Gregory A. Fournier's Blog, page 46

April 14, 2013

Jenny Hilborne - Writer of Mysteries and Psychological Thrillers

I met Jenny Hilborne at a book fair in Solana Beach in April of 2011, when we were sharing a booth and promoting our debut novels. We were both new born to the green wood of publishing.

I met Jenny Hilborne at a book fair in Solana Beach in April of 2011, when we were sharing a booth and promoting our debut novels. We were both new born to the green wood of publishing.Jenny is a Brit from Swindon in Wiltshire, England, who has lived in Southern California for the past fifteen years. She still maintains her roots in England, but she now carries a subdued British accent.

She and I hit it off when I told her the subject of my next writing project, a true crime history of the John Norman Collins murders of 1967-69. This time I would try my hand at non-fiction, and I've been buried by my research ever since.

In the meantime, Jenny had just published Madness and Murder, had No Alibi close to publication, and was planning her third novel, Hide and Seek. She has since completed and published her fourth novel, Stone Cold. She is a virtual writing machine.

So far, most of her novels take place in her favorite city, San Francisco, and people familiar with the City by the Bay will recognize the locales. But Jenny went home to the United Kingdom for six months to do research on Stone Cold to enhance its verisimilitude.

"I didn't want to be stereotyped as only writing about the West Coast," Jen said. "I needed to draw inspiration from home, but it was a challenge getting used to British English again."

Jen says that she enjoyed her research for Stone Cold which got her out of the house and away from her computer screen. While in England, she visited the Cotswolds and Oxfordshire, the settings featured in her latest book.

Check out Jenny's blog: http://jfhilborne.wordpress.com/

Check out her Amazon author page: http://www.amazon.com/Jenny-Hilborne/e/B003YYF5F4/ref=sr_tc_2_0?qid=1365958456&sr=1-2-ent

Published on April 14, 2013 16:17

March 29, 2013

A Bit of Ypsilanti History

Ypsilanti, Michigan is a unique place with a rich history that many residents overlook. Only eight miles east of Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan, Ypsilanti often feels like it is Ann Arbor's poor stepchild.

Prior to World War II, Michigan State Normal School had a quiet, pastoral college campus nestled on the northwest edge of Ypsilanti, surrounded by hundreds of acres of prime farm land and fruit orchards. What was to become Eastern Michigan University was bordered on the north by the Huron River.

Whether as a normal school, a college, or a university, Eastern Michigan has always drawn most of its student body from around the state of Michigan. Eastern's original mission was as a teachers college, but by the nineteen sixties, it became a full-fledged university broadening its scope by offering masters programs in a wide variety of academic areas such as science, business and technology.

Despite this broadened mission, Eastern is still Michigan's largest teacher preparation institution, providing many of the nation's teachers. EMU is proud of the fact that teachers make all of the other professions possible. Think about it!

During the Civil War, The Spanish-American War, and World War I, the United States drew off substantial numbers of able-bodied young men from Michigan's farming communities. Many of them assembled and disembarked from the train station in Depot Town on Ypsilanti's east side.

The Great Depression and World War Two saw many of the area's farms fall into disrepair, with some simply abandoned. Big money was to be made in support of the war effort. The bulk of able-bodied men had already joined the service, leaving a manpower vacuum at The B-24 Liberator bomber plant in Willow Run.

To meet labor needs, the Ford Motor Corporation imported workers from the South and drew additional workers from a previously untapped source, the women of the area. The east side of town soon became a blue collar residential area as it was nearest to the plant.

In the most dramatic demographic shift in the area since the white man drove the red man west, Ypsilanti went from a sunrise-to-sundown farming community to a 24/7 blue collar town.

America changed almost overnight from a rural economy to an urban economy, and soon suburbia would sprawl across the furrowed landscape with the construction of the Federal Interstate Highway System, built during the Eisenhower administration, which changed traffic patterns and hurt the Ypsilanti business community diverting traffic south of town.

Old Ypsilanti runs along Michigan Avenue and comprises the commercial business district. After the Second World War, downtown's fortunes declined. When Ypsilanti had the chance to build a modern shopping center on vacated farm land, the local business community felt it would spell disaster for downtown businesses, and they rejected it. Forward-looking Ann Arbor snapped up the Briarwood development.

During the nineteen sixties, Ypsilanti decided to take some of the War on Poverty money from the Johnson administration's Great Society program and built low-income government housing, known in town as "the projects."

Rather than incorporating these housing units around the city, the decision was made to build them just north of the expressway and south of downtown. This development created a minority isolated community with a legacy of racial division.

In many ways, Ypsilanti is a microcosm of America history. Its fortunes have waxed and waned with those of the country, yet it still survives with pride in its achievements and optimism for a bright future.

In many ways, Ypsilanti is a microcosm of America history. Its fortunes have waxed and waned with those of the country, yet it still survives with pride in its achievements and optimism for a bright future. Recognizing the wealth of historic architecture in their town, The Ypsilanti Heritage Foundation is taking steps to preserve its nineteenth-century homes and restore the area's remaining timber framed barn shells, many of which have been destroyed over the years.

See Ypsi-Ann Trolley post: http://fornology.blogspot.com/2012/01/ypsi-ann-trolley-maybe-whats-old-can-be.html

Ypsilanti Heritage Foundation website: www.yhf.org

Published on March 29, 2013 17:12

March 25, 2013

History of the Lone Ranger: The Movies (3/3)

Clayton Moore and Jay Silverheels reprised their television roles with three full length feature films. The first one was The Ranger Rides Again made in 1955, the last year of filming the television series. The following year in 1956, the film The Lone Ranger came out. Then in 1958, The Lone Ranger and the Lost City of Gold was released. This was the last time the two men worked together on a Lone Ranger project.

In May of 1981, The Legend of the Lone Ranger came out. The copyright owner took out an injunction against Clayton Moore to prevent him from wearing the Lone Ranger trademark mask. The firestorm of bad publicity hurt the film at the box office. Despite massive publicity, the movie lost eleven million dollars.

An authentic Yaqui Native American, Michael Horse, played Tonto, and the masked man was played by newcomer Klinton Spilsbury. Spilsbury had such trouble reading his lines convincingly that actor James Keach was hired to overdub his dialogue for the entire movie.

Legend won three and was nominated for two more Golden Raspberry Awards. It won worst actor, worst new star, and worst musical score. It won honorable mentions for worst picture and worst new song, "The Man in the Mask."

Legend won three and was nominated for two more Golden Raspberry Awards. It won worst actor, worst new star, and worst musical score. It won honorable mentions for worst picture and worst new song, "The Man in the Mask."For thiry years, it was thought that the Masked Crusader of the Old West and his loyal companion Tonto were box office poison. The idea for a new Lone Ranger film knocked around Hollywood for years with nobody willing to pony up the money.

But in May of 2007, Disney Corporation signed on to distribute a Jerry Bruckheimer produced film and plans to release the newest version of The Lone Ranger on July 3, 2013. The movie will star fan favorite Johnny Depp as Tonto, Armie Hammer as the Lone Ranger, and Ruth Wilson as the female lead.

The Lone Ranger rides again!

Check out the trailers for the new movie:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q42DrlOczi0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CAUjV2hGuW4

Published on March 25, 2013 00:00

March 20, 2013

History of The Lone Ranger - On Television - (2/3)

The radio success of The Lone Ranger program was phenomenal. It ran from January 30, 1933, through September 3, 1954, for a total of 2,956 episodes.

The radio success of The Lone Ranger program was phenomenal. It ran from January 30, 1933, through September 3, 1954, for a total of 2,956 episodes. The Lone Ranger brand name was a merchandising bonanza. Soon, novels, comic books, jigsaw puzzles, authentic hats, masks, Western style shirts, and replica twin gun and dual holster sets with silver bullets were available in every toy store in America.

George W. Trendle, founder and general manager of WXYZ Radio in Detroit wanted to bring The Lone Ranger to the new medium of television in 1948.

Brace Beemer had played the title role on radio for eight years and wanted the television part. Trendle felt that Beemer was too long in the tooth and sat too low in the saddle at forty-six years old for the role. Brace didn't have the square jaw and rugged good looks that the role required.

George W. Trendle watched numerous Western and adventure movies and liked Clayton Moore's versatility as an actor. Moore had extensive film, movie serial, and television experience.

The white hat and the black mask would look good on Moore. The Lone Ranger jumped off the small television screen and into America's living rooms on September 15, 1949. In all, there were two-hundred and twenty-one episodes made.

Season three found Clayton Moore sitting out the season because of a contract dispute. Another actor, John Hart, donned the uniform. The mask made the transition to a different actor easier for the audience to accept, but Hart didn't move the same way, nor did his voice match. And something was different about the chemistry between the masked man and Tonto.

The first few episodes with the new Lone Ranger were shot in documentary style with a narrator to ease the transition to the new voice. Hart was generally accepted in the role, but fan favorite, Clayton Moore was back in the saddle for the fourth and fifth season, the only one shot in color.

In addition to a fatter contract, Moore wanted meatier roles to stretch himself as an actor. He liked playing the classic, two-dimensional good guy, but it wasn't enough. To take advantage of his acting ability, Moore began playing dual roles as the Lone Ranger going undercover. Sometimes he was an old prospector or a vagrant of some kind. The character became a master of disguise and infiltrated gangs and outsmarted the bad guys.

No more episodes were made for television after 1955, but the show was so popular with the audience that it managed to hold on to its time slot through the 1957 season.

Through it all, Jay Silverheels, a Mohawk Indian actor, played the role of Tonto, the masked man's trusted companion. The Lone Ranger always used perfect grammar, which may have pleased parents and English teachers, but it didn't seem to make much of an impression on Tonto. The Lone Ranger was his kemo sabe, his trusty scout.

In later years, Jay Silverheels made an appearance on The Tonight Show, with Johnny Carson, and was asked about Tonto's clipped dialogue. He said it bothered him, but that's what the script required, so he read the lines.

When his role as Tonto had run its course, Silverheels played minor supporting roles in the movies and on television into the early 1970s. He enjoyed racing horses in his later years and actively spoke out about the "Uncle Tomahawk" roles Indian actors were forced to play.

Clayton Moore continued to make appearances as the Lone Ranger for the rest of his public life. In 1979, he was banned from wearing the mask at appearances because of a new Lone Ranger movie that was to come out in 1981. The producers took out a court order against the aging but beloved actor. It was a public relations disaster for the film which tanked at the box office.

Clayton Moore continued to make appearances as the Lone Ranger for the rest of his public life. In 1979, he was banned from wearing the mask at appearances because of a new Lone Ranger movie that was to come out in 1981. The producers took out a court order against the aging but beloved actor. It was a public relations disaster for the film which tanked at the box office.Clayton Moore got so much free publicity that he started making appearances in some specially designed Foster-Grant sunglasses and landed a fat endorsement contract. "Who is that man behind those Foster Grants?" began the successful ad campaign.

His commercials aired repeatedly which delighted fans, proving that you can't keep a good man down. In 1984, the court order was lifted and Moore could once again wear the mask while making appearances. By the 1990s, Clayton Moore retired from public life.

Next Post: History of the Lone Ranger - The Movies

Jay Thomas tells a funny story about Clayton Moore on the David Letterman Show: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KFabfnfhIaY

Published on March 20, 2013 13:50

March 16, 2013

History of The Lone Ranger - The Radio Years - (1/3)

"The Lone Ranger! "Hi Yo Silver!"

"The Lone Ranger! "Hi Yo Silver!" "A fiery horse with the speed of light, a cloud of dust and a hearty "Hi Yo Silver!" The Lone Ranger. "Hi Yo Silver, away!" With his faithful Indian companion Tonto, the daring and resourceful masked rider of the plains, led the fight for law and order in the early west. Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear. The Lone Ranger rides again!" Baby Boomers everywhere will remember those rousing words recited over Rossini's classical music The William Tell Overture. The television version of the masked man hit the small screen in a big way, but the character was already well-established on a radio show first broadcast from Detroit three times a week from WXYZ radio in 1933. Fran Striker was the creator of the character, George W. Trendle was the producer of the show, and Earl W. Graser was the first Lone Ranger on the radio. Graser had a deep, authoritive, vibrant voice that sounded much older than his thirty-two years. On his way home from rehearsals at the station on April 8, 1941, he fell asleep at the wheel and veered into a parked trailer silencing one of America's most popular radio voices. He had been on the air as the Lone Ranger for eight years. The show was scheduled to air the next night, but who would take over the role? Trendle had to find someone fast. Mike Wallace might work. He would become a journalist on Sixty Minutes decades later, and he was presently the narrator on the popular The Green Hornet program at WXYZ. Mike Wallace was available, but he had questionable acting ability. It was decided that Brace Beemer, who narrated The Lone Ranger, was their best choice on short notice. He had already been doing publicity photos for The Lone Ranger, and now he could make public appearances around the Detroit area as well. Best of all, Beemer's voice was similar to Graser's with a slight headcold. Good enough! To ease the transition for listeners, the masked man would be wounded for the next few episodes and speak with a weak, raspy voice. Brace Beemer was an excellent front man for the program. He was six-foot tall, handsome, and an excellent horseman. He had no problem booming out "Hi-Yo, Silver"during the program, but he couldn't handle the ending when he had to say "Hi-Yo, Silver, away." It didn't sound right to Trendle or the sound engineers, so they inserted a recording of Graser saying the line at the end of the program. In a 1944 radio poll, The Lone Ranger placed number one in popularity. In all, there were 2,956 radio episodes made. Part Two: The Lone Ranger Comes to Television Original TV episode on Hulu: http://www.hulu.com/watch/84787

Published on March 16, 2013 16:48

March 13, 2013

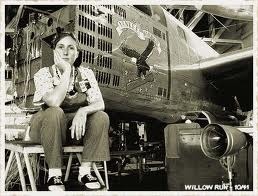

Rosie the Riveter - Happy Women's History Month, Ladies

In honor of all the Rosies who stepped up to fill the work shoes of the men in uniform. America would never be the same nor would these women.

I love this link. I hope you do also:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9GarCzR_6Ng&feature=em-share_video_user

Published on March 13, 2013 07:41

March 9, 2013

Willow Run Bomber Plant Changes Ypsilanti Forever

Depot Town Today

Depot Town TodayAt the turn of the century, before the second World War, Ypsilanti had an active downtown area along Michigan Avenue. Northeast of town, there was a thriving business district called Depot Town.

Depot Town was the area's commercial hub and provided services for weary train travelers. Ypsilanti's three-story brick depot station was ornate next to the depot in Ann Arbor.

The Norris Building built in 1861 was supposed to house a retail block on the ground floor and residential rooms on the two upper floors. Instead, the building became an army barracks during the Civil War. The 14th Michigan Infantry Regiment shipped out of Depot Town in 1862, as did the 27th Michigan Regiment in 1863.

The facade of the historic Norris Building remains on N. River St., despite a recent fire which decimated the rear portion of this, the last remaining Civil War barracks in the state.

Michigan State Normal School to the northwest of downtown spawned a growing educational center, which later expanded its mission and became Eastern Michigan University. Ypsilanti's residential area with its historic and varied architecture filled the spaces in between. Surrounding everything was some of the most fertile farm land in the state of Michigan.

The water powered age of nineteenth century manufacturing on the Huron River gave way to the modern electrical age of the twentieth century. The soft beauty of the gas light to illuminate homes was replaced with the glare of the incandescent light bulb. The times were changing for Ypsilanti - ready or not.

***

The countryside was prime tillable ground with fruit groves scattered about the county. Henry Ford owned a large tract of land in an area known as Willow Run named for the small river that ran through it.

The Ford patriarch wanted to plant soybeans on the land, but the United States government needed bombers for the Lend Lease program with Britain. On December 8, 1941, the Nazis declared war on the United States on behalf of the Japanese. We were at war.

The Roosevelt administration asked the Ford corporation, now run by Edsel Ford, to build a factory that could mass produce the B-24 Liberator Bomber. Edsel Ford, Charles Sorenson (production manager), and some Ford engineers visited the Consolidated Aircraft Company in San Diego to see how the planes were built.

That night, Sorenson drew up a floor plan that could build the bomber more efficiently. His blueprint was a marvel of ingenuity, but the Ford corporation made one significant change in his master plan.

The best shape to build a front to back, assembly line operation is in a straight line.

The best shape to build a front to back, assembly line operation is in a straight line. But to avoid the higher taxes in Democratic Wayne County, the bomber plant took a hard right to the south on one end to stay within Republican Washtenaw County, which had lower taxes.

The construction of the plant in Willow Run began in May of 1941, seven months before Pearl Harbor. Detroit architect Albert Kahn designed the largest factory in the world, but it would be his last project. He died in 1942.

The federal government bought up land adjacent to the bomber plant and built an airport which still exists today and is used for commercial aviation. The eight-sectioned hangar could house twenty Liberators.

***Soon, workers flooded into Ypsilanti and the rapidly developing Willow Run area where makeshift row housing was hastily constructed. Overnight, the sleepy farming and university town of Ypsilanti became a three shift, 24 hour, blue collar community.

Many people in Ypsilanti rented rooms in their homes to workers or converted their large Victorian homes into boarding houses. It was wartime; money was to be made.

Some families rented "warm beds." One worker would sleep in the bed while another was working his shift, but still there was a housing shortage. Some people slept in their cars until they could make other arrangements.

Ford sent recruiters to Kentucky and Tennessee to draw workers in from the south. That's where the derisive term "Ypsitucky" originated. Long time residents didn't like the changes they saw in their town. The bomber factory workers worked hard and drank hard. Fights broke out in local bars, and Ypsilanti was developing a hard edge and a dark reputation.

Because so many men were in uniform serving their country, there was a shortage of skilled labor, at first. But then the women of Southern Michigan stepped up big time. They donned work clothes, and tied up their long hair in colorful scarves. It was calculated at the end of the war that 40% of every B-24 Liberator was assembled by women. (Happy National Women's Month, Ladies)

Because so many men were in uniform serving their country, there was a shortage of skilled labor, at first. But then the women of Southern Michigan stepped up big time. They donned work clothes, and tied up their long hair in colorful scarves. It was calculated at the end of the war that 40% of every B-24 Liberator was assembled by women. (Happy National Women's Month, Ladies)***

Little known factoid: The first stretch of expressway in America was made with Ford steel and Ford cement. It connected workers in the Detroit area to their jobs at the bomber plant in Willow Run via Ecorse Road. It's still there and runs along the north end of the GM Hydromatic Plant and Willow Run Airport.

***

The following link has some vintage bomber plant footage.

http://www.annarbor.com/news/ypsilanti/pbs-to-air-documentary-about-ypsilantis-legendary-willow-run-b-24-bomber-factory/

Published on March 09, 2013 16:19

March 5, 2013

Ypsilanti, Michigan: EMU - The Turbulent Sixties

On October 20, 1960, presidential candidate John F. Kennedy's motorcade was stopped at about 1:10 AM by Eastern Michigan University students who jammed W. Cross St in front of McKinney Student Union. Kennedy was on his way to a political rally in Ann Arbor the following day.

On October 20, 1960, presidential candidate John F. Kennedy's motorcade was stopped at about 1:10 AM by Eastern Michigan University students who jammed W. Cross St in front of McKinney Student Union. Kennedy was on his way to a political rally in Ann Arbor the following day.He made a two or three minute speech telling the cheering crowd of students that he stood "for the oldest party in years, but the youngest party in ideas." Because of the late hour, President Kennedy asked to be excused explaining he had a difficult schedule planned for the next day.

In his inaugural speech on January 20, 1960, the new president boldly stated that "a torch has been passed to a new generation." Three years later, on Friday, November 22, 1963, at 11:30 AM, an assassin's bullets cut down President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas, while he was campaigning for a second term. He was pronounced dead on the operating table thirty minutes later.

In his inaugural speech on January 20, 1960, the new president boldly stated that "a torch has been passed to a new generation." Three years later, on Friday, November 22, 1963, at 11:30 AM, an assassin's bullets cut down President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas, while he was campaigning for a second term. He was pronounced dead on the operating table thirty minutes later.At 1:00 PM, the intercom system at Allen Park High School broadcast the sound of Walter Cronkite making the announcement that John F. Kennedy, thirty-fifth president of the United States was dead, then he paused. The principal came on and asked for a moment of silence.

I was in sophomore biology class. The shocked silence was punctuated first by wimpering and then open sobbing. This was a defining moment for an entire generation. A mourning wind swept over the nation and the world held its breath.

Two years, ten months, two days, and sixty-nine minutes. That's how long Kennedy held office. His torch of optimism had been extinguished.

***

The President's younger brother, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, made the trip to Eastern's campus on Saturday, October 29, 1966. He made a brief speech in support of Michigan Democratic candidates to 3,000 cheering students gathered on the steps of Pease Auditorium. He too was on his way to an Ann Arbor political rally.

The President's younger brother, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, made the trip to Eastern's campus on Saturday, October 29, 1966. He made a brief speech in support of Michigan Democratic candidates to 3,000 cheering students gathered on the steps of Pease Auditorium. He too was on his way to an Ann Arbor political rally. Less than two years later on June 6, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy met the same fate as his brother after a political rally in Los Angeles, California. What was going on in America?

***

The nineteen sixties were a troubled time for our country. Vietnam and the Cold War were international issues, but Civil Rights was a national issue that hit home with explosive force. The United States began to tear itself apart from the inside over domestic issues.

Megar Evers was shot down in Jackson, Mississippi, on March 25, 1965; Malcolm X met his violent end on February 21, 1965; Viola Liuzzo (Freedom Rider and mother of five) was shot twice in the head while driving her car in Lowndes County, Alabama, on March 25, 1965; and Martin Luther King was murdered by sniper James Earl Ray in Memphis, Tennessee, on February 21, 1968.

After the murder of Dr. King, urban riots began to break out across America. By the decade's end, growing protests against the Vietnam War rocked every university campus in America.

When Americans watched the live television coverage of the political rioting at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, the nation became cynical about where America was heading.

American had become a seething cauldron of political and social upheaval. Even on the basic family level, the politics of college aged children were usually different from the politics of their more conservative parents. The term "generation gap" was born. Anti-establishment fervor had not been so pronounced in the United States since the Civil War.

***

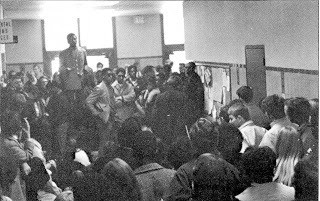

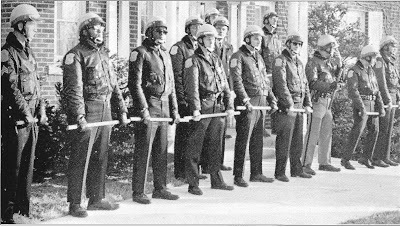

On Thursday, February 20, 1969, students at Eastern Michigan staged a sit-in protest at Pierce Hall, EMU's administration building. The issues were social concerns like race, poverty, equal rights, and peace.

Eastern Michigan's president, Harold Sponberg called the County Sheriff and asked him to clear the protesters out of his building. While that was being staged, the first floor corridor of Pierce Hall was thick with students.

At the time, I was a junior majoring in English Language and Composition. I was also a volunteer reporter for the campus underground newspaper, The Second Coming, published by Frank Michels. Frank was a journalism major who was thrown out of Eastern Michigan on the charge of inciting student unrest on campus.

On the late afternoon in question, I was in Pierce Hall reporting on the sit-in protest. Several people were trying to get the crowd worked up, but it was a weak effort.

Then, a black guy no one had ever seen before wearing a red Sergeant Pepper jacket, stood on a chair near me and held up a lighter and struck it. He started saying "Burn, baby, burn." A couple of white students in the crowd began to heckle the would be fire starter and the lighter was put away.

I left the standoff in the corridor to see what was going on outside the building. Some students were milling around but not in great numbers. That's when the police moved it. In full riot gear, the county cops cleared and secured the building and broke up the protest demonstration without major incident. The Michigan State Police were called in to surround and protect President Sponberg's home. And that was how it ended, almost as quickly as it began.

Fifteen months later in May of 1970, campuses around the country erupted when it was discovered that President Nixon secretly ordered troops into Cambodia and Laos. This time, Eastern's students protested in large numbers and were more impassioned and aggressive, though most of the protesters were peaceful and held back from the fray.

As night fell, the crowd was getting progressively more unruly. An EMU Ford Econoline van was pushed onto Forest St. from the back of McKinney Union. It was turned over by a group of male rowdies to block the street. Someone took apart a traffic barricade and several of the guys took the wooden cross member and ran it through the windshield of the van. Now, it was game on with the police.

The Washtenaw County police drove a police bus full of riot clad officers onto Forest Ave. They jumped out to confront and arrest the protesters.

The same bus was used as a makeshift paddy wagon. One of the more vocal and violent protesters to be arrested was not an Eastern student, but someone known by police as an "outside agitator." He was one of the leaders of the demonstration.

He put up quite a fight before he was apprehended and thrown into the bus. He went to the back of the bus and kicked out the emergency back window and escaped with many others.

As he fled north through the darkened campus area, he hurled several large rocks through the windows of some buildings along the way before he vanished into the shadows. This I witnessed myself.

Flying above the turmoil, Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas Harvey threw tear gas bombs from a helicopter onto the crowd. Not long after that, the protest demonstration ended.

When I interviewed Sheriff Harvey last summer for the book I'm writing on John Norman Collins, he told me the helicopter story. I mentioned to the former sheriff that I got a whiff of his tear gas that night. He told me he's heard that from lots of people, and we both laughed. Though at the time, it didn't seem that funny.

Published on March 05, 2013 19:45

March 1, 2013

Ypsilanti, Michigan - Coming of Age

A cholera outbreak in Detroit in 1832 prompted the Michigan legislature to pass an ordinance to prevent immigrants or travelers from spreading the disease throughout the territory. The overprotective frontier nature of the Ypsilanti residents gave the village the reputation of being a dangerous and fearful place to be if you weren’t a local. No one died of cholera that year in Ypsilanti, and the impression persists that the residents of the area are proud of their cantankerous frontier past.

When a wave of lawlessness and terror swept through Ypsilanti in the late 1830’s, a vigilante committee was formed to clean up the village. Secret meetings were held at different locations monthly, and by all accounts, they did an impressive job. “By the end of 1839, one-hundred and twelve men had been convicted of crimes, hundreds of dollars in stolen goods were recovered, and many undesirables were asked to leave town.”

When a wave of lawlessness and terror swept through Ypsilanti in the late 1830’s, a vigilante committee was formed to clean up the village. Secret meetings were held at different locations monthly, and by all accounts, they did an impressive job. “By the end of 1839, one-hundred and twelve men had been convicted of crimes, hundreds of dollars in stolen goods were recovered, and many undesirables were asked to leave town.”Ten years later, ground was broken on a three storied structure that became the first building of the Michigan State Normal College which later became Eastern Michigan University. The first term began with 122 students in 1853. Males had to be eighteen and females had to be sixteen. A statement of intent to teach in a Michigan school had to be signed by every student.

Michigan State Normal College was the first teacher training school west of the Alleghenies and was, for fifty years, the only “normal” college in Michigan. As it grew, it became Eastern Michigan College in 1956, but by 1959, Eastern had been granted university status by the state legislature because of its widening educational mission.

The signature landmark in Ypsilanti has long

The signature landmark in Ypsilanti has long been The Water Tower built on the town’s

highest point several hundred feet above

sea level. Built in 1889-1890, it is a limestone

clad, elevated reservoir that once was topped by

an octagonal cupola, removed in 1906 due to

fears of strong winds hurling it 147 feet below.

The Water Tower is located on a small triangular patch of land that

stands opposite Eastern Michigan University’s McKinney Student

Union building on the southwestern edge of the campus.

On a frigid January day in nineteen sixty, John F. Kennedy

metaphorically passed a torch to a new generation in his

inaugural speech. Little did the new President know what history

had in store for America by decade's end.

It was a tough decade that polarized the nation like nothing else had

since the Civil War. It was the age of the Vietnam War, political

assassinations, the Civil Rights movement, urban riots, the

Black Panthers, the draft, and the heyday of the Cold War.

Is it any wonder that by the end of the decade university campuses

all over America felt the dissonant chords of political dissent and

civil disobedience? The campuses of Eastern Michigan University

and The University of Michigan were no exceptions.

Next post: Ypsilanti, Michigan - The Turbulent Sixties

Published on March 01, 2013 07:33

February 24, 2013

Ypsilanti, Michigan - The Frontier Years

Demetrius YpsilantiThe Huron River Valley has been a thoroughfare for humans since ancient Native Americans used the river for their transportation and their village sites. A main trail from the big river to the east, which the French called “de troit” (the strait), led west along the Huron River where it crossed over at a narrows and led into the thick, game rich forests which the local Indians called home for many generations. The spot was the crossroads for several Indian tribes, primarily the Huron, the Ottawa, and the Pottawatomie.

Demetrius YpsilantiThe Huron River Valley has been a thoroughfare for humans since ancient Native Americans used the river for their transportation and their village sites. A main trail from the big river to the east, which the French called “de troit” (the strait), led west along the Huron River where it crossed over at a narrows and led into the thick, game rich forests which the local Indians called home for many generations. The spot was the crossroads for several Indian tribes, primarily the Huron, the Ottawa, and the Pottawatomie.Ypsilanti began its pioneering life in 1809 at the edge of the frontier known as The Michigan Territory. Three enterprising Frenchmen opened a trading post known as “Godfrey’s on the Pottawatomie Trail,” where the Indian trail crossed the narrows in the river. They traded gun power and other French goods to the local Indians for beaver pelts and other Indian products from the forest. When the Indians began to feel the squeeze of frontier civilization in the form of treaties pushing them westward, the traders followed them and left their trading post in ruins.

Ten years later in 1819, General Lewis Cass, the governor of the Michigan Territory, signed the Treaty of Saginaw. What was to become Washtenaw County passed out of the hands of the local tribes and into the hands of the Territory. In 1823, a full-fledged settlement called Woodruff’s Grove was established, and in 1825, the territorial government commissioned the surveying of a road linking Detroit and Chicago.

The surveyor, Mr. Orange Risdon, found the job an easy one. Over many generations, the local Indians had blazed the most convenient trail west - the old Indian trail from Detroit.

Judge WoodwardThree Detroit businessmen, the most notable of whom was Federal Judge Augustus Brevoort Woodward, purchased the original French Claims from the families of the original deed holders and plotted out a village as soon as the Chicago Road, later known as Michigan Avenue, was surveyed.

Judge WoodwardThree Detroit businessmen, the most notable of whom was Federal Judge Augustus Brevoort Woodward, purchased the original French Claims from the families of the original deed holders and plotted out a village as soon as the Chicago Road, later known as Michigan Avenue, was surveyed. The judge loved history and anything Greek it was said. Americans of that era were interested reading in their newspapers about the War of Greek Independence, as the United States had only fifty years before gained its independence from England.

A courageous Greek general, Demetrius Ypsilanti (1793-1832), held the Citadel of Argos with only 300 men against a Turkish army of 30,000 men. When their supplies ran out, General Demetrius Ypsilanti and his men escaped without losing a single man. He became an international figure of his time.

Woodward wanted to name this new town after his hero -Ypsilanti - much to the chagrin of his co-investors. They wanted the town’s name to reflect the area’s easy access to water power from the Huron River, so they proposed names like Waterville and Watertown.

But Judge Woodward had a forceful, dominate personality, and he was the lead investor with the highest public profile, so he got his way. The town has been known as Ypsilanti ever since – the only city in America with this distinctive name.

Next post: Ypsilanti, Michigan - Coming of Age

Published on February 24, 2013 14:54