Caitlin Hicks's Blog: Book Reviews, page 12

October 6, 2020

A Door Between Us

A Door Between Us, a new novel by Ehsaneh Sadr

Blackstone Publishing

Reviewer: Caitlin Hicks

“Why struggle to open a door between us when the whole wall is an illusion?” The sentiment of a favorite poem by Rumi comforts Azar, separated from her husband as she is incarcerated by a cruel and murderous member of the militia in this gripping novel. It is a question of meditation for this character as well as for the reader of A Door Between Us, by Ehsaneh Sadr, and for anyone separated by hard-held political and/or religious beliefs.

The kernel event that sets the contiguous incidents tumbling into the fate of this novel’s characters is a wedding, and a ride in the couples’ car toward their new home after the reception. The second event of significance is the June 12th presidential election in Iran in 2009.

Families of the bride and groom, like Romeo and Juliet, are each on different sides of the political spectrum as family members plot behind their backs hoping to undo this arranged marriage. As the furor over results of the recent election rage around them, on the way home from their wedding, the couple find themselves in bumper to bumper traffic in the middle of a Green Wave protest being dispersed by Baseej, a voluntary militia tasked with arresting protestors. Sarah, the bride, a young, politically naïve woman consumed with trivialities of modern life, her dress, her opulent wedding in one of Tehran’s most expensive hotels, invites a woman protestor to hide in the back of their car.

Although Ali and Sarah are not actively involved in the politics of the moment, they very quickly learn how serious this act is. It is the beginning of their months-long separation as the groom is taken in for questioning. It becomes weeks before Ali is returned, and by this time, their relationship is in jeopardy through these divisive political forces—and their respective families.

The modern, ordinary, daily lives of these families lull the reader into complacency, while the drumbeat of random political and societal forces surrounds them with its menace.

The cruelty of the militia and their severe agenda are not surprising, but the juxtaposition of modern urban Iranian life and the draconian methods of the Baseej add to the tension that characters begin to feel as the trap of fascism closes around their perfectly modern lives, incident by incident.

Family secrets, unexpected liaisons and relationships figure into this cultural tale. Added is the power men have over women in Iran, with the shackles of customs whose controlling origin is a patriarchal religion: obligations of dress and restrictions that forbid a woman to be alone in any kind of situation in public. Even the acceptance of polygamy for men causes many dramas for women, dramas they have no choice but to participate in.

What is most interesting is the thought processes and beliefs that characters use to justify their sometimes murderous activities.

The author has experienced these beliefs, implanted on the brains of every believer and repeated through prayers and meditation throughout their lives, and the reader is taken through the insidious mental gymnastics of characters who need to constantly justify their abhorrent actions. It’s easy to see how religion is used as an excuse, and to her credit, Sadr skillfully creates characters who behave with love and respect, and yet are driven by beliefs that can be twisted to hurt, injure, and destroy.

At first, the story is somewhat confusing if you aren’t accustomed to Iranian names such as Sadegh and Sumayeh, Mehri and Mahdiyeh, Azar, Alireza and Abba, and there is a full page at the beginning of the novel spelling out the relationships and names of 19 characters who interact to make up the central story of the novel.

Much of the forward movement in the novel takes place as characters explain their actions to other characters, as they try to unravel secrets and their own family history, but the final confrontation of the religious and political forces is riveting in its unpredictability, violence and redemption.

The Door Between Us is ultimately, a celebration of our connectedness, in spite of our best efforts to sort each other into Us and Them.

This review first appeared at New York Journal of Books, here: https://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book...

The post A Door Between Us appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

September 27, 2020

Eulogy for my father

How does a child summarize the life of her father? Especially one child, among so many? Number Six in a family of 14 steps up to write and deliver the Eulogy for the family patriarch of an enormous, Catholic family in 2005.

Harry J. Hicks, Jr. was a child of the depression. He served in the United States Navy and was at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked. And then, he met our mother. Three months later, they were engaged to be married. So many details, so little time.

Carousel, One Man’s Family, Bonjour/Arrivederchi and Love, at Last are part of this story. Listen to these first. And then sit down in the pew and be part of the congregation.

The post Eulogy for my father appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

September 14, 2020

Love, at last

“What a relief, my father is still alive! Of course I forgive him everything.”

“The universe opens up when someone verges between life and death, doesn’t it?

People get really wise and turn on to what’s right in front of them.

“This moment, for instance. This beautiful day! The air we’re both breathing.

Maybe, maybe, maybe I thought, we could have a relationship.“

The post Love, at last appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

September 1, 2020

The Fear of Everything, by John McNally

“Although McNally’s stories seem unbelievable at first, they throb with a recognizable human heartbeat, powered by love and regret and the mystery of l ife.”

In this collection of short stories, John McNally invites us on a few short journeys and after the first collection of sentences, the reader is under his spell. His stories are so bizarre and compelling, so reassuringly normal, yet slightly off kilter – you just can’t begin one without finishing it.

How does he bring you into his magical, dark, mysterious, yet delightful world? Katy Muldoon was the bait in the first story. “We were a pitiful lot of boys that year, the year we were supposed to learn the metric system.” The year was 1976, the year they fell in love with Katy Muldoon.

In the next paragraph, McNally paints a detailed, yet familiar picture of the world we’ve been through, wherein we can relate to the attraction of a girl whose hair cut reminds of Dorothy Hammill, the Olympic figure skater. “We rode three-speed bikes and tortured bugs. We learned how to shoot milk through our noses, to peel back our eyelids and make scary faces, and to create obscene noises with our hands and armpits.” And then, on Friday of Career Week, a magician visits their school and from the lot of them staring up at him onstage from their seats in the auditorium, the magician sees only Katy, selecting her to be his assistant. After the bunny and the dove appear, he invites Katy to step into a closet. And when the smoke clears, when he points his wand, Katy disappears. And the reader can’t put that story down until he/she finds out what happened to this beloved young woman.

Then there’s the guy who reinvents himself after his wife dies. He gets tattoos, dyes his moustache dark and grows it out, (somehow resembling the magician from the prior story), wears a Kentucky Fried Chicken T-shirt and ends up, ironically, falling asleep in a closet, holding a woman named Zoe who is afraid of everything.

As a writer, McNally understands the power of detail, but also the necessity of being succinct. His characters, rooted in a recognizable human nature, always follow what at first seem like random trajectories, as the narrative goes where it unexpectedly goes.

His brilliant descriptions of feelings that visit his characters, according to their circumstances, surprise and delight: “he felt a pang of remorse along with something else he couldn’t put his finger on, but it was a feeling he suspected people felt when they stepped out of their storm cellar and saw their entire neighborhood had been sucked up by a tornado, twirled several dozen times, and let go.”

McNally uses the telephone over and over—almost as another character in many of his stories. In The Phone Call, Dougie follows the trail of a mystery on the anniversary of his mother’s murder; he manages to have poignant conversations with himself at various ages, crossing time and space through the magical realism of a black rotary phone with extra-terrestrial properties. And although McNally’s stories seem unbelievable at first, they throb with a recognizable human heartbeat, powered by love and regret and the mystery of life. The longing of a child for his mother is especially poignant in this tale; it’s understated and removed by time and space. And yet the story is fueled by the character’s—and the reader’s—imagination required to fill in the visual details of a phone call, as drama unfolds on the other end.

In another story, a dead man is found in the stairwell of a parking garage—and his cell phone is full of images of a man’s penis. A latchkey kid dials up a pretend grandpa in an old folk’s home and hears the story of his life in “clues” dished out in every call—the entire story held together by the telephone.

A ten-year old girl navigates a life as an outcast between her sheriff-father (whose chief task is to oversee hangings of criminals in their town), her mother (who betrays her extramarital affairs with body language), and her accusers (who bully and taunt her as the devil). A lonely man separates from his wife and invites another woman home for a drink. A hand gets mangled in a garbage disposal; a husband and wife put their pug down as the last shared activity of their marriage.

What happens in all these stories is as appalling as it is fascinating, rewarding, and sad. With The Fear of Everything, McNally has finally triumphed over his scary dreams.

The Fear of Everything by John McNally

University of Louisana at Lafayette Press

Launch date: September 1, 2020

Reviewer: Caitlin Hicks

This review is published on New York JOURNAL OF BOOKS.

The post The Fear of Everything, by John McNally appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

August 28, 2020

Bonjour, Arrivederci

I think of them everyday. All sixteen of them.

My enormous family. My ailing father.

In the midst of a trip to France and Italy and an opportunity of a lifetime — with daily news via email from my siblings — “he’s going to die” “he’s better!” “he’s had a setback” —I struggle to decide: Should I cut my trip short to be present for my father’s final moments?

Or follow our destiny to fulfill the invitation to exhibit at the 2006 Olympic Winter Games in Italy— and hope he lives through the night?

On trains, buses, planes and taxis, memory and meaning bring present and past together. When everyone you loved was alive.

The post Bonjour, Arrivederci appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

August 24, 2020

Stories of Us

New Podcast Some Kinda Woman, Stories of Us

features dramatic & comedic work

of international playwright/ performer

Caitlin Hicks

Stories provide rich connection with a simple, intimate

(radio-like)technology

during COVID-19

A new series of episodes and stories called Some Kinda Woman: Stories of Us, in the form of a podcast, has debuted on iTunes, LibSyn, Stitcher, IHeart Radio and other podcast hosts, for international audiences. The podcast features B.C. playwright/performer Caitlin Hicks, and the many quirky characters from her standing ovation tours of one-person theatrical performances in England, Ireland, the United States, Canada and Sweden.

The series features a variety of characters from Hicks’ original theatrical work: Mother Love, Next of Kin, Stories for a Winter Solstice, The Life We Lived, Singing the Bones, Six Palm Trees and Just a Little Fever. Each story is a character-based short tale of a moment in a life and celebrates unique challenges and triumphs that women experience, from their own point of view.

Many stories are based on true stories, others are fictional. The series The Life We Lived, for example, features stories inspired by real-told accounts of the lives of women living on the Sunshine Coast from the thirties to the seventies. Hicks identifies each story and credits each teller. Stories already uploaded from this series include: Read Island Santa (included in the Introduction to the series), Rachel is Born, Gladys and the Pig Man, Women of Essondale, Those Darn Chickens, The Hospital for Injured Snakes, Louella Who Survived Her Times, Your Predecessor Had a Nervous Breakdown!, Everything is In Motion and A Knock on the Door. Other stories such as Stormy Night on Seymour Narrows was inspired by life in an earlier time on the coast – but is fiction.

Through this podcast, Some Kinda Woman: Stories of Us, as Hicks embodies different characters, she celebrates women and gives them a voice.

The podcast is new, but the work has toured internationally in towns and cities to robust audiences, excellent reviews and standing ovations. The work is sharp, humorous and emotional, the characters outspoken, the issues and events in women’s lives from lighthearted Christmas nostalgia to the exhilaration of a powerful birth, to difficult memories of losing a child to divorce, to unexpected death, spousal violence to abortion. Some stories of old timers tell of physical, emotional and financial hardship as settlers of a harsh land (The Life We Lived). Other stories are spoken through hilarious characters who speak their mind (Six Palm Trees, Gertie!).

FOR BACKSTORY, photos, illustration and discussion of each podcast, go to: https://www.caitlinhicks.com/wordpress/podcast/

Or, go directly to the Podcast page and begin with the Introduction to the series: https://www.caitlinhicks.com/wordpress/podcasts-some-kinda-woman/

Or, subscribe on iTunes: https://podcasts.apple.com/ca/podcast/some-kind-of-woman/id1490499019 where you’ll find the podcast & show notes

The post Stories of Us appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

August 18, 2020

behind the red door

a novel, by Megan Collins

This review is also published on The New York Journal of Books here https://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/behind-red-door-novel.

Reviewer: Caitlin Hicks

“Behind the Red Door by Megan Collins is a chilling psychological drama as disturbing as it is mysterious.”

Is it possible to recognize someone and not remember them at the same time? What contributes to our sense of safety in the world? How reliable are memories, and why do we block them?

Behind the Red Door by Megan Collins is a chilling psychological drama as disturbing as it is mysterious.

Disturbing because we have all been children. Each of us has trusted what we learn in the embrace of our childhood. We have all evolved out of the cocoon of blissful dependency into a person who suddenly “gets it,” who can see the world in new and significant detail. Fern Douglas is that child, involved in a defining incident when she was on the cusp of being a teenager.

A woman named Astrid Sullivan has been kidnapped again 20 years after she was first abducted and released in a small New Hampshire town. When Fern sees the television news of this event, she recognizes a freckle under the woman’s eyebrow, and realizes she has seen this person before: How can this be and why can’t she remember?

Not your usual suspect, Fern carries a backpack of anxiety around every corner; her father is a career scientist who has strayed from the mainstream with his unorthodox methods of studying fear. Fern’s childhood was filled with these fear traps her father set for her as part of his experiments. And Fern, a grown woman in a healthy, loving relationship and trying to get pregnant, in her mid-thirties, is still trying to please him. She never quite heard the “I love you” from her father because he was always so addicted to his work, tap-tap-tapping on his typewriter in his study, or setting up false terror episodes to scare her, then debriefing with her afterwards so he could “study” her fear.

After seeing the freckle and sensing familiarity, Fern dreams in high-def: images that haunt her during the day as she tries to help her father pack to move to Florida. Meanwhile, Astrid Sullivan has written a book about the kidnapping 20 years ago, and it has been released, close on the heels of her second disappearance. When Fern reads Astrid’s account, she reluctantly identifies with a second person who was held against her will in the same basement: Astrid calls her “Lily.”

Fearing that the kidnapper may be looking for her, and she may be in danger herself, Fern presents herself to the police and declares herself as Lily, even as her memories of this trauma are still coming into focus. But, of course, Fern is not the first woman who has claimed to be Lily; the book is a bestseller and the second kidnapping has ramped up interest to a frenzy. Fern is roundly ejected from the police station; now she must solve this eerily familiar mystery herself. One by one, her memories and Astrid’s book begin to piece together a picture of her involvement with Astrid’s abduction 20 years ago. But why did Fern bury these memories? And who kidnapped them both? His figure is remembered in black: long gloves, a mask, waders; almost every inch of him covered and unrecognizable.

As she encounters people and places familiar to her as a preteen; as she pieces together the events of kidnapping and her proximity to these events, Fern becomes as unsettled as she is determined to find the truth. Who? Why? And will he strike again?

We meet Father Murphy with his claustrophobic lectures to Fern about her lost soul; he was there 20 years ago, minutes prior to Astrid’s abduction and is considered a reliable witness for the police. He repeats an acceptance of the events as punishment for Astrid’s wicked soul—as she was “caught” kissing another young woman. Cooper, a bully with a menacing tattoo who terrorized Fern as a young teen, reappears, wanting to purchase a house in the dark woods that could have been the site of their confinement; even Astrid’s parents, in the habit of lying to set up her father’s fear episodes, withholds information from 20 years ago. Everything preys at the edges of Fern’s sanity, filling her with doubt yet fuelling her resolve. The kidnapper is out there; the truth seems tantalizing and near.

And it’s a shattering truth.

Megan Collins has created a suspenseful novel that is ultimately haunting —it lingers, asking questions about our experience as human beings in relationship with others, about our expectations of ourselves and each other, responsibilities we take on, and the legacy of our actions.

The post behind the red door appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

August 8, 2020

One Man’s Family

Backstory for the novel A THEORY OF EXPANDED LOVE.

‘Daddy in our midst so tiny, his small frame lost in billowing clothes and an oversized hat, a hunched-over reminder of our own mortality . . .

The patriarch of an enormous Catholic family turns 88 with children & grandchildren celebrating him. Details of a family still intact just prior to the family’s demise are captured through the lens of one child, returning after years of absence.

“And yet, everything still in its place. . . details long ago forgotten but instantly remembered around every turn . . . Here, as long as the rules were obeyed, the world was kept at bay. ‘Say grace, stack the dishes, don’t forget to say ‘Eternal Rest’. As if we were still children, as if we, too, were safe from life’s inevitability . . .’ A moment in the delicious, sad remembrance of an achingly familiar scene just months before irrevocable change.

Previously published in HERIZONS, in 1999 under the title: One Man’s Family.

The post One Man’s Family appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

August 7, 2020

Carousel, by April Ford

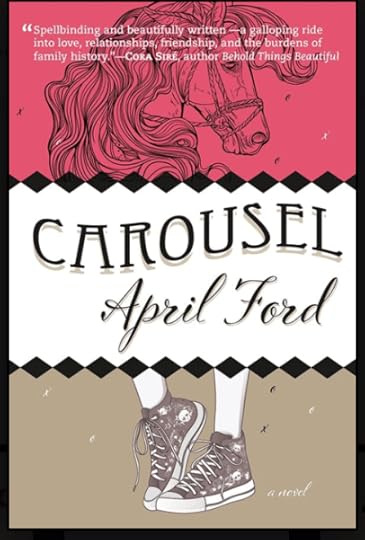

Winner, 2020 International Book Award for LGBTQ Fiction, Carousel is the debut novel of April Ford and the story of a middle-aged woman caught between the buried emotional impact of her devastating childhood and life on the precipice of retirement with her beautiful true love, Estelle.

The story opens on a description of the world’s first galloping carousel, Le Galopant, (otherwise known as an antique merry-go-round)—magnificent horses frozen in place, yet still turning in circles for riders in an amusement park on a humid July evening in Montreal. Here we meet Margo, via her interior monologue, as she provides a short history of antique carousels, as she tries to photograph something interesting for her wife, and questions when was the last time she and Estelle had done something romantic together? Here Margot admits “After two-and-a-half decades with a woman whose gasp-worthy winsomeness and intelligence I had vowed to protect and nurture for the rest of our lives, I was bored.”

The carousel itself anchors the story that revolves around it—a glimpse into a vulnerable relationship in the wake of a 25-year history and the sudden discovery of essential emotional information from Margot’s past. This history, long ago stashed away, ignored and buried, becomes achingly meaningful as Margot is forced to look at it and acknowledge how it shaped who she is.

As the story opens, Margot photographs Le Galopant in a confused effort to do something nice for Estelle (whose career focus is the art of photography and who has been oddly obsessed with the ancient carousel). Here she meets a lanky young woman at 17 who captures her gaze and ultimately becomes the temptation dangling before her in her dissatisfied state of restlessness. Her name is Katy, and during this evening in July, Katy snaps a photo of Margot atop a galloping horse on the carousel, a photograph that Estelle would claim “in the twilight of our marriage, the most telling photograph of a person she had ever seen.” The rest of the story is the circuitous path toward understanding what that photograph might be and how it could be so telling.

At the outset, Estelle mirrors her partner’s unease, and has been meeting with a couple’s counsellor named Weinstock for the past five months, a counsellor who gives them a homework assignment—some kind of physical distancing over a vague timeline. As Margot goes through an evening at a fancy hotel by herself, the reader endures this temporary separation through her simmering discomfort and ambivalence of being forcefully separated from Estelle.

Constantly referring to Estelle as “my wife,” Margot perhaps unintentionally insinuates possession rather than simple relational identity. After its use over and over when Margo could simply say, “Estelle” instead of “my wife,” these words of ownership and societal definition betray an underlying defiance and insecurity inherent in Margot’s personality and her relationship with Estelle. Although it seems that Margot is the straying member of this partnership, and she controls the narrative, the reader is forced to guess at Estelle’s intentions.

“My mother had already gone mad by the time she gave birth to me,” begins Margot, remembering the secret of her life that she has kept from Estelle. As we learn about the remarkable events when Margot’s beautiful mother met her rich and impetuous father, as we learn about Margot’s neglected childhood, as she meanders through her own story, like the child she was when she first experienced it, the devastating emotional reality of her experiences build, one on top of the other. As Estelle discovers the truth of Margot’s origins, in unopened letters from Margot’s mother, Margot is forced to admit that her relationship with Estelle was based upon a lie. Of course, Margot would be having a crisis of the soul. One can only keep the lid on this kind of history for so long.

Throughout this journey, even as she is in the same room with Margot, Estelle comes in and out of focus, but in the snippets where we experience her, she is surprisingly faithful, loving and upbeat about their union; she works hard to unlock Margot’s secrets—secrets, that Estelle has discovered, stand firmly as obstacles to deeper intimacy.

The discovery of the truth that Margot had tried to escape through denial are teased out over the length of the novel, until finally, at Estelle’s insistence, both are in the same room with Margot’s institutionalized mother, Marguerite. It is here we feel the weight of witnessing a frail life almost at its end, having been wasted in a cloud of mental illness and alcoholism. From Margot’s POV, (the child returning to the devastation of her meaningless childhood), we experience the contempt of Marguerite’s altered personality, and understand that a parent can always injure her child.

Written by a deft storyteller, the novel features delightful snippets of description around every corner: “When I turned back, Estelle looked at me like a little girl stricken from having failed her spelling bee.” In describing her mother’s emerging “catastrophic flaw” Margot creates a moving picture of her own desperate discovery: “Now that it had emerged, like a swimmer finally succeeding in breaking the surface after being held under water by a bully, it was swiping and clawing at everything in its way . . .” And although the story must go down the wounding path of Margot’s childhood, the novel is light, its characters optimistic and lovable and the experience of reading it—delightful.

Inanna Publications & Education, Inc.

Publication date: May 8, 2020

Reviewer: Caitlin Hicks

This review was Published at New York Journal of Books, August 2020

The post Carousel, by April Ford appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

July 25, 2020

Carousel

“Mother held my hand as we walked the sidewalk together towards a shoe store under the blazing sun; she tucked my hair behind my ears as we sat at the edge of the dining room table, the summer Aunt Dodie visited.

I can see these offhand gestures in blurred detail, framed around the astonishment I felt that she had registered my existence amongst all those other kids.”

The post Carousel appeared first on Caitlin Hicks.

Book Reviews

From the main page, click on 'Reviews' Book reviews for New York Journal of Books are published here, as well as independent book reviews.

From the main page, click on 'Reviews' ...more

- Caitlin Hicks's profile

- 39 followers