Stavros Halvatzis's Blog, page 49

November 30, 2014

Personal Reflections on Story Structure

Butterflies in the Dark

Writers like to talk about writing. We chance upon each other at unlikely places, as if by homing signal.I recently met a fellow writer queuing to cash a check from Amazon, like I was. We got to talking and, there and then, became friends. We now share ideas and suggestions via email, when meeting at the local bookstore isn’t possible.

Last week I ran into a novelist at the dairy section of a supermarket. The conversation quickly turned from the merits of cholesterol-reducing margarine to the study of story structure: I believed in it. He didn’t. We parted amicably enough, but the discussion got me thinking how my views on the subject have cured over time.

It was Elmo de Witt, the beloved South African filmmaker, who first suggested to me story structure could be studied, and one’s work could be improved because of it. I remember him handing me Syd Field’s The Screenwriters Workbook and asking me to read it.

“Without an understanding of structure you’re trying to scoop up butterflies in the dark, knowing they are out there, but mostly missing,” he told me. That was way back in the early 90s. Sadly, Elmo passed away in 2011, but I still remember his words clearly.

My initial reaction was unfavourable. I had graduated from university and film school with degrees in English Language and Literature and a Higher Diploma in the art and technique of filmmaking. I was young, confident – a bit of a know-it-all. What could any reductive approach to story-telling have to offer me? How could talent, spontaneity, flair, be nurtured through formulas? After all, before there were writing courses there were writers.

But as time went on, and I found myself staring at the blank pages on my desk, waiting for inspiration, the volume of Elmo’s words ratcheted up in my head.

I thought deeply about my reticence and I realised that it had less to do with any idealistic rejection of methodology than a fear of how colossal my ignorance on the subject of structure truly was: I was, after all, the resident screenwriter of Elmo de Witt Films. How could I admit I didn’t know a thing about Syd Field, and later, Christian Vogler, Michael Hague, John Truby, Linda Seger, and others? Rejection of the framework seemed my best defense.

Luckily, my head-in-the-sand attitude didn’t last. I realised in order to reject a piece of advice I first had to understand it. Not glibly, but deeply and innocently. Its nuances. Its nooks and crannies. That’s what constitutes integrity.

I began to read the books, and do the exercises, and grow my knowledge. By the time I was ready to reject the framework with impunity I found I didn’t want to. I found my understanding of structure had freed me from the vagaries of plot creation and allowed me to concentrate on the magic of character, theme, symbol, and story content.

Although my efforts at the time were directed mainly at the screenplay, I have come to recognise the novel, too, with its admittedly freer, more introspective, and lengthier flows, benefits from a deeper understanding of story structure.

This realisation has been invaluable to me. It has allowed me to move from one form to another with more ease than I could otherwise have managed.

That, at any rate, has been my experience. Perhaps you’ve had a similar experience, too?

Summary

One of the most valuable lessons South African filmmaker Elmo de Witt taught me is an appreciation of story structure.

Image: Marsel Minga

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

November 23, 2014

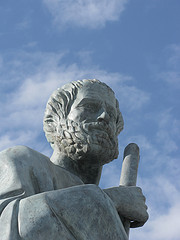

One Man’s Villain, is Another Man’s Hero

Hero or Villain?

As we have noted in previous posts, the antagonist performs a crucial function in any well-written story. He acts as a foil, spurring the hero on to achieve her true potential.But the antagonist is more than a mere technical device. He is also a flesh-and-blood character with a personality, a belief-system, and a goal of his own.

How many times have we seen the bad guy doing bad things, but can’t understand why? This is because he is merely a cog in the writer’s plot. Since the antagonist and protagonist form a basic narrative unit that drives the story forward, a badly written villain will stall the engine.

Generally, all aspects of crafting a believable character apply to the antagonist, but one in particular warrants special mention — the villain believes he is the hero of his own story! He believes he is justified in doing what he does.

In The Matrix, agent Smith despises human beings. He hates their smell, their sweaty bodies, which he sees as prisons of meat. His job is to rid his perfect world of anyone who threatens to destroy it. He is clever, determined, skilled — in his own mind, a hero with a cause. It is partly this self-belief that makes him such a memorable villain.

In The Shawshank Redemption, the bible-punching Warden is obsessed with maintaining absolute order in his prison — in itself, a good thing. The problem is he is also a cruel killer.

In The Last of the Mohicans, Magua is a terrifying villain. His goal is to kill Grey Hair and eat his heart, but not before he hacks his children to bits while he watches. But, if that’s all there was to him, he’d be a one dimensional character, with little interest to us other than as a plot device.

But, later in the story, we learn that his village was destroyed by the English, his children killed, and he enslaved by Indians who worked for Grey Hair. To make matters worse, his wife married another man thinking he was dead. The backstory casts Magua as a tormented and bereaved husband and father seeking revenge — hardly a cardboard cutout serving only the plot.

Summary

The antagonist does not consider himself as being evil. He feels justified in his actions because of a wrong perpetrated against him in the past. Grant your antagonist a powerful cause to give him credibility and depth.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: RyC – Behind the Lens

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

November 16, 2014

How Fascinating is the Idea Behind your Story?

As a teacher of creative writing, I am often privy to complaints by new writers that their books or screenplays don’t get off the ground, sinking into obscurity instead.

As a teacher of creative writing, I am often privy to complaints by new writers that their books or screenplays don’t get off the ground, sinking into obscurity instead.

Is it fate, karma, or just plain bad luck, they ask?

Now, while it’s true that luck plays a role in a writer’s success, (not sure about the other two), it’s also true that you can’t keep a good idea down.

Not just any good idea, mind you — a vibrant, original idea we haven’t encountered before, or, at least, an idea presented in a way that feels new; an idea that takes us places we’ve never been, fills us with wonder, introduces us to characters that captivate us.

Consider some of my favorites stories: Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Being John Malkovich, Jurassic Park, The Matrix, Stranger than Fiction, City Of God, 2001: A Space Odyssey, George Orwell’s 1984.

All of these, apart from being well-written, are fascinating and original. They grab our imagination and compel us to know more.

A mysterious black monolith that appears at crucial moments of man’s evolution to spur him on? Wow!

A procedure to erase painful memories from one’s mind. I want to know more!

Jurassic creatures brought to life through DNA preserved in a dollop of Amber? Yes, please!

A secret passage that takes us right into John Malkovich’s head! Who would have thought it!

These ideas are so good, so original, they sell themselves. They make for hugely successful stories – providing all other elements of fine writing are in place, of course.

I believe I should not start writing a story until I am absolutely convinced that the idea behind it is as good, as original and unique, as it can be, because once I start, I find it difficult to change it mid-stream.

My advice to myself is simply this: Start with an idea that fascinates. Isolate its captivating core and think about ways to make it more unique, more original. Come at it from different angles, from the point of view of different characters, different genres, even different epochs. Write at least ten versions of the basic idea, trying, each time, to up the ante, then walk away from it for a week or two, to give it time to breathe, before repeating the process.

Once I’m convinced I have a good idea, I test it on others. I watch their eyes as I speak. If they flick away, seem distracted, I’ve lost my audience somewhere. That happens a lot. The path back to the drawing board is well-worn.

Your process may differ from mine, but one thing seems likely: the more original and unique your idea, the more fascinating your story will be.

Summary

Fascinating, original, well-written stories are the panacea to obscurity.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Saad Faruque

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

November 9, 2014

How Moral is your Story?

At the core of most memorable stories lies a theme with a strong ethical or moral premise.

At the core of most memorable stories lies a theme with a strong ethical or moral premise.

In a very real sense, a story is about proving the theme by tracking the conflict that ensues between the hero and his nemesis, both of whom represent opposing values. In simple terms, good guys finish first, or last, depending on the outcome of that conflict.

But does this then mean that some stories are not ethical or moral? Is the nemesis’ winning of the fight, proof that unethical and immoral behaviour can triumph?

Biblical tales, for example, are clearly moral – Noah, Cleopatra, The Ten Commandments. As are modern stories, such as Braveheart, The Firm, Gladiator, Oblivion, Edge of Tomorrow, and countless others. These tales have at their core a moral premise that states that if the hero does the right thing, he will eventually achieve the goal, carry the day, save the world, even if it sometimes means that he has to sacrifice himself to do it.

But what about less obvious examples? Seven? Fight Club? Inception? Oceans 11,12,13? in what sense do these stories espouse ethical or moral values?

This bothered me quite a bit because, deep down, I felt that all great stories promote the best in us rather than the worst. Yet, something rang true about these latter stories. I felt a resonance and verisimilitude in them that I normally associated with great tales.

Then, during one of my classes on story-telling, it struck me: Most stories are indeed moral and ethical, with one proviso: In some, the moral or ethical judgment falls outside the world of the story itself — it is made by an audience or reader based on received cultural, social, and religious values.

Stories in which the villain gets away with it, spreading death and mayhem in his wake, may appear to show that malice, slyness, and cold-blooded determination lead to victory, but few of us would applaud his actions.

A horror story, in which, let’s say, demons succeed in taking over the world, is not necessarily a celebration of evil overcoming good. Rather, it is a warning: If the hero fails to stop evil, this is the result – a horrific world overrun by demons.

The characters within such a story may even celebrate this fact, but audiences, as a whole, won’t, since they bring their own moral and ethical systems to bare upon the tale.

Paradoxically, then, good will always rise above evil even when it seems defeated.

Summary

Most stories rest on a solid ethical and moral foundation, even those that ostensibly seem not to.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Tilemahos Efthimiadis

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

November 2, 2014

A trait, a trait, my kingdom for a trait!

One of the marks of accomplished writing is how well the writer integrates the hero’s outer and inner journey in her story. Which is to say: How well does the inner journey explain and support the visible events of the plot? Not only must the writer present a clear developmental arc for her protagonist, but she must integrate that arc with the protagonist’s actions.

One of the marks of accomplished writing is how well the writer integrates the hero’s outer and inner journey in her story. Which is to say: How well does the inner journey explain and support the visible events of the plot? Not only must the writer present a clear developmental arc for her protagonist, but she must integrate that arc with the protagonist’s actions.

One way is to tie the hero’s arc both to the hero’s and to the antagonist’s character traits.

We are reminded in previous articles on this topic that, typically, a character has four traits — three positive and one negative for the hero, and three negative and one positive for the villain. This allows the writer to tie the hero’s inability to achieve the goal to his negative trait — a trait the villain skillfully exploits to keep the hero down.

But, by the end of the story, the tables turn. Schooled by experience, the hero is not only able to dig deeper and unleash the power of his positive traits, but he can identify and use the villain’s own weakness against him, too. This is a one-two punch combination that is enough to gain the hero his goal by knocking out his opponent

In Gladiator, Maximus is able to muster his remaining strength and slay the usurping emperor with his own sword. In so doing, he fulfills his promise to revenge his family and keep Rome safe from all enemies, including tyrants. He is able to manifest his inner strength, which stems from moral fortitude and loyalty, as physical strength, and use it against the villain’s own weakness: Had Commodus not been an egoistical coward determined to show Rome that he could defeat the world’s greatest gladiator in the arena, he might well have lived.

It is this combination, this interlocking of the positive traits of the hero with the negative traits of the villain, that allows the final showdown to resonate with irony, tension, and a sense of justice. The result is a powerful and memorable story skillfully rendered. We would do well to emulate this in our own writing.

Summary

Use your hero’s and villain’s warring traits to drive the story forward and to integrate inner and outer journey events.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: dbking

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

October 26, 2014

Great Villain? Great Hero? Great Story!

The success of a story largely depends on how well the writer uses the protagonist’s outer and inner journeys to prove the theme.

The success of a story largely depends on how well the writer uses the protagonist’s outer and inner journeys to prove the theme.

But it’s not all just about the protagonist. Behind every successful hero lurks a relentless and resourceful villain.

Novice writers tend to develop their heroes and villains separately, instead of crafting them as polar opposites of a single narrative entity.

If your hero is a clever, clean-cut, Kung fu expert you need a powerful villain to stand up to him. Pacific Rim, is filled with battle-hardened heroic types, manning highscraper-tall machines. The writer had to come up with monster-size villains to threaten them.

The more powerful your hero, the more powerful your villain needs to be in order to generate risk, suspense, and excitement — to dangle the possibility that he may indeed defeat the hero.

Strength, of course, is not merely physical. In Ordinary People, the mom is a formidable and relentless opponent whose implacable determination to take custody of her young son drives the plot forward.

Although villains are crafty and tireless plotters, they are not 100% bad. Remember, villains don’t see themselves as villainous. They feel justified in doing what they do — in their minds, they are merely seeking revenge, righting a wrong, balancing the books, for a perceived injustice perpetrated against them.

Additionally, a successful villain knows how to punch the hero’s buttons. He takes advantage of the hero”s weakness. If your hero is a rich stockbroker, the villain is an even richer businessman who manipulates the market to bring him down. If your hero is a champion boxer, his opponent is a seven foot, three hundred pound Russian giant.

Remember, then, that the hero and villain form a single unit. Identify the hero’s weakness and the villain’s strength, and have the villain take advantage of that weakness — until the last moment when the tables turn and the hero uses the same technique against the him.

Lastly, have the final confrontation play out in the villain’s lair — the place that is most advantageous to the villain. It will raise the tension and fill your readers or audience with dread. Providing you have chosen an up-ending, it will also make your hero’s final victory that much sweeter.

Summary

The hero and villain are polar opposites. They form a single narrative unit. Use the hero’s weakness and the villain’s strength to complicate the plot and heighten tension. Reverse this technique to achieve your hero’s final victory.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Les Haines

Lisence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

October 19, 2014

How to keep your story interesting through reversals

Keeping our story interesting as we navigate towards the major pivot points (the inciting incident, the first and second turning points, the midpoint, and climax), takes some doing.

Keeping our story interesting as we navigate towards the major pivot points (the inciting incident, the first and second turning points, the midpoint, and climax), takes some doing.

This is because we need time to lay out essential information and perform certain tasks in support of character development and plot that will only pay off later. But this may cause interest in our story to wane. Reversals are one way to keep our readers or audience engaged.

Reversals are well-placed surprises. No story can really function without them. They occur when you create a certain expectation in the reader or audience, only to surprise them a moment later with another:

1. A child enters an abandoned house on a dare and hears a sound coming from the steps leading down to the basement. Suddenly, a shadow appears on the wall, growing impossibly larger. The child shuts her eyes, unable to face the source of the shadow. After what seems an eternity, she hears another sound and opens her eyes, only to discover that the shadow is cast from a mangy cat caught in a slither of light from below.

2. A mother enters her daughter’s room to find the bed empty and the window wide open. We assume by her expression that her teenage daughter has snuck out of the bedroom, despite being grounded. The mother hears the toilet being flushed and smiles with relief, but the smile quickly evaporates when the bathroom door opens and a young man exits, followed by her daughter.

Here, within the space of a few seconds, we have two reversals that keep us engaged through the mechanism of surprise.

3. In The Wild Bunch a robbery results in a tremendous gunfight. Lucky to get away with their lives, the robbers reach safety and open the bags to count their loot only to discover they are filled with washers. This is both a reversal and a pivot point since it changes the plot. We should remember, however, that reversals are most useful when applied to smaller dramatic beats, since major turning points are potentially interesting enough on their own.

Summary

Reversals are dramatic beats placed between major turning points of a story designed to keep interest from flagging.

Image: Nicolas Raymond

Liecence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

October 12, 2014

Is this your story?

Your Story:

A student recently asked me whether there is a template for writing a story that adheres to the sort of structure that I, and others, teach in class.I provided her with one type of example, while simultaneously emphasising that there are no real shortcuts to accomplished writing, only lampposts highlighting the journey ahead.

Here’s what I said:

“A likable Hero finds herself in a position of undeserved misfortune and decides, after initially refusing, to take action to redress the situation. But the harder she tries, the more embroiled she becomes in mounting stakes and deepening dilemmas, each, more dangerous and difficult than the last. This forces her to search deep within herself for a different solution. In doing so, she discovers, at the last minute, a liberating truth about herself which allows her to achieve her goal by tackling past misconceptions, moral flaws, and misguided plans.”

What I like about this description of a story is that it addresses both the outer and inner journeys through the character’s developmental arc. It reminds us that the inner journey steers the outer journey through the decisions our Hero makes at pivotal moments. It hints at a universal truth — that the only way our Hero can achieve the outer goal is by implementing the wisdom that comes from having faced near defeat.

Summary

Although story templates, are, by definition, reductive and constrictive, they do serve as starting points for the journey ahead.

October 5, 2014

Emotion Rules!

Joy!

If there’s one thing my friend and mentor, the late South African filmmaker, Elmo De Witt, taught me it is to focus on emotion in the stories I write. “Without emotion, no one will care about your story, no matter how much cleverness you weave into it,” he was fond of saying. How true. His early films, such as Môre, Môre (Tomorrow, Tomorrow), are testaments to that fact.He’s not the only one. Here’s William M. Akers on the subject: “Give the reader an emotional experience or you’re wasting your time.”

But how do we do this? Here are some suggestions:

Never miss an opportunity to create an emotional moment, even in passing. Your Hero buys a newspaper one evening from a street vendour, a worse-for wear old man who looks like he’ll be stuck with the day’s remaining stock. Our Hero pays for the paper and moves on. The plot function of this bridging scene is for the Hero to discover, hidden somewhere on the back page, a vital clue to his case. Function achieved. Great scene. Right?

Wrong. It’s a missed opportunity.

How about having our Hero buy the whole pile of papers just to help the old man out? The plot remains intact, but adds a layer of compassion, which makes us feel something! This makes for a more successful scene.

Emotion can be anything: compassion, sadness, fear, lust, joy. In Rear Window Grace Kelly arrives at Jimmy Steward’s house with an overnight case. She opens it and we see she has packed a nighty. We gulp with anticipation, knowing she intends to sleep with him.

In the film, On the Waterfront, Marlon Brando confronts Rod Steiger about the thrown fight that ruined his life: “I could have been a contender. I could have been somebody.” The scene brims over with sadness and regret, which helps make it one of the most memorable.

And, how about one of the most moving scenes of all time? Fired for encouraging students to think and feel for themselves, John Keating is about to leave his beloved classroom forever, under the withering gaze of the man who fired him, when one after the other, the students ignore possible expulsion and defiantly stand on their desks in support , calling out: “Oh, Captain, my Captain.” This is not only a plot victory for Keating, and his beliefs, but a hugely successful emotional moment, too. I don’t know about you, but my handkerchief was soaked through by the time the titles rolled.

The point is that we tend to remember, for a long time after, finely crafted scenes that reveal important information, but scenes that are supercharged with emotion, we remember forever.

Summary

Supercharge your scenes with emotion, and do it often. Your story will be more memorable for it.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Theodore Scott

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

September 28, 2014

When is Your Hero Not a Hero?

I Need a Hero

It happens to all writers at some time or another. We fancy a certain character as the Hero of our story only to discover that he falls flat by the end of the tale. He just doesn’t…well…he just doesn’t feel heroic enough.So, how do we avoid having a damp squib for a Hero? Here, curtesy of William M. Akers, is a list of suggestions:

1. A Hero is active. He initiates action, reaches for his goal and never quits until the bad guy is defeated and the goal achieved. In Edge of Tomorrow, Tom Cruise keeps coming back to life again and again in an attempt to defeat the mimics.

2. A Hero has a well defined problem—one main problem that she needs to solve in order to win the prize, save the day, get the boy. This problem is as much something she has to learn about herself, as it is a physical obstacle she has to overcome. The physical problem is merely a reflection of an inner need or flaw that has to be addressed.

3. The Hero’s problem must be interesting to an audience. The bigger the stakes implicit in the problem, the more interested we will be in his plight. In Breaking Away, the hero struggles to discover whether he is a bike rider or a stone cutter. This may not be much of a problem for you or me, but it is a problem for this particular character. Since we identify with the hero, we, too, desire that he solve it, and that he do so in an intriguing way.

4. The Hero must solve his own problem. Although the Hero may have allies and sidekicks, it is he who must take the lead in solving the problem and achieving the goal. Aimless, unfocused protagonists who drift in and out of fuzzy situations are best left for art films with niche followings, because they will not prove popular with mainstream audiences, (with one or two notable exceptions.)

These, then, are some of the characteristics that define the Hero in your story. So, when is your Hero not a Hero? When he fails to tick most, if not all, of these boxes.

Summary

Heroes are active problem-solvers whose actions drive the story forward. They are leaders not followers.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Daveynin

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...