Gregory A. Fournier's Blog, page 6

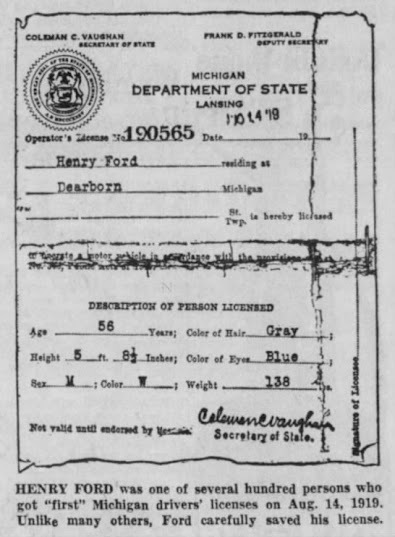

December 16, 2021

Haddon Sundblom, Santa Claus, and Playboy Magazine

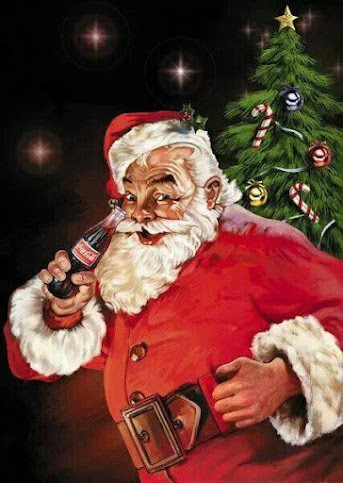

Haddon Sundblom's first Santa image for Coca-Cola in 1931.

Haddon Sundblom's first Santa image for Coca-Cola in 1931.Haddon Sundblom is one of the most successful and influential American commercial artists of the twentieth century. It would be difficult to find anyone who isn't familiar with Sundblom's grandfatherly images of Santa painted for Coca-Cola between the years 1931-1964. The company still uses these images over the Christmas holiday. Sundblom did commercial art for Coke throughout his years with the company giving their product a wholesome American image.

In addition to his Coke account, Sundblom created commercial art and advertising for Ladies Home Journal, Cashmere Bouquet Soap, Cream of Wheat, and many other national brands. He illustrated the famous Quaker Oats man and the infamous Aunt Jemima--two of his national trademark creations. In the mid-1930s, Sundblom did pin-up art and glamour pieces for pulp magazine covers and promotional calendars which were popular through the 1950s.

Miss Sylvania - 1960

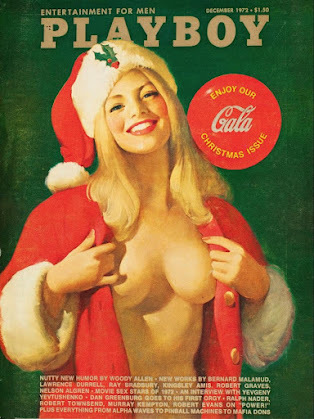

Miss Sylvania - 1960At the age of seventy-three, Sundblom came out of retirement for a commission that brought his art full circle. Playboy magazine asked Sundblom to paint the cover image for its December 1972 edition. He was able to merge his Santa imagery with his pin-up career in a painting he named Naughty Santa.

The Coca-Cola Santa Story

October 29, 2021

Detroit's Shock Theater

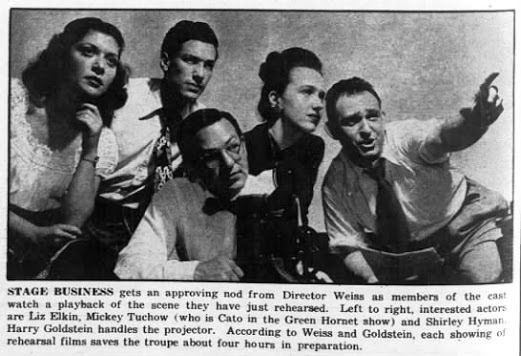

In 1957, Universal Pictures syndicated a television package of fifty-two classic horror movies released by Screen Gems called Shock Theatre. The package included the original Dracula, Frankenstein, Mummy, and Wolfman movies. Shock Theatre premiered with Lugosi's Dracula in Detroit on WXYZ channel seven at 11:30 pm on February 7, 1958.

Each syndicated television market had their own host. Detroit had one of the first horror movie personalities in the country. The show was hosted by Mr. X--Tom "Doc" Dougall--a classically trained actor who taught English at the Detroit Institute of Technology and moonlighted as a vampire on Friday nights. Unlike later horror movie hosts who would spoof their roles or riff on the movies they showed, Dougall was grimly serious and set a solemn tone for what was to follow. What most people don't know about Professor Dougall is that he co-wrote several Lone Ranger and Green Hornet scripts for WXYZ radio.

Each syndicated television market had their own host. Detroit had one of the first horror movie personalities in the country. The show was hosted by Mr. X--Tom "Doc" Dougall--a classically trained actor who taught English at the Detroit Institute of Technology and moonlighted as a vampire on Friday nights. Unlike later horror movie hosts who would spoof their roles or riff on the movies they showed, Dougall was grimly serious and set a solemn tone for what was to follow. What most people don't know about Professor Dougall is that he co-wrote several Lone Ranger and Green Hornet scripts for WXYZ radio.The opening of the show was memorable, but I was only nine years old when I started staying up every Friday night to see the classic monsters and mad-scientists--The Invisible Man comes to mind. This is how I remember the opening:

The show's marquee card came up with ominous organ music and a crack of thunder in the background. Replete in vampire garb with cape, Mr. X walked slowly on screen holding a huge open book announcing the night's feature in a scary voice. Next, he would say, "Before we release the forces of evil, insulate yourself against them." With a sense of impending doom, Mr. X continued, "Lock your doors, close your windows, and dim your lights. Prepare for Shock." The camera came in for an extreme close-up of Mr. X's face, more lightening and thunder effects, and finally his gaunt face morphed into a skull. Then the film credits would roll.

The show's marquee card came up with ominous organ music and a crack of thunder in the background. Replete in vampire garb with cape, Mr. X walked slowly on screen holding a huge open book announcing the night's feature in a scary voice. Next, he would say, "Before we release the forces of evil, insulate yourself against them." With a sense of impending doom, Mr. X continued, "Lock your doors, close your windows, and dim your lights. Prepare for Shock." The camera came in for an extreme close-up of Mr. X's face, more lightening and thunder effects, and finally his gaunt face morphed into a skull. Then the film credits would roll.There was something positively unholy about the show which made it an instant success with my generation of ghoulish Detroit Baby Boomers. The show's ominous organ music set the mood for the audience. The piece was listed only as #7 on a recording of Video Moods licensed for commercial television and not available to the public.

No video link to Detroit's Shock Theatre's opening has surfaced, but the above newspaper ad for the show gives an idea of the facial dissolve special effect. If anyone knows where I can find a link, Gmail me so I can add it to this post. Thanks.

Detroit's Baby Boomer Kid Show Hosts:

https://fornology.blogspot.com/2017/12/detroit-baby-boomer-kids-show-hosts.html

October 10, 2021

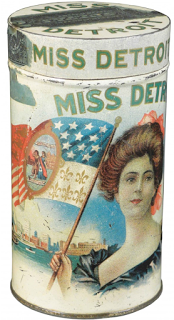

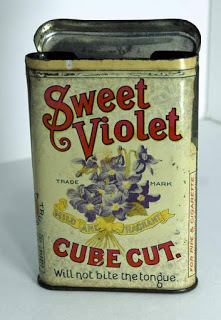

Detroit Tobacco Industry Once Known as the Tampa of the North

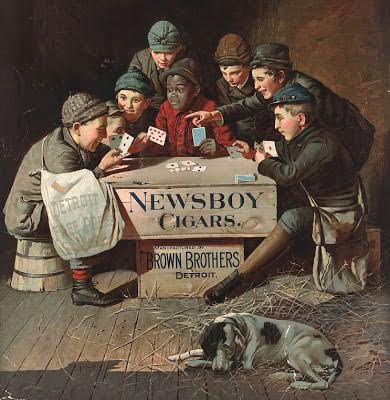

Only four years after becoming a state, the tobacco industry in Michigan got its start when George Miller became the first tobacconist in the city of Detroit in 1841. By the 1850s--with the help of New York's Erie Canal--many Germans migrated to Detroit. These Germans enjoyed smoking and knew how to produce excellent cigars; soon they dominated the city's industry.

Raw material was nearby in Southwestern Ontario. The Canadians produced a high-quality tobacco crop in sandy and silt-loam soil. With tobacco so close at hand, demand for Detroit's quality wrapped cigars turned a cottage industry into an early form of mass production employing thousands of workers throughout the Detroit area.

Long before Henry Ford's assembly-line, the cigar industry deconstructed the rolling of cigars into specialized tasks. Each worker performed one part of the process, so few people had the skill to make a whole cigar. Baskets or crates of cigars were moved from station to station down long tables. The process was efficient and Detroit cigars became known for their consistent quality.

Long before Henry Ford's assembly-line, the cigar industry deconstructed the rolling of cigars into specialized tasks. Each worker performed one part of the process, so few people had the skill to make a whole cigar. Baskets or crates of cigars were moved from station to station down long tables. The process was efficient and Detroit cigars became known for their consistent quality. Then came the American Civil War and the soldier's high demand for tobacco products. To the Yankee or Rebel soldier, tobacco represented the convenience and consolation of home. The hand-rolled cigarette was still an item of luxury, but the cigar represented victory, and the pipe comfort and solace. Soldiers North and South often relaxed by chomping on rich, gooey plugs of chewing tobacco or by smoking delicate clay pipes before, during, and after battles. Much of this tobacco was processed and packaged in Detroit.

Sixteenth governor of the State of Michigan (1873-1877) John Judson Bagley moved to Detroit in 1847. In his early twenties, he started his working career as a humble apprentice in a small chewing tobacco shop. After seven years, he bought the business and renamed it Mayflower Tobacco Company turning his company into an industry leader. Bagley manufactured a rectangular form of chewing tobacco in a tin with a friction-fitted lid that became an industry standard. Bagley made a fortune and helped make Detroit a leader in the manufacture of tobacco products.

Sixteenth governor of the State of Michigan (1873-1877) John Judson Bagley moved to Detroit in 1847. In his early twenties, he started his working career as a humble apprentice in a small chewing tobacco shop. After seven years, he bought the business and renamed it Mayflower Tobacco Company turning his company into an industry leader. Bagley manufactured a rectangular form of chewing tobacco in a tin with a friction-fitted lid that became an industry standard. Bagley made a fortune and helped make Detroit a leader in the manufacture of tobacco products.At the turn of the twentieth-century, the tobacco industry employed many young women--mostly Polish immigrants. In 1913, the ten largest Detroit tobacco companies employed 302 men and 3,896 women, making the cigar industry the largest employer of women in the city. The process of hand rolling cigars was labor intensive and involved some skill. Too tight and the cigar would not draw properly, too loose and the cigar fell apart. Although women were not organized into labor unions, they were able to make $25 to $40 a week. That was a good wage a hundred years ago.

A cigar company sit-down strike.On June 26, 1916, Detroit's San Telmo Company signed a contract with its unionized male cigar makers giving them a significant pay increase. The women wanted equal pay for equal work. Three days later, women at the Lilies Cigar Company walked off the job. Soon there were strikes shutting down all the major Detroit cigar producers. Through their united action, women workers achieved some of their demands.

A cigar company sit-down strike.On June 26, 1916, Detroit's San Telmo Company signed a contract with its unionized male cigar makers giving them a significant pay increase. The women wanted equal pay for equal work. Three days later, women at the Lilies Cigar Company walked off the job. Soon there were strikes shutting down all the major Detroit cigar producers. Through their united action, women workers achieved some of their demands.The center of the tobacco industry remained in the North until the 1920s. When Prohibition went into effect with the passage of the nineteenth amendment in 1920, the major marketplace for cigars--saloons and hotel bars--were closed and the social patterns of America were shaken.

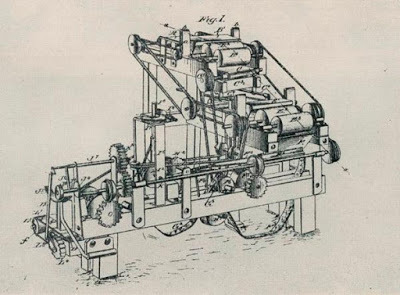

Patent office drawing of automatic cigarette making machine.But the writing was on the wall for Detroit's cigar and tobacco industry. The invention of the automatic cigarette rolling machine in 1881 reduced demand for cigars and other tobacco products. James Albert Bonsack's machine was patented and installed throughout many Southern states causing a shift in the tobacco industry away from the North. Inexpensive mass-produced cigarettes were all the rage in the fast approaching twentieth century. Detroit's ambition shifted too--towards the automobile business which would revolutionize the new century.

Patent office drawing of automatic cigarette making machine.But the writing was on the wall for Detroit's cigar and tobacco industry. The invention of the automatic cigarette rolling machine in 1881 reduced demand for cigars and other tobacco products. James Albert Bonsack's machine was patented and installed throughout many Southern states causing a shift in the tobacco industry away from the North. Inexpensive mass-produced cigarettes were all the rage in the fast approaching twentieth century. Detroit's ambition shifted too--towards the automobile business which would revolutionize the new century.In 1966, the last cigar manufacturer in Detroit--Schwartz-Wemmer-Gilbert--closed its doors. Detroit was once home to thirty-eight tobacco companies.

Another German dominated industry in Detroit was the brewing of beer. Here is the story of the Strohs family: http://fornology.blogspot.com/2015/02/detroits-strohs-brewing-company-with.html

September 22, 2021

Detroit Time Capsule Anthology

After a decade writing 500 Fornology posts, I'm proud to announce the publication of my fifth book Detroit Time Capsule, which is a collection of seventy-five of my re-edited, best Detroit posts including significant historic moments, biographies of people who left their mark on the city, and memories of media personalities in the early days of Detroit television.

Detroit Time Capsule is a trip down memory lane, which should resonate with nostalgic Baby Boomers and contemporary Detroiters with a taste for learning their town's rich history and heritage.

This anthology makes a great holiday gift for readers who have an interest in easy to digest Detroit history. Most chapters are not tied by a narrative thread and can be read in three to five minutes.

And finally, I want to acknowledge Detroit/Ypsilanti photographer Chris Ahern for his striking photograph of the Monument to Joe Louis, aka The Fist (1986) by Robert Graham.

September 15, 2021

"We Never Called Him Henry"-- Harry Bennett Polishes His Own Apple--Part Two

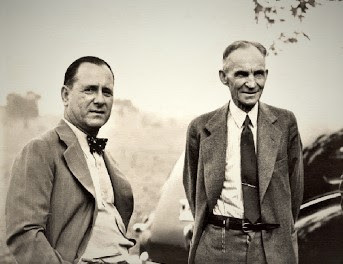

Harry Bennett with Henry Ford in Willow Run.

Harry Bennett with Henry Ford in Willow Run.

Much of Harry Bennett's "tell-all" memoir of his time with Henry Ford reads like a tattletale, supermarket tabloid about people within the Ford empire and the Ford family. I chose to write about several provocative sections of the book: how Bennett met Henry Ford and the open employment of gangsters at the Rouge plant, Henry Ford's anti-Semitism and ties to Adolph Hitler and Nazi Germany, how Bennett was paid, and Bennet's severance from the Ford Motor Company in 1945.

***

When Harry Bennett first met Henry Ford in 1916, the automobile mogul was fifty-three years old and Bennett was twenty-four. Bennett was on shore leave in New York City between Navy enlistments with a sailor friend. The two young sailors were brawling with some civilians and about to get arrested.

Well-known New York journalist Arthur Brisbane saw the fight and vouched for the sailors telling the police they acted in self-defense after they were set upon. The reporter convinced the patrolmen to release the sailors into his custody. Brisbane was on his way to interview Henry Ford and asked Bennett if he would like to meet the famous industrialist.

Brisbane introduced Ford to Bennett and began giving an account of the brawl he just witnessed where this five foot-seven inch/145 pound, former Navy boxer handled himself bravely. Ford listened with rapt attention and then offered Bennett a job, "I can use a young man like you out at the Rouge [plant]."

Bennett remembers refusing because he wanted to re-enlist in the Navy. Civilian life was not exciting enough for him, he told Ford.

"It's a rough lot out at the Rouge. I need some eyes and ears in the plant. I haven't got any policemen out there. Can you shoot?"

"Sure, I can!"

After some further coaxing, Ford convinced Bennett to give the job a try. "But I won't work for the company, I'll work for you." It was that relationship that ultimately caused problems for both men. Ford was looking for someone tough enough to manage plant security, but he also needed someone to protect him and his family from kidnappers, which was a serious problem for wealthy industrialists in the 1920s and 1930s.

"Mr. Ford's grandchildren were pushovers for kidnappers," Bennett wrote. "Mr. Ford told me to take care of the problem and hire anybody I wanted." Bennett justified his open hiring of underworld figures because they gave him "a capacity for protecting Ford and his family from criminal molestation." A number of Mafia dons were granted lucrative Ford concession contracts which were little more than payoffs for protection inside-and-outside of the plant.

Regarding Henry Ford's concern for his personal safety, Bennett says Mr. Ford was a good marksman and always carried a .32 cal pistol on his person. "In the early 1920s, Ford was getting an average of five threatening letters a week. Ford's [bodyguard] driver had a shoulder holster under each arm, and Mr. Ford had two, loaded Magnum revolvers with holsters built into the back seat of his car."

With over 500 former convicts on the Ford company payroll under the guise of rehabilitation, these gangsters were a good source of information forming an extensive intelligence network throughout the plant complex, reporting on United Automobile Workers labor activities and informing on Ford employees.

An additional benefit of having some hired muscle in the plant gave Bennett a ready source of manpower to unleash against UAW organizers when called upon. "Mr. Ford made me his agent with the underworld," he bragged. "I kept them obligated to me but [I was] never obligated to them." It took a bulletproof ego for Bennett to believe that. More likely, Bennett carried around Henry Ford's wallet so why kill off the golden calf?

***

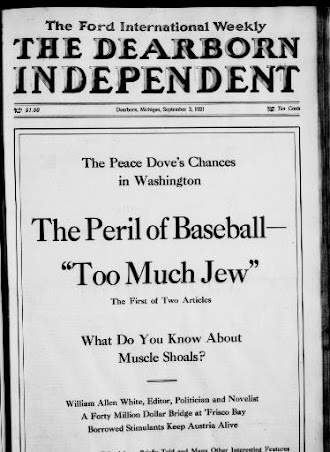

Another of Bennett's jobs was to protect Mr. Ford from himself when he could, and barring that, it was his job to pick up the pieces from Ford's bad judgements. In May of 1920, a Ford-owned newspaper called The Dearborn Independent began publishing anti-Semitic articles based on the spurious Protocols of Zion written surreptitiously in 1905 by Czarist propagandist Serge Nilus, to incite Russian civil onrest and polgroms against their Jewish population. The four small volumes carried the title The International Jew, each with its own subtitle.

A series of anti-Semitic articles ran ninety-one weeks in the Dearborn Independent, each with a run of 200,000 copies that was distributed and sold worldwide. A copy of the newspaper came with the sale of every Ford car during this period. In March of 1927 when the Independent named Chicago attorney Aaron Sapiro the "Jewish ring leader" and organizer of socialist farm cooperatives to gain control of American agriculture, Sapiro brought a libel suit against Henry Ford for a million dollars.

Typical provocative front page.

Typical provocative front page.Bennett blamed Dearborn Independent editor Bill Cameron and Dearborn Publishing Company general manager Ernest Liebold for "constantly stirring up Mr. Ford" with anti-Semitic slanders and propaganda. Every time Ford had trouble getting a loan, he complained it was a Jewish plot. At first, Ford wanted to fight this case to the finish, but it was a public relations nightmare in the press.

After five days on the stand, Bill Cameron fell on the sword and took responsibility for everything that ever happened in the Dearborn Independent. Cameron testified that Mr. Ford had no connection whatsoever with the editorial policy of the paper.

Ford was subpoened to testify in court the following Monday, but a Ford spokesperson reported to the local newspapers that while driving home on Sunday night, Mr. Ford's car was run off the road by a touring car driven by two men. A FoMoCo spokesperson stated that after the accident, Ford was treated for his injuries at Henry Ford Hospital and released under a doctor's care to his home for recovery.

As soon as Bennett found out about the attempt on Ford's life, he rushed to the Ford residence at Fairlane to see who his vengeance should fall upon. Ford said he felt fine and acted uncommonly calm about the accident. "It was probably kids on a joy ride," he said. "Forget about it, Harry." But Bennett wouldn't let it go, so Ford finally admitted, "I wasn't in that car when it went down the hill."

Then it struck Bennett that Ford was terrified of testifying in open court and the "accident" was a cover story. An earlier court appearance years before for another case revealed in cross-examination that Ford was poorly educated, had a limited vocabulary, was not well-read, and had little grasp of American history. It was humiliating and Ford vowed he would never testify in open court again. He would rather settle the Sapiro lawsuit out of court rather than subject himself to public riducule again.

Mr. Ford's lawyers drew up a formal apology as the basis for a settlement. Ford agreed to cease the publication of "anti-Setimic material circulated in his name, and he would call in all undistributed copies of The International Jew."

The apology further stated that "Mr. Ford had no knowledge of what had been published in his Dearborn Independent and was 'shocked' and 'mortified' to learn about it." The apology was printed on the front page of the Dearborn Independent, which shut down shortly afterwards in 1928. Mr. Ford paid everyone's court costs and stayed in his mansion licking his wounds.

But Henry Ford was a proud and stubborn man. Ten years later, his name became linked with Nazi Germany when he accepted the "Grand Cross of the German Eagle" from two German engineers on behalf of Adolph Hitler's admiration of Ford's industrial achievements.

A propaganda photo was taken in Dearborn, Michigan to commemorate the presentation, with Ford wearing the medal and sash around his neck with the German engineers flanking him on either side. By the next day, the photo appeared in newspapers across the country; by the following day, it was printed worldwide. The timing could not have been worse. In 1938, anti-German sentiment was growing in America.

On a petty, personal note, Ford had a grudge against Winston Churchill and hated him for a perceived, personal affront at a dinner party in London. On the other hand, Ford was pro-German. He and Adolph Hitler had a shared admiration for one another. After all, they were both poorly educated, self-made men. In addition, FoMoCo had a successful truck factory in Cologne, Germany that was very profitable for the corporation.

Ford went on to say that stories of Nazi brutality against their own people were British propaganda to drive America into another World War. The result of Ford's German diplomacy resulted in a serious drop in Ford sales at home. Mr. Ford did change his views about Herr Hitler after watching battlefront films of the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939. Once again, Ford humiliated himself in the American press and there was little anyone could do about it.

***

Bennett asserts in his autobiography that he never received a large salary from the FoMoCo, probably low grade executive pay due to his lack of management credentials. But Henry Ford had a private office in the Dearborn Engineering Laboratory where he kept a floor safe with a "kitty" [contingency account] from two million to four million cash dollars that Ford and Bennett would access without any red tape or company oversight.

Henry Ford also paid Bennett indirectly through real estate. Over the years, Ford bestowed upon his righthand man a lodge on Harsen's Island, the castle off Geddes Road in Washtenaw County, 2,800 acres in Clare County, and the Pagoda House on Grosse Ile. among others.

As Bennett tells the story, Mr. Ford had the Pagoda House built in the early 1930s for his family, but Mrs. Ford did not like the swift running current of the Detroit River. She feared for her grandchildren's lives. "Ford was disgusted and asked me if I had a dollar. I said, 'yes.'

"Give it to me and the place is yours."

Bennett did not like the mosquito infested property either. "No matter," he revealed, "I was glad to trade the Grosse Ile property for the ranch [290 acres of Arizona desert].... It was good for my sinus and arthritis."

Bennett made a fortune in real estate speculation to supplement his modest salary. This arrangement was clearly a money laundering scam to funnel money to Bennett for services rendered.

***

In the opening section of We Never Called Him Henry, Bennett wanted to correct the widespread notion that he was fired by twenty-eight-year-old Henry Ford II, grandson of the man he served for close to thirty years.

In a face-saving move, Bennett writes that young Henry Ford II said to him, "I don't know what I would have done without you. You don't have to leave--you can stay [at Ford's] for the rest of your life." Bennett maintains he always said, "When Mr. Ford retires, so do I." But, his employment records show Bennett did not officially resign from the corporation for weeks after Mr. Ford's death.

Henry Ford II with Harry Bennett in Bennett's office.

Henry Ford II with Harry Bennett in Bennett's office.Edsel Ford's wife and mother of Henry Ford II, Eleanor Clay Ford, was instrumental in Bennett's departure from Ford. She believed Bennett helped destroy her husband and vowed she would not let him destroy her son. There was a long history of bad blood between the Ford family and Bennett.

The newly christened Ford president's first duty was to fire Bennett. A man who had time for corporate intrigues was little use to the company as an executive. Bennett had to go, but he was the Ford patriarch's partner in crime, so he had to be handled carefully to avoid further scandal. Henry the Second, arranged to get Bennett a $424/month retirement check [not bad for 1945] and a Ford benefits package to simply walk away.

Bennett describes walking away from FoMoCo like "a man being let out of prison." Henry Ford II remembers it differently. Many years later, he told Detroit reporters that "Bennett stole plenty from the company, so I fired him. He was the dirtiest, lousiest, son-of-a [expletive deleted] I ever met in my life, except for Lee Iacocca."

September 8, 2021

Harry Bennett "Tell-All" Book About His Boss Henry Ford

Reprinted 1987 paperback edition.

Reprinted 1987 paperback edition.Harry Bennett officially joined the Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo) in 1917 at the Highland Park plant where the automobile assembly line was born. In his almost thirty years with the company, Bennett exercised influence far beyond his station upon Henry Ford, founder and corporation president. In Mr. Ford's later years when his health declined, Bennett was considered the power behind the throne.

Tired of the barrage of bad publicity Bennett received after his unceremonious firing by twenty-eight-year-old Henry Ford II, he began writing his autobiography of his time working for Henry Ford I "to set the record straight." But publishers reportedly would not touch We Never Called Him Henry because it was "dynamite."

Fawcett Gold Medal Books spokesperson Ralph Daigh asked Bennett to rewrite the book to make it "more objective." With the help of former Detroit Times newspaper reporter Paul Marcus, an edited version was released in 1951 by Fawcett in a 25-cent paperback edition. Marcus spent six weeks interviewing Bennett. "I prodded and nagged at his memory and asked countless questions."

The book had a 400,000 copy run and was billed as the "sensational inside story of intrigue within the Ford empire, its gangster connections, and its bloody union wars." But the book is next to impossible to find.

Folklore surrounding this book proports that the Ford family was offended by its publication, so they bought up as many copies as they could in a "capture & kill" attempt to keep it off the market. I contacted the Benson Ford Research Center, but a spokesperson at their archives told me he could neither confirm nor deny the story.

For my part, I remember coming home from the tenth grade in 1963 and seeing my mother intently reading a grimy, tattered and torn, well-read, Xerox copy of a book held together by a couple of brad tangs along the left edge. I asked my mother what she was reading, and she answered, "A banned book about Henry Ford and his family. A friend in my card club lent it to me." I was fifteen at the time, so I barely took notice. It wasn't until many years later when I was bitten by the history bug and Fordiana that I remembered my brush with this book.

In 1987, thirty-six years after its original publication, We Never Called Him Henry was republished by Paul Marcus with a new cover page by Tor Books for $3.95. Resale copies of this book are also rare and unavailable on Amazon, but I searched other used book retailers in July 2021 and found several copies ranging in price from $30 to $900. I bought an intact but yellowed copy to see what all the fuss was about.

Without going into the specifics of the book, I feel Bennett tries to portray himself as a sympathetic person who only did what Henry Ford asked him to do. He attempts to sanitize his public image by making himself the hero of his own story by blaming others and justifying all the right reasons for doing all the wrong things. Although he takes some roundhouse punches and jabs at the Ford family, the former Navy boxer never lands a punch.

In January 1974, Detroit Free Press feature reporter David L. Lewis convinced Harry Bennett to sit for a profile interview in Las Vegas, Nevada for "Detroit Magazine." The article was a personality piece about Bennett's private life after Ford. When Lewis asked Bennett his opinion of his own book, he answered:

"I didn't like the book at all. The way it was written made me sound like a 15-year-old-kid. [The book] made it seem like I was ridiculing Mr. Ford. When I first saw the cover, I knew I would be loused up. The picture of Mr. Ford made him look dead.... I got so I didn't like Marcus [the ghost writer] either. The longer he was with me, the more snarly he was."

Original 1951 paperback book cover.

Original 1951 paperback book cover.Bennett's response to the book which bears his name is just another example of his tendency towards disassociative behavior when it comes to taking responsibility for his actions.

August 15, 2021

Hoarders Henry and Clara B. Ford

Clara B. and Henry Ford

Clara B. and Henry FordAfter Mrs. Clara Bryant Ford died at the age of eighty-four on September 29, 1950, lawyers, executors, and archivists discovered in the Ford family's Fair Lane mansion a massive accumulation of memorabilia and business documents tucked away in shoe boxes, desk drawers, file cabinets, and dressers.

Among their findings in the fifty-five room, greystone mansion were records from the earliest days of the Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo), 25,000 assorted photographs, bales of greeting cards tied with string, blueprints, contracts, maps, legal documents, personal letters, magazines, newspaper articles, and Henry Ford's "jot books."

Archivists filled 24 document boxes with Christmas cards alone and another 11 boxes with financial receipts for common household expenses from 1889 to 1950. Also found lying around carelessly was $40,000 in loose cash, 10,000 unopened letters, and many uncashed dividend checks.

Fair Lane Mansion

Fair Lane MansionIn their fifty-nine-year marriage, Henry and Clara lived in twelve different places before they built Fair Lane, and apparently neither of them ever threw anything away. Collectively, the treasure trove of documents was dubbed the Fair Lane Papers and occupied more than 700 feet of shelf space in double-tiered, steel document racks installed above the filled-in indoor swimming pool at the mansion. A full-time staff of sixteen historians, librarians, and archivists was hired by the Ford Foundation to organize and catalogue this vast, new documentary resource.

The operation was split into two units. The Records section was led by Dr. Richard Ruddell, a professional librarian whose team cataloged, annotated, and microfilmed over five million perishable papers and photographs. Their offices were on the main floor at Fair Lane.

The Living History section was led by Dr. Owen Bombard of Columbia University. His office was the master bedroom upstairs where Henry Ford had died six years before. The combined objective of both units was to assemble a rounded picture of the late industrialist.

Dr. Bombard set out to capture the living history about Henry Ford by interviewing and recording three hundred people who knew Mr. Ford. Participants were asked to share their tape recorded memories of the auto magnate. Only five people declined the invitation. Two people said they had nothing significant to add, and three former FoMoCo employees harbored resentment against the old man and did not want to be recorded.

On May 7, 1953, Detroit Free Press feature reporter Ed Winge asked Dr. Bombard in a interview if former Ford security chief Harry Bennett would be invited to record his memories for the oral history project. Bombard cautiously replied, "Bennett hasn't been approached yet. But he may be contacted in the future if it is felt that he has something to contribute."

For background, Harry Bennett published his autobiography in 1951 titled We Never Called Him Henry about his controversial years as Mr. Ford's right-hand man and company enforcer. The Ford family was united in their contempt for the former Ford Security chieftain, although a copy of his book is one of many books written about Henry Ford in the archive's collection.

Throughout the1920s and 1930s, Henry Ford was the world's best known American citizen. Because of the intense public and world interest in the enigma that was Henry Ford, his decendants opened the Fair Lane archives to historians, scholars, and authors. The Fair Lane Papers collection has since moved to the Benson Ford Research Center adjacent to Greenfield Village.

July 31, 2021

The Spirit of Detroit, The Fist, and Detroit Time Capsule

History is fascinating in what it shows and tells and what it does not. My newest nonfiction book is a collection of seventy-five of my best Detroit blog posts called Detroit Time Capsule, which will be coming out this fall. Each chapter tells the story of some of the people who left their mark on Detroit history or its culture.

For the front cover, I chose a visually striking closeup view of The Spirit of Detroit by gifted Detroit photographer Chris Ahern. Searching for information about the building of the sixteen foot bronze statue and its dedication on September 23, 1958, I came across this color film I have linked below that tells the whole story.

To present a broader view of who and what the City of Detroit represents, the back cover photo will be a black & white closeup photo by Chris Ahern of Joe Louis' fist. I am anxious to see what my bookcover designer comes up with.

June 18, 2021

Rubin "The Voice" Weiss and His Wife Elizabeth "Woman of a Thousand Voices"

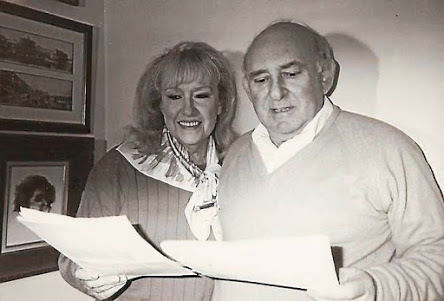

Elizabeth and Rubin Weiss rehearsing.

Elizabeth and Rubin Weiss rehearsing.Rubin Weiss was born sometime in 1921 in Detroit, but no public record was recorded in Wayne County. He may have been born at home which was more customary in those days. As a child, he performed in Yiddish skits and plays within Detroit's growing Jewish community. Rube attended Northern High School and earned a master's degree in English while attending Wayne State University.

In December of 1941, Weiss entered the United States Army and fought in the European theater of World War II and rose to the rank of captain. At war's end, Weiss decided to try his hand at acting in New York City, but after a year of struggling, he decided to return to his family in Detroit and landed a job as an English teacher at his high school alma mater from 1946 through 1952. To supplement his modest teaching income, he picked up what radio and advertising work he could get. As soon as he was sure he could make a living in radio, he quit his day job.

Early in Weiss' WXYZ-Radio career, he specialized in playing "bad guys," much to the disappointment of his mother. His voice was much larger than he was at five-feet, five inches. His voice was versatile, and Weiss often played four or five roles in a single fifteen-minute episode. He was a featured player on popular Detroit radio shows like The Green Lantern, Challenge of the Yukon, and The (original) Lone Ranger, where Weiss met his future wife Elizabeth Elkin in 1948.

Later in Rube Weiss' career, he would run into people randomly who had no idea who he was until he spoke in his distinctive, resonant voice. Not only was Weiss' voice familiar because of his work in radio and television, he was the raucous announcer for "Saturday, At Detroit Dragway" heard on pop radio stations all over the Detroit and Windsor airwaves in the 1960s. What many Detroiters do not realize is that Weiss played Santa for sixteen years at the Hudson's Thanksgiving Day Parade. When fans would meet Weiss in person, they often remarked, "You sound taller on radio," his retort was, "I'm six-five when I stand on my money."

Rube Weiss said the most fun he ever had in his long career was being a regular on Soupy Sales' WXYZ-TV evening show at eleven o'clock. Rube and a talented cast of radio performers took their schtick to the small screen. His characters included big game hunter Colonel Claude Bottom, loudmouth pop tune composer Shoutin' Shorty Hogan, detective Charlie Pan, and The Lone Stranger's sidekick Pronto.

Weiss was a much sought-after freelance pitchman for Detroit and national brands. A short list of the brands he lent his voice talents to are Kay's Jewelers, Velvet Peanut Butter, Midas Mufflers, Chrysler Corporation, Kellogg's Special K, Lincoln Continental, and Marlboro cigarettes.

Rubin Weiss passed away from an "internal infection" on April 25, 1996 at the age of seventy-six in Huntington Woods. Weiss' professional awards are too numerous to mention. Suffice it to say he won an American Federation of Television and Radio Actors Guild (AFTRA) Gold Card Award and several Emmy and Clio awards for his extensive work in radio. He is buried at Clover Hill Park Cemetery in Birmingham, Michigan.

***

Rube's wife Elizabeth was no less distinguished in her career than her husband, while also giving birth and being the proud mother of five children. Elizabeth Elkin was born in Detroit in 1925. Her talent as an artist and actor got her into Detroit's Cass Technical High School where she majored in Commercial Art. During World War II, Elizabeth became one of the youngest draftswomen in Detroit drawing plans for fighter airplane parts.

After the war, Elizabeth returned to the stage at Wayne State University performing in classical plays like Taming of the Shrew and Oedipus Rex at the Bonstelle Theater which was originally the Temple Beth El on Cass Street (Piety Row) when it was built in 1902. Elizabeth honed her acting skills and landed a job doing summer repetory theater in New York City where she earned her Actor's Equity card. While appearing in The Importance of Being Ernest with the Actor's Company in Detroit, she became reunited with Rube Weiss, who was directing the play. They fell in love and married at Workman's Circle in 1949.

Elizabeth thought her regular voice was ordinary, but she could do dialects, foreign accents, or whatever a role required. A Detroit newspaper profiled her as The Woman of a Thousand Voices for her countless radio and television commercials.

Elizabeth and Rube's home was a gathering place for actors, artists, scholars, and comedians, where she became the hostess and gourmet cook. The Weiss home became so popular that the family was dubbed the Jewish Waltons. The family led a rich social life grounded in Elizabeth's love of Jewish culture.

Later in life, she performed in many Jewish Ensemble Theater Yiddish language productions. Rube would regularly appear on Detroit television celebrating Jewish holidays. Both of them were active in their synogogue and the Jewish Community Center of Metropolitan Detroit. Elizabeth taught an Institute for Retired Professionals (IRP) Yiddish language group for many years.

Elizabeth Weiss was a lifetime member of the Screen Actor's Guild and AFTRA. She received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Alliance for Women in Media, and she was inducted in the Silver Circle of the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Like her husband, Elizabeth received many professional and community service awards too numerous to list here.

But without a doubt, Elizabeth was most proud of her large and devoted family of five children, sixteen grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren who continue to be inspired by her example. Elizabeth Elkin Weiss passed on at the age of ninety on September 18, 2015. Her funeral was held at the Ira Kaufman Chapel, and her remains are interred beside her husband at Clover Hill Park Cemetery.

June 11, 2021

Detroit History Under Marsha Music’s Watchful Eyes

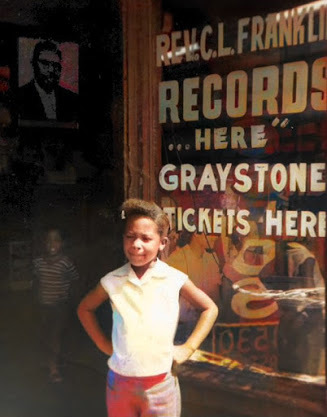

Marsha Battle Philpot (aka Marsha Music) is a familiar Detroit figure and longtime booster of the city who describes herself as "a writer and griot (storyteller)" of Detroit's post-World War II history, and its gentrification over fifty years later. Born on June 11, 1954, Marsha is the oldest child of the late blues record producer Joe Von Battle and his second wife, the late Westside beauty, Shirley (Baker) Battle.

Joe ran a blues and gospel record shop with a makeshift recording studio in the back room on Hastings Street, at Mack Avenue, just north of the Black Bottom area of Detroit. Joe recorded John Lee Hooker, Rev. C.L. Franklin and his fourteen-year-old daughter Aretha, among many other singers long forgotten.

Joe met Shirley Baker as she waited on the streetcar outside of the record shop, and he gave her a job. Soon he was smitten, despite being married with four teenaged children. After several years of going together, Joe bought Shirley a large house in Highland Park, a city within Detroit’s city limits, and he divorced his first wife. After Joe and Shirley had two children, they made it official and married.

Marsha never knew of her parent’s early unmarried status until after her mother’s passing at age 79. "I grew up in the era of Highland Park’s lush prosperity, and I would have led a very middle-class life, but every weekend, there I was on teeming 12th Street, working at my father's record shop. I came to love the neighborhood and its people." Joe's original record shop on Detroit's Eastside was bulldozed to make room for the Chrysler Freeway and urban renewal which Joe and others astutely described as "Negro removal."

Joe opened his new shop on 12th Street in Detroit's Westside in 1960 while struggling with alcoholism and Addison’s Disease. Seven years later, civil strife and conflagration consumed the 12 Street neighborhood in what history notes as the Detroit Riots. Some social historians and Black Detroiters have come to describe the event as "The Rebellion" as the social and economic forces leading to the insurrection of July 23, 1967 predated the event by decades.

As a direct result, Marsha became an activist during the turbulent 1960s. The late General Baker, a founder of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, became a surrogate father to Marsha. Highland Park had top schools during Marsha Battle’s early years and she was a good student, trained in classical music. Reeling and adrift, as her father’s drinking and conflict in the home worsened, she got pregnant at the age of sixteen and never completed high school. Her father died in 1973. Shirley worked after Joe's death cleaning offices for the Ford Motor Company. Shirley was able to support her two youngest children and put them through school. She passed away in 2008.

Marsha went to work at the Frito-Lay snack plant in Allen Park, Michigan to support her son, and at twenty-two year old had another son. After eleven years at the Frito plant, the single mother of two came into her own when she was elected to lead Local 326 of the Bakery, Confectionary, and Tobacco Worker's Union, at the age of twenty-eight. Her election was notable on several counts because she was the first African American, the first woman, and the youngest person to ever serve as union president representing workers from Frito-Lay, Taystee Bakeries, Hostess Bakeries, Wonderbread, and many other affiliated bakers and confectioners in Detroit and beyond.

Her main cause was to fight concessions that management was trying to enforce throughout the industry. Marsha brought new blood and energy to the job. “The people who work in these shops pay my salary, put clothes on my back, and feed my kids. I have to represent their interests.”

The father of her second son was an on-air news personality on WABX, and Marsha spent much of her twenties as what she calls a “rock chick.” With her father’s country blues and gospel roots, her love for the Motown Sound, the British Invasion and hard rock music on Detroit’s underground radio station, each genre expanded her musical appreciation ever wider.

Marsha, a voracious reader, loved to write since childhood, but it was not until the growth of the internet that her writing took off in an unusual way. Around 2000, while searching on eBay for a new watch, she struck up a conversation with a seller which lead to an invitation to join an “online wristwatch community.” She loved wristwatches and began to write about them on moderately high-end, international connoisseur’s watch sites.

Marsha also began to expand on her writing and wrote about growing up in the Detroit music world. Much to her surprise, in the world of watches there were some record collectors too who recognized the names of her father’s record labels: JVB, Von, and Battle Records.

Marsha realized there was knowledge about her father’s recordings among blues collectors worldwide, but there was very little known about him. A fire grew within her to return Joe Von Battle’s name to public notice and gain him the recognition he deserved and was deprived of when his larger legacy went up in smoke during that horrible summer of 1967.

Marsha also began writing for a group dedicated to music headed by rock critic Dave Marsh, who had long encouraged her writing. In 2008, she started a blog entitled Marsha Music. After a short time, she encountered many blues scholars on The Real Blues Forum, headed by author Paul Vernon, who were estatic to read stories about Joe's Record Shop.

Marsha, like her father, struggled with alcohol but adopted a life of sobriety in 1987 at age thirty-three. She returned to her family home in Highland Park in 2000, but in a cruel irony it burned down in an electrical fire in 2007. Marsha has been divorced twice and was widowed in 2018.

Through it all, she has written about her life in Detroit. Under the pen name of Marsha Music, she is an author whose essays, poems, and first-person narratives about Detroit's history appear in many notable anthologies such as Sonic Rebellion: Music as Resistance, Heaven Was Detroit, and A Detroit Anthology.

Marsha is on a crusade to bridge the gap between Detroit's past and its present. Lots of city history has happened in between, about which Marsha writes and eloquently speaks. Marsha wears dramatic clothing, hats, and turbans, striking a commanding presence wherever she appears. She is a much sought-after speaker with a forward-looking message.

"[Detroit] needs a restorative movement to heal what has happened here, as the working people of the town competed against themselves over the right to a good life. We have to share stories about the experiences of the past era. As we move forward in Detroit, there must be a mending of the human fabric that was rent. Small continual acts of reconciliation are called for here."

Marsha has appeared on HBO, The History Channel, and PBS. In 2012, she was awarded a Kresge Literary Arts Fellowship, and in 2015, the Knight Arts Challenge. In 2017, she was a narrator in the documentary 12th and Clairmount about the origins of Detroit's civil upheaval of July 23, 1967. Her poetry was commissioned for a narrative performance with the Detroit Symphony in 2015 and another for the Michigan Opera Theatre in 2020.

Marsha is currently completing a film project and book about her father. And if that wasn't enough, as of 2021, Marsha Battle Philpot began serving on the Board of Directors of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

In 2020, Marsha retired after a career with the Detroit County Court system of almost thirty years; currently, she lives in the Palmer Park district of Detroit. Her long and distinctive list of accomplishments and her dedication to public service have revived her father’s legacy as a Detroit music pioneer. Marsha’s achievements would have made her parents proud.

Before Berry Gordy There Was Joe Von Philpot Producing Records in Detroit