Gregory A. Fournier's Blog, page 7

June 2, 2021

Ottawa War Chief Pontiac (Obwandiyag) Attacks Fort Detroit

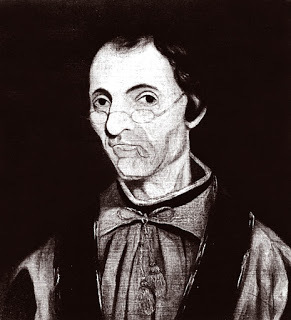

No images of Pontiac are known to exist. This engraving is from 1879.

No images of Pontiac are known to exist. This engraving is from 1879.During the French and Indian War (1754-1763) against the British, most of the Great Lakes Native American tribes allied themselves with the French, whom they regarded as brothers. When the British defeated the French in Quebec, New France (Canada) in 1760, control of Fort Pontchartrain was surrendered to British General Jeffery Amherst. The fort changed from a French trading post to an English military stockade with a strong military presence. The French fleur de lis was replaced with the British Union Jack flag, and the fort was renamed Fort Detroit.

French settlers and trappers developed relationships with their tribal neighbors. They hunted and trapped together, shared food, traded beaver pelts and Indian artifacts for European goods, intermarried, and collected their annual tribute from their Great White Father--French King Louis, the XV. A stipend was paid to the tribes for trapping and hunting rights on Indian land which drew Indians in large numbers to Fort Pontchartrain. There were several peaceful Indian encampments near the fort.

The new British commander General Amherst considered these payments bribery and discontinued them. Unlike the French, Amherst placed restrictions on trading gunpower and ammunition which the Indians needed to hunt so they could feed and clothe their families. To add insult to injury, Amherst made it quite clear to the tribal leaders that they were now British subjects living on British land.

Rather than treat the Indians like equals as the French had done, these Englishmen considered themselves superior by every measure. It was clear to tribal leaders that the British intended to drive the tribes from their ancestral lands and hunting grounds. With English rule, it was only a matter of time before the empire builders and the inevitable flood of aggressive settlers would overrun the land.

The Ottawa, Potawatomi, Huron, Ojibwa, Wyandot, and Chippewa formed a loose confederation to confront their new reality. Ottawa War Chief Pontiac rose to prominence among the Great Lakes tribes for advocating the overthrow of their white overlords. He was the most outspoken tribal leader in favor of driving the British from their land.

On April 27, 1763, Chief Pontiac held an Intertribal War Council ten miles south of Fort Detroit near where the Ecorse River spills into the Detroit River in present day Lincoln Park (Council Park). Over 500 Great Lakes Indians and the heads of nearby French settlements gathered. Chief Pontiac urged the tribes to join the Ottawas in a surprise attack on the fort. The overall strategy was for the tribes to breech the British forts in the Northwest Territory, slaughter the soldiers, and lay waste to the undefended settlements.

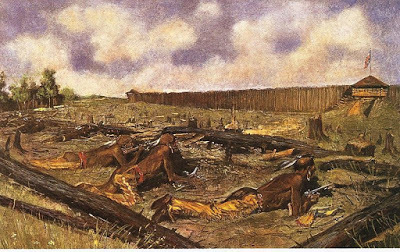

The attack on Fort Detroit by Frederick Remington.

The attack on Fort Detroit by Frederick Remington.The attack on Fort Detroit began under the cover of darkness on May 7, 1763. A war party of about 300 Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibwa warriors approached the fort from the waterfront in 65 canoes and surrounded the stockade, but the garrison commander Major Gladwin was warned of the attack by an informer, so his soldiers laid in wait and repelled the attack. The fort remained under siege for the next 153 days.

When news of Pontiac's attack on Fort Detroit spread, his example was the spark that instigated widespread Indian uprisings throughout the Northwest Territory west of the Allegheny Mountains. On May 25th, Potawatomi warriors overwhelmed soldiers at Fort St. Joseph on Lake Michigan, while on June 2nd, the Chippawa captured Fort Michilimackinac in St. Ignace, Michigan killing most of the inhabitants. Pontiac's early successes won him prominence among the Great Lakes tribes and notoriety among the British.

By mid-June, Fort Detroit's supplies and munitions were running low. Major Gladwin sent an urgent appeal to Fort Pitt for emergency provisions and reinforcements. On July 29th, Captain James Dalyell broke the blockade of the fort by arriving at night with twenty-two barges, 260 Redcoat soldiers, several small cannon, and a fresh supply of provisions, ammunition, and gunpowder from Fort Niagara. As the flotilla made its way slowly upriver to Fort Detroit, warriors from a Wyandot and Potawatomi village opened fire on them killing fifteen Redcoats.

The day after Captain Dalyell's successful relief expedition, the young officer wanted to exact revenge for the attack and killing of his men. Dalyell asked his new commanding officer Major Gladwin for permission to lead a night attack on Pontiac's encampment located two miles from the fort. Against the major's instincts and better judgement, Gladwin approved the mission.

Redcoats in marching formation

Redcoats in marching formationAt 2:00 a.m., a raiding party of 160 Redcoat infantrymen marched toward the Indian encampment two-abreast carrying rifles with fixed bayonets along a road now known as East Jefferson. Two oar-powered flatboats mounted with small cannons followed the soldiers along the shoreline for added firepower.

Pontiac was forewarned of the attack by sympathetic French settlers. His warriors set up several defensive embankments and hid behind the natural cover and wood piles. As the soldiers quietly marched toward them, the barking dogs of French settlers heralded their approach.

The Redcoats halted before the Parent's Creek Bridge at Captain Dalyell's command. Just before dawn, an advance guard of twenty-five soldiers made it halfway across the bridge when the Indians opened fire on them. The British surprise attack was a dismal failure. The gunboat crew fired their booming cannons towards the skirmish with little effect.

Dalyell rallied his troops several times to renew their attack, but each time they were repulsed. Dalyell ordered his troops to retreat towards a nearby French farmhouse for cover. A small party of Indians were inside the house and opened fire on the soldiers killing Dalyell and many others. The survivors fought their way back to the fort after six hours of tactical retreat.

Redcoats break formation

Redcoats break formationThe British lost four officers and nineteen enlisted men with thirty-nine wounded. Four hundred Native Americans fought in the battle losing only seven warriors with twelve wounded. The dead soldiers were thrown into Parent's Creek, thereafter known as Bloody Run because its waters ran red that day. The battle occurred on the site of present day Elmwood Cemetery.

One eyewitness to the battle and its aftermath was teenager Gabriel Casses dit St. Aubin. His most vivid memory was seeing the severed head of Captain Dalyell stuck on a picket fence post. When Major Gladwin learned of the death and decapitation of Captain Dalyell, he offered a two-hundred pound bounty for the head of Chief Pontiac.

By September, Pontiac's loose tribal confederation was beginning to fall apart. The Potawatomi made peace and returned to their villages to help with the harvest and hunt wild game to provide for their families during the harsh winter months. Pontiac sent Major Gladwin a message that he was abandoning his siege and open to peace talks. The larger war continued through 1766.

When Pontiac was unable to persuade the Western tribes to join the rebellion and realized the French would not come to their aid, Chief Pontiac travelled to New York to negotiate an end to the frontier war. Though Pontiac's larger plan was successful--eight of eleven British forts fell--Pontiac and his warriors were not able to defeat Fort Detroit, which led to the chief's loss of stature. Fort Pitt and Fort Niagara also were able to hold out against Indian attacks as well.

British officials were keen to end the war because it was costing the Crown dearly in supplies and manpower. Not understanding the decentralized nature of Indian warfare, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs Sir William Johnson formally ended the war on July 25, 1766, with the signing of the Treaty of Oswego with Chief Pontiac.

When Pontiac agreed to peace talks, he claimed to hold more authority over the Intertribal Council than he actually held. This fueled resentment among the tribal leaders who felt the treaty was a capitulation. On May 10, 1768, Pontiac sent word to British officials that he was no longer recognized as chief by his people. He retired to Illinois to live peacefully with his relatives.

Unbeknownst to Pontiac, a Peoria Indian council in Illinois met secretly and agreed that the former chief was to be executed for an attack several years before on Black Dog, a Peoria chief. A Peoria warrior who was related to Black Dog clubbed Pontiac from behind and stabbed him to death on April 20, 1769, outside the French town of Cahokia, Illinois.

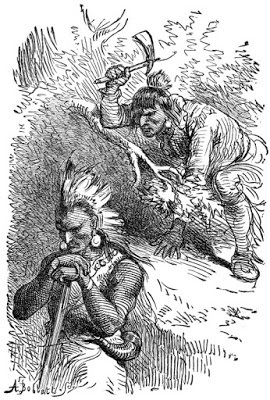

Murder of Pontiac

Murder of PontiacHistorians note that Chief Pontiac was an Ottawa war chief who influenced a wider revolt against the British to drive Great Lakes Indians from their ancestral land. But how did Pontiac's name echo through history?

Famed British officer Captain Robert Rogers claimed to have met Pontiac in 1760 when he and his Rangers took control of Fort Pontchartrain from the French and again when he was a participant in the Battle of Bloody Run in 1763. Capitalizing on his war fame as an Indian fighter, Rogers wrote a play in 1765 named Ponteach (sic): The Savages of America, which became popular in Europe making Chief Pontiac the most famous American Indian of the eighteenth century.

May 7, 2021

Before Berry Gordy There Was Joe Von Battle Producing Records in Detroit

Joe Von Battle in his Hastings Street record shop

Joe Von Battle in his Hastings Street record shopJoe Von Battle was born in 1915 in Macon, Georgia and moved during the Great Migration with his family to Detroit, Michigan. In his teens, he worked doing odd jobs in Detroit’s famous Eastern Market until he found work with Detroit Edison digging trenches and burying electrical lines. During much of World War II, Joe worked double shifts. One shift at the Hudson Motor Car Company and the other shift at the Chrysler Plant across the street. When the war ended, Joe was permanently laid off like many other African American workers, displaced by White veterans returning from the war.

Joe Battle vowed to be his own boss and never work for anyone again. He added Von for a middle name as a young man, emulating European film actor Erich Von Stroheim, who he admired. When he opened his record business, he realized it was helpful on his business cards, obscuring his African American ancestory. In 1945, a narrow grocery storefront was vacated at 3530 Hastings Street in Detroit’s Black Bottom neighborhood on the lower Eastside, Joe Von Battle stepped in and opened Joe’s Record shop.

Joe outside his store

Joe outside his storeIn 1948, Joe Von Battle purchased a reel-to-reel tape recorder and made a makeshift recording studio in the back of his shop. There he recorded artists like John Lee Hooker; Washboard Willie; pianist Detroit Count, who recorded “Hastings Street Opera;” Tamp Red who recorded “Detroit Blues;” Louisiana Red, Memphis Slim, Kenny Burrell, and many other country blues musicians.

Joe Von Battle recorded the final songs and sounds of the people who migrated north for a better life. His shop specialized in records that appealed to African Americans from the rural South who left to work in the automobile or steel industries for a better life. Country blues traveled with them. Joe is believed by music historians to be the first African American record producer in the post war period recording on the JVB, Von, and Battle Records labels.

His record shop played host to Detroit’s itinerate blues musicians. Typically, the music was performed live by a singer with his guitar and maybe a washboard and a harmonica player for accompaniment. Country blues was raw and rooted in the struggle for survival in a world of inherited misery. It sung about poverty, loss, suffering, desertion, death, booze, and loneliness. Country blues had its feet firmly grounded to the earth and rural life.

Joe recorded another style of music with a hopeful spiritual message born out of the same misery—gospel music. Joe was most proud of the over one-hundred sermons he recorded of legendary pastor C.L. (Clarence La Vaughn) Franklin at the original New Bethel Baptist Church on Hastings Street down from his record shop. On Sundays, Joe would broadcast Reverend Franklin’s sermons on speakers set up outside the shop, his storefront always attracted a crowd.

Joe recorded another style of music with a hopeful spiritual message born out of the same misery—gospel music. Joe was most proud of the over one-hundred sermons he recorded of legendary pastor C.L. (Clarence La Vaughn) Franklin at the original New Bethel Baptist Church on Hastings Street down from his record shop. On Sundays, Joe would broadcast Reverend Franklin’s sermons on speakers set up outside the shop, his storefront always attracted a crowd. Probably the most precious recordings he ever recorded were eight hymns sung by Reverend Franklin’s fourteen-year-old daughter Aretha before she signed with Columbia Records in 1960 secularizing her music. When Aretha Franklin signed with Atlantic Records in 1966, she was paired with producer Jerry Wexler who helped her become the Queen of Soul.

Aretha Franklin performing

Aretha Franklin performingIn 1956, the Federal government announced the construction of the National Interstate Highway System spelling doom for Hastings Street, the heart of Detroit’s African American business community and further down Hasting’s Street Paradise Valley, Detroit’s legendary blues and jazz entertainment district. The construction of I-375 was a useless 1.062-mile spur that ran parallel to I-75. When the Black business community was uprooted, the financial health of many successful African American entrepreneurs was cut short.

The transition prompted a Black diaspora to the 12thStreet area on Detroit’s Westside creating overcrowding and increased racial tension in the city. The Black community was boxed in by real estate covenants and red lining restricting their free movement around the city and the greater Detroit area.

Joe Von Battle moved his record shop to 12thStreet in 1960, but by that time there was a new sound dominating the radio and television airways of Detroit threatening his business. “There is a different generation now,” Joe told the Detroit Free Press. “All they want to buy is that Motown stuff with that beat, and they want to dance. Today, young disc jockeys won’t play the blues. They say it’s degrading,”

Berry Gordy brought a polished professionalism and aggressive promotion to his Gordy/Tamla/Motown record labels. The new urban sound was sleek, suave, and sophisticated appealing to a broader, younger, crossover audience. The content of the music changed from the tough realism of the country blues to lyrical, hard-driving rhythms and strong choral arrangements with a strong pop music flavor.

The modern male and female groups wore fancy, matching outfits and danced synchronized choreography to the music. The Motown sound was tailormade for television and radio, taking the new music from Detroit’s Westside to the rest of the country and the globe.

Not only did the music change, the record industry changed also. In the 1960s when the chain department stores established record departments, they began selling rhythm and blues singles and albums. Rhythm and blues entered the mainstream. Independent, specialty record shops could not compete.

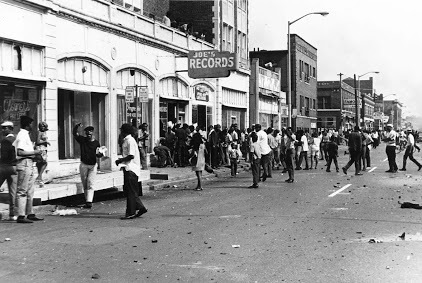

Then on July 23, 1967, as if to add insult to injury, 12thStreet erupted with racial strife and conflagration. The first night Joe protected his store with a weapon but the second day he was ordered by police to evacuate the premises and allow the authorities to restore order. That took a week.

In the meantime, Joe’s business was looted, torched, and hosed down by the fire department. When Joe and his family were allowed to return to the record shop, the smell of charred wood and melted vinyl hung heavy in the air. Twenty years of tape-recorded blues history, Joe’s life work, went up in smoke or down the drain.

Looters oustside of Joe's shop in July 1967

Looters oustside of Joe's shop in July 1967

Joe’s daughter Marsha laments that “Some of the most significant voices in recorded history were on those melted and fire-soaked reel-to-reel tapes. Thousands of songs, sounds, and voices of the era—most never pressed into vinyl—were gone forever. I believe Daddy died that day. My father’s alcoholism gravely worsened after his life’s work and provision for his family was destroyed by looters and rioters.” Joe also suffered for years with Addison’s disease and died a broken man in 1973 at the young age of fifty-seven.

***

Marsha Battle Philpot—aka Marsha Music—wrote a biography about her father to document his music legacy. Marsha brought Joe Von Battle's story back to life in 2008 in her Marsha Music: The Detroitist blog. She writes about Detroit's African American history on her blog.

Marsha Battle Philpot also has published a beautifully written book of poetry and prose titled The Detroitist: An Anthology About Detroit dealing with the era of Detroit's white flight in the 1950s and 1960s and its impact on those left behind.

April 25, 2021

The Beginnings of the Old Sauk Trail and the Building of Michigan Avenue (U.S.-12)

In 1820, Michigan Territory geologist, geographer, and ethnographer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft returned to Detroit from an expedition mapping Michigan following the Great Lakes from the headwaters of Lake Erie north and around the Great Lakes to the southern shore of Lake Michigan. Schoolcraft and his expedition returned following what early frontier game hunters called the Sauk Indian Trail across what would become the state of Michigan in 1837.

In his journal notes, Schoolcraft described the trail as a "plain horse path, considerably used by traders, hunters, and settlers." He noted that many minor trails and early dirt roads crossed the Sauk Trail making it difficult to follow in many areas without a guide.

University of Michigan paleontologists discovered that the Sauk Trail was originally formed by the migratory habits of mastodons (woolly mammoths) and ancient bison herds towards the end of the last Ice Age--the Pleistocene era--between 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago. With woolly outer fur and a dense undercoat, mastodons were well-adapted to the Ice Age climate.

Murial by Charles R. Knight--1919

Murial by Charles R. Knight--1919Mastodon skeletons have been found along the southern corridor of the state of Michigan which U of M paleontologists named the Mastodon Trailway because of the great number of remains discovered. The woolly mammoth's Ice Age global range stretched across the northern tier of Eurasia and North America known as the Mammoth Steppe.

As temperatures rose and the glaciers began receding, the mastodons shifted their migration northward again. They co-existed with Stone Age humans who depended on them for food, clothing, and shelter until diminishing surviving herds were hunted to extinction at the end of the Ice Age. Their remains include skeletons, teeth, tusks, and stomach contents.

The prehistoric trailway continued as a migratory path for herd animals for many thousands of years--most notably elk and deer. Paleo Americans, the ancestors of Native American Indian tribes, used the pathway as a game trail and passageway to the Mississippi River and the heartland of the continent.

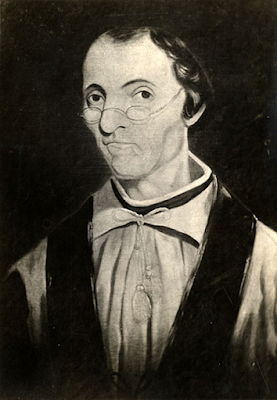

Father Gabriel Richard (Ri-CHARD)

Father Gabriel Richard (Ri-CHARD)In 1823, a civic-minded Jesuit priest from Detroit, Father Gabriel Richard was elected as a non-voting delegate from the Michigan Territory to the House of Representatives for the18th United States Congress. He secured Michigan's first federal appropriation for road construction connecting Detroit with Chicago. The proposed road was surveyed in 1825 by Orange Risdon, who essentially followed the Sauk Trail across the state. Construction began in 1827 and the 210 mile road was finished in 1833 costing a grand total of $87,000.

Orange Risdon--Founder of Saline, Michigan

Orange Risdon--Founder of Saline, MichiganThat year, the first scheduled stagecoach service was established from Detroit to Chicago. Settlers and businessmen from back East took the Erie Canal to Albany or Buffalo, New York, booked passage on a schooner to Detroit, and hired a stage to Chicago once they got to Detroit. The cities of Detroit and Chicago both experienced unprecentented growth in the mid-1830s.

What is presently known as Michigan Avenue has been called many names over the years. First, history records it as the Sauk Trail. It was little more than a footpath until the government improved it and renamed it Military Road. Father Richard pitched the project to Congress for security of the new frontier. Troops and supplies could move east or west on the new territorial road to defend and assist settlers. For a time, the road was known as the Chicago Turnpike, and then its name was shortened to Chicago Road.

The two-lane, highway from Detroit to Chicago has been known as Michigan Avenue since the late nineteenth century. The highway was numbered U.S.-112 when the roadway was paved for automobile traffic in the early twentieth-century. With construction of the Interstate Highway System during the Eisenhower administration in the late 1950s, parts of U.S.-112 were replaced by federal highway I-94. The fragmented highway was rerouted in some areas including the link between Ypsilanti and Saline. The highway was renumbered as U.S.-12 to simplify state maps and minimize confusion for motorists.

The story of Michigan Avenue may not be over. In 2020, a project was proposed in Detroit to update a forty mile stretch from Detroit to Ann Arbor, Michigan into the most advanced, high-tech roadway in the world dedicated to autonomous vehicles for the smooth and efficient flow of mass transit and high-tech automobile traffic.

Dedicated lane for automated traffic--artist rendering.

Dedicated lane for automated traffic--artist rendering.The project, supported by the Ford Motor Company, the Detroit Chamber of Commerce, and forward-looking Michigan politicians, would be a model for a possible multi-billion dollar business partnership between the public and private sectors, making southeast Michigan a hot spot for municipal transportation systems and the cornerstone of the state's economic recovery. An infrastructure development company is building a one-mile pilot road at the American Center for Mobility in Ypsilanti for further research and development.

April 20, 2021

Walter P. Reuther Assassination Attempt Foiled

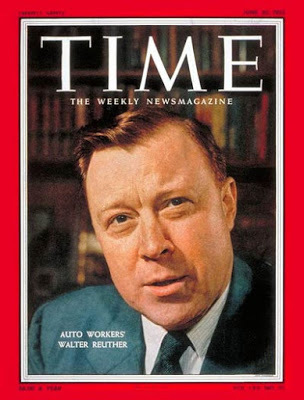

Walter P. Reuther, recently re-elected to a second term as United Automobile Workers (UAW) president, lived with his wife May and their two small daughters in a modest ranch house on Appoline Street in Detroit, just south of Eight Mile Road.

In his 2013 book Built in Detroit: A Story of the UAW, a Company, and a Gangster, Bob Morris recounts the evening of April 20, 1948. After coming home late from a UAW meeting, Reuther prepared to eat his warmed-over dinner. He was opening the refrigerator door to get some peaches when he turned to answer a question from his wife and survived a 12 gauge shotgun blast through the kitchen window.

Four lead pellets lodged in his right arm, one in his chest, and the rest hit the kitchen cabinets. Reuther was taken to New Grace Hospital where doctors told him he might lose his arm. The labor leader was determined to save it. By working tirelessly at painful physical therapy, he was able to regain limited use of his arm. For the rest of his life, neither Reuther nor his family were without UAW bodyguards and traveled everywhere in an armored Packard.

The attempt on Reuther's life was not an isolated incident of industrial violence. Thirteen months later, Walter's brother Victor, met a similar fate. Bob Morris writes, "Late on the evening of May 24, Victor was reading in his living room when a shot gun blast blew threw his front living room window. The shotgun pellets ripped through the right side of his face and upper body tearing out his right eye."

Victor and Walter Reuther shaking hands left-handed with brother Roy between them.

Victor and Walter Reuther shaking hands left-handed with brother Roy between them.At first the Detroit police dismissed the botched murder attempt of Walter Reuther as a power struggle among union Communists. The Red Scare was a popular and convenient scapegoat for corporate America and made good copy for the post-war press. A Detroit detective said, "Gamblers and crime syndicates have nothing to do with this. It's Communists."

But investigators began hearing underworld connections might be involved. Within five days of Reuther being shot, Detroit police--acting on a telephone tip--brought former vice-president of Ford UAW Local 400, Carl E. Bolton, in for questioning. He was charged with intent to commit murder.

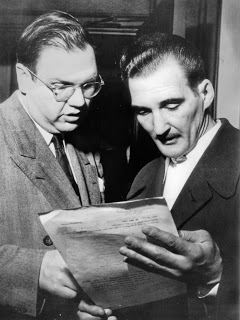

Joseph W. Louisell and Carl. E. BoltonJoseph W. Louisell, Detroit attorney known for defending suspected mob figures, argued Bolton had an alibi and was not at the scene of the crime. After three days in jail, Bolton was released and prosecutors dropped the charges. Bolton was free but still under suspicion.

Joseph W. Louisell and Carl. E. BoltonJoseph W. Louisell, Detroit attorney known for defending suspected mob figures, argued Bolton had an alibi and was not at the scene of the crime. After three days in jail, Bolton was released and prosecutors dropped the charges. Bolton was free but still under suspicion.During the Senator Kefauver Organized Crime Committee hearings (1951-1952), testimony suggested Walter Reuther ran afoul of the Detroit underworld.

Before the shooting, Reuther was aware a Sicilian gang, led by Santo Perrone, was acting as a strike-breaking agency for Detroit companies--big and small. Author Nelson Lichtenstein writes in The Most Dangerous Man In Detroit: Walter Reuther and the Fate of American Labor, "Reuther's assailants were paid by Santo 'the Shark' Perrone, an illiterate but powerful Sicilian gangster." The mid-century labor movement was the age of "the cash payoff, the sweetheart contract, and the gangland beating. It was part of the industrial relations system."

The Organized Crime Committee felt the Detroit police made no serious attempt to solve the crime or curb the anti-union violence. "The Detroit police saw industrial violence as little more significant than a bar brawl," Lichtenstein wrote.

Six years later, Wayne County Prosecutor O'Brien announced at a Detroit press conference that he had solved the Reuther shooting. Arrest warrants were issued for Santo Perrone, Carl B. Renda, Peter M. Lombardo, and Clarence Jacobs.

Donald Ritchie, an ex-con with connections with the Perrones, made a secret arrangement with UAW officials. Ritchie agreed to rat out the people involved with the Reuther shooting for a $25,000 payoff placed in escrow.

If he cooperated with authorities, he would get $5,000 after making the initial statement to the prosecutor and the arrest warrants were issued, an additional $10,000 payable when those named in the warrants were bound over for trial, and another $10,000 when convicted. If murdered before he could cash-in, Ritchie wanted the reward given to his common-law wife.

Part of Ritchie's statement to Prosecutor O'Brien reads, "The night of the shooting, I was picked up at a gas station. The car was a red Mercury.... I sat in the back seat. Clarence Jacobs drove and Peter Lombardo sat in the front seat with Jacobs. The shotgun was in the front seat between (them)--a Winchester 12 gauge pump. I was there in case there was any trouble. If anything happened, I was to drive the car away.

"Jacobs did the shooting. He was the only one who got out of the car.... I heard the report from the gun. Then Jacob got back in the car and said, 'Well, I knocked the bastard down.' After the job, they dropped me off at Helen's bar.... I had some drinks and went to see Carl Renda. He got a bundle of cash and handed it to me. I took a taxi to Windsor and counted my money after I got to Canada. Exactly five grand."

As prearranged, when Ritchie came back across the international border, he was immediately placed under the protection of the Detroit Police Department. While waiting for the trial so he could give his star-witness testimony, he told the Detroit police detail assigned to protect him that he wanted to take a shower. Ritchie escaped from a bathroom window at the Statler Hilton Hotel on Grand Circus Park. Ritchie was on the lam. Once again, he took a cab to safety across the United States/Canada border.

At the same time, Ritchie's common law wife was given the first installment of the escrow account. Ritchie delivered on the first part of the bargain. He made an initial statement and the suspects were charged. The UAW had no choice but pay off the first escrow installment. Ritchie dropped a dime from Canada and denied his entire confession to a Detroit Free Press reporter. He said he needed the money and was taking the UAW for a ride.

Without Ritchie's testimony, Prosecutor O'Brien's case collapsed leaving him with an embarrassing fiasco. He dropped all the charges. The UAW made the stupid mistake of paying a witness. The labor organization had been swindled out of $5,000 by an ex-con.

***

Seconds before the confrontation.The assassination attempt was not the first time Walter Reuther ran afoul of the car companies. On May 26, 1937, Reuther and several other labor organizers were badly beaten by Ford Motor Company Security men in what history notes as the Battle of the Overpass. This was Ford's security chief Harry Bennett's opening salvo against labor organization inside the Ford empire.

Seconds before the confrontation.The assassination attempt was not the first time Walter Reuther ran afoul of the car companies. On May 26, 1937, Reuther and several other labor organizers were badly beaten by Ford Motor Company Security men in what history notes as the Battle of the Overpass. This was Ford's security chief Harry Bennett's opening salvo against labor organization inside the Ford empire. Bob Morris writes, "This was a public relations disaster for Ford, as a Detroit News photographer captured the beating of the labor leaders. The photos... were published around the world. The attack on Walter Reuther made him one of the most recognized labor leaders in Detroit and the country."

Walter Reuther and Richard Frankensteen

Walter Reuther and Richard Frankensteen Arnold Freeman of the Detroit Times reported that Bennett assembled semi-permanent gangs of thugs known as outside squads. A member of one of those squads "Fats Perry" turned state's evidence in 1939. He testified,

"These squads were armed with pistols, whips, blackjacks, lengths of rubber hose called persuaders, and a variety of weapons, some of which made up by a department in the (Rouge) plant itself."

***

On May11, 1970, The New York Times reported Walter Reuther, his wife May, and four other people died in the crash of a two-engined Lear Jet on May 9th at 9:33 PM. The chartered jet--on its final approach to the Pellston Regional Airport, arriving from Detroit in the fog and rain--broke through the clouds short of the runway and clipped some tree tops sheering off both wings. The plane crashed and burst into a fireball a mile southwest of the airport.

The Federal Aviation Administration listed a faulty altimeter as the official cause. No charges were ever filed, but the persistent belief is the crash was not an accident. Reuther was sixty-two.

Silent clip of police investigating Walter Reuther's home after the assassination attempt. His wife speaks briefly to the press. Fingerprints are taken outside the Reuther home.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZMayuqfDpuI

April 12, 2021

Ford Tri-Motor Pioneers Commercial Flight

Restored Ford Tri-Motor

Restored Ford Tri-MotorIn today's jetsetter world, commercial air travel is taken for granted by most people, but in the 1920s the aeronautics industry had to prove itself safe before Americans felt confident enough to board an airplane and leave terra firma. It was not until Henry Ford bought the Stout Metal Airplane Company in 1924 from designer and engineer William Bushnell that public confidence in air travel rose because of Ford's strong reputation for reliability in the automobile business.

Bushnell designed a three-engined transport plane based on an all-metal Dutch plane developed by the Fokker Aircraft Corporation. Ford kept Bushnell on as the president of Ford Motor Company's (FoMoCo) new aircraft division. Production began on the Ford Tri-Motor in 1925. At a press conference, Henry Ford proclaimed "The first thing that must be done with aerial navigation is to make it fool-proof.... What Ford Motor Company means to do is prove whether commercial air travel can be done safely and profitably."

The plane was introduced for limited excursion service as the Ford Tri-Motor in 1926. Soon, the plane became popularly known as the Tin Goose or the Flying Washboard. One-hundred and ninety-nine were produced.

Ford Airport with Henry Ford Museum in the background.

Ford Airport with Henry Ford Museum in the background.The airplane's body was clad in corrugated aluminum alloy for lightweight strength, which regrettably resulted in air drag reducing the plane's overall performance. The original Tri-Motor was powered by three 200 hp Wright engines but was upgraded to 235 hp Wright engines, and upgraded again with 300 hp radial engines. The propellers were two-bladed with a fixed pitch. The maximum air speed of 132 mph was increased to 150 mph depending on the equipped engine. The plane had a low stall speed of 57 mph. The Tri-Motor could safely reach a height of 16,500 feet with a range of 500 miles.

The Ford Tri-Motor was a combination of old and new technologies. As was common in early wooden and canvas airplanes, the engine gauges were mounted onto the engine struts outside the cockpit, and the rudder and wing flaps were controlled by steel cables mounted on the exterior of the airplane. The plane soon developed a reputation for ruggedness and versitility. It could be fitted with skis or pontoons for snow and water takeoffs and landings. The seats could be removed to carry freight.

External cables controlling wing flaps and tail rudder.

External cables controlling wing flaps and tail rudder.The Ford Tri-Motor pioneered two-way, air-to-ground radio communication with their planes while in flight. Once the Department of Commerce Aeronautics Branch developed the Beacon Navigation System, a continuous radar signal was broadcast from fixed beacon locations across the country. Navigators were able to determine a plane's relative bearings by radio impulse without visual sightings, helping pilots guide their planes to their next destination.

Ford Tri-Motors were equipped with avionics that helped establish air corridors and domestic routes coast-to-coast making reliable commercial flight possible. Pan American Airlines scheduled the first international flights with service from Key West to Havana, Cuba in 1927 using Tri-Motors.

Transcontinental Air Transport pioneered the first coast-to-coast service from New York to California. Initially, passengers would fly during the day and take sleeper trains at night. The first commercial planes carried a crew of three (pilot, co-pilot/navigator, and a stewardess) serving eight or nine passengers. By August 1929, the planes had a passenger capacity of twelve which reduced leg room but increased profitability.

Admiral Richard E. Byrd and supply crew-1929.

Admiral Richard E. Byrd and supply crew-1929.To promote air travel and the reliability of air service, Henry Ford's son Edsel financed Admiral Richard E. Byrd's flight over the South Pole to the tune of $100,000. On November 29, 1929, Byrd became the first person to fly over both poles, creating more than $100,000 worth of domestic and international publicity for the Ford Tri-Motor. Byrd left the plane in Antarctica but upon Edsel Ford's request, he retrieved the plane in 1935 and had it shipped to Dearborn, Michigan for display in the Henry Ford Museum where it hangs today.

The Ford Tri-Motor became the workhorse for United States and international airlines. Known as the first luxury airliner, it redefined world travel marking the beginning of global, commercial flight: American Airlines, Grand Canyon Airlines, Pan American, Transcontinental Airlines, Trans World Airlines, United Airlines, and others flew Tri-Motors. A round trip excursion ticket from Ford Airport in Dearborn to the Kentucky Derby in 1929 cost $122 with one stop for fuel in Cincinnati.

Typical excursion advertisement to promote air travel.

Typical excursion advertisement to promote air travel.The aircraft industry underwent rapid development in the 1930s when a new generation of vastly superior planes like Boeing's 247 and the Douglas DC-2 began to dominate the commercial aviation market. The Tri-Motor had declining sales during the Great Depression and was losing money, so FoMoCo closed its airplane division on June 7, 1933. The company chose to concentrate on its core business--automobiles. On a human level, the death of Henry Ford's personal pilot Harry J. Brooks during a test flight made Ford lose interest in aviation.

Originally designed as a civil airplane, the Ford Tri-Motor saw military service in World War II in the United States Army Air Force. It is believed only eight of these classic planes are airworthy today. In popular culture, it was a Ford Tri-Motor that appeared in the film Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom leap-frogging across the map.

March 27, 2021

Detroit's Father Gabriel Richard

Father Gabriel Richard

Father Gabriel RichardOne of the most influential people in Detroit's 320 year history is Father Gabriel Richard (Ri-CHARD), who was born in La Ville de Saintes, France on October 15, 1767. At the age of seventeen, young Richard entered a Jesuit seminary and was ordained a priest on October 15, 1790.

After the French Revolution, Richard and many of his fellow priests refused to swear allegiance to the new secular French Republic. He escaped the guillotine when the captain of the ship Reine des Coeurs (Queen of Hearts) made it quietly known that he was about to sail for the United States and had room onboard to smuggle a few priests out of the country. When the Reine des Coeurs sailed on April 2, 1792 Gabriel Richard was aboard. Four months later, anti-Catholic mobs in Paris murdered 200 defiant priests.

Father Richard reported to Bishop Carroll of Baltimore and began his new life in America as a mathmatics teacher at St. Mary's Seminary. In 1798, the bishop assigned Father Richard to do missionary work with the local Native American tribes and to administer the sacraments to the Catholic population in the Northwest Territory. He arrived in Fort Detroit as a priest for the Society of Saint-Sulpice.

A defining moment in the history of Detroit and the life of Father Richard was the Great Fire of June 11, 1805. A burning ember from a baker's pipe fell into a pile of hay. Within minutes, the fire spread out of control burning everything within Fort Detroit but the stone chimneys. The blaze took most of the cattle and the town's food supplies did not survive the blaze. Father Richard took control and organized men into expeditions that went up and down the Detroit River asking farmers on both sides for emergency provisions to avert famine. From then onward, Detroit residents refered to Richard as "Le Bon Pere" (the Good Father).

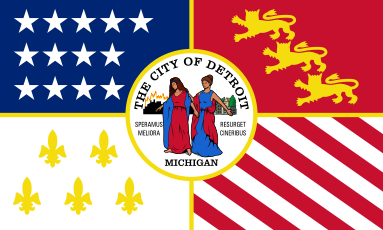

To comfort his parishioners, Father Richard served an open air mass that included this phrase in his sermon, "Speramus Meliora Resurget Cineribus." (We hope for better things. It will rise again from the ashes.) These words became the official motto for the City of Detroit and appear on the city's flag. This motto would have renewed significance 162 years later when much of Detroit burned once again.

Along with Chief Justice of the Michigan Territory Judge Augustus B. Woodward, Father Richard founded the Catholepistemiad of Michigania on August 26, 1817--twenty years before Michigan became a state. The school's name was neither good Latin nor Greek, just hard to pronounce. On April 30, 1821, the school was renamed the University of Michigan.

In 1835, the new Michigan Constitution adopted the Prussian model of education which was a system of primary schools, secondary schools, and a university. A Board of Regents of twelve members was nominated to govern the university. The system was administered by the state and funded with tax dollars. The University of Michigan moved from Detroit to Ann Arbor on forty acres of Henry Rumsey's farmland bought by the Board of Regents. The first class began in 1841 and the first commencement ceremony was in 1845.

Father Richard was elected as a non-voting delegate from the Michigan Territory to the United States House of Representatives for the 18th Congress. In March 1824, he petitioned for and secured federal funding for the Chicago Road to connect Chicago with Detroit, which was later renamed Michigan Avenue. The highway ran the full length of Lower Michigan, opening it up to the West for the development of the southern part of the state.

In 1832 with a servant's heart, Father Richard cared for cholera victims for four days before succumbing himself on September 13th. His body is buried in a crypt beneath the altar of Ste. Anne's side chapel. A bronze bust designates that his tomb lies within. At least five schools in Michigan bear his name, but most Detroiters today have no idea what a giant this five-foot, two-inch man was.

March 6, 2021

1930 Lincoln Phaeton Hamtramck Garage Find

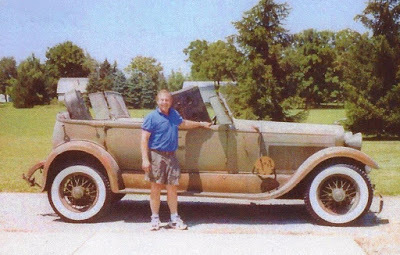

1930 Lincoln Dual-Cowl Sport Phaeton Limo and its proud owner.

1930 Lincoln Dual-Cowl Sport Phaeton Limo and its proud owner.A photograph in my crime history The Elusive Purple Gang: Detroit's Kosher Nostra of a 1932 Detroit Police Lincoln Phaeton squad car caught the eye of one of my readers. Bill (last name withheld) emailed me with an interesting story about a 2005 garage find of a 1930 Lincoln Phaeton Dual-Cowl limousine with 70,000 miles on it which he found in Hamtramck, Michigan. The limo was covered with a canvas tarp and buried under an avalanche of trash for over fifty years.

The car's owner Bruno Rusniak bought the car when he was twenty years old in 1940. When Bruno died in 2004, his sister Lucille liquidated her brother's estate and sold the long-neglected car to Bill. The provenance of the car is interesting, but no less fascinating is the background of the Lincoln Motor Company and their Deluxe Dual-Cowl Sport Phaeton model.

***

Cadillac Motor Car founder Henry Leland left General Motors (GM) in 1917 to build Liberty V-12 aircraft engines with government funding for the World War I war effort. With the help of Ford, Packard, Buick, and other auto manufacturers, 20,748 Liberty engines were mass produced. After the war, surplus Liberty engines were adapted for hydroplane racing and luxury runabouts. Some used by smugglers during Prohibition.

At war's end, Leland with the help of his son reorganized his company and named it Lincoln Motor Car Company. On September 16, 1920, his first Lincoln L-Series, four-door, three-speed manual transmission car was built in his Dearborn, Michigan factory. The start-up company struggled in the competitive marketplace and had trouble fulfilling orders. Leland's stock holders were unhappy and his company went into receivership in 1922.

Edsel Ford

Edsel FordOnly one offer was made to purchase Lincoln Motors. Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo) bought Lincoln for the bargain price of $8,000,000. Henry Ford's only son Edsel was made president of the company. By 1923, Edsel and his general manager Ernest C. Kanzler were able to trim manufacturing costs by $1,000 per car, and the company began posting a profit for the first time.

Edsel was a forward-looking Ford with a flair for automotive design and modern management. When the Lincoln nameplate began earning money, Ford's Lincoln Motor Car Division introduced a two-passenger roadster, a seven-passenger touring sedan, and a five-passenger limousine. Lincoln Motors (FoMoCo) competed against Cadillac (GM), Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg, Packard LeBaron, Pierce-Arrow, and Rolls-Royce in the stand-alone, luxury car market.

Lincoln Greyhound Hood OrnamentIn 1924, the Lincoln L-Series became popular with police departments across the country in a model called the Police Flyer. They were equipped with Ford V-8 engines, brakes on all four wheels, 7/8" bulletproof windshields, and mounted spotlights on the left and right sides of the car near the windshield operated from handles inside the car. Police sirens and gun racks were also fitted to the Police Flyers making them much sought after, state-of-the-art patrol cars.

Another great stroke for the Lincoln L-Series was when a Lincoln became the first state limo in 1924--used by President Calvin Coolidge. The Lincoln Phaeton Dual-Cowl (front and rear seat windshields) limousine is the car that polio-stricken President Franklin D. Roosevelt used on the campaign trail so he could appear before crowds without leaving the vehicle. The car became known as the Sunshine Special because of its retractable convertible top. President Truman used the same car until it was retired in 1948.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano RooseveltToday, the Sunshine Special is on display at the Henry Ford Museum with other famous presidential cars. Lincolns were the official state limos until 1993 when Cadillac became the presidential state car.

***

After Bill removed the clutter around and on top of his garage find, he rolled the car out onto the driveway and into the sunlight to get a better look. The Phaeton's original colors were blue with black fenders, but at some point the car underwent a hasty do-it-yourself paint job. Bill also discovered that the car had a smashed fender, other rear end damage, and several bullet holes in the aluminum body work. After rummaging through the limo's interior, he found a canvas bag from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago in the back seat.

Extensive rear end damage on aluminum body.

Extensive rear end damage on aluminum body.The elderly sister of Bruno Rusniak told Bill that her brother was pulled over by the Detroit Police one evening. For some unknown reason, rather than be subjected to a search, Bruno shifted the 4,920 pound car into reverse and slammed into the front fender of the squad car disabling it. Then, he sped home, drove the car into his garage, and pulled a tarp over it. There it sat for decades until his passing.

Bill contacted me to find out if the name Bruno Rusniak ever came up in any of my Detroit underworld research. He sent me a copy of the car's registration and Bruno's death certificate. I searched and found nothing about his involvement in the rackets, but for the record, Bruno lived his whole life at 5582 Caniff in Hamtramck. He served in World War II as a mechanic which became his life's work. Bruno died from a variety of heart ailments on November 25, 2004 and was buried at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Detroit.

After sheet metal repairs and straightened frame cradling a new gas tank.

After sheet metal repairs and straightened frame cradling a new gas tank.As fate would have it, the new owner Bill is also a mechanic and a car enthusiast. After he shipped the car to his garage, he changed the spark plugs, belts, and fluids, put some fresh gasoline in the tank, and sprayed some ether into the carburetor. The car started right up. Body shop repairs were made and new 7.00 x 20, six-ply whitewall tires were mounted. The Lincoln Deluxe Dual-Cowl Sport Phaeton limo is once again roadworthy.

Much to my surprise, Bill asked if I would like to take his classic car out for a drive the next time I'm in the Detroit area. That is an offer I can't refuse.

February 25, 2021

Detroit Pitchman Ollie Fretter

Ollie Fretter

Ollie FretterBorn in Cleveland, Ohio in 1923, Oliver "Ollie" Fretter moved with his parents to Royal Oak, Michigan when he was in his early teens. He graduated from Royal Oak Dondero High School in 1941. After serving in the military during World War II, Fretter borrowed $600 from an uncle to open an appliance repair shop.

By 1950, twenty-seven-year-old Ollie Fretter decided he may as well sell home appliances and consumer electronics. With the post-war G.I. Bill and Veterans' Administration funding boom, America moved from a nation of renters to a nation of home owners. Selling appliances and electronics was a forward-looking career move for Fretter. His first store opened on Telegraph Road, north of I-96 in Redford, Michigan. Within ten years, Fretter had eight Detroit area stores.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Fretter Appliance and Electronics ran print ads in all of Detroit's major newspapers. The ads ran on Mondays to advertise mid-week Wednesday sales and on Fridays to generate weekend sales. The ads featured photos of appliances with the "Lowest Prices in Town" listed beneath them. Fretter's headshot was prominently displayed near his slogan, "If I can't beat your best deal, I'll give you five pounds of coffee."

Typical Fretter Appliance Print Ad

Typical Fretter Appliance Print AdAn unidentified Fretter employee revealed to a Detroit Free Press reporter, "Fretter gave away about 200 pounds of canned coffee a month costing about $500. When coffee prices rose, Fretter ordered one-pound cans of coffee with the label Fretter's House printed on them listing the weight as five-pounds. Somehow, Fretter got away with it. The cans became gag items that most customers were good-natured about. My guess is these short-weight coffee cans would be valuable collectors' items today if any have survived.

In 1971, Ollie Fretter increased his advertising budget and shifted into television advertising. He starred in his own commercials projecting a hokey, amateurish charm 40 or 50 times a week over most small market TV stations. His ads ran in the afternoon and late nights when buying television time was cheaper than prime time.

At first, Ollie Fretter played it straight as an owner/pitchman, but to distract his potential customers from the mind-numbing repetition of his commercials, he began hamming it up with all sorts of silly promotions like dressing as various characters. Sometimes, he would appear as a Gypsy violist, a mountain man, George Washington on President's Day, Uncle Sam on the Fourth of July, Johnny Cash, or Mother Nature. He would do almost anything to sell a refrigerator, a vacuum cleaner, a television, or a stereo system.

Ollie Fretter became Detroit's King of Local Advertising despite newspaper columnists ridiculing him in their editorials. He cried all the way to the bank. When Detroit Free Press reporter James Harper asked Fretter why he appeared in his own commercials, he replied, "People like to think they're dealing with the owner of a business. A too professional approach is not good. People like to think they're listening to somebody just like them."

In May of 1980, Michigan Attorney General Frank Kelley brought a $25,000 lawsuit against Fretter Appliance and Electronics for violating the Item Pricing and Deceptive Adverstising Act. The company's media advertising and signs that hung in their chain stores proclaimed "The Lowest Prices in Town." Ollie Fretter and his lawyers failed to provide documented evidence to backup that long-held claim.

Fretter updated his company's advertising by making the products the focus. An off-screen announcer described the appliances and electronics featured that week. At the end, Fretter's image was superimposed over the products with him saying, "The competition knows me, you should too." The new approach reflected the loss of Fretter's consumer protection lawsuit and the increasing competition from Highland Appliance.

But there was also a new threat--the big box appliance stores popping up along the retail horizon. Advertising had gone from cute to cutthroat. By offering lost leaders (items retailers sold at a loss) big box stores like Best Buy, Circuit City, and Sam's Club undersold their competition. Fretter rolled the dice and took his company public on the New York Stock Exchange in 1986 to raise capital and expand into new markets to compete nationally.

Fretter's long-time competitor Highland Appliance filed for Chapter 11 bankrupcy in 1992. It owed its creditors $241 million dollars. Best Buy saw an opportunity and stepped in to fill the retail void by opening six big box stores in the Detroit area by the end of 1993.

Fretter bought up his biggest competitor Silo Electronics, but Silo hadn't posted a profit since the early 1980s. Fretter assumed Silo's debt and lack of liquid assets but expanded into more states anyway. The bottom dropped out of consumer electronics market due to stiff competition and falling stock values. Fretter spread his assets too thin and banks refused to lend him any more money. By 1995, all Silo Electronics stores closed, with all Fretter stores closing by the end of June 1996. Ollie retired after forty-six years in the retail business.

Fred Yaffe, president of the advertising agency that handled the Fretter account from1992 until 1995, noted, "It wasn't any one thing that killed Fretter's business. It was a bunch of things that all happened at once. He had serious competitors with deeper pockets, constant price wars in the appliance and electronics industries, and a lack of new products like VCRs and handheld video cameras."

Oliver "Ollie" Fretter lived out his life in Bloomfield Hills and died at Beaumont Hospice on June 29, 2014 at the age of ninty-one. He was survived by his wife of sixty-five years Elma M., his adult children Laura and Howard, and his grandchildren Alexandra, Andrew, and Catherine.

February 19, 2021

Myron "Mikey" Selik--Junior Purple Gang Alumnus

Myron "Mikey" Selik and Harry "H.F." Fleisher in Jackson Prison.

Myron "Mikey" Selik and Harry "H.F." Fleisher in Jackson Prison.Myron Selik was born November 16, 1912. He reached adulthood the same year Prohibiton ended which threw the rackets into a state of confusion. Drug trafficking, gambling, and labor racketeering were the primary money earners for organized crime now, but Mikey seems to have been most involved with burglary and extortion. He was mentored by Harry Fleisher--one of the original Purple Gang members.

In 1944, Republican party boss Frank McKay and some underworld Detroit gangsters wanted Michigan State Senator Warren G. Hooper killed. Hooper was scheduled to testify before a grand jury about graft payouts to legislators for voting against gambling reform in the horseracing industry. Organized crime stood to lose lots of money.

Senator Warren G. Hooper

Senator Warren G. Hooper Senator Hooper confessed under oath to Ingham County Prosecutors that he had accepted a $500 bribe to vote against a bill designed to protect against cheating in the horseracing industry. In exchange for immunity, he was willing to testify before a Michigan grand jury.

Only forty years old, Hooper was murdered at about 4:30 in the afternoon on January 11, 1945 when his car was run off the road on Highway 99 while he was driving home to Albion from the state capitol in Lansing. Hooper was shot in the head three times and his car was burning when the Michigan State Police arrived on the scene.

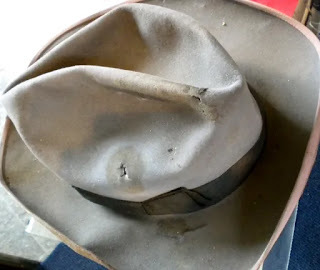

Hooper's hat with bullet holes.

Hooper's hat with bullet holes.Hooper's body was taken from the car by two passing motorists who threw snow on his smoldering clothes and on the inside of the car to dampen the fire. From examining the crime scene and Hooper's wounds, investigators determined that Hooper was shot at close range by someone in the car with him. The car was not torched. The fire was started by a lit cigarette the senator was smoking when he was shot.

Ingham County and Michigan State Police were clueless about who murdered Hooper until there was a break in the case. Sam "Sammy A" Abramowitz was out on parole for a robbery conviction. When he was implicated in the assassination plot, he plea bargained with the Ingham County prosecutor and turned informant.

Abramowitz did not know who pulled the trigger, but he did confess before a grand jury that four men tried to recruit him to participate in the hit for $500. The four men were Harry and Sammy Fleisher, original Purple Gang members; Pete Mahoney, an associate who just happened to be there; and Myron "Mikey" Selik, Junior Purple Gang member. The conversation took place at O'Larry's Bar on Dexter Avenue in Detroit--a known underworld hangout.

The men were convicted of conspiracy to murder Senator Hooper and sentenced to five years in prison. Mikey Selik and Harry Fleisher were also charged and convicted of armed robbery of the Aristocrat Club--a Pontiac, Michigan gambling resort they were shaking down for protection money. Both men were sentenced to 25 to 50 years on the robbery rap. After their appeal was denied, Harry Fleisher and Mikey Selik skipped town in 1947. They were at large for a couple of years.

Selik used the alias Max Green and went underground in New York City. Harry Fleisher traveled with a woman not his wife, under the assumed names of Mr. and Mrs. Marvin Goldwyn of Toledo, Ohio. They were sunning themselves on the beach in Pompano, Florida when the FBI caught up with him on January 18, 1950. A year later on February 1, 1951, Max Green (38)--alias for Myron Selik--was arrested with three other men in an unsuccessful $20,000 fur and jewelry robbery in the Bronx, New York. Both Fleisher and Selik were extradited to Michigan to serve their prison sentences.

When released, Harry Fleisher went straight and became a foreman in a Detroit steel warehouse. Fleisher died in 1978 at the age of seventy-five. Myron Selik is believed to have returned to the gambling rackets and ran a bookmaking operation. Selik died on August 7, 1996 at the age of eighty-three.

***

"Wanted--Myron 'Mikey' Selik--Conspiracy to Murder" (32 minute True Detective radio broadcast from July 14, 1950).

February 13, 2021

Bobo Brazil's Wrestling Legacy

Bobo Brazil

Bobo BrazilHouston Harris was born on July 19, 1924 in Little Rock, Arkansas. He grew up to become Bobo Brazil--the Jackie Robinson of sports-entertainment (professional wrestling). Bobo wasn't the first Black wrestler, but when he signed with the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), Brazil went mainstream to become the sport's first African American megastar.

The six foot, six inch, 270 pounder was playing baseball in the Negro League for The House of David when he was spotted by professional wrestler Joe Savoldi. In 1951, Savoldi suggested Harris give pro-wrestling a try where he could make some real money. At twenty-seven years old, with a wife and a passel of kids to provide for, Harris traveled to Canada from Benton Harbor, Michigan to learn the secrets of the squared circle. Once he knew the fundamentals, Harris began wrestling in small, Canadian and Midwestern venues as Bobo Brazil.

Before long, he signed with Jack Britton and Bert Ruby of Detroit's Big Time Wrestling. Edward George Farhat, also known in the ring as The (Original) Sheik, bought the organization in 1964. The Sheik and Bobo fought and bled their way through Michigan, Ohio, and Ontario in the longest running feud in professional wrestling. The Sheik was the most hated player in the game. He and Bobo grappled many times over the years trading the United States Heavyweight Champion belt back and forth. In the process, Bobo became a hero to many Black and White wrestling fans who despised The Sheik. His crowd-pleasing, finishing move was the Coco Butt (head butt).

Bobo Brazil was inducted into the WWF class of 1994 by his personal friend Ernie "The Cat" Ladd. Houston "Bobo Brazil" Harris died January 20, 1998 at Lakeland Medical Center in St. Joseph, Michigan after suffering a series of strokes. He was the father of six children.

Bobo Brazil was inducted into the WWF class of 1994 by his personal friend Ernie "The Cat" Ladd. Houston "Bobo Brazil" Harris died January 20, 1998 at Lakeland Medical Center in St. Joseph, Michigan after suffering a series of strokes. He was the father of six children.

***

Born Wayde Douglas Bowles on August 24, 1944 in Amherst, Nova Scotia, Canada, Bowles changed his name to Rocky Johnson when he signed with the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) in Atlanta, Georgia. His ring name was a tribute to his two favorite boxing greats--Rocky Marciano and Jack Johnson. At six foot/two, 262 pounds, Rocky Johnson cut an imposing figure, but like all Black professional wrestlers before him, Johnson endured racial slurs and battled racism early in his career.

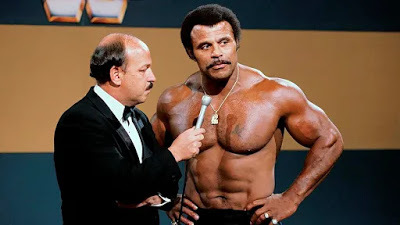

Rocky Johnson with announcer "Mean" Gene Okerlund

Rocky Johnson with announcer "Mean" Gene Okerlund"There is a lot of racism in professional wrestling then and now. Only now, it is more covered up," Johnson said in a cable TV interview. "I kept myself in shape, (but) the stuff going on in the South, I wouldn't go for it. They (the promoters) wanted to whip me on TV like a slave, but I said 'No! I came in as an athlete, and I'll leave as an athlete.' They respected me for that."

On December 6, 1974, Rocky Johnson became the first Black Heavyweight World Champion in the state of Georgia. When he teamed up with Tony Atlas, they were known as the Soul Patrol. They were the first Black, tag team champions in the World Wrestling Federation when they defeated the Wild Samoans on December 10, 1983.

Tony Atlas and Rocky Johnson--The Soul Patrol

Tony Atlas and Rocky Johnson--The Soul PatrolRocky Johnson retired from pro wrestling in 1991 and was inducted in the WWF Hall of Fame in 2008, but before retiring, Rocky Johnson passed the torch to his son Dwayne Johnson when Rocky and his father in law, Peter Maivia, trained Dwayne in 1995 for a career in the family business. After battling a bad cold, Rocky Johnson succumbed to deep vein thrombosis on January15, 2020 at the age of seventy-five.

***

Dwayne Douglas Johnson was the son of Rocky "Soulman" Johnson. As a boy, he grew up with the dream of playing in the National Football League (NFL). Dwayne entered The University of Miami on a football scholarship and played on their National Championship team during his freshman year 1991. Along the way, Dwayne earned a bachelor's degree in Criminology and Physiology.

Dwayne's childhood dream of going pro was dashed when he went undrafted in the 1995 NFL Draft. Undeterred, he tried out for the Calgary Stampede of the Canadian Football League. Only two months into his first season, he was cut due to injuries. It was then that Dwayne asked his father to train him for a career in professional wrestling. His grandfather Peter Maivia was a NWA wrestler and his father was a WWF wrestler. At six foot/five, 260 pounds, he had the physique for success in the ring but did he have the heart?

Rocky tried to discourage his son at first. He knew first-hand about the difficulties of being on the road away from family. Dwayne had a college education, something nobody else in the family had, but he was determined to wrestle. Rocky told his son he would train him on one condition, "I'm going to train you 150% because that's what it takes to be a champion." Rocky was hard on him, but Dwayne never gave up or complained.

Proud son Dwayne Johnson looks on as his father Rocky Johnson is inducted into the WWF/WWE Hall of Fame in 2008.

Proud son Dwayne Johnson looks on as his father Rocky Johnson is inducted into the WWF/WWE Hall of Fame in 2008.The following year, Dwayne Johnson signed his first WWF contract and slowly developed his charismatic, brash charm and boastful, trash-talking personality. As a tribute to his father, Dwayne took on the ring persona of The Rock. Within two years of entering Vince McMahon's WWF, The Rock won his first world championship belt, the first of seventeen titles he would hold in the next nine years. The Rock is considered by many as one of the greatest and most popular professional wrestlers of all time.

In 2004, The Rock resumed his Dwayne Johnson identity to pursue an acting career and establish his own film production company becoming one of the world's highest paid actors. Johnson's first starring role was in The Scorpion King along with other hits to follow like the Fast & Furious franchise and two Jumanji movies to name only a few.

As of 2021, forty-nine-year-old Dwayne Johnson's net worth is estimated to be 320 million dollars. His movies have grossed 10.5 billion dollars worldwide. Johnson has twice made Time magazine's 100 Most Influential People in the World list in 2016 and 2019.

In 2006, Johnson founded the Dwayne Johnson Rock Foundation, a charity that works with children who have illnesses, disorders, and disabilities to improve their self-esteem and help empower their lives. As for Dwayne's boyhood football dreams, they get played out yearly watching the Super Bowl like the rest of us.