David Williams's Blog, page 5

May 11, 2012

Daft and illogical song lyrics - Part 2

Here’s a coincidence. For some time I have been collecting a second instalment of daft and illogical song lyrics to add to the ones I posted on a earlier blog post - the coincidence is that when I searched my blog archives to create a link to the earlier post I found I’d delivered that first one exactly one year ago. There you go.

Hope you enjoy this second instalment. Click on the tracks to listen to the songs via Spotify.

I looked at the skies, running my hands over my eyes,

and I fell out of bed, hurting my head from things that I'd said.

Bee Gees – I Started A Joke

(Where do I start? Everything is wrong about this. More than one sky to look at; looking at skies while running hands over eyes; and conflicting reasons given for a hurting head - not bad for two lines.)

She ain’t no witch

And I love the way she twitch, Ah-ha-ha.

T. Rex – Hot Love

(Just - daft.)

Words are very unnecessary

Depeche Mode – Enjoy the Silence - Single Version;2006 - Remaster

(Things are either unnecessary or they aren’t)

If Paradise was half as nice as heaven that you take me to,

Who need Paradise, I’d rather have you.

Amen Corner – (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice

(Well, yes, you would prefer her if Paradise was only half as nice – statement of the obvious)

Tonight there’s gonna be a jailbreak

Somewhere in this town.

Thin Lizzy – Jailbreak

(I wonder where exactly in town a jailbreak might take place)

She called him Speedoo, but his Christian name was Mr Earl

Paul Simon – Was A Sunny Day

(So what was his surname, Paul?)

If you have any examples you’d like to share, please use Comments to pass them on.

Published on May 11, 2012 07:17

May 2, 2012

Coalhouse Door re-opens

I have written in an earlier post about my teenage exposure to repertory theatre - walking from Newcastle's Haymarket Station a couple of miles to the Flora Robson Playhouse to see whatever production had just opened - and especially at my delight and inspiration in seeing the original 1968 production of Alan Plater's 'Close the Coalhouse Door' with music by Alex Glasgow and featuring such great North East actors as John Woodvine, James Garbutt and (Bolton-born, but with an Auntie Bella in Gateshead) Bryan Pringle. The play was not only locally successful but briefly went to the West End courtesy of Brian Rix, and turned up on TV as an unforgettable Wednesday Play with most of the original cast.

The original cast of 'Close the Coalhouse Door'

The original cast of 'Close the Coalhouse Door'

A scene from the 1969 TV production with Dudley Foster as The Expert, Geraldine Moffat as Ruth and Alan Browning as John Milburn

A scene from the 1969 TV production with Dudley Foster as The Expert, Geraldine Moffat as Ruth and Alan Browning as John Milburn

The Flora Robson Playhouse was demolished in 1971 to make way for a new road. The new home of the Tyne Theatre Company was the University Theatre, a much shorter walk from the Haymarket. A couple of renames later, with some refurbishment and a new front entrance at the side, the theatre currently houses Northern Stage. Last night I was among a packed audience in the theatre enjoying a revival of 'Close the Coalhouse Door'. It was a memorable evening of laughter and tears.

Alan Plater, who updated the play a couple of times for earlier revivals, sadly died in 2010, but the minor updating for this production fell into the capable hands of Lee Hall (of 'Billy Elliot' and 'Pitmen Painters' fame). Hall gives us two superb images - at the beginning with a poster of Meryl Streep as Mrs Thatcher given extra devillish quality when two miners' lamps are shone through her eyes; and at the end with a slick transformation of the whole cast into call centre workers to demonstrate the death of the mining industry.

There is a wonderful revolving set too by Soutra Gilmour, and Sam West's direction is lively and gorgeously irreverent, with the fourth wall regularly and gleefully punched through by actors whose quick-fire repartee includes the audience at every excuse for an ad lib.

Mostly though it's Plater's script, Glasgow's music, and the players' interpretation of both that make the show so engaging you could hug yourself and them and the guy in the next seat who you don't know but who is obviously enjoying the experience as much as we all are.

Chris Connel as Jackie, Jane Holman as Mary in the 2012 Northern Stage revival

Chris Connel as Jackie, Jane Holman as Mary in the 2012 Northern Stage revival

I have rarely seen a cast so versatile. Not only could they switch instantly from their anchor roles in the play to produce hilarious cameos of key figures on both sides of the miners' struggle (including a Harold Wilson so simply and effectively sketched that it brought spontaneous laughter and applause from the audience at first glance); they could also sing, dance and play music at a level on a par with their acting - guitars, bass, drums, piano, flute, penny whistle, violin, concertina, washboard and some other instrument which seemed to be some form of autoharp. They didn't always need traditional instruments either - one of the best percussion accompaniments came from Mary Milburn's knitting needles as she danced around tapping them on various parts of the set, while bottles, glasses and packing cases were all used to great effect; a veritable scratch orchestra. The songs were variously stirring, foot-tapping, comic and poignant. Of the latter Ruth's lament for a lost baby had me in tears, while the various treatments of the title song 'Close the Coalhouse Door' summed up all the anger and bitterness that lies behind the story as it is unfurled on stage - anger which we are rightly left with in spite (or perhaps because) of all the fun and laughter we've enjoyed at the Milburns' golden wedding celebration.

At the end of the play we returned from the auditorium past a sombre display of black and white pictures of the 1984 miners' strike and the official retaliation, shot on the streets in the colliery villages of County Durham. The bitterness evident in those pictures and at times on stage is not all we take away, however, for Plater's story is fundamentally life-affirming, and we have this great generous cast to thank for reminding us of the great generous heart of our mining community. It is as much to cherish as to grieve.

The original cast of 'Close the Coalhouse Door'

The original cast of 'Close the Coalhouse Door' A scene from the 1969 TV production with Dudley Foster as The Expert, Geraldine Moffat as Ruth and Alan Browning as John Milburn

A scene from the 1969 TV production with Dudley Foster as The Expert, Geraldine Moffat as Ruth and Alan Browning as John MilburnThe Flora Robson Playhouse was demolished in 1971 to make way for a new road. The new home of the Tyne Theatre Company was the University Theatre, a much shorter walk from the Haymarket. A couple of renames later, with some refurbishment and a new front entrance at the side, the theatre currently houses Northern Stage. Last night I was among a packed audience in the theatre enjoying a revival of 'Close the Coalhouse Door'. It was a memorable evening of laughter and tears.

Alan Plater, who updated the play a couple of times for earlier revivals, sadly died in 2010, but the minor updating for this production fell into the capable hands of Lee Hall (of 'Billy Elliot' and 'Pitmen Painters' fame). Hall gives us two superb images - at the beginning with a poster of Meryl Streep as Mrs Thatcher given extra devillish quality when two miners' lamps are shone through her eyes; and at the end with a slick transformation of the whole cast into call centre workers to demonstrate the death of the mining industry.

There is a wonderful revolving set too by Soutra Gilmour, and Sam West's direction is lively and gorgeously irreverent, with the fourth wall regularly and gleefully punched through by actors whose quick-fire repartee includes the audience at every excuse for an ad lib.

Mostly though it's Plater's script, Glasgow's music, and the players' interpretation of both that make the show so engaging you could hug yourself and them and the guy in the next seat who you don't know but who is obviously enjoying the experience as much as we all are.

Chris Connel as Jackie, Jane Holman as Mary in the 2012 Northern Stage revival

Chris Connel as Jackie, Jane Holman as Mary in the 2012 Northern Stage revival I have rarely seen a cast so versatile. Not only could they switch instantly from their anchor roles in the play to produce hilarious cameos of key figures on both sides of the miners' struggle (including a Harold Wilson so simply and effectively sketched that it brought spontaneous laughter and applause from the audience at first glance); they could also sing, dance and play music at a level on a par with their acting - guitars, bass, drums, piano, flute, penny whistle, violin, concertina, washboard and some other instrument which seemed to be some form of autoharp. They didn't always need traditional instruments either - one of the best percussion accompaniments came from Mary Milburn's knitting needles as she danced around tapping them on various parts of the set, while bottles, glasses and packing cases were all used to great effect; a veritable scratch orchestra. The songs were variously stirring, foot-tapping, comic and poignant. Of the latter Ruth's lament for a lost baby had me in tears, while the various treatments of the title song 'Close the Coalhouse Door' summed up all the anger and bitterness that lies behind the story as it is unfurled on stage - anger which we are rightly left with in spite (or perhaps because) of all the fun and laughter we've enjoyed at the Milburns' golden wedding celebration.

At the end of the play we returned from the auditorium past a sombre display of black and white pictures of the 1984 miners' strike and the official retaliation, shot on the streets in the colliery villages of County Durham. The bitterness evident in those pictures and at times on stage is not all we take away, however, for Plater's story is fundamentally life-affirming, and we have this great generous cast to thank for reminding us of the great generous heart of our mining community. It is as much to cherish as to grieve.

Published on May 02, 2012 07:22

April 28, 2012

Who do writers write for? (or) For whom do writers write?

Modern marketing began with the notion that, instead of making a product then trying to find customers to buy it, it would be more effective to find out what the customer needs or desires then make a product to supply that need or desire.

Fair enough, but does it work with the writing product - books, plays, media? I guess it must to a degree, judging by the millions spent globally on focus groups, trend-spotting and other techniques in search of what might be the next big thing.

There are at least two problems, though. The first is that the customer is a rear view mirror - what you get from looking closely at customer behaviour and opinion is not so much the next big thing as the last big thing. How can customers desire what they don’t yet know exists? That must be an even bigger problem for considering products of the imagination than it is for considering products of, say, technology, which tend to work more by accretion than departure.

The second problem is that the product of aggregated opinion must be cliché. By definition, work that is predicated on the predicted must be predictable. In other words, writing out of focus group wisdom is bound to produce the same old pap however thinly disguised in next year’s colour.

So, if we are not writing for the ‘customer’ as made flesh by the marketeers, who are we writing for? ‘Write for yourself’ is sound advice I’ve heard many times, coupled with ‘Write what you know’. To take my own modest case, without it I would not have produced my semi-autobiographical collection of short stories We Never Had It So Good , nor indeed many of the plays for schools earlier in my writing career. Dickens produced some of his best work engaging with and writing from his personal experience, as have so many others - Alan Bennett, to settle on a modern example - but these maxims, useful as they are, set their own boundaries. There is a limit to writing out of yourself, while writing for yourself could restrict you to an audience of one. What would Shakespeare have achieved if he had left himself so confined?

I believe the best we can do is to write for the seeker. Instead of trying to analyse trends or aping yesterday’s successes we need to ask ourselves what is capturing the thoughts (or stoking the anxieties) of humanity now and for the future. Much of our impulse forward is fuelled by a sense of searching for something - often ill-defined, sometimes intangible, but nevertheless there. What is the object of that search; what can we say about the journey?

These are questions that are useful for writers of fact and fiction. They provide a motive force for our research and can drive our writing. Addressing these questions can be so much more liberating than merely writing what we know, and edifying too. As the author Simon Brett pointed out at a recent Authors North event I attended, the full-time writer, cut off from a normal working environment, knows less and less. Writing for the seeker give us a certain impetus to find out what we don’t know. Our efforts to answer the seeker’s questions lucidly will help shape the work we do, and we can demonstrate our qualities to the extent we are able to define what was ill-defined, make tangible the intangible.

Of course the seeker and the writer may be one - taking us back to the notion of ‘write for yourself’ - but the broader concept of write for the seeker offers infinite possibilities on so many levels - personal; interpersonal; societal; global; universal - as well as a forward dynamic and a natural structural fit with the idea of the story or argument as a quest, a journey, an unfolding.

For me there is also a sense of companionship, if only a virtual one, in the idea of writing for the seeker, a realised image of the reader as fellow-passenger on the journey, one for whom I have responsibility throughout and must navigate to our mutual destination across all the obstacles, working with a map that seems to be missing significant parts of the route, overcoming challenges on the way. I may be the guide but, as in all good quests, neither of us could make it to the end without the other.

Finally (to throw the marketeers a bone) there is a commercial rationale. Bookshops, libraries and on-line repositories are natural haunts for seekers of all bent and persuasion. If we have anticipated and successfully engaged with the objects of their search in the works we have created, they will surely find us there.

Published on April 28, 2012 05:24

April 20, 2012

Write wit 2

Way back in December 2010 I wrote a blog posting of quotations about writers and writing Write wit. It seemed to go down well, so here are some more offerings of the same - a sequel, as it were.

“If we wait for the moment when everything, absolutely everything is ready, we shall never begin.”

Ivan Turgenev

“I just sit at a typewriter and curse a bit.”

P G Wodehouse

"It is necessary to write, if the days are not to slip emptily by. How else, indeed, to clap the net over the butterfly of the moment?"

Vita Sackville-West

Vita Sackville West

Vita Sackville West

“Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way."

E L Doctorow

“Writing is a socially acceptable form of schizophrenia.”

E L Doctorow

"There are plenty of clever young writers. But there is too much genius, not enough talent."

J B Priestley

"Practically everybody in New York has half a mind to write a book, and does."

Groucho Marx

"A good many young writers make the mistake of enclosing a stamped, self-addressed envelope big enough for the manuscript to come back in. This is too much of a temptation for the editor."

Ring Lardner

"Clutter is the disease of American writing. We are a society strangling in unnecessary words, circular constructions, pompous frills and meaningless jargon."William Zinsser

“One thing that literature would be greatly the better for

Would be a more restricted employment by authors of simile and metaphor.”

Ogden Nash

Ogden Nash

Ogden Nash

“If you steal from one author it’s plagiarism; if you steal from many it’s research.”

Wilson Mizner

“Every writer is a frustrated actor who recites his lines in the hidden auditorium of his skull.”

Rod Serling

“Television has raised writing to a new low.”

Samuel Goldwyn

"Most rock journalism is people who can't write interviewing people who can't talk for people who can't read."Frank Zappa

"Writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down.”

Robert Frost

“Those big-shot writers could never dig the fact that there are more salted peanuts consumed than caviar.”

Mickey Spillane

“I am the kind of writer that people think other people are reading.“

V S Naipaul

"When I was a little boy, they called me a liar, but now that I am grown up, they call me a writer."

Isaac Singer

"People want to know why I do this, why I write such gross stuff. I like to tell them I have the heart of a small boy - and I keep it in a jar on my desk."

Stephen King

Stephen King “I'm a lousy writer; a helluva lot of people have got lousy taste.”

Stephen King “I'm a lousy writer; a helluva lot of people have got lousy taste.”

Grace Metalious

"I was thirty-seven when I went to work writing the column. I was too old for a paper route, too young for Social Security, and too tired for an affair."

Erma Bombeck

"If you want to get rich from writing, write the sort of thing that's read by persons who move their lips when they're reading to themselves."

Don Marquis

"There are men who can write poetry, and there are men who can read balance sheets.The men who can read balance sheets cannot write."

Henry R Luce

"If writers were good businessmen, they'd have too much sense to be writers."

Irvin S Cobb

“Some day I hope to write a book where the royalties will pay for the copies I give away.”

Clarence Darrow

“Writing is turning one's worst moments into money.”

J P Donleavy

“Income tax returns: the most imaginative fiction written today.”

Herman Wouk

“No passion in the world is equal to the passion to alter someone else's draft.”

H G Wells

“Honest criticism is hard to take, particularly from a relative, a friend, an acquaintance, or a stranger.”

Franklin P Jones

“Be kind and considerate with your criticism. It's just as hard to write a bad book as it is to write a good book.”

Malcolm Cowley

“Do we write books so that they shall merely be read? Don't we also write them for employment in the household? For one that is read from start to finish, thousands are leafed through, other thousands lie motionless, others are jammed against mouseholes.”

G C Lichtenberg

“I can't understand why a person will take a year to write a novel when he can easily buy one for a few dollars.”

Fred Allen

“Ordering a man to write a poem is like commanding a pregnant woman to give birth to a red-headed child.”

Carl Sandburg

“Either write something worth reading or do something worth writing.”

Benjamin Franklin

"The artist is extremely lucky who is presented with the worst possible ordeal which will not actually kill him. At that point, he's in business."

John Berryman

“I did not write it. God wrote it. I merely did his dictation.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe "When all things are equal, translucence in writing is more effective than transparency, just as glow is more revealing than glare."

Harriet Beecher Stowe "When all things are equal, translucence in writing is more effective than transparency, just as glow is more revealing than glare."

James Thurber

"There is a difference between a book of two hundred pages from the very beginning, and a book of two hundred pages which is the result of an original eight hundred pages. The six hundred are there. Only you don't see them."

Elie Wiesel

"It is all very well to be able to write books, but can you waggle your ears?"

J M Barrie

If you enjoyed these you might like to view my first Write wit post here.

“If we wait for the moment when everything, absolutely everything is ready, we shall never begin.”

Ivan Turgenev

“I just sit at a typewriter and curse a bit.”

P G Wodehouse

"It is necessary to write, if the days are not to slip emptily by. How else, indeed, to clap the net over the butterfly of the moment?"

Vita Sackville-West

Vita Sackville West

Vita Sackville West“Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way."

E L Doctorow

“Writing is a socially acceptable form of schizophrenia.”

E L Doctorow

"There are plenty of clever young writers. But there is too much genius, not enough talent."

J B Priestley

"Practically everybody in New York has half a mind to write a book, and does."

Groucho Marx

"A good many young writers make the mistake of enclosing a stamped, self-addressed envelope big enough for the manuscript to come back in. This is too much of a temptation for the editor."

Ring Lardner

"Clutter is the disease of American writing. We are a society strangling in unnecessary words, circular constructions, pompous frills and meaningless jargon."William Zinsser

“One thing that literature would be greatly the better for

Would be a more restricted employment by authors of simile and metaphor.”

Ogden Nash

Ogden Nash

Ogden Nash“If you steal from one author it’s plagiarism; if you steal from many it’s research.”

Wilson Mizner

“Every writer is a frustrated actor who recites his lines in the hidden auditorium of his skull.”

Rod Serling

“Television has raised writing to a new low.”

Samuel Goldwyn

"Most rock journalism is people who can't write interviewing people who can't talk for people who can't read."Frank Zappa

"Writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down.”

Robert Frost

“Those big-shot writers could never dig the fact that there are more salted peanuts consumed than caviar.”

Mickey Spillane

“I am the kind of writer that people think other people are reading.“

V S Naipaul

"When I was a little boy, they called me a liar, but now that I am grown up, they call me a writer."

Isaac Singer

"People want to know why I do this, why I write such gross stuff. I like to tell them I have the heart of a small boy - and I keep it in a jar on my desk."

Stephen King

Stephen King “I'm a lousy writer; a helluva lot of people have got lousy taste.”

Stephen King “I'm a lousy writer; a helluva lot of people have got lousy taste.” Grace Metalious

"I was thirty-seven when I went to work writing the column. I was too old for a paper route, too young for Social Security, and too tired for an affair."

Erma Bombeck

"If you want to get rich from writing, write the sort of thing that's read by persons who move their lips when they're reading to themselves."

Don Marquis

"There are men who can write poetry, and there are men who can read balance sheets.The men who can read balance sheets cannot write."

Henry R Luce

"If writers were good businessmen, they'd have too much sense to be writers."

Irvin S Cobb

“Some day I hope to write a book where the royalties will pay for the copies I give away.”

Clarence Darrow

“Writing is turning one's worst moments into money.”

J P Donleavy

“Income tax returns: the most imaginative fiction written today.”

Herman Wouk

“No passion in the world is equal to the passion to alter someone else's draft.”

H G Wells

“Honest criticism is hard to take, particularly from a relative, a friend, an acquaintance, or a stranger.”

Franklin P Jones

“Be kind and considerate with your criticism. It's just as hard to write a bad book as it is to write a good book.”

Malcolm Cowley

“Do we write books so that they shall merely be read? Don't we also write them for employment in the household? For one that is read from start to finish, thousands are leafed through, other thousands lie motionless, others are jammed against mouseholes.”

G C Lichtenberg

“I can't understand why a person will take a year to write a novel when he can easily buy one for a few dollars.”

Fred Allen

“Ordering a man to write a poem is like commanding a pregnant woman to give birth to a red-headed child.”

Carl Sandburg

“Either write something worth reading or do something worth writing.”

Benjamin Franklin

"The artist is extremely lucky who is presented with the worst possible ordeal which will not actually kill him. At that point, he's in business."

John Berryman

“I did not write it. God wrote it. I merely did his dictation.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe "When all things are equal, translucence in writing is more effective than transparency, just as glow is more revealing than glare."

Harriet Beecher Stowe "When all things are equal, translucence in writing is more effective than transparency, just as glow is more revealing than glare."James Thurber

"There is a difference between a book of two hundred pages from the very beginning, and a book of two hundred pages which is the result of an original eight hundred pages. The six hundred are there. Only you don't see them."

Elie Wiesel

"It is all very well to be able to write books, but can you waggle your ears?"

J M Barrie

If you enjoyed these you might like to view my first Write wit post here.

Published on April 20, 2012 04:15

April 12, 2012

Entertainment fills, art resonates

As a young man many years ago (OK, late 1970s) I was recruited by Wansbeck Council as their first Arts & Entertainments Officer. One of the questions they asked me at the interview was, what is the distinction between the two? I think I made some blandly vague answer about the difference being in the eyes of the beholder, and that one often slid into the other. The reply must have satisfied at some level since they hired me. Nearly forty years on, the question has popped into my brain again - I've no idea why - along with the sort of answer that when I have been drinking I might grab onto as a Eureka moment (should it be 'an Eureka moment'?), only to wake up in the morning and dismiss as meaningless toss (should that be tosh? I quite like toss).

I haven't been drinking (despite interrupting myself in parentheses) and it's still a(n) Eureka moment to me, so I'll state it below, with my name added to lay full claim to ownership:

Entertainment fills, art resonatesDavid Williams

I thought of tweeting the distinction and leaving it at that, but I guess it needs a little clarification; hence this short blog post.

We all need diversion, it seems - whether to relieve us from our labours, provide a temporary escape, alleviate boredom, help us socialise with our friends, or simply to fill in the time between the tick and the tock of our lives. That's how entertainment started, and that still pretty much describes its role, in whatever form the entertainment comes. It can be variable in quality, it can be something done to us (as audience) or that we do ourselves (as participants) or both at once, but essentially entertainment fills these gaps in our time and community. Entertainment can both fill and, at its best, be fulfilling.

Art does more; and entertainment transmutes to art when, on occasion, it does more. Art does not just fill the moment, does not end at the end - it goes on. Think of the moments after a superb piece of music has played; after the curtain comes down on a wonderful theatre or dance performance; the sensation that remains when the great novel is ended and returned to the shelf; when the doors are closed on the great artist's exhibition. The resonance may be at its most intense immediately after the direct experience (sensed as a wave of bliss, or grief, or passion, or revelation) and the resonance carries on, less intensely but perhaps more deeply, sometimes deep enough to make a groove in the rest of your life, to have an effect on your apprehension, your understanding and your response to future experiences in art and life.

Of course not all art will resonate with all individuals, far from it - we each carry our personal arts centre within ourselves - but one of the tests of great art is the power it has for creating resonance among a sizeable community of individuals and (rather like valency bonds in science if I understand the theory correctly) to bond them in accord, a shared acknowledgement of that greatness. It is through such resonance that our giants of art - our Leonardo, Shakespeare, Goethe, Beethoven, Tolstoy and others - came to be so memorialised.

Does this distinction resonate with readers out there? Let me know.

I haven't been drinking (despite interrupting myself in parentheses) and it's still a(n) Eureka moment to me, so I'll state it below, with my name added to lay full claim to ownership:

Entertainment fills, art resonatesDavid Williams

I thought of tweeting the distinction and leaving it at that, but I guess it needs a little clarification; hence this short blog post.

We all need diversion, it seems - whether to relieve us from our labours, provide a temporary escape, alleviate boredom, help us socialise with our friends, or simply to fill in the time between the tick and the tock of our lives. That's how entertainment started, and that still pretty much describes its role, in whatever form the entertainment comes. It can be variable in quality, it can be something done to us (as audience) or that we do ourselves (as participants) or both at once, but essentially entertainment fills these gaps in our time and community. Entertainment can both fill and, at its best, be fulfilling.

Art does more; and entertainment transmutes to art when, on occasion, it does more. Art does not just fill the moment, does not end at the end - it goes on. Think of the moments after a superb piece of music has played; after the curtain comes down on a wonderful theatre or dance performance; the sensation that remains when the great novel is ended and returned to the shelf; when the doors are closed on the great artist's exhibition. The resonance may be at its most intense immediately after the direct experience (sensed as a wave of bliss, or grief, or passion, or revelation) and the resonance carries on, less intensely but perhaps more deeply, sometimes deep enough to make a groove in the rest of your life, to have an effect on your apprehension, your understanding and your response to future experiences in art and life.

Of course not all art will resonate with all individuals, far from it - we each carry our personal arts centre within ourselves - but one of the tests of great art is the power it has for creating resonance among a sizeable community of individuals and (rather like valency bonds in science if I understand the theory correctly) to bond them in accord, a shared acknowledgement of that greatness. It is through such resonance that our giants of art - our Leonardo, Shakespeare, Goethe, Beethoven, Tolstoy and others - came to be so memorialised.

Does this distinction resonate with readers out there? Let me know.

Published on April 12, 2012 02:29

March 29, 2012

I'm not sleeping, I'm working

I've reproduced below the full text of an article I wrote for the Spring 2012 issue of The Author, the magazine of the Society of Authors. In the magazine the article is entitled The Thinker. I prefer to use my original title I'm not sleeping, I'm working.

The reason I am writing this article at this moment is not so much to share my thoughts as to appear busy at the computer screen should my wife walk into the room right now. Today, as yesterday, she is downstairs alternately painting the hall and sanding the kitchen chairs. Yesterday I was lying on top of our bed thinking through a storyline. When I came down to show willing, ask if she'd like a cup of tea, she let me know how she'd heard my snoring as she painted.

It's true I had dropped off for a few seconds or, as I prefer to think of it, had so far sunk into a creative reverie that my unconscious had briefly taken over, plunged deeper into the world my imagination had opened. Well, it does happen sometimes, but I must admit that yesterday I'd plain fallen asleep, having bored myself into blank submission.

Her painting, you see, was to blame. How could I tease a tale of hope from workhouse iniquity (my latest vague idea for a novel) with the smell of fresh paint drifting through and the noise of brush on wall? I was distracted by guilt. Couldn't think for it. Eventually my consciousness closed down on my conscience, salved on waking by my offer of tea.

My wife puts me to shame. The thing is, her industry is so damn visible. Not to mention practical and useful; vital, even. Mine is none of these, unless you count stacking the dishwasher. The only time I achieve visibility is on the publication of a book or (mere squib) an article. Such products are so rare as to make some of my acquaintance doubt if I'm really doing anything that could be counted as work at all.

Every Sunday I go to watch a junior football team my son manages, and every week the same parent sidles along the touchline to ask, 'So, what are you working on at the moment, David?' 'Oh, still the Stephenson book,' has been my stock answer for the last two years. This man runs a plumbing business. He probably fits or fixes twenty bathrooms a month. It has never crossed my mind to ask, 'So, what are you working on at the moment, Michael?' Perhaps he's waiting for the day.

Some people seem able to think while doing other things - visible things. Gladstone apparently liked to chop down trees as he pondered great matters of state, though whether he profited from the sale of logs afterwards history does not reveal. I really wish I could do that. I'd sweep leaves off the garden, pausing briefly every now and then to wave at my wife through the kitchen window. I'd sand furniture, even decorate the house while mentally composing chapters for my book... but I know from trying (honest, I have) that my brain fastens onto the tedium of the task, the brush-brush-brush repeating-repeating on the inside of my skull. I can't even go for a walk without fixating on footsteps. Thank Apple for iPod, though I can't think to music either except about the music.

Over the years I have tried a variety of techniques for kick-starting creativity – automatic writing, prop pile, keyword dip, collaborative writing, role play... so many that I used to package and sell them to corporate trainers at inflated prices, thereby paying the bills while I continued my search for one that worked for me – and I have discovered there is only one authentic Williams method. I lie flat in a perfectly quiet, preferably darkened room, close my eyes, and think.

Even to a trained observer (let's say David Attenborough, or my wife) this activity is indistinguishable from sleep. I could be a sloth. Ironically, the better it's working the more like sleep it seems. In deep thinking mode I'm oblivious to someone walking into the room, to a gentle enquiry, a tut. Like a finely-tuned sports professsional (hah) I'm in the zone.

And in good company too. Vincent Van Gogh said of his creative technique, 'I dream my painting and then I paint my dream.' Judging by his output (over 2,000 works) he must have put in a lot of dreaming. I wonder who did his decorating. Come to think of it my wife used to paint pictures, years ago, before the housework took over... Hmm, I'm beginning to feel guilty again. Perhaps it's time I went downstairs. Put the kettle on.

The reason I am writing this article at this moment is not so much to share my thoughts as to appear busy at the computer screen should my wife walk into the room right now. Today, as yesterday, she is downstairs alternately painting the hall and sanding the kitchen chairs. Yesterday I was lying on top of our bed thinking through a storyline. When I came down to show willing, ask if she'd like a cup of tea, she let me know how she'd heard my snoring as she painted.

It's true I had dropped off for a few seconds or, as I prefer to think of it, had so far sunk into a creative reverie that my unconscious had briefly taken over, plunged deeper into the world my imagination had opened. Well, it does happen sometimes, but I must admit that yesterday I'd plain fallen asleep, having bored myself into blank submission.

Her painting, you see, was to blame. How could I tease a tale of hope from workhouse iniquity (my latest vague idea for a novel) with the smell of fresh paint drifting through and the noise of brush on wall? I was distracted by guilt. Couldn't think for it. Eventually my consciousness closed down on my conscience, salved on waking by my offer of tea.

My wife puts me to shame. The thing is, her industry is so damn visible. Not to mention practical and useful; vital, even. Mine is none of these, unless you count stacking the dishwasher. The only time I achieve visibility is on the publication of a book or (mere squib) an article. Such products are so rare as to make some of my acquaintance doubt if I'm really doing anything that could be counted as work at all.

Every Sunday I go to watch a junior football team my son manages, and every week the same parent sidles along the touchline to ask, 'So, what are you working on at the moment, David?' 'Oh, still the Stephenson book,' has been my stock answer for the last two years. This man runs a plumbing business. He probably fits or fixes twenty bathrooms a month. It has never crossed my mind to ask, 'So, what are you working on at the moment, Michael?' Perhaps he's waiting for the day.

Some people seem able to think while doing other things - visible things. Gladstone apparently liked to chop down trees as he pondered great matters of state, though whether he profited from the sale of logs afterwards history does not reveal. I really wish I could do that. I'd sweep leaves off the garden, pausing briefly every now and then to wave at my wife through the kitchen window. I'd sand furniture, even decorate the house while mentally composing chapters for my book... but I know from trying (honest, I have) that my brain fastens onto the tedium of the task, the brush-brush-brush repeating-repeating on the inside of my skull. I can't even go for a walk without fixating on footsteps. Thank Apple for iPod, though I can't think to music either except about the music.

Over the years I have tried a variety of techniques for kick-starting creativity – automatic writing, prop pile, keyword dip, collaborative writing, role play... so many that I used to package and sell them to corporate trainers at inflated prices, thereby paying the bills while I continued my search for one that worked for me – and I have discovered there is only one authentic Williams method. I lie flat in a perfectly quiet, preferably darkened room, close my eyes, and think.

Even to a trained observer (let's say David Attenborough, or my wife) this activity is indistinguishable from sleep. I could be a sloth. Ironically, the better it's working the more like sleep it seems. In deep thinking mode I'm oblivious to someone walking into the room, to a gentle enquiry, a tut. Like a finely-tuned sports professsional (hah) I'm in the zone.

And in good company too. Vincent Van Gogh said of his creative technique, 'I dream my painting and then I paint my dream.' Judging by his output (over 2,000 works) he must have put in a lot of dreaming. I wonder who did his decorating. Come to think of it my wife used to paint pictures, years ago, before the housework took over... Hmm, I'm beginning to feel guilty again. Perhaps it's time I went downstairs. Put the kettle on.

Published on March 29, 2012 07:43

March 22, 2012

The Stephenson Women

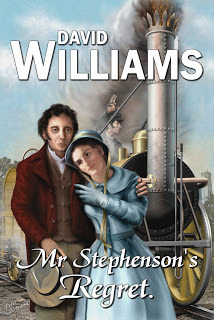

I am currently engaged in a busy series of of talks and readings from my novel Mr Stephenson's Regret about the railway pioneers. Next week is the first of a number of talks I'm doing specifically for women's groups who have shown an interest in hearing about the Stephenson women. George married three times in his lifetime and had two sisters, and son Robert also married, yet the women in these lives have been all but ignored in the histories and biographies. There is not even a single portrait of any of them - the painting I've reproduced above is a confused and idealised one of George and his family, purporting to show not only his mother Mabel standing with some vessel improbably balanced on her head but, even more improbably, two of his wives Fanny and Betty (seated) in the scene. I can assure you that George was not a bigamist. This painting was commissioned from the artist John Lucas in 1857, long after all but one of the people in the painting (Robert) had died. I can't speak for the dog.

One of the pleasurable things about being a novelist is that you can let your imagination fill in the gaps between the known facts. I've done this in Mr Stephenson's Regret and have tried to give more substance to the Stephenson women than the histories do - indeed one of my main reasons for creating this biographical fiction was to explore the relationships more fully than had been attempted before. In this blog posting, however, I have tried to assemble for readers some of the more interesting facts that I gleaned about the women during my research. This was the raw material I drew on for the characters portrayed in the novel.

George's mother and sisters

George's mother Mabel (1749-1818) was the daughter of George Carr, a bleacher and dyer from Ovingham, Northumberland, and a farmer's daughter Eleanor Wilson, who had married beneath her social status. Despite her 'superior' roots Mabel was, like her husband, illiterate - they both signed the marriage register with an X.

The one brief description we have of Mabel is an intriguing one from an old Wylam miner who described her as "a delicate body and very flighty". He goes on to say of the Stephensons: "They were an honest family, but sair hadden doon in the world." In other words they were impoverished. Mabel, her husband Bob, and eventually six children somehow lived in one tiny room of a labourer's cottage in Wylam, with unplastered wall, bare rafters and a clay floor. (The cottage is still there - see my earlier posting Back to George's roots.) Later, Mabel had to deal with the total blindness of Old Bob as a result of an accident with steam in the colliery where he worked. They came to rely on George, a poor man himself at that time, for everything. Mabel died not long after George's fortunes improved, and well before he achieved his national reputation.

Unusually for the time, all of Mabel's six children survived and grew up healthy. Two were girls - Eleanor (1784-1847) known as Nelly, and Ann (1792-1860).

While still a young girl, Nelly went to London to work in domestic service, but came back because she received a letter from a sweetheart back in Tyneside offering marriage. It was a difficult return by boat up the North Sea coast, and when Nelly arrived home she found that her intended had married someone else. Nelly was left with no job, no savings and no lover. She turned to the church for comfort. It seemed Nelly would continue a spinster, especially after she took on the upbringing of her brother George's son, Robert. She lived with the widowed father and her nephew in their cottage (one room and a garret then) in West Moor near Killingworth; but in time there was a new romance for Nelly. Through the church, she met and (at the age of 40) married Stephen Liddle.

Despite Nelly's age on marriage, the couple went on to have three children, Stephenson Liddle (1825-1843), Eleanor Liddle (1826-1826) and Margaret Liddle (1825-1852). Nelly's husband Stephen worked for George at the Forth Street Works where The Rocket was made, and was unfortunately fatally injured there in an accident. (George's brother John also died in an accident at the works.) George subsequently paid for Nelly's keep until her own death a year before his, and after her death made provision for her surviving daughter Margaret, who went to live with a housekeeper, Mrs Willis.

Nelly's younger sister Ann was much quicker to the altar. She was only 22 when she married local man John Nixon in 1814 and, like many working class couples at the time, they emigrated to America, specifically Pittsburgh which was industrialising rapidly. The couple had six children: Jane (1815-1884), Robert (1818-1900), Mary (1821-1892), Joseph (1824-1892), Ann (1826-??), and Ellen (1831-1900). After her husband's death, Ann remarried and was subsequently known as Mrs Anna York. She died, still in Pittsburgh, in 1860, long after the rest of her brothers and sisters.

Robert's mother and sister

George met Frances (Fanny) Henderson (1768-1806) at the farm house where he lodged when he was a young engine mechanic. Fanny had been a servant at the farm for ten years, described by the owner as "of sober disposition, an honest servant and of good family." She was not George's first sweetheart (see my notes below) and indeed was not even the first to attract him in this house, for he had earlier paid court to Fanny's sister Ann who refused him. Fanny was perhaps a surprising choice for George, being nine years older than him and generally thought of as an old maid since her first fiancee, a school-master from Black Callerton, had died suddenly at the age of 26. Nevertheless George proposed and they were married at Newburn Church on 28 November 1802 when Fanny was 33. She made only her mark in the marriage register, and her name is in her new husband's unsteady hand, George having just a couple of years earlier taught himself to read and write.

Robert was born a year later, and a year after that the three of them moved to the cottage near Killingworth that housed the Stephenson family until George was on the verge of his greatest fame as pioneer of the public railway. Fanny though, knew nothing but the early years of poverty. She was ill for several months after Robert's birth, and worse when she delivered a baby sister for Robert when he was two years old. Baby Fanny lived just three weeks, and her mother followed her into the grave a few months later, a victim of what was then called consumption and which we now know as pulmonary tuberculosis, one of the principal diseases associated with poverty. Mother and baby are buried in an unmarked grave somewhere in the grounds of Longbenton Church.

George's second wife

According to George Stephenson's first biographer Samuel Smiles, his first sweetheart and the one to whom he first proposed was neither of the Henderson girls but a prosperous farmer's daughter from Black Callerton, Elizabeth (Betty) Hindmarsh (1777-1845). Smiles' story is that he was refused, not by Betty but by her father Thomas Hindmarsh, who would not allow his daughter to marry a penniless pitman. This romantic account was corrected by the author himself when he was later assured that George did not meet Betty until he was locally successful, but for the purposes of my novel I have accepted the original Smiles version as true, not because it makes a better story (though it does) but because there is no objective evidence to support the second assertion, and chiefly because it makes logical sense that George should have met Betty when he lived and worked near Black Callerton, not when he was several miles away in Killingworth where Betty had no reason to be anywhere near him territorially, socially or professionally.

In their young days the couple would meet under the trees in the orchard next to the farmhouse. Being a girl, Betty was cultivated rather than educated, could play the piano and liked reading - quite different accomplishments to George's, but she sincerely loved him, and was so devastated by her father's refusal of George's hand that she declared she would never marry anyone else, and didn't, though it was thirteen years after Fanny's death that George plucked up the courage to ask her again, and was accepted. This time there were no objections from her father to Betty marrying the well-to-do engineer.

They married in Newburn Parish Church, the place of George's first marriage to Fanny, but Betty needed no help with her signature in the marriage register, while George's was a much more confident flourish than his earlier effort. By this time George was 39 and his bride even older, 43.

From the scant evidence available, Betty seems to have been a great calming influence on George, who had a reputation for irascibility. She is described in George Parker Bidder's correspondence as 'homely, good and kind'. She was a lover of animals; we know for example that late in life she kept two African grey parrots in their Chesterfield home and made a less than successful attempt at bee-keeping. She was a great influence on Robert too. Almost certainly it was she who encouraged him to take up the flute and become a member of the church band (Mrs Stephenson was a dedicated Methodist) and tellingly it was his stepmother who was the recipient of Robert's most affectionate and personal letters.

Betty died at Tapton House on 3 August 1845 after an untroubled if childless twenty-five year marriage. She is buried in the family vault alongside George in Chesterfield's Holy Trinity Church. George, though, did not join her there until three years later, by which time he was married again, to his housekeeper.

George's third wife

Ellen Gregory (1808-1865) was twenty-seven years younger than George and almost five years younger than his son. Her father was Richard Gregory, a farmer from Bakewell in Derbyshire; her mother Ellen (or Elin, nee Stanley). She had one younger brother, Richard. A spinster until her marriage to George, she seems to have been housekeeper at Tapton for a number of years, certainly before Betty's death. She married George on 11 January 1848, just six months before his death, at St John's Church in Shrewsbury. (Incidentally, George gave both his and his father's rank and profession as 'gentleman' on the marriage certificate.)

Stephenson's biographers have even less to say about Ellen than his other two wives (in Smiles' book she is relegated to a single footnote), almost as if they regard her presence as a smirch on his life, and best forgotten. Robert, too, was highly displeased by his father's remarriage, and obviously regarded the woman as a gold-digger. He may not have been wrong; despite having been left £1000 as a lump sum and £800 a year as long as she didn't remarry, plus furniture and sundries, the last Mrs Stephenson applied to executor Robert for a better settlement. This was a woman whom a year before had been earning £40 per annum as housekeeper. It says everything about the coldness of their relationship that Robert referred her to his solicitor.

After George's death Ellen stayed for a time at Tapton House before moving to Shrewsbury to live with her sister and brother-in-law who was minister of the Swan Hill Independent Church there. She did not remarry (perhaps not wishing to lose her annuity) and died at Beauchamp near Shrewsbury in 1865.

Robert's wife

The difference between George's social standing as a young man in his twenties and Robert's around the same age is revealed by the contrasting backgrounds of the women they courted and brought to the altar. Both brides were called Fanny, but there the resemblance ends. Frances (Fanny) Sanderson (1803-1842) was the daughter of a City of London merchant John Sanderson, who met Robert through incidental business with the emerging railway company. This was shortly before Robert went off for three years to Colombia, but he kept in touch with Fanny and she with him, we assume - Robert's correspondence was lost in a shipwreck he suffered on his way back to England. A couple of years after his return they were married at Bishopgate Parish Church. There wasn't much time for a honeymoon, the Rainhill Trials only a few months away - they stayed just a few days in Wales en route to Liverpool where Robert had railway business. Like George's Betty, Robert's Fanny played second fiddle to work in the life of her man.

The only physical description we have of Fanny is that she was "not beautiful, but she had an elegant figure, a delicate and animated countenance, and a pair of singularly expressive dark eyes." These were the only clues that artist Peter Fussey had to go on as he imagined the newly married Fanny with her husband at the Rainhill Trials in 1829 for the front cover of Mr Stephenson's Regret.

Fanny seems to have been like Betty in many ways. Both liked music (when Robert and Fanny set up house in Greenfield Place in Newcastle Fanny insisted on having her piano brought up from London), poetry and the arts. Fanny was by repute an accomplished portrait painter, but none of her work seems to have survived. She was, like Betty, an animal lover, with a Newfoundland dog to keep her company during Robert's absences. Most significantly like her mother-in-law Fanny's influence on her husband seems to have been quiet but profound. There is evidence of her adding personal touches to at least one of his letters and we are told by one of Robert's early biographers she was "an unusually clever woman, and possessed of great tact in influencing others, without letting anyone see her power."

Perhaps though there was a slight hint of social pretension (typical of the Victorian age) about Fanny. When she got wind of a possible connection between Old Bob Stephenson's father and the Stephensons (or Stevensons) of Mont Grenan in Ayrshire who boasted a coat of arms, she persuaded her husband to apply to the College of Heralds for use of the devices. Purchasing them cost Robert a substantial fee, and he was never comfortable with the idea - in one conversation with a friend not long before his death he pointed out the crest on the family crockery and remarked, "Ah, I wish I hadn't adopted that foolish coat of arms! Considering what a little matter it is, you could scarcely believe how often I have been annoyed by that silly picture."

Fanny was also like Betty in being childless (a great source of sorrow for the Stephensons) and in dying after a painful illness. In Fanny's case she suffered a form of cancer for two years before her early death. Knowing she was going to die, she urged Robert to remarry for the sake of having children, but he never did, though he survived her by seventeen years. Fanny was buried in Hampstead churchyard where she was visited regularly by her grieving husband.

For the sake of completeness on the story of the Stephenson women I should mention (though I make no use of this in my novel) a rumour that Robert Stephenson had a long-term affair with Henrietta, the wife of his friend Baden-Powell, and fathered a child with her in 1857. Though there is no evidence beyond hearsay for this, it is true that he became godfather to the child who was christened Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell. This infant would grow up to become the hero of Mafeking and founder of the Boy Scout movement.

Published on March 22, 2012 14:23

March 12, 2012

The richness of dialect - some Northumbrian Geordie examples

Though strong dialect is often thought of as a sign of ignorance in users, dialect words have enriched the language, not just in sound and natural rhythm, but in semantics too. Certain dialect terms have produced nuances of meaning that are not conveyed in standard English. The examples I've used below are all from my native Northumbrian Geordie dialect, but I know that many other British and non-British dialects can provide similar examples, and would welcome offerings.

bullet is the Geordie word for a sweet, but specifically refers to a boiled sweet, especially of the round sort like the old-fashioned bulls-eyes or gob-stoppers. Bullet gives us the shape and hardness of the round shot that would have been used for bullets in the days the word was coined.

claggy as in 'Your hands are all claggy'. More than just 'sticky', claggy emphasises the idea that strands of the stuff would cling to the toucher's hands too, like sticky toffee does. Similarly the Geordie word clarts ('I fell in the clarts on the way here') is so much sloppier than mud.

gadgie is an old man. Somehow it expresses in one word the broken-down, dishevelled condition of the man, and hints at a certain cussedness or shortness of temper.

getten as In 'This toaster I've getten is much better than the old one.' The word conveys the sense of 'I've got and am here in possession of.'

hoppings A fairground, as in the annual fair held at Newcastle's Town Moor. The word combines movement and energy with a slight grubbiness underneath - are we hopping with excitement or fleas, or both?

marra is such a wonderfully economical word - just five letters to mean a friend you work with - and such an affectionate one. 'Alright, marra?'

spuggie is a sparrow, but we also get a sense that this is an urban, deprived, bedraggled sparrow, buffetted by the winds, but with a gleam in its eye for the next catch.

whisht as in the evocative opening lines of the song The Lambton Worm:

'Whisht, lads, haad your gobs, I'll tell ye aall an awful story.

Whisht, lads, haad your gobs, I'll tell ye boot the Worm.'

Whisht - alliterative, onomatopoeic, dramatic - shut your mouths, draw near and listen.

Those are my few examples. Howay hinnys, let us hear yours.

bullet is the Geordie word for a sweet, but specifically refers to a boiled sweet, especially of the round sort like the old-fashioned bulls-eyes or gob-stoppers. Bullet gives us the shape and hardness of the round shot that would have been used for bullets in the days the word was coined.

claggy as in 'Your hands are all claggy'. More than just 'sticky', claggy emphasises the idea that strands of the stuff would cling to the toucher's hands too, like sticky toffee does. Similarly the Geordie word clarts ('I fell in the clarts on the way here') is so much sloppier than mud.

gadgie is an old man. Somehow it expresses in one word the broken-down, dishevelled condition of the man, and hints at a certain cussedness or shortness of temper.

getten as In 'This toaster I've getten is much better than the old one.' The word conveys the sense of 'I've got and am here in possession of.'

hoppings A fairground, as in the annual fair held at Newcastle's Town Moor. The word combines movement and energy with a slight grubbiness underneath - are we hopping with excitement or fleas, or both?

marra is such a wonderfully economical word - just five letters to mean a friend you work with - and such an affectionate one. 'Alright, marra?'

spuggie is a sparrow, but we also get a sense that this is an urban, deprived, bedraggled sparrow, buffetted by the winds, but with a gleam in its eye for the next catch.

whisht as in the evocative opening lines of the song The Lambton Worm:

'Whisht, lads, haad your gobs, I'll tell ye aall an awful story.

Whisht, lads, haad your gobs, I'll tell ye boot the Worm.'

Whisht - alliterative, onomatopoeic, dramatic - shut your mouths, draw near and listen.

Those are my few examples. Howay hinnys, let us hear yours.

Published on March 12, 2012 16:26

March 5, 2012

Editing a sketch - an example

In my last post I wrote about lessons I'd learned about sketch writing from my work as one of a team of writers on the BBC Radio sketch show Jesting About 2. I thought it might be interesting to show an example of one of my sketches in its first draft form, then revised after a read-through with the group and discussion with the producer. Click the Show/hide button to reveal the first draft.

SO YOU WANT A PAYRISE? (FIRST DRAFT) David Williams F/X: INT. DOOR OPENS JENKINS: Er, you wanted to see me, boss. BATTS: Ah, Jenkins, yes, come in. You know Miss Proops from Personnel. JENKINS: Hello. BATTS: Don't stand on ceremony, Jenkins. Perch nervously on the edge of this chair. I understand from Miss Proops that you've requested a pay rise. JENKINS: Yes, sir. Well I've been here nearly three years now and I've never had… BATTS: Now as you may know I'm a chap who likes to deal in facts, Jenkins. How many days are there in a year? JENKINS: Mmm, 365. (BRIGHTLY) 366 in a Leap Year. BATTS: Quite. And how many hours in a day? JENKINS: 24. BATTS: Of which you work…? JENKINS: Well, nine to five. Eight hours, boss. BATTS: Which is precisely one third of a day, Jenkins. So over the year… You do the sums, Miss Proops, what's one third of 366 days? PROOPS: That would be 122 days, Mr Batts. BATTS: Very good, Miss Proops. Very, very good. Now, Jenkins, do you work weekends? JENKINS: Er, no, sir. I'm staff side, you see. We don't… BATTS: So, no Saturdays, no Sundays. Let's see, 52 weeks in the year. By my reckoning that's 104 days to take off your... PROOPS: 122. BATTS: Which leaves…. PROOPS: 18. BATTS: Very good. Now Miss Proops, what annual holiday entitlement do we favour our Mr Jenkins with at the moment? PROOPS: 14 days a year. JENKINS: That's another thing I was going to ask … BATTS: Don't distract while I'm trying to subtract, Jenkins. So, 18 minus 14 leaves …. PROOPS: Four. BATTS: (WITHERING) Yes, Proops. I think your calculator was surplus to requirements in that instance. PROOPS: (COWED) Sorry, Mr Batts. BATTS: Four days. But of course this office is closed Christmas Day... PROOPS: (RESURGENT) And New Years Day! BATTS: Which leaves two days. Do you work Good Friday, Mr Jenkins? JENKINS: Er, no, sir. BATTS: Easter Monday? JENKINS: (DEFEATED) No. BATTS: Well, Jenkins. I have to say your pay claim doesn't stand up to scrutiny. In the circumstances I think we've been more than generous. According to my calculations you haven't worked for us one single day. JENKINS: Can I go now, Mr Batts? To tell you the truth I'm feeling a bit sick. BATTS: Well we can't have you working if you're ill, Jenkins. I insist you take the rest of the afternoon off. JENKINS: Thank you, boss. You're very kind. BATTS: Not at all. It's only three hours. Miss Proops, be sure to dock it from his salary at the end of the month. END

Show/hide

The discussion after the read through raised a couple of main issues:

1. The boss (called BATTS in the first version) was too old-school. Ben, the producer, invited me to rethink him as a modern management type, just as ruthless underneath as the first, but with a veneer of apparent informality and concern for his employees. I called him simply BOSS in the revised version.

2. Miss Proops was something of a secretarial stereotype. Ben questioned whether she was really needed. Why use three characters in a sketch if two can do the job equally well? So I dropped Miss Proops in the revised version. JENKINS became simply FRANK.

Try the second version by clicking the next Show/hide button. Is there an improvement, do you think?

SO YOU WANT A PAYRISE? (REVISED) David Williams FX OFFICE ATMOS FRANK You busy, boss? BOSS Frank, come in, you know my door's always open. Don't stand on ceremony – perch nervously on the edge of the chair. This is about your pay-rise request, yes? FRANK Well, I've been here nearly three years now, and I've never had... BOSS Three years. Time flies, eh? How many days in a year, Frank? FRANK Eh? Oh, er... 365. (EAGER BEAVER) 366 in a leap year. BOSS Good. Very, very good. That's what I like about you, Frank, you're quick. And how many hours in a day? FRANK (ENCOURAGED BY PRAISE) That's easy. 24. BOSS Of which you work? FRANK Oh, er, nine to five. (BRIGHTLY) That's eight hours, boss. BOSS Which is precisely one third of a day. So, over the year. Come on, Rain Man, what's one third of 366 days? FRANK Mmm, that would be 122 days, boss. BOSS I said you were quick. Remind me, Frank, do you work weekends at all? FRANK No, no. I'm staff side. We don't... BOSS So, no Saturdays, no Sundays. Let's see. 52 weeks in the year... By my reckoning that's 104 days, which we take off your...? FRANK 122. BOSS Which leaves...? FRANK (BEMUSED) Oh, er, 18. BOSS Very good. Now, Frank, holidays! FRANK (INTERESTED) Yes, that's another thing I was going to ask about... BOSS Of course, Frank, no subject barred. So what's your entitlement at the moment? FRANK Just 14 days, boss. I think you'll agree... BOSS Don't interrupt while I'm doing the sums. 18 minus 14, that's... FRANK (HELPFUL) Four. BOSS Just got there before you, Frank. Wow, you young guys keep me on my mettle. That's what I love about this business. Now, where had we got to? FRANK Er... four? BOSS Oh, yes, four days. But of course the office is closed Christmas Day. FRANK And New Year's Day. BOSS Which leaves two days. Do you work Good Friday, Frank? FRANK (BELATEDLY REALISING WHERE THIS IS GOING) Ermmm, no. (BEAT) No. BOSS Easter Monday? FRANK (DEFEATED) No, boss. BOSS Well, Frank. You know me, always ready to be persuaded by the facts. And in this case I have to say your pay claim doesn't stand up to scrutiny. In the circumstances I think we've been more than generous. According to the figures you and I have just kicked around you haven't worked for this firm one single day. (BEAT) Are you OK, Frank? You've suddenly turned a little pale. FRANK I do feel a bit sick all of a sudden. BOSS (SYMPATHETIC) Ah Frank, mate, we can't have you working if you're not well. Please, with my blessing, take the rest of the day off. FRANK (WEAKLY) Thank you, boss. That's very kind of you. BOSS Not at all – you know my mantra; this company's greatest asset is its workforce, and it has to be looked after. What time is it now? 2 o' clock. You get along home to bed, I'll let Accounts know they'll need to dock three hours off your salary this month. END Show/hide

A few more cuts and changes were made to the sketch at the time of the recording, but as they were done 'on the hoof' I don't have those amends in script form. The show will be broadcast on Good Friday and again on Easter Monday. I'll add the Listen Again link here when it's available so you can see how this and the other sketches sounded on the air.

SO YOU WANT A PAYRISE? (FIRST DRAFT) David Williams F/X: INT. DOOR OPENS JENKINS: Er, you wanted to see me, boss. BATTS: Ah, Jenkins, yes, come in. You know Miss Proops from Personnel. JENKINS: Hello. BATTS: Don't stand on ceremony, Jenkins. Perch nervously on the edge of this chair. I understand from Miss Proops that you've requested a pay rise. JENKINS: Yes, sir. Well I've been here nearly three years now and I've never had… BATTS: Now as you may know I'm a chap who likes to deal in facts, Jenkins. How many days are there in a year? JENKINS: Mmm, 365. (BRIGHTLY) 366 in a Leap Year. BATTS: Quite. And how many hours in a day? JENKINS: 24. BATTS: Of which you work…? JENKINS: Well, nine to five. Eight hours, boss. BATTS: Which is precisely one third of a day, Jenkins. So over the year… You do the sums, Miss Proops, what's one third of 366 days? PROOPS: That would be 122 days, Mr Batts. BATTS: Very good, Miss Proops. Very, very good. Now, Jenkins, do you work weekends? JENKINS: Er, no, sir. I'm staff side, you see. We don't… BATTS: So, no Saturdays, no Sundays. Let's see, 52 weeks in the year. By my reckoning that's 104 days to take off your... PROOPS: 122. BATTS: Which leaves…. PROOPS: 18. BATTS: Very good. Now Miss Proops, what annual holiday entitlement do we favour our Mr Jenkins with at the moment? PROOPS: 14 days a year. JENKINS: That's another thing I was going to ask … BATTS: Don't distract while I'm trying to subtract, Jenkins. So, 18 minus 14 leaves …. PROOPS: Four. BATTS: (WITHERING) Yes, Proops. I think your calculator was surplus to requirements in that instance. PROOPS: (COWED) Sorry, Mr Batts. BATTS: Four days. But of course this office is closed Christmas Day... PROOPS: (RESURGENT) And New Years Day! BATTS: Which leaves two days. Do you work Good Friday, Mr Jenkins? JENKINS: Er, no, sir. BATTS: Easter Monday? JENKINS: (DEFEATED) No. BATTS: Well, Jenkins. I have to say your pay claim doesn't stand up to scrutiny. In the circumstances I think we've been more than generous. According to my calculations you haven't worked for us one single day. JENKINS: Can I go now, Mr Batts? To tell you the truth I'm feeling a bit sick. BATTS: Well we can't have you working if you're ill, Jenkins. I insist you take the rest of the afternoon off. JENKINS: Thank you, boss. You're very kind. BATTS: Not at all. It's only three hours. Miss Proops, be sure to dock it from his salary at the end of the month. END

Show/hide

The discussion after the read through raised a couple of main issues:

1. The boss (called BATTS in the first version) was too old-school. Ben, the producer, invited me to rethink him as a modern management type, just as ruthless underneath as the first, but with a veneer of apparent informality and concern for his employees. I called him simply BOSS in the revised version.

2. Miss Proops was something of a secretarial stereotype. Ben questioned whether she was really needed. Why use three characters in a sketch if two can do the job equally well? So I dropped Miss Proops in the revised version. JENKINS became simply FRANK.

Try the second version by clicking the next Show/hide button. Is there an improvement, do you think?

SO YOU WANT A PAYRISE? (REVISED) David Williams FX OFFICE ATMOS FRANK You busy, boss? BOSS Frank, come in, you know my door's always open. Don't stand on ceremony – perch nervously on the edge of the chair. This is about your pay-rise request, yes? FRANK Well, I've been here nearly three years now, and I've never had... BOSS Three years. Time flies, eh? How many days in a year, Frank? FRANK Eh? Oh, er... 365. (EAGER BEAVER) 366 in a leap year. BOSS Good. Very, very good. That's what I like about you, Frank, you're quick. And how many hours in a day? FRANK (ENCOURAGED BY PRAISE) That's easy. 24. BOSS Of which you work? FRANK Oh, er, nine to five. (BRIGHTLY) That's eight hours, boss. BOSS Which is precisely one third of a day. So, over the year. Come on, Rain Man, what's one third of 366 days? FRANK Mmm, that would be 122 days, boss. BOSS I said you were quick. Remind me, Frank, do you work weekends at all? FRANK No, no. I'm staff side. We don't... BOSS So, no Saturdays, no Sundays. Let's see. 52 weeks in the year... By my reckoning that's 104 days, which we take off your...? FRANK 122. BOSS Which leaves...? FRANK (BEMUSED) Oh, er, 18. BOSS Very good. Now, Frank, holidays! FRANK (INTERESTED) Yes, that's another thing I was going to ask about... BOSS Of course, Frank, no subject barred. So what's your entitlement at the moment? FRANK Just 14 days, boss. I think you'll agree... BOSS Don't interrupt while I'm doing the sums. 18 minus 14, that's... FRANK (HELPFUL) Four. BOSS Just got there before you, Frank. Wow, you young guys keep me on my mettle. That's what I love about this business. Now, where had we got to? FRANK Er... four? BOSS Oh, yes, four days. But of course the office is closed Christmas Day. FRANK And New Year's Day. BOSS Which leaves two days. Do you work Good Friday, Frank? FRANK (BELATEDLY REALISING WHERE THIS IS GOING) Ermmm, no. (BEAT) No. BOSS Easter Monday? FRANK (DEFEATED) No, boss. BOSS Well, Frank. You know me, always ready to be persuaded by the facts. And in this case I have to say your pay claim doesn't stand up to scrutiny. In the circumstances I think we've been more than generous. According to the figures you and I have just kicked around you haven't worked for this firm one single day. (BEAT) Are you OK, Frank? You've suddenly turned a little pale. FRANK I do feel a bit sick all of a sudden. BOSS (SYMPATHETIC) Ah Frank, mate, we can't have you working if you're not well. Please, with my blessing, take the rest of the day off. FRANK (WEAKLY) Thank you, boss. That's very kind of you. BOSS Not at all – you know my mantra; this company's greatest asset is its workforce, and it has to be looked after. What time is it now? 2 o' clock. You get along home to bed, I'll let Accounts know they'll need to dock three hours off your salary this month. END Show/hide

A few more cuts and changes were made to the sketch at the time of the recording, but as they were done 'on the hoof' I don't have those amends in script form. The show will be broadcast on Good Friday and again on Easter Monday. I'll add the Listen Again link here when it's available so you can see how this and the other sketches sounded on the air.

Published on March 05, 2012 14:35

February 24, 2012

Writing radio sketches: ten things I've learned

For the past month or so I've temporarily turned away from the business of writing novels (as opposed to promoting them) and returned to a new aspect of my former craft of writing for the radio. The new bit is comedy rather than drama, and specifically comedy sketches.

I've been involved with a group of other writers, stand-up comedians, performers and producers in putting together a one-off comedy sketch show for BBC North called 'Jesting About 2'. The first manifestation of 'Jesting About', which was broadcast last year, has been nominated for a Sony Radio Award, so we had to be on our toes for this one. I have to say that I was the grand-dad of the group, but the others were very tolerant towards me and hardly ever suggested I might like to go for a lie-down.

The writing and rehearsals culminated in a recording of the show last weekend in front of a packed audience at Live Theatre in Newcastle upon Tyne. The resulting programme, scrupulously edited no doubt by producer Ben Walker, will be broadcast courtesy of BBC Radio Tees and BBC Radio Newcastle on Good Friday and Easter Monday.

This was a lively and refreshing learning experience for me (as all writing projects are) and I want to share with you ten things I learned through it about writing comedy sketches for the radio.

1. Cut to the chase. In sketch comedy there is no time for establishing character or scene except for perhaps the briefest sound effect or 'atmos' suggestion. Characters have to establish themselves virtually instantly through words and tone, and the situation reveals itself simultaneously with the unfolding story of the sketch.

2. Don't stretch the sketch. There has to be a real economy about any sketch. Every word needs to be worth its weight. Short is a real virtue, and if you can make it even shorter it often works better.

3. Sketches obey Einstein's theory of relativity. A sketch short of jokes feels long even when it's short.

4. One laugh buys a few chuckles. A sketch doesn't have to be full of belly laughs but, just as kids need sweets, your audience has to be kept happy with at least one laugh-out-loud line per sketch (preferably two or three).

5. It matters where your best jokes are. A producer from a visiting BBC Newsjack team showed me how shifting the order of my sketch allowed me to keep my best joke for the punchline. So many sketches fail right at the death with a weak, unimaginative or lazy punchline; the quality of what's gone before will not save a sketch without a firm punchline.

6. Absurdity is prized in sketch comedy. I consider myself imaginative, but I quickly learned I had to reach further out of the box at times to please comedy producers and script editors. The younger writers were generally more comfortable with sheer absurdity than me, even if I was brought up on Monty Python. But there has to be a discipline even to the surreal - each sketch must have its own internal logic, and its own unity, otherwise it's just a mess. (My view is, absurdity piled upon absurdity can degenerate into a daft 'listing' game.)

7. A sketch can read well and play badly. Mostly, a sketch that seems to lift off the page in reading does well in peformance; occasionally a sketch that seems good on paper simply doesn't fly from a performer's mouth, and that's not always the performer's fault - sometimes a sketch may enter the mind more smoothly than it does the ear.

8. A sketch can read badly and play well. Nothing can save a rank bad sketch, but there have been several occasions in 'Jesting About 2' when a script that none of us has been quite sure about on paper seems to take on a new life when performed - sometimes a particular sketch and a certain kind of actor seem to be made for each other. The joint lesson of 7 and 8 is that sketches always need a good work-out both on paper and in performance.

9. A sketch can always be improved, and destroyed. Many of our scripts went through quite radical changes during what I would call the testing process - reading and rehearsal. In my case, a few that I initially thought unimprovable were greatly improved. Occasionally, with mine and others, the original spark was lost somewhere in the redrafting. And some just died on the operating table.

10. A sketch is never safe until it's aired. What a ruthless process a sketch show can be when the eleventh and twelfth hours are upon us. The final rehearsals of 'Jesting About 2', and the period immediately before recording, even as the auditorium was filling, were punctuated by the sounds of pens scoring through lines, sheets being ripped out, whole sketches dropped, not always for qualitative reasons. During the performance, the same sounds reverberated in our heads whenever a sketch didn't quite work its magic on the audience - another one to be cut in the edit. And all this before Ben Walker finds he still has forty-five minutes of good material for a thirty-minute show. Rip, snip and clip. The only saving grace to all this artistic pain and heartache will be if the final programme sings as we hope it will - and makes you laugh.

Published on February 24, 2012 14:10