Gordon G. Chang's Blog, page 4

September 21, 2016

Making Humanitarian Aid Work in North Korea

North Korea is still reeling from what state media is calling the “worst disaster” since 1945.

Floods caused by Typhoon Lionrock at the end of last month have killed 138 at last count. Some 400 are missing, and 68,900 have been left homeless. The UN estimates 600,000 are in need of clean water and other essentials.

The wind and the rain have also split South Korean politicians and raised critical questions about humanitarian relief for horrific regimes.

On Monday, South Korea’s Unification Ministry said, through spokesman Jeong Joon-hee, that Seoul would consider granting aid to the North only if it received a request from Pyongyang and that no such request had been received. Then he said that, even if North Korea asked for aid, it was unlikely the South Korean government would provide it. “God helps those who help themselves,” Jeong added.

Opposition lawmakers were quick to criticize. “We can no longer delay government and civilian support from the humanitarian standpoint,” said Rep. Woo Sang-ho, the floor leader of the main opposition party, Minjoo. “We should separately handle the North Korean authorities and the suffering people.”

Is it possible to separate ordinary North Koreans from their despot? As an initial matter, aid, even if provided in kind, is fungible. That means every won that goes to helping flood victims is one less won that Pyongyang has to spend for that purpose—and one more it can put into developing the world’s most destructive weapons.

Seoul, of course, understands that. Yet the story does not end there. If aid is delivered to people by soldiers or Pyongyang officials, Kim Jong Un’s position is strengthened. It is strengthened because people see their government providing assistance or because the regime boasts that other governments are paying tribute to the Kim leader.

If, however, the aid is delivered to flood victims directly by foreign volunteers, it will undermine the regime’s relentless drumbeat of lies, that, for instance, North Korea is the best society in the world. Kim family rulers know how dangerous exposure to foreigners can be, so over the course of decades they have allowed extremely few aid workers across their borders.

So what can Seoul do? President Park Geun-hye and her government now look hard-hearted, something voters are bound to remember in the next countrywide elections.

Perhaps the president should take a page from Norbert Vollertsen, a German doctor and North Korea aid worker. Don’t cut off aid, he argues. On the contrary, flood the regime with assistance. “Food, medicine, whatever you like, millions and billions of dollars in a huge convoy of trucks, a whole train, in Panmunjom,” he said to me a decade ago, practicing what he would tell the authorities in Pyongyang. “Here, you can get it. Right now. Take it. Nobody has to starve anymore in your country.”

There would be only one catch. In Vollertsen’s plan, journalists would accompany the aid into every home, kindergarten, nursery, and hospital. That would break the regime’s monopoly on information to its subjects, as well as its monopoly on information that reaches us.

If President Park followed his line of thinking, Seoul would take the spotlight off its hard position and put it where it belongs—on Kim Jong Un, who would certainly turn down aid under these conditions. It would then be the regime that looks heartless.

OG Image: Asia PacificKoreaNorth KoreaUNSouth KoreaUN

Asia PacificKoreaNorth KoreaUNSouth KoreaUN

September 19, 2016

US-India, China-Russia Exercises Reflect New Alliances

The US and Indian armies are presently conducting joint exercises in the mountainous state of Uttarakhand, about 100 kilometers from India’s border with China. This is the 12th edition of the Yudh Abhyas drill, and it has never been held in such close proximity to the People’s Republic.

Soldiers often train in regions where conflict is considered most likely to develop. With that in mind, Uttarakhand was not a bad choice. Last July, Chinese troops crossed the border into that state – a border that has been relatively free of such transgressions over the years. Indian defense planners have reason to be alert because the state, which has a 350-kilometer boundary with China, is not far from New Delhi.

Militaries also train with nations with which they expect to ally. As Nitin Gokhale of the Bharat Shakti website, “Indian troops, now across the three services, do more exercises with the United States than with any other country.”

Indian and American officials have issued bland statements about the joint exercise, but Indian commentators have not been subtle. “There is no question of China being the focus, it is only because of geographical features and logistics that the region around Ranikhet was chosen for this long-planned exercise,” said “authoritative sources” to the Sunday Guardian, the New Delhi newspaper.

“With a trilateral joint exercise called Malabar involving Indian, US, and Japanese navies in June this year, India has sent a strong message to China that it would not allow any country to control the South China Sea,” the paper itself warned. “Yudh Abhyas is an extension of the same message of freedom from fear of threat by forces inimical to democracy and forces backing terrorism.

“Forces backing terrorism” is a reference to China, which has supported Pakistani-backed insurgents and terrorists operating on Indian soil. Beijing’s aggressive posture, including frequently sending the People’s Liberation Army across the Indian border, has pushed New Delhi toward Washington. As a result, the two countries are deepening their security ties, and, as Prime Minister Modi said this year, India and the US are shedding the “hesitations of history.”

The shedding process, now roughly two decades in the making, looks complete. Beijing’s recent opposition to India’s membership in the Nuclear Suppliers Group, according to Cleo Paskal of Chatham House, “pretty much killed off any remaining support for China in the Indian establishment.” That she says, has given the Indian defense community the confidence to fully embrace the US.

For its part, Washington has fully embraced New Delhi. India’s new outlook permits Washington, in Paskal’s words, to view that country “as the stable partner it has been looking for in the Indian Ocean—and possibly even in the Indo-Pacific.”

And in the Indo-Pacific, Russia has begun to show enthusiasm for its new partner, China, demonstrating that the Kremlin has joined the other side. Joint Sea 2016, which runs from September 12th to the 19th, is a particularly provocative China-Russia drill. According to Chinese state media, the two navies will conduct “island-seizing” missions in the South China Sea.

This exercise is the fifth China-Russia naval drills since 2012. The two militaries, on land and sea, now regularly train with each other, and Moscow and Beijing are coordinating their Asia policies, even on China’s sea claims.

Beijing often complains about America’s “lingering Cold-War mentality.” At the end of that multi-decade struggle, China and the US stood against the Soviet Union and India.

Today, the great powers have realigned. And fortunately for the region—and the world—two great democracies are finally working together.

OG Image: Asia PacificEurope and Central AsiaNorth AmericaSouth AsiaIndiaUSChinaRussiaSouth KoreaKoreaVietnamNorth KoreaMilitaryVietnam

Asia PacificEurope and Central AsiaNorth AmericaSouth AsiaIndiaUSChinaRussiaSouth KoreaKoreaVietnamNorth KoreaMilitaryVietnam

September 7, 2016

India and Vietnam Unite Against China

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi met his Vietnamese counterpart, Nguyen Xuan Phuc, in Hanoi Saturday to discuss their countries’ deepening relationship and sign various agreements. The word “China” rarely passed their lips in public, but that was the topic dominating the get-together.

Beijing was able to scrub the formal agenda for the G20 of controversial geopolitical issues, like the South China Sea, but that did not mean regional leaders stopped talking about them privately. Modi, before proceeding to host city Hangzhou, stopped off in the Vietnamese capital to discuss the worsening situation in East Asia.

In Hanoi, Modi and Phuc witnessed the signing of 12 bilateral agreements, including one for the sale of Indian-built fast patrol boats to Vietnam, which paid for the craft with a $100 million line of credit New Delhi had previously extended. And for the purpose of “facilitating deeper defense cooperation,” Modi provided another $500 million credit line. The two leaders also issued a joint statement on various issues, most notably freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.

The most significant aspect to the meeting was symbolic. Modi and Phuc declared that India and Vietnam’s strategic partnership, first, announced in 2007, has been upgraded to a “comprehensive” one.

Until then, Vietnam had only two “comprehensive strategic partnerships,” one with China and the other with Russia, but those two special relationships are now in doubt. In addition to its stepped up bullying of Vietnam, China now poses a serious threat to Vietnam’s security and sovereignty by demanding territory and water that Hanoi claims as its own. Russia’s relationship with Vietnam is now an open question because of its growing alignment with Beijing. New Delhi, therefore, looks like Hanoi’s most reliable partner—and counterweight—in the region.

For nations bordering the South China and East China seas, India, of all the countries nearby, has become the security provider of choice. It has the heft to oppose Chinese expansionism but no territorial claims there. It is a democratic state and works hard to maintain good relations, even with Pakistan, which has harbored anti-India militants.

No wonder Vietnam, Japan, Singapore, Australia, the Philippines, and the US have all worked steadily this decade to involve India in the affairs of the troubled region.

Nor has it escaped New Delhi that it has a stake in what happens in East Asian waters. India’s eastern islands are only about 90 miles from the western approach to the Strait of Malacca, and the South China Sea connects the two great oceans on which India increasingly depends for its prosperity. India is separated from the rest of Asia by the Himalayas, so Indian businesses are especially dependent on sea-borne commerce. About 55 percent of its trade, for instance, crosses the South China Sea.

That makes New Delhi interested in what happens in that crucial body of water. “China’s consolidation of power in the South China Sea will have a direct bearing on India’s interests in its own maritime backyard, the Indian Ocean,” Brahma Chellaney, the noted New Delhi-based author and analyst, told me last year. “In fact, China’s quiet maneuvering in the Indian Ocean, where it is chipping away at India’s natural geographic advantage, draws strength from its more assertive push for dominance in the South China Sea.” So, as he notes, “If China gets its way in the South China Sea, it will become far more assertive against its other neighbors, including India.”

New Delhi understands its interests are affected by events far from its borders, which explains why Modi is the first Indian prime minister to travel to Vietnam in 15 years—and why he isn’t shy about developing and announcing India’s comprehensive strategic partnership with Vietnam.

OG Image: South AsiaIndiaVietnamChinaVietnamModiPrime MinisterNarendra Modi

South AsiaIndiaVietnamChinaVietnamModiPrime MinisterNarendra Modi

August 31, 2016

Is the Chinese Military Stirring Conflict in South Asia?

The killing of Burhan Wani, a young militant, on July 8 by security forces has triggered the worst crisis in Indian-controlled Kashmir in a generation. The continuing disturbances—they’ve been collectively called the “Second ‘Intifada”—not only threaten relations between New Delhi and Islamabad but also could draw Beijing into deeper involvement in South Asia.

Kashmir, in ways not evident at this moment, might affect ties between the world’s two most populous states.

China and India are not destined to be adversaries. Madhav Nalapat, the influential Indian thinker at Manipal University, believes they can develop an enduring relationship because Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping look like they share that goal.

Yet before the two capitals can stabilize ties, Nalapat believes, China’s leader has to first overcome a faction in his People’s Liberation Army that wants to inflame troubled Kashmir. That faction supports like-minded Pakistani hardliners who have used that disputed territory to keep New Delhi off balance. “The hope is that those loyal to Xi will move to reduce the hold of PLA hawks over foreign policy relating to India,” writes Nalapat in a mid-August piece in the Sunday Guardian, the New Delhi newspaper.

The hawks with their allies in Beijing, the scholar maintains, are “backing the generals in Pakistan in their drive to generate a crisis with India that would shift global attention from East and South-East Asia back to South Asia, preferably through a limited conflict over Kashmir.”

India and Pakistan, cut from the same country in 1947, have, in addition to numerous skirmishes, fought two of their three wars over Kashmir since then.

Nalapat’s argument involving PLA hawks suggests that Xi Jinping is not in total command of the Chinese military. If he were in charge, for instance, it would be unlikely that a group of generals would be bold enough to run its own India policy, especially one that directly undermined Xi’s.

There is reason to support Nalapat’s theory. For example, Chinese soldiers embarrassed Premier Li Keqiang just before his May 2013 visit to India by conducting a deep incursion into Indian-controlled territory in Ladakh, high in the Himalayas and a part of what is called Jammu and Kashmir. As the Wall Street Journal noted at the time, there was evidence to suggest the provocation was “unsanctioned,” the work of local commanders acting independently and on their own initiative.

Indeed, there is good reason to believe that the September 2014 Chinese incursions into Indian-controlled territory in Eastern Ladakh, were not authorized by Xi Jinping, who was visiting India at the time. The Chinese leader was embarrassed by the provocations, which made him look weak or duplicitous. You can take your pick, but I chose the former. Considering all the circumstances, Xi was likely telling the truth when he told Modi that he was not responsible for the incursions.

And the Chinese military now seems to be dialing up the belligerence again. Nalapat in the Sunday Guardian points to current Chinese incursions not far from New Delhi, in Uttarakhand. Uttarakhand had, up to now, “been relatively free of such incidents.” “PLA hawks,” he writes, “have, over the past year, increased their level of cooperation with the Pakistan army, including in ways that pose a direct challenge to India’s interests.”

The evidence is murky, but it appears that China’s military—or at least a part of it—does have considerable latitude to implement its own policy when it comes to Pakistan and India, which means that Chinese generals, working with their Pakistani counterparts, may help prolong the ongoing protests in Kashmir.

Nalapat reports “the Pakistan army is secretly gearing up to fight a limited war in the Kashmir theater.” If that proves to be true, the next conflict there could end up a big-power struggle with India on one side and China, in some fashion, on the other.

OG Image: Asia PacificSouth Asia

Asia PacificSouth Asia

August 23, 2016

How Do We Deal With a Self-Isolating China?

“It’s on China not to be isolated,” said Admiral Harry Harris to David Feith of the Wall Street Journal in an interview published this month. “It’s on them to conduct themselves in ways that aren’t threatening, that aren’t bullying, that aren’t heavy-handed with smaller countries.”

The chief of US Pacific Command is correct, of course. His comment, the WSJ noted, “raises a basic question.” As the paper asks, “At what point is it prudent to conclude that China is committed to the path of bullying and revanchism?”

As early as the beginning of the decade, Beijing has engaged in a series of hostile acts that, with abbreviated time-outs, has continued to this day. Even if one argues that China’s commitment to provocative conduct occurred later or has yet to be made, the country is roiling its periphery at this moment, most notably in the South China Sea and East China Sea.

Washington has not openly confronted the Chinese, presumably to give Beijing leaders a graceful way to move away from provocative policies. Admiral Harris, for instance, says that unsafe Chinese intercepts of American aircraft in international airspace were the result of “poor airmanship, not some signal from Chinese leadership to do something unsafe in the air.”

Reckless contact has also occurred on the surface of international waters. Beijing has declined to apply the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea, which both the Chinese and American navies signed in 2014, to coast guard and law enforcement vessels. Beijing uses these craft as well as fishing trawlers for aggressive conduct off the shorelines of its neighbors.

Pacific Command is exceedingly diplomatic about these situations as well. “We recognize that there’s a gap there,” Harris told Feith, referring to the Code. “We shouldn’t discount the positives because there are still negatives. We should embrace the positives, continue to work on them, and then work on the negatives.”

Harris’s approach sounds reasonable, but Beijing’s conduct has generally become more troubling over time. In recent weeks, it has surrounded both Scarborough Shoal, which is close to the main Philippine island of Luzon, and the islets the Japanese call the Senkakus in the East China Sea with hundreds of fishing trawlers and large coast guard vessels. Tokyo this week released a video of Chinese craft in its waters.

The challenge for Harris—and more generally for the US—is to defuse situations before incidents occur. Beijing, unfortunately, appears to be signaling one is coming soon. An anonymous source speaking to the South China Morning Post said China might begin reclamation of Scarborough Shoal, sometime after the upcoming G20 meeting in Hangzhou the first week of next month and before the US election.

Reclamation of that feature, which would be preceded by surrounding the shoal with Chinese vessels, would be an inflection point. By pouring concrete over coral, Beijing would be securing its possession of Scarborough. It seized the shoal from Manila in early 2012 by preventing Philippine vessels from approaching the area.

President Obama reportedly warned the Chinese in March that there would be serious consequences for trying to reclaim Scarborough, “a stark admonition” as the Financial Times put it.

Imposing consequences of that sort would surely come as a surprise to the Chinese because Washington, over the course of decades, has been reluctant to exact costs for dangerous conduct, including encounters on and over international water. Consequently, Beijing might now feel safe to ignore American warnings, no matter how earnestly delivered or sincerely intended.

And that brings us back to Admiral Harris. He and his predecessors at Pacific Command, following the lead of Washington policymakers, have tried to moderate China’s conduct through engagement of its military. “We don’t want China to be isolated,” Harris told Feith. “Isolation is a bad place to be.” Yes, isolation is, as the admiral termed it, “dangerous,” but in the long run so is failure to hold Beijing accountable for acts of aggression, large and small.

Soon, perhaps just after the G20, the world will discover if years of Washington’s—and the US Navy’s—patient bridge-building diplomacy has moderated China’s challenge to its neighbors and the international system that America defends.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaPhilippinesUnited States

Asia PacificChinaPhilippinesUnited States

August 16, 2016

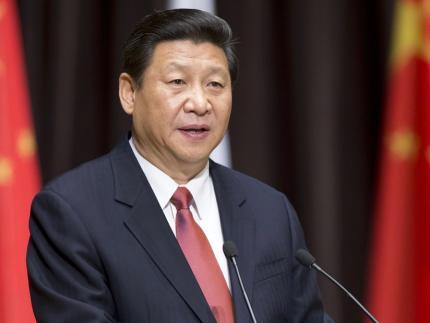

Xi Jinping Purge of Military Brass Continues

Two former Chinese generals were taken into custody in recent weeks, according to a report that appeared in the South China Morning Post. The detentions look to be in connection with General Secretary Xi Jinping’s campaign to clean house in the Communist Party’s sprawling People’s Liberation Army.

According to “a source close to the military,” former Generals Li Jinai and Liao Xilong were escorted out of meeting of retired senior cadres in July by “PLA disciplinary officers.” The report states the two generals, who both retired in the first part of 2013, were detained for possible “violations of party discipline,” the ruling organization’s code for corruption.

The Post notes the possibility that the two former officers were not targets of an investigation but were merely assisting in the investigation of others, but that benign explanation is implausible. Both served on the party’s Central Military Commission, the body that controls the military, and would not likely be subject to such humiliating treatment unless they were suspected of venality. Indeed, Liao is considered a “war hero” for fighting the Vietnamese decades ago.

The detentions of Li and Liao follow the downfall of General Xu Caihou and the imprisonment of Guo Boxiong, both former vice-chairmen of the Central Military Commission.

Xu died from bladder cancer last year while in custody. Guo received a life sentence late last month, making him the most senior flag officer to be imprisoned for corruption in the history of the People’s Republic.

Virtually nobody thought that Xi would rest after bringing down Xu and Guo. As the South China Morning Post reported, “various sources” indicated there would be additional detentions when state media announced in early July that General Tian Xiusi, the former political commissar of the air force, had been “placed under investigation.” The troubles of Li and Liao strongly suggest Xi Jinping’s probes and purges continue.

Let there be no doubt that the PLA is one of the most corrupt institutions in China, and Xi, following the example of his predecessors, is using the venality of opponents as a way to sideline those opposed to or inconvenient to his ambitions. In the military, that opposition is centered on flag officers appointed by his two predecessors, Jiang Zemin, the ailing head of the party’s Shanghai Gang faction, and Hu Jintao, the chief of the Communist Youth League faction. Xi’s choice of targets suggests that his law-enforcement efforts are motivated at least in part by his seemingly relentless attempts to accumulate power.

While Xi has been conducting what amounts to a political purge, he has sponsored one of the most sweeping reorganizations of the People’s Liberation Army, regrouping seven military regions into five theater commands among other changes. The streamlining of command and control, announced early February, has sidelined—and will continue to sideline—whole groups of officers as the changes are implemented in the coming years.

At the moment, Xi appears to have the upper hand over the flag officers, as is evident from the disgrace of General Xu, the imprisonment of General Bao, and the numerous detentions of senior retired and active-duty military officers this year. The dominant view is that Xi has the army under control, but that assessment seems premature. Were that true, there would be no need for Xi to continue the jailings. The apparent confinement of Generals Li and Liao last month, therefore, suggests Xi is still not in complete command of the upper reaches of the PLA.

How strong is the opposition to Xi? Willy Lam of the Chinese University of Hong Kong tells World Affairs that “the resistance is under the table.” My sense is that many generals and admirals are waiting for Xi to falter, and if the opportunity presents itself, they will strike back.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaXi JinpingChina MilitaryarmyCCPMilitary

Asia PacificChinaXi JinpingChina MilitaryarmyCCPMilitary

August 5, 2016

China's Coming Population Crisis: Guns vs. Canes

“It completely baffles me why they are pushing for taking all those islands now,” a friend wrote to me late last month, referring to Chinese adventurism in the South China Sea.

China’s provocations are frequently attributed to President Xi Jinping’s nationalism, and another reason, almost always ignored, is the ascendance of the People’s Liberation Army in Beijing policymaking circles. Howard French, former bureau chief of the New York Times in Shanghai, suggests another often overlooked factor fueling Beijing’s expansionist impulse—China’s accelerated demographic decline.

China faces a “population crisis.” This term is usually used in the context of exploding birthrates. China’s crisis, however, is the opposite. For almost four decades, Beijing rigorously enforced a “one-child policy.” Now, it’s a “two-child” world in China, but the change came much too late. Even if the Communist Party scrapped all birth restrictions today—not possible because that would be an admission of “one of history’s great blunders” the country would still be facing a sharp fall-off.

Toward the end of last decade, for instance, Beijing’s official demographers expected the workforce to peak this year. In fact, the highpoint came in 2011. Those demographers now expect the country’s population to reach its highest mark in 2028, but a leading Chinese official publicly said that might happen in 2020.

So what does all this have to do with Chinese aggression in its peripheral seas? “This is the moment to go for the ring, if you will, to try to secure every gain that you can, before the huge costs come home,” remarked French to PBS’s Judy Woodruff this month. He was referring to what he called “the biggest aging crisis that the world has ever seen.” “And, therefore we’re seeing China push very hard in its immediate neighborhood, particularly in the maritime zone surrounding China, to kind of create a security zone for itself, trying to lock in the territorial and maritime gains that it can now, before a period of much more difficult choices arises some time in the 2020s.”

French believes that Beijing will soon have to choose not between guns and butter, but between guns and “canes.” He points out the party has been increasing the PLA’s budget by about 11 percent a year since the 1991 Gulf War, but there is “no way that China will be able to sustain that sort of military expenditure.” Why? “The most important reason is because of its population changes.”

China faces a closing window of strategic opportunity. Its horizons are limited by grim demographic prospects, a slowing economy, a fracturing political system, and an environment that has nearly reached the limits of exploitation.

A half-decade ago, many argued that Chinese belligerence was the product of overconfidence, a consequence of the global financial crisis of 2008. Now, after suffering foreign policy setbacks during the last two years—the latest being last month’s unfavorable Hague ruling on the South China Sea—Beijing’s moves could be, as French suggests, the result of leaders thinking that they must move fast while they still can.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaPopulationSouth China Sea DisputesMaritime DisputesChina Military

Asia PacificChinaPopulationSouth China Sea DisputesMaritime DisputesChina Military

July 29, 2016

The End of World’s Rules-Based Order?

On Wednesday, Secretary of State John Kerry, standing next to Perfecto Yasay, his Philippine counterpart, gave strong rhetorical support to the effort by Manila to negotiate with China over their sovereignty and other disputes.

Kerry’s words followed Monday’s statement issued by Australia, Japan, and the US calling for compliance with the July 12 award of the arbitral panel in The Hague on the South China Sea in Philippines vs. China. The ruling, now known in China as the “7.12 Incident,” essentially invalidated Beijing’s “nine-dash line” claim to approximately 85 percent of that vital body of water.

The three-country statement was issued on the sidelines of a meeting in Vientiane, Laos of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. ASEAN’s statement, in contrast, was far weaker. Cambodia, at the behest of Beijing and with the assistance of Laos, was able to block an attempt by Manila and Hanoi to have the 10-nation grouping formally endorse the enforcement of the panel’s decision.

Beijing’s initial reaction to the July 12 award, which interpreted the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, was all bluster and belligerence, but China may now be moving toward a softer line. For instance, it agreed with ASEAN not to settle uninhabited features and it appears in the last few days to have dropped “nine-dash line” from its vocabulary.

Beijing also agreed to negotiations with the Philippines, yet that was not a sign of flexibility. China said it would begin talking only if Manila agreed to ignore the arbitral award as the basis for discussions, and the Filipinos, understandably, rejected that condition.

While meeting with his Chinese counterpart earlier in the week, Kerry spoke as if he was taking China’s side. His statements in Manila, fortunately, clarified the American position. “We are consistently, year after year, urging parties to negotiate, to work this through diplomatically, bilaterally, multilaterally, build up confidence-building measures,” Kerry said Wednesday. “And when we say that we urge a negotiation, we do so obviously understanding that our friend and ally, the Philippines, can only do so on terms that are acceptable to the Government of the Philippines.”

The broader question is why should there be negotiations in the first place. If the Philippines makes concessions, which most expect if talks occur, it will undercut a rules-based international system. After all, the arbitral panel in The Hague has issued its award and at the moment nobody seems to be doing much to enforce it. As William Choong of the International Institute for Strategic Studies in Singapore told the Wall Street Journal, “What we have is essentially a holding pattern between China, the Philippines, and the U.S.”

What is the point of having an award or even a UN convention if no one holds China to account? So far, Beijing has been allowed to sign agreements, take the benefits of provisions it likes, and ignore what it does not. Now, the US appears to have adopted the position that the Hague award, instead of being enforced, can be negotiated.

And this raises a still-larger issue. During the ongoing American presidential campaign, Donald Trump boldly suggested that the US walk away from multinational groupings like the World Trade Organization and break agreements. Many observers—me included—think that is a horrible idea, yet defenders of multilateralism and a rules-based order should not be surprised if these organizations do not now survive.

China has gamed the world. Its decision to ignore the July 12 award is striking, and now nations seem to be bending, fearful of Beijing’s reaction to attempts to enforce international law. That is not the basis of a sound international system.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaAsia PacificSouth China Sea DisputesMaritime DisputesRegional ForceSouth China Sea

Asia PacificChinaAsia PacificSouth China Sea DisputesMaritime DisputesRegional ForceSouth China Sea

July 20, 2016

China Defiant in Wake of Int'l Ruling on South China Sea

On the 12th of this month, an arbitral panel in The Hague rendered its award in the landmark case of Philippines vs. China. The decision, interpreting the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, was a sweeping rebuke of Beijing’s position, invalidating its expansive “nine-dash line” claim to about 85 percent of the South China Sea.

Many are hoping that China will bring its claims into line with UNCLOS, as the UN pact is known, and some even think it has actually begun the process of doing so. Unfortunately, a series of hostile reactions in the last few days, including an implied threat to use nuclear weapons to defend its outposts in that body of water, suggest Beijing’s reaction will not be benign.

China maintains it has sovereignty to all the features—islands, rocks, and low-tide elevations—inside its now-famous dotted boundary. Five other states—Brunei, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam—also claim those features, and China’s nine-dash line impinges on the exclusive economic zone of a sixth, Indonesia.

Despite China’s expansive claims, Andrew Chubb, a Ph.D candidate at the University of Western Australia, has published a widely circulated article suggesting China will eventually accept the view of international law embodied in the ruling. He points to a central government statement issued on July 12th, which Chubb says “contained welcome hints that China may be subtly, and under cover of a strong stance on its South China Sea territorial sovereignty, bringing its South China Sea maritime rights claims into line with UNCLOS.”

Despite Chubb’s optimistic analysis, Beijing’s response has been disheartening. “The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China solemnly declares that the award is null and void and has no binding force,” declared a statement issued just moments after the issuance of the ruling. “China neither accepts nor recognizes it.” Beijing’s reaction to the ruling has been accurately characterized as “non-acceptance, non-compliance, and non-implementation.”

Yet China’s rejection of the arbitral award has gone beyond the rhetorical hard line. In blatant defiance of the terms of the ruling, Beijing has again blocked Philippine fishing boats from reaching Scarborough Shoal, which China seized in early 2012, and it has sent its own fishing craft into what appears to be the exclusive economic zones of other countries.

In the wake of the Hague ruling, Beijing also walled off part of the South China Sea for a three-day naval drill beginning on the 19th.

Furthermore, China’s navy gave an unpleasant reception to Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, who arrived in China for three days of talks on the 17th. On the day before Richardson landed, one of China’s top admirals, Sun Jianguo, stated that American freedom of navigation exercises could result “in disaster.” And then Richardson’s counterpart, Admiral Wu Shengli, told him on the 18th that China will resume the controversial reclamation of the Nansha Islands, the Spratlys.

Not to be outdone, the Chinese Air Force issued a thinly veiled and ominous threat. Two days after the award in The Hague, it released a photograph of a nuclear-capable H-6K bomber flying over contested Scarborough. Given the timing of the release, it is likely that the Chinese military intended to issue a warning of a dire sort.

Finally, further inflaming the situation, Beijing early this week said it was beginning, on a regular basis, "combat patrols" over the South China Sea "with strategic bombers, interceptor jets, reconnaissance planes, and refueling aircraft."

Of course, it’s possible that Beijing’s primary audience for the muscle-flexing is domestic. Yet, China’s blustering defiance of the international arbitration ruling and the process itself is a further warning to the international community that China is a rogue determined to play by its own rules.

For decades, the international community had hoped that China would enmesh itself in the world’s laws, rules, resolutions, treaties, and norms. When given a chance to do so, Beijing instead moved its brand-new military into the field.

OG Image: Asia PacificChina

Asia PacificChina

July 13, 2016

Asia Divisions Deepen after South Korean Missile Defense Deployment

On Friday, Seoul’s Defense Ministry and the US Defense Department announced their joint decision to deploy the Terminal High Altitude Air Defense system in South Korea. The first battery will be placed to protect American forces on the peninsula against a North Korean missile attack.

China reacted within hours, lodging protests with both South Korea and the US. Then on Monday the Chinese foreign ministry continued its tantrum, threatening, in the words of spokesman Lu Kang, to impose “relevant measures” against South Korea.

South Korea’s deployment of THAAD, as the Lockheed Martin-built system is known, is a setback for Chinese attempts to move Seoul away from Washington and marks an end of President Park Geun-hye’s moves to entice China to abandon North Korea.

These two failed initiatives will have long-lasting consequences. The most important of them looks like a division of North Asia into two camps, one centered on China and the other on the US. In short, Asia is beginning to break down into groupings last seen during the Cold War.

China, in many ways, is a driver of this process. Beijing, Bonnie Glaser of the Center for Strategic and International Studies says, “miscalculated” in its attempts to prevent South Korea from agreeing to deploy THAAD. The Chinese, returning to the thinking of the tributary era, thought they had power over the South Koreans and attempted to intimidate them, badly overreaching.

But Beijing does not appear to be pulling back after its setback. Instead, the Chinese look like they are attempting to punish the South by increasing cooperation with its mortal enemy, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. As Cai Jian of Shanghai’s Fudan University predicts, “Beijing’s relationship with Pyongyang will get better.”

And as Lee Jung-nam of Korea University notes, China might ease sanctions on the North. Moreover, Lee thinks South Korea will have a harder time getting Beijing’s cooperation.

The changes are so momentous that Lee believes there could be a “new Cold War” with China, Russia, and North Korea on one side and the US, South Korea, and Japan on the other.

At one time, South Korea thought it might be able to avoid taking sides and play the crucial swing role in North Asia. President Roh Moo-hyun, playing to his young constituency, once offered to “mediate” between Washington and Pyongyang as if his nation were a neutral bystander.

In 2005, he wanted South Korea to develop a “balancing role,” switching sides on an issue-by-issue basis between the “northern alliance” of Beijing, Moscow, and Pyongyang and the “southern alliance” of Washington and Tokyo. “The power equation in Northeast Asia will change, depending on the choices we make,” he said, with more than a touch of the confidence evident in Seoul at the time.

Beijing, if it still retained its once-deft touch, would encourage Seoul, even after it agreed to the THAAD deployment, to aspire to the balancer role. But Chinese foreign policy has become increasingly hard-headed in this decade, and China seems destined to push South Korea more firmly into its alliance with Washington.

America’s best diplomatic weapon in Asia is China, because by being so aggressive Beijing makes it easy for Washington to maintain strong ties there. Chinese policymakers must recognize this reality, yet they have maintained their course and may well double down. That, among other things, should be a cause for alarm in capitals in the region and elsewhere.

OG Image: Asia PacificAsia

Asia PacificAsia

Gordon G. Chang's Blog

- Gordon G. Chang's profile

- 52 followers