Don M. Winn's Blog, page 26

June 26, 2014

Motivating Struggling Students—Does Word Choice Really Matter?

Last week I discussed the results of a study that found that children are more likely to help clean up their messes if they have been encouraged to think of themselves as “helpers”—a noun—instead of someone who is supposed “to help” clean up—a verb. The reason for these results are that using a noun (the word “helper”) “may send a signal that helping implies something positive about one’s identity, which may in turn motivate children to help more,” according to Christopher J. Bryan, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of California, San Diego.

As regular readers of this blog know, I am passionate about helping and motivating struggling readers. Many of these kids don’t think of themselves as readers at all (or as good students) because of dyslexia, ADD, or other challenges. Most are so frustrated that they repeatedly shy away from situations involving reading or student activities as a way to reduce their stress. But this ultimately causes more stress, as the educational gap widens exponentially between them and their peers.

As regular readers of this blog know, I am passionate about helping and motivating struggling readers. Many of these kids don’t think of themselves as readers at all (or as good students) because of dyslexia, ADD, or other challenges. Most are so frustrated that they repeatedly shy away from situations involving reading or student activities as a way to reduce their stress. But this ultimately causes more stress, as the educational gap widens exponentially between them and their peers.

Could changing our wording in these areas as parents and teachers help?

A reader is someone who reads. And these kids do read. In fact, they have to work much harder to read than those without learning challenges. If we are measuring effort here, not just results, our struggling readers are actually greater readers than those who are not challenged. To echo Dr. Bryan’s words above, wouldn’t using nouns instead of verbs when talking to kids with learning challenges also ‘imply something positive about their identity,’ thereby ‘improving motivation’? In a world focused solely on results, not effort, discovering personal motivation based on a positive identity concept can be a force for good for the struggling student.

Here are a few suggestions:

Say, “Let’s be readers,” instead of, “Lets’ read a story.” Get even the youngest children used to the idea that they are readers and will be for life.

Replace “How was school today?” or “Did you do your homework?” with, ”Were you a good student today?” Encourage them to share the reasons for their answers.

Tell kids stories from their past about things they have already learned or mastered. Reminding a child with words like “You’ve always been a curious learner!” or “You were such a hard worker at that until you figured it out!” helps them recognize that they have a lifelong history of being good learners, not just struggling students. Indeed, if we set out to list the things our kids have already learned and mastered, their successes would be myriad. They need to feel the mantle of success on their shoulders when they are working hard to learn new things.

Tell kids stories from their past about things they have already learned or mastered. Reminding a child with words like “You’ve always been a curious learner!” or “You were such a hard worker at that until you figured it out!” helps them recognize that they have a lifelong history of being good learners, not just struggling students. Indeed, if we set out to list the things our kids have already learned and mastered, their successes would be myriad. They need to feel the mantle of success on their shoulders when they are working hard to learn new things.

If you employ some of these ideas, let me know what you observe. Invoking a positive sense of identity in kids may help them be better helpers, learners, readers, friends, and people. And their rooms might just look a little cleaner, too.

June 19, 2014

Having Trouble Getting Kids to Clean Up? Try this!

If you’re having trouble getting your kids to clean up their messes, try changing the words you use.

A recent study shows that using nouns instead of verbs has a positive impact on a child’s response to an adult’s request for help. Why? Because using nouns affects a child’s sense of identity. Using verbs, such as the word “helping,” does very little to invoke identity. But rewording the same request to include a noun—for example, using a phrase such as “being a helper”— appeals to a child’s sense of who they are and how they see themselves. This simple rewording can yield a very different (and positive) result.

Researchers worked with 150 preschoolers ages 3-6. The kids were allowed to play with toys, and were then provided opportunities to help a researcher pick up a mess, clean up spilled crayons, open containers, or put away toys. Each opportunity would require the child to stop playing in order to assist the adult.

Researchers worked with 150 preschoolers ages 3-6. The kids were allowed to play with toys, and were then provided opportunities to help a researcher pick up a mess, clean up spilled crayons, open containers, or put away toys. Each opportunity would require the child to stop playing in order to assist the adult.

The children were divided into three groups. In the first group, a researcher talked to the children about helping, using it as a verb (“some children choose to help”) before letting them play with the toys. In the second group, the researcher replaced verbs with nouns and talked about being a helper (“some children choose to be helpers”). The third (baseline) group was allowed to play without hearing any discussion about helping or being a helper.

When given the opportunity to stop playing with toys in order to help the researcher, the group with whom the verb form of helping was discussed were no more responsive than the baseline group. Not a lot of cooperation, in other words. Sound familiar?

Remarkably, the group who had heard about being helpers responded to requests of researchers in a significantly more positive way than the other two groups. What does this suggest? That “parents and teachers can encourage young children to be more helpful by using nouns like helper instead of verbs like helping when making a request of a child,” says Christopher J. Bryan, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of California, San Diego, who worked on the study. “Using the noun helper may send a signal that helping implies something positive about one’s identity, which may in turn motivate children to help more.”

Remarkably, the group who had heard about being helpers responded to requests of researchers in a significantly more positive way than the other two groups. What does this suggest? That “parents and teachers can encourage young children to be more helpful by using nouns like helper instead of verbs like helping when making a request of a child,” says Christopher J. Bryan, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of California, San Diego, who worked on the study. “Using the noun helper may send a signal that helping implies something positive about one’s identity, which may in turn motivate children to help more.”

In short, children who are taught to think positively of themselves as helpers are far more likely to help clean up than children who just see helping to clean up as an unpleasant activity. So encourage your kids to think of themselves as helpers and let me know if you see any positive results.

Next week I’ll take this a step further and discuss how parents and teachers can use the findings of this study to help motivate kids with learning challenges.

June 5, 2014

Kids and Money Matters – Discussing Family Finances

Many moons ago, when my son was about four years old, we were out shopping when we saw a shiny red boat on display at a nearby mall. It caught his eye and together we admired it. We imagined how fun it would be to own it, but I did eventually have to tell my son that we just couldn’t afford that cool red boat. That didn’t make my son hesitate for even a second. He excitedly piped up, “Just write a check for it!” After all, we had lots of checks in the checkbook.

Many moons ago, when my son was about four years old, we were out shopping when we saw a shiny red boat on display at a nearby mall. It caught his eye and together we admired it. We imagined how fun it would be to own it, but I did eventually have to tell my son that we just couldn’t afford that cool red boat. That didn’t make my son hesitate for even a second. He excitedly piped up, “Just write a check for it!” After all, we had lots of checks in the checkbook.

This anecdote illustrates that as children observe parents transacting business and purchasing items for the family, they may come to some very inaccurate conclusions. They may assume that checks can be used for anything, and that nothing more is required. Or that Mom or Dad can punch a few buttons on a shiny machine and it spits out cash. Or that little pieces of plastic in our wallets are the key to happiness and instant gratification, or at least a quick snack at MickeyD’s.

Many families decide on an allowance for their kids as a way to teach them to manage their individual resources wisely. Kids quickly learn that if they spend their whole allowance on ice cream or a video game, they won’t be able to buy anything else until their next allowance day. In this way they learn that saying yes to one purchase means saying no to others. Personal saving, spending, and earning can all be learned through this avenue of experience.

But what about the way kids understand the family’s finances? The University of Texas and North Carolina State University recently published a revealing study about kids, parents, and money talk. The average age of the participants was 10.8 years.

The study identified a taboo around family finances: most families do not discuss parental income, debt, family investments, or budgeting with their children. According to the study, kids don’t know why their parents avoid these subjects, but “some children said they thought parents didn’t want to discuss these topics because parents were afraid of scaring their children, or of having the children brag about their family’s finances or compare their financial circumstances with other families.”

“Broadly speaking, we found that parents were most likely to talk with their kids about saving, spending and earning,” Dr. Romo of NC State says. “The children said they felt their parents talked about these subjects to prepare kids for the future.”

“The takeaway here is that even young kids are aware of financial issues, regardless of whether parents talk with them about money,” Romo says. “And if parents aren’t talking with their kids about subjects like family finances or debt, the kids are drawing their own conclusions – which may not be accurate. Even if parents don’t want to discuss family finances with their children, it may be worthwhile to explain why they don’t want to discuss that topic.”

The study also revealed a difference in what parents did communicate with children about money matters based on their children’s gender. Though overall there was little discussion of investments or debt, parents were much more likely to talk about investing and debt issues with their sons than with their daughters.

The bottom line: kids are constantly learning, observing us, and drawing conclusions. If we don’t start teaching them financial responsibility, how money works, the traps of debt, and the wisdom of delayed gratification, they can have a lot of misconceptions and even stress about family financial issues. Teaching children how family finances function can help them become responsible adults who understand money matters.

May 20, 2014

Remembering Dad

It’s been over 30 years since my dad passed away. Sometimes it feels so very long ago; at other times, it feels like it just happened yesterday. Although he died when I was a still a very young man, I have precious memories of my dad that keep him alive in my heart.

It’s been over 30 years since my dad passed away. Sometimes it feels so very long ago; at other times, it feels like it just happened yesterday. Although he died when I was a still a very young man, I have precious memories of my dad that keep him alive in my heart.

Starting around 3 or 4, I spent most of my time with my dad. Whenever possible, I would go with him on his sales calls and errands—I liked the lumber yard the best. When he worked on home projects, which were many and frequent, I was always underfoot wanting to help, and he would always let me help, even though it usually made more work for him. When he was busy with paperwork, I was again right there beside him with my own make-believe desk and a handful of very valuable junk mail I had pulled out of the trash so I could pretend to be a businessman like my father.

Starting around 3 or 4, I spent most of my time with my dad. Whenever possible, I would go with him on his sales calls and errands—I liked the lumber yard the best. When he worked on home projects, which were many and frequent, I was always underfoot wanting to help, and he would always let me help, even though it usually made more work for him. When he was busy with paperwork, I was again right there beside him with my own make-believe desk and a handful of very valuable junk mail I had pulled out of the trash so I could pretend to be a businessman like my father.

I watched him while he shaved, shined his shoes, put on a tie, all the while volleying more questions his way than even the US Olympic Tennis Team could return. And last but not least, I was always there when he raided the refrigerator for a bedtime snack—homemade ice-cream was my favorite.

I watched him while he shaved, shined his shoes, put on a tie, all the while volleying more questions his way than even the US Olympic Tennis Team could return. And last but not least, I was always there when he raided the refrigerator for a bedtime snack—homemade ice-cream was my favorite.

But of all my memories of my dad, the most poignant ones are of the scary times when I needed reassurance. At those moments, my dad was my true hero. Whenever I was frightened or in over my head for any reason, I knew that I could call on my dad and he would be there for me. I guess you can say it was a lot like flashing the bat signal with the confidence that Batman would be there just in time to save the day.

I wrote Superhero in remembrance of my dad. He was always my superhero. In this book I pay tribute to my love for him, and hope to remind all parents that taking the time to reassure your children through their fears and insecurities will create a bond with them that lasts their whole lives.

So if you know a boy whose dad is his hero — or a girl who thinks the world of her dad — check out my book Superhero and share it with them.

May 15, 2014

Is Your Child a Late Bloomer? How You Can Help

When you think of Beethoven, what comes to mind? A musical genius that speaks to generations of music lovers. Thomas Edison? A brilliant scientist and inventor. Henry Ford? A manufacturing innovator who changed the landscape of business forever. Enrico Caruso? He was ”The Voice,” long before there was a TV show by that name.

When you think of Beethoven, what comes to mind? A musical genius that speaks to generations of music lovers. Thomas Edison? A brilliant scientist and inventor. Henry Ford? A manufacturing innovator who changed the landscape of business forever. Enrico Caruso? He was ”The Voice,” long before there was a TV show by that name.

Why are we remembering these fellows in today’s blog? They were all late bloomers. Their early life experiences showed little to no inkling of the genius that would prove itself over time.

Beethoven’s music teacher said, “as a composer he is hopeless.”

Edison’s teacher declared that he “would be unable to learn.”

Henry Ford was graded as ”showing no promise.”

Caruso’s music teacher told him he “had no voice at all.”

In a culture that worships the young genius as the only true virtuoso, a culture that believes genius is born, not developed or grown into, the late bloomer may feel more like a “non-bloomer.” And non-bloomers don’t usually feel good about themselves. If you are a parent or teacher of a child who may be a late bloomer, perhaps you have felt some of their disappointment or frustration with themselves. How can you help?

In a culture that worships the young genius as the only true virtuoso, a culture that believes genius is born, not developed or grown into, the late bloomer may feel more like a “non-bloomer.” And non-bloomers don’t usually feel good about themselves. If you are a parent or teacher of a child who may be a late bloomer, perhaps you have felt some of their disappointment or frustration with themselves. How can you help?

Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker article on late bloomers is worth looking into. In it, he reminds us that “on the road to great achievement, the late bloomer will resemble a failure: while the late bloomer is revising and despairing and changing course and slashing canvases to ribbons after months or years, what he or she produces will look like the kind of thing produced by the artist who will never bloom at all. Prodigies are easy. They advertise their genius from the get-go. Late bloomers are hard. They require forbearance and blind faith. (Let’s just be thankful that Cézanne didn’t have a guidance counselor in high school who looked at his primitive sketches and told him to try accounting.)”

In his article, Gladwell references the work of economist David Galenson, who has discerned two types of artistic creativity, two pathways to success. Young achievers who make bold quantum leaps in thinking are referred to as ”conceptual innovators.” They are all about the find, rather than the search. They often have little patience for process, research, analysis. They have one underlying idea; execution is necessary but not typically a pleasure, since they focus with certitude on the finished product.

Late bloomers are referred to in his work as ”experimental innovators.” Experimental innovators try things over and over again, refining as they go, often for decades, and usually feeling they are not ever finished or satisfied with their projects. Their ideas can only develop through the doing of repetitive tasks, pacing through the process with patience and tenacity.

Like many of the individuals mentioned at the beginning of this blog, late bloomers can often fall through the cracks of our educational system, struggling to process information in the way that makes sense to their brain. Frequently they may have learning challenges like dyslexia or ADD/ADHD.

Both creative types, and the sub-types that fall somewhere in between, have things to offer, and each have their own strengths. The problem for us as parents and educators is that we can become so tied to the expectation of the glory of early genius, conceptual genius, that we show disappointment or disapproval when our child or student fails to ‘deliver’ such on our expected timeline. And this is tragic, since one of the most profound conclusions of Galenson’s work shows that late bloomers don’t bloom without lots of patient, loving, loyal support.

Both creative types, and the sub-types that fall somewhere in between, have things to offer, and each have their own strengths. The problem for us as parents and educators is that we can become so tied to the expectation of the glory of early genius, conceptual genius, that we show disappointment or disapproval when our child or student fails to ‘deliver’ such on our expected timeline. And this is tragic, since one of the most profound conclusions of Galenson’s work shows that late bloomers don’t bloom without lots of patient, loving, loyal support.

So give your kids that kind of support. Believe in them. Teach them the value of being patient with themselves and the value of tenacity when pursuing a goal. And above all, give them all the time they need to grow into their own particular gifts. One of these days, they may just surprise both you and themselves.

May 1, 2014

It Only Takes One Teacher to Make a Difference

May is Teacher Appreciation month, and I wanted to offer my gratitude to two special teachers I had as a child. In general, I did not enjoy school because I almost always felt inadequate compared to my peers. I was a dyslexic student at a time when dyslexia was not understood and often not even recognized for what it was. This made it hard for me, and most of my school memories are an unhappy blur. However, there were two teachers early in my life that I remember very clearly and they both taught first grade.

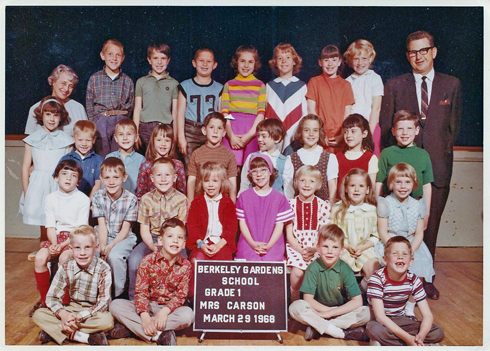

Mrs. Carson (upper left corner of the photo) was my first grade teacher and I have to say that she was probably my favorite teacher. I liked her so much, I took her class twice! Not really, I had to repeat the first grade because I was held back, and Mrs. Carson was my teacher both times. The good news is that I really did like Mrs. Carson. She reminded me of my grandmother. She was very kind and patient with me and never made me feel like I was stupid—and that was good, because I did a fine job of that all on my own. And that’s where Mrs. Davis came into the picture.

Mrs. Davis was a special education teacher and apparently out of concern, Mrs. Carson had consulted with her about my difficulties. It was my understanding that Mrs. Davis had been taking some extension courses about dyslexia and recognized my symptoms. That’s when I was officially diagnosed as dyslexic. From that point forward I was excused from Mrs. Carson’s class for one hour each day and Mrs. Davis worked with me one-on-one and helped me with my reading—and that was a huge turning point in my education.

Even after all of these years I still remember my one-on-one sessions with Mrs. Davis quite vividly. I remember Mrs. Davis opening a book that I liked (mainly because it had a lot of pictures) and the first thing she did was to cover the pictures, which startled me because I had always gravitated to just using the pictures to interpret a story. Once the pictures were covered, she would take a card and place it under a sentence so I could better focus on each word. Then she would step me through each word, identifying the syllables and helping me to sound them out.

Today we have a much better understanding of dyslexia: it impacts much more than just reading, and it doesn’t go away. And although dyslexia was not well understood at the time, the kindness, patience and one-on-one attention that I received from Mrs. Carson and Mrs. Davis helped me tremendously. I will always appreciate their efforts and help. They planted the idea that it was possible for me to learn ways to cope with my dyslexia. When that idea finally took root and bore fruit, it was a crucial revelation in my life.

Who was your favorite teacher and why? I would love to hear from each of my blog readers about the teacher (or teachers) you are grateful for and how they made a real difference in your life.

This jaunt down memory lane got me thinking that it only takes one (or two!) special teachers to make a difference in a child’s life. Clearly, that memory has stayed with me through all these years, because two of my picture books feature caring teachers that made a significant difference in a student’s life. I have been thrilled with the positive feedback that I’ve received from both parents and teachers on how these books have benefited their kids.

In The Incredible Martin O’Shea is about Martin, an energetic boy with a big imagination who has trouble paying attention in school. A visiting professor helps Martin to understand how learning combined with his very active and incredible imagination can help him to enjoy many real-life adventures. View The Incredible Martin O’Shea video.

The Higgledy-Piggledy Pigeon is the story of a carrier pigeon named Hank who has a poor sense of direction due to dyslexia. Hank’s caring teacher patiently helps him learn to compensate for his learning difference and this has a tremendous impact on his life.

View The Higgledy-Piggledy Pigeon video.

April 24, 2014

Lute Music During the Middle Ages—Interview with Ron Braley

Can you imagine life without having access to music at the touch of a button? Music is such an intrinsic part of all of our lives that it’s difficult to think of going for a month, a week, or even a day without listening to pre-recorded music. For some of us it could be next to impossible. In our lifetime we have an endless selection of music that we can access at any time and from anywhere, even from that otherworld called ‘the cloud.’

Of course life was not like that back in the Middle Ages. Anytime you wanted to hear music, you had to make it yourself, or find someone who could make it for you.

While working on The Lost Castle Treasure, my second novel for middle readers, I needed to learn something about music and musical instruments during medieval times. To help me out, Ron Braley, a medieval and Renaissance music enthusiast and lute player, has graciously agreed to answer a few questions for us.

What is a lute?

It is a stringed musical instrument, beautiful both in sound and appearance, that became the stuff of myths. The lute was often meant only for the ears of noble people like kings and queens. Imagine a teardrop-shaped guitar, but instead of a flat back, the lute has a deep, rounded back, almost like the hull of a boat or the curved dome of a shell. Instead of having a guitar’s round sound hole on the front, a lute has a carved area called the rose.

Where did it come from? How long has it been around?

The lute began as an ancient Arabic instrument. In fact, its name evolved from the Arabic al-ud, which means “the wood.” The ud came to Europe after the crusades and grew into the European lute probably in the 14th century after being played for nearly 1,000 years in the Middle East and Asia.

How important was the lute in music during the Middle Ages?

How important was the lute in music during the Middle Ages?

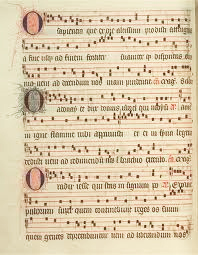

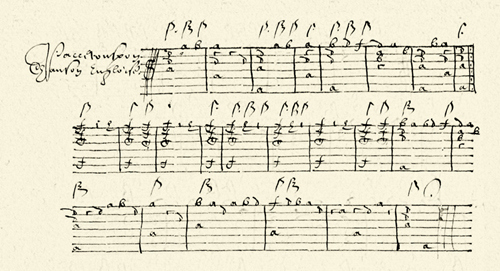

The lute was the stringed musical instrument of the times. It was portable and very useful for singing ballads, dancing, and worshipping at church. Smaller lutes were playable by nearly anyone. Larger lutes were more difficult to play and, therefore, mastered by fewer medieval musicians. Musical notations of beautiful lute songs written during this age have survived for hundreds of years and can still be played today (pictured right).

Do any medieval lutes still exist today?

Several ancient lutes do exist; some can be seen in museums. At least one has been restored and used by Jakob Lindberg to record later medieval music recently.

Can you tell us about any myths or mysteries about the lute? The lute was believed to possess magical healing powers, and its beautiful sounds were said to sooth even the most troubled soul. The intricately-carved rose covering the sound hole (pictured left) was thought to aid healing. This came at a time when about half of Europe’s population was dying of bubonic plague. A common misconception at the time was that flowers could help cure someone who was infected. The lute’s rose, as a flower, represented that possible healing power.

The lute was believed to possess magical healing powers, and its beautiful sounds were said to sooth even the most troubled soul. The intricately-carved rose covering the sound hole (pictured left) was thought to aid healing. This came at a time when about half of Europe’s population was dying of bubonic plague. A common misconception at the time was that flowers could help cure someone who was infected. The lute’s rose, as a flower, represented that possible healing power.

The printed music for lutes looks different than typical music notation. What are those differences and how do they apply to the lute?

Medieval and modern music notation consists of dots or diamond-like shapes and stems representing a particular tone on a musical scale. A singer or player needs to understand not only how to read those symbols but how the next notes should sound. Lute music notation is called tablature (pictured below). Instead of dots representing a tone, lute tablature tells a player where to put his fingers to make notes or chords. It uses numbers or letters to represent a particular fret or finger. This makes the playing of an instrument like the lute where there may be several places on the fret board to play the same tone much easier and precise.

Can you tell us about some famous lute players?

A lute player is called a lutenist. Many, many people wrote music for the lute, although not all of them actually played the instrument! Johann Sebastian Bach loved the lute and wrote music for it, but he didn’t play. One of the most famous lute players from the medieval period was John Dowland. He was an Englishman who played for the King of Denmark until James the 1st allowed him to join his court as a royal lutenist shortly before John died. An air of mystery surrounded Mr. Dowland, as he was rumored to have been a spy for England!

How did you become involved with the lute? Where do you play?

I heard a recording of baroque lute music in 1992 while in England, and instantly fell in love with the sounds of the lute and the music itself. After some investigation, I found a lute I could use to start playing late-medieval music and began my long journey as a lutenist. My first lute-playing job was at a mall in Mississippi in 1993 and I continue to play whenever and wherever I can. I’ve played recently at Star Co. Coffee and Water-2-Wine in Round Rock and will play for a friend’s wedding soon. My wife, Joanne, has a beautiful voice and often joins me in performing lute-voice songs.

Many thanks to Ron Braley for sharing his knowledge and love of the lute with us!

April 17, 2014

Medieval Cookery Experiment

After reading so much about medieval food and cooking while researching my next book, I decided to give it a try myself. I find medieval recipes fascinating, with their unusual (by today’s standards) combinations of flavors and the loose phrasing of the directions that can be interpreted freely by the cook.

I chose to use a recipe from the Gode Cookery website, so that anyone reading can try the same recipe for themselves. If you have time, check out the website; it can be fascinating to read the original medieval instructions and then see how they’ve been translated into modern English and updated to use modern ingredients.

For example, the Gode Cookery website provides the text of some original instructions for making makerouns, an early forerunner of what we know as macaroni and cheese. Here’s a direct quote from the website:

Take and make a thynne foyle of dowh, and kerue it on pieces, and cast hym on boiling water & seeþ it wele. Take chese and grate it, and butter imelte, cast bynethen and abouven as losyns; and serue forth.

Happily, here’s another direct quote from the same website that translates the recipe very simply to:

Macaroni. Take a piece of thin pastry dough and cut it in pieces, place in boiling water and cook. Take grated cheese, melted butter, and arrange in layers like lasagna; serve.

Then the website provides more detailed instructions and helpful hints and tips for modern cooks wishing to recreate the dish.

So now it’s time to share my own medieval adventure in the kitchen. In homage to Reggie (a character in my book), I decided to make his favorite dish, a meat pie. The recipe I chose is for a Hatte, which is a hand-held meat pie that can be made to look like a medieval hat. If you want to try the recipe for yourself, here’s the link to the original recipe.

I did make a few alterations to the recipe—I used agave nectar instead of sugar, I left out the egg yolks from the filling and I made the meat pies in a half-moon shape instead of the hat shape, which made it unnecessary to dip the pies in batter before frying.

Don Winn’s Version of Medieval Meat Pie

1 lb ground veal

1 lb ground pork

1/2 medium yellow onion, diced (1 cup diced)

8 oz diced dates, pits removed

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1/3 teaspoon mace

1 teaspoon cumin seed

1 1/2 teaspoons Turkish saffron

1/2 teaspoon Grains of Paradise

1 teaspoon agave nectar

Salt to taste

Generous grinding of fresh black pepper

Grape seed oil sufficient for frying and a deep skillet

Short pastry of your choice, sufficient for 8-10 8 inch rounds of pastry (I used prepared pie crusts from the grocery store to save time.)

Step One

In a large skillet, brown the meat and onion for 4 minutes to render some of the juices and fat, then add dates. (The juices will hydrate the dried dates.)

Step Two

Stir in all seasonings except saffron and allow the meat to cook until browned, and the moisture from the meats and onion evaporates. The filling needs to be dry so as not to make the pastry soggy. Add the saffron and stir to incorporate. Remove from flame.

Step Three

Place desired amount of filling, (I used 1/2 cup) on half of an 8″ pastry round, leaving an inch around the edges of the dough bare for sealing. Fold the circle of dough in half, encasing your meat filling. Press edges of dough together to form a seal.

Step Four

In a deep skillet, heat 2-3 inches of Grapeseed oil until shimmering. Drop in a scrap of pastry dough to test the heat of the oil: the pastry should float on top and sizzle. When heated, lower one meat pie into the hot oil and fry until it’s crisp and golden. The cooking time will depend on the type of pastry and how much filling was used. Remove to a heatproof plate lined with paper towels. Repeat with each meat pie, cooking one at a time until finished.

I think the spices turned out very well in my experiment but for the next time, unlike the medieval culinary experts, I would not include dates or sweeteners of any kind, although that might just be my personal taste.

I think the spices turned out very well in my experiment but for the next time, unlike the medieval culinary experts, I would not include dates or sweeteners of any kind, although that might just be my personal taste.

April 10, 2014

Medieval Food Facts for Kids

In last week’s blog I shared a little bit about my family history with food that was inspired by work on my second Sir Kaye book, The Lost Castle Treasure. As promised, today I’m going to share a few things I’ve learned about food and cooking during the Middle Ages.

Here are a few interesting facts:

In medieval times the poorest of the poor might survive on garden vegetables, including peas, onions, leeks, cabbage, beans, turnips (swedes), and parsley. A staple food of the poor was called pottage—a stew made of oats and garden vegetables with a tiny bit of meat in it, often thickened with stale bread crumbs.

In medieval times the poorest of the poor might survive on garden vegetables, including peas, onions, leeks, cabbage, beans, turnips (swedes), and parsley. A staple food of the poor was called pottage—a stew made of oats and garden vegetables with a tiny bit of meat in it, often thickened with stale bread crumbs.Brown bread made from rye, barley, or oats was eaten in most homes on a regular basis. When it got stale, it was crumbled and used to thicken soups and stews. The stale bread could also be cut into thick slices and used as plates called trenchers. Manchet, or white bread made from wheat, was usually only eaten by the wealthy.

Fresh milk did not last long in the Middle Ages because there was no refrigeration. So milk was made into cheese that had a shelf life of several months. Instead of fresh milk, some wealthier households used nut milk— ground almonds or walnuts boiled and strained through a sieve. The liquid collected was used as a substitute for milk in soups, main dishes, and desserts.

Many households raised chickens, ducks, or geese for eggs and eventually for meat, but only after they had stopped laying. These birds were far more valuable as egg-producers than as meat for the table.

The homes of the nobility often had “deer parks,” which were wooded areas where the gentry could hunt for sport and food. Peasants who poached game on these reserves might even be put to death if caught. One exception was rabbits—a peasant caught poaching rabbits was subject to only a small fine.

Poor people could not afford spices. Their foods were more often flavored with onions, garlic, and herbs like parsley and sage that they could grow in their garden or forage for in the fields and woods.

The more well-to-do would enjoy spices such as pepper, cinnamon, mace, nutmeg, saffron, grains of paradise, cloves, ginger, and galangal. Do some of those sound exotic? Grains of paradise are seeds that have a pepper-like flavor. Galangal is similar to ginger.

Spices were expensive! Wealthier people that had spices kept them locked up for safekeeping.

Experimentation with varieties of herbs and spices was not a well-established art: instead, spices were frequently used in combinations that would be unlikely for today’s palates. Spices were something of a status symbol, and the more you had, the more you used, and people were impressed.

Honey was the most common sweetener in the Middle Ages. Although sugar was available in many forms in medieval times, it was used sparingly as more of a spice than a sweetener, especially for meat sauces. If you think it’s gross to have sugar in your meat sauce, think for a minute about ketchup and barbeque sauce—both of those have plenty of sugar in them.

Well, I can’t read about medieval cookery without wanting to give it a try. This weekend I’m going to experiment with a medieval recipe and I’ll be sure to share the results with you.

April 3, 2014

Writing, Food, and Family History

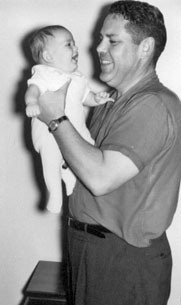

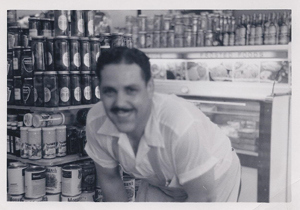

My dad inside his deli.

Sometimes writing triggers an unexpected trip down memory lane for me. Once in a while, these little side voyages are inspired by very simple things that still bring a wealth of almost-forgotten memories to light.

This happened to me recently while working on my second Sir Kaye book, The Lost Castle Treasure. It’s an adventure novel for kids set in medieval times. Without giving away any of the story, in one scene, a frightened Reggie is making a quick getaway from an unoccupied part of the castle and rushes headlong down the stairs. When he gets to the bottom of the last flight he trips over his own feet and goes rolling head over heels across the wide floor of a room that just happens to be the kitchen. Red-faced and out of breath, Reggie looks up and sees the castle cook and three kitchen boys staring down at him. The startled stares of the kitchen boys is interrupted by Abelard, who asks, “Well, Master Reggie, what brings you to the kitchen?”

Embarrassed, Reggie blurts out the only thing he can think of to explain his sudden arrival. “Do you have anything to eat?” he asks.

And that was the takeoff point for my trip down memory lane.

When I was a boy, all my neighborhood friends and I expended tremendous amounts of energy playing outside—exploring, bike riding, digging holes (another story), playing football, and hundreds of other things. When you use that much energy you just have to refuel. Frequently. So every few hours, one of our unfortunate mothers would discover several red-faced, grass-stained, mud-caked boys standing in her doorway and demanding, “Is there anything to eat?”

Although we tried to be fair and invade each house in turn, my house was generally the last on the list. In all the other homes there would be popsicles, Cheetos, moon pies—the usual junk food type snacks. In my house? A popsicle or a moon pie would be considered heresy! For a quick snack my mother would say to grab an apple or a banana or some other seasonal fruit we had on hand. And if we were really hungry, there was always a pan of kibbeh in the fridge, which I particularly loved—but my friends? Not so much.

I can see Reggie loving kibbeh too. It’s a middle eastern dish that I can only very simply describe as fried, stuffed meatballs made of spices, ground meat, and bulgur wheat. Here’s a recipe for kibbeh which might help explain it a little better, although my family’s recipe was slightly different. My grandfather put his own spin on it.

Both of my parents were excellent cooks and there was always a wide variety of different types of food available. At a very young age I experienced ethnic, even exotic foods that many adults at the time had never tried.

Outside the deli.

In the nineteen-forties and early fifties my dad owned and operated Edewinns Delicatessen in downtown Tulsa. In addition to the standard deli fare, he developed many of his own recipes. He was even granted a US Patent for an invention that he called “Cheez-Dillites,” which were big, hollowed-out, stuffed dill pickles. The patent was granted for the process he used to make them.

My mother loved to cook as well and had an almost uncanny ability to discern every ingredient (including spices) in whatever she tasted. She came by it honestly. Her father had been a master chef in his younger years. My grandfather emigrated to the US just prior to WWI and to his chagrin ended up a cook in the US Army during the war. In the 1920’s and 1930’s—during the Great Depression—he was always able to find work as a chef in some of the finest hotels and restaurants in the northeastern United States. By the time I was born he was semi-retired and owned a chain of stores in Battle Creek Michigan—it’s amazing what talent and a lot of hard work can get you.

When it comes to food today, some parts of the world have an abundance, with access to practically anything a person could want for most of the year thanks to refrigeration and fast transportation. We can buy fresh cherries at the grocery store in January, and winter greens all summer long.

But what about during medieval times, when food choices depended more on seasonal availability and there were limited ways to store and transport food?

Since food is an important part of the Sir Kaye series (just ask Reggie!), I wanted to have a better understanding of food and cooking in the Middle Ages. How did they manage without refrigeration? What kinds of food and spices did they consider staples? What were some of the common recipes of the time?

In next week’s blog I’ll share some of what I’ve learned about food in the Middle Ages and I will even try my hand with one of Reggie’s favorite recipes—meat pie. I’m confident that, unlike my boyhood neighbors, you’ll enjoy what I’ve cooked up for us.