Stavros Halvatzis's Blog, page 47

April 19, 2015

Episode, Season and Series Questions

In a previous article I suggested that each act in a story is driven by a question it seeks to answer. In the first act of The Matrix that question is: What is the matrix? In the second: Is Neo The One? And in the third: Can The One defeat agent Smith and his cronies?

In a previous article I suggested that each act in a story is driven by a question it seeks to answer. In the first act of The Matrix that question is: What is the matrix? In the second: Is Neo The One? And in the third: Can The One defeat agent Smith and his cronies?

But just as there are questions that frame each act, so there are questions that frame each episode and each season of a television series. These questions also apply, with small adjustments, to a book series.

In Gotham, the first season’s overall question is: Who will win the mob war, and how will that affect Jim Gordon’s attempt to clean up the city, as he continues to solve specific crimes, while the overall series question is: How does Bruce Wane’s attempt to find the killer of his parents shape his transformation into the Batman?

Each episode typically features a villain-of-the week and is driven by the dramatic question: How is this villain to be defeated? But the episode must also acknowledge the season’s question: How does the defeat of the villain affect the mob war? The death of the witness to the Wane’s murder, for example, would impact the entire series question — not that Cat is about to be killed off by the writers.

A book series, too, asks at least two overall questions. In my book series, The Land Below, the first novel’s dramatic question is: Will Paulie make it to the surface? My next book, The Land Above, is framed by the question: How does Paulie, and his companions, survive the horrors that lurk on the surface?

Each story in a series, then, is governed by several interlocking questions that not only drive a specific episode, but help keep the entire series on track.

Summary

Sketching in the overall series, season, and episode questions, prior to commencing the actual writing of the first episode or book, is the first step in mapping out the direction of your story and its characters.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday

Image: Floodllama

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

April 12, 2015

Save the Dog, Save the Story!

Save the Dog:

Engendering curiosity can be an effective structural device that prevents the story from flagging.In his book, Writing Screenplays that Sell, Michael Hauge reminds us that when a character or event is not fully explained from the outset, or the hero seeks the answer to some question or mystery not yet provided by the text, the reader keeps turning the pages in search for answers.

Whodunit murder mysteries obviously rely on our insatiable curiosity to discover the identity of the killer, a curiosity that increases with each red herring.

But less obvious examples include strange objects and actions, such as the recurring motif of the peculiar mountain in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, or the reason behind Gatsby’s parties in The Great Gatsby.

The longer the writer withholds a secret the more satisfying the revelation has to be.

In Silverado, the Kevin Kline character, Paten, is constantly asked, “Where’s the dog?” We have no idea of what dog the characters are talking about, and why it is so important.

But towards the end of the film we discover that Paten was once captured during a robbery because he took time out to try and rescue a dog. This does not only satisfy the audience’s curiosity over the unanswered question, it increases our sympathy for Paten, too.

Although the technique is not sufficient, on its own, to carry the entire weight of the story, used in concert with other structural devices such as turning points, pinches, and the mid-point, it does propel the tale towards its climax and resolution in a more compelling way.

Summary

To prevent your story from flagging, pose a series of questions at strategic points.

Image: Holly Victoria Norval

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

April 5, 2015

Thank You, Mr. Field.

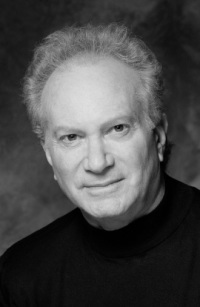

Syd Field (1935 – 2013)

Every once in a while I come across a nay-sayer – a writer who believes that the study of writing as a craft, and the study of structure in particular, is anathema.Such writers believe that greatness springs ready-formed from the inspired brain – that great writing, somehow, is handed down to us, preconceived and complete, like the Ten Commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai.

But even if it were true that genius does not require training and a writing methodology, where would that leave the majority of us typing away on our keyboards in the dark?

When I first started writing I knew little about structure other than the old Aristotelean advise that a story should have a beginning, middle, and end. My efforts were guided mainly by the aggregated jumble of books I’d read and films I’d seen.

I was not short on starts. Images, sounds, ideas came to me in a bewildering stream of disjointed segments, but like the pieces of a jig-saw puzzle taken from different boxes, they did not fit together in any coherent way.

Writing a story back then was a hit-and-miss affair. It was a sweaty, messy, grinding struggle that sometimes produced good passages. Mostly, however, the writing was bad enough to convince me not to give up my day job.

None of these passages survived.

It was only when I came across Syd Field’s, The Screenwriter’s Workbook, that the light finally flicked on. Here was a book that laid out the structure of a story in a series of beats governed by turning points that spun the tale around in a zigzagging manner, weaving in surprises to keep the reader interested until the climax and resolution at the end.

Suddenly, I could take an idea and plot it out before commencing the actual writing of it, regardless of whether the Muse had scheduled to visit me that day, that week, that month. My first novel, Scarab, which shot to the #1 spot in the Sci-Fi category on Amazon’s Kindle, is a result of this process.

It was the start of a wonderful journey that has spanned three continents and continues to this day. And though Syd Field is now only one of the many teachers I have followed, I’ll always remember him as my first.

And for that, I’ll toss the nay-sayers a shrug and say, thank you, Mr. Field.

Summary

Syd Field taught me the basics of story-structure.

March 29, 2015

How to Fix Lackluster Scenes

Fix It!

We’ve all written scenes which almost work. Almost, but not quite.Such scenes are difficult to fix since we can’t easily put our finger on what’s wrong.

The subtext seems to be in place. The dialogue seems to be communicating the plot and revealing character. Yet, something seems amiss. The writing seems too unimaginative, too lackluster.

In one of my recent classes a student presented us with such a scene. She had a strong female character giving instructions, in her high-tech office, to a male employee about some top-secret project. Everything seemed in place, yet the scene seemed stolid, dull. Something was definitely wrong.

My usual remedy in such cases is a series of variations – a change of location, a change of time period, and, in more stubborn cases, a change of character.

Luckily, here, a change of location did the trick. Instead of having the woman instruct her employee in her office, I suggested she does this in a hothouse, while trimming exotic plants. That way each comment could be accentuated by a snip of her pruning clippers. This would immediately add a deeper layer of subtext to the scene.

The student thought about it and ultimately decided to move the scene to an aviary, which worked just as well. It allowed the warm tone of the setting to add an interesting spin to the dialogue.

The result was an inspired scene that ticked all the boxes. Not only did the character’s actions grant an element of irony to the woman’s tough demeanour, the new environment lent an element of visual variety and contrast, too.

Summary

Consider changing the location, time-period, or background-action of your characters to pump up stolid, lackluster scenes.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday

Image: JD Hancock

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

March 22, 2015

What is Multiform Narrative?

Multiple Worlds:

In last week’s post I dealt with the category of multi-strand stories, drawn from my Ph.D thesis Multistrand and Multiform Narratives in Hollywood Cinema .This week, I’d like to talk a little about the remaining category – multiform narrative.

Both categories attempt to deal with the bewildering simultaneity, frenzy, and moral befuddlement of modern life, but whereas multi-strand stories do that through multiple strands featuring multiple protagonists not tied to a single plot, multiform narrative comprises of stories featuring a protagonist who inhabits separate realities in an existential and ontological sense.

This necessarily means that the protagonist splits up into several copies of himself, each occupying a different realm – whether it is the multiple universes of Donnie Darko, or the illusionary realities of dream and memory in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, or the virtual reality inside of The Matrix.

Open multiform narratives, such as Donnie Darko, stubbornly refuse to cue the viewer as to the preferential reality of the story. Donnie, for example, ostensibly appears to be both alive and dead in the movie, since the beginning shows him coming home from having slept the night on the golf course, only to discover that a jet engine has smashed into his bedroom.

But the end of the film replays the incident only this time Donnie sleeps in his bedroom and is killed by the jet engine.

Both incidents can’t be right in a single spatiotemporal framework. They present us with a paradox that can only be resolved if we place the two events in separate realities. In one universe, Donnie dies. In the other he lives.

Closed multiform narratives such as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and The Matrix, by contrast, differ from their cousins in the open multiform category in that they announce which world is real and which illusionary. Here, the filmmakers are at pains to show us Neo, Trinity, Morpheus, et al., entering and exiting the matrix through telephone lines, while Lacuna’s memory-erasing procedure cues and orientates us in a similar way.

Open multiform stories, then, tend to be more subjective and bewildering, whilst closed multiform narratives offer a helping hand through well-placed cues.

Both categories, however, succeed in reflecting the multiplicity and uncertainty inherent in lives littered with smart phones, video games, and multiple apps open on multiple screens – lives from which that much-needed sense solitude and aloneness seems forever banished.

Summary

Multiform narratives encode the bewildering complexity of modern life by showcasing multiple realities featuring copies of a single protagonist.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Dykam

License:https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

March 15, 2015

What is Multistrand Narrative?

As writers of novels or screenplays we are familiar with using character, setting, dialogue, plot, and genre, to convey theme, mood, and moral premise of our stories.

As writers of novels or screenplays we are familiar with using character, setting, dialogue, plot, and genre, to convey theme, mood, and moral premise of our stories.

But to what extent do we utilise narrative structure itself to reflect these last three elements?

In my Ph.D thesis, Multiform and Multistrand Narrative Structures in Hollywood Cinema, I point out that the canonical structure comprising of a beginning, middle, and end, first elucidated by Aristotle, involving a single plot and protagonist pursuing a specific goal, is not the only way to tell a story.

Multistrand stories, also referred to as ensemble, thread-structure, and multiple-plot narratives have become increasingly common in the past few of decades. Woody Allen’s films, for one, tend to employ this structure, as do romantic comedies such as Love Actually, Sex in the City, He’s Just Not That Into You, Valentine’s Day, and dramas such as Crash, Babel and Syriana.

Distinct from multiform narratives such as Donnie Darko, Jacob’s Ladder, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, which use multiple realities to keep us off center, multistrand stories portray the bewildering simultaneity and multiplicity of contemporary life by intercutting independent stories together, without subsuming them under a single plot.

Instead, equally-weighted strands cohere through a common theme. Each features its own protagonist and explores an aspect of the premise — love heals, for example — by having each individual story reach a similar or contrary conclusion.

Laying down several strands within a limited number of pages affects how much time the writer has available for introducing the various characters, and how those characters are portrayed. Vignettes tend to be the order of the day, here. Complexity within each strand, too, is kept to a minimum since the audience would have difficulty in keeping track of multiple plots involving multiple protagonists.

Taken together, however, the sheer number of independent strands encodes the bewildering intricacy, befuddlement, and moral ambiguity of contemporary life in a way that, perhaps, a conventional three-act structure fails to do. And therein lies the point.

Summary

Multistrand stories encode the bewildering multiplicity of contemporary life in their narrative structure.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Sukanto Debnath

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

March 8, 2015

Need a Great Villain? Triple-Dip him!

Villainous Intents:

We’ve all heard about the importance of a powerful antagonist in stories.An antagonist works against the protagonist to stop her from achieving the story goal. Together they form a dynamic pair whose ongoing battle forms the spine of the story.

We know that a well-written villain is clever and resourceful. He believes he is the hero of his own tale. He is often articulate, even eloquent, with a well-defined philosophy about life which motivates his actions and explains his loathing for the hero and her goal.

These characteristics emerge through his actions, but also through at least one great speech in which he explains to the hero, or another character, the depths of his villainous vision.

But it seemed to me that truly memorable antagonists needed something more – an extra ingredient that guaranteed their place in the annals of villainy. It was during one of my classes on writing that it struck me – great villains exhibit what may be described as a double, or triple dip. This is the moment when the character surprises the hero by plunging even deeper into darkness.

In the TV series, Outlander, an English knight, Black Jack Randall, has already proven to be a ruthless and cruel man capable of rape and murder. But in a crucial scene in a later episode he reveals to us the depths of his depravity.

He explains to his prisoner, Claire Randall, the Hero of the story, that the two hundred lashes, administered to a young Scot accused of stealing, were something beautiful, a work of art. We see the whipping as a flashback and flinch at the relentless violence of leather cutting into the torn, bleeding flesh of the young man – first dip.

Randall then seems to relent. He admits to Claire that he is filled with self-loathing for the man he has become, giving her hope that he will free her, and also, bolstering her cherished belief that any man is capable of redemption. But, suddenly, he turns and punches her in the gut, driving their air from her lungs. She falls to the ground gasping – second dip.

As if that’s not enough, he orders his reluctant soldier to kick her while she lies gasping on the floor, describing the kicking of a woman as something liberating – third dip.

These actions don’t only represent plunges into physical cruelty. They are an attempt to crush the spirit of the person they are directed against – Claire believes that Black Jack Randall can be saved. He proves to her he can’t. This isn’t only a physical blow, but also is a blow against her Christian belief in the ultimate Salvation of Man.

It is this triple-dip, combined with a relentless desire to destroy his enemy’s spirit that makes Black Jack Randall a truly memorable villain.

Summary

Double or triple dips, combined with a dark, relentless desire to crush the hero’s spirit, make for memorable villains.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday.

Image: Johanthan McIntosh

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

March 1, 2015

Do you Write Gut or Stomach?

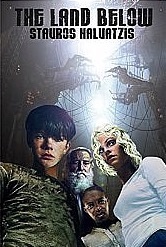

The Land Below

Most writers I talk to have at least two things in common: they want to be read and they want to write well. I’m one of them.We dream of writing a book or screenplay that’s so accomplished, that so touches the nerve of some current or emerging issue, shedding new light on its emotional, social, and political ramifications, that it shoots up the best-seller lists.

Let’s not fool ourselves — we all seek an audience. Even those of us who pretend, in our darkest moments, not to care, or who fool ourselves into thinking that if only the gatekeepers could understand the depth and complexity of our writing, they’d smile and nod and fling open the doors to the pantheon.

Popularity, of course, is no guarantee of quality. But neither is obscurity. Shakespeare was popular in his day. So was Dickens. Hardly a pair of slouches.

In my line of work as a teacher and writer I come across wordsmiths who’s idea of quality is language and subject matter that is impenetrable and stolid. Indeed, it seems that some make it a point to choose words that are obscure over words that are familiar, as if a large and exotic vocabulary, is, in itself, a sign of creative talent.

Of course, as writers we should cherish all words. Building a large vocabulary is a necessary goal, but we should not remain blind to the sensual quality of words — the notion that words of Anglo Saxon origin, in creative writing, tend to be more explosive and tactile, than their Latin or Greek-based counterparts.

Depending on the context, for example, “I punched him in the gut,” tends to be more forceful and tactile than “I punched him in the stomach.” In my newly released book, The Land Below, I’ve used both, but each time I was governed by character and mood.

We should ensure the words we choose are not, by their texture and nuance, broken bridges to the feelings and ideas we seek to express. And that, of course, requires we understand their origin as well as their meaning.

Finding a voice that speaks to the masses, while sharing the love of language and subject matter, is a worthy life-long goal for any writer. Living in an ivory tower with the echo of our own grandiloquence for company is not.

Summary

Sharing the love of words and subject-matter through clear and accessible language is a worthy goal for any writer.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday

Image: Stavros Halvatzis (c)

February 22, 2015

Want to Write Great Exposition? Hide It!

Exposition in story is a necessary evil. We have to know certain facts about a character or event if we are to make sense of the unfolding story. But exposition is a break in story momentum and should be handled deftly. A good way to hide it is to layer it with subtext.

Exposition in story is a necessary evil. We have to know certain facts about a character or event if we are to make sense of the unfolding story. But exposition is a break in story momentum and should be handled deftly. A good way to hide it is to layer it with subtext.

In his book, Screenwriting, Professor Richard Walter of UCLA provides several examples of good and bad exposition.

In Stand by Me, Richard Dreyfuss, a writer, relates past events in voice-over narration – often a quick and cheap way to bring the viewer up to speed. The scene, however, is static, filled with inertia, boring.

In American Graffiti, a radio dial and music immediately establish the time, place, and mood of the story. We learn through a few quick exchanges that Howard and Dreyfuss are planing to leave town in the morning. The setup occurs without lengthy and mechanical diversions.

In Silver Bears, several old mafiosi in bathrobes march down a plush corridor situated high above Las Vegas. They enter an enormous therapy pool and disrobe. Sucking on foot-long cigars they step into the water and proceed to discuss the sorts of things you’d expect to hear in the obligatory gangster boardroom scene. But placing the gangsters in a therapy pool and showing them as a bunch of naked fat old men, distracts us from the exposition and allows it to slip in surreptitiously.

In all three examples, context, mood, and necessary facts are relayed to the audience through exposition, preparing us for the story.

The first does it in a laborious and obvious way. It slows the action down and taxes the viewer.

The next two do so surreptitiously. They layer subtext in the setting and under the dialogue, keeping the audience engaged.

Summary

Load exposition with subtext to make it surreptitious and interesting.

Invitation

If you enjoyed this post, kindly share it with others. If you have a suggestion for a future one, please leave a comment and let’s get chatting. You may subscribe to this blog by clicking on the “subscribe” or “profile” link on the bottom right-hand side of this article. I post new material every Monday

Image: OUCHcharley

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...

February 15, 2015

Omit Needless Words

“Omit useless words,” William Strunk Jr. implored. Our writing will be more polished and powerful because of it.

“Omit useless words,” William Strunk Jr. implored. Our writing will be more polished and powerful because of it.

Unnecessary words make sentences lethargic by wasting time and energy. This is even more important in screenplays than novels where a lean, tight style cuts to the chase.

In his book, Your Screenplay Sucks, William M. Akers provides several examples:

A plush office. Sweeping views of the city through floor-to-floor glass windows.

“Glass” is redundant: A plush office. Sweeping views of the city through floor-to-floor windows.

Matthew falls to the floor with an expressionless face.

Better: Matthew falls to the floor, expressionless.

If something is understood in a story, don’t repeat it: He looked at the clock on the wall. Clocks are usually on walls: He looked at the clock.

Don’t repeat a point once it’s made: A hand taps Mark on the shoulder. He turns. Standing there is ALICIA SASSY, a 23 year-old Barbie doll with platinum-blond hair, a Playboy centerfold rack, and curves Beyoncé envies.

Barbie dolls are blond and stacked: A hand taps Mark on the shoulder. He turns. Standing there is ALICIA SASSY, a 23 year-old Barbie doll with curves Beyoncé envies.

Don’t repeat something already mentioned in the slugline:

INT. FERRARI – MORNING

Dun has slowed the car down to normal driving speed.

We know he’s in a car. Rather write:

INT. FERRARI – MORNING

Dun has slowed to normal driving speed.

Although this sort of cut-and-thrust brevity is less of a requirement in a novel, any story will benefit by having needless words omitted.

Summary

Ferret out needless words to make you writing leaner and more powerful.

Image: James Bowe

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...