Stavros Halvatzis's Blog, page 52

May 11, 2014

How to X-Ray your Story

How to X-Ray Your Story

In his book, The Art of Dramatic Writing, Lagos Egri provides us with a succinct way of x-raying our tales prior to commencing the writing of our story, in order to expose its essence, its genetic code. We do this by seeking to identify the story premise (or, what I call the theme, or moral premise—moral because it is the moral of the story and judges behaviour according to a higher justice).Here are some examples of the (moral) premise:

King Lear: Blind trust leads to destruction.

Ghosts: The sins of the fathers are visited on the children.

Romeo and Juliet: Great love defies even death.

Macbeth: Ruthless ambition leads to its own destruction.

Othello : Jealousy destroys itself and the object of its love.

Tartuffe: He who digs a pit for others falls into it himself.

We can see from the above that the moral premise/theme reveals a character’s inner motivation and is intimately linked to his inner journey. The protagonist is relentlessly driven by this motivation to complete that journey. It’s important to note that the moral premise contains a direction and momentum, emerging from the conflict between the character’s emotions, other characters, and the world.

With that in mind, we can say that the premise = Character’s emotion + Conflict (or direction) + Results (the end).

If we plug in the premise/theme of The Matrix into this formula, for example, we may come up with: Self-belief leads to victory over the enemy.

With the theme/moral premise firmly in place, we can generate the log-line (the one-line synopsis of the plot, as opposed to the moral of the story), before moving to the synopsis itself, the treatment, and the fist draft of our screenplay, or novel.

But these latter topics are the subject of a future article.

Summary

The moral premise, or theme, is the force that drives the protagonist to complete his inner journey.

Image: Jess

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

May 4, 2014

Marketing Your Work

Marketing Your Project:

Indies, primarily independent authors, filmmakers, artists, and photographers, wear more than one hat. We create and market our work, too. This is hard work. The up side is that we get to keep the earnings we generate.Becoming expert marketers is not a task creative people take to easily, especially in the constantly changing landscape of Facebook, Pinterest, Twitter, StumbleUpon. The “shop fronts” are growing by the month.

Let’s face it, we’d rather be sipping cappuccinos or tea while typing out our 1000-2000 words for the day, than figuring out the best marketing angle for our new film or book. Unfortunately, we don’t have a choice. No marketing, no sales.

Imagine having sixty thousand followers, as some do. Tweeting about the release date of your new book or film has the potential of reaching a great many people. Factor in that your tweet may, in turn, be retweeted by some of your sixty thousand followers, and you can see how the word can spread.

Following people randomly, however, is time consuming. Only 10% to 20% of people you follow, follow you back. The trick is to follow a high volume of people daily until your number of followers grows to a respectable size.

In this article I want to highlight a method for acquiring Twitter followers more easily—through a site such as blastfollow: http://brianmcarey.com/blastfollow/. This is a free website that allows you to follow by hashtag. You type in a word relevant to your blog, book, or film, do an automatic search, then do an auto-follow. If you follow about 1000 people per day you’ll get at least 100-200 followers back. Maybe more.

Here’s the sort of hashtags I use to identify potential followers who can benefit from my blog on writing:

#AskAgent

#AskAuthor

#AskEditor

#BookMarket

#BookMarketing

#GetPublished

#IAN1 (Independent Author Network)

#IndiePub

#PromoTip

#Publishing

#SelfPublishing

#WriteTip

#WritingTip

I’ve acquired an extra 2000 followers in a few days so far, using this method.

You can too.

Summary

Acquiring a large twitter following is one way to spread the word about your work. Using a site such as blastfollow can help you achieve this.

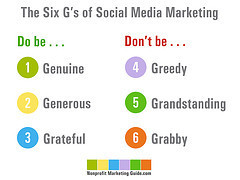

Image: Kivi Leroux Miller

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

April 27, 2014

Big Story Ideas

Big Ideas:

Ideas. The fuel that powers civilizations and progress—social, political, economic, scientific, technological. Great ideas are innovative, lead to success, generate excitement.And so it is with stories too. Hollywood calls such ideas High Concept. Pitch a truly big idea in Hollywood and producers and executives sit up and take notice. Suddenly, you are doing lunch with all sorts of people who want to hitch a ride on your wagon.

So, how do you get that big story idea? And just what is it, actually?

The truth is that ideas, or seeds of ideas, can come at you anywhere, anytime— from smells, sights, sounds, touch, distant memories. But is there a way to force-generate a truly big idea, cold, so to speak?

Here again, there are many prompts, many paths to the land of big ideas. News and documentary programs, magazines, websites, books.

As a science fiction writer, I tend to sniff around in places were great scientific ideas are already in the boiling pot. I recently purchased a magazine published by Media24, aptly titled: 20 Big Ideas. The magazine identifies 20 huge scientific topics that are currently in vogue:

The ongoing search for a Theory of Everything, Dark Energy, the Gaia Theory, Quantum Entanglement, Catastrophism, Chaos Theory, Consciousness, Artificial Intelligence—to name but a few.

These are the topics currently causing a stir in the scientific and related communities, through journals, magazines, television programs, radio stations, Internet forums, and the like.

Find a topic that fascinates you, explore the unanswered question surrounding it, and create your premise or log-line around that. If you are interested in the search for a Theory of Everything, for example, you should probably know that it has to do with trying to explain the entire spectrum of physical existence, from the very small-the quantum world, to the very large—cosmology. You should know that trying to incorporate gravity into the former is the crux of the problem.

The question is: what would the Theory of Everything be like? From there, you might think along the following lines:

What if a young theoretician working under the guidance of a supervising professor makes a startling mathematical discovery that will change the face of theoretical physics forever? What obstacles could you place in his way, and what would be the motives of the antagonist in trying to prevent him from achieving his goal?

The same initial process can be applied to the topics of Consciousness, Artificial Intelligence, and the other big ideas doing the rounds.

The next step is to develop the log-line, the structural skeleton of the story, and the one page synopsis along the lines suggested in numerous articles on this website, or others like it, before starting the actual writing of your story itself.

Summary

Big ideas make for big stories. Begin by tracking down big ideas through studying relevant journals, newspapers, conference papers, television programs, and the like, and create your log-line or premise based on one of them.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Andrés Nieto Porras

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

April 20, 2014

Three Acts, Many Stories

Three Act Structure:

In his book, The Screen Writer’s Workbook, Syd Field contextualises the three acts of a story by reminding us that each act performs a specific function and answers a specific dramatic question.The function of the first act is to set-up the world of the main characters and to foreshadow their conflicts, as well as to establish the protagonist’s goal. The dramatic question of the first act is: What is the protagonist’s initial situation that compels him to embark on the story goal?

The second act is defined by the dramatic context of conflict. This act pits the protagonist against the antagonist by placing both in a situation of mounting attrition, forcing the protagonist to adapt his skills, and face his inner weakness, in order to achieve his goal.

The second act is typically double the length of the first act, and is orchestrated by a midpoint: the moment in which the protagonist decides on whether to give up on his goal, or press on against mounting opposition. To do so, he has to dig deep to uncover his inner strength and, perhaps, defeat hidden demons.

Paradoxically, his renewed determination inevitably results in an increase in the amount of deadly opposition he encounters along the way. The dramatic question of the second act is: How does the protagonist keep his head above water in the face of mounting obstacles and conflict.

The third act is defined by the dramatic context of climax and resolution. It contains the so-called must-have scene: the final and deadliest clash between the protagonist and antagonist. The act unswervingly builds up to this must-have scene, the outcome of which yields the theme: if the hero looses then that which defeats him becomes the theme.

In Othello, for example, jealousy leads the Moor to murder his wife, thinking that she was unfaithful to him. The theme here is: Jealousy leads to destruction. The dramatic question of this final act is: will the protagonist, and all that he stands for, carry the day, or will he be defeated by the antagonist and his world?

A story, then, breaks down into three acts, which correspond to the beginning, middle and end of the tale, each of which has a specific function to perform.

Summary

A story typically comprises of three acts. Each act answers a specific dramatic question.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Ian Sane

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

April 13, 2014

How to Manage Character Conflict

Transitioning Conflict:

Staying with the work of Lagos Egri, and still on the subject of character conflict, this post examines this most powerful force that exists between characters. Egri informs us that there are four types of conflict in writing:1. Foreshadowing (good)

2. Static (bad)

3. Jumping (bad)

4. Slowly rising (good)

Foreshadowed conflict should occur near the beginning of the story and should point to the forthcoming crisis. In Romeo and Juliet, the warring families are already such bitter enemies that they ready to kill each other from the get-go.

Static conflict remains even, spiking for only the briefest of moments and occurs only in bad writing. Arguments and quarrels create static conflict, unless the characters grow and change during these arguments. Every line of dialogue, every event must push towards the final goal.

In jumping conflict, the characters hop from one emotional level to another, eliminating the necessary transitional steps. This is also bad writing.

Avoid static and jumping conflict at all costs, by knowing, in advance, what road your characters must travel:

Fidelity to infidelity

Drunkenness to sobriety

Brazenness to timidity

Simplicity to pretentiousness

The above represent two extremes—start and destination.

Transition

You must have transitions between states. Supposing a character goes from love to hate. Let’s imagine there are seven steps between the two states:

1. Love

2. Disappointment

3. Annoyance

4. Irritation

5. Disillusionment

6. Indifference

7. Disgust

8. Anger

9. Hate

If a character goes from 1 to 5 at once, this constitutes jumping conflict, neglecting the necessary transition. In fiction, every step must be clearly shown. When your character goes through steps 1 to 9, you have slowly building conflict. Each level is more intense than the previous one, with each scene gathering momentum until the final climax.

Summary

Foreshadowed, slow-rising conflict, which transitions from level to level, is the best way to orchestrate opposition amongst your story’s characters.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Philippe Put

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

April 6, 2014

Story and the Dimensions of Character

Character Dimensions:

In his book, The Art of Dramatic Writing, Lajos Egri points out that every object has three dimensions: Height, Width, Depth. Characters, on the other hand, have three extra dimensions.Egri begins with the most simple of the three: Physiology. To illustrate how physiology affects character, he provides examples of a sick man seeking health above all else, whereas a normal person may rarely give health any thought at all. He suggests that physiology affects a character’s decisions, emotions, and outlook.

The second dimension is Sociology. This deals with not only a character’s physical surroundings, but his or her interactions with society. He asks questions like: Who were your friends? Were your parents rich? Were they sick or well? Did you go to church? Egri constantly explores how sociological factors affected the character, and vice versa.

The most complex of the three is Psychology, and is the product of the other two.

In an industry obsessed with high concept and plot, it is important to restore the balance by placing equal focus on character. According to Egri, it is character, not plot, that ought to determine the direction of the story.

The Bone Structure of Character

Egri provides categories for developing character. Collectively, he calls these categories the character’s bone structure. Filling out the specific details of each serves as a good start in creating a three dimensional character.

Physiology

Sex

Age

Height and weight

Color of hair, eyes, skin

Posture

Appearance

Heredity

Sociology

Class

Occupation

Education

Home life

Religion

Race, nationality

Place in community: leader among friends, clubs, sports

Political affiliations

Amusements, hobbies: books, newspapers, magazines

Psychology

Sex Life, moral standards

Personal premise, ambition

Frustrations, chief disappointments

Temperament

Attitude toward life

Complexes

Abilities

Summary

This post looks at Lagos Egri’s three dimensions that must be addressed in order to craft well-rounded characters: physiology, psychology, and sociology.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Ryan Baumann

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

March 30, 2014

Sell Your Story Through Character Conflict

Conflict Sells

The noted teacher and dramatist, Lagos Egri, provides some sage advice on the subject of character conflict and how to sell your story premise and drive your story forward.Remembering that the premise is a microscopic form of the story itself, Egri suggests we formulate our premise and start our story at a crisis point, which will be the turning point in our main character’s life.

In Ghosts, by Ibsen, for example, the basic idea is heredity. The play grew out of a Biblical quotation, which is the premise: “The sins of the fathers are visited on the children.” Every action, every bit of dialogue, every conflict in the play, arises out of this premise.

Egri states that the correct way to start a story is to involve your main character in conflict. Conflict not only drives the story forward, but it is the quickest way of revealing character in the shortest time.

Forcing opposing characters together is the best way of establishing conflict. Opposing characters should be militant, passionate, and active about their positions. Egri calls this process orchestration.

For example:

Optimist vs. pessimist

Miser vs. spendthrift

Honest vs. dishonest

Loyal vs. disloyal

Believer vs. non-believer

Agapi vs. Erotas

Militantly opposing characters make conflict inevitable. Two perfectly orchestrated characters will oppose, or, perhaps, even destroy each, other depending on circumstances, turning your story into a page turner.

Although opposing characters form the foundation of any good story, you should, before you start, determine why one simply cannot walk out on the other, while the conflict rages. Determine the precise nature of the unbreakable bond that keeps them together until the climax: is it revenge, hate, jealousy, pain?

Lastly, remembering that the premise is a microscopic form of the story itself, you should formulate your premise at a crisis point, which will be the turning point in your main character’s life.

Summary

Pit two actively opposing types of characters against one another—characters that are forced together in an unbreakable union, and as they struggle to break their bonds, they will spontaneously generate rising conflict and create the story in the process.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Tax Credits

Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

March 23, 2014

Writing Characters that Sell

Successful Characters:

At the end of his chapter on character development (Writing Screenplays that Sell), Michael Hauge offers the following useful summary:According to the Hollywood screenwriting guru, there are three facets to character: physical makeup, personality and background.

In order to create character identification and sympathy, Hauge suggests variously placing your lead in jeopardy, making her likable, introducing her to your audience early, making her powerful, witty, or good at her job, positioning her in a familiar setting, and granting her familiar flaws and foibles.

Ensure originality by performing adequate research on specific individuals whose lives seem authentic, unique, and interesting; go against cliche by altering the physical makeup, background and personality to make your character less predictable. Pair her up with an opposite or contrasting character and cast her, in your imagination, assigning her role to an actor that is best suited to the part.

Remember that there are two levels of character motivation: outer motivation, which is the goal the protagonist strives to achieve by the end of the story, and, inner motivation which is the reason she strives for the goal in the first place—the why to the what and how.

The sources of conflict are outer conflict—conflict between other characters and nature, and, inner conflict—conflict between warring aspects within the character herself.

The four categories of primary characters are: hero or protagonist, whose motivation drives the plot, the nemesis or antagonist who tries to prevent the hero from achieving the goal, the reflection or guardian who most supports the protagonist, and the romance character, who, according to Hauge, alternatively supports and quarrels with the hero.

Secondary characters are created as needed, in order to provide additional plot support, add obstacles, bring relief, humour, depth and texture to your story.

Summary

This post summarises suggestions for developing successful characters for your stories.

License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...

Image: OTA Photos

March 16, 2014

How to Fix Your Story with Archetypes

Archetypes:

In their book, Dramatica, Melanie Anne Phillips and Chris Huntley present a system for crafting stories, which, although somewhat counterintuitive, brims over with important advise. Here is a look at their archetypal characters, some of which vary in naming convention from those put forward by the likes of Joseph Campbell and Christian Vogler.The Protagonist (hero) and Antagonist, whom we recognise from other writers on the subject, form the first pair. The function of the protagonist is to pursue his goal identified towards the end of the first act and, hence, drive the story forward. The function of the antagonist is to try and stop him at all costs.

The next pair is Reason and Emotion. Reason is calm and collected. His decisions and actions are based solely on logic. Star Trek’s Spock is a typical example of this archetype. Bones, the ship’s doctor, on the other hand, wears his heart on his sleeve. Although a medical man, his opinions and actions are deeply emotional. He presents the emotional dimension of the moral premise.

The Sidekick and Skeptic represent the conflict between confidence and doubt in the story. The sidekick is the faithful supporter of the protagonist, although he may attach himself to the antagonist since his function is to show faithful support of a leading character. The skeptic on the other hand is the disbelieving opposer, lacking the faith of the sidekick. His function in the story is to foreshadow the possibility of failure.

The Guardian and Contagonist form the last pair of archetypal characters. The job of the guardian is that of a teacher and protector. He represents conscience in the story. Gandalf is such a character in Lord of the Rings. He helps the protagonist stay on the path to achieve success. By contrast, the contagonist’s function is to hinder the protagonist and lure him away from success. He is not to be confused with the antagonist since his function is to deflect and not to kill or stop the opposing character. George Lucas’s (Star Wars) Jabba the Hut is such a character. As with the sidekick, the contagonist may attach himself to the protagonist.

As a group, the archetypal characters perform essential functions within a story. Because they can be grouped in different ways, versatility can be added to their relationships.

Their usefulness becomes apparent when editing your manuscript, especially such argument sagas as Star Wars and Lord of the Rings.

Does your story ‘feel’ wrong?

Do your characters drift?

Identity your characters in therms of function to see if they belong to one or other archetype. Re-examine their function in your story. Are they doing their job as per their definition?

Of course, the task becomes more complex when the archetypes are mixed to create more complex and realistic characters, but even then, you may be able to pin-point their essential combinations and, therefore, work to improve their shared functions—but that, perhaps, is the subject of another article.

Summary

Understanding archetypes and their function in your story will assist you in troubleshooting loose and imprecise aspects of your tale.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Jason Vance

License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...

March 9, 2014

How to Outline Your Story

Outlining Your Story:

Whether you’re a pantser or a pedantic outliner (I’m somewhat of an in-betweener), I believe that having an overall snapshot of your story raises its potential quality and lessens the time it takes to write it.Here is the process I am currently following to outline my post apocalyptic novel, The Land Below.

I start by writing down my story’s premise. The story premise is a sentence, sometimes referred to as the logline by screenwriters, which captures the essence of your story—what is unique, but believable about it, highlights its major twists and turns, and ties the inner and outer journeys together, in part, through the knot of the moral premise, or theme.

I next tackle the outer journey. This is the what and how of your story. It defines the goal that the protagonist strives to gain by the end of the story. The goal, determined at the first turning point, is then kicked around by the midpoint and the second turning point, and is attained, or not, at the end of the final, must-have confrontation with the antagonist. Here I ensure that I have three or four major incidents in mind, including the inciting incident.

The inner journey, by contrast, is why the outer journey happens the way it does. It tries to explain the protagonist’s mental and emotional states and the decisions he takes that lead to the actions at the level of the outer journey. It also shows how and why the character changes during the story. It is a blow by blow explanation, of, at least, the turning points and the midpoint. It forces the writer to consider the reasons why the protagonist acts in the way that he does. I ensure that I have written a paragraph or two on the inner journey prior to starting the actual writing of my story.

The theme/ending: In the words of Lagos Egri, “The ending proves the theme.” Is your protagonist a good guy who manages to overcome the antagonist and save the world and win the heart of the girl he loves? If so, your theme may well be: Good guys carry the day. I always know the theme of my story before I begin to write it.

Lastly, I make sure I know who the main characters of my story will be. Each will represent a point of view and will drive the plot forward. A protagonist? Certainly. An antagonist? Check. A love interest? Yes. A mentor? A sidekick? I think of my characters in terms of the function they have to perform in the overall story argument. The details, the flesh and blood stuff, I build, from a series of traits and incidents, as I go along…

…so, while on the subject, back to outlining The Land Below!

Summary

The story premise, as well as the outer and inner journeys, the theme and ending, and cast of characters, are important elements to consider prior to commencing the writing your story.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Jo Guldi

Liecence: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...