Gregory A. Fournier's Blog, page 48

January 6, 2013

"The Rainy Day Murders" - Who Were the Victims?

Without a full confession and tangible corroborative evidence, it may never be proven that John Norman Collins was the killer of Mary Fleszar (19), Joan Elspeth Schell (20), Maralynn Skelton (16), Dawn Basom (13), Alice Kalom (23), or Roxie Ann Phillips (17) - the California victim from Milwaukie, Oregon.

Collins was only brought to trial for the strangulation murder of Karen Sue Beineman (18), which occurred on the afternoon of July 23, 1969. Three eyewitnesses were able to connect Collins and Beineman together on his flashy, blue Triumph motorcycle. Then an avalanche of circumstantial evidence buried John Norman Collins. The lack of a credible alibi also worked heavily against his favor with the jury.

Technically, the term "serial killer" does not legally apply to Collins. He was only convicted of one murder. It wasn't until 1976 that the term was first used in a court of law by FBI profiler, Robert Ressler, in the Son of Sam case in New York City.

When the Washtenaw County prosecutor, William Delhey, decided not to bring charges in the other cases, Collins was presumed guilty in the court of public opinion by most people familiar with the case.

Today, however, not everyone agrees because of the ambiguity that surrounds this case and the many unanswered questions. To prevent a mistrial in the 1970 Beineman case, prosecutors suppressed details and facts about the other unsolved killings.

There are many young people who believe Collins was railroaded for these crimes by overzealous law enforcement, and that he should be given the benefit of the doubt and released. That can happen only with a pardon by a sitting Michigan governor.

When the series of sex slayings stopped with the arrest of Collins for the murder of Karen Sue Beineman, everyone was relieved. Most certainly, other young women were murdered in Washtenaw County after Collins was arrested, but none with the same signature rage and psychopathic contempt for womanhood. These were clearly power and control murders.

The six other county murders of young women in the area from July of 1967 through July of 1969 were grouped together and considered a package deal. Law enforcement felt they had their man. The prevailing attitude of Washtenaw County officials was that enough time and money had been spent on this defendant.

DNA testing and a nationwide database was not available in the late Sixties. Even if it had, Collins would not have been screened because he would not have been in the database. He had never been arrested or convicted of any crime and had no juvenile record.

Still, in 2004, over thirty years since Collins was thought to have murdered University of Michigan graduate student, Jane Mixer, DNA evidence exonerated him and pointed the finger at Gary Earl Leiterman, a nurse in Ann Arbor at the time of Jane's murder. For some people, the Mixer case cast the shadow of doubt over Collins' alleged guilt in the remaining unsolved murders attributed to him.

***

When Edward Keyes and Earl James changed the names of the victims and their presumed assailant in their respective books on Collins, they left readers with a mishmash of twenty-three fictitious names. When Collins officially changed his last name in 1981 to Chapman, his Canadian birth father's last name, even people familiar with the case became confused. The end result was that the real identities of the victims and their assailant have been obscured over the years and all but forgotten by the public.

Using the real names of the victims, here is a micro-sketch of each of the remaining young women whose cases have yet to be solved but are considered open by the Michigan State Police. The Roxie Ann Phillips California case is the exception.

Roxie Ann Phillips Mary Fleszar (19) went missing on July 9, 1967, and was found a month later on August 7, 1967. She was not killed where her body was found. It had been moved several times and was unrecognizable. Mary taught herself to play guitar left handed and played for church services for several denominations on Eastern Michigan University's campus. People who knew her said she was very sweet and vulnerable.Joan Elspeth Schell (20) was seen hitchhiking and getting into a car with three young men in front of McKinney Student Union on EMU's campus. She was last seen with Collins just before midnight on June 30, 1968, by three eyewitnesses. Prosecutors felt this case was promising but never pursued it.Maralyn Skelton (16) was last seen on March 24, 1969, hitchhiking in front of Arborland shopping center. An unidentified witness said she got into a truck with two men. Of the seven presumed victims, Maralyn took the worst beating of the lot and then in death, suffered under the hands of the media.Dawn Basom (13), the youngest of the victims and a local Ypsi girl, was abducted while hurrying to get home before dark on April 16, 1969. Dawn was last seen walking down an isolated stretch of railroad track that borders the Huron River. She was less than 100 yards from her front porch. Police were able to discover where she had been murdered, not far from her home. Her body was found tossed on the shoulder of Vreeland Rd. in Superior Township. A fifteen mile, triangular drop zone was beginning to reveal itself to investigators.Alice Kalom (23) was the oldest victim long thought to be on her way to a dance on the evening of June 7, 1969. Two people report that she had a date with someone she had only recently met at a local restaurant, the Rubaiyat, in Ann Arbor. Another person said he saw her standing outside a Rexall Drug store that evening. Alice's body was found two days later, and it had the earmarks of the previous killings. Her murder site was discovered also - a sand and gravel pit north of Ypsilanti. Her body was deposited on Territorial Rd, furthest north of any of the victims. Police claimed they found evidence in the trunk of Collins' Oldsmobile Cutlass that linked Collins to Miss Kalom. This was another case the prosecution thought they might be able to win but never brought to trialRoxie Anne Phillips (17) was from Milwaukie, Oregon, visiting a family friend in California for the summer in exchange for babysitting services. On June 30, 1969, Roxie had the misfortune of crossing paths with John Norman Collins in Salinas, California, where Collins was "visiting." In many ways, the California case was the strongest of any of the cases against Collins. Extradition was held up so long in Michigan that Governor Ronald Reagan and the Monterey County prosecutor lost interest in the case and waived extradition proceedings. This remains a cold case. What links these murders are the mode of operation of the killer, the ritualized behavior present on the bodies of the young women, and the geoforensics of the body drop sites.

Roxie Ann Phillips Mary Fleszar (19) went missing on July 9, 1967, and was found a month later on August 7, 1967. She was not killed where her body was found. It had been moved several times and was unrecognizable. Mary taught herself to play guitar left handed and played for church services for several denominations on Eastern Michigan University's campus. People who knew her said she was very sweet and vulnerable.Joan Elspeth Schell (20) was seen hitchhiking and getting into a car with three young men in front of McKinney Student Union on EMU's campus. She was last seen with Collins just before midnight on June 30, 1968, by three eyewitnesses. Prosecutors felt this case was promising but never pursued it.Maralyn Skelton (16) was last seen on March 24, 1969, hitchhiking in front of Arborland shopping center. An unidentified witness said she got into a truck with two men. Of the seven presumed victims, Maralyn took the worst beating of the lot and then in death, suffered under the hands of the media.Dawn Basom (13), the youngest of the victims and a local Ypsi girl, was abducted while hurrying to get home before dark on April 16, 1969. Dawn was last seen walking down an isolated stretch of railroad track that borders the Huron River. She was less than 100 yards from her front porch. Police were able to discover where she had been murdered, not far from her home. Her body was found tossed on the shoulder of Vreeland Rd. in Superior Township. A fifteen mile, triangular drop zone was beginning to reveal itself to investigators.Alice Kalom (23) was the oldest victim long thought to be on her way to a dance on the evening of June 7, 1969. Two people report that she had a date with someone she had only recently met at a local restaurant, the Rubaiyat, in Ann Arbor. Another person said he saw her standing outside a Rexall Drug store that evening. Alice's body was found two days later, and it had the earmarks of the previous killings. Her murder site was discovered also - a sand and gravel pit north of Ypsilanti. Her body was deposited on Territorial Rd, furthest north of any of the victims. Police claimed they found evidence in the trunk of Collins' Oldsmobile Cutlass that linked Collins to Miss Kalom. This was another case the prosecution thought they might be able to win but never brought to trialRoxie Anne Phillips (17) was from Milwaukie, Oregon, visiting a family friend in California for the summer in exchange for babysitting services. On June 30, 1969, Roxie had the misfortune of crossing paths with John Norman Collins in Salinas, California, where Collins was "visiting." In many ways, the California case was the strongest of any of the cases against Collins. Extradition was held up so long in Michigan that Governor Ronald Reagan and the Monterey County prosecutor lost interest in the case and waived extradition proceedings. This remains a cold case. What links these murders are the mode of operation of the killer, the ritualized behavior present on the bodies of the young women, and the geoforensics of the body drop sites. At the time of the murders, investigators thought that the killer may have had an accomplice, but that idea was largely discredited by people close to the case. The two likeliest suspects were housemates with Collins. Both men were given polygraph lie detector tests and were also thoroughly interrogated by police detectives. Prosecutors were satisfied of their innocence or complicity in the murders.

But investigators did discover that both friends of Collins were involved with him in other crimes such as burglary, fencing stolen property (guns and jewelry), and motorcycle theft.

There was also a "fraud by conversion" charge brought against Collins and one of his friends for renting a seventeen foot long house trailer with a stolen check that bounced. They abandoned the trailer in Salinas, California. It is the suspected death site of Roxie Ann Phillips.

These guys were not Eagle Scouts, that's for certain. When the trailer was discovered, police found that it had been wiped clean of fingerprints inside and out. Both men returned to Ypsilanti two weeks earlier than they had planned, driving back in the 1968 Oldsmobile Cutlass that was registered to John's mother but had been in John's possession for months.

Back in the Sixties, police protocols and procedures for investigating multiple murders were not yet established. For two long years, an angry killer of young women was able to evade police, but slowly a profile was developing and police were closing in on the suspect from two different fronts. Washtenaw County's long nightmare was about to end.

Next post: Treading on the Grief of Others

Published on January 06, 2013 05:28

January 3, 2013

The John Norman Collins Mess and My Motivation For Writing About It

A small number of people have questioned my motives for writing In the Shadow of the Water Tower about John Norman Collins and the "Rainy Day Murders" as they were known in the late Sixties. Why reopen old wounds?

A small number of people have questioned my motives for writing In the Shadow of the Water Tower about John Norman Collins and the "Rainy Day Murders" as they were known in the late Sixties. Why reopen old wounds?The sex slaying murders of seven and possibly more local young woman created an atmosphere of sustained panic and mortal fear for college coeds on two college campuses, Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti and The University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

***

This tragedy left an indelible impression on me and anyone else who lived through that terrible period of Washtenaw County history. I first realized an arrest had been made in the "Coed Killer Case" when I was walking down from my apartment on College Place St. to have lunch at Roy's Grill, a diner on the corner of W. Cross and College Place. It was Friday, August 1, 1969, around 10:30 or so in the morning.

I lived only a block down the street and saw an assortment of four or five police cars surrounding the corner house on Emmet St. A small group of people had gathered across the street from the house; the police were keeping spectators away.

My first thought was that another girl's body had been found. A year before, Joan Schell, the second victim of a phantom local killer, had lived across the street from this very same Emmet St. house.

I approached someone I knew and asked him what was happening, "John Collins was arrested for the murder of that Beineman girl a week ago," he told me.

My friend had occasionally ridden motorcycles through the countryside with Collins, and now and then they "exchanged" motorcycle parts, so he knew him. When I asked how he got his information, he pointed to a guy in front of the cordoned off house who was arguing with policemen.

Arnie Davis lived across the landing from Collins on the second floor and described himself, during the court case, as Collins' "best friend." He wanted to get his stuff out of the house, but it had already been locked down as a potential crime scene.

I walked a scant block further to W. Cross St. and ate lunch at Roy's. When I walked up the street to go home, the crowd had grown and the media had arrived by this time. I have a vivid memory of reporters questioning by-standers.

When I saw Collins picture in the newspaper later in the day, I was able to place the name with the face. I realized that I had several negative brushes with this guy while I was a student at Eastern Michigan.

After learning of Collins arrest, my mother called me on the phone relieved. She reluctantly told me that she had suspected I might be the murderer because I resembled the eye-witness descriptions in the newspapers. Can you believe that? Thanks, Mom.

***

When The Michigan Murders came out in 1976, I snapped it up like so many other people in Ypsilanti and anxiously read it. I was disappointed because I felt the novelization of the story took liberties with the facts and relied too heavily on official reports and the work of an Eastern Michigan University English Professor, Dr. Paul McGlynn, who allowed Edward Keyes to use his notes which McGlynn had gathered while attending the court proceedings and doing research for his own book.

I soon discovered that too many assumptions and liberties were taken with the story, which made for smooth flowing fiction, but the real story is anything but smooth flowing. It is a ragged mess complicated by misinformation, shaky news reporting, and missing documentation. If this was an easy story to tell, it would have been done so in detail long ago.

The most frustrating and confusing aspect of Edward Keyes' novelization was that he chose to change the names of the victims and their alleged murderer. When another author took up the charge of this case some years later, he too changed the names of the victims and of the accused, and then referenced these names to the fictitious names which only compounded the confusion and led to the obscurity of the real victims.

Over forty-five years have passed since these sad events, and it is time for the record to be restored and updated. It may have been customary in the past for authors to change the names of victims to protect the families and their feelings, but those days are long gone. I would rather get the facts right than be polite.

Next post: Who Were the Victims and Why Should We Care?

Published on January 03, 2013 10:20

December 29, 2012

John Norman Collins Supporters on Kelly and Company - Monday, October 3, 1988

On Friday, October 1, 1988, Marilyn Turner conducted a videotaped interview with convicted "coed killer" John Norman Collins. Clips from that interview were interspersed among the live portions of the popular Detroit morning talk show, Kelly and Company, on the following Monday.

On Friday, October 1, 1988, Marilyn Turner conducted a videotaped interview with convicted "coed killer" John Norman Collins. Clips from that interview were interspersed among the live portions of the popular Detroit morning talk show, Kelly and Company, on the following Monday.This interview is the only footage of Collins I have been able to find, except for a couple of perp walks in and out of court.

Part four of the interview was reserved for the supporters of John Collins who gave their assessment of his innocence. First was Marlene Thompson, ordained minister in the International and National Universal Life Church of Love. She had been Collins "spiritual adviser" for almost four years. Her view was that he was a caring and intellectual person who "shows great concern for women and couldn't kill anything."

Part four of the interview was reserved for the supporters of John Collins who gave their assessment of his innocence. First was Marlene Thompson, ordained minister in the International and National Universal Life Church of Love. She had been Collins "spiritual adviser" for almost four years. Her view was that he was a caring and intellectual person who "shows great concern for women and couldn't kill anything." The other Collins' supporter on the panel was a reporter for the Oakland Press, Jackie Kallen, who had been writing Collins in jail and later in prison, since 1969 when he was arrested.

Ms. Kallen had some "mutual friends" with the Collins family. She opined that he may have been "railroaded" into prison. Her fervent belief was that "Collins is open and tells the truth as he perceives it. Maybe he doesn't know what he did."

The most remarkable and probing part of the whole show was when Marilyn Turner asked John Collins, in a calm soothing voice, "Did you love your mother, John?"

With that one well-placed, personal question, she was able to penetrate his self-protective stratagems and catch him in an unguarded moment. Until that time, he asserted his control over the interview, then he lost control of his emotions and seemed disoriented from that point on.

With that one well-placed, personal question, she was able to penetrate his self-protective stratagems and catch him in an unguarded moment. Until that time, he asserted his control over the interview, then he lost control of his emotions and seemed disoriented from that point on.There is a wise saying that applies here, "Never play a player." Marilyn Turner did a great job interviewing a difficult subject.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=30SAljur34Q

Published on December 29, 2012 17:09

December 25, 2012

John Norman Collins Interview Inside Marquette Prison With Marilyn Turner - October, 1988

After John Norman Collins and his various attorneys exhausted all of his appeal avenues, he decided to talk to the media and take his case to the people on Monday, October 3, 1988.

After John Norman Collins and his various attorneys exhausted all of his appeal avenues, he decided to talk to the media and take his case to the people on Monday, October 3, 1988.Kelly and Company, a popular morning talk show in Detroit, wanted to do a live satellite feed from the prison with the show's co-host, Marilyn Turner. The studio portion of the show with a panel of key people from the case and a live studio audience would be handled by John Kelly, who happened to be Marilyn's husband.

The Friday before, the prosecutor who tried the case, William Delhey, declined to appear. He did not want to be a "question-and-answer man" for a staged courtroom scene.

Then the prison warden reneged on the live broadcast citing security reasons. Producers for the show managed to get him to agree to a taped interview.

The link below is the Collins interview portion of the show. Collins was forty-one at the time and had been behind bars for just over eighteen years. This twenty-five year old Kelly and Company video was the first time most people saw Collins or heard him speak.

http://youtu.be/G779Uw09eMs

Published on December 25, 2012 19:48

December 21, 2012

The People's Gamble in the Collins Trial - 1970

The weekend before the John Norman Collins trial was to begin, news hungry reporters began writing stories about the "epic" battle that was about to occur between legal "Titans," William F. Delhey, representing The People, and Joseph W. Louisell, sometimes called "Michigan's Perry Mason," representing Collins. Each attorney had a wing man. Delhey had Booker T. Williams and Louisell had Neil Fink.

The reality of the clash was a disappointment. Jury selection took a tedious six weeks. The defense strategy was to want a white collar "college educated" jury who would be able to weigh the scientific testimony they would be hearing and to withhold judgment possibly.

The prosecution favored a more blue collar "working class" jury who would be blinded by the blizzard of technical information and more moved by emotional arguments and appeals.

The defense kept the judge and the court clerk busy with motion after motion, until it seemed that the actual trial would never begin. Then suddenly, the defense told presiding Judge Conlin that they had a jury.

Louisell surprised the prosecution and caught them flat-footed with a handful of peremptory challenges they couldn't use. Courtroom observers scored the first round for the defense team. The press reported later in the day that this jury may be the most highly educated in Michigan state history.

By the end of the trial, the prosecution had called forty-eight witnesses in seventeen days, in marked contrast to the defense who called only eight witnesses in four days. The jury deliberated for four days before it returned a guilty verdict of murder in the first degree against John Norman Collins in the wrongful death of Karen Sue Beineman.

The prosecution's "key play" was the strategic decision by the chief prosecutor, who had the scientific background, to pass the cross-examination of scientific witnesses to his assistant prosecutor, who had no laboratory background.

Although this might seem counter-intuitive, Delhey didn't want to "slip into laboratory language": He wanted Williams to ask questions using "layman's language" to be better understood by the layman jury, despite the high percentage of college graduates on the jury.

When the prosecution's scientific hair fiber experts were challenged and discredited by the defense's hair fiber experts, Delhey's strategy paid off. Williams took the edge off the data and focused on the testimony of the defense experts, pointing out their discrepancies and inconsistencies. In the end, the hair clipping evidence was solid enough in the minds of the jury to link Collins to his victim.

Surprisingly enough, it wasn't the scientific blood or hair evidence that convicted John Norman Collins. It was the preponderance of circumstantial evidence and the lack of a credible alibi for the critical three hour period between Karen Sue Beineman's disappearance and her strangulation death in the basement of his aunt and uncle's Ypsilanti home.

Published on December 21, 2012 10:45

December 15, 2012

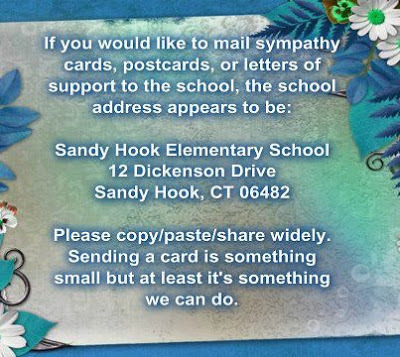

Sandy Hook Address - Send a Card or Flowers

Will the carnage never end?

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2012/12/14/nine-facts-about-guns-and-mass-shootings-in-the-united-states/

Published on December 15, 2012 07:37

December 14, 2012

The Prosecution Team for the People vs. John Norman Collins

John E. Peterson of The Detroit News reported after the guilty verdict was announced in the John Norman Collins case that "the two prosecutors had no use for histrionics. They were concise and they were precise. Prosecutor William F. Delhey and Assistant Prosecutor Booker T. Williams came out of the trial looking more like clinical workers than dramatists."

John E. Peterson of The Detroit News reported after the guilty verdict was announced in the John Norman Collins case that "the two prosecutors had no use for histrionics. They were concise and they were precise. Prosecutor William F. Delhey and Assistant Prosecutor Booker T. Williams came out of the trial looking more like clinical workers than dramatists."On Sunday, May 31, 1970, two days before the Collins trial was to begin, William B. Treml wrote in The Ann Arbor News that Prosecutor Delhey was "cool, unemotional, professional. He has a fifteen year reputation for being meticulous, methodical, and calculating in the preparation of a criminal case."

Delhey was forty-five years old and had a wiry, athletic build and a penetrating voice. He lettered in football for three years at Ann Arbor High School and placed second in the 880 yard dash in the 1942 state track meet. Delhey enlisted in the Army Air Corp and took pilot training but World War Two ended before he saw any combat action.

After his enlistment, he earned a Bachelors of Science degree in 1947 from The University of Michigan. He worked as an air pollution chemist for the Ford Motor Company and took night classes part-time at The University of Detroit graduating with a law degree in 1954.

Delhey went into private practice in 1955 and became assistant prosecutor in Washtenaw County in 1957. In January of 1964, he was appointed prosecutor and won the office outright in the November elections of that year. He was re-elected in 1968.

William Delhey was married and had two boys and two girls, ages ranging from two through twelve. Politically, he was said to be a Republician.

***

Assistant Prosecutor Booker T. Williams was forty-nine years old and born in North Carolina. He had combat experience in the Pacific theater of war as a sergeant in World War Two.

Williams also worked his way through school. He began at The University of Pennsylvania in 1947-1948 and moved to Ypsilanti in 1950. He paid the bills by working as a night clerk in an Ann Arbor hotel and earned a bachelor of arts degree in 1952, and his law degree in 1955, both from The University of Michigan.

Booker T. Williams went into private practice but joined the prosecutor's staff in 1958 and left in 1960. When William Delhey was appointed prosecutor in January in 1964, Williams returned to become an assistant prosecutor.

While he was actively engaged with the Collins trial, Booker Williams had to overcome personal tragedy. During the jury selection process, his wife Arletta Marie had a heart attack. He took off nineteen days to be with her at her bedside before her death and another week to get his household of seven young children organized. Williams was the father of six boys and one girl, ages ranging from thirteen to nineteen months.

John Peterson wrote that "Williams effectively poked holes in the scientific testimony of defense experts sniffing out inconsistencies and hammering away at discrepancies. He earned a reputation for rapid-fire, rapier cross-examination."

Prosecutor Delhey lauded Williams for his work on the Collins' trial and said it was critical to the People's case.

Published on December 14, 2012 07:43

December 9, 2012

Lawyers for the Defense in the John Norman Collins Case

John Norman Collins' legal team - Neil Fink and Joseph Louisell - June 1970

John Norman Collins' legal team - Neil Fink and Joseph Louisell - June 1970Immediately after John Norman Collins was arrested on July 30, 1969, his mother Loretta retained the legal services of Robert Francis and John M. Toomey of Ann Arbor, Michigan.

A week later on August 7 during a preliminary examination, Mr. Toomey told presiding Washtenaw County Circuit Judge Edward D. Deake that he had discussed withdrawing from the case with Collins and his mother. The reason given was lack of funds and Mrs. Collins' "inability to undertake further financial liability."

"John will benefit by a court-appointed attorney because this will give him the right to a lot of things, such as the court paying for independent blood tests, ballistic tests, and fingerprints," Toomey explained. "Mrs. Collins indicated that she might not be able to afford this type of work and wanted a court appointed attorney."

The judge agreed, and on August 12, 1969, a three-judge Circuit Court panel appointed Richard W. Ryan to handle the case. Ryan asked Francis and Toomey (Collins' original attorneys) to stay on as co-counsels at county expense to assist him with the defense.

Ryan and his team were on the case for only a couple of months when Ryan began to have doubts about his client. He requested Collins take an off the record polygraph (lie detector) test. Collins agreed but Ryan refused to disclose the results.

When conferring afterwards with the family in the judge's chambers, Ryan suggested a "diminished capacity" plea for an insanity defense. Mrs. Collins flew into a rage and fired him on the spot.

Then The Detroit News reported on November 25, 1969, that Joseph W. Louisell and Neil Fink from Detroit had agreed to defend Collins after conferring with Mrs. Collins and other relatives over a two week period. It was agreed that they were to take over the case on December 1st.

When Neil Fink was asked by the press how Mrs Collins could afford the highest priced law firm in the state of Michigan, when she had plea poverty in open court only months before, he made no comment.

The Detroit Free Press reported the next day that "Mrs. Collins, who is a waitress, reportedly has received a pledge from a national magazine for a large sum of money in exchange for the exclusive rights to her son's story." No evidence of such an offer exists.

Enter the man who has been described as "Michigan's Perry Mason," Joseph Louisell, the Detroit area's Mafia mouthpiece. In the decade before the Collins' case, he was best known for defending reputed Mafia figures including Pete Licavoli, Anthony and Vito Giacalone, and Matthew (Mike, the Enforcer) Rubino. All of these men were identified as Mafia chieftains in testimony before the U.S. Senate in 1963.

The fifty-three year old father of ten, five boys and five girls, Louisell had a "hefty figure" with a "round jowly" face that was familiar to Detroit courtroom observers who watched him build a strong reputation as a prominent criminal lawyer.

He gained fame for his successful 1949 defense of Carl E. Bolton and Carl Renda, both charged with shooting United Auto Workers President Walter Reuther in the back.

Another notorious case was the acquittal of blond and beautiful Nelle Lassiter, who was charged with conspiring with her lover to dispose of her husband's body, used car dealer, Parvin (Bill) Lassiter.

Some of Louisell's critics have complained of his courtroom theatrics. "All trial lawyers are ham actors at heart. Especially me, I guess," he said. "Normally 65% of my practice is in civil and corporate law. That's where the money is. But criminal law has some kicks. That's for fun."

Neil Fink was a thirty year old junior partner in the firm of Louisell and Barris. He assisted his senior partner and handled all the pre-trial examinations and defense motions.

He stayed active in the case while his boss was recuperating from a heart attack he had on February 2, 1970. Louisell's doctor said he would permit Louisell to return to work on April 1. Fink handled the entire Collins case load for a couple of months

Rumors circulated about how a waitress at Stouffer's in downtown Detroit could afford such a high priced legal firm. Just for the record, Mrs. Loretta Collins refinanced her home in Center Line for an undisclosed amount to cover the estimated $15,000 it would take to cover her son's legal fees.

(Next post: The Prosecution Team for the People against John Norman Collins)

Published on December 09, 2012 15:11

December 2, 2012

The John Norman Collins' Prison Papers

Blocking the facts and details of the John Norman Collins coed killer case, through the trial and sentencing, has been a time consuming and tedious process. But bringing out the voices of the past by reconstructing the dialogue of the witnesses testimony from newspaper reports of the day has been insightful and fascinating.

Working with old information and with what we've learned about this case since the seventies, an account is starting to form which will give a more textured and resonant picture of the trial than the phonetically transcribed court transcripts would have, which incidentally were unavailable to me. The Washtenaw County Courthouse Records Department has "purged" this case from their records.

My researcher, Ryan Place from Detroit, and I are entering uncharted territory now - the John Norman Collins prison years. Using the Freedom of Information Act, we were able to secure a thousand prison documents from the Michigan Department of Corrections.

Once we paid our tribute ($500), we were sent a box full of unsorted photocopies which had to be categorized, placed in chronological order, and thinned of duplicate copies. Of the one-thousand photocopies we purchased, only about three-hundred are useful to us, and many of them are routine paperwork of little or no interest to the general reader.

The good news is that now I have a manageable amount of information to work with, and a picture of John Collins' years behind prison bars is beginning to take shape.

When we saw the initial amount of prison materials, we hoped that we had received the full sweep of his four decades in prison at Marquette, Jackson, and several other Michigan correctional institutions, including a short stay at Ionia, which houses Michigan's mentally ill and deranged prison population.

But there are huge gaping holes in the chronology of his many years in prison. Still, there is some interesting factual information to be found among the routine and often sketchy paperwork.

Something missing is any information on John Collins attempted prison breaks, especially a tunneling attempt he made with six of his prison inmates. They tried to dig themselves toward an outside wall of Marquette prison in Michigan's Upper Peninsula.

Discovered by a prison guard on January 31, 1979. Collins and six other convicts dug nineteen feet toward an outside wall within thirty-five feet of freedom. They had been scooping out handfuls of sand since the previous summer.

The prisoners were charged with breaking the prison's rules but little more is known about the incident. There must have been an investigation, but we don't have any evidence of any. Were escape charges ever brought against them? I'd like to know more and will pursue it further.

It would have been nice to get a well-organized and concise information drop from the Michigan Department of Corrections, but they aren't in the business of helping me do research for my book, In the Shadow of the Water Tower.

It is the search for knowledge that drives me and my researcher to uncover as much about these matters as we possibly can and to shed light on this dimly remembered and deliberately shrouded past.

Published on December 02, 2012 14:50

November 25, 2012

HOW THE GRINCH STOLE CHRISTMAS! Now playing at San Diego's Globe Theater in Balboa Park

Saw this with my daughter and granddaughter on Saturday. If you are in the San Diego area this holiday season, catch this show. You won't be disappointed.

http://www.theoldglobe.org/?gclid=CNnq_5Xe67MCFaGPPAod9Q0Akg

Published on November 25, 2012 20:07