National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Sean Cummings: Lest We Forget

Strange Chemistry, September 2013.

I write bubble gum.

So what is an author with five books about zombies, poltergeists, soul worms and generally fantastical stuff writing a blog posting about poetry for? Because even though I am the world’s worst poet (seriously, my poems would make your eyes bleed) I can’t discount or diminish the importance of poetry to the human experience.

Among the most powerful poems are the ones penned in the trenches during the First World War. My favorite WWI poet is Wilfred Owen. His unforgettable “Dulce et Decorum Est,” for me at least, paints the most vivid picture of the battlefields of France and Belgium:

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!–An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.–

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin,

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs

Bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,–

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

We are many generations removed from a conflict that lay waste to the old imperial houses of Europe and claimed the lives of millions in a wholesale industrial slaughter that even now, one hundred years later, seems almost impossible to envision.

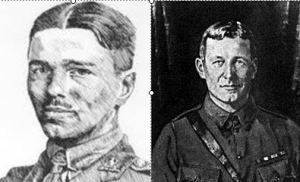

Wilfred Owen & John McRae.

As a Canadian, and a proud veteran of my country’s armed forces, I feel drawn to try and make sense of the First World War because it was on the murderous terrain of No Man’s Land that my country forged its national identity. It has been said the Battle of Vimy Ridge was the place where Canada came of age as a nation because this blasted escarpment that no allied force could capture was successfully taken by Canadian soldiers on Easter Monday 1917. Canada at that time wasn’t even fifty years old. For the first time in the war, all four divisions of Canadian troops fought side by side. They captured the ridge, albeit at a horrendous cost. 3598 Canadian soldiers were killed and another 7000 were wounded. (Canada’s population at that time was little more than 8 million people.)

Canada has always been a big country with a small population. Even now, one hundred years after the start of the conflict, we number only 35 million. Nearly 60,000 Canadians died during those four years of war – a staggering number. Perhaps it is because of my country’s sacrifice during WWI that to this day, Canadian Colonel John McCrae’s poem “In Flander’s Fields” urges us to always remember those who lost their lives.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

On November 11th each year, Canadians gather around cenotaphs in every major city or tiny village across the country. A bugler will sound off The Last Post and someone will read McCrae’s stirring poem that has become an enduring symbol of Canada’s nationhood.

And whenever I hear it being read, I often wonder what it means to Canadians. I wonder if wet truly understand what drove both Owen and McCrae to write the poems in the first place.

Wilfred Owen was an infantry soldier. McCrae was a field surgeon. Owen went “over the top” while McCrae tried to save the lives of the wounded and dying. The contrast here isn’t lost on me and it might be because of their different roles in the war that Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est is an indictment against the generals who ordered men to die by the tens of thousands in full frontal assaults time and time again, and the governments for allowing war to happen in the first place.

McCrae, on the other hand, speaks of passing the torch and taking the quarrel to the foe. It is a patriotic urging to carry on the fight. It acknowledges the sacrifice and speaks for the dead who no longer have a voice. Two different men, two different poets, and two different interpretations of living and dying on the Western Front.

The war claimed both Wilfred Owen and John McCrae. It claimed the lives of more than 16 million people, again, an almost inconceivable number for a generation that hasn’t been touched by total war. There are no Canadians left alive now who fought in the trenches. The last Canadian First World War veteran died in 2010 at age 109 and those few remaining Second World War veterans are now well into their 90’s.

These poems, all war poems, really, are to me at least, a testament to the toll war takes on the human soul. They are personal accounts to look for a deeper meaning to death and carnage.

Each year on Remembrance Day there are wreaths that say “lest we forget”. For those who haven’t been touched by war and cannot comprehend the sheer magnitude of both world wars, the enduring challenge is no longer to remember those who fought died in the mud of the trenches, but rather, to try and understand.

Sean Cummings.

Sean Cummings is a fantasy author with a penchant for writing quirky, humorous and dark novels featuring characters that are larger than life. His debut was the gritty urban fantasy SHADE FRIGHT published in 2010. He followed up later in the year with the sequel FUNERAL PALLOR. His urban fantasy/superhero thriller UNSEEN WORLD was published in 2011.

2012 saw the publication of Sean’s first urban fantasy for young adults. POLTERGEEKS is a rollicking story about teen witch Julie Richards, her dorky boyfriend and a race against time to save her mother’s life. The first sequel, STUDENT BODIES is now available at bookstores everywhere. He lives in Saskatoon, Canada.