Gregory A. Fournier's Blog, page 47

February 19, 2013

The LeForge Barn Fire - Murder Site of Dawn Basom - John Norman Collins' Victim

Barn next to abandoned farm house on Geddes and LeForge roads.

Barn next to abandoned farm house on Geddes and LeForge roads.On Thursday, May 13, 1969, a barn only 100 feet from the abandoned farmhouse, believed to be the site of Dawn Basom's murder, was set ablaze at 3:17 in the morning.

***

Thirteen year old Dawn Basom was an eighth grader at West Junior High School in Ypsilanti and the youngest of The Rainy Day Murder victims.

Dawn was last seen alive on April 15, 1969, while walking down the Penn Central railroad tracks which was the short cut to her home on LeForge Rd. She had promised her mother she would be home before dark.

Sergeant William Stenning of the Ypsilanti City Police Department received a call at 12:46 AM on April 16, 1969, from Mrs. Cleo Basom saying her daughter had been missing since late afternoon on Tuesday.

Mrs. Basom said that Dawn was given a ride by her uncle to the corner of Cross and River Sts in Depot Town early in the evening to meet a boy friend by the first name of Earl, last name unknown. She was last seen wearing a white plastic jacket, white cotton blouse, and blue stretch pants.The next morning, Dawn's abused and naked body was found on the east edge of Gale Rd just north of Vreeland Rd, about a mile from her murder site at a barn on Geddes and LeForge Rds.

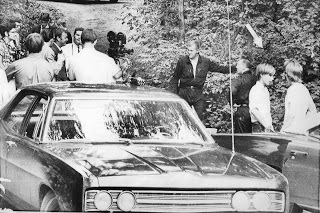

Mrs. Basom said that Dawn was given a ride by her uncle to the corner of Cross and River Sts in Depot Town early in the evening to meet a boy friend by the first name of Earl, last name unknown. She was last seen wearing a white plastic jacket, white cotton blouse, and blue stretch pants.The next morning, Dawn's abused and naked body was found on the east edge of Gale Rd just north of Vreeland Rd, about a mile from her murder site at a barn on Geddes and LeForge Rds.  Sheriff Harvey showing spot where Dawn's body was found.

Sheriff Harvey showing spot where Dawn's body was found.During the subsequent investigation of Dawn's murder, State Police crime scene investigators found articles of her clothing in the cellar of the nearby farmhouse and other evidence linking the site to Miss Basom's murder.

Her murderer had to use a car to capture Dawn and take her away unnoticed. She was tom-boyish and liked to wrestle with her older brothers in the front yard of their house, so she would have probably put up a struggle and offered some resistance to being captured.

It was unlikely she would accept a ride from a stranger so close to her home, less than 100 yards, though she was known to hitchhike.

More likely, someone laid in wait for Dawn and overpowered and incapacitated her, or perhaps she knew or recognized the person she got into the car with. Either theory ends up with Dawn being held captive in a psychopath's car.

***

Twenty-nine days after Dawn's killing, the barn adjacent to the farmhouse murder site burned to the ground. The Michigan State Police arrested an Eastern Michigan University student from Harper Woods, Ralph R. Krass, 21, on Friday, May 15, at his apartment at 1431 LeForge Rd which happened to be near the Basom home on the same street.

He was arraigned by District Judge Rodney E. Hutchinson and stood mute when the judge set the bail at $5,000. Unable to post bond, Krass was taken to the County Jail.

Michigan State Police expected more arrests but were unable to confirm that the barn burning had any connection with the murder investigation. The arson was still under investigation.

Three days after the arrest of Krass, his roommate, Clyde Surrell, 19, of Ypsilanti, stood mute on a charge of aiding and abetting arson. He was released on $2,000 bond pending a hearing on the matter.

Police say that Krass admitted walking to the farm with two companions and setting some dry hay on fire in the barn's loft. The three young men ran away but returned while the Superior Township Fire Department allowed the fully engulfed barn to burn to the ground. They prevented the farmhouse and the cellar from catching fire but not from sustaining water damage.

When the last of the blaze was extinguished, a reporter looking over the smoldering ruins discovered five, fresh cut, purple lilac blossoms lying nearby. He theorized that someone left one for each of the five murdered girls.

After an investigation, authorities charged the men with arson but cleared them of any involvement in the Basom murder. Mr. Krass gave no reason for burning down the barn.

Published on February 19, 2013 20:22

February 14, 2013

Ypsilanti Water Tower Title Replaced

When I began writing about the Ypsilanti/Ann Arbor coed murders of 1967-1969 almost two years ago, I decided on the title In the Shadow of the Water Tower. It had a noirish and pulp-fiction quality that seemed to suit the subject matter.

In addition, the first two victims and their alleged murderer lived virtually in the shadow of the water tower. As I got deeper into the research and learned more about the facts and the people connected with these cases, I became increasing uncomfortable with the title.

Then it struck me. Why taint Ypsilanti's beloved landmark with the John Norman Collins controversy? The Water Tower played no role in any of the seven murders that Collins is thought by many to have committed.

I decided to change the name of my non-fiction book to The Rainy Day Murders, which is what the media called these killings early on because rain was a factor in most of the murders.

Some police investigators thought that the rain may have acted as a trigger that drove the murderer to kill. Other investigators thought the rain helped destroy evidence at the body drop sites, and the killer was merely perfecting his stealth.

The Rainy Day Murders title also presents the thematic subject matter of the work right up front. The word "murder" is a strong and evocative image that clearly labels the product inside.

***

This Michigan Historic Landmark, completed in 1890, has stood proudly for 123 years. Built on Ypsilanti's highest point, the 147 foot tall building is clad in Joliet limestone with four crucifixes set into the stonework to protect the workers who built it.

This Michigan Historic Landmark, completed in 1890, has stood proudly for 123 years. Built on Ypsilanti's highest point, the 147 foot tall building is clad in Joliet limestone with four crucifixes set into the stonework to protect the workers who built it.On a personal note, my wife and I were walking to McKinney Union, sometime in the mid-Seventies, heading south down Summit St. Two city workers were pouring a new cement sidewalk leading up to the double door entrance of the Water Tower, whose tall doors were swung wide open.

I asked if we could go inside and take a peek. One of the workmen said, "Sure."

Grinning, we entered and started up the stairwell. Many people since 1890 had left their mark and written their names on the walls over the years. Somewhere near the top of the staircase on the inner wall, we signed our names and dated it with permanent marker.

Once in the top portion, wooden cross braces and other structural elements were visible, as was some radar and other buzzing electrical equipment. The entrance to the cat walk was locked so we couldn't see the magnificent 360 degree view of Eastern Michigan University and the nineteenth century residential section of historic Ypsilanti.

Local university legend has it that when a virgin graduates from EMU, the tower will fall down. Such legends exist at many universities, but Ypsilanti and Eastern experienced the "rainy day murders" up close and personal. Now the expression isn't as clever or funny as it once seemed.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ypsilanti_Water_Tower

Published on February 14, 2013 07:49

February 9, 2013

The Ann Arbor Mallet Murder

Saturday, September 15, 1951, had been a hot day in Ann Arbor, but near midnight it was pleasantly cool. Pauline Campbell (34) had just finished her evening shift working the maternity ward at St. Joseph's Mercy Hospital. She crossed Observatory Street kitty-corner and headed down Washington Heights, a narrow, darker street towards where she lived several houses away.

***

Only four nights before, a man had slugged a nurse with a blunt instrument while walking home from University Hospital in this same neighborhood.

Bill Morey, Max Pell, and Dan Meyers were recent Ypsilanti High School graduates. On Wednesday night, they drove to Milan and bought two six-packs of beer at a tavern known to sell to minors.

Dan Meyers owned the car but didn't have his license yet and allowed Bill Morey to drive his car that night. They were cruising Ann Arbor, according to Dan, because they wanted to steal some hubcaps they could sell or trade for an "echo can," a fifteen inch chrome exhaust pipe for his car.

Rather than steal hub caps on a quiet, shadowy street, Bill drove towards University Hospital which is a well-lit area. The three of them were tipsy, and Bill decided he wanted to pick up some girls. On the way over there, Max and Bill began talking about snatching a nurse's purse. Later in court, Dan testified that it was mainly Bill's idea.

"Let's hit somebody over the head and rob them," Bill said. There was a 12" crescent wrench among some loose tools under the front seat they used to steal car parts. "This should do it," he said, striking his open palm to test its heft.

"Let's hit somebody over the head and rob them," Bill said. There was a 12" crescent wrench among some loose tools under the front seat they used to steal car parts. "This should do it," he said, striking his open palm to test its heft.The street was busy, but when they saw a nurse alone walking up a deserted street, Bill said, "I'm going to hit her and drag her into the car." In court, Dan Meyers claimed he kept telling Bill not to do it, but he didn't hold Bill back nor did he shout out a warning to the nurse.

Bill got out of the car swiftly and walked up behind the unsuspecting nurse and swung the wrench. He hit her - but she didn't fall down - she screamed and ran. Bill ran back to the car, and the three teenagers drove away laughing about the failed attempt.

Shirley Mackley was able to describe her attacker for police: five feet, ten inches tall; about one-hundred and seventy-five pounds; and young, possibly twenty years old. She was not seriously hurt. Her attacker had wanted to stun her and drag her into the car, so he had held back a fatal blow. That wouldn't happen again.

***

Four nights later, Bill Morey and Max Pell were out cruising again, but this time with Dave Royal, someone they recently met. Max was driving his beloved car that night.

They talked Dave into paying for the beer because he worked construction and had money. Max bought a case of beer, and they split it between themselves and two "wild" girls Bill knew from Milan. Dave was the odd man out and drank alone in the car.

They talked Dave into paying for the beer because he worked construction and had money. Max bought a case of beer, and they split it between themselves and two "wild" girls Bill knew from Milan. Dave was the odd man out and drank alone in the car.They drank most of the beer and dropped the girls off at their homes at about eleven. The inebriated trio headed into Ann Arbor. That's when Bill told Max Pell, "Go up around the hospital."

There was a rubber mallet with a foot long wooden handle in the car, that Max's father used to repair household furniture. They spotted a lone nurse leaving Mercy Hospital. She crossed Observatory St. kitty-corner and starting down the hill on Washington Heights St. which was narrower and darker.

Max turned off his headlights and Bill said, "Let me out here behind the nurse."

With Bill on foot, Dave asked Max if Bill intended to assault and rob the nurse. "I know he had it on his mind, but I don't know if he is going to do it."

Wearing moccasins, Bill gained on the nurse, rushed her from behind, and knocked her unconscious. Bill struck her several more times, then he called out to Dave to help him drag her limp body to the car.

They got as much as her head in the car when Max saw her and told them, "Don't put her in the car!" They dropped her body in the street and drove off leaving her unconscious. She was to die soon after in the hospital where she had just finished her shift.

The young thugs took Huron River Drive back to Ypsilanti, but not before Bill went through the victim's purse. In it was a cigarette lighter, a watch, and a dollar and a half. From a bridge, they threw her purse into the Huron River. Afterwards, they bought ninety-four cents worth of gas, ate sandwiches, and drank coffee to sober up at a truck stop called the Fifth Wheel.

***

After the first nurse attack, Bill confessed to his good friend, Dan Baughey, who was on probation at the time, that he was the person who hit the nurse. When Dan heard about the killing of the second nurse, he was urged by his priest and his father to tell the police what he knew.

At 3:00 PM on Wednesday, September 19, Dan Baughey reported to police, and the three suspects were apprehended. On their drive from the Ann Arbor police station to Lansing to take lie-detector tests, Bill chatted with detectives about police cars. That's all he talked about. Dave Royal didn't say much for most of the ride.

But Max Pell was worried chiefly about his car which had been taken into evidence. He told the police that he recently put a new engine in it and asked them not to drive it over fifty miles an hour.

The young toughs confessed when they got to Lansing. Max Pell was the first to break down when police told him they were going to cut up his car's upholstery to check for blood evidence.

"You don't need to tear my car apart - I'll tell you. It's blood."

***

The victim, Pauline Campbell, was an orphan born in Ohio and raised by a farm family. She worked her way through college as a housemaid and later as a nurse's aide. She was single, quiet, tidy, and rather slight of build said her landlady.

Less than six weeks after the arrest, the case went to trial. The courtroom as packed with local teenage girls, some who managed to get their pictures in the paper and later got in trouble for skipping school. When the defendants entered or left the courtroom, Bill was always first, then Max, and then Dave.

In his summation, Washtenaw County Prosecutor Reading told the jury that "...on the night Miss Campbell was killed she, unlike the three teens, had been working and working at a task that benefits other people." He asked the jury to bring forth a first degree murder conviction for all three defendants.

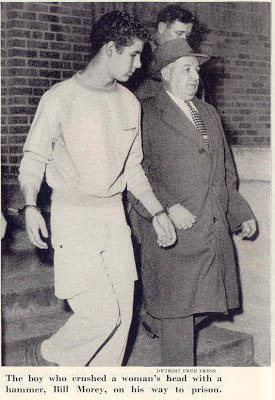

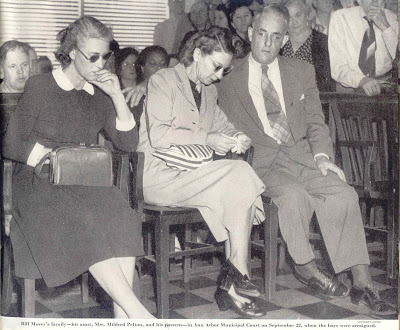

Bill Morey's aunt, mother, and father at arraignment.

Bill Morey's aunt, mother, and father at arraignment.Bill Morey and Max Pell were found guilty of murder one and given life sentences. Dave Royal was convicted of second degree murder and got twenty-two years to life for his part. Dan Meyers was sentenced to serve one to ten years for his complicity in the attack upon the first nurse who survived.

***

After the trial, the community of Ypsilanti felt that the finger of shame was being pointed at them for letting their kids run wild and get out of control. This was true from the Ann Arbor News perspective and the Detroit newspapers also.

The city of Ypsilanti went into a defensive mode. One former Ypsilanti policewoman, Mrs. Dellinger, was quoted as saying, "The community has committed itself to a hush-hush policy. My feeling is that there will be another episode just as horrifying before this community can be awakened."

Sixteen years later, the first of the Rainy Day Murders struck the Ypsilanti community. This time a serial killer was on the loose, and the rubber mallet murder had long been forgotten.

Published on February 09, 2013 18:36

February 5, 2013

Psychic Peter Hurkos vs. John Norman Collins

Ancient myths and tales abound with stories about oracles, seers, soothsayers, sorcerers, and fortune tellers. Common among these legends is an appeal to a charmed man or woman who has the gift of inner vision. Usually, the person comes from outside the village or town where an overwhelming problem is plaguing the community and he or she agrees to relieve the populace from their resident evil.

Since Jack the Ripper cast a pall over London's East End in 1888, in virtually every serial murder case that goes unsolved for any length of time, a psychic is called in to relieve the public of their collective angst. It is a common appeal for supernatural assistance when confidence in local law enforcement erodes.

Murderous crimes that go beyond simple killing and become ritualized orgies of carnage and butchery evoke antediluvian images of blood thirsty ghouls, evil witches, and demons in league with Satan. These images are deeply embedded in the human psyche and express our deepest psychological fears.

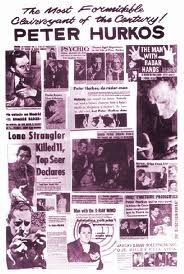

Enter psychic Peter Hurkos, the self-proclaimed first police psychic, arguably the most famous psychic of his day. Hurkos believed he had a "psychometric" sense, the ability to gain information about people from physical contact with inanimate objects they had touched. He also believed he could enter a crime scene and pick up an aura. "Vibrations" he called them.

Enter psychic Peter Hurkos, the self-proclaimed first police psychic, arguably the most famous psychic of his day. Hurkos believed he had a "psychometric" sense, the ability to gain information about people from physical contact with inanimate objects they had touched. He also believed he could enter a crime scene and pick up an aura. "Vibrations" he called them.Peter Hurkos honed his skills into a popular nightclub act and rubbed elbows with many Hollywood and Las Vegas celebrities. He was a favored guest on the talk show circuit and appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, The Merv Griffin Show, and The Dinah Shore Show to name just a few.

After an inauspicious performance and ensuing bad publicity from his work on the Boston Strangler case in 1964, his bookings were fewer and farther between. He just wasn't news anymore.

His agent fielded an offer she took over the phone for him to go to Ann Arbor, Michigan, and see if he could help with the coed killer case there. At first, Hurkos declined, but his agent convinced him that if he could help find the killer, his career would get a boost.

On Monday, July 21, 1969, as he was getting off the plane at Detroit's Metropolitan Airport, Hurkos noticed a cadre of media waiting on the tarmac to interview him. There were too many newsmen chasing too little news in Ann Arbor, and Hurkos put some new life into the story, so they were there to welcome him, and he didn't disappoint them.

With characteristic bravura, the Danish psychic challenged the killer, "He knows I'm coming. I'm after him and he's after me. But I am not afraid. I come thousands of miles to find him and I won't give up."

While he was in the area, the Danish psychic wanted to examine the landmarks of the cases and handle items of evidence obtained from earlier police investigations. What harm could there be with that?

Taking exception to Peter Hurkos' unauthorized collaboration on the case was Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas Harvey. There were chain of custody issues regarding the collection, cataloging, storage, and admissibility of evidence. Law enforcement didn't have the time to waste on a man who some people thought was a media hound.

Taking exception to Peter Hurkos' unauthorized collaboration on the case was Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas Harvey. There were chain of custody issues regarding the collection, cataloging, storage, and admissibility of evidence. Law enforcement didn't have the time to waste on a man who some people thought was a media hound. Peter Hurkos, with five police escorts, explored the Friday Ann Arbor nightlife to get a feel for the area. Hurkos also wanted to personally thank John Sinclair and members of his commune at Translove Energies on Hill St. in Ann Arbor. They were the people who raised the money to summon the psychic from California.

When Hurkos returned to the Inn American early the next morning where he was lodged, the desk clerk told him that a young man about six foot tall with slicked down hair and wearing a turquoise colored shirt, handed her an envelope at about midnight addressed to Dutch psychic/Peter Hurkos.

When his police security detail asked if she could recognize him again, she said, "No. I was busy with another customer and it happened so quickly. He was gone."

Hurkos opened the letter and read it silently. It directed him and the police to search for a burned out cabin on Weed Rd. in the northeast corner of Washtenaw County not far from where several other murder victims were found. They would find "something interesting" there the note assured them. The psychic had finally been enjoined in direct communication with the killer.

Hurkos had a "feeling" about this message and gave it to the police to investigate. Then he went to bed. A crew of investigators was hastily formed to investigate the tip in the middle of the night in the pouring rain. They searched the entire area for a burned out cabin they would never find. After an hour, the police returned to the Task Force Crime Center. They had had their fill of Mr. Hurkos.

Three days after Karen Sue Beineman had been reported missing on Wednesday, July 23, her nude body was found in Ann Arbor township, face down in a small gully. The dump site was less than a mile from the Inn America where Hurkos was staying and the Holy Ghost Fathers Seminary where the crime task force was headquartered.

The latest murder and the disposal of the body were a blatant affront to everyone connected with this case. Even worse for Hurkos, news of the police finding Miss Beineman's body was kept from him. When he was asked by a reporter for a comment on the matter, he was totally in the dark. The Dane was furious and complained to the prosecutor's office.

During his uneventful week in Ann Arbor, Hurkos cast a wide net. He variously described the killer as a troubled genius, an uneducated vagrant, a sick homosexual, a transvestite, a member of a blood cult, and a drug crazed hippie.

Arrow points to site where Karen Sue Beineman's body was discoveredOnce Miss Beineman's body was removed from the gully and the scant evidence secured by the State Police Crime Lab, Hurkos was escorted by the assistant prosecutor and permitted to examine the drop site. Under the withering glare of Sheriff Harvey from the street above, Hurkos made his way down the gully to the spot where the body had been found.

Arrow points to site where Karen Sue Beineman's body was discoveredOnce Miss Beineman's body was removed from the gully and the scant evidence secured by the State Police Crime Lab, Hurkos was escorted by the assistant prosecutor and permitted to examine the drop site. Under the withering glare of Sheriff Harvey from the street above, Hurkos made his way down the gully to the spot where the body had been found.He got down on his haunches and spread both hands out and felt the ground where the body had been. Try as he might, the spot was cold, no vibrations or emanations of any sort.

With growing resistance from the police and his press entourage shrinking, there was little to be gained by staying in Ann Arbor. Hurkos and his assistant, Ed Silver, left town on Monday, July 28th, headed for the West Coast.

In the end, Sheriff Harvey turned out to be the only clairvoyant on this case. He predicted, "I think these murders will be solved with good old-fashioned police work." Their prime suspect was under arrest within a week.

One Step Beyond: "The Peter Hurkos Story" 1/6 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RTXPzVIugsg

Published on February 05, 2013 07:06

January 31, 2013

The Media, the Police, and the Washtenaw County Murders - 1967-1969

Before law enforcement and the public realized there may be a serial killer in their midst, three local coeds were found murdered and left scattered around the rural countryside of Washtenaw County outside of Ypsilanti and Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Mary Fleszar (19) disappeared on the evening of July 9, 1967. She was an Eastern Michigan University student whose body was found a 150 yards from the road on an abandoned farm thirty-two days after she disappeared. In the absence of any real clues, police investigators surmised that she may have been killed by a transient and dumped there. The condition of her remains shocked detectives on the scene.

Just over a year later, on July 30, 1968, another EMU coed, Joan Schell (20) was hitchhiking and seen getting into a car with three young men. Her body was found a week later on the outskirts of Ann Arbor. Police determined that she had been killed elsewhere, and her nude body was dumped 12 feet from the road and covered with grass clippings. Little effort was made to conceal the body.

A couple of investigators familiar with the Fleszar case the year before thought that these murders could possibly be related, but Schell's murder was generally regarded as an isolated incident by most investigators.

A third coed was found murdered eight months later; University of Michigan graduate student, Jane Mixer (23). Her fully clothed body was laid out on a grave site just inside the gate of Denton Cemetery, a yellow raincoat covered her up.

Detectives on the scene felt that this murder was significantly different than the previous two, but the press ran with the story and began linking the three murders together in the public's mind.

A self-perpetuating engine of public opinion was fueled by the public's desire for the latest news and the media's commercial and competitive interests. This relationship led to the breakdown of collective solidarity in the communities of Ypsilanti and Ann Arbor. A generalized fear gripped the public psyche, suspicion ran rampant, and faith in law enforcement efforts declined. Fear fed upon itself and magnified divisions already in the community.

To provide the community with a sense of psychological comfort and help contain the threat, the police floated the story that the killer or killers were a bunch of drug crazed transients. This well-publicized fiction was based on wishful thinking and may have prevented police from recognizing the killer when he was in their custody. Their suspect was clean cut and simply didn't fit the profile.

The universities attracted lots of non-student hippie types who always seemed to be hanging around causing trouble. After all, the murdered girls were college students, so the threat may be limited to EMU and U of M and not the general populace.

Only five days after the Mixer murder, Maralyn Skelton's dead body was found horribly abused along a roadside. She was a sixteen year old who recently dropped out of high school and was last seen hitchhiking in front of Arborland on Washtenaw Ave.

Twenty-one days later, Dawn Basom (13), a local Ypsilanti junior high school student was snatched less than 100 yards from her house. Now the frenzied community felt no one was safe. The rate of the slayings was increasing and the death toll was rising.

When the police were powerless to capture the killer, the public appealed for divine intervention. The media reported on prayer vigils held in local churches, and some religious people believed that the deaths of the victims had some sort of sacrificial purpose and spiritual significance.

Marjorie Beineman, the mother of the last victim, believed, "God must have sent Karen to find the killer." She was convinced that her daughter's sacrifice was according to God's divine plan to save others, precious little comfort for a grieving mother.

Still, others believed that the killer was thought to have a Svengali type of hypnotic, superhuman power to spirit his victims away without a trace. If God's divine presence can take human-saintly form, then the opposite must be true, the devils' disciples exist on Earth as evil incarnate.

The public was desperate for its deliverance from evil. Faith in the local police was at an all time low, and there were too many reporters chasing too little news. Something had to be done to move this case along.

Enter the psychic - Peter Hurkos. His presence gave the media something new to report on, but the police were not happy with this interloper. Assistant Prosecutor Booker T. Williams had a more proactive attitude, "What is there to lose? Maybe he can help break the case."

Published on January 31, 2013 06:41

January 27, 2013

Preston Tucker from Ypsilanti, Michigan

One of the more notable and least recognized of Ypsilanti's citizens was Preston Tucker, an automobile innovator who many people believed was way ahead of his time In 1939, Tucker moved to Ypsilanti, Michigan, and opened the Ypsilanti Machine and Tool Company. There he innovated and produced the Tucker Turret used on PT boats, landing craft, the B-17, and the B-29 during World War II. After the war, he turned his attention towards automobiles, his life-long passion.

The Big Three (Ford, GM, and Chrysler) Detroit automakers hadn't developed a new car since 1941. This opened the door for small, independent automakers to produce post-war cars for a starving market. Studebaker, out of Indiana, was the first to produce an entirely new automobile after the war.

But Tucker's vision was to design and build a car with modern styling and safety innovations. He pioneered hydraulic drive systems, fuel injection, direct-drive torque converters, disc brakes, easily accessible instrument panel, padded dashboard, self-sealing tubeless tires, independent springless suspension, laminated windshield, an air-cooled aircraft engine, and a "cyclops" center headlight which would turn when steering around a corner for better visibility while driving at night. The "cyclops" became a fixed headlamp on the production model. There were only fifty Tuckers ever built.

Academy Award winner, Jeff Bridges, played Preston Tucker masterfully in the 1988 movie, Tucker: A Man and His Dream. An interesting aside to the film is that Jeff's father, Lloyd Bridges, played the Michigan senator that kicked the legs out from under the automotive innovator.

I have been fortunate to have seen two "working" Tuckers, and a third fiberglass mock up used in the filming of the movie. One of them is in the Henry Ford Museum, another is in Auburn, Indiana, at their Auburn/Cord/Dussenberg Automobile Museum, and the mock-up used in the movie is at the Ypsilanti Automotive Heritage Museum in Depot Town on E. Cross Street in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

More specifics on Preston Tucker can be found in the link below. He died of lung cancer on December 26th, 1956, at the age of fifty-three. He is buried at Michigan Memorial Park in Flatrock, Michigan.

http://autos.yahoo.com/blogs/motoramic/january-22-preston-tucker-acquitted-fraud-date-1950-151952951.html;_ylt=AkOM9L2H5esPYXIrOL6L.VRQ0.d_;_ylu=X3oDMTRsYm10MWx1BG1pdANCbG9nIEZlYXR1cmVkIFBvc3RzIE1vdG9yYW1pYwRwa2cDZDM5ZWY5M2QtYWEzYS0zMGQ3LWIzOTgtNjVmYjNiNWE0NzRlBHBvcwMxBHNlYwNNZWRpYUJMaXN0TWl4ZWRMUENBVGVtcAR2ZXIDMmZmMDljMzAtNjRhNy0xMWUyLWJmYmYtMGM3YzZjZGUxZDcw;_ylg=X3oDMTFpMm9iMzh1BGludGwDdXMEbGFuZwNlbi11cwRwc3RhaWQDBHBzdGNhdANibG9nBHB0A3NlY3Rpb25z;_ylv=3

http://autos.yahoo.com/blogs/motoramic/january-22-preston-tucker-acquitted-fraud-date-1950-151952951.html;_ylt=AkOM9L2H5esPYXIrOL6L.VRQ0.d_;_ylu=X3oDMTRsYm10MWx1BG1pdANCbG9nIEZlYXR1cmVkIFBvc3RzIE1vdG9yYW1pYwRwa2cDZDM5ZWY5M2QtYWEzYS0zMGQ3LWIzOTgtNjVmYjNiNWE0NzRlBHBvcwMxBHNlYwNNZWRpYUJMaXN0TWl4ZWRMUENBVGVtcAR2ZXIDMmZmMDljMzAtNjRhNy0xMWUyLWJmYmYtMGM3YzZjZGUxZDcw;_ylg=X3oDMTFpMm9iMzh1BGludGwDdXMEbGFuZwNlbi11cwRwc3RhaWQDBHBzdGNhdANibG9nBHB0A3NlY3Rpb25z;_ylv=3

Published on January 27, 2013 00:40

January 22, 2013

The Demise of Kristi Kurtz - November 1990

My girlfriend during the years covering the Washtenaw County coed killings (1967-1969) was Kristi Kurtz. When we met up, she had just dropped out of Eastern Michigan University and managed a small boutique called Stangers near Ned's Bookstore on West Cross Street in Ypsilanti.

My girlfriend during the years covering the Washtenaw County coed killings (1967-1969) was Kristi Kurtz. When we met up, she had just dropped out of Eastern Michigan University and managed a small boutique called Stangers near Ned's Bookstore on West Cross Street in Ypsilanti.I worked part time evenings at the university and took classes during the day. We lived together one block up the street from the boarding house where John Norman Collins lived on 619 Emmet St. and walked past that house daily unsuspecting the eventual notoriety of the place.

Kristi was a vibrant, outspoken, and fiercely independent young woman who found solace in her love of animals. They were the center of her life. Tragedy struck Kristi's young life when her father and mother were killed in a private plane crash. Her father owned a steel company in Detroit and had provided well for his orphaned family. Losing both parents so early in life had a lasting impact on her, and she became more independent because of it.

Kristi and her older sister and brother grew up in Grosse Pointe and were raised by her aunt who kept tight control of the children's trust fund which was sizable. But after Kristi dropped out of college, the money dried up. Kristi wasn't twenty-one and had limited access to her money, so she worked just enough to get by, against the day when she would inherit the money outright.

Kristi liked animals better than people, and she wanted to raise and board horses on a small farm of her own. As soon as she was able, she bought the 113 acre Firesign Farm on Trotters Lane in Webster Township north of Ypsilanti. Kristi set out to live her dream, but I decided that finishing my education was more important than being her horse groom. We parted ways but remained friends. It was a defining moment for both of us.

Twenty years later, I'm living in California, and I get a phone call from a mutual Michigan friend of ours that I hadn't heard from in over ten years. "I've got some tragic news for you," he says. "Kristi's body was found shot to death and discovered buried under some bales of hay in her barn. She's been missing for a month."

It took me a few seconds to wrap my head around what I had just been told, then I heard what few details were known at that time. Two days after Thanksgiving on Saturday, November 24th, 1990, Kristi was last seen by a friend. When Kristi disappeared and hadn't fed her nine horses or other animals for a day or two, her neighbors got worried and contacted Kristi's sister who lived in Colorado. She called the Michigan State Police and filed a missing persons report on Monday, November 26th.

Then on Wednesday, December 26th at 10:15 AM, the day after Christmas, the Good Samaritan neighbor who had been caring for Kristi's horses and dogs, Rick Godfrey, removed another bale of hay to feed the horses, then he recognized her leather boots sticking out. Godfrey had given them to her as a Christmas gift two years before. He moved another bale and saw her frozen, fully clothed body. She had been missing for thirty-two days.

Twice the police had searched the barn with canines but felt the pungent smells confused the dogs. The barn cats had managed to find her body though. Dental records were required for a positive identification.

Check the link for archival news footage about the capture of Kristi Kurtz's murderer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7fnfrk6ZpA

Published on January 22, 2013 20:01

January 21, 2013

Facing Down John Norman Collins - Kristi Kurtz

The tale I'm about to tell really happened. It took over a year for me to contextualize the incident that happened one Sunday evening to me and my then girl friend, Kristi Kurtz, as we were walking to our apartment after visiting friends.

The tale I'm about to tell really happened. It took over a year for me to contextualize the incident that happened one Sunday evening to me and my then girl friend, Kristi Kurtz, as we were walking to our apartment after visiting friends.We stopped at the party (convenience) store on the corner of W. Cross St. and Ballard St, just off of Eastern Michigan University's campus. We bought a small bag of groceries, walked up the street a block, and turned right on Emmet St. heading for College Place where we shared an apartment.

This neighborhood was over a hundred years old and the old growth trees that lined the street provided a natural canopy of added darkness. As Kristi and I casually walked up the street, a car pulled along side us. It was a muggy July evening, and the windows were rolled down revealing three males in the car.

The driver addressed Kristi first saying, "Hey, baby. Want to go out with some real men?" My response was, "Hey, man. She's with me." The next thing I heard was, "Shut the fuck up asshole or the three of us will get out and kick the shit out of you."

Before I could respond, Kristi was impugning their manhood. "What a bunch of dickless wonders!" she scolded the driver. "Three against one, you cowardly faggots." Did I mention that Kristi didn't take crap from anyone and had a mouth on her?

I figured that it might be time for us to drop our groceries and sprint home, but something unexpected happened. Kristi's defiant response seemed to perplex the driver, then out of frustration, he punched the gas pedal and left us in a cloud of screeching tires and stinking exhaust. That was about fifteen or twenty minutes after nine o'clock on the evening of July 30th, 1968.

Although I thought this was an isolated incident, one day I was reading an article about the series of unsolved murders in the Ypsilanti area and focused on the second murder victim, Joan Schell. Suddenly, I was able to connect the dots. Joan had been hitchhiking and had taken a ride with three guys in a black and red, unidentified car less than thirty minutes after Kristi and I had been approached.

A year after John Norman Collins was arrested for the abduction and sex-slaying of Karen Sue Beinemen, Collins ex-housemate, Arnie Davis, testified in open court that he was in the black and red car with Collins that night when they picked up Joan Schell. Then Collins and Schell left him and his twin brother to cruise around town because John said he would drive Joan to Ann Arbor in his car. After that fateful ride, Miss Schell was never seen alive again.

In yet another cruel twist of fate, Kristi Kurtz (41) was found murdered in 1990 during a bungled burglary attempt at her horse farm in Whitmore Lake. More on that story in my next post.

Published on January 21, 2013 10:17

January 16, 2013

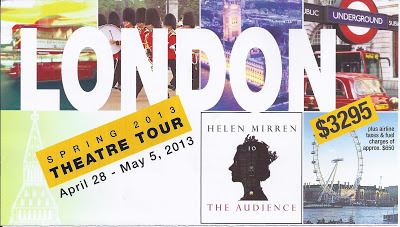

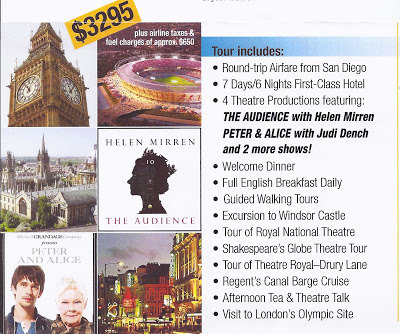

Breakaway London Theater Tour - San Diego's Old Globe Theatre - Spring 2013

For more information callThe Old Globe (619) 231-1941 ext. 2317Email theatretours@theoldglobe.org.

Travel arrangements are flexible.

http://www.theoldglobe.org/?gclid=COzz5tfw7bQCFayPPAodpAQA9A

Published on January 16, 2013 14:09

January 11, 2013

Treading on the Grief of Others in the John Norman Collins Case

It is not easy writing about terrible matters which stir up painful memories and open old wounds. So it is with the Rainy Day Murder cases in Washtenaw County that occurred between the summer of 1967 and the summer of 1969.

If these deaths were matters of private grief, interest would be limited to the family and friends of the deceased, but a lone murderer bent on venting his rage against defenseless young women held two college campuses hostage during his two year reign of terror.

Coeds at The University of Michigan and Eastern Michigan University felt threatened. Parents whose hopes and dreams rested upon the fragile shoulders of their daughters lived in dread of getting a knock on the door from plainclothes policemen with the news that their daughter was the latest victim of the phantom killer.

When a sixteen year old Romulus, Michigan, girl and a local Ypsilanti thirteen year old junior high school student were found murdered only twenty-two days apart, the entire city of Ypsilanti went into panic mode.

The murderer was no longer killing only college girls - every young woman in town was now a potential victim of this at-large killer, and police were no closer to making an arrest than they had been with the murder of the first victim almost two years before.

Only two of the eight families of victims ever had their day in court - the Beinemans in 1970 and the Mixers in 2005. After forty-five years, most of the parents of the victims have gone to their graves never to see justice done on their daughters' killer.

It is a persistent wound carried by the brothers, sisters, cousins, and friends of the victims. But generations further removed from those times want to know the facts about what happened to their relatives and the man accused of killing them.

Comments on John Norman Collins websites show a remarkable lack of misinformation about of these cases. Some people have elevated Collins to the status of a folk hero who was falsely imprisoned for the deeds of another, then scapegoated and railroaded by Washtenaw County law enforcement officials anxious to prosecute this case. When the actual details and facts of these murders are generally known, it is my hope that such people will disabuse themselves of those notions.

Many young people in Ypsilanti and Ann Arbor would like to know more about their history and discover what their grandparents and parents never knew, the full evidence as it exists in the unsolved murders of these six young women.

A debt to history must be paid. The facts of these cases need to be documented and preserved for posterity, so time doesn't swallow up the memory of these young women whose fatal error was not recognizing danger before it was too late.

Soon, the living history of people with knowledge of these cases will be lost. If you can shed some light on these cases, now is the time to come forward. You can contact me confidentially at:

FornologyPO Box 712821Santee, CA 92072-2821

or

gregoryafournier@gmail.com

Part three of three.

Published on January 11, 2013 09:35