Gordon G. Chang's Blog

July 27, 2017

North Korea Economy Shows Surprising Strength

On Saturday, the Bank of Korea, the South Korean central bank, reported that last year North Korea’s gross domestic product grew 3.9 percent. That is the highest growth rate since 1999.

The 3.9 percent figure was, for most observers, unexpected. In the previous half decade, the North managed only an average of about one percent growth. It appears, therefore, that last year the regime managed to break out of a long period of stagnation.

The surprisingly strong result will lead some to suspect the Bank of Korea’s figure. Observers, however, have relied on the bank’s estimates since the early 1990s because Pyongyang stopped reporting data in the 1960s after the regime began to fail to meet its publicly announced development goals. The bank’s estimates have their obvious limitations because of the opaqueness of the North Korean system, but they show trends.

Before the Bank of Korea’s announcement Saturday, observers were already arguing about how well the North’s economy was performing. That debate will continue, but it does appear that some level of economic stability and development has been achieved by Pyongyang. And, that will enable Kim Jong Un, the North’s dictator, to claim that he has made good on his byungjin promise to simultaneously develop the civilian economy and a fearsome arsenal.

The regime seems eager to make the point that new construction projects illustrate improving economic conditions. In April, a government tour for foreign journalists through the Ryomyong Street Project, a residential development in Pyongyang, was billed by officials as a “big and important” event.

The military also has benefitted nicely in these times of improved economic conditions, as demonstrated by the accelerated pace of weapons development this year—11 tests of 17 missiles so far. Although, the country remains poor by global standards, the North seems to have enough cash to build ballistic missiles and nukes.

And that brings us back to the economy. To engineer the uptick, Kim has had outside help. As Dong Yong-Sueng of the Samsung Economic Research Institute has said “Without foreign exchange, the economy would stop functioning.”

The North Korean economy is still functioning—and parts of it look like they are doing well—so we should ask where the cash is coming from. This is not rocket science. The answer is the People’s Republic of China. Through state institutions and private channels, China looks like it provides substantially more than half of the regime’s foreign currency.

Last year, the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency, a South Korean government-funded organization, reported that China accounted for more than 92 percent of the North’s trade. The North’s two-way trade last year was up 4.7 percent.

Much of North Korea’s “imports” are, in reality, Chinese aid, particularly crude oil. China sells some oil to the North, but most of it is thought to be provided on concessionary terms.

And all this means that sanctions on North Korea are not nearly strict enough or that those sanctions are not being enforced, most likely both.

The Bank of Korea’s surprisingly strong estimate of the North’s 2016 GDP more than anything highlights the failure of the US and the international community to deny Kim Jong Un the resources to continue his horrific regime and build weapons of mass destruction.

The House of Representatives has adopted new sanctions, and the matter is now before the Senate. Senate passage is likely.

That’s a good move, and North Korea’s robust growth’s last year is a sure sign that time is of the essence. Pyongyang and Beijing have outfoxed the international community for too long.

OG Image: Asia PacificNorth AmericaKoreaNorth Korea

Asia PacificNorth AmericaKoreaNorth Korea

July 17, 2017

Trump Puts Squeeze on Beijing over North Korea

“Recently, certain people, talking about the Korean peninsula nuclear issue, have been exaggerating and giving prominence to the so-called ‘China responsibility theory,’” said Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang on Tuesday, referring indirectly to Trump administration officials. “I think this either shows lack of a full, correct knowledge of the issue, or there are ulterior motives for it, trying to shift responsibility.”

Beijing expressed more than just irritation with Washington. “Asking others to do work, but doing nothing themselves is not OK,” Geng said. “Being stabbed in the back is really not OK.”

Language this intemperate is rarely heard from government officials in public, especially diplomats, and it tells us that US-China relations are about to spiral downward.

And, frankly, that would be a good thing. For a generation, American diplomats have equated good relations with cordial relations. Yet, in China’s view good relations exist only when Beijing gets what it wants. And, indeed in the name of good relations, American diplomats have allowed their Chinese counterparts to outmaneuver them to make profound gains in an array of areas—currency, trade, and security, to name a few—all the while tolerating China’s increasingly irresponsible, hostile, and dangerous behavior, which has frequently violated both international norms and law.

Since the beginning of his term, President Trump’s approach, on full display at his April meeting in Mar-a-Lago with Chinese ruler Xi Jinping, has been generous. And the early signs were positive. A couple of weeks after the meeting, the president suggested the two were cooperating, tweeting, “Why would I call China a currency manipulator when they are working with us on the North Korean problem?” Adding coyly, “We will see what happens.”

It appears now that in Trump’s view, insufficient progress has “happened,” as it were, because the administration’s approach has changed. In late June, the president began to impose costs by designating the Bank of Dandong a “primary money laundering concern,” a long overdue move that essentially sawed off the shady institution’s links to the global banking system.

Beijing was certainly displeased, but Geng’s denial of his country’s responsibility for North Korea’s arms build-up and missile tests suggest Chinese officials hope to head off additional American sanctions.

Beijing’s problem, however, is that as North Korea’s primary benefactor and life-line, much of its ongoing and multi-faceted commercial, security, and trade relationship with the Kim regime directly violates US law, the Patriot Act in particular.

Some of China’s larger banks appear to have washed cash for the Kim regime, a primary suspect being the Bank of China, one of China’s so-called Big Four banks. The bank was listed in a 2016 UN report for designing and operating a money-laundering scheme for Pyongyang.

In the last few weeks, a number of analysts have proposed schemes to disarm or defang the Kim regime. Yet, Kim would come under considerable pressure if the US would simply enforce existing law, designed to prevent foreign banks from laundering currency. That law puts Chinese financial institutions, working on behalf of Kim Jong Un’s destitute and dangerous state, in the crosshairs.

China can expect more banks to suffer the fate of the Bank of Dandong. The Trump administration is targeting other financial institutions laundering cash for the Kim regime—some of them believed to be Chinese—and it is also seizing the funds of parties dealing with North Korea, like Dandong Zhicheng Metallic Material Co. and four related front companies.

The Chinese will complain about America’s “long-arm” jurisdiction, but for the moment this White House seems determined to reconsider its criteria for “good relations” with China by preventing Chinese and other banks from aiding Pyongyang. Beijing will not be pleased and that’s why a downward—and healthy—spiral in relations can be expected.

OG Image: Asia PacificNorth AmericaChinaKoreaNorth KoreaSouth KoreaUSTrumpgovernment officials

Asia PacificNorth AmericaChinaKoreaNorth KoreaSouth KoreaUSTrumpgovernment officials

July 3, 2017

Trump Dumping ‘China First’ Policies

It looks like America has a new China policy. On Thursday, the US sanctioned a Chinese bank and approved an arms sale to Taiwan, angering Beijing. Does the Trump administration care?

Probably not. Reuters reports that US officials believe President Trump is unhappy with Beijing and is thinking of trade actions against China. His frustration follows more than two months of generally unsuccessful attempts to get the Chinese to help Washington disarm North Korea.

“They did a little, not a lot,” said a US official, speaking anonymously to the news organization. “And if he’s not going to get what he needs on that, he needs to move ahead on his broader agenda on trade and on North Korea.”

Trump sang the praises of both China and its leader, Xi Jinping, after the pair met in Mar-a-Lago in early April. Xi “wants to do the right thing,” Trump said a few days after their get-together. “I think we had a very good chemistry together. I think he wants to help us with North Korea.”

“Nobody’s ever seen such a positive response on our behalf from China,” Trump declared that same month. The American president, referring to Xi, proclaimed he had “absolute confidence that he will be trying very, very hard.”

That was April. How about June? On the 20th of this month, Trump surprised just about everyone by taking a markedly different line. “While I greatly appreciate the efforts of President Xi & China to help with North Korea, it has not worked out,” he tweeted.

The tweet, observers recognized, signaled a new China policy. Less than a week later, the State Department did not give China another waiver and dropped the country to the worst ranking—Tier 3—in its annual Trafficking in Persons report, released Tuesday. The report, among other things, cites China’s use of forced labor from North Korea.

Now, many expect tougher American action on trade as well. China got a sweet deal from the Commerce Department in the agreement announced May 11. Technically, the 10-point plan represented the “initial results” of the Trump administration’s “100-day action plan” on trade, announced at the conclusion of the Mar-a-Lago meeting. The May 11 deal looked favorable for Beijing, indeed some believe it may well increase America’s trade deficit with China.

It’s unlikely the Trump administration will be so agreeable on July 16, when the 100th day of the 100-day plan arrives. “What’s guiding this is he ran to protect American industry and American workers,” said a US official to Reuters, referring to the president.

One assumes Trump thought he could leverage a favorable trade deal with Beijing for a serious effort on its part to rein in North Korea. Perhaps the president fancied himself as the master of the deal, but forbearance on predatory Chinese trade practices should never have been used as an enticement to get Beijing to pressure Pyongyang. Workers in, say, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin are not bargaining chips, and, even if they were, the tactic for various reasons was doomed from the beginning.

Now that it’s clear Trump’s April stratagem has failed, we will very likely see an across-the-board deterioration in ties between Washington and Beijing as Thursday’s actions on the Chinese bank and Taiwan arms sales suggest. The US is involved in disputes with China involving, among other things, cyberattacks, freedom of navigation, proliferation, and human rights, and the severity of the disagreements seems to grow with time.

Previous US administrations subordinated America’s interests and let these and other issues fester as they sought to integrate China into the international system. Trump, however, has announced he will not pursue what has amounted to the “China First” policies of his predecessors. In any event, the moment for resolution is upon us.

None of this is to suggest that Trump will solve these challenges to America’s satisfaction, but at least now there is the possibility of success.

OG Image: Asia PacificNorth AmericaChinaUnited States

Asia PacificNorth AmericaChinaUnited States

May 23, 2017

China’s Empty Promises to Rein in North Korea

Last Wednesday, Chinese fighters intercepted a US Air Force WC-135 Constant Phoenix in international airspace near North Korea.

The mission of the WC-135, known as a “sniffer,” is to detect radioactivity in the atmosphere following a nuclear detonation. It appears this plane was in the region on a routine mission in anticipation of the North’s sixth detonation.

Two Chinese Su-30 interceptors came within 150 feet of the WC-135, and one of the fighters flew inverted above the American craft. “While we are still investigating the incident, initial reports from the US aircrew characterized the intercept as unprofessional,” said a statement issued by Air Force spokeswoman Lt. Col. Lori Hodge on Friday. “The issue is being addressed with China through appropriate diplomatic and military channels.”

Among the obvious issues to be addressed are the hostile nature of the intercept and the reckless endangerment of the American crew.

Moreover, the circumstances of China’s intercept of the WC-135 suggests Beijing is still trying to protect its client state from the US and the rest of the international community. The apparent message of the incident Wednesday is that the US Air Force should conduct no more reconnaissance of North Korea.

Indeed, the incident is totally in keeping with China’s long history of insincerity characterized by empty, false, feigned, and betrayed promises to rein in the Kim regime.

President Trump has boasted about his good relationship with his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, and has often claimed that Beijing is helping the US on North Korea. “Nobody has ever seen such a positive response on our behalf from China,” the US leader said in April.

Let’s hope the administration is alert to the rather disconcerting indications to the contrary because, alas, the brazen buzzing of the WC-135 is not the only sign that China’s returned to its duplicitous ways.

On February 18th China announced it would finally comply with UN sanctions by halting purchases of Korean coal—a vital source of hard currency for the Kim family state—for the remainder of the year. Yet, it turns out that China bought coal in February after the announcement, then again in April, and again in May.

Oh, of course Beijing makes excuses and extends promises of future compliance. In the meantime, Pyongyang continues to methodically build its nuclear-delivery capacity.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaKoreaNorth KoreaUS

Asia PacificChinaKoreaNorth KoreaUS

April 27, 2017

Is Beijing Serious About Restraining Kim Regime?

On Monday, Human Rights Watch asked China to immediately reveal the location of where it is holding eight North Korean defectors.

The group of defectors was stopped after a random traffic check in the northeastern city of Shenyang in mid-March.

“There is no way to sugar coat this: if this group is forced back to North Korea, their lives and safety will be at risk,” said Phil Robertson of Human Rights Watch. North Korea, now and in the past, has subjected returned defectors to “torture, sexual violence, forced labor—and even worse,” he said in a statement. That is especially true for those returned more than once.

At least four of those detained are females. “President Trump and Chinese President, please save us,” one of the women said in a video. “If we go back to North Korea, we will be dead.”

China does not care. “Some North Korean citizens, due to economic reasons, illegally crossed China’s border,” said Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang, at a regular news briefing. “This violates Chinese law.”

These defectors are not the only ones violating the law. China violates international law when it automatically classifies North Koreans caught on Chinese soil as “economic migrants” and repatriates them. By not protecting refugees fleeing persecution, China ignores its obligations under the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, more commonly known as the 1951 Refugee Convention. Moreover, without justification Beijing restricts access of the UN High Commission for Refugees to North Korean defectors held by Chinese authorities.

Geng says “China consistently handles this kind of issue prudently and appropriately according to domestic and international law, and humanitarian principles.”

On occasion, Beijing will conform to accepted humanitarian norms and does not return defectors to the authorities in Pyongyang, and, indeed, allows defectors to travel to South Korea, where all those fleeing the North are welcome.

So how does Beijing decide which defectors to release to the South? International pressure certainly affects decision-making in the Chinese capital. Another factor is how China’s policymakers view North Korea. In the past, when relations between Beijing and Pyongyang have been particularly tense, China has signaled its displeasure by allowing detained defectors to go to the other Korea.

If China follows its routine, the group detained in Shenyang will be returned to North Korea in about two weeks. If not, the refugees will find freedom and shelter in South Korea. Wherever Beijing sends the refugees—to freedom or imprisonment—will reveal much regarding Beijing’s true relationship with the Kim regime and the seriousness of its efforts to tame it.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaSouth KoreaKoreaPhilUSNorth KoreaRefugeesPresident

Asia PacificChinaSouth KoreaKoreaPhilUSNorth KoreaRefugeesPresident

April 14, 2017

US Dispatches Carrier Strike Group to Korean Peninsula

On Saturday, the USS Carl Vinson strike group, the aircraft carrier escorted by two guided-missile destroyers, and a guided-missile cruiser, left Singapore and headed to the Sea of Japan. The strike group was originally scheduled to sail to Australia.

The deployment of the Carl Vinson off the Korean peninsula is intended to deter North Korea as well as reassure allies of American commitment. It will also be ready to go to war if need be.

The Department of Defense has been downplaying the group’s deployment as an act of prudence. “There’s not a specific demand signal or specific reason we’re sending her up there,” said Secretary of Defense James Mattis at a Pentagon news conference Tuesday. “She’s stationed in the Western Pacific for a reason. She operates freely up and down the Pacific and she’s on her way up there because that’s where we thought it was most prudent to have her at this time.”

The line between deterrence and provocation is thin, so any US response to North Korean provocation could trigger conflict. Nonetheless, a show of force is necessary.

Why? Because passivity in the face of provocation and aggression in the past has invited more provocation and aggression. For example, in March 2010, a North Korean submarine torpedoed the Cheonan, a South Korean frigate, killing 46 sailors. The Pentagon planned to send the USS George Washington strike group to the Yellow Sea, near the site of the sinking. Beijing did not want the American vessel so close to its shores—the Yellow Sea lies between China and Korea—and vehemently objected to the planned deployment.

One Chinese flag officer, almost certainly speaking as part of a Beijing-directed and coordinated campaign, threatened to sink the George Washington, which like the Carl Vinson is a Nimitz-class carrier. China would make the George Washington “a live target” if it entered the Yellow Sea boasted Luo Yuan, a Chinese major general, in July.

The threat was clearly empty. China would not have precipitated an all-out war with the US because an American warship was sailing in international waters. The Obama White House, nonetheless blinked and chose not to send the George Washington group into the Yellow Sea.

That choice was a mistake. The Obama administration thought it was exercising restraint. Beijing celebrated the American decision, and North Korea acted. In November of that year, the North Korean military shelled Yeonpyeong Island, not far from the site of the sinking of the Cheonan. Four South Koreans died, two of them civilians.

There are many lessons to take away from the sequence of events in 2010, but the most important of them is that when American resolve yields to “restraint” and passivity, deterrence fails. And nothing good happens when American deterrence fails.

OG Image: Asia PacificNorth AmericaUSSouth KoreaSingaporeJapanAustraliaKoreaNorth KoreaJames MattisPentagon

Asia PacificNorth AmericaUSSouth KoreaSingaporeJapanAustraliaKoreaNorth KoreaJames MattisPentagon

March 29, 2017

North Korea Ready for Its Sixth Nuclear Test?

North Korea appears on the verge of conducting its sixth test of a nuclear device.

There were two nuclear tests last year and three in total during the rule of Kim Jong Un, who came to power in December 2011.

Recent satellite images show virtually no activity at the North Portal of Punggye-ri test site, in the northeastern corner of the country. Earlier, the activity there was “extensive.” And, as CNN has reported, that sequence is similar to the “pattern of activity just before previous tests, indicating all final preparations are now complete.”

Commercial satellite imagery supports that conclusion. The widely followed 38 North site, maintained by the US-Korea Institute of John Hopkins’s School of Advanced International Studies, reports that images taken on Saturday suggest that technicians have laid communication cables. Moreover, images show pumps are taking water from the tunnel where a nuclear device is thought to be positioned for the test. The pumps are necessary to keep dry both cables, used to trigger a detonation and collect data, and monitoring equipment.

South Korean and US officials believe a test will occur soon. “It is assessed that North Korea is ready to carry out a nuclear test anytime if its leadership decides to do so,” said Lee Duk-haeng, spokesman for South Korea’s Ministry of Unification, on Friday.

The US Air Force has moved a WC-135 Constant Phoenix “sniffer” plane to Japan while Russia has flown an Antonov An-30R craft from its St. Petersburg base.

So when will Mr. Kim detonate the nuclear device?

Korea watchers believe the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea times tests for maximum political effect. Those timing considerations can, we often forget, be driven by internal as well as external considerations.

Indeed, there does seem to be turmoil in Pyongyang. Beginning in late January and up to the middle of last month, a series of troubling incidents occurred: the minister of state security, General Kim Won Hong, was demoted; five of General Kim’s subordinates were executed by antiaircraft fire; the head of the country’s strategic missile forces was notably missing at the February 12 launch of an intermediate-range missile; and Kim Jong Nam, Kim’s elder half-brother, was murdered in a bustling airport when the chemical nerve agent VX was smeared over his face by two females working for the Kim regime. A successful test of a nuclear device now would tend to reinforce Kim’s standing internally, especially within the leadership of the Korean People’s Army.

And then there are external considerations that could account for the timing of a detonation. Kim, like his father before him, obviously enjoys reminding the civilized world that he can be a menace at the push of a button. He certainly seemed to relish the moment last month, on the 12th, when he launched an intermediate-range missile while President Trump and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe golfed and dined at Mar-a-Lago. It was Kim’s first test of a ballistic missile this year.

There is another Mar-a-Lago event that could be made-to-order from Mr. Kim’s perspective: the much-anticipated first meeting of Trump and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping. The gathering is rumored for April 6 to 7.

But one wonders if the timing of a detonation doesn’t also suit China’s purposes. Certainly, Beijing has noticed that it benefits when Kim misbehaves, given the course of events that inevitably repeats itself after Pyongyang conducts a nuclear test or does something especially provocative. Indeed, the resulting diplomatic frenzy distracts Washington from other issues—like China’s aggressive moves in its peripheral waters, its cyberattacks on American institutions, and its predatory trade practices. No one in Washington raises human rights abuses when the West “needs” China.

When China is needed, Beijing’s stature and influence rises. And, in due course, American presidents dispatch their secretary of state or some high-ranking envoy to Beijing to seek its assistance. In turn, Beijing uses its leverage to extract promises, concessions, or silence from the US. In effect then, North Korea’s belligerence, saber rattling, and provocations manufacture bargaining chips for China. It is inconceivable that Beijing is unaware that this tidy pattern of cause and effect suits its purposes nicely. Indeed, one must ask if Beijing isn’t in fact orchestrating the pattern.

So if Kim Jong Un decides to push the button on or before the end of the Mar-a-Lago get-together, Xi Jinping may condemn the test in public but secretly smile.

OG Image: Asia PacificKoreaNorth Korea

Asia PacificKoreaNorth Korea

March 21, 2017

Tillerson's Deference to Beijing or Unfortunate Rookie Mistake?

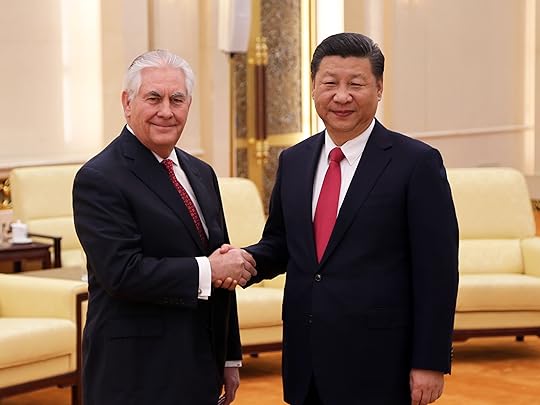

“You said that China-US relations can only be friendly,” Chinese President Xi Jinping said to Secretary of State Rex Tillerson on Sunday. “I express my appreciation for this.”

Beijing could not be more pleased with Tillerson’s choice of words. Chinese state media is now crowing because the American diplomat, who seemed resolute in Tokyo and Seoul, appears to have turned deferential in Beijing—perhaps unwittingly. In the Chinese capital, he repeated in public the preferred Chinese formulation of relations between the two powers. On the preceding day at a press conference with his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi, Tillerson said ties between the two countries were guided by “non-conflict, non-confrontation, mutual respect, and win-win cooperation.”

Global Times, the nationalist tabloid controlled by People’s Daily, cited unnamed “analysts” who declared that Tillerson, by uttering this phrase, “implicitly endorsed the new model of major power relations,” Beijing’s buzz phrase adopted in 2010.

By incorporating Beijing’s diplomatic terminology into his remarks, Tillerson either exposed a glaring deficiency in the staffing for the visit or a dramatic shift in American policy. It is likely the former. Based on any number of previous statements, it is clear Washington has no plans to cozy up to Beijing or to refrain from confronting aggressive Chinese behavior.

On the other hand, the US Secretary of State looks a bit uninitiated and, worse, Beijing will be disappointed that American behavior in the wake of Tillerson’s remarks will not conform to the expectations he created—a disappointment that will complicate relations at a crucial time. Tillerson’s remarks, in short, make him look like a “rookie,” the Wall Street Journal’s accurate characterization of him.

The Obama administration, in its early years, rarely repeated China’s formulations of Sino-US ties, and it completely avoided doing so as time progressed and relations deteriorated.

America’s China-watching community immediately pounced on Tillerson after the Saturday presser. The Washington Post used this as its headline on Sunday: “In China Debut, Tillerson Appears to Hand Beijing a Diplomatic Victory.”

Tillerson’s use of “mutual respect,” said Bonnie Glaser of the Washington, DC-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, is acceptance of “a litany of issues that China views as nonnegotiable.” “By agreeing to this,” she stated, “the US is in effect saying that it accepts that China has no room to compromise on these issues.”

“China’s characterization of the US-China relationship, as exemplified by those phrases, portends US decline and accommodation,” said Ely Ratner, who worked for Vice President Biden, to the Post. “Tillerson using these phrases buys into this dangerous narrative, which will only encourage Chinese assertiveness and raise doubts in the region about the future of US commitment and leadership in Asia.”

Overreaching headlines and commentary aside, it’s near certain that the new secretary of state, like Obama administration officials before him, will not feel particularly constrained by Beijing’s interpretations of phrases he used. Still, it would have been far better for Tillerson to have employed the diplomatic terminology that affirms the US’s position rather than repeating phrases that Ratner properly calls Chinese “platitudes and propaganda.”

When it comes to diplomacy, words matter. At this consequential time, American leaders and diplomats must demonstrate that they are ready for the global stage by saying what they mean and being clear. In particular, the Trump administration should demonstrate a nuanced understanding of its delicate relationship with China, but in any event our regional allies need to see that Washington will no longer defer to China’s increasing hostility and aggression in its peripheral seas, border areas, cyberspace, and elsewhere.

Every American administration in its early days tries to establish cooperative relations with Beijing, and President Trump’s will not be an exception. Unfortunately, friendly words, misspoken or intentional, will not persuade Chinese leaders to abide by international norms.

Like those before him, Tillerson will discover this soon enough.

OG Image: Asia PacificNorth AmericaUnited StatesChinaRex TillersonXi Jinping

Asia PacificNorth AmericaUnited StatesChinaRex TillersonXi Jinping

March 15, 2017

Nonstarter: North Korea's Enablers in Beijing Pose as Neutral Observers

On Wednesday, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi attempted to defuse tensions in North Asia, proposing that North Korea suspend the testing of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles and the US and South Korea suspend military exercises.

Wang’s comments suggest Beijing has become deeply concerned—alarmed even—and is trying to prevent what it sees as a potentially disastrous situation on the Korean peninsula.

The distress inside the Chinese capital is evident. “The two sides are like two accelerating trains coming toward each other, with neither side willing to give way,” Wang said in Beijing. “The question is: Are the two sides really ready for a head-on collision?”

Beijing’s solution is “to flash the red light and apply brakes on both trains.” “We will switch the issue back onto the track of seeking a negotiated settlement,” he said as he compared his country to “a switchman.”

Wang’s proposal is almost unprecedented in that it was made out in the open, where rejection would lead to embarrassment for a Beijing that does not like being rejected in public.

The public nature, therefore, suggests Beijing’s apprehension, but the foreign minister’s comments reveal two other things. First, they show that China’s perceptions of the North Korean situation differ greatly from those of others parties. China’s Communist Party, which has supported the Kim family since the founding of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in 1948, is not some neutral observer. It is a direct participant responsible for the maintenance the Kim dynasty’s rule over the course of decades.

“Engineer,” therefore, is a far closer description of Beijing’s role than “switchman” if we continue with Wang’s railroad metaphors. Eyes in Washington and Seoul must have rolled when Guo Rui of Jilin University called China a “victim of the turbulent situation on the Korean Peninsula.”

Chinese officials point to strained relations with Pyongyang and promote the victimization narrative, yet we have to remember that Beijing supports the Kims not because they are friendly to China. Beijing supports the Kims because they promote important short-term Chinese objectives.

Every time North Korea does something provocative—detonate a nuclear weapon or launch a missile, for instance—Washington gets distracted from other issues and then seeks Beijing’s help, effectively giving China bargaining chips.

Analysts—many of them Chinese—say that China’s support of Pyongyang is not in their country’s long-term interests. They are correct, but Chinese policymakers, whether out of inertia or cynicism or misjudgment—or designed and duplicitous strategy—are continuing to support their long-time ally, in fact their only formal ally. Others may think China should calculate its interests differently—and they are also correct—but Chinese leaders see the world from a perspective not shared by others.

Second, Wang’s proposal was an obvious nonstarter and suggests Chinese diplomats are not ready to play a brokering role on the Korean peninsula. The apparent theory behind the Chinese “suspension-for-suspension” or “double freeze” concept is that US and South Korean forces do not need to prepare to defend the South if the North does not have a developed nuclear weapons and missile capabilities.

That proposition is manifestly untrue. North Korea maintains the world’s fourth-largest army in the world—behind India and ahead of Russia—and about 70 percent of its troops are forward-deployed, within 60 miles of the Demilitarized Zone separating the two Koreas. Pyongyang also has large stocks of chemical and biological agents. Washington and Seoul have consistently rejected proposals in the past to end the drills because readiness would quickly degrade if they were to stop the exercises.

It’s unclear why Foreign Minister Wang would publicly make a proposal that would almost certainly be rejected, unless he were trying to tar Washington and Seoul. Yet if China is genuinely disturbed by the crisis-like atmosphere on the peninsula—and there are indications it in fact is—the making of a dead-on-arrival proposal undermined China’s position in the region and served no discernable goal.

Asia PacificChinaKoreaNorth Korea

Asia PacificChinaKoreaNorth Korea

February 28, 2017

China Seeking Global Leadership

In January at Davos, Chinese leader Xi Jinping cast himself as the defender of globalization, and in a February 17 seminar in Beijing he said his country would promote a sounder international system.

These recent speeches by Xi, China’s ruler since November 2012, suggest Beijing is seeking to displace America’s leading role in the international system. Statements by President Donald Trump, both before and after inauguration, have opened the door for Beijing to make rhetorical advances. Fortunately for Washington, it is not possible for Xi to align his country’s internal and external policies with his benign-sounding words.

Xi has been busy issuing grand statements. “Whether you like it or not, the global economy is the big ocean that you cannot escape from,” he said in Davos as the first Chinese leader to address the World Economic Forum. “Any attempt to cut off the flow of capital, technologies, products, industries, and people between economies, and channel the waters in the ocean back into isolated lakes and creeks is simply not possible. Indeed, it runs counter to the historical trend.”

And he promised this: “We will open our arms to the people of other countries and welcome them aboard the express train of China’s development.”

And, later at the Beijing seminar in mid-February, Xi offered his thoughts of a newly “democratized” and “just and reasonable” world, presumably led by China. He promised to promote the “democratization of international relations” and “guide the international community to jointly maintain international security.” Beijing, he said, could help build “a more just and reasonable new world order.”

Of course, ironies, hypocrisies, and absurdities abound. On globalization, Xi cannot credibly portray himself as the defender of economic integration. During his rule, China has increasingly closed off its economy to foreign participants, primarily with highly discriminatory law enforcement actions and the erection of formal legal barriers, such as those contained in new national security rules and regulations like the Cybersecurity Law adopted in November.

Moreover, his tightened internet controls, which affect businesses’ ability to operate, are sawing China off from the rest of the planet while his increasingly strict capital controls prevent companies from repatriating funds.

China’s leader can say whatever he wants, but the foreign business community is day-by-day feeling less welcome, as evidenced by the most recent surveys conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in China and the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China.

And with regard to regional security, no country in East and South Asia, with the possible exception of China’s client North Korea, represents a more immediate threat to its neighbors than does China itself. China, among other things, is territorially expansive and diplomatically and militarily aggressive—using coercion and force in its attempt to take territory from an arc of countries spanning thousands of miles from India to South Korea. Moreover, Beijing is attempting to control and close off peripheral waters—South China Sea, East China Sea, and the Yellow Sea—and the airspace above them.

Worse, Chinese ambitions are expanding as state institutions and state media are laying the groundwork for sovereignty claims to Japan’s Okinawa and the rest of the strategic Ryukyu chain.

When the Chinese talk about “democratization,” they mean every state should have equal influence in the world order. As a practical matter, China seeks a leveling of the existing system that would, first and foremost, diminish American influence.

America has been the traditional security provider in East and South Asia, and these days not even North Korea wants to replace the US with China.

OG Image: Asia PacificChina

Asia PacificChina

Gordon G. Chang's Blog

- Gordon G. Chang's profile

- 52 followers