E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 23

April 30, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Bethany Hegedus: Poetics of the Picture Book

The oft misunderstood picture book form is best compared to poetry, whether a text rhymes or not. Alliteration, onomatopoeia, assonance, end rhyme, rhythm, repetition, simile, metaphor, syncopation, meter, motif—the list of poetic terms picture book writers have in their toolboxes is unlimited.

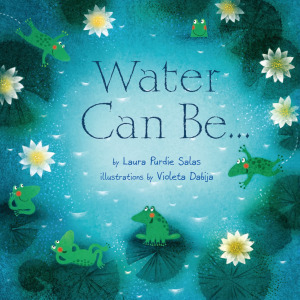

Atheneum Books for Young Readers, March 2014.

We picture book writers work in parameters—for the most part these days—that parameter is word count, not a structural form such as a sestina, yet still we have to convey a story with a beginning, a middle, and a satisfying and re-readable ending. If you think poetry editors of literary magazines are hard to please, try an over tired toddler at bedtime, who is begging for one more read. In 100 to 500 words, the modern day picture book is a thing of magic. In between its hard covers a new world awaits, a mix of visual art, and conscious language that is chosen for effect.

A picture book author reduces the text until it sings. Take for example, one of my favorite picture books ALL THE WORLD by Liz Garton Scanlon and illustrated by Marla Frazee.

Rock, stone, pebble, sand

Body, shoulder, arm, hand

A moat to dig

A shell to keep

All the world is wide and deep.

Little, Brown, September 2013.

Pacing is another important ingredient. Here is an example from one of the best books of last year, MR. TIGER GOES WILD, by Peter Brown.

He wanted to loosen up.

He wanted to have fun.

He wanted to be…wild.

Here, the “rule of three”—a picture book term for using three examples in a row does much to set up the Tiger’s desire to shed his 18th century buttoned up clothes, and be…as a tiger should be…wild.

Even a picture biography, such as Alicia Potter’s new JUBILEE: One Man’s Big, Bold, and Very, Very Loud Celebration of Peace with illustrations by Matt Travers, benefits from wordplay. The book opens:

As a boy in Ireland, Patrick S. Gilmore loved music. He thrilled to hear the army bands march by.

Rum-Tee-Tum! Rum-Tee-Tum! Rum-Tiddy-Tumm-Tumm-Tumm!

My latest book, GRANDFATHER GANDHI, co-written with Arun Gandhi, grandson to the Mahatma and illustrated beautifully by debut talent, Evan Turk, uses lyricism to convey emotional truths. At a prayer meaning, the text reads:

With the dark of early morning wrapped around us, we prayed. Silence filled the air. Everyone was still, but I was fidgety. The peace of prayer felt far away.

So next time you are in the bookstore, in search of a poetry collection, wander down the picture book aisle. Between the vivid and varied art depicting the 32 page form, you will feel like you’ve been transported to an art museum, and the text, whether verse or not, will give you much to admire and may even have you begging for a re-read, when you get to THE END.

Bethany Hegedus.

Bethany Hegedus’ books include TRUTH WITH A CAPITAL T (Delacorte/Random House) and BETWEEN US BAXTERS (WestSide Books). Both novels were named to the Bank Street Books Best Books, with BETWEEN US BAXTERS garnering a star for outstanding recognition.

Her debut picture book, GRANDFATHER GANDHI, (Atheneum/Simon & Schuster) co-authored with Arun Gandhi, grandson of the Mahatma, and illustrated by Evan Turk has received starred reviews from Publisher’s Weekly and Kirkus.

Bethany has served as the Hunger Mountain Young Adult & Children’s Editorsince 2009. A graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in Writing for Children & Young Adults, Bethany is the Owner and Creative Director of The Writing Barn, a writing retreat, workshop and event space in Austin, Texas.

A former educator, Bethany speaks and teaches across the country.

April 29, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Padma Venkatraman: For Better or Verse

When I heard the voice of Veda, the protagonist of A TIME TO DANCE, in my head, I was petrified. Not because it felt like schizophrenia, by the way. I’m used to that feeling. As far as I’m concerned, when I’m writing, I’m just experiencing a mild form of schizophrenia. I always have. I actually enjoy hearing voices in my head.

Nancy Paulsen Books, May 2014.

What scared me was that this time, the story was appearing in a form I’d never used before to write fiction: verse.

I was trained as an oceanographer, so I’ve spent a large part of my life working in laboratories or on ships. And although I’ve read a tremendous amount of poetry in my life, I’ve never really taken a formal course in literature of any sort. How dare I write novels…let alone write a novel in what was, perhaps, poetry?

I tried ignoring Veda’s voice, but she didn’t let go of me. I tried writing her story in normal prose, but that just didn’t ring true.

Then, I went to the library and wasted time trying to figure out whether what I was writing was prose or poetry.

One night, right in the middle of this struggle, I remembered that my first piece of published writing had been poetry.

Padma working in a Lab.

Several decades ago (I won’t say precisely how many), when I was about 8 years old, I (with the supreme confidence of childhood) submitted a few poems to an established literary journal that was published in England on beautiful paper. As a child in India, I’ll admit that glossy paper attracted me as much as what was actually printed on it – most Indian publishers couldn’t afford nice paper. Miraculously, the journal accepted and published my work, alongside the work of established Indian and British poets.

The memory of that early acceptance helped me to silence my fears and listen fully to the voice in my head. At last, the writing flowed. Characters and emotions haunted my world and filled my days, the way they always do when I’m deep into a novel.

This isn’t to say I didn’t edit by the way – of course I did. It’s just a different “me” that does the editing (remember I said I was schizophrenic). On days when I can’t hear a voice, I don’t force it; instead I either get my machete and hack and slash at the words I’ve written, or else I read, read, read.

A TIME TO DANCE was completed last year, and by then I realized how well verse worked with the dance theme in the novel – form and function going together. Last week, the novel was launched in the Caribbean, where I was chief guest at a book festival – a marvelous honor for which I’m deeply grateful. In May, A TIME TO DANCE will be released in America, to starred reviews in Kirkus, Booklist, VOYA and SLJ, as well as an IndieBound citation. And looking back on the process of writing A TIME TO DANCE, I see that I’ve learned an incredible lesson, a lesson that I hope will be useful to other writers as well.

The lesson: Cultivate your schizophrenia.

Padma working aboard a research ship.

Nuture your creative self by doing whatever it takes to still your mind. For me, it’s usually yoga (pranayama) and meditation. On some rare days, though, it takes quite the opposite approach to make my mind quiet: I have to enter a café so noisy I can’t hear my own fears piping up. Find what works best for you in terms of not letting your intellect get in the way when you are in the “writing” mode; and do all you can to foster your self-confidence from within (don’t obsessively seek external recognition). Listen to your loved ones (my young one told me – mommy, your books are the best in the world even though I haven’t read them yet), believe them, revel and luxuriate in the warmth of supportive memories.

When you’re in the writing zone, whether it lasts five minutes (yes, sometimes it’s that short for me, I have a young child), or five hours (a luxury for me at this point), don’t worry about rhythm or meter or any other thing. Just write, write, write.

On days when you aren’t feeling inspired, don’t push yourself to write. Instead, edit your work or to read other people’s work critically. Reading develops and strengthens that other part of your split personality – your editorial self.

I’ve read, read, read. I’ve recited Sanskrit hymns, sung Tamil poems, read poems in French, German and of course, my most beloved language – the language I write in – English. I’ve read long dead poets like Shakespeare, Keats, Elliot, Rilke and Celan as well as living poets such as Charles Bernstein and Martha Rhodes and Maya Angelou and Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni. I’ve read prose poets like Peter Johnson who write for young adults, nonfiction poetry books like Borrowed Names and Carver: A Life in Poems, and even rhyming poems for children starting with Robert Louis Stevenson, and moving to Eileen Spinelli and Mary Ann Hoberman and beyond.

Sometimes unpublished writers tell me they don’t read poetry because they’re scared it will turn them into copycats. All I can say is, if you work at developing your writer’s schizophrenia, reading will only influence your intellectual editorial self. So long as you strengthen your self-confidence, you’re unlikely to imitate. You’ll stay original and creative.

Once you learn to find stillness within, you can open your eyes and ears and heart to the world outside. You can listen to the marvelous earth we live in and to the extraordinary universes of your imagination.

And you’ll be able to write – poetry, prose or something in-between – without wasting time wondering what other people may call it.

Padma Venkatraman.

Padma Venkatraman is the author of CLIMBING THE STAIRS and ISLAND’S END, both of which were released to multiple starred reviews and won several awards including (but not limited to): winner of the Julia Ward Howe Boston Authors Club award, winner of the ASTAL RI Book of the Year award, winner of the international SANOC South Asia Book award, winner of the Paterson Prize and many honors such as ALA BBYA, Booklist Editor’s Choice BBYA, Kirkus BBYA, Booksense Notable, Bank Street College of Education Best Book, New York Public Library Best Book for Teens, Capitol Choice, CCBC choice, Publishers Weekly Flying start etc. Her latest novel,A TIME TO DANCE, will be released to starred reviews in Kirkus, Booklist, VOYA and SLJ this May.

Written in verse, A TIME TO DANCE is a novel about Veda, a dance ingenue who loses her leg and struggles to dance again. Veda learns that to regain her passion, she must also learn to share it with others. She becomes a teacher, discovers romance, and awakens to the spiritual power of her art as her courage is tested to the extreme.

Visit Padma at www.padmasbooks.com, friend her on fb or follow her on twitter (@padmatv). She will be doing signings in New England, Virginia, DC, MD and CA this summer, and teaching a workshop at the University of Rhode Island’s Ocean State Summer Writing Conference in June.

April 28, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Catherine Owen: Writing Through Grief, Grieving Through Writing

ECW Press, April 2014.

Writing DESIGNATED MOURNER over a span of four years prior to and following my spouse’s death from an addiction-induced heart attack has been both the hardest and the most obvious act I have undertaken. Obvious because, well, that’s what writers do, they write. In the face of everything. Even when they don’t want to, when they are exhausted to the core from crying.

Hardest as it feels at times like reduction, false transcendence, impossible closure. Now that I have the book in my hands I sometimes recoil at the notion that it has become this – text – instead of him- living being. And then despite the beauty, terror.

There are many form poems in this book, both strict and adapted, and it was form, old fashioned and tinged with predictability that, perhaps ironically, made writing about such post modern sufferings like crack addiction possible for me. Form also contained my grief at Chris’s death in a way that looser styles couldn’t, enabled a singing in that seemingly relentless, at times, darkness.

Excerpts from DESIGNATED MOURNER:

“The Crackhead’s Palindrome”

It comes right down to this. Just one more hit

and he will be cured of the need

for this frenzy in the dark, this scrounging:

things he can pawn, lies he can tell.

She will know then; all will be revealed.

Something will save him from the sharp,

tight hankering in his brain, this net

he’s cast around the world: the feel

of pressing the glass mouth full, sucking

and the sense that he is everything

in that one split second rush.

Now he is Hercules eternally, is he not?

So surely this time that will be it.

O surely this time that will be it.

Now he is Hercules eternally, is he not?

In that one split second rush there

is the sense that he is everything, sucking,

pressing the glass mouth full, the feeling

he’s been cast around the world, a net

tight & hankering in his brain.

Something will save him from the sharp. She

who will know then; all will be revealed —

those things he’s pawned, the lies he can tell.

All for this frenzy in the dark, this scrounging

to be cured of the need.

It comes right down to this. Just one more hit.

“Sonnet on You Not”

So I am still in the world of things

& you not, no longer needing to select

the latest brand of cereal or car,

to choose whether to sit on chair or couch,

use a glass or mug, the thousand everyday

moments of purchase & desire, now I am

left in the world of things while you

have lifted beyond the weight of coverlets

& seatbelts & the body, that even in loving,

how heavy it can be, yes, you are unclothed

and outside of your cartilage & skin & all

that bric-a-brac of bones; you have flown

into the lightness where dust & the dream

conjoin and I am left behind, another thing

in the world of things.

Catherine Owen.

Catherine Owen is the author of nine collections of poetry, the most recent being TROBAIRITZ, SEEING LESSONS, FRENZY, and the chapbook STEVE KULASH & OTHER AUTOPSIES. Her collection of memoirs and essays is called CATALYSTS: confrontations with the muse. FRENZY won the Alberta Book Prize and other collections have been nominated for the B.C. Book Prize, the ReLit, the CBC Literary Prize, and the George Ryga Award. Owen lives in Vancouver, British Columbia.

April 25, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Madeline Kuderick: Writing in Verse. How Sick is That?

So here’s the thing about writing a novel in verse. It’s sort of like the flu. The way it crawls up inside you and makes every muscle in your body ache. Especially your heart. And you’re kind of delirious the whole time you’re writing it. Your head is in a fog and the words are seeping out of your body like a cold sweat. When it’s over, you find yourself slumped at the keyboard. Feeling like a fever broke. And you can’t quite remember how the words got there. But somehow the pages are dripping –

with poetry

and passion

and pain.

HarperTeen, September 2014.

At least that’s how it felt when I wrote KISS OF BROKEN GLASS, a novel in verse coming 9/09/14 from HarperTeen. It took me a year to write the book, but in truth, I penned it in three short bursts of feverish intensity. The first burst happened when I originally caught the idea. And like any good flu, it nearly brought me to my knees. The second burst happened six months later, at the Highlights Founders Workshop, where I was surrounded by the energy and inspiration of other verse novelists. The final bout came the following spring, after I’d read countless novels in verse, and I was infected with their rhythm and the virus of white space.

Which brings me to the other thing about writing in verse.

It’s contagious.

Don’t get me wrong. Not everyone will catch it. Some people are naturally immune. But if you are susceptible, even the slightest exposure will probably do it. And once you’re infected, it gets in your blood, and starts swallowing up descriptive expose, and long, annoying dialogue, and all that other stuff you won’t find in verse novels. And then all you’re left with is the emotion. But let’s face it. What more do you need?

So here’s what you should do if you catch some strain of viral verse. You’ve got to let it run its course.

In the beginning, you should take it easy. Drink plenty of liquids. I recommend cafe mocha which will help with all the sleep you’re going to lose. But most of all, I suggest listening . . . listen for the voice waiting to come out. Because this is when the voice is the loudest. And finding that voice is so critical for writing a novel in verse, you need to be quiet and listen. Oh, and don’t forget to type what the voice is saying.

The next thing you should do is surround yourself with other verse authors. I was incredibly fortunate to attend that Highlights workshop where our faculty included Sonya Sones, author of TO BE PERFECTLY HONEST, Viginia Euwer Wolff, author of the MAKE LEMONADE series, and Linda Oatman High, author of PLANET PREGNANCY. For six amazing days, these brilliant and generous authors shared their insights, challenged us with poetry prompts, performed fireside readings, and offered constructive critique, all set to the beautiful backdrop of the Poconos in fall. I met many stellar authors who were attending the Highlights workshop too. There was K.A. Holt, whose latest book RHYME SCHEMER is coming out this fall, and Sarah Tregay whose latest book FAN ART is coming out this summer, and Jen McConnel whose book DAUGHTER OF CHAOS just released in March. There were sixteen attendees in all and every writer I met was tremendously talented. There will be more books from this group. I’m sure of it. And somehow being in their presence, tapping into that collective energy, was exactly what I needed during my second bout with the verse.

The final thing you should do is read every novel in verse you can get your hands on, from Newberry Winners like OUT OF THE DUST by Karen Hesse to NY Times Best Sellers like CRANK by Ellen Hopkins. Reading these novels can be almost hypnotic as your subconscious is rocked into the rhythm of these lyrical words and you begin to see every white space as a breath and pretty soon your own writing is flowing with the same meter.

Once you’ve done all these things, the bug will probably have run its course. And if you’re lucky, you’ll have a manuscript to show for it, which makes it seem so worthwhile. Like you’d do it all over again. And that’s a good thing. Because here’s the kicker about catching the verse. Did I forget to mention this?

It’s incurable.

Madeline Kuderick. (Photo by Sonya Sones.)

Madeleine Kuderick grew up in Oak Park, Illinois, a community with rich literary tradition, where she was editor-in-chief of the same high school newspaper that Ernest Hemingway wrote for as a teen. She studied journalism at Indiana University before transferring to the School of Hard Knocks where she earned plenty of bumps and bruises and eventually an MBA. Today, Madeleine likes writing about underdogs and giving a voice to those who are struggling to be heard. Her debut novel KISS OF BROKEN GLASS is coming 9/09/14 from HarperTeen.

April 24, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Cassandra Rose Clarke: Poems Inspire Novels

I was asked to write this post because I am a novelist, but I keep wanting to come to it as a teacher. My day job is that of college instructor, and although the vast majority of the classes I teach are the dreaded (and required) freshman composition courses, I occasionally get to sneak some poetry into my lesson plans. I haven’t written poetry since college—like many authors, I dabbled in verse, then moved on to short stories and then finally novels, where I really found my comfort zone—but I still love to read it. I actually think all fiction writers should read poetry, because poetry, with its focus on rhythm and imagery and the economy of words, can teach us lessons about prose and—yes, I’m going to say it—storytelling that a thousand novels never could.

Chemistry!

With this post, I want to share and discuss some of the poems that have inspired and influenced me as a novelist. Most of them are contemporary poems, poems that I read on a whim—either while flipping through a class textbook, or by stumbling across them on the Internet—and all of them have taught me something about writing.

Chemistry Experiment by Bart Edelman

This poem tells a story through an extended metaphor. Even more brilliant is that, when you reach the end, you realize it has actually told you two stories: the literal one, about a classroom chemistry experiment going wrong despite the students following all the directions, and the underlying story, in which it’s not the chemistry experiment that has failed, but a relationship.

The best writing—whether poetry or prose or the script for a television show—is layered. In longer-form stories like novels and movies, this usually translates to external and internal plot. A crack team of mercenaries has to stop a ruthless killer from assassinating the President—external plot. The head of that team of mercenaries sees this as an opportunity for redemption—internal plot. Ideally, the external plot plays on the internal, and in the best cases you can go back and read the story over and over, finding new insights into the characters.

“Chemistry Experiment” does this, too, but as a poem, it’s condensed down, and the revelation about the internal plot is held off until the final lines:

And even now, years later,

When anyone still asks about you,

I get this sick feeling in my stomach

And wonder what really happened

To all the elementary matter.

The ending changes everything. This is not a poem about a run-of-the-mill almost-brush-with-death like I initially thought; it’s a poem about the connection between two people. I immediately reread it, and on second reading, with the knowledge of those final lines, I’m able to see the internal plot—arguably, the “real” plot—shining through. This sort of intense layering is necessary in a poem, where brevity is of the essence, but I’ve seen this technique applied to longer works (for a recent example, see the episode of Hannibal called “Su-zakana”) and it can create a depth and complexity that the usual external/internal interplay can’t quite get at.

Kudzu by Carley Rees Bogarad

This is another poem that utilizes that layering technique. In this case, we’re given information about kudzu: it grows in the American south, it covers and chokes out everything, in Japan it has an actual use. But again, the poem ends with a line that seemingly has nothing to do with kudzu:

In

a

dream

I watch you roll hot

against someone else’s skin.

Kudzu, the demon plant of the South!

Wait, what? I thought we were talking about kudzu, the demon plant of the south! But of course we never were. It’s a metaphor, the bread and butter of poetry. “Chemistry Experiment” is the same way, although the metaphor in that one does tell a recognizable story, with a beginning and an end. “Kudzu” tells a story too, but it’s not immediately recognized as such, since the discussion of kudzu is just that: a discussion. We’re presented with the image of kudzu, not just in the chosen words but in the layout of the poem—notice the typography above, one word on a line? The entire poem does this throughout, moving words from side to side, so that the words on the words on the page literally suggest the idea of kudzu crawling over the landscape. Once this image is seared in our mind, we’re given the point of comparison: sexual jealousy. There’s a story here, but it’s not told to us beat by beat, but in fragments of images. The narrator’s jealousy threatens to “choke and choke, leaving nothing alive.” With just the imagery of the poem, we’re able to deduce an entire narrative for this character. It’s a beautiful example of what reading ultimately is—an interaction between writer and reader—and it’s something that fiction writers should keep in mind.

One last thing: the poem’s trick of arranging the words to suggest kudzu is something that can be applied very effectively in longer writing as well. The seminal example, of course, is Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, but you don’t necessarily need to go full postmodern to make use of the technique. A friend of mind once used it beautifully in a novel to show a character slipping down into unconsciousness.

La Beauté (Beauty) by Charles Baudelaire

Charles Baudelaire.

Charles Baudelaire, like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, was assigned reading for me in college. I’ve written a couple of posts lately about what a huge influence Garcia Marquez has been on my writing; however, I’ve not spoken as much about Baudelaire, despite his work, this poem especially, really inspiring me back when I was wee little writerling. I said earlier that I chose to discuss poems which taught me something about writing—that’s not entirely the case here, but I think it’s something just as important.

Reading Baudelaire piqued my interest in writing that was at once beautiful and dark. I don’t mean just in terms of the content, but in terms of the writing itself. I don’t read French, so I’m stuck with the translations, and I still vividly remember specific lines from the prose translations I read in college (I couldn’t find them online, unfortunately). In particular I loved the final line: “My eyes, my wide eyes, eternally bright!” It was the perfect blend of imagery and rhythm and it’s stuck with me all these years.

All writing—all storytelling—has the potential to stay with you. There are novels that I hold close to my heart the way I do La Beauté, but with poetry, I find I am rarely struck with the entire poem, but with pieces of it. In many ways poems showcase the power and strength of language in a way novels often don’t. I do the same thing with movies: certain images will stay with me long after the rest of the movie has faded. A professor once told me that writing a screenplay comes closest to writing poetry, and I can believe it. Both are caught up in rhythm and images and connecting disparate elements in a way that the reader can fill in the rest. Poetry gets a bad rap because people feel like they’ve been force-fed it during school, but I would argue that any writer should add a couple of poets to their TBR pile.

Caroline Rose Clarke. Photo by Brittany at Flashbox Shop.

Cassandra Rose Clarke grew up in south Texas and currently lives in a suburb of Houston, where she writes and teaches composition at a local college. She graduated in 2006 from The University of St. Thomas with a B.A. in English, and two years later she completed her master’s degree in creative writing at The University of Texas at Austin. In 2010 she attended the Clarion West Writer’s Workshop in Seattle, where she was a recipient of the Susan C. Petrey Clarion Scholarship Fund.

Cassandra’s first adult novel, THE MAD SCIENTIST’S DAUGHTER was a finalist for the 2013 Philip K. Dick Award, and her YA novel, THE ASSASSIN’S CURSE, was nominated for YALSA’s 2014 Best Fiction for Young Adults. Her short fiction has appeared in Strange Horizons and Daily Science Fiction.

Cassandra is represented by Stacia Decker of the Donald Maass Literary Agency.

April 23, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Laura Purdie Salas: Looking for Poems in All the Wrong Places

Poetry is like dust. It’s everywhere if you just look closely. I think a lot of us make the mistake of thinking we need beauty and silence and long stretches of time in order to be inspired. But I find poetry to be the most fun when you come across it unexpectedly.

Milbrook Press, February 2012.

Last week, for instance, I was at an orchestra concert. I do not like orchestral music. I’m a word person. I often have trouble staying awake when subjected to music with no words. But the concert we attended was Eric Whitacre, who does compose choral music, so there were words (hallelujah!). At least for some of the pieces. I took my handy dandy notebook with me, and I’ll admit that I actually found the concert interesting and enjoyable instead of boring. But I was still happy to take out my mini-notebook and supplement my listening with poetry writing.

First I looked at the stage through squinty eyes. I like to do that and see what things transform into. I noticed that the choir’s white music folders looked like a hundred flying seagulls, so I wrote:

Choir: five deep rows of black ocean

White vees of sheet music perch against chests–

preening and ruffling to the music,

on the verge of surging upward,

soaring into song

Later, during a piece with no words, I studied the huge acoustical blocks along the wall behind the stage.

A rockslide falls

down the wall of Orchestra Hall:

sugar cubes

igloo blocks

dotless, spotless dice

frozen, mid-tumble

Several pieces and poems later, during the performance of The River Cam, which was gorgeous and kind of haunting, I wrote:

Bridge the seasons–autumn to night!

Snuff out the burning trees

Let liquid sun run down the drain of dusk

Crack open the moon so its snowy core can

bury October

I like the crack open the moon line. That was a gift from a student on a school visit. A third- or fourth-grader with a big ketchup stain on his sweatshirt said the moon looked like an egg and I asked, “What’ll happen if we crack it open?” He said maybe it would snow. And—ping—I knew I wanted to use that image somewhere.

Milbrook Press, April 2014.

The kids who don’t already love poetry are often the ones to utter the lines that make my head explode in a good way. The poetry lovers are sometimes trying too hard to be deep and meaningful. They’re looking for poetry instead of just discovering it in its natural habitat.

Don’t get me wrong. I love poetry about beautiful things. And I sometimes intentionally sit down to write about amazing topics. I love water in all its forms, for instance, and my newest picture book is WATER CAN BE… (Millbrook Press, 2014), a rhyming nonfiction book that celebrates the fantastic and scary and necessary things water does in our world. It is basically a love poem to water, and I had so much fun writing it.

Water is water—

it’s puddle, pond, sea.

When springtime comes splashing,

the water flows free.

Water can be a…

Well, you’ll have to read the book to find out what all it can be:>)

A riddle-ku clue!

It’s just that I think a lot of poets (kids and adults) put pressure on themselves to write poetry only about things they find awe-inspiring or deep. I’ve been having a total blast this Poetry Month writing riddle-ku, which are combinations of mask poems, haiku (really senryu), and riddle poems. I’m posting one every single day of April on my blog, and I have poems on all sorts of mundane, everyday objects like dog leashes and feathers and brooms.

Our whole world is a poem, and you don’t need something spectacular to write about. When you fail a math test or you have to wait for your sister’s gymnastics class to end, when you’re fired from your job or you see an animal that completely grosses you out (daddy longlegs in the shower—eek!), when you’re bored or scared or sad or just annoyed that your pb&j sandwich went soggy—those are all great times to write poems. Just look around and you’ll find just the right poems in so many wrong places!

Laura Purdie Salas.

Laura Purdie Salas is the author of more than 120 books for kids and teens, including WATER CAN BE…, A LEAF CAN BE… (Bank Street Best Books, IRA Teachers’ Choice, Minnesota Book Award Finalist, Riverby Award for Nature Books for Young Readers, and more), and BOOKSPEAK! POEMS ABOUT BOOKS (Minnesota Book Award, NCTE Notable, Bank Street Best Book, Eureka! Gold Medal, and more). She loves to introduce kids to poetry and help them find poems they can relate to, no matter what their age, mood, and personality. She has also written numerous nonfiction books, and she mentors writers through Mentors for Rent. See more about Laura and her work at http://www.laurasalas.com.

Twitter: @LauraPSalas

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/LauraPSalas

April 22, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Ishbelle Bee: Milkshake Witches

Poems are a form of oral magic. They’re spells, recipes for witches. The words ingredients; edible. Each one has taste, each one a colour. If you have excellent ingredients and mix with the right quantities you can produce a delicious cake but if your ingredients are putrid and blended without intelligence, humility or (in some occasions) experience, you produce a disgusting splat.

Ogden Nash.

I wrote a lot of splats when I was teenager. I am all too familiar with splats.

Poetry is an incantation, a little witchcraft. A zap of the wand. Poets are enchanters; they play with words, juggle them like lemons. Rearrange them into different shapes, form strange verbal architecture; construct fairy tale towers. Writers put us under their spells; make us fall in love; then break our hearts. Poems are meant to be read aloud, they are meant to be heard. Eaten through the ear.

The poem that I would like to mention, is one I first heard when I was six years old and it is, quite simply, a little bit of magic.

(Extract of) “Adventures Of Isabel” by Ogden Nash

Isabel met an enormous bear,

Isabel, Isabel, didn’t care;

The bear was hungry, the bear was ravenous,

The bear’s big mouth was cruel and cavernous.

The bear said, Isabel, glad to meet you,

How do, Isabel, now I’ll eat you!

Isabel, Isabel, didn’t worry.

Isabel didn’t scream or scurry.

She washed her hands and she straightened her hair up,

Then Isabel quietly ate the bear up.

Ogden Nash’s poem is simple, witty and powerful. Isabel, using courage and a cool head when faced with frightening adversities, can surmount them. She subsequently goes on to liquidate a witch and decapitate an ogre. Personal power is the issue here. Life is difficult; there’s always going to be monsters; always people who try to belittle us, (sometimes by simply ignoring us). Isabel overcomes her obstacles one by one. The trick is to understand, after dealing with one adversary, there’s usually another lurking suspiciously round the corner, waiting to turn us into finger-food.

It would be an easier world if we could just mutter a few magic words at nasty people and they subsequently explode. Living as we do in a (mostly) rational world, we can overcome difficulties and meet them head on without fear, using logical thinking and a witty verbal one-liner (and not a flame thrower).

Ogden Nash was probably the first writer to influence me. My own writings are predominately interested in personal power gained through metamorphoses (often through hybridisation or a symbolic death). This poem is a reminder to me, that it has taken decades for me to find my own personal power and never to surrender it, not under any circumstances. And if any one tries, find a little oral magic from the pantry and a blender and make a milkshake of them.

Ishbelle Bee.

Ishbelle Bee writes horror and loves fairy-tales, the Victorian period (especially top hats!) and cake tents at village fêtes. (She believes serial killers usually opt for the Victoria Sponge).

April 21, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Sean Cummings: Lest We Forget

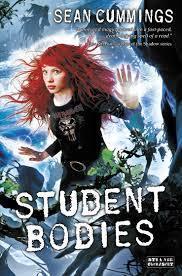

Strange Chemistry, September 2013.

I write bubble gum.

So what is an author with five books about zombies, poltergeists, soul worms and generally fantastical stuff writing a blog posting about poetry for? Because even though I am the world’s worst poet (seriously, my poems would make your eyes bleed) I can’t discount or diminish the importance of poetry to the human experience.

Among the most powerful poems are the ones penned in the trenches during the First World War. My favorite WWI poet is Wilfred Owen. His unforgettable “Dulce et Decorum Est,” for me at least, paints the most vivid picture of the battlefields of France and Belgium:

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!–An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.–

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin,

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs

Bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,–

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

We are many generations removed from a conflict that lay waste to the old imperial houses of Europe and claimed the lives of millions in a wholesale industrial slaughter that even now, one hundred years later, seems almost impossible to envision.

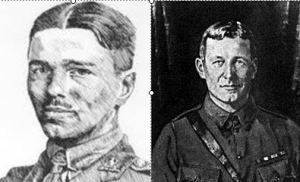

Wilfred Owen & John McRae.

As a Canadian, and a proud veteran of my country’s armed forces, I feel drawn to try and make sense of the First World War because it was on the murderous terrain of No Man’s Land that my country forged its national identity. It has been said the Battle of Vimy Ridge was the place where Canada came of age as a nation because this blasted escarpment that no allied force could capture was successfully taken by Canadian soldiers on Easter Monday 1917. Canada at that time wasn’t even fifty years old. For the first time in the war, all four divisions of Canadian troops fought side by side. They captured the ridge, albeit at a horrendous cost. 3598 Canadian soldiers were killed and another 7000 were wounded. (Canada’s population at that time was little more than 8 million people.)

Canada has always been a big country with a small population. Even now, one hundred years after the start of the conflict, we number only 35 million. Nearly 60,000 Canadians died during those four years of war – a staggering number. Perhaps it is because of my country’s sacrifice during WWI that to this day, Canadian Colonel John McCrae’s poem “In Flander’s Fields” urges us to always remember those who lost their lives.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

On November 11th each year, Canadians gather around cenotaphs in every major city or tiny village across the country. A bugler will sound off The Last Post and someone will read McCrae’s stirring poem that has become an enduring symbol of Canada’s nationhood.

And whenever I hear it being read, I often wonder what it means to Canadians. I wonder if wet truly understand what drove both Owen and McCrae to write the poems in the first place.

Wilfred Owen was an infantry soldier. McCrae was a field surgeon. Owen went “over the top” while McCrae tried to save the lives of the wounded and dying. The contrast here isn’t lost on me and it might be because of their different roles in the war that Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est is an indictment against the generals who ordered men to die by the tens of thousands in full frontal assaults time and time again, and the governments for allowing war to happen in the first place.

McCrae, on the other hand, speaks of passing the torch and taking the quarrel to the foe. It is a patriotic urging to carry on the fight. It acknowledges the sacrifice and speaks for the dead who no longer have a voice. Two different men, two different poets, and two different interpretations of living and dying on the Western Front.

The war claimed both Wilfred Owen and John McCrae. It claimed the lives of more than 16 million people, again, an almost inconceivable number for a generation that hasn’t been touched by total war. There are no Canadians left alive now who fought in the trenches. The last Canadian First World War veteran died in 2010 at age 109 and those few remaining Second World War veterans are now well into their 90’s.

These poems, all war poems, really, are to me at least, a testament to the toll war takes on the human soul. They are personal accounts to look for a deeper meaning to death and carnage.

Each year on Remembrance Day there are wreaths that say “lest we forget”. For those who haven’t been touched by war and cannot comprehend the sheer magnitude of both world wars, the enduring challenge is no longer to remember those who fought died in the mud of the trenches, but rather, to try and understand.

Sean Cummings.

Sean Cummings is a fantasy author with a penchant for writing quirky, humorous and dark novels featuring characters that are larger than life. His debut was the gritty urban fantasy SHADE FRIGHT published in 2010. He followed up later in the year with the sequel FUNERAL PALLOR. His urban fantasy/superhero thriller UNSEEN WORLD was published in 2011.

2012 saw the publication of Sean’s first urban fantasy for young adults. POLTERGEEKS is a rollicking story about teen witch Julie Richards, her dorky boyfriend and a race against time to save her mother’s life. The first sequel, STUDENT BODIES is now available at bookstores everywhere. He lives in Saskatoon, Canada.

April 19, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from K.A. Holt: Poetry is Yours

The thing about writing poetry is that the act in and of itself can ruin your poetry. You are consciously writing poetry. And that is a thing. And you’re aware of what you’re doing. And you better be careful. People will read it and they will know they’re supposed to be reading poetry, and then you’ll be in trouble for sure because… ahhhhh poetry. It’s full of similes and metaphors and imagery and assonance and God forbid rhyme, and there are stanzas and threads of meaning, and everyone knows that if you’re writing about a flower it’s not really about a flower and… ahhhhh poetry!

Chronicle Books, October 2014.

This ↑↑↑ is what I encounter every time I sit down to write a poem. It is the monologue my brain shares with me as it slowly shuts down all circuits. Why would I attempt to write poetry? I am not a poet. I am not Sylvia Plath or Billy Collins. I am not even Ogden Nash. I’m just me. And even though I’m working on my third middle grade novel in verse I find that every morning I’m confronted with these whispers of “what are you doing?” and “this is not great.” and “run for the hills!”

Until…

Until…

I start to write. That’s when everything melts away. Words begin to jump out at me from all directions. They fly from my fingers. I see poetry in newspapers, I see it in books – words hidden in other works, words begging to be strung together, meanings hidden like treasures. I forget that I’m supposed to be a poet, and instead I become an excavator, a mood-finder, a storyteller, a sculptor of language. Like Austin Kleon, I love to take a newspaper article or a page from a magazine and find the hidden poems. Michelangelo used to say that he didn’t create his sculptures, he set them free from the blocks of marble they were mired within. While I’m no Michelangelo, I totally understand what he’s saying. Poems are everywhere. In everything. Here are two I found yesterday:

Are they excellent poems? Are they literature? Nah. But are they cool and fun? Absolutely. Do exercises like this help me relax and sit down and write my verse novels? Totally. Not only do they help me relax and create, they help my work be more relaxed and creative, too.

Roaring Brook Press, August 2010.

Poetry can be anything. It really can be. And I think I have a mission in life to get other people to realize this. Even though we’re often taught that poetry is impenetrable and scary, it really, really doesn’t have to be. When I go do school visits and say that my next book is written entirely in verse, I don’t want to hear the kids go “Uuuugh! Poetry?!” I want them to think “Yay, white space! Yay more meaning with less words! Yay more bang for my literary buck!” But really, in the grand scheme of things, I just want kids to have an initial reaction of “Yay!” instead of “Ugh!” when they hear the word “poetry.”

I know it’s hard. I know – first hand – poetry can be terrifying. But only if you let it. Sometimes, four short, poorly punctuated sentences about a flower, are just that. They’re a little weird poem. Nothing fancy. Nothing even too special. But those four lines, that poor punctuation, it’s yours. It is your moment in time captured. It is your voice for that moment. No one can tell you your voice is wrong. No one can tell you you’re not doing it right. Why? Because it’s yours. And when it’s yours there are no rules. Only words. Only poetry. You can follow parameters set by artists of the past, or you can blaze your own path.

It’s whatever you want it to be.

It’s poetry.

It’s yours.

K.A. Holt.

KA Holt is the author of several middle grade novels in verse including BRAINS FOR LUNCH: a zombie novel in haiku, and the forthcoming RHYME SCHEMER (Chronicle Books, October 2014) and HOUSE ARREST (Chronicle Books, 2015). Kari lives in Austin, TX with her husband and three malevolently charming children. She loves tacos and typewriters. www.kaholt.com

April 18, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Cindy Jenson-Elliott: Potatoetry – Writing Outside with Children

I love potatoes. I love to boil up Yukon Golds, rip through the skin of over-baked Russets, and plop tiny new red potatoes in soup. Even more than eating them, I love to grow them. Finding potatoes in the ground is like uncovering buried treasure—“Wow! Look!” —always a surprise, even if you were the one who planted them in the first place. Finding a potato is like finding just the right word for a poem when you think you have no more good ideas. Wonder. Gratitude. Joy. That’s what I felt when the word “Potatoetry” popped into my head this year—buried treasure from a tired brain.

Potatoes!

As a teacher, environmental educator and writer, I take my students outside to write in nearby nature as often as I can, in as many contexts as I can. The school garden is my current gig, but I have also done science and writing projects in local canyons and creeks. Last year, my favorite project was the Maple Canyon Poets Society with middle schoolers (http://www.sdawpvoices.com/maple-canyon-poets/). This year it is Potatoetry with three second-grade classes.

Beach Lane Books, February 2014.

We plant potatoes each year as part of the second grade’s Ancestor Gardens project. As each child does an in-depth study of his or her own family ancestry in class, we take our learning outside and plant a garden of foods traditionally eaten in the child’s continent of origin. We grow, harvest, cook and eat spring rolls and stir fry from Asia, sukumo wiki greens from Africa, frittatas and turnip soup from Europe, and Mexican and South American dishes with cilantro and onions. We added in potatoes a few years ago, to talk about the role hunger has played in bringing immigrants to our country. We discuss the great potato famine in Ireland, caused in part by the lack of crop diversity. This year I shared the book TEN PLANTS THAT SHOOK THE WORLD to help students understand why potatoes are important historically. It’s a heavy topic.

Knopf Books for Young Readers, June 2003.

Then I received a copy of TWO OLD POTATOES AND ME from Carolyn Fisher, the illustrator of both that book and my book, WEEDS FIND A WAY. Author John Coy’s narrative about a child and father planting potatoes is simple, sweet and moving, and uses potatoes to poetically connect characters across generations. Inside, Carolyn had inscribed the book with a note—“Reach for the STAR-ches!” and told me to look for the face of Abraham Lincoln hidden among the funny-shaped potatoes in one of her illustrations. Ah! Friendship! Joy! Humor! It was sheer potato poetry—potatoetry, in fact! I was so excited, I emailed teachers—“Let’s write poems about potatoes! Potatoetry!”

I began the project by sharing poems about other types of ordinary objects, as well as my own poems about potatoes. We noticed the kinds of figurative language poets used, and how the poet had discovered something special or interesting about each object. Then I had each child pick out a potato from a bag of varied spuds and use their senses to get to know them. Using a template to keep them on track, they wrote their ideas about how their potato looked, smelled, felt. They thought about their favorite potato dishes and how they smelled and tasted. They practiced using metaphors by asking, “What does your potato remind you of?” and extended their imaginations by asking “If your potato could speak, what would it say?” Later, students used these templates to begin writing their potato poems, and created potato art inspired by the work of Carolyn Fisher.

Planting potatoes in the dirt!

As a group project, teacher Shayna Cribbs took a line from each child’s poem and put them in an order that made sense to her as a poet. Then it was time to plant.

We created planters out of old tires donated by a Goodyear franchise near our school. We painted the tires with acrylic paints. Then students wrote their lines from the poem in a looping swirl around the sides of the tires. When the poems were done, we took our tires to the garden.

Of all the many potatoes the children wrote about, there was only room for 3 or 4 inside each tire. (The beauty of planting potatoes inside tires is that, if you choose, you can add tire upon tire to the stack as the potatoes grow up, adding new potatoes to each layer, until you can produce hundreds of potatoes in a three-foot square space.) We lowered thick planting bags into each tire to protect our potatoes from the leachate of any toxins in the tires, and filled them with compost-rich soil. Then the class voted for their favorite Yukon Gold, Russet, purple and red potato to plant. As we planted, Ms. Cribbs read our group poem to the class, each child raising their thumbs, their eyes shining like new found potatoes, as their line was read. Potatoetry indeed!

A potato tire!

“Potatoetry”

By Ms. Cribb’s Second Grade Class, Explorer Elementary Charter School

I plant a potato, as black as night.

Potatoes, potatoes, I found them in the ground,

One golden potato, peeking out,

Goldish, greenish, as big as a baseball,

My red potato rolls, a gift from nature.

One lumpy potato, ready to roast,

looked like a coral reef,

With arms like a ZOMBIE,

Reindeer potato, sprouting antlers,

Sprouting horns, guarding eyes around it.

At once, six eyes all looking at me.

My potato is rough as wood,

With seven eyes.

I had it in my hand so bumpy

bumps, bumps , bumps on top of the head,

Smooth as a new eraser,

the eye of the potato gazing around.

It is smooshy and purple roots,

All craters like the moon. One potato feels

Like an elephant’s skin, brown and red

and a little rough, as rough as sand paper,

as dark as a cave.

Plop! You drop into the pot!

Sizzling like the sun, the potato, hot and gold,

Went into my tummy,

TASTES SO GOOD!

Cindy Jenson-Elliott.

Cindy Jenson-Elliott is the author of fourteen books of nonfiction and hundreds of articles for newspapers, magazines and educational publishers. She is a teacher and environmental educator with an MA in education and a passion for connecting children with nature. In her free time, she enjoys swimming in the ocean and spending time outdoors in San Diego, where she lives and gardens with her family of four humans and three Buff Orpington chickens. Visit her at CindyJensonElliott.com.