Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 22

December 8, 2011

Mary Dyer's husband: Anglican, Puritan, Antinomian, Quaker—or nothing?

© Christy K. Robinson

Everyone knows that in the end, Mary Dyer was a devout,fervent Quaker, and that the puritans of Bostonhanged her. Actually, there's no record of Mary's religious practices between1638 when the Dyers left Boston as members ofthe (puritan) Boston First Church,and 1657, when she returned from England as a Quaker believer.

However, no one mentions the spiritual values of herhusband, William Dyer. He loved his wife and supported her, but didn't appearto share her doctrines or disciplines at the end of her life. This timelineindicates that William knew what to say and when to say it, but that he waslikely a secular, non-religious man. This article is not a judgment on him,just a discovery of his religious influences and culture. You're free to makecomments about the Dyers at the end of this article.

The St. Denis church in Kirkby LaThorpe, Lincolnshire,

The St. Denis church in Kirkby LaThorpe, Lincolnshire, where William Dyer was baptized in September 1609.

This church probably had puritan, nonconformist ministers.1609-1624:William Dyer was born and raised in Lincolnshire,between Sleaford and Boston; Lincolnshire was a hotbed of nonconformistthought. His parents' church in Kirkby LaThorpe appears to have had puritan or nonconformist-type ministers, though I couldn't find specific names of theirvicars in searches. During that time, the Sleaford and Bostonchurches had separatist ministers; that is, super-conservative Anglicans who believedthat the Reformation from the Roman Catholic church hadn't gone far enough—theywanted to purify their church of Catholic influences. England's puritan/separatist minister of Boston St. Botolph's, Rev. John Cotton, had to go into hiding for a yearbefore he emigrated to Massachusetts,where the town was named after the English Boston.

1624-1633:William was apprenticed in London, and livedwith master Walter Blackborne in the St. Martin-in-the-Fields parish of Westminster. St. Martin's was notpuritan. One of the responsibilities of the master was to teach apprentices alltheir trade secrets, as well as bring up the teenage boys in education andspiritual matters.

St. Martin-in-the-Fields between 1666 and 1721,

St. Martin-in-the-Fields between 1666 and 1721, when it was rebuilt in a classical style that exists today.

Before 1644, St. Martin's was Church of England, not puritan.St. Martin's-in-the-Fields had(orthodox) Church of England ministers, not puritan. Thomas Mountford, D.D., vicar ofSt. Martin's-in-the-Fields from 1602-1633, "is commemorated as 'genuinusEcclesiae Anglicanae filius; a true sonne of the Church of England, I meane a true Protestant; he was as farrefrom popish superstition, as factious singularity, no more addicted to theConclave of Rome, than addicted to the Parlour of Amsterdam.'" [Parlour of Amsterdam = separatistpuritans]

1614-1637: Rev.James Palmer was St. Martin's-in-the-Fields curateor deputy under Dr. Mountford.

1632-1644:William Bray (died 1644) was an English clergyman, chaplain to [Anglican] ArchbishopWilliamLaud. Rev. Bray was vicar at St. Martin's-in-the-Fields before the Dyers emigratedto America.Rather than change his "brand" of religion, Rev. Bray lost his job during theCivil War when the puritan Parliamentarians forced him out.

1633: William andMary Dyer married, with the ceremony from the Book of Common Prayer, at St. Martin-in-the-Fields church, Westminster. (This is further evidence thatthe marriage was Church of England, as puritans married in homes, taverns, or other secular places with judges, with a prayer from clergy, so they wouldn't be corrupted by Church of England "popish" traditions.) William Dyer, now working as a master in his guild, livedin this parish, and was taxed here.

1634: The Dyers'firstborn son was born, christened, and buried at St. Martin's churchyard.

1635: Dyersemigrated to Boston, Massachusetts. All of Massachusetts was a puritan enclave. Therewere few Anglican ministers, and they were watched—when they met withdisapproval, they were sent back to England or out of the colony. Thecustom of the puritan churches in Massachusettswas for the elders to examine a person's life for evidence of salvation (goodworks and strict keeping of the biblical laws), and to hear the person'stestimony before deciding to admit a member. Women were not required totestify, but were sometimes allowed. They were admitted to membership withtheir husbands.

In December, William and Mary Dyer were admitted tomembership in (puritan) Boston First Church;their infant son Samuel was baptized there. Minister was the conservative Rev. JohnWilson, teacher was Rev. John Cotton, formerly of Bostonin Lincolnshire.William Dyer and his family had probably had visited Cotton's church in England.

1636-1637: Maryand probably William Dyer were involved with Anne Hutchinson's home Biblestudies and discussions. They, like the Hutchinsons and others, continued asmembers of Boston First Church,where services were held all day on Sundays, with a part-day on Thursday, the"lecture" day. Fast days, at which there were sermons and lectures, weredeclared to pray for deliverance from various famines, pestilence, plagues,etc. Church members did not missservices, or they could be fined.

1637: In March, alarge group of men signed a Remonstrance/petition about treatment of Rev.Wheelwright, who propounded the Covenant of Grace, in contrast with the otherministers said to be preaching the Covenant of Works.

1637: In March, alarge group of men signed a Remonstrance/petition about treatment of Rev.Wheelwright, who propounded the Covenant of Grace, in contrast with the otherministers said to be preaching the Covenant of Works.In November, William Dyer and many others were disfranchisedas freemen because of Wheelwright petition. I don't think they wereexcommunicated, though they were under "admonition," a form of churchdiscipline.

1638: Late March,many members of Boston First Churchwere banished from Massachusetts, and moved toPocasset, on Aquidneck Island (later called Portsmouth, Rhode Island).Anne Hutchinson was definitely excommunicated, but the rest of the group wereleft on the books of First Church, perhaps in the hope that they could be rehabilitatedand brought back into fellowship.

1638-40: OnAquidneck, there was no organized church group. Anne Hutchinson and others wereat prayer when the great earthquake struck on June 1, 1638 and was felt allover England.She said that the earthquake was the infilling of the Holy Spirit.

Some men at Portsmouthmet together to "prophesy," which may have included William Dyer. The group ofmen included Hutchinson adherents, Baptists, andother dissenters to the puritan leadership in Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies.Prophesying meant, to them, to share revelations from scripture, not to predictthe future.

When Boston sent three men toread a letter from Boston First Churchadmonishing the heretics, they were treated hospitably but the Rhode Islanders wouldnot hear the letter. Anne Hutchinson refused to acknowledge that Boston Firstwas even a "church," as defined by the Bible. The "church" is a body ofbelievers, not an organization or building.

1640: A school/meeting house

1640: A school/meeting house in southern Massachusetts

In 1640, Francis Hutchinson, Anne's son, asked to have hismembership removed from Boston First, but was refused. Three years later, atage 23, he was killed with his mother and younger siblings in an Indian attackon their Pelham Bay farm. Rev. Thomas Welde wrote of themassacre, "Inever heard that the Indians in those parts did ever before this, commit thelike outrage upon any one family, or families, and therefore Gods hand is themore apparently seen herein, to pick out this wofull woman, to make her, andthose belonging to her, an unheard of heavy example… Thus the Lord heard our groansto heaven, and freed us from this great and sore affliction…and hath (throughgreat mercy) given the Churches rest from this disturbance ever since; that weeknow none that lifts up his head to disturbe our sweet peace, in any of theChurches of Christ among us; blessed for ever bee his Name."

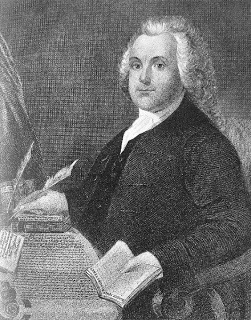

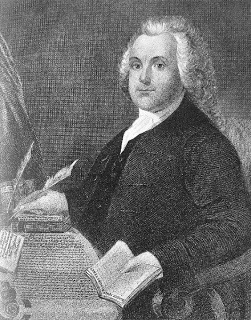

Rev. John Wilson

Rev. John WilsonOn March 30, 1640,Rev. John Wilson, senior minister, made the following statement in Boston First Church:

"Brethren you know the Businessof the Hand hath been a Long time propounded, it taken by the church into Considerationthat now we should draw to some Issue a determination you know the Cases ofthem there do much slander, some are under admonition that some underexcommunication: that some have given satisfaction in part to the church and dohold themselves still as members of the church y do yet hearken to us ^ seek togive satisfaction and others there be that do renounce the power of the church &do refuse to hear the church as Mr Coddington, Mr Dyar and Mr Coggeshall, the 2 first have been questioned in the church and dealt with andare under Admonition and have been so long, yet this add: of the church hathbeen so far from doing them any good, that they are rather grown worse underthe same, for Mr Coddington being dealt withal about hearing of excomunicatepersons prophecy, he was sensible of an evil in it, and said he had not beforeso well considered of it, yet since he hath not only heard such by accident asbefore. But [Coddington] hath himselfand our Brother Diar and Mr Coggeshall have gathered themselves intochurch fellowship, not regarding the Covenant that they have made with thischurch, neither have taken our advice and consent herein, neither have theyregarded it, but they have joined themselves in fellowship with some that areexcommunicated whereby they come to have a constant fellowship with them, andthat in a church way, and when we sent messengers of the church to them toadmonish them and treat with them about such offences, they were so far from expressingany sorrow or giving any satisfaction that they did altogether refuse to hearthe church. . . ." (Keayne,Prince Soc. 21, p. 400.) http://www.archive.org/stream/documentaryhisto02chap/documentaryhisto02chap_djvu.txt

Dr. John Clark, Baptist minister,

Dr. John Clark, Baptist minister, charter author, physician,

city co-founder. This portrait

was probably made in the 1650s.

He was close in age to William Dyer.1639-1650: Dr.John Clark and Mr. Lenthall held Baptist-type meetings in Newport but there was no church fellowship orbuilding per se for at least eightyears.

"Dr. John Clark and Mr. Lenthall held Baptist-type meetingsin Newport butthere was no church fellowship or building per se for at least eight years. Into the midst of these manyteachers of diverse religious views, Ezekiel Holliman, the Baptist, came earlyin 1640. He had in 1637/8 been called before the Massachusetts Court forseducing many with his religious teachings, had in 1638 or 1639 baptized RogerWilliams and been baptized by him, and had then removed to Aquidneck. He was in1640 the only man known to be a Baptist who was then residing on Aquidneck.There has not yet been discovered any evidence to show that any other of theAquidneck settlers were at that time Baptists or that the Baptist church laterfounded there had then been established. Callender in 1738 said: "Inthe mean Time Mr. John Clark, who was aMan of Letters, carried on a publick Worship (as Mr. Brewster did atPlymouth) at the first coming, till they procured Mr. Lenthall of Weymouth, whowas admitted a Freeman here August 6, 1640" (p. 62), and "It is said, that in 1644, Mr John Clark,and some others, formed a Church, on the Scheme and Principles of theBaptists. It is certain that in 1648 there were fifteen Members in full Communion."(p. 63.) In a footnote Callender gives thenames of some of them [notall]: "The Names of the Males were John Clark, Mark Lukar, Nathanael West,Wm. Vahan, Thomas Clark, Joseph Clark, John Peckham, John Thorndon, WilliamWeeden, and Samuel Hubbard." [NO DYER NAME THERE IN PARTIAL LIST.]"

There are no (discovered) christening records for the Dyerchildren (except Samuel in 1635 in Boston); the1637 anencephalic baby was stillborn and therefore could not be baptized; theremaining four children were born in Newport, Rhode Island. If the childrenwere baptized, they would have been teens of the age of consent to choose tofollow their Lord in baptism by immersion. I'm not sure of the Dyers' beliefsas young adults (except William Dyer Jr., who founded an Episcopalian church inDelaware),but many of their succeeding generations converted to Quaker beliefs.

In Rhode Islandrecords kept by William Dyer Sr., he refers to "Sunday," "First Day" and "theLord's Day," interchangeably. This could reflect that he was reporting thewording of others, or that it was what he called it himself.

1652-60: WilliamDyer did not convert to the Quaker beliefs of his wife Mary. For two of thenearly five years she was in England,William was doing what some perceived to be of low morals and deplorableethics: acting as a privateer (pirate with a license) in the First Anglo-DutchWar.

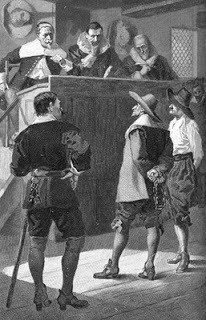

Gov. John Endecott (judge on left)

Gov. John Endecott (judge on left) presides at trial of Quakers in 1658. To

show respect, the Quakers were required

to doff their hats. They refused, which

served to enrage puritans further..1657-60: MaryDyer returns to New England, agitates with Quakers in Massachusettsand Connecticut, and teaches Quaker beliefs onShelter Island. She was hanged in Boston for civildisobedience on June 1, 1660, in support of liberty of conscience. She wasprotesting the torture and imprisonment of Quakers and their sympathizers—thosewho had simply offered Christian hospitality and humanitarian relief totraveling Quakers.

1662-63: The royal charterfor Rhode Islandgranted liberty of conscience, including the right not to worship and pay mandatory tithes to churches. Because William'sname appears on this charter several times, each time last in the list of men,I suggest (but can't prove) that he was one of the men who drafted the documentthat was given to Parliament and Charles II to be finalized. The bold words andphrases show that religious and civil matters were separate, and that eachperson was free to exercise religious beliefs as they thought best—and thatsome people cannot in conscience conform to the public exercise of religion,nor should they be punished or persecuted for religious differences that don'tdisturb the civil peace. In other words, the right to participate or not.

…witha full libertie in religiousconcernements; and that true piety rightly grounded upon gospellprinciples, will give the best and greatest security to sovereignetye, and willlay in the hearts of men the strongest obligations to true loyaltye: Now knowbee, that wee beinge willinge to encourage the hopefull undertakeinge of ouresayd lovall and loveinge subjects, and to securethem in the free exercise and enjovment of all theire civill and religiousrights, appertaining to them, as our loveing subjects; and to preserve untothem that libertye, in the true Christian ffaith and worshipp of God, whichthey have sought with soe much travaill, and with peaceable myndes, and loyallsubjectione to our royall progenitors and ourselves, to enjoye; and because some of the people and inhabitantsof the same colonie cannot, in theire private opinions, conforms to thepublique exercise of religion, according to the litturgy, formes and ceremonyesof the Church of England, or take or subscribe the oaths and articles made andestablished in that behalfe; and for that the same, by reason of the remotedistances of those places, will (as wee hope) bee noe breach of the unitie andunifformitie established in this nation: Have therefore thought ffit, anddoe hereby publish, graunt, ordeyne and declare, That our royall will andpleasure is, that noe person within thesayd colonye, at any tyme hereafter, shall bee any wise molested, punished,disquieted, or called in question, for any differences in opinione in mattersof religion, and doe not actually disturb the civill peace of our sayd colony;but that all and everye person and persons may, from tyme to tyme, and at alltymes hereafter, freelye and fullye haveand enjoye his and theire owne judgments and consciences, in matters ofreligious concernments, throughout the tract of land hereafter mentioned;

1670: WilliamDyer wrote to King Charles II. William wasunderstandably bitter about the conservative puritan government he'd experiencedunder Massachusettsrule, and how they'd interfered and harassed hundreds of people over the years,driving some to suicide, others to banishment, others to grievous bodily injuryand execution. He wrote of the Massachusettstheocratic government, "The thoughts of whichboundless possessions might swell them of the Massathusets Colony into anambitious concept of being absolute Lords and Proprietors of a Great Empire,and so arrogate to themselves a Liberty of prescribingLaws, and exercising their Dominion over all the Inhabitants of New-England." [Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut,and Rhode Island.]

1676: WilliamDyer died at about age 67 in Newport, Rhode Island. Noevidence found (yet) that he participated in church or religious activities. Hewas buried in the Dyer burial ground, probably next to the remains of MaryDyer, their son Maher, and others.

Published on December 08, 2011 23:00

December 1, 2011

Top 10 Things You May Not Know About Mary Dyer

© Christy K. Robinson

17th-century painting of Catholic Spaniards

17th-century painting of Catholic Spaniards hanging Dutch Protestants. This is the type

of gallows used in Mary Dyer's time.Mary Dyer was hanged, but not for "being a Quaker." I know, that's what most of the genealogy websites—and Wikipedia, and countless opinions and feature articles say. But it's not true. Thanks to the Quaker missionaries from England, there were hundreds of Quaker (Religious Society of Friends) converts in New England in the late 1650s and early 1660s. They were subject to persecution and physical torture (imprisonment in wet or freezing jail cells, topless whipping for men and women, having ears notched or sliced off, tongues bored through, being dragged from town to town, put in stocks, fined heavily and/or their possessions confiscated, banished) because they represented anarchy to the church-state government formed by the Massachusetts Bay founders. It also happened in England, and for the same reason—fear of anarchy to established traditions and government. Not one Quaker was hanged for religious beliefs or "being a Quaker," but because they were intentionally disobedient to anti-Quaker laws.You can see by Mary's letters to the Massachusetts court that she was ready for heaven, that she was appalled at their cruelty and wickedness, and that she chose to die. [image error] Martin Luther King Jr. and Ghandi

also practiced civil disobedience

to change the world.Mary Dyer committed civil disobedience. The four who were hanged, including Mary Dyer, actually chose to die, rather than agree to permanent exile from Massachusetts and their preaching and religious support there. They were given the opportunity to leave—and live—and chose instead to take a stand for liberty of conscience in the hope that their deaths would be so shocking that the persecution would end. They were hanged for civil disobedience. Mary Dyer's letters to the Boston magistrates show that she was opposed to their "bloody" laws of religious intolerance and persecution, and that she rejected their conditional offer of release.

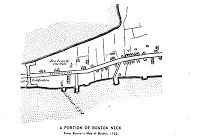

The strip of land that

The strip of land that connected Boston to the mainland.

The gallows were just outside

the fortification wall at the left.Not hanged on Boston Common. Nearly all accounts of Mary's and other "criminal" hangings say they were hanged on an elm tree on Boston Common, and their bodies were buried in a common grave (of Indians, thieves, paupers, etc.) now lost. This belief started more than a hundred years after Mary's 1660 execution. In M.J. Canavan's speech to the Boston Historical Society, published in the book, Where were the Quakers hanged in Boston? , he makes the case that executions in the 17th century were made just outside the fortification on Boston Neck, the isthmus that connected the Shawmut Peninsula to the Massachusetts mainland. It was about a mile's walk from the prison.Mary was educated, intelligent, well-bred, beautiful, wealthy. She was no timid wallflower. She was described as a woman "of no mean extract or parentage, of an estate pretty plentiful, of a comely stature and countenance, of a piercing knowledge in many things, of a wonderful sweet and pleasant discourse, so fit for great affairs, that she wanted [lacked] nothing that was manly, except only name and sex." Another writer said of Mary: "a Comely Grave Woman, and of a goodly Personage, and one of a good report, having a Husband of an Estate, fearing the Lord, and a Mother of Children." Mother of a "monster." Mary Dyer's third pregnancy ended in the premature stillbirth of a girl with anencephaly (having only a brain stem) and spina bifida deformities. Six months after it was buried, Governor John Winthrop ordered the exhumation and examination of the baby, calling it a monster, and proof of God's judgment on Mary's heresy to the puritan beliefs and lifestyle. In 1644, he published a book in England about Anne Hutchinson's heresy trial that described the Dyer baby's appearance. In the mid-1600s, there was an urban legend that women who preached, or even listened to a woman preacher, bore monsters. Mary bore eight children, six of whom lived to adulthood.

Mary Dyer was co-founder of two American cities. Many people believe that Mary Dyer was a Pilgrim who came to America on the Mayflower. Untrue! Stop it now! Though her name is not on the documents because as a woman she wasn't a "freeman" who could vote, Mary came to Boston in 1635 with her husband. In 1638, she was a pioneer who walked from Boston to Providence, Rhode Island, with her husband, small child, and other families connected with Anne Marbury Hutchinson. Mary's husband William Dyer signed the Portsmouth Compact that united the founders of the new colony, and he was among the purchasers of Rhode Island from the Indian sachems. One year later, Mary and William and others established the town of Newport, Rhode Island. Mary's husband was a fishmonger, milliner, surveyor, farmer, politician, militia captain, sea captain, and trader. William's apprenticeship in London had been to the professional guild, the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers, which had London mayors and council members among its alumni, but his first profession was milliner. A milliner was not a maker of fancy hats and bonnets, but a supplier of leather goods and accessories from Milan, Italy (Milan-er). William's apprenticeship in foreign trade, imports and exports, and merchandizing was probably the equivalent of a modern Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree! And it's probable that like a university student or intern, in his nine years of apprenticeship, William would have learned much about commercial fishing and its inspections and regulation. In New England, he was quickly put to work as a surveyor, trader, and administrator.Mary was married to a man of "firsts." Mary's husband, Captain William Dyer, was the first Secretary of State of Rhode Island, first Attorney General of Rhode Island (1650), and first Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas for New England (1652-53). He was also commissioned as an admiral, by Sir Henry Vane in England.

Mary Dyer was co-founder of two American cities. Many people believe that Mary Dyer was a Pilgrim who came to America on the Mayflower. Untrue! Stop it now! Though her name is not on the documents because as a woman she wasn't a "freeman" who could vote, Mary came to Boston in 1635 with her husband. In 1638, she was a pioneer who walked from Boston to Providence, Rhode Island, with her husband, small child, and other families connected with Anne Marbury Hutchinson. Mary's husband William Dyer signed the Portsmouth Compact that united the founders of the new colony, and he was among the purchasers of Rhode Island from the Indian sachems. One year later, Mary and William and others established the town of Newport, Rhode Island. Mary's husband was a fishmonger, milliner, surveyor, farmer, politician, militia captain, sea captain, and trader. William's apprenticeship in London had been to the professional guild, the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers, which had London mayors and council members among its alumni, but his first profession was milliner. A milliner was not a maker of fancy hats and bonnets, but a supplier of leather goods and accessories from Milan, Italy (Milan-er). William's apprenticeship in foreign trade, imports and exports, and merchandizing was probably the equivalent of a modern Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree! And it's probable that like a university student or intern, in his nine years of apprenticeship, William would have learned much about commercial fishing and its inspections and regulation. In New England, he was quickly put to work as a surveyor, trader, and administrator.Mary was married to a man of "firsts." Mary's husband, Captain William Dyer, was the first Secretary of State of Rhode Island, first Attorney General of Rhode Island (1650), and first Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas for New England (1652-53). He was also commissioned as an admiral, by Sir Henry Vane in England.

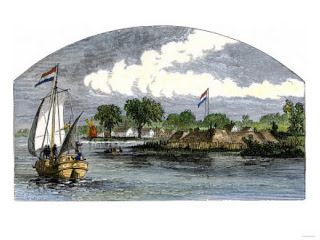

A Dutch trading ship at a fort near Hartford, Connecticut.Mary's husband was a privateer—a pirate with a license. Captain William Dyer (Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas) and Captain John Underhill (Commander-in-Chief Upon the Land) were commissioned, during the Anglo-Dutch War in 1652-53, to harass the Dutch traders and settlers occupying what's now known as Long Island, Manhattan, New York, and Connecticut. William's job was to take "prizes" of ships and their cargos, and split the profits with the United Colonies. As a result of the Dyer/Underhill ship and farm "takeovers" (or at least the imminent threat of them), the Dutch governor ordered a defensive wall built across the southern part of Manhattan Island. The wagon road that ran alongside the wooden palisade was called Wall Street. Wall Street is still the domain of raiders, 350 years later… Mary was staying in England during the time William performed these controversial acts.

A Dutch trading ship at a fort near Hartford, Connecticut.Mary's husband was a privateer—a pirate with a license. Captain William Dyer (Commander-in-Chief Upon the Seas) and Captain John Underhill (Commander-in-Chief Upon the Land) were commissioned, during the Anglo-Dutch War in 1652-53, to harass the Dutch traders and settlers occupying what's now known as Long Island, Manhattan, New York, and Connecticut. William's job was to take "prizes" of ships and their cargos, and split the profits with the United Colonies. As a result of the Dyer/Underhill ship and farm "takeovers" (or at least the imminent threat of them), the Dutch governor ordered a defensive wall built across the southern part of Manhattan Island. The wagon road that ran alongside the wooden palisade was called Wall Street. Wall Street is still the domain of raiders, 350 years later… Mary was staying in England during the time William performed these controversial acts.

Mary Dyer heard God's voice. In her twenties, Mary was a close friend and student of Anne Marbury Hutchinson, who claimed divine revelation and visions, and by doing so, incited the fury of the Boston Puritan leaders who believed that God only communicated in that way with men. Massachusetts Gov. John Winthrop said that Anne and Mary were "much addicted to revelations." When Mary studied Quaker beliefs in the 1650s, she learned that they called divine revelation the Inner Light. Evangelical and Pentecostal Christians today would recognize it as the Holy Spirit speaking to one's heart. Secular people would term it a conscience. To join hundreds of friends and descendants of Mary andWilliam Dyer in a discussion of their culture and experiences, join the Mary Barrett Dyer Facebook page, and follow http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com

Mary Dyer heard God's voice. In her twenties, Mary was a close friend and student of Anne Marbury Hutchinson, who claimed divine revelation and visions, and by doing so, incited the fury of the Boston Puritan leaders who believed that God only communicated in that way with men. Massachusetts Gov. John Winthrop said that Anne and Mary were "much addicted to revelations." When Mary studied Quaker beliefs in the 1650s, she learned that they called divine revelation the Inner Light. Evangelical and Pentecostal Christians today would recognize it as the Holy Spirit speaking to one's heart. Secular people would term it a conscience. To join hundreds of friends and descendants of Mary andWilliam Dyer in a discussion of their culture and experiences, join the Mary Barrett Dyer Facebook page, and follow http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com

Published on December 01, 2011 23:00

November 28, 2011

William Dyer, landed gentleman

© Christy K. Robinson

William Dyer was the son of a prosperous farmer in Lincolnshire. At age 14,he apprenticed to a master milliner in London,an international trader in fashion and leather accessories for men. His masteremigrated to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1633. William married MaryBarrett, and followed his master and several prosperous friends in 1635. In1637, he was one of many signers on a Remonstrance that was deemed seditious,and along with many Bostonfamilies, was ejected from the colony in early 1638. William was a co-founderof Portsmouth and Newport, Rhode Island.

In this article, you'll see how a farmer's second son became" William Dyre, Gent. ," a landed gentleman.

London, England

1633-35: WilliamDyer leased his former guild-master's home on Greene's Lane near River Thamesin Westminster; leased space in the New Exchangemarket on the Strand, for The Globe, amillinery shop.

Boston, Massachusetts

Modern Boston, with labels of where Hutchinsons, Winthrops, and Dyers lived in mid-1630s.

Modern Boston, with labels of where Hutchinsons, Winthrops, and Dyers lived in mid-1630s. 1635-36: Ownsland on Shawmut Peninsula (now central Boston) at Summer Street and Cornhill Rd., near Fort Hill;and owns 1/14th (7%) of Boston's town dock.

Rumney Marsh, MassachusettsJan. 1637:William Dyer granted 42 acres at Rumney Marsh, Saugus, Massachusetts,"bounded on the North with Mr. Glover, on the East with the Beach, on the Southwith Mr. Cole, and on the West with the highway." Click HERE for more on Rumney Marsh.

Rumney Marsh, MassachusettsJan. 1637:William Dyer granted 42 acres at Rumney Marsh, Saugus, Massachusetts,"bounded on the North with Mr. Glover, on the East with the Beach, on the Southwith Mr. Cole, and on the West with the highway." Click HERE for more on Rumney Marsh. From New England'sProspect, by William Wood, is this description of Rumney Marsh: Rumny Marsh, whichis 4 miles long and 2 miles broad; halfe of it being Marsh ground and halfeupland grasse, without tree or bush: this Marsh is crossed with divers creekes,wherein lye great store of Geese, and Duckes. There be convenient ponds for theplanting of Duckcoyes. Here is likewise belonging to this place divers freshmeddowes, which afford good grasse and foure spacious ponds like little lakes,wherein is store of fresh fish: within a mile of the towne, out of which runnesa curious fresh brooke that is seldome frozen by reason of the warmenesse ofthe water; upon this streame is built a water Milne, and up this river comesSmelts and frost fish much bigger than a Gudgion. For wood there is no want,there being store of good Oakes, Wallnut, Cædar, Aspe, Elme; The ground is verygood, in many places without trees, fit for the plough. In this plantation ismore English tillage, than inall new England, and Virginia besides; which proved aswell as could bee expected, the come being very good especially the Barly, Rye,and Oates.

Winter/spring 1638:William sells land—probably all his land—in Massachusetts Bay area before they move to RI, beingbanished as of the end of March.

DyerIsland in Narragansett Bay

Dyer IslandMarch 24, 1638:As the purchasers of Rhode Island (includingWilliam Dyer) sailed past a small wooded island in Narragansett Bay, Williamasked to be granted that island; it was named Dyer Islandafter him. Some small islands were used to contain goats or hogs; as thisisland has a lagoon, perhaps William used it for bird hunting or fishing. See thedepositions below, made in 1669, when he deeded the island to his second son.

Dyer IslandMarch 24, 1638:As the purchasers of Rhode Island (includingWilliam Dyer) sailed past a small wooded island in Narragansett Bay, Williamasked to be granted that island; it was named Dyer Islandafter him. Some small islands were used to contain goats or hogs; as thisisland has a lagoon, perhaps William used it for bird hunting or fishing. See thedepositions below, made in 1669, when he deeded the island to his second son.  Aerial view, Dyer Island

Aerial view, Dyer IslandSource: NOAADyer Islandis a low-lying 28-acre island situated approximately halfway between AquidneckIsland and the south end of Prudence Island. Despite its smallsize, Dyer Island's ecological value issignificant. It supports one of the last remaining salt marshes withoutmosquito ditches in Rhode Islandand is a nesting area for coastal shorebirds including the locally rare Americanoystercatcher. This uninhabited island also provides foraging habitatfor a variety of shorebirds and was found to support 47 species of seaweed – adiversity second only to Rose Island in the bay. InSeptember 2001, Dyer Island was acquired for preservation andincorporation into the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine ResearchReserve using state and NOAA funds. It will be used in perpetuity forresearch, monitoring,education, and passive recreation. (Source: http://www.eoearth.org/article/Narragansett_Bay_National_Estuarine_Research_Reserve,_Rhode_Island)

Mar 25, 1639: William'sshare of ownership of Bostondock conveyed to merchant (maybe Walter Blackborne, his former master?).

Portsmouth, Rhode Island 1638: There's a copyrighted photo of the lane leading to the Founders Brook where the first settlement

was made on Aquidneck Island. Land granted [Itt To Mr] Wm Dyre At the Cove by the marsh 6 Acres being [10] pole in bredth by 50

in Length y bounded round by the marsh.

Founders Brook Park memorials to

Founders Brook Park memorials to Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson,

Portsmouth, Rhode Island

Source: http://www.newportbristol.com/colony/FoundersBrook.html

Newport, Rhode Island

March 10, 1640, Williamhad 87 acres of land recorded to him at Newport.William Dyre having exhibited his bill under the Treasurer'shand unto the sessions held on the 10th of March, 1640, wherein appears fullsatisfaction to be given for seventy-five acres of land, lying within theprecincts of such bounds, as by the committee, by order appointed, did bound itwithal, viz.: To begin at the river's mouth, over against Coaster's Harbour,and so by the sea, to run up to a marked stake, at Mr. Coddington's corner, andso down, upon an easterly line to a marked tree over against the Great Swamp,and so two rods within the swamp, at the two deepest corners of the clear land,the one at the southeast corner, and the other upon a straight line in thenortheast, marked by stakes, and so down to a marked tree by the river side;the river being his bounds to the mouth thereof. with a home lot and a parcelof meadow and upland lying between Mr. Jeremy Clarke's meadow, and Mr.Jeoffrey's at the north end of the harbour, and north upon the highway, withten acres allowed by the town order for his travelling about the island, lyingwithin the former bounds, which is his proportion. "This, therefore, doth evidence and testify, that allthose parcels of land before specified, amounting to the number of eighty-sevenacres, more or less, is fully impropriated to said William Dyre and his heirsfor ever."

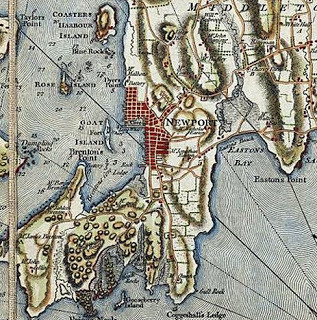

1650 map. Perhaps William Dyer

1650 map. Perhaps William Dyer was one of the surveyors who

reported to the cartographer.

1644: William buys30 acres adjacent to Dyer farm. Sells 10 acre neck of land to George Gardner. William recorded this about himself: "WmDyers farm [June or January] 20th 1644: Memorandum that the farm of WilliamDyre of Newport in the Isle of Rhodes consisting of all well the lands that wasgranted unto him by the said town as also of several purchases that he, saidWilliam, made of divers lands that adjoined hereunto amounteth to the number ofone hundred forty acres more or less."

1661: Land in Narragansett, called Misquamokuck (nowWesterly), was taken by William Dyer, Sr., Samuel Dyer, and MahershalalhashbazDyrer, and articles of agreement between an Indian captain and others weresigned by them. William Dyer was appointed to transcribe the deeds,testimonies, ratifications, etc. At a general meeting, February 17th, 1661-2,William Dyer was chosen surveyor of Misquamokuck. At the court held at Aquidneck,near Wickford, May 20th, 1671, the persons inhabiting here being called to givetheir encasement and desiring; to know whether or no the court, on behalf ofthe colony, do lay any claim to their possessions which they now inhabit, whichpersons were Mr. Samuel Dyer and others. To which demand this present court doreturn unanimously this answer: That on behalf of the colony this court do notlay any claims to their possessions which they now inhabit. (Source: http://www.archive.org/stream/somerecordsofdye00dyer/somerecordsofdye00dyer_djvu.txt)

1668-69: WilliamDyer surveys New Hampshire and Maine for geology andnatural resources before writing proposal to King Charles II. The proposal wasprinted in Londonin 1670.

1669: WilliamDyer may have become ill and put his estate in order, in the event he wouldn'trecover (he lived another seven years). Depositions were made that Williamowned Dyer Island. Dyer Island, off Portsmouth:(Source: http://www.archive.org/stream/documentaryhisto02chap/documentaryhisto02chap_djvu.txt)

Theaffidavits in regard to this gift follow: "Towhome these shall Concern I Testefy that the little Islandlying in the bay on the North Side of the wading River was given Mr Dyre by thePurchassers. 31 October 1650 Jno. Sanford.

IAttest that the above written Premisses were by my fathers Order and Comand byme written my father then being very sick and ill witness my hand the 4th ofOctober 1669 John Sanford.

I doafirm also that as wee past along by the afore-said Island the Purchassers gavethe said Island to Mr William Dyre. Nov. 1,1650 John Porter.

Thisis to Testefy that I Roger Williams being acquainted (by the good Providence ofGod) with the first Conception Birth and growth of Rhode Island (aliasAquednick) doe Asert and affirme as in the holy Presence of God, that bythe Consent of the first Purchassers ofRhode Island (Dead and liveing) the litle Island Comonly Called Dyres Islandwas from the first and allways (sometimes in Meriment) but always in Earnestgranted to be not only in Name but also in truth and reality the Proper Rightand Inheritance of Mr William Dyre of Newport On Rhode Island. Roger WilliamsAssista:" (R. I. L. E. I, 267., Po. R. 376.)

"CaptnRandall Houldon of Warwick in the Province of Rhode Islandiff Providence Plantation aged 57 years or thereabouts being Ingaged accordingto law Testefieth as followith That the Purchassers gave that litle Island Called Dyres Island to Mr William Dyresenior that was then one of us and further saith not. Taken the 24th day ofJune 1669."

"IDoe affirm that wee the Purchassers of Rhode Island (my selfe being the chief)William Dyre desireing a spot of land of us as we passed by it, after we hadPurchassed the said Island, did grant him Our Right in the said Island andnamed it Dyres Island. Witness my hand. October 18th 1669 William Coddington."

"IRichard Carder being a Purchassere doe own the above said writeinge: November:7th 1669 by me Richard Carder"

"WilliamCooley aged 66 years or thereabouts being Ingaged Testefieth that in the firstyear of the setling of this Plantation of Newport he being Master of a boat andJeffery Champlin and Richard Series being of his company, and stoping at theIsland Called Dyres Island mr William Dyre in Presence of them took posessionof the said Dyres Island and further saith not. Taken before me this 6th of December1669. John Green Assistant" (R. I. L. E. I, 267., Po.R. 346.)

1777 map of Newport, RI. The Dyer farm probably extended

1777 map of Newport, RI. The Dyer farm probably extended from Dyer's Point (now the Battery Park), north to the

land opposite Coaster's Island. 1669: WilliamDyer sold 12 acres of land to Peleg Sandford.

1670: Williamdeeds northern part of Newport Dyer farm to son Henry in Henry's 21styear. William directs properties to sons and money to daughters. July 25: Samueland Henry Dyer bind themselves to their father William Dyer to pay to theirsister Mary Dyer Ward, eldest daughter of William, £100 within three yearsafter the death of their father and to Elizabeth Dyer, second daughter ofWilliam by his second wife Katherine, the sum of £40 when eighteen years of age[1679].

William Dyre of Newport, ,Gent: granted to my sonn Henry Dyre into that part of my farme lyinge at thenortherly and thereof: to witt, from the Stone Ditch. as alsoe from the treewhere my sonn Mahers Tobacco house stood, from the Cave to and by that treeupon an Equidistante line from the said Stone Ditch downe unto and through theswamp unto mr. Coddingtons line by the brooke. (the fence is equally devided)percell of Land so bounded with a free Egress ingress and regress to andthrough the land of my sonn Samuels but in case my sonn Henry should have Issueonly Femailes then my sonn Samuell after the death of the said Henry shall Giveone hundred and fifty pounds starllinge the eldest to have a double portion therest an equall dividend of the Residue, but if only one all to her &cbesides the Valluation of the houssinge thereon built the Land to return to Samuell 7th day of July 1670. William Dyre. Wit The X marke off.

Robert Spinke

John Furnell

August 5, 1670: "WilliamDyre of Newport, gent.," deeded to "my sonWilliam Dyre...my island called Dyre's Island lying and being situated in Narrogansett Bayupon the northern side of Rhode Island overagainst Prudence Island."

1676: WilliamDyer dies at age 67, and farm is inherited by his sons; his two daughtersreceived financial bequests by 1679, as did his second wife Katherine. Sons: · SamuelDyer b. 1635 d. 1678, resided Kingston, RI with wife Anne Hutchinson Dyerand seven children, on lands granted by her father, Edward Hutchinson. Odd thatSamuel, as eldest son, wasn't deeded the Dyer properties at the same time ashis younger brothers. Yet, in 1687, his son Samuel sold his portion of the Dyerfarm to his uncle Charles Dyer. Probably Samuel Sr. automatically inheritedwhatever land his father hadn't deeded to other sons, when William Sr. died.Samuel Sr. died only a year or two after his father. · WilliamDyer Jr. b. 1640 d. 1688 (Customs official and Mayor of New York), resided Delaware. Williambequeaths Dyer Islandand large estates in Delaware and Pennsylvania to his sonWilliam Dyer and five other children.· MaherDyer, b. 1643 d. before 1670, resided Portsmouthand Newport. Hewas married for about five years, but his wife had no living children. · HenryDyer, b. 1647 d. 1689/90, resided Newport.Had two children.· CharlesDyer, b. 1650 d. 1709, resided Newportand Little Compton, RI. Charles Dyer moved from his farm in Little Compton to Newport to raise hischildren. Charles' will leaves the Newportfarm to his son Samuel and the house and its contents to his second wife Martha(who raised his five children after his first wife Mary died); after her deathit reverted to Samuel or his heirs. In addition, Charles said, "My earnest willand desire is (that) piece of ground that is now called the Burying Ground,shall be continued for the same use unto all my after generations that shallsee cause to make use of it, and I order that it shall be well kept fenced inby my son Samuel Dyre and his heirs forever."

1679: At the May12, 1679 court, "upon indictment by the General Solicitor against KatherineDyre of Newportfor misbehavior [apparently she sued Samuel Dyer's widow, Anne HutchinsonDyer], she being in court called, appeared: pleads not guilty and refers fortrial to God & the country. The Court upon serious consideration of thematter see cause to quash the bill." Katherine then sued her stepson CharlesDyer in 1682, in a £30 complaint of trespass, in which the jury found forCharles.

1687: Charles Dyre of Newport, Husbandman, boughtof [oldest brother Samuel's son] Samuel Dyre of Boston, carpenter, land in Newport,Bounded on the East, partly by certain lands in possession Mr. Francis Brinley& Left Collo of Peleg Sanford on the South, by land of Late Mr. NicholasEaston and Mr. Johnson the West, by the sea on North by land of HenryDyre.—with house, orchards, Gardens, meadows, woods, swamp--layed out unto mistressKatharine Dyre [his stepmother] by town of Newport 1681 as her Right of Dower.5 Oct1687. Witt. Weat Clarke, Robert Little, Daniel Vernon. (Source: Rhode Island Land Evidence 1648-1696 -Abstracts Vol 1page 206)

Click HERE for a view of what used to be the Dyer property of Newport, Rhode Island.

Published on November 28, 2011 05:00

November 24, 2011

A Christian Gives Thanks That America is Not a Christian Nation

This article appeared on Huffington Post religion page on 11/24/11.

A Christian Gives Thanks That America Is Not a Christian Nation

Parker J. Palmer Founder, Center for Courage & Renewal We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

--The Declaration of Independence

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof...

--First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

These foundation stones of American democracy were laid a century too late to save Mary Dyer's life. Dyer, a middle-aged mother of six, was hanged in 1660 for defying a Puritan law that banned Quakers from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Christians who cruelly deprived this woman of Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness were dead certain (so to speak) that they were on a mission from God, protecting their "divinely ordained" civic order against Mary Dyer's seditious belief in the Inner Light.

As a spiritual descendant of Mary Dyer, I'm profoundly grateful that America is not a Christian nation. If it were, my Quaker convictions might get me into very deep oatmeal. And as a Christian who does his best to take reason as seriously as I take faith, I find impossible to understand America as a "Christian nation" -- and I believe that there are vibrant possibilities in the fact that it is not.

Whatever America's founders believed about Christianity -- and they believed a wide range of things -- they clearly rejected the idea of an established church. That's strike one against the curious conceit that we're a Christian nation. If being a Christian nation means asking ourselves every day, "What would Jesus do?" about a political issue, then doing it, that's strike two. To take but one example (without forgetting things like slavery, justice for those who can afford it and peace through war):

As a Christian, I'm passionately opposed to American pretensions that we have special standing with God; to political office-seekers who play on our religious differences; and to the religious arrogance that says, "Our truth is the only truth." But I'm equally passionate about the urgency of creating a culture of meaning that responds to the deepest needs of the human soul. This is a task we have been neglecting at great peril, a task that demands the best of all our wisdom traditions, a task on which people of diverse beliefs can and must make common cause.

Viewed from this angle, the fact that America is not and cannot be a Christian nation is very good news. America's freedom of religion, and freedom from religion, offers every wisdom tradition an opportunity to address our soul-deep needs: Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, secular humanism, agnosticism and atheism among others. These traditions are like facets of a prism, each of which refracts a different wave length of the Light that overcomes darkness, including the darkness created from time to time by every nation and every tradition.

The philosopher Jacob Needleman has said that "one of the great purposes of the American nation is to shelter and guard the rights of all men and women to seek the conditions and the companions necessary for the inner search." In this society, where religious and philosophical diversity is one of our most precious assets, we can take a big step toward opening our culture to the "inner search" by shaking off the mistaken notion that this is code language for the search for God. Inner-life questions are the kind everyone asks, with or without benefit of God-talk: Does my life have meaning and purpose? Do I have gifts that the world wants and needs? Whom and what shall I serve? Whom and what can I trust? How can I rise above my fears? How do I deal with suffering: my own, that of my family and friends, and that of the larger world? How can I maintain hope? What does any of this mean in the face of the fact that I'm going to die?

These are not questions that yield to conventional answers. They are the big questions that must be "lived" so that we might "gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answers" (Rainer Maria Rilke).

Do our schools give young people a chance to wrap their lives around questions of that sort? Do our religious communities listen for the questions that are alive among us instead of answering questions that few are asking? Do we offer spaces of public life that are safe for vulnerable explorations of meaning, spaces that are not Roman arenas where demagoguery slays reflective, rational and factually grounded discourse?

American democracy gives us a chance to do all of that and more, free of ideological restraints. That's why I'm grateful that America is not and cannot be a Christian nation. Of course, we can continue to have pseudo-theological food fights over questions like, "How can we save our nation by making all Americans into God-fearing souls?," or "How can anyone be so ignorant as to believe in God or the soul?" Or we can take advantage of the fact that American democracy offers us an open space in which to pursue questions of personal, communal and political meaning, illumined by multiple sources of light. Which will it be? That's a question worth wrapping our lives around, with gratitude for our political inheritance.

A Christian Gives Thanks That America Is Not a Christian Nation

Parker J. Palmer Founder, Center for Courage & Renewal We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

--The Declaration of Independence

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof...

--First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

These foundation stones of American democracy were laid a century too late to save Mary Dyer's life. Dyer, a middle-aged mother of six, was hanged in 1660 for defying a Puritan law that banned Quakers from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Christians who cruelly deprived this woman of Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness were dead certain (so to speak) that they were on a mission from God, protecting their "divinely ordained" civic order against Mary Dyer's seditious belief in the Inner Light.

As a spiritual descendant of Mary Dyer, I'm profoundly grateful that America is not a Christian nation. If it were, my Quaker convictions might get me into very deep oatmeal. And as a Christian who does his best to take reason as seriously as I take faith, I find impossible to understand America as a "Christian nation" -- and I believe that there are vibrant possibilities in the fact that it is not.

Whatever America's founders believed about Christianity -- and they believed a wide range of things -- they clearly rejected the idea of an established church. That's strike one against the curious conceit that we're a Christian nation. If being a Christian nation means asking ourselves every day, "What would Jesus do?" about a political issue, then doing it, that's strike two. To take but one example (without forgetting things like slavery, justice for those who can afford it and peace through war):

"If [America] is going to be a Christian nation that doesn't help the poor, either we have to pretend that Jesus was just as selfish as we are, or we've got to acknowledge that He commanded us to love the poor and serve the needy without condition and then admit that we just don't want to do it." --Stephen ColbertIf a Christian nation is one whose popular culture is dominated by Christian convictions about what's good and true and beautiful, I'm afraid that's strike three. Just look at the fact that our nation-wide Christmas festivities begin on Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving, a day that celebrates consumerism, our true civil religion. And if anyone wants a fourth swing of the bat in hopes of getting on base, let me pitch this brief theological reflection. If, as Christians believe, God is the Creator and Redeemer of All, then there's no way God favors Americans above people of other nationalities. Strike four.

As a Christian, I'm passionately opposed to American pretensions that we have special standing with God; to political office-seekers who play on our religious differences; and to the religious arrogance that says, "Our truth is the only truth." But I'm equally passionate about the urgency of creating a culture of meaning that responds to the deepest needs of the human soul. This is a task we have been neglecting at great peril, a task that demands the best of all our wisdom traditions, a task on which people of diverse beliefs can and must make common cause.

Viewed from this angle, the fact that America is not and cannot be a Christian nation is very good news. America's freedom of religion, and freedom from religion, offers every wisdom tradition an opportunity to address our soul-deep needs: Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, secular humanism, agnosticism and atheism among others. These traditions are like facets of a prism, each of which refracts a different wave length of the Light that overcomes darkness, including the darkness created from time to time by every nation and every tradition.

The philosopher Jacob Needleman has said that "one of the great purposes of the American nation is to shelter and guard the rights of all men and women to seek the conditions and the companions necessary for the inner search." In this society, where religious and philosophical diversity is one of our most precious assets, we can take a big step toward opening our culture to the "inner search" by shaking off the mistaken notion that this is code language for the search for God. Inner-life questions are the kind everyone asks, with or without benefit of God-talk: Does my life have meaning and purpose? Do I have gifts that the world wants and needs? Whom and what shall I serve? Whom and what can I trust? How can I rise above my fears? How do I deal with suffering: my own, that of my family and friends, and that of the larger world? How can I maintain hope? What does any of this mean in the face of the fact that I'm going to die?

These are not questions that yield to conventional answers. They are the big questions that must be "lived" so that we might "gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answers" (Rainer Maria Rilke).

Do our schools give young people a chance to wrap their lives around questions of that sort? Do our religious communities listen for the questions that are alive among us instead of answering questions that few are asking? Do we offer spaces of public life that are safe for vulnerable explorations of meaning, spaces that are not Roman arenas where demagoguery slays reflective, rational and factually grounded discourse?

American democracy gives us a chance to do all of that and more, free of ideological restraints. That's why I'm grateful that America is not and cannot be a Christian nation. Of course, we can continue to have pseudo-theological food fights over questions like, "How can we save our nation by making all Americans into God-fearing souls?," or "How can anyone be so ignorant as to believe in God or the soul?" Or we can take advantage of the fact that American democracy offers us an open space in which to pursue questions of personal, communal and political meaning, illumined by multiple sources of light. Which will it be? That's a question worth wrapping our lives around, with gratitude for our political inheritance.

Published on November 24, 2011 11:54

November 18, 2011

The tragedy of John Winthrop's widow

John Winthrop's fourth wife, Martha Rainsborough

© Christy K. Robinson

John Winthrop, 1588-1649 Why would I steal time from writing my historical novel onMary and William Dyer, to write an article about the fourth wife of GovernorJohn Winthrop of Massachusetts?She had no connection to the Dyers that I've ever seen. But in clearing up a(

gasp!

) mistake I found in a biography of Winthrop,I found a window into New England in 1650s Boston that sheds some light on theenvironment and culture in which Mary Dyer moved, her last three years of life.

John Winthrop, 1588-1649 Why would I steal time from writing my historical novel onMary and William Dyer, to write an article about the fourth wife of GovernorJohn Winthrop of Massachusetts?She had no connection to the Dyers that I've ever seen. But in clearing up a(

gasp!

) mistake I found in a biography of Winthrop,I found a window into New England in 1650s Boston that sheds some light on theenvironment and culture in which Mary Dyer moved, her last three years of life.John Winthrop was married four times and had a tribe ofchildren, though more died as infants than lived to procreate. His first wife,Mary Forth, produced most of the surviving Winthrops, but she died in childbirth. Hissecond wife, Thomasine Clopton, died from childbirth complications one yearafter he married her. His third wife, Margaret Tyndall, was the love of JohnWinthrop's life, and though she had a number of pregnancies, only one or twogrew to adulthood. John emigrated to Massachusettsin 1630, and Margaret followed about 18 months later. Her last pregnancymiscarried in October 1637 on the eve of Anne Hutchinson's heresy trial—andAnne, a midwife, attended her! In fact, when Anne collapsed in exhaustion afterstanding all day at her trial, it was because she'd been up the night before,attending Margaret. Margaret was very much loved by her step-children, who wereyoung when she took over their care.

In 1643, John Winthrop's and Margaret Tyndall's son, Stephen,married Englishwoman Judith Rainsborough (remember that surname) and moved fromBoston back to England to eventually attain therank of colonel in the Parliamentary forces in their Civil War.

Martha Rainsborough (seven years older than her sisterJudith) and her husband, Captain Thomas Coytmore, had married in 1635 in England, and emigrated to Boston in 1636. They settled in Charlestown, where Thomas was both amiller—and apparently a sea captain for his father, who was part of the EastIndia Trading Company. In case of his death, Thomas made a trust for his son,which was arranged by Rev. Increase Nowell.In 1644, Captain Coytmore was lost at sea off Cadiz, Spain.The trust, then, provided an inheritance for the Coytmore boy: lands inCharlestown/Marden area, as far as I could determine.

[Winthrop'sbiography author had off-handedly identified Winthop's widow as Martha Nowell Cotymore, the "sister ofIncrease Nowell." I could only find a couple of references tying those namestogether, and that from highly-suspect, amateur genealogy pages. Besides, Ithought, why would her parents and many siblings be surnamed Rainsborough, but shewould be surnamed Nowell? Nope, just doesn't work for me. So I looked up the scantinfo on Coytmore and learned from a nineteenth-century Google Books volume thatThomas's mother had had two children from a first marriage, and his half-sisterParnell married the moderately-famous Rev. Increase Nowell, who was treasurerof Massachusetts Bay Colony. This made Mr. Nowell the half-brother-in-law ofThomas Coytmore, and no blood relation at all to Martha Rainsborough Coytmore,so give her back her true name! And PS: the author spelled it Cotymore, whichis incorrect.]

An unknown 17th-century

An unknown 17th-century widow of high status.

Back to Martha. After she was widowed, she moved to Boston, to a house on Cornhill Road.(From 1635-1638, William and Mary Dyer lived on the east of Cornhill Road.) Because the Rainsboroughs were well-known puritans in England, her youngersister had married John Winthrop's son, and because Cornhill was a majorthoroughfare in the small town of Boston,the Winthrops and Martha probably were acquainted.

Margaret Tyndall Winthrop fell victim to the yellow fever epidemicin New England (carried by African slaves via Barbados), and died June 14, 1647.She and John had been married for 29 years, and she was tenderly, devotedlyloved.

Six months after Margaret Winthrop's death, after December20, 1647, John married, as his fourth wife, Martha Rainsborough Coytmore, awidow with a young son. John was 59, she was 30. At this time, and in theircultural beliefs, Martha became the mother-in-law of her own sister Judith!(Seems creepy today, doesn't it?!) The Winthrop honeymoon must have lasted at leastthree months: Martha became pregnant in March.

John Winthrop apparently had several bouts of an unexplainedillness in 1648, and he was weak for more than a month in the autumn. His andMartha's baby son Joshua was christened in Boston'sFirst Church in December. John succumbed toillness on March 26, 1649, leaving 31-year-old Martha a widow again. John's propertieshad already been deeded to his adult sons, but as widow of the high-status Winthrop, and mother ofhis baby, she would have been treated with respect, and had some sort ofsettlement.

Col. Thomas Rainsborough,

Col. Thomas Rainsborough,Martha's eldest brother

Martha's oldest brother, Col. ThomasRainsborough, was killed at Pontefract Castle in October 1648;she would not have heard of it until at least February 1649, if a ship bravedthe winter storms with the news. More likely, the news would have come at aboutthe time of Winthrop'sdeath in late March.

At some point, Martha's Coytmore son died, and the Coytmore trustbecame her property. In 1651, Joshua Winthrop died at about two and a halfyears old. On March 10, 1652, Martha married John Coggan of Boston,a miller who had known her first husband, and they moved to Malden, Massachusetts.In 1658, Coggan died, leaving Martha a widow for the third time with nochildren, at age 41. (Being married and having children was a core belief ofpuritans, and now Martha was bereaved and alone, and her siblings were home in England.)

The next record I found of Martha was an account from Rev.John Davenport. The woman who had been the sister of military officers, and thewidow of two prosperous millers and a famous governor, was "discontented that she had nosuitors, and that she encouraged her farmer [either her farm manager, or atenant on her lands], a mean man, to make a motion to her for marriage, whichaccordingly he propounded, prosecuted, and proceeded in it so far thatafterwards, when she reflected upon what she had done, and what a change of heroutward condition she was bringing herself into, she was discontented,despaired, and took a great quantity of rats bane, and so died. Fides sit penes auctorem. [Faith is the responsibility of the Author.]"

Rats bane, native to New England

Rats bane, native to New EnglandOn October 24, 1660, aged 43, Martha Rainsborough CoytmoreWinthrop Coggan committed suicide. Rats bane is arsenic trioxide, and its usein homicide or suicide was primarily a woman's preferred, nonconfrontationalmethod. It might have been available to Martha through patent medicines (whichJohn Winthrop and his son John Winthrop Jr. were known to concoct and sell), oras a common treatment for syphilis. Or, most obviously, as a rat poison, tokeep the vermin out of their stored food supplies.

One author called poisoning "the mark of lethal andtreacherous intimacy, the most extreme violation of domestic order." PoorMartha. She couldn't stand living alone, but she wouldn't suffer such a fall asto be the childless, aging wife of a lowly farmer of poor regard, who onlywanted her for her property.

Lastly, we hear another word about Martha, in the Massachusetts Archives. Petition of Margaret Sheaffe to theGeneral Court, in 1662, for a title to the house and land of Martha, widow ofJohn Coggan (we suppose the Albion lot, on the corner of Tremont and Beaconstreets), for which Mrs. Sheaffe had paid the purchase money to Mrs. Cogganbefore the latter, having been left by the Lord "to Sathan's temptations, whichwas too strong for her, made away with herself."

That's the final judgment of the General Court underGovernor John Endecott, then: Martha was not worthy to be called the widow ofthe great Governor John Winthrop; and she was not of the Elect who would besaved in the kingdom of God, it being obviousthat the Lord had left her to Satan.

Published on November 18, 2011 20:17

November 13, 2011

Oooh, hate when that happens...

William Dyer and Mary Barrett lived in London/Westminster before theymarried in 1633. This is a Londonepidemiological table from 1632. This list was compiled by John Graunt, but his data came from"ancient matrons" who examined the bodies and interviewed thefamilies of the dead. Most of the ancient matrons were respected midwives licensed by the Church of England, whohad much more knowledge of the human body than did physicians.

Medical doctors had university theological training about the body, but nomedical school. If their patients were lucky, they had some observation and hands-on training from chirurgeons (surgeons). During witch hunts, both male and female healers were accused, imprisoned, and executed for their profession, because successful treatments may have been aided by the devil's intervention.

In this table, notice that 470 people died because of "teeth."

"Crisome" is an infant dying within its first month. The Dyers' first son William, born in October 1634, lived long enough to be christened, but was buried on the third day after birth.

"Consumption" may include tuberculosis, asthma, emphysema, blacklung, etc.

"Rising of the Lights" means lung disease, probably due to coal-smokeair pollution.

"French Pox" and doubtless some of the other mortality would beconsidered sexually-transmitted disease."King's evil" (fromthe belief that the king's touch would heal scrofula/tuberculosis)

Published on November 13, 2011 23:00

November 8, 2011

Heart-stopping meals of colonial New England

© Christy K. Robinson

What did 17th-century colonists eat? Pretty much anything! All of New England was in abuilding boom for years as immigrants arrived in the thousands. They oftenparticipated in house and building raisings, enjoyed the fellowship and featsof strength and skill, and what you'd call a "potluck."

What did 17th-century colonists eat? Pretty much anything! All of New England was in abuilding boom for years as immigrants arrived in the thousands. They oftenparticipated in house and building raisings, enjoyed the fellowship and featsof strength and skill, and what you'd call a "potluck."If you were to try cooking the dishes suggested in cookbooks of the time, you'd find no precise measurements. And by today's standards, many dishes would be considered heart-stoppers. The recipe for roast turkey or capon, particularly, calls for three major applications of butter! Many people never lived to see 50 years of age, even with active lives of outdoor work and traveling on foot.

At home, when it was just the family and servants, mostcolonists had porridge, bread, and a little meat when the family could affordit. But for feasts and social occasions, they ate well. For you foodies, here'stheir festival food, served at Sabbath meals or house raisings:

At home, when it was just the family and servants, mostcolonists had porridge, bread, and a little meat when the family could affordit. But for feasts and social occasions, they ate well. For you foodies, here'stheir festival food, served at Sabbath meals or house raisings: Meats: They made roasts and pies ofvenison, a variety of fish and shellfish, mutton, turkey, capon, swine,pheasant, pigeon, rabbit, squirrel, raccoon (as delicious as a lamb),porcupine, bear, duck, geese, moose, and other game.

Fruits, vegetables, grains: corn,oats, rye, wheat, numerous kinds of berries, cherries, plums, walnuts, squashand pumpkin, beans and peas, onion, carrots, turnips, potatoes, purslane, leafygreens (some of which you'd call weeds) and many others.

Beverages: everyone drank beer orale, even children, as they deemed it more healthful than water. They also hadwines, soft and hard cider, and after about 1660, tea. Drunkenness was a crimeand a sin, so they were moderate in their drinking.

Recipes are from a 1615 NewBook of Cookerie, a popular book in England,and almost certainly used in New England. Inaddition to these English favorites, they would have learned to prepare cornmeal mush patties, dry venison, and pemmican (meat and berries or grains processed togetherand dried).

Recipes are from a 1615 NewBook of Cookerie, a popular book in England,and almost certainly used in New England. Inaddition to these English favorites, they would have learned to prepare cornmeal mush patties, dry venison, and pemmican (meat and berries or grains processed togetherand dried).  A Cambridge Pudding

A Cambridge PuddingForce grated Bread through a Cullinder, mince it with Flower, minst Dates,Currins, Nutmeg, Sinamon, and Pepper, minst Suit [suet], new Milke warme, fineSugar, and Egges: take away some of their whites, worke all together. Takehalfe the Pudding on the one side, and the other on the other side, and make itround like a loafe. Then take Butter, and put it in the middest of the Pudding,and the other halfe aloft. Let your liquour boyle, and throw your Pudding in,being tyed in a faire cloth: when it is boyled enough cut it in the middest,and so serve it in.

To sowce [pickle,souse] a Pigge

Scald a large Pigge, cut off his head and slit him in the middest, and take outhis bones, and wash him in two or three warme waters. Then collar him up likeBrawne [boar], and sowe the collars in a fayre cloth. Then boyle them verytender in faire water, then take them up and throw them in fayre water and Saltuntill they be colde, for that will make the skinne white. Then take a pottleof the same water, that the Pigge was boyled in, and a pottle of white Wine, arace of Ginger sliced, a couple of Nutmegs quartered, a spoonefull of wholePepper, five or sixe Bay leaves: seeth all this together, when it is colde putyour Pigge into the sowce-drincke, so you may keepe it halfe a yeere, but spendthe head.

A made Dish ofSheepes tongues

Boyle them tender, and slice them in thinne slices: then season them withSinamon, Ginger, and a little Pepper, and put them into a Coffin of fine Paste,with sweet Butter, and a few sweet Hearbes, chopt fine. Bake them in anOven. Then take a little Nutmeg, Vinegar, Butter, Sugar, the yolke of a newlaid Egge, one spoonfull of Sacke, and the juyce of a Lemon: Boyle all thesetogether on a chafing-dish of Coales, and put it into your Pye: shog it welltogether, and serve it to the Table.

To bake a Turkey, or a Capon

To bake a Turkey, or a Capon Bone the Turkey,but not the Capon: parboyle them, & sticke cloves in their breasts: Lardthem and season them well with Pepper and Salt, and put them in a deepe Coffinwith the breast downeward, and store ofButter. When it is bakte poure inmore butter, and when it is colde stop the venthole with more Butter.

Published on November 08, 2011 23:01

October 30, 2011

Sir Henry Vane the Younger

© Christy K. Robinson

Massachusetts Bay Colony Governors JohnWinthrop and Thomas Dudley were not close friends (in fact, they were rather miffedat one another on several occasions), but they were fathers-in-law,co-investors in the MassBay Company, and brothers in the faith. Despite theirdifferences of opinion in government matters (Winthrop was lenient on his erring friendRoger Williams and Dudley wanted Williams exiled even in harsh midwinter), it was theirpractice to stay professional, work together, and present a unified front.

Henry Vane the Younger, 1637So imagine theirsurprise when cocky, 24-year-old Henry Vane called a meeting on January 18, 1636,about the "reconciliation" of Winthrop and Dudley. Among the citizens, factionswere forming for Winthrop and Dudley, said Vane. He was a new arrival to Boston in 1635, and camewith family wealth and royal court connections. He was popular with the peopleof Boston andthe magistrates hoped for Vane's brilliant career in colonial government.

Henry Vane the Younger, 1637So imagine theirsurprise when cocky, 24-year-old Henry Vane called a meeting on January 18, 1636,about the "reconciliation" of Winthrop and Dudley. Among the citizens, factionswere forming for Winthrop and Dudley, said Vane. He was a new arrival to Boston in 1635, and camewith family wealth and royal court connections. He was popular with the peopleof Boston andthe magistrates hoped for Vane's brilliant career in colonial government.

Those present at the meeting were Governor John Haynes,Reverends John Cotton, John Wilson, Thomas Hooker, and Hugh Peter, as well asWinthrop and Dudley, of course.

"Vane declared the occasion of this meeting," wrote Winthropin his Journal: "A more firm and friendly uniting of minds, etc.,especially of the said Mr. Dudley and Mr. Winthrop, as those upon whom theweight of the affairs did lie, and therefore desired all present to take up aresolution to deal freely and openly with the parties, and they each withother, that nothing might be left in their breasts, which might break out toany jar or difference hereafter."

After hearing Vane's concern about the lack of hugs,affectionate glances, Saturday barbecues, and warm fuzzies, Winthrop and Dudley protested (politelyand wordily) that they'd reconciled and healed their differences long ago, andthat they were "brothers," and if people complained, that was their problem. Surelythese fiftyish men with dignitas wereannoyed at being called out to a "come to Jesus meeting" by a meddlingtwenty-something newcomer. And seriously, wasn't there some real business to conduct?

Governor Haynes requested that the ministers confer andcreate a rule, and that they all should meet the next day. The conclusions of the ministers were that there should be "more strictness used in civil government and military discipline;" that the magistrates should confer privately, decide cases and deliver their verdicts with a face of unanimity; not to discuss cases out of court; speak not to the person but to the cause of a case; not to make faces or continue to argue against fellow magistrates when disagreeing; and that the magistrates should appear "more solemnly in public, with attendance, apparel [a dig at the dandily-dressed Henry Vane], and open notice of their entrance into the court." And further, that the magistrates should be more open and familiar with each other, visit more frequently, and honor the others.(As for the Massachusetts Baygovernors' council and their resolution for charity and professionalcomportment at the conclusion of Henry Vane's warm-fuzzy meeting, in the autumnof 1637, when these magistrates and ministers were trying Anne Hutchinson forheresy, they made personal attacks on her, and showed open contempt and disdain.Their emotions ran so high that they seemed to forget the rules of conduct laidout and agreed to in 1635. When Hutchinsondesired to know how she deserved the banishment sentence, John Winthropsnapped, "Say no more! The court knows whereof and is satisfied.")

It's quite possible that Henry Vane was already well-acquainted withWilliam Dyer and his former master,Walter Blackborne, both of whom had lived near the Thames in Westminster and were taxed in the sameparish (St. Martin-in-the-Fields) as Henry's father had been. Vane and Dyer, who were about four yearsapart in age, were admitted to freeman status (voters and members of the churchand community) at the same time.

When Henry Vane first arrived in Boston,he was admired for his Puritan fervor, his government connections in England,and his family's money (rich people were obviouslyblessed by God). His father, Henry Vane the Elder, who was an Anglican, hadgiven his eldest son and heir leave to spend three years in New England, and itseemed Henry was actually headed to Connecticut, but Boston caught him andthere he stayed. John Winthrop was peeved at Henry's flamboyance with hisapparel and his attendants (what you might call a posse).

Soon, Henry became a supporter of Anne Hutchinson and herteachings, along with the Dyers and many other men and women of Boston, and that really infuriated Winthrop. Henry, a single man, lived in the very nice home of Rev. John Cotton, one of the "stars" in the Boston firmament, and many of the Hutchinson teaching sessions revolved around the sermons of her mentor of 20 years, Rev. Cotton. Henry was in the very heart of the biggest thing to come down the turnpike—except that the Massachusetts Turnpike wouldn't be built for 320 years!