Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 81

October 29, 2013

How we can make better generals

CNAS (the impressive team of Barno, Bensahel,

Kidder, and Sayler) just put out a terrific

study on how to improve the quality of generals in

the U.S. military.

You should read the whole thing, but here are

some of the key recommendations:

-More education for senior leaders.

-Longer time in assignments.

-Performance reviews for three and four star

officers.

-Two tracks for generals -- either warfighting

or management.

Farewell to Ike Skelton

I was sorry to see the passing of Rep. Ike Skelton, a profoundly decent man who

represented the Old School in Congress.

He was well-read. He cared about

professional military education. And once, when I was writing a profile of him

for the Washington Post, he proudly

showed me, about three blocks north of his house in Lexington, Missouri, the

spot where his Confederate ancestors whipped the Yankees. He also told

me about standing on his front porch as a boy and looking up at the glider

pilots overhead -- training for the invasion of Normandy,

it turned out. Then we drove over to Whiteman AFB, where the stealth bombers live.

October 28, 2013

Tom sends a message to the Pentagon: Time for some serious, sober reflection

Here is an op-ed article by me that ran in yesterday's (Sunday) Washington Post. No one who reads this

blog regularly will be much surprised by it.

After the Vietnam War, the U.S. Army

soberly examined where it had fallen short. That critical appraisal laid the

groundwork for the military's extraordinary rebuilding in the 1970s and 1980s.

Today, after more than a decade of war

in Afghanistan and Iraq, no such intensive reviews are underway, at least to my

knowledge -- and I have been covering the U.S. military for 22 years. The

problem is not that our nation is no longer capable of such introspection.

There has been much soul-searching in the United States about the financial

crisis of 2008 and how to prevent a recurrence. Congress conducted studies and

introduced broad legislation to reform financial regulations.

But no parallel work has been done to

help our military. The one insider work that tried to critique overall military

performance was a respectable

study by the Joint Staff,

but it fell short in several key respects, including silence about the failure

to deploy enough troops to carry out the assigned missions in Iraq and

Afghanistan. As James

Dobbins recently noted in a review of that study, our military shows "a

continued inability to come to closure" on some controversial issues.

This is worrisome for several reasons.

The military continues largely unchanged despite many shaky performances by top

leaders. That is unprofessional. It doesn't encourage adaptive leaders to rise

to the top, as they find and implement changes in response to the failures of

the past decade. And it enables a "stab in the back" narrative to emerge as

generals ignore their missteps and instead blame civilian leaders for the

failures in Iraq and Afghanistan. A retired general I know warns that this

narrative is more likely to take hold as the active-duty military shrinks and

grows more isolated from the society it protects.

There is no question that President

George W. Bush and other civilians made many of the most glaring errors, such

as the decision to go to war in Iraq based on a misreading of intelligence

information. But military leaders also made mistakes, and those remain under

the rug where our generals swept them.

I am not criticizing the performance of

soldiers and Marines in Iraq and Afghanistan. Unlike in the Vietnam War, they

were, at the small-unit level, well-trained and well-led. They were tactically

proficient and generally enjoyed good morale. In Vietnam, Chuck Hagel, now the

secretary of defense, served as an acting first sergeant of an infantry company when he had been in the Army for less

than two years. Nothing like that happened recently.

Our military is adept and adaptive at

the tactical level but not at the higher levels of operations and strategy.

Generals should not be allowed to hide behind soldiers. Indeed, one way to

support the troops is to scrutinize the performances of those who lead them.

The many unanswered questions about how

our military performed in recent years include:

How did the use of contractors, even

in front-line jobs, affect the course of war? Consider that two recent

national-security incidents involved federal contractors: Edward Snowden, who distributed U.S. government secrets around the world, and Aaron Alexis, who killed 12 people at the Washington

Navy Yard last month.

Which units tortured people? This

affected success in the wars but also relates to caring for our veterans.

Torture has two victims: those who suffer it and those who inflict it. Yet our

military leaders are not turning over this rock.

Are there better ways to handle

personnel issues than carrying on peacetime policies? Were the right officers

promoted to be generals? A recent article

in Parameters, the

journal of the Army War College, found that commanding a division in combat in

Iraq slightly hurt a general's chances of being promoted to the senior ranks.

Yet in most wars, combat command has been the road to promotion. What was

different in recent years?

And what happened to accountability

for generals? Recently the Marine Corps fired two generals for combat failures in Afghanistan.

This was newsworthy because it apparently was the first time since 1971 that a

general had been relieved for professional lapses in combat. That is too long.

The military is not Lake Wobegon, and not all our commanders are above average.

Some fundamental disagreements

between U.S. military leaders and their civilian overseers were never

addressed, such as the number of troops required to occupy Iraq. This undercut

the formulation of a coherent strategy. Can we educate our future military

leaders to better articulate their strategic concerns? If not, expect more

quarreling and confusion on issues such as what -- if anything -- to do about

Syria.

As long as such questions go

unanswered, we run the danger of repeating mistakes made in Iraq and

Afghanistan. With President Obama and Congress apparently disinclined to push

the military to fix itself, it is up to the Joint Chiefs, especially Chairman

Martin Dempsey and the heads of the Army (Gen. Raymond Odierno) and the Marine Corps (Gen. James Amos), to do so. It is their duty.

'Time' reviews the state of the U.S. Army, and raises some interesting questions

The Nov. 4 edition of Time magazine has a long look by the estimable Mark Thompson at the

state of the Army. It quotes me and other suspects, but the best comment is

from Arnold Punaro, about the cost of benefits to the Pentagon: "We're going to turn the Department of Defense

into a benefits company that occasionally kills a terrorist."

That remark reminds me of something I read

lately that really struck me about how the pinnacle of the military is Delta

Force, and that basically to be in the military is to defer to the guy with the

beard who shoots OBL in the face. I think that is right -- I don't know if

Special Operations has ever held such a central place in the culture of our

military. What is the difference between an army built for the mass use of

force, and an army that elevates assassination to its primary task? I need to

think about the implications of this.

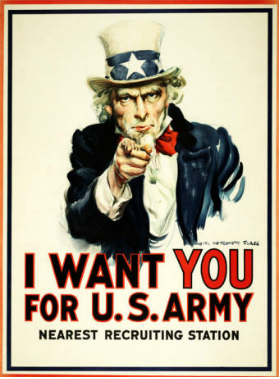

Pritzker's favorite recruiting posters

The Pritzker Library is celebrating its 10th

anniversary by sending along its 10 favorite recruiting posters. Here they are:

Chicago's Pritzker Military Library is a

unique non-profit organization that is committed to maintaining and improving the

public's appreciation of the military -- past, present, and future. In honor of

the Library's 10th anniversary, its special collections staff has

selected 10 of their favorite military recruitment posters from its collection

to share.

In addition to more than 45,000 books on

military history and several thousand artifacts, the library's collection houses

more than 1,500 prints and posters from the late 17th century to the present.

It includes posters from all over the world, in nine languages. The bulk of the

collection consists of propaganda posters from World War I and World War II,

including works from Howard Chandler Christy, James Montgomery Flagg, and

Norman Rockwell. The subject matter of these posters ranges from military

recruiting, fundraising, and conservation to charity, education, and protest.

1. I Want YOU for U.S. Army, James

Montgomery Flagg, 1917

Originally published as a magazine cover in July 1916, this

portrait of "Uncle Sam" is considered to be one of the most popular

and iconic posters in history. As the United States entered World War I and

began sending troops and supplies overseas, more than four million copies were

printed and distributed across the nation.

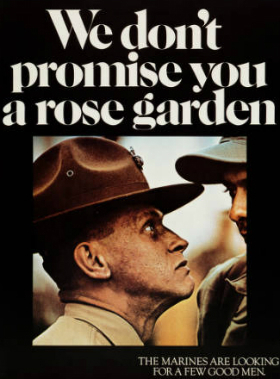

2. We don't promise you a rose

garden, 1971

Featuring a menacing photograph

of former Marine drill instructor Sgt. Charles Taliano, this legendary poster

reminded prospective Marines of the harsh reality of service, and was a staple

of Marine recruiting offices from the early 1970s until the mid-1980s.

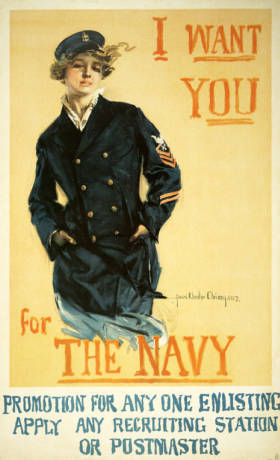

3. I Want You for the Navy, Howard

Chandler Christy, 1917

Christy is remembered best for

his "Christy Girls" -- drawings and paintings of women who possessed certain

characteristics that he believed represented the American Ideal -- and they

were present even in his work for the military. Here, Christy portrays a woman

wearing a navy coat and hat in a promotion for the U.S. Navy.

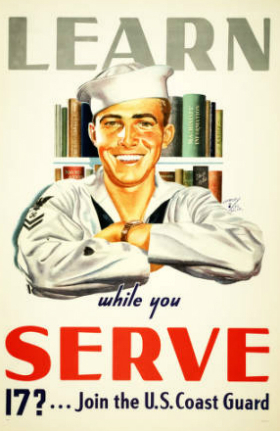

4. Learn While You Serve, John

Joseph Floherty, circa 1939-1945

The U.S. Coast Guard took a shot

at recruiting high school students with this WWII-era poster, which features a smiling

petty officer in front of two shelves of books on various engineering and naval

topics. The subheading, "17?...Join the U.S. Coast Guard," was intended to

capture the attention of young men contemplating higher education.

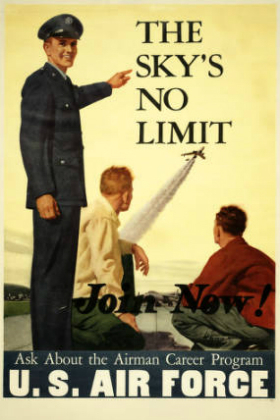

5. The Sky's No Limit, Harry

Anderson, 1950

While many recruitment posters

focus on duty or service, the U.S. Air Force had another angle to pitch: the

miracle of flight. In 1950, Harry Anderson's "The Sky's No Limit" poster

promised excitement and adventure to those who might become Air Force aviators.

6. Treat ‘Em Rough - Join the Tanks, August

William Hutaf, 1917

The United States Tank Corps -- the

mechanized unit that conducted tank warfare during WWI -- produced one of the

most vivid and imaginative recruitment posters in history with this memorable

image of a fearsome black cat above a tank-strewn battlefield.

7. Coast Artillery Corps - U.S.A.,

Philip Lyford, 1926

In the tradition of most

recruitment posters of the early 20th century, the Army's Coast Artillery Corps

stuck to the basics in promoting their cause: "Join us!"

8. Train and Gain -- New Nuclear

Navy, Joseph Binder, 1958

The U.S. "Nuclear Navy" began to

take shape in the 1940s under Admiral (then Captain) Hyman Rickover, and was

officially established in 1954 with the launch of the U.S.S. Nautilus. This

poster features a modernistic design and an emphasis on advancement -- one of

the more appealing aspects of the transition to a futuristic power supply for

the U.S. Navy.

9. Join the WAC now!, 1944

The Women's Army Corps (WAC) was

created as an auxiliary unit in the early 1940s, and about 150,000 women served

within its ranks by the end of WWII. These female enlistees were given

opportunities to contribute to the war effort by supporting the Army's air

forces, ground forces, and service forces by learning one of more than 200

jobs.

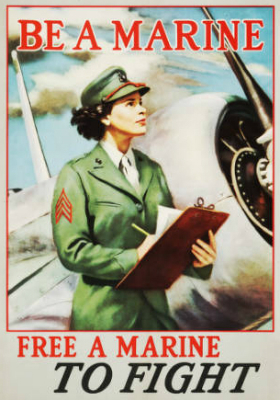

10. Be a Marine: Free a Marine to

Fight, circa 1939-1945

The U.S. Marine Corps joined the

WAC in recruiting and training women to perform certain duties that would

enable more male soldiers to deploy to the front lines. Although these types of

posters may be viewed as degrading by today's standards, they represent an

important step in the continuing quest for gender equality.

October 25, 2013

Help him out: He's invited to speak at his old high school on Veterans Day. What do Best Defense readers think he should say?

That's what a reader writes in to ask.

Here are the details:

--

"I am a post-9/11 Millennial generation Iraq War veteran

who served four years on active duty and two and counting as an active

reservist, all as a company grade/junior officer, and I am presently attending

graduate school on the G.I. Bill. I have been asked to return to my

hometown to speak at my high school to an audience of faculty, staff, ~1,200

students (some of whom have already or will soon enlist or go on to ROTC in

college), a delegation of local National Guard personnel, and veterans from

World War II through Afghanistan. I think it's important to impart

something more than the usual patriotic routine, but I would value the wisdom

of your readers in helping to tailor that message -- and I suspect the discussion

that would follow would be worthwhile on its merits."

--

If I were him, I would talk about the role

the vet plays in protecting the American experiment, the sense that our nation

is always changing, and about other ways to ensure that this noble experiment

does not perish from the earth, such as showing toleration and even

appreciation for those one disagrees with politically. I might end with a warning

against being absolutely certain on any political issue, and ask my listeners

to keep in mind Cromwell's admonition: "I

beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you may be

mistaken."

But that's just me. If you were invited back to your

old high school to speak on Veterans' Day, what would you say? (Besides, "Why

didn't Debbie Do-right go out with me?")

Best Defense commenters: Are you having problems with the FP paywall system?

"Victor LEsperance" commented today: "On a totally

unrelated topic, it sounds like the IT folks at Foreign Policy are moonlighting

at the Obamacare sight. I know they still have their day jobs because I

get paywalled on a regular basis despite coughing up for a

subscription. Now the general public has an idea of what it is like

to be a Foreign Policy subscriber and

sometime blog commenter."

I asked

the powers that be. One responded, "Our website is

undergoing a very extensive redesign, which among other things will bring

improvements to our commenting system, including single sign on. That means the

paywall glitches should come down -- way down - once the new site is up and

running. It shouldn't be long, now."

In the meantime, if

you are having problems, e-mail:

Be polite, OK? We don't want to give Best Defense readers

a bad rep at FP.

Speaking of Obamacare, don't compare it

to the ideal, compare it to what exists now. As part of my move to the New

America Foundation, I've spent a big part of the last six weeks trying to sort

out health insurance for my family. It is nuts. You never get anyone on the

phone the first time. They don't answer e-mails. They get back to you with

additional questions-a week later. They keep pulling out rules they didn't tell

me about when I needed to know them two years ago. And I have been paying a ton

of money for the privilege of receiving this pattern of neglect and abuse.

So, for all its frustrations, I will

take Obamacare. If I were younger, I'd consider setting up a company to guide

people through it.

Rebecca's War Dog of the Week: On the scene of Brazil's protests

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

Postcard from Brazil

Brazil has had its fair share of protests these last few

months -- the teachers'

protest that began in August, and now the protests against oil exploration

contracts. In this photo, taken in June, a protester is arrested by military

police from the special unit Chope, during clashes in the center of Niteroi, 10

kms from Rio de Janeiro. In the background of this chaotic scene, you can see

one of Brazil's military police dogs. Apparently,

Brazil integrated dogs into their armed forces in the 1960s, " authorized

their use within the Military Police organizations of the Army during jungle

operations and commando activities, and the Airborne Infantry Brigade." As

to the job of the dog in this photo, I would assume, based on the dog's breed

(a shepherd) and the situation (a charged protest), that he is there for one

thing -- crowd control.

October 24, 2013

'War Play': A Brilliant & Refreshing Study of the U.S. Military’s Use of Video Games

By Jim Gourley

Best Defense all-star team

Sometimes we can stare at a problem

until we lose perspective of its framework. In the contemporary debates over

drone warfare and domestic surveillance, all our focus is drawn to tangential

arguments such as confirmation of signatures and posse comitatus, distracting

us from essential fundamental considerations. How do the values of our armed

forces inform their relationship to technology? How does our sense of moral

obligation to allies and enemies extend into the virtual

world and the conduct of cyber warfare? Just how reliant is society on

the military for its security, and how reliant is the military on society for

its dominance in innovative capacity? When does the balance of those needs

necessitate the military's influence on the direction of civilian society?

These questions are somewhat esoteric, but they shape the underlying philosophy

that guides our most important decisions.

They

are also the ones that get shoved into the background of more immediate

matters. That is what makes Corey Mead's War Play such a

brilliantly refreshing work. Though its subject, the history of the military's

use of video games, seems innocuous, Mead provides a revealing historical

perspective that calls attention to its importance, benefits and consequences

all at once. Like an actual video game, War Play gives the reader an

opportunity to disconnect from "real world" concerns and enjoy

viewing things in a lighter, more entertaining context. But also like its

subject, War Play is much closer to the real thing than one might

expect, and shows how the same dilemmas apply to both Stuxnet and "America's Army."

At a

svelte 198 pages, this book wastes no time with extraneous commentary. From the

beginning, Mead launches

into the history of the military's and video game industry's influence on each

other. Interestingly, this relationship begins with the military's long-running

involvement in the American education system. He paints a picture of a large

governmental agency that created numerous materials and programs for war that

were repurposed into highly successful civilian applications. That agency in

turn often uses those products as leverage to access potential service members,

both for the purpose of recruitment and educational preparation. According to

Mead, it began when George Washington initiated a literacy program in Valley

Forge using the Bible as its textbook, and continues today as the military

introduces video simulations of firing ranges and missile launchers to schools

to help with physics-- and put military-themed materials in front of kids in

schools that are otherwise hostile to recruiters.

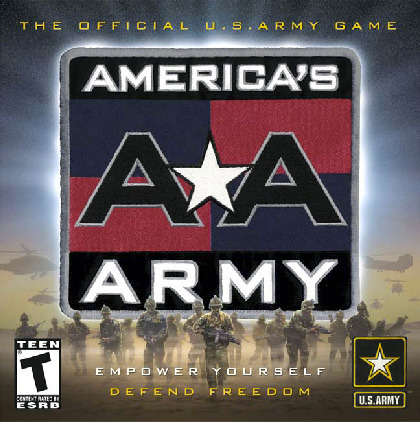

Perhaps

the most revelatory part of the book is the section Mead dedicates exclusively

to the video game "America's Army." From the genesis of its concept, to the

bitter arguments from military programmers that emphasizing Army values would

make the game unappealing to kids and efforts by the Pentagon to defund it, to

its achievement as the greatest recruiting tool in Army history and further

commercial success, Mead uses the story of this single game as a microcosm of

his entire narrative, and by proxy for the military's relationship with

technology as it enters the 21st century.

The

work is not without its flaws. At times Mead leaps to conclusions outside the

concern of his primary theses and without substantiating evidence. He claims

more than once that the modern video game

industry would not be as sophisticated or large as it is were it not for

the enormous amount of patronage it received from the military. It's a bit of a

reach without any consideration of other forces in the game industry, like a

certain Italian plumber from

Japan. Likewise, Mead is given to singing the praises of the modern

gamer-cum-soldier rather than scrutinizing him. He discusses the psychological

advantages a gamer has in the modern dynamic battlefield environment --

multitasking, greater ability to think quickly and filter sensory input-- only

in the context of actual hostilities. He does not question whether a

gamer-warrior is more or less adept at the more common tasks associated with

COIN.

But

these are momentary lapses. In the grand scheme of the work, Mead never forgets

that the important items are those that connect games to every other

defense-related tech endeavor. He drives this message home when he pivots on a

quotation from Orson Scott Card's masterpiece Ender's Game,

acknowledging the dilemma that arises when we make games more like war, war

more like games, and encourage children to play games all at once. Like many

other technological enterprises within the Defense Department, the history of

games' successes and failures is haphazard and demonstrates a lack of a

cohesive strategy aimed at clear objectives, making the future vulnerable and

the military its own worst enemy. This is War Play 's greatest

achievemen t-- an examination of a process unblemished by debates attached to

the product. In that regard, it may be as valuable to the present state of

controversial technologies as it is prescient of future ones.

Tom

says

Jim Gourley

is

a force of nature

.

Did the Bay of Pigs Attack Go Off Track Because It Was Supposed to Kick Off With The Assassination of Fidel Castro?

I've just finished reading Seymour

Hersh's very interesting book The

Dark Side of Camelot. He argues that the Bay of Pigs invasion went wrong in part

because Castro was supposed to be killed by the time it started. When that

didn't happen, the whole shebang

began unraveling.

I wish I had read the book before I

wrote about Maxwell Taylor in my own book The

Generals. Hersh confirms my view that Taylor was a snake, and that the

Kennedys (John and Robert) were taken in by him -- and that is one of the

reasons we wound up in Vietnam, as they all showed each other how tough they

were, and Taylor thought he had found a role for the Army in a nuclear

world.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers