Emily M. Danforth's Blog, page 55

March 31, 2013

soummmyeah:

The Killing of Sister George (1968)

"The novel…at least makes some pretense of imitating the world in all its complexity; we not..."

The novel…at least makes some pretense of imitating the world in all its complexity; we not only look closely at various characters, we hear rumors of distant wars and marriages, we glimpse characters whom, like people on the subway, we will never see again. As a result, too much neatness in a novel kills the novel’s fundamental effect. When all of a novel’s strings are too neatly tied together at the end, as sometimes happens in Dickens and almost always happens in the popular mystery thriller, we feel the novel to be unlifelike. The novel is by definition, to some extent at least, a “loose, baggy monster”—as Henry James said irritably, disparaging the novels of Tolstory. It cannot be too loose, too baggy or monstrous; but a novel built as prettily as a teacup is not of much use.

A novel is like a symphony in that its closing movement echoes and resounds with all that has gone before…It is this quality of the novel, its built-in need to return and repeat, that forms the physical basis of the novel’s chief glory, its resonant close. (It also sets up a risk that the novel may seem contrived.) What rings and resounds at the end of a novel is not just physical, however. What moves us is not just that characters, images, and events get some form of recapitulation or recall: We are moved by the increasing connectedness of things, ultimately a connectedness of values. Coleridge pointed out, stirred to the observation by his interest in Hartleian psychology, that increasingly complex systems of association can give a literary work some of its power. When we encounter two things in close association, Hartley noticed, we tend to recall one when we encounter the other. Thus, if one is standing in a drugstore the first time one reads Shelley, the next time one goes to a drugstore one may think of the poet, and the next time one encounters a poem by Shelley one may get a faint whiff of Dial and bathsalts. The same thing happens when we read fiction. If the first time our hero meets a given character it occurs in a graveyard, the character’s appearance will carry with it some residue of the graveyard setting.

-

John Gardner, The Art of Fiction

Sometimes my students give me a bad time about my affection for so many of the things John Gardner had to say about fiction. They do this, I think, because he can be so stuffy and pompous in his analysis (particularly in tAoF), so old fashioned and uncool. (A writer I met in grad school once told me—in complete seriousness—that he was only interested in fiction that refuted anything John Gardner might have ever said about the writing of fiction.)

And certainly I have my own objections to some of Gardner’s absolutes, sometimes just his tone. (I mean, even in the preface to tAoF he explains that what is said in the book is said for the elite (yes, his word); that is, for serious literary artists. (So, yeah, easy to mock that tenor: I get it.)

However, I am, to lift a term from my students, a fangirl for Gardner. (And I should clarify that I’m less a fangirl for his actual fiction—and I’m rather sorry that’s the case—than I am one for his take on technique, his thoughts on how fiction works, or might work.) So much of what he says in tAoF (such as the section I’ve posted here, about the power of the increasing connectedness of things) speaks to what is personally appealing to me about fiction—what moves me, what makes me invest or contemplate—what makes me, when I’m reading a novel, see the world anew.

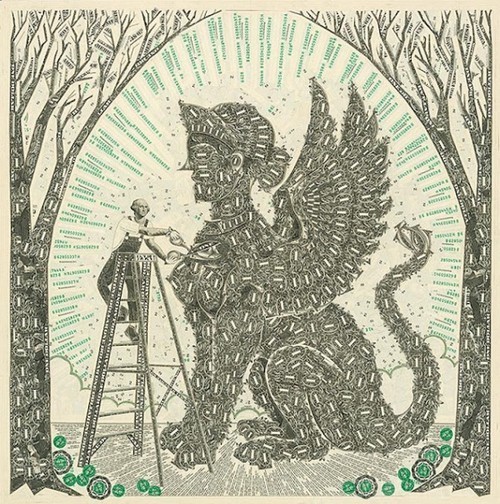

likeafieldmouse:

Maude Leonard-Contant

"Place in fiction is the named, identified, concrete, exact and exacting, and therefore credible,..."

Place in fiction is the named, identified, concrete, exact and exacting, and therefore credible, gathering spot of all that has been felt, is about to be experienced, in the novel’s progress. Location pertains to feeling; feeling profoundly pertains to - place; place in history partakes of feeling, as feeling about history partakes of place. Every story would be another story, and unrecognizable as art, if it took up its characters and plot and happened somewhere else. Imagine Swann’s Way laid in London, or The Magic Mountain in Spain, or Green Mansions in the Black Forest. The very notion of moving a novel brings ruder havoc to the mind and affections than would a century’s alteration in its time. It is only too easy to conceive that a bomb that could destroy all trace of places as we know them, in life and through books, could also destroy all feelings as we know them, so irretrievably and so happily are recognition, memory, history, valor, love, all the instincts of poetry and praise, worship and endeavor, bound up in place. From the dawn of man’s imagination, place has enshrined the spirit; as soon as man stopped wandering and stood still and looked about him, he found a god in that place; and from then on, that was where the god abided and spoke from if ever he spoke.

Feelings are bound up in place, and in art, from time to time, place undoubtedly works upon genius. Can anyone well explain otherwise what makes a given dot on the map come passionately alive, for good and all, in a novel-like one of those novae that suddenly blaze with inexplicable fire in the heavens? What brought a Wuthering Heights out of Yorkshire, or a Sound and the Fury out of Mississippi?

”- Eudora Welty, “Place in Fiction”

"Kilimanjaro belongs to Ernest Hemingway. Oxford, Mississippi, belongs to William Faulkner… a..."

- Joan Didion, The White Album

March 30, 2013

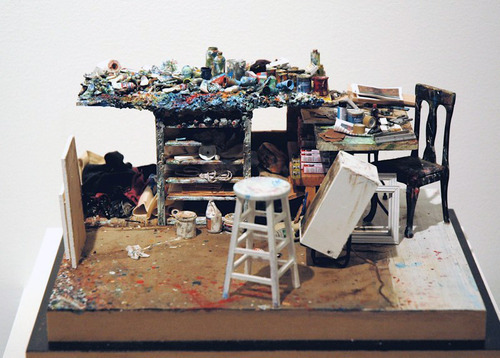

likeafieldmouse:

Joe Fig - Inside the Painter’s Studio...

Joe Fig - Inside the Painter’s Studio (2013)

1. Jackson Pollock

2. Henri Matisse

3. Willem de Kooning

4. Brancusi

5. Studio

6. The Artist at Work

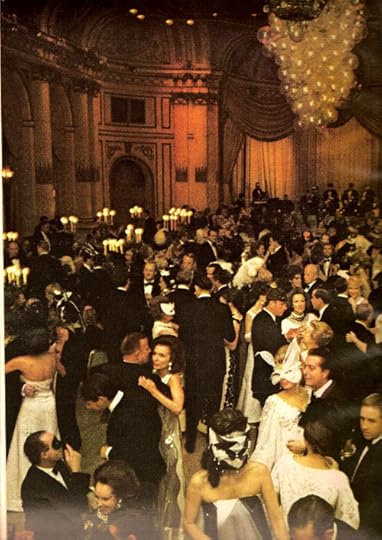

Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball, Vogue 1967

Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball, Vogue 1967

March 29, 2013

likeafieldmouse:

Jessica Eaton

"Occasionally, I have students who want to be rock stars. They have started a band, and they are..."

Occasionally, I have students who want to be rock stars. They have started a band, and they are spending their weekends and off hours writing songs and practicing. Without fail, these kids know everything there is to know about new music. They are listening all the time—they can discourse on Bob Dylan as easily as they can talk about the new e.p. from a new band from Little Rock, Arkansas, or wherever, and they have a whole hard drive full of demos from obscure artists that they have downloaded from the internet.

I wish that my students who want to be fiction writers were similarly engaged. But when I ask them what they’ve read recently, they frequently only manage to cough up the most obvious, high profile examples. What if my rock star students had only heard of… um… The Beatles? We listened to them in my Rock Music Class in high school. And… And Justin Timberlake? And, uh, yeah, there’s that one band, My Chemical Romance, I heard one of their songs once.

How awful would that be?

Young writers, if you want to be rock stars, you have to read.

- Dan Chaon (via mttbll)