Ireland.Edward II had had enough. He ordered a Geoffrey de Modiworthe to construct a special ship and go after Tavish. This was a 140 man galley, very large for those days in the Irish Sea, and probably the fastest vessel in those waters. Even with that, though, they could not catch the pirate and it took an Irish noblemen, John D’Athy, to take to the seas and finally end Tavish’s reign of terror. In July of 1317, John and his ships intercepted Tavish and his fleet at sea. A sea battle ensued in which 40 of the privateers are said to have been killed and Tavish captured.Sketches of County Antrim says about the Skerries at Portrush that Tavish “died in his ship here, and was buried on the island, but the place of his grave is unknown”. Whether or not that was true I don’t know. D’Athy cut his head off and sent it to Dublin and that was the end of the pirate’s adventures. The loss of the ships spelt doom for Edward Bruce’s invasion of Ireland. However for his brother Robert, Tavish was only ever a tactical stopgap. By that time he was already building his own navy,having instigated a ship building program on the Clyde, a tradition that would continue for most of the next 700 years.Perhaps Tavish’s last stand was at the Skerries. Perhaps his treasure is still buried there too. It would make a great story if it was.

Skerries off PortrushThat he knew the area is undoubted. John Barbour wrote an account of Edward Bruce’s Irish invasion within living memory of it happening. Edward’s army got into difficulty at Coleraine and Tavish sailed up the mouth of the Bann river to rescue him, ferrying Edward’s soldiers across the river and out of the clutches of the army of the Earl of Ulster.English chroniclers describe Tavish as "a perpetrator of depredations on the sea" and "a cruel pirate", which is understandable as they were on the wrong end of his activities, however he must not have been a very nice person as John Barbour, writing from the Scottish point of view also calls Tavish a “Scumer of the Se” - scum of the sea. Tavish then extended his activities. He raided Holyhead in Anglesey with four galleys and captured a laden cargo ship, the "James" of Caernarvon, it is said after receiving intelligence from a local "rhingyl" (official) who may have sent out a boat to advise him of the opportunity. The Welsh then rose in revolt and Edward II was forced to return to Wales the troops he had recruited to send against Scotland. Now taking the threat of Tavish and the Scots in Ireland seriously, Edward recalled the Cinque Ports fleet as well. When the King of France protested this withdrawal of support against the Flemings, Edward II claimed all his ships were needed for the defence of Ireland.Edward II had had enough. He ordered a Geoffrey de Modiworthe to construct a special ship and go after Tavish. This was a 140 man galley, very large for those days in the Irish Sea, and probably the fastest vessel in those waters. Even with that, though, they could not catch the pirate and it took an Irish noblemen, John D’Athy, to take to the seas and finally end Tavish’s reign of terror. In July of 1317, John and his ships intercepted Tavish and his fleet at sea. A sea battle ensued in which 40 of the privateers are said to have been killed and Tavish captured.Sketches of County Antrim says about the Skerries at Portrush that Tavish “died in his ship here, and was buried on the island, but the place of his grave is unknown”. Whether or not that was true I don’t know. D’Athy cut his head off and sent it to Dublin and that was the end of the pirate’s adventures. The loss of the ships spelt doom for Edward Bruce’s invasion of Ireland. However for his brother Robert, Tavish was only ever a tactical stopgap. By that time he was already building his own navy,having instigated a ship building program on the Clyde, a tradition that would continue for most of the next 700 years.Perhaps Tavish’s last stand was at the Skerries. Perhaps his treasure is still buried there too. It would make a great story if it was.

Tavish

Tavish

my children and the modern "Tavish Dhu"

my children and the modern "Tavish Dhu"The festival was a great day out for the whole family, with a parade, ghosts a battle and twin pirate ships that sailed around the town. Understandably, the sabres, flintlocks, tri-cornered hats and frock coats on display along with bottles of rum and much “Yo Ho Ho”-ing owed more to the 17th Century golden age of piracy than Tavish’s medieval timeframe - and the amount of eyeliner being used owed a lot to Johnny Depp’s Captain Jack Sparrow- but its safe to say that is what people like and that's what they think of when they hear the word ‘pirate’ rather than what an American literary agent once described to me as “an obscure Irish war 700 years ago that involved no one that anyone has heard of.”Pirates have been around since the dawn of shipping. Piracy is probably the second oldest profession in the world. Julius Caesar was held hostage by pirates in 75 BC (he later had them all crucified). There’s some academic opinion that one of the words the Romans used for the Irish -Scotti - actually means pirate, because they mainly knew them through their raiding activities on the British coast. Before they started settling down in the 5th Century AD and making their residence more permanent, the Anglo-Saxons were regarded as pirates by the Britons. The word “viking” can been seen as synonymous with pirate in many ways. With the middle ages, we start to see some of the first truly memorable pirates, and Tavish Dhu takes a modest place among them. Probably the most famous was Eustace the Monk. This colourful character deserves a whole post all to himself. At one time a Benedictine monk, reputedly a black magician, Eustace terrorised the English channel between 1202 and 1217 AD. Eustace also embodied another tradition among pirates that is seldom discussed. One of the appeals of pirates that makes us see them as romantic heroes rather than the brutal thieves they really were, is the perception of them being individuals who stand outside of society, a thorn in the side of oppressive governments in less free times. In reality, many famous pirates were in the employ of governments and given the task of harassing enemy shipping in a deniable way employing tactics that might bring shame or legal repercussions. One man’s naval hero is another man’s pirate: Ask the Spanish what they think of Sir Francis Drake if you want a good example. The role of the privateer -a ship captain who takes a commission from the crown or a government to attack enemy ships (and split the resulting loot with said powers that be) in a private capacity- is one that was played by many famous names in pirate history: Captain Kid, Captain Henry Morgan, Francis Drake, John Hawkins, (Sir) Walter Raleigh all took “letters of marque” as privateers. Eustace was employed by the English crown to attack French ships in the English channel, which he did with great success from his base in Castle Cornet in Guernsey for many years. In 1212, as England descended into the chaos of civil war, he decided to switch sides and took commission from the French, at one point ferrying the French Prince and his men across the channel for a briefly successful invasion of Southern England. The English responded and clashed with Eustace’s fleet at the battle of Dover in August 1217. The English, led by Hubert de Burgh (another scion of the de Burgh family who Tavish would clash with a century later). Eustace and the French had the upper hand and looked like they were about to win when the English chose the nuclear (or rather the chemical) option and released lime powder into the wind, blinding the downwind French sailors. Eustace was captured and this man who had once negotiated with Kings offered huge rewards in ransom for his life. Unfortunately for him his past deeds caught up with him and the English sailors hated him so much all they offered him was the choice of his execution site.

Eustace comes to a sticky end

Eustace comes to a sticky endAnother pirate from this time worthy of special mention is Jean de Clisson, also known as the Lioness of Brittany. In the 1340s, following the execution of her husband, Jean took it on herself to wage a personal war of revenge against the French crown. Following several massacres and a bloody onslaught on land, the fighting finally went against her and she fled to England. With the help of Edward III of England, Jean equipped three warships and set off the continue her personal vendetta, this time at sea. Displaying a chilling dramatic flair also shown by later pirates like William Teach or the man who thought it would be a good idea to put an air raid siren in the nose of a Stuka dive bomber, Jean had her ships painted black and the sails dyed red. The “Black Fleet” as it became known, then patrolled the English Channel hunting down French ships. Their tactic was to kill the entire crew except for one or two witnesses who were ordered to take the news to the French King.Unlike most other pirates, after 13 years of piracy, Jean eventually retired, settled down and died in bed.Which bring us to Tavish. Tavish appears in several guises in the chronicles about the war of Edward Bruce in Ireland (1315 -1318 AD). If you want to know more about this particularly brutal war see my previous post here:http://timhodkinson.blogspot.co.uk/2015/05/on-700th-anniversary-of-scottish.html In 1314, Robert Bruce famously defeated proud Edward’s army at the battle of Bannockburn, sending the English out of Scotland and creating the fledgling state that would become modern Scotland. He had an immediate problem however, in that the English had a fleet of ships, and so could continue to harass him by sea, if not by land. Scotland did not have a readily available navy. Worse than that, the Kings of the Western Isles and their cousins in Ireland who did command fleets of galleys were actively opposed to him. King Robert turned to the tactic of employing a privateer, and Tavish took the commission. How he got his ships is now unknown, but he soon put them in the employ of the Scots. Similarly his origins are obscure. One annal calls him “Thomas of Down (an Dunn)” and a history book from the last century thought this meant he was from Downpatrick. Another chronicle calls him Thomas Dunn, though these are undoubtedly mistranslations by English speaking writers of the Gaelic word “Dubh” - Black. The etymology and connection becomes clearer with his first name, Tavish being the Scottish version of the name “Thomas”. Tavish Dubh -”Black Tom”- is an excellent nom de guerre for a pirate, every bit as chilling as Blackbeard. His main activity was piracy in the Irish sea, directed at English ships. His fleet also acted as a a de-facto navy for the Scots, ferrying Edward Bruce’s invasion force from Ayr to Larne in Ireland in May of 1315. He enters the Irish annals when he is mentioned as taking four ships of the Earl of Ulster just off Portrush in County. The ships were were laden with supplies to help the English war effort including food which was a precious commodity in what was a time of not just war but also famine. Portrush now claims Tavish as their own, running their pirate festival in his honour. There are several local legends around him. Dhuvarren, the site of the railway station and a caravan park, are supposedly named after him. A book from the 19th Century, entitled “Sketches of County Antrim” relates this about the Skerries, the set of islands just off the East Strand in Portrush:“The islet furthest east is called Island Dubh. It is probable that it is named after Tavish Dubh, a pirate, who once frequented the Skerries.”-(thanks to my good friend Jean Clayton for bringing this to my attention)

Skerries off PortrushThat he knew the area is undoubted. John Barbour wrote an account of Edward Bruce’s Irish invasion within living memory of it happening. Edward’s army got into difficulty at Coleraine and Tavish sailed up the mouth of the Bann river to rescue him, ferrying Edward’s soldiers across the river and out of the clutches of the army of the Earl of Ulster.English chroniclers describe Tavish as "a perpetrator of depredations on the sea" and "a cruel pirate", which is understandable as they were on the wrong end of his activities, however he must not have been a very nice person as John Barbour, writing from the Scottish point of view also calls Tavish a “Scumer of the Se” - scum of the sea. Tavish then extended his activities. He raided Holyhead in Anglesey with four galleys and captured a laden cargo ship, the "James" of Caernarvon, it is said after receiving intelligence from a local "rhingyl" (official) who may have sent out a boat to advise him of the opportunity. The Welsh then rose in revolt and Edward II was forced to return to Wales the troops he had recruited to send against Scotland. Now taking the threat of Tavish and the Scots in Ireland seriously, Edward recalled the Cinque Ports fleet as well. When the King of France protested this withdrawal of support against the Flemings, Edward II claimed all his ships were needed for the defence of Ireland.Edward II had had enough. He ordered a Geoffrey de Modiworthe to construct a special ship and go after Tavish. This was a 140 man galley, very large for those days in the Irish Sea, and probably the fastest vessel in those waters. Even with that, though, they could not catch the pirate and it took an Irish noblemen, John D’Athy, to take to the seas and finally end Tavish’s reign of terror. In July of 1317, John and his ships intercepted Tavish and his fleet at sea. A sea battle ensued in which 40 of the privateers are said to have been killed and Tavish captured.Sketches of County Antrim says about the Skerries at Portrush that Tavish “died in his ship here, and was buried on the island, but the place of his grave is unknown”. Whether or not that was true I don’t know. D’Athy cut his head off and sent it to Dublin and that was the end of the pirate’s adventures. The loss of the ships spelt doom for Edward Bruce’s invasion of Ireland. However for his brother Robert, Tavish was only ever a tactical stopgap. By that time he was already building his own navy,having instigated a ship building program on the Clyde, a tradition that would continue for most of the next 700 years.Perhaps Tavish’s last stand was at the Skerries. Perhaps his treasure is still buried there too. It would make a great story if it was.

Skerries off PortrushThat he knew the area is undoubted. John Barbour wrote an account of Edward Bruce’s Irish invasion within living memory of it happening. Edward’s army got into difficulty at Coleraine and Tavish sailed up the mouth of the Bann river to rescue him, ferrying Edward’s soldiers across the river and out of the clutches of the army of the Earl of Ulster.English chroniclers describe Tavish as "a perpetrator of depredations on the sea" and "a cruel pirate", which is understandable as they were on the wrong end of his activities, however he must not have been a very nice person as John Barbour, writing from the Scottish point of view also calls Tavish a “Scumer of the Se” - scum of the sea. Tavish then extended his activities. He raided Holyhead in Anglesey with four galleys and captured a laden cargo ship, the "James" of Caernarvon, it is said after receiving intelligence from a local "rhingyl" (official) who may have sent out a boat to advise him of the opportunity. The Welsh then rose in revolt and Edward II was forced to return to Wales the troops he had recruited to send against Scotland. Now taking the threat of Tavish and the Scots in Ireland seriously, Edward recalled the Cinque Ports fleet as well. When the King of France protested this withdrawal of support against the Flemings, Edward II claimed all his ships were needed for the defence of Ireland.Edward II had had enough. He ordered a Geoffrey de Modiworthe to construct a special ship and go after Tavish. This was a 140 man galley, very large for those days in the Irish Sea, and probably the fastest vessel in those waters. Even with that, though, they could not catch the pirate and it took an Irish noblemen, John D’Athy, to take to the seas and finally end Tavish’s reign of terror. In July of 1317, John and his ships intercepted Tavish and his fleet at sea. A sea battle ensued in which 40 of the privateers are said to have been killed and Tavish captured.Sketches of County Antrim says about the Skerries at Portrush that Tavish “died in his ship here, and was buried on the island, but the place of his grave is unknown”. Whether or not that was true I don’t know. D’Athy cut his head off and sent it to Dublin and that was the end of the pirate’s adventures. The loss of the ships spelt doom for Edward Bruce’s invasion of Ireland. However for his brother Robert, Tavish was only ever a tactical stopgap. By that time he was already building his own navy,having instigated a ship building program on the Clyde, a tradition that would continue for most of the next 700 years.Perhaps Tavish’s last stand was at the Skerries. Perhaps his treasure is still buried there too. It would make a great story if it was.

Tavish

Tavish

Published on July 07, 2015 13:33

July 4, 2015

Pirates off Portrush

If you have read "The Waste Land", the sequel to Lions of the Grail, then you will know the pirate Tavish Dhu. There is a whole festival about him today in Portrush, which was near a former liar of his. It looks like it will be a great day for all the family.

Details here:

https://www.facebook.com/PiratesOffPortrush?pnref=story

Details here:

https://www.facebook.com/PiratesOffPortrush?pnref=story

Published on July 04, 2015 03:25

June 11, 2015

New Novel - the Frankenstein Testament

I have finished a new novel finished. This one is a bit of a departure from my normal world of medieval/ancient historical fiction as its a Gothic horror story set in Victorian Belfast.

If anyone is interested in taking a peek at the opening chapters, it's currently entered into this months "Fated Paradox" competition on Inkitt.

I'm really interested to hear what people think, good or bad. If you like it, please feel free to vote for it in the competition smile emoticon

The link is here: http://www.inkitt.com/stories/14924

If anyone is interested in taking a peek at the opening chapters, it's currently entered into this months "Fated Paradox" competition on Inkitt.

I'm really interested to hear what people think, good or bad. If you like it, please feel free to vote for it in the competition smile emoticon

The link is here: http://www.inkitt.com/stories/14924

Published on June 11, 2015 01:01