Don M. Winn's Blog, page 27

March 27, 2014

Irregular Bedtimes Linked to Behavioral Problems in Children

Did your parents ever send you to bed early as a punishment for acting up? Their instincts were definitely focused in the right direction, although it turns out that the key to helping kids with certain behavioral issues is for parents to set and enforce consistent early bedtimes. A recent study in the UK showed that irregular bedtimes for growing children disrupt natural circadian rhythms in the body, cause sleep deprivation, undermine brain maturation, and can blunt a child’s ability to regulate certain behaviors.

Did your parents ever send you to bed early as a punishment for acting up? Their instincts were definitely focused in the right direction, although it turns out that the key to helping kids with certain behavioral issues is for parents to set and enforce consistent early bedtimes. A recent study in the UK showed that irregular bedtimes for growing children disrupt natural circadian rhythms in the body, cause sleep deprivation, undermine brain maturation, and can blunt a child’s ability to regulate certain behaviors.

The study included data from more than 10,000 children ages three, five, and seven years. Parents and teachers provided additional information regarding behavioral patterns.

As children progressed through early childhood without a regular bedtime, their behavioral scores worsened in the following areas:

hyperactivity

conduct problems

peer-related problems

emotional difficulties

The study showed that the effects of irregular bedtimes are cumulative over a period of years. The effects build up incrementally, causing increasingly severe behavioral issues at home and in school.

This study also puts a fine point on something important: behavioral challenges are not always a call for medication. Healthy, consistent, comforting routines at home have a great deal of influence on childhood behavioral issues.

Professor Yvonne Kelly (UCL Epidemiology and Public Health) states that “not having fixed bedtimes, accompanied by a constant sense of flux, induces a state of body and mind akin to jet lag and this matters for healthy development and daily functioning.”

On a positive note, the findings suggest that the effect is reversible. Children who had previously had haphazard bedtimes showed clear improvements in their behavior once parents established consistent bedtimes and positive bedtime routines.

Lap reading is a great way to create a positive bedtime experience with children. Developing a nightly habit of spending a few minutes together considering favorite stories will help children not only form loving bonds, learn vocabulary and reading skills, but can also help them develop a positive attitude about regularly going to bed at a healthy hour.

March 20, 2014

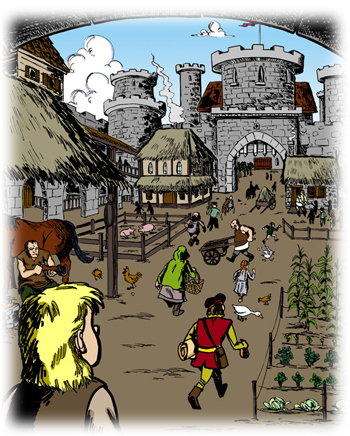

Medieval Castles – Interview with Bob Lawson, Curator of Ferniehirst Castle in Scotland

When writing a book about a 12-year-old medieval knight, sooner or later, you have to learn about castles. I’ve discovered some fascinating things about castles in my research, but unfortunately, castles are in short supply on this side of the pond. That’s why I’m so pleased to share a recent interview with author and castle expert Bob Lawson, curator of Ferniehirst Castle in Scotland.

I became interested in castles and castle design when writing my Sir Kaye novel, but of course the castles in my book are imaginary. Could you tell me a little about some of the real castles you have visited? Well, here in Scotland we have Stirling and, of course, the famous Edinburgh Castle. Another example would be Caerlaverock Castle (pictured left), which is a massive, triangular-shaped fortress with a drawbridge and water filled moat built on the marshes near Dumfries. It was the seat of the powerful Maxwells, built to guard the western marches on the border between Scotland and England. In England many examples survive that resemble the Balfour Castle in your stories. Windsor and Durham are two of the great Norman fortresses in England, while the castles of Wales offer Harlech and Pembroke—to mention only two of some of the finest castles still standing.

Well, here in Scotland we have Stirling and, of course, the famous Edinburgh Castle. Another example would be Caerlaverock Castle (pictured left), which is a massive, triangular-shaped fortress with a drawbridge and water filled moat built on the marshes near Dumfries. It was the seat of the powerful Maxwells, built to guard the western marches on the border between Scotland and England. In England many examples survive that resemble the Balfour Castle in your stories. Windsor and Durham are two of the great Norman fortresses in England, while the castles of Wales offer Harlech and Pembroke—to mention only two of some of the finest castles still standing.

The Knox castle was built on top of an old motte-and-bailey type castle. Have you visited any real castles that were built on top of a previous structure? What can you tell us about them?

Most of the great stone castles began as simple wooden motte-and-bailey towers. When David I began his Norman introductions into Scotland from England and from the French Cherbourg Peninsula during the 12th century, he granted lands to his trusted lords and barons. To defend their lands, these new landowners would construct wooden motte-and-bailey fortresses. (Note from Don: A motte-and-bailey fortress was a tall wooden fence built on top of a mound or hill—the motte. Around the bottom of the hill was a wide, deep ditch. Inside the fence was a tower, also called the keep. The bailey was the safe space inside the fence.) Of course as technology advanced, warfare and weaponry became more effective against these wooden structures, and so they were rebuilt using stone to strengthen their defenses. I expect most of the important castles in Scotland began life as wooden motte-and-baileys. The Normans—who were the great designers of stone castles—arrived here in Scotland at a later date than their 11th century campaign in 1066 to conquer England.

Are there any aspects of ancient castles and castle life that are still the same today in modern homes?

Yes, castles were always to a certain extent fortified dwelling houses with the emphasis on domestic life. Some had grand apartments designed for day to day living like those at Ferniehirst. These apartments include a garderobe or early toilet, guest bedrooms, kitchens, and pantries just as we have today. Kitchen and flower gardens were also popular in medieval times. What would life be like today without our gardens? Indeed, some of the plants we may see every day—both edible and decorative— were introduced by our medieval horticulturalists.

Of all the castles that you’ve visited, which one is your favorite and why?

I have to say Ferniehirst (pictured below right). It’s beautiful, romantic, and has a fascinating, colorful history. First built in 1470 by Sir Thomas Ker of Smailholm, it was  constructed as a reivers lair right on the border between England and Scotland. The border lairds lived by riding into the English territory across the border and reiving (stealing) their goods and livestock—thus depriving any invading army of its food source. Of course much more than livestock would be stolen—the border lairds would also take people, who could be sold back to their own families! Ferniehirst was built on an important location right on the borderline so it quickly became a border fortress. Thomas’s son, Dand, who was a famous left-handed swordsman, strengthened the walls, developing the original tower into a compact but incredibly strong castle. When the English attacked the castle in 1523 it resulted in a fierce battle. The tower you see had been built deep within a dense wood, so it was a difficult task to bring guns through the trees, long bows were ineffectual, and the Scots were very good at hand-to-hand fighting. The Kers of Ferniehirst have truly inspired me as warriors, knights, and courtiers, so yes, I love my Ferniehirst best of all.

constructed as a reivers lair right on the border between England and Scotland. The border lairds lived by riding into the English territory across the border and reiving (stealing) their goods and livestock—thus depriving any invading army of its food source. Of course much more than livestock would be stolen—the border lairds would also take people, who could be sold back to their own families! Ferniehirst was built on an important location right on the borderline so it quickly became a border fortress. Thomas’s son, Dand, who was a famous left-handed swordsman, strengthened the walls, developing the original tower into a compact but incredibly strong castle. When the English attacked the castle in 1523 it resulted in a fierce battle. The tower you see had been built deep within a dense wood, so it was a difficult task to bring guns through the trees, long bows were ineffectual, and the Scots were very good at hand-to-hand fighting. The Kers of Ferniehirst have truly inspired me as warriors, knights, and courtiers, so yes, I love my Ferniehirst best of all.

How did you become interested in ancient buildings?

I was born and brought up in the Medieval city of Durham pictured below left) in the northeast of England. Who cannot be inspired by that wonderful place with its great cathedral and Norman castle high on a hill above its own natural moat, an ox bow bend of the beautiful River Wear? My mother also encouraged myself and my two brothers to take  an interest. She was passionate about history and when we took family holidays we would visit medieval churches, castles, and abbeys rather than spend every day on the beach. We always talked about what we had seen. Mum was a wonderful lady and my inspiration. When I was only seven, when asked what I wanted to be when I grew up my second choice was a history teacher. My first choice? An engine driver of course!

an interest. She was passionate about history and when we took family holidays we would visit medieval churches, castles, and abbeys rather than spend every day on the beach. We always talked about what we had seen. Mum was a wonderful lady and my inspiration. When I was only seven, when asked what I wanted to be when I grew up my second choice was a history teacher. My first choice? An engine driver of course!

If you could build your own castle today, what would it be like? How similar or different would it be from ancient castles and why?

Probably the most gigantic bouncy castle ever. Perhaps in this computer age of virtual reality I could try out lots of complex designs to build the ultimate medieval style fortress, in an attempt to improve on the grand designs of our Norman conquerors who really were the experts.

Anything else you would like to share about castles?

Yes, if you are offered an opportunity to visit some of the great medieval fortresses of Europe, jump at the chance. It’s fascinating living history. From the kitchens with their huge fireplaces to the great halls where kings and princes feasted and plotted while jesters and musicians entertained, right there in that same space, all those centuries ago—it is as close as you will ever get to time travel and will inspire your imagination! Here in Scotland—especially along the border where I live—there are castles and towers at every turn. Some are the reiving towers of the border lairds. Others are the ruins of huge castles built by kings and princes like those at Kelso, once a great royal palace built by King David I and called Roxburgh. Unbelievably, only a few stones remain, but the stories will live forever.

Visit Bob Lawson’s website for more information about Ferniehirst, the Fortress in the Forest. http://www.clankerr.co.uk/Ferniehirst.html

March 13, 2014

Medieval Castles Part I—Protection from Marauders

While working on my latest book, The Lost Castle Treasure, I realized that without a helpful visual aid, keeping track of a whole castle was going to be difficult. I actually had to design an entire castle—all three stories, including the basement (or dungeons), secret passages, spy nooks, royal apartments, barracks, stables, and so much more. This brought back memories of all the wonderful adventures I used to have in my very own castle when I was a boy.

Okay, I admit it was actually a cardboard box, but in my imagination it was a real castle. One of the games my friends and I would  play as kids was similar to tag with one big difference—the cardboard box, or castle, was the safe zone. Once we made it to the castle we were safe and nobody could touch us. Even in my imagination I recognized the importance of a castle for protection.

play as kids was similar to tag with one big difference—the cardboard box, or castle, was the safe zone. Once we made it to the castle we were safe and nobody could touch us. Even in my imagination I recognized the importance of a castle for protection.

In medieval times that was the sole reason for building large, heavily fortified castles—for protection from marauders or invaders. Keep in mind that this was before the advent of gunpowder and cannons, so well-built, well-provisioned castles could actually stave off intruders for months and even years. Modern castles (after the invention of gunpowder) became more of a status symbol than a protection.

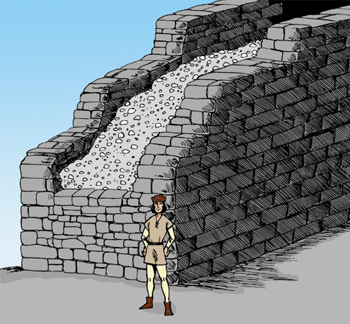

In this week’s blog I thought I would share a little bit of what I learned about the walls of castles built in the second half of the Middle Ages that made them so effective in providing protection.

A castle could have one or more walls as its first line of defense. These walls were built around the entire castle and were called curtain walls. The inner curtain wall surrounded the main castle buildings (living quarters, etc.). Often a second curtain wall was built surrounding the inner curtain wall with a good amount of space between the two curtain walls, although this plan was sometimes changed to suit the terrain. The height and thickness of curtain walls varied anywhere from 7 to 30 feet in thickness and anywhere from 30 to 40 feet in height.

Castle walls had to be built strong and were made of stone. The builders would dig a trench until they reached bedrock and then began construction of the wall. If the topsoil was too deep to find bedrock the builders would fill the trench with crushed stone. Why go through all of that extra work? To provide additional protection in case of a prolonged siege.

When a castle was under siege, attackers might start tunneling underground toward the castle wall. Being underground protected them from any arrows the castle’s defenders might shoot at them. As they dug, they braced the tunnel with wooden props so it wouldn’t fall in on them. When the tunnel was right under the castle wall, they would fill the end of it with straw and hay and pig fat and set it on fire. The fire would burn through the wooden supports and the tunnel would cave in. As the tunnel under the castle wall collapsed, many times part of the castle wall would fall down too, and the attackers could storm the castle. This is where we get the word “undermine.”

You’ll also notice from the illustration that the inside of the wall was filled with debris—like stones, mortar, etc. Some castles with very thick walls had stairs and passages (maybe even secret ones) built inside the walls that led to other levels of the castle.

You’ll also notice from the illustration that the inside of the wall was filled with debris—like stones, mortar, etc. Some castles with very thick walls had stairs and passages (maybe even secret ones) built inside the walls that led to other levels of the castle.

One other important point about castle walls is that there were no big windows opening to the outside of the curtain wall. Windows would make the castle vulnerable to attack so the only openings in the curtain walls were up high, beyond the reach of an attacker, and they were generally very narrow—just wide enough to allow archers to shoot through them. Of course, safely inside the curtain wall, it was not unusual for some of the castle buildings to have larger windows to let in light.

Next week I’ll be interviewing Bob Lawson about castles. Bob is the curator of Ferniehirst Castle, Scotland’s Frontier Fortress, and has written several books about the castle’s history. (http://www.clankerr.co.uk/)

March 4, 2014

Where Dyslexic Means Extraordinary – An Interview with Perry Stokes of the Rawson Saunders School

When I started elementary school way back in the 1960s, most educators knew almost nothing about dyslexia. An unfortunate result of this was that dyslexic children like myself were pigeonholed in a standardized learning environment that didn’t recognize the way we processed information. Not only did this make it very difficult to survive academically—let alone succeed—but it left its share of emotional scars along the way.

Last year I was stunned to discover a school in my own community that caters specifically to children with dyslexia. At the Rawson Saunders School, their motto is Where Dyslexic Means Extraordinary. I was so impressed by that because it’s such a positive, empowering motto! My inner 6-year-old was a bit jealous. I recently made the grand tour of the school and met several wonderful educators and a few of the extraordinary students as well.

Touring the Rawson-Saunders School with Mr. Perry Stokes, Director of Academic Language Therapy

Almost as soon as I heard of this school for the dyslexic, I started to wonder how Rawson Saunders is different from other schools. What can we learn from their methods? And so Perry Stokes, the Director of Academic Language Therapy at the Rawson Saunders School, has graciously agreed to answer a few questions for this blog. I hope you find the answers to the following questions as enlightening as I did.

What is Academic Language Therapy?

Academic Language Therapy, a systematic, multisensory, phonics-based approach to teaching reading, writing, and spelling, is offered to Rawson Saunders students daily in small groups. Basic Language Skills, an Orton-Gillingham based curriculum, serves as the foundation for the program, with instruction in phonemic awareness, letter recognition, decoding, spelling, fluency, comprehension, handwriting, vocabulary and oral and written expression. The daily schedule is composed of a comprehensive literacy instructional program. Instruction is individually paced and student progress is continually monitored.

Other programs and resources may be used by our experienced therapists to meet the individual needs of students. These include instructional strategies that assist students in gaining accuracy and fluency for effective reading and writing through work with Latin and Greek roots, reading fluency with advanced vocabulary in expository passages, and practice developing metacognitive strategies for reading and writing.

Students increase their reading, spelling and writing accuracy through explicit, systematic and multisensory instruction. ALTs collaborate with Language Arts teachers to ensure each student is successful. Mastery checks and reading benchmark assessments are given to continually monitor student progress. Homework is used to practice newly acquired skills and to develop accuracy and fluency in reading, spelling, handwriting, and written expression.

What kinds of tests do you do to evaluate a child’s need for language therapy?

Our students are professionally diagnosed with dyslexia. We utilize outside testing done by diagnosticians to provide us with a comprehensive psycho-educational battery of assessments. These tests can include tests of both ability and achievement such as the Woodcock-Johnson. These assessments can also include measures of a student’s sensitivity to the oral level of language such as the CTOPP (Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing).

What sorts of exercises do you do to assist children in therapy?

Inductive Teaching Methodology – the student is charged with discovering an auditory to visual component of the English language or a sound to letter correspondence such as how the long ā sound can appear as the letter pair ay, for example.

Multisensory Learning – the student is prompted to engage two sense pathways simultaneously of the visual, auditory or tactile/kinesthetic modalities. The students are prompted to look and name the letter pattern – ay “tray” /ā/ – or to hear and name the pattern – /ā/ is spelled with a final ay – or even to name and write during spelling tasks.

What ages do you usually work with?

Our campus currently serves students from grades first through eighth. As of the 2014-15 school year, we are excited to add high school grades.

What are some preliminary evaluations you can do at home?

Play “Ear Games” – rhyming, counting words heard in a sentence, counting syllables heard within a word, isolate the first/final sound heard in a word and segmenting a word into its constituent sounds.

Naming Activities – have the students name words that fit within categories, color words or animal words, for example.

If either of the above activities are halting, difficult and/or inaccurate for a child, there is an indicator of possible reading challenges.

At what age should you start to keep an eye on your child’s language progression and how does a parent know if there’s a need for intervention/assistance?

At the preschool /kindergarten ages

According to the International Dyslexia Association Fact Sheet entitled “Is My Child Dyslexic?” here are some indicators that a young child may be dyslexic:

Oral language

Late learning to talk

Difficulty pronouncing words

Difficulty acquiring vocabulary or using age appropriate grammar

Difficulty following directions

Confusion with before/after, right/left, and so on

Difficulty learning the alphabet, nursery rhymes, or songs

Difficulty understanding concepts and relationships

Difficulty with word retrieval or naming problems

What does language therapy have to do with dyslexia?

Academic Language Therapy is an instructional methodology specifically designed to meet the literacy needs of students diagnosed with dyslexia and a number of students diagnosed with general reading challenges.

What is the best thing a parent can do to help their dyslexic child?

The best thing that a parent can do for their dyslexic child is advocate for them to the fullest extent possible; to insist that they receive accommodations and the appropriate educational supports in their school environment.

Secondly, parents should encourage and commiserate with their dyslexic children. The reading process will be much more strenuous for them at times and that is unfair and maddening but the effort will be worth it. There are strategies they can learn to utilize that can help them tame the reading beast.

How do you (or Rawson Saunders) define success for a dyslexic student?

A dyslexic student is an extraordinary and potentially successful student regardless of reading proficiency. These students have amassed an impressive set of talents; designing, engineering, problem solving, innovative approaches, drama, art, science and free-form thinking. As the author and doctor Sally Shaywitz states, dyslexics have a sea of strengths around an island of challenge—reading.

Anything else you would like to share about your work with dyslexic students?

My work with dyslexic students is a mutually beneficial reciprocity; I am taught as much as I teach. We form a great teacher/student grouping.

Thank you so much for answering these questions. Your work is much appreciated!

About the school: Founded in 1997, Rawson Saunders is the only full-curriculum school in central Texas exclusively for dyslexic students and is recognized nationally as a leader in innovative teaching methods tailored specifically to the way dyslexics learn. The mission of Rawson Saunders is to develop the full—and tremendous—potential of children with dyslexia through an extraordinary education. Visit www.rawsonsaunders.org for more information.

February 27, 2014

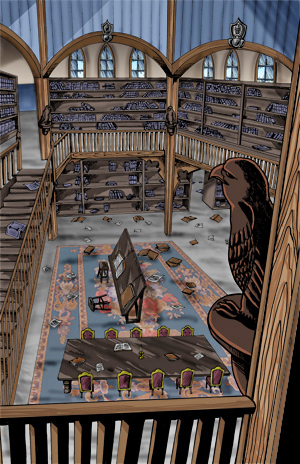

Medieval Storytelling: Books and Libraries

Depiction of a run-down medieval library interior from my current work in progress “Sir Kaye the Boy Knight Book 2: The Lost Castle Treasure” Artwork by Dave Allred.

I’ve invited medieval enthusiast Garrison Martt to share some information about storytelling in the Middle Ages. Last week I posted his answers to some of my questions about spoken-word storytelling; this week he talks about books and libraries in the Middle Ages. Again, he’s written it especially for kids, so feel free to use this information for teaching purposes.

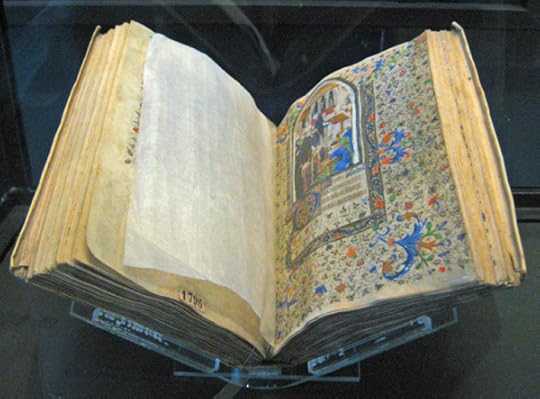

What were medieval books like?

Medieval books were all handmade, so each one was different. The covers were often made of leather or wood and may have been decorated with paint or gems. The pages were made from a thin form of leather known as vellum. Later books had paper pages.

Many books were religious, others included famous stories, poems or legends of the past. Many were written in Latin, others were written in the local languages of the time.

Were there libraries during the middle ages? Where were they? Who had them?

Medieval books were expensive, so they were usually purchased by the church or noble families. There were no public libraries. Many people could not read, even the people who owned books!

Those who could read might become teachers, physicians, geographers, astronomers, engineers or mathematicians. Reading was a doorway to the universe.

Would it have been likely for some nobles who valued books to have their own private libraries?

The church had monks who could create books. They also made many copies of books, each one by hand. A noble family would be more likely to purchase a book from a skilled bookbinder or a passing merchant. Private libraries included almost any kind of book that was available— because books were so rare.

If there was a 12-year-old boy who liked stories and could read a little bit and had access to books during the Middle Ages, what kinds of typical medieval books would he have been drawn to? (Obviously there were no

comic books).

comic books).A 12-year old boy who liked stories (and most do) who could also read (few could) and had access to books would read anything he could get his hands on! If it was me, I would try to get a copy of a 12th Century hit named the History of the Kings of Britain because it included some of the earliest written stories of King Arthur— that is, if I could read Latin.

Another medieval hit was the Song of Roland written in Old French, a great adventure about Charlemagne and his brave knights.

There were no comic books, however some books included illustrated pages of a particular scene. These were always great to see!

Note from Don: The picture to the above right is an illustration of the Tower of Babel from a book made in the late Middle Ages.

Garrison Martt likes to read and perform medieval stories for his friends. He is a lifetime member of the Austin Poetry Society and the director of the Past Poetry Project.

Medieval Book

February 20, 2014

Medieval Storytelling: The Spoken Word

Today I’m sharing a recent interview with Garrison Martt, a medieval storytelling enthusiast, about spoken-word storytelling traditions during the Middle Ages—roughly the 13th and 14th centuries. I hope you’ll find his responses as interesting as I did. I asked him to keep everything basic and kid-friendly so that parents and teachers could use this interview as a teaching tool for kids, but I’m sure parents and teachers will enjoy it as well.

What role did storytelling play in medieval society? How did kids view storytelling back then?

Storytelling was probably even more important in medieval society than it is now. There were no movies or television. There were no newspapers or radio to get the news. Most people learned about their world by telling each other about it. Story books were very rare, so kids would look forward to hearing stories even more than they do now!

Were there professional storytellers? Who were they, what were they called, and where, when, and how did they perform?

Professional storytellers were often people who traveled from town to town. Because they were very good at telling stories, they could receive food, lodging and items of value in exchange for the stories they would tell.

Every storyteller was different. Some storytellers could also sing or play a musical instrument or recite poetry. Each one had their own style.

There are different names for storytellers, depending on their skills and what country they came from. English or Welsh story tellers may have been known as bards while storytellers in Scandinavia may have been known as skalds. Musical storytellers in France may have been known as troubadours. I personally like the word “storyteller,” which everyone knew.

Medieval storytellers would seek out noble families with a castle or a large country manor, people who could reward them for their stories. A good storyteller always had an honored place by the fire or near the dinner table. They were welcome guests!

How could a person become a professional storyteller? Also, who were most likely to pursue this as an occupation?

Everyone grew up listening to storytellers, whether they were parents or neighbors or visitors. People became storytellers by listening and learning stories, then learning how to tell them in an entertaining way.

Some people may have become students of a master storyteller, the way that young people became squires to knights or apprentices to a successful merchant.

Everyone could be a storyteller. Those who were very good at doing this could become professional storytellers, however this could be a hard way of life because of the travel involved. Nobles in castles had a good place to live and would not leave. Local people with steady work would not leave their towns: the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker would stay home.

One form of storytelling is putting on plays— which are basically stories dramatized for others to watch. Medieval actors would band together in traveling groups, going from town to town to share their stories. A young person could join one of these groups to learn this trade.

There are many different words that are related to people who offered this kind of entertainment. What are the differences between minstrels, bards, and other names for storytellers?

This is a very hard question to answer— because the words for storytellers may vary from region to region and from different times in history. Generally speaking, bards include storytellers from the British Isles. Skalds include storytellers from northern European regions. Minstrels are musical storytellers from parts of central Europe which would have included modern day France and Spain. Minnesingers are performers from the parts of central Europe now known as Germany or Austria.

Garrison Martt likes to read and perform medieval stories for his friends. He is a lifetime member of the Austin Poetry Society and the director of the Past Poetry Project.

February 13, 2014

Saturday Morning Cartoons and Generations of Story Lovers

When I woke up last Saturday, I remembered something that I hadn’t thought about in years—Saturday morning cartoons. Memory is a funny thing; the oddest or most unlikely triggers can tease a remembrance from the brain. In this case, I woke up into a quiet moment at a specific time of day and as I realized it was Saturday, I had a sudden flashback, remembering the eagerness with which I woke up on Saturday mornings as a kid, looking forward to a full morning of cartoons. I loved the Jetsons and the Pink Panther and Spiderman and many others.

When I woke up last Saturday, I remembered something that I hadn’t thought about in years—Saturday morning cartoons. Memory is a funny thing; the oddest or most unlikely triggers can tease a remembrance from the brain. In this case, I woke up into a quiet moment at a specific time of day and as I realized it was Saturday, I had a sudden flashback, remembering the eagerness with which I woke up on Saturday mornings as a kid, looking forward to a full morning of cartoons. I loved the Jetsons and the Pink Panther and Spiderman and many others.

To be entirely honest, when I was a kid, Saturday morning cartoons were more of a treat than an expectation. I didn’t get to watch them very often as there were generally more important things I had to do. For instance, when I stayed with my great aunt, Saturday morning was always set aside for house cleaning. No matter how much I begged and pleaded (literally), she would always tell me the same thing, “You can watch cartoons after the work is done.” My argument that cartoons would no longer be playing by the time the work was done didn’t garner any sympathy from my great aunt. This is what my dad called “character building.” And I have to admit I was quite the character.

In any event, I do remember that my favorite forms of entertainment were times spent reading with my grandmother, and those rare occasions when I got to watch Saturday morning cartoons.

This memory made me think about how stories, in all their various forms, have been an integral part of our lives for generations. In my youth there was of course a generous supply of books (mainly from the library), but in addition to that there were movies and television programs that provided an endless source of entertainment— and that was with only 4 TV channels.

My dad’s generation also had many entertainment choices. He loved to read, for one thing, but I remember him describing how as a child, his family would sit around a large box with a speaker (I think they called this piece of antiquity a radio) and would stare transfixed at it as stories would be dramatically narrated— often with sound effects too.

My dad’s generation also had many entertainment choices. He loved to read, for one thing, but I remember him describing how as a child, his family would sit around a large box with a speaker (I think they called this piece of antiquity a radio) and would stare transfixed at it as stories would be dramatically narrated— often with sound effects too.

Today’s generation seems to be overloaded with entertainment choices. The four basic television broadcast channels have been replaced by hundreds of 24/7 cable channels, including on demand channels where you can watch practically anything you want anytime you want. I can’t tell you the last time I turned on the TV at 3:00am to find only a test pattern. And my seven-year-old self is a little jealous that today there are channels that broadcast nothing but cartoons all day long. (Speaking of which, do they still have Saturday morning cartoons? Please let me know, I keep forgetting to check.)

We are no longer limited to print copies of our favorite books. With the millions of mobile devices available, we can download just about any book, audio book or favorite television program or movie for reading or viewing on the go. The availability and technology of entertainment has made amazing progress from generation to generation.

But what about the generations before my dad’s and even way back before the technology of the printing press made books accessible to ordinary people? As part of my ongoing research into the lives and times of the Middle Ages for my Sir Kaye novels, in the next few blogs I’ll be interviewing Garrison Martt. Garrison is a medieval storytelling enthusiast who will give us a brief overview about what stories, books, libraries, and literature were like in (roughly) the 13th and 14th centuries.

February 6, 2014

Everyone Fails at First

As a child who struggled mightily to learn how to learn, and then struggled especially hard when it came to learning how to read and write, I well know what failure feels like. It was my constant companion in youth. These experiences are the bedrock of the fellow feeling I have for my young readers who face the difficulties of learning and growing up in a complex world. However, those who deal with dyslexia and other learning challenges are the ones for whom I have deepest compassion.

As a child who struggled mightily to learn how to learn, and then struggled especially hard when it came to learning how to read and write, I well know what failure feels like. It was my constant companion in youth. These experiences are the bedrock of the fellow feeling I have for my young readers who face the difficulties of learning and growing up in a complex world. However, those who deal with dyslexia and other learning challenges are the ones for whom I have deepest compassion.

When we struggle to learn, our internal dialog often features repetitive, negative messages like “I’m stupid,” and “I can’t do anything right.” These stories we tell ourselves (about ourselves) are so powerful that it actually programs us to fail. After all, if I know in my heart that I’m a failure, what else can I do but fail?

Can changing the way we view the stories of our lives really make a difference? Dr. Timothy D. Wilson of the University of Virginia says it can. He observes that if we can train ourselves to believe something good about ourselves—that we are more capable, smarter, socially comfortable, etc.—we make space in our mind for those profound changes to actually occur.

Wilson elaborates on the power of revising our story here. In short, he describes a group of college students who were struggling with their coursework. Their stories boiled down to “I’m bad at school,” or some other equivalent. Those beliefs led to self-defeating cycles that seemed impossible to break.

But then Dr. Wilson introduced them to a new story: Everyone fails at first. The story was illustrated by videotaped interviews of other students, who had failed miserably at first in college, but who later improved. The intervention took a mere 40 minutes, but the results were life-changing.

Those who were helped to ‘edit’ their story improved their grades and were more likely to stay in college. Those in the control group who stayed stuck in their original story of ongoing failure were most likely to drop out.

Our take-away as parents and educators: when kids get frustrated because of failing a task the first time (or the first 100 times), share this message with them. Share stories of times you failed the first time you attempted a new task, and how difficult the feelings of frustration were. Describe how you made improvements and eventually succeeded. Help them believe that they can improve, and that they are indeed good enough, by showing them that you believe in them. Help them change their internal story from “I’ll never succeed,” to “Someday I will succeed.” Teach them that “failure is not a permanent condition” and that it’s a gift “to be willing to fail, to be wrong, to start over again with lessons learned.” (Some of the above quotes are taken from a great TED talk by Angela Duckworth about the importance of grit. It’s about 8 minutes long, so check it out if you have the time.)

January 30, 2014

Storytelling Techniques for Parents—Telling Family Stories

I frequently blog about the many benefits of lap reading. And recently I’ve devoted a blog or two to the benefits of storytelling – meaning parents taking time to simply tell their children stories out loud. One blog was about the cultural benefits of storytelling and its impact on children’s respect for parents. The other was about the value of telling children family stories and how it strengthens their emotional resources.

I frequently blog about the many benefits of lap reading. And recently I’ve devoted a blog or two to the benefits of storytelling – meaning parents taking time to simply tell their children stories out loud. One blog was about the cultural benefits of storytelling and its impact on children’s respect for parents. The other was about the value of telling children family stories and how it strengthens their emotional resources.

Telling kids family stories is great, but it’s not always the easiest thing to do after a long day of working. So here are a few ideas that might be helpful when it comes to telling young children family stories out loud during an official story time. (I use the word official because it’s important to remember that simple conversations with your children about past events provide many of the same benefits as a story told in a more traditional bedtime or campfire-type setting.)

Practice ahead of time. Even though your family stories are true and you don’t need to worry about creating the events of the story, take a little time to reflect on the family stories you are going to share. It might help to think of a simple outline for the story. Rehearse it mentally and have it ready before your kids put you on the spot by demanding a story.

Make the kids the heroes of the family story if it’s about something that happened in their lifetimes. Let them help you tell the story by sharing what they remember about those events. Sharing appropriate stories about family members your children know can also be very interesting for your kids.

Keep stories age-appropriate with regard to content of course, but also length. A three-year-old will do much better with a shorter story than a nine-year-old would enjoy.

Looking for inspiration?

Dig out your box of memories or a family photo album and tell your children stories about a certain photo or about an item from your box. They don’t have to be full-on stories with carefully-developed plots. Telling your young kids about the dog you had as a child and a few things that dog did will keep their interest. Little girls might just love to hear about the bridesmaid’s dress you wore in your friend’s wedding (even if you hated it).

Tell your kids about a family heirloom. What is it? Why is it special to the family? How did it come into the family. If you don’t have an heirloom available to show your kids, tell them about different objects that were special to the family in the past – even if they never attained heirloom status.

Talk about vacations from the past. If they were from before your children appeared on the scene, tell them where you went, why you wanted to go there, what you saw, what you loved about that place. If you talk about vacations that your children remember, they will still be interested in hearing their memories told from your point of view, and they will enjoy helping out with the telling.

Tell your child the story of today. This is a great exercise to help them learn how to put their memories into words. If you weren’t together for the whole day, tell your child what you think happened to them during the time you were apart (be goofy if you want) and let them correct you. (Or maybe they’ll like your version better, who knows?)

Other Storytelling Ideas

If you know a few words of a language different than the ones you and your children hear every day, sprinkle a few of them throughout your story. Your kids will probably enjoy guessing what they mean.

Suffer a memory lapse from time to time during your story. Let your kids fill in the blanks. You can keep things simple and stay in charge of the story by only asking them to remind you what something looked like or where something was. You don’t have to let them take over telling the whole tale. This is a great way to add some new interest to a story you’ve already told many times.

Making the effort to share personal stories and family histories with your child will pay off in big ways. You will become more relatable to your child and they will begin to understand who you are from different perspectives. Stories humanize us. When you aren’t afraid to show some vulnerability by sharing your moments of past embarrassment, you encourage your kids to be more open and honest and make them more comfortable about sharing their own less-than-perfect moments as they get older. (They also see that it’s possible to survive embarrassment.) When you tell the story of an event your children were part of, it helps them recognize that their stories are valuable. Stories connect us. They reinforce our sense of belonging to our tribe. And they create the sense of responsibility that comes with belonging.

January 23, 2014

The Power of Story Part Two—Benefits for Life

When parents make a habit of reading aloud to their children or telling their children stories, there are many immediate benefits. It helps them increase their knowledge, because they are free to devote all their attention to the content of the stories, not having to devote any of their brain’s bandwidth to the complex act of decoding the written word for themselves. It nurtures their creativity, because they must imagine the story’s scenes for themselves as they listen. It helps them develop their vocabularies and memories.

When parents make a habit of reading aloud to their children or telling their children stories, there are many immediate benefits. It helps them increase their knowledge, because they are free to devote all their attention to the content of the stories, not having to devote any of their brain’s bandwidth to the complex act of decoding the written word for themselves. It nurtures their creativity, because they must imagine the story’s scenes for themselves as they listen. It helps them develop their vocabularies and memories.

However, when parents tell their children family stories, a new level of benefits opens up to the children. These benefits will last them throughout their entire lives.

Telling children stories about family members and themselves helps kids see themselves and their family members as heroes of their own stories. It also gives them a personal history to carry with them wherever they go, which helps children develop a strong sense of family.

Elaine Reese, professor of psychology at the University of Otago in New Zealand and author of the book Tell Me a Story: Sharing Stories to Enrich Your Child’s World, says that “as they grow into teenagers, the kids who have a stronger store of these family stories are actually doing better in their psychological functioning. They’re less depressed [and] they’re able to cope better with stressful life events.”

Children love to hear about the time when Mom gave herself an unfortunate haircut as a child and how Grandma reacted to seeing it and how no one could fix it and Mom had to go to school for months with a bald spot. They love to hear about how when Dad was five he learned the hard way that he shouldn’t go off for a walk by himself because he got lost and one of the neighbors had to bring him home. They love to hear stories about themselves — how they went to the park and found a toy shovel someone had left behind and used it to dig for treasure. They will want to hear about the good times and bad times. For the stories about themselves, they will want to help tell the story.

The family stories you share with your children don’t always have to be part of an official story time. They don’t have to be about major life events. Sometimes telling family stories may actually feel like a simple conversation with your child. Even conversations about things that happened last week can count as family stories for kids — especially when your children contribute to the conversation/story. According to Reese, “these small stories are every bit as beneficial for your child’s development as the grand tales told around campfires…”

Reading and telling stories are wonderful ways to connect with children and to teach them, but telling family stories makes for even deeper connections. So don’t forget to share your family memories. They are part of you and your story. Give your children the opportunity to merge these memories into their own lives and to make your family stories a special part of their own story.