Don M. Winn's Blog, page 28

January 16, 2014

The Power of Story Part One—Learning From Haitian Youths

Haiti, one of the poorest nations in the Western Hemisphere, is a place that understands the power of story. In a country marked by food shortages, irregular or nonexistent electricity, almost no medical care, and no money for schools or school supplies, Haitian youths display a tremendous amount of resilience.

Haiti, one of the poorest nations in the Western Hemisphere, is a place that understands the power of story. In a country marked by food shortages, irregular or nonexistent electricity, almost no medical care, and no money for schools or school supplies, Haitian youths display a tremendous amount of resilience.

The University of Illinois recently completed a study examining the cultural identity and well-being of adolescents in the Caribbean. In spite of the fact that the majority of Haitian youths deal with the daily effects of poverty, they have a very impressive lesson to teach us.

Researchers measured the strength of family obligations and cultural orientation among early adolescents aged 10 to 14 years in rural Haiti. The findings show that Haitian teens, especially boys, believe very strongly that they should respect and obey their parents and assist them when they need help without being paid for it.

University of Illinois professor of human development and family studies, Gail Ferguson, remarks: “Can you imagine how helpful that would be for a family with few resources? That attitude in itself contributes to a close parent child relationship, which is a positive factor in adolescent development.”

She continues: “These teens report having a strong sense of family obligation and an attachment to Haitian culture, which probably protects them and contributes to their resilience.”(Haitian youths displayed an affinity for their culture that was nearly three times as high as that of American youths.)

But what do these findings have to do with stories? Plenty.

“Haitian culture is known for its creativity and it’s close community bonds. The arts, particularly visual arts and a love of story, provide an emotional outlet for Haitian youth, helping to channel their emotions, desires, and needs.”

Our stories link us to our ancestors, our families, our place of birth, our culture, our emotions, and our past, present, and future. They teach us values, morals, and object lessons. Stories anchor us to a place of belonging and expand our horizons toward new vistas and opportunities. They help us understand who we are, where we came from, what’s important in life, and indeed what life is all about. Each family has a story, as does each culture.

What these young people teach us is that it’s much more important to be rich in family ties, to be part of our own story, and to be rooted in our own culture and identity than it is to have the trappings of success that are oh-so-important in our part of the world.

What stories do we share with our children? Do we recognize what a tremendous impact stories have on our youth today? In a world that is inundated with narrative in the forms of television, movies, gaming, news, and media, it can be easy to forget the importance of handing down family stories, histories, and anecdotes. Do we take the time to make sure our children know their own personal stories?

January 9, 2014

Susannah Cord on Horse and Human Interaction

As I’m working on my children’s novel with a medieval setting, I needed to learn something about horse/human interaction, because horses were used so extensively in medieval society. I don’t have a lot of personal experience with horses, so I called on expert Susannah Cord, who graciously responded to my cry for help. Here’s some of what she had to say:

How do horses communicate with humans?

Horses communicate most obviously through body language. It can include the way they hold their head, their body, the expression of their ears and eyes, or how they move in your presence. They may also communicate by offering a body part for scratching, pinning their ears if a saddle hurts, swishing their tail if tense or trying very hard to do what you ask, or even holding a part of their body away from you if it hurts them.

I have also found that horses are adept at transmitting mental images and even emotions that just kind of pop into your head and heart as you work with them. Either you are open to this and respond as best you can, or you are not and miss out on the whole thing! It all comes down to our perception and our own needs, what we allow ourselves to hear and experience.

In my book The Knighting of Sir Kaye, Kaye’s horse Kadar is extremely intuitive and very protective towards Kaye. Does this have a basis in reality?

Yes. Horses have to be extremely intuitive and protective. We may not think of them this way, but horses in the wild are prey animals, and in order to protect themselves, they are constantly scanning their surroundings even when they appear very relaxed and peaceful. They need to be able to make fast decisions — like deciding whether some nearby wolves are just passing through or if they’re on the hunt. Their lives and the lives of their family and friends depend upon them trusting their slightest impulses.

This intuitiveness carries through into their interactions with humans. Horses are expert body language readers and are exceedingly sensitive to a person’s emotional and energetic state, which they tend to reflect back to the person. Another example of intuitiveness I’ve seen is when I work with a horse, and they tell me when something is about to happen before I ever know it. I’ve also had horses react to outside influences causing me to begin to fall off only to have them swivel and catch me just in time, then stop and stand dead still while I clamber back into a sitting position. If they consider that you are part of their circle — if they care for you — they will look out for you.

This intuitiveness carries through into their interactions with humans. Horses are expert body language readers and are exceedingly sensitive to a person’s emotional and energetic state, which they tend to reflect back to the person. Another example of intuitiveness I’ve seen is when I work with a horse, and they tell me when something is about to happen before I ever know it. I’ve also had horses react to outside influences causing me to begin to fall off only to have them swivel and catch me just in time, then stop and stand dead still while I clamber back into a sitting position. If they consider that you are part of their circle — if they care for you — they will look out for you.

To me, this protectiveness they can extend to humans really demonstrates how wonderful and flexible horses are. To a horse, we humans have all the marks and smells of a predator, and on top of all that, we want to get on their backs. This is something only a predator with killing in mind would want, and yet horses allow us to do this. They even include us in their circles and allow us to become their friends and leaders.

Why would a human be a horse’s leader?

Why would a human be a horse’s leader?

In a herd of horses, one is always the leader. He stands guard, alert and attentive, and the other horses look to that horse for clues as to what they should be doing. And so, outside of the herd, the first question a horse asks you is “Are you the leader or am I the leader?” He needs to know this down to his very bones, because his instincts tell him his life depends upon it. If he is the leader, then he needs to look out for himself 100% of the time. He has to make his own decisions as to how to stay alive, never mind what you are doing. But if he trusts that you are the leader, he can relax and take his cues from you.

One of you has to be in charge and if you understand that in the presence of a large animal your physical well-being depends upon it being you, you will learn how to be in charge. The horse will thank you for it if you do it right, because horses in a herd live in a hierarchy; their social structure and psychology adheres to a dictate of hierarchy.

One of you has to be in charge and if you understand that in the presence of a large animal your physical well-being depends upon it being you, you will learn how to be in charge. The horse will thank you for it if you do it right, because horses in a herd live in a hierarchy; their social structure and psychology adheres to a dictate of hierarchy.

It can be such a relief for the horse if he can just let you make the decisions and create a safe space for him in your presence because a horse also knows that preserving energy is smart, in case he has to outrun a pack of wolves or a puma. Most horses are completely fine with someone else being in charge — as long as they can trust that you are a good leader. Horses have a very strong sense of fairness. They understand and accept discipline, but they also know when someone is being unfair and abusive.

So I try to be a fair, benevolent, and affectionate leader for my horses. I have to understand that the horse did not ask to be here, to work for me, so I have to make it a worthwhile, enriching experience for him so he will start to look for me, to ask for me. I have to show up day after day to work and just be with the horse, because even if I bought the horse’s body, I still have to work to earn his heart.

A horse’s heart is worth winning! They are so much smarter, kinder, funnier, and more generous than people give them credit for. They are incredibly patient and forgiving (to a point) and are highly intelligent, feeling creatures with a latitude of heart unknown in our own species, but to be their friend you must first be their leader. They cannot be your pet, like a dog or cat. Many people today come to horses all misty-eyed, remembering reading My Friend Flicka and thinking it will be like having a really big dog. Reality Check! Horses are not like dogs!

A horse’s heart is worth winning! They are so much smarter, kinder, funnier, and more generous than people give them credit for. They are incredibly patient and forgiving (to a point) and are highly intelligent, feeling creatures with a latitude of heart unknown in our own species, but to be their friend you must first be their leader. They cannot be your pet, like a dog or cat. Many people today come to horses all misty-eyed, remembering reading My Friend Flicka and thinking it will be like having a really big dog. Reality Check! Horses are not like dogs!

Here’s why: dogs, cats, and humans are all predatory species. This means we share psychological traits that we are not even aware of that make it relatively easy to keep them as pets. We possess by nature an innate understanding of each other. Whether we like it or not, a human can be vegan and a pacifist and always be kind to animals, but a prey animal will still instinctively recognize that human as a predator.

Horses, as prey animals, have a need for safety, trust and leadership that is far more profound than that of a cat or dog. Can we be ‘friends’ with horses? Absolutely, once leadership is in place. Then, as your relationship develops, you may begin to share that responsibility to such a degree that every moment becomes a real conversation, a dance where you are the ‘leading man,’ and you both almost forget who is in charge because you are so simpatico. However, there must always be a leader and you are it, because the horse needs that to feel safe.

And then the stories can become true for you – Flicka, Black Stallion, Black Beauty, and so on. But first you have to pay your dues and earn a horse’s trust and respect. You have to show up and make it worthwhile for them to pay attention to you.

Horses are the ultimate ego and narcissism buster!

About Susannah Cord Susannah Cord was raised in Denmark, Kenya and Zimbabwe. Susannah is a lifelong horsewoman, writer and now wildlife photographer-in-training currently living in the USA. She was a longtime contributor to online global publication, Horses For LIFE Magazine, where her long running column, Riding By Torchlight, was a favorite with readers. Susannah is also the author of illustrated children’s book, Fenella, A Fable of a Fairy Afraid to Fly and the blog The Torchlight Chronicles where she writes about life, horses and everything in between. Her new book, the story of the horseback safari with Offbeat Safaris in Kenya that changed her life, will be out in 2014.

Susannah Cord was raised in Denmark, Kenya and Zimbabwe. Susannah is a lifelong horsewoman, writer and now wildlife photographer-in-training currently living in the USA. She was a longtime contributor to online global publication, Horses For LIFE Magazine, where her long running column, Riding By Torchlight, was a favorite with readers. Susannah is also the author of illustrated children’s book, Fenella, A Fable of a Fairy Afraid to Fly and the blog The Torchlight Chronicles where she writes about life, horses and everything in between. Her new book, the story of the horseback safari with Offbeat Safaris in Kenya that changed her life, will be out in 2014.

As a devoted dressage rider and trainer, Susannah on occasion rides for the Foundation for Classical Horsemanship.

Websites:

www.SusannahCord.com

www.FenellaTheFairy.com

www.OffbeatSafaris.com

www.thetorchlightchronicles.blogspot.com

www.FoundationforClassicalHorsemanship.org

January 2, 2014

Medieval Horses

If I asked for a show of hands from all of you out there who couldn’t wait to get your driver’s license as a teenager, I’m guessing that most of you reading this blog would have your hands up. Today, getting their driver’s license and better yet, their own car, is rite of passage for many youths.

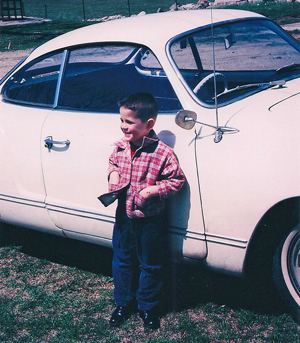

Me as a kid in front of my dad’s Karmann Ghia.

When I was a young teenager I would check out all the latest sports car ads and wander by the auto showrooms wondering what it would be like to drive my own sports car. I liked the Mustang, and I always had a soft spot for the Karmann Ghia because my dad used to drive them. But eventually I had to lower my expectations to a somewhat more reasonable level. My first car was a 1967 Impala for which I paid— actually overpaid— $500.00. The car had a million problems, including a horn that would spontaneously blare to life with a teeth-shattering blast at the most inconvenient times— when I was stuck in line at the bank, when I was driving behind a police car… I’m sure you get the picture.

But what about transportation and youthful rites of passage from a time long before the automobile? What about from medieval times? In general, walking was the main method of getting from point A to point B. But depending on your status and financial means, you might have used a mule or a donkey or perhaps even oxen— both for transportation and for other types of work like plowing. But if you wanted to travel in class, well then the horse (of course) was the preferred method of getting around— the sports car of its time.

Today, horses are differentiated by their breed, but for much of the early middle ages, very few pedigrees were written down. Instead, horses were distinguished by how they were used. Here are a few kinds of horses common in the middle ages:

The destrier was a strong, sturdy, powerful horse, known for its great size (although it was likely smaller than many modern horses). It was very expensive, but prized by knights because it was well-known for its abilities in battle as well as being suitable for the joust.

The courser (or charger) was often used in battle because it was light, fast and strong. Sometimes they were used for hunting as well.

The palfrey was a riding-horse popular with nobles for riding, hunting and for ceremonies or show. It could be as expensive as a destrier. A good palfrey would be valued for having an ambling gait, which allowed for a relatively smooth, comfortable ride over a fair distance.

The rouncey was a good all-purpose riding horse that could be used for general transportation or trained for war. A poor knight might have ridden a rouncey.

The jennet was a small, quiet, dependable horse that came by way of Spain. They were popular as riding horses for ladies, although the Spanish used them as cavalry horses.

The hobby horse was lightweight, quick, and agile, and was often ridden in the light cavalry and used in skirmishing.

So like the teenager today who wants a really cool Ferrari or Porsche but discovers that he or she needs to be content with a practical Toyota, the young knight of the Middle Ages might have longed for a stunning destrier or courser, but found himself instead with an aged rouncey.

Kaye and Kadar (from “The Knighting of Sir Kaye”)

Interestingly, in the first book of my Sir Kaye the Boy Knight series, The Knighting of Sir Kaye, twelve-year-old Kaye Balfour has his own destrier named Kadar, which is pretty amazing. The horse was given to him by his father, Sir Henry, and although it’s not mentioned in the first book, Sir Henry got the horse after defeating another knight in battle—to the victor go the spoils.

Kadar is a very kind and gentle horse, if he likes you, and he can have a calming effect on the people around him. He’s also very protective of Kaye and won’t hesitate to jump into the middle of a fight if needed. Kadar has a good instinct about people and is very wary of strangers who seem untrustworthy. Kadar is a very well-trained battle horse too. In a tournament scene in the book, Kadar performed as though he didn’t even need a rider during the horsemanship displays.

I can honestly say that I have a pretty good understanding of how a teenager relates to his first car. But things are different with a living creature like a horse with a mind and a personality of its own. I don’t know very much about that, but I need to, because as I’ve been working on my series of books, I’ve noticed that there are a lot of horses involved. So I reached out to a knowledgeable source and in next week’s blog I’ll share some of the things I learned from equestrian expert Susannah Cord about the unique relationship between a horse and its rider.

December 23, 2013

The Joy of Simple Toys

Each year at this time I’m always amazed by all the new, ever-more-sophisticated toys I see advertised. Sometimes I find myself wondering if maybe they might be just a little too…complicated.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not against sophisticated toys…there may even be a few that I wouldn’t mind checking out. But all this advertising got me thinking about the childhood toys that evoke my favorite memories. I remember a few store-bought toys over the years that I really loved. Building blocks and Erector Sets come to mind and of course there were Lincoln Logs, toy cars and trucks…the usual boy-type toys.

But my strongest childhood memories don’t come from a toy store. Instead, ordinary household objects (oh, say, for example, an empty cardboard box) were what provided me with hours of imaginative entertainment. All my fondest and most vivid memories of playtime are of the times when I imagined my own adventures using simple toys for my props.

One of the best things about kids is their endless capacity for imagination and the joy they get out of it. And it’s truly amazing to watch how they can play with the simplest thing and make it become anything they want. That was certainly the case with me. Imagination is a crucial skill: it allows us to see beyond what’s in front of us and envisage what could be…it’s a skill that serves us well as we become problem-solving adults. The seeds of that ability are sown in imaginative childhood play.

One of the best things about kids is their endless capacity for imagination and the joy they get out of it. And it’s truly amazing to watch how they can play with the simplest thing and make it become anything they want. That was certainly the case with me. Imagination is a crucial skill: it allows us to see beyond what’s in front of us and envisage what could be…it’s a skill that serves us well as we become problem-solving adults. The seeds of that ability are sown in imaginative childhood play.

To all of my blog readers: I’d love to hear your memories about your favorite toy or activity as a child. Please don’t be shy.

Here’s something I wrote years ago to pay homage to what I think of as one of the greatest of all simple toys…the cardboard box.

The Box

The hours seemed like minutes

in a world that I had made.

My adventures without limits

outdid the video arcade.

As captain of my own ship,

I could go from place to place.

At speeds that baffled science,

I explored uncharted space.

What destination will I choose?

My crew is standing by.

The computer says we’re ready,

and the ship is good to fly.

So I fired up the engines,

about to start my ride,

when my mother interrupted,

“Take that filthy box outside!”

December 19, 2013

Is Electronic Media Taking Over Your Family?

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has recently published new guidelines regarding children’s use of the Internet, television, cellphones and video games.

Their recommendations include the following:

Children should have no more than two hours of screen time for entertainment purposes each day.

Children under 2 shouldn’t have any TV or Internet exposure.

Parents should ban electronic media during mealtimes and after bedtime.

Parents should set rules on the use of the Internet, social media, cellphones and texting, including which sites can be visited.

Parents should have access to their kids’ Facebook, Instagram, and other social accounts.

Children should not have televisions or Internet access in their bedrooms.

Why such concern? Because children are bombarded 24 hours a day with opportunities for media consumption—from television to texting and social media. And those stimuli can have a bad effect on children’s health. Marjorie Hogan, co-author of the new policy, says that “Excessive media use is associated with obesity, poor school performance, aggression and lack of sleep.”

Why such concern? Because children are bombarded 24 hours a day with opportunities for media consumption—from television to texting and social media. And those stimuli can have a bad effect on children’s health. Marjorie Hogan, co-author of the new policy, says that “Excessive media use is associated with obesity, poor school performance, aggression and lack of sleep.”

A report from The Kaiser Family Foundation shows that in 2009, children ages 8 to 18 spent an average of 7 hours and 38 minutes a day on media strictly for entertainment, including TV, video games and computer use. Keep in mind that the first iPad was released on April 3, 2010, so it’s likely that usage has increased somewhat since then.

The recommendation that really got my attention was the new suggestion from the AAP that families adopt a no-device rule at mealtimes and after bedtime. This suggestion means that parents would have to abide by the same rule as an example to their children on how to keep technology in its proper place. Ouch!

That got me thinking about how much family time has changed since I was a kid. The idea of a whole family eating dinner together while each person gives most of their attention to a phone or other device is sobering.

When I was kid, no electronic devices existed except television. There were only four stations available, so too much TV watching wasn’t an issue. When we did watch television it was usually as a family. Most Sundays, for instance, we would enjoy watching The Wonderful World of Disney and Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom. But in addition to TV watching, we always ate together as a family (at the table), played board games, and enjoyed lots of outdoor activities.

Since then, the family dynamic has gradually changed. It first started with occasionally moving dinnertime to the living room where we would get out our TV trays and watch a movie during our meal. Remember how cool TV dinners were? That was just the beginning of shifting the focus of family mealtime from the people in front of you to an object. Sadly, the impact of electronics on family time has changed to such an extent over the years that the American Academy of Pediatrics felt that their job to promote children’s health and well-being required them to issue new guidelines for doctors/parents.

What is family? For many people, the idea of family may conjure up warm and cozy thoughts of togetherness. But are recent trends in the use of electronic devices relegating that warm and cozy idea of family to special occasions when everyone is physically, mentally, and emotionally present and actively involved in being together? Is it enough to just live under the same roof if no one is sharing experiences, conversation, and making memories together? What will the next generation look back upon from their childhood? Technological and social benchmarks of continuously upgraded new devices, gaming, and electronic social presence? Or will they have memories of shared meals, story time, and engaging activities done with family?

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not a Luddite. I love technology as much as the next person. After all, tools like computers and audiobooks have allowed this dyslexic guy to have a much fuller life than I would have otherwise had. However, balance is key.

What do you observe in your own family? How do you make time to interact with your kids? Have you found ways to keep electronics in their place? I’d love to hear your responses.

December 12, 2013

Distraction and (un)Happiness

When was the last time you were fascinated with something? Fully engaged? Unaware of the passage of time because you were so lost in the activity? Forgot to eat lunch because  you were having such a great time? Not even remotely concerned with what other people might think of you because all thoughts of self had temporarily vanished? Had a moment where nothing in the world existed for you but the task at hand?

you were having such a great time? Not even remotely concerned with what other people might think of you because all thoughts of self had temporarily vanished? Had a moment where nothing in the world existed for you but the task at hand?

Most of us would have to think hard to remember such an occasion.

And therein lies the problem that is the root of much unhappiness.

One of my favorite studies from Harvard sheds some light on the situation. “A wandering mind is an unhappy mind” say Harvard psychologists Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert. “Our mental lives are pervaded, to a remarkable degree, by the non-present.” In fact, “humans spend a lot of time thinking about what isn’t going on around them: contemplating events that happened in the past, might happen in the future, or may never happen at all.”

This is true. We all tend to rehash old experiences and frustrations, dwell on past failures, replay conversations in our head, project into the future and imagine all sorts of both good and bad outcomes, and in general lose the train of activity that’s right in front of us.

“Mind-wandering is an excellent predictor of people’s happiness,” Killingsworth says. “In fact, how often our minds leave the present and where they tend to go is a better predictor of our happiness than the activities in which we are engaged.”

The broad conclusion of this study is that the more absorbed we are in whatever our current activity might be, the happier we are. When our mind wanders away from whatever we are doing, it makes us unhappy.

Children have an amazing ability to lose themselves in the present moment, to give their entire attention to whatever they are doing without worrying or thinking about other aspects of their life. They demonstrate fascination, where most of their senses are fully engaged with the target of their focus.

So if you have kids, take advantage of their example in this regard. Take some time to get down on the floor and play with them, read with them, talk with them (interestingly, the study found that one of the activities that made people happiest was having conversations). Let yourself get lost in the moment of interacting with your children as they engage with their world. They’re young for such a short time.

And it might just help you to have a happier day too.

December 4, 2013

What is Bibliotherapy?

Have you ever heard of bibliotherapy? I recently learned the term myself when I read about a new study from the University of Cincinnati. Although the word was new to me, the concept behind bibliotherapy is not new at all. As a matter of fact, one of the hallmarks of my picture books is that they are designed to be used for bibliotherapy.*

Have you ever heard of bibliotherapy? I recently learned the term myself when I read about a new study from the University of Cincinnati. Although the word was new to me, the concept behind bibliotherapy is not new at all. As a matter of fact, one of the hallmarks of my picture books is that they are designed to be used for bibliotherapy.*

But what is bibliotherapy? The author of the study, Jennifer Davis Bowman, PhD., describes bibliotherapy as using “books with characters that are facing challenges similar to their reading audience, or books that have stories that can generate ideas for problem-solving activities and discussions.” This works especially well with children.

Although the focus of Bowman’s study was on training parents to use books to help children who deal with social struggles related to conditions like autism or Down Syndrome, all children deal with social struggles of one kind or another and can benefit from parental interaction using bibliotherapy. For instance, what child doesn’t have to deal with peer pressure, bullying, self-image issues, or self-esteem problems? Some children might also struggle with dyslexia or other learning challenges.

Bowman’s study reinforced the foundation established by previous research — that “bibliotherapy can improve communication, attitude and reduce aggression for children with social disabilities.”

Throughout the course of the study, parents took an active role, selecting books based on the values and principles taught by the stories, and the results of the study showed that this was key in helping to teach the children that they have choices.

Children are not born with coping skills; they have to learn them. The role of teacher is primarily occupied by the parents.

Parenting is a challenge even under ideal circumstances, but parental guidance can be much more effective if parents teach their children ahead of time about their options for thinking and acting, rather than just scolding them for unwanted behaviors after the fact. When children see a storybook character dealing with the same feelings or the same challenges that they have, it helps them feel understood.

It’s also much easier for both parents and children to be objective about behaviors that work (or don’t) when they see those behaviors illustrated by characters in a story. Talking about the choices and behavior of a character in a book can be a non-threatening transition to talking about a child’s choices. It can be as easy as saying something like, “What would you do (or have done differently) if you were in this story?”

Reading together opens the doors to so many kinds of conversations that parents can use to help their children.

*How can Don Winn’s CBA books be used to help children in dealing with social issues?

All my CBA picture books are designed for parents/teachers to read aloud with children. Each book has a theme that parents can use to illustrate common life lessons and all the stories have questions for discussion so parents can start conversations about important topics. For a list of topics contained in all my CBA books check out the Lesson Reference Guide.

The hardcover picture books have additional creativity questions at the end that can be used to help kids to use their imaginations and “think outside the book.”

My picture books make great gifts and are available as softcovers, hardcovers, and eBooks from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and the iTunes store, as well as your other favorite online retailers.

All Cardboard Box Adventures picture books have been named among the best in family-friendly media, products and services by the Mom’s Choice Awards®.

November 25, 2013

Snow Days

We just recently had our first cold snap of the season. Depending on where you live, the mid-30′s may not seem like much of a cold snap, but here in central Texas, it’s about as cold as it normally gets. It’s kind of a thrill nowadays to see my breath in the air.

Chilly mornings like this one get me thinking about the many glorious snowbound winters that we had when I was growing up in Denver. I can say glorious now because as a kid I didn’t have to chip ice off the car windshield, shovel snow off the driveway, or brave the slippery streets to get to work. No, for me, bad weather days or snow days meant one thing: I didn’t have to go to school. And for this dyslexic guy, the only thing better than not having to go to school was getting to spend the day out in the snow.

Snow days meant building snow forts, snowball fights with my siblings and neighbors, and my favorite…sledding! Some of the neighborhood kids had actual sleds but the majority of us had to improvise. We used everything from plastic trash bags to flattened cardboard boxes. Sometimes the boys with sleds found that using a trash bag or flattened cardboard box worked even better. The hill behind our house got a real workout on snow days. Those are some great memories.

Snow days meant building snow forts, snowball fights with my siblings and neighbors, and my favorite…sledding! Some of the neighborhood kids had actual sleds but the majority of us had to improvise. We used everything from plastic trash bags to flattened cardboard boxes. Sometimes the boys with sleds found that using a trash bag or flattened cardboard box worked even better. The hill behind our house got a real workout on snow days. Those are some great memories.

To all of my blog readers: I’d love to hear your memories of snow days…

Here’s something I wrote years ago as a remembrance of those special days:

Snow Days

This morning I heard the announcement —

school’s closed ‘cuz it snowed in the night!

I got up without needing prodding,

and was ready to go at first light.

With a scarf and a hat and wool mittens,

galoshes and four pairs of socks,

who wants to be stuck inside sittin’?

I’m goin’ out with the kids on the block!

We built castles and snow forts and igloos,

we hurled snowballs and sledded all day,

with school canceled because of the weather,

we had hours and hours for play.

When I think of those snow days, it’s funny,

we played all day outside as a rule,

but when it was time for our learning,

such days were too cold to hold school.

November 21, 2013

Falconry Part Three – Interview With Lynne Holder, Texas Falconer

Dart the Harris’ Hawk

I was recently able to spend a day with Lynne Holder, a falconer who doesn’t live too far from Austin, Texas. I was researching falconry for my next Sir Kaye book, so I was happy to have the chance to ask someone who is very familiar with falconry all my questions. Here are some of her answers:

What is falconry? Falconry is the practice of caring for, training, and hunting with birds of prey, also known as raptors, and all of the preparation, housing requirements, and equipment-making which goes with that practice.

Can you tell me about your raptor? His name is D’Artagnan, but I call him Dart and that is the name he knows. He is 6 years old. If he stays healthy – and his health is my responsibility – he can live to be 20 to 35 years old in captivity.

What kind of hawk/falcon is your raptor? Dart is a Harris’ Hawk, which is a type of broadwing hawk, and he is a captive bred bird. In nature, Harris’ Hawks are indigenous to the southwest area of the United States, northern Mexico and Central America, and into the southwest part of South America.

What is Dart’s personality like? Dart has a funny personality. He makes odd little noises, some of which are very loud. One reason I have him is because his prior falconer lived in the city limits and having a hawk that screams as much as Dart does can create problems in that environment. I live in rural Texas and Dart has his own house (or mews) behind my house. No one cares whether he screams all day or all night in the country! Dart is a great hunter in the open-prairie type of country I have available in which to hunt. He loves to catch rabbits, rats, mice, and small birds. He is affectionate in a “birdy” sort of way and will sit happily on my knee if given the opportunity to do so. He likes hunting with my pointing Labrador Retriever, Max. I think we three make a good team!

Don’t mess with peafowl – even if you’re a hawk!

What does Dart like to hunt?

His favorite prey is a small rat called a cotton rat, which is indigenous to Texas, but Dart will try to take anything that he thinks he is big enough to capture and kill. This can be a problem. He attacks my adult peafowl if given the chance, which is not good for either Dart or the peafowl! They outweigh him by about 9 pounds and they always win.

Once Dart attacked a full grown black-headed vulture. Neither was hurt, but the vulture threw up on Dart and that was awful! Vomiting on an attacker is a vulture’s first line of defense, and believe me, it is VERY effective. I could barely stand to be within thirty feet of Dart. He looked miserable. I had to mix up a skunk mixture to remove the smell and it still took weeks to go away!

What does Dart eat? Dart eats what he catches, but he prefers rats. He also loves rabbits and birds.

Where does your raptor live? Dart lives in his mews, which is an old term with a meaning similar to stables. My mews was designed and built by my husband and me, and it is a 10 by 16 foot structure. Dart has three perches and he is not tethered, or tied, to his perch. Falconers call this freedom in the mews being free-lofted.

Hawk Bell

Why do hawks wear bells? Hawks in the wild fly very silently. That ability keeps prey from knowing that the raptors are coming. They also are very athletic and can perform all kinds of aerial maneuvers. The bells are to help the falconer find his hawk when out in the field!

Are you ever worried your raptor will fly away and not come back? I absolutely worry that my hawk will disappear. Nothing attaches Dart to me when he is flying. He could leave if he wanted to leave. This fact is why most falconers have invested in relatively expensive telemetry equipment. My hawk wears a transmitter at all times. I turn it on when I am flying him and turn it off when he is not hunting. Fortunately, most of these incidents are avoided by training, which I will explain later. I have, thankfully, never lost a hawk.

What does it feel like to train a raptor? My first raptor was a wild-caught red-tailed hawk that I named Artemis. (The law requires that an apprentice falconer capture and train a wild-caught raptor that has a large natural population for two years before the apprentice can legally become a licensed falconer.) I caught him myself and trained him. The first step was to get him used to me, so for the first few days that I worked with Artemis, I went into his room in the dark, sat down beside him as he was tethered to his perch, and slipped my gloved fist under his feet and lifted him off of the perch. For about four days, every time I put him on my fist, he squeezed my hand with his feet and talons so hard that it almost made me cry. His talons could not pierce the very thick glove I was wearing, but the sheer pressure of him squeezing my hand was extremely painful. If I had tried to do the same thing in a lighted room, he would have simply tried to fly away and could have hurt himself or damaged some feathers. This initial method of training him was to show him that I was not a dangerous creature who was going to try and eat him. Artemis voluntarily stepped to my gloved fist for some red rabbit meat several days later. I was stunned and thrilled and also scared. Once he stepped willingly to my fist without trying to escape and without trying to crush my hand, I had penetrated a giant barrier in terms of creating a relationship with my wild hawk. This first critical step meant that he trusted me not to hurt him and he trusted that I would provide him food. The fact that it happened so very quickly — in just a few days — was astounding to me and created a bond between my hawk and me that, for me, was a feeling I will never forget.

Did it take a long time to train your raptor? After I trapped Artemis, his first free flight was approximately six weeks later. The day after his first free flight, he successfully caught a cotton-tail rabbit on our first hunt together.

What was the hardest part of training your raptor? For me, the hardest part was realizing that I was going to be alone in a room with a wild hawk. Although I had been coached and had handled other falconers’ birds of prey by the time I trapped Artemis there is no feeling quite like the one that occurs when you walk in the room and a wild bird of prey is staring you in the eyes.

What kind of person makes a good falconer? In my opinion, a person who is a good hawker is someone who puts the needs of their raptors first and provides good quality care, shelter, equipment, training, and most of all, someone who is willing and able to spend the time in the field hunting with their hawks.

Would you say that falconry is like a glimpse back in time? I would definitely say that hawking is a glimpse back in time. In medieval days a Goshawk could provide food to supplement the diet of a family of four during the winter. Trained raptors are efficient hunters, and as long as they don’t feel cheated, they don’t mind giving up what they have caught. Dart frequently catches something that is larger than he can eat in one setting, as all raptors do. I reward him with different food and quietly transfer him off of the prey I don’t want him to eat in the field. If I want to hunt with Dart for several hours and the prey is abundant, I feed him just enough during the hunt to keep him interested. Once a hawk feels full, or cropped-up, he quickly loses interest in following the falconer, so the process is a delicate balance. Wandering around in the wild for hours with only a hawk and a dog for company heightens a falconer’s senses about everything around him. Imagining the same process in a time when there were no machines and no industry to speak of is not a far stretch of the imagination when I am walking around with my hawk.

What has changed about hawking since medieval times? In my mind, the biggest and most obvious changes involve the knowledge that we now have of veterinary medicine for birds of prey and the technology which helps us to maintain, hunt, breed, and prioritize the safety of our hawks. A less obvious, but maybe more important change is the fact that through proper preparation, study, and commitment, almost anyone can be a falconer in the United States.

Is there anything else you would like to share? Falconry is a great part of my life and I am so happy to have found this wonderful passion. I wish everyone could experience the joy and the thrill of handling a bird of prey, of hunting with him, of having him look into your eyes as a superior predator, and of having such a fabulous creature as a partner in a hunt in the wild. I’d like to share the feeling of my hawk trusting me to approach him when he is on prey, and to experience the knowledge that a falconry bird of prey flies free to go wherever he chooses, and that so far, he has always come back to me.

Hanging out at the ranch.

November 14, 2013

Falconry Part Two – My Day With Dart

Dart the Harris’ Hawk on his trainer’s gloved fist.

As promised, here are a few highlights from my day with Texas falconer Lynne Holder, her hawk Dart, and her dog Max.

First we toured Dart’s mews. Just like horses have stables, trained hunting hawks live in mews when they are not working. Dart’s mews is a free-standing building in Lynne’s backyard, in the shade of an Osage orange tree. It has a vestibule, so a person enters the building, closes the outside door, and then opens an inner door to get to the area where Dart lives. The extra security provided by the vestibule minimizes the chance that the hawk will escape and also keeps the atmosphere inside comfortable for him.

Inside the outer vestibule, Lynn reached into a small freezer to pocket a little bag of frozen rodents. They are a training tool for Dart, as well as a treat with which to lure him away from inappropriate prey. Then she put on her heavy leather glove, or gauntlet, to protect her hand and arm because Dart’s talons can exert a pressure of up to 200 pounds per square inch per talon. In fact, just the day before, he had gripped her bare hand too tightly and torn a nasty gash in her thumb.

When we entered the large, airy room where the raptor spends most of his time, Dart was settled on a large perch high up in the corner of the room, where he can see through three good-sized, vertically-barred screened windows.

Here you can see Dart’s coloring, as well as the transmitter attached to his back.

He took a moment to cautiously observe us, but I could tell he obviously felt he was still in charge. I, on the other hand, was awed by his silent presence. I could sense his raw power—the nature of his being a raptor was palpable—and kept a respectful distance. I did not attempt to touch him at that time. We were on his turf, after all.

Lynne held the bird and talked to him, describing to me what it was like to be the partner of this magnificent bird. When Dart flew back up to his high perch, Lynne reached down to the floor of the mews and showed me a bleached-looking hard white lump about the size of her thumb. This was a casting—a lump of indigestible leftovers like hair, feathers, and bones which Dart had regurgitated after his digestive tract had removed all the nutrients. A falconer can regularly study a hawk’s castings to keep tabs on certain aspects of the hawk’s health.

Close up of Dart

Dart also has a second, small perch attached to a digital scale, and as soon as he had finished checking out his strange visitors, one of the first things he did was to fly to his perch above the scale. Smart boy. He has learned that he cannot go outside to hunt unless he has first perched on that contraption so Lynne can record his weight.

Why? Lynne explained that only a lean bird wants to hunt. A bird who has been eating too much in his comfortable mews will feel no need to hunt, so his weight is monitored to see when he will be an active hunter. Sometimes only an extra fraction of an ounce in a hawk’s weight will determine if he is ready to hunt or not.

T-Perch

The good news is that on the day of my visit, Dart was in top shape and ready to hunt. Although I mentioned in my previous blog that not much about basic falconry has changed since the Middle Ages, there is one area where technology has made a huge difference. When Dart goes out to hunt, he wears a special radio transmitter. It’s fastened to a “backpack” which is made of small straps carefully wrapped around his body so as not to interfere with his movement or damage his feathers. This way, if he goes after some prey and travels for a long distance on his powerful wings, Lynne can track him and make it easier for him to find her again.

I did not try hunting with Dart from my fist, but during part of the hunt, I was able to hold a tall pole with a perch on the top where Dart sat. This is called a T-perch and it’s a fairly modern (as in, not medieval) American invention that gives the hawk a better view of the surrounding area. Lynne mentioned she always wears a hat to help protect herself from any possible droppings while Dart is on the perch. After she mentioned that, I started wishing I had worn a hat that day, but fortunately, I stayed clean.

Lynne and Dart also tandem hunt with a charming black Lab named Max. Max works with Dart as his “flusher.” Max runs around excitedly, nose to ground, tail wagging, sniffing for cotton rats, field mice, or other small prey. All his running and sniffing spooks Dart’s potential prey into moving so that Dart can see the movement and strike the prey. Most of the time during the hunt, Dart impassively watched Max carrying on like, well, like a black Lab. But the second Max’s body language indicated that prey was near, Dart moved like a bolt of lightning. He swooped noiselessly and with great economy of motion to take down first a small bird, and later a cotton rat. His attack was instantaneous, precise, and deadly. He moved so fast on his first kill that all we saw were a couple of pinfeathers hanging out of his beak as evidence of the meal.

Dart in flight

It was fascinating to see the interaction between Dart and Max. Max was in it for the good time—believe me, if you got a chance to see Max, you’d know this was the best fun he could ever imagine. And Dart? It’s hard for a novice like me to read a hawk’s body language, but I thought I could sense a certain satisfaction from Dart with the outcome of the day’s hunt.

Check back next week for my interview with Lynne about modern falconry.

Max and Dart