Gregory A. Fournier's Blog, page 5

May 14, 2022

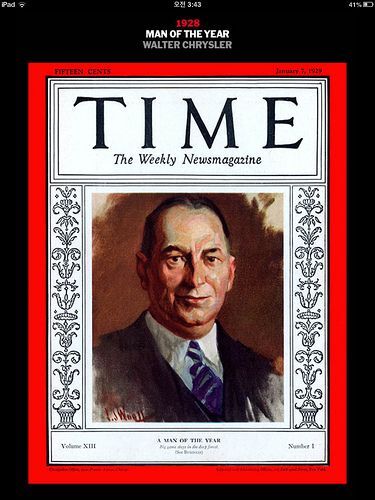

Walter P. Chrysler--Unlikely Automobile Titan

Walter P. Chrysler with his Chrysler Six.

Walter P. Chrysler with his Chrysler Six.Walter Percy Chrysler was born in the prairie town of Wamego, Kansas on April 2, 1875. As a young boy, he admired his father and the work he did as a railroad engineer for the Kansas Pacific railroad. He loved the excitement of the roundhouse and the mightly roar of the steam locomotives that were serviced there.

Sometimes, young Walter was allowed to ride with his father in the locomotive cab as the train cut through the quiet countryside. He would pull the whistle cord announcing the passage of the train through small towns and sleeping villages.

Walter's early association with the raw power of the steam locomotive instilled in him a fascination with mechanics, but Walter's father wanted his son to enter college after high school. Much to his father's disappointment, seventeen-year-old Walter began a four-year mechanic's apprenticeship in a railroad machine shop sweeping the floor.

Walter was anxious to become a journeyman machinist and master mechanic, so he could afford to marry his high school sweetheart. To supplement his chosen career, Walter was an avid reader of Scientific American magazine, where he earned a mechanical engineering degree from International Correspondence Schools headquartered in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Chrysler worked for several Western railroads as a itinerant mechanic who soon developed a reputation as a gifted, problem- solving engineer. He was particularly skillful at fine-tuning the valves of the massive steam-powered locomotives. After a year of traveling as a journeyman mechanic, he landed a foreman's assistant job at the Sante Fe roundhouse in Wellington, Kansas.

After working another year there, Chrysler was able to save some money. He was homesick for his hometown, but more importantly, he was lovesick for Miss Della V. Forker, his Ellis, Kansas girlfriend whom he married on June 4, 1901.

Della Viola Folker

Della Viola FolkerThe bride's family and friends felt Della had married beneath her station in life. They preferred she marry a professional or a businessman rather than a train mechanic. Her parents did not fully appreciate what hard work and ambition lurked beneath the surface of their son-in-law.

The happy couple started married life with $60. They spent the next two years in Salt Lake City where Walter worked for the Denver and Rio Grande Railway at thirty cents an hour for a ten-hour day. He rose through the ranks from crew foreman, shop foreman, and master mechanic. As his reputation for plant efficiency grew, so did his family with two daughters and two sons. He needed to find a job that paid more.

In 1908 at the age of thirty-three, Walter Chrysler was offered the job of general works manager of the American Locomotive Company (ALC) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at a starting salary of $8,000 a year. In two years, he turned the ailing company around by showing a profit for the first time in years. The company's bankers took note. Chrysler was asked if he had ever thought about entering the automobile business. Of course he had.

***

Chrysler was an automobile enthusiast from the beginning of the industry. In 1908, he went to the Chiciago Auto Show and fell in love with a Locomobile touring car with a $5,000 price tag. He could only justify spending $700 from a family savings account, but he had to have that car.

Chrysler borrowed $4,300 from a local banker when he found a friend who co-signed for the loan. The car was painted ivory white with red interior trim and a cushioned bench seat. The canvas top was khaki-colored.

1908 Locomobile with equipped tool box on the running board.

1908 Locomobile with equipped tool box on the running board.Rather than drive the car to Pittsburgh over unimproved country roads, Chrysler shipped the car home by rail. Once in town, he hired a team of horses to tow his new car home. For the next three months, Chrysler disassembled and reassembled the car no less than seven times. After he was familiar with the car's mechanical systems, he gassed it up and became a motorist. Soon after he paid back his car note, Chrysler bought a six-cylinder Stevens-Duryea.

The following year, Chrysler was summoned to New York City to discuss a business proposition. He met for lunch with Charles W. Nash, president of Buick Motor Company, who was looking for someone to become production manager at his plant to reduce costs and increase profits.

Nash asked Chrysler what ALC was paying him yearly. By then, he was pulling down $12,000 a year. Nash offered Chrysler a 50% cut in pay with yearly performance bonuses to move his family to Flint, Michigan and manage Buick Motors.

Recognizing the long term future of personal transportation, Chrysler turned his back on the railroad industry in a move that would change his life forever. After eighteen months under Chrysler's direction, the Buick line outperformed other General Motors models. Production soared from 50 cars a day to 550 cars a day. He was soon promoted to vice president and general manager of Buick Motors for the next three years earning $50,000 a year.

In 1915, original General Motors founder William "Willie" Durant bought back his company after a hostile takeover by bankers and stockholders. He traded stock from his successful startup company Chevrolet and brought the Chevy brand under the GM banner, once again becoming the president and chairman of the board.

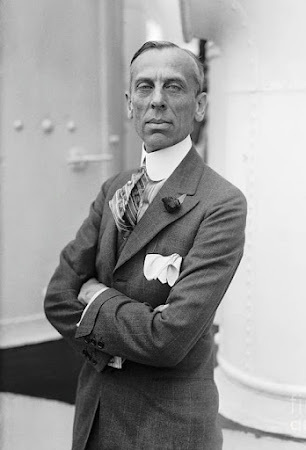

William "Willie" Durant

William "Willie" Durant Chrysler turned in his resignation, but Durant recognized his value to the corporation. Durant offered Chrysler a three-year contract making him president of Buick at $10,000 a month salary with a yearly half-a-million-dollar bonus of GM stock. He would report to nobody but Durant himself.

Under Chrysler's leadership, Buick became GM's strongest brand and the most successful automobile brand in the country, but Durant and Chrysler had different management styles which led Chrysler to resign after his three-year contract ran out. Durant bought out Chrysler's GM stock for ten million dollars making him one of the richest men in the country. Their parting was amicable.

Within the year, Walter Chrysler assumed directorship of the Willys-Overland Motor Company of Toledo, Ohio, for a one million dollar a year salary. Two years later, he left Willys-Overland over disagreements with the company's owner.

In 1921, Chrysler bought controlling interest in the struggling Maxwell Motor Company. Over the next several years, he phased out the Maxwell brand which was drowning in debt. Chrysler and several engineers he hired away from Studebaker Motors developed a high compression, six-cylinder engine. With auto bodies built by the Fisher Brothers, the new car was named the Chrysler Six and took the automobile world by storm in 1924.

The basic model included at no extra cost to the buyer, the first high-compression, inline six-cylinder engine with a top speed of 70 mph; the first replaceable oil and air filters to extend engine life; full pressure lubrication from an external oil pump; a fluid drive transmission for smooth shifting and greater performance; four-wheel hydraulic brakes for improved stopping distance; the first emergency brake as standard equipment in a low-priced automobile; and the first fuel and temperature gauges on the dashboard. The Chrysler Six sold 32,000 units for under $2,000 each in its first year of production.

In 1925, the Maxwell Motor Corporation was reorganized into the Chrysler Corporation. The old Chalmers engine plant was purchased and renovated for production of Chrysler's new engine, but it soon became clear that the new corporation still had trouble keeping up with demand.

In 1928, Chrysler purchased the Dodge Brothers' state-of-the-art factory complex and its extensive inventory from Dillon, Read & Company for $170,000,000, much of it in Chrysler stock. That same year, he created the Plymouth brand as Chrysler's low-priced competition for Ford and Chevy. In what seemed like overnight success, Chrysler Corporation became one of Detroit's Big Three automakers.

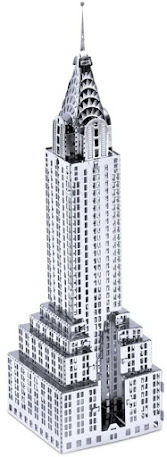

Also in 1928, Chrysler's adult sons showed no interest in the automobile business, so their father created a separate real estate venture to be managed by them. Between 1928 and 1930, he personally supervised the construction of the seventy-seven story Chrysler Building in New York City, which remains one of the world's great art deco monuments.

Model of Chrysler Building

Model of Chrysler Building For his skillful piloting of the Chrysler Corporation into one of America's Big Three automakers and his undertaking of the construction of the Chrysler Building in Manhattan, Walter P. Chrysler was honored as Time magazine's 1928 Man of the Year. In 1935, he stepped down from the presidency of Chrysler but continued on the board of directors.

***

On May 26, 1938, sixty-three-year-old Walter Chrysler suffered a stroke at this Long Island, New York estate. While he recovered at home, his beloved wife Della died just over two months later from a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of fifty-eight on August 8th. Walter Chrysler survived for two more years before dying from a second stroke on August 18, 1940 at the age of sixty-five.

A notice was posted at all Chrysler plants on Wednesday, August 21st, that all machinery would be shut down at 10:00 am and workers were to spend fifteen minutes in silence as a tribute to Chrysler while his funeral services were being held at All Saints' Church in Great Neck, Long Island, New York City.

All Chrysler Corporation vice presidents and directors were named honorary pallbearers. Speaking at the funeral service, manufacturer and Detroit Tiger owner Walter O. Briggs said, "Walter P. Chrysler symbolized the vision and courage which made America great."

President of Chrysler Corporation of Canada John D. Mansfield said, "Walter P. Chrysler was one of the great industrialists of modern times. His death has taken from the world one of its giants."

Richard T. Frankensteen, director of the United Auto Workers (UAW) spoke for the rank and file, "Chrysler's passing is cause on the part of Chrysler workers for deep regret. Despite temporary disagreements, Walter P. Chrysler was a man sincerely desirous of working to improve the lot of his workers with his general principles of fair dealing with labor."

After Chrysler settled a contract dispute with the UAW's sit-down strike in 1937, he summed up his pride and appreciation in the local Detroit newspapers for his workforce. "There is more to industry than money and machines. There are men. I have worked too many years on account of my own family to be forgetful that it is their women and children that men keep on working. How could I be unmindful of that obligation when I am so proud of what we have accomplished together?"

Walter Chrysler identified with is workforce because of his years of personal struggles as an underpaid mechanic and machinist. With all of his triumphs, he was at his core a simple man of simple tastes who was happiest when he was out in his factories rubbing elbows with the men who stood where he once labored.

Walter and Della were interred in their family masoleum in Sleepy Hollow, Tarryton, New York. They were survived by daughters Thelma and Bernice, and sons Walter Jr. and John.

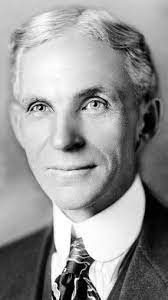

Henry Ford had a different approach to the United Auto Workers and labor relations.

April 22, 2022

Dodge Brothers Stand Up To Henry Ford

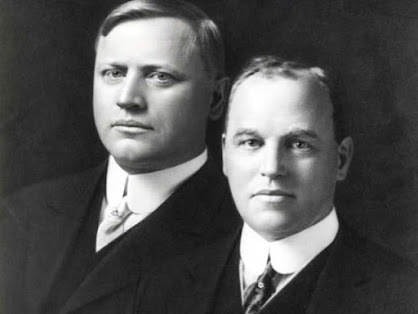

Automobile pioneers John and Horace Dodge

Automobile pioneers John and Horace DodgeJohn Francis Dodge [October 25, 1864 - January 14, 1920] and Horace Elgin Dodge [May 17, 1868 - December 10, 1920] were born in the era of the horse and buggy, and the marvel of the age, the steam engine locomotive. They were born in Niles, Michgan where their father Daniel Rugg Dodge operated his own machine shop next to his house repairing steam engines for boats and farm equipment. He often had to machine his own custom, precision parts.

In addition to his sons' traditional book learning, John and Horace learned to operate machine tools under the watchful eye of their father. Both boys were mechanically inclined. The family moved several times before settling in Detroit in 1886 where work in the stove, boiler, carriage, and wagon industries was booming. The brothers apprenticed in different machine shops aound Detroit learning their trade to become skilled journeymen.

In 1892, the brothers began working in Windsor, Ontario, at the Dominion Typograph Company owned by Frederick Samuel Evans. While working for Evans, Horace and John invented and manufactured the enclosed four-point, wheel ball bearing hub for bicycle pedal assemblies which made biking easier and more enjoyable.

The brothers were granted a patent in 1896 and went into business with Evans to create the popular E&B [Evans and Dodge] bicycle which soon became known as the "Maple Leaf." In 1900, they sold their interest in the company for $7,500.

With that start-up money, the Dodge brothers were able to open their first machine shop called the Dodge Brothers Company on the ground floor of The Boydell Building at 132-137 Beaubien Street and Lafayette Avenue. They began their enterprise as builders of special machinery and high-speed pleasure craft, but the manufacture of automobile parts and components soon took precedence.

A Detroit Free Press Sunday feature article dated September 1, 1901, proclaimed in its headline "Dodge Brothers Open One of the Most Complete and Modern Machine shops in Michigan. Everything is New and Up-To-Date."

The Free Press staff writer wrote a glowing description of the factory: "The typical machine shop of the age is dimly lit and litter-obstructed. In contrast, the Dodge Brothers machine shop has an orderly appearance with a thoughtful arrangement of machines to facilitate production and minimize the handling of machine parts, with the greatest ease and rapidity at a fraction of the expense and time employed in the days when hand labor dominated manufacturing [sic]. Machines of the latest design are used intelligently operated by the highly skilled labor force. Their reputation for quality is unequaled."

The Dodge brothers' machine shop soon became busy making precision automobile parts and sub-assemblies like chassis, axles, transmissions, clutches, and complete engines. In 1902, the Dodge brothers signed a major contact with Ransom E. Olds to produce quality transmissions for his Oldsmobile line. Much to Mr. Olds' chagrin, the contract was not renewed the following year because Henry Ford contracted with the Dodge brothers to exclusively build complete engines and other automobile components in 1903.

The Dodge brothers agreed to supply 650 Model A engines, transmissions, and axles at $250 each. The added business soon outgrew their shop's floor space, so they built a larger two-story building at Hastings and Monroe Streets in 1906. That space today is the Greektown Casino Hotel parking structure.

By 1908, they outgrew the Hastings Street facility and began building their own modern factory complex in Hamtramck, Michigan, on sixty-seven acres of vacant land on Joseph Campau Avenue where property taxes were cheaper than in Detroit.

The four-story, four-building complex contained an extensive machine shop, a power plant, a forging plant, and company headquarters, all with plenty of natural light and ventilation from steel-framed windows. Everything was well-organized in a thoughtful, systematic way. The plant came equipped with four cafeterias, male and female restrooms with separate lounges in each, and a well-equipped clinic and first aid center.

***

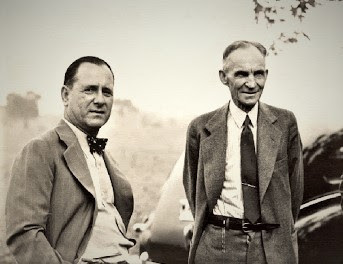

Henry Ford

Henry FordIn the beginning, very little of the original Ford Motor Company cars were actually manufactured by Ford, including the bodies, powertrains, and chassis. FoMoCo was essentially an assembly business which subcontracted much of its mechanical work to independent machine and tool & die shops around the Detroit area.

The Dodge brothers became Ford stockholders when they each bought 50 shares in 1902. They paid $3,000 cash and pledged $7,000 worth of Dodge manfactured car parts to help Ford get his fledgling company on its feet.

It was not long after that when Henry Ford realized what he had done when he signed over 10% of his company's stock to them. The Dodge brothers were double-dipping. On the front end, they made money selling automobile components and parts to Ford, and on the back end, they drew handsome dividend checks based on FoMoCo profits.

In 1905, Ford began producing his own engines and transmissions in a move towards self-sufficiency. In 1910 when Ford sold his Piquette Plant and moved into his newly built Highland Park Plant [the largest auto plant in the world at that time] the Dodges realized it was not in their best interests to remain tied to Henry Ford.

In August of 1913, John Dodge resigned as Ford vice-president, but the brothers remained on the board of directors. The Dodge brothers announced they would quit supplying parts to FoMoCo, so they could begin producing their own cars. They retained their Ford stock and counted on their million-dollar yearly dividend to help finance their rival operation.

Henry Ford felt betrayed and vindictive. The embittered industrialist began to squeeze the Dodge brothers and Ford's half-dozen other minority stockholders out of their dividends. He wanted to exercise full control of his company without stockholder interference.

To make it more difficult for the Dodge brothers to attract and retain workers for their new automobile plant, Henry Ford and his vice-president James Couzens announced on January 5, 1914, that FoMoCo would double wages for their assembly-line workers to five dollars a day.

The move was touted in the national newspapers as a way for Henry Ford to stabilize the chronic absenteeism and high 300% turnover rate of his workforce with a more dependable worker. Paying out higher wages also made it possible for many Ford employees to buy a car on credit for the first time, a car they had a hand in making.

Consequently, sales and productivity surged. Soon, with efficiency refinements in the assembly line and speeding up the line, the time to produce a Model T dropped from 12.5 hours to 93 minutes. FoMoCo doubled its profits in less than two years. Henceforth, Henry Ford was portrayed as the industrial Moses who led his people into the consumer-driven, blue collar middle class.

But the Dodge brothers and the Wall Street Journal criticized Ford's five-dollar-a-day plan as a stratagem to discourage workers from looking for work at their new Dodge plant where they paid only three-dollars a day.

Thousands of people came from all over the United States to find work at the Highland Park Ford plant and job riots broke out. Ford Security turned waterhoses on the crowd in bitter cold January weather. FoMoCo was compelled to announce they would hire only workers who lived within the Detroit city limits.

There were other strings attached to the higher wages, like sobriety which was monitored by the Ford Sociological Department. Rather than deprive the Dodge brothers of employees, the result of Ford's plan left the brothers with their choice of the most qualified people from all over the country.

The next scheme Henry Ford devised to squeeze the Dodge brothers out of his company was offering everyone who bought a Model T in 1914 a $50 rebate check, thus denying the Dodge brothers and the other minority investors millions of dollars of dividends.

Once again, Henry Ford looked like the Rainmaker to the public. John Dodge was still on the board of directors and was outspoken in his opposition to Ford's blantant disregard for shareholders' rights which cost them millions of dollars in lost dividends.

To further anger the minority stockholders, Henry Ford announced in August of 1916, that rather than pay out dividends to shareholders, he planned to shut down Model T production to expand his manufacturing capablity and develop a whole new automobile. This move adversely affected Ford dealers nationwide as well as workers and stockholders.

The Dodge brothers knew what was going on. Ford could not stand anyone stealing his thunder, and the positive media attention the Dodge brothers plant was receiving in the national and international press stuck in Ford's craw. Henry Ford wanted to be the only Golden Boy in Detroit.

Ford wanted to quietly break ground on an industrial complex along the banks of the Rouge River on a scale the world had never seen. Something that would impress even the most discriminating pharaoh of ancient Egypt, an industrial complex that takes in raw materials at one end and converts them into finished automobiles at the other. Ford's vindictive mind reasoned that turnaround was fair play. FoMoCo helped finance the Dodge factory complex; it was only fitting that they help finance his vision.

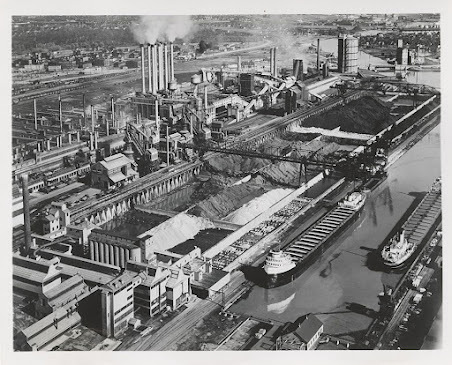

Henry Ford's Rouge Plant industrial complex

Henry Ford's Rouge Plant industrial complexFord purchased Dearborn farmland with his own money that was over a mile of Rouge River waterfront and a mile and a half wide. He announced that his Rouge project was a personal one. Ford incorporated a new company named Henry Ford and Son which would produce Fordson tractors. Henry Ford told the press that the Rouge River site would involve "no stockholders, no directors, no absentee owners, and no parasites." This was a direct swipe at the Dodge brothers.

When Ford announced his intention to build his own blast furnace and coke plant to make massive amounts of raw steel, the Dodge brothers knew the Ford tractor plant was destined to mass produce automobiles. The brothers refused to take that lying down.

On November 2, 1916, the Dodge brothers filed a law suit on behalf of the minority stockholders requesting that the FoMoCo pay out a minimum of 75% of its cash surplus to shareholders, amounting to over $39 million.

After more than two years working itself through the court system, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Dodge brothers' lawsuit. Ford was ordered to pay over $19 million to stockholders with $1.5 million in interest. The money hardly mattered to Henry Ford. As the majority stockholder, he owned 58.5% of FoMoCo stock. His payout was close to $12 million.

Henry Ford was determined to buy out his stockholders, so his company would be 100% family owned. While he and his wife Clara took an extended vacation in Southern California, his twenty-five-year-old son Edsel was entrusted with the task of buying out the minority stockholders.

The opening bid offered was $7,500 per share. The Dodge brothers knew the bid was undervalued. They negotiated for $12,500 per share. On their original investment of $10,000 in 1902, the brothers made $9.5 million in dividends and sold their Ford stock in 1919 for an additional $25 million, realizing a grand total of $34.5 million.

After the settlement was announced, members of the automobile press asked John Dodge for a statement. "Someday," he said, "people who own a Ford are going to want an automobile." In two short years from 1914 through 1916, the Dodge Model 30-35 touring car ranked second behind Ford in total sales.

A 1915 Dodge four-door sedan used by the United States Army.

A 1915 Dodge four-door sedan used by the United States Army.Dodge cars were clearly superior to Ford's Model T. They had solid all-steel bodies rather than sheet metal fastened to a wooden frame; the Dodge four-cylinder engine developed 35 hp, almost twice that of the Model T's 20 hp; the electrical system was 12 volt, compared to the Model T's 6 volt system; the Dodge car used a sliding-gear transmission, rather than the Model T's old-fashioned planetary transmission; and the stylish body came in a variety of colors, while the Model T came only in black.

By 1920, Henry Ford's protracted battle with the Dodge brothers and his heavy debt load financing the construction of the Rouge Plant left FoMoCo close to bankrupcy. Henry Ford had to borrow money to make his payroll.

But Ford's financial problems gave the Dodge brothers little comfort. While attending an automobile banquet in New York City, both brothers contacted the Spanish flu. John suffered for a week before dying at the age of fifty-six on January 15, 1920, at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel with his wife by his side.

Horace was also critically ill in a room down the hall from his brother, but he recovered in four days. Horace never recovered emotionally from the sudden death of his brother who had been his business partner all of their adlut lives.

Eleven months later while staying at this Florida home, Horace died of cirrhosis of the liver at the age of fifty-two, with his wife and son at his side on December 10, 1920.

In 1925, the Dodge widows sold their husbands' company to Dillon, Read & Company for $146 million to become the largest cash transaction in United States history, until 1928 when Walter Chrysler purchased the company for $170 million. He booasted to the automotive press that it was the smartest financial decision he ever made. Chrysler Motors now took its place among Detroit's Big Three automakers.

March 11, 2022

The Ford V-8 Gives G-Men Run For Their Money

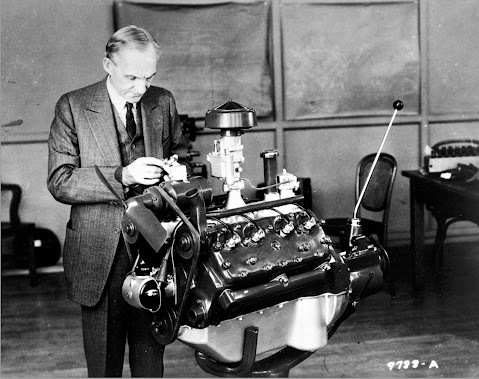

Henry Ford with his Miracle V-8 Engine--1932

Henry Ford with his Miracle V-8 Engine--1932Midway through the 1927 Model T year, Henry Ford announced he was shutting down operations in 25 of 36 Ford plants across the country to develop a new model to retain his company's hold on the low-priced market. The 1928 Model A was a big success with its new streamlined styling and a beefy, four-cylinder engine that performed favorably with Chevrolet's inline, six-cylinder. But Chevy's advertising slogan "A Six for the Price of a Four," captured the imagination of the car-buying public and Chevy was on pace to outsell Fords.

"If the public wants more cylinders, we'll build an eight-cylinder," Henry Ford told a group of hand-picked engineers. His goal was to produce an affordable V-8 engine for FoMoCo's low-cost line of cars. Ford did not invent the V-8 engine; in fact, Ford's Lincoln Division had offered them for years. But those engines were heavy, complex, and far too expensive for the low-priced market.

By casting the engine block in one piece of alloy steel, parts were eliminated and assembly was simplified. After much trial and error, FoMoCo offered its first Flathead [side valve] V-8 in February of 1932 as the successor to the Model A's four-cylinder engine. The 1932 Model 18 soon became known simply as the Ford V-8. The engineering of this innovative, affordable engine represented Henry Ford's last mechanical triumph for the company he founded. Ford was sixty-nine years old.

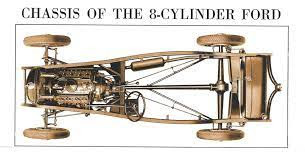

To accommodate the V-8's new engine dimensions, the Model 18 boasted a new frame with a wheelbase that was six inches longer than the Model A. The chassis for the Model A was simply two straight, steel rails. The Model 18 had an outward curved chassis with cross members welded-in for strength. The wider rear end gave the car more stability at high speeds which appealed to a specialized portion of the Ford V-8's fan base.

The Model 18's transmission was a manual, three-speed Sychromesh which greatly improved performance with a top speed of 65 mph in 1932. As improvements were made on the engine, horsepower climbed and speeds increased to 76 mph and beyond.

The Model 18 Ford V-8 came equipped with an electric fuel pump which allowed the gasoline tank to be positioned underneath the rear of the car for improved passenger safety. A high-pressure oil pump lubricated the internal workings of the engine. Rubber engine mounts reduced vibration and rubber weather stripping eliminated mechanical squeaks and rattles in the doors and the engine compartment.

1932 Model 18 Ford V-8

1932 Model 18 Ford V-8The Model 18 debuted in the Highland Park Ford Showroom on Woodward Avenue. Interest was high, but sales were slower than expected because of the Great Depression. Still the car sold a million in 1932 and the same number in 1933.

In 1934, Ford designer Joe Galamb updated the body of the Ford V-8 with a sweeping grill resembling a Medieval shield. The headlamps were built into the car's front end, rather than bolted to an old-fashioned headlamp bracket spread across the front of the car. The Ford V-8 was a brilliant performer winning road races and hill-climbing contests across the United States.

Restyled 1934 Ford V-8

Restyled 1934 Ford V-8The Ford V-8 became a favorite of bank robbers in the mid-1930s. John Dillinger broke out of jail in Crown Point, Indiana by whittling a piece of wood to look like a handgun. He used black shoe polish to disguise the phoney weapon and bluffed his way out of his cell. He then hijacked Sheriff Lillian Holley's new Ford V-8 parked outside of the jail and escaped. Two-months later on May 16, 1934, Public Enemy Number One John Dillinger allegedly wrote Henry Ford:

Hello Old Pal,

Arrived here at 10:00 am today. Would like to drop in and see you. You have a wonderful car. Been driving it for three weeks. It's a treat to drive one. Your slogan should be, drive a Ford and watch all other cars fall behind you. I can make any other car take a Ford's dust.

Bye-Bye,

John Dillinger

The provenance of the letter has never been established. Ford turned the letter over to the FBI, but they determined it was fake. Six weeks after the letter was received, John Dillinger was gunned down by G-Men in front of a Chicago movie theater on July 22, 1934, so the letter can never be properly authenticated.

Seventy-five years later, another Dillinger letter was found in Henry Ford's FBI file after a Freedom of Information search. This letter was dated May 6, 1934, at 7:00 pm.

Dear Mr. Ford,

I want to thank you for building the Ford V-8 as fast and sturdy a car as you did; otherwise, I would not have gotten away from the coppers in that Wisconsin, Minnesota case.

Yours till I have the pleasure of seeing you,

John Dillinger

This letter is believed to have more validity than the other letter Henry Ford leaked to the press. That letter was probably penned by some company adman. It is thought by Ford historians that because of the reference to escaping from the police, this rediscovered letter was not publicly acknowledged by FoMoCo.

Police departments all over the United States represented Ford's largest buyers of fleet vehicles, so Henry Ford, rather than risk angering law enforcement, turned the original letter over to the FBI where it languished for three-quarters of a century. That letter, though barely legible, is thought to be legitimate.

That was not the first endorsement Henry Ford's V8 received from gangsters. A month before the Dillinger letter was written, Clyde Barrow of Bonnie and Clyde fame wrote Ford on April 10, 1934.

"While I have still got breath in my lungs I will tell you what a dandy car you make. I have drove Fords exclusively when I could get away with one. For sustained speed and freedon from trouble the Ford has even other car skinned and even if my business hasen't been strickly legal it don't hurt enything to tell you what a fine car you got in the V8."

"While I have still got breath in my lungs I will tell you what a dandy car you make. I have drove Fords exclusively when I could get away with one. For sustained speed and freedon from trouble the Ford has even other car skinned and even if my business hasen't been strickly legal it don't hurt enything to tell you what a fine car you got in the V8."Handwriting analysts question the authenticity of the letter. Some believe Bonnie may have written the letter for Clyde; others believe it was the brainchild of the Ford publicity machine. Forty days after the letter was dated, Bonnie and Clyde were shot dead by a posse of Texas Rangers and local police on a county road in Bienville Parish, Louisiana, on May 23, 1934.

The stolen 1934 Ford V-8 Deluxe Sedan was riddled by 112 armor-piercing bullets. The coroner's report indicated 17 entrance wounds in Clyde Barrow and 26 in Bonnie Parker. When the car was returned to its rightful owner, it immediately began to tour the country as a notorious attraction at county fairs and carnivals.

Bonnie and Clyde Death Car

Bonnie and Clyde Death CarAt least half a dozen fake death cars also toured the United States. The authenticated Bonnie and Clyde death car has the car's original registration number stamped three times on the car--the engine, the transmission, and the frame.

The original car is usually housed behind plexiglass at Whiskey Pete's Hotel and Casino in Primm, Nevada, but as of January 2022, it is part of an exhibit on loan to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Museum in Simi Valley, California.

February 26, 2022

The Ukrainian Holodomor (Hunger-Extermination) of 1932-1933

Chicago American - Monday, February 25th, 1934Not widely known by many Americans, the

Holodomor

was the premeditated mass starvation of the Ukrainian peasantry in the name of Soviet collectivization of Ukraine's farmland in 1932-1933. Recent international human rights research estimates the number of dead at somewhere between 2.4 and 7.5 million victims. It is impossible to arrive at an accurate figure. But there is one thing that scholars agree upon, this was the worst peacetime catastrophe in Ukraine's long and fabled history. The loss of life rivals the Holocaust of European Jews by Adolph Hitler and the Nazis.

Chicago American - Monday, February 25th, 1934Not widely known by many Americans, the

Holodomor

was the premeditated mass starvation of the Ukrainian peasantry in the name of Soviet collectivization of Ukraine's farmland in 1932-1933. Recent international human rights research estimates the number of dead at somewhere between 2.4 and 7.5 million victims. It is impossible to arrive at an accurate figure. But there is one thing that scholars agree upon, this was the worst peacetime catastrophe in Ukraine's long and fabled history. The loss of life rivals the Holocaust of European Jews by Adolph Hitler and the Nazis.Since 2006, the Holodomor has been recognized by many countries as genocide of the Ukrainian people. History notes that the destruction of the Ukrainian peasantry was premeditated on the part of Joseph Stalin. The term Holomodor emphasizes the man-made causes of the famine, like the Soviet confiscation of private property, farmland, livestock, wheat crops, and all the implements of farm and industrial production.

A campaign of terror was unleashed on ethnic Ukrainians, primarily in the southeastern "breadbasket" region of the country. Those who resisted Soviet authorities were shot or deported to Siberia. Families who attempted to hide their grain stocks were killed. Even so, some families chose to burn their homes to the ground and kill their livestock rather than hand them over to their Soviet overlords.

A campaign of terror was unleashed on ethnic Ukrainians, primarily in the southeastern "breadbasket" region of the country. Those who resisted Soviet authorities were shot or deported to Siberia. Families who attempted to hide their grain stocks were killed. Even so, some families chose to burn their homes to the ground and kill their livestock rather than hand them over to their Soviet overlords. A system of internal passports was instituted preventing the free movement of the Ukrainian populace from villages and towns to suppress widespread knowledge of what was occurring in Ukraine. When the news of the famine reached the West, the Ukrainian diaspora in Western Europe and the United States quickly raised relief funds and sent food supplies to Ukraine which were rejected at the border by Soviet authorities. As a result of growing international notice, the Soviets responded by banning all journalists in Ukraine, and among the Ukraine populace, the banning of the words "famine" and "hunger." Using either word could result in a jail term.

With the exception of grain reserves used to feed livestock and not people, the vast bulk of Ukrainian grain was exported to neighboring countries to generate revenue for fueling Stalin's Five Year Plan. The Soviet Union was able to purchase Western commodities, among them military weapons and hardware. In return, those countries turned a blind eye to the Soviet Union's internal problems.

In addition to Ukrainian farm peasants, more than 5,000 Ukrainian intellectuals were arrested and charged with plotting an armed rebellion. Those who were not summarily shot were deported to Siberian labor camps, never to be heard from again. It is believed that Stalin feared a general revolt in support of Ukrainian nationalism. The Soviet goal was to have Ukrainians abandon all nationalistic fervor. This preemptive move left the rest of the population without leadership or direction.

For more detailed information on Holodomor , visit the United Human Rights Council's site at:

http://www.unitedhumanrights.org/genocide/ukraine_famine.htm

To view the many monuments dedicated to the victims of Holodomor , tap on this link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holodomor#mediaviewer/File:Holodomormemorialbloomingdale.jpg

February 24, 2022

Ford Model A Replaces Tin Lizzie

Henry Ford posing with a Model T

Henry Ford posing with a Model TFrom the mid 1910s through the early 1920s, the Ford Model T dominated the American car market. As the history books note, "Henry Ford put America on wheels." But over the car's eighteen-year run, cities began to pave the roadways and consumers wanted modern, comfortable, and fancier cars. The Tin Lizzie fell out of favor.

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, used Model Ts sold for five to ten dollars because they were obsolete and nobody wanted them. Bootleggers used them to smuggle liquor across the frozen Detroit River because it was no great loss if they went through the ice.

A "flivver" as they were called during Prohibition.

A "flivver" as they were called during Prohibition.By the mid 1920s, General Motors upgraded their manufacturing techniques and began to offer more powerful engines like a V-6, sleek styling, convenient driver controls, various colors, and some amenities as standard equipment like headlamps. When GM came out with an electric starter, while the Model T still had a crank and magneto, Chevy sales in particular cut deep into Model T sales.

Henry Ford resisted most efforts to upgrade the appearance of his Model T during its model run from 1908 until 1927, but his engineers continued to make improvements on the powertrain. Ford's son Edsel, president of FoMoCo in name only, tried to convince his father that the car market was evolving and people wanted something more stylish with better performance. Marketplace realities finally convinced Henry Ford that a new model was necessary.

After months of secret planning, on May 2, 1927, Henry Ford telegraphed his dealers nationwide that he was starting production of a totally modern car of "superior design and performance to any now in the low-priced field."

He announced to the press that he would be closing his factories and halting production to manfacture a new model which he and his son were sure would be "the next big thing." This was in mid 1927 which allowed Chevy to outsell Ford for the first time, though it was a false comparison. Ford stopped production on the Model T halfway through the year.

The elder Ford oversaw the mechanical engineering leaving Edsel to work with a design team on body styling. This was the first and last time that father and son worked together on the same project.

Henry decided to name the secret car the Model A, which showed a lack of imagination and marketing savvy. It was redundant. In 1903, his first commercial product was also named the Model A, but because this new car was totally re-engineered and redesigned, he chose to begin all over again with the Model A designation. Not a single component of the Model T was used in the construction of the new Model A.

Original 1903 Model A also known as the Fordmobile. This was Henry Ford's first production car.

Original 1903 Model A also known as the Fordmobile. This was Henry Ford's first production car.Mechanically, the reincarnated Model A was the first Ford to use the standard set of driver controls common in more modern cars which included a clutch, brake, and gas pedal on the floorboard. The Model T controls were antiquated and awkward by comparison. The standard Model A came equipped with four-wheel hydraulic shock absorbers, four-wheel mechanical brakes, and a new L-head inline four-cylinder, 40 hp engine with a top speed of 65 mph. Rather than a Model T two-speed transmission, this new car had a three-speed, manual transmission which greatly improved performance.

Restored Model A [notice retrofit turn signals]

Restored Model A [notice retrofit turn signals]In addition to a shatterproof laminated windshield, the exterior of the new Model A was lower and sleeker than the Model T. This was the first Ford to carry the iconic blue oval logo. The Model A was available in many different body styles including coupes, a cabriolet convertible, various sedans, phaetons, a station wagon, a police model, a taxi, and a pickup truck. Rather than the body being available in just black, the original Model A also came in Niagra Blue, Arabian Sand, Dawn Grey, or Gun Metal Blue.

The 1928 Model A was officially introduced on December 2, 1927, immediately becoming a big hit with the public giving Chevrolet a run for its money. In its four-year production life, 4,858,644 Model As were built. That is a healthy number considering the Great Depression was raging at the time. Because of the car's popularity then and now, the Model A is considered by many car buffs to be the best classic American car ever made.

February 15, 2022

General Motors' Rocky Start

William C. Durant

William C. DurantIn 1904, William C. "Billy" Durant, owner of America's largest horse-drawn wagon manufacturer Durant-Dort Carriage Company, bought the ailing Buick Motor Car Company from a Flint, Michgan businessman. Durant was not keen on the new horseless carriage craze, but having an eye on the future, he knew automobilies were the future of personal transportation. Durant partnered up with Charles Steward Mott and Frederic L. Smith to create General Motors (GM) on September 16, 1908.

Durant already owned Buick which became the first nameplate in the new corporation's stable with Oldsmobile soon to follow later that year. In 1909 with the corporation's profits and line-of-credit, Durant bought Cadillac and Oakland [which later became Pontiac Motors]. Durant continued on a spending spree and acquired four other fledgling automakers and a truck company. Durant even considered buying GM's archrival Ford Motor Company, but he fell two million dollars short on the funding.

By 1910, GM was struggling. The country was in a period of recession from 1910 through 1911. The banks tightened up their lending policies and car sales dropped. Because Durant's aggressive expansion of GM left the corporation over-leveraged and vulnerable to bankrupcy, stockholders voted Durant out of the chairmanship, but he continued to hold a large share of GM stock.

In 1911, Durant lured popular Swiss racecar driver Louis Chevrolet away from GM for whom he raced Buicks. Durant wanted to capitalize upon Chevrolet's international fame, and he knew that the automobile-buying public wanted to drive something glamorous and exciting. Durant sweetened the business offer for the racecar driver by naming the new company after him--the Chevrolet Motor Company. Durant merged three small automobile manufacturers, Little Motor Company, Mason Motors, and Republic Motor Company to form the new company.

Louis Chevrolet

Louis ChevroletTwo years into the partnership, the two men battled over design issues and the direction the company was taking. Chevrolet wanted to design a car for the high-end market while Durant wanted to produce an affordable car for the low-end market to compete with Henry Ford's obsolete Model T. Chevrolet chose to return to racing and sold his stock to Durant in 1913.

The dissolution agreement allowed Durant to continue using Chevrolet's name for the car's nameplate. If the gear-jammer had any business sense, he would have negotiated a licensing agreement to use his name. The Chevrolet heirs would still be earning royalties if he had. The following year, Chevys were branded with its modified Swiss Cross bowtie logo.

Original Chevrolet Bowtie Branding

Original Chevrolet Bowtie BrandingBilly Durant offered a four-cylinder engine in 1912 which outperformed Ford's four-cylinder in every way and came with a magneto starter rather than a crank. Women especially appreciated that. The car had cutting-edge styling and came in grey, green, blue, or red. The Chevy, as it was soon called, was an instant success cutting into Ford's low-priced market. Chevys were a little more expensive, but consumers were willing to pay a little more to be seen in a snappy-looking car.

1913 Chevy Model

1913 Chevy ModelDurant wisely used the profits he made from Chevy to buy GM stock. The Chevrolet quickly became so popular with the public that Durant offered GM a five-for-one stock trade in a reverse merger. On May 2, 1918, Durant regained controlling interest of GM as the corporation's largest stockholder. Billy Durant was back in the driver's seat as corporation president. He brought Chevrolet into GM's product line in 1919, as well as Fisher Body and Frigidaire.

As co-owner of Frigidaire, Durant essentially sold his company to himself as president of GM, an example of financial sleight of hand and a clear conflict of interest. The corporation was once again debt-heavy and flirting with bankrupcy.

In the background, Pierre S. DuPont and his family-owned chemical company had opened a line of credit with Wall Street financier J.P. Morgan. By 1919, DuPont invested 50 million dollars in GM stock. The following year, DuPont and the board of directors forced Durant out of GM for the last time because of his reckless speculation and dubious management ability.

Pierre S. DuPont

Pierre S. DuPontGM was the largest consumer of DuPont automotive finishes and artificial leather [vinyl] fabrics. GM's possible failure would hurt DuPont Chemical's business interests. Pierre S. DuPont stepped up and paid off Durant's debt to buy him out.

Alfred Pritchard Sloan

Alfred Pritchard SloanAlfred P. Sloan was elected president in 1923 to reorganize and manage the sprawling corporation. Under Sloan's management, GM established annual model changes which ushered in the age of planned obsolescence creating a vigorous used car market.

To prevent GM brands from competing with themselves, a pricing structure was established with Chevrolet as their most affordable brand followed by Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick, and their luxury brand Cadillac. As soon as buyers could afford a more expensive car, GM had an upgrade ready for them which inspired customer loyalty.

To help car buyers finance a new car or buy more car than they could otherwise afford, GM formed the General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC) which introduced consumer installment credit ensuring the company's long-term financial success. When the stock market crashed on October 29, 1929, ushering in the Great Depression, GM was well-positioned to survive it.

January 31, 2022

The Mustang Gallops into Automotive History

New York World's Fair Mustang Introduction.

New York World's Fair Mustang Introduction.The recession of the late 1950s hit Detroit especially hard. Money was tight and car sales fell for the Big Three [General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler]. Factories were struggling to keep their workers employed and their plants open. In response to that, Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo) reorganized their corporation and formed an Automotive Assembly Division promoting middle-management marketing man Lee Iacocca to head the division.

Lee Iacocca's challenges were many, but his goals were well-defined. He championed shifting production to smaller, fuel efficient cars and dressing them up to enhance their appeal to an economy-minded market. His first success was the Falcon Futura. The car was stylish, comfortable, and economical. Afterall, gas averaged thirty-one cents a gallon in 1961.

Iacocca formed a secret Fairlane Committee to come up with a new car concept unlike anything else on the market. FoMoCo needed a dynamic new car to capture a greater share of the youth market.

Their market research in 1961 indicated that a tidal wave of teenaged Baby Boomers [post World War II babies] were coming of age soon and itching to get behind the wheel of a sporty-looking car they could afford. By 1965, 40% of the United States population would be under 20 years old. By 1970, half of Americans would be under 25 years old. FoMoCo wanted to tap into that market. The Edsel's 1958 introduction with Edsel Ford's three sons.

The Edsel's 1958 introduction with Edsel Ford's three sons.The wounds from the Edsel debacle were still fresh at FoMoCo leading to a company shakeup. Iacocca knew the Edsel was advertised as the Car of the Future, but it was a product in search of a market it never found. Here was a market in search of a product. FoMoCo tailored their new product for this new market.

Since the original 1955 two-seater Thunderbird was reborn as a four-seater, suburban luxury car in 1958, FoMoCo received lots of mail asking for another two-seater. But Ford's market research indicated a two-seater did not have the mass appeal they were looking for. That market was limited to a mere 100,000 units.

The parameters for their new concept car required it to be sporty but capable of seating four passengers; it had to be lightweight, under 2,500 pounds; and it had to be inexpensive, no more than $2,500 with special equipment included as part of their standard model to sweeten the deal.

Helping to cut engineering and production costs, the chassis and the power train of the Ford Falcon were chosen. What this car needed was a new skin. Iacocca initiated a competition among seven designers to come up with clay mockups of the exterior design fit to specific platform specifications.

On August 15, 1962, Henry Ford II picked the model he liked best by saying "That's it!" The winning model was designed by Dave Ash, assistant to Joe Oros, FoMoCo's Design Studio head. In profile, the car had a long hood, a swept-back cabin, and a short deck [trunk].

Car designers want to see their vision transformed into sleek sculpted steel, but automotive engineers have to figure how to put the actual car together and make it work. Once the model was approved, the battle between the designers and the engineers began in what they called "the battles of the inch."

First was the battle of the radiator cap that would not fit under the stylist's low hood. The solution was to raise the hood a quarter inch and the engineers counter-sunk the cap.

Next, the stylists designed the back bumper to fit flush with the rear quarter panels for a clean look. The engineers wanted to simply bolt the bumper with brackets onto the back of the car like they had always done. The designers won that battle.

The last disagreement was between Henry Ford II and Lee Iacocca over leg-room for the rear seats. Ford was a large man who wanted an extra inch. Iacocca argued that it would spoil the lines of the car. Ford won that battle.

Next, the car needed a name. Hundreds of names were whittled down to several finalists including Colt, Bronco, Mustang, Puma, Cougar, and Cheetah. Cougar was the front runner until Mr. Ford became embroiled in a messy divorce, and the publicity department was afraid the name Cougar might cause some unnecessary notority or embarassment for their boss.

At the same time, the name Mustang did well in their market research. The name was felt to embody the spirit of the wide open spaces and recalled the famous World War II fighter plane. Once the name was decided upon, the Mustang's signature galloping horse front grill was designed.

What has become one of the most iconic and famous emblems in automobile history was criticized early on by a reporter at a FoMoCo press conference. His observation was that the horse was running in the wrong direction. Obviously, the reporter spent too much time at the track where the ponies only run counter-clockwise. Iacocco's wise reply was "Wild horses run anywhere they damn well please."

The Mustang was introduced in Ford showrooms on April 17, 1964. It came as a two-door coupe or convertible. Five months later, a three-door hatchback was introduced. The Mustang came with a three-speed syncromesh automatic transmission or a four speed manual, four-on-the-floor. At first, there were two, straight-six engine choices available, with V-6 and V-8 options offered later in the Mustang's run. The basic car was equipped with front disk brakes, all for the low sticker price of $2,368.

Iacocca gave free rein to his marketing expertise and saturated the media with Mustang ads like no product had before. FoMoCo ran glossy ads in national magazines with stories about their youth-oriented car, and 420 local television stations were sent footage of the car for their feature stories.

Radio DJs were given Mustangs to test drive and plug over their airwaves. In Detroit, radio jocks were allowed to put the Mustang through its paces on Ford's test track in Dearborn, Michigan. Images of the Mustang appeared on 15,500 outdoor billboards nationwide and the car was displayed in the lobby of Holiday Inn motels and other high traffic venues like airport terminals in twelve major United States cities.

The evening before the car's debut, FoMoCo bought simultaneous time on all three major television networks from 9:30 to 10:00 pm. Twenty-eight million viewers of Perry Mason [CBS], Hazel [NBC], and Jimmy Dean [ABC] were wowed with Mustang advertising.

Forty-four college newspaper editors were given the use of Mustangs to show off on their campuses for the spring term. No stone was left unturned to generate interest. As a final touch, Hayden Fry, football coach of the Southern Methodist University Mustangs, received a blue and red [school colors] Mustang as part of the car's debut launch.

After the Mustang's meteoric rise in the marketplace, Time and Newsweek featured simultaneous cover stories on the Mustang that Iacocca said led to the sale of an extra 100,000 units. By December of 1964, the Mustang had "the most successful new car launch ever introduced by the auto industry," reported Frank Zimmerman, Ford marketing chief.

At first, FoMoCo planned to produce only 100,000 Mustangs using only a portion of the Dearborn Assembly Plant. Before the car went to market, it was clear that demand was going to be greater than anticipated, so the whole plant was changed over to exclusive "Pony Car" production. Soon, another Ford plant in San Jose, California went online to boost yearly capacity to 360,000 cars.

In 1965, a third Ford plant in Metuchen, New Jersey was added to boost output to 440,000 cars prompting FoMoCo Assistant General Manager Don Frey to credit the Mustang's success on unprecedented market penetration. The Mustang is the only Ford nameplate that has been in continuous production since its introduction.

January 22, 2022

Henry Ford II vs. Harry Bennett and Lee Iacocca

Ford World Headquarters [the Glasshouse] in Dearborn, Michigan.

Ford World Headquarters [the Glasshouse] in Dearborn, Michigan.After Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo) president Edsel Ford died at the age of forty-nine from stomach cancer, his eighty-year-old father Henry reinstalled himself as company president. Despite surviving two strokes, the elder Ford was not comfortable with retirement or handing his company over to a successor.

With the help of FoMoCo's security and personnel director, Rasputin-like Harry Bennett, Henry Ford was able to maintain his weakened grip on the company that bore his name. Bennett was Henry's eyes and ears in the sprawling FoMoCo industrial complex. In the Medieval world, Bennett would have carried the title of Regent as he tried to maneuver himself into the top spot.

Although Harry Bennett never exercised any real administrative power at the company, other than that delegated to him personally by Henry Ford, now he was Ford's right hand man who took advantage of his declining and infirm boss to assume powers never delegated to him.

This disturbed Henry's wife Clara and his daughter-in-law Eleanor, Edsel's widow, who feared a power play to wrestle the company away from the family at Henry's death. Clara and Eleanor believed Bennett helped destroy Edsel's health from constant torment, and Eleanor vowed she would not allow him to rob her son, Henry Ford II, of his birth right. Both women and all of Edsel's children held Bennett beneath contempt.

Late in July 1943, Henry Ford II was released from the United States Navy by President Franklin Roosevelt. He was made executive vice-president of the company on August 10, 1943. Harry Bennett and Henry Ford II begrudgingly co-existed until Eleanor gave her father-in-law an utimatum. Retire and install her eldest son as company president, or she would sell off her stock ending the family's total ownership of the corportation. The old man was befuddled and approaching death; he had no fight left in him. On September 21, 1945, FoMoCo's Board of Directors elected Henry Ford II as the company's third president.

Henry Ford II

Henry Ford IIThe twenty-eight-year-old, new Ford president's first priority was to sever Harry Bennett from the company. After a heated exchange between the two men in Bennett's basement office in the Ford Administrative Building, Bennett was told to clean out his desk because his services were no longer required. The fifty-three-year-old pretender to the Ford throne retorted, "You're taking over a billion-dollar organization that you haven't contributed a goddamned thing to!" Bennett spent the rest of the afternoon burning his personal files before he left.

To avoid a protacted and ugly legal battle, Bennett was given a "no-show" position with the company at a nominal salary for eighteen months until he could get his thirty years in with the company. Then, he drew the standard retirement benefit of $424 per month. Upon leaving FoMoCo, Bennett remarked to the press, "I feel like I'm getting out of prison." Nobody felt sorry for him.

***

The inexperienced grandson of the company's founder brought in his brothers Benson and William Clay to help with the management of the world's largest industrial giant. To make their imprint on the company and impress the auto industry, the Ford brothers set their designers, engineers, and marketing men to the task of developing the car of the future with a nameplate to honor their late father called the Edsel.

In death as in life, Edsel Ford could not get a break. His name became synonymous with epic automotive failure. After that public humiliation, it was clear to Henry Ford II that the company needed reorganization.

In a November 11, 1960 press conference at FoMoCo's World Headquarters [the Glass House], Henry, the Second, now known informally as "the Deuce," announced that his company would undergo a reorganization. He was going to step down as president after only fifteen years holding that position and installed himself as chairman of the company's board of directors, as his grandfather Henry had done when he brought his son Edsel in as president in 1919.

Forty-four-year-old Robert S. McNamara was introduced as the corporation's new president. This marked the first time a non-Ford family member held that position. McNamara announced the formation of a separate Automotive Assembly Division to oversee the seventeen domestic Ford plants spread over twelve states to streamline management and improve production.

Named to head the division as vice-president and general manager was Lee Anthony Iacocca from Allentown, Pennsylvania. Iacocca announced that FoMoCo would be introducing new, fuel efficient compact models to compete with foreign imports and Chevrolet's popular Corvair Monza. His first success was the two-door Falcon Futura with contoured bucket seats, a center console, and carpeting. The Futura was powered by a lightweight, aluminum-alloy, four cylinder engine.

Lee Anthony Iacocca

Lee Anthony IacoccaIacocca was a marketing and promotional expert. He pitched the Futura as the "compact cousin of the popular Thunderbird." Iacocca realized that to climb out of the industry-wide recession, FoMoCo needed to appeal to an emerging demographic--the female sector of young, independent women who were looking for a stylish, economical car that was easy to drive and park.

Ford dealers were worried about depreciation and the trade-in value of economy cars. It was no secret that dealers made more profit on their high-end models like the Thunderbird and the Lincoln Continental. One argument against the shift to a compact line of cars was salesmen felt the smaller cars downgraded their image to their customers, and the smaller cars were not big enough to hold their sample and sales kits.

Always the promoter, Iacocca contended that their full-sized, luxury models were still available for status-conscious consumers and reminded them that FoMoCo built its reputation and legacy by providing low-cost transportation to the masses.

On April 21, 1961, Iacocca announced the huge success of 20,000 advance dealer orders for the upgraded Falcon Futura. Second quarter production increased by 51% which outran the industry average of 26%. That translated to 145,000 units built during the second quarter. FoMoCo plants were working three shifts to keep pace with orders. Iacocca's star began to rise.

Not content with being a one-hit wonder, Iacocca introduced the Ford Fairlane on August 25, 1961, as a mid-sized, economy car offering. Like the Falcon line, the Fairlane quickly found its audience helping FoMoCo break sales records. Overall Ford sales in 1961 reached their highest point since the Model T in 1925.

In April of 1964, Iacocca introduced the car that would enshrine him in the annals of automobile history--the Mustang. This time Iacocca targeted the enormous market of Baby Boomers, children born after World War II, who were entering the new car market for the first time; multiple-car families, a quickly growing demographic; and the increasing ranks of young, professional women. This was the right product at the right time. Mustang sales set a record pace of 152,000 units in the first five months of production.

Interest in the Mustang was so keen that crowds of people were drawn to FoMoCo showrooms across the country. Many car buyers walked out with the a new 1964 Thunderbird, whose sales rose 65% over the previous year. The Mustang had coattails.

Iacocca was clearly Ford's Golden Boy. Both Time magazine and Newsweek used his image for their cover stories on the Mustang miracle. It took some time to rise above the ranks, but on December 10, 1970, the Deuce promoted Iacocca to company president.

Iacocca was a respected advertising man at heart who had no trouble talking before the press or pitching new ideas to his staff. His engineering team did preliminary planning and design work on two new products which Henry Ford II summarily shot down.

The relationship between him and Iacocca declined to the point that heated arguments broke out in the board room. Ford made it clear that it was his name on the building. On July 13, 1978, the Deuce dismissed Iacocca for the oblique reason that "sometimes you just don't like someone."

Iacocca was heavily courted by the Chrysler Corporation, which was struggling to survive for quite some time. They hired Iacocca as CEO [Chief Executive Officer] four months after he was fired from FoMoCo, making him the only man in history to lead two of Detroit's Big Three [GM, Ford, and Chrysler].

Iacocca lured several disgruntled Ford executives and engineers away from FoMoCo, along with his Mini-Max concept vehicle which the Deuce had rejected. It became reincarnated as the Dodge Caravan/Plymouth Voyager minivan which, along with the K-Car, saved Chrysler from bankrupcy, prompting the Deuce to remark, "Harry Bennett was the dirtiest, lousiest son-of-a-bitch I ever met in my life, except for Lee Iacocca." Nobody felt sorry for him.

January 7, 2022

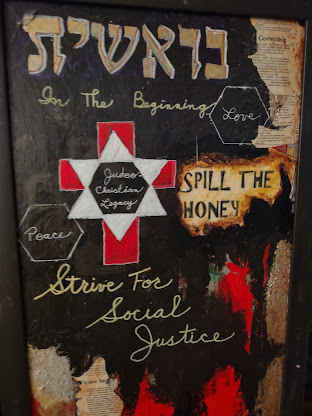

The Spill the Honey Foundation and the Paintings of DeVon Cunningham

The Spill the Honey Foundation is an alliance of Jewish Americans and African Americans dedicated to using the arts to promote human dignity by advancing public awareness of the European Holocaust and American slavery. In addition, the group draws attention to contemporary social injustices and systemic oppression to advance cultural tolerance. They strive to spread dignity, goodness, and kindness among all people in a cross-generational effort to improve the DNA of the soul by countering racism and antisemitism.

This non-profit organization takes its name from the inspirational story of Eli Ayalon, a teenaged survivor of the Nazis. Forty years after maintaining his self-enforced silence after World War II, Ayalon shared the story of how his mother told him the family was going to be separated from the Warsaw Ghetto in Poland and send east to the concentration camps. She knew they would never see each another again.

Young Ayalon was allowed by the Nazis to leave the ghetto and return because he ran errands for their German oppressors. “When you leave tomorrow,” his mother told him, “never return. Never! Struggle to survive.”

His mother gave him a small, gauze-covered cup with some honey in it. “Eli,” she said, “honey sweetens the sting of hate. Close your eyes to see beyond the pain and suffering to celebrate the sweetness of life. Spill the honey.”

From this painful memory between a mother and son, Eli Ayalon went from being a survivor to becoming a messenger of hope. The Spill the Honey Foundation was inspired by the Jewish wisdom of Elizer Ayalon and the civil rights movement of Dr. Martin Luther King.

***

DeVon Cunningham and me in his art studio. [11/11/2021]

DeVon Cunningham and me in his art studio. [11/11/2021]In 2018, the Spill the Honey Foundation under the direction of Dr. Sheri Rogers brought Detroit docuartist DeVon Cunningham on as art director to create a series of eighteen original paintings for display in each of the eighteen Holocaust museums nationwide.

The collection was scheduled originally for its debut at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit’s Cultural Center in 2020. But due to Covid restrictions, the debut exhibition was cancelled. Mr. Cunningham is working to reschedule the exhibition while the collection is still intact.

Many of Mr. Cunningham's Spill the Honeypaintings contain the melding of the Christian crucifix and the Hebrew Star of David to symbolize the underlying ties of both religious traditions. The Spill the Honey Foundation is a model to show how different communities can find common goals and work together.

The shape of the hexagon appears in several paintings as a unifying image linking the concept of the honeycomb, the bees, and the honey of the natural world to the goals of the Spill the Honey Foundation, which are to spread peace, harmony and justice, using college student ambassadors to bring the movement to young people.

Reconciling the inequities of history will not happen without bearing witness to the documented truths of the past—the good, the bad, and the ugly. I believe we owe future generations that much.

December 30, 2021

The Tragedy of Edsel Ford - Death by a Thousand Cuts

Edsel Ford

Edsel FordUnlike Edsel Ford's children, Edsel was not born in the lap of luxury. His father and mother, Henry and Clara, lived on the cusp of poverty while Henry invested every spare cent he could earn at the Edison Illumination Company in Detroit to develop his horseless carriage made of four bicycle wheels, a carriage frame, a tiller steering lever, an upholstered bench seat, and a two-cylinder, four horsepower, chain driven engine. He called his contraption the Quadricycle.

On June 4th, 1896 at the age of thirty-two, Henry Ford took the first of many test drives. Although he had no memory of it, his four-year-old son Edsel took his first ride in a self-powered vehicle. Ford quit his job at Edison in 1899 to focus on building automobiles and formed the Detroit Automobile Company. Two years later [1901], he formed the Henry Ford Company, and two years after that, he founded the Ford Motor Company [1903]. While Henry struggled to dominate the early automobile business, he and Clara lived in twelve different places before he had Fair Lane manor built in 1913 through 1915. Edsel was in his early twenties when the mansion was completed.

Ford's original quadricycle

Ford's original quadricycleAlthough his parents doted on him, Edsel's home life was anything but stable. As a child, Edsel went to a private grammar school in Connecticut and then attended Detroit University School, a local private college preparatory school. The family company was the most stability Edsel had in his young life. He grew up with the Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo) and would hang around the design and pattern shops on his school vacations where he became acquainted with master model-maker and Ford engineer Charles "Cast Iron Charlie" Sorensen. Sorensen, who over the course of his forty-year career with Henry Ford and his company, would become young Edsel's lifelong friend and mentor.

Rather than take the next step into a university education, Edsel made the decision to enter the family business at age eighteen. I'm sure his father prompted him to make this decision. Henry Ford was a no-nonsense, self-made man who was distrustful of university educated types. All of the early, key people in the company had come up the hard way like Ford did. But rather than break Edsel in on the grimy foundry floor or the assembly line, Ford sent his son to work in the business end of the operation in financing. Edsel never dressed less than sartorial [well-tailored]. His personal taste in clothing was impeccable in stark contrast to those he worked with, but his work ethic and integrity soon won over most people.

In 1915, James Couzens resigned as secretary/treasurer of FoMoCo in protest of Henry Ford's public, pacifist statements and pro-German sentiments while on a European "peace ship" mission. Edsel was the heir apparent and succeeded Couzens becoming the company's first finance director--a title made especially for Edsel. His father did not like titles for his excutives and preferred they be called simply "Ford Men." Henry Ford felt he could utilize and control them better if there was ambiguity in the management ranks.

The company's great chain of being had room for only one person at the top--Henry Ford. Despite that, Henry stepped aside in 1919, and Edsel became the president of the company while Henry remained on his company's board of directors. The elder Ford held over 50% of the company's stock. That was his trump card. With his son, Henry began a secret project which resulted in the development of a small block V-8 engine and the Model A, which saved the company from bankrupcy and the General Motors Corporation whose Chevrolet division was eating away at FoMoCo's dominance in the low priced market.

Here is where the plot thickens: A year after Edsel's management promotion, he married Eleanor Lowthian Clay [19], a socialite who was the niece of J.L. Hudson, the department store founder. The newlyweds did not want to live at the Fair Lane manor with Edsel's parents. The elder Fords were crestfallen. They had Fair Lane built especially with the thought of keeping Edsel under their wing. The manor was built near the banks of the Rouge River with a built-in swimming pool, a game room, a bowling alley, a billiards room, a boathouse, and a riding stable all designed with their son in mind.

According to Charles Sorensen in his autobiography My Forty Years with Ford, "Father and mother wanted to keep their only son close to them and guide his every thought.... Like all normal young people, Edsel wanted to be on his own to see and experience the world." Important people began to admire and respect the young executive which rankled his father who was jealous of anyone who seemed to wield influence with his son. "Henry Ford's greatest failure was expecting his son to be like him," Sorensen wrote. "Edsel's greatest victory, despite all obstacles, was in being himself."

The Edsel Fords made their first home in Detroit's Indian Village neighborhood on Iroquois Street where all four of their children were born: Henry II [1917], Benson [1919], Josephine [1923], and William Clay [1925]. In 1929, the Edsel Fords moved to Gaukler Point in Grosse Pointe with 3,000 feet of shoreline on Lake St. Clair and a walled-off, massive estate. Grosse Pointe was where wealthy and influential Detroiters lived, some residents with ties to Ford's arch competitor General Motors.

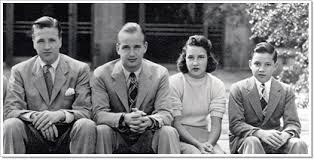

Henry II [the Deuce], Benson, Josephine, William Clay

Henry II [the Deuce], Benson, Josephine, William ClayThe Henry Fords were nonsmoking teetolalers who disapproved of rumors of Edsel's riotous living, like attending cocktail parties and joining a country club. Edsel was being surveilled by Harry Bennett's men. It was being reported that Edsel was being corrupted by alcohol. The Edsel Ford's always kept a fully stocked bar in their home, even during Prohibition. Henry was distrustful of Edsel's new friends in Grosse Pointe, but Edsel chose his own friends and adopted a modernist sensibility apart from the fundamentalism of his parents.

With the help of his wife Eleanor, Edsel educated himself in the arts and literature and became an art collector. In contrast, Henry Ford was raised a farm boy with a sixth grade, rural education who was fond of saying, "A Ford can take you anywhere, except into society." He was wrong. This was the beginning of a serious riff between Edsel and his father.

Henry Ford put his controversial henchman Harry Bennett on Edsel's neck to disabuse him of the notion that he was actually the president of FoMoCo. It was clear to everyone that Edsel wore the mantle, but his father was the power behind the throne. Edsel had the title but not the scepter that went with it. Sorensen noted that "Henry could not let go, and Edsel did not know how to take over."

Harry Bennett with Henry Ford

Harry Bennett with Henry FordEdsel always deferred to his father's edicts and allowed him to trample on his dignity, first with the company and later by tampering with the private lives of Edsel's family and inlaws, usually through the efforts of Harry Bennett. The elder Ford was primarily responsible for crushing his son's spirit. Ford believed his son was weak, and he blamed himself for overprotecting Edsel with the "cushion of advantage." For the sake of the company, Henry felt he needed to toughen the boy up.

Of his many transgressions against his son, the elder Ford found fault with anything Edsel wanted to do to make FoMoCo more competitive. Edsel wanted to modernize the company with college-educated executives, but Henry would not stand for that. He wanted his executives to start at the bottom and work themselves up the corporate ladder.

In 1919, Henry Ford bought the Dearborn Independent newspaper. At his personal direction, Ford instructed his editor William Cameron and his FoMoCo administrative assistant Ernest Liebold to begin a journalist rampage against the Jews and the International Banking Conspiracy. Edsel had many Jewish friends and implored his father to shut down his antisemitic screed. To compound matters, Henry Ford required his dealers to include a copy of the newspaper in every new vehicle sold resulting in lost sales. American Jews would not be caught dead buying a Ford car.

In 1922, many of the articles were compiled into a book called The International Jew, which sold well in the United States and found an enthusiastic audience in Germany. Thirty-three-year-old German militant Adolf Hitler kept a well-read, dog-eared copy of the book on his desk and had a signed photo of Henry Ford on the wall of his office. After losing a very public and expensive lawsuit, Henry Ford was forced to shut down the paper in 1927, but the damage had been done, much to the personal embarrassment of Edsel and Eleanor.

Another tramatic event for FoMoCo was the Battle of the Overpass on May 26, 1937 between underworld thugs hired by Harry Bennett and the United Auto Workers (UAW), who were distributing pro-union literature on the Miller Road pedestrian bridge leading into the Rouge Plant. Detroit News photographer James J. Kilpatrick, snapped a few quick photos and jumped into a waiting car to avoid a beating and a busted up camera. The photos appeared in the evening edition of the Detroit News, and by morning, it was picked up nationally and internationally.

Edsel was struggling with his health and wanted the company to settle the contract which had already been settled at General Motors and Chrysler Corporation. Henry Ford wanted to dig in and bust more heads. He gave Harry Bennett free reign and unlimited funds to break the UAW, which Ford believed was communist-inspired socialism. Clara Ford summoned Charles Sorensen to Fair Lane to ask, "Who is this [Harry] Bennett, that has so much control of my husband?" She did not like what she heard from Sorensen.

Clara Ford threatened her husband Henry with divorce and selling off her FoMoCo stock if a contract settlement was not reached immediately. That got the old man's attention, but Edsel was in no condition to negotiate, so in a stroke of twisted irony, Ford had Harry Bennett represent the company and settle the contract.

Clara Bryant Ford