Randy Alcorn's Blog, page 35

September 20, 2023

How to Talk with Our Children and Grandchildren About Transgender Ideology

Note from Randy: I appreciate this guest article, sixth in our series on gender confusion, written by Josh Glaser (executive director of Regeneration, a ministry that helps men, women, and families learn and live God’s design for sexuality) and Paula Rinehart (a therapist in Raleigh, North Carolina) for The Gospel Coalition. They provide some excellent suggestions about how parents (and grandparents) can talk to the children in their lives about transgender and identity issues.

These are tough issues, and they’re not going away. God’s people need all the help we can get. The more we speak to these issues with grace and truth, not just one or the other, the better we represent Jesus and the gospel. We should never heap guilt on someone experiencing gender confusion; instead, we should listen and care lovingly and genuinely for them, and recognize we too are confused about aspects of our life and identity. All of us need to look to the God who created us as He did for a glorious reason.

Our kids need to see that the truth is not in what the world serves up to us about sex and gender. Rather, the truth is in Jesus, as revealed in God’s Word.

(For further reading for parents, I also recommend Mama Bear Apologetics Guide to Sexuality: Empowering Your Kids to Understand and Live Out God’s Design by Hillary Morgan Ferrer and Amy Davison, both strong believers and good writers.)

How to Talk with Your Kids About Transgender Ideology

By Josh Glaser and Paula Rinehart

Last spring, of de-transitioning made waves. Helena detailed what lured her into gender transition—and how she got out. She had felt insecure about her body and was struggling with an eating disorder. She became estranged from friends and family. A few clicks on Google opened her up to an online community ready to welcome and accept her. Eventually, she recognized that questioning her gender identity elevated her online social status even more. She changed how she dressed and started binding her chest, and when she turned 18, she began taking high doses of testosterone.

Through all this, the refrain she heard from social workers, psychologists, and friends was that gender transition would eventually make her depression disappear. Helena , however, that the real result was “an even wider disconnect from understanding the conditions that led me to feel such sadness, fear, and grief.”

As parents, how many of our kids could voice the same insecurities and struggles Helena had? Now imagine that when your child felt these things, someone promised her that gender transition would let her trade awkward loneliness for belonging? Can you feel the pull? Our kids are particularly vulnerable at this stage in life, at this time in history. What can we do?

Questions of gender and sexuality are ubiquitous in the social universe of today’s teens. Whether through social media, classroom instruction, or friends’ stories, it’s a firehose of the same fallacy: The core of your identity is your gender identity. You create you.

The question for Christian parents is not whether but how to talk about transgender ideology with our kids. We want to suggest three specific ways parents can counter bad ideas that might be shaping their children’s understanding of gender.

1. Normalize growing-up struggles.

Current gender ideology worms its way into our children’s psyches by amplifying and exploiting the struggles most kids experience growing up (and mercifully, tend to forget).

As parents, we can help our kids by taking seriously any signs of anxiety, depression, loneliness, or self-harm. This generation is experiencing mental health issues at alarming rates, and they need our attention, time, and intervention—but not the false promise that all their pain will disappear if they can just pass as the other sex.

Our kids also need reassurance that their experiences of insecurity, body discomfort, and social awkwardness during adolescence are normal for most kids everywhere. Parents should often say, “You’re not the only one. I remember feeling similarly. This is how life looks at 15. It will get better, I promise.”

Share vulnerable stories with your kids about when your friends laughed at you, or your parents argued incessantly, or the boy you kind of liked preferred your best friend, or how you looked in the mirror and wished you saw someone different.

We tend to lose hope if we think a problem will never change. Children and adolescents have notoriously short horizons. Kids need help to see that God makes a new path out of what seems like a dead end.

Finally, our kids need to know that if they’re feeling at odds with their gender (gender dysphoria), this resolves by itself over time for the vast majority of people. The discomfort fades. We grow into a bodily reality of feeling at home as the woman or man we are. Resorting to puberty blockers is like shooting your foot off because it’s hard to train for a race.

2. Celebrate gender.

Gender ideology (remaking the human body to comply with what one feels) is empty of real substance. It’s built on stilts. The detachment of “gender” from biology has led to a place where anyone can “be” a man or a woman simply by asserting they are. Is that a desirable world?

As Christian parents, we have a much more satisfying story on gender. Our faith brings body and soul together in an integrated life. Where “gender identity” splits a “person” from his or her body, Christianity insists your body has meaning and purpose as an integral part of how you bear God’s image (Gen. 1:27). Humanity’s sexed (male or female) biology is intentionally designed to reveal the goodness of God. We should underline this reality over and over with our kids.

There’s much more to be said here, but these are breadcrumbs on the trail leading us to a glorious mystery: Jesus is our Bridegroom and we are the Bride he loves. God designed our bodies to mean something not only biologically but also theologically. Rightly understood, our maleness and femaleness whisper to us of the gospel.

From this backdrop, in age-appropriate ways, we can weave God’s design of gender into ordinary conversation. We might ask questions like the following:

How do your mom and dad look and sound different to you? How do they feel different to you?

What do you love about being a boy or being a girl?

What unique things do you tend to notice about females and males, and how do their differences complement one another?

What’s one thing males and females can do together that a group of males or a group of females cannot do without the other sex?

These simple conversations can open doors to celebrate gender differences, with no implication of greater or lesser value. Other times, they provide the chance to refute the stereotypes gender-change activists use to suggest a child is in the wrong body. If a girl loves to climb trees and a boy loves to dance, it doesn’t mean the girl should become a boy or vice versa. It simply means you’re a girl who climbs trees, and you’re a boy who loves to dance. As Nancy Pearcey suggests, reject the stereotypes, not your body.

As your children approach adolescence, talk to them about romantic desire, marriage and sex, and procreation as a natural telos of sex. If you don’t, Google, TikTok, teachers, and friends will take the leading roles in shaping your child’s perceptions. Here are a few among many possibilities for conversation starters:

What kinds of things does a girl appreciate in a guy because he’s different from her? What draws a guy to a girl because she brings something unlike him?

When a man and woman marry, they pledge their lives to each other. What does this say to you about God’s covenant love for us? (See Isa. 62:5; Hos. 2:19, 20; Rev. 19:7.) How is this different from the way many approach love relationships today?

Birth control and other contraceptive technologies have created a modern culture where sex is distanced from—or even set in opposition to—a beautiful outcome for which God designed sex: having babies. Today’s culture often sees pregnancy after sex as an unwanted surprise or “problem.” Isn’t this odd? How does the biblical call to “be fruitful and multiply” (Gen. 1:28) illuminate the meaning of why God created “male and female” (Gen. 1:27)?

Getting our kids (and perhaps ourselves) to think deeply about these things is important because today’s gender ideology offers an alternative gospel. Our kids feel the longing felt by everyone since the fall—the longing for resurrection and connection. Believe and receive a new name, a new identity, a new body, a new and loving community. Transgender ideology offers this “good news” to our kids, but it cannot deliver.

3. Connect kindness and truth.

Proverbs 3:3 pairs kindness with truth in this way: “Do not let kindness and truth leave you” (NASB). It’s a relevant pairing today, in part because Gen Z doesn’t hear truth well unless the truth is framed in kindness. In their conversations with friends, compassion generally means unconditional affirmation: “You do you.” Empathy is the prevailing virtue. As the popular yard sign declares, “Kindness is everything.”

As a father of teenagers, I (Josh) missed this for a long time. In conversations with my kids, I tried to frame truth first and then season it with compassion. But a youth pastor friend helped me see that for this generation, truth doesn’t ring true if it doesn’t sound kind. Now, I’m learning to start with kindness, followed by how God’s truth leads to greater kindness. Some examples include the following:

Studies show most kids with gender dysphoria outgrow it, but today’s culture pushes kids to treat being trans as permanent. Isn’t it cruel to force kids into a box they aren’t allowed to escape?

I’m sorry to hear about your classmate’s depression. That’s so hard. He needs people who will take time to uncover the deeper roots of his struggles because gender transition usually doesn’t improve those symptoms.

How can we help people who are dissatisfied with their gender in ways that will provide lasting benefits and won’t permanently damage their bodies?

How do you think it feels for a female swimmer who has trained her whole life and risen to the highest levels of competition to have to compete against a biological male who identifies as a woman yet has a male physique?

I try to share one clear thought and then quietly step back (teenagers need time to mull things over). Then later I look for another opening to pick up the conversation or ask more questions.

Know Who Else Has Their Ear

While we Christian parents should seek opportunities to initiate conversations about gender with our kids, we also need to know who else has their ear. Helena Kirschner is just one of a growing number who have exposed how enticing and aggressive pro-trans influencers are online, especially for teenagers.

In an earlier interview with Rod Dreher, Kirschner makes the point that parents ask lots of questions when a child wants to go to a sleepover. Where is it? Who will be there? But a child can be sitting in the same room with a parent, chatting online with a stranger suggesting puberty blockers and cross sex hormones, and the parent is completely unaware. Helena begs the question, do you know where your children are?

Perhaps that’s the real point of stepping into regular conversation around gender with your children. It’s vital to know where their minds are, what cracks in their armor make them vulnerable to gender ideology. But more positively, you want to give your kids a vision for becoming someone whose deepest identity is rooted in the strong and beautiful reality of being created in the image of God, male or female.

The article originally appeared on the Gospel Coalition , and is used with permission.

Photo: Unsplash

September 18, 2023

The Social Contagion Targeting Girls, and What Parents Can Do to Protect Their Children

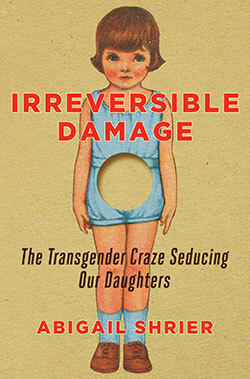

Note from Randy: This fifth article in our series on gender confusion is an important and sobering book review written by Al Stewart (National Director of the Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches in Australia). He does a good job of summarizing the key points from Irreversible Damage: Teenage Girls and the Transgender Craze by Abigail Shrier. Although her book isn’t presented from a Christian worldview, it helps us understand the social contagion of transgenderism that is hurting many young people around the world.

These statistics and facts are hard to read. But unless we understand the magnitude of the issues our children and grandchildren face, we can’t respond with wisdom and counteract the lies with God’s truth. Paul says, “We demolish arguments and every pretension that sets itself up against the knowledge of God, and we take captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5). As I’ve often said about abortion—and I believe is also true of transgenderism—we are not dealing here with “one more social issue,” but a unique and focused evil in which Satan has deeply vested interests. This is another example of how the evil one has a special hatred of children, and in this case, targets them with gender confusion. He wants to kill them, and he lies to facilitate and cover his attempts to destroy them.

Consider watching these stories, produced by Independent Women’s Forum, of women who have detransitioned. All of them are heartbreaking in their own way, and some are hard to watch as they do show the results of life-altering surgeries. Watch them at your own discretion, but I share them because it is better that someone should be repulsed by evil than indifferent to or drawn to it.

Here is Daisy Strongin’s story:

Only the light of God’s truth can set us free (John 8:32). May we speak the truth in love to a lost and increasingly confused, disoriented, and deceived generation. (Remember, to shine with His light, we must first allow Him daily to shine His light upon us.)

Review: Irreversible Damage by Abigail Shrier

By Al Stewart

A decade ago, the number of people in the USA identifying as transgender was approx. 1 in 10,000, now 2% of high school students, identify as transgender. (See page 32)

This is a troubling book about an epidemic damaging the lives of many, many teenage girls. While the book is particularly focused on the United States, this contagion, spread by the internet, is beginning to affect many westernized societies.

Abigail Shrier is a journalist who writes for the Wall Street Journal. She paints a grim picture:

of depressed and anxious adolescent girls at vulnerable stages in their life;

of influencers who use the internet to spread what is effectively a cult;

of damaging responses to mental health problems;

of weak and woke counsellors who are not the gatekeepers they should be;

of educators who have allowed activists ongoing access to school children;

of morally weak or incompetent, or simply greedy surgeons making money from this epidemic regardless of the human cost; and

of desperate parents looking for help to try and work out how to rescue their adolescent girls from this self-destructive behaviour.

It’s a book so thoroughly researched and so carefully explaining the problem and the damage done, that it’s hard to believe the book has been opposed, cancelled, or made unavailable through various retailers even before it was published. Even the suggestion of publishing this book was met with howls of transphobia and warnings that it would promote suicide among trans people. It is interesting to notice that Shrier is not at all anti-trans for those who are of age and make their adult decisions. Her point is that this is a contagion among adolescent girls and the long-term and “irreversible damage” is significant.

It’s a book so thoroughly researched and so carefully explaining the problem and the damage done, that it’s hard to believe the book has been opposed, cancelled, or made unavailable through various retailers even before it was published. Even the suggestion of publishing this book was met with howls of transphobia and warnings that it would promote suicide among trans people. It is interesting to notice that Shrier is not at all anti-trans for those who are of age and make their adult decisions. Her point is that this is a contagion among adolescent girls and the long-term and “irreversible damage” is significant.

I’ll walk you through some of the material, but it’s well worth reading this book yourself—particularly if you’re involved in any kind of pastoral work or have a family with teenage girls.

The New Social Contagion

Shrier names it “rapid onset gender dysphoria,”—the phenomenon where girls begin to identify as “trans” in friendship groups or clusters, even though there was no sign of gender dysphoria earlier in their lives.

Shrier explains how “gender dysphoria,” formerly known as “gender identity disorder,” is characterised by severe persistent discomfort in one’s biological sex. It typically begins in early childhood—ages two to four—though it may become more severe in adolescence. But in most cases—nearly 70%—childhood gender dysphoria resolves, i.e. the person grows out of it.

Historically, gender dysphoria afflicted a tiny sliver of the population (roughly 0.01%) and almost exclusively boys. Before 2012, in fact, there was no scientific literature on girls aged 11 to 21 ever having developed gender dysphoria at all. This means that prior to 2012, the gender dysphoria rates were approximately 1 in 10,000 people. And almost never in girls (page xxvii).

And yet …

Between 2016 and 2017, a number of gender surgeries for natal females in the U.S. quadrupled with biological women suddenly accounting for, as we have seen, 70% of all gender surgeries. In 2018, the UK reported 4400% rise over the previous decade in teenage girls seeking gender treatment. In Canada, Sweden, Finland, and the UK, clinicians and gender therapists began reporting a sudden and dramatic shift in the demographics of those presenting with gender dysphoria from predominantly school-aged boys to predominantly adolescent girls. (Page 26)

Groups of friends together are now presenting as trans and wanting to transition to live as trans men. Shrier interviews Dr Lisa Littman, whose research has found that the contagion spreads more like anorexia nervosa:

Like the new crop of transgender teens, anorexic girls suffered from an obsessive focus on the perceived flaws of their bodies and valorized the willingness to self-harm. (Page 33)

Under the Influence

Shrier then explains how female-to-male influencers with huge followings (especially on YouTube) have been presenting gender transition as a liberating answer to whatever mental problems or anxieties a particular adolescent female has. If you’re feeling depressed, anxious, sad, unhappy with your body, then you must be trans. Shrier lists some of the working hypotheses that are drip-fed into the heads of adolescent females by these influencers:

If you think you might be trans, you are.

You should try it out—a binder for the breasts is the way to start.

Testosterone is amazing. It will solve all your problems.

If your parents loved you, they would support your trans identity.

If you’re not supported in your trans identity, you’ll probably kill yourself (a threat that is also used as a “gun to the head” to pull parents into line).

Deceiving parents and doctors is justified if it helps in transition.

You don’t have to identify as the opposite sex to be trans.

Much of this messaging has happened with the support of schools and teachers. One of the most troubling chapters describes how the gatekeepers of education have allowed gender activists access to schools—and even kindergartens—to promote radical gender ideology under the pretext of resisting bullying.

Meanwhile, many mental health experts have abdicated their responsibilities. They simply affirm their patients’ self-diagnoses; rarely attempt to talk them out of it or encourage them to wait. Shrier reports that puberty blockers and male hormones can be obtained even after the first visit to a counsellor with “informed consent.” Without any solid evidence (as Shrier shows), counsellors operate on the assumption that:

Adolescents know who they are.

Social transition and affirmation is a no-lose proposition.

If you don’t affirm, your child may kill herself.

Gender identity is immutable. You can’t convert a child out of trans identity.

Dissident Voices

Nevertheless, there are some psychologists, psychiatrists, and medical practitioners who are speaking out against this contagion and pointing out that it is actually a mental disorder. Shrier quotes Dr Michael Bailey, who has arrived at the conclusion that gender dysphoria is a hysteria much like multiple personalities disorder, another historical example of disturbed young women convincing themselves they possess an ailment and then manifesting the symptoms. (Page 133-134)

But in this case, as Shrier explains, there are serious physical consequences for those on the transitioning pathway. Puberty blockers, which are promoted as not having a long-term effect, prevent those taking them from experiencing the effects of puberty experienced by their peers—potentially exacerbating the feeling of alienation from their female bodies.

Testosterone, which almost invariably follows blockers, brings short-term euphoria. But the long-term effects on girls’ bodies, hair growth, mood, voice, vaginal atrophy, etc., are irreversible.

Top surgery, the removal of breasts, apart from the obvious consequences, can lead to scarring and other complications.

Phalloplasty—the surgical construction of something that approximates a penis—involves complex grafting and can leave the patient with terrible long-term complications. Only 3% of “trans-men” go to this stage, and after getting the horrific details of the operation, one understands why.

Regret

Shrier interviews a number of “detransitioners” who wish to “undo” the change. Theirs is not a happy story. Aside from the irreversible physical effects, those who detransition have trouble being heard—it’s not politically correct to give detransitioners a voice.

But Shrier does give encouragement to those who wish to come back or detransition that there is life beyond that.

The Way Back

Chapter 11, the most valuable chapter in Shrier’s book, gives some very clear advice to parents on how to take strong action and not to be undermined or bullied by others when your adolescent girl starts down this pathway. Her seven principles for parents are worth looking at:

Don’t get your kid a smartphone. She lists the damage that smartphones do. If we really had our eyes open to it, we would not put this tool in the hands of our children or teenagers.

Don’t relinquish your authority as a parent. Ride out the emotional rollercoaster etc., with your adolescent girl.

Don’t support gender ideology in your child’s education. One of the ironies is that mental illness support groups can help actually spread the contagion, as per anorexia or bulimia. The same can be with the trans-contagion.

Reintroduce privacy into your home. Don’t put all of family life on social media. Be thoughtful about allowing privacy within your home.

Consider big steps to separate your daughter from harm. Shrier gives the example of the family who actually moved their daughter to a horse farm for a year where there was no internet. This was very successful. Other families travelled with their daughter or moved house, or moved to another neighbourhood to escape peer groups that were toxic. So, there may need to be big decisions made to protect your daughter.

Stop pathologizing girlhood. You need to actually speak positively and understand the positive differences between girls and boys.

Don’t be afraid to admit that it’s wonderful to be a girl. This is a great chapter about the wonders of being female. She finishes with an encouragement for parents, and particularly for those who may be in the process of transitioning and alienated from their parents, to reach out to their parents and be in touch.

This book is very carefully researched and written essentially as a support to parents who are struggling with their girls caught up in this contagion. It lists the terrible damage done to those who proceed down this path but also encourages parents to stay strong and take definite action.

As she is not seeking to present a Christian worldview perspective, Schrier doesn’t offer a consistent understanding of gender as rooted in our creation as male and female in the image of God. However, the book does supply useful statistics and useful responses from psychologists, psychiatrists, and doctors who have had the courage to refuse this progressive contagion.

The article originally appeared on The Gospel Coalition Australian Edition , and is used with permission of the author.

Photo: Unsplash

September 15, 2023

Embracing Oneself by Rejecting One’s Body Isn’t Possible

Today’s blog is the fourth article in our series on gender and sexuality. The collection of quotations I’m sharing today is from The Genesis of Gender by Dr. Abigail Favale, which makes some very significant observations. Some of these quotes are quite deep, but well worth thinking about, so I encourage you to stick with this whole blog. As you read each of them, consider the truths stated as well as the implications of those truths. (Thanks to my son-in-law Dan Stump for putting these together.)

Genesis 2 emphasizes another vital principle: the body reveals the person. Our bodies are the visible reality through which we manifest our hidden, inner life. Each person’s existence is entirely unrepeatable, and our unique personhood can only be made known to others through the frame of our embodiment. This sacramentality is displayed in the man’s immediate recognition of the woman. They have not yet spoken; she has not verbally introduced herself. Her body speaks the truth of her identity, and this truth is immediately recognized by the man, who is struck with joy and wonder at the revelation of a person with whom he can—at last!—have true communion. (p. 40)

In the parade of animals, the man’s act of naming does not impose meaning but recognizes meaning that objectively exists. God creates the animal and presents it to the man, who discerns its distinct nature and bestows a name that proclaims that nature…Reality, then, exists prior to our naming it, and our language is true and meaningful when it corresponds to what exists. (p. 42-43)

Now, unmoored from the body altogether, gender is defined by the very cultural stereotypes that feminism sought to undo. In other words, when a girl recognizes that she does not fit the stereotypes of girlhood, she is now invited to question her sex rather than the stereotype. (p. 158)

Shedding the visible markers of femaleness may feel as empowering for the transgender teen as it does for the anorexic, but these forms of protest are ultimately violent and self-destructive. The better rebellion, and the more difficult one, is learning to see one's beauty and dignity as a woman amidst a culture that denies it. (p. 174)

Children who are given puberty blockers and then placed on cross-sex hormones never go through puberty. That natural process is completely halted. Not only does this lead to permanent sterility, it also arrests critical brain and bone development that occurs during puberty. The long-term ramifications of this artificial arrest are not yet known. (p. 186)

Moreover, contrary to activist rhetoric, halting puberty does not just push pause, creating more time for discernment about transition. Nearly 100% of children put on puberty blockers proceed to take cross-sex hormones, with irreversible side effects. (p. 187)

According to Laura Reynolds, a former trans-identified woman, the gender paradigm has “rebranded self-harm as self-care.” (p. 193-194)

The affirmation model, while often motivated by good will, is ultimately unethical…The Goodness, wholeness, and givenness of the body is discarded…This approach inverts the very definition of health, by pursuing a “treatment” that makes a healthy body ill…In this model, the body is the scapegoat, blamed as the sole source of one’s pain and sacrificed on the altar of self-will. (p. 197-198)

The affirmation model cannot offer true self-acceptance, unless the body is no longer considered part of the self. Choosing a lifetime of medicalization in order to maintain an illusion of cross-sex identity is not “being who you really are.” The affirmation model is self-denial masquerading as self-acceptance. Because our bodies are ourselves, what is being “affirmed”, ultimately, is the patient’s self-hatred. (p. 200)

Using sex-based pronouns, rather than gender-based pronouns, is undoubtedly disruptive and likely offensive to most trans-identified people. Such a move could close the door to a relationship with that person from the outset. Yet, if I use pronouns that conflict with sex, I am assenting to an untruth. More than assenting, in fact; through my own words I am actively participating in a lie. (p. 206)

It is not possible to embrace oneself by rejecting one’s body. (p. 231)

The gender paradigm is diabolic, in the literal sense. I realize this is a provocative statement, but I also believe that it is true. It is a framework that deceives people, whispers the enthralling lie that we can be our own gods, our own makers, that the body has no intrinsic meaning or dignity, that we can escape our facticity and find refuge in a tailor-made self. In this framework, sex, a reality that encompasses the whole person, is fragmented into disparate features. Woman is cut off from femaleness, a disembodied category that anyone can appropriate. This paradigm takes the human desire for conversion, rebirth, resurrection and bends that desire toward a cheap counterfeit. Interior agony and emptiness are projected onto a healthy body, which then becomes an easy scapegoat, a concrete “problem” that can be “solved.” The problem is not the body. The problem is the very real and painful experience of disintegration, a problem that can have any variety of sources, depending on each person’s circumstances. This problem of disintegration can’t be solved by a philosophy that is ultimately nihilistic, that denies the possibility of meaning beyond the self, and in this way denies the possibility of wholeness. (p. 235)

(For more on Dr. Favale’s book, see this review: Male and Female He Made Them.)

Dr. Favale mentions the issue of preferred pronouns, which some believers are being pressured to use in their jobs and ministries.

Author and preacher Shane Pruitt offers these points:

Often, I’m asked by Christian leaders about the use of “preferred pronouns.” Here are 4 reasons why I don’t use or ask for “preferred pronouns.”

1) It’s tied to an obvious cultural agenda. This was never a thing, until very recently. We don’t typically use third person pronouns when talking to someone.

2) As a Christian leader, how am I going to be a steward of the truth, while at the exact same time affirming a lie?

3) When will the shift take place? Some people will say we do it for the “spiritually lost.” However, what if they do become a believer? At what point in the discipleship process will you have to tell someone that you actually never believed in their “preferred pronoun” to begin with? Isn’t it better to lovingly stick to the truth from the beginning, so it doesn’t seem like a “bait and switch” down the road?

4) Others in the ministry are watching. If I compromise there, then I have to also ask, “Am I discipling people to believe the whole movement is okay?”

Be kind. Be loving. Don’t look to argue. We can be welcoming without being affirming. Look to win people with Spirit and Truth, because we can’t win them with confusion and compromise.

And in this video, Alisa Childers and Dr. Jeff Myers discuss how Christians can appeal to conscience when asked to participate in using preferred pronouns.

Also see the article “Why I no longer use Transgender Pronouns—and Why You shouldn’t, either” from Rosaria Butterfield, a sister in Christ, who is a former, in her words, “queer activist.”

It can be very hard to communicate on issues like these with both grace and truth. We are concerned for another person’s soul, not wanting to be harsh, and trying to be gracious and kind, but it is also critical not to undercut the truth. (For more thoughts related to communicating with grace and truth, see my book The Grace and Truth Paradox.)

May God give His people wisdom and grace to communicate in a way that honors Him and truly loves others.

Photo: Pexels

September 13, 2023

Navigating a Strange New World: Insights from Carl Trueman on Gender Confusion and the Modern Self

Today’s blog is the third guest article in our series on gender and sexuality, featuring insights from author and professor Carl Trueman. Earlier this year I read both of his books (I listened to them both on audio; Carl was the reader, and he did a great job). The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self is very academic and gets beneath the surface of modern gender confusion and its consequences. Strange New World is certainly not shallow, but it’s more readable and much shorter, and of the two books, it’s the one I will most recommend to others.

Here are some quotes:

“Every age has had its darkness and its dangers. The task of the Christian is not to whine about the moment in which he or she lives but to understand its problems and respond appropriately to them.”

“The intuitive moral structure of our modern social imaginary prioritizes victimhood, sees selfhood in psychological terms, regards traditional sexual codes as oppressive and life denying, and places a premium on the individual’s right to define his or her own existence. All these things play into legitimizing and strengthening those groups that can define themselves in such terms. They capture, one might say, the spirit of the age.”

“While earlier generations might have seen damage to body or property as the most serious categories of crime, a highly psychologized era will accord increasing importance to words as means of oppression. And this represents a serious challenge to one of the foundations of liberal democracy: freedom of speech. Once harm and oppression are regarded as being primarily psychological categories, freedom of speech then becomes part of the problem, not the solution, because words become potential weapons.”

I want to share two resources from Carl that I think help round out our discussion of gender and sexuality. First, he recorded a video for Awana children’s ministry on “The Self, Identity and Children.” It’s very well done.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Va5eRoy9s_I

Second, Carl was a guest on the Crossway podcast to talk about Making Sense of Transgenderism and the Sexual Revolution. The whole podcast is excellent. Here are a few highlights, though I definitely recommend you read/listen to the whole thing:

I think what we're seeing today is really the latest iteration, or the culturally logical outworking, of trends and ideas that have been in place for hundreds of years. It's important, I think on two fronts, that we recognize that. One, so that we are less shocked and disoriented by what's happening. Two, so that we actually know the precise significance of what's happening. So many Christians, for example, when confronted with LGBTQ+ issues, tend to think that we're debating behavior—what sexual behavior is appropriate or isn't appropriate. In actual fact, as far as the LGBTQ+ movement is concerned, we’re debating identity. Knowing how these movements have emerged, knowing the kind of cultural pathologies (as I call them) that lie behind them will enable us not to be surprised—we should be horrified, but not surprised—by these things; and too, enable us to understand how a) to train our own people to think about these things, and b) how to respond to those individuals we meet who are perhaps caught up and positively disposed towards these movements.

…Human beings have always had that intuitive sense of what we might call “individuality.” What I mean by the self is how we understand ourselves as individuals to relate to the world, to relate to life as a whole. What is it that makes us happy? What is it that we see life as being about? What is the purpose of our existence? Does it have a transcendent aspect? Is it purely to do with this world? What is my purpose here? What are my obligations and duties here? How do I think of my self within the world at large? That's what I'm trying to get at. When it comes to the sexual revolution, I think a lot of us tend to think of the sexual revolution as an expanding of sexual behavior. It wasn't legitimate to have a baby outside of marriage, to live with somebody before marriage, to sleep around. It wasn't considered legitimate to do that pre-1900. Even though it all went on, there was an amount of social shame involved in that. But now we just broadened the boundaries and all of that kind of behavior is okay. And most significantly, of course, homosexuality in Britain—I don't know about America—was illegal until the late 60s. You could go to prison for being a practicing homosexual. We got rid of those laws, we've expanded that.

The tendency in Christian circles is to think the sexual revolution is all about just expanding the boundaries. I don’t think it is. I think the sexual revolution actually rests upon a deeper transformation of what it means to be a self, of how we think of ourselves in relation to others and the word, what makes us tick, what gives me my identity.

… What we need is to train Christians to think holistically. Don't teach a course on how to interact with transgender people. Teach people to really understand Genesis 1–3 so they have the basic, theological skills that when they're confronted in the workplace or in the public sphere with serious questions and challenges of how to I vote on this and how do I think about this, they have the multi-tool already in their head that they're able to bring to bear upon the specific problem. So I would say in engaging in the political sphere, we need to stand for the faith; but we need to understand what the faith is first. That, I think, involves a lot more than just teaching people to memorize Bible verses. One of the things I encounter while teaching undergraduates at Grove City College is it's not enough for me to say, Well, the Bible says it's wrong. They will respond, Well yes, but the Bible says a lot of things that we don't follow now, Dr. Trueman. So why do we still hold to this? I think that requires us to explain why the Bible says that is wrong. And that's a much more holistic and complicated task than simply shouting Bible verses.

Photo: Pexels

September 11, 2023

How Transgenderism, Homosexuality, Abortion, and Hook-up Culture All Devalue the Human Body

Note from Randy: Today’s guest article is the second in our series on gender confusion and sexuality. It’s based on a presentation that Professor Nancy Pearcey gave at Cairn University related to her book Love Thy Body. Nancy is brilliant; she used to co-author with Chuck Colson, one of my heroes. The premise of her presentation is insightful: many of the cultural issues of our day, including transgenderism, actually have a very low view of the human body. (I asked EPM staff member, Stephanie Anderson, who edits my blog, to write the rest of the introduction to this article. She did so, and I agree with it 100%.)

Consider one trans youth who says in a video interview, “There’s so much trans hate in the world right now, and I’m so done with it.” The interviewer asks, “Where do you personally feel that hate is coming from?” At first the response is, “Most places…but especially the government.” The interviewer then pushes the youth to answer more specifically: “In your own life, where would you say you feel the hate the most?” The answer: “I feel like… I kind of internalize a lot of the hate, so it feels like it mostly comes from myself at this point.”

Though the video was shared by “Meme’nOnLibs,” and the person who re-posted it says, “This is hilarious,” it’s quite sad. Here is a youth who has bought into lies that promised happiness, fulfillment, and a source of identity, but in truth only deliver bondage, deception, pain, and ultimately, self-loathing of one’s own body and mind.

How much better is the Christian worldview of the body; as Nancy puts it, “Christianity provides a high view of the body in its approach to all of these issues.” As you read Nancy’s article, consider how the Biblical message differs from the false worldviews of our culture.

Love Thy Body: Sexual Truth for a Secular Age

The following is an abridged transcription of Nancy Pearcey’s two-day presentation to Cairn faculty and staff during the annual faculty workshop in August 2021.

After high school, I went to Labri, the ministry of Francis and Edith Schaeffer. This was the first place that I encountered apologetics and the first time I encountered Christians who talked about there being valid arguments, reasons, evidence, and logic supporting Christianity. Schaeffer’s form of apologetics spoke to postmodern young people—including myself—in a way that no other apologetics did, and he heavily influenced my own approach to apologetics.

This influence is evidenced in my book Love Thy Body. I wrote the book because while the secular culture speaks highly of body positivity, they actually have a low view of the body. This is surprising for most people. They think if you don’t believe in God and the physical material world is all that exists, then you would expect that person to have a high view of the body. So surprisingly, it’s just the opposite, and it’s consistent across the many cultural issues of our day: transgenderism, homosexuality, abortion, euthanasia, and even hook-up culture. Even more surprising for most people is that Christianity provides a high view of the body in its approach to all of these issues.

Transgenderism Devalues the Body

Out of all of the topics I’m going to cover, this is perhaps the most obvious example of a low view of the body. Transgender activists explicitly say that your gender identity has nothing to do with your biological sex and that being biologically male or female is not part of your “authentic self.”

A BBC documentary says, “At the heart of the debate is the idea that your mind can be at war with your body.” And of course, in that war, who wins? The mind wins. Philosophers sometimes picture this war using the metaphor of two stories in a building. It was Schaeffer who introduced this metaphor to the evangelical world. In the lowest story is what we know by science, and in the upper story, we put anything that cannot be known empirically. Applying this to the transgender debate, biological identity

is in the lower story and personal sense of self or gender identity is in the upper story. It’s perfectly possible, then, for your gender identity to actually contradict your biological identity. This leads to fragmentation and self-alienation.

This fragmentation is evident even from the language they use. The Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation defines “transgender” as “a term used to describe people whose gender identity differs from the sex the doctor marked down on their birth certificate”—as if it were an arbitrary choice instead of an observed scientific fact. But the Christian ethic rests on a positive view of the body, because we know we have a good God who made the world with intentionality and purpose.

Homosexuality Devalues the Body

Even my homosexual friends agree that on the level of biology, anatomy, physiology, and chromosomes, males and females are counterparts to one another. That’s how the human sexual and reproductive system is designed. To embrace a same-sex identity, then, is to contradict that design. It’s to say, “Why should the structure of my body inform my identity?” ”Why should my biological sex as a male or female have any say in my moral choices?” We need to help people see that this is a profoundly disrespectful view of the body. It pits the mind against the body and says it’s only the mind and feelings that count. Christianity gives an ethic that overcomes that inner division, that split in the sense of self in the body. It leads to self-integration instead of fragmentation. It leads to an inner sense of holism and unity.

My book Love Thy Body is full of personal stories. So let me give you one of my favorite stories. Sean Dougherty was a man who grew up identifying as exclusively homosexual. But today, he’s married to a woman, has three children, and is a Christian ethics professor. He explains, “I stopped defining my identity by my sexual feelings, and I started to regard my physical body as who I was. My goal was not to change my feelings, which rarely works. Instead, my goal was to acknowledge what I already had, a male body, as a good gift from God. And eventually my feelings started to follow suit.” In other words, he acknowledged his embodied existence as fundamentally good. And that’s really the question at the heart of this debate: Do we live in a cosmos operating by blind, purposeless, mindless forces, or do we live in a cosmos created by a loving Creator, which is therefore fundamentally good?

Christians are making a positive case that biblical morality respects our biological identity. The biological correspondence between male and female is not some evolutionary accident. It’s part of the original creation that God pronounced very good.

Abortion Devalues the Body

We usually talk about sexuality issues separately from the life issues of abortion and euthanasia. But there is an underlying worldview—namely a devaluing of the body—that connects them.

A few years ago, an article appeared by a British broadcaster who said she had always been proudly pro-choice until she became pregnant with her first baby. She said, “I was calling the life inside me a baby because I wanted it. But if I hadn’t wanted it, I would think of it as just a group of cells that was okay to kill.” To her credit, she realized that that didn’t make sense. So she began to research the subject. She concluded, “In terms of science, I have to agree that life begins at conception. But perhaps the fact of life is not what’s important. It’s whether that life has grown enough to start becoming a person.”

Do you see how the concept of a human being has been split in two? Professional bioethicists agree that life begins at conception. The evidence from genetics and DNA is too strong to deny it. So how do they get around the science to support abortion? They argue that you can be “human” at one point, but not a “person” until sometime later. They argue that merely being human is not enough to qualify for legal protection. The fetus has to earn the right to life by becoming a person, usually defined in terms of mental abilities, some level of self-awareness, cognitive functioning, and so on. Once the concept of personhood is separated from biology, there is no objective criteria. It becomes completely arbitrary. Every bioethicist draws the line at a different place, depending on their own private views, values, and personal preferences.

You can see how this view can easily extend to euthanasia and assisted suicide. Secular bioethicists say that if you lose a certain level of cognitive functioning, then you are “only a body.” You’re only in the lower story (to use this two-story diagram), and at that point, you can be unplugged, your treatment withheld, your food and water discontinued, and your organs harvested. Being human is no longer enough for human rights.

That view implies a divided concept, a fragmented concept of what it means to be human. It also asserts that the body itself has no particular dignity or value. On the other hand, the pro-life position is holistic, not fragmented. It says the body itself has meaning and dignity and is part of who you are. You can’t separate them.

Hook-Up Culture Devalues the Body

Once again, the way to understand the secular understanding of sex rests on a divided concept of the human being. It rests on the assumption that sex can be purely physical, cut off from the whole person without any hint of love or commitment. Young people know the script all too well, even if they don’t really like it.

In my book, I give several very poignant quotes from college students like Alicia, who says, “Hook-ups are very scripted. You learn to turn everything off except your body. You make yourself emotionally invulnerable.” She’s almost verbally describing the dualism with the line separating who you are physically from who you are as a full human self.

Critics of the hook-up culture, which includes a lot of Christians, often will say it gives sex too much importance, but in reality, it gives sex too little importance. In Rolling Stone magazine, a young man said in an interview, “Sex is just a piece of body touching another piece of body. It is existentially meaningless.”

The hook-up culture expresses the mentality of a worldview that says your body can be treated as purely physical, driven by physical impulses and instincts. No wonder it’s leaving a trail of wounded people in its wake. People are trying to live out a secularist ethic that does not fit who they really are. Even science shows the interconnection of body and person with the discovery of hormones like oxytocin and vasopressin. These are hormones that are released by sexual activity, and they produce a feeling of connection, a sense of attachment. They are sometimes called bonding hormones. A UCLA psychiatrist says, “You might say we are designed to bond.”

How should Christians respond? In all of these cases we should ask, “Why should we accept such an extreme devaluation of the body?” Christians have a wonderful opportunity to show that a biblical ethic is based on loving your body. The Bible’s high view of God’s created order is one reason that it truly is good news. Francis Schaeffer used to say the message of Christianity doesn’t start with salvation; it starts with “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth,” and, therefore, this creation has great value and dignity. We are called to honor our body, to respect our biological sex, to live in harmony with the Creator’s design, and to recognize that the body has intrinsic purpose and meaning.

The article originally appeared on the Cairn University website , and is used with their permission and the permission of the author.

Final note from Randy: If you’d like to hear more from Nancy, see her interview with author Alisa Childers.

One last point: unfortunately, without understanding a biblical theology of the body, sometimes Christians also subconsciously have a negative view of the human body. “Christoplatonism” is a term I coined to refer to how Plato’s notion of a good spirit realm and an evil material world hijacked the church’s understanding of Heaven. From a Christoplatonic perspective, our souls occupy our bodies like a hermit crab inhabits a seashell. Because of Christoplatonism’s pervasive influence, we resist the biblical picture of bodily resurrection of the dead and life on the New Earth, and we forget that Jesus died to redeem both our souls and our bodies. Here’s the appendix from Heaven on this topic, as well as my article Our Most Destructive Assumption About Heaven.

Photo: Pexels

September 8, 2023

Humanity Is Made in God’s Image, Male and Female

Note from Randy: When we were both speaking at an apologetics conference some years ago, I had the privilege of meeting Christopher Yuan, who is an author, speaker, and instructor at Moody Bible Institute. We quickly became good friends. I read a lot of books, and his Holy Sexuality and the Gospel: Sex, Desire, and Relationships Shaped by God’s Grand Story is on the shortlist of most important books I’ve read in the last decade.

Christopher covers sex and gender in his newly released The Holy Sexuality Project video series for parents/grandparents and their teens/preteens. There is a great need at this cultural moment for parents to disciple their children and teach them God’s truth. That’s why I’m incredibly grateful for his wise, Christ-honoring voice.

This first guest article in our series on gender, written by Christopher, provides an important foundation for understanding gender from a biblical perspective.

He Made Them Male and Female: Sex, Gender, and the Image of God

By Christopher Yuan

Is “gender” a social construct? Should male or female be a matter of personal choice? Are there more than two “genders”?

Ten years ago, these questions were unheard of apart from English and Women’s Studies departments at secular universities. But as peculiar and even sacrilegious as it may sound, many people today would say yes to all three. Maybe your kindergartener has a playmate being raised “gender neutral.” Or your coffee shop is starting to use name tags with “preferred pronouns.” Or a bit closer to home, you might have a family member who is “transitioning.”

Although the modern West has lost its boundaries and celebrates a plethora of so-called gender options, how should Christians understand and critique today’s concepts of gender in light of Scripture? We begin with understanding, and not conflating, four categories: sex, gender, norms, and callings.

Sex: Male and Female

The term sex has a couple of definitions. It can refer to the act of sexual intercourse or the categories of male and female. For this discussion, we’re focusing on the second definition.

Sex as male or female is an objective, binary classification. In this sense, sex refers to divisions based on reproductive functions. Many today, however, claim that sex is not objective but arbitrary. For example, some assert that sex is “assigned” at birth. This is simply untrue. The sex of a newborn is observed physically by the baby’s sex organs and confirmed genetically through a DNA test.

But what about people who are “intersex”? Does this exceptionally rare condition (by all counts, one in thousands, not hundreds) prove sex is nonbinary and on a spectrum? No. Intersexuality is a biological phenomenon where an individual may have genital ambiguity or genetic variance. In human biology, however, anomalies do not nullify categories.

Gender: Self-Perceptions

The modern notion of “gender,” on the other hand, is a quite recent invention and is more difficult to examine. Unlike sex, gender is a category that exists objectively only in the realm of linguistics. It doesn’t point to anything tangible. Instead, “gender” now is being used to refer to a psychological reality independent from biological sex. It’s the subjective self-perception of being male or female.

At present, this psychological concept of “gender” is essentially being enforced linguistically, with demands to use preferred pronouns and newly chosen names to match self-perception rather than objective truth. But this is how minds are changed — by first changing language.

Given that sex is objective and gender is subjective, you would think we would value conforming one’s subjective ideas to objective truth. Instead, the opposite is true: our culture now values altering the objective, physical reality of our bodies to accommodate the subjective impression of ourselves.

Most people’s self-perception is congruent with their biological sex. For a small percentage of others, it’s not. The mental distress from this dissonance is called gender dysphoria — a psychological consequence of the fall. Some choose to identify as transgender male-to-female or female-to-male, in essence elevating psychology over biology.

However, this new form of dualism separates mind from body and elevates self-understanding as the determiner of personhood — hence the neologism gender identity. The truth of the matter is that sense of self at best describes how we feel, not who we are.

Norms: Cultural Expectations

But some assert that male and female are actually determined by culture. This categorical fallacy is a conflation of male and female with the separate classification of masculinity and femininity. Masculinity and femininity are behavioral characteristics associated with being male or female. Admittedly, these social norms can sometimes be shaped by our culture and expectations.

For example, in some parts of the United States, being masculine frequently means being rough, tough, unemotional, and inartistic. For some, the quintessential all-American man might be a rugged, loud, and bombastic football player or construction worker. Yet in many other places, these two examples would not be considered masculine, but barbaric!

Who says a man can’t be artistic? Jubal was “the father of all those who play the lyre and pipe” (Genesis 4:21). Moses led Israel in a song of victory over Egypt (Exodus 15:1–18). David was skilled at the harp, and wrote numerous psalms (2 Samuel 23:1). He also assigned men to be musicians in the temple (1 Chronicles 25:1–31).

Who says men cannot be emotional? Many of the prophets, such as Ezra, Nehemiah, and Jeremiah, were not afraid to express their emotions through public tears (Ezra 10:1; Nehemiah 1:4; Lamentations 1:16). Even Jesus himself wept publicly (John 11:35). Strong emotions are not reserved for women only.

King David was known for having a heart after God. He’s famous for his brave exploits — first as a shepherd boy when he fought lions and bears to protect his sheep, then as a youth who defied the giant Goliath, and later as a warrior-king. But David was known for also being sensitive and intuitive, exhibiting traits that macho culture would view as inappropriate for a “real man’s man.” Had David grown up today as a young boy playing the harp, some kids may have teased him for being a sissy.

Callings: Manhood and Womanhood

Does this mean there are no distinctions between male and female? Instead of looking for cues primarily from society, we must look to Scripture. Cultural norms for male and female may be shaped by society, but God’s word communicates that men and women, while being equal in value, are also distinct in their callings. We identify this distinction of calling as biblical manhood and womanhood, a category the secular world doesn’t acknowledge.

In the creation account, God creates the woman to be the man’s “helper fit for him” (Genesis 2:18). The word helper (Hebrew ‘ezer) does not denote a person of lesser worth or value. In fact, ‘ezer occurs 21 times in the Old Testament, and 16 of these refer to God as Israel’s help.

“Fit for him” (kenegdo) communicates complementarity — both similarity and dissimilarity. Adam and Eve are both alike as human beings and also not alike as male and female. God intends for the woman to complement and not duplicate the man. This difference of calling is God’s design from the beginning.

The apostle Paul exhorts husbands to love their wives “as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Ephesians 5:25) and wives to submit to their husbands “as the church submits to Christ” (Ephesians 5:24). These distinct callings are vital in marriage, the church, and other realms as well.

More Than Biology

In the first chapter of the Bible, God creates the heavens and the earth, and fills the earth with living creatures. The crown of creation is adam, or man (humankind). And among all the various human characteristics, God highlights one in particular: male and female.

Genesis 1:27 conveys an undeniable connection between “the image of God” and the ontological categories of male and female. This verse consists of three lines of poetry, with the second and third lines structured in parallel, communicating a correlation between God’s image and “male and female.”

So God created man in his own image,

in the image of God he created him;

male and female he created them.

Being created in the image of God and being male or female are essential to being human. Sex (male and female) is not simply biological or genetic, just as being human is not simply biological or genetic. Sex is first and foremost a spiritual and ontological reality created by God. Being male or female cannot be changed by human hands; sex is a category of God’s handiwork — his original and everlasting design.

As hard as anyone may try to alter this fact in his or her own body, the most that can be done is to artificially remove or augment body parts, or use pharmaceuticals to unnaturally suppress the biological and hormonal reality of one’s essence as male or female. In other words, psychology usurps biology; what I feel becomes who I am. When denying this physical and genetic reality, we allow experience to supersede essence, and more importantly, the image of God.

Sola Experientia

As Christians living today in baffling times, we must recognize that the world confuses and conflates these four categories. The world will suggest that masculinity is a social construct (which it may be in part but not the whole) and then assert that male and female is also a social construct — which it emphatically is not.

The ultimate question is: Where should Christians place their emphasis when engaging in discussions on this topic? Transgenderism is not exclusively a battle for what is male and female, but rather a battle for what is true and real. Christians cannot simply nod and smile politely in the face of damaging lies.

Postmodernism, coming out of romanticism and existentialism, tells us that “you are what you feel.” Thus, experience reigns supreme, and everything else must bow before it. Sola experientia (“experience alone”) has won out over sola Scriptura (“Scripture alone”).

But God is saying, You are who I created you to be. The truth is not something we feel; it is not based on our self-perception. In fact, Scripture tells us that the fallen heart “is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick; who can understand it?” (Jeremiah 17:9). We can’t trust our own thoughts and feelings, so we need to submit them to God because we can “trust in the Lord forever, for the Lord God is an everlasting rock” (Isaiah 26:4).

I refuse to place my psychology over my biology, and as a Christian, I refuse to put either above Scripture. I am who God — who makes no mistakes — made me to be. So who am I? Who did God make me to be?

I am created in the image of God, and I am a redeemed Christian man. Nothing more. Nothing less.

This article originally appeared on Desiring God , and is used with permission of the author.

Photo: Pexels

September 6, 2023

Our Cultural Confusion over Gender and Sexuality

The Church’s Opportunity to Speak the Truth with Love and Clarity

The Church’s Opportunity to Speak the Truth with Love and Clarity

Over the last six months, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking and reading about gender confusion, which is sometimes called gender dysphoria. This is an issue of immense importance that we cannot wish away. It has become inescapable, and we and our children and grandchildren will be forced to come to terms with it.

In the decades long history of our website and in the 16 years we’ve had a blog, we have never done what we’ll be doing these next three weeks. We are going to feature a series of guest blogs all related to gender and sexuality. We will look at gender as God’s creation, gender confusion as part of the Fall, and listen to wise voices that can guide us as to what we need to believe and do to walk as God wants. We will seek to please Him and avoid the landmines of a lost and deceived culture. While I am providing intros for each guest blog, they are written by others. This first one, an introduction to the series, is by me.

In the early 1980’s, while still in my late twenties, I began researching my first book, Christians in the Wake of the Sexual Revolution, which was released in 1985. I was alarmed at the degree of sexual immorality I knew of already as a young pastor. (A revision of the book was later re-released under the title Restoring Sexual Sanity.) That book took a toll on me, especially the parts related to children. I vividly remember weeping as I prayed for my daughters while they slept, because of the direction of our culture and all the evils of pornography and sexual abuse they and other children would have to face in their lifetimes.

What I didn’t know, however, is that I would live to see my children’s children growing up in a culture which attempts to teach them that someone is a boy or girl depending on what they want, and decide to choose, regardless of the prior choice of God and biology.

Here’s what I wrote in the introduction of that first book. Forty years later it has come to fruition in ways even more radical than I anticipated:

The sexual revolution has fostered a barnyard morality that robs human dignity. It has resulted in people being seen and treated as sexual objects rather than sexual subjects. It has left us a nation of technological giants and moral dwarves. Millions now live under the burden of sexual expectations and pressures to perform in a prescribed manner. Victims of the tyranny of the orgasm, they feel that unless their sexual experience is what they see in the media—where everyone is effortlessly erotic and every encounter is comparable to nuclear fission—they’re being robbed, or they’re not a real man or a real woman.

Instead of a spontaneous expression of other-oriented marital love, sex has become a self-oriented, goal-oriented obsession—an object of endless analysis, comparison, experimentation, and disappointment. Like the end of the rainbow, the ultimate sexual experience is always sought, but never found. No matter how hard we try, no matter how much we pay to surgically alter our bodies, we are left pathetic creatures, different in degree but not in kind from burnt out prostitutes standing on street corners.

Our modern sexual openness is endlessly pawned off as healthy, emancipating, and long overdue. But is our preoccupation with sex really a sign of sexual health? Who talks most about how they’re feeling? Sick people. Who buys the books on car repairs? Those with car problems. Who buys the drain cleaner? Those with clogged drains. Who thinks about, talks about, and buys the most books about sex? Those with sexual problems.

…The more we say about sex, the more we herald the new liberating sexual doctrines, the more we seem to uncover (or is it produce?) a myriad of sexual problems. The harder we try to drown these sexual problems in a flood of new relationships, erotic magazines, novels, movies, and sex education literature and classes, the louder and more persistently our sexual problems cry out for attention…

The more we have sought fulfillment apart from God, the further into the sexual desert we have wandered. Throats parched, lips cracked and bleeding, we are nomads in search of a sexual oasis that forever eludes us.

Galatians 6:7 says it perfectly: “Do not be deceived. God cannot be mocked. A man reaps what he sows.”

We have turned our backs on the Architect, Engineer, and Builder of human sexuality. We have denied His authority and ridiculed His servants. Our glands as our gods, we have discarded His directions, burned His blueprint, trampled on the ashes, and, like rebellious children, stalked off to do sex our own way. And we are reaping the results.

As pervasive as the sexual revolution was and is, I wasn’t really prepared for the fact that it would not be content to only keep pressing the borders of sexual perversion. In fact, it has led to fundamental and anti-scientific denials of gender reality. It didn’t occur to me that this sex-crazed culture would increasingly come to embrace the belief that people have the right and power to choose their gender. Or that some parents and teachers would encourage children to take hormones and have surgeries to mutilate their bodies in an attempt to artificially change their own biology. Even fifteen years ago, who would have predicted that so many educated people would actually be saying, “You are the gender you choose to be, no matter if your body says otherwise”?

The world is looking for answers to spiritual and moral questions. God’s people don’t have answers for every little thing, but we do have the answers for many big things revealed to us in His Word. They are not easy answers, but they are real ones. For the sake of our children and our culture, may God empower His Church not to doubt, hold back, apologize for, or dilute the answers He has given us. I hope you find this series helpful.

So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. (Genesis 1:27)

“Haven’t you read,” [Jesus] replied, “that at the beginning the Creator ‘made them male and female,’ and said, ‘For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh’?” (Matthew 19:4-5)

Photo: Unsplash

September 4, 2023

Studying God’s Word Will Change Your Life

It’s a great mystery that the Bible is an increasingly neglected book. Some who check social media, texts, and emails multiple times a day think nothing of going day after day without reading God’s Word. That’s why we are spiritually starved and lack the discernment to know what’s true and what’s false.

There is no virtue in having a Bible sit unread on a shelf or a Bible app sit unused on your phone. A Bible does us no good as long as it remains closed. Charles Spurgeon said, “If you wish to know God, you must know his Word.”

Luke makes a profound observation: “Now the Berean Jews were of more noble character than those in Thessalonica, for they received the message with great eagerness and examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true” (Acts 17:11).

They searched the Scriptures—probing, not just skimming. And they searched them daily. (People died to get the Bible into our hands; the least we can do is read it!) And their searching God’s Word daily was a sign of noble character. Unless we establish a strong biblical grid, a scriptural filter with which to screen and interpret the world, we’ll end up thinking like the world. We desperately need not only Bible teaching, but group Bible study that explores the text and applies it to daily life.

My wife Nanci was a huge believer in not just Bible reading, but Bible study. She always surrounded herself with Bible study tools, both in her own time with God, and when writing and editing Bible study lessons for our church women’s ministry. It’s amazing how much time she and the women on the team have invested over the years in preparing these lessons, including many hours of direct study of God’s Word. It was very enriching for Nanci, and fun to see her at the dining room table day after day with open Bible and reference books.

After reading The Joy of Fearing God by Jerry Bridges, Nanci wrote in her journal:

I must study and know God.

I must respond to my awesome God.

I know He loves me.

I know I love Him, and I want to express it.

I want to trust this awesome God who has revealed Himself to me.

I thank Him for His provision, His protection, His guidance, and His compassion.

I will choose to trust Him!

Studying God’s promises is a treasure hunt resulting in great happiness. Some of the precious gems lie right on the surface; others require digging deeper. When we go to God’s Word, the joy of discovery awaits.

Nanci often quoted Psalm 119 in her journal. It has 176 verses, all of which allude to God’s Word and most of which celebrate its truth. Meditating on God’s Word brings us light, wisdom, and joy. “I delight in your decrees; I will not neglect your word” (Psalm 119:16).

Spending time with Jesus, by consistently and regularly reading His Word and praying, is an action we control. The choice may sometimes be difficult, but it is not impossible. It is a conscious action that allows us to renew our minds with the truth and to live well. But instead of fixating on the hard work of spiritual disciplines, focus on the great payoff of delight and finding “great spoil” in God’s Word (Psalm 119:162).

Scripture confronts sin in our lives, prompts us to obedience, and gives us delight in Christ. We need to go to God’s Word, open it, read it, meditate on it, and learn to delight in it. It will make us better, deeper, and happier people.

In this interview with author and speaker Jen Wilkin, she talks about the state of Bible literacy and how we can improve it, and shares how studying the Bible changed her own life. I hope it’s a help and encouragement to you.

Photo: Unsplash

September 1, 2023

As We Pray for and Support the People of Maui, We Anticipate the Coming Eternal Paradise

It’s been over three weeks since there were multiple fires on the island of Maui, including a devastating fire that destroyed historic and once beautiful Lahaina town. Please continue to pray for the thousands of people who have been affected. Because of dear friends freely opening their home to us for decades, Nanci and I often vacationed on Maui, getting to know and love people who live there, and sometimes speaking in churches.

It breaks my heart to see the burnt ruins of some of Nanci’s and my favorite places in Lahaina. But that doesn’t even begin to compare with the trauma experienced by the people who actually live there, and the extent of their heartbreak. Many have lost loved ones and friends, and others lost homes and businesses. Imagine the number of people who are out of work.

The official human death toll was 115 as of Wednesday this week, but an unknown number of people are still missing. CBS News reports that roughly 1,000 people are estimated missing by the FBI. It is hard to escape the conclusion that a number of these may have died. Even without counting the unknowns, this was already the deadliest wildfire in the U.S. in more than a century.

Pray especially for the faithful Jesus-loving churches on Maui. The two I’m most familiar with are Hope Chapel in Kihei and Harvest Kumulani in Kapalua. Pray that they will continue to be a light to the people, a refuge and place of safety as they reach out to needy people in the midst of such loss.

Harvest has set up a Maui relief fund and Hope Chapel, Kihei has also set up a fund to help victims of the fires. EPM has sent funds to help Maui churches serve the needy. If you wish to give and for us to choose on your behalf where we think donations are most needed, we are glad to do so. To give online, select “Relief Fund” on our donation page. Or, if you wish to send a check, mail it to EPM, 39065 Pioneer Blvd., Suite 100, Sandy, OR 97055, and put “Maui fires” on the memo line. As always, 100% of what’s given to our special funds goes to the designated need, and online donations to our relief fund will go to Maui through September 30, 2023.

Ben Prangnell, lead pastor at Hope Chapel, wrote this week:

Here on our campus, we have received and ministered to over 500 families through our Donation Center and Kokua Fund to help them in this time of great need. The physical supplies and financial help are accompanied with a listening ear and prayer. There have been many tears shed and prayers offered with the hundreds who have been helped and ministered to.

…God has positioned us to meet great physical and spiritual needs and respond very quickly to those in need. Hope Chapel is here and committed to be the hands and feet of Jesus until he returns. The reality is that in the not-too-distant future, the media’s attention and the support from the government and national agencies will diminish. What then is left to stand with those who need it most? It will be the churches of Maui and those who partner with us to care for our island community.

And here’s a video and update from Greg Laurie with Harvest, showing side by side footage of Lahaina before and after:

We shot these 2 videos, placed side by side to show the utter devastation of the fire here in the city of Lahaina.

I knew every square inch of this little town, and I had my favorite haunts. It so sad to see it gone. Worse than that, is the loss of human life, with many still… pic.twitter.com/cneLT3toaP

— Greg Laurie (@greglaurie) August 29, 2023

Last week I received an email from Warren & Annabelle’s in Lahaina, a place Nanci and I loved. We went there four times over the years to see their illusionist and card tricks show which was always hilarious. I will never forget Nanci, as well as our friends the Keels and Norquists who went there with us once, laughing uncontrollably.

The owner wrote, “One third of our employees lost their homes, their cars and their possessions. All of them now have no job or source of income and their lives have been shattered. It is heartbreaking.”

When I sent that email with a photo after the devastation to my son-in-law Dan Stump, he said, “It’s a gut punch.” Gut punch is the right phrase. For me, it’s been a reminder of what we know as believers, and yet so easily forget: that this world as it is now, under the Curse, is not our home. Not even close. “The present form of this world is passing away” (1 Corinthians 7:31).

A far better world will be our eternal home, and I think we will always have precious memories of times in this world. But I realize now I had presumed that until Jesus takes me home to be with Him and Nanci, and all of God’s people, I would always be able to go to Lahaina and walk the streets and go into those shops. I thought I’d still be able to eat a cheeseburger in Paradise and Kimo’s, and look over at Warren & Annabelle’s and be flooded with precious memories of being in that town with Nanci and our daughters and their families, and dear friends we’ve vacationed with. The memories are still there, but the same physical places that stirred the memories are not and never will be again.