Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 89

September 20, 2013

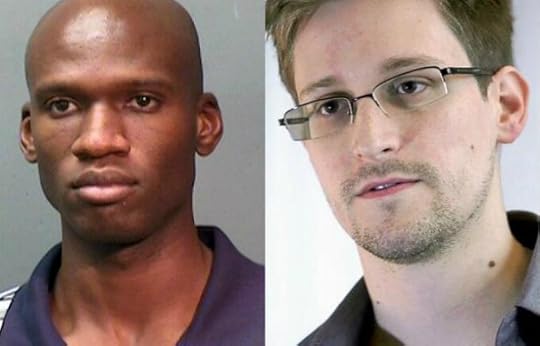

Snowden and Alexis: Just what is it with these lousy post-9/11 defense contractors?

Edward Snowden. Aaron Alexis. Two young defense contractors. Both

vetted by USIS. Both did terrible damage to the U.S. government.

I suspect the problem is the government

panic after 9/11. Standards were thrown out the window, along with

accountability. For a decade it was raining money around the Beltway, as long

as you were able to deliver warm bodies with the right credentials. And now, in

various unhappy ways, we are seeing the consequences.

Three questions with William Arkin, author of the new book 'American Coup'

Best Defense: Hi! An "

American Coup

"

? Oy. Bill, have you joined the ranks of the extremist

nut jobs?

William

Arkin: I call my book American Coup because I wanted to distinguish between what we normally think

when we think of a coup (a military takeover deposing civilian government) and

what we live under today, which is security above all else, a shadowy and

impenetrable elite in Washington making profound decisions that affect us

domestically and internationally, an absence of any kind of effective civilian

oversight from Congress, and a contempt for (if not a profound fear of) the

citizenry. When one of the most liberal presidents in our lifetime can come

into office and keep the Republican secretary of defense, the undersecretary

for intelligence, and three retired holdover four stars as the core of his

national security team, you know that there is a continuity of national

security policy more powerful than the elected. And now, almost a term and half

later, all of our grave national security problems in Washington -- cutting

defense spending, Syria's WMD, Snowden -- have a similar genesis in real

decisions not being made, no assumptions being questioned.

I'm not

arguing that any of these things aren't real problems, but WMD? It just fits

the skill set of the elite -- still. And trumps everything else, but brings

with it all the Cold War habits of deterrence, absolutism, and the ultimate

trump card. Is it really worth dropping everything over? What happened to

Obama's speeches about getting rid of our own (and Russia's) WMDs to instill an

international norm?

And

Snowden? With the Navy Yard attack, everyone's saying tighten up the system of

security clearances, look more seriously at contractors. Like Major Hassan

wasn't enough, or our Top Secret America series in the Washington Post, or even Snowden? The American coup is precisely

that the corporate world (and it isn't an industrial complex anymore; it's an

information complex) and the civilian experts and those in uniform are

practically interchangeable. And they need armies of technicians and others to

fight the forever war, the premise and the effect hardly even questioned.

BD: Sure, the Constitution has been under attack by well-meaning

if wrong-minded secret policemen, but do you really think we are that far over

the line?

WA: The

subtitle is "How a Terrified Government is Destroying the Constitution" and I

mean it. To label anything unconstitutional is to just play the game have-your-lawyer-call-my-lawyer

(a game in which Washington always wins), but the relationship of the federal

government to the states and the erosion of state control over law enforcement

(all under the name of homeland security and whole of government/whole of

nation) is real. Even the National Guard ("the militia of the several states"),

which is an institution that predates the Constitution and the United States

itself, has subtly been transformed since 9/11, not because of its exhaustion

in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, but more because the very reason to have a

Guard -- ensure that a "local" response is first, a response almost always seen

as more effective and more sensitive, and a guard against federal power and

encroachment ("tyranny," in old style words) -- is being undermined by its

enlistment in "regional" and national domestic response schemes. Even as bad as

Katrina was in 2005, I show in American Coup beyond a shadow of a doubt that the local responders were the

most effective, understanding the culture and geography and recognizing that

there was no insurrection going on, while Washington (and the Washington

agencies) practically saw it as an American battlefield. The inside story of

how the Bush administration tried to wrest control from the Louisiana governor

should be instructive. Again, in the unique design of the American

coup, it was the federal military commander on the

ground (Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré) who opposed takeover. The coup was fostered in

the White House and in the shadows of permanent government.

BD: So what should we do?

WA: People

in Washington don't even understand the totality of what goes on in Washington,

naturally leaving the experts -- wonks, SMEs, SESs, contractors -- in charge. They

can outwait any administration, explain away any program as "legal," reviewed,

and in accordance with our policy. The only thing that is going to change that

is if that stranglehold is broken. I think public anxiety over the NSA and

domestic drones, which is greater than public anxiety about WMD or the Middle

East, says a lot about how much Washington pursues a thrust that just isn't

reflecting American interests or concerns. From Tea Party to Occupy, everyone

hates Washington and the ever-growing and isolated DC elite. I would even

venture to guess that the poles of the gun control debate are as much about a

sense that Washington wants to control everything as it is about the Second

Amendment.

It all

boils down to accountability. A Snowden emerges, or a Navy Yard shooting and who is fired? What

is really changed other than the strengthening of the security apparatus, the

very one that failed in the first place? I know it's an exaggeration, but with

Americans already restricted from walking on certain streets in Washington,

with overlapping police departments and intelligence jurisdictions and homeland

security 10 years later still desperately searching for a mission, we're not

that far away from checkpoints, or national ID, or some kind of universal

biometrically-driven control system. If we just demanded that people in

government did their basic jobs, we'd be a lot closer to a better system.

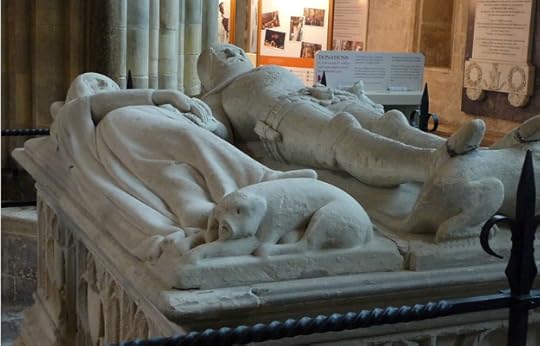

Guest war dog of the week: This soldier and his wife sure loved their dogs

That's Richard

FitzAlan, the tenth Earl of Arundel. He fought in France and Scotland and

commanded the English army for awhile. He also was incredibly rich. He died in

1375 or 1376 -- accounts differ. In their tomb, he and his wife are depicted

with their dogs sleeping at their feet

Philip Larkin wrote

a lovely poem about this tomb that ends with these lines:

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

September 19, 2013

The U.S. military, mythology, and Abu Ghraib: An intelligence officer's view

By Lt. Col. Douglas A. Pryer

, U.S.

Army

Best Defense guest columnist

We U.S. servicemembers tend to construct and preach

false mythologies about ourselves, perhaps even more so than the members of

other large organizations. This stands to reason. Our core business is, in

service to our nation, managing violence and this violence's effects. Being

human beings and not machines, we want to believe that when we kill, maim, or

injure other human beings, it is to good purpose. Deep down, we know sometimes

it isn't. But this doesn't stop us from always wishing that our violent actions,

and those of our comrades, serve a higher good.

So, in war, we try to convince ourselves that the

leaders and foot soldiers we are fighting are the worst people on the planet,

while our own leaders and comrades are the very best. And when U.S. troops commit

crimes, we work hard to believe that these crimes were the work of a few "bad

apples," of criminals who can never be completely screened from an organization

the size of ours. By thus disassociating ourselves, our military, and our

nation from these criminals, we hope to make ourselves feel less "tainted" by

their actions.

However, this very human, very understandable tendency contains a

profound danger: If we fail to see ourselves truly, if we wish away some of the

causes of some of our comrades' worst actions, we can cripple our ability to

reduce the chance of such misdeeds happening again.

One prominent example of potentially dangerous

myth-building can be found in this summer's issue of Parameters. George R. Mastroianni's "Looking Back: Understanding Abu Ghraib" sets out to

revise current narratives about the Abu Ghraib scandal.

Mastroianni, a psychology professor at the U.S. Air

Force Academy, says there are two competing narratives about Abu Ghraib, the

"bad apples" and "bad barrel" narratives. The "bad apples" narrative places the

blame for the scandal's crimes on Staff Sergeant Ivan Frederick, Specialist

Charles Graner, and the others convicted of crimes. He claims that the "bad

barrel" interpretation, which places the blame for these crimes on higher-ups

and turns the criminals into victims, is the dominant narrative. This is thanks

to "sensational" stories provided by journalists such as Seymour Hersh, lawyers such as Gary Myers, and academics such as Phillip

Zimbardo. He then offers a version that falls between these two narratives.

This sounds reasonable, unless one believes that

the dominant narrative already places blame on both "bad apples" and a "bad

barrel." When seen in this light, Mastroianni's real motive becomes clear: He

desires to do away with the idea that the Bush administration and certain

senior military leaders were even indirectly responsible for the Abu Ghraib

scandal.

According to Mastroianni, the crimes at Abu Ghraib

had nothing to do with so-called "enhanced" interrogation techniques (EITs). He

says that the facts of the cases that were prosecuted "do not comport with the

interpretation of Abu Ghraib as an example of the pernicious consequences of

American 'torture' policy, or as evidence of the migration of enhanced

interrogation techniques from Guantanamo to Iraq." He argues that, yes,

superiors were to some degree to blame for abuses at Abu Ghraib, but only

inasmuch as they produced "chaotic and confusing policy changes" and failed to

adequately supervise soldiers.

This thesis is more than misleading. It is wrong.

It ignores the fact that EITs undeniably migrated from Guantanamo Bay (Gitmo)

and Afghanistan to Abu Ghraib. It ignores documented cases of abuse at Abu

Ghraib that, while unprosecuted, definitely involved EITs and intelligence

collection processes. And it assumes away any link between the widespread use

of degrading, dehumanizing tactics at Abu Ghraib and the photographed crimes

that occurred at the same time.

Here is a fraction of what we know about the

migration of EITs to Abu Ghraib and "the pernicious consequences" of this

migration:

On December 2, 2002, former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld

approved for use at Gitmo such EITs as "Removal of clothing," "The use of

stress positions (like standing) for up to four hours," and "Using detainee

individual phobias (such as fear of dogs)." He rescinded this policy on January

15, 2003, when some service lawyers protested.

In August 2002, Company A, 519th Military Intelligence Battalion,

began running interrogation operations at Bagram, Afghanistan. Their

officer-in-charge of interrogations, Captain (CPT) Carolyn Wood, received a

faxed list of EITs from Gitmo in December 2002. In January 2003, her

interrogators were authorized by Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) 180 command

policy to implement such EITs as "Removal of Clothing," "Stress Positions," and

"Exploiting Fear of Dogs."

A few months

later, CPT Wood deployed with her company to Abu Ghraib. On her own authority,

CPT Wood told her interrogators that they could employ "Sleep Deprivation" and

"Stress Positions." She later testified: "Because we had used the techniques in

Afghanistan, and I perceived the Iraq experience to be evolving into the same

operational environment as Afghanistan, I used my best judgment and concluded

they would be effective tools for interrogation operations at AG." A number of

soldiers testified that her interrogators also continued to direct guards to

remove prisoners' clothing.

CPT Wood submitted

a draft interrogation policy to CJTF-7, the highest military command in Iraq.

According to Wood, she had plagiarized this draft policy from that used by the

elite Special Mission Unit (SMU) task force in Iraq. This SMU's policy, in

turn, was derived from the interrogation policy of the SMU in Afghanistan.

Wood's draft policy and Gitmo's April 2003 interrogation policy heavily

influenced CJTF-7's September 14, 2003, interrogation policy, which included

nine EITs that could be used with the approval of the CJTF-7 commanding general,

Lieutenant General (LTG) Ricardo Sanchez.

The revised CJTF-7

interrogation policy of October 12, 2003, continued to require interrogators to

request EITs from LTG Sanchez. Sanchez approved the EIT of "Isolation" on at

least 25 occasions. Additionally, Colonel (COL) Thomas Pappas, the 205th MI

Brigade commander, testified that he believed (wrongly, according to Sanchez)

that Sanchez had delegated to him the authority to approve "The Use of Military

Working Dogs" as part of interrogation plans, which Pappas then did.

This October

policy stated that interrogators needed to control "all aspects of the

interrogation, to include the lighting, heating and configuration of the

interrogation room, as well as the food, clothing and shelter given to the

security internee." This led some interrogators to believe they could employ

such EITs as "Removal of Clothing" on their own authority.

CIA operatives

employed EITs during interrogations at Abu Ghraib. On November 4, 2003, a

detainee died during an abusive CIA interrogation. The Fay Report, the summary

of the Army investigation into intelligence activities at Abu Ghraib, said:

"CIA detention and interrogation practices led to a loss of accountability,

abuse, reduced interagency cooperation, and an unhealthy mystique that further

poisoned the atmosphere." Shortly after taking office, President Barack Obama

declassified three legal memoranda (the "Torture Memos") listing EITs and

justifying their use by CIA personnel.

According to

multiple soldier testimonies, COL Pappas and Lieutenant Colonel Steve Jordan,

the officer-in-charge of all intelligence operations at Abu Ghraib, saw naked

detainees at the prison's hard site and didn't stop the practice. The Fay

Report confirms that the use of nudity to support interrogations was a

technique imported to Iraq from Afghanistan and Gitmo. It adds: "The use of

clothing as an incentive (nudity) is significant in that it likely contributed

to an escalating 'de-humanization' of the detainees and set the stage for

additional and more severe abuses to occur."

Most of the convicted crimes and other abuses occurred in the hard

site's Tier 1A, where interrogation subjects were held. Of the 44 abusive

incidents that were reported at the hard site, the Fay Report catalogs more

than half of these as involving interrogators or military intelligence

processes.

It is possible that Abu Ghraib's prosecuted crimes

would have happened without "Removal of Clothing," "Stress Positions,"

"Exploiting Fear of Dogs," and the other degrading EITs brought there from

other theaters. However, that interpretation stretches the limits of credulity.

A far more credible explanation is that the systematic, degrading treatment of

prisoners was one of the factors that created a slippery moral slope and

enabled worse crime. This is also the apparent pattern of abuse at several

other detention facilities employing EITs in Iraq and Afghanistan at the time,

including facilities at Bagram, al Qaim (Forward Operating Base Tiger and

Blacksmith Hotel), al Assad (FOB Rifles), Mosul (Strike Brigade Holding Area),

and Baghdad (Camp Nama).

Once the genie of "degrading treatment of others"

is unleashed from its bottle, it is extremely difficult to put this genie back

in the bottle -- or to restrain increasingly atrocious conduct.

There are more minor problems of fact in

Mastroianni's essay. For instance, he reports that the suffocation of Major

General Abed Mowhoush in a sleeping bag at al Qaim, Iraq, was the result of a

"free-lanced" tactic. This tactic was actually a variation of the "close

confinement quarters" EIT that placed subjects in small boxes or coffins to

induce claustrophobia. Lewis Welshofer, the warrant officer who killed

Mowhoush, had even specifically recommended this technique to CJTF-7 for

inclusion in policy.

How could Mastroianni imagine that EITs didn't play

a significant part in Abu Ghraib abuse? His choice of sources is telling. He

cites material from a military investigative report only once, never mentions

specific interrogation memoranda, and doesn't reference any of the hundreds of

witness statements available to researchers. Instead, to support his argument,

he relies largely on one second-hand account, Christopher Graveline's and

Michael Clemens's The

Secrets of Abu Ghraib Revealed.

Graveline helped prosecute all but two of the

soldiers convicted of crimes at Abu Ghraib, and Clemens served as an

investigator for the prosecution. Secrets

of Abu Ghraib is well worth reading, though its title is a bit of a

misnomer. The book actually provides few facts that weren't previously

disclosed via other sources (though it does provide some new facts). What it

does most successfully is relate many of these facts as they pertain to the

prosecuted cases in a highly readable narrative. It also performs a service in

reinforcing the fact that the photographed crimes largely did not involve

interrogation subjects and that these particular crimes were not specifically

ordered by higher officials. Graveline and Clemens conclude that, on the

continuum between the "bad apples" and the "bad barrel" narratives, "criminal

culpability [for the crimes that occurred at Abu Ghraib] falls closer on the

continuum to the enlisted soldiers working the night shift who were identified

and prosecuted."

That is a reasonable conclusion. But, "criminal

culpability" is not the same thing as "moral responsibility." Just because the

moral responsibility of senior leaders for the crimes at Abu Ghraib didn't

cross the threshold of what existing law deems prosecutable, that doesn't mean

this responsibility is absent. In the case of the abuses at Abu Ghraib, it

clearly is present.

It is truly easy to sympathize with Mastroianni's

wish to absolve senior leaders from any responsibility for the Abu Ghraib

scandal. This scandal was an exceedingly ugly, twisted episode in our nation's

history that no one but our enemies are glad occurred. It is thus doubtful that

he deliberately distorted and cherry-picked facts from mostly secondary sources

to support his desired narrative. Rather, being human, he looked only as deeply

as he wanted to look and so saw only what he wanted to see.

In the final analysis, Mastroianni writes very

well, and his attempt to reevaluate existing narratives is laudable. No narrative

should be deemed sacred. But he would have performed a greater service if he

had held up a more polished mirror that clearly reflected, warts and all, the

roles that senior leaders played in creating one of our nation's greatest moral

defeats. Only via acts of sometimes painful self-awareness can we see ourselves

clearly and, hopefully, prevent future Abu Ghraibs.

Lieutenant Colonel Douglas A. Pryer

is a counterintelligence officer who helped manage interrogation

operations for Task Force 1st Armored Division in Baghdad when the

Abu Ghraib abuses were occurring. He is the author of the Command and General

Staff College Foundation Press's inaugural book,

The Fight for the High Ground: The U.S.

Army and Interrogation During Operation Iraqi Freedom, May 2003 - April 2004.

The views expressed in this article are those of

the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department

of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

How deep runs the digital divide?

And is the distance between the

post-Internet generation (who are operating the country) and their pre-Internet

elders (who think they are running it) the generation gap of our time?

I suspect it is far deeper than we

think. This is not just a matter of different attitudes toward Edward Snowden.

I am guessing that growing up digital changes a lot of views and attitudes, and

even perhaps how the human mind works.

Churchill on the Pathan worldview

I generally am underwhelmed by Winston

Churchill's writings about India, but I do think he captures a thought well

when, in My

Early Life, he

summarizes the Pathan/Pashtun worldview: "Every man is a warrior, a politician

and a theologian."

September 18, 2013

Moral courage: Three Army lt. cols. call out their service for dangerous hypocrisies

They're

speaking truth to power in the new issue of Military

Review: The best of a good issue is an article titled "The Myths We Soldiers

Tell Ourselves."

Written by three lieutenant colonels (one retired, two on active duty, all

steeped in ethical studies), it detects a significant discrepancy between the

Army's stated values and its actual behavior:

The biggest problem with the Army Values is how they are

sloganeered. By simply saying them, we soldiers frequently delude ourselves

into thinking they make us more ethical, like they are a talisman. Indeed, they

can actually set the stage for unethical action by inspiring moral complacency

and allowing us to justify nearly any action that appears legal.

The authors are

especially concerned by the failure of the Army to hold accountable soldiers

involved in the torture and murder of prisoners. For example, they note, "Of the 100 detainees who died in U.S. custody between 2002

and 2006, 45 are confirmed or suspected murder victims. Of these, eight are

known to have been tortured to death. Only half of these eight cases resulted

in punishment for U.S. service members, with five months in jail being the

harshest punishment meted out. This is only a summary of the most extreme

cases."

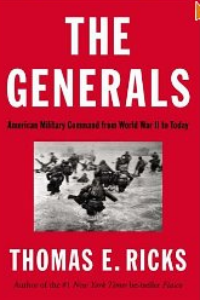

My reply to Col. Fivecoat in Parameters

Parameters very

nicely ran my

response to Lt. Col. Dave Fivecoat's article about some aspects of my

book The Generals. Here

it is:

Thank you for running Lieutenant Colonel David G.

Fivecoat's essay on "American Landpower and Modern US Generalship"

(Winter-Spring 2013). I don't agree with everything he writes, but nonetheless

am pleased to see Fivecoat's article because it is exactly the type of work I

hoped my book The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to

Today would provoke. I had thought that General Brown's articles in ARMY

magazine might launch such a discussion, but that magazine shied away from

engaging, without explaining why, as if discussing the quality of leadership

in today's Army somehow was impolite.

Most of all, I am fascinated by Fivecoat's finding (page

74) that leading a division in combat in Iraq seems to have hurt an officer's

chances of promotion. That worries me. What does it mean? That discovery of

his indicates that the Army of the Iraq-Afghanistan era is out of step from the

historical tradition that for an officer, time in combat is the royal road to

advancement. I cannot think of other wars in which service in combat hurt an

officer's chance of promotion. It is, as Fivecoat almost (but not quite) says,

worrisome evidence that the Army for close to a decade persisted in using a

peacetime promotion system in wartime.

In addition to breaking new ground intellectually,

Fivecoat's article is also courageous. It is one thing for me, a civilian

author, to question the quality of American generalship in Iraq and

Afghanistan. It is quite another thing for an active duty lieutenant colonel to

do so, especially since the Army's official histories have tiptoed around the

issue of the failings of senior leadership in our recent wars.

Two final observations:

I think Lieutenant Colonel Fivecoat lets today's Army off

too easily on its lack of transparency. To me this reflects a bit of drift in

the service, a loss of the sense of being answerable to the nation and the

people. Being close-mouthed about its leadership problems gives the impression

that the Army's leaders care more about the feelings of generals than the

support of the American people.

Finally, I have to question Fivecoat's assertion

that minimizing disruption optimizes performance. It wasn't the case in World

War II. Why would it be the case in Afghanistan or Iraq? It may be-but it

remains an unproven assumption, and to my mind, a questionable one. The

opportunity cost of averting disruption can be large, because such passivity

(or "subtlety," as he terms it) results in the apparent rewarding of

risk-averse or mediocre commanders. What would Matthew Ridgway say about such a

policy of minimizing disruption?

Thank you again for running such an illuminating and

thought-provoking article.

Soon: Fivecoat fires back!

The FBI file on the nature of leadership, the Navy file on busting former skippers

Nothing really surprising in the

FBI list, but

worth reviewing.

Speaking of leadership, the former skipper of the USS Mustin was busted for allegedly accepting bribes (and the services

of prostitutes) from a Navy support services contractor.

September 17, 2013

A Marine captain lists 10 things he wishes he knew before commanding a company

Capt.

Lucas Balke writes in the September issue of the Marine Corps Gazette that there are 10

things he wishes someone had told him when he was a lieutenant. (I really like "what

I've learned" articles, and I also am happy to highlight this article because

I've been hard on the poor old Gazette in recent years.) Here they are:

Plan

now to command a company.

Start

collecting PME items.

Read

10 pages a day.

Become

an expert regarding one battle.

Start

constructing your "perfect" field exercise.

Enable

your Marines to be self-sufficient.

Prepare

your Marines to be dismounted

infantrymen.

Trust

your NCOs.

Be

prepared to fight tomorrow's counterinsurgency.

Learn

to train for free.

Tom

again: What do you wish you'd known before taking your current position?

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers