Tim Hodkinson's Blog, page 3

December 23, 2016

A Medieval Christmas

My novels Lions of the Grail and The Waste land take place in medieval Ireland and, as Christmas time approaches, sometimes I'm asked what Christmas would have been like for Richard Savage and the other characters from the books in their time.

Most people are aware that Christmas would have been different in medieval times. However a lot of our modern traditions reach right back to at least seven hundred years ago, perhaps even further. However, as is often said, “the past is a different country”, and they can appear in slightly different guises. I’ve written before about the rather frightening Nordic Christmas traditions but this post will concentrate on what was going on seven centuries ago in British Isles at this time of year. We are lucky enough to have a picture of what Christmas was like, at least for the elite of society, the lords and ladies in their castles, as a unique piece of writing that includes these details has survived.

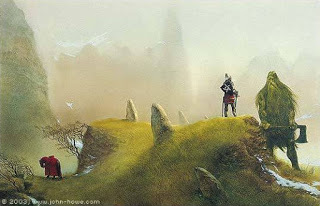

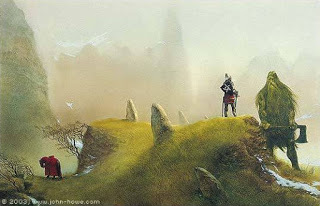

The poem now known as “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” is an interesting piece of writing in itself. It’s written in an ancient English metre and rhyme scheme that even in the 1300s was considered old fashioned. It contains curious elements of folk tales, Christianity, what looks like magic and what may be a portrayal of an old pagan spirit of the forest. It’s one of my favourite pieces of medieval writing and it takes place during Christmastime.

To be specific, it spans a year and covers two Christmases. One at the court of King Arthur and one at the castle of a mysterious nobleman, Bertilak de Hautdessert, somewhere in the north of England. While full of legendary and mythical elements and set in the Arthurian world, like most medieval writers the now-unknown poet portrayed all these events very much as they appeared in his own time. The castles, the armour and the fashions both of hair and dress are very much of the later Fourteenth Century, as opposed to the dark ages when Arthur (if he really did exist) would have ruled.PresentsFrom the poem, it seems that people in the 1300s gave each other presents at this time of the year too. The interesting thing is that they seem to have exchanged them on New Year’s Day, rather than Christmas Day. These gifts, delivered by hand, were called handsels and it seems to have been a tradition that may go all the way back to anglo-saxon times and survived in Scotland and the north of England until relatively recently.

Feasting (and drinking)Like in modern times, it seems that Christmas was also a time for over-indulgence. As you would expect of medieval barons, there is lots of feasting in the poem. The feasting at Arthur’s Court in Camelot lasts “ful fiften dayes,” (15 days). This reflects the old tradition of feasting and merry making (“alle þe mete and þe mirþe”) right through the twelve days of Christmas, culminating in Twelfth Night (5th January) which was still a night of festivities in Shakespeare’s day. Being from hundreds of years before the arrival of turkey or potatoes on these shores from the New World, what is eaten in Gawain and the Green Knight is different to what we have now. There is venison and the ancestor of our Christmas ham, wild boar, hunted during the day by the lords and feasted on in the evening. These were accompanied by potages and stews, all heavily seasoned. Generally, they were eating very well:

“Dayntés dryuen þerwyth of ful dere metes,Foysoun of þe fresche, and on so fele dischesÞat pine to fynde þe place þe peple biforneFor to sette þe sylueren þat sere sewes haldenon clothe.”

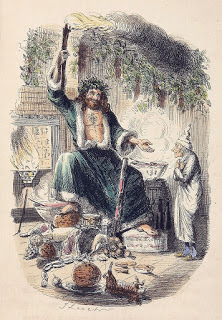

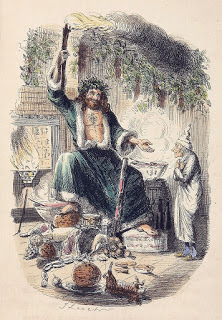

[Roughly translated: Dainties of delicious meats, an abundance of freshest foods in so many dishes that there was no room to set them on the table].Christmas Eve is supposed to be a fast, so no meat. However as fish were not regarded as meat, Gawain finds himself offered an abundance of fish at Bertilak’s castle on Christmas Eve, some baked in bread, some grilled, some boiled some stewed and spiced. Fish is still the traditional Christmas Eve dish for some today, for example Mary Berry enjoys fish pie on the 24th of December.All this is accompanied by gallons of “Good ber and bryȝt wyn boþe” [both good beer and bright wine].Carols and gamesCarols are mentioned in the poem as well, though in medieval times these were dancing as well as singing. While the evenings are passed dancing and feasting, the days are full of hunting and games. There seem to have been a lot of games, and often these were quite active, perhaps even risky. There are tournaments that the knights take part in, and more gentle indoor games as well. These games seem to have an element of risk or chance to them, with wagers and betting involved. In the poem Lord Bertilak puts his rich, ermine lined hood on top of a spear and holds it aloft, offering it as a prize for everyone to compete for in a competition to find who can “make the most merry.”Santa?Generally, our medieval ancestors (the rich ones at least) seem to have put our modern over-indulgence into the shade but there are a lot of things about their Christmas that are familiar. One thing that we might think is missing is Santa Claus. Where is the “jolly old elf” in his red and white suit? As most folk will know, Santa probably got his modern garb from an advert for Coca Cola sometime in the 1930s. Before that, “Father Christmas” as he was also known, tended to be depicted as clad in green, with holly around his head. Perhaps the most famous example is this one from the 1843 edition of “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens: There is much debate over the nature of the Green Knight in the medieval poem. He is a weird creature, often described as perhaps a pagan divinity or that representation of fertility, the Green Man. However when you consider the description of the fearsome creature who invades Camelot at Christmas it’s obvious who he is. He is clad entirely in green and gold. Even his skin is green. He is not so much a “jolly old elf”, as a “half etayn” (half-Yettin, the name that survived in northern English for the Norse jötunn, their supernatural giants). In one hand he has a huge axe but in the other is a bow of holly. He comes at Christmastime to test the Knights of the Round Table on their chivalric behaviour, good or bad: It’s Father Christmas.

There is much debate over the nature of the Green Knight in the medieval poem. He is a weird creature, often described as perhaps a pagan divinity or that representation of fertility, the Green Man. However when you consider the description of the fearsome creature who invades Camelot at Christmas it’s obvious who he is. He is clad entirely in green and gold. Even his skin is green. He is not so much a “jolly old elf”, as a “half etayn” (half-Yettin, the name that survived in northern English for the Norse jötunn, their supernatural giants). In one hand he has a huge axe but in the other is a bow of holly. He comes at Christmastime to test the Knights of the Round Table on their chivalric behaviour, good or bad: It’s Father Christmas.

Most people are aware that Christmas would have been different in medieval times. However a lot of our modern traditions reach right back to at least seven hundred years ago, perhaps even further. However, as is often said, “the past is a different country”, and they can appear in slightly different guises. I’ve written before about the rather frightening Nordic Christmas traditions but this post will concentrate on what was going on seven centuries ago in British Isles at this time of year. We are lucky enough to have a picture of what Christmas was like, at least for the elite of society, the lords and ladies in their castles, as a unique piece of writing that includes these details has survived.

The poem now known as “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” is an interesting piece of writing in itself. It’s written in an ancient English metre and rhyme scheme that even in the 1300s was considered old fashioned. It contains curious elements of folk tales, Christianity, what looks like magic and what may be a portrayal of an old pagan spirit of the forest. It’s one of my favourite pieces of medieval writing and it takes place during Christmastime.

To be specific, it spans a year and covers two Christmases. One at the court of King Arthur and one at the castle of a mysterious nobleman, Bertilak de Hautdessert, somewhere in the north of England. While full of legendary and mythical elements and set in the Arthurian world, like most medieval writers the now-unknown poet portrayed all these events very much as they appeared in his own time. The castles, the armour and the fashions both of hair and dress are very much of the later Fourteenth Century, as opposed to the dark ages when Arthur (if he really did exist) would have ruled.PresentsFrom the poem, it seems that people in the 1300s gave each other presents at this time of the year too. The interesting thing is that they seem to have exchanged them on New Year’s Day, rather than Christmas Day. These gifts, delivered by hand, were called handsels and it seems to have been a tradition that may go all the way back to anglo-saxon times and survived in Scotland and the north of England until relatively recently.

Feasting (and drinking)Like in modern times, it seems that Christmas was also a time for over-indulgence. As you would expect of medieval barons, there is lots of feasting in the poem. The feasting at Arthur’s Court in Camelot lasts “ful fiften dayes,” (15 days). This reflects the old tradition of feasting and merry making (“alle þe mete and þe mirþe”) right through the twelve days of Christmas, culminating in Twelfth Night (5th January) which was still a night of festivities in Shakespeare’s day. Being from hundreds of years before the arrival of turkey or potatoes on these shores from the New World, what is eaten in Gawain and the Green Knight is different to what we have now. There is venison and the ancestor of our Christmas ham, wild boar, hunted during the day by the lords and feasted on in the evening. These were accompanied by potages and stews, all heavily seasoned. Generally, they were eating very well:

“Dayntés dryuen þerwyth of ful dere metes,Foysoun of þe fresche, and on so fele dischesÞat pine to fynde þe place þe peple biforneFor to sette þe sylueren þat sere sewes haldenon clothe.”

[Roughly translated: Dainties of delicious meats, an abundance of freshest foods in so many dishes that there was no room to set them on the table].Christmas Eve is supposed to be a fast, so no meat. However as fish were not regarded as meat, Gawain finds himself offered an abundance of fish at Bertilak’s castle on Christmas Eve, some baked in bread, some grilled, some boiled some stewed and spiced. Fish is still the traditional Christmas Eve dish for some today, for example Mary Berry enjoys fish pie on the 24th of December.All this is accompanied by gallons of “Good ber and bryȝt wyn boþe” [both good beer and bright wine].Carols and gamesCarols are mentioned in the poem as well, though in medieval times these were dancing as well as singing. While the evenings are passed dancing and feasting, the days are full of hunting and games. There seem to have been a lot of games, and often these were quite active, perhaps even risky. There are tournaments that the knights take part in, and more gentle indoor games as well. These games seem to have an element of risk or chance to them, with wagers and betting involved. In the poem Lord Bertilak puts his rich, ermine lined hood on top of a spear and holds it aloft, offering it as a prize for everyone to compete for in a competition to find who can “make the most merry.”Santa?Generally, our medieval ancestors (the rich ones at least) seem to have put our modern over-indulgence into the shade but there are a lot of things about their Christmas that are familiar. One thing that we might think is missing is Santa Claus. Where is the “jolly old elf” in his red and white suit? As most folk will know, Santa probably got his modern garb from an advert for Coca Cola sometime in the 1930s. Before that, “Father Christmas” as he was also known, tended to be depicted as clad in green, with holly around his head. Perhaps the most famous example is this one from the 1843 edition of “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens:

There is much debate over the nature of the Green Knight in the medieval poem. He is a weird creature, often described as perhaps a pagan divinity or that representation of fertility, the Green Man. However when you consider the description of the fearsome creature who invades Camelot at Christmas it’s obvious who he is. He is clad entirely in green and gold. Even his skin is green. He is not so much a “jolly old elf”, as a “half etayn” (half-Yettin, the name that survived in northern English for the Norse jötunn, their supernatural giants). In one hand he has a huge axe but in the other is a bow of holly. He comes at Christmastime to test the Knights of the Round Table on their chivalric behaviour, good or bad: It’s Father Christmas.

There is much debate over the nature of the Green Knight in the medieval poem. He is a weird creature, often described as perhaps a pagan divinity or that representation of fertility, the Green Man. However when you consider the description of the fearsome creature who invades Camelot at Christmas it’s obvious who he is. He is clad entirely in green and gold. Even his skin is green. He is not so much a “jolly old elf”, as a “half etayn” (half-Yettin, the name that survived in northern English for the Norse jötunn, their supernatural giants). In one hand he has a huge axe but in the other is a bow of holly. He comes at Christmastime to test the Knights of the Round Table on their chivalric behaviour, good or bad: It’s Father Christmas.

Published on December 23, 2016 00:31

December 8, 2016

Hygge – the return of an old friend?

Much is being made these days about the so-called “untranslatable” word

hygge

that appears to be radiating across the North Sea from Denmark and into the consciousness of the anglo-centric world. From “mindfulness”, “being”, “centeredness” to “cozy joy” and “family life, and friendship”, a variety of commentators have attempted to express the meaning of this Scandinavian concept.

Mention of it even made its way onto Simon Mayo show on BBC Radio 2 today. Hipsters and trend setters will say its filling some sort of gap in our psyche that the English language somehow cannot express , though a recent article in the Guardian came close to hitting the mark with the comment that “Hygge may be quintessentially Danish, but there is something utterly British about the nostalgic longing for the simple accoutrements of an earlier time”.

Perhaps the reason for the sudden recognition of all things hygge is simply a realisation that we are peering at an old friend. Like when you spot someone across a crowded street in a strange city and think you know them, only to realise that against the odds they are actually your cousin, I believe the embracing of the concept of hygge is just such a remembrance of things lost in the rabbit holes of time, but perhaps not so far lost as to still be recognisable.

The thing is, this is not the first time that this word had made this exact journey. Today it’s carried by the internet and the media but fifteen hundred years ago it was carried from Jutland on rowed longships by invaders who also brought a new language to these islands. Not Norse Vikings, but their cousins from Jutland and northern Germany, the “Anglo Saxons”. The English, who largely departed the lands that would become Denmark to settle in the parts of Britain that would come to be called England.

To get to the point, hygge existed in the Old English language. I posted recently about how Valhalla may not be as alien a concept as we might think and to me, hygge is similar. Here is a quote from an Old English poem about the Battle of Malden:

“Hige sceal þe heardra, heorte þe cenre,mod sceal þe mare, þe ure mægen lytlað.”

There it is. Hige is hygge. It should go without saying the Danish and English are sister languages. They grew from the same root so we shouldn’t be surprised when the same words exist in both. Somewhere on the journey to modern English, Hige left us. Now it seems to be coming back. That it’s return should be an easy one is perhaps just because it’s easy to slot back in with an old friend.

To give some (possibly relevant) context, the excerpt of the poem above are the words of a warrior standing near the beach in what is modern day Essex, facing a bunch of bloodthirsty Vikings raiders. The relationships between ourselves and our continental cousins have not always been cordial. Ironically for this piece, the Vikings were probably Danes. The Norsemen had already killed the locals' leader, the Thane Byrhtnoth, and outnumbered the Essex men by quite a degree. As the Vikings advance on them, these are the words of men steeling themselves for a fight where their chances of survival - never mind victory - are, at best, uncertain. Modern translations of the poem tend to translate “Hige sceal þe heardra” as “Minds must be the harder”. Personally, I feel that to modern readers, the word in the second half of the line, “heart” maybe comes closer to the meaning of the original. My own translation is:

“Our spirits must be harder, hearts keenermood greater, as our strength fades”

But it's not that satisfactory. I find myself translating heart, mind, and spirit as ultimately the same thing.

Maybe, after all, it is untranslatable. Hygge is simple Hygge. There is no need for translation.

Mention of it even made its way onto Simon Mayo show on BBC Radio 2 today. Hipsters and trend setters will say its filling some sort of gap in our psyche that the English language somehow cannot express , though a recent article in the Guardian came close to hitting the mark with the comment that “Hygge may be quintessentially Danish, but there is something utterly British about the nostalgic longing for the simple accoutrements of an earlier time”.

Perhaps the reason for the sudden recognition of all things hygge is simply a realisation that we are peering at an old friend. Like when you spot someone across a crowded street in a strange city and think you know them, only to realise that against the odds they are actually your cousin, I believe the embracing of the concept of hygge is just such a remembrance of things lost in the rabbit holes of time, but perhaps not so far lost as to still be recognisable.

The thing is, this is not the first time that this word had made this exact journey. Today it’s carried by the internet and the media but fifteen hundred years ago it was carried from Jutland on rowed longships by invaders who also brought a new language to these islands. Not Norse Vikings, but their cousins from Jutland and northern Germany, the “Anglo Saxons”. The English, who largely departed the lands that would become Denmark to settle in the parts of Britain that would come to be called England.

To get to the point, hygge existed in the Old English language. I posted recently about how Valhalla may not be as alien a concept as we might think and to me, hygge is similar. Here is a quote from an Old English poem about the Battle of Malden:

“Hige sceal þe heardra, heorte þe cenre,mod sceal þe mare, þe ure mægen lytlað.”

There it is. Hige is hygge. It should go without saying the Danish and English are sister languages. They grew from the same root so we shouldn’t be surprised when the same words exist in both. Somewhere on the journey to modern English, Hige left us. Now it seems to be coming back. That it’s return should be an easy one is perhaps just because it’s easy to slot back in with an old friend.

To give some (possibly relevant) context, the excerpt of the poem above are the words of a warrior standing near the beach in what is modern day Essex, facing a bunch of bloodthirsty Vikings raiders. The relationships between ourselves and our continental cousins have not always been cordial. Ironically for this piece, the Vikings were probably Danes. The Norsemen had already killed the locals' leader, the Thane Byrhtnoth, and outnumbered the Essex men by quite a degree. As the Vikings advance on them, these are the words of men steeling themselves for a fight where their chances of survival - never mind victory - are, at best, uncertain. Modern translations of the poem tend to translate “Hige sceal þe heardra” as “Minds must be the harder”. Personally, I feel that to modern readers, the word in the second half of the line, “heart” maybe comes closer to the meaning of the original. My own translation is:

“Our spirits must be harder, hearts keenermood greater, as our strength fades”

But it's not that satisfactory. I find myself translating heart, mind, and spirit as ultimately the same thing.

Maybe, after all, it is untranslatable. Hygge is simple Hygge. There is no need for translation.

Published on December 08, 2016 13:34

November 26, 2016

Valhalla is a place on earth

I recently came to the realisation that Valhalla is an actual place, and you can go and visit it next time you are in London.Before you start wondering, I have not become a convert to Ásatrú or any of the other reconstructed neo-pagan religions. I’ve nothing against them -you may as well worship the entities after whom the days of the week are named if that’s what floats your (long) boat- but it's not for me. This was more of an epiphany arising from a sudden understanding of the linguistic roots of the concept, roots that -just about- reach down to touch even the modern English we speak today.

I'm nearing the end (finally) of writing the viking one I've been trying to get round to for about 20 years now and as part of the research for it I re-opened my Old Norse text books from college. As tends to happen, I soon got lost down the rabbit holes and burrows that riddle the mounds of linguistic and semantic history. It was during that journey that this revelation occurred to me.

Not for the first time, I was impressed by the fact that so often much meaning is lost in translation. At times the literal translation of one word in one language when brought to another tongue often fails to bring with it all of the semantic trappings and possible meaning associated with that word. We often marvel at the fact that for the Chinese, the same word can have many different meanings depending on tone. However words in English can have a variety of meaning depending on social, cultural and historical context. Sometimes, the real meaning of something can he hiding in plain sight.

The concept of Valhalla is familiar to us through a range of cultural references. From Wagnerian opera to Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant song”, The Mighty Thor (comics and Brannagh’s movie) to Conan the Barbarian (the Schwarzenegger version), the idea of the viking heaven where the dead can fight all day and drink all night has somehow been ingrained in our culture. I think its fair to say that the predominate impression of the place right from Götterdämmerung to the the excesses of 1980s heavy metal songs is pompous, male dominated and grim (pun intended).

Personally, I'm not sure this is true to what the heathen Norse actually believed. It's not something that I detected much of in the surviving Old Norse texts with their wry black humour and almost agnostic religious attitude. The reality of what Valhalla actually was (and still is) is likely to be far from the shield roofed golden Hall of Odinn described in the poetry.

On that note, perhaps it's worth having a quick diversion of just what the poets version of Valhalla was. In various medieval sources (which we must remember were written in the Christian era) Valhalla is depicted as having there are 540 doors, each one so wide that 800 warriors can walk through them side by side. The roof is covered with golden shields and the walls around Valhalla are made from wooden spear shafts. The spear/war-themed decor scheme continues inside, where spear-shafts are used for rafters, the roof is thatched with shields, coats of mail are strewn over its benches. For final touches a wolf hangs in front of its west doors, and, like an military helicopter, an eagle hovers above it. The dead who go there feast on a magic pig, Saehrimnir, while up on the roof a magic goat named Heidrun supplies endless mead instead of milk. It's at this point most modern readers would start to think "Really? A magic goat with milk flowing from it's teats? They believed this?"

My suspicion is they didn't. At least no more that a modern day believer might expect a set of pearly gates waiting for them at the entrance to the afterlife.

If anything, from the literature they have passed down to us, the Norse people were as vague on the afterlife as the famous Anglo-Saxon pagan priest recorded by Bede who advised his King to adopt the new Christian faith because he had no idea what happened either before birth or after death. There are some poetic references to Valhalla but it seems like to the average viking, when we die we all either go under a mountain or to Hell (literally: to the Norse Hell was the name of the Queen of the dead). An enormously practical people, what seems to have concerned the Norse most about what happens after they died was the one single thing that you can be sure will survive after you are gone: Your reputation. It was not just the everyday vikings who worried about it either, in the Havamal, purportedly Odinn himself states that you will die, your kinsmen will die and all your wealth and possessions will dissipate, but there is one thing that will not die and it is whatever fame you manage to earn during your life. Reputation and glory were the only sure form of immortality that you could count on.I believe it was the thought of what people would say about them when they were dead that spurred those ancient raiders up the beach with practically suicidal bravery, not a firm belief that their spirits would actually live on after their physical death in a golden battle hall. It was a sentiment that was not limited to the Vikings alone. Beowulf is obsessed with building his reputation and indeed this is his primary motivation for all his deeds throughout the poem.It should be no surprise that the title “Valhalla” is a mistranslation. The Old Norse name for the place is Valhöll which is usually translated as "hall of the slain". Höll of course means “hall” but translating “Val” as “slain”, while accurate, does not completely convey all of the meaning. The poets sang that the way to get to Valhalla was to be picked up from the battlefield and brought there by a Valkyrie -a “chooser of the slain” and the same word Val-or to give it it’s nominative form “Valr”- appears here also. These were not just any old dead bodies. The Norse had many names for the dead and “Valr” was a particularly special type of corpse. It was one that belonged to someone who died displaying impressive bravery, i.e. notable valour.And there you have it: The word survived into the modern era. Valour - the modern English form of the same word - may be a slightly archaic term for bravery today, but its is still understood. It still conveys a meaning that portrays a certain special type of courage, one that is unselfish, noble and also with a certain disregard for self preservation. Famously it appears in one place of shared cultural significance: The inscription on the Victoria Cross reads simply “For Valour”.

Now we’re finally getting to the point. The VC is the highest military decoration awarded for valour to members of the armed forces of various Commonwealth countries and former British Empire territories. The courage required to earn one is considerable and it carries the unique constraint that the associated deeds must be carried out quite literally “in the face of the enemy”. It is granted for exploits in war and other combat situations that are both up close and personal and often suicidal. Over a quarter of the VCs awarded during World War One were posthumous. To win one by your deeds ensures a record of your actions will live on beyond your lifetime, and most people will speak only great things of you, regardless of what you were actually like in life.

The largest collection of Victoria crosses can be found in the Imperial War Museum in London. Last time I was there it was upstairs and in a long gallery - a hall- to the left of the staircase. It is this place, I believe, that is the closest thing to Valhalla we have in modern society. It is, quite literally a Hall of Valour: The Valr Hall. It is not a shining, golden hall, with rafters made from spears and five hundred and forty doors. It’s a very quiet, dark room with ranks of brightly lit display cases in which the bronze crosses gleam alongside the labels that tell the tales of how they were achieved. In that respect it is probably closer, in my opinion, to what the everyday viking thought of when he turned his mind to death and Valhalla.Well, half of them, anyway. The other thing I was reminded of during this recent bout of research was that in the Norse tradition while the ordinary dead went to Hell, only half of the glorious dead went to Valhalla. The other half, due to some unexplained sorting rules, went to a field ruled over by the Goddess Freyja: Fólkvangr. For some reason this does not seem to have survived into our modern conscious. No heavy metal or operatic arias evoke Fólkvangr, nor is it mentioned in most historical fiction, though perhaps that is unsurprising. Everlasting feasting and fighting holds more dramatic potential than an eternity of, well, standing in a field.What the meaning behind this other viking heaven could be I will leave for someone else to work out.

I'm nearing the end (finally) of writing the viking one I've been trying to get round to for about 20 years now and as part of the research for it I re-opened my Old Norse text books from college. As tends to happen, I soon got lost down the rabbit holes and burrows that riddle the mounds of linguistic and semantic history. It was during that journey that this revelation occurred to me.

Not for the first time, I was impressed by the fact that so often much meaning is lost in translation. At times the literal translation of one word in one language when brought to another tongue often fails to bring with it all of the semantic trappings and possible meaning associated with that word. We often marvel at the fact that for the Chinese, the same word can have many different meanings depending on tone. However words in English can have a variety of meaning depending on social, cultural and historical context. Sometimes, the real meaning of something can he hiding in plain sight.

The concept of Valhalla is familiar to us through a range of cultural references. From Wagnerian opera to Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant song”, The Mighty Thor (comics and Brannagh’s movie) to Conan the Barbarian (the Schwarzenegger version), the idea of the viking heaven where the dead can fight all day and drink all night has somehow been ingrained in our culture. I think its fair to say that the predominate impression of the place right from Götterdämmerung to the the excesses of 1980s heavy metal songs is pompous, male dominated and grim (pun intended).

Personally, I'm not sure this is true to what the heathen Norse actually believed. It's not something that I detected much of in the surviving Old Norse texts with their wry black humour and almost agnostic religious attitude. The reality of what Valhalla actually was (and still is) is likely to be far from the shield roofed golden Hall of Odinn described in the poetry.

On that note, perhaps it's worth having a quick diversion of just what the poets version of Valhalla was. In various medieval sources (which we must remember were written in the Christian era) Valhalla is depicted as having there are 540 doors, each one so wide that 800 warriors can walk through them side by side. The roof is covered with golden shields and the walls around Valhalla are made from wooden spear shafts. The spear/war-themed decor scheme continues inside, where spear-shafts are used for rafters, the roof is thatched with shields, coats of mail are strewn over its benches. For final touches a wolf hangs in front of its west doors, and, like an military helicopter, an eagle hovers above it. The dead who go there feast on a magic pig, Saehrimnir, while up on the roof a magic goat named Heidrun supplies endless mead instead of milk. It's at this point most modern readers would start to think "Really? A magic goat with milk flowing from it's teats? They believed this?"

My suspicion is they didn't. At least no more that a modern day believer might expect a set of pearly gates waiting for them at the entrance to the afterlife.

If anything, from the literature they have passed down to us, the Norse people were as vague on the afterlife as the famous Anglo-Saxon pagan priest recorded by Bede who advised his King to adopt the new Christian faith because he had no idea what happened either before birth or after death. There are some poetic references to Valhalla but it seems like to the average viking, when we die we all either go under a mountain or to Hell (literally: to the Norse Hell was the name of the Queen of the dead). An enormously practical people, what seems to have concerned the Norse most about what happens after they died was the one single thing that you can be sure will survive after you are gone: Your reputation. It was not just the everyday vikings who worried about it either, in the Havamal, purportedly Odinn himself states that you will die, your kinsmen will die and all your wealth and possessions will dissipate, but there is one thing that will not die and it is whatever fame you manage to earn during your life. Reputation and glory were the only sure form of immortality that you could count on.I believe it was the thought of what people would say about them when they were dead that spurred those ancient raiders up the beach with practically suicidal bravery, not a firm belief that their spirits would actually live on after their physical death in a golden battle hall. It was a sentiment that was not limited to the Vikings alone. Beowulf is obsessed with building his reputation and indeed this is his primary motivation for all his deeds throughout the poem.It should be no surprise that the title “Valhalla” is a mistranslation. The Old Norse name for the place is Valhöll which is usually translated as "hall of the slain". Höll of course means “hall” but translating “Val” as “slain”, while accurate, does not completely convey all of the meaning. The poets sang that the way to get to Valhalla was to be picked up from the battlefield and brought there by a Valkyrie -a “chooser of the slain” and the same word Val-or to give it it’s nominative form “Valr”- appears here also. These were not just any old dead bodies. The Norse had many names for the dead and “Valr” was a particularly special type of corpse. It was one that belonged to someone who died displaying impressive bravery, i.e. notable valour.And there you have it: The word survived into the modern era. Valour - the modern English form of the same word - may be a slightly archaic term for bravery today, but its is still understood. It still conveys a meaning that portrays a certain special type of courage, one that is unselfish, noble and also with a certain disregard for self preservation. Famously it appears in one place of shared cultural significance: The inscription on the Victoria Cross reads simply “For Valour”.

Now we’re finally getting to the point. The VC is the highest military decoration awarded for valour to members of the armed forces of various Commonwealth countries and former British Empire territories. The courage required to earn one is considerable and it carries the unique constraint that the associated deeds must be carried out quite literally “in the face of the enemy”. It is granted for exploits in war and other combat situations that are both up close and personal and often suicidal. Over a quarter of the VCs awarded during World War One were posthumous. To win one by your deeds ensures a record of your actions will live on beyond your lifetime, and most people will speak only great things of you, regardless of what you were actually like in life.

The largest collection of Victoria crosses can be found in the Imperial War Museum in London. Last time I was there it was upstairs and in a long gallery - a hall- to the left of the staircase. It is this place, I believe, that is the closest thing to Valhalla we have in modern society. It is, quite literally a Hall of Valour: The Valr Hall. It is not a shining, golden hall, with rafters made from spears and five hundred and forty doors. It’s a very quiet, dark room with ranks of brightly lit display cases in which the bronze crosses gleam alongside the labels that tell the tales of how they were achieved. In that respect it is probably closer, in my opinion, to what the everyday viking thought of when he turned his mind to death and Valhalla.Well, half of them, anyway. The other thing I was reminded of during this recent bout of research was that in the Norse tradition while the ordinary dead went to Hell, only half of the glorious dead went to Valhalla. The other half, due to some unexplained sorting rules, went to a field ruled over by the Goddess Freyja: Fólkvangr. For some reason this does not seem to have survived into our modern conscious. No heavy metal or operatic arias evoke Fólkvangr, nor is it mentioned in most historical fiction, though perhaps that is unsurprising. Everlasting feasting and fighting holds more dramatic potential than an eternity of, well, standing in a field.What the meaning behind this other viking heaven could be I will leave for someone else to work out.

Published on November 26, 2016 03:06

November 16, 2016

The Battle of Kells

Seven hundred and one years ago, in November of 1315, the famous/infamous Sir Roger Mortimer suffered a rare early defeat. At the time a Scottish army led by Edward Bruce (Robert’s less successful and more impetuous brother) was involved in an invasion of Ireland. This side-conflict to the First War of Scottish Independence had begun in May of 1315 and by November was still going well. The Scots were riding wave of victories that stretched back a year and a half to the battle of Bannockburn and their Irish adventure had yet to become enmired in the series of defeats that led the BBC to recently describe the war as “Scotland’s Vietnam”. Edward’s army had just defeated the forces of the “Red” Earl of Ulster, Richard de Burgh, at Connor, a heavy defeat for the locals. According to the near contemporary poet John Barbour, “In that bataill wes tane or slane All hale the flur off Ulsyster” (in that battle was taken [prisoner] or slain all the flower of Ulster [the civalry/knights]). The road to Dublin lay open and the Scots were keen to push south towards the seat of power.Mortimer had yet to rise to the apex of his power, though he was still an important noble and a man to be reckoned with. Grandson of the famous Roger, First Baron Mortimer, he had inherited substantial estates in the Welsh Marches. He played an active role bearing robes at the coronation of Edward II of England, the King he would later first cockold, then depose, replace and possibly later murder. Through his marriage (at the age of 14) to Joan de Grenville, Mortimer became Lord of Meath, adding large tracts of Irish land to go with his territories in Wales.Probably because his own lands were so directly threatened, Mortimer was one of the few English nobles to realise the threat to England that a successful Scottish invasion of Ireland would prove. Shortly after Edward Bruce landed his army at Larne in May of 1315, Mortimer crossed the sea to Ireland, determined to take an active role in kicking to Scots back out.Re-enforced by the recent arrival of fresh troops under the Earl of Moray, Edward Bruce marched his army south to Dundalk. Mortimer, having provisioned his castle at Trim, marched his own troops to meet the Scots and the two sides met in battle outside Kells, in County Meath. Like a lot of encounters in this brutal war, there was probably an element of personal spite in the encounter. Much of the tone of the conflict saw families divided in their loyalties with different branches fighting on both sides. The Earl of Ulster, for example, was also Robert Bruce’s father-in-law. Mortimer had inherited his Irish lands in opposition to his wife’s cousins, the de Lacys, a powerful Anglo-Irish dynasty whose fortunes had recently been on the decline. With perhaps questionable judgement, perhaps through local necessity, Mortimer had made an alliance with the two De Lacy brothers he had effectively disinherited and their additional forces meant meaningful opposition to the Scottish army was possible.Three hours into the fighting, however, the de Lacys decided this was not their fight and withdrew, leaving Mortimer heavily outnumbered by the Scots. Mortimer’s army was destroyed and the Scots took and burned the town, the start of an onslaught of devastation they wrecked across the midlands of Ireland and which brought them much condemnation (and probably loss of support) by both English and (Gaelic) Irish alike.Mortimer himself was lucky to escape with his life, fleeing with only a few surviving knights to Dublin. He would later get his revenge but for that day victory on the battlefield belonged to Edward Bruce and Scotland.

Published on November 16, 2016 08:23

September 30, 2016

Dalriada and the Scots

410AD is largely regarded as the date for the end of Roman Rule in Britain. Throughout the final years of disintegrating Roman administration, letters were sent complaining of raids into the north of the Province of Britannia by a tribe called the Scoti, or Scots. These raiders were not from Scotland, however, which did not yet exist as a united realm under that name. They lived in the north east of Ireland.These Scots seem to have acted like ancient vikings – arriving in ships, attacking nearby settlements and towns and leaving with their ships laden with plunder and captives bound for a life in slavery in Ireland. One of the more famous of these stolen people was the son of a Roman Decurion now known as Saint Patrick. According to legend, the young Patrick during his enslavement worked as a shepherd on the slopes of Slemish in what is now County Antrim, an area that falls within the borders of an ancient kingdom called Dal Riada.Like the later vikings, the Scoti at some point seem to have stopped leaving the scenes of their crimes and began to settle down. The Annals of Tigernach, have an entry for the year 501 AD/CE that states “Feargus Mor mac Earca cum gente Dal Riada partem Britaniae tenuit, et ibi mortuus est” – Fergus Mor (“Big Fergus”) MacErc with the people of Dal Riada took part of Britain and he died there. Another legend says he died at Carrickfergus in County Antrim but regardless of that it signals the start of a kingdom that spanned the north east of Ireland and the west coast of Scotland. A dynasty of Kings ruled both sides of the Irish sea for the next hundred and fifty years. There appears to be some debate among modern scholers about which side of the Irish sea Dal Riada actually originated on, but by the end of the seventh Century the Gaelic language and to an extent culture existed both in north east Ireland and western scotland and the isles.

The kingdom was divided among several clans or kindreds: Cenél nGabráin (kindred of Gabrán) based in Kintyre, the Cenél Loairn (kindred of Loarn) in north and mid-Argyll and the Cenél nÓengusa (kindred of Óengus) based on Islay. In Ireland the centre of power was at Dunseverick on the north coast of County Antrim. The picture below was taken not far from there and illustrates how close the two countries are at that place. In a time when the fastest way to get about was by water, standing on the north Antrim coast, the mull of Kintyre was closer and easier to get to than Belfast.

In Alba, as they called the island of Britain at the time, as they expanded their influence, the Dalriadans came into conflict in the north west with the Kingdom of the Picts. To the south west they fought the Old Britons of Alt Clut and the English, who were expanding north themselves. In 603 they clashed with King Æthelfrith of Bernicia. The Dal Riadan army was led by their King, Áedán mac Gabráin, who Bede refers to as “King of the Irish in Britain”. Despite having fewer men, the English won the day and effectively ended Dal Riadan expansion to the south. On the face of it this could be seen as a clash between English and Irish, but as usual though (like for example the battles of Brunanburgh or Clontarf) the picture is murky when you start to poke into it. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle mentions, for example, that Herring, Æthelfrith’s cousin and a Bernician prince, led part of the Dal Riadan army against the English.Áedán is said to have had a son called Artúir, and some bloke called Dave Pilling :-) wrote about him as one of the potential candidates for the “historical” King Arthur (http://pillingswritingcorner.blogspot.co.uk/…/real-arthurs.… ). This isn’t the only tentative Arthurian connection to Dal Riada, there is another I’ll mention later. If you are still reading by then.

Another significant defeat for Dal Riada followed in the next generation, this time in Ireland. In 637 AD one of the bloodiest battles in Irish history occurred at Magh Rath (modern day Moira in County Armagh, and the village I live in). Congal Cláen, King of Ulaidh (Ulster), had been High King of Ireland, but an accident involving a bee sting resulted in him being blinded in one eye. No longer physically perfect, this meant he could no longer hold the High-Kingship which even in the Christian-era had sacred connotations. Before long he was at war with his successor (and foster father and owner of the bees that blinded him), Domnall mac Áedo of the Clan Connell who had taken his place as High King. Congal called on his allies to support him and among those who came was an army from Dal Riada. The politics of North Britain were such at the time that the Dal Riadan prince brought with him allies from neighbouring kingdoms too so along with him came some British princes from the Brythonic tribes of the Old North (in Welsh, Hen Ogledd, possibly the Gododinn or Ystrad Clud ). Amazingly, given that all these folks were fighting for the same pieces of land in what is now Scotland, a contingent of Anglo-Saxons came along too, possibly again exiled princes from Bernicia.

As always in Ireland, there seems to have been a religious element to the whole affair. Domnall's army included a Christian Saint in its ranks, Ronan Finn. Accounts of the battle of Moira mention kings among the Ulster army who are pagans, including one from Dal Riada. This is an interesting point. The battle was taking place 200 years after Saint Patrick had supposedly made Ireland Christian and 74 years after Saint Columba had founded Iona, yet supposedly parts of the north still followed the old ways. Readers of Irish legend, Seamus Heaney, Flann O’Brien, Joseph Heller and Neil Giaman’s “American Gods” will be familiar with the character of “Mad Sweeney”, a pagan Dalriadan King who is driven insane in the heart of battle and flees across the sea to Alba (modern Scotland), spending the rest of his days living in the woods thinking he is a bird until he eventually suffers a threefold death. Modern readers would call this PTSD, but Arthurian and Welsh scholars will see direct parallels with the story of Merlin/Myrddin Wyllt and the Battle of Arfderydd.The Ulster side lost and this date effectively marks the end of the Irish part of the Dal Riada story, though connections continued. The Kingdom in north Britain persisted though. By 843 it was ruled by Cináed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) who finally united (whether by violence or diplomacy this is needless to say debated) Dal Riada and the Kingdom of the Picts and became Kenneth I of Alba, a moment that could be argued as the birth of the modern concept of Scotland as a political entity.There is lots more to this tale so I'll probably post again sometime

The kingdom was divided among several clans or kindreds: Cenél nGabráin (kindred of Gabrán) based in Kintyre, the Cenél Loairn (kindred of Loarn) in north and mid-Argyll and the Cenél nÓengusa (kindred of Óengus) based on Islay. In Ireland the centre of power was at Dunseverick on the north coast of County Antrim. The picture below was taken not far from there and illustrates how close the two countries are at that place. In a time when the fastest way to get about was by water, standing on the north Antrim coast, the mull of Kintyre was closer and easier to get to than Belfast.

In Alba, as they called the island of Britain at the time, as they expanded their influence, the Dalriadans came into conflict in the north west with the Kingdom of the Picts. To the south west they fought the Old Britons of Alt Clut and the English, who were expanding north themselves. In 603 they clashed with King Æthelfrith of Bernicia. The Dal Riadan army was led by their King, Áedán mac Gabráin, who Bede refers to as “King of the Irish in Britain”. Despite having fewer men, the English won the day and effectively ended Dal Riadan expansion to the south. On the face of it this could be seen as a clash between English and Irish, but as usual though (like for example the battles of Brunanburgh or Clontarf) the picture is murky when you start to poke into it. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle mentions, for example, that Herring, Æthelfrith’s cousin and a Bernician prince, led part of the Dal Riadan army against the English.Áedán is said to have had a son called Artúir, and some bloke called Dave Pilling :-) wrote about him as one of the potential candidates for the “historical” King Arthur (http://pillingswritingcorner.blogspot.co.uk/…/real-arthurs.… ). This isn’t the only tentative Arthurian connection to Dal Riada, there is another I’ll mention later. If you are still reading by then.

Another significant defeat for Dal Riada followed in the next generation, this time in Ireland. In 637 AD one of the bloodiest battles in Irish history occurred at Magh Rath (modern day Moira in County Armagh, and the village I live in). Congal Cláen, King of Ulaidh (Ulster), had been High King of Ireland, but an accident involving a bee sting resulted in him being blinded in one eye. No longer physically perfect, this meant he could no longer hold the High-Kingship which even in the Christian-era had sacred connotations. Before long he was at war with his successor (and foster father and owner of the bees that blinded him), Domnall mac Áedo of the Clan Connell who had taken his place as High King. Congal called on his allies to support him and among those who came was an army from Dal Riada. The politics of North Britain were such at the time that the Dal Riadan prince brought with him allies from neighbouring kingdoms too so along with him came some British princes from the Brythonic tribes of the Old North (in Welsh, Hen Ogledd, possibly the Gododinn or Ystrad Clud ). Amazingly, given that all these folks were fighting for the same pieces of land in what is now Scotland, a contingent of Anglo-Saxons came along too, possibly again exiled princes from Bernicia.

As always in Ireland, there seems to have been a religious element to the whole affair. Domnall's army included a Christian Saint in its ranks, Ronan Finn. Accounts of the battle of Moira mention kings among the Ulster army who are pagans, including one from Dal Riada. This is an interesting point. The battle was taking place 200 years after Saint Patrick had supposedly made Ireland Christian and 74 years after Saint Columba had founded Iona, yet supposedly parts of the north still followed the old ways. Readers of Irish legend, Seamus Heaney, Flann O’Brien, Joseph Heller and Neil Giaman’s “American Gods” will be familiar with the character of “Mad Sweeney”, a pagan Dalriadan King who is driven insane in the heart of battle and flees across the sea to Alba (modern Scotland), spending the rest of his days living in the woods thinking he is a bird until he eventually suffers a threefold death. Modern readers would call this PTSD, but Arthurian and Welsh scholars will see direct parallels with the story of Merlin/Myrddin Wyllt and the Battle of Arfderydd.The Ulster side lost and this date effectively marks the end of the Irish part of the Dal Riada story, though connections continued. The Kingdom in north Britain persisted though. By 843 it was ruled by Cináed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) who finally united (whether by violence or diplomacy this is needless to say debated) Dal Riada and the Kingdom of the Picts and became Kenneth I of Alba, a moment that could be argued as the birth of the modern concept of Scotland as a political entity.There is lots more to this tale so I'll probably post again sometime

Published on September 30, 2016 03:12

February 3, 2016

Echoes of the past

“What we do now, echoes in eternity”These are the words of Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher Emperor of Rome, which Ridley Scott emphasised by having Russel Crowe’s character quote it in his film “Gladiator”.

I’ve been struck by how true this is many times before, mostly when some archaeologists discover the impression of a single moment in time, a throwaway, everyday act by an individual in the distant past who probably never thought about it again, that somehow left an imprint that we can still see centuries later. A great example was the woman who used her face cream in a temple in Roman London close to 2000 year ago and the gesture was preserved (along with her fingerprints) in the tin which was discovered back in 2003.

Last night I learnt another one. I was invited to speak at Ballyclare Library. The topic was Medieval Antrim and the Scottish Invasion of 1315 AD, the historical events behind my novels Lions of the Grail and The Waste Land, and a topic I've blogged about here before. I was delighted with the crowd that turned up and thank everyone for listening. After relating how Edward Bruce (brother of Robert) and his army had passed by Ballyclare both on their way to burn the manor and motte at Doagh and on the way to the battle of Connor, one local man fixed me with a inquisitive glare and said “Have you not heard of Bruce Lee?” - well that’s what I heard anyway.

As a fan of “Enter the Dragon” I replied that of course I had. I was highly confused then when he followed up with “Sure that’s where he camped.”“Who?” I asked, prompting a look that suggested he thought I was simple minded. “Edward Bruce. He camped out in the field there on the way to Doagh.” He explained.Further discussion revealed that it was not Bruce Lee he was talking about but Bruslee, a hamlet a few miles up the road from where we were standing, and the location of one of the council recycling centres. The “Brus” referring to Edward Bruce, and “lee” being the medieval term for meadow or field (aka a “lea”). It’s impressive to think that seven hundred years ago Edward Bruce and his army perhaps spent one night encamped there seven hundred years ago and the event has been preserved in the name of the place ever since. Its also very interesting that the spelling of “Brus” matches the medieval spelling of the Bruce name - for example the epic biographical poem about King Robert Bruce written in 1373 by John Barbour is titled “The Brus”. The other interesting thing is that the English (or perhaps Scots) name has survived since medieval times, including the couple of centuries after the dissolution of the Anglo-Norman Earldom of Ulster when the land was largely reclaimed by the Gaelic speaking Irish.Whatever the reasons, I wonder what a man as proud as Edward Bruce would have made of one of the very few memorials to him in Ulster now being the name of a recycling centre?

I’ve been struck by how true this is many times before, mostly when some archaeologists discover the impression of a single moment in time, a throwaway, everyday act by an individual in the distant past who probably never thought about it again, that somehow left an imprint that we can still see centuries later. A great example was the woman who used her face cream in a temple in Roman London close to 2000 year ago and the gesture was preserved (along with her fingerprints) in the tin which was discovered back in 2003.

Last night I learnt another one. I was invited to speak at Ballyclare Library. The topic was Medieval Antrim and the Scottish Invasion of 1315 AD, the historical events behind my novels Lions of the Grail and The Waste Land, and a topic I've blogged about here before. I was delighted with the crowd that turned up and thank everyone for listening. After relating how Edward Bruce (brother of Robert) and his army had passed by Ballyclare both on their way to burn the manor and motte at Doagh and on the way to the battle of Connor, one local man fixed me with a inquisitive glare and said “Have you not heard of Bruce Lee?” - well that’s what I heard anyway.

As a fan of “Enter the Dragon” I replied that of course I had. I was highly confused then when he followed up with “Sure that’s where he camped.”“Who?” I asked, prompting a look that suggested he thought I was simple minded. “Edward Bruce. He camped out in the field there on the way to Doagh.” He explained.Further discussion revealed that it was not Bruce Lee he was talking about but Bruslee, a hamlet a few miles up the road from where we were standing, and the location of one of the council recycling centres. The “Brus” referring to Edward Bruce, and “lee” being the medieval term for meadow or field (aka a “lea”). It’s impressive to think that seven hundred years ago Edward Bruce and his army perhaps spent one night encamped there seven hundred years ago and the event has been preserved in the name of the place ever since. Its also very interesting that the spelling of “Brus” matches the medieval spelling of the Bruce name - for example the epic biographical poem about King Robert Bruce written in 1373 by John Barbour is titled “The Brus”. The other interesting thing is that the English (or perhaps Scots) name has survived since medieval times, including the couple of centuries after the dissolution of the Anglo-Norman Earldom of Ulster when the land was largely reclaimed by the Gaelic speaking Irish.Whatever the reasons, I wonder what a man as proud as Edward Bruce would have made of one of the very few memorials to him in Ulster now being the name of a recycling centre?

Published on February 03, 2016 08:56

December 21, 2015

The Giant's Ring

At this time a couple of years ago I wrote a post about Newgrange, the impressive neolithic passage tomb on the Boyne river where the rays of the rising mid-winter sun casts a beam down the entrance tunnel. Today I visited a similar Stone Age monument somewhat closer to home but in many ways more impressive. The Giant’s Ring is a henge monument, a vast circular earthwork just outside Belfast. It has a dolmen (an ancient grave) just off centre. Dated to 4715 years ago, it was built before the Egyptian pyramids. Like the pyramids, it’s huge in scale. The ring is made of dikes 12 feet high and 50 feet wide. The ring encloses a space of 6.9 acres and is 600 feet in diameter.

Other barrows with ancient bones in them surround it. But like other neolithic sites, the place is shrouded in mystery. For example, why is the dolmen off-centre?

The vast ring is almost perfect, so it can’t just be sloppy measurements. Also what was this place for? Conjecture is that it was part of a major European cult of the dead that venerated holy ancestors. The tombs, cremations and inhumations that have been excavated in the area suggest there was something like that going on. Perhaps like, the pyramids, this was a vast monument to departed members of an important dynasty. We will never know. Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias”, springs to mind.

It’s sobering to think that the trees which grow around the site are generations older than me, but even their lifetimes are mere specks compared to how long the Giants Ring has stood here. This site is akin to a medieval cathedral in terms of the effort and organisation it must have taken to build it. Perhaps even more so when you think that the place was constructed by people with no metal tools. Like at Stonehenge, the Ring of Brodgar, Callanish or any of the other huge megalithic sites, the sheer scale of the transformation imposed on the landscape by these people some folk still see as “primitive” is humbling.

Most who know me will not see me as a superstitious person, but when I walked round the ring today I did not go widdershins. Instead I went clockwise, with the sun, like the earth making its annual circuit. The druids were supposed to be able to see portents in the flights of birds and I was slightly disconcerted by the single magpie that hopped around the dolmen for most of my circuit. When I got three quarters of the way round, it was joined by another one and I have to admit I felt a bit happier. The Giant’s Ring - a fascinating place well worth a visit.

The Giant’s Ring - a fascinating place well worth a visit.

Other barrows with ancient bones in them surround it. But like other neolithic sites, the place is shrouded in mystery. For example, why is the dolmen off-centre?

The vast ring is almost perfect, so it can’t just be sloppy measurements. Also what was this place for? Conjecture is that it was part of a major European cult of the dead that venerated holy ancestors. The tombs, cremations and inhumations that have been excavated in the area suggest there was something like that going on. Perhaps like, the pyramids, this was a vast monument to departed members of an important dynasty. We will never know. Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias”, springs to mind.

It’s sobering to think that the trees which grow around the site are generations older than me, but even their lifetimes are mere specks compared to how long the Giants Ring has stood here. This site is akin to a medieval cathedral in terms of the effort and organisation it must have taken to build it. Perhaps even more so when you think that the place was constructed by people with no metal tools. Like at Stonehenge, the Ring of Brodgar, Callanish or any of the other huge megalithic sites, the sheer scale of the transformation imposed on the landscape by these people some folk still see as “primitive” is humbling.

Most who know me will not see me as a superstitious person, but when I walked round the ring today I did not go widdershins. Instead I went clockwise, with the sun, like the earth making its annual circuit. The druids were supposed to be able to see portents in the flights of birds and I was slightly disconcerted by the single magpie that hopped around the dolmen for most of my circuit. When I got three quarters of the way round, it was joined by another one and I have to admit I felt a bit happier.

The Giant’s Ring - a fascinating place well worth a visit.

The Giant’s Ring - a fascinating place well worth a visit.

Published on December 21, 2015 13:29

December 15, 2015

Win a paperback copy of my new book, The Undead

I'm running a Goodreads Giveaway competition for the chance to win two paperback copies of my new book, The Undead. There are only three days left to enter (competition ends 18th) so if you want to have a go, you can enter by clicking here.

It's a gothic supernatural tale set in Victorian Belfast:

It's a gothic supernatural tale set in Victorian Belfast:

Ireland, 1839. Belfast is a city that is blossoming but already beginning to rot. Amid its crowded streets, linen mills and factories the body snatchers are on the loose and a homicidal maniac is on a killing spree. Witnesses claim that the murderer is an executed criminal who should be dead and buried. Captain Joseph Sheridan, a consulting detective from Dublin who specialises in investigating the supernatural, travels north to probe the mystery. Joining forces with Abraham Harpur, a Belfast policeman and Emily Brunty, a school mistress who wants to be a journalist, together they seek the truth behind who is resurrecting the murderous dead.

It's a gothic supernatural tale set in Victorian Belfast:

It's a gothic supernatural tale set in Victorian Belfast:Ireland, 1839. Belfast is a city that is blossoming but already beginning to rot. Amid its crowded streets, linen mills and factories the body snatchers are on the loose and a homicidal maniac is on a killing spree. Witnesses claim that the murderer is an executed criminal who should be dead and buried. Captain Joseph Sheridan, a consulting detective from Dublin who specialises in investigating the supernatural, travels north to probe the mystery. Joining forces with Abraham Harpur, a Belfast policeman and Emily Brunty, a school mistress who wants to be a journalist, together they seek the truth behind who is resurrecting the murderous dead.

Published on December 15, 2015 01:06

December 1, 2015

You better watch out, you better not cry…or you’ll be dragged off to Hell

Yule VisitorsChristmas is coming. You’ve probably noticed. Decorations are going up, trees are being lit and children are starting to await with accelerating excitement the arrival of a certain, “jolly elf” in a red suit on the night of December 24. As everyone knows, good children will be rewarded by Santa Claus with toys, because after all he knows who is naughty and who is nice.

But what about those naughty kids? When I was a child their reward was a lump of coal. I never met anyone who was actually bad enough to end up with that and I wonder what Santa’s policy is today in our more inclusive, politically correct society, where the concept that “differently behaved” kids should reap punishment for their actions would perhaps be frowned upon. Compared to some of our continental cousins, however, the idea of Santa delivering a lump of coal as reward for naughtiness seems like wishy-washy liberalism.In the northern, more Germanic parts of Europe, Santa Claus is not the only Yule visitor to make house calls. In most of Europe, presents are delivered by Saint Nicholas, usually around the start of December on his Saint’s Day (December 6). In a lot of places, he is accompanied by a “dark” character who does the the enforcement of the nice/naughty list. When I say, “dark” this can range from someone dressed in black to guys in (now rather tasteless) black-face make-up to “dark” in the sense of “utterly terrifying”. In the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) Santa Claus is accompanied by Zwarte Piet (in English “Black Peter”). He still appears in Christmas parades in Amsterdam and Belgium, portrayed by a white actor in the sort of black-face make-up that was even regarded as offencive in the 1970s. Apart from that facet, Zwarte Piet is reasonably benign and his job is to entertain the kids. Dodgy....

Dodgy....

Saint Nick is accompanied in Germany by another dark companion and with him things start to get a bit more serious. This character is called Knecht Ruprecht (Farmhand Rupert). He has a long beard that covers his face, wears a black robe and tends to be a bit dishevelled. He carries a bag of ashes and tests children on their ability to pray. If they can, he rewards them with apples, nuts or gingerbread. If they can’t, he beats them with his bag of ashes. Ruprecht is a nickname for the devil in Germany which might be a clue to his origins. The beating thing is a bit of a trend with these creatures. In Southern Germany the figure of Belsnickel comes at this time of the year. He wears dark fur and rags, a mask and carries a switch with which to beat the naughty kids. This character has managed to cross the Atlantic and appears among the Pennsylvania Dutch communities. He even turned up in the American version of “The Office”.

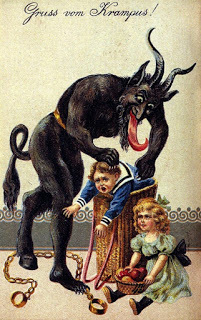

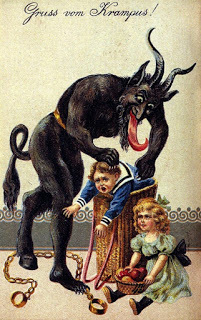

All these creatures are positively cuddly though when compared to Krampus. Krampus, not Lordi

Krampus, not Lordi

Krampus comes howling from the darkness of an Austrian Alpine nightmare. In the shape of a man but covered in black fur, curling horns sprouting from his head and with a lolling red tongue that would make Gene Simmons feel inadequate, Krampus arrives on the night of December 5th- Krampusnacht. Gene Simmons, not Krampus

Gene Simmons, not Krampus

He comes for the naughty children in the Alpine regions of Austria, Southern Bavaria, parts of the former Yugoslavia and Hungary and he doesn’t mess about with bits of coal either. Even beatings pale in comparison. Krampus bears a basket on his back and shoves the naughty children in it for transportation straight to Hell. As if the very idea of this horned demon was not terrifying enough, Austrians like to remind their children he is coming by exchanging krampuskarten (Krampus cards) at this time of year the way others send Christmas cards. Grretings from Krampus! If you feel your children could work on their behaviour and want to participate in this grand European tradition you can even get your own on Amazon. Even the Austrian Nazis banned Krampus “celebrations” in the 1930s, but like a lot of things they didn’t like, it only made him more popular. It seems that today Krampus is actually more popular than ever and not just in Europe. Krampusnachts and Krampuslaucht (which seems to be an alcohol-fuelled 5K in fancy dress) are cropping up in the USA as well. There will even be a horror/comedy film about him released this year (appropriately on December 4).It would be easy-and tempting-to say that this says a lot about the German psyche. The terror of misbehaving that is drummed into small children somehow translates into the fact that subsequent adults make sure all their trains run on time, but the only thing we really could say is that these traditions must be very old. The common theme that can be discerned is that a supernatural visitor arrives at this time of year who is dark furred or dark skinned, dishevelled, his face hidden by a mask and he punishes bad behaviour, usually by beating or sometimes worse. A variation of this figure is found right across the German-influenced parts of Europe from Holland to Slovenia, which shows the tradition must go way back in time to long before all these countries grew into separate nations. It’s tempting to speculate that this particular demon has haunted the world since the Romans peered nervously into the undergrowth of the Teutoburg Forest but we will just never know. However, next time you see children crying when they meet Santa Claus , just think what they would be like if they met Krampus.

Grretings from Krampus! If you feel your children could work on their behaviour and want to participate in this grand European tradition you can even get your own on Amazon. Even the Austrian Nazis banned Krampus “celebrations” in the 1930s, but like a lot of things they didn’t like, it only made him more popular. It seems that today Krampus is actually more popular than ever and not just in Europe. Krampusnachts and Krampuslaucht (which seems to be an alcohol-fuelled 5K in fancy dress) are cropping up in the USA as well. There will even be a horror/comedy film about him released this year (appropriately on December 4).It would be easy-and tempting-to say that this says a lot about the German psyche. The terror of misbehaving that is drummed into small children somehow translates into the fact that subsequent adults make sure all their trains run on time, but the only thing we really could say is that these traditions must be very old. The common theme that can be discerned is that a supernatural visitor arrives at this time of year who is dark furred or dark skinned, dishevelled, his face hidden by a mask and he punishes bad behaviour, usually by beating or sometimes worse. A variation of this figure is found right across the German-influenced parts of Europe from Holland to Slovenia, which shows the tradition must go way back in time to long before all these countries grew into separate nations. It’s tempting to speculate that this particular demon has haunted the world since the Romans peered nervously into the undergrowth of the Teutoburg Forest but we will just never know. However, next time you see children crying when they meet Santa Claus , just think what they would be like if they met Krampus.

Krampus

Krampus

If you are in the mood for some Christmas chills, my new gothic horror novel, The Undead is now available in Kindle and Paperback

But what about those naughty kids? When I was a child their reward was a lump of coal. I never met anyone who was actually bad enough to end up with that and I wonder what Santa’s policy is today in our more inclusive, politically correct society, where the concept that “differently behaved” kids should reap punishment for their actions would perhaps be frowned upon. Compared to some of our continental cousins, however, the idea of Santa delivering a lump of coal as reward for naughtiness seems like wishy-washy liberalism.In the northern, more Germanic parts of Europe, Santa Claus is not the only Yule visitor to make house calls. In most of Europe, presents are delivered by Saint Nicholas, usually around the start of December on his Saint’s Day (December 6). In a lot of places, he is accompanied by a “dark” character who does the the enforcement of the nice/naughty list. When I say, “dark” this can range from someone dressed in black to guys in (now rather tasteless) black-face make-up to “dark” in the sense of “utterly terrifying”. In the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) Santa Claus is accompanied by Zwarte Piet (in English “Black Peter”). He still appears in Christmas parades in Amsterdam and Belgium, portrayed by a white actor in the sort of black-face make-up that was even regarded as offencive in the 1970s. Apart from that facet, Zwarte Piet is reasonably benign and his job is to entertain the kids.

Dodgy....

Dodgy....Saint Nick is accompanied in Germany by another dark companion and with him things start to get a bit more serious. This character is called Knecht Ruprecht (Farmhand Rupert). He has a long beard that covers his face, wears a black robe and tends to be a bit dishevelled. He carries a bag of ashes and tests children on their ability to pray. If they can, he rewards them with apples, nuts or gingerbread. If they can’t, he beats them with his bag of ashes. Ruprecht is a nickname for the devil in Germany which might be a clue to his origins. The beating thing is a bit of a trend with these creatures. In Southern Germany the figure of Belsnickel comes at this time of the year. He wears dark fur and rags, a mask and carries a switch with which to beat the naughty kids. This character has managed to cross the Atlantic and appears among the Pennsylvania Dutch communities. He even turned up in the American version of “The Office”.

All these creatures are positively cuddly though when compared to Krampus.

Krampus, not Lordi

Krampus, not LordiKrampus comes howling from the darkness of an Austrian Alpine nightmare. In the shape of a man but covered in black fur, curling horns sprouting from his head and with a lolling red tongue that would make Gene Simmons feel inadequate, Krampus arrives on the night of December 5th- Krampusnacht.

Gene Simmons, not Krampus

Gene Simmons, not KrampusHe comes for the naughty children in the Alpine regions of Austria, Southern Bavaria, parts of the former Yugoslavia and Hungary and he doesn’t mess about with bits of coal either. Even beatings pale in comparison. Krampus bears a basket on his back and shoves the naughty children in it for transportation straight to Hell. As if the very idea of this horned demon was not terrifying enough, Austrians like to remind their children he is coming by exchanging krampuskarten (Krampus cards) at this time of year the way others send Christmas cards.

Grretings from Krampus! If you feel your children could work on their behaviour and want to participate in this grand European tradition you can even get your own on Amazon. Even the Austrian Nazis banned Krampus “celebrations” in the 1930s, but like a lot of things they didn’t like, it only made him more popular. It seems that today Krampus is actually more popular than ever and not just in Europe. Krampusnachts and Krampuslaucht (which seems to be an alcohol-fuelled 5K in fancy dress) are cropping up in the USA as well. There will even be a horror/comedy film about him released this year (appropriately on December 4).It would be easy-and tempting-to say that this says a lot about the German psyche. The terror of misbehaving that is drummed into small children somehow translates into the fact that subsequent adults make sure all their trains run on time, but the only thing we really could say is that these traditions must be very old. The common theme that can be discerned is that a supernatural visitor arrives at this time of year who is dark furred or dark skinned, dishevelled, his face hidden by a mask and he punishes bad behaviour, usually by beating or sometimes worse. A variation of this figure is found right across the German-influenced parts of Europe from Holland to Slovenia, which shows the tradition must go way back in time to long before all these countries grew into separate nations. It’s tempting to speculate that this particular demon has haunted the world since the Romans peered nervously into the undergrowth of the Teutoburg Forest but we will just never know. However, next time you see children crying when they meet Santa Claus , just think what they would be like if they met Krampus.