Stavros Halvatzis's Blog, page 54

December 22, 2013

How to Use Coincidence in Stories

Coincidence?

Can a story contain a convenient coincidence without being deemed lazy and weak? After all, Charles Dickens’s work abounds with such narrative devices. I believe the answer is yes, but only if it is limited to one per story and is carefully woven into the tale.Although life is riddled with what appears to be magnificent coincidences—the meeting of one’s future spouse by chance, the winning of a grand prize, the procurement of a lucrative job based on an impromptu internet search, stories are a different kettle of fish. Here, the reader or audience expects the material to be adroitly planned and crafted. A series of coincidences is viewed for what it is: laziness on the part of the writer.

In Screenwriting, Professor Richard Walter, too, is of the opinion that coincidence can work if the writer makes it important enough, and has it launch or end the story as part of a main structural event, such as the inciting incident or turning point.

In Preston Sturges’s Christmas in July, for example, well-intentioned pals fool a friend into believing that he has won a contest. In the end, it turns out that he actually has won the contest. Why does such a coincidence work? Partly because it is the only one in the film, and partly because it spins on a deliciously crafted irony.

In The China Syndrome, Jane Fonda and cameraman Michael Douglas, happen to be filming a story at a nuclear station. Something malfunctions at the plant and they record the incident. Here the coincidence is not offensive.

Imagine, however, if, in seeking to add twists and turns to the tale, the writer had introduced a scene in which the footage was lost or destroyed. The crew then returned to shoot more material, when, lo and behold, another nuclear mishap occurred! Audiences would be outraged. What worked the first time around would not work again because such a coincidence would be unimaginative and repetitive.

Summary

A single coincidence works best early or late in a story, spins on irony or surprise, and forms part of a major structural event such as the inciting incident or the first or second turning point.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, or have a suggestion for a future one, kindly leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

December 15, 2013

Avoiding Repetition in Stories

Avoiding Repetition:

Repetition through dialogue or action in films and novels—other than as an attempt to hook, or link lines so that they flow more rhythmically, is, at best, tedious, or, at worst, amateurish.In his book, Screenwriting, Richard Walters uses the film, Yentle, to illustrate this point. The film starts with a prologue informing us that in the Eastern Europe of the time, education was meant for men only. Moments later, a bookseller rides a cart through the streets advertising “scholarly books for men! Romantic novels for women!”

When Yentle gets to town she finds and peruses the bookseller’s books, studying a scholarly tome in particular. Upon seeing this, the bookseller snatches the book from her and reminds her, and us, that such books are meant for men only. She should seek out romantic books instead.

This sort of repetition is condescending, implying that we are incapable of getting the point the first time around.

Repetition is, of course, acceptable, but only if it is not repetitive. This is not as contradictory as it sounds.

In Rashomon, four observers relate the same event, but here each version differs in the detail from the others, adding a unique and intriguing quality to the recounting. Although this is an exceptional rendition of a technique that examines the nature of human perception and truth itself, there are other techniques that emphasise existing information whilst avoiding repetition.

In Unforgiven, we learn that the sherrif, Little Bill, is a tough antagonist to Clint Eastwood’s William Manny. In seeking to elevate the stature of the sherrif, the writer has one of the deputies underline his toughness by assuring the others that Little Bill is scared of no one, having survived a tough education in the mean streets of Kansas. This inflection adds to Little Bill’s ruthless reputation, rather than simply repeating pre-existing information.

Summary

Repeating information already provided to an audience or reader is condescending and unnecessary, except when it is specifically rendered as emphasis.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, or have a suggestion for a future one, kindly leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

December 8, 2013

How to Merge Story Strands

Merging Journeys

In seeking to find an effective way to highlight the unity that exists between the outer and inner journey in a story, both in my own writing, as well as in my teaching, it struck me that the structural pivots in a tale (the inciting incident, the turning points, the midpoint) precisely provide for such an opportunity. They are the knots that tie the outer and inner strands of the tale together.The outer journey, we are reminded, recounts the beat-by-beat occurrence of external events as the Hero struggles against mounting obstacles to achieve the visible goal of the story—preventing the bomb from going off, winning the girl, or the boxing championship, rescuing the kidnapped victim, and so on.

The inner journey, by contrast, is the internal path the Hero takes to enlightenment or obfuscation, depending on the genre of the story, as he initiates or reacts to the outer journey’s challenges, surprises, achievements and setbacks.

The structural pivots combine an outer and inner event into a single motivated action. Lagos Egri, one of the most lucid teachers on the craft of dramatic writing explains that the inner journey is the “why” to the outer journey’s “what”. In short, ensure that your turning points, including your midpoint, describe external events of sufficient magnitude that cause the Hero to react in a way that is in keeping with his current/evolving inner state.

Is it preferable, then, to let the inner state, or, journey, trigger the outer event, or should it be the other way around? I don’t think there is a definitive answer to that question—either will do, just as long as both through-lines end up being tightly interwoven.

In Rob Roy, Liam Neeson’s character accepts his wife’s unborn child—a result of her being raped by an Englishman, because of who he is: a man of immense conviction and inner strength, just as he fights and wins a sword fight against the fop, the expert English swordsman, despite being outplayed at the end, again, because of this inner strength and conviction.

In Braveheart, William Wallace accepts knighthood at the midpoint of the story. This motivates him to move from being an isolationist who merely wants to be left alone to farm with his family, to a national leader who takes the fight to the English. The knighthood ceremony is a perfect fusion of an outer and inner event—as a knight he now has a moral obligation to fight for those who fall under his protection.

Summary

The major pivot points are the perfect place for the writer to ensure that the “why” merges with the “what” in her story. Such pivot points offer the perfect place for the inner and outer journeys to merge and support each other.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, or have a suggestion for a future one, kindly leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

December 1, 2013

3 Rules of Character

Constructing Character

In his book, Screenwriting, Professor Richard Walter of UCLA reminds us that there are three fundamental rules for creating great characters:1. Avoid stereotypes.

2. Inject some sympathetic aspect into even the most evil and despicable of your characters.

3. Force your characters, especially your protagonist, to change and grow throughout the tale.

Stereotypes

Stereotypes are boring. Avoid them like the plague. The kind-hearted priest? Seen it. The hard drinking Irish cop? Seen that too. The pissed off police captain? Ditto.

A useful way to avoid stereotyping a character is to think of a type then present its opposite. Imagine a sheriff from the deep south who is not a bigot and a dimwit, but is bristling with intelligence and dignity, passionate about revealing the truth and delivering an even-handed justice. Or a nun who is a baseball fanatic and is a genius at game statistics.

Character Growth

Truly memorable characters start off in one place and end up in another. In Kramer vs. Kramer, Dustin Hoffman begins as an insensitive, selfish narcissist but ends up as a kind and wise father who puts the happiness of his child first. At the start of The Godfather, Michael Corleone is innocent, principled, moral. By the end he is heartless, bereaved and soulless—a power hungry murderer of many, including his own brother.

Not every character needs to change, of course. Patton stays the same throughout the movie of the same name, although his character is challenged and is explained in a way that reveals to us why he is the way he is—an inflexible but powerful warrior to the last.

Sympathy

Well rounded, complex and conflicted characters are more absorbing than facile, boring ones. But with the interest that comes from lying, scheming and conniving comes the danger of characters becoming unlikable. It is, therefore, important to ensure that some aspect remains sympathetic to the reader or audience. If we don’t like our characters, especially the protagonist, we won’t like her story.

Oedipus murders his father then performs incest with his mother: horrific actions for a protagonist to indulge in. The writer, Sophocles, ensures that Oedipus remains sympathetic to his audience firstly by showing that Oedipus is unaware of the true facts of his coupling, and, secondly, by having him show deep and genuine remorse upon learning the truth.

In a Bridge on the River Kwai the Japanese commander of the prison camp is a cruel tyrant whose humanity still manages to peep through, if even once. He violates international laws, holds his prisoners in hot boxes, tortures and humiliates them, yet the writer portrays him as an unfortunate wretch who is tapped in a harsh command structure by permitting us to see him weep.

Summary

Well drawn characters are an indispensable part of successful story telling. Avoiding stereotypes, injecting character growth and creating sympathy are some of the ways of creating engaging characters.

November 24, 2013

How to Choose Character Names

What's in a Name?

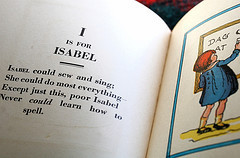

Character names are an important part of constructing character identity. Not only does a name help us to identify the players in your story, but it often carries the flavour and scent of that character.An expectant mother is overheard choosing a name for her child: Pat, Kelly, Terry, Bobby. Her sole reason for considering these particular names is that each can be applied to both a boy and girl. This flexibility could save her the disappointment of choosing a name early only to have her give it up upon discovering the actual gender of her baby.

But this flexibility is precisely the reason we should avoid assigning interchangeable names to the characters in our stories. Although an audience will immediately recognise someone by her or his appearance, this is not the case with words on a page. Here, the character description performs this function, which, in the short story or novel, may be purposely scanty, or scattered throughout the text. At a glance, the name of the character is the chief indicator of identity, as in the above instance. Few readers will doubt the gender of a Samuel, Rachael, Frederick, or Penelope.

It is also good practice to avoid giving characters similar sounding names. Clive and Kyle, Sharon and Shannine, Harry and Larry—except, of course, where the possible confusion flowing from this similarity helps the plot.

But a name may also add additional meaning and flavour to a character: Biblical names such as Paul, Peter, Ezekiel, Rachael, Mary and David, although commonplace, may still carry a trace of biblical resonance, especially if the context supports this. In my forthcoming novel, Mars: Planet of Redemption, the protagonist, an unconventional priest with the power to heal, is called Paul, for precisely this reason.

Certain names may hint at an entire belief system or only certain aspects of a character whether that character turns out to adhere to that association or not. The more unusual or uncommon the name, the stronger the association. Few of us, for example, would name our character Hitler or Mandela without expecting some association to accrue, and without providing some sort of reason in the plot why we have chosen to do so.

The web is replete with lists and articles providing and explaining the origin of names, their meaning and history. Books on naming conventions, available at any bookstore, are also a good place to start hunting for that all important handle of characters.

Summary

Choosing the right name for your character is the first step in developing a unique and effective character identity.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, or have a suggestion for a future one, kindly leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

November 17, 2013

What is a Time Lock?

Time-Lock:

A time lock, in story telling, is a structural device that imposes a limit on the time allowed for a problem to be solved. Failure to do so in the allotted time, renders the story goal unachievable, and the mission a failure.A time lock, is often, quite literally a clock, counting down to zero before the bomb explodes. Examples abound: In Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove, the pilots flying the aircraft carrying an atomic bomb that will start the next world war have to be persuaded not to drop it before they reach the target site; in Next, Nicholas Cage has to foil the villain’s plans before a nuclear device wipes out LA.

In my own novel, Scarab II: Reawakening, the Hero, Jack Wheeler, has to get to the quantum computer before the appointed time to stop it from running the programme that may destroy the world.

In 36 Hours the time lock is even more tightly woven into the story’s structure. With the invasion of Europe but days away, the Nazis have little time to extract the date and landing location of the Allied forces from James Garner. Although the story might still work by concentrating on how Garner is seduced into talking, the time lock imbues the story with an overall tension that could not be achieved otherwise.

In Armageddon, a shaft has to be drilled and a bomb placed deep into the comet that is headed for earth…

In The Bridge on the River Kwai, not only must the bridge be built under the most trying circumstances, but it has to be finished by a specific date. The highlight, which shows not only the bridge being completed at the ninth hour just as the train arrives, but also in time for the explosion to occur that sends both bridge and train crashing into the river, has rarely being surpassed in effectiveness.

Summary

A time lock in a story defines a specific time period for the main story goal to be achieved in order to avoid calamity or failure. The device increases tension and helps to maintain the forward thrust of the story.

November 10, 2013

How to Write Character Descriptions

Character Description:

In a typical screenplay, character descriptions should be written when the characters first appear on the page. These descriptions should be brief and to the point. This post looks at this often misunderstood aspect.There are only two things to establish about a character from the outset–gender and age. Laborious, pedantic descriptions about specific physical attributes, cars and pets, musical instruments played, should be avoided. If a characteristic is crucial to the story, state this succinctly. If, for example, one of your characters, say, Ben Brandt’s graceful movement somehow ends up saving his life then foreshadow this in your description of him: Ben Brandt was built like an army barracks shithouse but moved with the grace of a ballerina.

Lengthy, unmotivated descriptions slow the forward thrust of the story and betray the writer’s inexperience.

So why do so many writers include them in their screenplays? Because it is far easier to describe a character’s varied physical attributes and traits than to reveal them adroitly through dialogue and action in a scene.

Reference to physical stature, hair colouring, and weight, therefore, are only relevant if they foreshadow aspects of the plot, such as the stutter that causes the murderer to trip up at the end, or the lack of height that motivates a man to over-achieve in other areas.

This extends to emotional traits as well. Indeed, one of the best ways to make emotional and physical traits germane to the story is to interweave them and have them explain some future aspect of the character’s action(s).

This brevity of description extends to the novel and short story too, for much the same reasons. In her wonderful book on the craft of the short story, Inside Stories for Readers and Writers, Trish Nicholson offers us several examples of this skill. In Modus Operandi she describes a character’s physical size: “A big man, too–he had to duck under doorways. His hands were as wide as dinner plates. To see those long fleshy fingers you’d realize the strength in them.” This description is not only germane to the story but it foreshadows menacing aspects of the plot.

Summary

Character descriptions should be brief and germane. Describe only those traits of a character that serve as triggers to the plot, and do so succinctly.

November 3, 2013

Understanding Positive and Negative Story Space

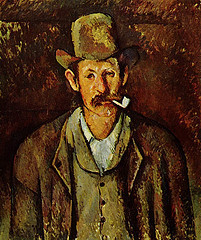

Positive and Negative Space:

In art, say in the painting of a portrait, positive space is the area occupied by the subject. The background, or surrounding material, represents negative space.Stories and scenes can also be thought of possessing these two characteristics. The story itself, the action, events and dialogue can be seen as positive space. It is everything that is “viewed” on the screen, or read on the page. But the characters and the world they inhabit do not begin on page one and end on the last page. There is a sense in which they, and the world they inhabit, exist prior to the story commencing and that they continue to exist after the book or movie has ended, in the mind of the reader or viewer, at least. This aspect may be considered as constituting negative space.

In The Godfather II, Michael sits alone, isolated from family and friends, staring into emptiness, yet we feel that his life will continue past this point. In my forthcoming novel, The Level, a man wakes up in a pitch black space, bound to a chair, with no memory of who he is and how he got there. Clearly, the backstory here is germane to our understanding of his situation and to the plot in general—negative space. How far this negative space extends in either direction varies greatly. This aspect differentiates it from positive space, which concerns itself with the “finite” past and the “here and now”.

In his book, Screenwriting Professor Richard Walter suggests that another way to view this is as story versus plot, with story being the negative space which exists beyond the start and end, and plot which concerns itself only with actual occurrences on the screen or page—positive space.

Determining the boundaries between negative and positive space helps the writer find the true beginning and end of her story, as well as what to leave in or omit, right down to the level of a scene. This aspect of the craft is perhaps one of the most difficult to master but one of the most rewarding, once acquired.

Summary

Positive space concerns the actual words on the page, or shots in a movie. Negative space is the material that exists in an unstated but necessary form in the mind of the reader or viewer in support of the plot itself.

October 27, 2013

Small Action, Big Drama

A Matter of Scale:

In my younger and more chauvinistic years, I used to think that “Drama” referred to the slow and laborious true-to-life stories that the women folk in my life loved to watch on TV while knitting jerseys. This is a particularly embarrassing admission for a Greek man to make, since the word derives from the Greek, meaning “to do” or “to act”. Luckily I have moved on since these days, though I still have the jerseys, and yes, they still fit.As a writer of screenplays and novels, I have to focus constantly on the meaning of this word. In his book, Screenwriting, Professor Richard Walter of UCLA, writes: “(1) any action is better than no action, and (2) appropriate imaginative, integrated action, action complementing a scene’s other elements and overall purpose, is best of all.”

Action need not only be of the sort that involves Godzilla leveling cities, or King Kong swatting planes and helicopters from the top of a tall building. Action can arise in even the most ordinary or non-threatening of scenes. Richard Walter talks about one specific example, both funny and painful, that clearly illustrates this point.

In the Czechoslovakian film, Loves of a Blonde, two groups of labourers, one male and the other female, working on a project in a remote area of the Carpathian foothills end up dining in a dinning hall. Both the men and women are equally nervous about meeting each other. The scene isolates one man in particular who fidgets absentmindedly with his wedding ring. Suddenly, the ring slips from his finger and clutters loudly to the floor and begins rolling away.

Is the fidgeting subconsciously intended to conceal his marital status from the women? We suspect so. The man drops to his hands and knees and scrambles after the ring, past row after row of knees. So engrossed is he in his pursuit of the tale-tale object that he fails to notice that the knees he is shuffling past are no longer those of men but those of women! By the time he finally captures the elusive object and pops up from under the table like a jack-in-a-box, triumphantly holding the ring up in his hand, he finds himself amongst the very group of women he was he was trying to avoid seeing the ring!

The action itself is small in scale, but its emotional impact is huge, making for a scene that is fresh and inventive. It satisfies Professor Walter’s second observation of integrated action, quoted above, and exploits that age old maxim of “show don’t tell”. This is writing at its simplest and best.

Summary

Drama is action. Static scenes make for boring stories. While there is nothing wrong with largeness of scale, it should not be at the expense of smaller, well-observed actions.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, or have a suggestion for a future one, kindly leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

October 20, 2013

Writing Short Films

Shorts

Short films featuring stories that roughly run five to thirty minutes in length are one way for new writers to introduce themselves to the film industry. This post, based on Raymond G Frensham’s book, Screenwriting, discusses the shorter film format and offers some guidelines.Writing for short films requires different skills from the writer to those demanded by normal length versions. Like the short story, the short film is one of the most difficult formats to master, demanding precision, economy and compactness on the part of the writer.

1. One of the most important things to understand about short scripts is that the idea should fit its space. A short is not a longer story squashed to fit the allocated time. It’s not a sketch forcibly stretched to fit its format, nor is it a promo for some longer version of a future project.

2. The cardinal rules of screenwriting, such as making every sentence count and showing, not telling, are even more crucial in the shorter format. The writer has only a few pages to tell the story. Economy of form and execution are paramount. Swoop straight into the world and life of your protagonist. Explore a some crucial incident in your Hero’s life, which explains, informs and defines the wider story.

3. A twist in the tail tends to be more difficult to pull off in the short story format, since misleads and red herrings are less in evidence. Also, readers and audiences have grown wise and cynical in equal measure and are likely to predict all but the best crafted endings. So, look out for that.

4. Humour tends to work well in the shorter formats too, as long as it is not used as a sketch substitute.

The opportunities for producing short films are far more plentiful than they are with the longer formats. National and international TV stations often have slots for such shorter formats, not to mention the ubiquitous opportunities for showcasing work through the internet on sites such as YouTube. Despite denials, industry executives still see the short film as an opportunity to showcase their ability to make their first feature films. So should you.

Summary

The shorter film format requires a different approach to that of the feature script. This post briefly looks at some of these differences.