Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 85

October 10, 2013

Army colonel becomes Indian chief

Retired Army Col. Kevin Brown, formerly

garrison commander at Ft. Riley, was elected chairman of the Mohegan tribe, which

is small in numbers but big

in the gambling world.

October 9, 2013

Reading a casualty report: U.S. fighting in Afghanistan as long as they can remember

Reading

this casualty report yesterday (Tuesday),

it occurred to me that we have been fighting in Afghanistan for about as long

as our soldiers there can remember. They were 12, 10, maybe even 7 years old

when the fighting began.

The

four soldiers killed on Sunday west of Kandahar were from a specially

trained team that engages Afghan women, reported Drew Brooks of the Fayetteville Observer. One of them, Lt. Jennifer Moreno, 25, was saluted by

the commander of the 75th Rangers as "a talented member of our team who lost her life while

serving her country in one of the most dangerous environments in the world. Her

bravery and self-sacrifice were in keeping with the highest traditions of the 75th Ranger Regiment."

This

is the first statement I can remember from the Rangers about a female soldier,

but I haven't gone looking closely at their statements, so I might have missed

some.

On

the other hand, I have read every single damn casualty statement released from

the Pentagon for the last 12 years. I am not sure how long I will continue to

do it. But I still feel like I shouldn't stop. Or maybe I can't.

How to deal with pompous sticklers

"Pomposity and pretentiousness received very short shrift

from him. When a general, a stickler for punctuality and held in no great

affection, paid an official visit, Cubiss arranged for all the clocks in the

camp to be put forward by five minutes. The great man arrived to find Cubiss, a

picture of exasperation, tapping his watch."

This

is from a good obituary in the Daily

Telegraph of Brig. Malcolm Cubiss.

(HT to down-under

PL)

Tales of the shutdown (III): On civilian faculty, federal furloughs, and quality

By Nicholas Murray

Best Defense guest columnist

I've just read

Professor Bruce Fleming's comments regarding PME during the furlough. I found interesting the similarity of his experience with mine. As we

know, almost all PME civilian employees were deemed non-essential and sent home

(though most have since returned to work). What struck me most was what has

happened to the students' classes after civilian faculty were sent home: Some

of the classes at the U.S. Naval Academy continued, some did not, depending on

whether there was the expertise to continue teaching those subjects. At the Command

and General Staff College, all of the classes continued despite the bulk of

faculty being furloughed. How was it that one institution could seemingly carry on as normal

while another felt it did not have sufficiently qualified faculty to continue,

except in a few areas where the active-duty faculty could effectively cover?

To find out how CGSC

managed this we need to look at what it does. Its main goal is to educate and

develop leaders for joint operations and functions, as called for by the

Goldwater-Nichols Act, and to teach critical and creative thinking in order to

prepare officers for the longer term. As such, classes follow a graduate-school

model of discussion seminars, led by an expert, where the free flow of ideas is

the norm in a small-group seminar setting (one over 16 being the model).

The problem is, last

week these classes were taught in groups as large as one over several hundred.

And by whom, given that the civilian experts were deemed non-essential? But, I

hear, CGSC is not a civilian graduate school, at least according to some, so the normal rules of graduate schooling don't matter.

The thing is, they

do: CGSC is accredited both as a graduate school and for teaching joint

operations. In fact, according to page 9 of CGSC's catalog, the school is a graduate degree granting college

and it legally must maintain accreditation for its classes from the

relevant civilian education authorities. This is true, whether or not all

officers take a degree. Accreditation is important, because it establishes

standards and best practices to ensure that students are getting a decent

quality of education. Thus, accreditation is not simply a bar to get over every

few years: it should be viewed as a pathway to the best education a school can

provide.

Yet, CGSC chose to carry on as

though nothing substantial changed. On the face of it, students continued to

learn and the government got to save a bunch of money. What could be wrong with

that? What does that have to do with accreditation? The answer to both

questions is, more than it seems.

The civilians furloughed from the

PME schools provide the bulk of the subject matter expertise for those

institutions. This is certainly true at CGSC. This fact is important, because

accreditation requires that faculty be qualified to a level higher than the

classes they are teaching. Thus, for graduate classes, that typically means

doctoral degrees are required. Of course, there are some active-duty personnel

teaching in the PME system who possess such a qualification. However, the majority

do not. This is not to question their ability or integrity, but it does raise

an important issue: How can the classes remain accredited if people with the

requisite level of qualifications are not teaching them? Remember, the USNA

closed classes (as did many other PME schools) that did not have the required

level of qualified instructor or expertise. CGSC did not.

There is another piece to this: the

quality of education. Most research on education shows that the level of

knowledge of the instructor closely relates to the learning outcomes of the

student. This means classes at CGSC might well have been running but in all

likelihood student outcomes were not the same; they were lower. Again, clearly

this was recognized by the USNA and other PME schools, but seemingly not by

CGSC.

CGSC's response to the furloughs

was to carry on as though nothing actually changed. This indicates that it is

more interested in appearing good than being good. I would welcome a response

that explains how CGSC maintained the quality of ‘seminars' that went from a

ratio of one instructor to 16 students to as many as one to 200-300 without the

requisite expertise that was deemed necessary only a couple of weeks earlier.

The USNA (and other PME schools) made it clear through their actions that they

care more about the actual quality of the education they provide to the

students than does CGSC. I am led to the inevitable conclusion that CGSC is

more interested in checking the box marked "success," rather than actually

achieving it. This bodes ill for General Cone's vision of CGSC as Harvard on

the Missouri.

Dr. Nicholas

Murray is an associate professor in the Department of Military History at the

U.S. Army Command and Staff College. This year he was awarded the Department of the Army

Commander's Award for Civilian Service, and he was named Educator of the Year

for History. He has previously published "Guess what? CGSC is even more broken than we thought! And it is getting

worse" on Best Defense and "Officer Education: What Lessons Does the French Defeat in 1871 Have for

the US Army Today?" in the Small Wars

Journal. The views are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy

or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

October 8, 2013

What did British naval aviation do in World War II after the Taranto raid?

Yes, there was

the Taranto raid, and Royal Navy aircraft crippling

the Bismarck's rudder about seven months later.

But did British naval aviation have any effect on World War II after

1941? I've been struck at how absent it is from the World War II histories. Of

course, there was the Battle of the Atlantic, which was crucial -- but wasn't

the most effective air work done by long-range RAF flights over the Western Approaches?

The war record is

especially striking when you contrast it to the RAF saving the nation from

possible invasion during the summer of 1940.

It is even more

striking that as late as 1944, the Royal Navy's planners were arguing that the

postwar British fleet should be built around the battleship, according to Eliot

Cohen's Supreme

Command, which I was

re-reading this summer.

Today's essay

question: Was the RAF more adaptive than the air wing of the Royal Navy? If so,

why? Extra credit for good historical examples, double points for class

antagonism.

The USMC crackdown on barracks life may in fact exacerbate the trouble

By

"Rick"

NFI

Best Defense department of Marine culture,

because the Marines have culture instead of doctrine

Many

current and former Marines, as well as others, may be aware of the commandant

calling for a crackdown on rowdy behavior in the barracks and his desire to institute new measures in the barracks across

the Corps to "reawaken it morally and crack down on behavioral problems that are

leading to Marines hurting themselves, their fellow Marines, civilians, and

damaging the Corps' reputation."

In addition, the

commandant further cited problems of sexual assault,

hazing, drunken driving, fraternization, as well as the failure to maintain

personal appearance standards among the issues he wants fixed (speaking of

personal appearance, fortunately the current commandant wasn't around in my day

to see my platoon come back aboard ship after trading various parts of uniforms

with the Royal Thai Marines ... yea, I got a belt).

Do I,

as someone that served through similar events (possibly worse) after the early

post Vietnam wind-down, view what the commandant is requiring as too draconian

and an overreaction to Marines settling into garrison after many years on a

high-energy war tempo? I say not necessarily, because without a doubt the

safety of our men and women in uniform is of the utmost importance, as adhering

to high standards of conduct is a Corps tradition and is surprisingly expected

by the public. But rather than dwell on the trivial, such as having personnel

on duty wear an appropriate seasonal dress uniform, which is nothing new but

rather a return to bygone days when this was normal practice, let me address a

primary concern.

Let me

remind all what makes the U.S. military, let alone the Corps, different than

many of the world's militaries: It is our cadre of NCOs/petty officers that we

ideally empower with trust and confidence to carry out duties and missions

normally found performed by officers in foreign militaries. Therefore, when the

commandant states that corporals and sergeants will no longer be promoted as a group,

but individually, giving promotion a personal nature and meaning, that can only

be a good thing and something that was done when I was promoted to those ranks

prior to Vietnam.

However,

if the Corps is going to talk-the-talk about NCOs being the backbone of the

Corps, then it must walk-the-walk and allow its NCOs to supervise what goes on

within the bounds of their authority among the rank and file, holding them

accountable and correcting where necessary, while certainly making available

24/7 both staff non-commissioned and commissioned officers to assist and/or

take over in resolving matters beyond their NCOs' experience level and/or

authority when required, as well as pointing NCOs in the direction to arrive at

the correct solution as opposed to doing it for them.

Unfortunately

in my view, the commandant, by introducing security cameras in the barracks and

having the barracks roamed by seniors beyond the normal staff duty and officer

of the day routinely after hours, can create a climate that the Corps doesn't

trust its corporals and sergeants to maintain authority along with good order

and discipline. Odd, in a manner of thinking, since many have been carrying

loaded weapons around 24/7, supervising other doing the same thing, among other

things. Thus, I would recommend local commanders who know their Marines are the

best informed to make decisions on how much further supervision, along with

"health and comfort" inspections, are necessary within their command/unit.

Although, it might not hurt to have a junior officer available after hours and

on weekends periodically that is approachable for informal chats after hours,

which is something I took upon myself to do once upon a time during the dark

days immediately following our withdrawal from Vietnam.

In

closing, I would caution that some further discussion take place in regard to

what is and isn't necessary involving supervision, and would point out not

using measures tantamount to spying and micromanagement. Because nothing drives

young Marines crazier than boring, unimaginative garrison training and assigning

make-busy tasks than superiors popping in and out of the barracks at all odd

hours, displaying a lack of trust that may lead many living in the barracks to

find homesteads elsewhere after sunset, under less ideal conditions, contributing

to the very problems the commandant is trying to get under control.

"Rick" NFI is

a retired

Marine interested in seeing the spirit of Lt. Gen. John A. LeJeune's belief

that the relationship between senior and subordinate should be one of mutual

trust, within the framework of a father mentoring and guiding a son (or

daughter) without hovering over him (or her).

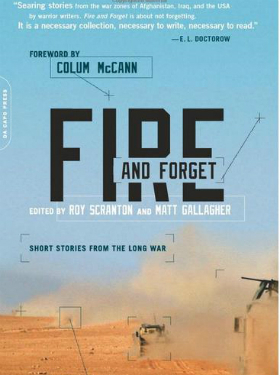

'Fire and Forget': A review

Reviewed

by Brian Castner

Best

Defense book reviewer

A

version of this review first appeared in the August issue of Proceedings

of the U.S. Naval Institute.

If you believe the media coverage and

commentary, all of America is still waiting for the great fiction of the wars

in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many of last year's reviews of The Yellow Birds or Fobbit

or Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk

noted the supposed dearth of war novels to that point. In times past, America

waited 11 years for A Farewell to Arms,

16 for Catch-22, and 15 for The Things They Carried. Now our culture

wants to hear who won American Idol

by the end of the episode, and even Anthony Swofford, who knows something about

delayed gratification (his memoir, Jarhead,

was published 12 years after the first Gulf War), says on the back cover of Fire

and Forget, the new collection of short stories by military veteran

writers, "I've been waiting for this book for a decade."

Is the wait finally over? Yes, according to

Matt Gallagher, one of the collection's editors, who was impatient himself; he

wrote a piece for The Atlantic in

2011 asking when a great novel from the long wars would finally be written.

"Iraq and Afghanistan fiction is in a much

better place than it was when I wrote that article," he told me, before

hedging, "It's just beginning. There's no one dominant story, no one clean

narrative, to emerge from these postmodern, brushfire wars. There are many."

The form of Fire

and Forget follows its function, then: 15 tales with varied perspectives,

and while expected themes of struggle and disillusionment emerge, there is not

a carbon copy to be found here. If you are a fan of literary Paris Review or The New Yorker short stories -- casual tragedy, slow reveals,

ambiguous endings -- you will find familiar hardware in this collection, and

for good reason. These are serious writers, more than half graduates of

master's of fine arts programs, but unlike the traditional college student,

these veterans bring a life experience to the form that is substantial and

heart-breaking.

Perhaps fittingly, considering the

post-traumatic stress disorder newspaper headlines, there are more stories here

about the challenges of return than the horrors of war, more whiskey bottles

flying than bullets. In a number of stories about surreal post-war moments,

animals act as symbolic stand-ins for innocence, and thus are mercilessly shot,

squashed, and buried. For me, the stories of in-country combat were a

comparative relief from the grinding tales of heartache at home. At least we

know how the firefight will end; we have no such certainty about those still

laboring to reintegrate.

The winner for sheer visceral impact is Phil

Klay, whose story of returning is so spot-on I wonder if he wrote it while

still on the plane ride home. He gets everything pitch perfect, and not just

the major points, such as wanting to go back to war right away, literally hours

after landing. No, it was the small truths that returned me to my own

homecoming: the unfamiliar softness of a wife's embrace after months of hard

Humvees, the pleasant satisfaction of the first hangover. Klay remembers the

details so the rest of us don't have to.

David Abrams, the author of Fobbit, tells the brutal story of a unit

remembering fellow soldiers lost in combat, not with nostalgia but rather

obscenity-laced efficiency. "This short story is more typical of what I

normally write," Abrams told me. "It has more dramatic punch than . . . comedy veneer."

Siobhan Fallon's excellent story from the

perspective of an Army wife is a breath of fresh air, one that comes early in

the anthology and that honestly I could have used a little later. The veteran

experience can feel insulated and claustrophobic, and Fallon's incongruence

with the other pieces -- the only one not from the perspective of the solider

or veteran (although Gallagher's contribution is half and half) -- begs the

question, where is a piece about an Afghan family? An Iraqi interpreter? A new

refugee? Instead, the Iraqis and Afghans in Fire

and Forget are always "hajjis" or, in the words of contributor Ted Janis's

protagonist, "[expletive] traitors."

Why is this? "I think veterans are still stuck

in their own head," said Abrams. "And I think we Americans, to paint with a

very broad brush, lead very insular lives. We don't naturally think about

foreign policy. But for the purposes of this anthology, it's fine. Each of

these works of art stand on their own."

True, and they do so well, but even the story

from Andrew Slater, now a teacher of English at the American University in

Erbil in northern Iraq, is about a U.S. soldier struggling with traumatic brain

injury at home. Would he not have been the writer to bridge the gap? His story,

though, is so troubling and thought-provoking that I wouldn't trade it and

that's the point, isn't it? After 12 years of war, we're just starting to

understand what happened to our own soldiers. Perhaps in time we'll reach

across the gulf to those we were fighting -- with and against.

Brian

Castner is a former U.S. Air Force captain and explosive ordnance disposal

officer. He is the author of The

Long Walk: A Story of War and the Life That Follows (Doubleday, 2012). This review is reproduced here with the permission of its author.

October 7, 2013

What the hell is Gen. Clapper thinking, saying that furloughs may encourage intelligence officials to sell secrets?

By "Sto Akron

"

Best Defense bureau of intelligence review

On October 2nd, in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee less than 48

hours after the government shutdown began, Director of National

Intelligence Clapper characterized the furlough of thousands of members of the intelligence community

as a "dreamland for foreign intelligence service to recruit,

particularly as our employees, already many of whom [are] subject to furloughs

driven by sequestration, are going to have, I believe, even greater financial

challenges."

Mr. Clapper, the very idea that after two days or two-hundred

the dedicated men and women of the intelligence community would be more

inclined to become traitors and commit espionage lays bare your lack

of appreciation for the deep sense of patriotism, pride, and commitment to

national security that drives them. Those of us who have served alongside them

know that they would turn to the private sector, or even the local unemployment

office, before ever knocking on the door of the Russian Embassy.

More worrisome, perhaps, is the fact that it highlights your

fundamental misunderstanding of what leads people to commit treason. While

there have been and always will be prospective spies that make it

through the screening process, the vast architecture you

currently oversee is not filled with would-be Edward Snowdens. Anyone who has

worked in the intelligence field will tell you that spotting, assessing,

developing, and recruiting human sources is a rigorous and relentless

process -- even in countries that are in far worse shape than ours.

So, while it is certainly easy to follow your logic -- that

furloughed American workers are easier targets because they suddenly don't have

a regular paycheck or even a job -- it is difficult to imagine

intelligence professionals rushing out to do the unthinkable as the

United States becomes a "dreamland for foreign intelligence

services."

Most Americans are concerned about their own job

security and the precarious state of the economic recovery. What's more,

they understand the importance of the intelligence community and that

sending a good part of it home is bound to have an impact on national security.

But the last thing they need to hear from the director of national intelligence is

a sensational call to get his people back to work lest

they sell off the rest of the family jewels.

Mr. Clapper, in your testimony you also said, "I've

been in the intelligence business for about 50 years. I've never seen

anything like this." Well, as that 50-year period covers most of

the Cold War and the entire span of the ongoing global war on terror, I

think most would agree that there have been dozens of times more harrowing

and uncertain than the past 48 hours. Truth be told, at a time

when the entire country is disgusted with the partisanship that has run the

federal government into the ground, your comments do little to

resolve deepening concerns about the current state of leadership in this

country.

"Sto Akron" is a former case officer of the

CIA's National Clandestine Service.

And what the hell is Gen. Hayden doing, joking about killing Edward Snowden?

Not funny. And poor

judgment to say it in public.

More broadly, the

comment seems to reflect an atmosphere of lawlessness in the U.S. intelligence

community nowadays, that legal is what their lawyers say is legal.

And in recent years,

more intelligence officials have gone to jail for leaking than for torturing.

That's some sick shit.

Story of the day: A bereaved mother sees the memoirs of Pres. Bush in a store...

"Gold Star Father,"

a Marine vet who lost a Marine son in our recent wars, mentioned this in a comment the other day:

I was tootling around a Big Box Store one day with my

wife. I left the book section and moved on. Wife disappeared. I back tracked to

find her at the book section taking all of Bush's memoir copies off the shelf

and dropping them on the floor. I panicked for a second as I figured

every camera in the store probably just targeted us. But, I kinda shrugged,

watched her do it, and we moved on. She told me she did the same when Rummy's

memoir hit the shelves.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers