Gordon G. Chang's Blog, page 5

July 8, 2016

Expansionist China and Russia Deepen Ties

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin met on the 25th of last month in Beijing and issued statements bound to upset their neighbors and the US. For instance, the two leaders, who are both using force to expand and secure their borders, drew upon Orwellian logic when they charged that the nations defending themselves are the ones destabilizing the international system, undermining “strategic stability,” as they put it.

Yet Putin and Xi typically issue provocative statements intended to intimidate neighbors and threaten the international order when they meet. The more important story of the one-day get-together is that the two countries remain on course to become “friends forever”—Xi’s words—and they are cementing that friendship with trade.

During Putin’s visit, his fourth since Xi took over in 2012, the two announced several deals. Russia sold interests in various energy projects to Chinese enterprises, while China took stakes in Russian petrochemical projects. They signed a one-year contract for Rosneft to sell crude oil to China National Chemical Corporation.

With those inked, Putin also remarked there are 58 deals worth about $50 billion under discussion. Among them is a high-speed, 770-kilometer rail line that will connect Moscow with Kazan, to be built by China. Said Putin, “We are pursuing economic cooperation, as China is the first trade partner of Russia.”

Still, the drop in energy prices in recent years has prevented the two countries from reaching their trade goals, and it is unlikely they’ll meet their 2020 target of $200 billion. Last year, bilateral trade was only $64.2 billion, down 27.8% from 2014.

Yet, what is significant about Sino-Russia trade is not the fluctuations in volumes but rather that in a difficult period for both, they appear determined to entwine their economies.

Last year the Russian economy contracted 3.7%. The Kremlin, which has been notoriously overoptimistic, now suggests growth will be “near zero.”

China’s economy is rapidly decelerating, and declining trade is not helping. Last year, China’s trade of $3.96 trillion was down 8.0% from 2014. Exports dropped 2.8% while imports plummeted 14.1%. The trend line is holding. In the first five months of this year, exports were off 7.3% from the same period in 2015. Imports were down 10.3%.

The authoritarian and expansionist Dragon and Bear, which have much in common, need each other. By deepening trade ties and integrating their economies, China and Russia not only increase their ability to challenge the international system, they also increase the likelihood they will do so. As Ian Ivory, a China-Russia watcher notes, Sino-Russian trade is driven by geopolitical as well as economic considerations.

Everyone, therefore, has an interest in the persistent trade and investment efforts of the Kremlin and Beijing.

OG Image: Asia PacificEurope and Central AsiaChinaRussiaVladimir PutinXi JinpingInvestmentChina EconomyDiplomacyBilateral relations

Asia PacificEurope and Central AsiaChinaRussiaVladimir PutinXi JinpingInvestmentChina EconomyDiplomacyBilateral relations

June 24, 2016

China Steps Up Provocations

Chinese incursions along its southern and eastern peripheries this month suggest an increase in the pace of territorial provocations.

On June 15, one of China’s intelligence-gathering ships entered Japan’s territorial waters in the wee hours of the morning. The Dongdiao-class vessel sailed near Kuchinoerabu Island and the larger Yakushima Island as it shadowed two Indian warships participating in the Malabar exercise with the US and Japan. The intrusion was the first since 2004, when a Chinese submarine entered Japan’s waters, and only the second by China since the end of the Second World War. Japan filed a protest, but China countered that it was transiting in compliance with international freedom of navigation rules. China's ship lingered for some 90 minutes, possibly in violation of international transit norms.

A few days earlier on June 9 a Chinese frigate for the first time entered the contiguous zone off the Senkakus, a group of small Japanese-controlled islands that Beijing claims and refers to as the Diaoyus. Tokyo has exercised control over the islands and the surrounding region since 1972, when Washington relinquished administration of Okinawa and the rest of the Ryukyu chain. In a related development, it might be noteworthy, state media has been hinting that China will seek control of the Ryukyus as well.

On June 7, two Chinese aircraft intercepted a US Air Force RC-135 reconnaissance plane over the East China Sea. The US Pacific Command labeled the close fly-by “unsafe.”

There have been provocations in surrounding regions as well. On June 16th, a Chinese vessel deliberately rammed a Vietnamese fishing boat during an hours-long chase near the Paracel Islands. And, just last week China’s fishing trawlers were again spotted and tracked in Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone near the Natunas, sparking a confrontation involving gunfire.

And if that were not enough, Chinese troops intruded into Indian-controlled territory at four separate spots in the state of Arunachal Pradesh on the 9th of this month.

All the while, China continues to make expansive claims in the South China Sea, where it is rapidly fortifying the Spratly chain of islands. At the same time, it is surveying Scarborough Shoal, which it took from the Philippines in 2012, with the apparent intention of reclaiming it, making permanent its seizure. Some believe a reclamation there, just over 120 nautical miles from the main Philippine island of Luzon, will be its response to an anticipated ruling against China at the Hague in a case brought by Manila.

The quickening pace and expansion of China's provocations raise questions about why Beijing has chosen this moment to increase tensions wide and far. Are we seeing a new confidence among China’s civilian leaders who believe they can intimidate their neighbors and the international community simultaneously? Or, might those political leaders have lost control of aggressive generals and admirals who act now with little or no authorization from policymakers?

In any event, Chinese policy this month may have taken a dangerous turn.

OG Image: Asia PacificChina

Asia PacificChina

June 15, 2016

China Likely Cheating, Again, on North Korea Sanctions

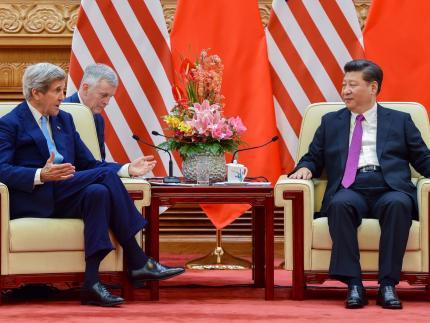

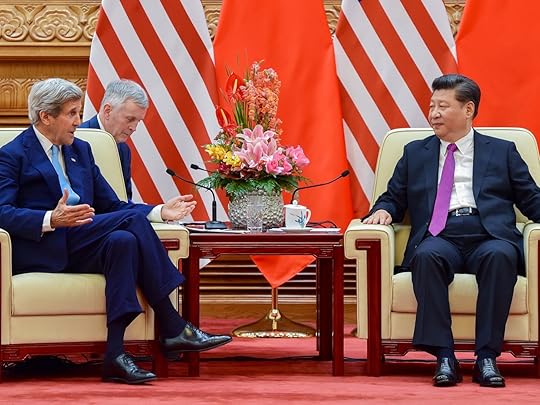

“We are both determined to fully enforce the UN Security Council Resolution 2270,” said Secretary of State John Kerry on Tuesday, referring to China and the US. As hundreds of American and Chinese officials wrapped up this year’s installment of the Strategic and Economic Dialogue in China’s capital, America’s top diplomat wanted the world to believe Beijing was complying with international sanctions on North Korea.

Resolution 2270 is the fifth set of coercive measures imposed by the Security Council on Pyongyang for its weapons programs.

So is Kerry telling us what is in fact the case or what he would like to be true? Unfortunately, it’s the latter.

Beijing has been making the right noises about compliance. President Xi Jinping, for instance, pledged China would “completely and fully” enforce the UN’s coercive measures.

And following their passage, Beijing announced severe restrictions on trade. Chinese ports, for example, did not accept coal shipments from North Korea, prohibiting fully laden vessels from unloading cargoes.

There were also unprecedented restrictions on trade of various items, especially rice and construction materials, even though they were not subject to the new UN sanctions. Moreover, Beijing put 31 North Korean vessels on a “blacklist.”

In the past, Beijing made public shows of compliance when sanctions were first imposed and then, when the international community was looking the other way, flouted them across-the-board. That’s how Kim Jong Un, the young North Korean despot, could buy the ski lifts for the Masikryong resort or how his father, Kim Jong Il, could obtain the 16-wheel mobile transporter-erector-launchers for the KN-08 missile, which can dispatch a nuclear weapon to the the continental US. Pyongyang could, one way or another, get almost anything from or through China.

And now again this year it looks like Beijing is following its oft-used playbook. Chinese statistics show no oil flowing to the North, but it appears to be as South Korean media reports.

Moreover, despite apparent attempts at enforcement, a significant amount of goods and commodities under sanction are now crossing the China-North Korea border, especially items considered vital to the Kimist regime.

Beijing, for instance, did nothing or virtually nothing to stop the export of sanctioned luxury goods intended as gifts to the attendees of the 7th Workers’ Party Congress.

Most worryingly, China did not interrupt the flow of materials and components for Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons program, such as cylinders of uranium hexafluoride. Also allowed into the North were vacuum pumps, valves, and computers.

At some point, Kerry needs to drop the pretense and call out China in public for conduct violating its international obligations—and which contributes to a regime that is a grave threat to the world.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaUnited StatesNorth KoreaJohn KerryXi Jinping

Asia PacificChinaUnited StatesNorth KoreaJohn KerryXi Jinping

June 6, 2016

US Pressures Kim Regime in North Korea

On Saturday, Pyongyang reacted to the Wednesday designation, by the US Treasury Department, of North Korea as a “primary money laundering concern” pursuant to Section 311 of the Patriot Act.

“North Korea is not frightened in the least by the US’s stereotypical method of labeling us as ‘money launders,’ not being content with already branding us as ‘nuclear proliferators,’ ‘human rights abusers,’ etc.,” said a spokesperson for the North Korean National Coordination Committee.

Pyongyang, despite the bravado of the statement, is undoubtedly concerned. The practical effect of the move is that banks and other financial institutions, both American and foreign, will not handle dollar transactions for Pyongyang’s entities and fronts. In all probability, these institutions will also shun dealings in other currencies for these customers.

And Beijing is also concerned. For the most part, North Korean banks plug into the international financial system through Chinese ones. The New York Times recently quoted Andray Abrahamian of Choson Exchange in Singapore, a nonprofit providing training for North Korean entrepreneurs, to the effect that big Chinese banks stopped doing business with North Koreans in 2013.

There is some evidence, however, that the biggest Chinese banks—Bank of China, China Merchants Bank, and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China—kept some of those relationships until early this year, when Beijing apparently ordered them to cut off dealings. Moreover, Bank of Dandong, a much smaller institution at the China-North Korea border, severed its relationships with North Koreans at about the same time.

These and other Chinese banks will lose substantial revenue, in the billions of dollars according to some estimates. It is no surprise, then, that China’s Foreign Ministry immediately complained of Treasury’s designation, which amounts to a unilateral sanction, but these banks will undoubtedly fall into line with Washington’s order, at least at first.

Chinese banks made a show of complying in 2005. Then, Treasury designated Banco Delta Asia, a Macau bank handling North Korean transactions, a money launderer, essentially freezing $25 million. Caught off guard, Pyongyang was forced to use diplomats to ferry cash in suitcases around the world. This time, the regime is thought to be better prepared to handle such a designation, but Treasury’s move will nonetheless make money transfers substantially more difficult.

And North Korea has to be worried about what comes next because the designation suggests Washington is adopting a harder approach toward the regime of Kim Jong Un. Up to now, American policy has been designed “to bring the North to its senses, not to its knees,” as Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Russel said nearly last month.

Yet former State Department official Evans Revere, in an interview with NK News published at the end of May, argued that Washington should “take North Korea to the edge and have them stare into the abyss of the possible collapse of their system if they do not return to the negotiating table.” Moreover, Revere, once a tireless advocate of patience toward Pyongyang, said the US is already on that course. “I think there is a lot more coming,” he noted, referring to tougher US actions.

Days later, Treasury proved Revere right.

And there is more the US government can do. The State Department could have added to sanctions on Pyongyang on Thursday if it had re-designated North Korea a state sponsor of terrorism a prior designation was lifted in 2008. State did not do so, however, although some believe there were grounds for a re-designation.

Perhaps the terrorism-sponsorship designation is the next turn of the screw. In the meantime, Pyongyang will have to figure out how to move money around the world without banks. And how to deal with a Washington that, for the first time in years, looks serious about shoving it into the abyss.

OG Image: Asia PacificNorth AmericaUSSouth KoreaNorth KoreaTerrorismUS-China RelationsChina-North Korea TiesMoney Laundering

Asia PacificNorth AmericaUSSouth KoreaNorth KoreaTerrorismUS-China RelationsChina-North Korea TiesMoney Laundering

June 1, 2016

Hiroshima, Japan, and the US

“We can tell our children a different story,” said President Obama on Friday, after detailing the horrors of the day, 71 years ago, in which a “flash of light and a wall of fire” led to the deaths of some 140,000 in Hiroshima.

At the site of the first use of an atomic device in war, in Hiroshima, the American leader came to the Peace Memorial with messages for the future, one of them of disarmament. In the backdrop, was the Flame of Peace, first lit in 1964, which is supposed to remain burning until the world is free of nuclear weapons. While there, the president urged nations to give up their most destructive instruments of war.

The US has committed to do just that in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the global pact that entered into force in 1970. Ronald Reagan passionately believed in the goal and in 1986 at Reykjavik almost reached a complete disarmament deal with Gorbachev’s Soviet Union. Obama won his Nobel Peace Prize largely for his landmark address in Prague in 2009 in which he talked about a world without nuclear weapons.

In Asia at the moment, China is rapidly adding to its nuclear arsenal. North Korea, in defiance of the international community, is developing and selling the technology to such horrific weapons. Russia, also an East Asian power, is ignoring its obligations to the US in the landmark 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces agreement. Moreover, Moscow’s talk of increasing its nuclear arsenal makes it look like it is backtracking on—and perhaps planning to violate the New START treaty, signed in 2010.

At a glance, therefore, it seems that the proliferation of nuclear weapons, rather than their abolition, will mark Obama’s legacy in East Asia.

Yet, in their remarks in Hiroshima both President Obama and Prime Minister Abe point to a larger and longer lasting trend that can give hope. As Yuki Tatsumi of the Stimson Center’s East Asia Program told the Nelson Report, Japan and America have made an “extraordinary journey” from enemies to friends. Since the end of the war, friendship, cooperation, and a sense of reconciliation has defined the relationship between Japan and the United States. And at this moment, this bond is crucial.

Strengthening the alliance between the two nations is the first step to stopping the proliferation of nuclear arms in Asia.

Yes, Beijing has driven events with its military build-up and provocations, but on Friday the president and prime minister promoted an alternative narrative that can both guide and inspire friends and adversaries alike by offering common purpose.

For decades there has been too little good will, and too much animosity in East Asia, which makes the race for destructive weaponry especially dangerous. Last week showed that, despite the disturbing trends, there is reason to believe the region can be better than its past.

OG Image: Asia PacificJapanUSPresidentBarack ObamaObamaPresident ObamaPrime Minister

Asia PacificJapanUSPresidentBarack ObamaObamaPresident ObamaPrime Minister

May 25, 2016

American Hopes to Return to Prison Camp in North Korea

Since the Korean War, no American has spent longer in confinement in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea than Kenneth Bae. Yet Bae, released in 2014, wants to go back to see the guards who kept an eye on him in prison. As he told Seattle radio station KUOW on the 19th of this month, “I consider some of them as friends.”

So is this a particularly bad case of Stockholm Syndrome?

It’s not. Bae, a missionary, is out to educate the North Korean people, starting with those who kept him under lock and key in particularly harsh conditions.

During his confinement, Bae, a Southern Baptist minister, learned just how isolated North Korea has remained. Jesus Christ? One of his guards had never heard of him before. “Where does Jesus live?” his captor asked. “In China or North Korea?”

So how about a living figure of global renown, say, Ban Ki-moon? “Some people I asked, ‘Do you know that the secretary-general of the U.N. is actually South Korean?’ ” Bae told the Washington Times, “and the response that I got was, ‘No way, that is not possible.’”

Also not possible to North Koreans was that ordinary Americans lived in their own houses and drove their own cars. “They said, ‘No way. No way most common people can live like that,’” adding, “they were told that 1 percent of people in the United States have everything, and the rest of them are living in poverty. And this is what they were told throughout their lifetime.”

Also a revelation to his captors was that the South Korean economy is about 40 times larger than theirs. Said Bae, “They had no idea.”

In confinement, barriers broke down between Bae, born in South Korea in a family that had fled the North, and his guards. “People opened up quite a bit and one by one they’re coming to me and saying, ‘Pastor, can I talk to you?’” the missionary said to KUOW. “And then they’re talking about their marriage problems and parenting issues. So I ended up doing quite a bit of counseling and sitting down and talking and chatting.”

There is nothing so subversive to the Kim regime as information, which is why South Korean activists fly balloons carrying flash drives and DVDs over the Demilitarized Zone—and why Pyongyang is enraged by this activity.

Kim Il Sung, the charismatic World War II-era guerilla leader who grabbed power and built the North Korean state, walled off his new creation. After doing so, he was able to tell the populace whatever he wanted them to believe. He invented some whoppers, like those about his supernatural powers, but the North Korean people believed him.

Yet other untruths are especially dangerous to the regime because they can now be proven false, and Kenneth Bae, during conversations with prison guards, was able to expose some of them as such, bringing truth to a very dark land.

Bae says he wants to return to North Korea to see his captors, now friends. Yet in light of what he has just said, the last thing Kim Jong Un, the current ruler, is going to do is let him back in to expose one regime myth after another.

OG Image: North AmericaUSKoreaNorth KoreaSouth Korea

North AmericaUSKoreaNorth KoreaSouth Korea

May 23, 2016

China’s Coming Demographic Crash

China’s official Xinhua News Agency reports that Beijing’s obstetrics wards are overflowing. The city, according to the Health and Family Planning Commission, expects 300,000 births this year, an increase of twenty percent or 50,000 over 2015. Xinhua estimates that 22 million babies will be born nationwide in 2016.

Yet the talk about newborns seems to me a feeble attempt to mask a population crash that looms.

Effective the beginning of this year, the Chinese central government relaxed the notorious one-child policy to permit two children per couple. The liberalization will increase the birth rate nationwide, but, apart from state media, few think the increase will halt a severe decline in population.

“It’s already too late,” says Yi Fuxian of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a critic of Chinese population policies. “China’s population is aging quickly and will start to shrink soon."

According to the UN’s most recent set of statistics, the country’s population will peak in 2028 at 1.42 billion people. One Chinese official, speaking at a conference in 2012, said the country would top off in 2020. In any event, by the end of the century the country’s population will be just a hair over a billion according to the most optimistic assessment.

Speaking to the South China Morning Post, Yi predicts that China will soon find it difficult to increase fertility, and he looks to be correct. Once declining birth rates are baked into a society, they are extremely difficult to reverse. Governments can provide subsidies, but payments only accelerate births that would have occurred anyway. Even the removal of birth restrictions may not mean much when relentless indoctrination has taken hold, as it has in China.

China’s total fertility rate—generally, the number of births per female of childbearing age—is now low. There are varying estimates, but Yi pegs the number at 1.3. State media, citing the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, suggests it is 1.4. In any event, the number is well below that necessary to maintain a stable population, 2.1.

There are many consequences to low fertility. One casualty will be the hope of many Chinese officials that their economy will become the world’s biggest. “Not so long ago, conventional wisdom in China held that the country’s economy would soon overtake America’s in size, achieving a GDP perhaps double or triple that of the US later this century,” writes Howard French in The Atlantic. “As demographic reality sets in, however, some Chinese experts now say that the country’s economic output may never match that of the US.”

French notes that China now has a population that is about four and a half times as large as America’s but at the turn of the century China will be just a smidgeon more than twice that of America.

Well before then, China will pass an inflection point. In 2022, according to the UN, India will take China’s population crown. That will be the first time in at least three centuries—and maybe even in all recorded history—that China will not be the world’s most populous society.

Yi attributes China’s coming population crash to Beijing’s self-destructive policies that restricted births, or as he calls it, “my own nation’s suicide.”

OG Image: Asia PacificChina

Asia PacificChina

May 13, 2016

Kim Announces Vague Five-Year Economic Vitalization Plan

In his three-hour speech Saturday, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un announced his plan to vitalize the country’s beleaguered economy. “It is imperative to carry through the five-year strategy for the state economic development from 2016 to 2020,” he said, according to Rodong Sinmun, North Korea’s most authoritative newspaper.

Kim’s plan provides no tangible goals or overarching strategies, but the young leader, speaking at the Korean Workers’ Party 7th Congress, seemed to signal he was serious about economic development. His plan is the first since the Third Seven-Year Plan, which ended—two years late—in 1995.

Regardless of the absence of detail, Kim, by emphasizing the economy last week, essentially made himself accountable to a largely impoverished population that values prosperity far more than ideology. As is said these days, the North now has a “money culture.”

For the last five years, North Korea has had around 1% annual growth, so Kim has a base to build on. Yet he is trying to accomplish the improbable with his byungjin line, which promises economic development in tandem with the development of nukes and missiles.

His grandfather, Kim Il Sung, tried that toward the end of his rule and failed. His father, Kim Jong Il, had more modest goals. His songun—military first—policy fed the generals and admirals and their military but starved civilian society, literally and figuratively, and shrank the country’s economy.

As Kim Jong Un plots the country’s path to prosperity, the relatively tight international sanctions regime, put in place because of his enthusiasm for building weapons, will represent a major obstacle to his economic development aspirations. For example, Seoul closed the Kaesong Industrial Complex in February, depriving the regime of about $90 million in annual revenue. Moreover, UN Security Council Resolution 2270, adopted March 2, contains the tightest sanctions regime ever imposed on the North for its weapons programs.

So far, the international community, including China, has enforced the sanctions. If that solidarity holds, it will be difficult for Kim Jong Un to ramp up economic growth to meet the expectations he now cultivates. He has not articulated workable policies, nor does he have the resources or the foreign investment necessary to fuel robust economic expansion.

North Koreans have heard their leader announce that his five-year plan will deliver prosperity. They have heard it before, and it appears their tolerance is growing thin.

Asia PacificSouth KoreaUNKoreaNorth KoreaUNKim Jong Un

Asia PacificSouth KoreaUNKoreaNorth KoreaUNKim Jong Un

May 4, 2016

Great Power Confrontation in the South China Sea

On Friday in Beijing, Sergey Lavrov and Wang Yi, the Russian and Chinese foreign ministers, presented a united stand against the US on a host of issues in their joint press conference.

Among the topics were Beijing’s territorial claims. “We are of the same view with Minister Lavrov that the disputes around the South China Sea should be settled peacefully through negotiations among the directly involved countries,” declared Wang. “We discussed the situation in the South China Sea,” Lavrov noted. “The Russian stance is invariable—these problems should not be internationalized—none of the external players should try to interfere in their settlement efforts.”

The irony, of course, is that Russia, a non-claimant, was involving itself by telling others not to involve themselves.

The US and Russia are not the only non-South China Sea states believing they have an interest in that contested body of water. India and, more recently, Japan have also made their presence felt, sending ships through what they consider to be a part of the global commons.

New Delhi has for years regularly sailed its warships to ports in Vietnam, its friend. In July 2011, a voice over the radio, identifying himself as the “Chinese Navy,” attempted to stop the INS Airavat, an Indian amphibious assault ship, as it peacefully steamed through international water on its way to Haiphong. Japan, for its part, as recently as last month, dispatched warships to Subic Bay in the Philippines.

So there is great power contention. On one side, Russia supports China’s attempts to close off most of the South China Sea, while America, India, and Japan, among others, want to keep the waters open to all.

In effect, it’s a zero-sum contest where both sides see a critical—and non-negotiable—issue at stake. But what makes the South China Sea even more dangerous is that the sides are ill-defined at the moment. Like in the days that preceded World War I, the situation is difficult for participants to anticipate, much less manage, because it is unclear what other powers will do in the event hostilities break out.

The US, for instance, could now face not just Beijing but Moscow over, among other things, Scarborough Shoal. China seized that reef from the Philippines in early 2012, and it appears China intends to turn it into a military fortress through reclamation.

China, on the other hand, could see Japan join America in the defense of the Philippines. The combination of possible alliances is not endless, but uncertainty must confound planners and policymakers.

The question is, will ambiguity temp Beijing?

The danger at the moment is that deterrence can fail in this complex situation. Chinese planners today should be haunted by the lesson Kim Il Sung learned in June 1950.

The North Korean dictator calculated that, after Secretary of State Dean Acheson famously left South Korea out of America’s “defense perimeter” in Asia, no nation would defend Seoul, so he launched an attack that precipitated the Korean War. Yet the US unexpectedly came to the South’s rescue as did 15 other nations fighting under the UN banner. Those nations beat back Kim, who in turn had to be rescued by a reluctant China and Soviet Union. In the end, North Korea lost territory when the armistice was signed three years later.

The one thing we know is that no state will listen to Lavrov and Wang when they say that others should leave China alone, especially when Beijing uses aggressive military and diplomatic tactics against other claimants. And that means any incident, however minor or accidental, can flare up into a big-power confrontation.

All the conditions for conflict, therefore, are in place in the South China Sea.

OG Image: Asia PacificChina

Asia PacificChina

April 26, 2016

China’s ‘Triple Bubble’ Economy Poised to Burst

After a nearly disastrous start to the year in January and February, China’s economy steadied itself in March. Now, the early April indicators suggest a continuation of the uptick.

The China bulls, however, are premature in their projections of a sustained recovery. To the contrary, the economy appears poised to be a default or two away from a world-shaking crash.

When economic indicators look too good to be true, as China’s now do, they signal trouble ahead. There are two principal reasons why the present circumstances are cause for alarm.

First, Beijing’s official National Bureau of Statistics appears to be posting fantasy numbers. Notably, for the first time since 2010 when it began providing quarter-on-quarter data, NBS failed to release the quarterly comparison when it reported the year-on-year growth figure for the first calendar quarter of 2016. And when NBS got around to reporting the quarterly number, its figure was not consistent with the year-on-year one. As Sue Trinh of RBC Capital Markets points out, when you annualize NBS’s 1.1% quarter-on-quarter figure, you get only 4.5% growth for the year.

Yet the story is far worse than Chinese officials embarrassing themselves by reporting irreconcilable numbers. The second explanation for the good first quarter result is that, as the Wall Street Journal noted, the central government simply permitted the creation of “gobs of new debt.”

The surge in lending was stunning. Credit creation during the just-completed quarter was more than twice that in the previous quarter Tim Condon of ING Groep told Bloomberg.

Flooding the economy with easy money permits growth in the short-term, but the tactic is risky because it aggravates the most dangerous of China’s three bubbles. “In our view, China is in the midst of a triple bubble, with the third biggest credit bubble of all time, the largest investment bubble, and the second biggest real estate bubble,” wrote Andrew Garthwaite of Credit Suisse last summer.

Observers are worried that the bulging debt that Beijing has taken on to sustain growth cannot be repaid. China at the end of last year was carrying corporate debt equal to 165% of gross domestic product, and the ratio has obviously deteriorated since then.

And it is also worrisome that the country is now creating obligations about four times faster than it is generating GDP. That just about guarantees a crisis.

Concerns about China’s debt accumulation have existed for years, but seven bond defaults—three by issuers partially owned by the state—since the beginning of the year gripped China’s onshore bond market this month. Bond yields rose, holders dumped junk bonds, and prospective issuers cancelled about $10 billion in bond offerings. A Bloomberg headline earlier this month summed up the situation: “It’s All Suddenly Going Wrong in China’s $3 Trillion Bond Market.”

Time is now the factor. Financial professionals are quietly talking about China’s Minsky moment. In today’s common parlance, that’s the ‘Lehman moment,’ when asset values plunge, borrowers default, and everything falls apart.

Economists and other observers warned that excessive debt would crash the American economy well before that happened in 2008. In China, it’s not clear when things will fall apart, but the conditions for a debt crisis are now in place.

OG Image: Asia PacificChina

Asia PacificChina

Gordon G. Chang's Blog

- Gordon G. Chang's profile

- 52 followers