Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 87

October 1, 2013

'Blair's Generals' (III): Some other lessons from a British general in southern Iraq

I

also was struck by Maj. Gen. (ret.) Andrew Stewart's summary in British Generals in Blair's Wars of

how he spent his time when the was the British commander in southern Iraq: 15

percent with his British forces, 20 percent with NGOs and other civilian

authorities, 25 percent with Iraqis, and 40 percent with the forces of other

nations: "It took that much effort to be able to understand them, and for them

to understand me."

Stewart

offers up what apparently was a hard-won lesson when commanding multinational

forces that report back to different capitals: "Unless you have an independent

manoeuvre unit that is unconstrained and whose rules of engagement you control,

then you will not attain the rapidity of reaction and the freedom of manoeuvre

you need on operations." In other words, don't fight unless you have a maneuver

unit entirely under your control, along with the rules of engagement governing

its actions.

All

in all, I would say that this is the best new book on military affairs I've

seen this year.

Stars & Stripes dumps 'Beetle Bailey'!

I know, the comic hasn't been relevant,

or funny, for many decades. Still, it seems kind of un-American for the U.S.

military newspaper to fire the Army's most famous slacker (except on weekends, when it is still

planned to appear).

I always thought ‘Beetle Bailey' was

stuck in the Army of the 1950s, when the strip was started, and where the

uniforms in the strip remain. ‘Doonesbury,' for the last decade, has done a much

better job of evoking contemporary military life. (I know, "MajRod" and some

others are still hatas. But perhaps they are stuck in the 1950s, too.)

September 30, 2013

'Blair's Generals' (II): Some surprises about American actions in the Iraq war -- like not telling the Brits about the surge!

British Generals in Blair's Wars offers some new views

of, and information about, the Iraq war. It made me wish I had interviewed more

Brits for my books Fiasco and The Gamble. On the other hand, I doubt

they would have told me back then, in the thick of things, some of the things

they say here. In sum, for the British, the Americans

appear to have been friendly but often unthinking allies, rather painful to

deal with.

Most

startling to me in this volume was the revelation

that L. Paul Bremer, III, the American proconsul in Baghdad in 2003-04, had

officially requested the removal of the British commander in Iraq, Maj. Gen.

(ret.) Andrew Stewart. This is discussed by Stewart and others. "I was charged

with not killing enough people," he recalls. "The CPA asked for my removal."

Another officer, Gen. (ret.) John McColl, adds that, "The demarche had gone

from Bremer to Washington to London without the military commanders being

consulted. Indeed, they, the [U.S.] military leadership, seemed to be content

with the British approach."

In

the spring of 2004, adds Col. (ret.) Alexander Alderson, when he and another

British officer tried to brief U.S. Army Lt. Gen. David McKiernan on counterinsurgency

doctrine, the American officer pounded the table and stated that he was not

going to face an insurgency. "Damn it," he shouted, according to Alderson,

"we're warfighting."

I

also was surprised to see Maj. Gen. (ret.) Jonathan Shaw's comment that the Americans

decided in December 2006 on "the surge" in Iraq later the same winter without

consulting the British: "This shift happened over Christmas 2006 after all our

Whitehall briefs which had focused on transition and reductions in troop

levels. I arrived with national orders to reduce our footprint, at a time when

the US was increasing its."

But

Colonel Alderson does note that as the surge occurred, "There was now a much

greater level of coherency in what the US was trying to achieve." I had

observed the same phenomenon in Iraq in 2007 and had tried to write about it in

The Gamble, but did not summarize it

as well as Alderson does in that one sentence.

(One

more to come.)

Feeling lucky?

Remember how the other day I worried that the risks of a nuclear incident

were increasing as the quality of personnel in the U.S. nuclear force

deteriorated?

Well, it turns out that at the

beginning of September, the deputy commander of the U.S. nuclear

force was

suspended and is under investigation for issues related to gambling.

Well, do ya?

Jonathan Pollard complaining about Israel

Jonathan Pollard, the convicted spy, had an odd piece over the summer in the

Jerusalem Post denouncing Israel for a variety of

failings, among

them this one: "Israel also remains the only country in the world ever to

voluntarily cooperate in the prosecution of its own intelligence agent,

refusing him sanctuary, turning over the documents to incriminate him, denying

that the state knew him, and then allowing him to rot in a foreign prison for

decades on end, cravenly forgoing its right to simple justice for the nation

and for the agent."

Does the Pollard case shed any light on the Snowden case? I

don't know.

September 27, 2013

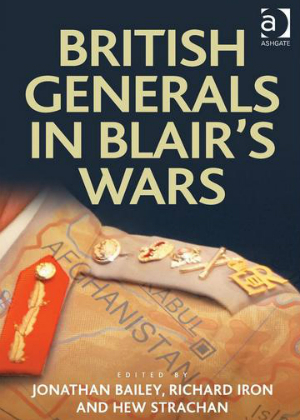

The British generals talk candidly about their role in the wars of the last 10 years

I've

just finished reading most of British Generals in Blair's Wars, a fascinating volume,

one of the most interesting I've read this year. As the title indicates, it is

a compilation of talks and essays by generals who played various senior roles

over the last 10 years in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere.

The

views are remarkably diverse. For example, some generals look to the Americans

as an example of a military that was more adaptive than the British, while Gen.

(ret.) Sir Michael Jackson calls the U.S. military "intellectually bankrupt."

(That may be due to a time difference: Jackson led British forces in Kosovo in

1999, while others saw the U.S. Army and the Marines finally get their act

together in Iraq eight long years later.) Maj. Gen. (ret.) Andrew Stewart, who

served in Iraq, states as a given that "aside from the USA, there are no armed

forces in the world that have all the capabilities needed to wage modern

warfare." Gen. (ret.) John McColl, who was deputy commander of MNF-Iraq, also

says enviously that American soldiers have more pride than do their British

counterparts. He adds that he found the American military to be generous and

open.

They

also are candid about each other in ways that American generals rarely are in

public. "The majority I would rate as fair," Lt. Gen. (ret.) Graeme Lamb, says

of his peers, "a few I would gladly join and assault hell's gate, and some I

wouldn't follow to the latrine."

The

talk by Lamb, who did four tours in Iraq and two in Afghanistan, is for me the

high point of the collection, in part because he addresses issues I spent much

of the last three years contemplating as I wrote The Generals. He says that generalship is about three things:

character, competence, and communication. "So do we select our generals on such

criteria? Don't be daft, of course we don't. We pull them up through patronage,

misplaced loyalty, self-promotion and a host of other rather tawdry reasons

and, occasionally, on ability; but it is not always the brightest and the best

that are selected for high office." The majority of people disagree with him,

he notes, but adds that they "lack the balls to say so."

The

book would be even more candid except that the Ministry of Defence refused to

allow the editors to publish the remarks of generals still on active duty.

"Indeed, even this book has had chapters by serving officers withdrawn on

orders of the MOD, including a chapter by the Vice Chief of the Defence Staff

on the difficulties of making strategy in the twenty-first century." All told,

six chapters were ordered withdrawn.

(More

to come.)

A personnel policy offering Marines a break from active service for up to 3 years

Amateurs

talk tactics, professionals talk logistics, and people who understand how the

U.S. military really works talk personnel policy. In other words, if you want

to change how our military works, change who gets promoted, and when.

In

that vein, a young Marine officer writes:

I'm

not sure if you have seen this or not, but it appears as though the Marine

Corps is experimenting with a new concept that will allow Marines to take a

break from active service to pursue their own desires with a guarantee of

returning to active service afterwards. It's called the Career Intermission

Pilot Program (CIPP). Link to the MARADMIN is here.

I'm a

company grade officer (CGO) in the Marine Corps and have recently started

working in the newly minted "Unmanned Aerial Systems Officer" field.

Having experience in this field should open many doors for careers outside of

the military. Knowing this, I've been following the thread of postings through

your blog over the last year and, like many others, I too have been wrestling

with the decision to stay with the Corps after this tour of duty. While it is

yet to be seen how the CIPP will play out, the start of this program

demonstrates that Headquarters Marine Corps is concerned about all this talk

over the retention of quality CGOs. For me personally, having an opportunity

like this would make me more likely to stay with the Marines despite many of

the concerns expressed by the CGOs that have contributed to your blog in the

past.

Guest War Dog of the Week: The quiet thoughtfulness of many military dogs

I'm often struck by how alert,

observant, and intelligent military working dogs look. The photo above offers

one example. You can imagine the dog is saying to the soldier, "Dude, did you

hear that sound?" or "Are you really sure you want to go through that door?" Or

even, "Hey man, before you go through that door, aren't you supposed to follow

procedure and communicate with your squad leader?" (In my

experience, dogs like humans to follow predictable routines.)

In the photo below, from Okinawa in

1945, the Marine and his dog look equally worried, even stressed. The caption

says the dog detected a Japanese machine gun nest waiting in ambush.

September 26, 2013

RAND's 'Paths to Victory': A valuable new study of what works in COIN campaigns -- and also of what doesn't

By Kalev I. Sepp

Best Defense office

of COIN best practices

As the Vietnam War drew longer and bloodier, a wry joke went

around that the statistics-minded McNamara ordered his staff to collect all the

numerical data reported from the war zone, feed it into a computer, and ask it,

"When will we win the war?" The computer clicked and whirred, and finally

replied, "You won three years ago."

The numbers-crunching by analysts that worked when hunting

U-boats, optimizing bombing patterns of industrial centers, and even

calculating outcomes of hypothetical nuclear wars, seemed to have no relevance

combating guerrillas in a "people's war." Intuitive masters of insurgency and

counterinsurgency, like Lawrence, Mao, Galula, Templer, and Kilcullen, seemed

to be the only viable sources of "how-to" guidance to deal with armed rebellion

and revolutionary warfare.

Now, the RAND Corporation has produced a revealing and

convincing study that makes numbers an analytic tool for irregular warfare

believable. RAND has researched and written on counterinsurgency, or COIN, for

five decades, and that experience shows well.

Paths to Victory: Lessons

from Modern Insurgencies builds on RAND's already notable Victory has a Thousand Fathers: Sources of

Success in Counterinsurgency. The same team of authors -- Christopher Paul,

Colin P. Clarke, and Beth Grill, joined for this edition by Molly Dunigan --

expand the number of case studies from 30 to 71, and begin earlier, in 1944,

carrying their examination to the present day.

This is impressive enough. The 48 pages of summaries of

insurgencies ranging from Greece and Malaya to Nagorno-Karabakh (in Azerbaijan,

1992-94) are valuable reading by themselves. Duly excluding coups and ongoing

conflicts, and including only state vs. non-state combatants, the list still

takes in fights in every type of terrain (mountains, jungles, deserts, cities),

among all cultures (Africa, Latin America, Central Asia, the Balkans, the Far

East, et alia), and with all militaries (both the insurgent and

counterinsurgent forces).

What is more remarkable is the depth and detail of the

authors' painstaking analyses of these counterinsurgencies, and their extensive

findings. These lists will likely ring true with veterans of all ranks of the

wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, whether they planned national-level campaigns on

a general staff, or patrolled streets and mountain trails with a rifle squad.

Holding to their stated purpose -- to discern "what

strategies and approaches give the government the best chance of prevailing" in

an insurgency -- the authors generate 24 COIN concepts that either strongly or

minimally support a positive outcome for a government fighting rebels. The

"strong" concepts may seem obvious, like border control and criticality of

intelligence. The surprise is which concepts are rated as minimally helpful,

such as the supposedly essential tenets of democracy, amnesty, and "putting a

local face on it."

There are also extensive lists of effective practices

utilized in winning counterinsurgency struggles (a significant and

sophisticated improvement over this writer's own 2005 list of "Best Practices

in Counterinsurgency" in Military Review).

One of the most common is government action to effect "tangible support

reduction" to the insurgency from the population and any external power. Conversely,

the authors' analyses show that the "crush them" approach by a government --

escalating repression and collective punishment -- has seen success in only one

out of three campaigns.

Given the ongoing debates about how the United States might

come to the aid of an ally fighting an insurgency in the future, Paths to Victory identifies 28

historical cases of a major external power contributing its own forces to the

counterinsurgent side. In a half-and-half split, the major power contribution

in 13 fights was limited to advisors, special operations forces, and air power.

The other 15 involved large-scale troop commitments by the major power. However,

further analysis of those cases shows that externally supported COIN forces

were no more effective than wholly indigenous forces. This may lead to a

re-evaluation of the decision to commit main-force U.S. and NATO units in

Afghanistan in 2002, after the Taliban had been defeated by Afghan rebel armies

aided by 400 able Special Forces troops and Central Intelligence Agency

officers, and compelling U.S. air power.

To persuade the reader that their conclusions are well

grounded, the authors devote much of Paths

to Victory to explaining the thorough methodological processes they

employed in their research. Liberal arts majors need to brace themselves for

entry into the realm of bivariate relations, factor stacking, and "fuzzy"

versus "crisp" sets of qualitative comparative analysis (QCA's to the

initiated). The reward is worth the reading, though, in the numerous well-drawn

charts and scorecards that illuminate the findings, and could readily serve as

tools for evaluating future COIN engagements.

Paths to Victory

has two additional merits. The authors establish and use straightforward, broad

definitions of counterinsurgency terms (or "victory"). They don't bend word

meanings to fit their results, or vice versa. They also avoid epistemological

judgment of any given COIN theory or doctrine. It would've detracted from the

presentation of their pragmatic findings. However, the military thinkers

concerned with those theories and doctrines -- such as the team hard at work on

the next version of FM 3-24,

Counterinsurgency -- will find fresh perspectives on COIN in Paths to Victory. The numbers often tell

a surprising story. Understanding them may be crucial to prevailing in the kind

of wars the United States is most likely to fight.

Dr. Kalev I. Sepp

lectures on defense analysis at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey,

California. He served as deputy assistant secretary of defense for special

operations,

was co-author

of the Iraq War "COIN Survey,"

and earned his Combat

Infantryman's Badge in the Salvadoran Civil War.

Why JOs leave: They see mediocrity rewarded and accountability neglected

By "A Captain in Afghanistan"

Best Defense guest ranter

During my time as a company commander, I have lived

according to a strict moral, ethical code based on principles and standards. I

will now pay for my adherence to the culture, regulations, guidance, and

principles upon which have been built the tenets of my ideology. This lesson I

wish to share as it encapsulates some of the ongoing junior officer dissent

that has been a common feature of Best Defense articles.

The groundwork: graduated on the Commandant's List for

Officer Basic Course and Captains Career Course, was the second-best platoon

leader, recently rated as the best staff officer in my parent battalion, and am

a finalist for a noteworthy scholarship. Not my opinion, but those on my

ratings.

Over the last eight months, I have led a company in Afghanistan

to conduct various engineer missions. An active-duty company deployed on its

own to fall under a National Guard battalion under an active-duty engineer

brigade.

I know my interpersonal skills are not mature and I do not

work well with others. I grew up in Airborne and Ranger units that demand a

high output from each officer. This mentality has been embedded in my psyche

and I cannot extinguish its flames. The driving factor to my unraveling has

been this lacking. Not an existence of toxic leadership, just hard

accountability for actions, to include my own.

The idealized version of my profession of arms is that we

are a highly-skilled, efficient group of individuals with thick skin that

weather the stress, emotions, fear, and boredom contributing to an overall

mission. However little or insignificant each part, each part only exists out

of necessity.

The lesson that I learned relating to the aforementioned

comments is this: We are a bureaucratic organization with rules, regulations,

and doctrine that are sound and have been well researched, but we continue to

flounder due to the lacking personalities and void of accountability. Understanding

the art and science of warfare is enforced in schools, not in our formations.

A commander requires a multitude of support, services, and

plans to achieve success in a highly amorphous environment. I have required the

same in my own environment. Although I have not approached the people

responsible for the lack of information, plans, etc., with the utmost dignity,

I am the one who will suffer. I am the one who is suffering.

My personal battle has been with peers on battalion and

brigade staffs. When I do not receive the information that I require, I demand

it as it is required for success. The demanding is my unraveling. I have found

myself in a pitched battle with officers junior to me calling me "bro," saying

that I do not have tact, and then going to tell their respective commander that

I do not play nice. I didn't know that I had to play nice. I thought I was

selected as a commander to achieve a mission within my higher commander's

intent.

I have achieved every mission with success, no loss of life

or limb, no lost sensitive items, drug/alcohol problems, sexual harassment, or

loss of equipment. We are more capable now that I had ever imagined achieving

the effects required in the operating environment.

No one wants an angry boss, but the boss is paid to get the

productivity that the occupation demands. There is a delicate balance and I

have failed to achieve that balance with my peers.

Perhaps this is why the top percentage is leaving the

military. Not spouse careers, salary, benefits, upward mobility, or awards. Existing

with other peers who do one-third the amount of significant output may be the

real factor. At least that is my factor.

The questions rolling through my thoughts at the moment are

these: Why should I lead a group of soldiers

when my peers fail to contribute significantly? When I hold others accountable

for their actions, why am I the one who will suffer on my broadening

opportunity, promotion, and selection for schools?

I view the civilian world as a group of individuals working

towards their own goal of a higher paycheck, a 40-hour workweek, minimal stress

after punching out for the day, and long weekends without cell phone calls,

recall formations, or deployments.

Accountability is not lost within the Army today, it is

misplaced. The subpar performers will continue to get promoted, attend schools,

and enjoy a paycheck every 15 days.

Thanks for listening.

"A Captain in Afghanistan"

is just that. This is an expression of his personal views and does not

necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Army, or of battalion staff

officers.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 437 followers