E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 24

April 17, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Joseph D’Lacey: When Poetry Makes Prose

During a recent event at which myself and two other novelists were reading, fellow Angry Robot author, Rod Duncan, remarked his development as a writer had progressed like this:

Poet → Short Story Writer → Novelist.

“Aren’t all writers like that?” He asked me when we talked about it afterwards. Whilst I recognised a similar pattern of evolution in myself, I wasn’t at all sure it was a universal characteristic of fiction writers. It made me wonder if, perhaps, many novelists take a similar path but just never talk about it publicly.

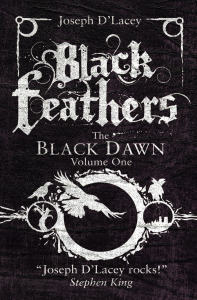

Angry Robot, March 2013.

Rod’s casual statement was the first time I’d heard anyone else ‘admit’ to finding their genesis in verse and yet I identified with it entirely. In my case, poetry had been about testing the literary water, simply to see if I could swim. Dip a toe with a first line of rhyme, paddle up to the ankles with a couple of stanzas, perhaps chance a small wave going ‘above the knee’ with a finished haiku, limerick or villanelle.

For me, the game was all about levels of commitment. And I sucked at commitment in the beginning. Finishing a piece was always the goal, of course, but if you didn’t complete a work of poetry, who cared? Who even knew you were writing it? Back then, writing was a secret pursuit; like learning to swim on a private beach.

But even a sheltered, sandy bay isn’t completely safe. And the danger has nothing to do with who may or may not see you pathetically flopping about in the shallows. Water is magnetic. Come in, it says. Come deeper. Become part of me and I’ll show you my mysteries. Fortunately (in hindsight), I was as ill-disciplined with temptation as I was with commitment. Where’s the harm, I thought, wading brazenly to my waist, hitching in chill-shocked breaths all the while; and it was during these riskier baptisms that I found I was capable of some longer narrative verse.

Sometimes, though, I just sat on the shore and looked out, knowing the ocean was too vast too navigate and impossible to understand. The water terrified me; its depths promising only annihilation. But it never goes away, that mind-bending expanse of possibility, that literary ocean. It waits, eternal.

Without even knowing how I’d got there, I’d find myself wading again. Up to my chest. Swaying in the push-pull of the waves, feet momentarily losing touch, understanding what it means to give in to something far greater than myself.

One day in 2000, I wrote a short story called Getaway Car. It told of a terminally ill woman and the second-hand car she buys for a final road trip, only to discover the previous owner was an angel. The story was accepted on its first submission by a small, indie magazine called Cadenza.

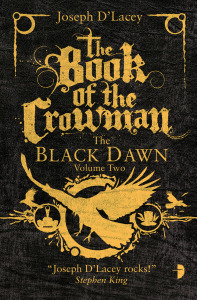

Angry Robot, February 2014.

I glanced back and realised, with some alarm, that what I’d done had taken me quite a way from the beach. No floatation devices. No special breathing equipment. Swimming. Me. Swimming and splashing and laughing at what I could suddenly do. A few easy strokes took me back to the safety of the shore.

But the pull of this tide of words never decreases. All it ever does is intensify.

I knew, then, if I could write a short story, that meant I could write a chapter. And if I could write a chapter, well…With less and less trepidation about my feet not touching the bottom as I swam, I headed farther out into the darker waters and wrote my first novel.

Thirty years seems a protracted period of time to take over learning how to swim but I don’t regret how long it took me to attain the skill – how can you regret a thing that couldn’t have happened any other way? Thirty was the age when I became ready to learn. I’d tried writing stories prior to taking up poetry and I simply couldn’t finish a single thing I started.

For me, working in verse of all kinds has been both fundamental and crucial to my development as a writer. What I’m curious about is how many other people who now write full-length fiction, more or less exclusively, started out as poets. I’ll probably never know, but it would be great to get a show of hands next time I’m in a room full of novelists!

After all these years, I still don’t consider myself a strong or confident swimmer and the fear of what’s down there when I’m in the deeper water never leaves me alone. Sometimes, even now, I’ll spend months on the beach, just being near the water, just knowing that it’s there, but not venturing in.

There’s a tiny part of me, though, that knows I’ll always be drawn back to that immense, unknowable element. That I’ll enter it in order to explore, and all I’ll ever find is more and more evidence of my insignificance against its magnitude.

That same tiny part of me has a mad side too, something that has been altered by the unceasing pull of the tides, a side that yearns to swim out towards the fathomless ocean trenches with no thought of returning.

Joseph D’Lacey.

Joseph D’Lacey writes Horror, SF & Fantasy, often with environmental themes, and is best known for his shocking eco-horror novel Meat. The book has been widely translated and prompted Stephen King to say “Joseph D’Lacey rocks!”.

His other published works to-date include Garbage Man, Snake Eyes, The Kill Crew, The Failing Flesh, Black Feathers, The Book of the Crowman and Splinters – a collection of short stories. He won the British Fantasy Award for Best Newcomer in 2009.

He enjoys being outdoors, eating vegetarian food and was recently adopted by two cats.

April 16, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Gabrielle Prendergast: The Pantoum!

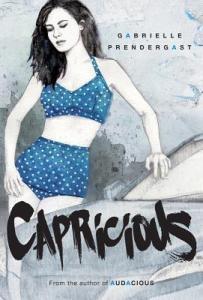

Orca Books, April 2014.

Have you ever read a pantoum? Have you ever written one? A pantoum is one of the oddest poetic forms. Comprised of four-line stanzas in which the second and fourth lines of each stanza serve as the first and third lines of the next stanza. The last line of a pantoum is often the same as the first.I use a pantoum in my latest verse novel CAPRICIOUS, which is the sequel to last year’s AUDACIOUS. It details a scene wherein sixteen year old Ella overhears her parents talking about her in worried tones.

“WORRY”

They talk in lowered voices

I hear them in the tv room

They speak of jobs and college choices

Like one misstep could spell my doom.

I hear them in the tv room

The sound is turned low enough

Like one misstep could spell my doom

I’m not so weak that I can’t face this stuff.

The sound is turned low enough

Do they want me to know they don’t believe

I’m not so weak that I can’t face this stuff?

So quiet now that I can barely breathe.

Do they want me to know they don’t believe

In me, in my maturity? They talk

So quiet now that I can barely breathe

Through my shame, my hurt, my shock.

They discuss me like I’m a notion

They speak of jobs and college choices

They whisper like the distant ocean

They talk in lowered voices.

(From CAPRICIOUS by Gabrielle Prendergast, Orca Books, 2014)

Pantoums are great at evoking the anxiety and obsessiveness of teen narrators, or any narrator who is slightly anxious and/or obsessive. Although you don’t encounter pantoums often, I encourage you to check out a few, even try writing one.

Who is up for the challenge?

Gabrielle Prendergast.

Gabrielle Prendergast is a UK-born Canadian/Australian who lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, with her husband and daughter. She is the author of the verse novel AUDACIOUS, CAPRICIOUS and the forthcoming THE FRAIL DAYS in the Orca Limelights series. Gabrielle blogs and rants at Angelhorn.com and VerseNovels.com.

April 15, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Stasia Ward Kehoe: Oh, Paul Fussell, What You Do To Me…

Although quite unaware, I grew up loving poetry. I remember being six or seven, hopping along the sidewalk outside my family’s apartment building, chanting:

“In an old house in Paris that was covered with vines,

lived twelve little girls in two straight lines…”

(MADELINE, Ludwig Bemelmans)

Stasia onstage in high school.

To this day, inspired by Dr. Seuss’s ONE FISH, TWO FISH, RED FISH, BLUE FISH, I help my littlest one get ready for school by sing-songing my own rendition: One shoe, two shoe, red shoe, blue shoe…

Throughout elementary and high school, my literary tastes turned to realistic and historical fiction, but my love for words with rhythm, rhyme and shape persisted in my performing arts pursuits. I choreographed dances to the poetry of Lawrence Ferlinghetti. I wondered at the gorgeous lyrics (free verse) of Stephen Sondheim and Steven Schwartz. I applauded the stunning dramatic structures employed by playwrights like Thornton Wilder and Caryl Churchill. Every day of ballet class, from plies to pirouettes, I lived my life in meter without even realizing it.

In college, of course, I discovered T.S. Eliot, who revealed how the cadence of a simple nursery rhyme could be turned into an existential poetical grotesque.

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang, but a whimper.

(The Hollow Men, 1925)

Paul Fussell in Paris, 1945.

Emily Dickinson revealed the epic in the seemingly simple, grace and hope set aloft on small, feathered wings. Walt Whitman wrote anthems (it seemed to me) to the value of poetry and art. There were the Irish playwrights, J. M. Synge and Sean O’Casey, whose very titles sang and whose plots were intricately connected to history, to heart (also, I found myself half in love with the flabby little professor who lectured about them).

I drank it all in with more emotion than intellect. Then came a guy whose revelations sat primly behind a plain, green paperback cover: the late, great Paul Fussell (1924-2012). His book, POETIC METER & POETIC FORM glittered with the notion that concepts in poetry could be broken down—that you could have great intentionality in the way you structured your verses.

Stasia’s Fussell notes.

Fussell dropped jewels of insight, like “We can find examples in our most instinctive colloquial phrasings as well, many of which suggest that we all operate in accord with an impulse to make language artistic.” (page 111) This is what I’d been doing FOR YEARS! And, it wasn’t just me. Perhaps poetry is an instinctive act for we sentient humans. Wow!

I was years from truly understanding scholarship (started to get hints of it in grad school) as you can see from just one of the massively over-highlighted pages of my college copy of Fussell.

Stasia’s college copy of Fussell with her maiden name scrawled on the side.

I hadn’t even begun to dream of becoming a writer myself—much less discovering my passion for the verse novel form. But that stodgy WWII vet and University of Pennsylvania professor planted key seeds of understanding that have surely helped my journey to published verse novelist.

That poetry is a craft that can be honed.

That poems can be analyzed and revised to make them do more effectively whatever it is you want them to.

Perhaps most of all, that poetry ISN’T always easy but that it IS important.

Pretty hot for a book with no cover photo, huh?

Stasia Ward Kehoe.

Stasia Ward Kehoe is the author of two verse novels from Viking: AUDITION (2011) and THE SOUND OF LETTING GO (2014) which is a Junior Library Guild Selection. Visit her online at www.stasiawardkehoe.com or @swkehoe.

Stasia would like you to know about the Penguin Teen Twitter Sweepstakes!

DATE: 4/14-4/16

DESCRIPTION:

Followers will be encouraged to write their best 140 character poem using #TwitterinVerse to enter the sweepstakes.

Sweepstakes via Penguin Teen Twitter to win a set of YA titles (Locomotion, Audition, The Sound of Letting Go, and Because I Am Furniture)

April 14, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Michael J. Rosen: A Journey with Haibun

While I’ve been writing haiku (or what works for me as haiku) for 13 years, I’ve only recently worked in the form of haibun (or what works for me as haibun). It’s another traditional Japanese poetic form whose particular stylistic and formal constraints—structure, subject matter, length, point of view, etc.—“translate” from the Japanese language into the English language about as improbably as something from the 17th century does into the 21st.

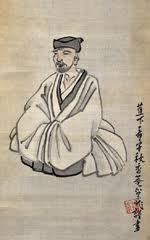

Portrait of Matsuo Bashō by Takebe Socho.

The haibun, attributed to the poet Matsuo Bashō, is a passage of concise, imagistic prose, followed by one or more haiku. Conventionally, it’s an imagistic depiction that is part of a journal or journey.

I can’t read Japanese, but I’ve read countless poems in translation, as well as historical overviews of Japanese forms, and individual writer’s arguments for what, in a given form, is required, isn’t acceptable, and so forth. So even as I value the intricacies and linguistic challenges in haiku and haibun, I feel comfortable participating in the evolution of these forms—this is why I added the phrase “what works for me” above. I approach each form as a structure. As rules for a game. As a set of challenges that restricts and, more crucially, reveals content. I choose form as an inspiration rather than an institution.

Regarding the haibun, I adhere to these underlying principals:

• Neither is the prose merely a set-up for the haiku, nor is the haiku a conclusion or culmination of the prose. Yet the prose and poem should link. A connection that leaps forward or sideways. Perhaps an avatar or shape-change. Perhaps a shift in time or place or logic.

• Consider the haibun more of a regular practice than a perfect execution. Think of it like practicing yoga: It’s about spending focused, challenging time in a very mindful present. Neither is success the execution of one particular poem/yoga posture, nor is failure about writing something faulty/falling out of a posture. Take the work as close to what’s possible in a short period of time.

• Think of haibun as a watercolor in a sketchbook: Find the idea for a composition. Render it quickly. Apply color without fussing. Leave unfinished areas, white space, drips, bleeds, traces of the sketch. Stop before it’s finished. Start another “painting” that might “solve” or continue what this first work has just suggested.

• Have no thoughts about whether one particular work is worthy. It’s the ongoing work—the ever evolving work—that is.

Here are a few examples. They’re excerpts, really, meant to suggest the larger enterprise.

Cardinals

Any night I can, I sleep with the sliding-glass doors in the bedroom open. I drift off to the grumbling of the koi pond’s fountain. I wake to the chortling of the Northern Cardinals: What cheer, cheer, cheer….

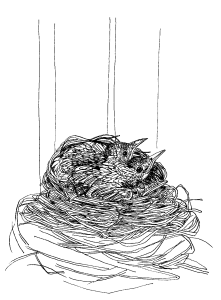

Robin nest, illustration by MJR from his forthcoming book, GEORGICS.

I wish I could recognize each pair that joins the morning rush hour at the feeder. I know they’re residents of this place, just as I am. The male and female both sing throughout the day; paired for life, they usually return to the same nesting area each year. The males will keep up the singing all day, declaring their territory as if each note of their song were twisting into a barbed wire staff to fence out other cardinals.

When the sun sets, the cardinals are the last at the feeder. All that “cheer” must take a lot of energy; it’s only darkness that gives them a chance to be quiet—gives the night birds—chimney swifts, mockingbirds, owls—a chance to be heard.

And every night, as in a creation story, their artful “wire” unravels, so the work of singing must resume the next day, with equal, unabashed ardor.

morning cardinals

calling—does it wake me or

do I wake to it?

All Gray Day

Stunned at the gray’s relentlessness. All of yesterday. Entirely unpredicted. Not a drizzle or drop of rain. But a solid, cloudless gray fixed itself in the sky as if the Earth had stopped moving for a day or the atmosphere had backed up in some meteorological traffic jam, each cloud rubbernecking to see some accident that had long cleared up.

hey! all-day-gray sky

can’t you crack even one smile

of sunshine, just one?

Hummingbird Leaves

The hummers have returned: the same ones who will summer here the rest of their short lives. Over the winter, their favorite ornamental dogwood next to the deck died. No reason I can tell. I appreciate that trees grow old as well as bigger and taller.

Now the birds perch at the tips of bare branches, buzz over to the feeders for a few sips, fly a lap around the lawn or zigzag over to another tree…and then buzz back for another perch. Repeat. Repeat. In the skeletal tree, they’re the only green. Mockingly, they appear to be a few shiny spring leaves.

Yes, I need to take the chainsaw to the dogwood. I need to plant something new, which will take more years than are left to me in order to reach the second-floor deck where the hummingbird feeders ring in summer. (I should investigate the fastest-growing trees.) Even these hummers will have to pass along this destination to their next generation. On average, they only live three or four years. The smaller the creature, the faster it burns through life.

But even we big creatures wish each summer would come at us more slowly.

green leaves on the dead

dogwood: hummingbirds…tinged red—

no, too soon for fall!

Trails

Windstorm. Clearing trails of snapped branches, climbing over or around the downed trees I’ll return to saw later, I unceremoniously inventory the other limbs and trees that fell—but not on the path I’ve made. They will remain where they are: suspended in another tree’s canopy; pining nearby saplings to the ground; collapsed on another rotting tree; shattered at the border of a neighbor’s meadow. It’s only where I want to go…that’s of concern. If there weren’t a path, I’d have nothing to clear. Again. And again.

single-file deer path

now…our steps retrace theirs…now

their steps retrace ours

Living Lawn Art

There was a peacock in the front meadow. It strolled in a straight line as if crossing the street where a patrol was halting traffic. Sure, my brain was about to perceive “wild turkey” (a most familiar, somewhat similarly shaped visitor) when the reality of “peacock” lit up my brain as if the word itself were fanning open like the bird’s feathered train.

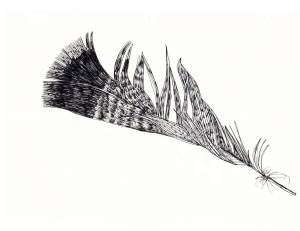

Wild turkey feather illustration by MJR from his forthcoming book, GEORGICS.

Do we have wild peacocks out here…? Hardly: They’re native to India. Did someone have one as…part of a natural alarm system? True: While this particular bird didn’t utter a peep, I’ve heard these peafowls’ amazing shrieks. Some sound like a kitten’s voice ramped up and amplified for a soundtrack in a horror flick. Some sound like an elephant’s trunk blasting one of those feathered, uncurling party whistles. Still others sound like a bullwhip took a long inhale from an empty whipping cream dispenser before some cowboy cracked it on the pavement.

If only this visitor sticks around long enough for me to hear all those vocalizations.

So I checked online to read if there’s any chatting about these birds in my area, rural Central Ohio. On one blog I read: “Only purpose for having peacocks is their beauty. I don’t know of anyone who eats them. They are living lawn art, but other than that, they are very loud and useless birds.”

As soon as beauty becomes “useless,” I will be out of business, and the world won’t be worth the trouble that keeps it spinning.

its tail fanning out

a thousand eyes stare, surprised

at your own surprise

Michael J. Rosen.

Michael J. Rosen is the creator of a wide variety of more than 100 books for both adults and children. A poet, fiction- and non-fiction writer, humorist, illustrator, editor, and, as of 2013 and the premier of “Elijah’s Angel: A Play for Chanukah and Christmas,” a playwright.

Rosen’s many children’s books, such as CHANUKAH LIGHTS, a poetic collaboration with pop-up master Robert Sabuda (Candlewick); BONESY AND ISABEL (Harcourt); and ELIJAH’S ANGEL (Harcourt), have received many distinguished citations, among them, the Sydney Taylor Book Award from the Association of Jewish Libraries, the National Jewish Book Award, the inaugural Simon Wiesenthal Museum of Tolerance Once Upon a World Book Award for the best children’s book that promotes diversity and tolerance, and the Ohioana Library Career Citation in children’s literature. Fifteen of his books such as DOG PEOPLE and HORSE PEOPLE (Artisan), HOME (HarperCollins) and THE GREATEST TABLE (Harcourt), were created with the generosity of hundreds of the country’s best-known illustrators, photographers, authors, and cartoonists as creative philanthropy. Their profits benefitted the Share Our Strength’s work to end childhood hunger and a granting program he created, The Company of Animals Fund, that awarded over $375,000 to 100 animal welfare organizations.

For over 40 years, ever since working as a counselor, youth-services director, day-camp director, and teacher at local community centers, Michael has been engaged with young children, their parents, and teachers. He has taught poetry and other forms of creative expression to adults and youth at literature conferences, colleges, libraries, and many nontraditional learning environments. As a visiting author, in-service speaker, and professional workshop leader, he has traveled to well over 700 schools and conferences around the nation.

Recent books include: a six-book series of nonfiction humor for third/fourth grades entitled NO WAY! that features a volume on world’s most eccentric sports, jobs, foods, buildings, medical practices, and forms of transportation (Millbrook/Lerner Books); a novel in poetry and two voices, RUNNING WITH TRAINS (Wordsong) set in 1969 that interweaves the lives of a divorced boy commuting between cities on the B&O Railroad and a younger farm boy whose land the railroad crosses; and SAILING THE UNKNOWN: Around the World with Captain Cook, a free-verse diary of a stowaway aboard the ship Endeavor (Creative Editions).

Among his forthcoming books are THE HIMALAYAN’S HAIKU AND OTHER POEMS FOR CAT LOVERS (Candlewick); GIRLS VS. GUYS: The Surprising Differences between the Sexes (Twenty-first Century Books); and a picture book, THE FOREVER FLOWERS (Creative Editions).

His poetry for adults has been collected in three volumes: A DRINK AT THE MIRAGE (Princeton University Press), TRAVELING IN NOTIONS: The Stories of Gordon Penn (University of S. Carolina Press), and TELLING THINGS (Harcourt Brace). A fourth collection, GEORGICS, is in production at Cat Steppe Press.

He lives on a 50-acres in the foothills of Appalachia, east of Columbus where he served for nearly 20 years as literary director of The Thurber House, a cultural center in James’s restored boyhood home. During his tenure, Rosen edited four volumes of James Thurber’s work, and began the first of three humor biennials, Mirth of a Nation.

Michael’s Website is www.fidosopher.com.

April 13, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Emily Jiang: Summoning Li Bai

Poetry is one of my greatest passions, and I memorized poems before I learned how to read and write. The first poem I learned by heart from my parents was a poem written over one thousand years ago in China by a one of the country’s most famous poets, Li Bai (701-762).

Here is the poem in Chinese:

夜思

床前明月光

疑是地上霜

舉頭望明月

低頭思故鄉

Li Bai In Stroll, by Liang K’ai (1140–1210).

Here’s my translation (co-translated with C.L. Jiang) of the poem into English:

“Night Thoughts” by Li Bai

Before my bed I see moonlight so white

I think it is frost on the ground.

I raise my head to look at the moon so bright

I bow my head, yearning for my hometown.

If you look closely at the original Chinese poem, the phrase “bright moon” (明月) appears twice, first time in the first line and second time in the third line. After much discussion with my co-translator, I made a conscious decision not to repeat “bright moon” but to change my translation fit the context for a Western reader. I substituted “white” for “bright” because I thought “white” would make more visual sense for “frost on the ground.”

The original Chinese poem of has a very strict structure of five syllables per line with end rhymes. When translating this poem, I chose be looser about the amount of syllables per line, but I also decided to make it rhyme, just like the original poem. However, I changed the rhyme scheme. The original poem in Chinese has a rhyme scheme of A A B B, where the endings of the first two lines share the same rhyme while the endings of the second two lines have a different rhyme. I mixed up the rhyme to be A B A B. True, “ground” and “hometown” is not a precise rhyme, but the vowels and end consonants are similar enough. Contextually, I also liked ending those lines with a concrete sense of place, contrasting with the heavy moon focus of the first and third lines, and reinforcing poem’s theme of homesickness and displacement. In short, the rhymes make the poem more poignant.

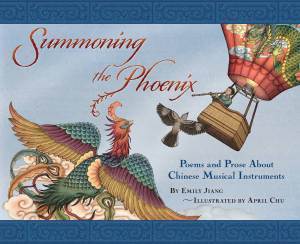

Shen’s Books, March 2014.

As I grew older, the poems of William Shakespeare, Robert Frost, Emily Dickinson, Louise Gluck, Sylvia Plath, and many, many more joined the few ancient Chinese poems I learned as a young child. Although I hold a BA in English and an MFA in Creative Writing (in English), I do think my childhood exposure to Chinese poetry has influenced how I write poetry in English, and my style tends to be more sparse, less florid.

One of the biggest questions-turned-compliments I’ve received from a reader of my new picture book SUMMONING THE PHOENIX was “Who wrote the original Chinese poem?” The poem referenced was “Painting with Sound,” my own original poem. Here it is:

“Painting with Sound”

Picking at my guzheng,

I can feel

the crisp, clean

mountain air

breezing over

my unbound hair.

Strumming my guzheng

I can feel

the cold rush

of waterfall

filling my ears

with thunderous call.

In this poem I wanted to incorporate different senses, as evoked by the title, which mixes the visual (painting) with the auditory (sound). So in the body of the poem, I evoke nature as perceived not through the eyes but through the sense of touch (breezing over / my unbound hair) and through hearing (filling my ears / with thunderous call).

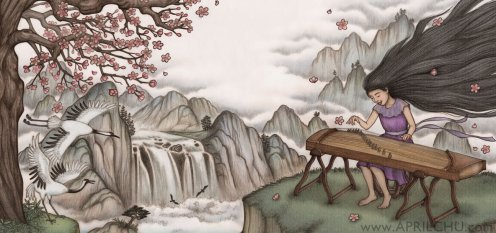

Apparently, I had captured enough of a flavor of Chinese poetry to convince the reader that it was an English translation of a Chinese poem. I was so flattered! Yes, ancient Chinese poets often wrote about music, though the subject matter was more heavily favored to the pipa (aka the Chinese lute) vs. the guzheng. But perhaps the reader was more influenced by the dramatic and gorgeous artwork that is the backdrop of “Painting with Sound.”

With illustrator April Chu’s permission, here’s her stunning artwork that accompanies my poem “Painting with Sound”

Illustration by April Chu.

I absolutely love how her artwork fills in the visual details of the mountain and waterfall that I deliberately left out of the poem. April brilliantly added wonderful details that are not in the poem: the cranes and the cherry tree, with its blossoms floating across the vast expanse to land in the girl’s hair and in front of her bare feet! Also, instead of a traditional Chinese outfit, the girl is wearing contemporary American clothes because she is a contemporary American, with some Chinese influences, just like the me.

Writing the poems for SUMMONING THE PHOENIX was such a wonderful experience, and I hope my readers enjoy my book. If playing music is painting with sound, then writing poetry is painting with words!

Emily Jiang.

Emily Jiang is the author of SUMMONING THE PHOENIX: Poems & Prose about Chinese Musical Instruments, illustrated by April Chu and published by Shen’s Books, an imprint of Lee & Low Books. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Saint Mary’s College of California, where she studied Craft of Poetry with Brenda Hillman and Graham Foust, and a BA in English from Rice University, where she studied poetry with Susan Wood. Her co-translations of ancient Tang Dynasty poetry can be read in Interfictions and Stone Telling. Her original poems have been published in several magazines and anthologies, including Stone Telling, Strange Horizons, Goblin Fruit, and THE MOMENT OF CHANGE anthology of speculative feminist poetry. She blogs at www.emilyjiang.com.

April 12, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Kwame Alexander: Man Power

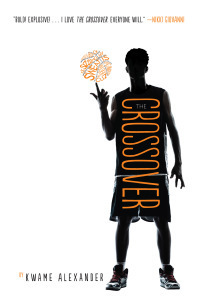

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, March 2014.

After college, I got a job at Hewlett-Packard. Each day when I’d arrive at work, I’d spend the first 15 minutes or so journaling, writing about a lame open mic I attended; or a spectacular evening spent at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art; or the horrors of my nine-to-five imprisonment. From time to time, I’d write little funny poems about life and love. These musings all shared one thing in common: they were random, unadulterated, unedited, and funny (at least to me). Eventually, I got into the habit of faxing (I know, I’m dating myself. We didn’t have email) these free verses to my best friend each morning. It was our morning ritual, never to be missed. She’d become a little testy if I was late or delinquent in my literary responsibility. The name of the folder I’d saved all of these was Manpower. I chose this name because it spoke to my supreme manliness. It also happened to be the name of the Temporary agency I worked for.

Before I knew it, a year had passed by, and I was addicted to these free writes. One Saturday I started reading through each entry and made an awkward discovery: The notes I was sending to my best friend seemed to be getting more and more personal. Intimate even. Was I falling in love with my best friend? In that moment, sifting through these “Manpower” poems, I was inspired to write a poem. A gentle, yet “manly” poem that described what I was feeling in that moment. I walked to her home (I was a poet, folks. I couldn’t afford a car), and read it to her:

I am not a painter

browns and blues

we get along

but we are not close

I am no

Van Gogh

but give me

plain paper

a dull pencil

some scotch

and I will

hijack your curves

take your soul

hostage

paint a portrait

so colorful and delicate

you just may have to

cut off my ear

Unbeknownst to me, I was courting this woman. Through poems. Every day. For a year. She loved the poem. So much so, that she kissed me. Fast forward five years, and she married me. I can track my marriage to the sexiest, smartest woman in the world to an 18-line free verse poem that I wrote on September 1995, which was inspired by 365 free writes I’d written at my boring, soul-stealing job. I guess what I’m trying to say is, poetry can be powerful folks. It definitely was for this man.

Kwame Alexander.

Kwame Alexander is a poet, playwright, producer, and award-winning children’s book author. He regularly speaks, and conducts writing workshops and performances at schools, libraries, and conferences around the country. His Book-in-a-Day writing and publishing program for upper elementary, middle, and high school students has created more than 3000 student authors in sixty schools across the U.S., in Canada, and in the Caribbean. Alexander currently serves as a judge for the National Scholastic Writing Awards and the Virginia Poetry Out Loud competition. He lives with his family in Herndon, Virginia. For more information, visit KwameAlexander.com and you can follow him on Twitter @kwamealexander.

April 11, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Marjorie Agosín: Poetry Pelicans and Celeste Marconi

I grew up with song and poetry in a country that for so many seems to be at the end of the world. Often I did not know if the people around me were singing or reciting. Poetry was a part of our daily lives beginning early in the morning when the house woke up to the sounds of a radio station that recited poetry by aficionados and professionals. In the evenings after finishing dessert my mother recited the poems she had learned and memorized as a young girl so that we too would absorb them and follow the family tradition of reciting. There was something real and organic about the activity of poetry. It was not a chore but a necessary way to engage with the world on a daily basis. Even in our nocturnal hours we always held a book of poems after falling asleep reading. The world I inhabited loved poetry as a way of understanding the inexplicable earthquakes and tsunamis. My mother always told me that when the earth trembles one should write a poem to calm the soul.

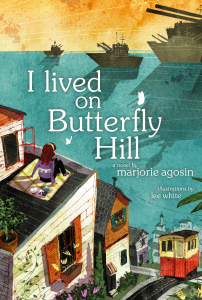

Atheneum Books for Young Readers, March 2014.

I have been a poet from a young age. At first I learned to recite the poems of others such as Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda. I then learned to recite my own verses and write them in colorful pieces of papers that my mother saved for me. I always felt that I was stitching words.

My mother taught me how to look at the intricate details of nature how the stones have faces, how to listen to the orchestra of the sea and to look at it all with a state of wonder. I believe she taught me how to engage in beauty with gratitude as well as awe.

As a young girl I decided to go on a special pilgrimage to Isla Negra to visit the poet Neruda and see him write. The walk was only half an hour but to me it was the most transformative journey in the life I was going to embark on as a young poet. I remember Neruda’s eyes so clearly, his gaze on the horizon and his generosity. He wrote a poem for me called “Bell”. I keep it in my drawer and when I begin writing every morning I look at his handwriting and experience the power of a poet’s words to engage all of us in this world.

I have carried all my mother’s lessons and the image of Pablo Neruda, sitting on a rock wearing a great poncho and writing by hand with a beautiful green ink similar to the forest of my country.

When I was asked by my dear friend Lori Marie Carlson to write a novel for YA I feared I could never do it, I did not want to disappoint her. I never believed I could write such a long novel and work at it everyday for many years. But my friend Lori, my agent Jennifer Lyon and my editor Caitlyn Dlouhy believe in me the way dreamers and poets believe in one another. And after much thought I decided to try this new genre and let my characters’ words guide me.

The principal character in I LIVED ON BUTTERFLY HILL, Celeste Marconi, is a young girl who loves to write. There is something magical and mysterious about Celeste. She enjoys climbing up to the roof of her home in Valparaiso, Chile to observe and name the stars. She is wise beyond her years and understands the world around her when she writes about it. She matures very quickly as her country falls apart due to the overthrow of a freely elected socialist government and then must leave the country becoming an exile for her safety.

Celeste Marconi is able to engage in the world as a new emigrant in a coastal village in Maine because she has a poetic intelligence that allows her to understand beauty and sorrow and appreciate her new solitude in an unfamiliar place. Celeste is able to cope with so much sorrow because she is a poet and diarist and because of the power of her own imagination.

Celeste guided me to the world of poetry from the voice of a young girl. She understood how to interpret signs, such as the howling of the wind or the mystery of an abandoned seashell and understood the life of pelicans. And more importantly Celeste understood that poetry has the power to heal and restores the world.

Marjorie Agosín.

Marjorie Agosín was raised in Chile by Jewish parents. Her family moved to the United States to escape the horrors of the Pinochet takeover of their country. Coming from a South American country and being Jewish, Agosín’s writings demonstrate a unique blending of these cultures. She has received the Letras de Oro Prize for her poetry, presented by Spain’s Ministry of Culture to writers of Hispanic heritage living in the United States. Her writings about, and humanitarian work for, women in Chile have been the focus of feature articles in The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor, and Ms. Magazine. She has also won the Latino Literature Prize for her poetry. She is a Spanish professor at Wellesley College.

April 10, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Suzannah Showler: Poetry on TV

Most professions don’t get a fair shake on TV. Just ask any doctor about Grey’s Anatomy or anyone on Capitol Hill about House of Cards, and they’ll tell you having an affair with a ghost is not a common symptom of a brain tumour, and pushing bloggers in front of trains isn’t a tactic endorsed by policy wonks.

ECW Press, April 2014.

While some jobs go improbably glossy and high-stakes in the limelight, others dress down for media appearances. When a writer turns up on TV or in a movie, he (it’s always a man) is a disheveled university professor in a sweater, and he wrote a great book years ago, but the one he’s currently in the middle of (he’s been working on it for too long) is stalled. Oh yeah, and he writes novels. Never poetry. Who would write poetry?

But poetry does turn up on TV occasionally; it’s just not done by professionals. Mine was a childhood of the 90s, and so a couple of examples of TV poetry that stand out in my memory come from two fine offerings of the early and late end of the decade: Star Trek: The Next Generation and Dawson’s Creek. (I say these are programs from my childhood, but let’s be real: I’ve rewatched episodes of both, like, last month. And for what it’s worth: TNG holds up; Dawson’s Creek very much does not.)

The big poetic moment on the Enterprise comes when Lieutenant Commander Data gives a performance of his poetry (I’ll suspend my disbelief that this is what people do for fun in the twenty-fourth century). Undeterred by yawns from his colleagues, Data recites an ode to his cat, Spot. Data is an android—a machine allegedly incapable of emotion—and this poem, composed in iambic heptameter, is a scientific appraisal of his cat’s capabilities and behaviours. The poem begins: “Felis catus is your taxonomic nomenclature, / An endothermic quadruped, carnivorous by nature.” You can watch Data’s performance here:

Later, having registered, Data asks chief engineer Geordie La Forge to appraise the work. Geordie, hedging, tells him: “Well, it was…very well-constructed. A virtual tribute to form.” But Data pushes him further, asking whether the poems provoked “an emotional response.” When Geordie pauses, Data reminds him that since he has no feelings, Geordie should not be concerned with sparing them. Having admitted that his response to Data’s “clever” poems was not an emotional one, Geordie goes on to give Data this writing advice: “Think more about what you want to say, not how you’re saying it.”

Unlike Data, Dawson’s Creek’s Jack McPhee doesn’t give his performance by choice. Jack is forced by a recalcitrant teacher to recite his poem in front of his Capeside High English class. Little more than a plot device to reveal Jack’s confusion about his sexuality, the poem, entitled “Today,” begins thusly: “Today was a day. / The world got smaller, darker. / I grew more afraid. / Not of what I am, but of what I could be.” (I’ve guessed at these line breaks.) You can watch the performance here:

Poor Jack. His poem is really terrible—far worse than Data’s (which is actually pretty awesome, in its way). Jack’s piece goes on to a kind of short-circuiting of clichés: “I wish I could escape the pain, but these thoughts invade my head. / Bound to my memory, they’re like shackles of guilt.” I was going to do a close-reading, but I think “shackles of guilt” really speaks for itself. Jack might have put all the emotional heft of his teenage turmoil behind his words, but his work is proof positive that thinking about “how you’re saying it” is just as important as the other end of the equation.

As for critical reception, however, Jack’s peers are far more concerned with the issue of what he’s said and take it as an opportunity to spray paint “Fag” on his locker. Still, because Jack is a brooding, artistic type, the issue of quality is assumed. “It’s a beautiful poem,” Jack’s sister, Andie, tells him later. It isn’t at all, but Jack’s pretty pitiable in this episode, so we’ll let it slide.

Both on the Enterprise and in Capeside, poetry is a vehicle through which characters reveal something about themselves they’d not intended to: a lack of feeling on the one hand, and an excess of it on the other. In either case, in the TV version, reading poetry aloud is a quick trip to being humiliated and misunderstood—a way to have the people around you see something about you that you, yourself, are unable to face directly.

I don’t think I can really say that either of these moments of TV inspired me to become a poet. But they also, apparently, didn’t deter me. And if there’s anything useful in them that I took away, it’s that thinking about both what you say and how you say it is probably the best way to go.

Suzannah Showler. (Photo by Stephanie Coffey)

Suzannah Showler’s writing has appeared places, including The Walrus, Hazlitt, The Puritan, and Joyland.She was a finalist for the 2013 RBC Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers from the Writers’ Trust of Canada, and winner of the 2012 Matrix LitPOP Award for Poetry. Her first collection of poetry, FAILURE TO THRIVE, is out this month from ECW Press.

April 9, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Lesa Cline-Ransome: The Poetry of Music

I grew up in a household filled with music. Chords of jazz, blues and R & B set the stage for nearly every meal. Soulful stirrings kept us moving while getting dressed for school. I brushed my teeth to Errol Garner, laced my sneakers to James Brown. My father’s den was a treasure trove of jazz greats. “Listen to this,” my father would say, grabbing anyone passing by, and we’d have to indeed listen, often with feigned interest, as my father sat, foot tapping, eyes closed, lost in the music of Errol Garner, Oscar Peterson or John Coltrane. Not one of us played an instrument and I wouldn’t necessarily say we could carry a tune, but the music from my father’s albums was piped into each room through ceiling speakers throughout our home. I sang as if I were Aretha.

Holiday House, January 2014.

It is the music I was weaned on that dictated the verse for BENNY GOODMAN & TEDDY WILSON: Taking the Stage as the First Black-and-White Jazz Band in History. And it was their duo of harmonious blending of chords and melody that took root in one of the most popular forms of American culture–swing music.

I didn’t set out to write a verse biography. As a writer of many picture book biographies (SATCHEL PAIGE; WORDS SET ME FREE: The Story of Young Frederick Douglass, YOUNG PELE: Soccer’s First Star, HELEN KELLER: The World in Her Heart and MAJOR TAYLOR, CHAMPION CYCLIST), I love the challenge of sifting through a person’s history to pluck out the most interesting parts to translate into a story for young readers. I often look for pieces of a person’s life that reach out to me, for pieces that will resonate with my readers. Finding and living your passions, overcoming adversity and confronting your fears are all themes I’ve visited and revisited in many of my biographies of athletes, and abolitionists and activists, but what to do with musicians? To begin, there were many questions that needed answers.

How was it that the educated son of professors in the rural south teamed up with the uneducated son of Jewish immigrants from Chicago’s West Side? How did a black man and a white man in the 1930’s bridge their own cultural divide to collaborate? And how did audiences young and old, black and white, so willingly accept an integrated band during racially segregated times? The answers were found in the music.

When research began in the form of the Ken Burns’ documentary, Jazz, I listened again to the music of my childhood. The rhythms of “Sing, Sing, Sing, Moonglow” and “Memories of You,” made their way onto the page.

Pop boom pop boom

Above Benny the Fourth of July exploded

One hundred colors, loud ,

live and hot

In front of him the jazz band

clarinet, piano, drums

pop boom pop boom

Benny sat, toe tapping,

Fingers snapping

listening

Outside teddy’s window, birds sang

Tweet drum chirp tweet drum chirp

Inside on the gramophone

Records spinning, needles scratching,

Horns blowing

Duke Ellington, Fats Waller,

Earl Hines on piano

Light as a feather

ting ping tap ting ping tap

Teddy stood, toe tapping,

Fingers snapping,

Listening

HarperCollins, July 2001.

I followed humbly in the footsteps of authors who have written so eloquently and perfectly in the form of verse, I hesitated to dip my toe in their waters. Sharon Creech’s LOVE THAT DOG, Karen Hesse’s OUT OF THE DUST, Ann Burg’s SERAFINA’S PROMISE, and Jeannine Atkins’ were the inspirations behind my words. Much like their beautifully pared down narratives, I too had to step aside and let the music narrate.

And when it did, I felt a lot like the boy in Creech’s LOVE THAT DOG,

I guess it does

Look like a poem

When you see it

Typed up

Like that

Verse is such a beautiful balance of restraint and raw emotion. While I wrote, the sweet tinkle of Teddy’s piano rippled up my spine. The bleating of Benny’s clarinet riveted me.

Fast fingering/drums thumping/trumpets trumping

It wasn’t soft/It wasn’t black

It wasn’t sweet/It wasn’t white

It was swing

As I sat writing at my desk, I was transported to my father’s den, foot tapping, eyes closed, lost in the music. “Listen to this,” I’d plead to my kids who tiptoed past whenever they heard the familiar strains of Benny’s clarinet coming from my office.

Benny’s clarinet high

Blowing looong, then quick

Blowing looong, then quick

Benny blowing

Bleating

Breathing

Music

Into Benny’s clarinet

Notes rippling and rumbling

Onto the dance floor,

Out into the streets

Into Teddy’s piano

Pop boom

Tweet drum

Black, blues

Hot, rhythm

Now it was swing

Music is poetry. Poetry is music. On stage or on the pages of a book, when they come together, it is the most beautiful duo I know.

Lesa Cline-Ransome.

Lesa Cline-Ransome is the author of many picture books for children including SATCHEL PAIGE, YOUNG PELE: Soccer’s First Star, MAJOR TAYLOR, CHAMPION CYCLIST, WORDS SET ME FREE: The Story of Young Frederick Douglass, LIGHT IN THE DARKNESS, and BEFORE THERE WAS MOZART, an NAACP image award nominee. Her newest book, BENNY GOODMAN & TEDDY WILSON: Taking the Stage as the First Black-and-White Jazz Band in History was released this spring.

Many of her books are in collaboration with her husband, and award winning Illustrator, James Ransome (SWEET CLARA AND THE FREEDOM QUILT, UNCLE JED’S BARBERSHOP and THIS IS THE ROPE).

They live in Rhinebeck, New York with their four children and St. Bernard, Nola.

Visit her website and blog pages, www.lesaclineransome.com and http://lclineransome.wordpress.com/.

April 8, 2014

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Christine Heppermann: My Teacher, Mrs. Havlick

Maybe public school kids watched movies like “Apocalypse Now!” all the time during class. Ho-hum, no big deal. But at my all-girls Catholic high school, when the lights clicked off and the VCR—this was 1985—clicked on in Mrs. Havlick’s humanities class, it felt like a dazzling transgression, and not simply because Martin Sheen was shirtless and took the Lord’s name in vain. It felt the same way when Mrs. Havlick assigned us to read A PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN, or poetry by Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, and Adrienne Rich. We were teenagers—just teenagers in the eyes of so many adults. Yet Mrs. Havlick sent us “Diving Into the Wreck.” She flung us into a sea of new, some would say provocative ideas and trusted us to swim.

Greenwillow Books, September 2014.

We also watched “My Dinner with Andre,” and though I hadn’t expected at age seventeen to fall madly in love with a long dinner conversation between two middle-aged men, I fell hard. At one point the main characters, Wally and Andre, argue about electric blankets. Wally says he’d never give them up because they provide comfort and “our life is tough enough as it is.” Andre counters, “But, Wally, don’t you see that comfort can be dangerous? I mean, you like to be comfortable, and I like to be comfortable, too, but comfort can lull you into a dangerous tranquility.” Yes! I thought. That’s exactly what humanities class was doing for me: unplugging my blanket. Waking me up.

Once Mrs. Havlick loaned me a book, I’ve long since forgotten which one, and tucked inside, like a secret message, was a scrap of paper covered in her spiky handwriting. It was a poem, or at least the first few stanzas of a poem. Judging from the cross-outs, she didn’t consider it finished, nor had she intended me to see it.

I remember being struck by the poem’s essential analogy, which used clothing to represent the constraints of everyday life. I could certainly relate. I’d worn a school uniform since the first grade. My skirt had to be the exact-right plaid. My socks must not draw undo attention to themselves. My cardigan had to be navy blue, not royal, or midnight, or robin’s egg. I was a walking metaphor!

On a deeper level, I also felt constrained by expectations—my parents’, my schools’, my religions.’ You name it. As far as appearances showed, I was exactly who I was supposed to be: a good girl who got good grades and went to mass on Sundays. Where was the daringness in that?

Often I fantasized about escaping, the way Stephen Dedalus escaped Ireland in A Portrait of the Artist, although, as Mrs. Havlick tactfully pointed out, I could not, in a college application essay, compare my caged intellect to James Joyce’s without sounding the teensiest bit pretentious.

Even back then I could tell that teaching high-school English and journalism wasn’t Mrs. Havlick’s dream job. She treated us like college students in part, I suspected, because she wished that’s what we were. I still remember the pride in her voice when she told us that she’d shown our essays on Lord Jim to a professor friend, and he’d deemed them as good as or better than anything his students ever produced. Would she rather have been striding the marble halls of academia instead of supervising the yearbook staff’s bake sale? Probably. But she stuck with us and taught us, by example and through the films and literature she shared, to value questions over answers. She taught us to push at the boundaries. She encouraged us—and I don’t consider this an overstatement— to be free.

I can honestly say I don’t think I’d be a poet today without her. It’s been decades since I tossed out my high-school poetry journals because they made me cringe. But at the time I took those poems very seriously, and Mrs. Havlick did, too. When I was wait-listed at the college of my choice, she was almost more upset than I was. She invited me over to her house on a Saturday afternoon to help me revise a batch of poems to send to the admissions committee. My brilliant verse would force them to realize their egregious mistake in not admitting me the first time around, right? Wrong. I never did get in. Still, I was grateful for her faith in me. I am grateful for her faith in me.

When you think about it, what better lesson could a poet learn than the ability to work within constraints? Robert Frost has that famous line about how writing free verse is like playing tennis without a net. But whether written in free verse or forms, poetry is all about using a small amount of space to say something big. Just as Mrs. Havlick used that stuffy box of a third-floor classroom to open our minds to the big, scary, complicated, dazzling world.

Christine Hepperman. (Photo by Eric Hinsdale.)

Christine Heppermann is the author of the forthcoming POISONED APPLES: Poems for You, My Pretty. She has been a columnist and reviewer for the Horn Book and has reviewed children’s and young adult books for the New York Times, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, and the San Antonio Express News, among others. She has an MA in Children’s Literature from Simmons College and an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Hamline University. She lives with her husband and two daughters in Highland, NY.